1. Brief Review of Our Previous Results Concerning the Ether

In this article, we build on our previous results starting with the discovery of Errors 1 and 2 in Michelson’s analysis of his interferometer experiments of 1881/87 (ME1881/87).

By correcting

Errors 1 and 2 in Michelson’s analysis of his interferometer experiments ME1881/87, it was possible to reintroduce the ether (ET) into physics in 2016 in the form of our ether model (HM16) [

1], which was subsequently completed and improved [

2,

3,

4,

5], an operation that will inexorably continue.

However, the presence of ether in physics has already led, in our previous work, to a series of important consequences, including the establishment of the origin of the interaction between submicroparticles (SMPs), as periodic percussion forces pi created by the vibrations of any SMP, transmitted through the fundamental vibrations (FVs) of the ether.

The resultant

FCC (completed Coulomb force) of percussion forces

pi can be expressed as a series of powers in 1/

rn but with the first term in –ln

r [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10].

Therefore, the interaction force between two electric dipoles (

FDC) also results as a series of powers in 1/

rn with the first term in 1/

r2, which depend on the electrical constants of matter/SMP/ET, ε

0,

p, [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10], and not on

G (from the Newton force (

FN)). This

FDC force is always of an attractive nature, and therefore replaces Newton’s gravitational force

FN.

Moreover, at astronomical distances, the force

FDC is approximately 60% greater than the force

FN, which allows us to abandon the hypothesis of dark matter (DM) [

11].

However, the presence of ET was questioned, initially by Michelson’s analysis/misinterpretation of the results of his ME1881/87; then, on the basis of these errors, the presence of ET was contested by the special theory of relativity (SRT) proposed by Einstein in 1905, a trend that has continued to this day by the mainstream of physics.

However, since the beginning of the ET contestation, there have been numerous other opinions and arguments supporting the presence of ET, of which, very credibly, is that of Professor Laughlin in 2005, who says, “The modern concept of the vacuum of space, confirmed every day by experiment, is a relativistic Ether. But we do not call it this because it is not accepted (taboo)” [

12].

However, all such opinions in favor of the presence of ETs lacked a decisive argument, which we just discovered and demonstrated: the existence of Errors 1 and 2 in Michelson’s analysis of ME1881/87, followed by their correction.

However, an error existing in a scientific document must invalidate all results based on it, which is the case for ME1881/87, which requires mandatory correction, a fact/operation that has not been carried out to date.

Importantly, the problem of the existence of ET has preoccupied thinkers since antiquity when Aether (in Greek) was considered the fifth element of nature, along with earth, water, air and fire, without knowing its physical properties, including its density.

However, this concern regarding the functioning of ET continued more intensely in the classical period of physics, when the most important scientists, including Newton, Maxwell, Lorenz, etc., approached the subject of ET by developing numerous and complex models of ET, but obviously, without being able to know its density.

However, Fresnel nevertheless addressed the problem of ET density but did not obtain any concrete results, since in his calculation, the density ρ

E was eliminated by simplification, as Barbulescu shows [

13].

Notably, a more functional model of the ET can be considered the one initially proposed in 1690 by the Englishman Fatio but which was resumed, developed and completed in 1748 by the Frenchman Lesage [

14]. This model actually aims to explain the F

N force, which is based on the shocks on real matter, by a continuous flow in space, of small special particles that circulate at high speeds in any direction and which constitute the universal ether itself.

This model for gravity, and therefore for Ether, was the basis for numerous additions and refinements or criticisms throughout the following period until 2005 and even today, in which numerous scientists were involved, including Cramer, Euler, Bernoulli, Laplace, Poincare, Boskovich, Kant, Kelvin, Maxwell, Thomson, Whittaker, Huygens, Lorentz, Gamow, Feynman, Larmor, FitzGerald, [

14], the Romanian Popescu [

15], and many others.

All these scientists were convinced that in nature, there exists a matter called Ether, but for which they could not develop a form/model that would answer all the relevant questions, including ET density.

Therefore, the present research is fully justified and useful as a step forward in physics.

However, these results were possible only after the discovery and correction of Errors 1 and 2 in Michelson’s analysis within ME1881/87.

IMPORTANT NOTE. The phenomenon in [

10], in which the extra mass m

s of an SMP is produced, moving at speed v through the ET but entraining the surrounding ET at a speed v

E, accumulating energy E

s equivalent to the mass m

s, constitutes the first strong evidence for the presence of ET in nature.

2. Brief Review of Our Previous Results Concerning the Nature of Mass

However, the presence of ET showed that the mass

m of any SMP is constituted by the kinetic and potential energy initially transmitted at the creation of the SMP, in the own vibrations of the constituent Ether cells (EC), from inside the SMP [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10].

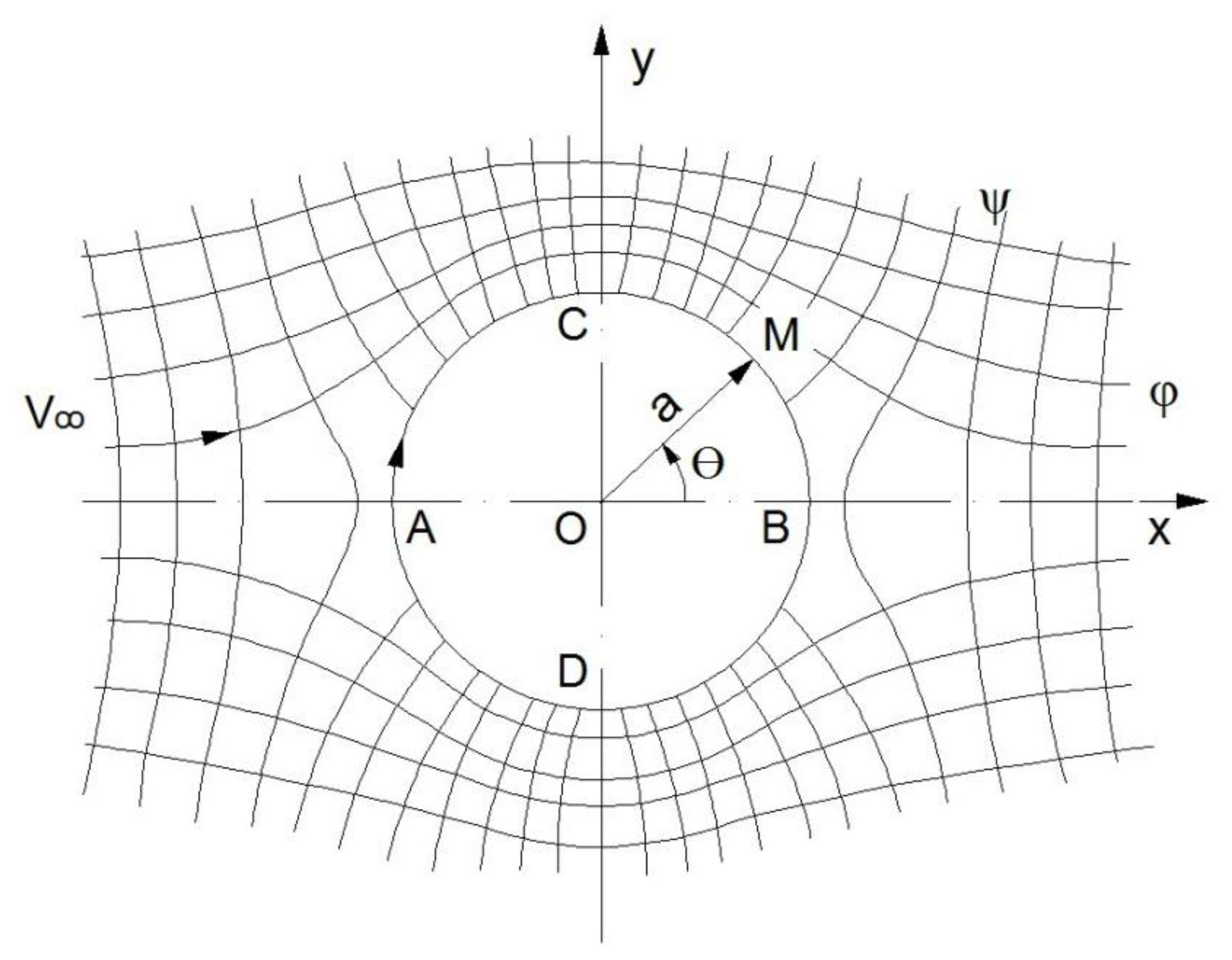

As a physical model that can reproduce the movement in the ET of an SMP with a spherical shape, a model of the flow of an ideal fluid around a circular cylinder, whose equations of motion are given by the theory of potential motions of a perfect fluid from hydrodynamics, was adopted.

The hydrodynamic spectrum of the fluid’s motion, represented by the streamlines ψ and the equipotential lines φ, with the fluid moving with velocity

V (as in [

16] along the O

x axis around the circular cylinder of radius

a), is shown in

Figure 1.

This motion results from the superposition of the complex potential (as a function of

z =

x +

iy) of a parallel current in the

x direction (

z=

x), with the velocity at infinity

V∞, and that of a dipole (doublet, from 2 sources

Q) of magnitude (momentum)

m=2

aQ, therefore with radius

a, described by the following formula [

16]:

In this case, the surface of the cylinder is acted upon exclusively by orthogonal pressure forces but is symmetrical in the x- and y-directions, so their resultants are zero in both directions, and the cylinder is not driven by the perfect fluid in motion around it.

The maximum positive pressure occurs at points A and B (

Figure 1), with values of [

16]

The maximum negative pressure occurs at points C and D, with values of

However, it is known that in real situations, the cylinder is driven by any (real) fluid, a phenomenon known as the Euler‒D’Alembert paradox.

To solve this situation, we will need to know the ET density ρE.

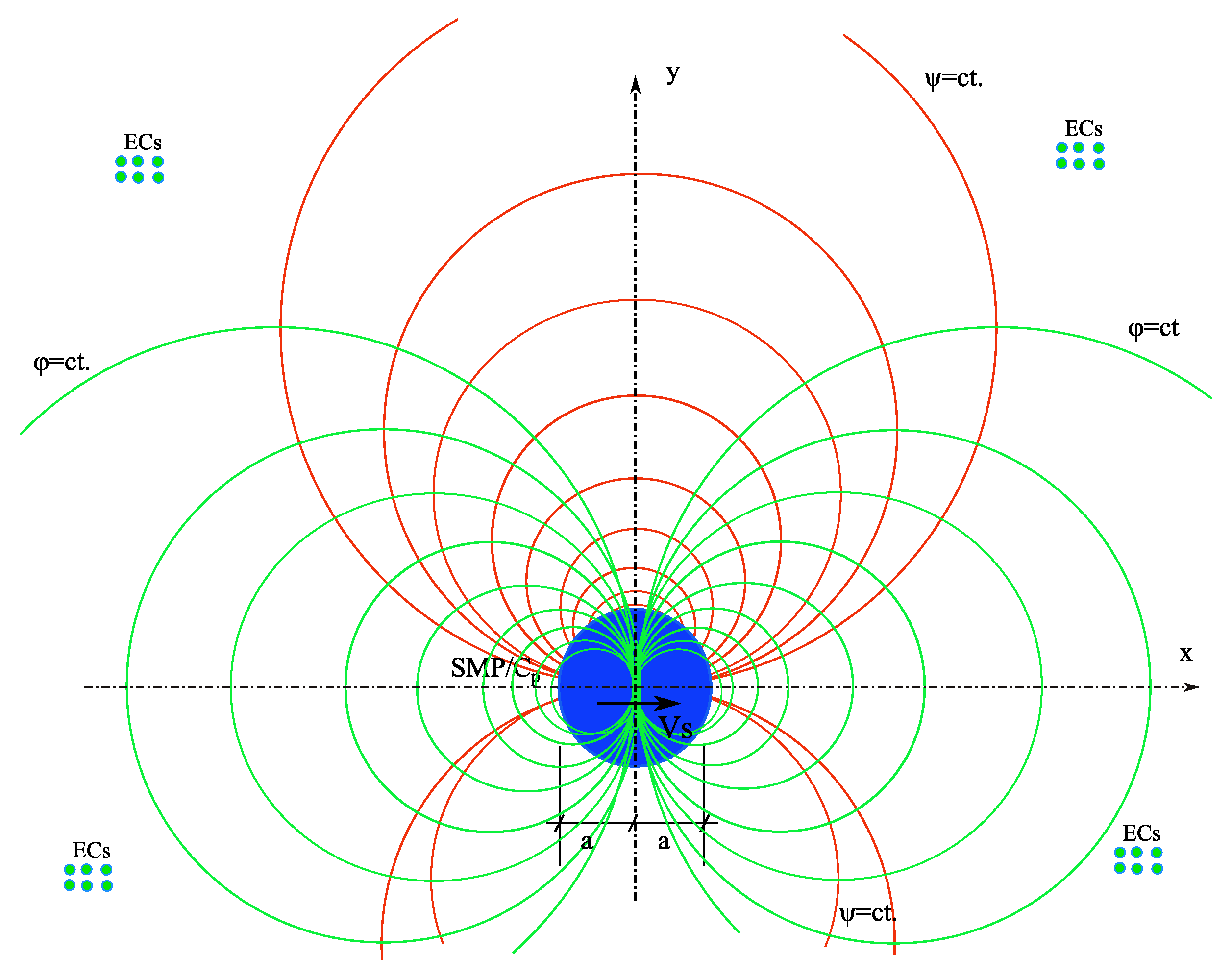

For this purpose, we study our case of a stationary ether but with a long cylinder moving with speed

V∞ along the

Ox axis. This case can be modeled by superimposing on the above case of a moving fluid (

Figure 1), a new movement of equal speed but opposite direction ‒

V∞, thus resulting in the case of moving with velocity

v in the

Ox direction of a cylinder in a stationary fluid. However, in this situation, the surrounding fluid/ether is set in local motion with velocity

v around the moving cylinder (

Figure 2) [

16].

The component of the velocity

v of the fluid in the

Ox direction is [

16]:

The hydrodynamic spectrum of these cylinder movements in Ether is shown in

Figure 2.

However, here (

Figure 2), we can limit ourselves to the case of the problem in a plane, corresponding to a long cylinder, as being equivalent to the spatial problem of a spherical SMP.

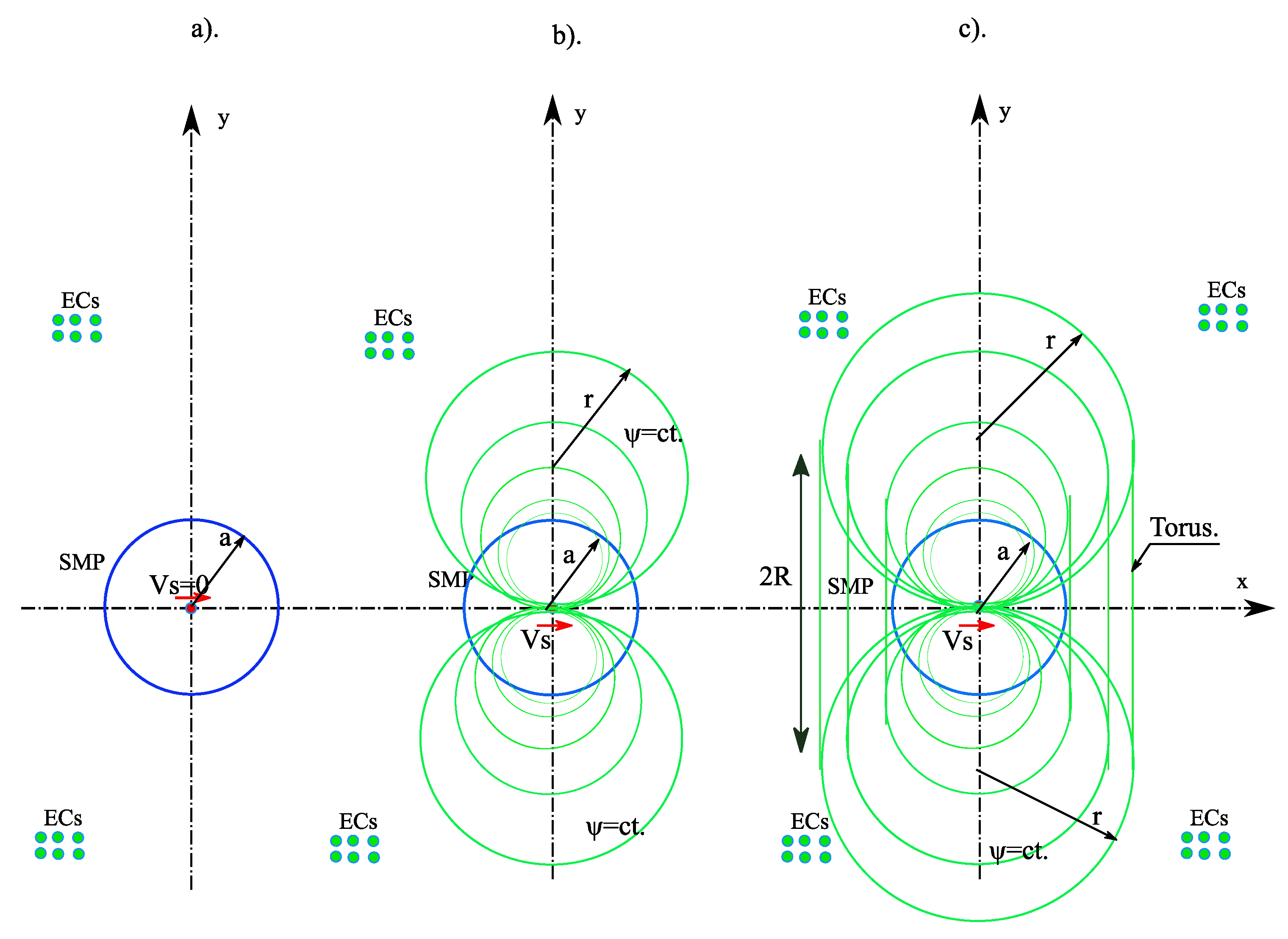

Therefore, in [

10], real streamlines with interstices having interspaces with surfaces of complicated shape (

Figure 2) were replaced by circular semicrown curves with the same total surface in order to be able to carry out an approximate simplified numerical calculation of the surfaces and therefore also of the volumes

Ci of the ether moving at different velocities

vi (Figure 5 from [

10]).

However, here, we will leave that procedure of replacement of surfaces (

Figure 3b), and we will adopt the calculation of the quantities/volumes C

i of ET around the SMP considered spherical, as volumes of tori that surround the SMP (as we do in

Methods) and which in section correspond to the streamlines ψ (

Figure 3c).

Therefore, the suplementary mass

ms of the SMP due to speed

v is due to the kinetic energy

Ec accumulated in the entrained ether surrounding the SMP, in the form of a torus, with a value of

v decreasing toward zero with increasing distance

r (

Figure 3c).

In [

10], for the total kinetic energy

EE of all surfaces/volumes of ether,

Ci with velocities

vEi, the following relation was obtained:

In Equation (4),

Ct represents the total quantity/mass of ET drawn by the SMP, which in [

10] was considered by the total area/volume of Ether, denoted by

Ct but without highlighting the density of ET.

In (4), the mean/average velocity vme of the entire amount of ET in motion around the SMP was introduced for simplicity, allowing us to drop the coefficient ½ from the energy formula in classical mechanics.

In [

10], we obtained the additional mass

ms due to ET motion with speed

vE =

vme as:

IMPORTANT NOTE. The above result in (4b) constitutes proof of the presence/existence of ET through the appearance of the supplementary mass ms of material particle SMPs with their movement.

However, this phenomenon is studied today by applying a Lorentz-type law, from current physics, a situation where there is no other physical/material/real explanation for the appearance of this supplementary mass, but only by the simple movement of the SMP through the space/vacuum, without any intervening force, phenomenon that resembles a miracle.

3. Ether Density Calculation Through the Supplementary Mass ms

For use in the following calculations of the density ρ

E of ET, we can write the magnitude of the mass of ET in motion as equivalent to the amount

Ct of ET entrained by the SMP moving at speed

v, from [

10].

Now, according to the classical definition of the density ρ

E of ET, we can write, in the present case of the spatial problem, taking into account the total quantity

Ct of ET in motion with its (average) speed

v =

VE,

Inserting (5) into (4), we obtain

However, from classical physics, we have the Lorentz formula for the variation in mass with velocity:

Moreover, for the additional Lorentz-type mass

msL, using Equation (8), we can also write

Using the classic notation

v/c = β and calculating the expression in parentheses in (9), we obtain

Now, we can make the following observations, with two cases being possible:

a) If there was no ET, there would only be motion of the SMP in space/vacuum with velocity vP, and in that case, there would be no physical/mechanical justification for the appearance of the variation in the mass of the SMP through the Lorentz effect. Therefore, mSL=0, and the energy of the SMP remains E=mvP2, so m=const.

b). In the case of the presence of ET in space (HM16), the entrainment of ET around the SMP will occur, and ET (special matter) should have a mass mE, which moves with the speed vE = vP on contact with the SMP but with vE=0, at infinity, and with a negligible value at a certain distance. The Lorentz effect will apply to the volume of ET in motion, resulting in the supplementary mass mEs of the entrained ET by the SMP, with velocity vE (mean).

The real case is b), and the balance of moving masses related to the SMP can be written as follows:

From Equation (11), we obtain the following expression for the supplementary mass

mEs of the SMP created by the ET trained by the SMP:

In Equation (12), we define the notation:

where the coefficient A

1 is a function that depends only on the velocity

vP of the SMP.

From (12), via the classical definition of the ether density ρ

E of volume

VE, we obtain

where

VEcor represents the volume of ET entrained by the SMP but corrected according to the relative velocity β=

vE/

c (average

vE) according to (5).

For the calculation of the density of the ET in (14), we need to evaluate both the volume VE of the ET entrained by the SMP and the expression A1 in (13), which depends on the average velocity vE of the ET.

To correct the volume

VE of ET with the expression

A1 in Equation (13), we will numerically calculate the values of

A1, and the results are shown in

Table 1 (from

Methods).

To find the radius

rE of the volume of Ether V

E driven with a significant speed by an SMP, we will utilize the speed variation

v, with the distance

r, using the theory of potential motions for the case of the movement of an SMP in the ET, which we will assimilate to the case of the movement of a cylinder of radius

a, with the speed

v through a perfect fluid (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

For this case, starting from Equation (1), we can write the velocity

v [

16] in the horizontal

Ox direction (

Figure 2) as:

The maximum of

v will occur at points on the surface of the SMP, therefore having radius

r=

a; at point

C0 with coordinates (0,

a) and the velocity here,

vC0 will be, from (15),

Thus, the velocity

vC1 at distance 1.

a from the surface of the SMP at point

C1 with coordinates (0, 2

a) will be

To calculate the velocity

vCi at points

Ci located at various distances

ri ≥

a, from the center

O of the SMP, we use Equation (15), and we numerically calculate the values of the relative velocity β=

vCi/vP along the

Oy axis (

Figure 2), where we have

x=0 and

y=

ia, with

i = 1, 2, 3, 4, …. :

The number of intervals

i to the edge of the moving ET sphere/cylinder will be

and in particular cases, the relative velocity

vCi/

vp at a distance of

ia from the SMP surface at points

Ci with coordinates (0,

ia) will be those shown in

Table 2, column (7) (from

Methods).

Therefore, at point

Ci on the

Oy axis (

Figure 3), which is located at increasing distances in arithmetic progression of

I, the velocities of ET and

vCi increasingly decrease according to Equation (19).

4. The Case of the Hydrogen Atom (from Methods)

For the first example, we consider the case of the smallest atom, H, for which we know the following:

-its mass, practically the mass of the proton:

-the radius of the proton:

-the radius of the H atom,

rAH, which, according to Wikipedia [

17], is a function of the nucleus radius

rNu, approx. 10

4×

rNu.

However, there are values measured for the

a-radii (

Figure 2), for various elements, so that for H, we have [

17]

We chose from [

17] the minimum value for the isolated atom, which is the most representative in high-speed experiments.

4.1. Case H1: β=0.01, i= 2

For the usual speeds in laboratory experiments of approx. β=0.01, the

vP of SMP/H is:

The volume

VE of the torus of the ET driven by the SMP will be considered here as the theoretical volume (

Figure 3c) in the form of an external torus minus the volume of the SMP.

The torus volume is as follows:

In our case (

Figure 3c), the torus is the minimal one, with

R=

r, and its volume is as follows:

The volume of the SMP sphere is as follows:

The ratio of the volume torus/sphere will be

-The radius of the torus of the volume of ET driven by SMP/H, rED, we initially consider, in this case, to be double, i=2, the radius a of the particle, so rED=i×a=2a.

The radius

rED of the torus of the ET driven by the hydrogen atom (

Figure 3c) is:

For this radius, here initially results a minimum speed

vmi, given by β=0.01, of ET driven by SMP/H, according to

Table 2 (col. 6).

Therefore, the volume of the torus of ET (

Figure 3c), significantly driven by SMP/H, via (20), is as follows:

We will now calculate the volume

VEcor of the torus, corrected with the coefficient

A1, according to Equation (14) and

Table 1 (col. 6), for β=0.01.

However, for the calculation of A1, only the mean speed vme of the volume of the mobile ET must be considered, assuming a linear variation in the ET velocity v:

vme=1/2×(3000+750)=1875 km/s, respectively, the average speed relative to

c:

The correction coefficient

A1 according to

Table 1 (rows 1, 2) will be (after linear interpolations, successively for β and for

A1, resulting in the correction factor

x for

A1):

The corrected torus volume is as follows:

Now, the basic density ρ

E of the ET will be by definition:

4.2. Case H2: β=0.01, i =8

Here, we take the relative speed to β=0.10, so vP=0.10x300,000=30,000 km/s.

Here, we conduct the calculations similarly to those in Case H1 (without reproducing in detail).

To reduce the ET speed to the same minimum acceptable value of v

mi=46.8 km/s, we choose

i=8, resulting in:

The volume of the ET torus (

Figure 3c), significantly driven by SMP/Ba, via (20) is as follows:

The average speed v

me becomes:

The correction coefficient A

1 after interpolation is as follows:

The torus volume of ET, V

Ecor corrected:

4.3. Case H3: β=0.3, i=44

Here, we take the relative speed to β=0.30, so vP=0.30x300,000=90,000 km/s.

Here, we conduct the calculations similarly to those in Case H2 (without details), resulting in:

To reduce the ET speed to the same minimum acceptable value of v

mi=46.8 km/s, we calculate the required radius r

C simplified via Equation (19), resulting in:

We choose

i=44, resulting in:

The volume of the ET torus (

Figure 3c), significantly driven by SMP/Ba, via (20) is as follows:

The average speed v

me becomes:

The correction coefficient A

1 after interpolation is as follows:

The torus volume of ET, V

Ecor corrected:

5. The Situation with Barium Atom B (from Methods)

For comparison, we consider the situation in which the SMP of the barium atom Ba, located in the middle of the Mendeleev Table, has an atomic number of 56, for which we know the following:

-its rest mass, as a function of the mass number A=137.34:

-the radius of the Ba atom (

Figure 3), which, according to classical physics, is [

17]:

5.1. Case Ba1, β=0,010, i=2

For low speeds, which are common in laboratory experiments of approx. β=0.01, the particle speed v

P results:

The torus radius (Fg.3c) of the volume of ET entrained/driven by SMP/Ba, r

ED, is considered to be the double,

i=2, of the particle radius

a, so r

ED = r

EBa =i×a=2a:

and where we assume that the minimum speed v

mi=v

C of ET entrained by SMP/Ba is reached, according to

Table 2 (row (2), col. (6)):

However, now, we calculate the volume of the ET torus, which is significantly driven by SMP/Ba, via Equation (20):

However, the mean speed v

me of the torus volume of ET entrained results by assuming an approximately linear variation in the ET speed between the two edges/limits:

The average relative speed β

me results:

The correction coefficient A

1 according to

Table 1 is as follows (after linear interpolation for β):

The torus volume of ET and V

Ecor corrected with A

1 according to eq (12) is as follows:

The corrected/final density according to Equation (12), ρ

E, of ET will result by definition:

5.2. Case Ba2: β=0.010, i=8

Here, we take the relative speed to β=0.10, so vP=0.10x300,000=30,000 km/s.

Here, we conduct the calculations similarly to those in Case Ba1 (without reproducing in detail), resulting in the following:

To reduce the ET speed to the same minimum acceptable value of v

mi=46.8 km/s, we calculate the required radius r

C simplified via Equation (19), resulting in:

We choose

i=8, resulting in:

The volume of the ET torus (

Figure 3c), significantly driven by SMP/Ba, via (20) is as follows:

The average speed v

me becomes:

The correction coefficient A

1 after interpolation:

The torus volume of ET, V

Ecor corrected:

5.3. Case Ba3; β=0.30, i=44

Here, we increase the relative speed to β=0.30, so vP=0.30x300,000=90,000 km/s.

Here, we conduct the calculations similarly to those in Case Ba2 (without reproducing in detail), resulting in the following:

To reduce the ET speed to the same minimum acceptable value of v

mi=46.8 km/s, we calculate the required radius r

C simplified via Equation (19), resulting in:

We choose

i=44, resulting in:

The volume of the ET torus (

Figure 3c), significantly driven by SMP/Ba, via (20) is as follows:

The average speed v

me becomes:

The correction coefficient A

1 after interpolation is as follows:

The torus volume of ET, V

Ecor corrected:

5.4. Case Ba4 β=0.60, i=62

Here, we increase the relative speed to β=0.60, so vP=0.60x300,000=180,000 km/s.

Here, we conduct the calculations similarly to those in Case Ba2 (without reproducing in detail), resulting in the following:

To reduce the ET speed to the same minimum acceptable value of v

mi=46.8 km/s, we calculate the required radius r

C simplified via Equation (19), resulting in:

We choose

i=62, resulting in:

The volume of the ET torus (

Figure 3c), significantly driven by SMP/Ba, via (20) is as follows:

The average speed v

me becomes:

The correction coefficient A

1 after interpolation is as follows:

The torus volume of ET, V

Ecor corrected:

5.5. Case Ba5 β=0.90, i=76

Here, we increase the relative speed to β=0.90, so vP=0.90x300,000=270,000 km/s.

Here, we conduct the calculations similarly to those in Case Ba2 (without reproducing in detail), resulting in the following:

To reduce the ET speed to the same minimum acceptable value of v

mi=46.8 km/s, we calculate the required radius r

C simplified via Equation (19), resulting in:

We choose

i=76, resulting in:

The volume of the ET torus (

Figure 3c), significantly driven by SMP/Ba, via (20) is as follows:

The average speed v

me becomes:

The correction coefficient A

1 after interpolation is as follows:

The torus volume of ET, V

Ecor corrected:

5.6. Case Ba6, β=0.97, k=79

Here, we increase the relative speed to β=0.90, so vP=0.97x300,000=291,000 km/s.

Here, we conduct the calculations similarly to those in Case Ba2 (without reproducing in detail), resulting in the following:

To reduce the ET speed to the same minimum acceptable value of v

mi=46.8 km/s, we calculate the required radius r

C simplified via Equation (19), resulting in:

We choose

i=79, resulting in:

The volume of the ET torus (

Figure 3c), significantly driven by SMP/Ba, via (20) is as follows:

The average speed v

me becomes:

The correction coefficient A

1 after interpolation is as follows:

The torus volume of ET, V

Ecor corrected:

6. Systematization of the Results of Calculations of ρE (from Methods)

Table 3 shows that for the density ρ

E of the ET, a series of three values were obtained for the hydrogen atom, and six values were obtained for the barium atom.

a). Rows 1. For both H and Ba, the values in

Table 3 were calculated for a particle velocity β=

vP/

c=0.01 (

vP=3000 km/s) and an initial torus radius of the ET volume, which was chosen arbitrarily initially by the distance coefficient

i=2. However, this radius proved insufficient for reducing the marginal velocity

vC to a negligible value compared with the velocity

vP of the SMP. This is because, from

Table 2,

vC/

vP=0.25=25% (vC=750 km/s), a percentage far too high to be negligible. Therefore, for this case, a density ρ

E of ET on the order of 1.0×10

‒2 kg/m

3 is not realistic.

b). Rows 2. Then, for both H and Ba, the values were also calculated for β=0.01, but for a radius of the torus of volume VE of ET, given by the distance coefficient i=8. This coefficient was determined by calculation to obtain a minimum marginal speed vmin=vC=46.8 km/s.

This value of vC was negligible compared with the velocity vP of the SMP (vP=3000 km/s), i.e., vC/vP=0.0156=1.56%. The velocity vC=46.8 km/s, or a percentage of 1.56%, was then considered negligible compared with vP (in the sense of engineering, since it was less than 2%). Therefore, for this case, a density ρE of ET on the order of 0.30×10‒4 kg/m3 (for Ba) and 0.130×10‒3 kg/m3 (for H) can be considered realistic.

c). Rows 3. Then, for both H and Ba, the values were calculated for β=0.30 (vP= 90000 km/s). However, we now calculate for a torus radius of volume VE of ET given by the distance coefficient i=44, which was determined by calculation, precisely to obtain the same marginal velocity vC = 46.8 km/s, which can be considered negligible. Therefore, for this case, the density ρE of ET on the order of 1.80×10‒4 kg/m3 (for Ba) and 3.0×10‒3 kg/m3 (for H) can be considered realistic.

d). Row 4. Then, for Ba, the values were calculated for β=0.60 (vP=180000 km/s) but for a torus radius of volume VE given by the distance coefficient i=62, which was determined by calculation, precisely to obtain the same marginal velocity vC=46.8 km/s. Therefore, for this case, the density ρE, which is on the order of 2.35×10‒4 kg/m3, can be considered realistic.

e) Row 5. Then, for Ba, the values were calculated for the velocity β=0.90 (vP= 270000 km/s), but for a torus radius of volume VE given by i=76, which was determined by calculation, precisely to obtain the same marginal velocity vC=46.8 km/s. Therefore, for this case, the density ρE, which is on the order of 3.30×10‒4 kg/m3, can be considered realistic.

f). Row 6. For the Ba atom, the values were subsequently calculated for the velocity β=0.97 (vP=291000 km/s), but for a torus radius of volume VE given by i=79, which was determined by calculation, precisely to obtain the same marginal velocity vC = 46.8 km/s. Therefore, also for this case, the density ρE of the ET, which is on the order of 3.40×10‒4 kg/m3, can also be considered realistic.

In

Table 3, a slight monotonic increase in the calculated density ρ

E with increasing speed β (from 0.01 to 0.97) is observed. However, the density of ET remains near ρ

E=2.0×10

‒4 kg/m

3, which can be considered realistic.

This small increase in the calculated density ρE of ET can be explained by increased pressures in the surrounding ET as an effect of the increased ET speed toward limit c.

Of course, the method presented above for calculating the ET density ρ

E also contains several insignificant approximations, which are necessary for evaluating the ET volumes entrained by the SMP; however, calculus can be considered correct, and the mean ET density value from

Table 3 ρ

E≈2.0×10

‒4 kg/m

3 appears realistic.

7. Conclusions

In this article, we are based on our previous results starting with the discovery of Errors 1 and 2 in Michelson’s analysis of ME1881/87.

By correcting Errors 1 and 2 in Michelson’s analysis, it was possible to reintroduce Ether into Physics in 2016 in the form of our model HM16, which was subsequently completed and improved.

However, the presence of Ether in Physics has already led, in our previous work, to a series of important consequences, as in Sec. 1.

In 2021 [

10], we presented and described a new explanation of the intimate, physical/mechanical nature of the rest mass

m0 of submicroparticles.

At the same time, we also presented an explanation for the phenomenon of the increase in the rest mass m0 of the SMP once a speed v of movement through the ET of the SMP is reached. However, the SMP entrains a certain volume CE of the ET surrounding the SMP, whose kinetic energy EE constitutes even suplementary mass of ms.

This result was obtained by identifying the mass ms with the kinetic energy EE of ET, which accumulated in the volume CE/VE of Ether entrained around the SMP, moving with speed v through the ET.

In 2021 [

10], the calculation was carried out without explicitly working with the density ρ

E of the ET.

However, in this work, we have gone from the volume Ci of the ET to the related mass mi of the ET by introducing the density ρE of the ET and a formula for calculating the density ρE of the ET, resulted, containing the coefficient A1 as a function of the relative velocity β=v/c of the SMP.

The ρE calculation was initially performed for the simplest atom, Hydrogen, and subsequently also for the complex atom, Barium, which was subjected to a wide range of velocities β through the ET.

Therefore, we obtained a ET density ρE of approx. 2.0×10‒4 kg/m3

However, the above results for ρE are credible and also useful for future research on this topic, including practical applications in the field of space flight or physical experiments.

Acknowledgments

The first author gratefully acknowledges initial advice on the subject and encouragement from his late professor N. Barbulescu, a follower of Sommerfeld. He is also sincerely grateful to the late Prof. P. Mazilu from TUCB Bucharest for his rigorous lessons on rationality and is indebted to Gen. Prof. G. Barsan, Col. Prof. Al. Babos from LFA Sibiu, Prof. D. Stoicescu from ULBS Sibiu, Prof. D. Siposan from MTA Bucharest, and Ms. Veronica from Bucharest, for their support.

Funding’ and/or ‘Competing interests

No funds, grants, or other support was received. The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Authors contribution

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Ioan Has. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Ioan Has, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- Has, I. , Miclaus, S., Has, A. An initial model of Ether describing electromagnetic phenomena including gravity. Physics Essays 2010, 30, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Has, I. , Miclaus, S., Has, A. An analysis of the origin of the interaction force between electric charges including justification of the lnr term in the completed Coulomb’s law in HM16 Ether. Journal of Modern Physics 2018, 10, 1090–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Has, I. , Miclaus, S., Has, A. New properties of HM16 Ether, with submicroparticles as self‒functional cells interacting through percussion forces establishing nature of electrical charges, including gravitation. Journal of Modern Physics 2020, 11, 803–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Has, I. , Miclaus, S., Has, A. Presentation of new physics theory based on the HM16 model of Ether. Journal of Physics, Conference Series 2022, 2197, 012014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Has, I. Miclaus, S., Has, A. An actualized presentation of a new physics theory based on the HM16 model of Ether,” Buletin Stiintific Suplimentar, Official Catalog of Salon Cadet INOVA–LFA, Sibiu 6/2021, pp. 106–126. https://www.cadetinova.ro/index.php/ro/organizare/catalog/catalog-inova-21. (2022a).

- Has, I Has, I. , Miclaus, S., Has, A., “Michelson’s analysis of errors in his 1881/87 experiment of the two swimmers contest; Necessity of correcting college textbooks”. Journal of Physics, Conference Series 2022, 012012, 1–27. [CrossRef]

- Miclaus, S. , Has, A. Analysis of a possible correlation between electrical and gravitational forces. Physics Essays 2008, 21, 303–312. [Google Scholar]

- Has, I. , Miclaus, S. Has, A. A theoretical confirmation of the gravitation new origin having a dipolar electrical nature with Coulomb Law corrected. American Journal of Modern Physics 2015, 4, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Has, I. , Miclaus, S., Has, A. Analysis of electrical dipoles interaction forces as a function of the distance and of the form of electrical force. Journal of Applied Mathematics and Physics 2018, 6, 1886–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Has, I. , Miclaus, S. , Has, A. Explaining the nature of the mass m of submicroparticles and the phenomenon of mass variation with velocity v in Ether. European Journal of Applied Physics 2021, 3, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Has, I. , Miclaus, S., Has, A “Justification of rotation curves of galaxies without dark matter, based on the new gravitation theory, starting from the Ether presence after correcting Michelson’s analysis errors from 1881/87 experiments.. Preprint OSF. https://osf.io/preprints/osf/56c4j. [CrossRef]

- Laughlin, Robert B. A Different Universe: Reinventing Physics from the Bottom Down. NY, NY: Basic Books. (2005).

- Barbulescu, N The physical basis for Einstein’s relativity (in Romanian). Ed. St. & Enc.: Bucharest, p. 40-42. . (1979).

- Wikipedia. Le Sage theory of gravitation. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Le_Sage%27s_theory_of_gravitation (2024).

- Popescu, I. I. , “Ether and Etherons. A Possible Reappraisal of the Concept of Ether”, Romanian Academy Journal of Physics, 34: 451–468. Translation published as online edition (PDF), Contemporary Literature Press, 2015. ISBN 978-606-760-009-4 (1982).

- Mateescu, C. Hydraulics (in Romanian). Ed. Didact. & Pedagog, Bucharest, Romania, pp. 196‒198, 200‒202. (1961).

- Wikipedia “Atomic Radii. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Atomic_radii_of_the_elements_(data_page). (2024).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).