1. Introduction

The Spondylarthritis group of diseases, which include ankylosing spondylitis (AS) and psoriatic arthritis (PsA), are characterized by chronic inflammation affecting the axial skeleton and/or the peripheral joints. Axial Spondylarthritis (AxSpA) includes the pathologies that mainly affect the axial skeleton, thus determining acute and chronic modifications of the spine and sacroiliac joints. These conditions predispose individuals to osteoporosis due to local and systemic inflammation, mostly driven by increased secretion of proinflammatory cytokines, which can lead to pathological activation of osteoclasts and altered biomechanics that lead to reduced mobility. A meta-analysis revealed that the prevalence of osteoporosis in SpA varies by a large margin (from 18,7% to 62%), suggesting the need for research covering other diagnostic methods [

1].

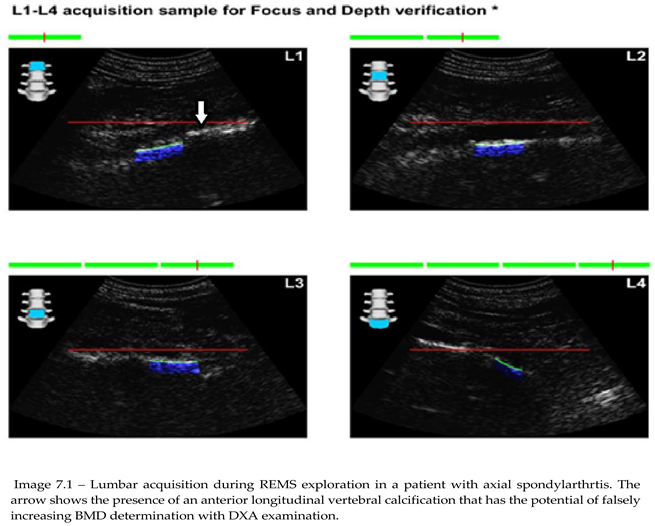

DXA is a cornerstone in osteoporosis diagnosis, measuring bone mineral density (BMD) mainly at the lumbar spine and hip sites. An advantage of DXA scans is the possibility of distal radio-ulnar scan when hip scans can’t be performed (e.g., total hip replacement). The learning curve for performing DXA scans is very permissible, especially in recent years, when technology and the use of AI augments the tracing done by medical technicians. In SpA patients, syndesmophytes, vertebral fusion, and calcifications can falsely elevate BMD readings measured with DXA, significantly complicating osteoporosis detection [

2]. This overestimation can be present in spite of performant machinery and smart detection boosted by AI. This points to the urgent need for alternative imaging methods, such as quantitative computed tomography (qCT), which can provide volumetric BMD (g/cm³), but are associated with higher radiation exposure and limited availability [

3]. Additionally, qCT can be influenced by spinal deformities and other abnormalities common in SpA patients, making it less reliable in these cases [

4]. Radiofrequency Echographic Multispectrometry (REMS) offers a promising alternative, utilizing ultrasound to assess bone quality and microarchitecture without the limitations of DXA and qCT. In recent years this technique has been updated to provide evaluation of peripheral sites, such as the radius or tibia, avoiding interference from axial skeletal artifacts [

5]. Furthermore, REMS assesses bone elasticity, stiffness, and microarchitectural integrity, providing a broader evaluation of bone health than BMD alone [

6]. Additionally the fragility score (FS) included in REMS scans is a marker for bone fragility that is independent of BMD value. Compared to DXA, REMS is more difficult to master, requiring either a physician with good knowledge of ultrasound-driven imagistic methods or a good knowledge of pathologies affecting the spine. Although it mainly takes about 8 minutes for a complete evaluation of both spine and hip density, scanning time can be influenced by multiple factors such as: intestinal gas, thick abdominal wall due to obesity and severe spinal deformities.

2. Pathophysiology of Osteoporosis in Spondylarthritis

Osteoporosis in spondylarthritis (SpA) is a multifactorial process driven primarily by chronic systemic inflammation, which profoundly alters bone homeostasis. The pathological mechanisms underlying osteoporosis in SpA involve an intricate interplay between inflammatory cytokines, bone remodeling disruptions, biomechanical alterations, and metabolic factors.

Chronic inflammation serves as the primary driver of bone loss in SpA, mediated by the excessive production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), and interleukin-17 (IL-17). These cytokines promote osteoclastogenesis through the upregulation of receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-Β ligand (RANKL) while simultaneously suppressing osteoprotegerin (OPG), a key regulator that inhibits osteoclast differentiation. The resulting imbalance leads to increased osteoclast activity and increased bone resorption, ultimately reducing bone mineral density (BMD) and predisposing individuals to a higher risk of fragility fractures.

Furthermore, TNF-α and IL-17 directly interfere with osteoblast differentiation, activation and function by inhibiting the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, a pathway of increased importance for bone formation. These cytokines also stimulate the production of Dickkopf-1 (DKK-1) and sclerostin, both of which are potent inhibitors of osteoblast-mediated bone formation. This dual effect of enhanced resorption and impaired formation accelerates bone loss in SpA patients.

A hallmark of SpA is the paradoxical coexistence of osteoporosis and aberrant new bone formation. Chronic inflammation at the vertebral entheses promotes the deposition of mineralized tissue, leading to calcification of spinal ligaments and the development of syndesmophytes. This process results from a pathological shift in mesenchymal progenitor cell differentiation, favoring osteoproliferation over osteoblastogenesis. The formation of intervertebral bridges and ankylosis further alters the mechanical loading of the spine, leading to compensatory bone loss in adjacent skeletal regions. This disrupted biomechanical environment contributes to trabecular microarchitecture deterioration and increased fracture susceptibility, particularly in the vertebrae.

Pain and stiffness associated with SpA frequently result in reduced physical activity, which is a critical determinant of bone health. Mechanical loading plays an essential role in maintaining bone density through the stimulation of osteocytes and the regulation of bone remodeling processes. In the absence of adequate mechanical stimuli, osteoclast activity predominates, leading to disuse osteoporosis and an elevated risk of fractures.

Additionally, pharmacological management of SpA often involves glucocorticoids, which exacerbate bone loss through multiple mechanisms. Glucocorticoids directly stimulate osteoclastogenesis while inhibiting osteoblast proliferation and differentiation. They also promote calcium resorption from bone, reduce intestinal calcium absorption, and increase renal calcium excretion, leading to secondary hyperparathyroidism and further bone demineralization. The cumulative effect of long-term glucocorticoid therapy significantly heightens the risk of osteoporosis in SpA patients.

Vitamin D deficiency is highly prevalent in individuals with SpA and represents an additional compounding factor in osteoporosis pathogenesis. Vitamin D plays a crucial role in calcium homeostasis, facilitating intestinal calcium absorption and maintaining adequate serum calcium levels necessary for bone mineralization. Deficient vitamin D levels not only impair these processes but also contribute to systemic inflammation by modulating immune responses. Reduced vitamin D availability leads to elevated levels of parathyroid hormone (PTH), which further accelerates bone resorption, compounding the inflammatory-driven bone loss seen in SpA. Moreover, vitamin D is involved in muscle health and strength, being associated with a higher risk of falls and fractures in patients with a deficiency of this micronutrient.

3. Principles of Radiofrequency Echographic Multispectrometry

REMS employs high-frequency ultrasound to analyze bone tissue's elastic and structural properties. Unlike DXA, which measures areal BMD, REMS captures multi-spectral data, providing a comprehensive assessment of bone quality. The method works by analyzing the propagation of ultrasound waves through bone tissue, measuring properties such as elasticity and bone mineralization, which are critical determinants of bone strength. Several key parameters are measured in REMS:

Bone Mineral Density (BMD): An estimate of bone mineral content, similar to DXA but with the added advantage of assessing peripheral sites.

Elastic Modulus (E): Reflects bone stiffness and fracture resistance, a crucial factor in understanding bone fragility.

Microarchitectural Integrity: Evaluates the trabecular and cortical bone components, critical for understanding bone's structural stability and its ability to resist fracture.

REMS has demonstrated superior sensitivity in detecting bone quality changes compared to traditional DXA, particularly in populations with axial skeletal involvement [

12]. While DXA remains the gold standard for assessing areal BMD, REMS provides a more holistic evaluation by integrating both quantitative and qualitative data about bone health. The ability to assess bone quality, such as microarchitecture, helps in predicting fracture risk more accurately than BMD measurements alone, especially in individuals with normal or only mildly reduced BMD [

13].

4. Advantages of REMS in SpA Patients

Unlike DXA and qCT, REMS involves no radiation, making it safer for repeated use, especially in younger patients or those requiring frequent monitoring, as well as examination in pregnant women [

14]. By assessing sites like the radius or tibia, REMS avoids the confounding effects of syndesmophytes and calcifications in the axial skeleton. In one study, the diagnostic accuracy of REMS was found to be significantly better than DXA in SpA patients with vertebral deformities and calcifications [

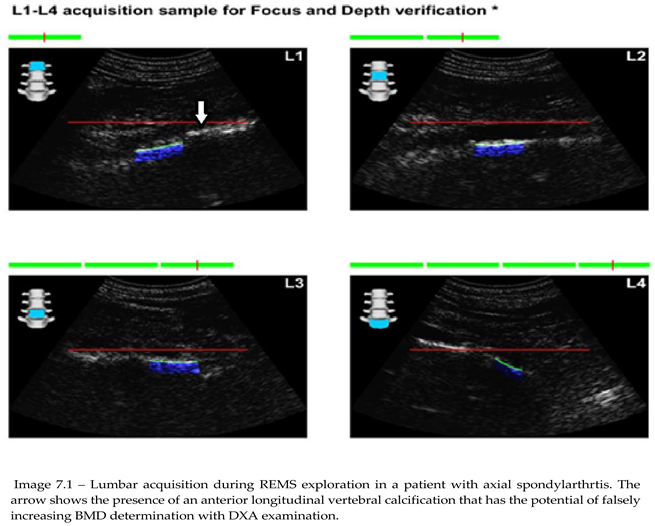

15]. Moreover, REMS recognizes extraskeletal calcifications (aortic, ligamentous, etc.), which may influence the interpretation of other imaging results [

16]. This unique feature allows REMS to provide a more accurate reflection of bone health, particularly in conditions like SpA, where axial skeleton abnormalities can complicate traditional bone density assessments.

REMS evaluates bone quality metrics such as stiffness and microarchitecture, providing a more complete understanding of fracture risk compared to BMD alone. Recent studies have shown that in patients with axial SpA, REMS can identify bone deterioration and fracture risk even when DXA fails to detect osteoporosis due to spinal deformities [

17]. Additionally, REMS devices are compact and suitable for outpatient or bedside settings, improving access to osteoporosis diagnostics. A study conducted in rural and remote regions demonstrated the feasibility and cost-effectiveness of using portable REMS devices in diagnosing osteoporosis and monitoring treatment efficacy [

18].

5. Evidence Supporting REMS in Osteoporosis Diagnosis

Multiple studies have demonstrated REMS's strong correlation with DXA-derived T-scores, confirming its reliability in detecting osteoporosis. For example, a 2022 study by Di Iorio et al. showed high concordance between REMS and DXA results in rheumatoid arthritis patients, a population with similar inflammatory and structural challenges for peripheral sites [

19]. REMS's ability to assess bone quality enhances fracture risk prediction. A 2021 meta-analysis found that REMS detected microarchitectural abnormalities in patients with fractures but normal DXA T-scores, emphasizing its role in identifying high-risk individuals who might otherwise be missed [

20]. In SpA-specific studies, REMS has demonstrated superior diagnostic accuracy in detecting osteoporosis, particularly in patients with syndesmophyte-related BMD artifacts. Braga et al reported that REMS identified osteoporosis in 35% of SpA patients who were misclassified as normal by DXA [

21]. This ability to detect osteoporosis despite normal BMD readings has significant clinical implications, as it helps identify individuals at high fracture risk who would benefit from early intervention.

Additionally, REMS has been shown to monitor the effectiveness of therapeutic interventions more accurately than DXA. In one longitudinal study, SpA patients receiving anti-TNF therapy had significant improvements in REMS-derived bone stiffness scores, even when DXA showed no significant changes in BMD [

22]. This suggests that REMS is more sensitive to changes in bone quality that may not be reflected in traditional BMD measurements.

While the studies supporting REMS as a valuable tool for osteoporosis detection and monitoring present compelling evidence, several limitations must be acknowledged. Many of these studies have relatively small sample sizes, which may limit the generalizability of their findings across broader patient populations. Additionally, the majority of REMS research has focused on specific patient cohorts, such as individuals with rheumatoid arthritis or SpA, raising concerns about its applicability to the general population. Variability in study methodologies, including differences in REMS protocols, measurement sites, and reference standards, also presents challenges in directly comparing results across studies. Furthermore, the lack of long-term follow-up data means that REMS's predictive value for fracture risk over extended periods remains uncertain. Given these limitations, further large-scale, multicenter studies with standardized methodologies and longitudinal assessments are needed to fully establish REMS's role in osteoporosis management.

6. Integrating REMS into Clinical Practice

REMS should be incorporated into osteoporosis screening for SpA patients, especially those with inconclusive or artifact-prone DXA results. It can serve as a first-line tool in primary care settings or as a confirmatory test following DXA. A recent survey of rheumatologists indicated that REMS was highly regarded for its ability to provide accurate assessments of bone health in SpA patients, particularly in settings where DXA results may be ambiguous due to spinal involvement [

23]. As of now, REMS is used along with DXA for diagnosis and follow-up after treatment initiation in many countries, including Italy, the USA, and Japan [

24]. REMS's ability to detect subtle changes in bone quality makes it valuable for monitoring therapeutic responses, such as improvements following biological therapy (Denosumab) or anti-resorptive agents (bisphosphonates) [

25]. In clinical practice, the integration of REMS with DXA may allow for a more personalized approach to osteoporosis management, particularly in SpA patients, as well as monitoring the impact of csDMARDs and bDMARDs on bone health due to its practicality and repeatability.

Although initial costs may be higher, REMS's portability and lack of radiation may offset expenses associated with repeated DXA or advanced imaging techniques. A cost-effectiveness analysis conducted in 2023 demonstrated that REMS reduced the overall healthcare burden in SpA management, particularly by reducing the need for repeat imaging and enabling earlier diagnosis of osteoporosis [

26]. Future advancements in REMS technology may further expand its clinical applications, including its integration with biomarkers of bone turnover to enhance predictive accuracy for fractures and guide therapy initiation [

27].

All the apparent benefits of using REMS are shadowed by a series of disadvantages that reduce its use. Among these we want to point out:

Limited Availability and Accessibility – REMS technology is not yet widely available in all healthcare facilities, potentially limiting its adoption, especially in resource-constrained settings [

28].

Operator Dependence – While REMS is less operator-dependent than DXA, variability in technique and interpretation among different users may still impact diagnostic accuracy. A skilled physician with good knowledge of ultrasound imaging is usually required to obtain the correct frames of evaluation and interpretation of results [

29].

Lack of Standardization – REMS is a relatively new technology, and its clinical guidelines, reference ranges, and validation across diverse populations are still evolving, making widespread adoption challenging. Although it is included in standard clinical practice in Italy, further confirmation from studies on different populations is needed [

30].

Comparability with DXA – Since DXA is the gold standard for osteoporosis diagnosis, transitioning to REMS requires establishing comparability, which may involve additional validation studies and regulatory approvals. In some regions (e.g., Romania), there is a high level of doubt regarding REMS and its probable inclusion in standard clinical practice [

31].

Reimbursement and Cost Concerns – Insurance coverage for REMS assessments may be limited, and initial costs for device acquisition and training could be barriers for healthcare institutions [

32].

Limited Longitudinal Data – Long-term studies on REMS efficacy in monitoring osteoporosis progression and evolution under treatment are still ongoing, making it difficult to determine its full applicability in clinical practice [

28,

32].

7. Objectives

The present study aims to point out the main capabilities of REMS compared to DXA in patients with SpA. The primary objective is to determine whether REMS has a higher sensibility in detecting mineral bone loss specifically for the lumbar spine, in regards to the presence of syndesmophytes or calcification of longitudinal vertebral ligaments compared to DXA scans. Secondary objectives are aimed at classifying the type of bone “age” individuals with SpA have, compared to control groups comprised of patients without the presence of any inflammatory systemic disease or bone resorbing therapies.

8. Materials and Methods

A transversal observational with minimal intervention study was performed in order to evaluate the usefulness of REMS in diagnosing osteoporosis in individuals with Axial Spondylarthritis (AxSpA). The diagnosis of AxSpA is based on the ASAS classification criteria for AxSpA approved in 2006 by the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) and the American College of Rheumatology (ACR). A total of 76 patients with AxSpA were enrolled (63 under the age of 45 and 13 above the age of 45), as well as 535 individuals in the control group (162 under 45 years and 373 above 45 years of age). The enrollment period and data gathering period was between May 2020 and August 2023. The main inclusion criteria are represented by:

Confirmed diagnosis of AxSpA based on ASAS classification criteria;

No former or present anti-osteoporotic or any Disease Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drug (DMARD) treatment that can influence bone metabolism;

Had a recent DXA scan done (less than a month) or will perform one in the future (less than a month) through recommendation from a rheumatology physician based on clinical judgement;

DXA scans performed for L1-L4 lumbar vertebrae and hips;

Front and profile lumbar spine x-rays done in the same year – as normal follow-up investigations.

Exclusion criteria include:

ther comorbidities or medications that influence bone metabolism (e.g. Cushings syndrome, endocrine disorders, glucocorticoid therapy, antidepressive treatment etc.);

No medical recommendation for DXA scan;

Patients under biological DMARDs;

Patients under classical synthetic DMARDs;

No imagistics of the lumbar spine.

DXA scans were performed in different diagnostic centers based on medical recommendations. REMS scans were done in two centers, at Dr. I. Cantacuzino Hospital Bucharest and at Osteodensys private clinic in Bucharest by trained professionals. The anatomical regions examined were the classical ones: the lumbar spine (L1-L4) and the femoral neck bilaterally. Since the main objective of the study was to identify possible differences between the control group and patients with SpA and imagistic modifications of the spine, frontal and profile X-rays have been performed before any BMD measurement, with the main focus of describing the presence of syndesmophytes. Additionally, standard lab tests, including vitamin D testing, were performed.

Statistical analysis was done using Minitab version 20.3.0, using t-tests for independent variables, Mann-Whitney U-tests, and one-way ANOVA to compare the study groups. Tables and figures were made in Microsoft Excel. Although the manuscript is fully written by the author, for clarity, Grammarly AI was used to make grammatical corrections of the text.

9. Results

After acquisition of data, values of BMD, BMI, FS, and baseline vitamin D levels (where it was available) were distributed depending on age groups in quartiles of 10 years. Time of analysis for REMS was noted for every patients and compared to a mean value of 15 minutes that are usually required for DXA scans, not taking into consideration the time lost with patients requiring appointments and time lost for transit.

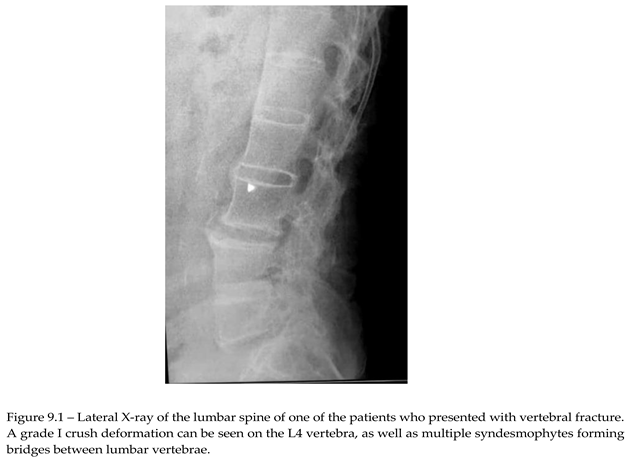

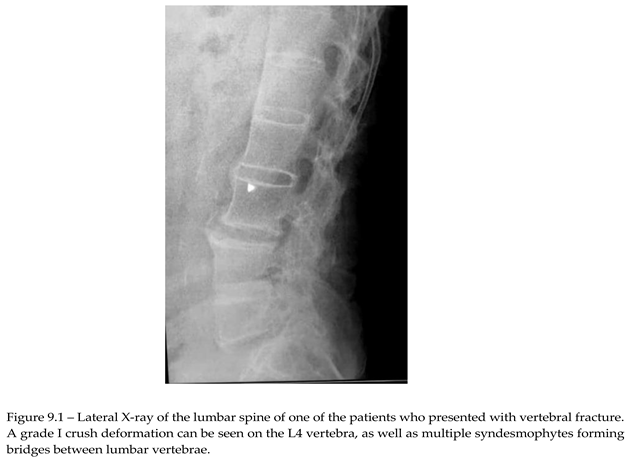

Of the 76 patients with SpA that presented for REMS evaluation, 2 had recent vertebral fracture, one classified as grade I wedge modification on the Genant scale affecting T8 vertebra. Imagistics done during clinical practice for these patients didn’t show any structural modification related to AxSpA. The other patient had a grade I crush deformity on L4 vertebra, X-ray showing multiple syndesmophytes in the lumbar area (Image 9.1).

First and foremost, REMS acquisition was faster than that of DXA, given the device's portability. The mean time of acquisition for REMS was about 14.5 minutes, which can be done in the physician consultation room, compared to DXA, which had a mean acquisition time of about 15 minutes (2-sample T-test; p<0.005). DXA also requires special measures to ensure the safety of the patient and the technician performing the examination. In addition, and this was related strictly to the study conditions, the patients weren’t able to do DXA scans in the two locations where enrollment was done since neither had the hardware required, thus prolonging the theoretical time for acquisition to more than 15 minutes.

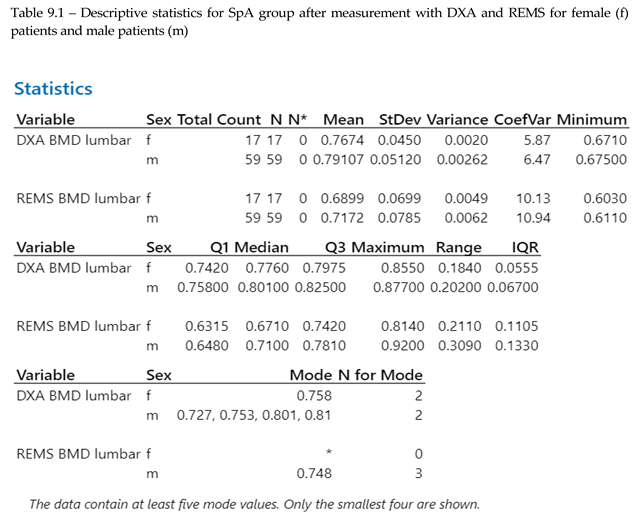

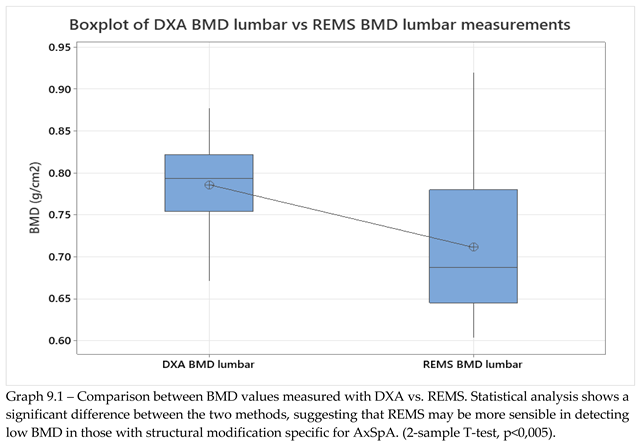

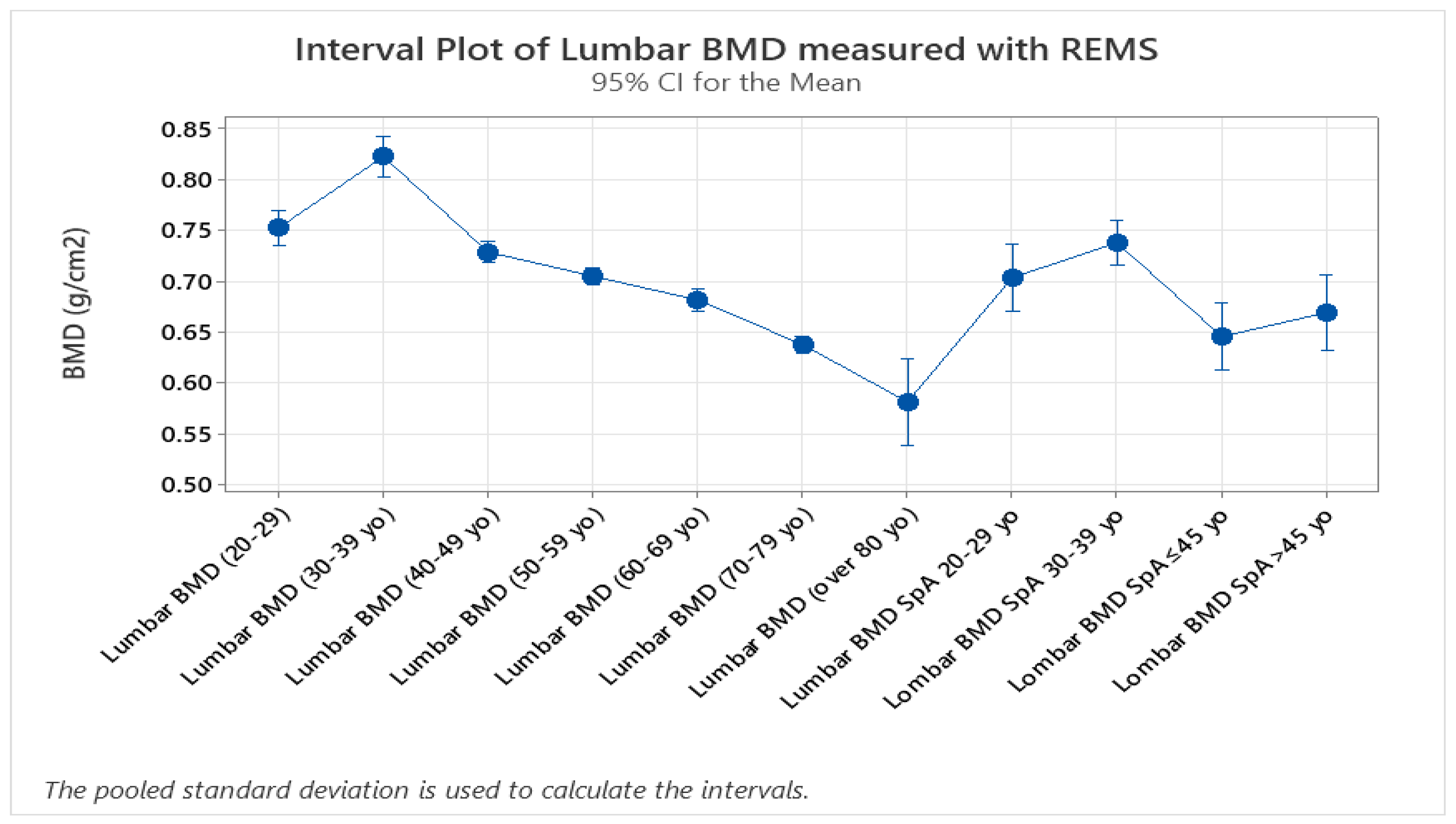

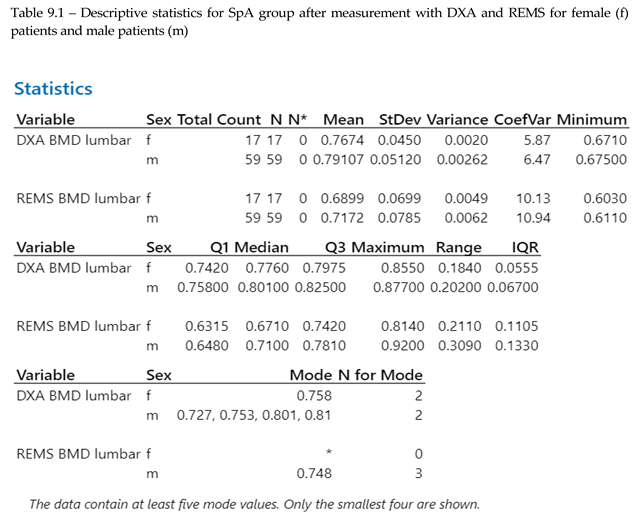

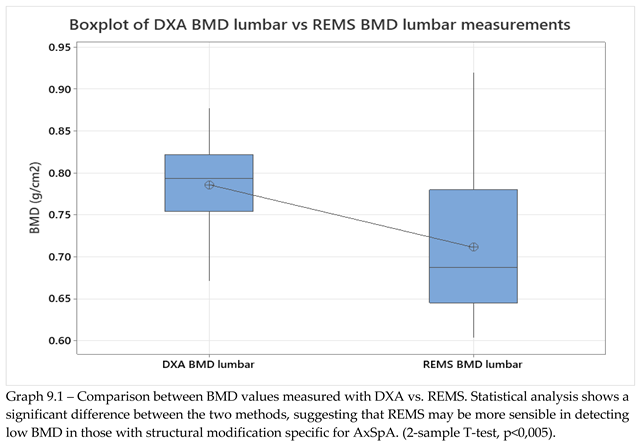

BMD data from lumbar analysis was compared between the control group and the SpA group by using 2-sample T-test/Whelch (graph 9.1, p<0.005), showing a significant difference between BMD mean values measured with DXA vs REMS. The result obtained is in concordance with data found in literature regarding the higher incidence of osteoporosis in patients with SpA.

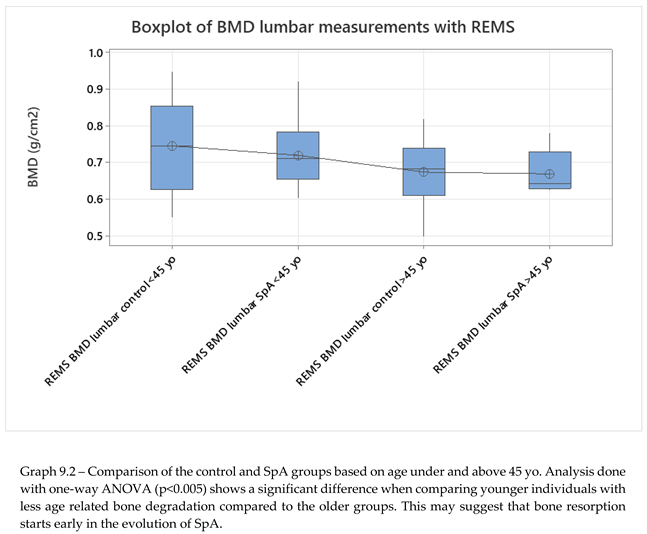

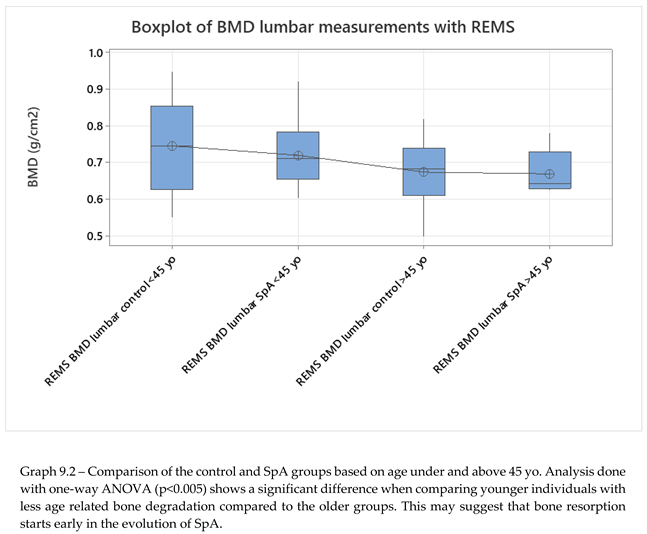

No significant differences were seen when comparing hip sites, neither in regards to DXA vs REMS analysis, nor between the control group and SpA group after REMS measurement (2-sample T-test, p<0.005). We analyzed the differences between younger (under 45 yo) and older individuals (over 45 yo), comparing their BMD values measured with REMS (graph 9.2), where we found that younger patients with SpA have lower BMD values compared to their equivalent age controls. This might suggest that bone loss is present from the onset of the disease and can go unrecognized until classification criteria are met. This finding can explain the two patients described anteriorly that presented directly with vertebral fractures, with no other clinical manifestations suggestive of SpA.

The study groups were further divided into age groups (quartiles of 10 years, Graph 8.3, 2-sample T-test, p<0.), and one-way ANOVA test for variance was applied to the study groups, showing a clear difference between spine BMD values and classifying values of patients with SpA as having the same bone density values as the control group with ages between 40-49 years old. This might suggest that bone resorbtion due to chronic SpA starts in early stages of the disease. Overall SpA individuals showed lower BMD values compared to the specific age groups (Graph 9.3).

Graph 9.1.

– Difference between DXA scans and REMS scans in patients with SpA.

Graph 9.1.

– Difference between DXA scans and REMS scans in patients with SpA.

Additionally, vitamin D deficiency was more frequent in older patients with SpA with long-standing disease compared to their specific age group, with p<0.005 based on one-way ANOVA testing comparing all age groups.

10. Discussion

The results further confirm the scientific literature data that underscores the risk of osteoporosis in patients with SpA. Furthermore, a statistical analysis comparing DXA and REMS techniques has shown that REMS has a slightly higher sensibility in detecting bone demineralization in patients with chronic axial involvement, making this a reliable tool for clinical use, also given its lower financial stress on public health systems. This opens up the possibility of monitoring either osteoporotic-specific treatments or DMARD treatments in specific inflammatory rheumatic diseases of the spondylarthritides group. These results might primarily stem from the ability of the method to discern between bone and other calcifications related to a multitude of pathologies. Moreover, although both methods offer results in 2D (g/cm2), the flexibility in examining vertebral sites by angulation of the transducer and orienting ultrasound waves towards the area of interest may provide options for avoiding large calcifications or other artifact-generating conditions. Thorough preparation is needed to do REMS on the lumbar spine since improper dietary habits might lead to excessive gas accumulation in the bowels that act as an ultrasonic shield, dispersing sound waves and invalidating the examination.

Multicenter trials on diverse populations from different geographical ares and of diverse ethnicities are needed to validate REMS's diagnostic thresholds and fracture risk prediction capabilities across diverse populations, including patients with SpA and other inflammatory rheumatic diseases.

Combining REMS data with biomarkers of bone turnover or inflammatory activity, such as beta-crosslaps and osteocalcin, could improve risk stratification for osteoporosis in individuals with SpA.

Ongoing innovations in ultrasound technology may enhance REMS's resolution and expand its applications to other skeletal sites; the developers of this technology are already releasing software for osteoarthritis prediction capabilities.

11. Conclusion

Radiofrequency Echographic Multispectrometry is a promising diagnostic tool for osteoporosis in spondylarthritis patients. Its ability to assess bone quality beyond density, radiation-free nature, portability, and peripheral applicability addresses many challenges inherent to traditional diagnostic methods. The main advantage of REMS compared to DXA from a physician's perspective is the ability to exclude extraosseous calcifications or formations in the analysis of BMD, being a more precise method of analysis for patients with long-standing SpA with spinal modification. Consistent data from this study and from other scientific works aiming at evaluating bone health in As clinical evidence supporting REMS continues to grow, it is poised to become an integral part of osteoporosis management in SpA, improving patient outcomes through timely and accurate diagnosis. The results point out the relative superiority of REMS vertebral scans compared to DXA vertebral scans in evaluating patients with SpA and vertebral modifications, as well as proving that there are no significant differences for hip scans for the two methods. As was expected, patients with SpA, especially with vertebral modifications have a lower BMD compared to patients with no structural vertebral modifications in the same age group, making their vertebra “older”. Further studies on larger studies are required to fully confirm these findings, especially comprising patients with other genetic characteristics and from different geographical regions and ethnicities.

Author Contributions

Methodology, Ionut-Andrei Badea, Ștefan Sorin Aramă and Mihai Bojincă; Software, Ionut-Andrei Badea; Formal analysis, Ionut-Andrei Badea; Investigation, Ionut-Andrei Badea, Violeta Bojincă and Casandra Negoiță; Resources, Mihai Bojincă, Violeta Bojincă, Gabriel Ghițescu and Mihaela Milicescu; Data curation, Ionut-Andrei Badea; Writing – original draft, Ionut-Andrei Badea; Writing – review & editing, Ștefan Sorin Aramă, Mihai Bojincă, Andreea-Ruxandra Ilina and Mădălina-Ștefania Vulcan; Supervision, Ștefan Sorin Aramă and Mihai Bojincă; Project administration, Ionut-Andrei Badea. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Grammarly AI was used to correct grammatical errors in the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Magrey, M., & Khan, M. A. (2010). Osteoporosis in ankylosing spondylitis. Current rheumatology reports, 12(5), 332–336. [CrossRef]

- Maksymowych WP, Salonen D, Hall S, et al. Assessment of bone mineral density in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: effects of syndesmophytes and spinal osteoproliferation. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(6):780-785.

- Boutroy S, Bouxsein ML, Munoz F, Delmas PD. Quantitative computed tomography and peripheral quantitative computed tomography for the assessment of bone strength and structure: a review. Bone. 2005;37(4):460-473. [CrossRef]

- Boonen S, Reginster JY, Eastell R, et al. The influence of spinal deformities on the assessment of bone mineral density by quantitative computed tomography in ankylosing spondylitis. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21(9):1494-1501. [CrossRef]

- Pitinca MD, Tomai Dea M, Gonnelli S, et al. REMS technology in daily practice: clinical cases. Osteoporos Int. 2022;33(3):441-449.

- Casciaro S, Pisani P, Conversano F, et al. An advanced quantitative echosound methodology for femoral neck densitometry. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2016;42(6):1337-1356. [CrossRef]

- Conversano F, Franchini R, Greco A, et al. A novel ultrasound methodology for estimating spine mineral density. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2015;41(1):281-300. [CrossRef]

- Di Iorio A, Caffarelli C, Tomai Pitinca MD, et al. Ultrasound fragility score: an innovative approach for the assessment of bone fragility. Measurement. 2017;103:151-157. [CrossRef]

- Cortet B, Dennison E, Diez-Perez A, et al. Radiofrequency Echographic Multi-Spectrometry (REMS) for the diagnosis of osteoporosis in a European multicenter clinical context. Bone. 2021;143:115786. [CrossRef]

- Amorim DMR, Sakane EN, Maeda SS, Lazaretti Castro M. New technology REMS for bone evaluation compared to DXA in adult women for the osteoporosis diagnosis: a real-life experience. Arch Osteoporos. 2021;16(1):175. [CrossRef]

- Cortet B, Dennison E, Diez-Perez A, et al. Radiofrequency echographic multi-spectrometry for the in vivo assessment of bone strength: outcomes of an expert consensus meeting organized by ESCEO. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2019;31(10):1375-1389.

- Caffarelli C, Tomai Pitinca MD, Al Refaie A, et al. Radiofrequency echographic multispectrometry compared with dual X-ray absorptiometry for osteoporosis diagnosis on lumbar spine and femoral neck. Osteoporos Int. 2019;30(2):391-402. [CrossRef]

- Adami G, Arioli G, Bianchi G, et al. Radiofrequency echographic multispectrometry for the prediction of incident fragility fractures: a 5-year follow-up study. Bone. 2020;134:115297. [CrossRef]

- Degennaro VA, Cagninelli G, Lombardi FA, et al. First assessment of maternal status during pregnancy by means of radiofrequency echographic multispectrometry technology. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2020;55(3):411-416. [CrossRef]

- Braga C, Andreola S, Gatti D, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of radiofrequency echographic multispectrometry in ankylosing spondylitis patients. Clin Rheumatol. 2021;40(9):3253-3261.

- Caffarelli C, Tomai Pitinca MD, Al Refaie A, et al. Ability of radiofrequency echographic multispectrometry to detect extraskeletal calcifications. J Clin Densitom. 2021;24(3):400-407.

- Fassio A, Pollastri F, Benini C, et al. Radiofrequency echographic multispectrometry and DXA for the evaluation of bone mineral density in axial spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2024;83(Suppl 1):470. [CrossRef]

- Braga C, Andreola S, Gatti D, et al. Feasibility and cost-effectiveness of portable REMS devices in rural settings for osteoporosis diagnosis. Osteoporos Int. 2023;34(1):55-63.

- Di Iorio A, Al Refaie A, Tomai Pitinca MD, et al. Radiofrequency echographic multispectrometry: a new tool for osteoporosis assessment in rheumatoid arthritis. Osteoporos Int. 2022;33(6):1237-1244. [CrossRef]

- Messina C, Giotto S, Colombo R, et al. REMS technology in fracture risk prediction: a meta-analysis. Bone. 2021;147:115926.

- Braga C, Andreola S, Gatti D, et al. Discrepancies between DXA and REMS in detecting osteoporosis in spondyloarthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2021;40(8):2981-2988.

- Rolla M, Halupczok-Żyła J, Jawiarczyk-Przybyłowska A, Bolanowski M. Effects of anti-TNF therapy on bone quality assessed by REMS in axial spondyloarthritis: a longitudinal study. J Rheumatol. 2021;48(2):210-217.

- Gonnelli S, Caffarelli C, Tomai Pitinca MD, et al. Rheumatologists' perspectives on the use of REMS for osteoporosis evaluation in spondyloarthritis: a national survey. Clin Rheumatol. 2022;41(3):841-847.

- Caffarelli C, Tomai Pitinca MD, Al Refaie A, et al. International survey on the use of REMS technology in osteoporosis diagnosis. Osteoporos Int. 2021;32(5):1023-1030.

- Adami G, Bianchi G, Brandi ML, et al. Monitoring bone quality improvements in spondyloarthritis patients on anti-resorptive therapy using REMS technology. Bone. 2021;149:115923.

- Bassi A, Giannini S, Gonnelli S, et al. Cost-effectiveness of REMS technology in the management of osteoporosis in spondyloarthritis. Osteoporos Int. 2023;34(4):777-785.

- Gonnelli S, Caffarelli C, Tomai Pitinca MD, et al. Future perspectives of REMS technology in osteoporosis: integration with biomarkers of bone turnover. Clin Cases Miner Bone Metab. 2023;20(1):45-52.

- Conversano F, Franchini R, Greco A, et al. A novel ultrasound methodology for estimating spine mineral density. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2015;41(1):281-300. [CrossRef]

- Di Paola M, Gatti D, Viapiana O, et al. Radiofrequency echographic multispectrometry compared with dual X-ray absorptiometry for osteoporosis diagnosis on lumbar spine and femoral neck. Osteoporos Int. 2019;30(2):391-402. [CrossRef]

- Cortet B, Dennison E, Diez-Perez A, et al. Radiofrequency echographic multi spectrometry (REMS) for the diagnosis of osteoporosis in a European multicenter clinical context. Bone. 2021;143:115786. [CrossRef]

- Adami G, Arioli G, Bianchi G, et al. Radiofrequency echographic multispectrometry for the prediction of incident fragility fractures: a 5-year follow-up study. Bone. 2020;134:115297. [CrossRef]

- Pisani P, Conversano F, Muratore M, et al. Fragility Score: a REMS-based indicator for the prediction of incident fragility fractures at 5 years. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2023;35(4):763-73.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).