1. Introduction

Over the past two decades, cardiac CT has emerged as a pivotal modality in the realm of coronary and structural heart interventions, dramatically shifting from a non-invasive imaging tool to a one utilized in both diagnostics and decision making [

1]. With the capacity to provide high-resolution, three-dimensional images of the heart and surrounding vasculature, CT plays a vital role in the assessment of coronary vessel disease in Chronic Coronary Syndrome (CCS), Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS), and in the evaluation of structural heart conditions, aiding diagnostics and subsequent pre-procedural planning for respective disorders [

2].

In coronary interventions, CT offers an alternative diagnostic tool and an adjunct to invasive angiography and enables visualization of the vasculature in fine detail [

3]. The most recent European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines have reflected this clear benefit of CT and now recommend this as a first line test in assessment of CCS, and its role in ACS is constantly developing [

4].

This review will describe the current role of CT in both anatomical and functional assessment of coronary artery disease and explore the developing role of FFRCT and AI technology in the assessment and management of CCS.

The role within structural heart disease is, of course, well established, with CT playing a vital role in the pre-procedural planning of valvular interventions such as TAVI [

5].

2. Cardiac CT Imaging in Coronary Artery Disease (CAD)

Coronary artery disease is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in developed nations throughout the globe [

6]. The healthcare burden that CAD places on society is immense, and as such much work has gone into the development of accurate methods of assessment and management of CAD. CTCA is one of those methods, predominantly utilized in the detection or exclusion of obstructive CAD in patients presenting with CCS, and more recently in ACS [

7].

During CTCA intravenous contrast is injected to visualize the vessel lumen and allows formulation of contrast enhanced imaging of the entire heart and vessels [

8]. The technique facilitates identification of coronary lesions, plaque characteristics and evaluation of myocardial perfusion thereby guiding intervention [

9].

3. Use of Computed Tomography in CCS

3.1. Assessment of CCS and Coronary Calcium Scoring

Evaluation of CCS begins with comprehensive clinical evaluation. It is important to establish the symptoms and signs of CCS, differentiating between non-cardiac causes and ruling out ACS. The initial clinical assessment requires performing a 12-lead resting electrocardiogram (ECG), haematological and biochemical blood tests including a troponin, and when required radiological imaging in the form of a chest x-ray. In patients presenting with chest pain, with a non-diagnostic ECG further cardiac examination with non-invasive testing (exercise ECG, stress echocardiography, stress cardiac MRI or CTCA). The purpose of these investigations is to establish cardiac function and clinical probability of CAD, these investigations will guide referral for invasive coronary angiogram (ICA).

With the exclusion of ACS, diagnosis of CCS can be made based on several parameters which include the impact of age, biological sex, obesity, smoking and other comorbidities allowing calculation of pre-test probability of obstructive CAD [

10].

Historically, exercise ECG testing has been utilized as a first line test to assess likelihood of obstructive CAD [

4]. The use of CTCA has a higher diagnostic performance and can give more accurate, conclusive information in CAD and as such has emerged over recent years as a first line diagnostic test where there is suspicion of CCS [

11]. Not only does CTCA provide an anatomical diagnostic capability but also a functional insight, enabling targeted preventative therapy and intervention. CTCA is also associated with reduced anginal side effects when assessed at follow up when compared to exercise ECG testing as an index investigation for stable chest pain [

12]. Clinical trials such as the Scottish COmputed Tomography of the HEART (SCOT-Heart), have demonstrated a small yet significant reduction in the combined endpoint of cardiovascular death or non-fatal MI (from 3.9% to 2.3% in 5-year follow-up) in patients where CTCA was performed in addition to routine testing (exercise ECG) [

13].

In contrast to exercise testing, CTCA allows visualization and quantification of the size of atherosclerotic plaques and calculation of a Coronary Artery Calcium Score (CACS), using ECG-gated CT techniques [

14]. CACS is an assessment of total calcified plaque based on imaging. An absence of CACS (CACS = 0) has been shown in trials to correlate with a very high negative predictive value for obstructive CAD [

15]. In patients with negative CAC scores (CACS = 0), further testing can be safely deferred without increased risk of MACE during follow up [

16]. Further, calculation of the CACS in asymptomatic patients has been shown across trials to be of prognostic value, alongside emerging data that CACS can predict major adverse cardiac outcomes in stable chest pain [

17].

Figure 1 shows heavily calcified coronary arteries on a non-gated CT scan.

3.2. Alongside Invasive Coronary Angiogram or as an Adjunct to?

The role of CTCA extends beyond calculation of coronary calcium scores alone. In fact, CACS, whilst a useful assessment of plaque and risk stratification tool, has been shown to underestimate non-calcified plaque and thus not be of great prognostic value independently [

18]. Further, presence of plaque alone does not dictate adverse outcome [

19].

CTCA can detect plaque but also allows direct visualization of the coronary artery lumen and wall, detailed assessment of plaque burden, vessel morphology, and the identification of significant stenosis [

20]. In patients with suspected but unconfirmed CAD, the diagnostic accuracy of CTCA has been demonstrated across multiple prospective trials with a sensitivity of 85% to 99% and specificity of 64% to 92% [

21].

In regards to luminal assessment, CTCA aids in providing optimal images for angiographic projection in the catheter lab thereby minimizing vessel foreshortening, which is of particular benefit in evaluation of lesions which bifurcate [

22]. Analysis of the coronary arteries using CT has been shown to have a high concordance with true luminal dimensions when compared to invasive angiography. This can help to define both lesion severity during assessment and selection of stent size in percutaneous revascularisation planning [

23]. Further, technological developments in recent years have advanced diagnostic performance of CTCA in detecting significant coronary artery stenosis (>50% luminal narrowing) even in patients with high heart rate and atrial fibrillation [

24].

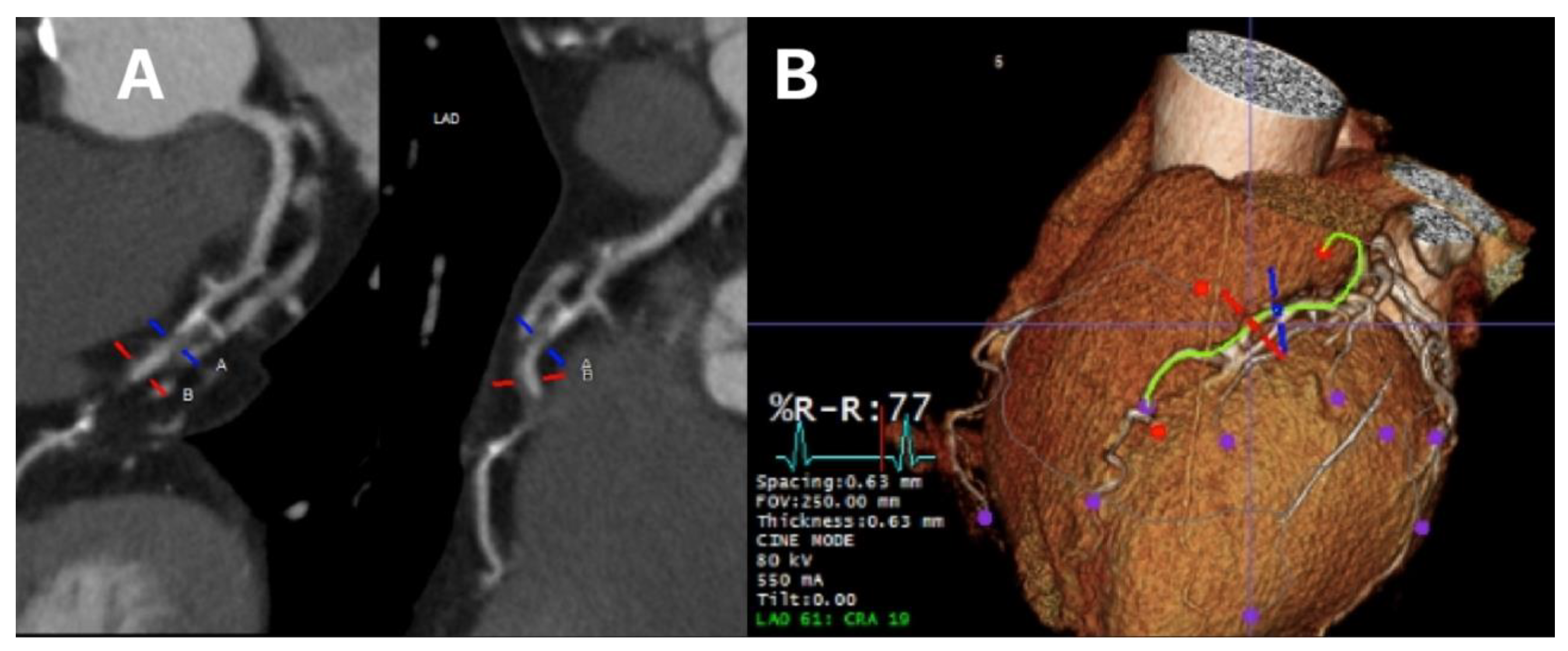

Figure 2 shows luminal assessment of a gated-CTCA demonstrating a severe stenosis in the proximal LAD on the vessel image (panel A) and the 3D reconstruction (panel B).

Figure 2.

Luminal assessment from gated CTCA. Panel A shows the lumen of the LAD, with severe mid-proximal stenosis. Panel B shows the 3D reconstruction of the same artery.

Figure 2.

Luminal assessment from gated CTCA. Panel A shows the lumen of the LAD, with severe mid-proximal stenosis. Panel B shows the 3D reconstruction of the same artery.

Plaque assessment is also a key feature of CTCA. CT can identify high risk plaque features and characterization of this through Hounsfield Units (HU) and appearance. High HU correlates as significantly calcified plaques, white structures on CT imaging [

23]. Plaque calcification is useful to determine pre angiography, as an elevated calcium burden is associated with lower stent expansion and increased risk of adverse events following PCI [

25]. The ability to assess the burden of calcification pre-procedurally can subsequently improve PCI planning as techniques can be modified to suit vessel appearance such as rotational or orbital atherectomy, excimer laser, or intravascular lithotripsy, and thus improve outcome through enhanced stent expansion [

26].

Overall, large trials such as the International Study of Comparative Health Effectiveness with Medical and Invasive Approaches (ISCHEMIA) trial have demonstrated high concordance of ICA for the identification of at least single- vessel CAD and absence of LM disease in 92.2% of cases [

27]. This confirms that CTCA can accurately diagnose coronary artery stenosis.

Further, data from the DISCHARGE (Diagnostic Imaging Strategies for Patients with Stable Chest Pain and Intermediate Risk of Coronary Artery Disease) trial supports the use of cardiac CT in the evaluation of symptomatic patients suspected of having CAD, with subgroup analysis showing this reduces MACE compared with ICA alone, even in those with elevated BMI, where previous concern around CT use has arisen [

28]. Obesity has previously been regarded as a potential to be a limiting factor to CTCA due to its association with noise artefacts causing attenuation in X-ray signal and hence reduction in image quality [

29].

As a diagnostic tool, CTCA is performed in a non-invasive manner, offering a safe alternative to ICA with proven diagnostic performance in detecting obstructive or stenotic disease. This could be used as an alternative therefore to ICA diagnostically, potentially reducing the need for repeat procedures and contrast exposure [

21]. In those cases where percutaneous intervention is required, CT may allow more accurate planning and therefore reduces procedure time, radiation and contrast exposure , morbidity and mortality [30, 31]. This is particularly important in previous CABG cases where CTCA can provide valuable information to guide ICA by delineating graft origin landmarks thereby minimizing complications and improve patients’ satisfaction [

32].

3.3. The Role of CTCA in Functional Assessment of Coronary Vasculature

Extending beyond anatomical assessment of CAD, CTCA has an emerging role in identifying flow-limiting disease using FFR

CT. Through the use of Heart-Flow Inc technology measurements of lumen boundaries, hyperaemic coronary flow, pressure and myocardial mass are possible, allowing non-invasive calculation of fractional flow reserve (FFR) [

33]. FFR is essentially the calculation of the ratio of maximal blood flow through narrowed vessels to the blood flow in a hypothetically normal artery, using CT images, therefore enabling non-invasive functional assessment [

34].

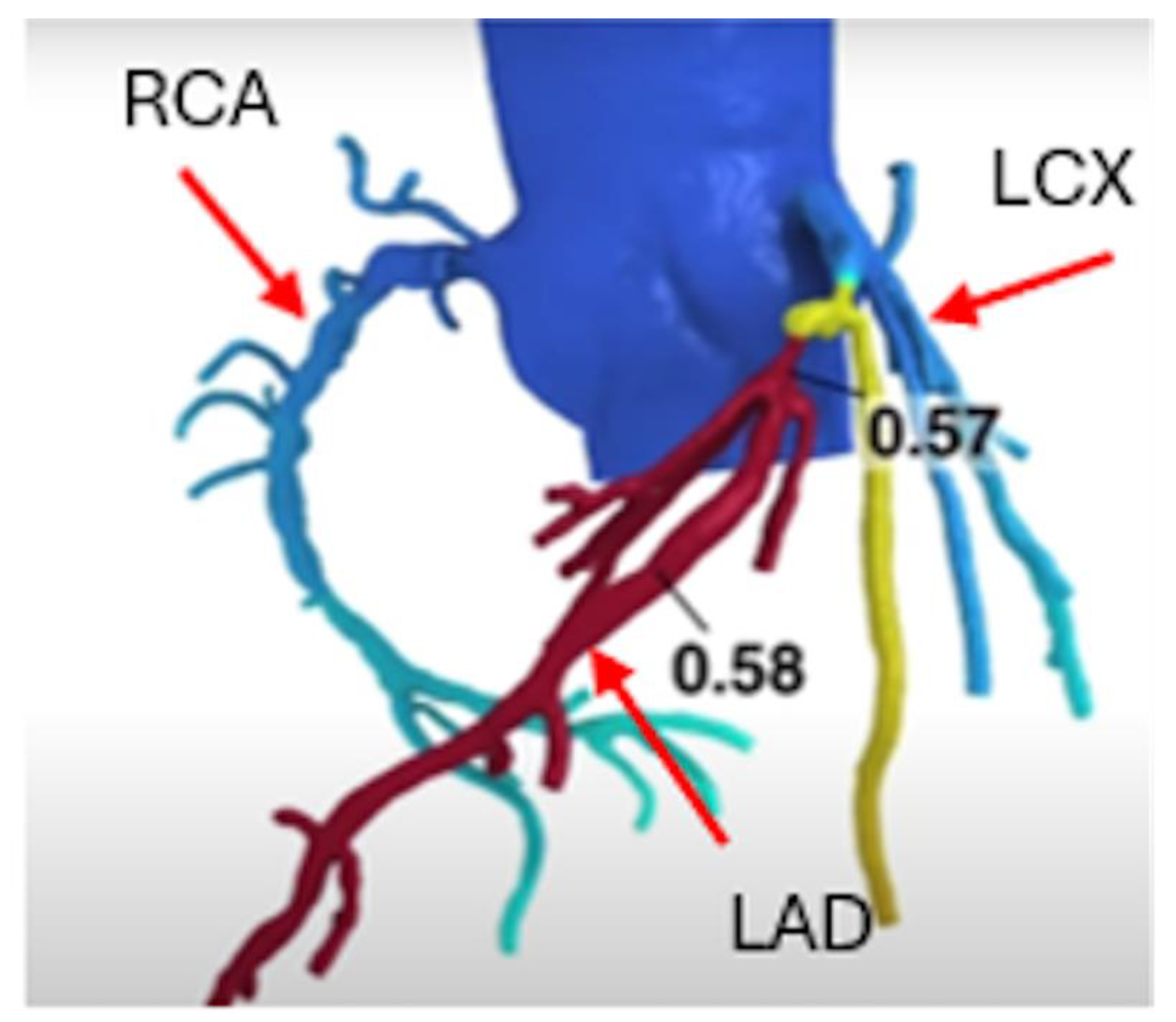

Figure 3.

FFRCT showed significant LAD stenosis with value less than 0.8 (color index as Red).

Figure 3.

FFRCT showed significant LAD stenosis with value less than 0.8 (color index as Red).

Meta-analyses have demonstrated high specificity of FFR

CT alone (n=2432) and when combined with CTCA (n = 362) in detecting haemodynamically significant stenosis with values of 78 and 80% respectively [

35].

The diagnostic accuracy of functional CT imaging through calculation of FFR

CT has been shown in patients with stable angina to be comparable with standard care in regard to clinical outcome and cost at 9 month follow up (FORECAST Trial) [

36]. Through analysis of FFR, impact of stenotic lesions on cardiac function can be calculated thereby reducing the number of ICAs without obstructive disease or in patients requiring intervention within 90 days, however data from the TARGET trial has shown this does not overall reduce revascularisation or major adverse cardiac events [

37].

Functional assessment using FFR

CT complements CTCA imaging and has been shown to have good agreement with invasive flow reserve calculations [

38], and has clinical utility in reduction of ICA, particularly within patients with moderate vessel disease. The FACC (Diagnostic and Clinical Value of FFR

CT in Stable Chest Pain Patients With Extensive Coronary Calcification) study has shown that in severe coronary stenosis FFR

CT is limited in its use ahead of ICA due to technical complications. Of those patients studied, those with the most severe stenosis did not go on to FFR

CT at the discretion of the cardiologist due to judgment of technical issues such as vessel tortuosity and heavy calcification [

39].

Nevertheless, the overall adequate diagnostic performance and potential to reduce downstream invasive testing have been demonstrated [

40] and as such, with further standardization FFR

CT could become a more widely utilized diagnostic tool.

4. CTCA in Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection (SCAD), Intramyocardial Bridging and Coronary Anomalies

ICA is considered the gold standard for diagnosing SCAD. However, CTCA has been proven to play a crucial role in both diagnosing and monitoring the management of SCAD. With limitations, CTCA has been helpful in assessing the healing of dissections and has even diagnosed SCAD cases initially missed on ICA [

41]. Less commonly, CTCA has the potential to pick up congenital coronary abnormalities such as myocardial bridging (MB), which commonly affect the mid-LAD taking an intramyocardial path. CTCA is well capable of identifying the length and significance of MB to enable early detection and management [

42]. In a similar manner, it serves as the initial test of choice for detecting rare coronary artery anomalies (CAAs) (incidental findings in 1- 5.8% of the general population)[

43] which can precipitate significant hemodynamic compromise and even sudden cardiac death, in rare cases, if not identified and treated. Indeed, CTCA identifies CAAs with accuracy and aids classification by describing their course and hemodynamic significance, for instance, anomalous left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery (ALCAPA) syndrome, duplications of the LAD, multiple ostia, aberrant origin from the opposite/non-coronary sinus of Valsalva, single coronary artery, coronary fistulas, and extracardiac terminations [

44].

5. New Frontiers for CTCA

As CT resolution and data volume increase, we are able to describe plaque characteristics in greater detail than ever before. This provides information about cardiac risk above and beyond that already gained from the anatomical and functional information discussed above [

45]. In this next section, we will discuss two specific features, perivascular fat attenuation and total plaque volume, as well as discussing the role of artificial AI in CTCA.

5.1. Perivascular Fat Attenuation

Atherosclerosis is well-known to have a strong inflammatory component [

46], however recently this has become even a more hot topic in both aspects of diagnosis and management of CAD. The specific CTCA feature of inflammation is perivascular fat attenuation. The fat attenuation index (FAI) is a score, developed in 2017, that grades the degree of attenuation (i.e. signal reduction) in fat around coronary arteries. This has been shown to correlate well with extent of inflammation in histological samples and active inflammation on PET imaging [

47].

In 2024, the UK-based multicentre ORFAN (Inflammatory risk and cardiovascular events in patients without obstructive coronary artery disease) study demonstrated that perivascular fat attenuation independently predicted the occurrence of MACE, independent of traditional risk factors and presence or degree of stenoses [

45]. In this longitudinal cohort study, over 3000 consecutive patients undergoing CTCA were followed up over a median duration of 7.7 years to assess the value of the fat attenuation index (FAI) in the presence and absence of obstructive CAD. The FAI predicted risk of MACE regardless of degree of obstruction and the investigators went on to validate an AI model (named AI-Risk) created a few years earlier from the CRISP-CT study [48, 49] that incorporates the FAI score. The AI-Risk model performed well for predicting cardiac death (HR 6·75; 95% CI 5·17–8·82, p < 0·001, for very high risk vs low/medium risk) and MACE (HR 4·68; 95% CI 3·93–5·57; p < 0·001 for very high risk vs low/medium risk) which suggests that coronary artery inflammation could help us move towards more individualized risk predictions in future. It may even help us identify patients who are more likely to benefit from anti-inflammatory therapies such as colchicine [50-52].

Interestingly, although high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) has been shown to be a predictor of poor cardiac outcomes [53-55], hsCRP has been shown to have no correlation with extent of perivascular fat attenuation [

56]. This may suggest an alternative mechanism for coronary artery inflammation. Investigating this further may lead to new targeted therapeutics.

5.2. Plaque Quantification and Morphology

With a focus moving away from simply degree of stenosis, total plaque quantification and plaque morphology have been shown to be strongly correlated with cardiac risk. Recent data comes from a post-hoc analysis of the ISCHAEMIA trial [

57]. ISCHAEMIA enrolled patients with stable angina, coronary artery stenosis > 50% but excluding left mainstem disease [

58] and the sub-study published last year found total plaque burden to be strongly correlated with cardiovascular death or MI over median follow up 3.3 years (HR 1.56; 95% CI 1.25–1.97 per interquartile range increase (559 mm

3); p = 0.001) [

57]. Adding total plaque burden quantification to known risk factors improved accuracy of the investigators’ model (AUC 0.654 vs. 0.608; p = 0.002), which indicates potential clinical utility of this metric. Crucially, it has been shown to correlate well with the gold standard: intravascular imaging [

59].

This is in keeping with previous findings, including the plaque burden (defined as ratio of plaque volume to vessel volume) being the strongest CT predictor of progression to obstructive CAD [

60]. More specifically, the SCOT-HEART [

61] and CAPIRE (Coronary Atherosclerosis in outlier subjects: Protective and novel Individual Risk factors Evaluation) trials [

62] found that burden of low-attenuation, non-calcified plaques correlated most strongly with future MI, with a stronger association than degree of stenosis, risk scores, calcium scores or total plaque volume.

Clearly there are several features about individual plaques and total plaque burden that are associated with future cardiac risk. There are several risk scores that allow incorporation of detailed plaque characteristics. The first we will discuss is the CT-Leaman score. The Leaman score [

63] was created in 1981 using angiographic characteristics but has since been modified to reflect CT plaque characteristics. The CT-Leaman score [

64] includes location of plaque, degree of stenosis and type of plaque (calcified/non-calcified). Prospective trials have found a CT-Leaman score > 5 (without obstruction) has a similar prognosis to obstructive CAD [

65], it has also been validated in registry data [

66]. The Leiden-CTA score is similar, but with the additional characteristic of a mixed plaque [

67]. More recently is the Coronary Artery Disease-Reporting and Data System (CAD-RADS

TM) 2.0 score, which provides a standardized structure to CTCA reporting and includes more recently discovered features of high-risk plaques, namely spotty calcifications, positive remodeling, low attenuation or napkin-ring sign [

68]. Potential future risk assessment may be provided by Artificial Intelligence, which will be covered in the next section.

5.3. Artificial Intelligence in Cardiac CT

AI is already being used across many steps of the cardiac CT workflow and developments are rapidly progressing, as was acknowledged recently in a joint statement from key US and European Societies [

69]. Whilst roles exist even from the early steps in the CT workflow, including test selection (aided by using large language models [70, 71] and acquisition (for example image reconstruction by deep-learning algorithms allowing lower radiation protocols [

72], in this article the focus will be on image processing, and analysis.

The main advantages of AI-based image analysis are quicker results and less inter-rater and intra-rater variability, as well as potentially opening new avenues for discovery of high-risk plaque characteristics. The main AI methods applied to CTCA are machine learning and deep learning. Machine learning enables algorithms to learn from experience, whether this be supervised or unsupervised. Deep learning is a form of machine learning specifically using artificial neural networks for allow generation of predictions and has been used in the field within the past decade [

73,

74].

AI initially found its feet in cardiac CT with assessment of calcification and subsequently deep learning models now available have excellent correlation with expert readers using the Agatston score [

75]. After calcification assessment, AI models improved at more complex assessment, starting with luminal analysis. AI models are now able to provide reliable results on the degree of luminal stenosis, as well as other high-risk plaque characteristics included in the CAD-RADS score [

76]. Other deep-learning models allow assessment of perivascular fat attenuation and quantitative total plaque burden, as discussed above [57, 77, 78].

Crucially a theme emerges from the literature; that AI risk-prediction models incorporating variables across different domains outperform those that are limited to, for example, imaging characteristics only. This is nicely demonstrated in a 2017 study using 5-year mortality data that found that an AI model using clinical and radiographic characteristics was superior to CAC alone [

79]. This leads us, the authors, to predict more complex deep learning algorithms in the future which may benefit from many inputs to provide a tailored risk profile and perhaps even therapeutic recommendations. The combination of these algorithms and large datasets may also guide future research and open avenues as yet unexplored in the realm of cardiac CT.

6. Use of Computed Tomography in Acute Coronary Syndrome

It is important to note however, use of CTCA is limited as whilst the extent, distribution and characteristics of coronary plaque can be assessed, this alone does not provide accurate risk assessment for individuals. It is widely recognized that most acute MIs are caused by occlusion in vessels with only minor coronary plaque disease that either erodes or ruptures and as such the role in ACS is one that differs from CCS [

80]. In the PROMISE (Prospective Multicenter Imaging Study for Evaluation of Chest Pain) trial, 54% of adverse events occurred in patients with no significant stenosis, while only 12% of the population undergoing CTCA had significant stenosis [

81].

CTCA has been shown as described, to have clear benefit in stable chest pain, for instance in the SCOT-HEART trial, however the role of CTCA in ACS is a developing area [

82]. Given ACS is a significant cause of global mortality and morbidity [

83] optimizing diagnosis and subsequent preventative treatment strategies is of key importance. Current diagnostic methods, through use of ECG and troponin testing, cannot confirm occurrence of atherosclerosis, recognition of which would facilitate improved preventative therapy [

84].

Aforementioned benefits of CT such as its ability to quantify and assess plaque burden and morphology is of benefit in the prevention of ACS as plaques with low HU (i.e., HU <50) have been identified as independent predictors of ACS as well as periprocedural myocardial infarction [

85]. In a secondary analysis of the RAPID-CTCA trial the use of early CTCA on treatment prescription in intermediate-risk ACS patients was assessed. From 1743 patients, 874 patients were randomized to early CTCA compared to standard care. It was observed that prescription of P2Y

12 receptor antagonist, dual antiplatelet, and statin therapies increased more in the early CTCA arm (between-group difference: 4.6% [95% confidence interval, 0.3-8.9], 4.5% [95% confidence interval, 0.2-8.7], and 4.3% [95% confidence interval, 0.2-8.5], respectively [

86]. This suggests that early use of CTCA may enable targeted individualization of preventative therapy based on extent of vessel disease. ESC guidelines for ACS recognise this role of CTCA as a diagnostic aid in patients with low to intermediate risk of ACS, visualizing obstructive pathology for consideration of revascularization or in identification of non-obstructive coronary arteries who could be discharged once other relevant diseases excluded [

87].

Despite the presumed diagnostic aid of CTCA, the BEACON (Better Evaluation of Acute Chest Pain with Computed Tomography Angiography) trial has shown showed no reduction of in-hospital duration of stay or hospital admission in the CTCA arm compared with patients investigated with high sensitivity cardiac troponin [

88]. Further, initial analysis of the RAPID-CTCA trial suggested a default approach of use of CTCA did not improve clinical outcomes at 1 year and was associated with prolonged hospital stay and increased cost [

89].

Given this, a default approach of CTCA as a first-line test in ACS is not advised in the 2023 ESC guidance, however its utility may lie in the identification of obstructive or non-obstructive plaque, guiding medical therapy [

87].

7. CT in Structural Heart Disease Assessment and Intervention

Cardiac CT has applications beyond coronary artery assessment and is widely used in the subspecialty of structural heart disease [

90]. In this article, we will discuss the role it plays in structural heart interventions: notably in TAVI.

Aortic stenosis is the most common valvular heart condition in the UK, with a prevalence of almost 1.5% of the population aged >55 years-old suffering from severe disease [

91]. Historically, the only definitive intervention was surgical valve replacement however development of the transcatheter approach has progressed to the degree that in 2024 it was shown to be non-inferior to surgical valve replacement even for low-risk surgical candidates [

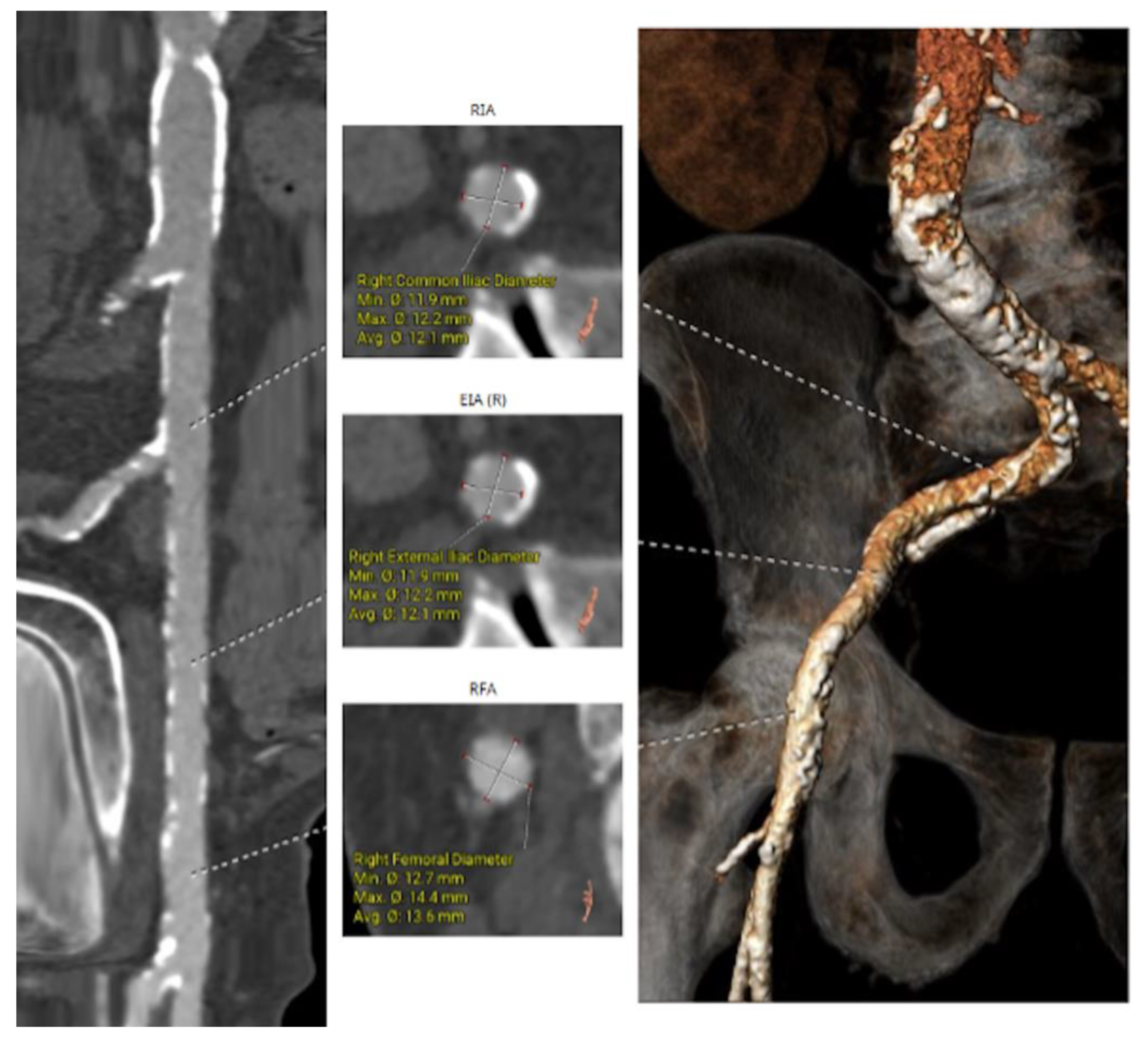

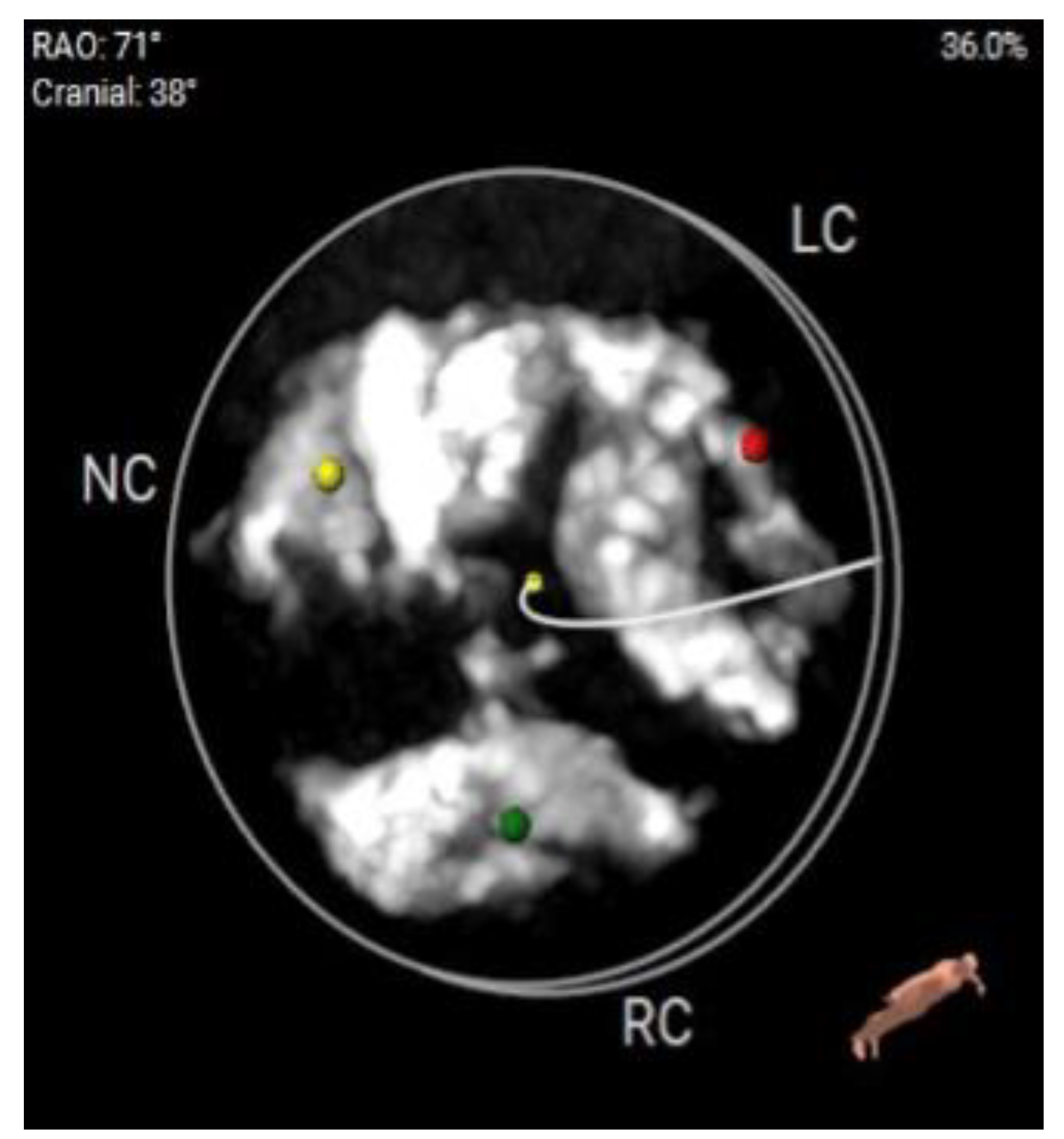

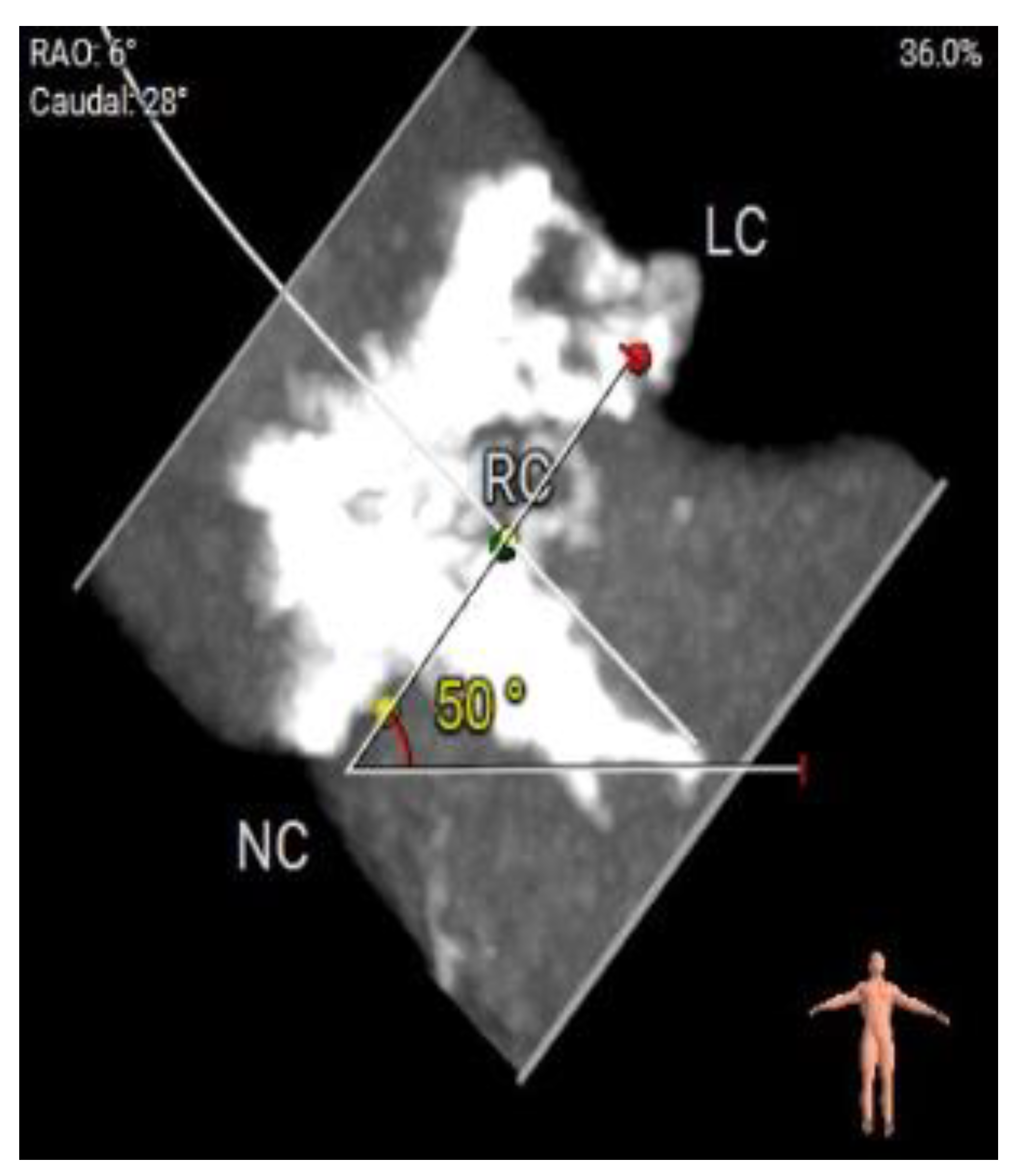

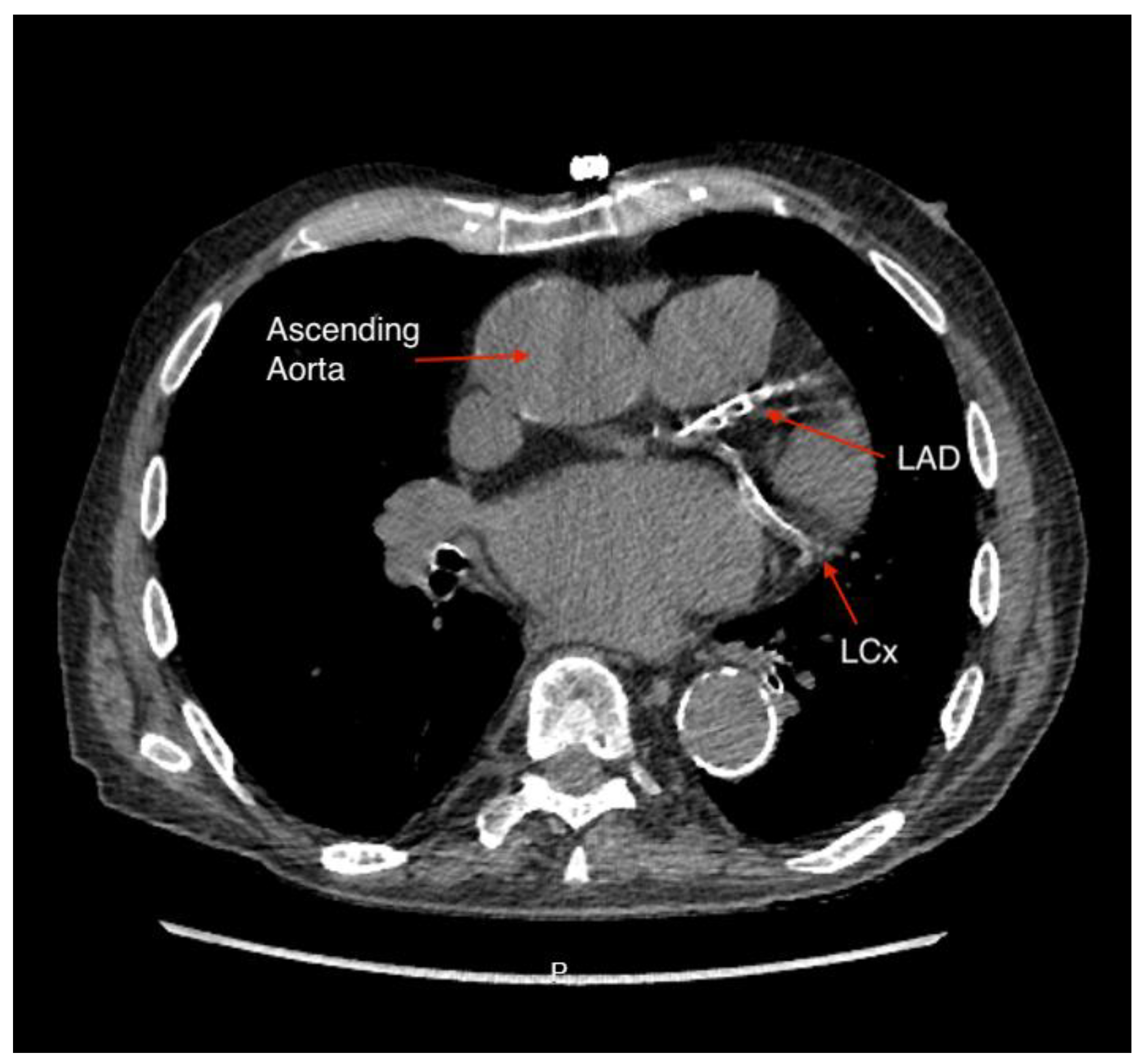

92]. The key variables to assess during TAVI planning include access anatomy (classically with a femoral approach), size of aortic root, prediction of optimal fluoroscopic angles for valve deployment, and assessing risk of coronary artery occlusion, and cardiac CT is able to provide all of these as depicted in figures 4a – 4d below [

93].

Figure 4.

a: CT Angiography for TAVI planning, showing a good transfemoral approach for a trans-catheter valve.

Figure 4.

a: CT Angiography for TAVI planning, showing a good transfemoral approach for a trans-catheter valve.

Figure 4.

b: CT Angiography for TAVI planning at multiple levels for femoral access suitability.

Figure 4.

b: CT Angiography for TAVI planning at multiple levels for femoral access suitability.

Figure 4.

c: Significantly calcified aortic valve cusp with a calcium score of >13000.

Figure 4.

c: Significantly calcified aortic valve cusp with a calcium score of >13000.

Figure 4.

d: Measurement of annulus angulations on CT Angiography.

Figure 4.

d: Measurement of annulus angulations on CT Angiography.

The Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography released a consensus document in 2019 advocating the optimal protocol and how all relevant information can be gathered with one administration of contrast [

94]. The thoracic element of the scan requires ECG-gating to reduce motion artefact and allow precise measurements. Annular measurements are taken (maximum, minimum, and perimeter) to allow for prosthesis-sizing and reduce the chance of mismatch and its related complications [

90]. The coronary ostium height is another vital parameter as low origin of the coronary arteries above the aortic valve leads to a greater risk of ostial occlusion, for which mortality is high [

95]. Additional information is given regarding valve morphology and calcifications. TAVI is occasionally used in bicuspid aortic valves, with similar outcomes at 1 year [

96] however aspects such as raphe with calcification extending into the left ventricular outflow tract are also important to note due to their association with paravalvular leak [

97]. Finally for TAVI, vascular access is evaluated. The transfemoral approach is most common, however if this is not feasible due to tortuosity, caliber, or calcification of iliofemoral vessels, CT can instead assess subclavian or carotid measurements [

90]. In summary, CT provides an enormous amount of information for planning all aspects of TAVI.

8. Conclusions

As a non-invasive tool, cardiac CT is now at the forefront of cardiovascular care. In CAD, CT can help guide diagnostic evaluation, planning of intervention (FFRCT data, best fluoroscopy projection for intervention and adjunctive calcium modification techniques) as well as stent sizing and landing zones. It also, undoubtedly, a major cornerstone in assessment and management of structural heart disease interventions, particularly in TAVI.

9. Future Directions

Future considerations include deep integration of machine learning and AI in all stages of cardiac CT. This will enhance temporal resolution, reduce artefacts and radiation exposure, with improved diagnostic accuracy. The resultant precision in detailed coronary plaque analysis will help risk stratification and treatment planning leading to improved patient outcomes. Emerging technologies such as dual-source photon-counting detector (PCD) CT is a valuable tool to overcome artefacts caused by heavy calcification which often leads to overestimation of CAD severity. Unlike conventional energy-integrating detector (EID) CT, PCD CT directly converts x-ray photons into electrical signals, bypassing the need for image noise, which helps minimize artefacts and improves clinical efficiency. PCD allows for better visualization of plaque burden and coronary vessel stenosis, offering excellent interpretation of heavily calcified plaques and may reduce rates of referrals for ICA compared to EID CT [

98].

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org. available upon request from the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: ZS, methodology: ZS, AI, resources: OH, TS, AD, writing—original draft preparation: OH, AI, TS review and editing: all authors, visualization: ZS, AI, AD, supervision: ZS, project administration: ZS, AI, funding acquisition: Not applicable. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Feuchtner GM, Plank F, Beyer C, Barbieri F, Widmann G, Spitaler P, et al. Cardiac Computed Tomography: State of the Art and Future Horizons. J Clin Med. 11. Switzerland2022.

- Pontone G, Rossi A, Guglielmo M, Dweck MR, Gaemperli O, Nieman K, et al. Clinical applications of cardiac computed tomography: a consensus paper of the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging-part II. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2022, 23, 23–e61. [Google Scholar]

- Abbara S, Shaw LJ. Past. Present, and Future of CCTA. Circulation 2024, 150, 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vrints C, Andreotti F, Koskinas KC, Rossello X, Adamo M, Ainslie J, et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of chronic coronary syndromes: Developed by the task force for the management of chronic coronary syndromes of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Endorsed by the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). European Heart Journal. 2024, 45, 3415–537. [Google Scholar]

- Rajiah P, Schoenhagen P. The role of computed tomography in pre-procedural planning of cardiovascular surgery and intervention. Insights Imaging. 2013;4(5):671-89.

- Yusuf S, Reddy S, Ounpuu S, Anand S. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases: part I: general considerations, the epidemiologic transition, risk factors, and impact of urbanization. Circulation. 2001;104(22):2746-53.

- Berry C, Kramer CM, Kunadian V, Patel TR, Villines T, Kwong RY, et al. Great Debate: Computed tomography coronary angiography should be the initial diagnostic test in suspected angina. Eur Heart J. 2023;44(26):2366-75.

- Hell MM, Achenbach S. CT support of cardiac structural interventions. Br J Radiol. 2019;92(1098):20180707.

- Magalhães TA, Cury RC, Cerci RJ, Parga Filho JR, Gottlieb I, Nacif MS, et al. Evaluation of Myocardial Perfusion by Computed Tomography - Principles, Technical Background and Recommendations. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2019;113(4):758-67.

- Knuuti J, Wijns W, Saraste A, Capodanno D, Barbato E, Funck-Brentano C, et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(3):407-77.

- Knuuti J, Ballo H, Juarez-Orozco LE, Saraste A, Kolh P, Rutjes AWS, et al. The performance of non-invasive tests to rule-in and rule-out significant coronary artery stenosis in patients with stable angina: a meta-analysis focused on post-test disease probability. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(35):3322-30.

- McKavanagh P, Lusk L, Ball PA, Verghis RM, Agus AM, Trinick TR, et al. A comparison of cardiac computerized tomography and exercise stress electrocardiogram test for the investigation of stable chest pain: the clinical results of the CAPP randomized prospective trial. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015, 16, 441–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams MC, Wereski R, Tuck C, Adamson PD, Shah ASV, van Beek EJR, et al. Coronary CT angiography-guided management of patients with stable chest pain: 10-year outcomes from the SCOT-HEART randomised controlled trial in Scotland. Lancet. 2025;405(10475):329-37.

- Lima MR, Lopes PM, Ferreira AM. Use of coronary artery calcium score and coronary CT angiography to guide cardiovascular prevention and treatment. Ther Adv Cardiovasc Dis. 2024;18:17539447241249650.

- Agha AM, Pacor J, Grandhi GR, Mszar R, Khan SU, Parikh R, et al. The Prognostic Value of CAC Zero Among Individuals Presenting With Chest Pain: A Meta-Analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2022;15(10):1745-57.

- Lubbers M, Dedic A, Coenen A, Galema T, Akkerhuis J, Bruning T, et al. Calcium imaging and selective computed tomography angiography in comparison to functional testing for suspected coronary artery disease: the multicentre, randomized CRESCENT trial. Eur Heart J. 2016, 37, 1232–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biavati F, Saba L, Boussoussou M, Kofoed KF, Benedek T, Donnelly P, et al. Coronary Artery Calcium Score Predicts Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events in Stable Chest Pain. Radiology. 2024;310(3):e231557.

- Yoshida K, Tanabe Y, Hosokawa T, Morikawa T, Fukuyama N, Kobayashi Y, et al. Coronary computed tomography angiography for clinical practice. Jpn J Radiol. 2024;42(6):555-80.

- Williams MC, Moss AJ, Dweck M, Adamson PD, Alam S, Hunter A, et al. Coronary Artery Plaque Characteristics Associated With Adverse Outcomes in the SCOT-HEART Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(3):291-301.

- Sun Z, Xu L. Coronary CT angiography in the quantitative assessment of coronary plaques. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:346380.

- Serruys PW, Kotoku N, Nørgaard BL, Garg S, Nieman K, Dweck MR, et al. Computed tomographic angiography in coronary artery disease. EuroIntervention. 2023;18(16):e1307-e27.

- Collet C, Onuma Y, Cavalcante R, Grundeken M, Généreux P, Popma J, et al. Quantitative angiography methods for bifurcation lesions: a consensus statement update from the European Bifurcation Club. EuroIntervention. 2017;13(1):115-23.

- Collet C, Sonck J, Leipsic J, Monizzi G, Buytaert D, Kitslaar P, et al. Implementing Coronary Computed Tomography Angiography in the Catheterization Laboratory. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021, 14, 1846–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreini D, Mushtaq S, Pontone G, Conte E, Guglielmo M, Annoni A, et al. Diagnostic performance of coronary CT angiography carried out with a novel whole-heart coverage high-definition CT scanner in patients with high heart rate. Int J Cardiol. 2018;257:325-31.

- Généreux P, Madhavan MV, Mintz GS, Maehara A, Palmerini T, Lasalle L, et al. Ischemic outcomes after coronary intervention of calcified vessels in acute coronary syndromes. Pooled analysis from the HORIZONS-AMI (Harmonizing Outcomes With Revascularization and Stents in Acute Myocardial Infarction) and ACUITY (Acute Catheterization and Urgent Intervention Triage Strategy) TRIALS. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(18):1845-54.

- Ali ZA, Brinton TJ, Hill JM, Maehara A, Matsumura M, Karimi Galougahi K, et al. Optical Coherence Tomography Characterization of Coronary Lithoplasty for Treatment of Calcified Lesions: First Description. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;10(8):897-906.

- Mancini GBJ, Leipsic J, Budoff MJ, Hague CJ, Min JK, Stevens SR, et al. CT Angiography Followed by Invasive Angiography in Patients With Moderate or Severe Ischemia-Insights From the ISCHEMIA Trial. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging. 2021;14(7):1384-93.

- Sykes R, Collison D, Merkely B, Kofoed KF, Donnelly P, Rodríguez-Palomares J, et al. Effect of Body Mass Index on Effectiveness of CT versus Invasive Coronary Angiography in Stable Chest Pain: The DISCHARGE Trial. Radiology. 2024;310(2):e230591.

- Salib A, Hay M, Muthalaly R, Abrahams T, Sultana N, Kanna R, et al. Computed Tomography Coronary Angiography Is Feasible and Reliable for Proximal Coronary Segment Interpretation in Patients with Elevated Body Mass Index. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2024;11(12).

- Lu MT, Ferencik M, Roberts RS, Lee KL, Ivanov A, Adami E, et al. Noninvasive FFR Derived From Coronary CT Angiography: Management and Outcomes in the PROMISE Trial. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;10(11):1350-8.

- Rabbat M, Leipsic J, Bax J, Kauh B, Verma R, Doukas D, et al. Fractional Flow Reserve Derived from Coronary Computed Tomography Angiography Safely Defers Invasive Coronary Angiography in Patients with Stable Coronary Artery Disease. J Clin Med. 2020;9(2).

- Jones DA, Beirne AM, Kelham M, Rathod KS, Andiapen M, Wynne L, et al. Computed Tomography Cardiac Angiography Before Invasive Coronary Angiography in Patients With Previous Bypass Surgery: The BYPASS-CTCA Trial. Circulation. 2023;148(18):1371-80.

- Taylor CA, Fonte TA, Min JK. Computational fluid dynamics applied to cardiac computed tomography for noninvasive quantification of fractional flow reserve: scientific basis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013, 61, 2233–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajiah P, Maroules CD. Myocardial ischemia testing with computed tomography: emerging strategies. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2017;7(5):475-88.

- Collet C, Miyazaki Y, Ryan N, Asano T, Tenekecioglu E, Sonck J, et al. Fractional Flow Reserve Derived From Computed Tomographic Angiography in Patients With Multivessel CAD. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(24):2756-69.

- Curzen N, Nicholas Z, Stuart B, Wilding S, Hill K, Shambrook J, et al. Fractional flow reserve derived from computed tomography coronary angiography in the assessment and management of stable chest pain: the FORECAST randomized trial. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(37):3844-52.

- Yang J, Shan D, Wang X, Sun X, Shao M, Wang K, et al. On-Site Computed Tomography-Derived Fractional Flow Reserve to Guide Management of Patients With Stable Coronary Artery Disease: The TARGET Randomized Trial. Circulation. 2023;147(18):1369-81.

- Celeng C, Leiner T, Maurovich-Horvat P, Merkely B, de Jong P, Dankbaar JW, et al. Anatomical and Functional Computed Tomography for Diagnosing Hemodynamically Significant Coronary Artery Disease: A Meta-Analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019, 12 (7 Pt 2), 1316–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mickley H, Veien KT, Gerke O, Lambrechtsen J, Rohold A, Steffensen FH, et al. Diagnostic and Clinical Value of FFR(CT) in Stable Chest Pain Patients With Extensive Coronary Calcification: The FACC Study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2022;15(6):1046-58.

- Rochitte CE, George RT, Chen MY, Arbab-Zadeh A, Dewey M, Miller JM, et al. Computed tomography angiography and perfusion to assess coronary artery stenosis causing perfusion defects by single photon emission computed tomography: the CORE320 study. Eur Heart J. 2014;35(17):1120-30.

- Capretti G, Mitomo S, Giglio M, Colombo A, Chieffo A. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: how often do we miss this diagnosis? The role of cardiac computed tomography angiography. Future Cardiol. 2019;15(5):333-8.

- Rovera C, Moretti C, Bisanti F, De Zan G, Guglielmo M. Myocardial Bridging: Review on the Role of Coronary Computed Tomography Angiography. J Clin Med. 2023;12(18).

- Agarwal PP, Dennie C, Pena E, Nguyen E, LaBounty T, Yang B, et al. Anomalous Coronary Arteries That Need Intervention: Review of Pre- and Postoperative Imaging Appearances. Radiographics. 2017;37(3):740-57.

- Baz RO, Refi D, Scheau C, Savulescu-Fiedler I, Baz RA, Niscoveanu C. Coronary Artery Anomalies: A Computed Tomography Angiography Pictorial Review. J Clin Med. 2024;13(13).

- Chan K, Wahome E, Tsiachristas A, Antonopoulos AS, Patel P, Lyasheva M, et al. Inflammatory risk and cardiovascular events in patients without obstructive coronary artery disease: the ORFAN multicentre, longitudinal cohort study. Lancet. 2024;403(10444):2606-18.

- Ross, R. Atherosclerosis--an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(2):115-26.

- Antonopoulos AS, Sanna F, Sabharwal N, Thomas S, Oikonomou EK, Herdman L, et al. Detecting human coronary inflammation by imaging perivascular fat. Sci Transl Med. 2017;9(398).

- Oikonomou EK, Marwan M, Desai MY, Mancio J, Alashi A, Hutt Centeno E, et al. Non-invasive detection of coronary inflammation using computed tomography and prediction of residual cardiovascular risk (the CRISP CT study): a post-hoc analysis of prospective outcome data. Lancet. 2018;392(10151):929-39.

- Oikonomou EK, Antonopoulos AS, Schottlander D, Marwan M, Mathers C, Tomlins P, et al. Standardized measurement of coronary inflammation using cardiovascular computed tomography: integration in clinical care as a prognostic medical device. Cardiovasc Res. 2021;117(13):2677-90.

- Tardif JC, Kouz S, Waters DD, Bertrand OF, Diaz R, Maggioni AP, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Low-Dose Colchicine after Myocardial Infarction. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(26):2497-505.

- Nidorf SM, Fiolet ATL, Mosterd A, Eikelboom JW, Schut A, Opstal TSJ, et al. Colchicine in Patients with Chronic Coronary Disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(19):1838-47.

- Yu M, Yang Y, Dong SL, Zhao C, Yang F, Yuan YF, et al. Effect of Colchicine on Coronary Plaque Stability in Acute Coronary Syndrome as Assessed by Optical Coherence Tomography: The COLOCT Randomized Clinical Trial. Circulation. 2024;150(13):981-93.

- Ridker PM, Bhatt DL, Pradhan AD, Glynn RJ, MacFadyen JG, Nissen SE. Inflammation and cholesterol as predictors of cardiovascular events among patients receiving statin therapy: a collaborative analysis of three randomised trials. Lancet. 2023;401(10384):1293-301.

- Ridker PM, Lei L, Louie MJ, Haddad T, Nicholls SJ, Lincoff AM, et al. Inflammation and Cholesterol as Predictors of Cardiovascular Events Among 13 970 Contemporary High-Risk Patients With Statin Intolerance. Circulation. 2024;149(1):28-35.

- Ridker PM, Moorthy MV, Cook NR, Rifai N, Lee IM, Buring JE. Inflammation, Cholesterol, Lipoprotein(a), and 30-Year Cardiovascular Outcomes in Women. N Engl J Med. 2024;391(22):2087-97.

- Dai X, Deng J, Yu M, Lu Z, Shen C, Zhang J. Perivascular fat attenuation index and high-risk plaque features evaluated by coronary CT angiography: relationship with serum inflammatory marker level. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;36(4):723-30.

- Nurmohamed NS, Min JK, Anthopolos R, Reynolds HR, Earls JP, Crabtree T, et al. Atherosclerosis quantification and cardiovascular risk: the ISCHEMIA trial. Eur Heart J. 2024;45(36):3735-47.

- Maron DJ, Hochman JS, Reynolds HR, Bangalore S, O'Brien SM, Boden WE, et al. Initial Invasive or Conservative Strategy for Stable Coronary Disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(15):1395-407.

- Conte E, Mushtaq S, Pontone G, Li Piani L, Ravagnani P, Galli S, et al. Plaque quantification by coronary computed tomography angiography using intravascular ultrasound as a reference standard: a comparison between standard and last generation computed tomography scanners. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;21(2):191-201.

- Lee SE, Sung JM, Andreini D, Al-Mallah MH, Budoff MJ, Cademartiri F, et al. Differences in Progression to Obstructive Lesions per High-Risk Plaque Features and Plaque Volumes With CCTA. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;13(6):1409-17.

- Williams MC, Kwiecinski J, Doris M, McElhinney P, D'Souza MS, Cadet S, et al. Low-Attenuation Noncalcified Plaque on Coronary Computed Tomography Angiography Predicts Myocardial Infarction: Results From the Multicenter SCOT-HEART Trial (Scottish Computed Tomography of the HEART). Circulation. 2020;141(18):1452-62.

- Andreini D, Magnoni M, Conte E, Masson S, Mushtaq S, Berti S, et al. Coronary Plaque Features on CTA Can Identify Patients at Increased Risk of Cardiovascular Events. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;13(8):1704-17.

- Leaman DM, Brower RW, Meester GT, Serruys P, van den Brand M. Coronary artery atherosclerosis: severity of the disease, severity of angina pectoris and compromised left ventricular function. Circulation. 1981;63(2):285-99.

- de Araújo Gonçalves P, Garcia-Garcia HM, Dores H, Carvalho MS, Jerónimo Sousa P, Marques H, et al. Coronary computed tomography angiography-adapted Leaman score as a tool to noninvasively quantify total coronary atherosclerotic burden. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;29(7):1575-84.

- Mushtaq S, De Araujo Gonçalves P, Garcia-Garcia HM, Pontone G, Bartorelli AL, Bertella E, et al. Long-term prognostic effect of coronary atherosclerotic burden: validation of the computed tomography-Leaman score. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8(2):e002332.

- Andreini D, Pontone G, Mushtaq S, Gransar H, Conte E, Bartorelli AL, et al. Long-term prognostic impact of CT-Leaman score in patients with non-obstructive CAD: Results from the COronary CT Angiography EvaluatioN For Clinical Outcomes InteRnational Multicenter (CONFIRM) study. Int J Cardiol. 2017;231:18-25.

- van Rosendael AR, Shaw LJ, Xie JX, Dimitriu-Leen AC, Smit JM, Scholte AJ, et al. Superior Risk Stratification With Coronary Computed Tomography Angiography Using a Comprehensive Atherosclerotic Risk Score. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;12(10):1987-97.

- Cury RC, Leipsic J, Abbara S, Achenbach S, Berman D, Bittencourt M, et al. CAD-RADS™ 2.0 - 2022 Coronary Artery Disease-Reporting and Data System: An Expert Consensus Document of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography (SCCT), the American College of Cardiology (ACC), the American College of Radiology (ACR), and the North America Society of Cardiovascular Imaging (NASCI). J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2022;16(6):536-57.

- Mastrodicasa D, van Assen M, Huisman M, Leiner T, Williamson EE, Nicol ED, et al. Use of AI in Cardiac CT and MRI: A Scientific Statement from the ESCR, EuSoMII, NASCI, SCCT, SCMR, SIIM, and RSNA. Radiology. 2025;314(1):e240516.

- Bizzo BC, Almeida RR, Michalski MH, Alkasab TK. Artificial Intelligence and Clinical Decision Support for Radiologists and Referring Providers. J Am Coll Radiol. 2019;16(9 Pt B):1351-6.

- Ranschaert E, Topff L, Pianykh O. Optimization of Radiology Workflow with Artificial Intelligence. Radiol Clin North Am. 2021;59(6):955-66.

- Benz DC, Benetos G, Rampidis G, von Felten E, Bakula A, Sustar A, et al. Validation of deep-learning image reconstruction for coronary computed tomography angiography: Impact on noise, image quality and diagnostic accuracy. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2020;14(5):444-51.

- Lin A, Manral N, McElhinney P, Killekar A, Matsumoto H, Kwiecinski J, et al. Deep learning-enabled coronary CT angiography for plaque and stenosis quantification and cardiac risk prediction: an international multicentre study. Lancet Digit Health. 2022;4(4):e256-e65.

- Hampe N, Wolterink JM, van Velzen SGM, Leiner T, Išgum I. Machine Learning for Assessment of Coronary Artery Disease in Cardiac CT: A Survey. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2019;6:172.

- Eng D, Chute C, Khandwala N, Rajpurkar P, Long J, Shleifer S, et al. Automated coronary calcium scoring using deep learning with multicenter external validation. npj Digital Medicine. 2021;4(1):88.

- Herten V, Hampe N, Takx RAP, Franssen KJ, Wang Y, Sucha D, et al. Automatic Coronary Artery Plaque Quantification and CAD-RADS Prediction Using Mesh Priors. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2024;43(4):1272-83.

- Nadjiri J, Hausleiter J, Jähnichen C, Will A, Hendrich E, Martinoff S, et al. Incremental prognostic value of quantitative plaque assessment in coronary CT angiography during 5 years of follow up. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2016;10(2):97-104.

- Wang Y, Chen H, Sun T, Li A, Wang S, Zhang J, et al. Risk predicting for acute coronary syndrome based on machine learning model with kinetic plaque features from serial coronary computed tomography angiography. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2022;23(6):800-10.

- Motwani M, Dey D, Berman DS, Germano G, Achenbach S, Al-Mallah MH, et al. Machine learning for prediction of all-cause mortality in patients with suspected coronary artery disease: a 5-year multicentre prospective registry analysis. Eur Heart J. 2017;38(7):500-7.

- Channon KM, Newby DE, Nicol ED, Deanfield J. Cardiovascular computed tomography imaging for coronary artery disease risk: plaque, flow and fat. Heart. 2022;108(19):1510-5.

- Hoffmann U, Ferencik M, Udelson JE, Picard MH, Truong QA, Patel MR, et al. Prognostic Value of Noninvasive Cardiovascular Testing in Patients With Stable Chest Pain: Insights From the PROMISE Trial (Prospective Multicenter Imaging Study for Evaluation of Chest Pain). Circulation. 2017;135(24):2320-32.

- CT coronary angiography in patients with suspected angina due to coronary heart disease (SCOT-HEART): an open-label, parallel-group, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2015;385(9985):2383-91.

- Anderson JL, Morrow DA. Acute Myocardial Infarction. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(21):2053-64.

- Saba, L. Expanding the horizons of suspected acute coronary syndrome management: insights from the RAPID-CTCA trial. AME Clinical Trials Review. 2024;2.

- Motoyama S, Sarai M, Harigaya H, Anno H, Inoue K, Hara T, et al. Computed tomographic angiography characteristics of atherosclerotic plaques subsequently resulting in acute coronary syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(1):49-57.

- Wang KL, Meah MN, Bularga A, Oatey K, O'Brien R, Smith JE, et al. Early computed tomography coronary angiography and preventative treatment in patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome: A secondary analysis of the RAPID-CTCA trial. Am Heart J. 2023;266:138-48.

- Byrne RA, Rossello X, Coughlan JJ, Barbato E, Berry C, Chieffo A, et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes: Developed by the task force on the management of acute coronary syndromes of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). European Heart Journal. 2023;44(38):3720-826.

- Dedic A, Lubbers MM, Schaap J, Lammers J, Lamfers EJ, Rensing BJ, et al. Coronary CT Angiography for Suspected ACS in the Era of High-Sensitivity Troponins: Randomized Multicenter Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(1):16-26.

- Gray AJ, Roobottom C, Smith JE, Goodacre S, Oatey K, O'Brien R, et al. Early computed tomography coronary angiography in patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome: randomised controlled trial. Bmj. 2021;374:n2106.

- Revels JW, Wang SS, Gharai LR, Febbo J, Fadl S, Bastawrous S. The role of CT in planning percutaneous structural heart interventions: Where to measure and why. Clin Imaging. 2021;76:247-64.

- Strange GA, Stewart S, Curzen N, Ray S, Kendall S, Braidley P, et al. Uncovering the treatable burden of severe aortic stenosis in the UK. Open Heart. 2022;9(1).

- Blankenberg S, Seiffert M, Vonthein R, Baumgartner H, Bleiziffer S, Borger MA, et al. Transcatheter or Surgical Treatment of Aortic-Valve Stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2024;390(17):1572-83.

- Hell MM, Emrich T, Lurz P, von Bardeleben RS, Schmermund A. Cardiac CT Beyond Coronaries: Focus on Structural Heart Disease. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2023;20(6):484-92.

- Blanke P, Weir-McCall JR, Achenbach S, Delgado V, Hausleiter J, Jilaihawi H, et al. Computed Tomography Imaging in the Context of Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation (TAVI)/Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement (TAVR): An Expert Consensus Document of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;12(1):1-24.

- Ribeiro HB, Nombela-Franco L, Urena M, Mok M, Pasian S, Doyle D, et al. Coronary obstruction following transcatheter aortic valve implantation: a systematic review. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;6(5):452-61.

- Halim SA, Edwards FH, Dai D, Li Z, Mack MJ, Holmes DR, et al. Outcomes of Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement in Patients With Bicuspid Aortic Valve Disease: A Report From the Society of Thoracic Surgeons/American College of Cardiology Transcatheter Valve Therapy Registry. Circulation. 2020;141(13):1071-9.

- Yoon SH, Bleiziffer S, De Backer O, Delgado V, Arai T, Ziegelmueller J, et al. Outcomes in Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement for Bicuspid Versus Tricuspid Aortic Valve Stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(21):2579-89.

- Simon J, Hrenkó Á, Kerkovits NM, Nagy K, Vértes M, Balogh H, et al. Photon-counting detector CT reduces the rate of referrals to invasive coronary angiography as compared to CT with whole heart coverage energy-integrating detector. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2024;18(1):69-74.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).