1. Introduction

Dark matter and dark energy are the two major puzzles in cosmology today[

1]. Dark energy is proposed to explain why the universe is accelerating, and dark matter is proposed to solve the abnormal rotation curve of disk galaxies. In the standard cosmological model,

Λ Cold Dark Matter (

ΛCDM), the component of dark energy is about 70%, the component of dark matter is about 25%, and the other component we can see is barely about 5%[

2]. Although the standard cosmological model is relatively successful and accepted by most physicists, it still has some unresolved problems, such as the fine-tuning problem and the origin problem of dark energy[

3]. And for dark matter, people are still not sure what the component it is[

4], since none of the particles described or predicted by the Standard particle Model meet the properties of dark matter. And more importantly, the dark matter have not been detected by experiments so far. It is in this complex context that various alternative models on Dark Energy and Dark Matter have been proposed. And among these alternative models to Dark Matter, the well-known and famous model maybe the MOdified Newtonian Dynamics (MOND)[

5], which is first proposed by Milgrom in 1983. Milgrom postulates that at small accelerations the usual Newtonian dynamics break down and that the law of gravity needs to be modified. To date, MOND have been widely studied and it has been shown to successfully explain a large number of astrophysical observations, such as kinematics of galaxies[

6,

7], dynamics of wide binary stars[

8,

9], radial acceleration relation of galaxies[

10,

11], orbital velocity of interacting galaxy pairs[

12], early-universe galaxy and cluster formation[

13], and galaxy-scale gravitational lensing[

14,

15]. However, for alternative models to Dark Energy, they are still difficulty to distinguish, and so far no alternative model has stood out, but we notice an interesting model proposed in Ref. [

16], which argues that the cosmic fluid is not perfect but rather viscous and dissipative, thus introducing a viscous pressure proportional to the Hubble constant into the standard cosmological model. Although the origin of the viscous pressure is still debated, it shows that the bulk viscosity model fit the combined SNe Ia + CMB + BAO + H(z) data obviously better than the

ΛCDM model.

In this paper, inspired by the idea of introducing a dissipation term into the expansion equation describing the universe in Ref. [

16], we also try to introduce such a dissipation term into the rotational motion equation describing the galaxies, and then observe its effect on the rotational motion of galaxies. Surprisingly, we found a high degree of coincidence between the derived motion properties and those predicted by MOND. However, as we have known that, MOND is only an empirical model, not a fundamental theory[

14]. This seems to give us a window to glimpse the nature of MOND.

2. Newtonian Dynamics with Dissipation Term

In Ref. [

16], the author introduced a dissipation term into the expansion equation describing the universe, making the expansion and evolution equation describing the universe becomes

where

a denotes the scale factor of the universe,

ρm is the total matter density,

G is the gravitational constant,

Λ denotes the cosmological constant,

ζ denotes the introduced viscosity coefficient, which is positive.

In Ref. [

16], it shows that Equation (1) can fit the astrophysical observational data obviously better than the

ΛCDM model. Inspired by this, we also want to introduce such a dissipation term into the rotational motion equation describing the galaxies and studies what will happen, even if the physical basis of this dissipation term is unclear at present.

Similar to Equation (1), we also assume that there is a dissipation term in the rotational motion equation describing the galaxy that is proportional to the velocity, and that the corresponding viscosity coefficient is also positive just as which in Equation (1). Then, without considering relativistic effects, we can easily obtain the force equilibrium equations in the radial and circumferential directions of rotational motion

where

M denotes the center mass of the galaxy, (

r,

θ) denotes the coordinates of motion and here for simplicity we only consider the motion in a two-dimensional plane,

λ is the assumed viscosity coefficient. And the second formula of Equation (2) represents that the derivative of angular momentum corresponding to the rotational motion with respect to time is equal to the rotational torque.

One may notice that Equation (2) also implies an assumption that the dissipation force is related to the mass

m of the object in rotating motion, because in its first formula both sides of the equation cancel out the mass

m, which is also consistent with the idea in Ref. [

16]. In fact, Equation (2) is equivalent to introducing a dissipation potential

Ψ into the Newtonian dynamics

Now anyway, we can use Equation (2) to study the rotational motion of galaxies. First from the second formula of Equation (2) we can obtain

where (

θ0,

r0) is the initial condition. Then substituting Equation (4) into the first formula of Equation (2)

where

R=

r/

r0, and

.

The analytical solution of Equation (5) is difficult to obtain, but we can obtain its numerical solution. Now before we do that we can make a rough analysis about this equation. First of all, from the success of Newtonian dynamics we know that

λ must be a very small value. So if the gravitational field is strong, Equation (2) returns to the usual Newtonian dynamics. While if the gravitational field is very weak, that is,

≫

GM/

r2,

≫

, then the first formula of Equation (2) can be simplified as

The solution of Equation (6) is , combining which with Equation (4), we can obtain that , indicating that, when the gravitational field is very weak, the circumferential velocity of an object rotating around the center of the galaxy remains constant as the radius of its orbit increases, which is similar to the result predicted by MOND.

Since there is currently no clear physical basis to help us to determine the value of

λ, let us discuss the motion properties predicted by Equation (2) by arbitrarily setting the value of

λ and the initial condition of the equation. And because the above we have seen that the result derived from Equation (2) is similar to which predicted by MOND when the gravitational field is extremely weak, next we will discuss Equation (2) in terms of the formula form in MOND. And it is known that MOND's formula has the following form

where

gN denotes the gravitational acceleration,

a denotes the centripetal acceleration,

μ is an empirical or undetermined interpolation function, when

a/

a0≫1,

μ→1, when

a/

a0≪1,

μ→

a/

a0, and

a0≈1.2×10

-10 m/s

2 is a constant.

After a brief understanding of Equation (5), we can see that regardless of the value of

λ (

λ>0) and the initial condition of the equation,

v (=

) will eventually remain almost constant (here make it be

vultimate) over time. So here we can also define a physical quantity

A0 like MOND

Then, similar to MOND, the relationship between gravitational acceleration and centripetal acceleration corresponding to Equation (5) can be also written as

Now we will conduct numerical analysis on Equation (5), and

Table 1 shows the value of

A0 and

μ' corresponding to different

λ and initial conditions. We did not set units in the data in

Table 1, because it is not necessary. Whether there are units in the numerical analysis does not affect the obtained conclusions from Equation (5).

In

Table 1, the number group (1,6,7,8), (9,10,11,12), (13,14,15,16) and (19,20,21) corresponds to the same mass

M, that is

. And from these number group we can see that

A0 is only dependent on

M and

λ, not on the initial conditions (

v0,

r0), as long as the initial centripetal acceleration corresponding to the initial conditions is strong enough, which is an important step for Equation (2) yields the MOND. One might wonder why does it here say that as long as the initial centripetal acceleration is strong enough, it's because if the initial centripetal acceleration

a´0 is too small and

λ is relatively large, it will make

vultimate very close to

v0, and therefore

A0≈

a´0 according to Equation (8), which means that

A0 is dependent on

M or the initial conditions (

v0,

r0), almost not on

λ. In other words, if a large number of objects rotating around the center of the galaxy are initially in the strong gravitational potential region of the galaxy, and we assume that for this galaxy the value of

λ is a constant, then, regardless of which orbit these objects are initially in, they will all eventually reach the same rotational circumferential velocity under the action of dissipation potential (i.e. Equation (3)), and the fourth power of this ultimate rotational circumferential velocity (i.e.,

vultimate) is proportional to the central mass of the galaxy (i.e. Equation (8), which also known as the famous Tully-Fisher relation [

17,

18,

19]).

In

Table 1, from the number group (1,2,3,4,5) we can see that if we assume the value of

λ is a constant independent of the central mass of the galaxy, then, the larger the mass of a galaxy, the higher the value of

A0, which seems echo the conclusion in Ref. [

20].

In

Table 1, from the number group (1,9,13) and (6,14,19) we can see that for the same galaxy, the higher the assumed value of

λ, the higher the value of

A0.

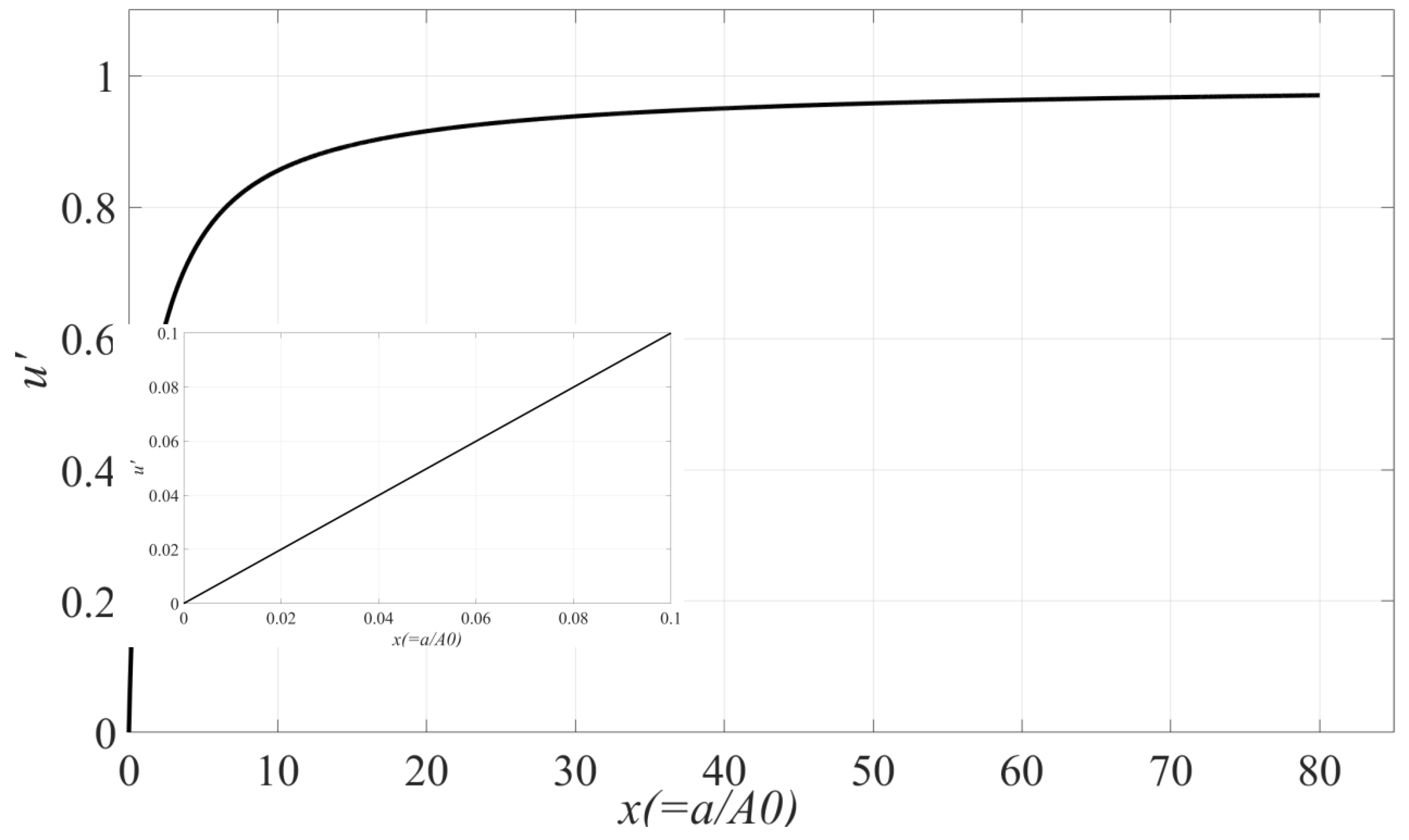

At last, the most important conclusion from

Table 1 and

Figure 1 is that, as long as the initial centripetal acceleration corresponding to the initial conditions is strong enough, whatever the assumed value of

λ is, whichever the initial orbit of the object rotating around the center of the galaxy is, or whatever the center mass of the galaxy is, their corresponding

μ', the interpolation function, are or are almost the same. And from

Figure 1 we can see that, when

x≪1,

μ'

→x, and when

x≫1,

μ'

→1, which is exactly what is required in the MOND’s empirical formula. Further, we find that the curve in

Figure 1 can be fitted as the following function

Unfortunately, we here cannot give a clear mathematical definition to the above statement “as long as the initial centripetal acceleration is strong enough”, mainly because for Equation (5) we cannot obtain its analytical solution, but its numerical solution.

In above, we only introduced a viscosity coefficient λ into the Newtonian dynamics and then we have almost completely derived all the formulas assumed in MOND, especially the interpolation function. However, we also obtained something different from MOND, that is, A0 does not need to be a constant, and the rotational galaxies are also gradually expanding over time, just like the universe is expanding.

Although the above conclusions are drawn based on the data in

Table 1, the amount of data in

Table 1 is far from enough. In fact, we privately expanded the amount of data in

Table 1, and found that the obtained conclusions remain the same, so we did not list these lengthy data. In addition, it should be stressed again that the absence of units for the data in

Table 1 does not affect the obtained conclusions from Equation (5) above.

3. Models Comparison

To compare observations with

ΛCDM, MOND and Equation (9), the Newtonian gravitational acceleration due to the ordinary matter (i.e., not including dark matter) must be separated from the total acceleration. Here we assume the acceleration due to baryons comes from the bulge and the disk (with no dark halo contribution), that is

where

r is the distance from the center of the galaxy,

vb and

vd are the rotational velocity due to the bulge and disk respectively.

In

ΛCDM, in addition to the ordinary matter, dark matter is considered, and the function of dark halo is usually expressed as [

21]

where

ρ0 and

h are the scale density and scale radius of the dark halo respectively. Then the mass of dark halo can be expressed as

The total acceleration is then

In MOND, there is no dark matter, and the relationship between gravitational acceleration and centripetal acceleration is expressed as Equation (7). Since the interpolation function are empirical, here we take the “simple” function [

22]

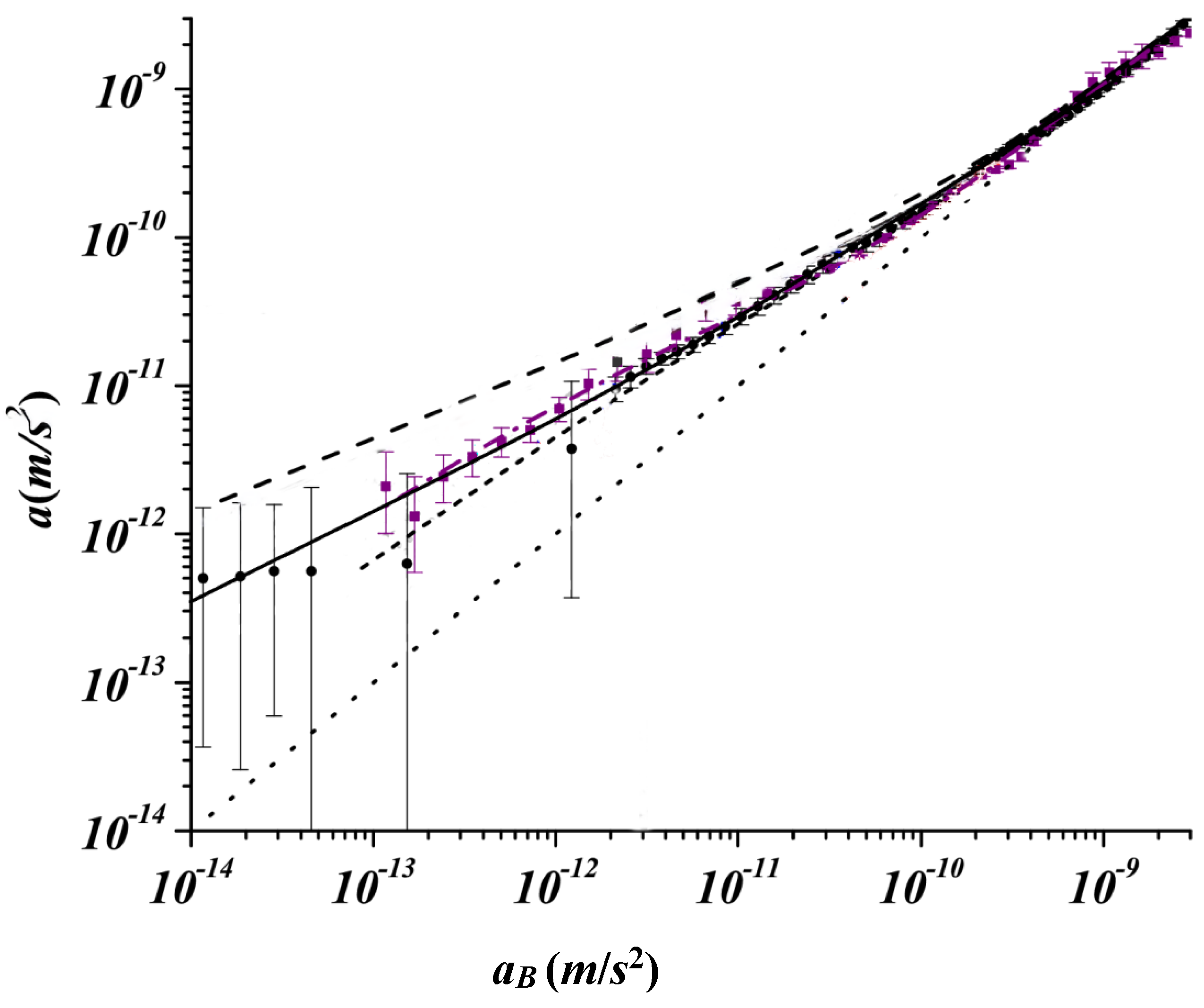

Then we can plot the centripetal acceleration vs. the gravitational acceleration due to baryons for the observation data in

Figure 2 [

23], and the fitting curves corresponding to various models are also plotted.

It should be note that the prediction in

Figure 2 assumes that the galaxies being observed are isolated.

Figure 2 shows that for smaller radii, i.e. large accelerations, MOND and Equation (9) do not significant deviate from expected

ΛCDM model galaxies, but that changes for lower accelerations. In addition, it indicates that the centripetal accelerations in M31 and Milky Way are smaller than the MOND prediction at lower

aB, but in line with the prediction of Equation (9). This is mainly because there are no free parameters in the prediction of radial acceleration relation (RAR) of galaxies in MOND, while in Equation (9),

A0 is a parameter that can vary with the mass of the galaxy, so we can adjust

A0 to fit the observation data in

Figure 2.

One may wonder whether dark matter was taken into account in Equation(9) when fitting the observation data in

Figure 2. The answer is that whether you consider it or not makes no mathematical difference to the fitting results. When dark matter exists, we assume that dark matter exists near the center of the galaxy (similar to MOND, our model does not need the dark matter halo to be carefully adjusted to meet the galaxy's asymptotically flat rotational velocity curve), which means that the coordinate

aB in

Figure 2 should be replaced by

gt. Since dark matter exists near the center of the galaxy, and the radial position corresponding to the maximum value of

aB in

Figure 2 is far away from the center of the galaxy, it is easy to prove that the

gt-axis can be obtained by adding a same value (which is determined by the mass of dark matter) to all values of the

aB-axis, or in other words, the whole shift of the

aB-axis to the right side can yield the

gt-axis. In Equation (9), the left side is just related to

gt, and the right side is just related to

a. In addition, from

Table 1 it has been pointed out that the function form of

μ' has nothing to do with the central mass of the galaxy (i.e.,

μ' is independent of

aB and

gt), so it can be easily proved that whether there is dark matter near the center of the galaxy does not affect the fitting result of Equation (9) mathematically. But physically, dark matter may be needed as its mass can help to adjust the value of

A0.

4. Summary

This paper, with no clear physical basis, just follows the idea in Ref. [

1], that is, introducing a viscosity coefficient into the expansion equation describing the universe, also introduces such a similar positive viscosity coefficient into the rotational motion describing the galaxies, and then studies what will happen. We were surprised to find that it yields all the formulas assumed in MOND, including a concrete interpolation function between the centripetal acceleration and the Newtonian acceleration, which however is known to be empirical in MOND.

But we also obtain something different from MOND. First, a0 is considered to be a constant in MOND, but we obtained that A0 (here it just to distinguish from a0 in MOND, and A0 and a0 have the same meaning in the equation) is not a constant but is related to the mass of the galaxy, and the more massive the galaxy, the greater the value of A0 if the value of λ is a constant. This characteristic can help it to fit the RAR data better than MOND. Second, the paper predicts that the rotational galaxies will expand radially over time at a extreme small expansion rate, just like the expansion of universe, so it predicts a “dynamic” galaxy rather than the “static” galaxy predicted by ΛCDM and MOND.

In many literature, such as Refs. [

24,

25,

26,

27], it is found that MOND can fit the observation data of rotational galaxies better than

ΛCDM, which is thought to be mainly attributed to the two extreme conditions (i.e., Newtonian and deep-MOND limits) in MOND, and has no or little relationship with the concrete form of the interpolation function in MOND. For these data, it is easy to know that the model in this paper can also fit them well (because the two extreme conditions can also be naturally derived from our model). In MOND, in order to fit these observational data, the mass-to-light ratio of the galaxy, which is the only free parameter in MOND [

28], have to be adjusted, and therefore the existence of dark matter must be excluded, because the presence of dark matter can affect the mass-to-light ratio. However, the model in this paper cannot rule out the existence of dark matter, one reason is that the mass of dark matter can help to adjust the value of

A0, and another reason is that the idea of this paper comes from Ref. [

2], which supports the existence of dark matter. However, unlike

ΛCDM, in our model, the asymptotically flat rotational velocity curve of the galaxy does not need to be achieved by the carefully adjustment of dark matter (if it exists), but can be just achieved under the viscous dynamics of the galaxy itself.

It is worth mentioning that the above we did not discuss the value of λ, mainly because the two extreme conditions in Equation (9) could fit many existing observational data well in the absence of the specific value of λ, and the model in this paper does not rule out the existence of dark matter, but what role which will play is still unclear. In addition, the lack of some detailed observational data also prevents us from doing so. But it is a task for future research.