1. Introduction

Metallic nanoparticles have lately gained popularity in the building materials market due to the modifications they bring to the rheology, mechanical, and microstructural characteristics of cementitious matrices(Arefi & Rezaei-Zarchi, 2012). Cement is made up of siliceous minerals such as alite (C3S), belite (C2S), tricalcium aluminate (C3A), and tetracalcium aluminoferrite. During the hydration process, calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H gel) is formed as a primary phase, providing mechanical strength to composites, and portlandite, which is responsible for the high pH of the cement matrix that protects the steel in reinforced concrete. Most metallic particles may modulate the nucleation of C-S-H gel crystals, densifying the matrix microstructure and enhancing the mechanical strength of cementitious composites(Behfarnia, Azarkeivan, & Keivan, 2013). The literature claims that adding ZnO particles to concrete alters both the compressive strength and the setting time (Amor et al., 2022; Ghafari, Ghahari, Feng, Severgnini, & Lu, 2016; Shafeek, Khedr, El-Dek, & Shehata, 2020). According to several writers, adding ZnO particles to Portland cement mortar can enhance its mechanical qualities (Patil & Dwivedi, 2021; Voicu, Tiuca, Badanoiu, & Holban, 2022). On the other hand, opinions about ZnO's impact on Portland cement hydration are divided (Nochaiya, Sekine, Choopun, Chaipanich, & Compounds, 2015).

The improvement in the mechanical properties may be related to matrix densification based on particle packing, even when with additions at low concentrations of micro or nanoparticles smaller than the cement particles (filler effect). Zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) are currently studied as a photocatalyst and a new antifungal precursor. The morphology of ZnO NPs depends mainly on synthesis techniques, precursors, process conditions, and the pH (Olmo, Chacon, Irabien, & research, 2001).

In cementitious materials, the introduction of nanoparticles has been the focus of substantial investigation due to its potential to increase mechanical performance and microstructure development (Liu, Jin, Gu, Yang, & Materials, 2019; Wang, Lu, Wang, & He, 2020). Furthermore, ZnO NPs boosts the microstructure and increasing concrete's mechanical and durability characteristics of cement pastes and boosting pozzolanic reactions (Al-Kheetan, Jweihan, Rabi, & Ghaffar, 2024; Heikal et al., 2022; Rong, Zhao, & Wang, 2020). Although the precise retarding mechanism has not yet been identified, Arliguie et al. discovered that ZnO could also prevent C3A hydration when the cement's SO3 level exceeded 2.5 %, (Arliguie, Grandet, & Research, 1990) .

Previous researches showed that relatively higher ZnO content were needed to obtained super-retarding cement pastes, but the early/later compressive strength and strength development of cement paste would be all restrained in this case (Korayem et al., 2017). It has been found that nanoparticles within a very small dosage range can significantly affect the properties of cement-based materials due to their nanoscale effects (Singh, 2020; Zhou, Zheng, Liu, He, & Research, 2019). Similarly, ultra-low content of ZnO NPs can retard cement hydration to a greater extent in the early period of cement hydration (Abo-El-Enein et al., 2018; J. Liu et al., 2019),compared to that of higher content of ZnO in cement pastes. More importantly, ZnO NPs would not reduce the later (after 28 days) mechanical properties of hardened cement based materials(Arliguie et al., 1990). Overall, the thorough experimental investigations carried out by researchers in a variety of studies highlight the important role that nano-enhancements play in enhancing the microstructure development and mechanical performance of cementitious materials. Researchers can create more resilient and high-performing building materials by comprehending the processes by which nanoparticles affect the characteristics of cement-based composites. Based on the research, ZnO NPs are anticipated to be the perfect super-retarding agent in cement-based materials. However, because ZnO NPs dissolve and hydrate quickly, further research should be done on the composition and microstructure of hydration products, mechanical performance, and autogenous shrinkage of cement matrix in the early stages of cement hydration. Thus, this work examined the pore size distribution of the hardened matrix, autogenous shrinkage, compressive strength, and new paste setting time. Additionally, the hydration heat evolution, the microstructure and mineral compositions of the hydration products, the ion concentration of the pore solution, and the hydration degree were used to further validate and supplement the cement paste's hydration process in the presence of ZnO NPs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Materials

The chemical composition of raw materials was tested by X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analysis results, detailing the percentage composition of various oxides in cement. The predominant component identified is calcium oxide (CaO), which constitutes 64.30% of the cement composition. Following this, silicon dioxide (SiO

2) is present at 16.10%, and aluminum oxide (Al

2O

3) accounts for 9.40%. Iron (III) oxide (Fe

2O

3) makes up 7.30% of the cement. The analysis also reveals smaller quantities of sulfur trioxide (SO

3) at 2.47%, potassium oxide (K

2O) at 0.38%, sodium oxide (Na

2O) at 0.03%, and magnesium oxide (MgO) at 0.02%, the result was shown in

Table 1. This detailed breakdown of oxide percentages is crucial for understanding the chemical properties and behavior of cement, which in turn influences its performance and suitability for various construction applications. In addition, Natural sand sourced from a quarry in Jerash, characterized by particles smaller than 2 mm, a fineness modulus of 2.25, and a specific gravity of 2.60 g/cm³, was utilized for the mortar mixtures. This sand meets the requirements set by the Jordanian standard specifications (JSS. 96/1987), Clean, potable water was used for mixing and curing purposes, complying with Jordanian standard specifications (JSS. 1376/2003) (Abdallah, Al-Tamimi, Salameh, & Alamir, 2022).

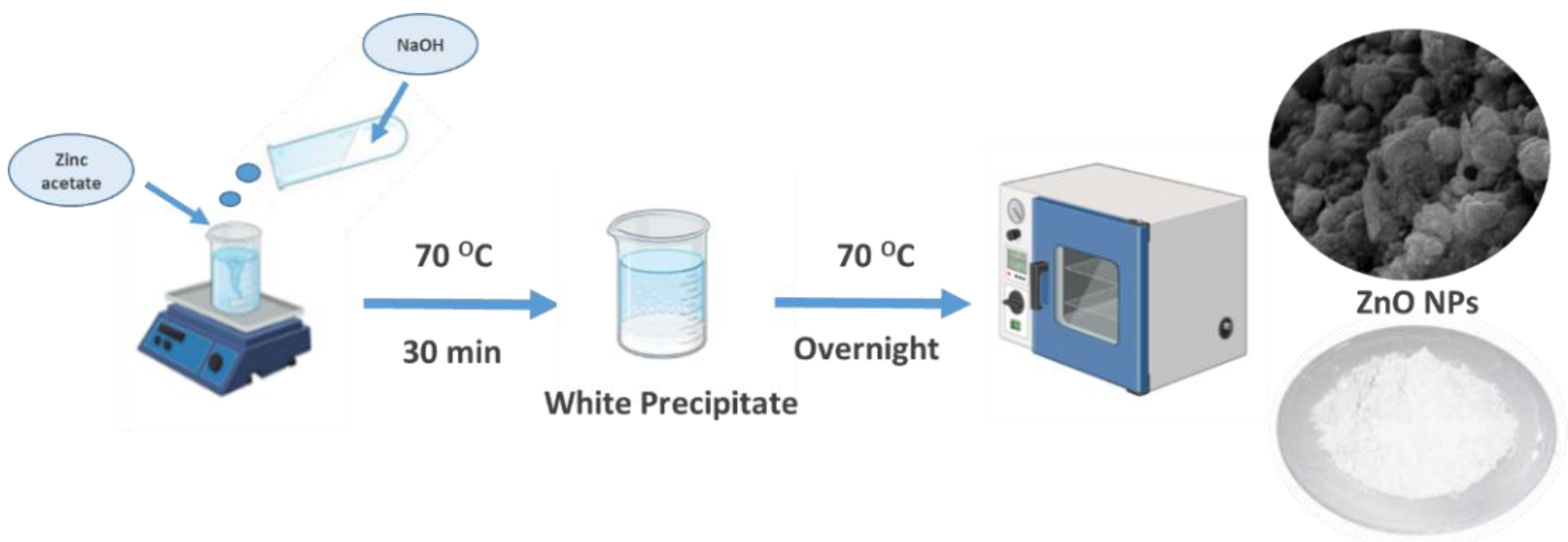

2.2. Preparation of ZnO Nanoparticles

One of the most popular techniques for creating ZnO nanoparticles is co-precipitation a cording to Sharaf et al.(Sharaf et al., 2023),with some modification, as seen in Schematic 1. A zinc precursor solution is created by dissolved zinc acetate in 100 mL of distilled deionized water (DIH2O), at 1000 rpm and heated at 70 °C for 30 min. To cause zinc oxide to precipitate, a precipitating agent typically 100 mL−1 of 1.5 M NaOH was added to the solution. After 30 minutes of stirring, the mixture is boiled to eliminate any remaining solvents. ZnO NPs were obtained by centrifugation at 15,000 rpm for 5 min, washed, Then, ZnO NPs was subsequently dried in a fan oven at 70 °C overnight (Alhudhaibi et al., 2024).

Scheme 1.

ZnO NPs synthesized using the co-precipitation technique.

Scheme 1.

ZnO NPs synthesized using the co-precipitation technique.

2.3. Paste and Mortar Preparation

2.3.1. Paste Speciments

The total amount of cementitious materials (Cm) was calculated as the sum of cement (C) and ZnO NPs. All paste samples were prepared with a fixed water-to-cementitious materials ratio (W/Cm) of 0.29, following the standard consistency for plain cement paste (ASTM, 1998; Standard, 1998). ZnO NPs partially replaced cement in the mixtures at varying percentages of 1.0%, 1.5%, 2.0%, 2.5%, and 3.0% by weight. The specific compositions of the paste samples are presented in

Table 1.

All paste samples were blended using a rotary mixer with an inclined beater. ZnO NPs was first added to the water and stirred at a high speed of 3000 rpm for 5 minutes. This mixture was then combined with cement and mixed for approximately 2 minutes. After mixing, fresh pastes were cast into Vicat’s molds to determine their setting times (STN & Testing: Bratislava, 2017). After 28 days, selected paste specimens were used to measure dry density (unit weight).

2.3.2. Mortar Specimens

Mortar mixes were formulated with a cementitious material-to-sand ratio (Cm/S) of 0.33 by weight and a water-to-cementitious material ratio (W/Cm) of 0.50 by weight. To create various mortar specimens, ZnO NPs was used to replace cement at 1.0%, 1.5%, 2.0%, 2.5%, and 3.0% by weight, as outlined in

Table 2.

2.4. Flexural (Modulus of Rupture) and Compressive Strength Testing

All mortar mixes were prepared using a rotary mixer with an inclined beater. The ZnO NPs was first combined with water and stirred at a high speed of 3000 rpm for 5 minutes. The cement and sand were initially mixed dry for 2 minutes for the mortar specimens. The ZnO NPs suspension was then added and mixed for an additional 3 minutes. Flow table measurements were taken immediately after mixing. Following the flow test, the mortar was cast into 7.07 x 7.07 x 7.07 cm cubes for compressive strength testing(Chang, Shih, Yang, & Hsiao, 2007; Slapø, Kvande, Høiseth, Hisdal, & Lohne, 2018), and into 4 x 4 x 16 cm prisms for both flexural (modulus of rupture) and compressive strength testing(Bauer, de Sousa, Guimarães, Silva, & environment, 2007). A vibrating table was used to compact the specimens. After 24 hours, the specimens were removed from their molds and cured in fresh water at 23 ± 2°C until the testing age. Twelve cubic specimens were prepared for each mixture. All tests were conducted on triplicate specimens. Additionally, twelve prism specimens for each mixture were cast to assess flexural strength at the same ages as the compression tests. Compressive strength was also determined from portions of the prisms tested in flexure.

2.5. Physiochemical Characterization of Incorporating ZnO NPs into Cement-Based Materials

2.5.1. Crystallographic Analysis

Crystalline phases were characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD, X'Pert PRO Theta/2theta, Cu Kα radiation, PANalytical, Netherlands) of the incorporating ZnO NPs into cement-based materials. The pattern was recorded over the angular range 20–70° (2θ) with a step size of 0.0334° and a time per step of 100 s, using Cu Kα radiation (λ = 0.154056 nm) with a voltage of 40 kV and current of 100 mA. The diffractions were analyzed with the software X'Pert High Score Plus v.2.2e, and the database of the International Center for Diffraction Data (ICDD), v.4.(Copeland & Bragg, 1958).

2.5.2. Morphological Analysis

The morphology of the incorporating ZnO NPs into cement-based materials was evaluated using primary electron images of field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM, Hitachi S-4700). The processing and image analysis (Leica Qwin, Leica Microsystems Ltd., Cambridge, England) were performed to determine the morphological mixture of cement paste with ZnO particles. Under these conditions, 200 particles were considered in each measurement(Sharaf et al., 2022).

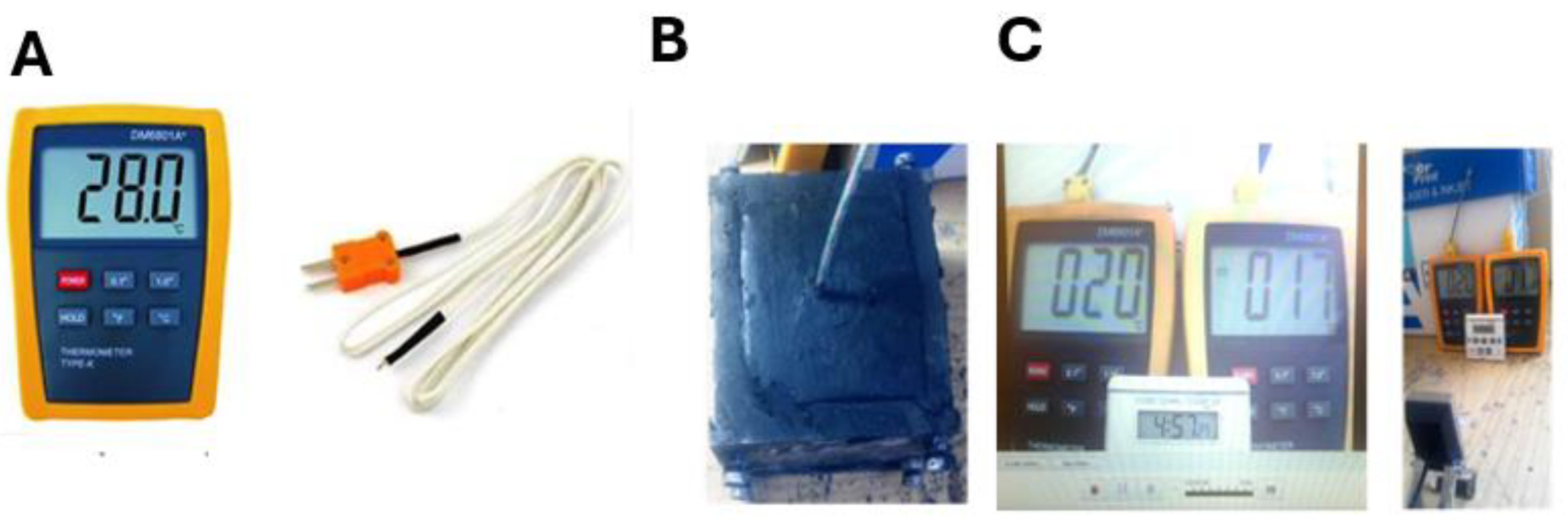

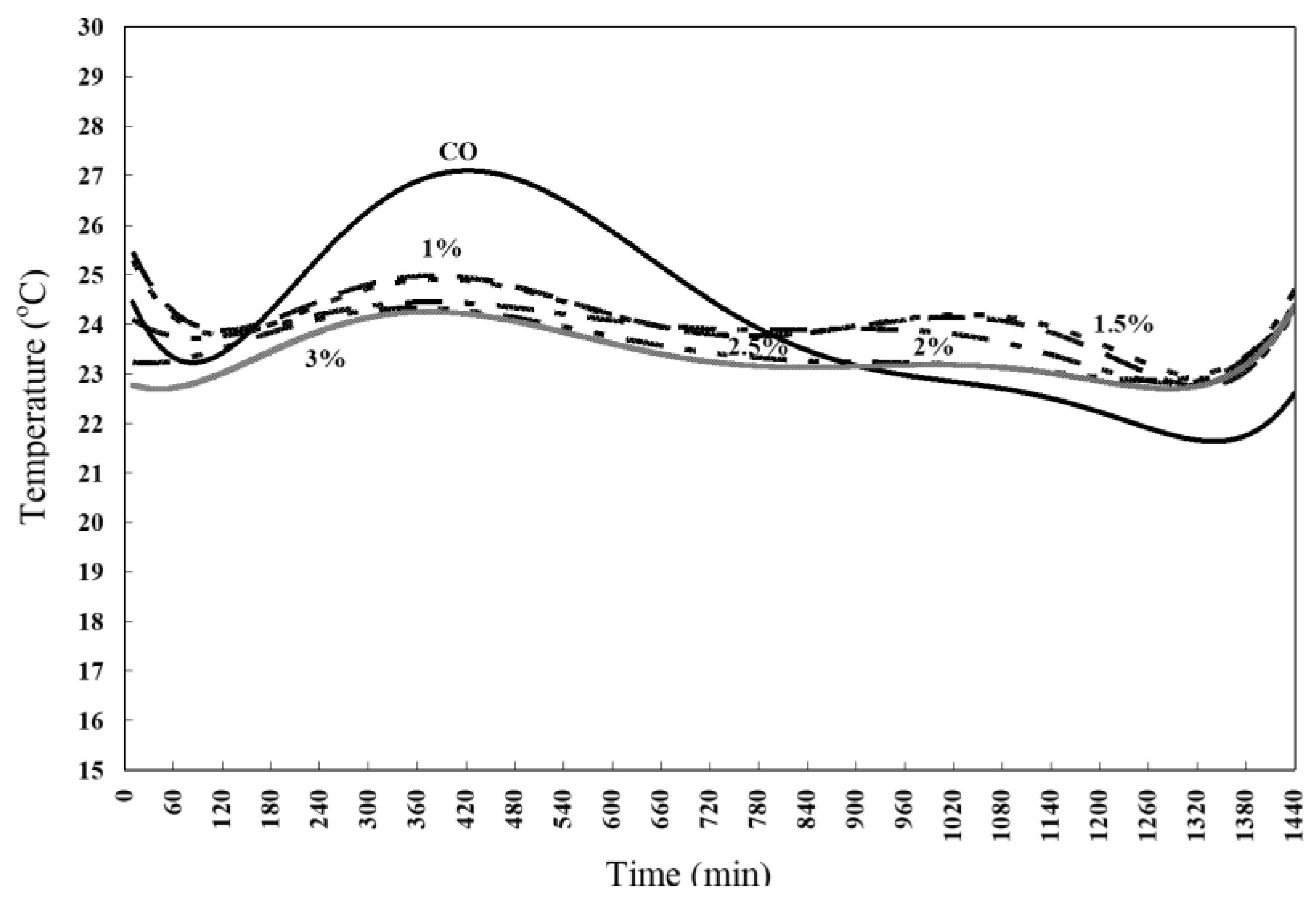

2.5.3. Cubes to Monitor the Ambient Temperature

Five paste specimens were also cast into two-inch (50-mm) test cubes to monitor the ambient temperature at 15-minute intervals for the first 24 hours post-casting. "DM 6801A+" digital thermometers with Type-K thermocouples were used for temperature measurement. These thermocouples were inserted into the center of the mortar cubes (2.5 cm depth). A digital stopwatch recorded the time elapsed from the initial contact between cement and water. During the first 24 hours post-casting, measurements were recorded using software implemented on a chatting camera (as depicted in

Figure 1).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Chemical Properties of ZnO NPs

As per the manufacturer's information, the ZnO NPs has a specific surface area of 157 m²/g, a bulk density of 0.12 g/cm³, a proper density of 3.3 g/cm³, a purity of 99%, and is white, as detailed in

Table 3

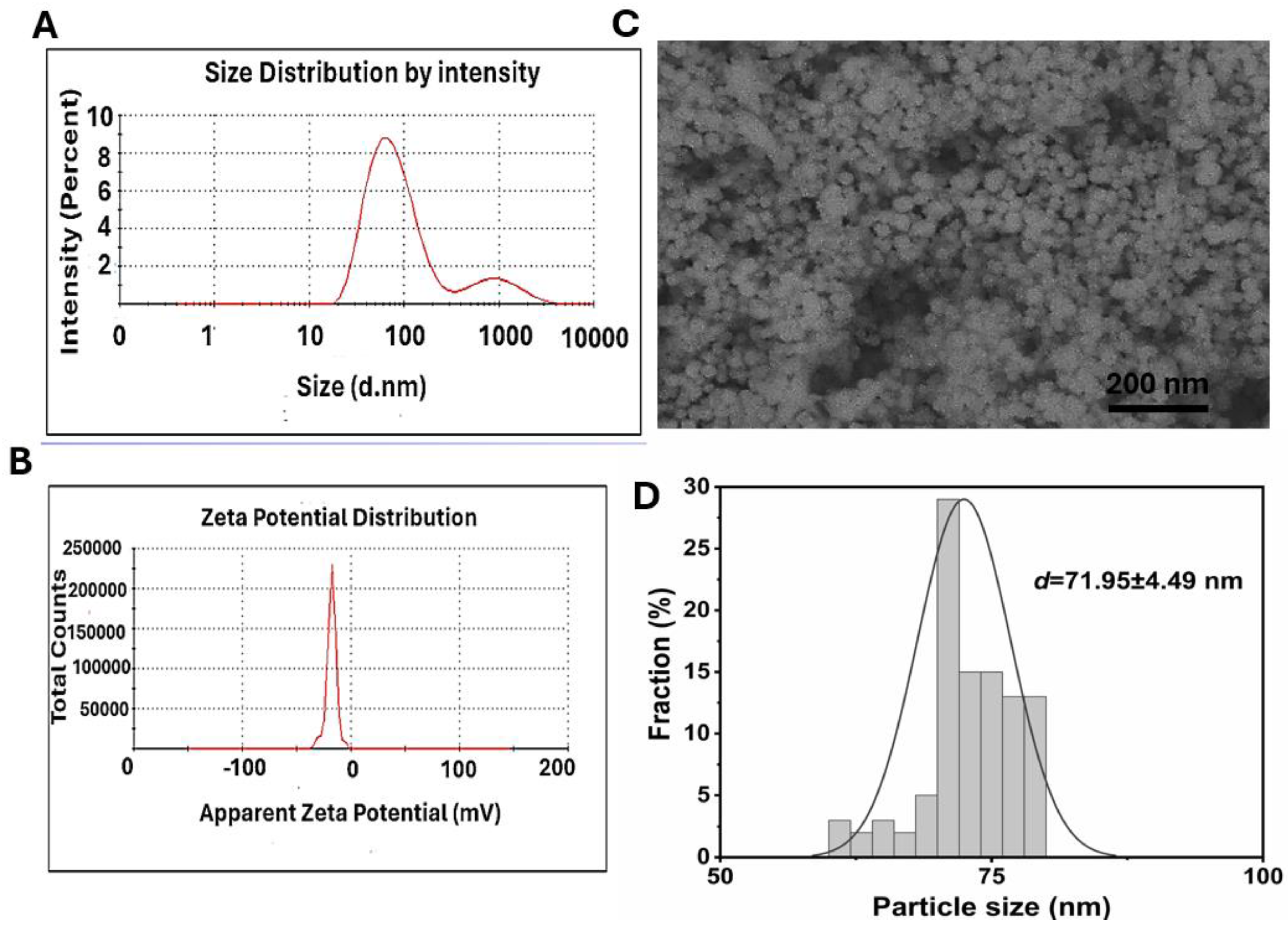

3.2. Characterization of ZnO NPs

The particle size, polydispersity index (PDI), and zeta potential were used to assess the attractive or repulsive electrostatic forces between the particles due to the minimal formation of aggregates when applied to nanocomposites (Gomide et al., 2020; Z.-H. Liu et al., 2019; Österberg, Sipponen, Mattos, & Rojas, 2020).DLS result showed that the average particle size of the ZnO NPs was 72.3 nm, polydispersity index of 0.349, and negative zeta potential of −17.08 mV (

Figure 2A and B). The particle morphology of ZnO NPs without any dispersal treatment. SEM results showed ZnO NPs was found to be spherical or ellipsoidal wurtzite type with the particle size of about 71 nm (

Figure 2C and D). The agglomeration of ZnO NPs was attributed to the electrostatic force and Van der waals force between nanoparticles (Korayem et al., 2017).

3.3. Effect of ZnO NPs Content on the Properties of Cement Paste

3.3.1. Crystalline Study

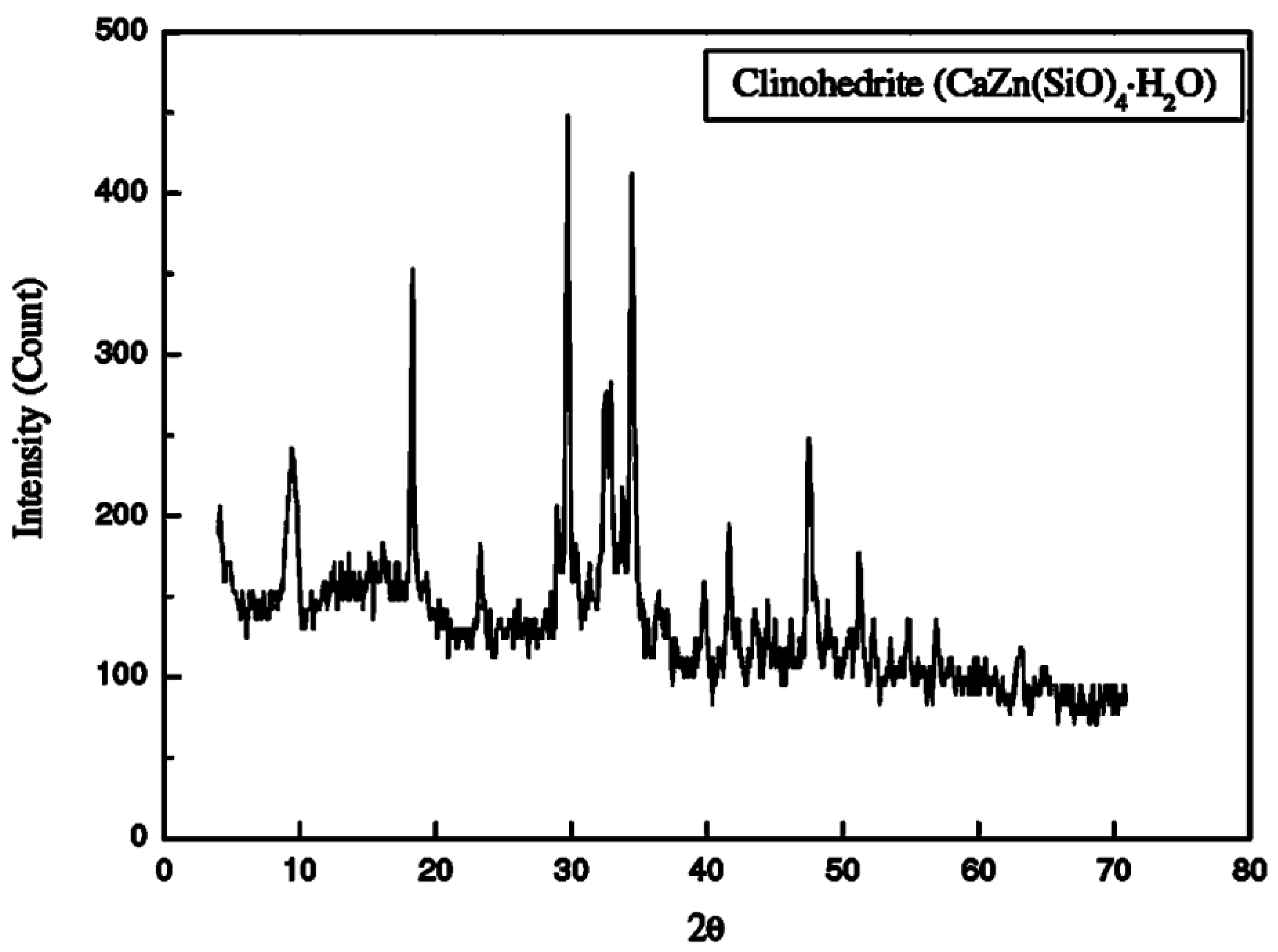

X-ray diffraction (XRD) were employed to analyze the oxide and mineralogical compositions of the ZnO NPs paste specimens. The XRD results are depicted in

Figure 3, reveal that the white substance formed on the specimens is identified as Clinohedrite (CaZn(SiO)

4•H

2O) (Chang et al., 2007). This identification suggests a specific reaction between the ZnO NPs and other components in the paste, leading to the formation of Clinohedrite during the curing process. The presence of this mineral could explain the observed changes in the structural integrity of the specimens. Clinohedrite is a crystalline mineral belonging to the monoclinic crystal system, often found as a coating on fractures. This mineral ranges in color from white to pale and is known for its perfect cleavage and brilliant luster (Copeland & Bragg, 1958). As the amount of ZnO NPs increases, there is a corresponding increase in the formation of clinohedrite. This mineral tends to coat the cement particles, reducing their interaction and affecting the overall structure of the paste.

3.3.2. Morphological Structure by SEM

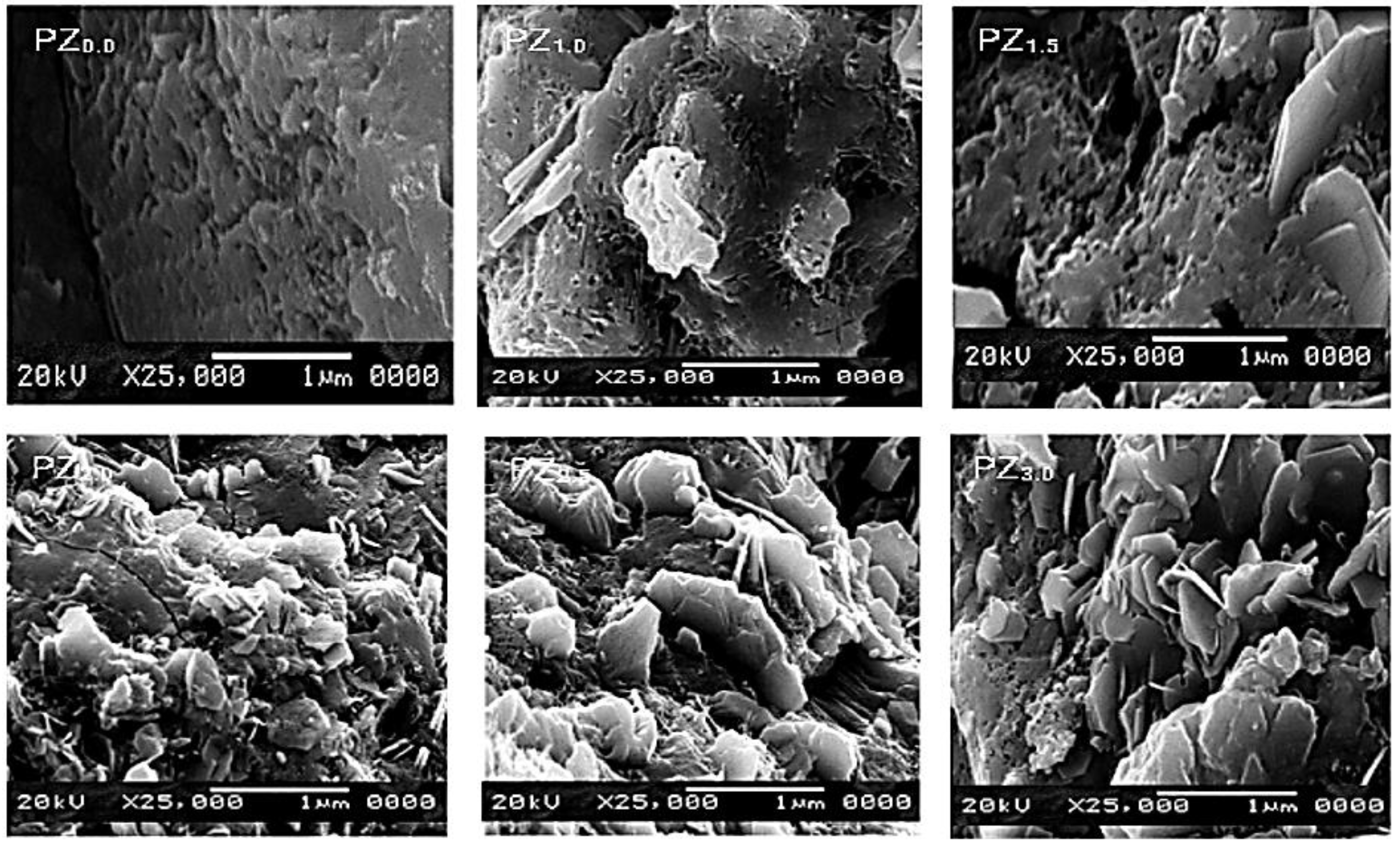

SEM images of cement paste specimens containing varying amounts of ZnO NPs: 0.0%, 1.0%, 1.5%, 2.0%, 2.5%, and 3.0% by weight are presented in

Figure 4. These micrographs highlight the changes in the paste's microstructure with different ZnO NPs concentrations, illustrating the coating

Figure 5 provides SEM micrographs of cement paste specimens with different ZnO NPs (NZ) contents, showcasing the microstructural changes induced by varying NZ concentrations. PZ1.0 illustrates the micrograph of a paste containing 1% NZ. The presence of ZnO NPs results in increased porosity in the specimen. However, PZ1.5 shows the micrograph of a paste with 1.5% NZ. This increased NZ content leads to greater porosity and a less compact structure. Furthermore, PZ2.0 depicts a micrograph of a paste with 2.0% NZ. The specimen shows noticeable cracks and the formation of crystalline layers. PZ2.5 presents the micrograph of a paste with 2.5% NZ. The formation of crystalline layers further increases. PZ3.0 shows the micrograph of a paste with 3.0% NZ. At this concentration, the formation of crystalline layers becomes the predominant feature. These observations indicate that as the ZnO NPs content increases, it significantly impacts the microstructure of the cement paste, leading to increased porosity, reduced compaction, and the formation of crystalline layers, which is particularly evident at higher NZ concentrations.

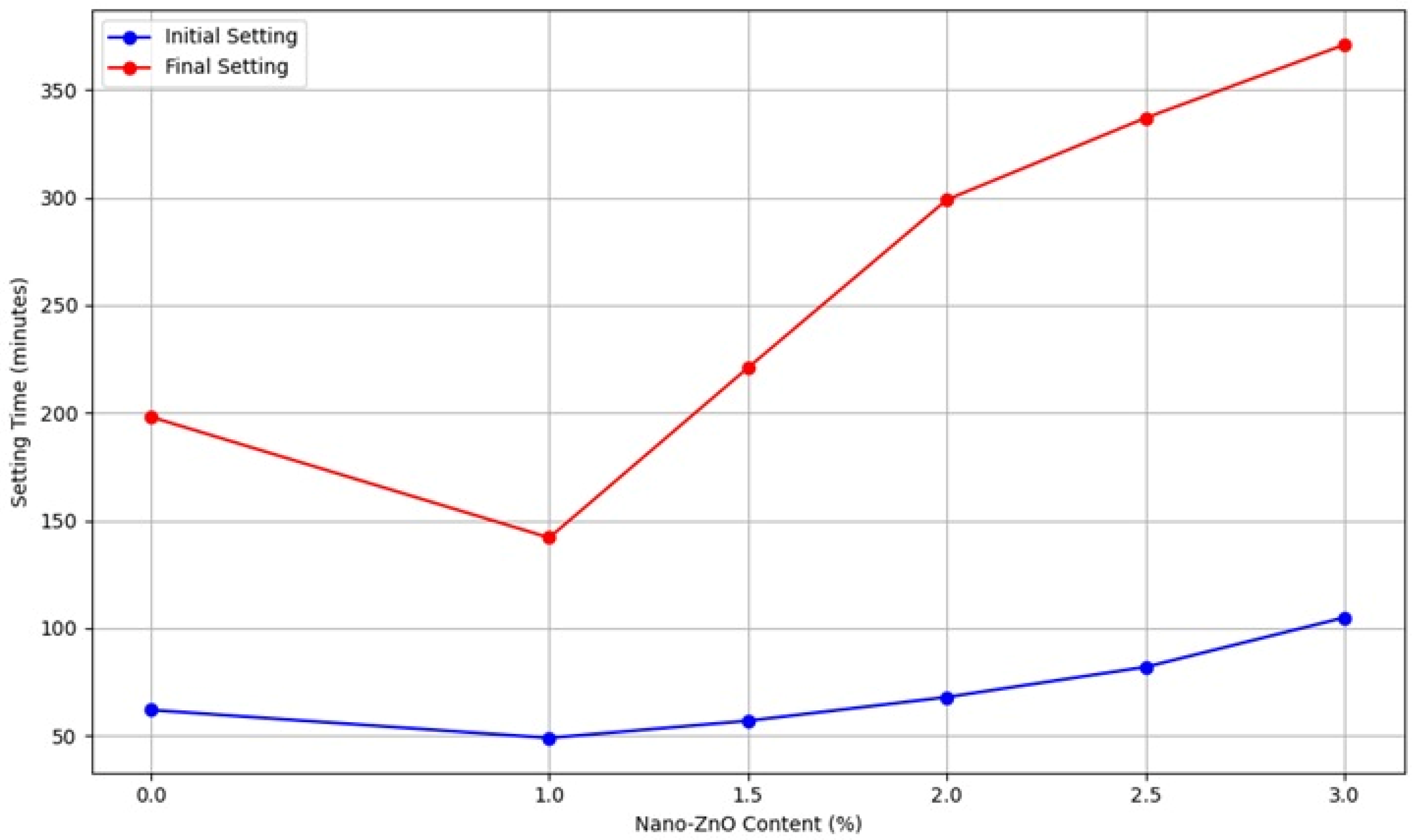

3.3.3. Setting Time

The initial setting time has decreased by 23% and 10% for samples with 1.0% and 1.5% ZnO NPs, respectively, compared to the control. However, as the ZnO NPs content increased to 2.0%, 2.5%, and 3.0%, the initial setting time increased by 8%, 31%, and 69%, respectively. For the final setting time, the sample with 1.0% ZnO NPs showed a reduction of 28% compared to the control. Conversely, with ZnO NPs content of 1.5%, 2.0%, 2.5%, and 3.0%, the final setting time increased by 12%, 51%, 71%, and 88%, respectively. In conclusion, the initial setting time was shortened with 1.0% and 1.5% ZnO NPs but extended with 2.0%, 2.5%, and 3.0% content. The final setting time was reduced with 1.0% ZnO NPs but lengthened with 1.5%, 2.0%, 2.5%, and 3.0%. The study found that adding ZnO NPs to cement paste resulted in longer setting times compared to the control mix. The presence of ZnO generally slows down the hydration process due to forming a structured system at the start of hydration. ZnO NPs inhibited the hydration of tricalcium silicate (C3S) and dicalcium silicate (C2S) in the cement, as evidenced by hydration heat and XRD analysis, resulting in delayed setting times. Furthermore, the curing times for the cement paste increased with the addition of ZnO NPs.

Figure 5 indicates that the delay times of the modified mix are shorter than those of the control.

Figure 5.

Setting time variations with ZnO NPs content (a) initial stetting time and (b) Final stetting time.

Figure 5.

Setting time variations with ZnO NPs content (a) initial stetting time and (b) Final stetting time.

3.3.4. Cubes Curing Behavior

Figure 6 illustrates the behavior of cube cement paste specimens containing ZnO NPs during the curing period. It is observed that the cement paste specimens with ZnO NPs addition exhibited instability when immersed in curing water. This instability is attributed to the formation of a white substance on the surface of the specimens (Adebanjo et al., 2024; Copeland & Bragg, 1958). This white material likely resulted from a reaction between the ZnO NPs and the hydration products of the cement, which compromised the structural integrity of the paste specimens during the curing process. As a result, the specimens collapsed, indicating that the inclusion of ZnO NPs significantly affects the curing behavior and durability of the cement paste.

3.3.5. Heat of Hydration

Figure 7 illustrates how varying ZnO NPs content affects the hydration heat of fresh cement pastes. The data indicates that introducing NZ into the mix reduces the heat values in all specimens compared to the control sample. Precisely, a 3.0% NZ content results in the lowest peak heat value, 7% less than the control specimen. Conversely, a 1.0% NZ content achieves an optimal peak heat value, only 4% lower than the control. The peak hydration heat for all specimens, including the control, occurs approximately 300 and 540 minutes after adding water. Before and after these peak values, the heat release rate remains consistent across all specimens, including the control. This consistency suggests that while NZ content influences the peak heat of hydration, it does not significantly alter the overall heat release rate before or after the peak period.

3.3.6. Workability

Table 4 shows that the average flow diameter decreases as the ZnO NPs content increases. Specifically, the control specimen (MZ0.0) without ZnO NPs has the highest average flow diameter of 182 mm. In contrast, the specimen with 3.0% ZnO NPs (MZ3.0) exhibits the lowest average flow diameter of 117 mm. This reduction in flow diameter with increasing ZnO NPs content suggests a corresponding decrease in the mortar's workability, likely due to the increased viscosity and altered particle interactions within the mix. Our results closer than the previous published results (Gopalakrishnan, Nithiyanantham, & Medicine, 2020; Patil & Dwivedi, 2021).

Furthermore, the results indicate a decrease in spread values with the addition of ZnO NPs (NZ) compared to the control specimen, as illustrated in

Table 6. The average flow diameter of the mortar was reduced by approximately 12%, 17%, 27%, 31%, and 36% for NZ contents of 1.0%, 1.5%, 2.0%, 2.5%, and 3.0%, respectively, relative to the control specimen.

Table 5 summarizes the impact of different ZnO NPs dosages on the flow diameter of cement mortar, expressed as a percentage decrease. A negative percentage indicates a reduction in spread value (Khalaf et al., 2021; J. Liu et al., 2019; Liu, Li, Xu, & Materials, 2015).

4. Conclusions

This study investigated the impact of ZnO NPs on cement-based materials' mechanical performance and microstructural evolution, revealing significant findings. The initial setting time was accelerated with 1.0% and 1.5% ZnO NPs but increased with higher concentrations of 2.0%, 2.5%, and 3.0%. The final setting time decreased with 1.0% ZnO NPs but increased with higher dosages. The inclusion of ZnO NPs also affected the hydration heat, with the highest reduction at 3.0% ZnO NPs. The formation of Clinoherite during curing compromised the structural integrity of the specimens, as revealed by SEM and XRD analyses, leading to increased porosity and reduced compaction at higher ZnO NPs concentrations. Furthermore, mortar workability decreased with increasing ZnO NPs content, attributed to higher viscosity and altered particle interactions. The control specimen had the highest flow diameter, while the 3.0% ZnO NPs specimen had the lowest. This study contributes novel insights into the effects of ZnO NPs on cement properties. It underscores the potential for optimizing ZnO NPs content to enhance cementitious materials' mechanical properties while addressing workability and curing stability challenges. These findings are pivotal for developing high-performance, nano-enhanced construction materials.

5. Recommendations and Future Research

Based on the findings of this study, the incorporation of Zinc Oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) into asphalt and pavement materials presents promising potential for enhancing the mechanical and durability properties of highway pavements. However, further research is needed to optimize their application in pavement design, focusing on long-term performance and practical implementation in real-world highway conditions. The following recommendations and areas for future research are suggested:

Optimal ZnO NPs Dosage in Pavement Materials: The study suggests that ZnO NPs can improve certain mechanical properties, but the optimal dosage for use in asphalt mixtures remains unclear. Future research should focus on determining the ideal concentration of ZnO NPs for enhancing pavement strength, rutting resistance, and cracking resistance without negatively impacting workability or mixture properties. The influence of particle size and dispersion techniques should also be investigated to maximize the benefits of ZnO NPs in highway pavements.

Long-Term Durability in Highway Conditions: While initial tests indicate improvements in mechanical properties, the long-term durability of ZnO NP-enhanced pavements under real-world conditions needs further investigation. It is critical to assess how these modified asphalt mixtures perform under varying climate conditions (e.g., extreme temperatures, freeze-thaw cycles), traffic loads, and exposure to environmental stressors like UV radiation, moisture, and de-icing salts. Long-term field trials are essential to verify the sustainability of these materials for highway pavements.

Impact on Pavement Fatigue and Rutting Resistance: Future research should focus on the effect of ZnO NPs on the fatigue life and rutting resistance of asphalt mixtures used in highways. Laboratory tests, such as the Asphalt Pavement Analyzer (APA) or wheel-tracking tests, could be employed to evaluate how these materials perform under repeated traffic loading. Understanding the influence of ZnO NPs on the resistance of pavements to fatigue cracking and permanent deformation is crucial for improving the performance of high-traffic roadways.

Microstructural and Rheological Behavior of Asphalt with ZnO NPs: In-depth microstructural analysis using techniques like Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and X-ray diffraction (XRD) should be expanded to understand the interactions between ZnO NPs and asphalt binder. Understanding how ZnO NPs affect the binder’s rheological properties, including its viscosity, workability, and aging resistance, is crucial for developing pavements with improved resistance to cracking and rutting. Additionally, it is important to investigate how ZnO NPs interact with other modifiers, such as polymer additives or rejuvenators, to enhance the overall pavement performance.

Pavement Performance in Different Environmental Conditions: Future studies should explore how ZnO NPs impact pavement materials under a range of environmental conditions, including high-temperature climates, areas with heavy rainfall, and regions exposed to freeze-thaw cycles. The effects on moisture susceptibility, thermal cracking, and resistance to aggressive chemical environments (e.g., oils, fuels) should be further examined to assess the material’s applicability in diverse regions with varying climatic conditions.

Synthesis and Dispersion Techniques for ZnO NPs in Pavement Materials: The production and dispersion of ZnO NPs in asphalt binders and mixtures should be refined for large-scale applications. Future research could explore different synthesis methods and dispersion techniques, such as surface functionalization or the use of surfactants, to improve the distribution and stability of ZnO NPs in asphalt. This will ensure uniform performance and reduce the potential for segregation in asphalt mixes.

Sustainability and Cost-Effectiveness: The sustainability of incorporating ZnO NPs into highway pavements must be evaluated, particularly in terms of environmental impact and cost-effectiveness. Life cycle assessments (LCA) should be conducted to compare the environmental benefits of ZnO NP-modified pavements, including reduced maintenance needs and extended service life, against the costs of producing and incorporating the nanoparticles into the mix. Research into the economic feasibility of scaling up this technology for widespread highway use is essential.

Influence on Pavement Smoothness and Skid Resistance: Future research should also examine the influence of ZnO NPs on the surface properties of pavements, such as skid resistance and smoothness. It is important to evaluate whether these nanoparticles affect the frictional properties of the surface, particularly under wet conditions, to ensure safety for highway users. Additionally, studies on the workability of the mixture and the ease of achieving desired surface textures during construction should be conducted.

Testing and Validation in Field Conditions: Laboratory results need to be validated through extensive field testing. Long-term monitoring of pilot projects and test sections incorporating ZnO NP-modified pavements will provide valuable data on their actual performance in real-world conditions. This includes tracking factors such as rut depth, crack development, and smoothness over time to confirm laboratory predictions and identify potential issues that may arise under actual traffic loading and environmental stresses.

Development of Pavement Design Models: Incorporating ZnO NP-modified materials into existing pavement design frameworks (such as the AASHTO 93 design guide or mechanistic-empirical methods) is essential. Future studies should aim to refine design models that integrate the properties of these modified asphalt mixtures, accounting for factors such as traffic loads, environmental conditions, and material behavior over time.

By addressing these recommendations, further research can optimize the use of ZnO NPs in highway pavement design, leading to more durable, sustainable, and cost-effective road infrastructure that meets the demands of modern transportation systems.

Author Contributions

A.A. Assolie and A. H. E. SALAMA. conceptualized and designed the study. A.A. Assolie and A. H. E. SALAMA were responsible for data collection and analysis.All authors contributed to writing and revising the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Ethical Approval

This study was conducted in accordance with ethical standards and approved by the relevant ethical committee.

Consent to Participate

All participants involved in the study provided informed consent prior to participation.

Consent to Publish

All authors have provided consent for the publication of this manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this manuscript.

References

- Abdallah, M., Al-Tamimi, W., Salameh, A., & Alamir, S. J. J. J. o. C. E. (2022). Performance, Measurements, And Potential Radiological Risks Of Natural Radioactivity In Cements Used In Jordan. 16(1).

- Abo-El-Enein, S.; El-Hosiny, F.; El-Gamal, S.; Amin, M.; Ramadan, M. Gamma radiation shielding, fire resistance and physicochemical characteristics of Portland cement pastes modified with synthesized Fe2O3 and ZnO nanoparticles. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 173, 687–706. [CrossRef]

- Adebanjo, A. U., Abbas, Y. M., Shafiq, N., Khan, M. I., Farhan, S. A., Masmoudi, R. J. C., & Materials, B. (2024). Optimizing nano-TiO2 and ZnO integration in silica-based high-performance concrete: Mechanical, durability, and photocatalysis insights for sustainable self-cleaning systems. 446, 138038.

- Al-Kheetan, M. J., Jweihan, Y. S., Rabi, M., & Ghaffar, S. H. J. B. (2024). Durability Enhancement of Concrete with Recycled Concrete Aggregate: The Role of Nano-ZnO. 14(2), 353.

- Alhudhaibi, A. M., Ragab, S. M., Sharaf, M., Turoop, L., Runo, S., Nyanjom, S.,... Synthesis. (2024). Effect of ex situ, eco-friendly ZnONPs incorporating green synthesised Moringa oleifera leaf extract in enhancing biochemical and molecular aspects of Vicia faba L. under salt stress. 13(1), 20240012.

- Amor, F.; Baudys, M.; Racova, Z.; Scheinherrová, L.; Ingrisova, L.; Hajek, P. Contribution of TiO2 and ZnO nanoparticles to the hydration of Portland cement and photocatalytic properties of High Performance Concrete. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 16. [CrossRef]

- Arefi, M. R., & Rezaei-Zarchi, S. J. I. j. o. m. s. (2012). Synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles and their effect on the compressive strength and setting time of self-compacted concrete paste as cementitious composites. 13(4), 4340-4350.

- Arliguie, G.; Grandet, J. Influence de la composition d'un ciment portland sur son hydration en presence de zinc. Cem. Concr. Res. 1990, 20, 517–524. [CrossRef]

- ASTM, C. J. U. S. A. I. (1998). 187-98. Standard Test Method for Normal Consistency of Hydraulic Cement. 11(1).

- Bauer, E.; de Sousa, J.G.; Guimarães, E.A.; Silva, F.G.S. Study of the laboratory Vane test on mortars. Build. Environ. 2007, 42, 86–92. [CrossRef]

- Behfarnia, K., Azarkeivan, A., & Keivan, A. (2013). The effects of TiO2 and ZnO nanoparticles on physical and mechanical properties of normal concrete.

- Chang, T.-P.; Shih, J.-Y.; Yang, K.-M.; Hsiao, T.-C. Material properties of portland cement paste with nano-montmorillonite. J. Mater. Sci. 2007, 42, 7478–7487. [CrossRef]

- Copeland, L. E., & Bragg, R. H. J. A. C. (1958). Quantitative X-ray diffraction analysis. 30(2), 196-201.

- Ghafari, E.; Ghahari, S.; Feng, Y.; Severgnini, F.; Lu, N. Effect of Zinc oxide and Al-Zinc oxide nanoparticles on the rheological properties of cement paste. Compos. Part B: Eng. 2016, 105, 160–166. [CrossRef]

- Gomide, R. A. C., de Oliveira, A. C. S., Rodrigues, D. A. C., de Oliveira, C. R., de Assis, O. B. G., Dias, M. V.,... Environment, t. (2020). Development and characterization of lignin microparticles for physical and antioxidant enhancement of biodegradable polymers. 28, 1326-1334.

- Gopalakrishnan, R.; Nithiyanantham, S. Effect of ZnO Nanoparticles on Cement Mortar for Enhancing the Physico-Chemical, Mechanical and Related Properties. Adv. Sci. Eng. Med. 2020, 12, 348–355. [CrossRef]

- Heikal, M., Nassar, M., El-ALeem, A., El-Sharkawy, A., Desoki, E.-H., & M Ibrahim, S. J. B. J. o. A. S. (2022). Performance of composite cement containing Nano-ZnO subjected to elevated temperature. 7(12), 115-130.

- Khalaf, M.A.; Cheah, C.B.; Ramli, M.; Ahmed, N.M.; Al-Shwaiter, A. Effect of nano zinc oxide and silica on mechanical, fluid transport and radiation attenuation properties of steel furnace slag heavyweight concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 274. [CrossRef]

- Korayem, A.; Tourani, N.; Zakertabrizi, M.; Sabziparvar, A.; Duan, W. A review of dispersion of nanoparticles in cementitious matrices: Nanoparticle geometry perspective. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 153, 346–357. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Jin, H.; Gu, C.; Yang, Y. Effects of zinc oxide nanoparticles on early-age hydration and the mechanical properties of cement paste. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 217, 352–362. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, Q.; Xu, S. Influence of nanoparticles on fluidity and mechanical properties of cement mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 101, 892–901. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.-H.; Hao, N.; Shinde, S.; Pu, Y.; Kang, X.; Ragauskas, A.J.; Yuan, J.S. Defining lignin nanoparticle properties through tailored lignin reactivity by sequential organosolv fragmentation approach (SOFA). Green Chem. 2018, 21, 245–260. [CrossRef]

- Nochaiya, T.; Sekine, Y.; Choopun, S.; Chaipanich, A. Microstructure, characterizations, functionality and compressive strength of cement-based materials using zinc oxide nanoparticles as an additive. J. Alloy. Compd. 2015, 630, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Olmo, I.F.; Chacon, E.; Irabien, A. Influence of lead, zinc, iron (III) and chromium (III) oxides on the setting time and strength development of Portland cement. Cem. Concr. Res. 2001, 31, 1213–1219. [CrossRef]

- Österberg, M.; Sipponen, M.H.; Mattos, B.D.; Rojas, O.J. Spherical lignin particles: a review on their sustainability and applications. Green Chem. 2020, 22, 2712–2733. [CrossRef]

- Patil, H.; Dwivedi, A. Impact of nano ZnO particles on the characteristics of the cement mortar. Innov. Infrastruct. Solutions 2021, 6, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Rong, Z., Zhao, M., & Wang, Y. J. M. (2020). Effects of modified nano-SiO2 particles on properties of high-performance cement-based composites. 13(3), 646.

- Shafeek, A.M.; Khedr, M.H.; El-Dek, S.I.; Shehata, N. Influence of ZnO nanoparticle ratio and size on mechanical properties and whiteness of White Portland Cement. Appl. Nanosci. 2020, 10, 3603–3615. [CrossRef]

- Sharaf, M., Mohammed, E. J., Farahat, E. M., Alrehaili, A. A., Alkhudhayri, A., Ali, A. M.,... AlHarbi, M. J. M. R. (2023). Biocide syntheses bee venom-conjugated ZnO@ αFe2O3 nanoflowers as an advanced platform targeting multidrug-resistant fecal coliform bacteria biofilm isolated from treated wastewater. 14(4), 1489-1510.

- Sharaf, M.; Sewid, A.H.; Hamouda, H.I.; Elharrif, M.G.; El-Demerdash, A.S.; Alharthi, A.; Hashim, N.; Hamad, A.A.; Selim, S.; Alkhalifah, D.H.M.; et al. Rhamnolipid-Coated Iron Oxide Nanoparticles as a Novel Multitarget Candidate against Major Foodborne E. coli Serotypes and Methicillin-Resistant S. aureus. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e0025022. [CrossRef]

- Singh, N. Properties of cementitious systems in presence of nanomaterials. Mater. Today: Proc. 2020, 29, 1143–1149. [CrossRef]

- Slapø, F., Kvande, T., Høiseth, K., Hisdal, J., & Lohne, J. J. M. I. (2018). Mortar water content impact on masonry strength. 30, 91-98.

- Standard, A. (1998). C187. Standard Test Method for Normal Consistency of Hydraulic Cement. In: American Society for Testing and Materials: Philadelphia, PA.

- STN, E. J. S. O. o. S., Metrology, & Testing: Bratislava, S. (2017). 196-3. Methods of Testing Cement—Part 3: Determination of Setting Times and Soundness.

- Voicu, G.; Tiuca, G.-A.; Badanoiu, A.-I.; Holban, A.-M. Nano and mesoscopic SiO2 and ZnO powders to modulate hydration, hardening and antibacterial properties of portland cements. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 57. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lu, H.; Wang, J.; He, H. Effects of Highly Crystalized Nano C-S-H Particles on Performances of Portland Cement Paste and Its Mechanism. Crystals 2020, 10, 816. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zheng, K.; Liu, Z.; He, F. Chemical effect of nano-alumina on early-age hydration of Portland cement. Cem. Concr. Res. 2019, 116, 159–167. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).