Submitted:

20 February 2025

Posted:

21 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Trioza Magnisetosa Loginova, 1964

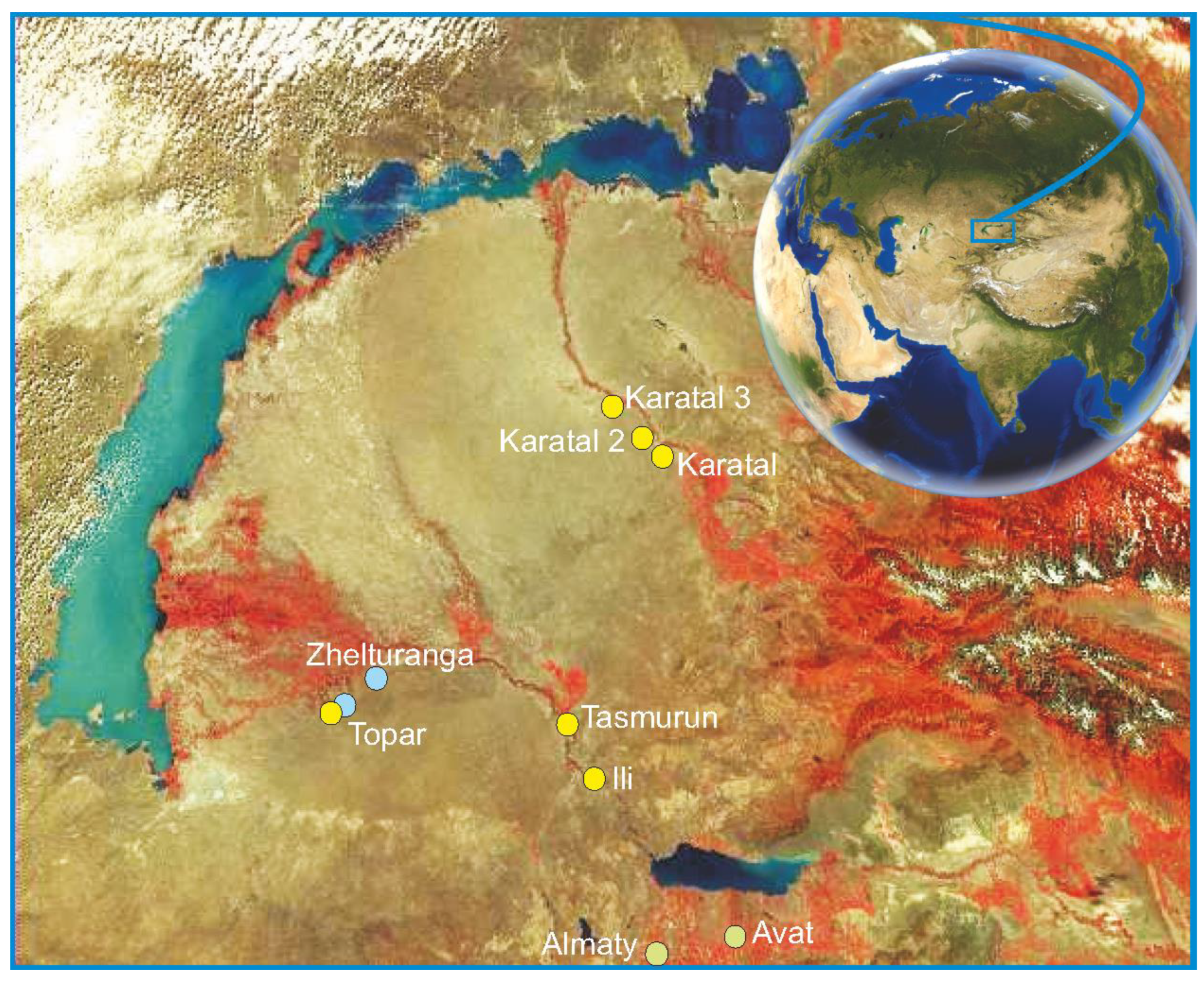

3.1.1. Distribution

3.1.2. Habitats

3.1.3. Host-Plants

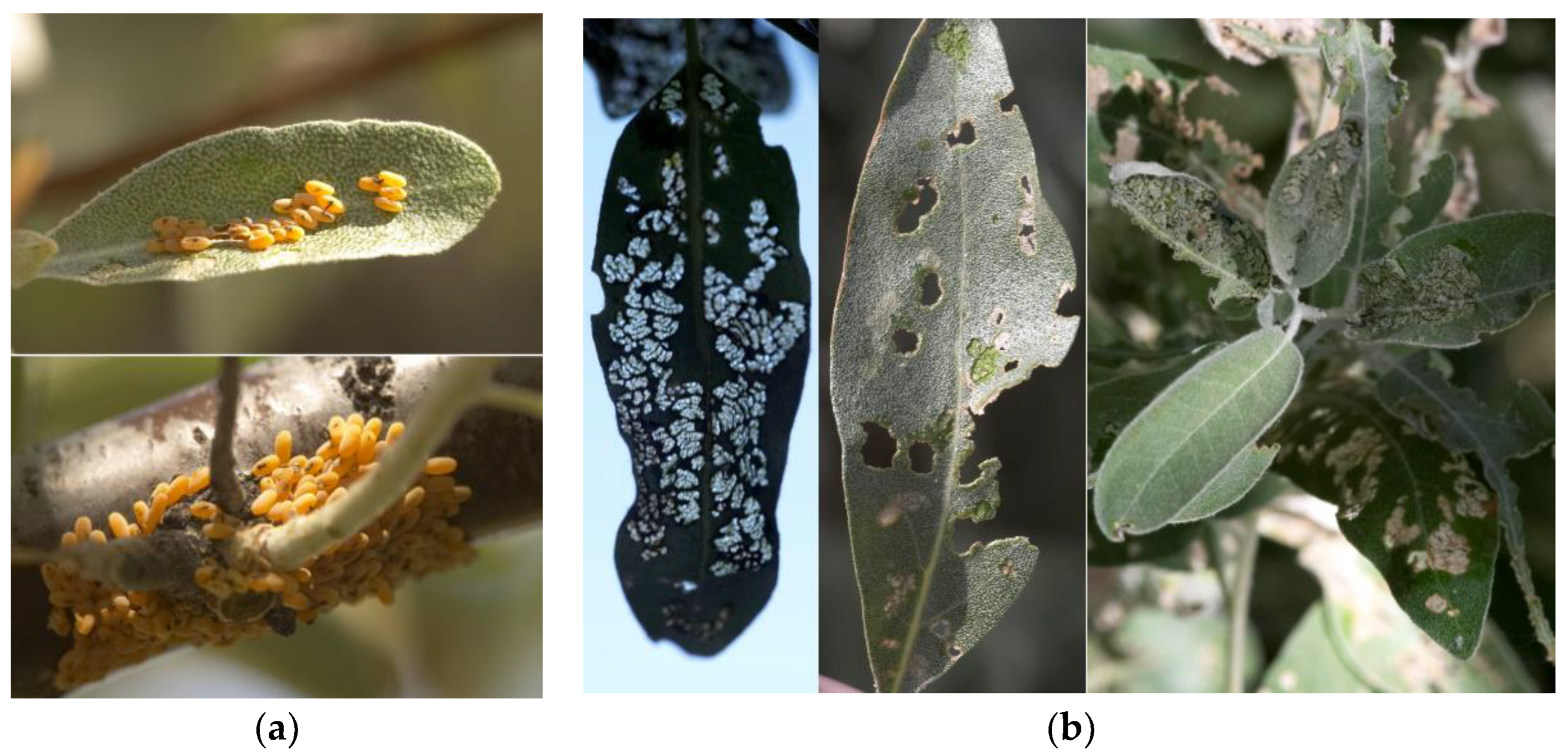

3.1.4. Biological and Phenological Features

3.1.5. Parasites

3.1.6. Efficiency for Biological Control

3.1.7. Testing in Nature

3.2. Altica Balassogloi (Jakobson, 1892) Lepidoptera, Chrysomelidae (=Haltica suvorovi Ogl., H. lopatini Pal.)

3.2.1. Distribution

3.2.2. Habitats

3.2.3. Host-Plants

3.2.4. Biological and Phenological Features

3.2.5. Monitoring of Modern Populations

3.2.6. Efficiency for Biological Control

3.2.7. Testing in Nature Control

3.3. Preliminary Annotated List of Insect Species Damaging to Russian Olive in Central Asia

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baitenov, M.S. Flora Kazakhstana, rodovoy kompleks flory; Gylym: Almaty, Kazakhstan, 2001; Volume 2, pp. 1—280. (=Flora of Kazakhstan, generic complex of flora).

- Abdulina, S.A. Spisok sosydistykh rasteniy Kazakhstana; Editor Kamelin, R.V.; Gylym: Almaty, Kazakhstan, 1999; pp. 1—187. (List of vascular plants in Kazakhstan).

- Vrednye zhivotnye Sredney Azii, Editor Pavlovskiy, E.N.; USSR Academy of Sciences: Moscow—Leningrad, USSR, 1949; pp. 1—404. (=Harmful animals of Central Asia).

- Vorontsov, A.I. Vrediteli lesomeliorativnykh posadok zapadnogo Kazakhstana i Zavolzhiya. Itogi raboty VIZR za 1936 g.; VIZR: Leningrad, USSR, part 1, pp. 202—-205. (=Pests of forest landings in Western Kazakhstan and the Volga region. Results of the VIZR’s work for 1936).

- Grechkin, V.P. Ocherki po biologii vrediteley lesa; Moscow, USSR, 1951; pp. 75-90, 128-135. (=Essays on the biology of forest pests).

- Vorontsov, A.I.; Zakharchenko, I.S. Lokhoviy izmenchiviy usach i mery boriby s nim. In Sbornik rabot po lesozaschite; Moscow Forestry Institute: Moscow, USSR, 1957; Part 1, pp. 46–54. (=The grape wood borer (Chlorophorus varius) and measures to combat it).

- Makhnovskiy, I.K. Vrediteli zaschitnykh lesonasazhdeniy Sredney Azii i boriba s nimi; Tashkent, 1955; pp. 43—166. (=Pests of protective forest plantations in Central Asia and their control).

- Makhnovskiy, I.K. Vrediteli drevesno-kustarnikovoy rastitelnosti Chirchik-Angrenskogo gorno-lesnogo massiva i boriba s nimi. In Trudy of the Central Asian Institute of Forestry of the Uzbek Academy of Agricultural Sciences; Tashkent, 1959; Issue 5, pp. 13—56.

- (=Pests of wood and shrub vegetation of the Chirchik-Angren mountain forest massif and their control).

- Rafes, M.P. Vrednye nasekomye lokha, dzhuzguna i tamariska, proizrastayuschikh na Narynskikh peskakh polupustynnogo Zavolzhiya Entomologicheskoe Obozrenie 1956, 35(4), 805-817. (=Pest insects of oleaster, Calligonum and tamarisk, that grow on the Naryn Sands of the semi-desert Zavolzhye).

- Parfentiev, V.Ya. Lokhoviy listed Haltica suvorovi Ogl. (Coleoptera, Chrysomelidae) v tugainykh lesakh Kazakhstana. Entomologicheskoe Obozrenie 1957, 36(1), 96—97. (=Oleaster leaf beetle Haltica suvorovi Ogl. (Coleoptera, Chrysomelidae) in the tugai forests of Kazakhstan).

- Kuznetsov, A.V. Lokhovoya moli Anarsia eleagnella W. Kuzn. sp. n. (Lepidoptera, Gelechiidae) – novyi vreditel lokha v SSSR. Zoologicheskiy zhurnal 1957, 36(7), 1096—1098. (=Oleaster moth Anarsia eleagnella W. Kuzn. sp. n. (Lepidoptera, Gelechiidae) – new pest of oleaster in the USSR).

- Matesova, G.Ya., 1958. Заметки пo биoлoгии червецoв и щитoвoк (Hom. Coccoidea) Югo-Вoстoчнoгo Казахстана. In Trudy of Instituta Zoologii Akademii Nauk Kazakhskoy SSR; Alma-Ata,1958; Issue 8, pp. 130—137. (=Notes on the biology of mealybugs and scale insects (Homoptera, Coccoidea) of South-Eastern Kazakhstan).

- Kostin, I.A. Materialy po faune koroedov Kazakhstana (Coleoptera, Ipidae). In Trudy of Instituta Zoologii Akademii Nauk Kazakhskoy SSR; Alma-Ata,1960; Issue 11, pp. 129—136. (=Materials on bark beetle fauna in Kazakhstan (Coleoptera, Ipidae).

- Mityaev, I.D. K faune nasekomykh – vrediteley lokha v Kazakhstane. In Trudy of Instituta Zoologii Akademii Nauk Kazakhskoy SSR; Alma-Ata,1960; Issue 11, pp. 108—128. (=To the fauna of oleaster insect pests in Kazakhstan).

- Mityaev, I.D. Nasekomye, vredyaschie lokhu (Eleagnus angustifolia L.) v kulturnoy zone yuzhnykh oblastey Kazakhstana. In Trudy of Instituta Zoologii Akademii Nauk Kazakhskoy SSR; Alma-Ata,1962; Issue 18, pp. 61—68. (=Insects that harm Russian Olive (Elaeagnus angustifolia L.) in the cultural zone of the southern regions of Kazakhstan).

- Sinadskiy, Yu.V. Vrediteli tugainykh lesov Sredney Azii i mery boriby s nimi; Nauka: Moscow-Leningrad, USSR, 1963; pp. 1—150. (=Pests of Central Asian tugai forests and measures to control them).

- Skopin, N.G. Nasekomye – vrediteli lesoposadok v peskakh Bolishie Barsuki i puti boriby s nimi. Uchenye zapiski KazGU 1955, 27, 84—101. (=Insects - pests of forest plantations in the sand Big Barsuki and ways to fight them).

- Sinadskiy, Yu.V., 1958. Siniy listoed – Haltica deserticola Parf., vreditel lokha uzkolistnogo v tugayakh reki Syrdariya. In Nauchnye doklady vyshey shkoly. Lesoinzhenernoye delo; Nauka: Moskva-Leningrad, USSR, 1958; Issue 3, pp. 47—50. (=Blue leaf beetle – Haltica deserticola Parf., Russian Olive pest in the riparian forests of the Syr Darya river).

- Sinadskiy, Yu.V. Vrednaya entomofauna lokha (dzhidy) v tugainykh lesakh Sredney Azii i Kazakhstana. Zoologicheskiy zhurnal 1961, 40(7), 1019—1029. (=Harmful entomofauna of oleaster (dzhida) in the tugai forests of Central Asia and Kazakhstan).

- Sinadskiy, Yu.V. Dendrofilinye nasekomye pustyn’ Sredney Azii i Kazakhstana I mery boriby s nimi; Nauka: Moscow, USSR, 1968; pp. 1—126. (=Dendrophilous insects of the deserts of Central Asia and Kazakhstan and measures to combat them).

- Emeljanov, A.F., 1964. Noviy vid roda Macropsis Low. (Homoptera, Cicadellidae) s lokha. Doklady Academy of Sciences of Tajik SSR 1964, 7(1); pp. 47—48. (=New species of the genus Macropsis Low. (Homoptera, Cicadellidae) from the Elaeagnus).

- Pripisnova, M.G., 1965. Vrednaya entomofauna tugaynoi drevesnoo-kustarnikovoy rastitelnosti Yuzhnogo Tadzhikistana; Tajik University: Dushanbe, USSR, 1965; pp. 1—118. (=Harmful entomofauna of tugai tree and shrub vegetation of southern Tajikistan).

- Kuznetsov, A.V. Nasaekomye i kleschi, povrzhdayuschie plodovye i dekorativnye nasazhdeniya Severnogo Pribalkhashiya, i biologocheskie osnovy meropriyatiy po boribe s nimi. Abstract of the dissertation on competition of a scientific degree of candidate of agricultural sciences, Kazakh State University, Alma-Ata, 1971, pp. 1—22. (=Insects and mites that damage fruit and ornamental plantings of the Northern Balkhash region, and the biological basis of measures to combat them).

- Kostin, I.A. Zhiki-dendrofagi Kazakhstana (koroedy, drovoseki, zlatki); Nauka: Alma-Ata, USSR, pp. 1—286. (=Dendrophagous beetles of Kazakhstan (bark beetles, Longhorn, buprestids).

- Yagdyev, A. Stvolovye vrediteli turangi v Turkmenii. Izvestiya Akademii Nauk Turkmenskoi SSR, seria biologicheskie nauki 1975, 6; pp. 60—64. (=Trunk pests of Turanga in Turkmenia).

- Yagdyev, A. Obzor nasekomykh-ksilofagov lesov Centralnogo Kopetdaga. Entomologicheskoe Obozrenie 1979, 58(4), pp. 776–781. (=A review of the xylophagous insects of the forests of the Central Kopetdag).

- Yagdyev, A. Vrediteli dekorativnykh rasteniy v gorodakh Turkmenistana. Izvestiya Akademii Nauk Turkmenskoi SSR, seria biologicheskie nauki 1987, 1; pp. 47–50. (=Pests of ornamental plants in towns of Turkmenistan). (in Russian).

- Asanova, R.B.; Iskakov, B.V. Vrednye i poleznye poluzhestkokrylye (Heteroptera) Kazakhstann (opredelitel); Kainar: Alma-Ata, USSR, 1977; pp. 1—204. (=Harmful and useful hemipterans (Heteroptera) of Kazakhstan (key table).

- Lopatin, I.K.; Kulenova, K.Z. Zhuki-listoedy (Coleoptera, Chrysomelidae) Kazakhstana: opredelitel; Nauka: Alma-Ata, 1986; pp. 1—199. (=Leaf beetles (Coleoptera, Chrysomelidae) of Kazakhstan: key table).

- Danzig, E.M., 1993. Fauna of Russia and adjoining states, suborder coccids (Coccinea), families Phoenicoccidae and Diaspididae; Nauka: Sanct-Petersburg, 1993; pp. 1—453.

- Ponomarenko, M.G. Trophic relationships of caterpillars of subfamily Dichomeridinae (Lepidoptera, Gelechiidae) of the fauna of Russia and adjacent countries. In Lecturing for the Memory of A.I. Kurenzov, Nauka: Leningrad, Russia, 1993; Issue 4, pp. 41—48.

- Ponomarenko, M.G., 1997. Catalogue of the subfamily Dichomeridinae (Lepidoptera, Gelechiidae) of the Asia. Far Eastern Entomologist 1997, 50, 1—67.

- Fedotova, Z.A. Gallitsy-fitofagi (Diptera, Cecidomyiidae) pustyn i gor Kazakhstana: morphologiya, biologiya, rasprostranenie, filogeniya i sistematika; Samara State Agricultiral Academy: Samara, Russia, 2000; pp. 1-803. (=Midges – phytophages (Diptera, Cecidomyiidae) of deserts and mountains of Kazakhstan: morphology, biology, distribution, phylogeny and systematics).

- Mityaev I.D. Fauna, ecology, and zoogeography of cicadas (Homoptera, Cicadinea) in Kazakhstan. Tethys Entomological Research 2002, 5, 3—168.

- Aitzhanova, M.O.; Kadyrbekov, R.Kh., 2006. To the fauna of aphids (Homoptera, Aphididae) of the tugai forests of the Karatal river basin. Vestnik KazNU,seria biological 2006, 2(28), 82—87.

- Kadyrbekov, R.Kh.; Aitzhanova, M.O. To the fauna of aphids (Homoptera, Aphididae) of the tugai forests between the rivers Aksu and Lepsy. Izvestiya NAS RK, series biological and medical 2006, 3, 7—13.

- Jashenko, R.; Mityaev, I.; DeLoach C.J. 2007 Potential agents for Russian biocontrol in USA. In Proceedings of the XII International Symposium on Biological Control of Weeds, Le Grand Motte, France, 22-27 April 2007, pp. 249.

- Jashenko, R.V. Annotated list of species of the family Margarodidae (Homoptera, Coccinea) of Central Asia and Kazakhstan. Izvestiya NAS RK, series biological and medical 2007, 2, 3—10.

- Schaffner, U. Update on CABI‘s weed biocontrol program; CABI: Delémont, Switzerland, 2009; pp.1—27.

- Schaffner, U.; Hinz, H.L.; Cristofaro, M. Biological control of Russian olive, Elaeagnus angustifolia. Annual report 2007; CABI: Delémont, Switzerland, 2007; pp. 1—20.

- Schaffner, U.; Grözinger, F.; Cristofaro, M. Biological control of Russian olive, Elaeagnus angustifolia. Annual report 2007. CABI: Delémont, Switzerland, 2008; pp. 1—20.

- Schaffner, U.; Dingle, K.; Swart, C.; Cristofaro, M. Biological control of Russian olive, Elaeagnus angustifolia. Annual report 2011. CABI: Delémont, Switzerland, 2012; pp. 1—20.

- Schaffner, U.; Asadi G.; Chetverikov P.; Ghorbani R;, Khamraev A.; Petanović R.; Rajabov T.; Scott T.; Vidović B.; Cristofaro, M. Biological control of Russian olive, Elaeagnus angustifolia. Annual report 2013. CABI: Delémont, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 1—20.

- Bean, D.; Norton, A.; Jashenko, R.; Cristofaro, M.; Shaffner, U. Status of Russian olive biological control in North America. Ecological Restoration 2008, 26 (2), 105—107. [CrossRef]

- Weyl, P.; Schaffner, U.; Asadi, G.; Klötzli, J.; Vidović, B.; Petanović, R; Cristofaro, M. Biological control of Russian olive, Elaeagnus angustifolia. Annual Report 2016. CABI: Delémont, Switzerland, 2017, pp. 1—20.

- Weyl, P.; Closça, C.; Asad, G.; Vidović, B.; Petanović, R.; Marini, F.; Cristofaro, M. Biological control of Russian olive, Elaeagnus angustifolia. Annual Report 2018. CABI: Delémont, Switzerland, 2019, pp. 1—20.

- Fasulati, K.K. Polevoe izuchenie nazemnykh bespozvonochnykh; Vyshaya shkola: Moscow, USSR, 1961; pp. 1—304 (=Field study of terrestrial invertebrates); Higher School: Moscow, USSR, 1971; pp. 1—424.

- Loginova, M.M. New data on the fauna and biology of the Caucasian Psylloidea (Homoptera). In Trudy vsesoyuznogo entomologicheskogo obshchestva; Akademiya Nauk SSSR: Moscow, USSR, 1968, Issue 52; pp. 275—328.

- Loginova, M.M. Podotrjad Psyllinea. In: Opredelitel Nasekomykh Evropeiskoi Tchasti SSSR, part 1; Bei-Bienko, G. Ya.; Nauka: Moscow, Russia, 1964; pp. 437—482.

- Loginova M. M., 1978. New species of psyllids (Homoptera, Psylloidea). In Trudy Zoologicheskogo Instituta AN SSSR, Nauka: Leningrad, USSR, 1978; Issue 61, pp. 30—123.

- Baeva, V.G. 1985. Fauna of the Tajik SSR, Psyllids or jumping plant-lice (Homoptera, Psylloidea); Donish: Dushanbe, USSR, 1985; Issue 8, pp. 1—329.

- Gegechkori, F.M. Psyllids (Homoptera, Psуlloidea) of Caucasia; Metsniereba: Tbilisi, USSR, 1984; pp. 1—294.

- Klimaszewski, S. M.; Lodos, N. New informations about Jumping Plant Lice of Turkey (Homoptera: Psylloidea). Ege Üniversitesi Ziraat Fakültesi Dergisi [Turkish Journal of Agriculture and Forestry] 1977, 14(1), pp. 1—9.

- Burckhardt, D.; Önuçar, A. A review of Turkish jumping plant-lice (Homoptera, Psylloidea). Revue Suisse de Zoologie 1993, 100(3); pp. 547—574.

- Drohojowska, J.; Burckhardt, D. The jumping plant-lice (Hemiptera: Psylloidea) of Turkey: a checklist and new records. Turkish Journal of Zoology 2014, 38, pp. 1—10. [CrossRef]

- Burckhardt, D.; Lauterer, P. The jumping plant-lice of Iran (Homoptera, Psylloidea). Revue Suisse de Zoologie 1993, 100(4), pp. 829—898. [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, Z.; Mehrvar, A.; Lotfalizadeh, H.; Gharekhani, Gh. Comparative study of the superfamily Psylloidea in Iran and East-Azarbaijan. Iranian Journal of Entomological Research 2013, 5(3), pp. 183—193.

- Li, Fasheng. Psyllidomorpha of China (Insecta: Hemiptera). Huayu Nature Book Trade Co.Ltd: Beijing, China, 2011; part 1-2, pp. 1—1976.

- Kuznetsov, A.V. Lokhovoya listobloshka Trioza magnisetosa Log. (Homoptera, Triozidae) v Severnom Pribalkhashiye. Trudy of Kazakh State Agricultural Institute 1970, 13(1), pp. 62—70. (=Oleaster jumping plant-lice Trioza magnisetosa Log. (Homoptera, Triozidae) in North Balkhash Lake area).

- Kuznetsov, A.V. Morfologiya lokhovoy listobloshki (Trioza magnisetosa Log.), povrezhdayuschey lokh uzkolistniy v Severnom Pribalkhashie. In Aktualnye voprosy ozeleneniya i ustoichivosti derevesnykh i kustarnikovykh porod v Centralnom Kazakhstane [Actual issues of greening and sustainability of tree and shrub species in Central Kazakhstan]; Kainar: Alma-Ata, USSR, 1975; pp. 148—157. (=Morphology of the oleaster jumping plant-lice (Trioza magnisetosa Log.), damaged Russian Olive in North Balkhash region).

- Khlebutina, L.G., 1982. Insects of the South and East of Kazakhstan, part 2, section 1, Psyllids of East Kazakhstan. In Report of the entomological laboratory of the Institute of Zoology of the Academy of Sciences of the Kazakh SSR, Institute of Zoology: Alma-Ata, 1982; pp. 4—45.

- Hodkinson, I. D. Life cycle variation and adaptation in jumping plant lice (Insecta: Hemiptera: Psylloidea): a global synthesis. Journal of Natural History 2009, 43(1), pp. 65—179. [CrossRef]

- Parfentiev, V.Ya. Vredityeli Urdinskikh lesnykh nasazhdeniy. In Trudy of Republican Station of Plant Protection (Kazakh branch of All-Union Lenin Academy of Agricultural Sciences), Academy of Sciences of Kazakh SSR: Alma-Ata, USSR, 1953; Issue I, pp. 59—61. (=Pests of Urda forest plantations).

- Kulenova, K.Z., 1968. Fauna i ekologicheskie osobennosti Zhukov-listoedov (Coleoptera, Chrysomelidae) yugo-vostoka Kazakhstana. In Trudy of the Institute of Zoology of the Academy of Sciences of the Kazakh SSR, Nauka: Alma-Ata, USSR, 1968; Issue 30, pp. 158—183. (=Fauna and ecological features of leaf beetles (Coleoptera, Chrysomelidae) South-East of Kazakhstan).

- Putshkov, V. G. Species of the genus Glaucopterum Wagner 1963 (Heteroptera, Miridae) of the Soviet Union fauna. Doklady Akademii Nauk Ukrainskoi SSR, Ser. B 1975, 11, pp. 1037—1042.

- Kerzhner, I.M. Novye i maloizvestnye vidy Heteroptera iz Mongolii i. Sopredelnikh rayonov SSSR. IV. Miridae, 1. In Nasekomye Mongolii [Insects of Mongolia); Nauka: Leningrad, USSR, 1984; Issue 9, pp. 35-72. (=New and little-known species of Heteroptera from Mongolia and adjacent regions of the USSR. IV. Miridae, 1).

- Vinokurov, N.N.; Dubatolov, V.V. Desert shield bug Brachynema germarii (Heteroptera: Pentatomidae) is found in the south of Eastern Siberia, Russia. Zoosystematica Rossica 2018, 27(1), pp. 146–149. [CrossRef]

- Yagdyev, A.; Tashlieva, A.O. Zhuki-vrediteli orekha i lokha v Turkmenii. In Ekologicheskoe i khozyaistvennoe znachenie nasekomykh Turkmenii; Ilim: Ashghabad, USSR, 1976; pp. 83–92. (=Beetle pests of walnut and oleaster in Turkmenia).

- Data sheets on quarantine pests. Aeolesthes sarta. In OEPP/EPPO Bulletin, 2005, Issue 35, pp. 387–389.

- Legalov, A.A.; Korotyaev, B.A. A new species of the genus Temnocerus Thunb. (Coleoptera: Rhynchitidae) from Kazakhstan. Baltic J. Coleopterol. 2006, 6 (2), pp. 125–127.

- Popescu-Gorj, A. Apotomis lutosana Kennel (Lepidoptera, Tortricidae) en Roumanie, espèce nouvelle pour la faune d’Europe. Travaux du Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle ’Grigore Antipa’ 1984, 25, pp. 237–238.

- Rikhter, V.A.; Durdyev, S.K. Tachinids (Diptera, Tachinidae) - parasites of Lepidoptera - orchard pests in Turkmenia. Vestnik Zoologii 1988, 1, pp. 62.

- Kuznetsov, V.I. Tortricidae. In: Keys to the Insects of the European Part of the USSR, IV Lepidoptera part 1, G.S. Medvedev, 1987; pp. 279-967.

- Bulyginskaya, M.A.; Akhmedov, A.M.; Dusmanov, I.E. Biological characteristics of the green tortricid Pandemis chondrillana H.-S. (Lepidoptera, Tortricidae) in the Penjikent district of Tajikistan. Entomologicheskoe Obozrenie 1994, 73(2), pp. 234–237.

- Skou, P. The geometroid moths of North Europe (Lepidoptera, Drepanidae and Geometridae). E.J.Brill/Scandinavian Science Press: Leiden-Copenhagen, Entomonograph, 1986, Issue 6, pp. 1–348.

- Forest pests on the territories of the former USSR. In: European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization, 2000, pp. 1–117. Available online: http://www.eppo.org/QUARANTINE/forestry_project/EPPOforestry_project.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2025).

| Months | ||||||||||||||||||

| IV | V | VI | VII | VIII | IX | X-XII-I-III | ||||||||||||

| Decades | Decades | Decades | Decades | Decades | Decades | |||||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Normal Spring | ||||||||||||||||||

|

3 Generation (Overwintered Adults) |

1 Generation (Adults) |

2 Generation (Adults) |

3 Generation (Overwintered Adults) | |||||||||||||||

| W | W | W | W | |||||||||||||||

| ♂ | ♂ | ♂ | ♂ | ♂ | ♂ | ♂ | ♂ | ♂ | ♂ | ♂ | ♂ | ♂ | ♂ | ♂ | ♂ | ♂ | ||

| ♀ | ♀ | ♀ | ♀ | ♀ | ♀ | ♀ | ♀ | ♀ | ♀ | ♀ | ♀ | ♀ | ♀ | ♀ | ♀ | ♀ | ||

| ◎ | ◎ | ◎ | ◎ | ◎ | ◎ | ◎ | ◎ | ◎ | ◎ | ◎ | ◎ | |||||||

| oo | oo | oo | oo | oo | oo | oo | oo | oo | ||||||||||

| L1 | L1 | L1 | L1 | L1 | L1 | |||||||||||||

| L2 | L2 | L2 | L2 | L2 | L2 | |||||||||||||

| L3 | L3 | L3 | L3 | L3 | L3 | |||||||||||||

| L4 | L4 | L4 | L4 | L4 | L4 | |||||||||||||

| L5 | L5 | L5 | L5 | L5 | L5 | |||||||||||||

| Months | ||||||||||||||||||

| IV | V | VI | VII | VIII | IX | X-XII-I-III | ||||||||||||

| Decades | Decades | Decades | Decades | Decades | Decades | |||||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Normal Spring | ||||||||||||||||||

| W | W | W | W | W | W | W | ||||||||||||

| ♂ | ♂ | ♂ | ♂ | ♂ | ♂ | ♂ | ||||||||||||

| ♀ | ♀ | ♀ | ♀ | ♀ | ♀ | ♀ | ||||||||||||

| ◎ | ◎ | ◎ | ◎ | |||||||||||||||

| oo | oo | oo | oo | |||||||||||||||

| L1 | L1 | L1 | L1 | |||||||||||||||

| L2 | L2 | L2 | L2 | |||||||||||||||

| L3 | L3 | L3 | L3 | |||||||||||||||

| P | P | P | P | |||||||||||||||

| Earlier Warm Spring | ||||||||||||||||||

| W | W | W | W | W | ||||||||||||||

| ♂ | ♂ | ♂ | ♂ | ♂ | ♂ | ♂ | ♂ | ♂ | ♂ | ♂ | ||||||||

| ♀ | ♀ | ♀ | ♀ | ♀ | ♀ | ♀ | ♀ | ♀ | ♀ | ♀ | ||||||||

| ◎ | ◎ | ◎ | ◎ | |||||||||||||||

| oo | oo | oo | oo | oo | ||||||||||||||

| L1 | L1 | L1 | L1 | L1 | L1 | |||||||||||||

| L2 | L2 | L2 | L2 | L2 | L2 | |||||||||||||

| L3 | L3 | L3 | L3 | L3 | L3 | |||||||||||||

| P | P | P | P | P | ||||||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).