Submitted:

20 February 2025

Posted:

21 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

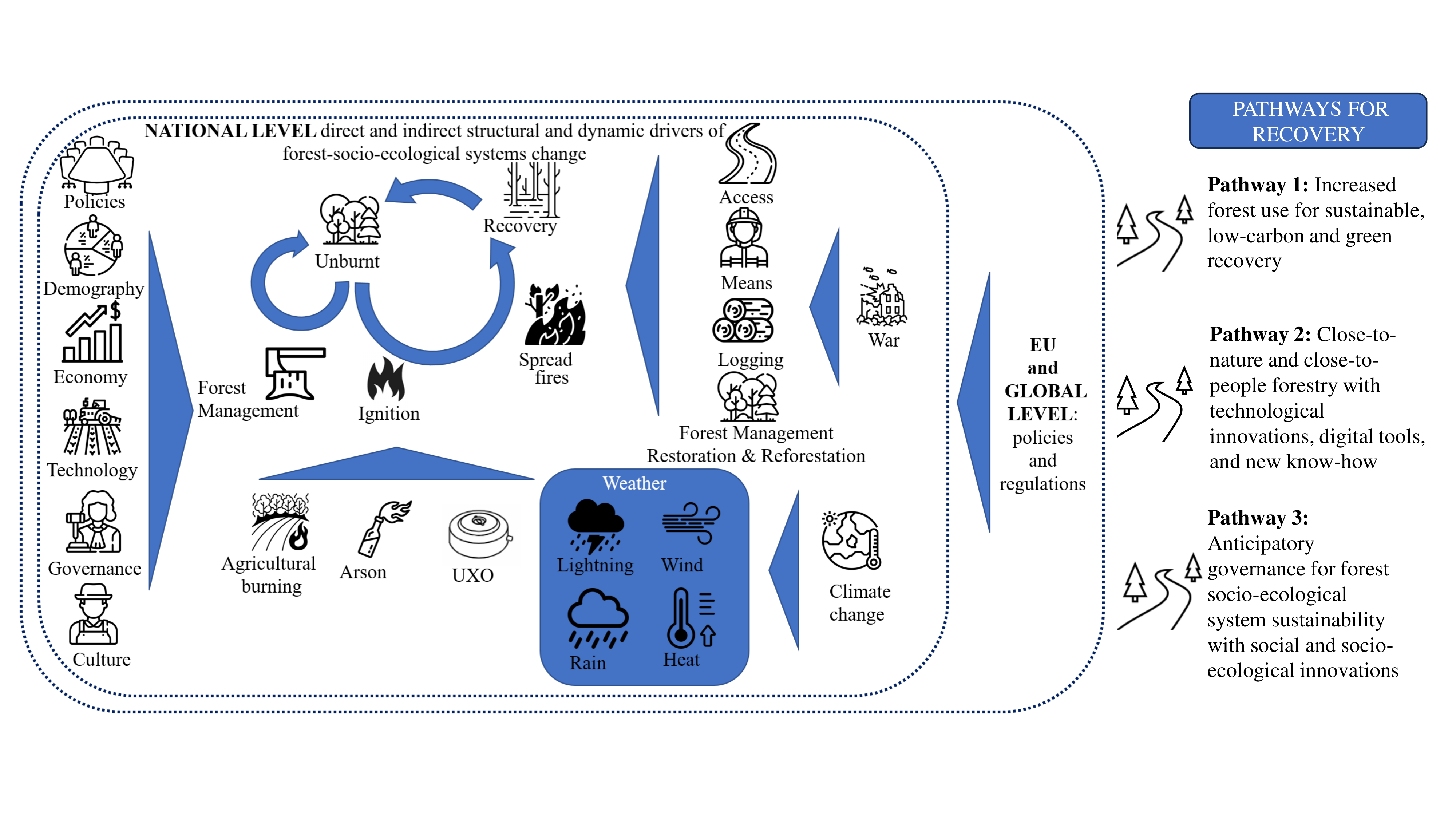

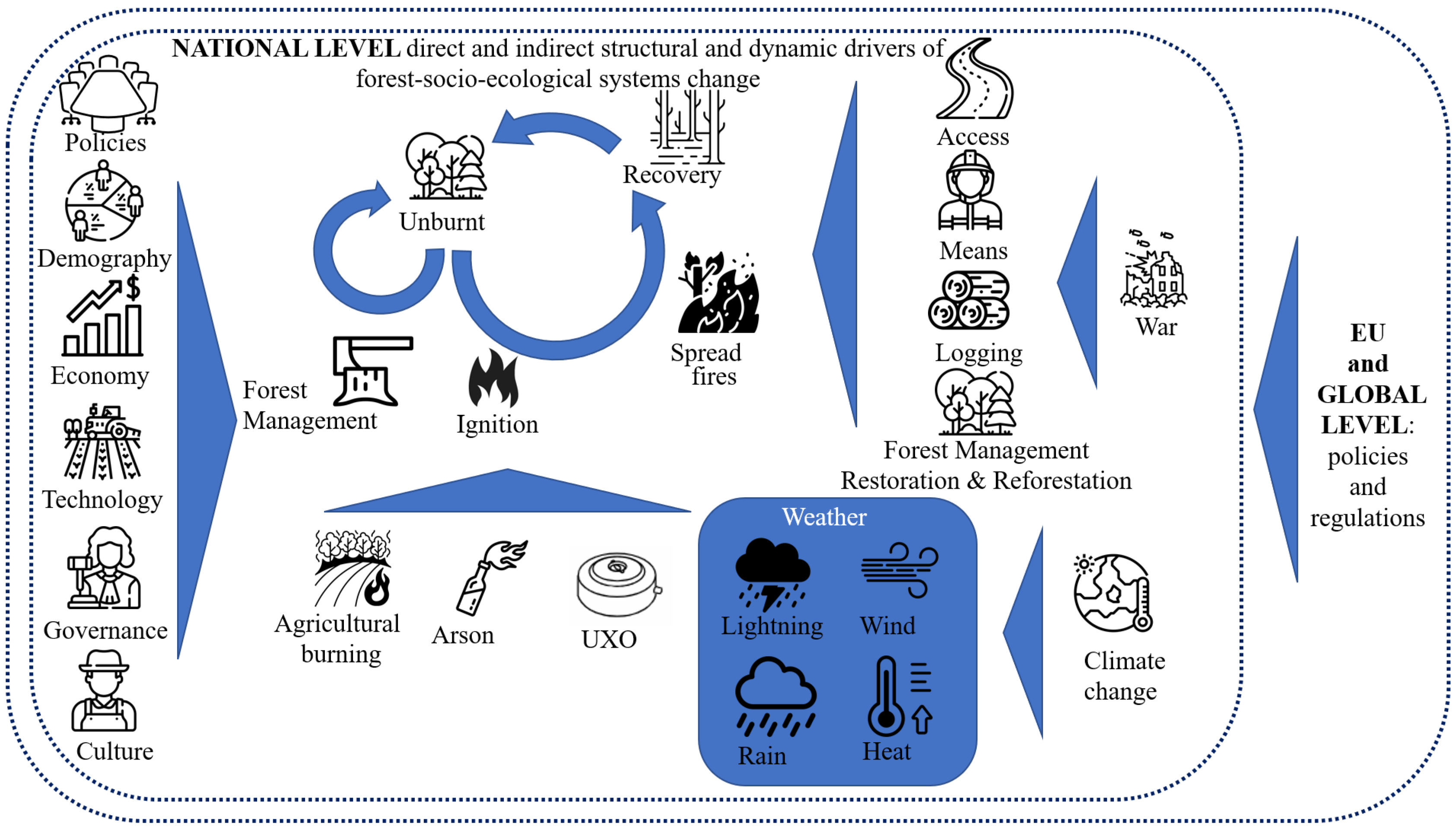

3.1. Baseline Assessment: Contextual Review of Ukraine’s Forest Socio-Ecological Systems

3.2. Nature of the Crisis

3.2.1. Pre-War challenges

3.2.2. War-Induced Crises

3.3. Scope of the Crisis

3.3.1. Root Causes

3.3.2. Impact

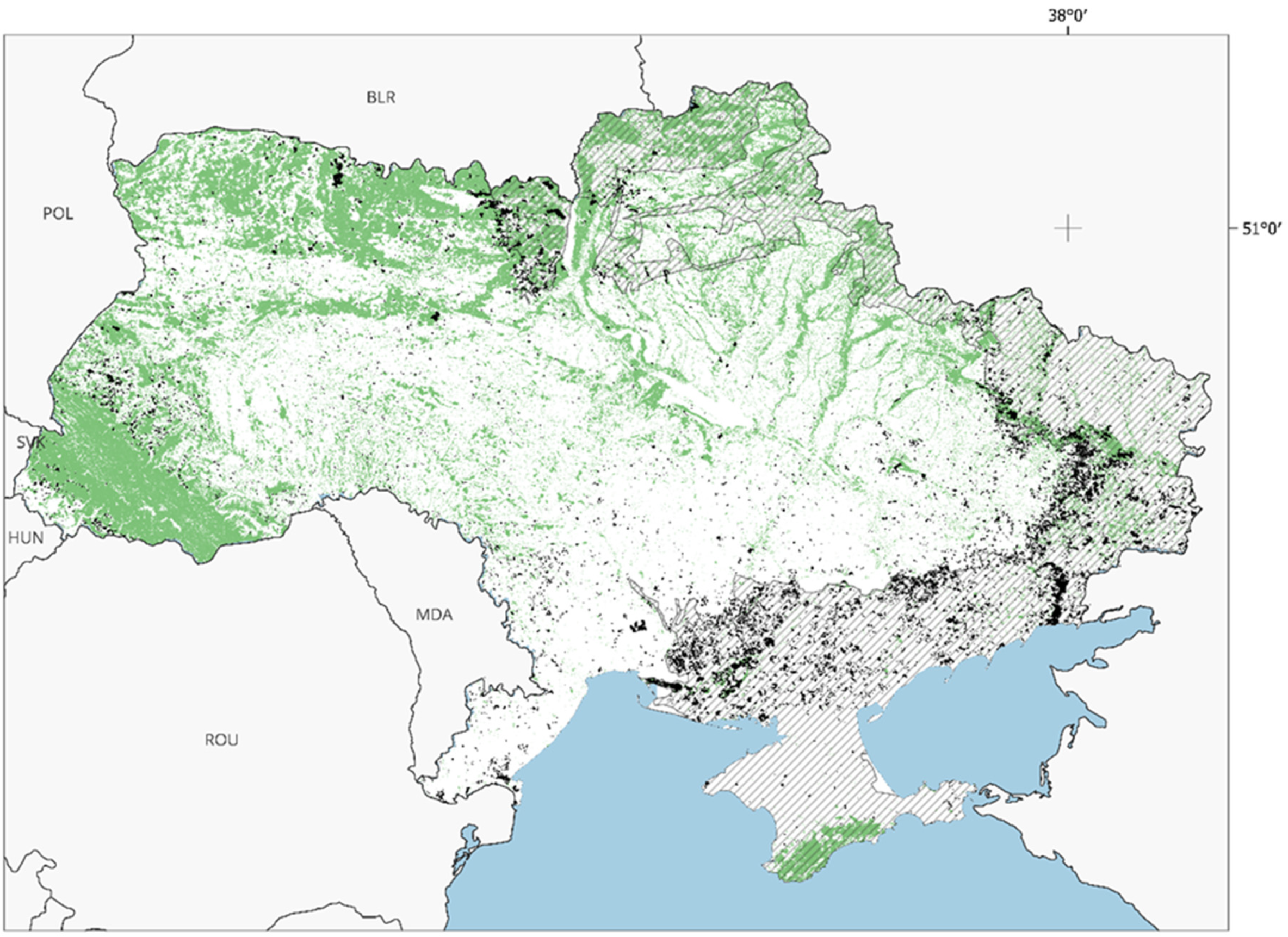

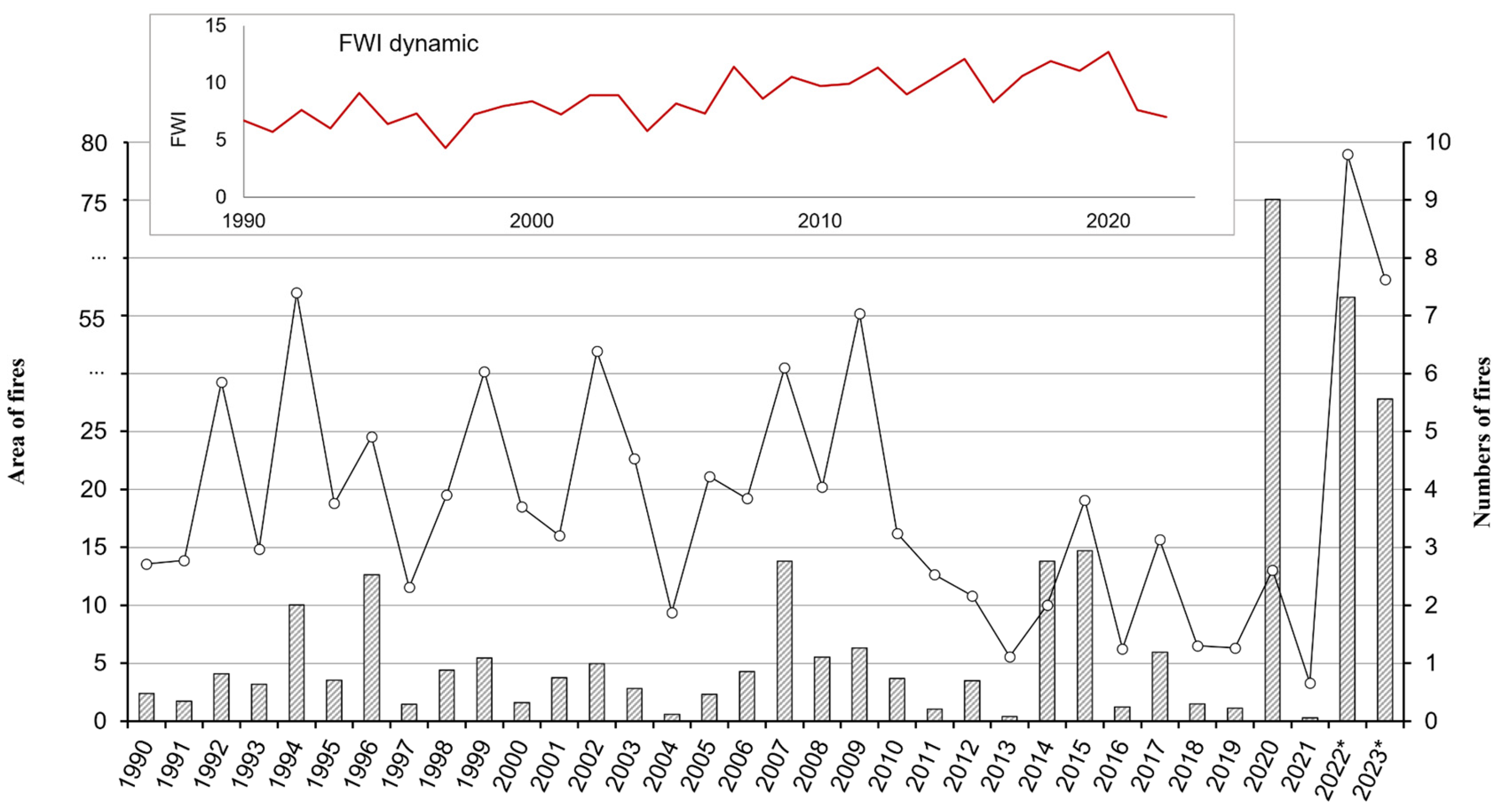

Forest Fires and Biodiversity Loss

Socio-Economic and Market Dynamics in Forestry

Forest Governance and Management

3.4. Resolution: Pathways for Recovery

Pathway 1: Increased Forest Use for Sustainable, Low-Carbon and Green Recovery

Pathway 2: Close-to-Nature and Close-to-People Forestry with Technological Innovations, Digital Tools, and New Know-How

Pathway 3: Anticipatory Governance for Forest Socio-Ecological System Sustainability with Social and Socio-Ecological Innovations

4. Discussions

Forests Are Cornerstones of Resilient Post-War Recovery

Forests Offer Diverse Values Beyond Timber Extraction

Relying on a Single Recovery Pathway Risks Long-Term Vulnerability

Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Questionnaire applied to interview forestry experts in Ukraine

References

- Folke, C., Hahn, T., Olsson, P., Norberg, J., 2005. Adaptive governance of social-ecological systems. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 30, 441–473. [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E., 2009. A general framework for analyzing sustainability of social-ecological systems. Science 325, 419–422. [CrossRef]

- Palomo, I., Montes, C., Martín-López, B., González, J.A., García-Llorente, M., Alcorlo, P., García Mora, M.R., 2014. Incorporating the social–ecological approach in protected areas in the Anthropocene. BioScience 64(3), 181–191. [CrossRef]

- Sarkki, S., Ficko, A., Wielgolaski, F.E., Abraham, E.M., Bratanova-Doncheva, S., Grunewald, K., Hofgaard, A., Holtmeier, F.-K., Kyriazopoulos, A.P., Broll, G., Nijnik, M., Sutinen, M.-L., 2017. Assessing the resilient provision of ecosystem services by social-ecological systems: Introduction and theory. Climate Research 73, 7–15. [CrossRef]

- Sarkki, S., Parpan, T., Melnykovych, M., et al., 2019a. Beyond participation! Social innovations facilitating movement from authoritative state to participatory forest governance in Ukraine. Landsc. Ecol. 34, 1601–1618. [CrossRef]

- Melnykovych, M., Nijnik, M., Soloviy, I., Nijnik, A., Sarkki, S., Bihun, Y., 2018. Social-ecological innovation in remote mountain areas: Adaptive responses of forest-dependent communities to the challenges of a changing world. Sci. Total Environ. 613–614, 894–906. [CrossRef]

- Walters, B.B., 2017. Explaining rural land use change and reforestation: A causal-historical approach. Land Use Policy 67, 608–624. [CrossRef]

- Grima, N., Singh, S.J., 2019. How the end of armed conflicts influence forest cover and subsequently ecosystem services provision? An analysis of four case studies in biodiversity hotspots. Land Use Policy 81, 267–275. [CrossRef]

- Rudel, T.K., Meyfroidt, P., Chazdon, R., et al., 2020. Whither the forest transition? Climate change, policy responses, and redistributed forests in the twenty-first century. Ambio 49, 74–84. [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W., Eustachio, J.H.P.P., Fedoruk, M., Lisovska, T., 2024a. War in Ukraine: An overview of environmental impacts and consequences for human health. Front. Sustain. Resour. Manag. 3, Article 1423444. [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W., Fedoruk, M., Eustachio, J.H.P.P., Splodytel, A., Smaliychuk, A., Szynkowska-Jóźwik, M.I., 2024b. The environment as the first victim: The impacts of the war on the preservation areas in Ukraine. J. Environ. Manag. 364, Article 121399. [CrossRef]

- Meaza, H., Ghebreyohannes, T., Nyssen, J., Tesfamariam, Z., Demissie, B., Poesen, J., Gebrehiwot, M., Weldemichel, T.G., Deckers, S., Gidey, D.G., Vanmaercke, M., 2024. Managing the environmental impacts of war: What can be learned from conflict-vulnerable communities? Sci. Total Environ. 171974. [CrossRef]

- Unruh, J., Williams, R.C., (Eds.), 2013. Lessons learned in land tenure and natural resource management in post-conflict societies. In: Land and Post-Conflict Peacebuilding. Routledge, London, UK, pp. 535–576.

- Vanegas-Cubillos, M., Sylvester, J., Villarino, E., Pérez-Marulanda, L., Ganzenmüller, R., Löhr, K., Bonatti, M., Castro-Nunez, A., 2022. Forest cover changes and public policy: A literature review for post-conflict Colombia. Land Use Policy 114, 105981. [CrossRef]

- Flower, B.C., Ganepola, P., Popuri, S., Turkstra, J., 2023. Securing tenure for conflict-affected populations: A case study of land titling and fit-for-purpose land administration in post-conflict Sri Lanka. Land Use Policy 125, 106438. [CrossRef]

- Gensiruk, S., 2002. Forests of Ukraine. Scientific Society named after Shevchenko, Lviv (in Ukrainian).

- Redo, D.J., Grau, H.R., Aide, T.M., Clark, M.L., 2012. Asymmetric forest transition driven by the interaction of socioeconomic development and environmental heterogeneity in Central America. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109(23), 8839–8844. [CrossRef]

- Forino, G., Ciccarelli, S., Bonamici, S., Perini, L., Salvati, L., 2015. Developmental policies, long-term land-use changes and the way towards soil degradation: Evidence from Southern Italy. Scott. Geogr. J. 131(2), 123–140. [CrossRef]

- Kuemmerle, T., Hostert, P., Radeloff, V.C., Perzanowski, K., Kruhlov, I., 2007. Post-socialist forest disturbance in the Carpathian border region of Poland, Slovakia, and Ukraine. Ecol. Appl. 17(5), 1279–1295. [CrossRef]

- Keeton, W.S., Angelstam, P., Baumflek, M., Bihun, Y., Chernyavskyy, M., Crow, S.M., Deyneka, A., Elbakidze, M., Farley, J., Kovalyshyn, V., Mahura, B., Myklush, S., Nunery, J.R., Solovity, I., Zahvoyska, L., 2013. Sustainable forest management alternatives for the Carpathian Mountain region, with a focus on Ukraine. In: Kozak, J., Ostapowicz, K., Bytnerowicz, A., Wyzga, B. (Eds.), The Carpathians: Integrating Nature and Society Towards Sustainability. Springer-Verlag, Berlin and Heidelberg, Germany, pp. 331–352.

- Kholiavchuk, D., Gurgiser, W., Mayr, S., 2023. Carpathian forests: Past and recent developments. Forests 15(1), 65. [CrossRef]

- Baumann, M., Kuemmerle, T., Elbakidze, M., Ozdogan, M., Radeloff, V.C., Keuler, N.S., Prishchepov, A.V., Kruhlov, I., Hostert, P., 2011. Patterns and drivers of post-socialist farmland abandonment in Western Ukraine. Land Use Policy 28(3), 552–562. [CrossRef]

- Smaliychuk, A., Müller, D., Prishchepov, A.V., Levers, C., Kruhlov, I., Kuemmerle, T., 2016. Recultivation of abandoned agricultural lands in Ukraine: Patterns and drivers. Glob. Environ. Change 38, 70–81. [CrossRef]

- Le Billon, P., 2000. The political ecology of transition in Cambodia 1989–1999: war, peace and forest exploitation. Dev. Change 31, 785–805. [CrossRef]

- Musa, S., Šiljković, Ž. and Šakić, D., 2017. Geographical reflections of mine pollution in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia. Journal for Geography/Revija za Geografijo, 12(2), 53–70.

- Knorn, J., Kuemmerle, T., Radeloff, V.C., Keeton, W.S., Gancz, V., Biriș, I.-A., Svoboda, M., Griffiths, P., Hagatis, A., Hostert, P., 2013. Continued loss of temperate old-growth forests in the Romanian Carpathians despite an increasing protected area network. Environ. Conserv. 40(2), 182–193. [CrossRef]

- Cronkleton, P., Bray, D.B., Medina, G., 2011. Community forest management and the emergence of multi-scale governance institutions: Lessons for REDD+ development from Mexico, Brazil and Bolivia. Forests 2, 451–473. [CrossRef]

- Jenke, M., 2024. Community-based forest management moderates the impact of deforestation pressure in Thailand. Land Use Policy 147, 107351. [CrossRef]

- OECD, 2022. Environmental impacts of the war in Ukraine and prospects for a green reconstruction. OECD Policy Responses on the Impacts of the War in Ukraine. OECD Publishing, Paris. [CrossRef]

- Henig, D., 2012. Iron in the soil: Living with military waste in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Anthropology Today 28, 21–23. [CrossRef]

- Baselt, I., Skejic, A., Zindovic, B., Bender, J., 2023. Geologically-driven migration of landmines and explosive remnants of war—A feature focusing on the Western Balkans. Geosciences 13, 178. [CrossRef]

- WWF, 2023. The role of nature-based solutions in Ukraine’s forest recovery: Building resilience for biodiversity and climate adaptation. World Wide Fund for Nature Report.

- Nehrey, M., Finger, R., 2024. Assessing the initial impact of the Russian invasion on Ukrainian agriculture: Challenges, policy responses, and future prospects. Heliyon. [CrossRef]

- Prins, K., 2022. War in Ukraine, and extensive forest damage in central Europe: Supplementary challenges for forests and timber or the beginning of a new era? For. Policy Econ. 140, 102736. [CrossRef]

- Zibtsev, S., Myroniuk, V., Soshenskyi, O., Sydorenko, S., Bogomolov, V., Kalchuk, Ye., Zibtseva, I., 2023a. Ukraine Fire Perimeters 2022 (Ver. 1) [Data set]. Zenodo. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, P., Bašić, F., Bogunovic, I., Barcelo, D., 2022. Russian-Ukrainian war impacts the total environment. Sci. Total Environ. 837, 155865. [CrossRef]

- Irland, L.C., Iavorivska, L., Zibtsev, S., Myroniuk, V., Roth, B., Bilous, A., 2023. Russian invasion: rapid assessment of impact on Ukraine’s forests. Proc. For. Acad. Sci. Ukr. 25, 146–155. [CrossRef]

- Shumilo, L., Skakun, S., Gore, M.L., Shelestov, A., Kussul, N., Hurtt, G., Karabchuk, D., Yarotskiy, V., 2023. Conservation policies and management in the Ukrainian Emerald Network have maintained reforestation rate despite the war. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 443. [CrossRef]

- Matsala, M., Odruzhenko, A., Hinchuk, T., Myroniuk, V., Drobyshev, I., Sydorenko, S., Zibtsev, S., Milakovsky, B., Schepaschenko, D., Kraxner, F., Bilous, A., 2024. War drives forest fire risks and highlights the need for more ecologically-sound forest management in post-war Ukraine. Sci. Rep. 14, 4131. [CrossRef]

- Myroniuk, V., Weinreich, A., von Dosky, V., Melnychenko, V., Shamrai, A., Matsala, M., Gregory, M.J., Bell, D.M., Davis, R., 2024. Nationwide remote sensing framework for forest resource assessment in war-affected Ukraine. For. Ecol. Manag. 569, 122156. [CrossRef]

- Hryhorczuk, D., Levy, B.S., Prodanchuk, M., et al., 2024. The environmental health impacts of Russia’s war on Ukraine. J. Occup. Med. Toxicol. 19, 1. [CrossRef]

- Flamm, P., Kroll, S., 2024. Environmental (in)security, peacebuilding, and green economic recovery in the context of Russia’s war against Ukraine. Environ. Secur. 2(1), 21–46. [CrossRef]

- CEO & Zoï [Conflict and Environment Observatory and Zoï Environment Network], 2024. The Environmental Consequences of the War against Ukraine. Preliminary twelve-month assessment (February 2022–February 2023). https://zoinet.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/OSCE-Ukraine-env-cons_EN.pdf.

- UNEP, 2022. United Nations Environment Programme. The Environmental Impact of the Conflict in Ukraine: A Preliminary Review. UNEP, Nairobi, Kenya. URL: https://wedocs.unep.org/20.500.11822/40746.

- UNEP, 2019. Rooting for the environment in times of conflict and war. URL: https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/rooting-environment-times-conflict-and-war?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Jacobsson and Lehto, 2020.

- Bergström, J., Uhr, C., Frykmer, T., 2016. A complexity framework for studying disaster response management. J. Contingencies Crisis Manag. 24(3), 124–135. [CrossRef]

- IUFRO report from Forum on Ukraine Forest Science and Education: Needs and Priorities for Collaboration (2024).

- Forest Europe, 2023. Ukraine Forestry Strategy 2030: Sustainable Management and Biodiversity Conservation for Post-War Recovery. Ministerial Conference on the Protection of Forests in Europe. Bonn, Germany.

- World Bank, 2020. Ukraine Country Forest Note: Growing Green and Sustainable Opportunities. URL: https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/938941593413817490/ukraine-country-forest-note-growing-green-and-sustainable-opportunities.

- World Bank, GoU, EC, United Nations (UN), 2024. Ukraine Rapid Damage and Needs Assessment: February 2022–December 2023. Available at: https://euneighbourseast.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/p1801741bea12c012189ca16d95d8c2556a-compressed-1.pdf.

- SSSU, 2024. State Statistics Service of Ukraine. Economic statistics, economic activity, agriculture, forestry, and fisheries. (in Ukrainian) URL: https://www.ukrstat.gov.ua/.

- FAO, 2023. FAO Forestry Support Strategy for Ukraine 2023–2027. FAO, Kyiv.

- Zibtsev, S., Burns, J., Buck, A., Kraxner, F., (Eds.), 2024a. Forest science and education in Ukraine: Priorities for action. Findings from the Forum on Ukraine Forest Science and Education: Needs and Priorities for Collaboration. 21–22 November 2023, International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA), Laxenburg, Austria. [CrossRef]

- Adu, P., 2019. A Step-by-Step Guide to Qualitative Data Coding. Routledge, London.

- Beland Lindahl, K., Baker, S., Rist, L., Zachrisson, A., 2015. Theorising pathways to sustainability. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 23, 399–411. [CrossRef]

- Beland Lindahl, K., Sandström, C., Sténs, A., 2017. Alternative pathways to sustainability? Comparing forest governance models. For. Policy Econ. 77, 69–78. [CrossRef]

- SFRA, 2024a. State Forest Resources Agency of Ukraine. List of State Forest Agency enterprises temporarily suspended. Retrieved November 11, 2024.

- Soloviy, I., Melnykovych, M., 2019. Illegal logging in Ukraine: The role of corruption and the need for governance reforms. J. Sustain. For. 38(7), 592–609.

- Nijnik, M., Kluvánková, T., Nijnik, A., Kopiy, S., Melnykovych, M., Sarkki, S., Barlagne, C., Brnkaláková, S., Kopiy, L., Fizyk, I., et al., 2020. Is there a scope for social innovation in Ukrainian forestry? Sustainability 12, 9674. [CrossRef]

- Nijnik, M., Kluvánková, T., Melnykovych, M., Nijnik, A., Kopiy, S., Brnkaláková, S., Sarkki, S., Kopiy, L., Fizyk, I., Barlagne, C., et al., 2021. An institutional analysis and reconfiguration framework for sustainability research on post-transition forestry—A focus on Ukraine. Sustainability 13, 4360. [CrossRef]

- Yukhnovskyi, V., Polishchuk, O., Lobchenko, G., et al., 2021. Aerodynamic properties of windbreaks of various designs formed by thinning in central Ukraine. Agrofor. Syst. 95, 855–865. [CrossRef]

- Yaroshchuk, S., Yaroshchuk, R., Grenz, J., Melnykovych, M., 2023. Das Leid der Bauern = La souffrance des paysan-ne-s. InfoHAFL: Das fundierte Magazin zur Land-, Wald- und Lebensmittelwirtschaft = Le magazine d’actualités agricoles, forestières et al.imentaires (1), 8–11. Berner Fachhochschule, Hochschule für Agrar-, Forst- und Lebensmittelwissenschaften HAFL.

- SFRA 2024c. State Forest Resources Agency of Ukraine. State Forest Cadastre Records as of January 1, 2011 [Dataset, updated May 13, 2024]. Ukrainian Open Data Portal. URL: https://data.gov.ua/dataset/341e5bd6-3855-4507-9a53-f95a9a1e3035.

- FSC, 2024. FSC Forest Stewardship Standard for Ukraine (FSC-STD-UKR-01.1-2024, Version 1-1). Forest Stewardship Council. https://connect.fsc.org/document-centre/documents/resource/428.

- Melnykovych, M., Nijnik, M., Soloviy, I., 2016. Non-wood forest products and the well-being of rural communities: Bringing cultural or provisioning ecosystem services to the surface? In: Proceedings of the COST Action FP1203 European Non-Wood Forest Products. URL: https://nwfps.eu/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/Mariana-Melnykovych-call3.pdf.

- Vacik, H., Wiersum, F., Mutke, S., Kurttila, M., Sheppard, J., Wong, J., de Miguel, S., Nijnik, M., Spiecker, H., Miina, J., Huber, P., Melnykovych, M., Tsioras, P., Abraham, E., Enescu, M., Kyriazopoulos, A., 2020. Considering NWFP in multipurpose forest management. In: Vacik, H., et al. (Eds.), Non-Wood Forest Products in Europe: Ecology and Management of Mushrooms, Tree Products, Understory Plants, and Animal Products. Outcomes of the COST Action FP1203 on European NWFPs. BoD, Norderstedt, pp. 79–123.

- Melnykovych, M., Soloviy, I., Nijnik, M., Nijnik, A., 2017. Ecosystem services, well-being, and social innovations: What the concepts mean for forest-dependent communities. Proceedings of the 12th Conference of the European Society for Ecological Economics, Budapest, Hungary, 20–23 June 2017, pp. 337–339.

- Sarkki, S., Ficko, A., Miller, D.R., Barlagne, C., Melnykovych, M., Jokinen, M., Soloviy, I., Nijnik, M., 2019b. Human values as catalysts and consequences of social innovations. For. Policy Econ. 104, 33–44. [CrossRef]

- Soloviy, I.P., Nijnik, M., Deyneka, A.M., Melnykovych, M.P., 2017. Reimagining forest policy, institutions, and instruments through concepts of ecosystem services and social innovations: Ukraine in the focus. Sci. Bull. UNFU 27(8), 82–87. [CrossRef]

- Poliakova, L., Abruscato, S., 2023. Supporting the recovery and sustainable management of Ukrainian forests and Ukraine’s forest sector. FOREST EUROPE. URL: https://foresteurope.org/rapid-response-mechanism/#ukraine_forests.

- FLEG, 2010. Forest law enforcement and governance (FLEG). World Bank Group, Washington, D.C. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/819561468339554023/Forest-law-enforcement-and-governance-FLEG-3.

- Lesiuk, H., Soloviy, I., 2024. The role of Ukraine’s forest sector in the national post-war recovery plan and the European Green Deal: A preliminary analysis. Econ. Ukr. 67(8), 88–104. [CrossRef]

- Dykan, V. V., Khoroshko, O. V., 2022. The modern investment management model of the forestry complex of Ukraine. Econ. Bull. Natl. Tech. Univ. Ukraine Kyiv Polytech. Inst. 24. [CrossRef]

- Dubovich, I., Lesiuk, H., Soloviy, I., Soloviy, V., 2019. Long way from government to governance: Meta-analysis of Ukrainian forestry reformation. In: Proceedings of the Biennial International Symposium “Forest and Sustainable Development,” 8th Edition, 25–27 October 2018, Brașov, Romania, pp. 117–118.

- State Forest Strategy 2023. The State Strategy of Forest Management in Ukraine up to 2035. Adopted by Governmental Decree 1777-p on 29.12.2021, pp. 74. Available at Прo схвалення Державнoї страт... | від 29.12.2021 № 1777-р.

- Khvesyk, M., Bystriakov, I., Stepanets, M., 2019. Conceptual basis of transformation of ecological and economic relations in the forest sector of Ukraine in the context of European integration. Folia For. Pol., Ser. A For. 61(2), 97–111. [CrossRef]

- Denisova-Schmidt, E., Huber, M., Prytula, Y., 2019. The effects of anti-corruption videos on attitudes toward corruption in a Ukrainian online survey. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 60(3), 304–332. [CrossRef]

- Gisladottir, J., Sigurgeirsdottir, S., Ragnarsdóttir, K.V., Stjernquist, I., 2021. Economies of scale and perceived corruption in natural resource management: A comparative study between Ukraine, Romania, and Iceland. Sustainability 13(13), 7363. [CrossRef]

- Zibtsev, S., Soshenskyi, O., Melnykovych, M., Blaser, J., Waeber, P.O., Garcia, C., 2023b. Ukrainische Wälder im Fokus von Klimakrise, Krieg und Brandkatastrophen. Schweiz. Z. Forstwes. 174(2), 115–117. [CrossRef]

- Zibtsev, S., Myroniuk, V., Soshenskyi, O., Kalchuk, Ye., Zibtseva, I., 2024b. Ukraine Fire Perimeters 2023 [Data set]. Zenodo. [CrossRef]

- Soshenskyi, O., Zibtsev, S., Kalchuk, Ye., 2023. Risks reduction of forest fires for settlements in Ukraine. In: Food and Environmental Protection in the Context of War and Post-War Reconstruction: Challenges for Ukraine and the World. International Scientific and Practical Conference, May 25, 2023, Kyiv, Ukraine. Section 2: Post-war Restoration of Plant Resources and Environmental Protection of the Country, pp. 480–481. URL: https://nubip.edu.ua/sites/default/files/u381/sekciya_2.pdf.

- Nijnik, M., Oskam, A., 2004. Governance in Ukrainian forestry: trends, impacts and remedies. International Journal of Agricultural Resources, Governance and Ecology, 3(1–2), 116–133. [CrossRef]

- Hrynyk, Y., Biletskyi, A., Cabrejo le Roux, A., 2023. How corruption threatens the forests of Ukraine: Typology and case studies on corruption and illegal logging. Working Paper 43, Environmental Corruption Deep Dive Series, Basel Institute on Governance. URL: https://baselgovernance.org/publications/deepdive1-ukraine.

- CMU, 2021. Cabinet Ministry of Ukraine: The order CMU of Ukraine N 1777-р 29.12.2021 “About approval of State Forest Governance Strategy of Ukraine until 2035.” Available in Ukrainian. URL: https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/1777-2021-%D1%80.

- Ministry of Environmental Protection, 2024. Ministry of Environmental Protection and Natural Resources of Ukraine. 71 billion dollars in losses and 180 million tons of emissions: At COP29, Ukraine announced the scale of environmental damage in 1,000 days of war. Gov. Portal Ukr. Published November 19, 2024. Available from: https://www.kmu.gov.ua/news/71-mlrd-dolariv-zbytkiv-ta-180-mln-tonn-vykydiv-na-sor29-ukraina-nazvala-masshtab-shkody-pryrodi-za-1000-dniv-viiny.

- Green Country Project (2021–2031). Available at https://zelenakraina.gov.ua/.

- Elbakidze, M., Angelstam, P., Sandström, C., 2024. Seven reasons to invest in agroforestry for post-war reconstruction and reform efforts in Ukraine. Agrofor. Netw. Available at: https://agroforestrynetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/AgroforestryUkraina_2024-120324-final.pdf.

- Melnykovych, M., Nijnik, M., Zibtsev, S., Soshenskyi, O., Loyko, L., Jaroschuk, R., Ustych, R., Lavnyy, V., Živojinović, I., Garcia, C., Waeber, P.O., 2024a. Seeing the forest for the trees: A multi-actor approach to trigger sustainable forest governance in post-war Ukraine. In: IUFRO World Congresses 2024. T4.20 Managing Safety and Resilience of Forests and Forestry Affected by Armed Conflicts and the Climate Crisis: Past and Future Contribution of Forest Science, 23–29 June 2024, Stockholm, Sweden, p. 3021. URL: https://www.iufro.org/fileadmin/material/events/iwc24/iwc24-abstracts.pdf.

- Mitrofanenko, T., Melnykovych, M., Kubal-Czerwińska, M., Kuraś, K., Vetier, M., Halada, L., Zawiejska, J., Nijnik, M., 2024. Bridging science, policy and practice for collaborations towards sustainable development in the Carpathian region. In: Safeguarding Mountain Social-Ecological Systems, Vol. 2: Building Transformative Resilience in Mountain Regions Worldwide. Elsevier, pp. 207–217. [CrossRef]

- Wypych, A., Bautista, C., Cooley, T., Fischer, E., Halada, L., Kaim, D., Keeton, W., Kholiavchuk, D., Melnykovych, M., Mikolajczyk, P., Mitrofanenko, T., Mráz, P., Zawiejska, J., 2024. Recommendations from Forum Carpaticum 2023 relevant for the CBF based on the CFB strategic objectives. 15th Meeting of the Carpathian Convention Working Group on Biodiversity, 17–18 June 2024, Vienna, Austria. Science4Carpathians.

- SFRA, 2024b. State Forest Resources Agency of Ukraine: Public report of the head of the State Forest Resources Agency of Ukraine for 2023. URL: https://forest.gov.ua/agentstvo/komunikaciyi-z-gromadskistyu/publichni-zviti-derzhlisagentstva.

- Plan for the Recovery of Ukraine, 2024. URL: https://recovery.gov.ua/en.

- Lugano Declaration, 2022. Final document of the International Conference on the Recovery of Ukraine: URC 2022. July 4–5, 2022. URL: https://www.eda.admin.ch/eda/en/fdfa/fdfa/aktuell/dossiers/urc2022-lugano.html.

- Soshenskyi, O., Zibtsev, S., Gumeniuk, V., Goldammer, J.G., Vasylyshyn, R., Blyshchyk, V., 2021a. The current landscape fire management in Ukraine and strategy for its improvement. Environ. Socio-econ. Stud. 9(2), 39–51. [CrossRef]

- Solokha, M., Pereira, P., Symochko, L., Vynokurova, N., Demyanyuk, O., Sementsova, K., Inacio, M., Barcelo, D., 2023. Russian-Ukrainian war impacts on the environment. Evidence from the field on soil properties and remote sensing. Sci. Total Environ. 902, 166122. [CrossRef]

- REEFMC, 2024. Regional Eastern Europe Fire Monitoring Center. National University of Life and Environmental Sciences of Ukraine. Monitoring of landscape fires in Ukraine. URL: https://nubip.edu.ua/node/9083/3 (in Ukrainian).

- De Klerk, L., Shlapak, M., Gassan-zade, O., Korthuis, A., Zibtsev, S., Myroniuk, V., Soshenskyi, O., Vasylyshyn, R., Krakovska, S., Kryshtop, L., 2024. Climate damage caused by Russia’s war in Ukraine. Initiative on GHG Accounting of War. 120 p. URL: https://en.ecoaction.org.ua/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Climate-Damage-Caused-by-War-24-months-EN.pdf.

- Bun, R., Marland, G., Oda, T., See, L., Puliafito, E., Nahorski, Z., Jonas, M., Kovalyshyn, V., Ialongo, I., Yashchun, O., Romanchuk, Z., 2024. Tracking unaccounted greenhouse gas emissions due to the war in Ukraine since 2022. Sci. Total Environ. 914, 169879. [CrossRef]

- Rawtani, D., Gupta, G., Khatri, N., Rao, P.K., Hussain, C.M., 2022. Environmental damages due to war in Ukraine: A perspective. Sci. Total Environ. 850, 157932. [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Environmental Protection, 2023. Over 20% of Ukraine’s protected areas affected by war. Government Portal. URL: https://www.kmu.gov.ua/news/mindovkillia-viinoiu-urazheno-ponad-20-pryrodookhoronnykh-terytorii-ukrainy.

- SFRA, 2023. State Forest Resources Agency of Ukraine: Public report of the head of the State Forest Resources Agency of Ukraine for 2022. State Forest Agency of Ukraine, Kyiv.

- ForestCom (2022).

- Mika, A., Keeton, W.S., 2015. Net carbon fluxes at stand and landscape scales from wood bioenergy harvests in the U.S. Northeast. Glob. Change Biol. Bioenergy 7(3), 438–454. [CrossRef]

- Soloviy, I., Melnykovych, M., Björnsen Gurung, A., Hewitt, R. J., Ustych, R., Maksymiv, L., Brang, P., Meessen, H., & Kaflyk, M., 2019. Innovation in the use of wood energy in the Ukrainian Carpathians: Opportunities and threats for rural communities. Forest Policy and Economics, 104, 160–169. [CrossRef]

- The European Green Deal 2024. The European Green Deal: Impact on Ukraine’s Energy, Climate and Environment Policies and Legislation. Policy Brief. Resource and Analysis Center “Society and Environment,” DiXi Group, 2024. Available at: https://rac.org.ua/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/racse-policy-brief-european-green-deal-september-2024-eng.pdf.

- Rosset, C., 2021. The added value of digitalisation: More information, connection, and agility. Schweiz. Z. Forstwes. 172(4), 198–204. [CrossRef]

- Aszalós, R., Thom, D., Aakala, T., Angelstam, P., Brūmelis, G., Gálhidy, L., Gratzer, G., Hlásny, T., Katzensteiner, K., Kovács, B., Knoke, T., Larrieu, L., Motta, R., Müller, J., Ódor, P., Roženbergar, D., Paillet, Y., Pitar, D., Standovár, T., Svoboda, M., Szwagrzyk, J., Toscani, P., Keeton, W.S., 2022. Natural disturbance regimes as a guide for sustainable forest management in Europe. Ecol. Appl. 32, e2596. [CrossRef]

- Garcia, C.A., Savilaakso, S., Verburg, R.W., Stoudmann, N., Fernbach, P., Sloman, S.A., Peterson, G.D., Araújo, M.B., Bastin, J.-F., Blaser, J., Boutinot, L., Crowther, T.W., Dessard, H., Dray, A., Francisco, S., Ghazoul, J., Feintrenie, L., Hainzelin, E., Kleinschroth, F., Naimi, B., Novotny, I.P., Oszwald, J., Pietsch, S.A., Quétier, F., Waeber, P.O., 2022. Strategy games to improve environmental policymaking. Nat. Sustain. 5, 464–471. [CrossRef]

- Verkerk, P.J., Costanza, R., Hetemäki, L., Kubiszewski, I., Leskinen, P., Nabuurs, G.J., Potočnik, J., Palahí, M., 2020. Climate-smart forestry: The missing link. For. Policy Econ. 115, 102164. [CrossRef]

- Mathys, A.S., Bottero, A., Stadelmann, G., Thürig, E., Ferretti, M., Temperli, C., 2021. Presenting a climate-smart forestry evaluation framework based on national forest inventories. Ecol. Indic. 133, 108459. [CrossRef]

- Seddon, N., Smith, A., Smith, P., Key, I., Chausson, A., Girardin, C., House, J., Srivastava, S., Turner, B., 2021. Getting the message right on nature-based solutions to climate change. Glob. Change Biol. 27(2), 239–251. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, L., MacFarlane, D., 2023. Climate-smart forestry: Promise and risks for forests, society, and climate. PLOS Clim. 2(6), e0000212. [CrossRef]

- Wellmann, T., Andersson, E., Knapp, S., Lausch, A., Palliwoda, J., Priess, J., Scheuer, S., Haase, D., 2023. Reinforcing nature-based solutions through tools providing social-ecological-technological integration. Ambio 52(3), 489–507. [CrossRef]

- Waeber, P.O., Carmenta, R., Carmona, N.E., Garcia, C.A., Falk, T., Fellay, A., Ghazoul, J., Reed, J., Willemen, L., Zhang, W., Kleinschroth, F., 2023. Structuring the complexity of integrated landscape approaches into selectable, scalable, and measurable attributes. Environ. Sci. Policy 147, 67–77. [CrossRef]

- Krynytskyi, H.T., Chernyavskyi, M.V., Krynytska, O., Dejneka, A.M., Kolisnyk, B., Tselen, Ya.P., 2017. Close-to-nature forestry as the basis for sustainable forest management in Ukraine. Sci. Bull. UNFU 27, 26–31.

- Spathelf et al. 2024.

- Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine. (2021). National Forest Inventory Program: On approval of the procedure for conducting the national forest inventory and amendments to the annex to the Regulation on the datasets subject to disclosure as open data. Resolution No. 392, April 21, 2021, Kyiv. Updated April 28, 2023. Retrieved from https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/392-2021-%D0%BF#Text.

- Muiderman, K., Gupta, A., Vervoort, J., Biermann, F., 2020. Four approaches to anticipatory climate governance: Different conceptions of the future and implications for the present. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Clim. Change 11(6), e673. [CrossRef]

- Program on Anti-Corruption Measures in Forestry, 2023. Anti-corruption programme of the State Enterprise ‘Forests of Ukraine’ for 2023–2025. Available at: https://e-forest.gov.ua/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Antykoruptsijna-prohrama.pdf.

- Villanueva, F.D.P., Tegegne, Y.T., Winkel, G., Cerutti, P.O., Ramcilovic-Suominen, S., McDermott, C.L., Zeitlin, J., Sotirov, M., Cashore, B., Wardell, D.A., Haywood, A., 2023. Effects of EU illegal logging policy on timber-supplying countries: A systematic review. J. Environ. Manag. 327, 116874. [CrossRef]

- CAS Rebuild Ukraine, 2024. [Certificate of Advanced Studies Rebuild Ukraine]. Bern University of Applied Sciences. https://www.bfh.ch/de/weiterbildung/cas/wiederaufbau-ukraine/.

- Sarkki, S., Ludvig, A., Fransala, J., Melnykovych, M., Živojinović, I., Ravazzoli, E., Bengoumi, M., Nijnik, M., Dalla Torre, C., Górriz-Mifsud, E., Labidi, A., Sfeir, P., López Marco, L., Valero López, D.E., Joyce, K., Chorti, H., 2024. Women-led social innovation initiatives contribute to gender equality in rural areas: Grounded theory on five initiatives from three continents. Eur. Countrys. 16(4). [CrossRef]

- SCU, 2014. Science Communication Unit. Science for Environment Policy In-depth Report: Social Innovation and the Environment. University of the West of England, Bristol. Report produced for the European Commission DG Environment, February 2014. Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/science-environment-policy.

- SIMRA, 2020. Social innovation in marginalised rural areas. Innovative, sustainable, and inclusive bioeconomy, Topic ISIB-03-2015. Unlocking the growth potential of rural areas through enhanced governance and social innovation. European Union Framework Programme Horizon 2020, Final report, Brussels.

- Nijnik, M., Kluvánková, T., Melnykovych, M., 2022. The power of social innovation to steer sustainable governance of nature. Environ. Policy Gov. 32, 453–458. [CrossRef]

- Lukesch, R., Ludvig, A., Slee, B., Weiss, G., Živojinović, I., 2020. Social innovation, societal change, and the role of policies. Sustainability 12, 7407. [CrossRef]

- Weiss, T., Fischer, M., Fischer, C., Drescher, M., 2021. Forest innovation governance: A systematic literature review. For. Policy Econ. 126, 102506. [CrossRef]

- Kluvankova, T., Nijnik, M., Spacek, M., Sarkki, S., Perlik, M., Lukesch, R., Melnykovych, M., Valero, D., Brnkalakova, S., 2021. Social innovation for sustainability transformation and its diverging development paths in marginalised rural areas. Sociol. Ruralis 61(1), 122–147. [CrossRef]

- Górriz-Mifsud, E., Melnykovych, M., Marini Govigli, V., Alkhaled, S., Arnesen, T., Barlagne, C., Bjerk, M., Burlando, C., Jack, S., Rodríguez Fernández-Blanco, C., Prokofieva, I., Sfeir, P., Slee, B., Miller, D., 2019. Report on lessons learned from social innovation actions in marginalised rural areas (Deliverable 7.3). In: Soc. Innov. Marginalised Rural Areas. Horizon 2020: Innovative, Sustainable and Inclusive Bioeconomy, 54 pp. Available at : https://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/documents/downloadPublic?documentIds=080166e5ca57ae27&appId=PPGMS.

- Barlagne, C., Melnykovych, M., Miller, D., Hewitt, R.J., Secco, L., Pisani, E., Nijnik, M., 2021. What are the impacts of social innovation? A synthetic review and case study of community forestry in the Scottish Highlands. Sustainability 13(8), 4359. [CrossRef]

- Brnkalakova, S., Melnykovych, M., Nijnik, M., Barlagne, C., Pavelka, M., Udovc, A., Marek, M., Kovac, U., Kluvánková, T., 2022. Collective forestry regimes to enhance transition to climate-smart forestry. Environ. Policy Gov. 32(6), 492–503. [CrossRef]

- Winkel, G., Lovrić, M., Muys, B., Katila, P., Lundhede, T., Pecurul, M., Pettenella, D., Pipart, N., Plieninger, T., Prokofieva, I., Parra, C., 2022. Governing Europe’s forests for multiple ecosystem services: Opportunities, challenges, and policy options. For. Policy Econ. 145, 102849. [CrossRef]

- Živojinović, I., Rogelja, T., Weiss, G., Ludvig, A., Secco, L., 2023. Institutional structures impeding forest-based social innovation in Serbia and Slovenia. For. Policy Econ. 151, 102971. [CrossRef]

- Melnykovych, M., Böttinger, E., Waeber, P., Bertuca, A., De Luca, C., Domínguez, X., Fuentemilla, S., Hernández, S., Heikkinen, H., Kottawa Hewamanage, L., Nijnik, M., Pilla, F., Sarkki, S., Selva, C., Wilson, R., Valero, D., Miller, D., 2024b. Learning needs and gaps of rural communities. Report D.3.1. Horizon Europe Project RURACTIVE—Empowering Rural Communities to Act for Change (2023–2027). GA no. 101084377, pp. 122.

- RURACTIVE, 2023. Empowering rural communities to act for change (2023-2027). Programmes: HORIZON.2.6—Food, Bioeconomy, Natural Resources, Agriculture and Environment; HORIZON.2.6.3—Agriculture, Forestry and Rural Areas. Topic: HORIZON-CL6-2022-COMMUNITIES-02-01-two-stage—Smart solutions for smart rural communities: empowering rural communities and smart villages to innovate for societal change. European Union Framework Programme Horizon Europe. [CrossRef]

- Brantschen, E., Coleman, E., Boillat, S., Feurer, M., Garcia, C.A., Markovic, J., Melnykovych, M., Wilkes-Allemann, J., Waeber, P.O., 2023. An integrated landscape approach to the conservation and restoration of forest landscapes. Schweiz. Z. Forstwes. 174(S1), s12–s20. [CrossRef]

- Baker, S., Mehmood, A., 2015. Social innovation and the governance of sustainable places. Local Environ. 20(3), 321–334. [CrossRef]

- Haxeltine, A., Avelino, F., Wittmayer, J.M., Kunze, I., Longhurst, N., Dumitru, A., O’Riordan, T., 2017. Conceptualising the role of social innovation in sustainability transformations. In: Social Innovation and Sustainable Consumption. Routledge, pp. 12–25.

- Castro-Arce, K., Vanclay, F., 2020. Transformative social innovation for sustainable rural development: An analytical framework to assist community-based initiatives. J. Rural Stud. 74, 45–54. [CrossRef]

- Kluvánková, T., Brnkaľáková, S., Špaček, M., Slee, B., Nijnik, M., Valero, D., Miller, D., Bryce, R., Kozová, M., Polman, N., Szabo, T., Gežík, V., 2018. Understanding social innovation for the well-being of forest-dependent communities: A preliminary theoretical framework. For. Policy Econ. 97, 163–174. [CrossRef]

- Dalla Torre, C., Ravazzoli, E., Dijkshoorn-Dekker, M., Polman, N., Melnykovych, M., Pisani, E., Gori, F., Da Re, R., Vicentini, K., & Secco, L., 2020. The role of agency in the emergence and development of social innovations in rural areas: Analysis of two cases of social farming in Italy and The Netherlands. Sustainability, 12, 4440. [CrossRef]

- Palahí, M., Pantsar, M., Costanza, R., Kubiszewski, I., Potočnik, J., Stuchtey, M., Nasi, R., Lovins, H., Giovannini, E., Fioramonti, L., Dixson-Declève, S., McGlade, J., Pickett, K., Wilkinson, R., Holmgren, J., Trebeck, K., Wallis, S., Ramage, M., Berndes, G., Akinnifesi, F.K., Ragnarsdóttir, K.V., Muys, B., Safonov, G., Nobre, A.D., Nobre, C., Ibañez, D., Wijkman, A., Snape, J., Bas, L., 2020. Investing in nature as the true engine of our economy: A 10-point action plan for a circular bioeconomy of wellbeing. Knowledge to Action 02, European Forest Institute. [CrossRef]

- Hetemäki, L., Hurmekoski, E., 2020. Forest bioeconomy development: markets and industry structures. In: Nikolakis, W., Innes, J. (Eds.), The Wicked Problem of Forest Policy. Cambridge University Press. [CrossRef]

- Boyd, E., Nykvist, B., Borgström, S., Stacewicz, I.A., 2015. Anticipatory governance for social-ecological resilience. AMBIO 44, 149–161. [CrossRef]

- Poulsen, D.V., Stigsdotter, U.K., Refshage, A.D., 2015. Whatever happened to the soldiers? Nature-assisted therapies for veterans diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder: A literature review. Urban For. Urban Green. 14(2), 438–445. [CrossRef]

- da Costa, J.P., Silva, A.L., Barcelò, D., Rocha-Santos, T., Duarte, A., 2023. Threats to sustainability in face of post-pandemic scenarios and the war in Ukraine. Sci. Total Environ. 892, 164509. [CrossRef]

- Muiderman, K., Zurek, M., Vervoort, J., Gupta, A., Hasnain, S., & Driessen, P. (2022). The anticipatory governance of sustainability transformations: Hybrid approaches and dominant perspectives. Global Environmental Change, 73, 102452. [CrossRef]

- European Commission, 2022. European Commission: European Research Executive Agency, New European Bauhaus—Beautiful—Sustainable—Together. Publications Office of the European Union. [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Economy of Ukraine, 2024. Ukraine Facility Plan 2024–2027. URL: https://www.ukrainefacility.me.gov.ua/en/.

- Milakovsky, B., 2024. The role of wood construction in Ukraine’s recovery: Overview of strategies and initiatives. March 2024 Report. URL: https://ua.fsc.org/sites/default/files/2024-05/Wood_in_recovery_EN_web.pdf.

- Melnykovych, M., Nijnik, M., Sarkki, S., 2020. A perspective of innovative multifunctional forestry for societal benefits: a focus on Ukrainian Carpathians. IUFRO Conference, 7–8 October 2020, Bolzano. https://www.iufro2020.eurac.edu/.

- Nijnik, M., 2010. Carbon capture and storage in forests. In: Hester, R.E., Harrison, R.M. (Eds.), Carbon Capture: Sequestration and Storage. Issues in Environmental Science and Technology, vol. 29. The Royal Society of Chemistry, Cambridge, pp. 203–238.

- United Nations, 2015. Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. URL: https://sdgs.un.org/sites/default/files/publications/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf.

- UNECE, FAO, 2021. Forest Landscape Restoration in Eastern and South-East Europe. Background Study for the Ministerial Roundtable on Forest Landscape Restoration and the Bonn Challenge. ECE/TIM/DP/87. URL: https://unece.org/sites/default/files/2021-07/2106522E_WEB.pdf.

- UNEP, FAO, 2021. United Nations Decade on Ecosystem Restoration 2021–2030. URL: https://www.decadeonrestoration.org/.

- European Commission, 2023. European Commission: Directorate-General for Environment, Guidelines on closer-to-nature forest management. Publications Office of the European Union. [CrossRef]

- Achasova, A.O., Achasov, A.B., 2024. The European Green Deal and prospects for Ukraine. Man Environ. Issues Neoecol. (41), 33–56. [CrossRef]

- Metsähallitus, 2024. History of forestry. Available at: https://www.metsa.fi/en/about-us/organisation/history/history-of-forestry/ (accessed 15 October 2024).

- Määttänen, A.M., Virkkala, R., Leikola, N., Aalto, J., Heikkinen, R.K., 2023. Combined threats of climate change and land use to boreal protected areas with red-listed forest species in Finland. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 41, e02348. [CrossRef]

- Martino, S., Martinat, S., Joyce, K., Poskitt, S., Nijnik, M., 2024. A classification and interpretation of methodological approaches to pursue natural capital valuation in forest research. Forests 15, 1716. [CrossRef]

- Hamor, F., 2023. Ecodiamonds of Europe: History of beech primeval forests nomination to the UNESCO World Heritage List. Prostir, Lviv, pp. 299.

- Adams, C., Rodrigues, S.T., Calmon, M., Kumar, C., 2016. Impacts of large-scale forest restoration on socioeconomic status and local livelihoods: What we know and do not know. Biotropica 48(6), 731–744. [CrossRef]

- Padovezi, A., Secco, L., Adams, C., Chazdon, R.L., 2022. Bridging social innovation with forest and landscape restoration. Environ. Policy Gov. 32(6), 520–531. [CrossRef]

- Kruhlov, I., Thom, D., Chaskovskyy, O., Keeton, W.S., Scheller, R.M., 2018. Future forest landscapes of the Carpathians: Vegetation and carbon dynamics under climate change. Reg. Environ. Change 18, 1555–1567. [CrossRef]

- Ludvig, A., Rogelja, T., Asamer-Handler, M., Weiss, G., Wilding, M., Živojinović, I., 2020. Governance of social innovation in forestry. Sustainability 12, 1065. [CrossRef]

- Secco, L., Favero, M., Masiero, M., Pettenella, D.M., 2017. Failures of political decentralization in promoting network governance in the forest sector: Observations from Italy. Land Use Policy 62, 79–100. [CrossRef]

- Olsson, P., Folke, C., Berkes, F., 2004. Adaptive comanagement for building resilience in social–ecological systems. Environ. Manag. 34, 75–90. [CrossRef]

- Chaffin, B.C., Gunderson, L.H., 2016. Emergence, institutionalization and renewal: rhythms of adaptive governance in complex social-ecological systems. J. Environ. Manag. 165, 81–87. [CrossRef]

- Gunderson, L.H., Holling, C.S. (Eds.), 2002. Panarchy: Understanding Transformations in Human and Natural Systems. Island Press, Washington, DC, USA.

- Walker, B.H., Gunderson, L.H., Kinzig, A.P., Folke, C., Carpenter, S.R., Schultz, L., 2006. A handful of heuristics and some propositions for understanding resilience in social-ecological systems. Ecol. Soc. 11(1), 13. Available from: http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol11/iss1/art13/.

- Spitz, R., 2024. How anticipatory governance can help us with unpredictability. World Economic Forum. URL: https://www.weforum.org.

- Katila, P., et al. (Eds.), 2024. Restoring forests and trees for sustainable development: Policies, practices, impacts, and ways forward. Oxford Academic, New York, NY. [CrossRef]

- Loveridge, R., Marshall, A.R., Pfeifer, M., Rushton, S., Nnyiti, P.P., Fredy, L., Sallu, S.M., 2023. Pathways to win-wins or trade-offs? How certified community forests impact forest restoration and human wellbeing. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 378(1867), 20210080. [CrossRef]

- Špaček, M., Melnykovych, M., Kozová, M., Pauditšová, E., Kluvánková, T., 2022. The role of knowledge in supporting the revitalization of traditional landscape governance through social innovation in Slovakia. Environ. Policy Gov. 32(6), 560–574. [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.M.A., Balvanera, P., Benessaiah, K., Chapman, M., Díaz, S., Gómez-Baggethun, E., Gould, R., Hannahs, N., Jax, K., Klain, S., Luck, G.W., Martín-López, B., Muraca, B., Norton, B., Ott, K., Pascual, U., Satterfield, T., Tadaki, M., Taggart, J., Turner, N., 2016. Why protect nature? Rethinking values and the environment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 113(6), 1462–1465. [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Baggethun, E., Corbera, E., Reyes-García, V., 2013. Traditional ecological knowledge and global environmental change: Research findings and policy implications. Ecol. Soc. 18(4), 72. [CrossRef]

- Palomo, I., González-García, A., Ferraro, P.J., et al., 2024. Business-as-usual trends will largely miss 2030 global conservation targets. Ambio. [CrossRef]

- Garcia, C.A., Savilaakso, S., Verburg, R.W., Gutierrez, V., Wilson, S.J., Krug, C.B., Sassen, M., Robinson, B.E., Moersberger, H., Naimi, B., Rhemtulla, J.M., Dessard, H., Gond, V., Vermeulen, C., Trolliet, F., Oszwald, J., Quétier, F., Pietsch, S.A., Bastin, J.-F., Waeber, P.O., 2020. The global forest transition as a human affair. One Earth 2(5), 417–428. [CrossRef]

| Dimensions | Steps | Type of analysis | Sources of information |

| Nature of the crisis | Definition (pre-war challenges and war-induced crises) | Literature review (scientific publications and grey literature) | Web of Science; Google Scholar; government websites |

| Expert interviews | Ukrainian researchers, government officials and representatives of NGOs, n=7 | ||

| Forest policy document analysis Data from National Statistics |

IUFRO report from Forum on Ukraine Forest Science and Education: Needs and Priorities for Collaboration (2024) [48]; FOREST EUROPE report on Ukraine`s forest recovery [49], WB reports on Ukraine [50,51], OECD report on Ukraine, State Forest Management Strategy of Ukraine until 2035 [52]; FAO Forestry Support Strategy for Ukraine 2023–2027 [53]. Official information on forests of Ukraine—https://forest.gov.ua/en |

||

|

Scope of the crisis |

Identification of root causes | Literature review (scientific publications and grey literature) | Web of Science, Google Scholar, survey of peer-reviewed publications, Ukrainian government and NGOs reports |

| Assessment of the impacts | Forest cover change | Official data from Ecozagroza online platform; data from SFRA; website of the Ukrainian state forest management planning association “Ukrderzhlisproekt”—Remote Sensing Based Inventory—National Forest Inventory | |

| Fires and area burned | State Emergency Service of Ukraine (SESU) Regional Eastern Europe Fire Monitoring Center (REEFMC) Landscape Fires Advisory Bulletin—https://nubip.edu.ua/node/9087/2 |

||

| Society | ZOI Environmental Network, Copernicus Dynamic Land Cover map, Emerald Network, grey literature, and expert interviews (n=7) | ||

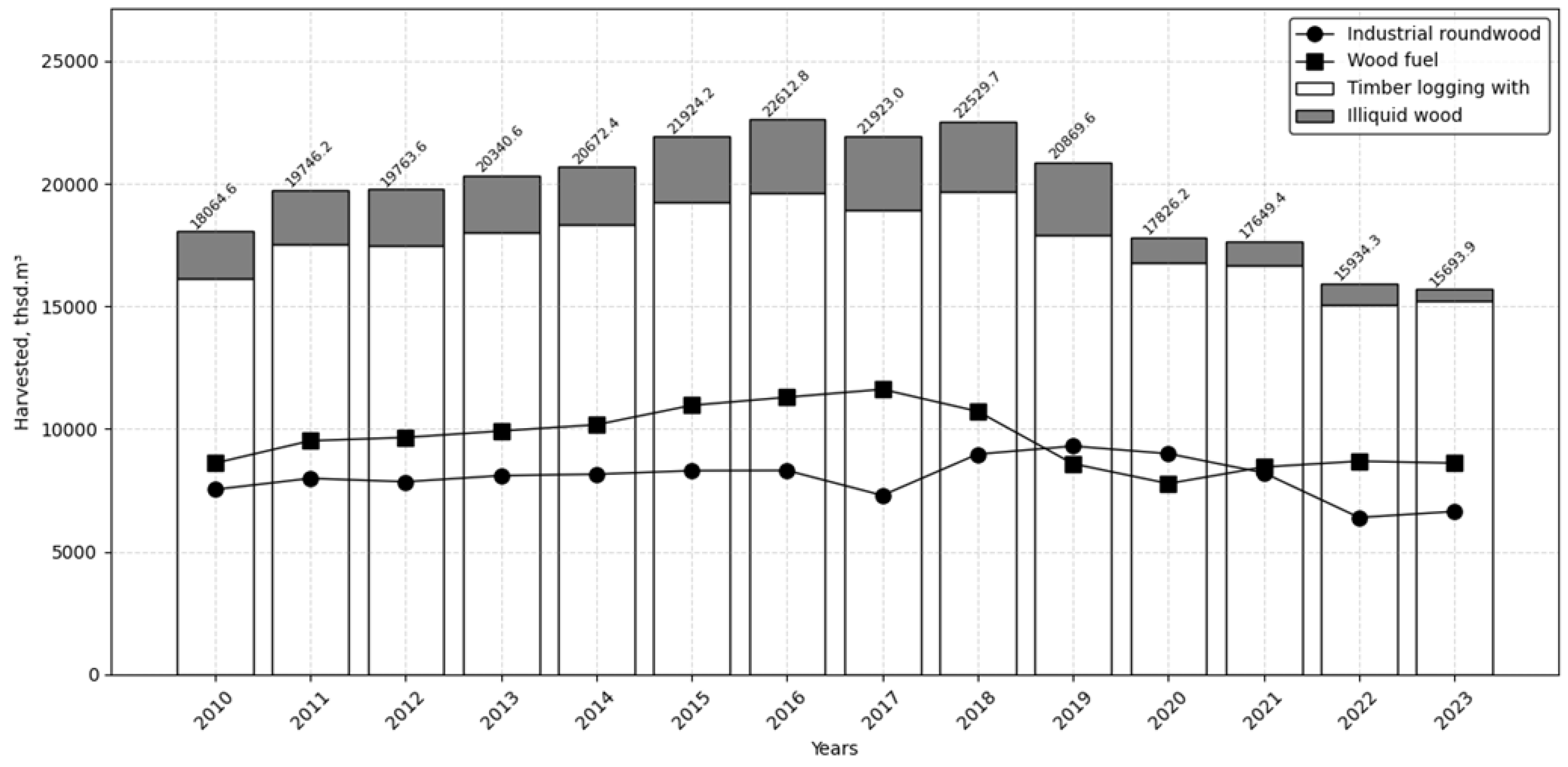

| Economy | Forest statistics, UKRstat webpage | ||

| Governance | Scientific publications, IUFRO report on Ukraine Forum “Forest Science and Education: Needs and Priorities for Collaboration” [54], and results of the discussion hold during special session at IUFRO World Congress on Ukraine`s forest (2024); Ukraine`s forest policy regulations and amendments to law due to martial order (2022–2024); reports of international organisations and programs (e.g., FAO, WB, WWF, UNECE) |

||

| Resolution of the crisis: Recovery pathways | Evaluation of actions/ responses in place; suggestion of recovery pathways |

Literature review and current policies; expert interviews Thematic analysis (QDA Miner Lite) |

Web of Science; Google Scholar Reports [48,49,50,51,52,53] Interview with Ukrainian researchers, forest related professionals and government and NGOs representatives (n=7) |

| Notes: Analytical framework based on three system dimensions. Each aspect can consist of one or more steps and each step details the analysis and sources of information. | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).