1. Introduction

Determining the accurate pose of the camera is a fundamental problem in robot manipulations, as it provides the spatial transformation needed to map 3D world points to 2D image coordinates. The task involving camera pose estimation is essential for various applications, such as augmented reality [

1], 3D reconstruction [

2], SLAM [

3], and autonomous navigation [

4]. This becomes especially critical when robots operate in unstructured, fast-changing, and dynamic environments, performing tasks such as human-robot interaction, accident recognition and avoidance, and eye-in-hand visual servoing. In such scenarios, accurate camera pose estimation ensures that visual data is readily available for effective robotic control [

5].

A classic approach to estimating the pose of a calibrated camera is solving the Perspective-n-Point (PnP) problem [

6], which establishes a mathematical relationship between a set of n 3D points in the world and their corresponding 2D projections in an image. To uniquely determine the pose of a monocular camera in space, it is a Perspective-4-Point (P4P) problem, where exactly 4 known 3D points and their corresponding 2D image projections are used. Bujnak et al. [

7] generalize four solutions for P3P problem while giving a single unique solution existed for P4P problem in a fully calibrated camera scenario. To increase accuracy, modern PnP approaches considers more than three 2D-3D correspondences. Among PnP solutions, EPnP (Efficient PnP) method finds the optimal estimation of pose from a linear system that expresses each reference point as a weighted sum of four virtual control points [

8]. Another advanced approach, SQPnP (Sparse Quadratic PnP) formulates the problem as a sparse quadratic optimization, achieving enhanced accuracy by minimizing a sparse cost function [

9].

In recent years, many other methods have been developed to show improved accuracy than PnP based methods. For instance, Alkhatib et al. [

10] utilize Structure from Motion (SfM) to estimate a camera’s pose by extracting and matching key features across various images taken from different viewpoints to establish correspondences. Moreover, Wang et al. [

11] introduce visual odometry into camera’s pose estimations based on the movement between consecutive frames. In addition, recent advancements in deep learning have led to the development of models, such as Convolutional Neural Networks, specifically tailored for camera pose estimation [

12,

13,

14]. However, these advanced methods often come with significant computational costs, requiring multiple images from different perspectives for accurate estimation. In contrast, PnP-based approaches offer a balance between accuracy and efficiency, as they can estimate camera pose from a single image, making them highly suitable for real-time applications such as navigation and scene understanding.

In image-based visual servoing (IBVS) [

15], the primary goal is to control a robot’s motion using visual feedback. Accurate real-time camera pose estimation is crucial for making informed control decisions, particularly in eye-in-hand (EIH) configurations [

16,

17], where a camera is mounted directly on a robot manipulator. In this setup, robot motion directly induces camera motion, making precise pose estimation essential. Due to its computational efficiency, PnP-based approaches remain widely applied in real-world IBVS tasks [

18,

19,

20]. The PnP process begins by establishing correspondences between 3D feature points and their 2D projections in the camera image. The PnP algorithm then computes the camera pose from these correspondences, translating the geometric relationship into a format that the IBVS controller can use. By detecting spatial discrepancies between the current and desired camera poses, the robot can adjust its movements accordingly.

However, PnP-based IBVS presents challenges for visual control in robotics. One key issue is that IBVS often results in an overdetermined system, where the number of visual features exceeds the number of joint variables available for adjustment. For example, at least four 2D-3D correspondences are needed for a unique pose solution [

6], but a camera’s full six-degree-of-freedom (6-DOF) pose means that a 6-DOF robot may need to align itself with eight or more observed features. In traditional IBVS [

15], the interaction matrix (or image Jacobian) defines the relationship between feature changes and joint velocities. When the system is overdetermined, this matrix contains more constraints than joint variables, leading to redundant information. Research [

15] suggests that this redundancy may cause the camera to converge to local minima, failing to reach the desired pose. Although local asymptotic stability is always ensured in IBVS, global asymptotic stability cannot be guaranteed when the system is overdetermined.

Many studies have explored solutions to mitigate the local minimum problem in IBVS. One approach, proposed by Nicholas et al. [

21], introduces a switched control method, where the system alternates between different controllers to escape local minima and avoid singularities in the image Jacobian. Another strategy, developed by Chaumette et al. [

22], utilizes a 2-1/2-D visual servoing technique, which combines image-based and position-based features. This integration allows the camera to navigate around local minima during motion execution. Roque et al. [

23] implement a model predictive control (MPC) approach, optimizing the quadrotor’s trajectory to enhance robustness against local minima by predicting and adjusting control inputs in real time.

While these methods achieve significant improvements in most scenarios, they also introduce computational challenges compared to traditional IBVS. The switched control method requires different control strategies tailored to specific dynamics, increasing the complexity of the overall control architecture [

24]. The 2-1/2-D visual servoing method demands real-time processing of both visual and positional data, which can impose significant computational loads and limit performance in dynamic environments [

25]. MPC approaches introduce additional computational overhead by requiring complex optimization at every time step, making real-time implementation costly [

26].

In this paper, we focus on the PnP framework for determining and controlling the pose of a stereo camera within an image-based visual servoing (IBVS) architecture. In traditional IBVS, depth information between objects and the image plane is crucial for developing the interaction matrix. However, with a monocular camera, depth can only be estimated or approximated using various algorithms [

15], and inaccurate depth estimation may lead to system instability. In contrast, a stereo camera system can directly measure depth through disparity between two image planes, enhancing system stability.

A key novelty of this paper is providing a systematic proof that stereo camera pose determination in IBVS can be formulated as a P3P (Perspective-3-Point) problem, which, to the best of our knowledge, has not been explored in previous research. Since three corresponding points, totaling nine coordinates, are used to control the six DoFs camera pose, the IBVS control system for a stereo camera is overdetermined, leading to the potential issue of local minima during control maneuvers. While existing approaches can effectively address local minima, they often introduce excessive computational overhead, making them impractical for high-speed real-world applications.

To address this challenge, we propose a feedforward-feedback control architecture. The feedback component follows a cascaded control loop based on the traditional IBVS framework [

15], where the inner loop handles robot joint rotation, and the outer loop generates joint angle targets based on visual data. One key improvement in this work is the incorporation of both kinematics and dynamics during the model development stage. Enhancing model fidelity in the control design improves pose estimation precision and enhances system stability, particularly for high-speed tasks. Both control loops are designed using Youla parameterization [

27], a robust control technique that enhances resistance to external disturbances. The feedforward controller takes target joint configurations, which are associated with the desired camera pose as inputs, ensuring a fast system response while avoiding local minima traps. Simulation results presented in this paper demonstrate that the proposed control system effectively moves the stereo camera to its desired pose accurately and efficiently, making it well-suited for high-speed robotic applications.

2. System Configuration

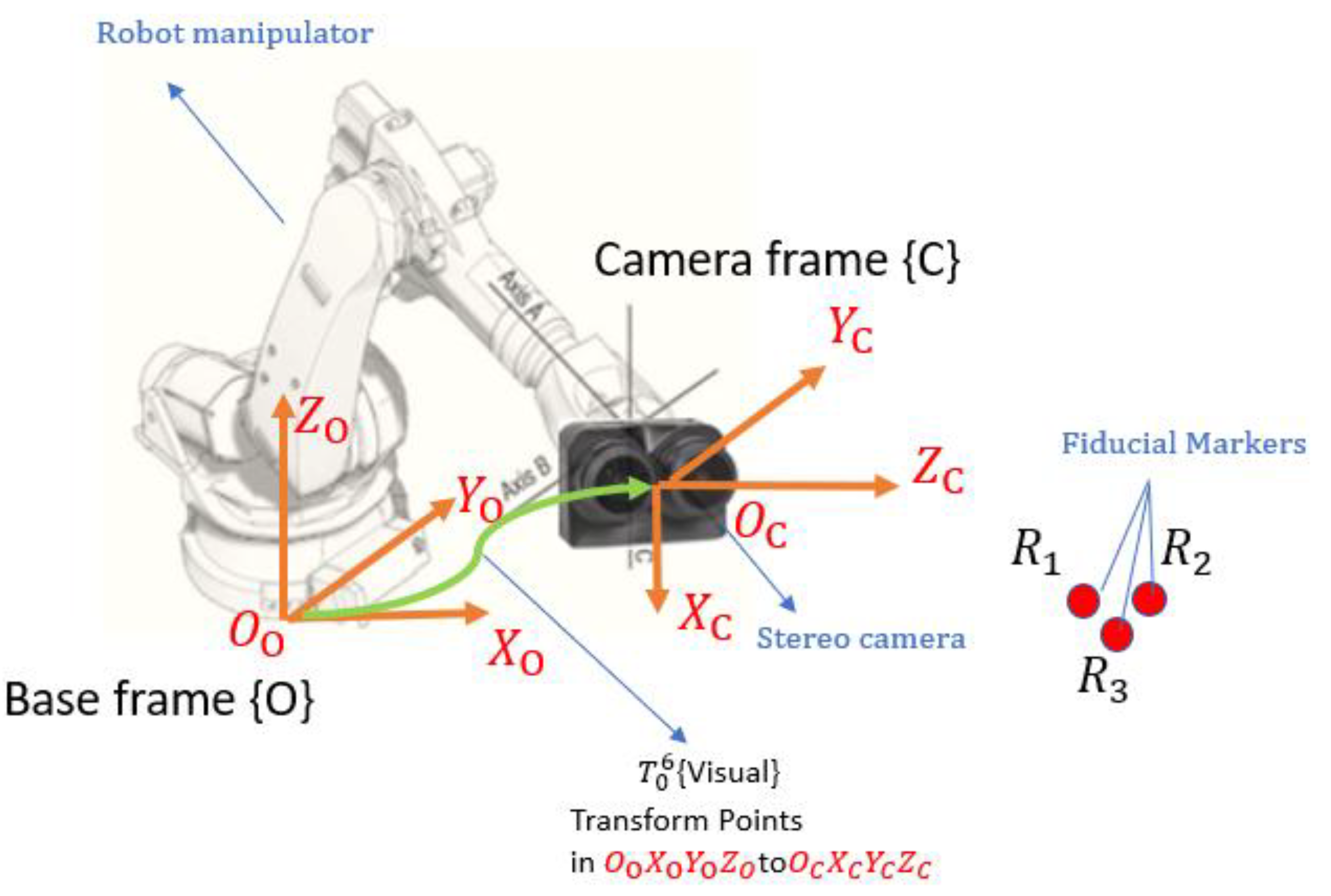

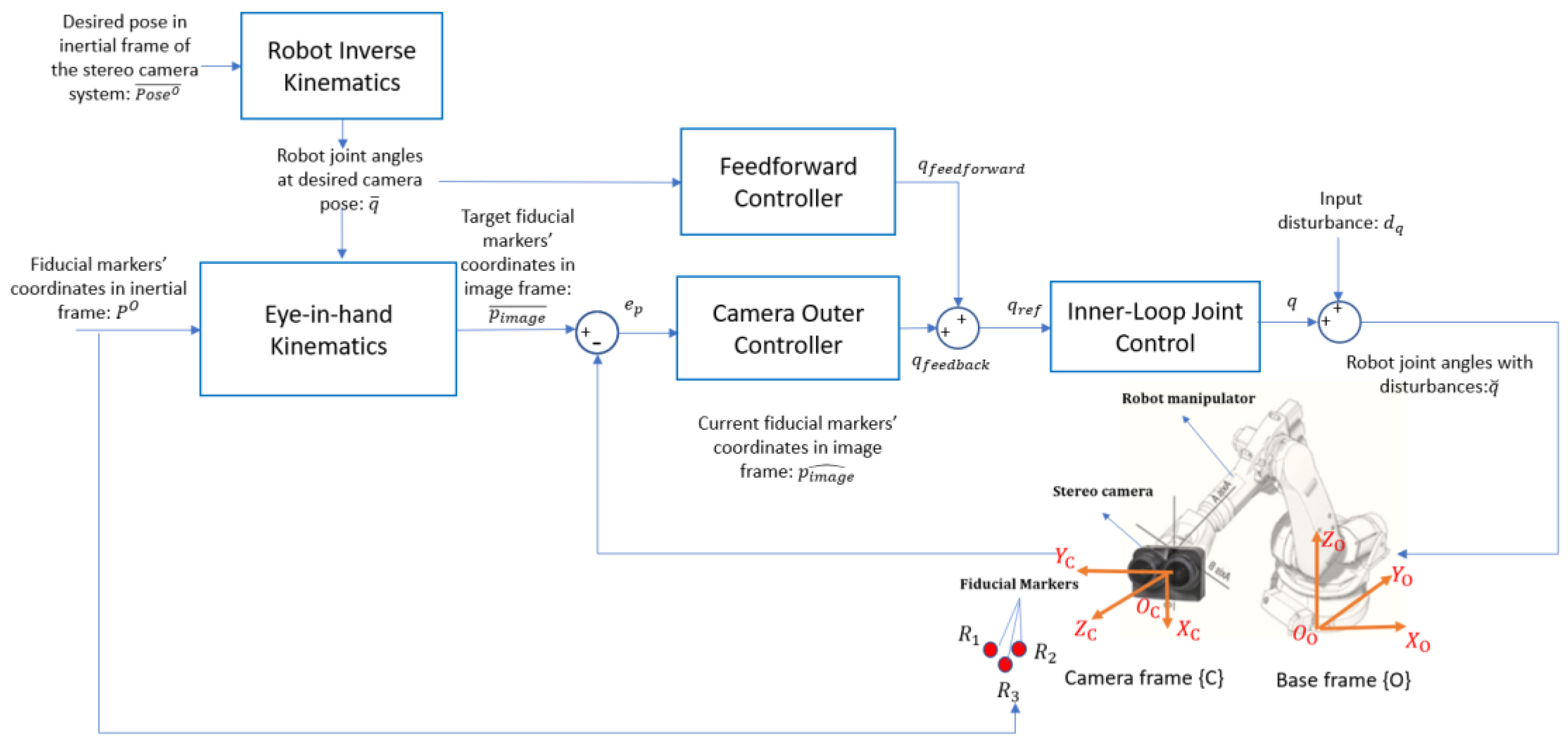

An eye-in-hand robotic system has been developed to precisely control the pose of a stereo camera system, as illustrated in

Figure 1. The robotic manipulator is equipped with six revolute joints, allowing unrestricted movement of the camera across six degrees of freedom (DoFs)—three for positioning and three for orientation. Assume a set of fiducial markers is placed in the workspace, with their coordinates fixed and predefined in an inertial frame. Utilizing the Hough transform [

28] in computer vision, these markers can be detected and localized by identifying their centers in images captured by the stereo camera system. The control system within the robotic manipulator aligns the camera to its desired pose by matching the detected 2D features in the current frame with target 2D features. Throughout this process, it is assumed that all fiducial markers remain within the camera’s field of view. As depicted in

Figure 1, multiple Cartesian coordinate systems are illustrated. The base frame {O} serves as an inertial reference fixed to the bottom of the robot manipulator, while the camera frame {C} is a body-fixed frame attached to the robot’s end-effector.

3. Proof of P3P for the Stereo Camera System

Given its intrinsic parameters and a set of n correspondences between its 3D points and 2D projections to determine the camera’s pose is known as perspective-n-point (PnP) problem. This well-known work [

7] has proved that at least four correspondences are required to uniquely determine the pose of a monocular camera, a situation referred to as the P4P problem.

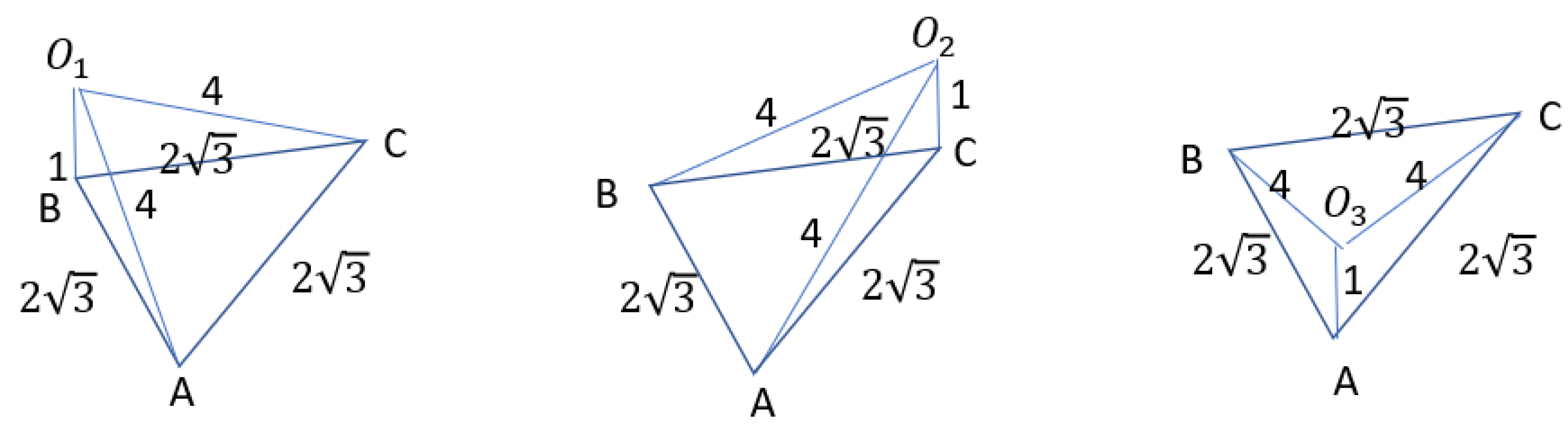

To illustrate, consider the P3P case for a monocular camera. Let points A, B, and C exist in space, with , and representing different perspective centers. The angles ∠ AOB, ∠ AOC and ∠ BOC remain the same across all three perspectives. Given a fixed focal length, the image coordinates of points A, B, and C will be identical when observed from these three perspectives. In other words, it is impossible to uniquely identify the camera’s pose based solely on the image coordinates of three points.

Figure 2.

P3P case of a monocular camera.

Figure 2.

P3P case of a monocular camera.

The PnP problem with a stereo camera has not been thoroughly addressed in prior research. A stereo camera can detect three image coordinates of a 3D point in space. This paper proposes that a complete solution to the PnP problem for a stereo camera can be framed as a P3P problem. Below is the complete proof of this proposition.

Proof:

For a stereo system, if all intrinsic parameters are fixed and given, we can readily compute the 3D coordinates of an object point given the image coordinates of that point. This provides a unique mapping from the image coordinates of a point to its corresponding 3D coordinates in a Cartesian frame. The orientation and position of the camera system uniquely define the origin and axis orientations of this Cartesian coordinate system in space. Consequently, PnP problem can be framed as follows: given n points with their 3D coordinates measured in an unknown Cartesian coordinate system in space, what is the minimum number n required to accurately determine the position and orientation of the 3D Cartesian coordinate frame established in that space?

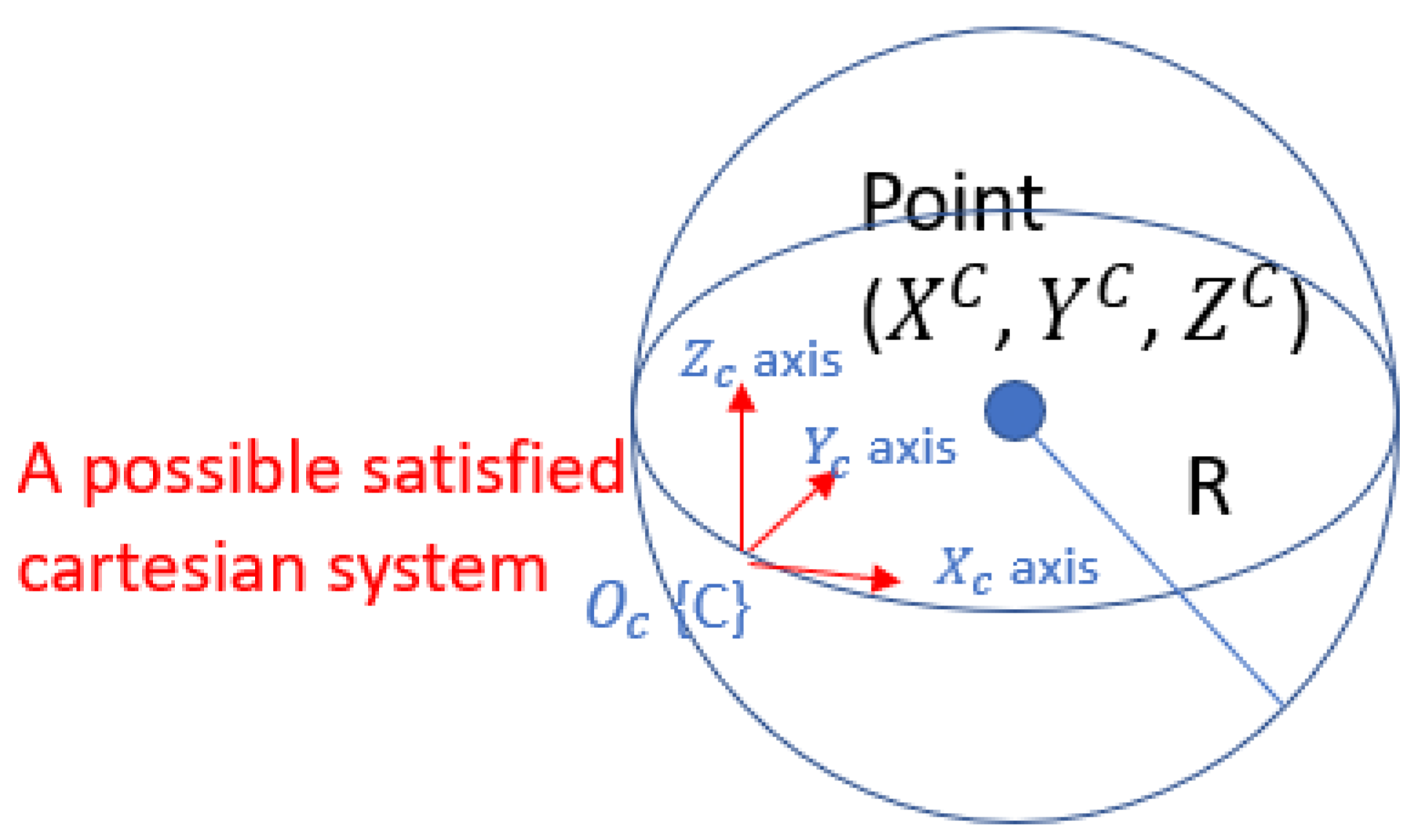

1) P1P problem with the stereo camera:

If we know the coordinates of a single point in space, defined by a 3D Cartesian coordinate system, an infinite number of corresponding coordinate systems can be established. Any such coordinate system can have its origin placed on the surface of a sphere centered at this point, with a radius

, where

are the coordinates measured by the Cartesian system (see

Figure 3).

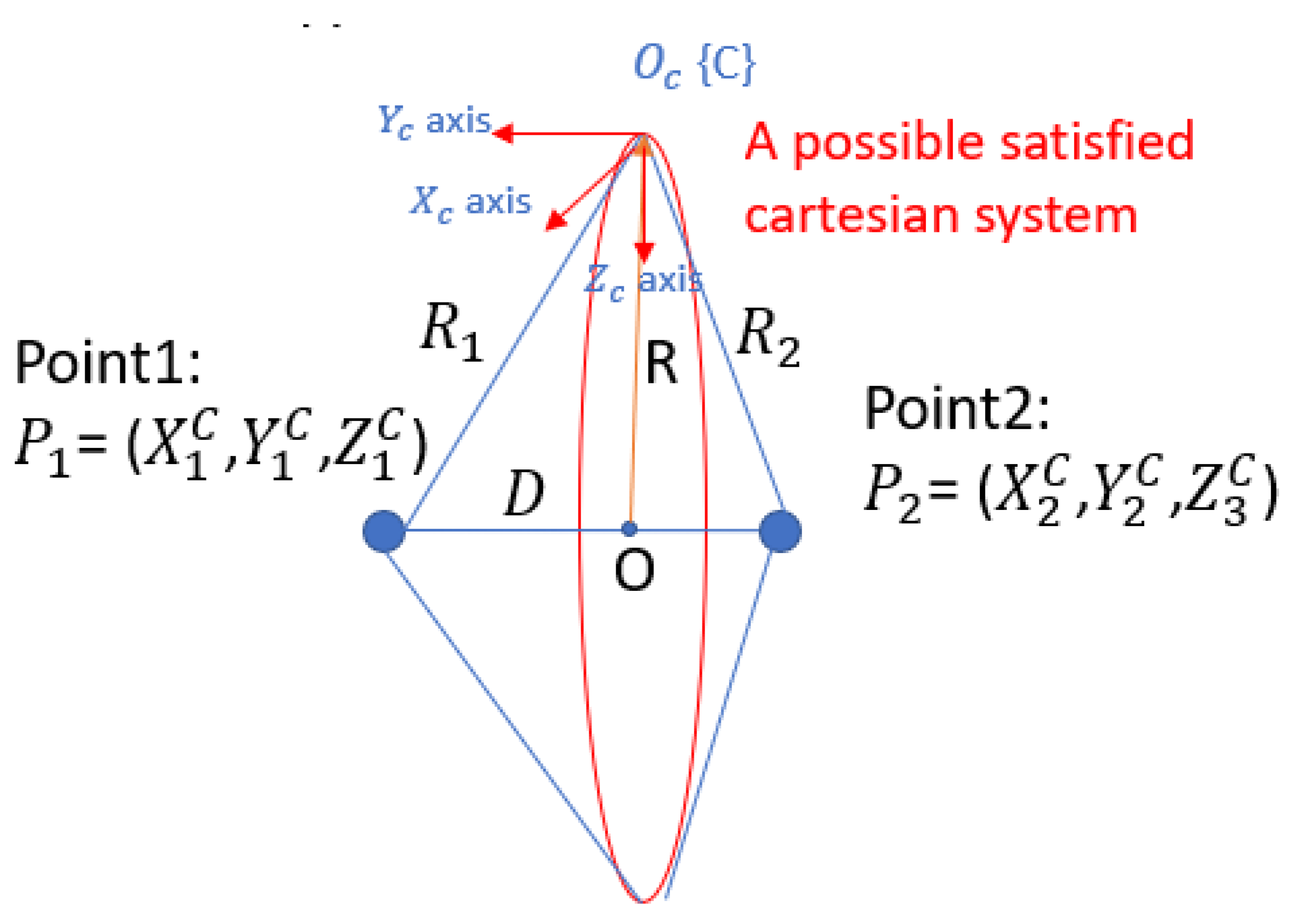

2) P2P problem with the stereo camera:

When the coordinates of two points in space are known, an infinite number of corresponding coordinate systems can be established. Any valid coordinate system can have its origin positioned on a circle centered at point

O with a radius

as illustrated in

Figure 4. This circle is constrained by the triangle formed by points

,

, and

, where the sides of the triangle are defined by the lengths

and

. Specifically,

The radius of the circle

R corresponds to the height of the base

D of the triangle. The center of the circle

O is located at the intersection of the height and the base.

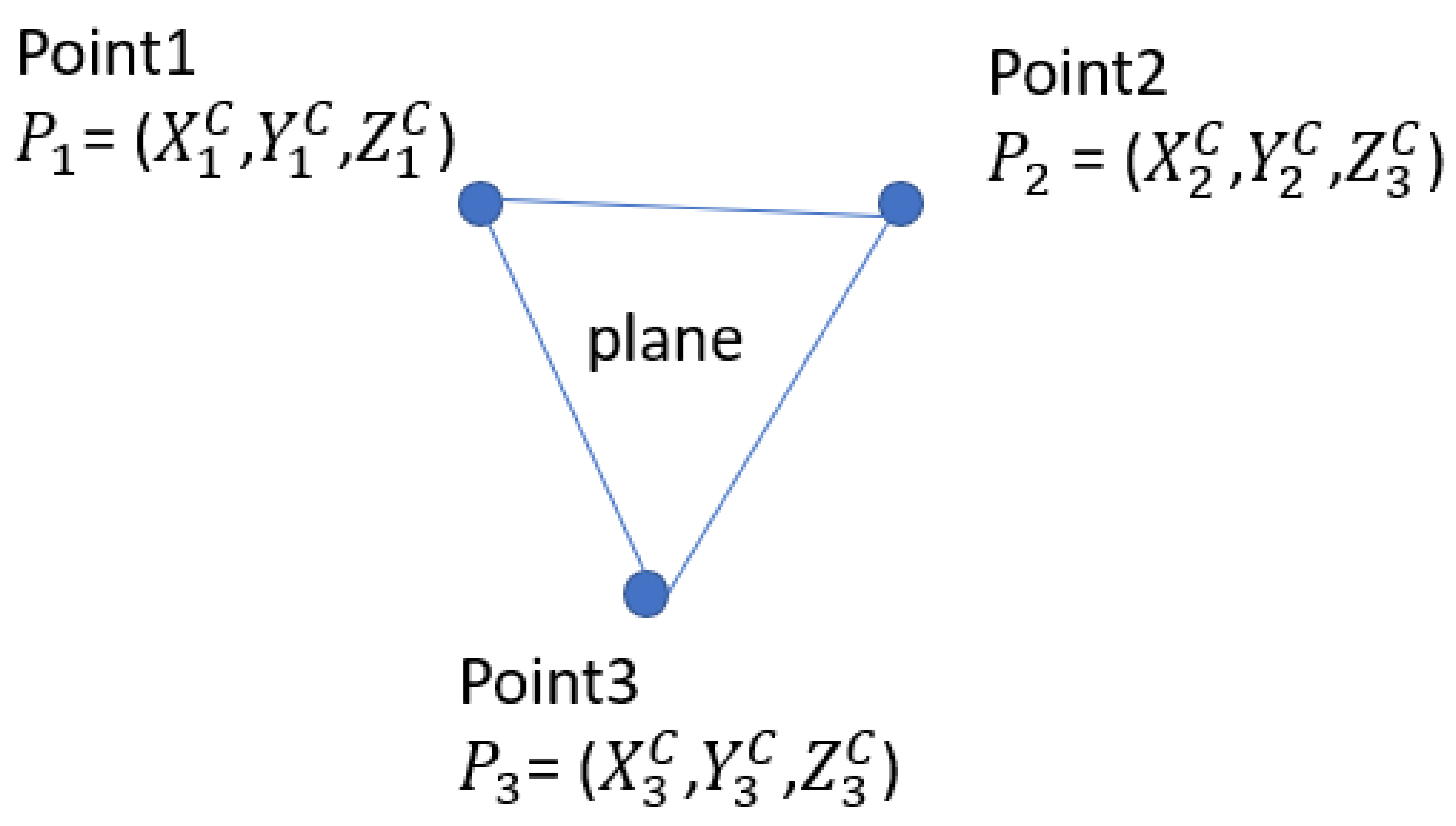

3) P3P problem with the stereo camera:

When three points in space are known, and the lines connecting these points are not collinear, we can uniquely establish one coordinate system. As illustrated in the figure below, three non-collinear points define a plane in space, which has a uniquely defined normal unit vector

. Given the coordinates of the three points, we can calculate vectors as follows: the vector

= (

), and the vector

= (

). The unit vector

which is perpendicular to the plane formed by these three points, can be expressed as:

Here, × denotes the cross product.

The angles between

and XYZ axes of the coordinate system can be expressed as follows:

Where

and

are the angles between

and the unit vectors in the X, Y, and Z directions, denoted as

,

and

respectively. Therefore, with the direction

fixed in space, the orientations of each axis of the coordinate system can be computed uniquely.

According to the P1P problem, the origin of the coordinate system must lie on the surface of a sphere centered at

with radius

as depicted in

Figure 3. Each coordinate system established with a different origin point on the surface of this sphere results in a unique configuration of the axis orientations. Therefore, as the orientations of the axes are defined in space, the position of the frame (or the position of the origin) is also uniquely defined.

In conclusion, the P3P problem is sufficient to solve the PnP problem for a stereo camera system.

Figure 5.

P3P Problem with a Stereo Camera System.

Figure 5.

P3P Problem with a Stereo Camera System.

Prove Concluded

This proposition indicates that to uniquely determine the full 6 DoFs of the stereo camera, at least three points (or nine 2D features) are required to match in the image-based visual servoing control.

4. Model Development

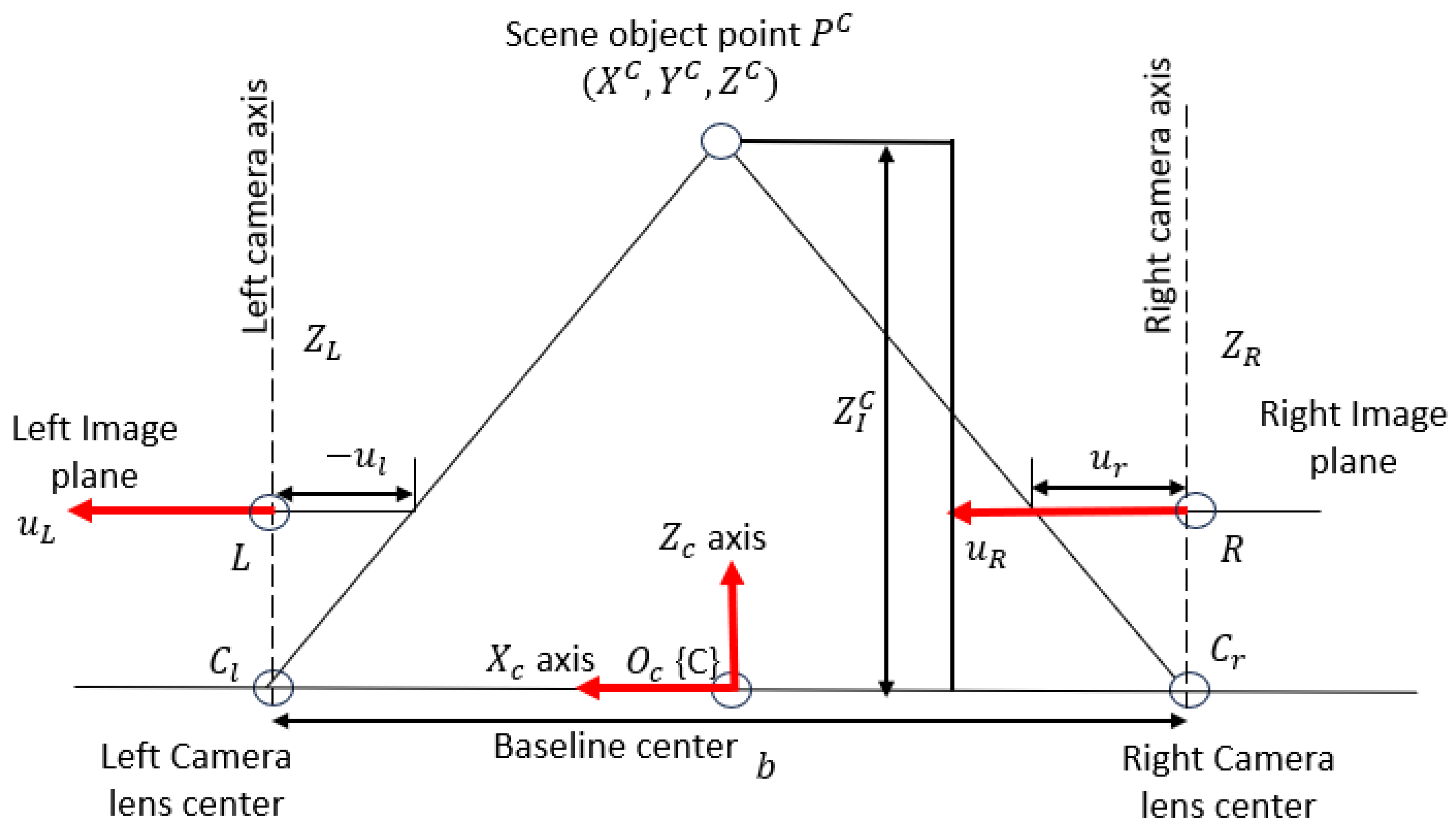

4.1. Stereo Camera Model

Depth between the objects to the camera plane is either approximated or estimated in the IBVS for generating the interaction matrix [

15]. Using a stereo camera system in IBVS eliminates the inaccuracies associated with monocular depth estimation, as it directly measures depth by leveraging the disparity between the left and right images.

The stereo camera model is illustrated in

Figure 6. A stereo camera consists of two lenses separated by a fixed baseline

b. Each lens has a focal length

(measured in mm) which is the distance from the image plane to the focal point. Assuming the camera is calibrated, the intrinsic parameters:

b, is accurately estimated. A scene point

is measured in the 3D coordinate frame {C} centered at the middle of the baseline with its coordinates as

. The stereo camera model maps the 3D coordinates of this point to its 2D coordinates projected on the left and right image plane as

and

, respectively. The full camera projection map, incorporating both intrinsic and extrinsic parameters, is given by:

Where

are the image coordinates of the point and

are the 3D coordinates measured in the camera frame {C}.

is the scale factor that ensures correct projection between 2D and 3D features.

is the intrinsic matrix with a size of 3X3, and the mathematical expression is presented as:

Where

is the skew factor, which represents the angle between the image axes (

u and

v axis).

and

are coordinates offsets in image planes.

In Equation (5),

R is the rotational matrix from camera frame {C} to each image coordinate frame, and

T is the translation matrix from camera frame {C} to each camera lens center. Since there is no rotation between the camera frame {C} and image frames but only a translation along the

axis occurs, the transformation matrices for the left and right image planes are expressed as

Assume the u and v axis are perfectly perpendicular (take k = 0), and there are no offsets in the image coordinates (take

) for both lens. Also, set factor

accounts for perspective depth scaling. The projection equations for the left and right image planes can be rewritten in homogeneous coordinates as:

Equations (9) and (10) establish the mathematical relationship between the 3D coordinates of a point in the camera frame {C} and its 2D projections on the left and right image planes. The pixel value along the

-axis remains the same for both images. As a result, a scene point’s 3D coordinates can be mapped to a set of three image coordinates in the stereo camera system, expressed as:

The mapping function is nonlinear and depends on the stereo camera parameters , specifically b, and .

4.2. Robot Manipulator Kinematic Model

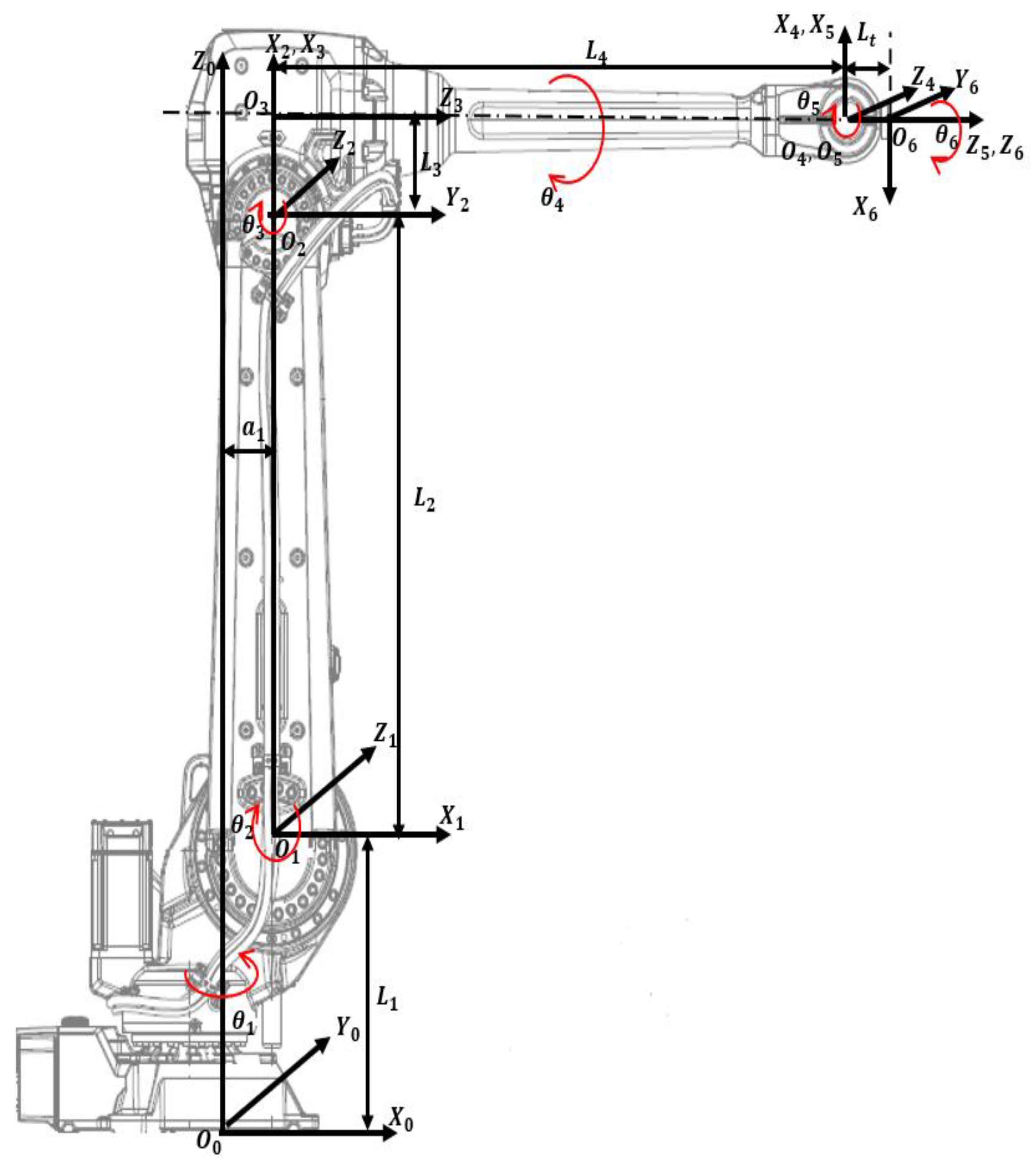

A widely used method for defining and generating reference frames in robotic applications is the Denavit-Hartenberg (D-H) convention [

29]. In this approach, each robotic link is associated with a Cartesian coordinate frame

. According to the D-H convention, the homogeneous transformation matrix

, which represents the transformation from frame

to frame

, can be decomposed into a sequence of four fundamental transformations:

The parameters

,

,

and

define the link and joint characteristics of the robot. Here,

is the link length,

is the joint rotational angle,

is the twist angle, and

is the offset between consecutive links. The values for these parameters are determined following the procedure outlined in [

29].

To compute the transformation from the end-effector frame

(denoted as {E}) to the base frame

(denoted as {O}), we multiply the individual transformations along the kinematic chain:

Furthermore, the transformation matrix from the base frame {O} to the end-effector frame {E} can be derived by taking the inverse of

:

If a point

is defined in the base frame, its coordinates in the end-effector frame

can be found using:

Assuming that the camera remains static relative to the end-effector, we introduce a constant transformation matrix

that maps points from the end-effector frame {E} to the camera frame {C}. For a stereo camera system, this camera frame is located at the center of the stereo baseline, as shown in

Figure 6. The coordinates of a point in space, measured in the base frame, can then be expressed in the camera frame as:

Equation (18) describes how a given 3D point in the base frame

= [

] is mapped to the camera frame

= [

] using transformation:

The mapping function is nonlinear and depends on the current joint angle of robot robot geometric parameter = [, , |i ϵ 1,2,3,4,5,6], and constant transformation matrix

4.3. Eye-in-Hand Kinematic Model

By combining the stereo camera mapping

from Equation (11) and the robot manipulator mapping

from Equation (19), we define a nonlinear transformation 𝓕, which maps any point measured in the base frame {O} to its image coordinates as captured by the stereo camera. This transformation is expressed as:

The Mapping

is nonlinear and depends on variables current joint angles:

and parameters

, which includes stereo camera parameter

, robot geometric parameter

and transformation matrix

. In other words:

4.4. Robot Inverse Kinematic Model

Inverse kinematics determines the joint angles required to achieve a given camera pose relative to the inertial frame. The camera pose in the inertial frame can be expressed as a 4X4 matrix:

Here, the vectors , and represent the camera’s directional vectors for Yaw, Pitch, and Roll, respectively, in the base frame {C}. Additionally, the vector denotes the absolute position of the camera center in the base frame {C}.

The camera pose in the camera frame {C} is straightforward as it can be expressed as another 4X4 matrix:

The nonlinear inverse kinematics problem involves solving for the joint angles

that satisfy the equation:

where

is the transformation from the end-effector frame to the camera frame, and

represents the transformation from the base frame to the end-effector frame, which is a function of the joint angles

.

The formulas for computing each joint angle are derived from the geometric parameters of the robot. The results of the inverse kinematics calculations for the ABB IRB 4600 elbow manipulator [

30], used for simulations in this paper, are summarized in

Appendix A.

4.5. Robot Dynamic Model

Dynamic models are included in the inner joint control loop, which will be discussed in section 6. Without derivation, the dynamic model of a serial of 6-link rigid, non-redundant, fully actuated robot manipulator can be written as [

31]:

Where

is the vector of joint positions, and

is the vector of electrical power input from DC motors inside joints,

is the symmetric positive defined matrix,

is the vector of centripetal and Coriolis effects,

is the vector of gravitational torques,

is a diagonal matrix expressing the sum of actuator and gear inertias,

is the damping factor,

is the gear ratio.

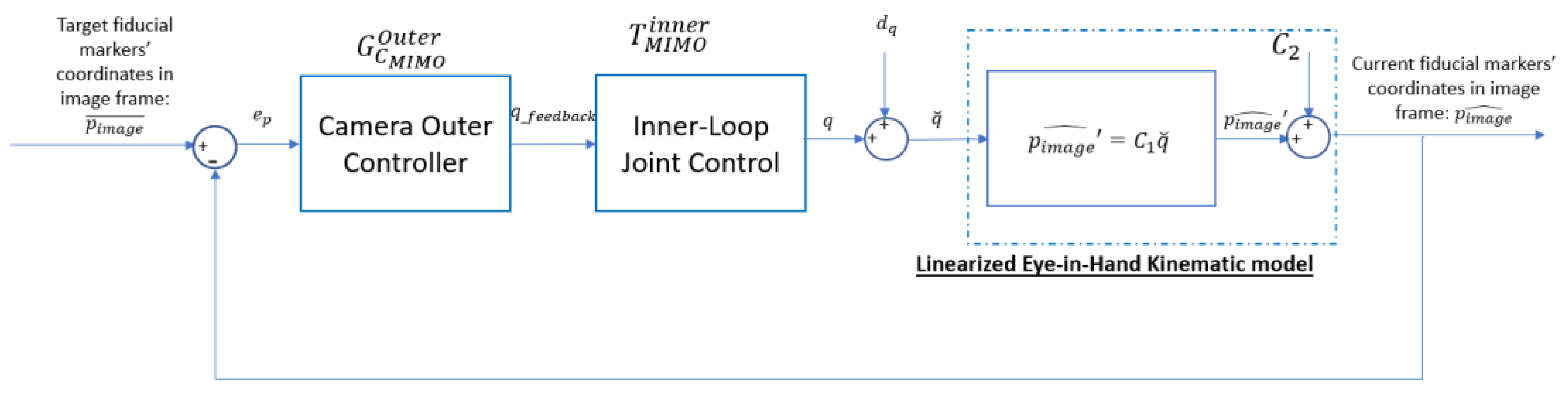

5. Control Policy Diagram

Figure 7 illustrates the overall control system architecture, designed to guide the robot manipulator so that the camera reaches its desired pose,

, in the world space. To achieve this, three fiducial markers are placed within the camera’s field of view, with their coordinates in the inertial frame pre-determined and represented as

. Using the robot’s inverse kinematics and the eye-in-hand kinematic model, the expected image coordinates of these fiducial markers, when viewed from the desired camera pose, are computed as

. These computed image coordinates serve as reference targets in the feedback control loop.

The IBVS framework is implemented within a cascaded feedback loop. In the outer control loop, the camera controller processes the visual feedback error, , which represents the difference between the image coordinates of the fiducial points at the current and desired camera poses. Based on this error, the outer loop generates reference joint angles, , to correct the robot’s configuration.

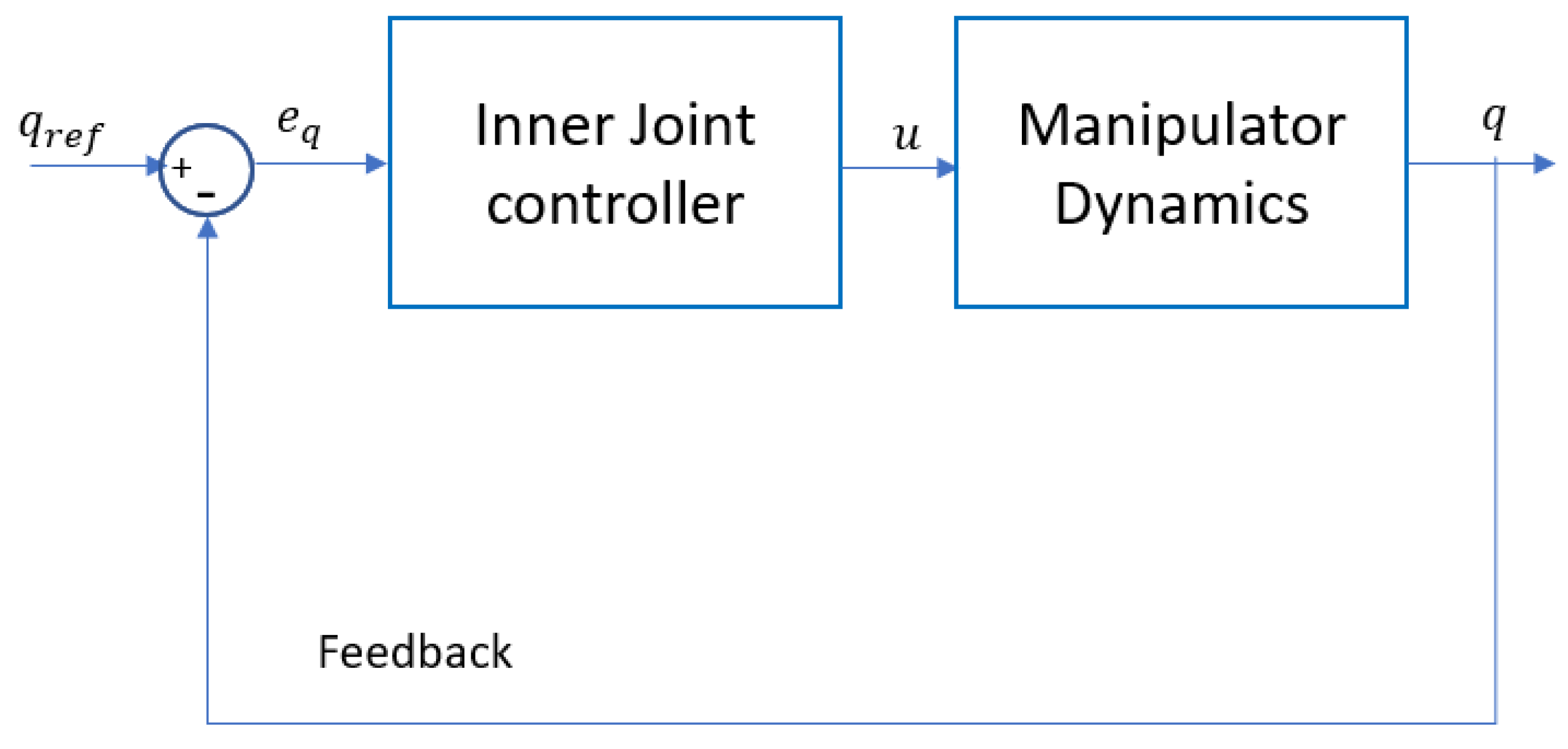

The inner control loop, shown in

Figure 8, incorporates the robot’s dynamic model to regulate the joint angles, ensuring they align with the commanded reference angles,

. However, due to the limitations of low-fidelity and inexpensive joint encoders, as well as inherent dynamic errors such as joint compliance, high frequency noises and low frequency model disturbances are introduced into the system. All sources of errors from the joint control loop are collectively modeled as an input disturbance,

, which affects the outer control loop.

The feedforward control loop operates as an open-loop system, quickly bringing the camera as close as possible to its target pose, despite the presence of input disturbances. The feedforward controller outputs a reference joint angle command, , which is sent to the inner loop to facilitate rapid convergence to the desired configuration.

6. Controller Designs

6.1. Inner Joint Angle Control Loop

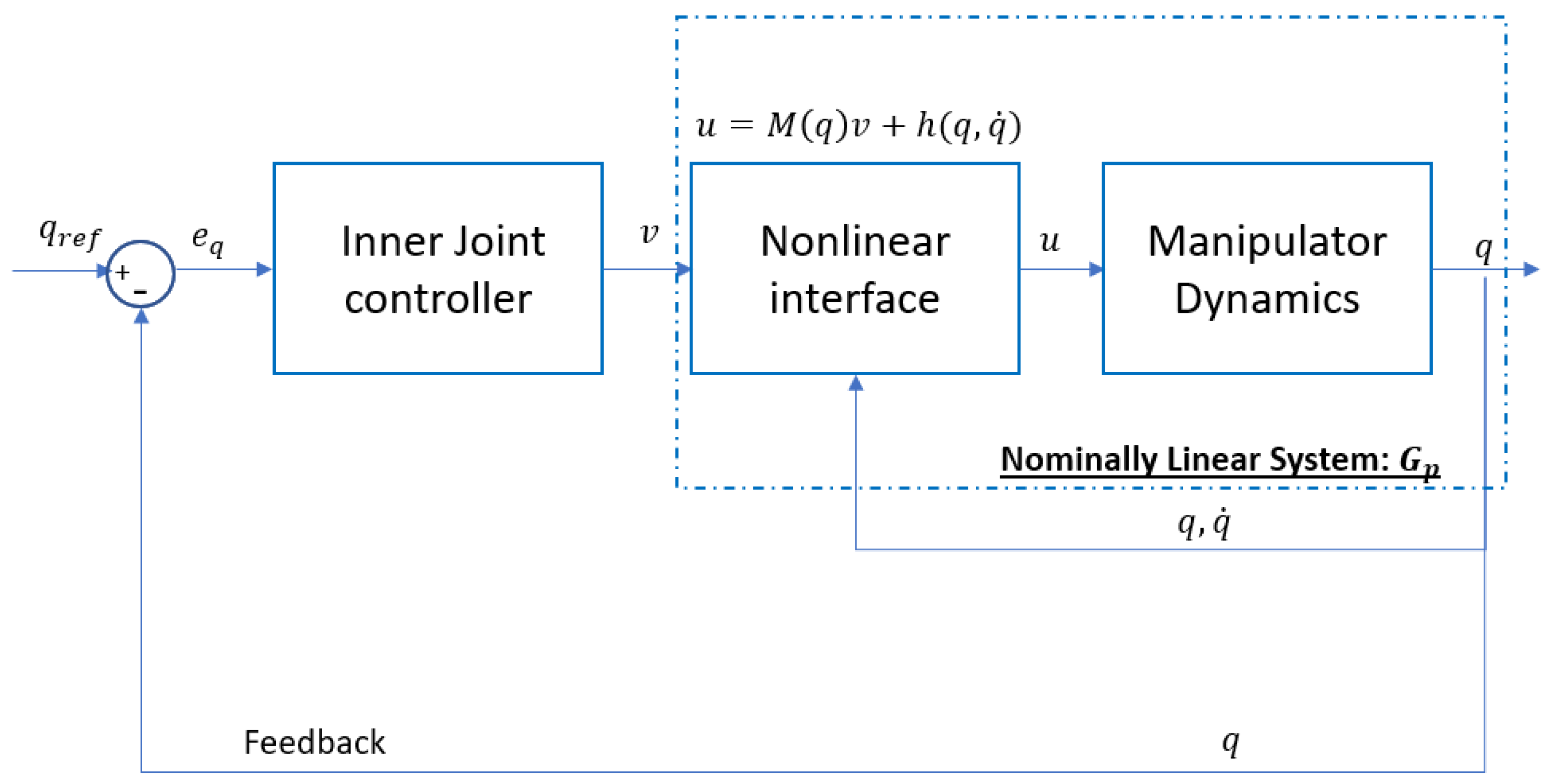

As shown in

Figure 8, the primary goal of the inner joint controller is to stabilize the manipulator dynamics, which is expressed as a nonlinear Equation (26).

Simplify Equation (5.1) as follows:

Then, transform the control input as following:

where

is a virtual input. Then, substitute for

in Equation (27) using Equation (30), and since

is invertible, we will have a reduced system equation as follows:

This transformation is feedback linearization technique with the new system equation given in Equation (31). This equation represents 6 uncoupled double integrators. The overall feedback linearization method is illustrated in

Figure 9. In this control block diagram, the joint angle

are forced to follow the target joint angle

. The Nonlinear interface transforms the linear virtual control input

to the nonlinear control input

by using Equation (30). The output of the manipulator dynamic model, the joint angles,

and their first derivatives,

, are utilized to calculate

and

in the Nonlinear interface. The linear joint controller is designed using Youla parameterization technique [

27] to control the nominally linear system in Equation (31).

The design of a linear Youla controller with nominally linear plant is presented next.

Since the transfer functions between all inputs to outputs in Equation (31) are the same and decoupled, it is valid to first design a Single Input and Single Output (SISO) controller and use the multiple of the same controller for a six-dimension to obtain the Multiple Input and Multiple Output (MIMO) version. In other words, first design a controller

that satisfies:

where

is a single input to a nominally linear system and

is the second order derivative of a joint angle. The controller in

Figure 9 can be then written as:

where

is a

identity matrix. The transfer function of the SISO nominally linear system from Equation (31) is:

Note that

has two Bounded Input Bounded Output (BIBO) unstable poles at origin. To ensure internal stability of the feedback loop, the closed loop transfer function,

, should meet the interpolation conditions [

32]:

Use the following relationship to compute a Youla transfer function:

as:

The

is designed so that it satisfies the conditions in Equations (35) and (36). The sensitivity transfer function,

, is then calculated as follows:

Without providing the design details, the closed-loop transfer function can be in the following form to satisfy the interpolation conditions:

Where

specifies the pole and zero locations and represents the bandwidth of the control system.

can be tuned so that the response can be fast with less-overshoot.

The next step is to derive

from relationships between the closed-loop transfer function,

, the sensitivity transfer function,

and the Youla transfer function,

in Equations (40)–(42):

From Equation (33), a MIMO controller can be computed as follows:

Equation (43) provides the expression of the inner joint controller and the closed loop of the inner loop can be expressed as:

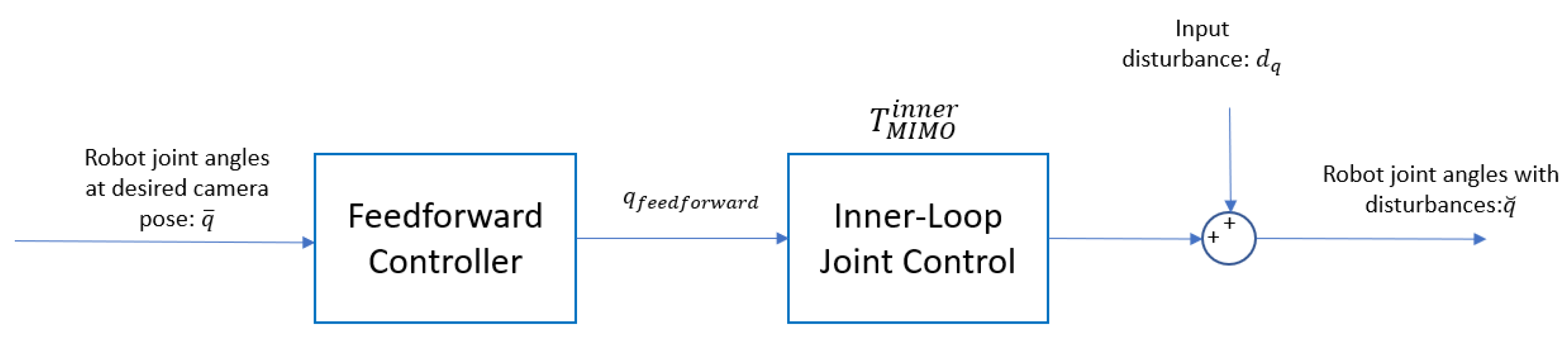

6.2. Feedforward Control Loop

The feedforward loop is an open loop, disturbed by input disturbances as shown in

Figure 10. Feedforward controller is the inverse process of Inner-loop Joint control loop

whose closed-loop transfer function is given in Equation (44).

Therefore, the feedforward controller can be designed as

The double poles s = -1/

are added to make

proper. Choose

so that the added double poles are 10 times larger than the bandwidth of the original improper

In other words,

is chosen as

6.3. Outer Feedback Control Loop

In control system block diagram (

Figure 7), the linear closed loop transfer function has been developed in equation (44) and the eye-in-hand kinematic model is a nonlinear map defined in Equations (21) and (22).

When disturbed joint angles

are inputs to the eye-in-hand model, the outputs are expressed as

Revise Equation (22) accordingly, we have:

Where

are fiducial markers’ coordinates in inertial frame, and

are constant parameters, which consist of camera intrinsic parameters, robot geometric parameters, and transformation matrix between the end-effector to the camera.

By choosing a set of linearized points

, the model expressed in Equation (47) can be linearized with those points in Jacobian matrix form as:

Where

is the Jacobian matrix of

evaluated as

Assuming

,

, therefore, Equation (48) can be rewritten as:

Let’s define

, then, the overall block diagram of the linearized system is shown in

Figure 11.

The linearized plant transfer function is derived as:

As

is coupled, the first step to derive an observer for the multivariable system using model linearization is to find the Smith-McMillan form of the plant [

32].

To get Smith-McMillan form, we can decompose

with singular value decomposition (SVD) as:

where

and

are the left and right unimodular matrices, and

is the Smith-McMillan form of

is a diagonalized transfer function with each nonzero entry equals to a gain multiple the transfer function

; For the

row of

the entry on the diagonal is:

Where

is a numerical vector.

The design of a Youla controller for each nonzero entry in

is trivial in this case as all poles/zeros of the plant transfer function are in the left half-plane, and therefore, they are stable. In this case, the selected decoupled Youla transfer function:

can shape the decoupled closed loop transfer function,

, by manipulating poles and zeros. All poles and zeros in the original plant can be cancelled out and new poles and zeros can be added to shape the closed-loop system. Let’s select a Youla transfer function so that the decoupled closed-loop SISO system behaves like a second order Butterworth filter, such that:

where

is called natural frequency and approximately sets the bandwidth of the closed –loop system. It must be ensured that the bandwidth of the outer-loop is smaller than the inner-loop, i.e.,

.

is called the damping ratio, which is another tuning parameter.

is a 3

3 matrix with all entries equaling to zero. Note that the coordinates from the last point cannot be controlled in the feedback loop.

Then we can compute the decoupled diagonalized Youla transfer functions

The diagonal entry of

row is denoted as

:

Similar to Equations (40)–(42), the final coupled Youla, closed loop, sensitivity, and observer transfer function matrices are computed as:

The controller developed in the above section is based on the linearization of the combined model at a particular linearized point This controller can only stabilize at certain range of joint angles around As current joint angles deviates from the error between the estimated linearized system (48) and the true nonlinear system (47) increases.

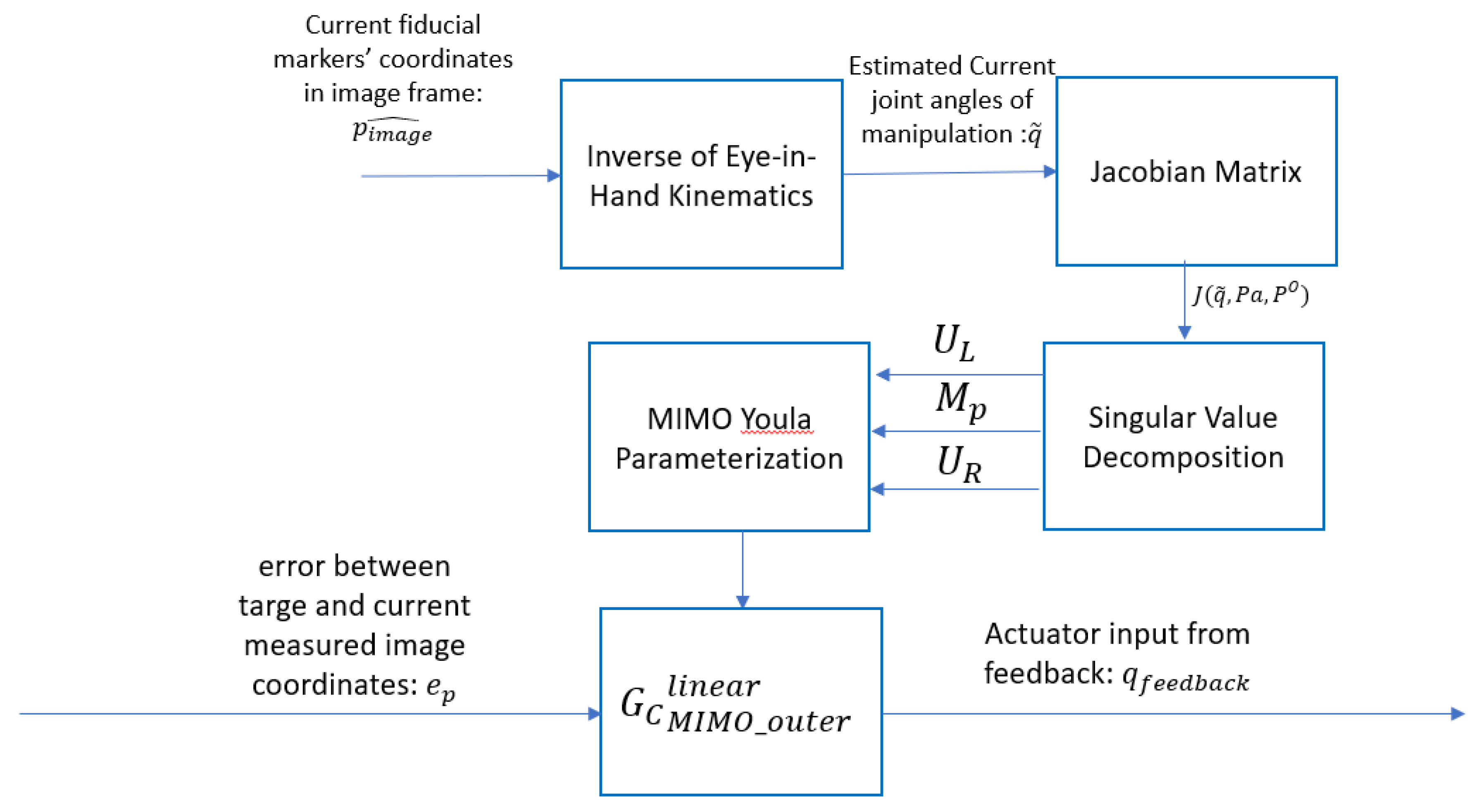

To tackle this problem, we develop an adaptive controller that is computed online based on linearization of the model at current joint angles. This control process is depicted in

Figure 12.

The first step is to estimate current joint angles

from current measured images coordinates

The mathematic models of eye-in-hand kinematic model been given in expression is defined in Equation (22). Therefore, the mathematical function of the inverse model can be derived and expressed as:

Where

is the inverse process of Equation (22), which is a combination of coordinate system transformation from the image frame to the end-effector frame and robot inverse kinematics process. Given estimated current angle

, we can calculate the Jacobian matrix of the nonlinear model at current time. By obtaining left and right unimodular matrices and Smith-McMillan form from singular value decomposition, the current linear controller

can be built by Equations (55)-(58).

7. Simulations Results

To evaluate the performance of our controller design, we simulated two scenarios in MATLAB Simulink using a Zed 2 stereo camera system [

33] and an ABB IRB 4600 elbow robotic manipulator [

30]. The specifications for the camera system and robot manipulator are summarized in the tables in the appendix. The camera system performs 2D feature estimation of three virtual points in space, with their coordinates in the inertial frame selected as:

,

,

.

Many camera noise removal algorithms have been proposed and shown to be effective in practical applications, such as spatial filters [

34], wavelet filters [

35], and the image averaging technique [

36]. Among these denoising methods, there is always a tradeoff between computational efficiency and performance. For this paper, we assume that the images captured by the camera have been preprocessed using one of these methods, and the noise has been almost perfectly attenuated. In other words, the only remaining disturbances in the system are due to unmodeled joint dynamics, such as compliance and flexibility, which are modeled as input disturbances in the controlled system.

Two scenarios were simulated:

In both scenarios, the camera system starts from an initial pose in the inertial frame, denoted as

, and maneuvers target pose, denoted as

.

Table 1 summarizes the initial and final poses for each scenario, along with the corresponding joint configurations.

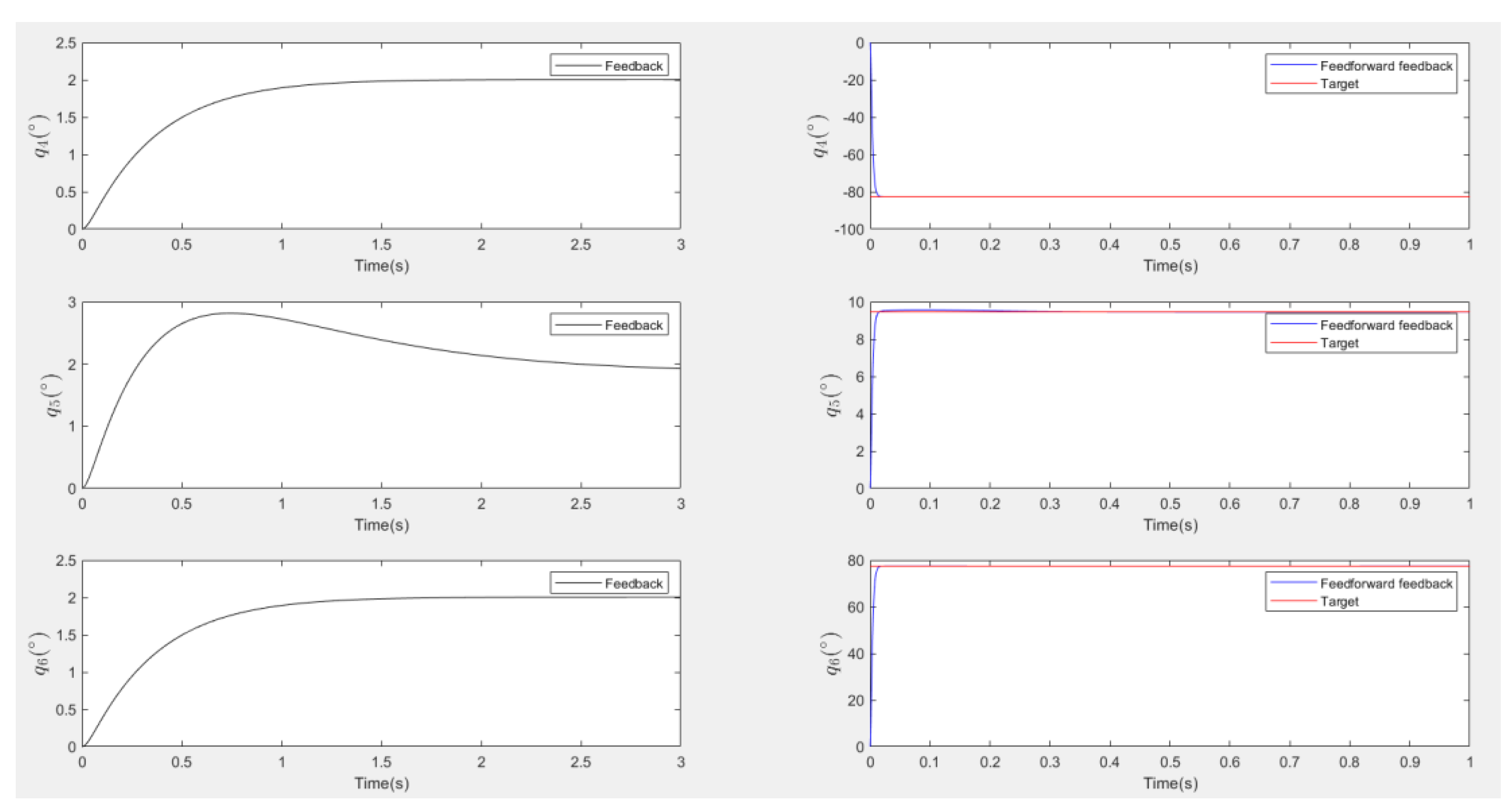

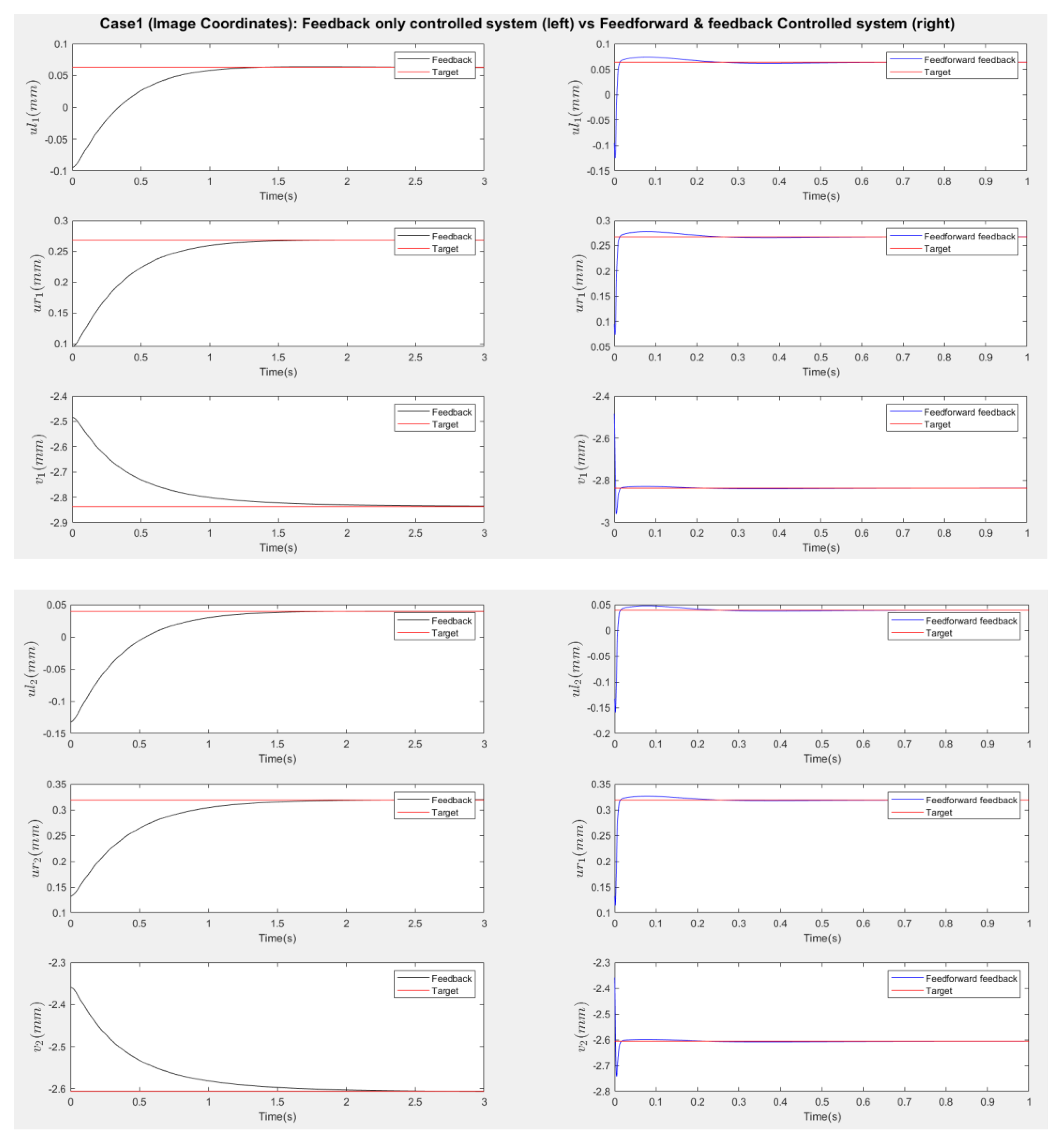

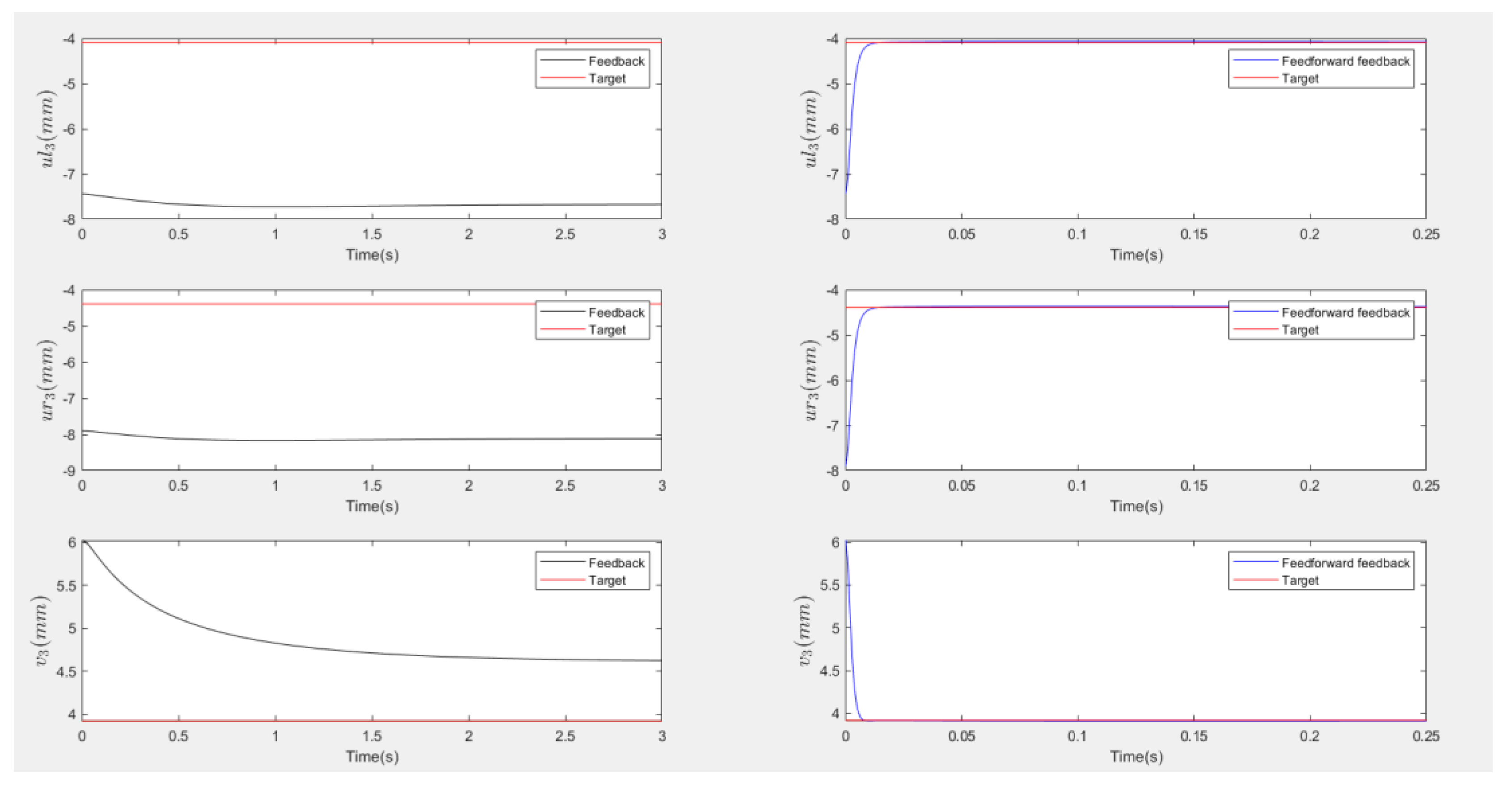

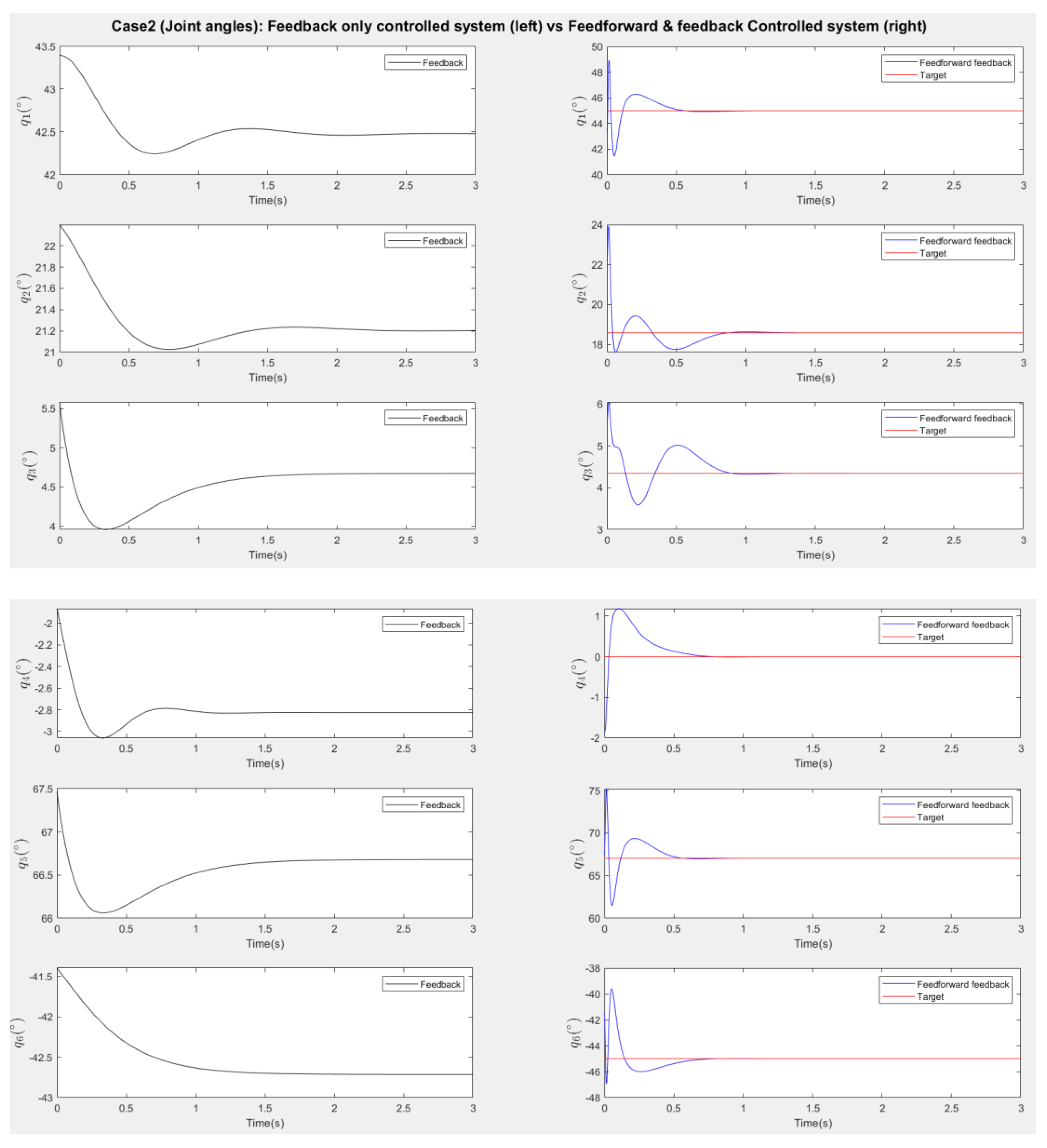

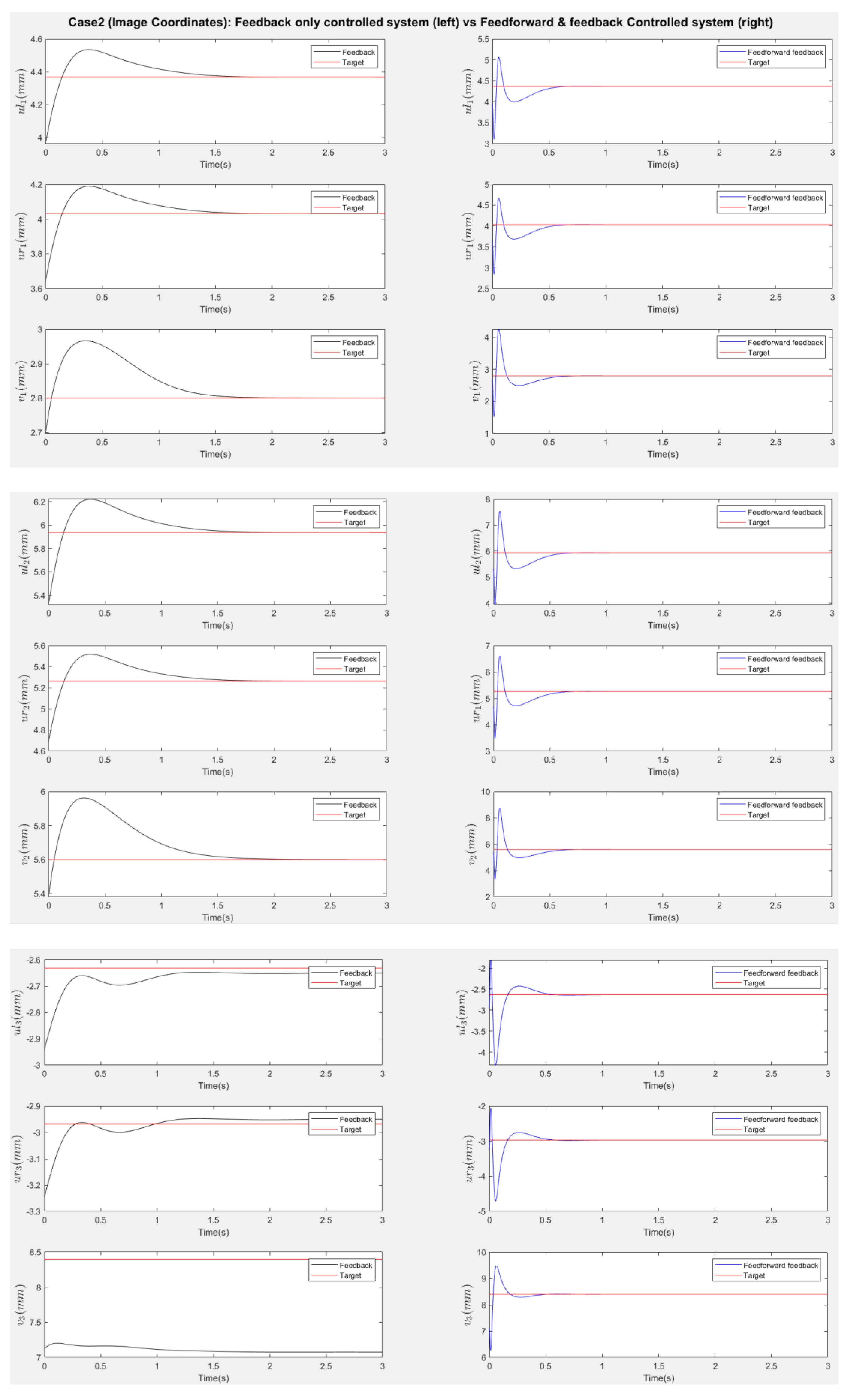

Figure 13 and

Figure 15 present the responses of the six joint angles for the two scenarios, respectively.

Figure 14 and

Figure 16 show the responses of the nine image coordinates over time for each scenario. In each case, the feedback-only controlled system (left plot) is compared to the feedforward-and-feedback controlled system (right plot). These comparisons focus on overshoot, response time, and target tracking performance.

Both scenarios are simulated with bandwidth of the inner-loop as 100rad/s and the bandwidth of the outer-loop as 10rad/s.

The response plots indicate that both the feedback-only controller and the combined feedforward-and-feedback controller successfully stabilize the system and reach a steady state within three seconds, even in the presence of small input disturbances (Scenario Two). However, the feedback-only controller fails to guide the camera to its desired pose and falls into local minima, as evident from the third point’s coordinates ( ), which do not match the target at steady state. This issue arises from the overdetermined nature of the stereo-based visual servoing system, where the number of output constraints (9) exceeds the degrees of freedom (DoFs) available for control (6). As a result, the feedback controller can only match six out of nine image coordinates, leaving the rest coordinates unmatched.

In contrast, the feedforward-and-feedback controller avoids local minima and accurately moves the camera to the target pose. This is because the feedforward component directly controls the robot’s joint angles rather than image features. Since the joint angles (6 DoFs) uniquely correspond to the camera’s pose (6 DoFs), the feedforward controller helps the system reach the global minimum by using the desired joint configurations as inputs.

When comparing performance, the system with the feedforward controller exhibits a shorter transient period (less than 2 seconds) compared to the feedback-only system (less than 3 seconds). However, the feedforward controller can introduce overshoot, particularly in the presence of disturbances. This occurs because feedforward control provides an immediate control action based on desired setpoints, resulting in significant initial actuator input that causes overshoot. Additionally, a feedforward-only system is less robust against disturbances and model uncertainties. Fine-tuning the camera’s movement under these conditions requires a feedback controller.

Therefore, the combination of feedforward and feedback control ensures fast and accurate camera positioning. The feedforward controller enables rapid convergence toward the desired pose, while the feedback controller improves robustness and corrects errors due to disturbances or uncertainties. Together, they work cooperatively to achieve optimal performance.

8. Conclusions

In this article, we first provide a systematic proof of the PnP problem for a stereo camera system and then propose an innovative control policy to address the overdetermination issues in image-based visual servoing (IBVS) control. Results from two simulation scenarios demonstrate that the proposed algorithm successfully brings the camera to the desired pose with high accuracy and speed.

Several existing approaches [

21,

22,

23], mentioned in the introduction, have also addressed the issue of local minima in IBVS. Compared to those methods, the key advantage of our system is its simplicity and ease of implementation. A linear feedforward controller is sufficient to handle the local minimum problem without requiring complex online optimization as in MPC or additional 3D feature measurements as in 2 ½-D visual servoing. The feedback loop is designed following the traditional IBVS structure but incorporates a higher-fidelity dynamic model. The adaptive features in the feedback controller stabilize the system across the entire state space, achieved by combining multiple linear Youla-parameterized controllers. To reduce computational overhead, we can lower the online update frequency or predesign several linear Youla controllers offline and switch between them smoothly using a switching algorithm.

However, the feedforward design introduces challenges, particularly with large overshoots that can cause erratic joint movements. This may increase the risk of accidents and potential damage to the robot. A possible solution is to optimize the controller parameters—such as bandwidth and damping ratios—which can be explored in future work. In addition, feedback and feedforward controllers can be designed simultaneously using

control techniques [

37], which optimizes the system’s stability and performance in the presence of disturbances.

In summary, this paper investigates the overdetermination problem in stereo-based IBVS tasks. While future improvements to the algorithm are possible, the proposed control policy has demonstrated significant potential as an accurate and fast solution for real-world eye-in-hand (EIH) visual servoing tasks.

Appendix A

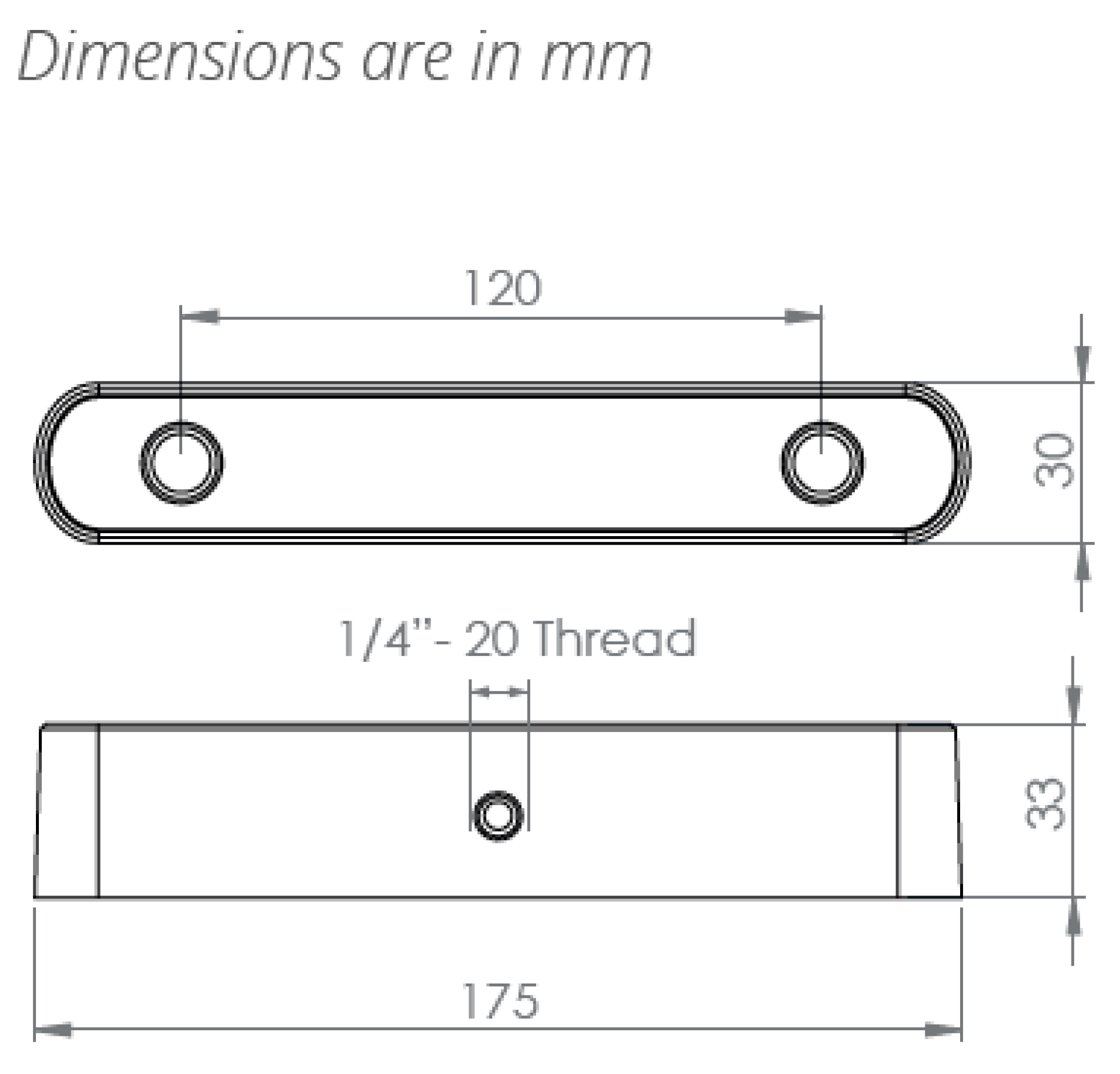

In this section, we will show the geometric model of a specific robot manipulator ABB IRB 4600 45/2.05[

23] and a figure of a camera model: Zed 2 with dimensions [

24]. This section also contains specification tables of robots’ dimensions, camera, and motor installed inside the joints of manipulators.

Figure A1.

IRB ABB 4600 Model with attached frames.

Figure A1.

IRB ABB 4600 Model with attached frames.

Figure A2.

Zed 2 stereo camera model with dimensions.

Figure A2.

Zed 2 stereo camera model with dimensions.

Table A1.

Specification Table of ABB IRB 4600 45/2.05 Model (Dimensions).

Table A1.

Specification Table of ABB IRB 4600 45/2.05 Model (Dimensions).

| Parameters |

Values |

| Length of Link 1: |

495 mm |

| Length of Link 2: |

900 mm |

| Length of Link 3: |

175 mm |

| Length of Link 3: |

960 mm |

| Length of Link 1 offset: |

175 mm |

| Length of Spherical wrist: |

135 mm |

| Tool length (screwdriver): |

127 mm |

Table A2.

Specification Table of ABB IRB 4600 45/2.05 Model (Axis Working range).

Table A2.

Specification Table of ABB IRB 4600 45/2.05 Model (Axis Working range).

| Axis Movement |

Working range |

| Axis 1 rotation |

+180to -180 |

| Axis 2 arm |

+150to -90 |

| Axis 3 arm |

+75to -180 |

| Axis 4 wrist |

+400to -400 |

| Axis 5 bend |

+120to -125 |

| Axis 6 turn |

+400to -400 |

Table A3.

Specification Table of Stereo Camera Zed 2.

Table A3.

Specification Table of Stereo Camera Zed 2.

| Parameters |

Values |

| Focus length: f |

2.8 mm |

| Baseline: B |

120 mm |

| Weight: W |

170g |

| Depth range: |

0.5m-25m |

| Diagonal Sensor Size: |

6mm |

| Sensor Format: |

16:9 |

| Sensor Size: W X H |

5.23mm X 2.94mm |

| Angle of view in width: |

86.09° |

| Angle of view in height: |

55.35 |

Table A4.

Specification Table of Motors and gears.

Table A4.

Specification Table of Motors and gears.

| Parameters |

Values |

| DC Motor |

| Armature Resistance: |

0.03 |

| Armature Inductance: |

0.1 mH |

| Back emf Constant: |

7 mv/rpm |

| Torque Constant: |

0.0674 N/A |

| Armature Moment of Inertia: |

0.09847 kg |

| Gear |

| Gear ratio: |

200:1 |

| Moment of Inertia: |

0.05 kg |

| Damping ratio: |

0.06 |

Appendix B

In this section, we will show forward kinematics and inverse kinematics of the 6 DoFs revolute robot manipulators. The results are consistent with the model ABB IRB 4600.

Forward kinematics refers to the use of kinematic equations of a robot to compute the position of the end-effector from specified values for the joint angles and parameters. The equations are summarized in the below:

where

,

and

are the end-effector’s directional vector of Yaw, Pitch and Roll in base frame

(

Figure A1). And

are the vector of absolute position of the center of the end-effector in base frame

. For a specific model ABB IRB 4600-45/2.05 (Handling capacity: 45 kg/ Reach 2.05m) the dimensions and mass are summarized in

Table A1.

Inverse kinematics refers to the mathematical process of calculating the variable joint angles needed to place the end-effector in a given position and orientation relative to the inertial base frame. The equations are summarized in the below:

where

,

,

and

have been defined above in the forward kinematic discussion.

References

- E. Cai, R. Rossi, and C. Xiao, “Improving learning-based camera pose estimation for image-based augmented reality applications,” in Extended Abstracts of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Hamburg, Germany, 2023, pp. 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Stier, N., Angles, B., Yang, L., Yan, Y., Colburn, A., & Chuang, M. (2023). LivePose: Online 3D Reconstruction from Monocular Video with Dynamic Camera Poses. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision.

- X. Li and H. Ling, “Hybrid Camera Pose Estimation With Online Partitioning for SLAM,” in IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 1453–1460, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. S. Jacob and S. S, “A comparative study of pose estimation algorithms for visual navigation in autonomous robots,” International Robotics & Automation Journal, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 1–7, 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. E. Lee, J. Tremblay, T. To, J. Cheng, T. Mosier, O. Kroemer, D. Fox, and S. Birchfield, “Camera-to-Robot Pose Estimation from a Single Image,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1911.09231, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/1911.09231.

-

Fischler, M. A.; Bolles, R. C. (1981). “Random Sample Consensus: A Paradigm for Model Fitting with Applications to Image Analysis and Automated Cartography”. Communications of the ACM. 24 (6): 381–395. doi:10.1145/358669.358692. S2CID 972888.

- M. Bujnak, Z. Kukelova and T. Pajdla, “A general solution to the P4P problem for camera with unknown focal length,” 2008 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Anchorage, AK, USA, 2008, pp. 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Lepetit, V.; Moreno-Noguer, M.; Fua, P. (2009). “EPnP: An Accurate O(n) Solution to the PnP Problem”. International Journal of Computer Vision. 81 (2): 155–166. doi:10.1007/s11263-008-0152-6. hdl:2117/10327. S2CID 207252029.

- Terzakis, George; Lourakis, Manolis (2020). “A Consistently Fast and Globally Optimal Solution to the Perspective-n-Point Problem”. Computer Vision – ECCV 2020. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 12346. pp. 478–494. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-58452-8_28. ISBN 978-3-030-58451-1. S2CID 226239551.

- M.N. Alkhatib, A.V. Bobkov, N.M. Zadoroznaya, Camera pose estimation based on structure from motion, Procedia Computer Science, Volume 186, 2021, Pages 146-153, ISSN 1877-0509. [CrossRef]

- J. Wang, Y. Wang, C. Guo, S. Xing and X. Ye, “Fusion of Visual Odometry Information for Enhanced Camera Pose Estimation,” 2023 8th International Conference on Control, Robotics and Cybernetics (CRC), Changsha, China, 2024, pp. 306-309. [CrossRef]

- Naseer T., Burgard W. Deep regression for monocular camera-based 6-dof global localization in outdoor environments 2017 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, IROS, IEEE (2017), pp. 1525-1530.

- A. Kendall, M. Grimes, R. Cipolla, Posenet: A convolutional network for real-time 6-DOF camera relocalization, in: Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, 2015, pp. 2938–2946.

- A. Kendall, R. Cipolla, Geometric loss functions for camera pose regression with deep learning, in: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2017, pp. 5974–5983.

- F. Chaumette and S. Hutchinson. Visual servo control. I. Basic approaches. IEEE Robotics & Automation Magazine.2006;13(4):82-90. [CrossRef]

- Y. Ma, X. Liu, J. Zhang, D. Xu, D. Zhang, and W. Wu, “Robotic grasping and alignment for small size components assembly based on visual servoing,” Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol., vol. 106, nos. 11–12, pp. 4827–4843, Feb. 2020.

- T. Hao, D. Xu and F. Qin, “Image-Based Visual Servoing for Position Alignment With Orthogonal Binocular Vision,” in IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement, vol. 72, pp. 1-10, 2023, Art no. 5019010. [CrossRef]

- M. Sheckells, G. Garimella and M. Kobilarov, “Optimal Visual Servoing for differentially flat underactuated systems,” 2016 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Daejeon, Korea (South), 2016, pp. 5541-5548. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Yuanze, et al. “NeRF-IBVS: Visual Servo Based on NeRF for Visual Localization and Navigation.” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2023.

- Guo K, Cao R, Tian Y, Ji B, Dong X, Li X. Pose and Focal Length Estimation Using Two Vanishing Points with Known Camera Position. Sensors (Basel). 2023 Apr 3;23(7):3694. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- N. R. Gans and S. A. Hutchinson, “Stable Visual Servoing Through Hybrid Switched-System Control,” in IEEE Transactions on Robotics, vol. 23, no. 3, pp. 530-540, June 2007. keywords: {Visual servoing;Cameras;Error correction;Robot vision systems;Gallium nitride;Servosystems;Control. [CrossRef]

- F. Chaumette and E. Malis, “2 1/2 D visual servoing: a possible solution to improve image-based and position-based visual servoings,” Proceedings 2000 ICRA. Millennium Conference. IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation. Symposia Proceedings (Cat. No.00CH37065), San Francisco, CA, USA, 2000, pp. 630-635 vol.1. [CrossRef]

- P. Roque, E. Bin, P. Miraldo and D. V. Dimarogonas, “Fast Model Predictive Image-Based Visual Servoing for Quadrotors,” 2020 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2020, pp. 7566-7572. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X., Bai, Y., Yu, C. et al. A new computational approach for optimal control of switched systems. J Inequal Appl 2024, 53 (2024). [CrossRef]

- E. Malis, F. Chaumette, and S. Boudet, “2 1/2 D Visual Servoing,” 1999.

- Z. Ma and J. Su, “Robust uncalibrated visual servoing control based on disturbance observer,” ISA Transactions, vol. 59, pp. 193–204, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Youla, D., Jabr, H., and Bongiorno, J. Modern Wiener-Hopf Design of Optimal Controllers-Part II: The Multivariable Case. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control.1976; 21(3):319-338. [CrossRef]

- Illingworth J., Kittler J.: A survey of the Hough transform. Comput. Vis. Graph. Image Process. 44(1), 87–116 (1988).

- Denavit, Jacques; Hartenberg, Richard Scheunemann (1955). A kinematic notation for lower-pair mechanisms based on matrices. Trans ASME J. Appl. Mech. .1955;23 (2): 215–221. [CrossRef]

- Anonymous. ABB IRB 4600 -40/2.55 Product Manual [Internet]. 2013. Available from: https://www.manualslib.com/manual/1449302.

- Mark, W.S., M.V. (1989). Robot Dynamics and control. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 1989.

- F. Assadian and K. Mallon “Robust Control: Youla Parameterization Approach” John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., 2022, ch. 10, pp. 217-246. [CrossRef]

- Anonymous. Stereolabs Docs: API Reference, Tutorials, and Integration. Available from: https://www.stereolabs.com/docs [Accessed: 2024-7-18].

- Patidar, P., Gupta, M., Srivastava, S., & Nagawat, A.K. Image De-noising by Various Filters for Different Noise. International Journal of Computer Applications. 2010; 9: 45-50.

- R. Zhao and H. Cui. Improved threshold denoising method based on wavelet transform. 2015 7th International Conference on Modelling, Identification and Control (ICMIC); 2015: pp. 1-4. [CrossRef]

- Ng J., Goldberger J.J. Signal Averaging for Noise Reduction. In: Goldberger J., Ng J. (eds) Practical Signal and Image Processing in Clinical Cardiology. London: Springer; 2010. p. 69-77. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K., Doyle, J. C., & Glover, K. (1996). Robust and Optimal Control. Prentice Hall.

Figure 1.

The eye-in-hand robot configuration.

Figure 1.

The eye-in-hand robot configuration.

Figure 3.

P1P Problem with a Stereo Camera System.

Figure 3.

P1P Problem with a Stereo Camera System.

Figure 4.

P2P problem with a stereo camera system. All potential cartesian systems are located on the circle plotted in red.

Figure 4.

P2P problem with a stereo camera system. All potential cartesian systems are located on the circle plotted in red.

Figure 6.

The projection of a scene object on the stereo camera’s image planes. Note: The v-coordinate on each image plane is not displayed in this plot but is measured along the axis that is perpendicular to and pointing out of the plot.

Figure 6.

The projection of a scene object on the stereo camera’s image planes. Note: The v-coordinate on each image plane is not displayed in this plot but is measured along the axis that is perpendicular to and pointing out of the plot.

Figure 7.

Feedforward-feedback control architecture. Note: In mathematics, the in-loop hardware is equivalent to the Eye-in-hand Kinematics Model.

Figure 7.

Feedforward-feedback control architecture. Note: In mathematics, the in-loop hardware is equivalent to the Eye-in-hand Kinematics Model.

Figure 8.

Inner joint angle control loop.

Figure 8.

Inner joint angle control loop.

Figure 9.

Feedback linearization Youla control design for inner loop.

Figure 9.

Feedback linearization Youla control design for inner loop.

Figure 10.

Feedforward control design

Figure 10.

Feedforward control design

Figure 11.

Feedback loop with linearized model.

Figure 11.

Feedback loop with linearized model.

Figure 12.

Adaptive feedback loop.

Figure 12.

Adaptive feedback loop.

Figure 13.

Scenario one (no disturbances): Response of robot joint angles. (Left: Feed-back only responses, Right: Feedforward-feedback responses).

Figure 13.

Scenario one (no disturbances): Response of robot joint angles. (Left: Feed-back only responses, Right: Feedforward-feedback responses).

Figure 14.

Scenario one (no disturbances): Response of image coordinates. (Left: Feed-back only responses, Right: Feedforward-feedback responses). The three coordinates of the third point are only matched in the feedforward-feedback approach.

Figure 14.

Scenario one (no disturbances): Response of image coordinates. (Left: Feed-back only responses, Right: Feedforward-feedback responses). The three coordinates of the third point are only matched in the feedforward-feedback approach.

Figure 15.

Scenario two (add disturbances): Response of robot joint angles. (Left: Feed-back only responses, Right: Feedforward-feedback responses).

Figure 15.

Scenario two (add disturbances): Response of robot joint angles. (Left: Feed-back only responses, Right: Feedforward-feedback responses).

Figure 16.

Scenario two (add disturbances): Response of image coordinates. (Left: Feed-back only responses, Right: Feedforward-feedback responses). The three coordinates of the third point are only matched in the feedforward-feedback approach.

Figure 16.

Scenario two (add disturbances): Response of image coordinates. (Left: Feed-back only responses, Right: Feedforward-feedback responses). The three coordinates of the third point are only matched in the feedforward-feedback approach.

Table 1.

Camera Pose and Robot Joint Angles at Initial and Final State of Simulation Scenarios.

Table 1.

Camera Pose and Robot Joint Angles at Initial and Final State of Simulation Scenarios.

| Format |

Camera Pose |

Robot JointAngles |

|

|

| Where , and are Yaw, Pitch, and Roll, and (in meters) is the position, measured in inertial frame {O}. |

Where [] in (degrees) are robot joint angles. |

| |

|

|

| |

Camera Pose |

Robot Joint

Angles |

Camera Pose |

Robot Joint

Angles |

| Initial State |

|

|

|

|

| Final State |

|

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).