1. Introduction

Amorphous carbon is a material without long-range crystalline order. Short-range order exists, although with deviations of the inter-atomic distances and/or inter-bonding angles with respect to the graphite and diamond lattices. There are two crystalline forms of carbon, diamond and graphite, and a number of amorphous (non-crystalline) forms, such as charcoal, coke, carbon black and soot. Carbon nanotubes, graphenes and fullerenes are additional examples each having a specific structure on a nanometric scale. Soot is of atmospheric importance as it is emitted from fossil and non-fossil fuel combustion as a product of incomplete combustion. Most importantly, amorphous carbon occurs as an atmospheric aerosol that is strongly light-absorbing leading to a significant positive average climate forcing that makes it the most important absorbing and thus climate-warming aerosol despite its relatively short atmospheric lifetime in the troposphere of approximately 6 weeks [

1,

2,

3]. In addition, amorphous carbon has found widespread use in industry as black pigment and as filler, for instance in the rubber industry, improving wear resistance and longevity of automotive vehicle tires.

Particulate matter in the atmosphere produced by incomplete combustion of fossil fuels and biomass play a significant role as a tracer for anthropogenic activity and natural fires. Its major species is soot or combustion aerosol that is a variable mixture of organic carbon (OC) and elemental carbon (EC). Within the concern of global climate change, health and environmental effects, the atmospheric community recognizes the importance of establishing inventories for sources and sinks of light absorbing carbon, namely black carbon (BC) mainly containing EC and OC [

4,

5].

The detailed pathways of soot formation from combustion of hydrocarbon fuels are still a matter of debate to this day [

6]. Briefly, after ignition in a combustion engine most of the hydrogen content of the fuel and short-lived combustion intermediates is oxidized to H

2O vapor and oxygen-containing intermediates leaving behind a carbon-rich fuel. From then on carbon starts to burn in the combustion chamber at a much slower rate compared to hydrogen oxidation. The remainder is emitted at the end of the engine cycle as soot and gas phase products such as CO

2, CO, H

2O, NO

x and others into the atmosphere. Spatially and temporally resolved experiments on flame and chamber combustion yield mechanistic schemes of soot formation starting from the fuel hydrocarbon molecule to the fractal aggregates of combustion soot via Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon (PAH) formation of 200 to 900 Dalton and stack formation leading to primary soot particles [

6]. Elemental analysis of soot typically yields a carbon content close to 95 (atom) % with a few % H, O, less N and S depending on the fuel to oxygen equivalence ratio. Soot composition is highly variable ranging from planar rather small semivolatile PAH’s to large or puckered sheets owing to incorporation of five and seven-membered rings into a large network of conjugated rings having aromatic character [

7,

8]. Freshly emitted BC particles generated from laboratory flames, ship, diesel truck engines and open flames of biomass burning [

9,

10] have a microstructure of agglomerates of graphene sheets arranged in a turbostratic manner with a majority of carbon atoms being linked by sp

2 hybridized C-C bonds [

7,

8,

11]. Marhaba et al. documented the successful production of combustion soot simulating aviation soot using a cold nitrogen-quenched propane diffusion flame in a CAST (Combustion Aerosol Standard) device [

11]. The study was guided by the measurement strategy laid out in refs. [

7,

8] and relates to the introduction of emission controls on soot emitted in the lower stratosphere and upper troposphere by the civil aviation fleet [

12].

A new and noteworthy development is the seminal work of Lieske et al. [

13] in which he presents “portraits”, that is specific structural molecular data of an impressive array of combustion-generated PAH’s originating from a fuel-rich ethylene flame sampled into a chamber and deposited on a solid support consisting of a bilayer of NaCl on Cu (111) in order to obtain a molecular picture of “early soot formation”. Using AFM and STM imaging techniques led to the discovery of π free radicals that are stabilized by large-scale conjugation in planar and non-planar PAH structures and that provide structural information on “stable” free radicals on soot. These results provide a reliable structural base for the interpretation of EPR spectra of soot, wood smoke, cigarette smoke, tar, biomass burning smoke and other materials by Valavanidis and coworkers [

14]. Impressive spin densities in the range 10

15 to 10

17 spins/cm

3 have been observed by these workers that laid the ground for the structural elucidation of environmentally persistent free radicals (EPFR) and their role in atmospheric tropospheric chemistry.

Several studies have been performed to measure the interface properties of soot. In one example hexane soot was generated in a diffusion burner and the deposited soot was “soaked” in hexane to separate the OC from EC fraction [

15]. The unexpected reactivity of the EC fraction begs the question as to past efforts to understand the reactivity of combustion aerosol or combustion soot. Most of this work has been performed in solution either by potentiometric methods measuring the pH in aqueous solution or by other methods in the condensed phase. We emphasize the work of Donnet et al. [

16,

17] and Boehm et al. over the years [

18,

19,

20]. Regarding the latter group we have focused on confirming or infirming the presence of pyrones as weak bases in soot [

21].

We have been inspired by these workers and applied this approach to the study of the gas-solid or gas-condensed phase interface using multiphase or heterogeneous chemistry by eliminating the presence of the solvent [

22,

23]. This, on the one hand, simplifies the reaction system, but on the other hand eliminates possibilities by focusing exclusively on fast reactions as our chosen method precludes the study of slow reactions. The choice of the substrates was guided by the question of the molecular composition of the interface of a Standard Reference Material (SRM) in terms of surface functional groups. Chemical aging reactions under an oxidizing atmosphere owing to environmental exposure of a reduced substrate are of general interest in relation to slow oxidizing reactions that most often start at the molecular gas-condensed interface.

Popovicheva et al. have spent quite some effort at characterizing SRM materials in view of simplifying and/or modifying certification of these materials deemed unstable over time towards oxidation [

24,

25,

26]. The research question posed was to investigate the molecular composition of the interface of virgin material and explore the possibilities of interfacial reaction starting at the surface functional groups. At the end of the discussion we will quantitatively compare the coverages with two other cases centered on (inert) silica gel [

27,

28] and potentially reactive anthrarobin (1,2,10 - trihydroxyanthracene) that is a potent reducing compound and therefore unstable on atmospheric exposure. We thus clearly define two specific goals of this study, namely, (a) measure the molecular composition of the gas-solid interface in terms of the abundance of surface-functional groups for a potential Standard Reference soot Material (graphitized soot, GTS) in comparison to a typical commercial amorphous carbon sample (T900); (b) examine the interface of a tailor-made functionalized material based on GTS as a carrier in terms of the abundance of newly introduced surface functional groups.

The aim of the present study is directed towards molecular characterization of the interface of (a) two high-temperature processed amorphous (graphitized) carbon materials in view of their application as reference materials for atmospheric studies, and (b) of a custom-made material using a coating of an aromatic carboxylic acid on graphitized carbon as carrier or substrate material. A Knudsen Flow reactor (KFR) is used where a reactive probe gas reacts with functional groups of the substrate interface akin to a titration reaction in order to interrogate the chemical composition of the interface and recording its losses in the presence of a chosen substrate. The interface encompasses one or at most two molecular monolayers that are accessible by the probe gas on a short time scale given by the choice of the gas residence time of the molecular probes. This molecular penetration depth corresponds to the true interface in contrast to “surface sensitive” mid-IR spectroscopic methods whose penetration depth corresponds to approximately 2 μm at 1000 cm

-1 corresponding to 100 to 200 monolayers [

29]. We have successfully used this method for some time [

22,

23] and examples of past work using the KFR titration method include substrates of amorphous carbon and soot [

21,

30,

31,

32], volcanic ash and glass [

33], polymeric materials such as plastics [

34,

35] and asphalt samples from urban road pavements [

36].

3. Results

The summary

Table 1 exhibits the absolute coverage (molecule/cm

2) and the fractional monolayer coverage in the upper and lower lines of the data fields, respectively, for the six used probe gases, namely, TMA, HA, HCl, TFA, NO

2 and O

3 in columns 2 to 5. Except for column 5 (sample 4) the absolute monolayer coverage for the probe gases on the three substrates GTS6 (sample 1), GTS80 (sample 3) and T900 (sample 2) is that for the tightest packing of the adsorbed probe gas. For sample 4 the absolute number of acidic sites presented by adsorbed 1,2,4 BTCA is given by the coverage of the adsorbed acid after having saturated the substrate using a 4.88 % (w/w) solution of BTCA in acetone or ethanol under the assumption that all dissolved BTCA had been adsorbed to GTS80. It turns out that the acidic sites at the used BTCA concentration of the impregnating solution corresponds to a coverage of 1.77 10

14 molecule/cm

2 that is equivalent to 62 % of monolayer coverage of 2.87 10

14 molecule/cm

2. However, the coverage of 1.77 10

14 molecule/cm

2 represents the maximum we may expect for the used dose of BTCA. Except for sample 4 we chose to express the probe gas coverages in terms of fractional monolayers of adsorbed probe gas on the substrate rather than based on the space requirements of individual carbon and oxygen atoms of the amorphous carbon substrate in the absence of detailed structural details of the adsorbates adhering to the amorphous carbon substrates. As an example we take GTS6 resulting in a space requirement of 4.80 Å

2 per carbon atom using a mass density of 1.9 g/cm

3 (amorphous carbon) which leads to an absolute coverage of 2.1 10

15 carbon sites/cm

2. Identical results are obtained for GTS80 and T900 assuming the same above-listed mass density. Using the molecular weight of 1,2,4 BTCA of 210 g we arrive at a coverage of 2.87 10

14 molecule/cm

2, equivalent to 34.8 Å

2 per molecule. If we now “synthesize” the space requirement for BTCA (C

9O

6H

6) by ignoring the presence of H and equaling the space requirement for carbon and oxygen atoms we arrive at 15 x 4.8 = 72 Å

2 which is too large by a factor of two. This goes to show that one will have to point out where the numbers come from and how these are interrelated.

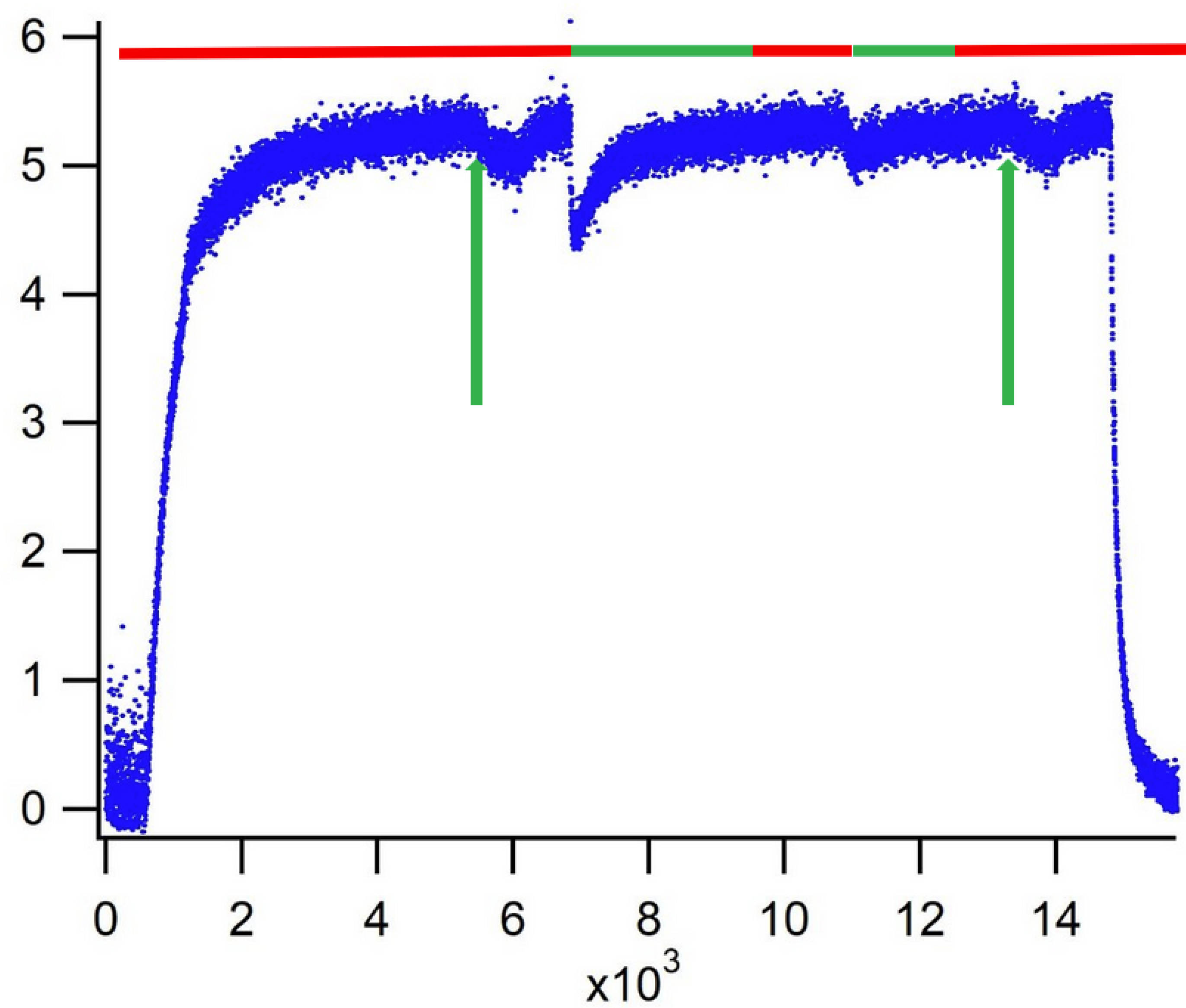

Figure 1 displays the time-dependent lock-in amplifier MS signal at m/e 33 amu of hydroxylamine (NH

2OH) interacting with GTS6 amorphous carbon (experiment s70#1 in

Table S2). The red and green horizontal bars displayed on top of the lock-in MS signal indicate the “closed” and “open” positions of the plunger, respectively, that isolates the sample compartment (SC) from the plenum of the KFR. The green horizontal bar between 7’000 (1’750 s) and 9’000 (2’250s) pts indicates the first uptake of HA on 109.5 mg GTS6 (ESI supplement) after which the SC is closed according to the red horizontal bar. The fact that the MS signal remains unchanged upon closing the SC indicates that the HA uptake has come to a halt owing to saturation. The initial absolute uptake determined from the calibrated ordinate of

Figure 1 using the measured flow rate of HA given in the legend of

Figure 1 corresponds to an absolute HA uptake of 1.4 10

13 molecules as indicated in

Table 1 and

Table S2.

The second opening of the SC at 11’000 pts. (2’750 s) reveals a small secondary uptake that we attribute to mass transport of HA adsorbed at the interface into the bulk phase of GTS6 and subsequent adsorption of additional probe gas to the liberated adsorption sites. Noteworthy are the two periods around 6’000 (1’500 s) and 13’000 pts. (3’250 s) marked by green vertical arrows during which the flow rate of HA was measured by interrupting the connection to the HA reservoir that stored solid HA at 0°C (ice bath). The absolute flow rate in molecule s-1 is routinely measured by observing the pressure decrease in the 50 cm3 inlet volume of the flow system. Owing to the small vapor pressure of HA of approximately 0.7 Torr at 0°C the decrease of the inlet pressure over the time required to measure the flow rate (5 to 8 measurements in a row) is apparently a sufficiently large perturbation to the inlet pressure to be observed on the MS signal level.

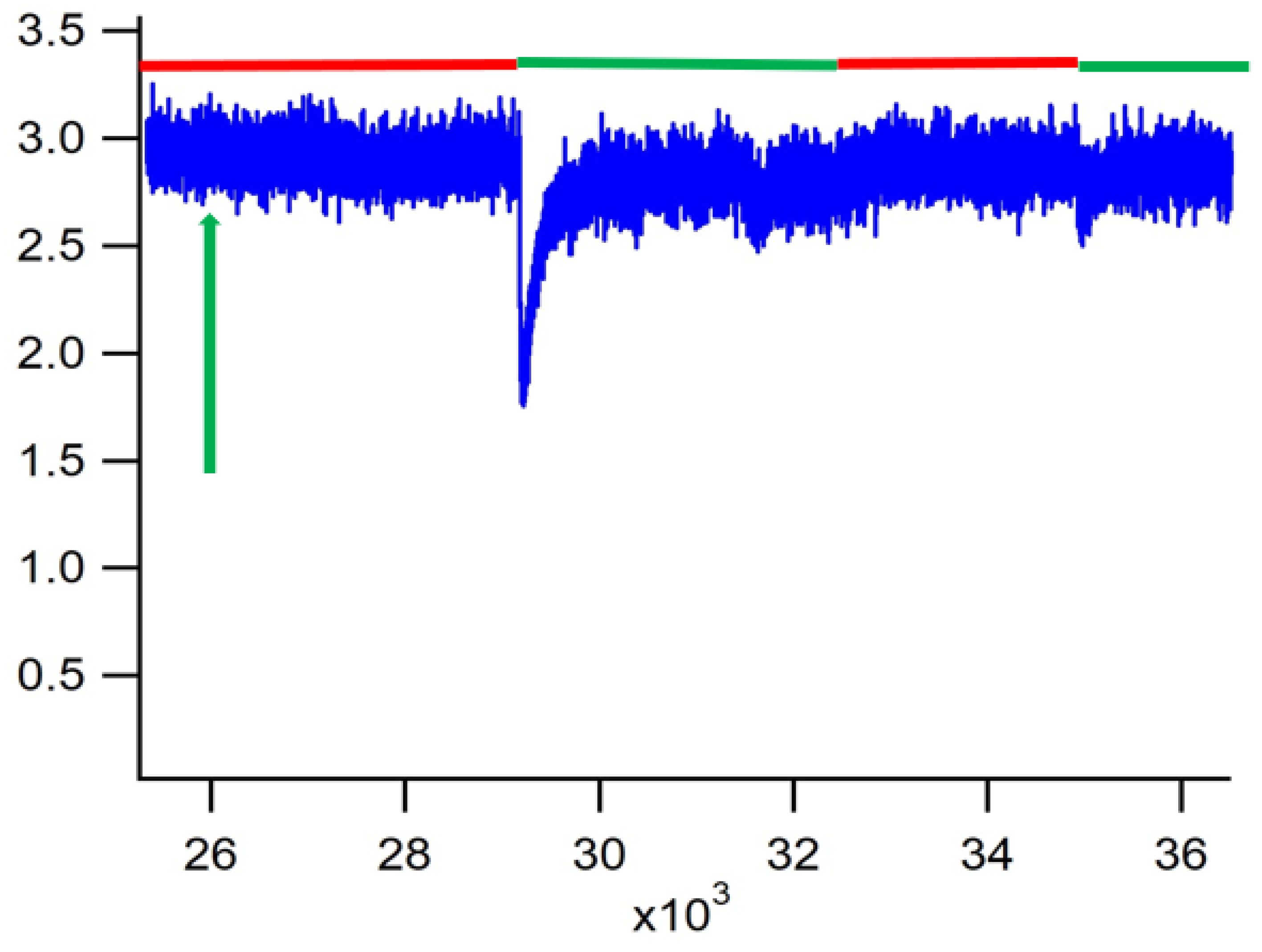

Figure 2 displays the lock-in MS signal of NO

2 at mass 46 amu interacting with a thermal soot T900 sample of 38.1 mg spread out over the 10.6 cm

2 sample cup housed in the SC (experiment S40#2 in

Table S2, ESI section). The initial uptake of NO

2 at 29’000 pts (7’250 s) saturates after 1000 pts. (250 s), however the steady-state MS signal level is smaller than the level with the SC closed (horizontal red bars on top). This indicates a small, albeit significant, steady-state uptake process of NO

2 that is also observed in a more prominent manner with O

3 as a probe gas (see below). The initial uptake of NO

2 is measured by taking the small steady-state MS signal level into account and amounts to 2.5 10

13 molecule (

Table 1 and S2). The second uptake at 35’000 pts (8’750 s) displayed under a green horizontal bar (SC open) is much smaller than the initial uptake but shows a small steady-state uptake kinetics as well.

A look at

Table S2 for probe gas NO

2 reveals three virgin samples with duplicate or triplicate experiments thus offering the opportunity at evaluating the reproducibility of the gas uptake. We will consider experiments s10#2, s40#2, s30#3, s40#3, s603#, S20#4 and s50#4 leading to averages of (2.1 ± 0.19) 10

13, (3.30 ± 1.13) 10

12 and (11.0 ± 2.0) 10

12 molecule, respectively, that leads to average variations of ± 19, ± 34 and ± 18% of the average value of molecular uptake. We therefore take a conservative view or upper limit for the measurement uncertainty of ± 40% on average for all considered cases.

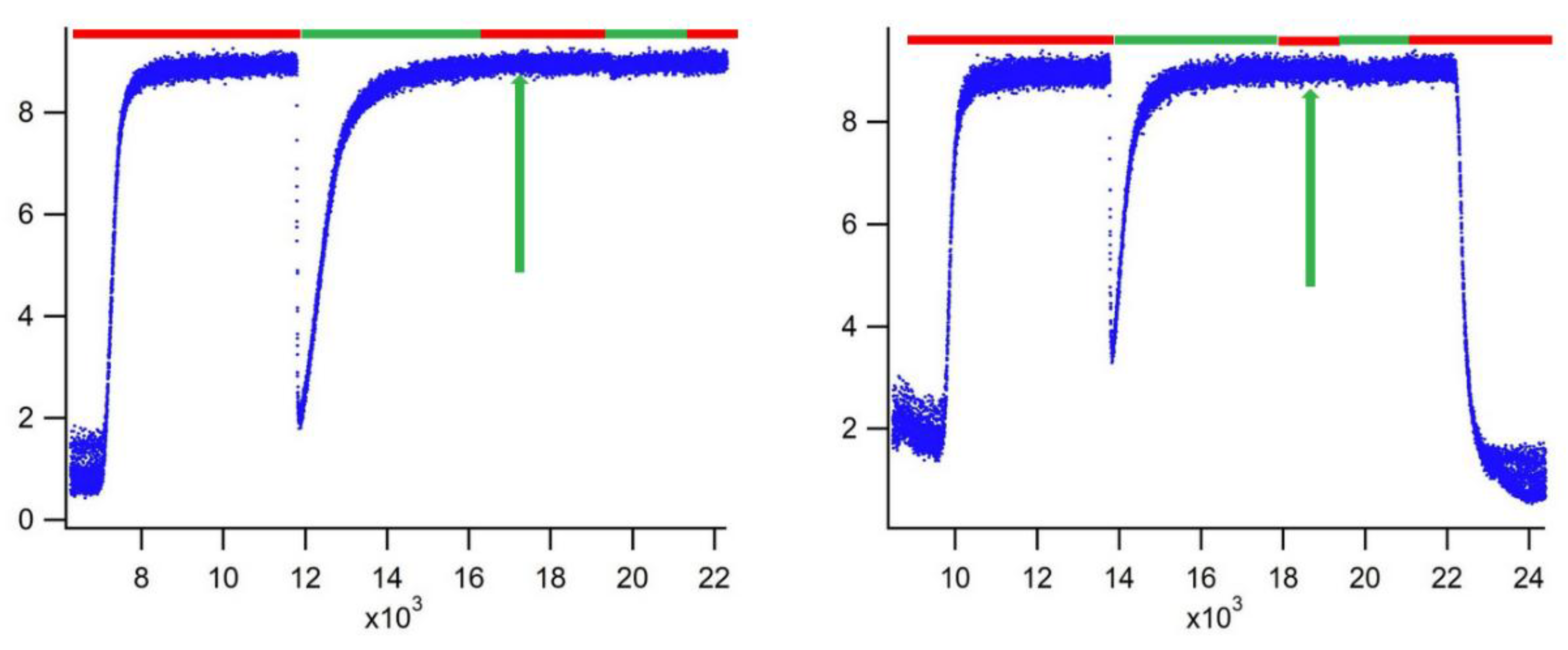

Figure 3 displays the lock-in MS signal of trimethylamine (TMA or N(CH

3)

3) at mass 58 amu on a thoroughly pumped and therefore recycled sample of GTS80 + 4.88% (wt) BTCA-doped amorphous carbon shown on the left panel (experiment s33#4 in

Table S2) together with the uptake after pumping the saturated sample overnight by repeating the TMA exposure on the right panel (experiment s34#4 in

Table S2). The sample had been previously exposed to HCl (s30#4), TFA (s31#4) and NO

2 (s32#4) but had undergone extensive pumping for a few days at 10

-5 Torr background pressure at ambient temperature (

Table S2). Both panels show complete saturation of TMA uptake after 1’000 s following the green horizontal bars, however, the extent of uptake has dropped from 5.9 10

13 to 2.7 10

13 molecule after overnight desorption and renewed TMA uptake the next day essentially at the same experimental conditions. This smaller second uptake reduced by 54% stems from the fact that desorption through pumping overnight only desorbs approximately half of the TMA (acidic) adsorption sites at ambient temperature. A look at

Table S2 reveals the fact that the uptake of TMA on a virgin sample is larger by 36 % when comparing 9.2 10

13 (average of s10#4 and s51#4,

Table S2) with 5.9 10

13 molecule (s33#4,

Table S2) which means that even long-term rejuvenation by pumping at ambient temperature does not free up all possible acidic adsorption sites on the BTCA-covered sample at ambient temperature. This is to be expected owing to the heterogeneous nature of the BTCA-covered interface of GTS80 (sample #4) where some TMA molecules are more strongly bound than others and therefore desorbing at a much slower rate compared to weaker bound ones.

Table 2 displays the initial probe gas uptake probabilities or uptake coefficients measured in the 1mm diameter orifice KFR for all probe gases except HCl. Owing to partial saturation at high pressures the uptake kinetics represents a lower limit as the uptake rate coefficient usually goes up with increasing orifice diameter or decreasing gas residence times, that is upon lowering the partial pressures. The values are in the 10

-5 to 10

-3 s

-1 range, thus larger than the steady-state first-order rate constants for NO

2 and O

3 displayed in

Table S3.

Table 2 primarily shows values for virgin samples as the values decrease with each sequential exposure owing to partial coverage from the previous experiments. A typical example is shown in

Figure S1 for experiment s70#3.

The large dynamic range of kinetic measurements such as uptake probabilities of the present KFR notwithstanding we point out that the entries for γ0 of NO2 (s50#1) and NH2OH (s50#3) are to be regarded as upper limits. A practical limit of detection corresponds to an uptake probability of 10-5 for light gases based on the geometric surface area of the sample cup (10.6 cm2) or a rate coefficient for initial uptake of k0 = 10-4 s-1. In this case the competition between reaction of NO2 and escape out of the KFR (ke = 0.038 s-1 at 300 K) is 1/380 corresponding to 0.26 % reaction beyond which there are not sufficient molecules reacting to be detected. This limit depends on the signal to noise (S/N) ratio of the MS instrument as far as molecular beam intensity is concerned as well as on the S/N improvement ratio of the lock-in amplifier.

4. Discussion

A cursory look at

Table 1 reveals that the uptake of the six used probe gases on samples #1 (GTS6), #2 (T900) and #3 (GTS80) is rather small in general for amorphous carbon samples compared to previous experiments that used the identical experimental method [

22,

23,

30,

31,

38]. Graphitization or pyrolysis under anaerobic conditions (under N

2) of amorphous carbon is tantamount to removing surface functional groups containing N, O, S and other atoms in order to obtain a close approximation to the properties of pure elemental carbon EC [

15]. A closer look comparing GTS6 and GTS80 in

Table 1 (columns 2 vs. 4) reveals a larger abundance of interfacial functionalities for GTS6 compared to GTS80, especially for the probe gases HA (NH

2OH), NO

2 and O

3. These probe gases reveal the interfacial abundance of surface OH-groups (HA) on the one hand and reduced or oxidizable functionalities on the other hand through reaction of NO

2 and O

3. GTS6 is thus a more richly decorated amorphous carbon compared to GTS80 as far as surface composition per cm

2 is concerned. Quantitatively speaking, GTS6 has a higher abundance of surface –OH groups by a factor of 15, and a larger abundance of reducing interfacial groups reacting with NO

2 and O

3 by factors of 5 and 11, respectively when comparing to GTS80.

Comparing a “normal”, that is unprocessed amorphous carbon such as T900 (third column in

Table 1) to GTS6 as far as reactivities of HA, NO

2 and O

3 are concerned we see a similar surface OH-group abundance (within a factor of two) and an amount larger by a factor of two and five for NO

2 and O

3. This underlines a similarity between the surface composition of GTS6 graphitized amorphous carbon and unprocessed and commercially available thermal carbon T900. However, when performing the same comparison of T900 reactivity vs. GTS80 the paucity of surface OH-groups and reducing capacity becomes apparent for the latter. Among the noteworthy facts is the high reactivity of T900 with pure O

3 that is higher by a factor of 50 compared to GTS80 according to data displayed in

Table 1. However, this situation is expected on the basis of results on other types of amorphous carbons as far as ozone reactivities are concerned [

22,

23].

When we compare the reactivity of the strong oxidizer O

3 with the weak oxidizer NO

2 for T900 and compare it to GTS80 we obtain a factor of 13 and 2.3. This disparity emphasizes the fact that there are only few strong reducing entities reacting with NO

2 while O

3 reacts with all, both weak and strong, reducing functionalities that are present in higher number. This distribution of strong and weak reducing capacities in amorphous carbons is characteristic for specific samples of amorphous carbons as has been reported before [

22,

23,

30,

31,

38] and may indicate the molecular entity having specific reducing properties, for instance embodied in conjugated vs. isolated hydroquinone/ether combinations (pyrones) that lead to specific ratios of yields or uptakes of O

3 vs. NO

2.. Another characteristic ratio is the reactivity of the strong acid TFA probing the sum of amounts of weak and strong bases whereas the weak acid HCl only probes strong bases. This ratio detects the abundance of weak bases such as pyrones that are weak bases consisting only of C, H, and O atoms without the presence of nitrogen heteroatoms. Inspection of

Table 1 reveals the complete absence of HCl uptakes in all examined cases which points towards the existence of weak bases exclusively in all cases treated here. In turn, we are not saying that all weak bases are conjugated pyrones, however, we claim that the weak basicity may be interpreted by taking a conjugated pyrone as an example.

Lastly, we compare columns 4 and 5, namely pure GTS80 as the carrier or substrate of 1,2,4 BTCA at a specific doping level leading to 1.77 1014 molecule/cm2 as the amount of a molecular monolayer using the estimated mass-density of BTCA as an example of a tailored soot material. As expected we observe a large coverage of 52% of a monolayer when examined with the strong base TMA. In addition, the coverage of surface OH-groups amounts to 16.4 % of a monolayer which is the highest coverage of HA within the tested samples. A significant abundance of reducing sites seem to be present in both cases at the close to monolayer coverage by BTCA when you compare GTS80 with GTS80 + 4.88% BTCA. Upon comparison between both GTS80 samples probed by both NO2 and O3 the abundance (absolute number) of sites reacting with NO2 is a factor of 4.6 higher for GTS80 + BTCA compared to bare GTS80 whereas it is a factor of only 2.3 larger for O3 uptake. We note in passing that the strongly reducing functional groups at the interface probed by NO2 increase more upon coating than the sum of all reducing groups probed by O3. This increase for both NO2 and O3 uptake upon coating GTS80 reveals a propensity for oxidation of a species absent on bare GTS80. This result is unexpected and leaves room for speculation as to the nature of the reducing properties of BTCA-coated GTS80, especially in view of the gas phase thermodynamic stability of BTCA. It is possible that this may have to do with an interfacial reaction involving 1,2,4 BTCA.

A last remark concerns the strength of the basic interfacial sites of BTCA-coated GTS80 in relation to bare GTS80 considering the uptake of HCl to the extent of 4.4 10

-3 compared to the uptake of TFA of 3.28 10

-2 monolayers. These numbers may be interpreted that the sum of all basic sites amounts to 3.28 10

-2 with 4.4 10

-3 monolayers contributing to strong bases because HCl as a weak acid titrates preferentially strong bases owing to its weaker acidity in the gas phase compared to TFA. Therefore, weak bases make up a majority of 2.84 10

-2 of a monolayer with strong bases contributing 4.4 10

-3 resulting in a ratio of 6.5 weak vs. strong bases or 87% weak vs 13% strong bases. We identify weak bases with (conjugated) pyrones [

21] in the absence of basic nitrogen. This case is the only one where reliable results of HCl titration could be obtained compared to the three remaining samples. The comparison of NH

2OH uptake probing surface OH functional groups between bare GTS80 and the BTCA-coated substrate begs the question of whether or not NH

2OH acts like a weak base in an acid-base reaction or in a complex formation leading to a hydrogen-bonded adduct. We measure a factor of 7 and 32 increase in NH

2OH uptake going from sample 3 (bare GTS80) to sample 4 (BTCA-doped) taking the geometric probe gas monolayer coverage based on the liquid density of HA and the BTCA coverage, respectively. In both cases one measures a significant coverage of HA on the BTCA-doped interface where the probe gas interacts with the acidic carboxylic –OH group. We estimate that approximately 16 % (equal to 2.9 10

13/1.77 10

14 = 16.4% of a monolayer) of the acidic carboxylic OH groups are strong enough to interact with the weak base HA in this case.

In conclusion we may state that the most “inert”, that is the amorphous carbon substrate with the lowest number of functional groups at the interface, is bare GTS80 followed by GTS6. The latter is similar to a “normal” unprocessed and commercially available amorphous carbon when compared to thermal carbon T900 as far as the abundance of surface OH-groups and the interfacial reactivity with NO2 and O3 are concerned. However, another message emerges resulting from these titration experiments: each amorphous carbon has a pattern of probe gas reactivities that is specific owing to its generation and follow-up fate. In view of the similar processing conditions regarding the treatment of GTS6 and GTS80 the significantly different abundance of probe gas uptake is certainly a surprise. However, it must also be stated that in view of the paucity of surface functional groups except for BTCA-doped substrates the experimental results have relatively large uncertainties in this case, also in view of the modest amounts of material that was available for the present study.

A look at

Table S2 enables an overview over the whole database obtained in the present study. In order to make good use of the available samples we subjected the samples to multiple probe gas exposures in order to see whether or not different probe gases obtained identical uptakes of reactive gases from previous exposures, either using the same probe gas or a different one. We checked for “memory effects” after sample “regeneration” by pumping/refreshing a spent sample overnight (roughly 10 to 12 hours) at a vacuum of 10

-5 mbar within the KFR at the fastest pumping rate available by switching to the 14 mm diameter escape orifice of the KFR (see

Table S1 for reactor hardware parameters). The most important question was whether or not it was possible to obtain reliable answers on sequential uptakes of multiple probe gases using the same sample after extensive regenerative pumping all the while considering the fairly weak uptake in most cases. We will not engage in discussing all data to be found in

Table S2, but concentrate on four cases as examples as follows:

- -

Considering the results of thermal amorphous carbon T900 and the HA probe we compare the entries for experiments s60#2 with s51#2 and come to the conclusion that previous ozone exposure increases the abundance of surface OH-groups at the interface by approximately 50%. We conclude that previous exposure to O3 irreversibly modifies the interface of T900.

- -

For the case of BTCA-covered GTS80 probed by TMA we generally notice a “memory effect“ owing to exposure to NO2, TFA and HCl in that the uptake decreases upon exposure to these gases after probing with TMA. We take the average of runs s10#4 and s51#4 as the baseline for comparison, namely, an uptake of 9.2 1013 molecule.

- -

Even for bare GTS80 we notice a “memory effect” when comparing run s20#3 with s21#3 owing to previous exposure to TFA.

- -

Previous HA exposure of GTS6 and thermal carbon T900 samples enables marginal HCl uptake because adsorbed HA may act as a base as HA is a multifunctional molecule as seen in runs s71#1 and s61#2. The level of HCl uptake is larger than the “background level” of HCl uptake observed for bare GTS80, run s31#3 as seen in

Table S2.

Except for the first point above on sample #2 (thermal carbon T900) where possible reactive modification of the interface may be the reason for the memory effect of the previous exposure to a reactive gas such as O

3, the three other cases may be caused by the fact that regeneration/rejuvenation through long lasting pumping may not restore the interface to its pre-exposure state. This is the reason that the data in

Table 1 mainly present first-time uptake experiments using virgin samples with four exceptions deemed to be acceptable. It turns out that certain salts of TFA, HCl and/or TMA with interfacial basicity or acidity may not correspond to thermodynamically stable species and slowly decompose under high-vacuum conditions. Ozone deserves special attention as a probe gas for amorphous carbon as it has been used on numerous occasions with amorphous carbon owing to its suspected heterogeneous (interfacial) reactivity with several types of amorphous carbon [

40,

41]. This work has shown the saturation of reactive O

3 adsorption at typical 300 ppb and the significant increase of O

3 uptake kinetics upon UV/Vis irradiation in a coated wall flow tube experiment using propane combustion in a CAST soot generator. Noteworthy is the effect of the increase in relative humidity that leads to even faster sustained O

3 uptake kinetics on propane soot rather than the expected and usually observed decrease. Thus this work documents the reproducible regeneration/reactivation of the uptake capability of propane soot upon UV/Vis illumination after exhaustive saturation of O

3 uptake in the dark.

Table 2 presents data on the uptake kinetics of certain probe gases that resulted in significant loss signals at the prevailing noise levels at steady-state conditions. Uptake kinetics is expressed as an uptake probability per gas-interface collision leading to loss of species within the gas residence time for assumed first-order loss based on the

geometric as opposed to the total internal and external surface as given by the BET surface. As alluded to above, all uptake experiments have been performed in the 1 mm diameter orifice KFR in order to come as close as possible to saturation conditions. Under these conditions some experiments are already partially saturated which means that the initial uptake coefficient or probability may be larger at shorter residence time and thus lower probe gas concentrations. This has recently been shown by Zogka et al. for heterogeneous kinetic studies of glyoxal on different dust samples [

42]. Results displayed in

Table 2 are therefore to be considered as lower limiting values. On the other hand, certain samples of low mass may not completely cover the entire area of the 10.6 cm

2 sample cup such that this effect may partially offset the fact that the uptake is partially saturated. These two effects may counteract each other and the values displayed in

Table 2 may therefore give an approximate idea of the magnitude of the initial uptake kinetics

Certain probe gases such as NO

2 and O

3 lead to chemical reaction or oxidation of the interface with the substrate which may give rise to a chemical loss at steady-state. In

Figure 2 such a reaction has been mentioned in the interaction of NO

2 with thermal carbon T900. Such data are of importance in the environment as they have effects in the long term because these slow reactions go on long after the surface has been saturated.

Table S3 displays such steady-state loss reactions for O

3 on three substrates that are based on the BET surface in contrast to the steady-state uptake kinetics based on the geometric surface of

Table 2. However, these oxidation reactions occur on specific sites of the bulk phase that are slowly consumed as displayed in

Table S3 with a slow decrease of the rate constant with each exposure period of 10-20 minutes. These slow albeit important processes are difficult to measure quantitatively but may have a significant impact on atmospheric chemistry. Oxidation reactions by NO

2 are in general slower than with O

3 but may lead to the same or similar oxidation products such as surface OH-groups at the interface, partially oxygenated intermediates or even gas phase CO and CO

2 observed after spontaneous ambient or higher temperature desorption. Although the gas phase products are known and expected, one does not know anything about their precursors before transformed into gas phase products. As a case in point

Figure S1 presents the time-dependent uptake of pure O

3 on bare GTS80 (s70#3). It shows three uptake sequences of ozone monitored at m/e 48 amu (O

3+) with only the first showing a distinct “irreversible” uptake similar to the behavior shown in

Table 1 and S2 followed by a plateau level indicating a steady-state loss or uptake. The following two openings of the SC indicate a quasi steady-state uptake that only slowly saturates at long exposure times owing to the finite number of suitable reduced adsorption sites. Both O

3 and NO

2 indeed show this steady state loss that may be significant for atmospheric chemistry. As a quality control measure we have indicated the ratio of the lock-in MS signals at masses 32/48 amu at three instants during the experiment (two measurements are shown in

Figure S1) and assured its constant value of approximately 0.5 throughout the uptake experiment.

Finally, let us compare the limiting large values for the TMA titration yields on BTCA-doped GTS80 (sample no. 4) of approximately 50% of a monolayer (

Table 1) with another chemical system in which NH

2OH (HA) heterogeneously interacts with TiO

2 powder using the identical experimental method.

Table S4 shows high values of large HA saturation values when taking note of the entries for TiO

2 except entries two and four that pertain to special situations (see footnotes b and c in

Table S4). It is known from the literature [

43] that TiO

2 (rutile, anatase and mixtures of it) has almost exclusively OH surface functional groups at high coverage on its interface which explains the high value of 50.7 % of a monolayer determined as an average from entries 1, 3, 5 and 6. Please take note that two TiO

2 samples having a BET surface differing by a factor of 5.5 gave very consistent coverages of HA, namely comparing entries 1 and 3 vs. 5 and 6. Unlike the TMA titration of sample no. 4 displayed in

Table S4 the saturation coverage for HA on TiO

2 was derived from a close packing model of HA using the mass density of HA discussed in

Section 2.2 (see also footnote b in

Table 1) because we do not have reliable information on the surface OH-density on TiO

2. Therefore, one cannot a priori compare the numerical values for saturation coverage. We nevertheless take this excellent agreement as a sign for the accuracy and consistency of the present titration method in determining the saturation coverage of both TMA via an acid-base reaction and HA through a hydrogen-bonded stable 5-membered ring arrangement presented in ref. [

34].