Introduction

The age of Earth is around 4.56 billion years (Hazen, 2010). The theory of continental drift first proposed by Alfred Wegener suggests that the land masses on Earth are continually in motion (Wegener, 1912).

During the Permian period of 250 million years ago the Earth had a single continent, Pangea surrounded by a massive ocean Panthalassa. The Pangea covered a single hemisphere and extended from pole to pole. The Permian-Triassic extinction event, also known as the Great Dying, took place around 252 million years ago and was one of the most significant events in the history of our planet. It represents the divide between the Palaeozoic and the Mesozoic eras. The Triassic Period (252-201 million years ago) began after Earth's worst-ever extinction event devastated life (Wopfner and Jin, 2009; Wang et al. 2021).

In the Triassic period, spanning 250-200 million years ago, Pangea began to break apart into two major landmasses known as Laurasia and Gondwana, separated by the Tethys Sea. Laurasia was made of the present-day continents of North America, Europe, and Asia. Gondwana was made of the present-day continents of Africa, Antarctica, Australia, South America and the Indian subcontinent. The Jurassic period, around 145 million years ago, saw further changes in the arrangement of continents. Finally, during the Cretaceous period, about 65 million years ago, the continents continued to shift and evolve (Wopfner and Jin, 2009; Wang et al. 2021).

Approximately 120 million years ago, the Indian plate began to break away from Gondwana. Over millions of years, the Indian plate drifted steadily northward, gradually approaching the Eurasian plate. When these two colossal plates finally collided, the impact was transformative. This monumental tectonic clash led to the dramatic uplift of the Himalayas and the formation of the Tibetan Plateau. The collision not only created one of the world’s most formidable mountain ranges but also instigated significant geological shifts (Kumar et al. 2007; Chatterjee et al. 2013).

As the Indian plate continued its northward journey, it contributed to the closure of the Tethys Ocean, an ancient ocean that had once separated Laurasia from Gondwana. The closure of the Tethys Ocean led to the formation of new oceanic basins, including the Indian Ocean, which began to take shape as the landmasses realigned. These tectonic processes, which began with the breakup of Gondwana and the subsequent drift of the Indian plate, have been instrumental in shaping the Earth’s current continental arrangement. The relentless movement of these plates has not only redefined the geography of the continents but also played a crucial role in the formation of diverse geological features and oceanic systems that characterize our planet today (Wang et al. 2002).

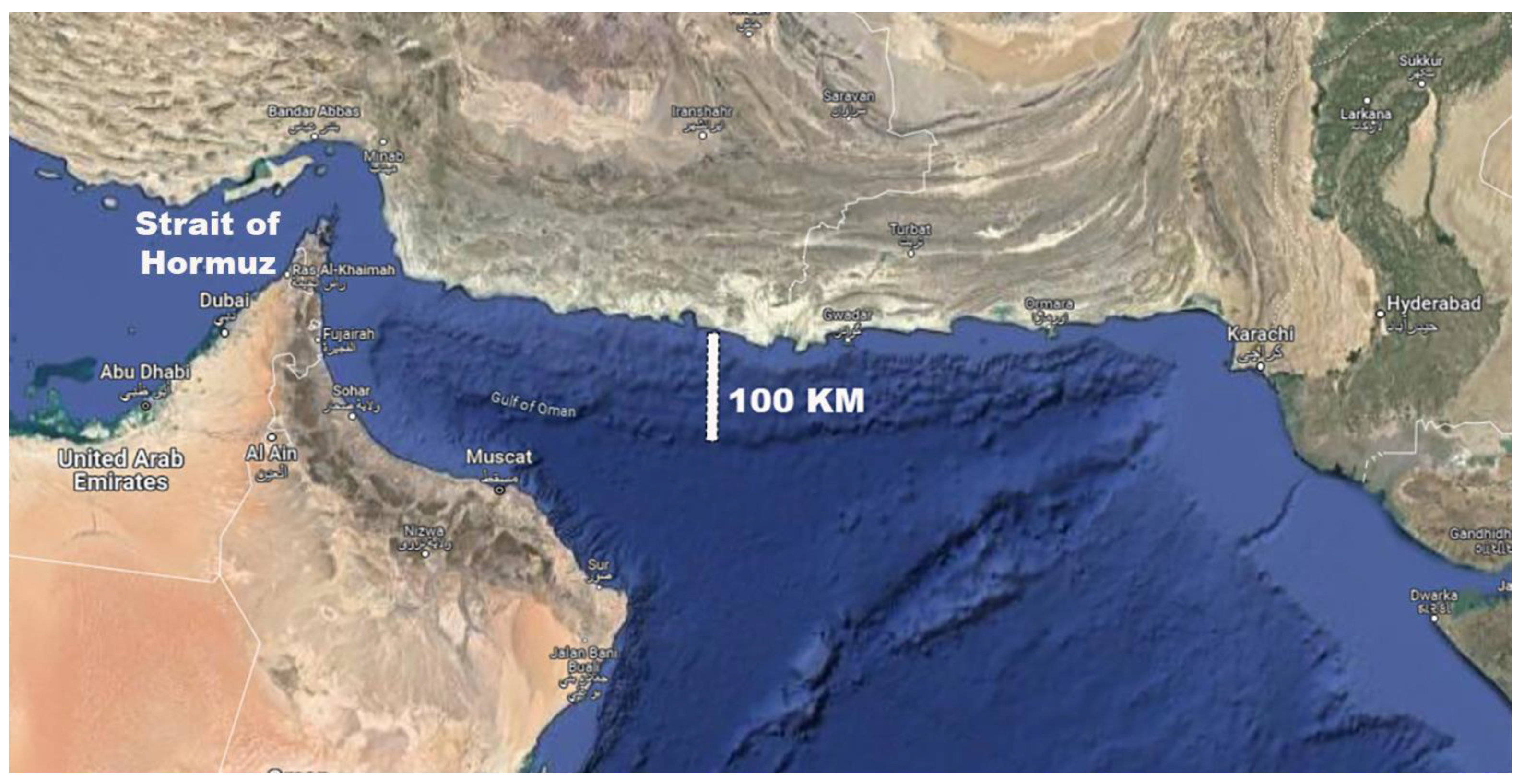

The convergence of the Indian plate with the Eurasian plate resulted in the formation of some of the world's most significant geological features, including the Himalayan Mountain range and the expansive Tibetan Plateau (Liu et al. 2023). The forceful collision of the Indian plate with the Eurasian plate also led to the fracturing of the Musandam Mountains in the Arabian Peninsula that contributed to the eventual formation of the Strait of Hormuz.

This paper focuses on the formation of the Strait of Hormuz, exploring how the tectonic forces associated with the Indian plate's movement contributed to the development of this crucial maritime chokepoint. The Strait of Hormuz, a vital conduit between the Persian Gulf and the Arabian Sea, plays a significant role in global maritime trade and has been shaped by the intricate and dynamic processes of plate tectonics.

Materials and Methods

The study relies on data derived from the global map available on Google Maps. All measurements were conducted using the suite of tools provided within the platform, ensuring accuracy and consistency. The mapping tools utilized include features such as distance measurement, area calculation, and geolocation pinpointing, which are integral for detailed spatial analysis.

These tools allowed the researchers to determine precise distances, boundaries, and geographic coordinates necessary for the study. By leveraging Google Maps' satellite imagery, and terrain views, the study was able to incorporate a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the geographic variables involved.

Moreover, the accessibility and user-friendly nature of the platform enabled us to conduct repeated measurements and cross-verifications to minimize potential errors. This methodological approach ensures the reliability and validity of the data collected from Google Maps.

Results

Formation of Western Indian Mountain Ranges

Based on the global map, we could speculate that the collision of the western flank of the Indian plate with the Eurasian plate triggered a series of geological events that significantly shaped the region's topography. The mountains of the Eurasian plate near Brar, adjacent to the Indian plate, may have undergone significant transformation during the collision between these two major tectonic plates. This monumental geological event, which began millions of years ago, initiated a series of intense compressional forces that profoundly altered the landscape. As the Indian plate pushed northward into the Eurasian plate, the immense pressure and stress caused the Earth's crust to fold, fracture, and uplift, resulting in the dramatic elevation of mountain ranges.

Near Brar, these transformative processes would have included the formation of complex fold structures, thrust faults, and the uplift of metamorphic rocks to the surface. The collision likely resulted in the reconfiguration of pre-existing geological formations, creating a highly varied and rugged terrain. This area would have experienced significant seismic activity, contributing to the ongoing mountain-building processes that continue to shape the region today.

The tectonic activity resulting from the collision of the Indian and Eurasian plates led to the formation of the Sulaiman Fold, a prominent mountain range distinguished by its intricate fold structures (

Figure 3). In contrast to the Eastern Indian Mountains, which have been more susceptible to erosion due to tropical wet conditions, the mountains in the western region have remained remarkably well-preserved. This preservation is largely due to the arid climate that dominates the area, which has played a crucial role in maintaining these geological formations' distinctive features over millions of years.

The southernmost point of the Western Indica Mountain Range is Cape Monze. This geographical landmark, also known as Ras Muari, marks the transition from the rugged terrain of the Central Makran Range to the coastal plains that extend towards the Arabian Sea. Cape Monze is a significant feature not only for its geographical importance but also for its unique ecological and geological characteristics. The cape's cliffs and rocky outcrops provide a striking contrast to the surrounding landscapes, and the area is known for its diverse marine life and rich biodiversity.

At the junction of Indian and Eurasian plates is the Las Bela triangular plain, encompassing the Miani Hor lagoon (Figure 3). This plain, located in the southwestern part of Pakistan's Balochistan province, represents a dynamic interplay of tectonic forces that have shaped the landscape over millions of years. The collision and subsequent interaction between the Indian and Eurasian plates have resulted in complex geological processes that contributed to the formation of the Las Bela plain. The convergence of these plates caused substantial deformation of the Earth's crust, leading to the creation of this unique triangular-shaped plain. The area is characterized by a mixture of alluvial deposits, coastal features, and sedimentary formations that reflect the region's tectonic and climatic history.

Miani Hor, a coastal lagoon within the Las Bela plain, adds to the area's ecological and geological importance. This lagoon is a vital habitat for diverse marine and bird life and serves as an essential site for local fisheries. The interaction between marine processes and tectonic activity has shaped Miani Hor's coastline, creating a distinctive environment where the land meets the Arabian Sea.

Discussion

Earth stands uniquely among its planetary peers within our solar system as the sole rocky planet characterized by active plate tectonics. This dynamic geological phenomenon involves the lithospheric plates continually shifting, forging a crucial connection between the Earth's deep interior and its surface reservoirs. Consequently, the traces of plate tectonics leave an indelible mark in the geological record through various processes such as rifting, collision events, and subduction zones. These geological activities not only shape the Earth's surface but also play a pivotal role in the planet's evolution and the distribution of its geological resources over millennia (Palin et al. 2020).

Convection currents within the Earth's mantle play a crucial role in driving the movement of continents and the deformation of the Earth's crust. These currents are generated by the heat produced from the decay of radioactive elements within the mantle. This heat causes material in the mantle to rise as it warms and to sink as it cools, creating a cyclical flow. This convective motion exerts enough force to shift and maneuver the Earth's lithospheric plates, resulting in the gradual and ongoing drift of continents. As the tectonic plates interact at their boundaries, they trigger various geological phenomena such as earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, and the formation of mountain ranges (Holmes, 1931). This theory has provided a cohesive framework for understanding these dynamic processes and represents a significant breakthrough in geological science. It is acknowledged as a fundamental element of Earth’s dynamic system, fundamentally influencing the planet's surface and its geological activity across the globe.

More than 167 million years ago, India was an integral part of the vast supercontinent known as Gondwana, spanning much of the Southern Hemisphere. Approximately 120 million years ago, India began its gradual separation from Gondwana, initiating a slow northward journey at a leisurely pace of about 5 centimeters per year. This initial movement set the stage for a remarkable geological saga that would unfold over millions of years. Around 80 million years ago, India's trajectory underwent a dramatic acceleration, surging northward at a staggering rate of about 15 centimeters per year—twice as fast as the swiftest contemporary tectonic drift. This rapid movement was catalyzed by the dynamic interaction of tectonic plates deep within the Earth's mantle. Specifically, India was propelled northward by the combined forces of two subduction zones—regions where one tectonic plate plunges beneath another, dragging connected landmasses along with it (Chatterjee et al. 2013; Gibbons et al. 2015; Jagoutz et al. 2015).

The convergence of these two subduction zones provided a dual pulling force, effectively doubling India's migration speed. This extraordinary pace ultimately led to the momentous collision between the Indian plate and the Eurasian plate approximately 50 million years ago. The impact of this collision reshaped the Earth's surface, giving rise to the Himalayan mountain range, whose towering peaks stand as a testament to the colossal forces at play in our planet's geological history. The formation of the Himalayas and the Tibetan plateau was not merely a geological event; it profoundly influenced global climate patterns, ocean currents, and the distribution of life across continents. The uplift of immense sedimentary layers from the ancient Tethys Sea, now towering several miles above sea level, further underscores the monumental scale of these geological processes (Chatterjee et al. 2013; Gibbons et al. 2015).

While the Himalayas, located to the north of the Indian plate, have been extensively studied and are well understood, the mountain ranges situated to the west and east of the Indian plate remain less thoroughly explored. The intricate geological processes and tectonic interactions that have shaped these lesser-studied regions are not yet fully elucidated. Understanding these western and eastern mountain ranges and is crucial for a comprehensive grasp of the broader tectonic and geological framework of the Indian plate. Further investigation could reveal important insights into the interactions between the Indian plate and its neighboring tectonic regions, contributing to our overall understanding of mountain building processes and the dynamic nature of Earth's lithosphere.

At present, the Indian plate is advancing in a north-eastern direction at an approximate rate of 5 centimeters per year (Gao et al., 2022). This movement is a significant component of the Earth's tectonic dynamics and has profound implications for the geological processes occurring in the region. It is plausible to hypothesize that in the past, the Indian plate was moving in a north-western direction, as evidenced by the orientation and formation of mountain ranges in the northern and western regions of the plate. This historical movement likely played a significant role in shaping the geological features observed today. As the Indian plate progressed north-westward, it exerted considerable pressure on the surrounding regions, contributing to the uplift and formation of the prominent mountain ranges found in these areas. This tectonic activity also had a substantial impact on the continental shelf in South-West Asia. Over time, the movement of the Indian plate led to the gradual exposure and modification of this continental shelf, further influencing the region's geological landscape.

Current topographical maps reveal that the upper continental crust has migrated approximately 100 kilometers inland in response to the relentless movement of the Indian plate. This shift underscores the dynamic nature of tectonic processes and their long-term effects on the Earth's surface. The migration of the crust is a testament to the ongoing tectonic forces that continue to reshape the landscape, reflecting the historical and ongoing interactions between the Indian plate and its neighboring geological structures. The historical rapid movement of the Indian plate, relative to the slower motion of the Arabian plate, contributed to the fracture of the Musandam Mountains eventually leading to the formation of the Strait of Hormuz. This contrast in plate velocities played a crucial role in opening this important waterway, further illustrating the profound effects of tectonic activity on regional geological features.

Though the Strait of Hormuz formation is geologically old, the formation of Persian Gulf, a shallow epicontinental sea located between the Arabian Peninsula and southwestern Iran is geologically recent. Approximately 20,000 years ago, during the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), much of the Earth's water was locked in vast ice sheets, causing global sea levels to be significantly lower than today—by as much as 120 to 130 meters (Clark et al. 2009). As a result, the area that now forms the Persian Gulf was predominantly a dry, low-lying basin. At its lowest point, the Persian Gulf region was not submerged but instead served as an expansive arid plain. This plain was fed by the confluence of major rivers such as the Tigris, Euphrates, and Karun. These rivers created a fertile delta-like environment that supported diverse ecosystems and potentially early human settlements. Archaeological and geological evidence suggests that this area may have been a migration corridor or even a cradle for some human populations before being inundated.

Around 15,000 years ago, as the Earth's climate began to warm at the end of the Pleistocene epoch, the glacial ice sheets started melting. This melting triggered a significant and gradual rise in global sea levels, a process known as the Holocene transgression. Over the next several millennia, rising waters from the Indian Ocean breached the Strait of Hormuz, flooding the low-lying basin that is now the Persian Gulf. By approximately 6,000 to 7,000 years ago, the sea level stabilized near its current position, forming the gulf as we know it today (Hosseinyar et al. 2021).

The Persian Gulf remains a vital ecological and economic zone. Its geological history has contributed to the formation of extensive hydrocarbon reserves, making it one of the richest oil and gas regions in the world. Understanding the processes that shaped the Persian Gulf offers valuable insights into past climate changes and serves as a reference for studying modern sea level rise and its potential impacts on low-lying coastal regions globally.

Overall, our study reveals that the rapid movement of the Indian plate has significantly influenced the formation of several major geological features. This dynamic tectonic activity not only gave rise to the Himalayas and the Tibetan Plateau but also contributed to the development of the Western and Eastern Mountain ranges of the Indian subcontinent. Additionally, the plate's rapid motion played a crucial role in the fracturing the Musandam Mountains and the opening of the Strait of Hormuz. Detailed geological fieldwork and chemical analyses will provide more accurate data to further refine our understanding of these processes.

Data Availability

All the data is published in the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no competing interest.

References

- Advokaat EL, van Hinsbergen DJJ (2024). Finding Argoland: Reconstructing a microcontinental archipelago from the SE Asian accretionary orogen. Gondwana Research. Gondwana Research 128: 161-263.

- Chatterjee S, Goswami A, Scotese CR. (2013). The longest voyage: Tectonic, magmatic, and paleoclimatic evolution of the Indian plate during its northward flight from Gondwana to Asia. Gondwana Research 23: 238-267.

- Clark PU, Dyke SA, Shakun DJ, et al. (2009). The last glacial maximum. Science 325: 710-714.

- Gao Y, Yang J, Zheng Y. (2022). Eastward subduction of the Indian plate beneath the Indo-Myanmese arc revealed by teleseismic P-wave tomography. Earthquake Science 35:243-262.

- Gibbons AD, Zahirovic S, Müller RD, Whittaker JM, Yatheesh V. (2015). A tectonic model reconciling evidence for the collisions between India, Eurasia and intra-oceanic arcs of the central-eastern Tethys. Gondwana Research 28: 451-492.

- Hazen RM. (2010). How Old is Earth, and How Do We Know? Evolution: Education and Outreach 3:198–205.

- Holmes, A., 1931. Radioactivity and Earth movements. Trans. Geol. Soc. Glasg. 18, 559–606.

- Hosseinyar, G, Behbahani R, Moussavi-Harami R, Lak R, Kuijpers A. (2021). Holocene sea-level changes of the Persian Gulf. Quaternary International 571: 26-45.

- Jagoutz, O., Royden, L., Holt, A. et al. (2015). Anomalously fast convergence of India and Eurasia caused by double subduction. Nature Geosci 8: 475–478.

- Kumar P, Yuan X, Kumar MR, Kind R, Li X, Chadha RK. (2007). The rapid drift of the Indian tectonic plate. Nature 449: 894-7.

- Liu, L., Liu, L., Morgan, J.P. et al. (2023). New constraints on Cenozoic subduction between India and Tibet. Nat Commun 14, 1963.

- Palin RM, Santosh M, Cao W, Li SS, Hernandez-Uribe D, Parsons A. (2020). Secular change and the onset of plate tectonics on Earth. Earth-Science Reviews 207: 103172.

- Wang C, Li X, Hu X, Jansa LF. (2002). Latest marine horizon north of Qomolangma (Mt Everest): implications for closure of Tethys seaway and collision tectonics. Terra Nova 14: 114–120.

- Wang C, Mitchell RN, Murphy JB, Peng P, Spencer CJ. (2021). The role of megacontinents in the supercontinent cycle. Geology 49 (4): 402–406.

- Wegener, A (1912). Die Entstehung der Kontinente. Dr. A. Petermanns Mitteilungen aus Justus Perthes' Geographischer Anstalt. v. 58, pp. 185-195, 253-256, 305-309.

- Wopfner H, Jin X.C. (2009). Pangea Megasequences of Tethyan Gondwana-margin reflect global changes of climate and tectonism in Late Palaeozoic and Early Triassic times—A review. Palaeoworld 18: 169-192.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).