1. Introduction

Bone scintigraphy is one of the most frequently performed tests in the field of nuclear medicine [

1]. This diagnostic method visualizes the uptake of radiopharmaceuticals into bone [

2], aiding in the detection of bone metastases from malignant tumors and the assessment of bone metastasis treatment efficacy [

3,

4]. Among malignant tumors, prostate cancer frequently presents with osteoblastic bone metastases [

5,

6], highlighting the critical role of early bone metastasis diagnosis in optimizing treatment decisions [

7]. The 2016 Prostate Cancer Practice Guidelines underscore the continued use of bone scintigraphy with

99mTc as the standard technique for diagnosing bone metastases [

8]. Additionally, bone scintigraphy is used to estimate prognosis following bone metastasis treatment [

9,

10]. Typically, the diagnosis through bone scintigraphy relies on visual assessments by a doctor, and the accuracy of these readings can vary based on the examiner's skill and experience, leading to inter-observer variability [

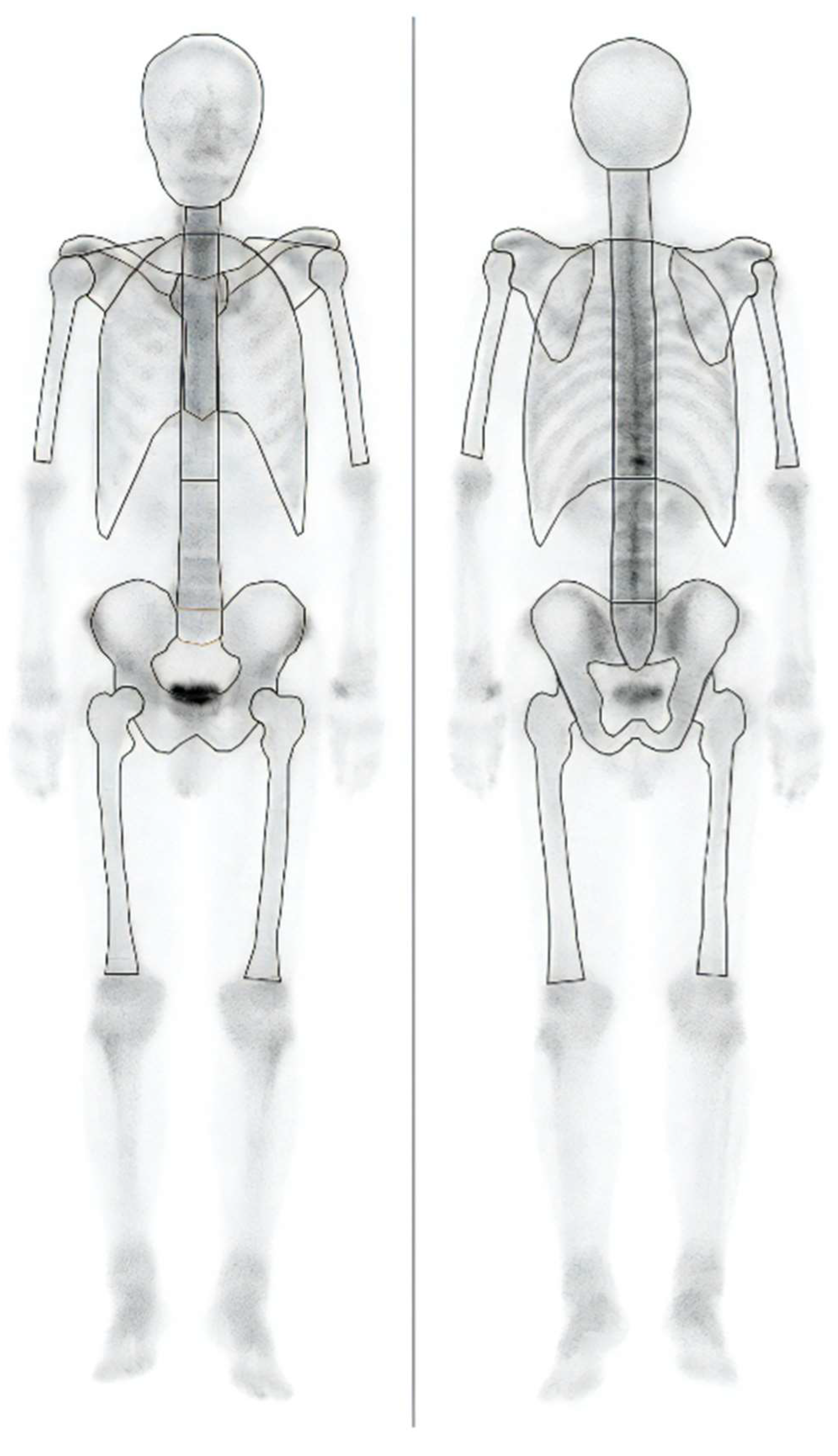

11]. BONENAVI (PDR Pharma Co., Ltd.) is an imaging-analysis program for bone scintigraphy designed to assist in image interpretation by automatically identifying high-accumulation areas. This program calculates the skeletal count (Skel-C) by analyzing anterior and posterior bone-scintigraphy images. Importantly, Skel-C focuses solely on the bones, excluding other structures such as the kidneys, bladder, soft tissues, and the peripheral bones of the extremities. The region considered for Skel-C calculation is outlined by solid lines, as depicted in

Figure 1.

BONENAVI can obtain two types of counts: Skel-C, which represents the skeletal count, and Total-C, which includes all counts within the imaging field of view. BONENAVI is based on artificial neural networks (ANN) and can assess the likelihood of bone metastases [

12], thereby reducing interobserver variability [

13]. The ANN-generated value can aid in diagnosis, and its analytical results may influence staging evaluations and subsequent treatment plans. Therefore, BONENAVI serves as a significant diagnostic tool, with numerous studies focusing on enhancing its functionality [

14,

15,

16]. The European Association of Nuclear Medicine guidelines recommend a Total-C of 1.5 million counts (mc) or more for bone scintigraphy [

17]. According to Anand et al., the bone scan index (BSI) decreases when Total-C falls below 1 mc; they concluded that, for whole-body bone scintigraphy, the scan speed should be chosen such that Total-C is above 1.5 mc [

18]. However, the previous study was based on simulations, and actual Total-C measurements may vary owing to factors such as urine retention and soft-tissue accumulation. We believe that the image count of interest in the image-analysis program is Skel-C, and that Total-C may not contribute directly. Therefore, we hypothesize that the accuracy of the image-analysis program is primarily influenced by Skel-C, rather than by Total-C, which can vary owing to various factors. However, Skel-C is not currently recommended by existing guidelines; to our knowledge, no prior studies have evaluated its use. Thus, this study aimed to develop a new image quality index (Skel-C) to improve the accuracy of bone-scintigraphy imaging-analysis programs.

3. Results

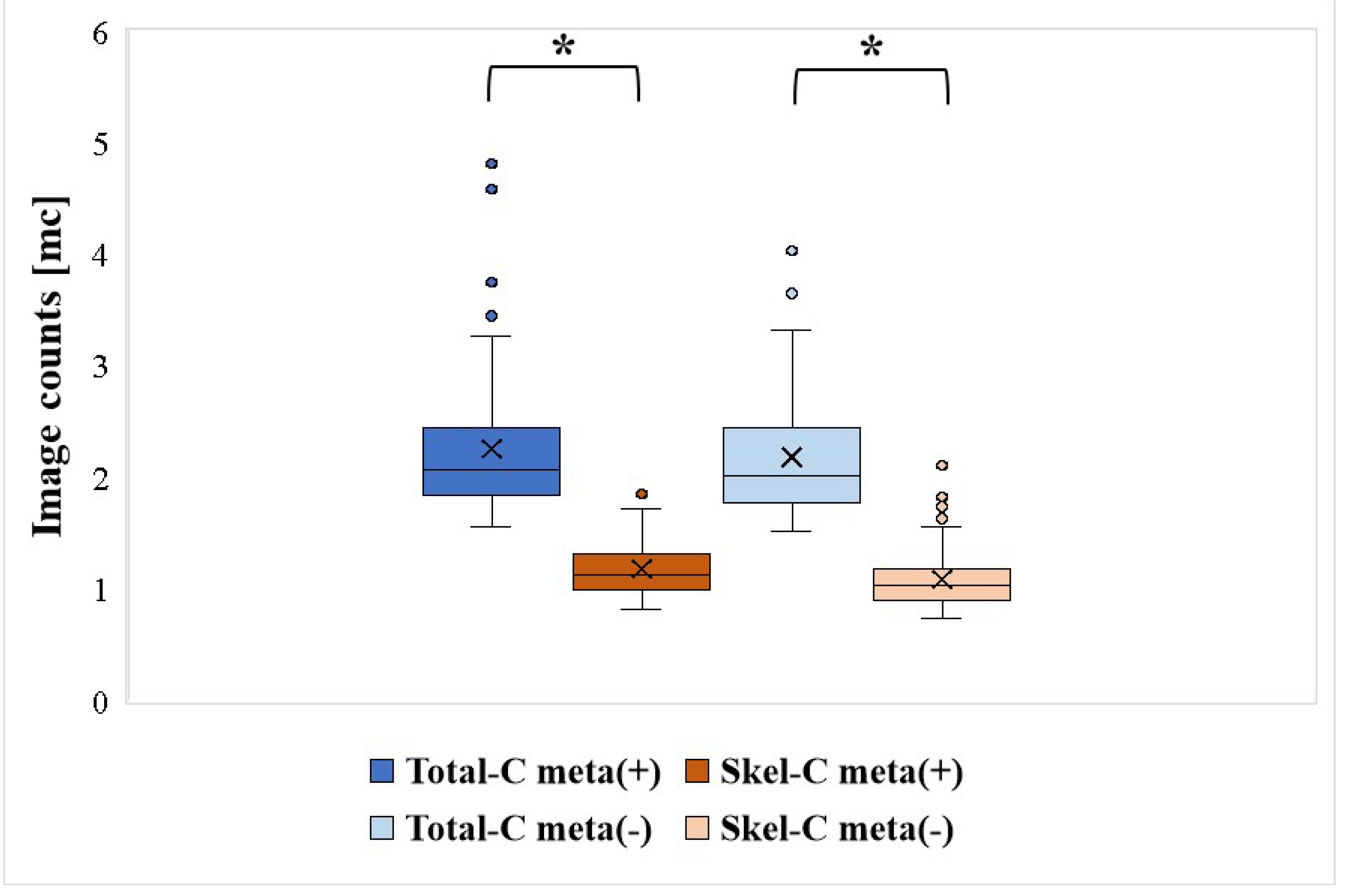

All patients were grouped on the basis of the presence or absence of bone metastases. The mean, median, minimum (Min), maximum (Max), and SD of Total-C and Skel-C are summarized in

Table 2, with the results of significance tests shown in

Figure 2. Skel-C was significantly lower than Total-C in cases with and without bone metastases. Additionally, Skel-C exhibited a lower SD and less variability in counts than Total-C.

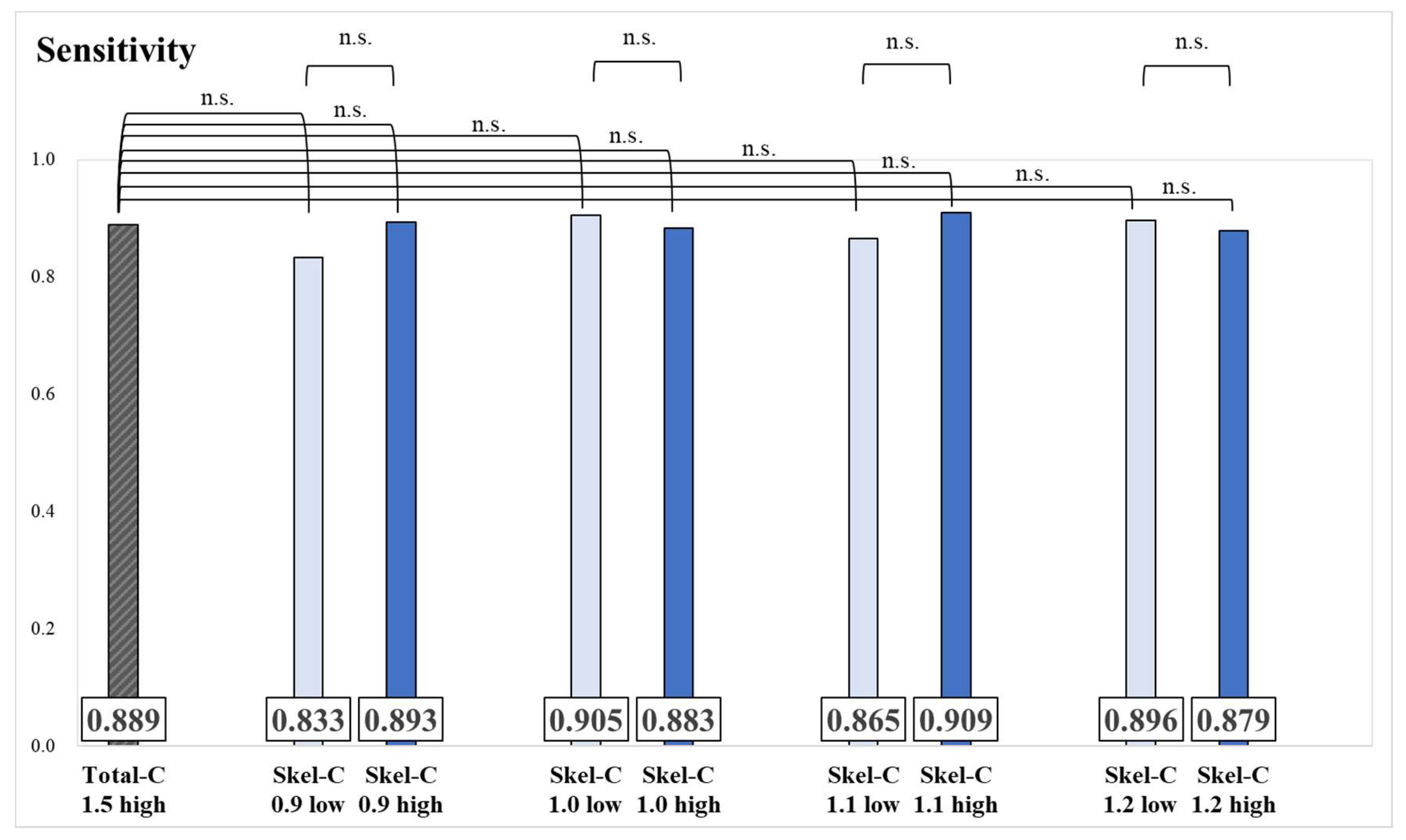

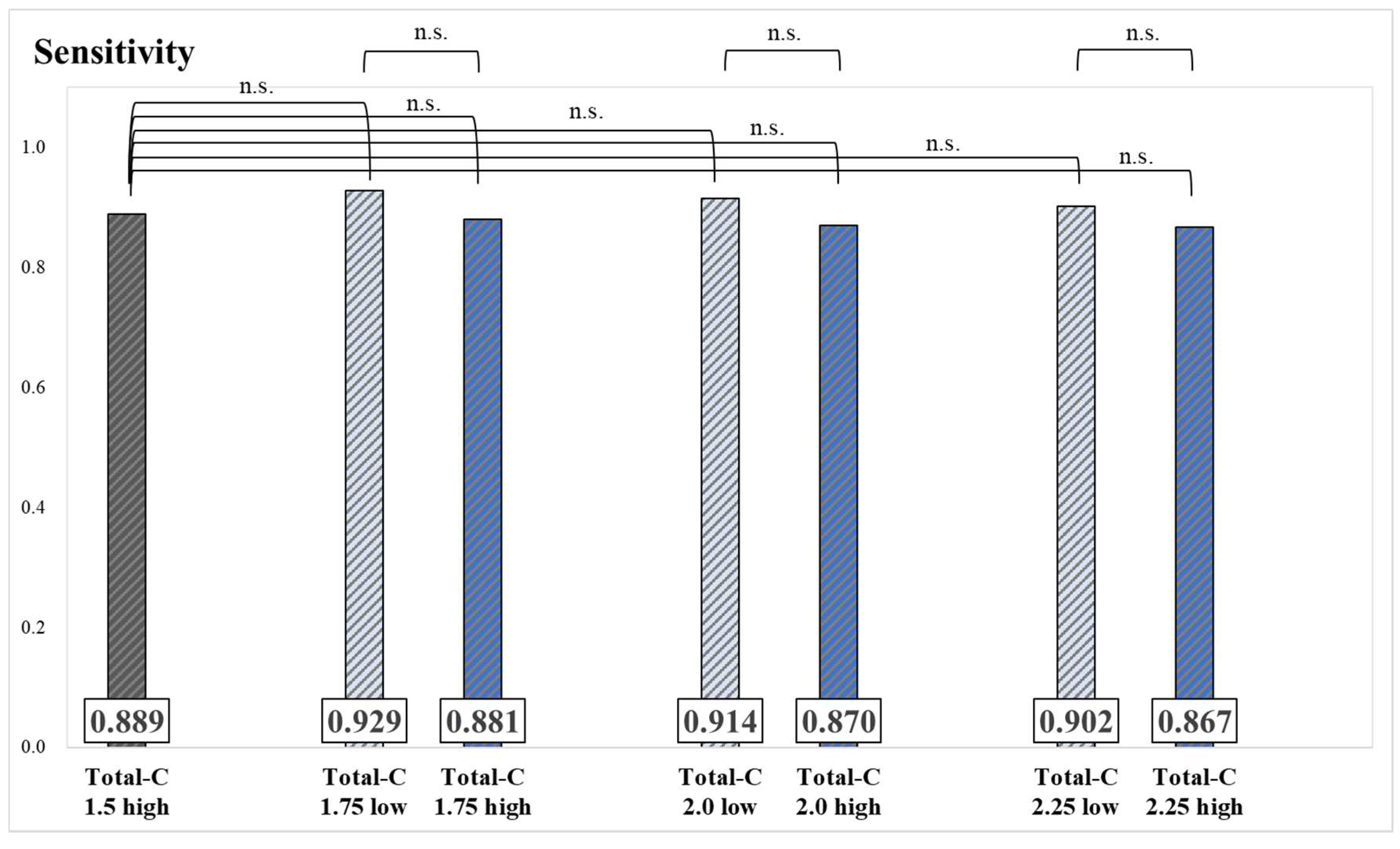

Results of the sensitivity and significance tests for each group are presented in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4. No significant differences were observed in sensitivity values between groups.

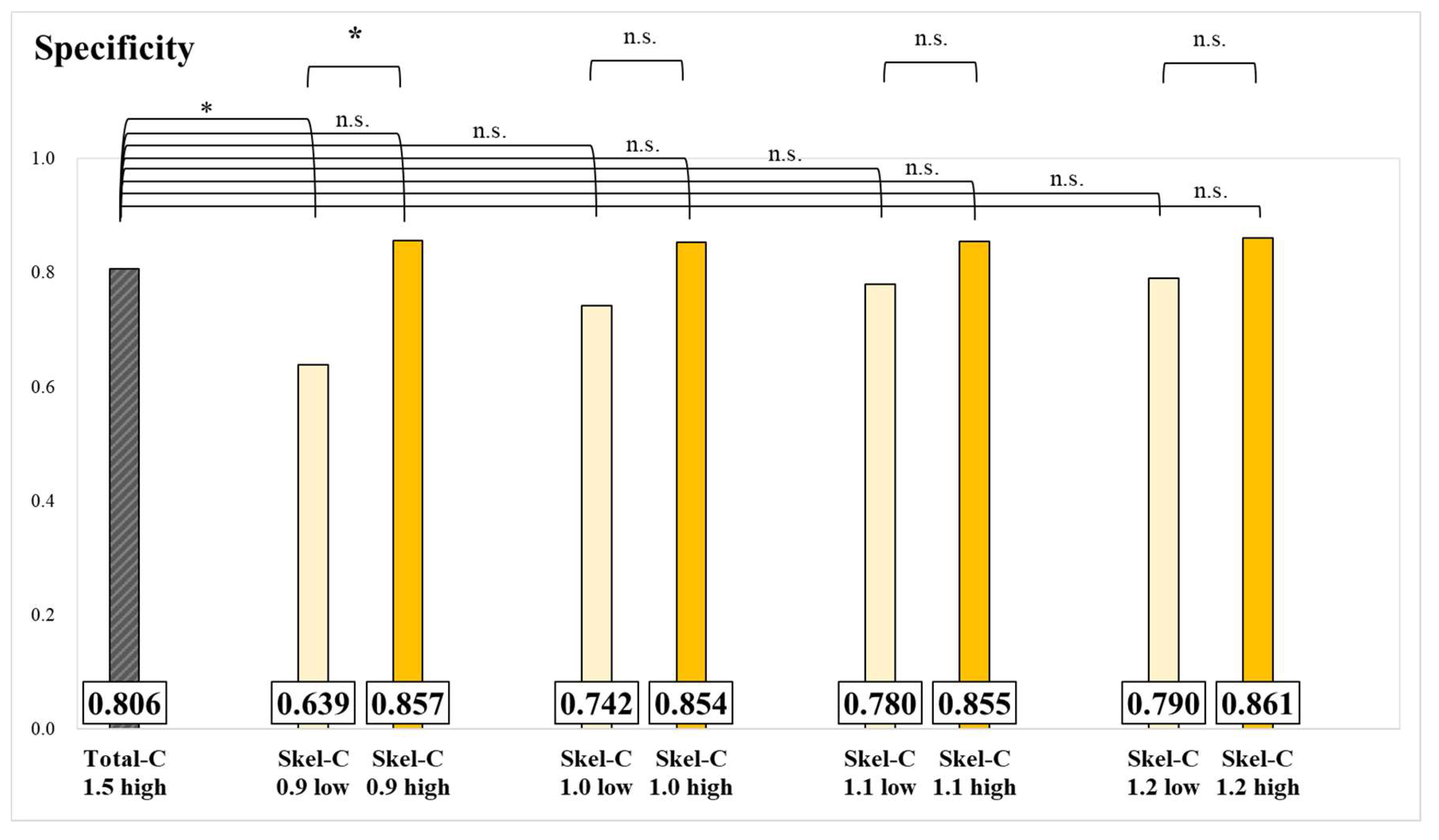

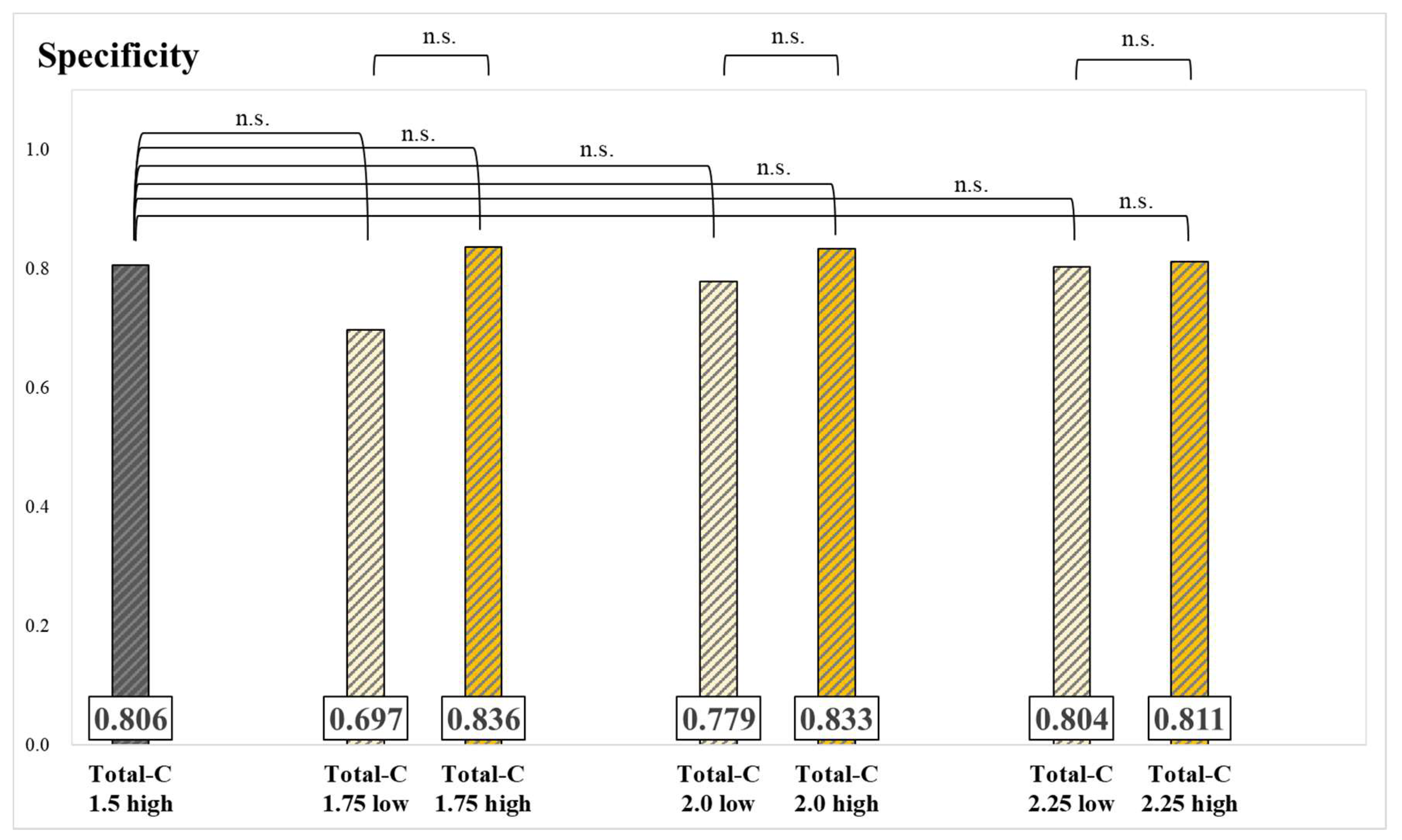

The results of specificity for each group and significance tests are presented in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6. The specificity of the Skel-C 0.9 low group was significantly lower than that of the Skel-C 0.9 high group and the Total-C 1.5 high group. Although not statistically significant, the specificity of the Skel-C 0.9 high, Skel-C 1.0 high, Skel-C 1.1 high, Skel-C 1.2 high, Total-C 1.75 high, Total-C 2.0 high, and Total-C 2.25 high groups exceeded that of the Total-C 1.5 high group.

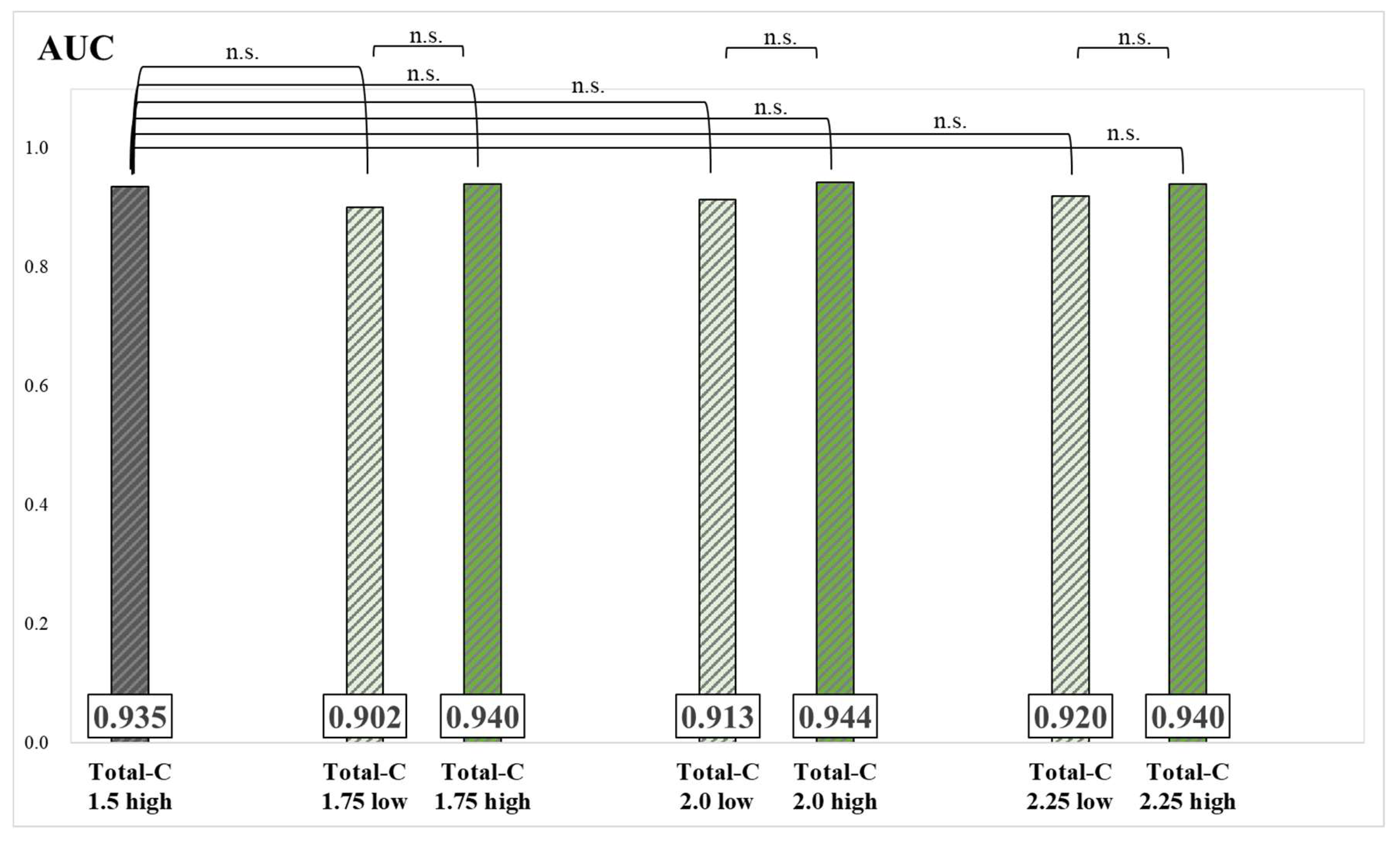

The results of the AUC and significance tests for each group are presented in

Figure 7 and

Figure 8. Although no significant differences were found between groups, AUC values of the Skel-C 0.9 high, Skel-C 1.0 high, Skel-C 1.1 high, Skel-C 1.2 high, Total-C 1.75 high, Total-C 2.0 high, and Total-C 2.25 high groups were higher than that of the Total-C 1.5 high group.

4. Discussion

In this study, we focused on developing a new image quality index using the Skel-C index to improve the accuracy of bone-scintigraphy imaging analysis. Total-C and Skel-C were compared to evaluate differences in count variability on whole-body images and the impact of high and low Skel-C and Total-C values on diagnostic performance. As shown in

Table 2, the mean, median, and minimum values were higher in the group with bone metastases than in the group without bone metastases. We believe this is because bone metastases typically exhibit stronger radiopharmaceutical accumulation than normal bone. In the Skel-C group, the maximum value was higher in the group without bone metastases. Further, upon examining the case with the maximum value, we found that the patient had a markedly reduced estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR = 5). We hypothesize that reduced renal function caused less efflux of radiopharmaceuticals from the body, leading to increased counts. This finding suggests that even in patients without bone metastases, individual physiological differences can cause variations in radiopharmaceutical accumulation in normal bone. The SD of Skel-C was smaller than that of Total-C, regardless of the presence or absence of bone metastases. We attribute this difference to the effects of urinary retention and soft tissue accumulation. Prostate cancer patients often experience dysuria and may have difficulty completely emptying their bladders, even when encouraged to urinate before the examination. Skel-C, which excludes counts from the bladder, soft tissues, and peripheral limb bones, is less affected by these factors. Consequently, we believe that Skel-C reduces variability in whole-body image counts between patients, enhancing the reliability of image quality assessments.

Herein, Skel-C thresholds of 0.9 mc, 1.0 mc, 1.1 mc, and 1.2 mc and Total-C thresholds of 1.75 mc, 2.0 mc, and 2.25 mc were used to classify patients into high and low groups for each threshold, with the aim of identifying the optimal Skel-C threshold. The sensitivity results showed no significant differences between groups divided by Skel-C and Total-C thresholds (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). This finding reflects the inherently high sensitivity of bone scintigraphy for detecting bone metastases. False-negative cases primarily included osteolytic bone metastases, small accumulations that were undetectable, and slight residual bone metastases during treatment. Bone scintigraphy is highly sensitive for detecting osteoblastic bone metastases but has lower sensitivity for osteolytic bone metastases [

20]. While osteoblastic bone metastases are more common in prostate cancer, osteolytic bone metastases can also occur. In this study, three patients with osteolytic bone metastases were classified as false negatives. The low accumulation of

99mTc-MDP in osteolytic metastases likely contributed to their limited detectability. Additional false-negative cases included three patients with small metastases in the ribs and pelvis and three patients with residual bone metastases alleviated by treatment. Koizumi et al. noted that in patients with small bone metastases or those undergoing treatment, the metastases tend to be smaller, resulting in a lower ANN value and subsequent false-negative results when using analysis software [

21]. Since there were no significant differences in sensitivity values among all groups, we conclude that the influence of high and low Total-C and Skel-C values on sensitivity is minimal. Instead, the primary factors influencing sensitivity appear to be the characteristics of individual cases, including the presence of osteolytic metastases, the size of the metastases, and other patient-specific factors. The specificity of the Skel-C 0.9 low group was significantly lower than that of the Skel-C 0.9 high group and the Total-C 1.5 high group. In contrast, no significant differences were observed among groups classified based on Total-C thresholds (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). The Total-C 1.5 high group was imaged based on the currently established index, whereas the Skel-C 0.9 low group demonstrated significantly lower specificity. The Skel-C 0.9 low group was also imaged with Total-C values exceeding 1.5 mc; however, its specificity was lower, suggesting that the accuracy of the image-analysis program is more influenced by Skel-C than by Total-C. Because a Total-C-based threshold did not significantly reduce specificity, whereas a Skel-C-based threshold reflected a decrease in specificity, we consider Skel-C to be a valuable image quality index. Although not statistically significant, the Skel-C 0.9 high, Skel-C 1.0 high, Skel-C 1.1 high, Skel-C 1.2 high, Total-C 1.75 high, Total-C 2.0 high, and Total-C 2.25 high groups demonstrated higher specificity and AUC than the Total-C 1.5 high group (

Figures 5, 6, 7, and 8). Furthermore, compared to the Total-C 1.5 high group, the Skel-C 0.9 low, Skel-C 1.0 low, Skel-C 1.1 low, and Skel-C 1.2 low groups exhibited lower specificity and AUC. This suggests that including cases with Skel-C < 0.9 mc leads to a decrease in specificity and AUC in the image-analysis program, potentially reducing its diagnostic performance. Since Total-C is influenced by variables such as urine storage and soft tissue accumulation, it may not accurately represent bone uptake. Although Total-C exceeded the recommended threshold of 1.5 mc in all cases, these extraneous factors may reduce its ability to precisely reflect the actual bone count. BONENAVI analyzes bone-scintigraphy images by evaluating the count, location, size, and shape of accumulation sites to generate an ANN value ranging from 0 to 1, which indicates the risk of bone metastasis. A value of 0 represents a negative result, 1 represents a positive result, and 0.5 serves as the threshold for determining the presence of bone metastases [

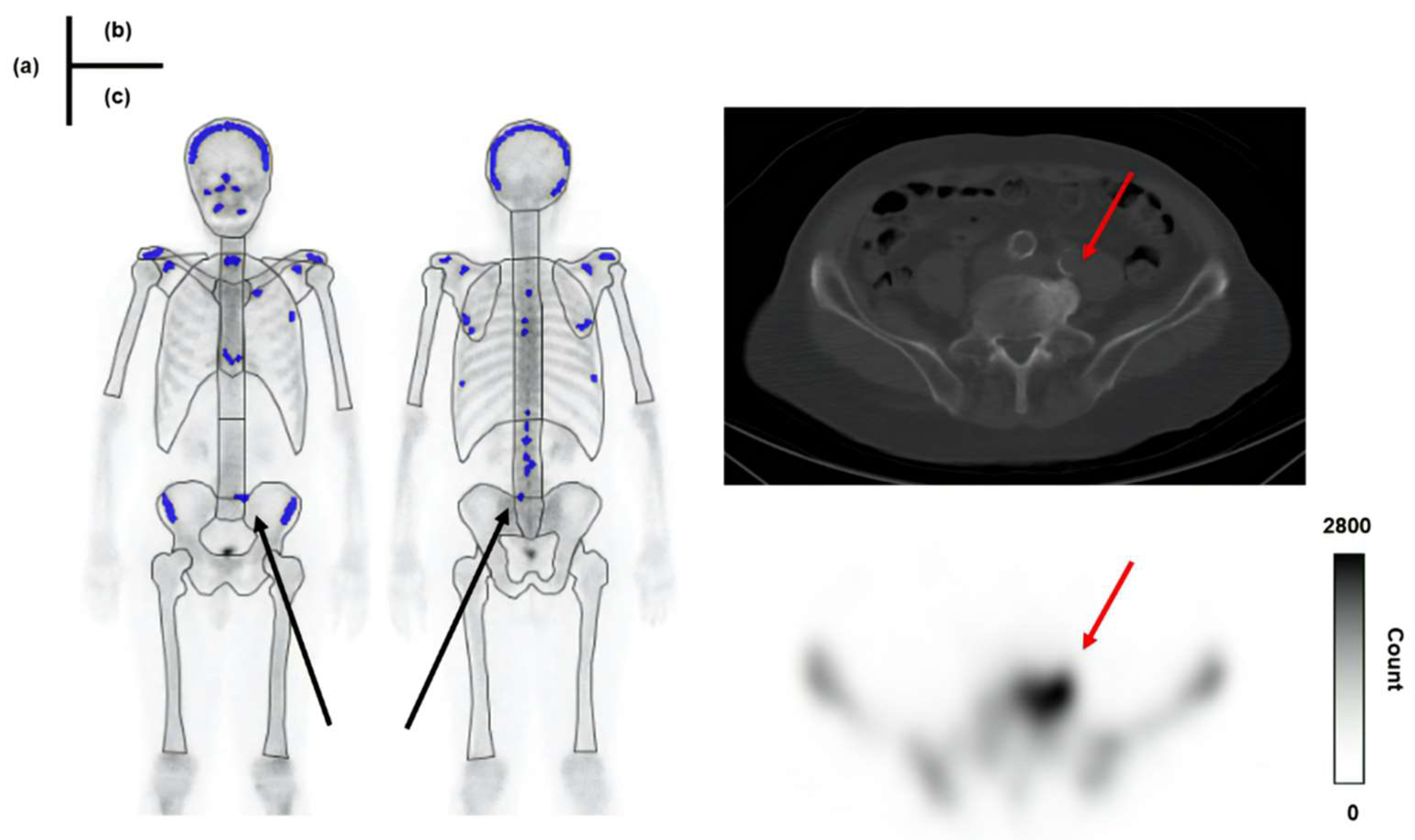

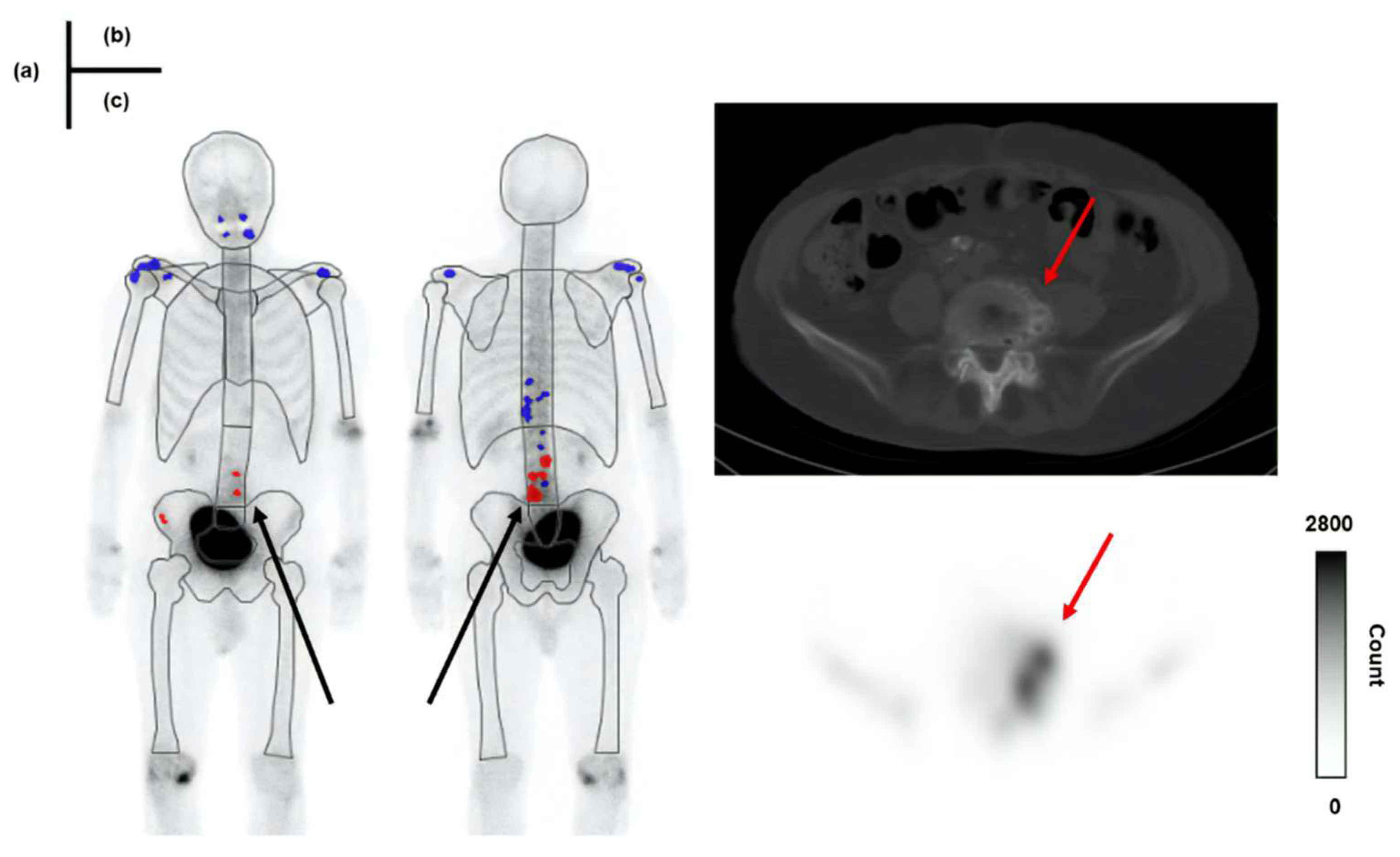

22]. In this study, 31 false-positive cases were reported, and approximately 42% (13 cases) had a Skel-C of less than 0.9 mc. Examples of cases with accumulation in osteophytes classified as true negatives and false positives are illustrated in

Figure 9 and

Figure 10, respectively.

In

Figure 10, Skel-C is low, and the result is a false positive despite the high Total-C. As a feature of the image-analysis program, the whole-body image is subdivided into regions such as the skull, vertebrae, and pelvis. A count threshold is then established based on the counts within these regions, which are recognized as hotspots [

22]. Therefore, in cases with low Skel-C, the threshold for recognizing hyperaccumulation sites within each region tends to be lower, likely increasing the likelihood of false positives. In this study, the specificity of Skel-C < 0.9 mc was approximately 64%, which we consider insufficient for the precision required by the imaging-analysis program. In bone scintigraphy, accumulating 99mTc-MDP exclusively in bone metastases is challenging, as it also accumulates in fractures, osteophytes, and osteoarthritis. Improving the ability to differentiate between bone metastases and nonspecific uptake is crucial to enhancing diagnostic accuracy. Low specificity in bone scintigraphy may lead to incorrect identification of bone metastases, potentially resulting in misdiagnosis of prostate cancer staging and affecting subsequent treatment planning [

5]. Therefore, a test with both high sensitivity and specificity is essential. Based on the results of this study, we believe that Total-C alone may not accurately reflect the bone area count. Using both Total-C and Skel-C as complementary image quality indexes can improve diagnostic reliability. The specificity of the Skel-C 0.9 low group was significantly lower than that of the Skel-C 0.9 high group and the Total-C 1.5 high group, suggesting that imaging should be conducted with Skel-C values of 0.9 mc or higher. This study highlights the advantages of incorporating Skel-C as an image quality index in bone-scintigraphy imaging-analysis programs.

Factors that may influence Skel-C include the administered dose, post-injection waiting time, and scan speed. Increasing the administered dose is not considered an appropriate approach owing to concerns about increased radiation exposure. Based on the results of this study, we propose an approach to adjust the scan speed and post-injection waiting time to ensure adequate image counts. According to Anand et al. [

18], doubling the scan speed reduces the acquired image counts by approximately 50%. Based on this observation, we formulated Equation 1 to determine the optimal scan speed.

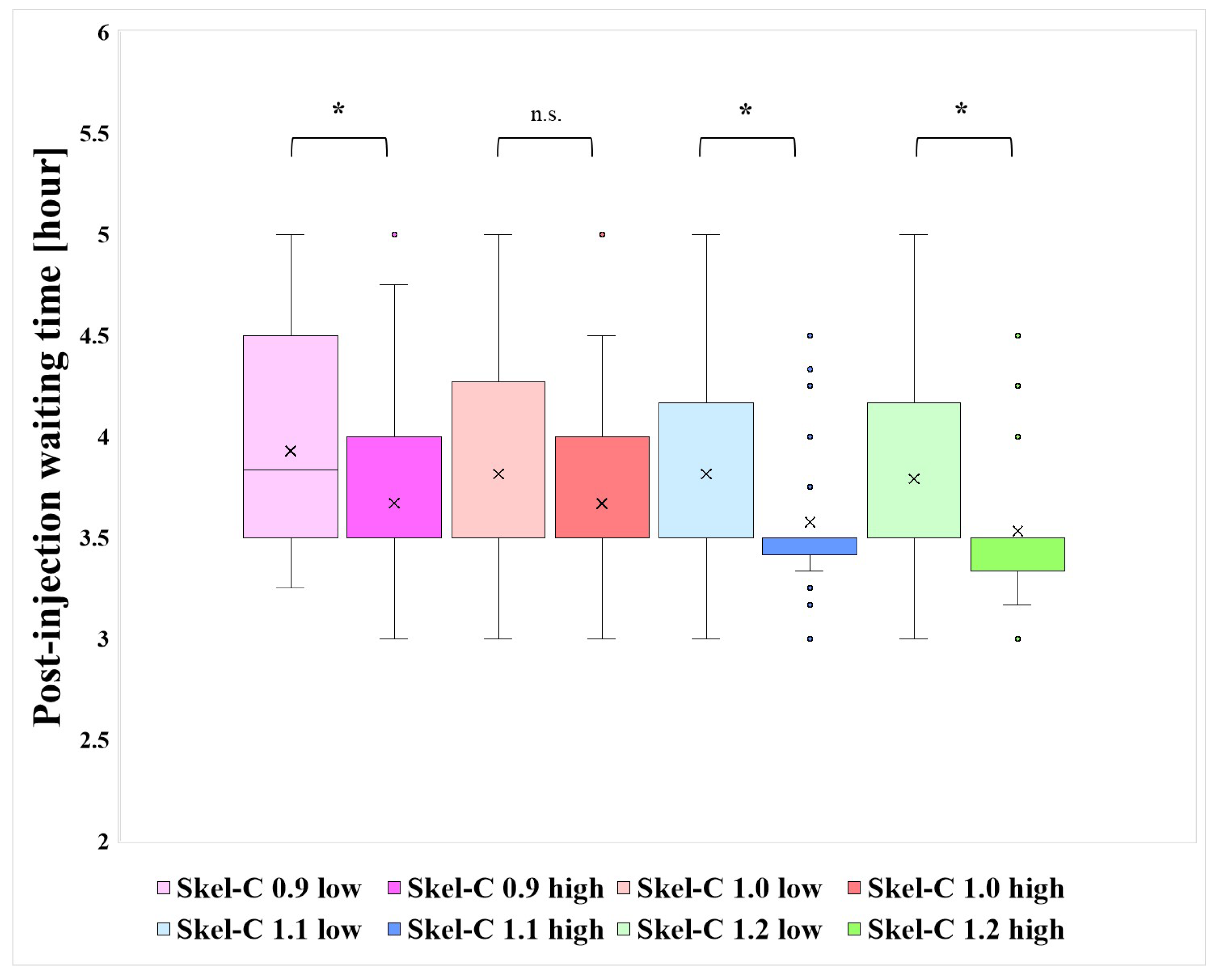

In this study, the scan speed was set at 12 cm/min, and the lowest observed Skel-C value was 0.73 mc. To meet the criterion of Skel-C > 0.9 mc, the image count would need to increase by approximately 1.233 times. Using Equation 1, the optimal scan speed was calculated to be approximately 9.73 cm/min. However, extending the scan time increases the risk of motion artifacts, potentially degrading image quality. Therefore, careful attention should be paid to each patient's physical condition; if feasible, adjusting the scan speed may allow for higher accuracy in image analysis compared to conventional methods. Additionally,

Figure 11 presents the distribution of post-injection waiting times for each group classified based on the Skel-C threshold, along with results of Wilcoxon's rank-sum test (significance level: 5%) for statistical analysis.

Figure 11 presents significant differences in post-injection waiting times among groups with Skel-C thresholds other than 1.0mc. As indicated in

Table 1, the Skel-C 0.9 low group had a relatively long mean waiting time of approximately 4 h. These findings suggest that setting the post-injection waiting time to around 3–3.5 h helps maintain higher Skel-C.

This study has several limitations. Because this was a retrospective study, we were unable to investigate the impact of variations in the scan speed, dosage, and post-injection waiting time on image counts. Additionally, effects of cancer type, age, and sex on Total-C and Skel-C could not be assessed. These variables may influence the counts and should be considered in future prospective studies to further validate the findings.

Figure 1.

Skeletal count (Skel-C) calculation area.

Figure 1.

Skeletal count (Skel-C) calculation area.

Figure 2.

Distribution of Total-C and Skel-C and the results of significance tests.

Figure 2.

Distribution of Total-C and Skel-C and the results of significance tests.

Figure 3.

Sensitivity and significance tests for each group, classified based on the threshold of Skel-C (*: p < 0.05, n.s.: not significant).

Figure 3.

Sensitivity and significance tests for each group, classified based on the threshold of Skel-C (*: p < 0.05, n.s.: not significant).

Figure 4.

Sensitivity and significance tests for each group, classified based on the threshold of Total-C (*: p < 0.05, n.s.: not significant).

Figure 4.

Sensitivity and significance tests for each group, classified based on the threshold of Total-C (*: p < 0.05, n.s.: not significant).

Figure 5.

Specificity and significance tests for each group, classified based on the threshold of Skel-C (*: p < 0.05, n.s.: not significant).

Figure 5.

Specificity and significance tests for each group, classified based on the threshold of Skel-C (*: p < 0.05, n.s.: not significant).

Figure 6.

Specificity and significance tests for each group, classified based on the threshold of Total-C (*: p < 0.05, n.s.: not significant).

Figure 6.

Specificity and significance tests for each group, classified based on the threshold of Total-C (*: p < 0.05, n.s.: not significant).

Figure 7.

AUC values and significance tests for each group, classified based on the threshold of Skel-C (*: p < 0.05, n.s.: not significant).

Figure 7.

AUC values and significance tests for each group, classified based on the threshold of Skel-C (*: p < 0.05, n.s.: not significant).

Figure 8.

AUC values and significance tests for each group, classified based on the threshold of Total-C (*: p < 0.05, n.s.: not significant).

Figure 8.

AUC values and significance tests for each group, classified based on the threshold of Total-C (*: p < 0.05, n.s.: not significant).

Figure 9.

A case showing a true negative result in BONENAVI. Total-C: 2.37 million count (mc), Skel-C:1.34 mc. (a): results of BONENAVI analysis (b): computed tomography (CT) image (c): single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) image.

Figure 9.

A case showing a true negative result in BONENAVI. Total-C: 2.37 million count (mc), Skel-C:1.34 mc. (a): results of BONENAVI analysis (b): computed tomography (CT) image (c): single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) image.

Figure 10.

A patient showing a false-positive result in BONENAVI. Total-C: 3.17 mc, Skel-C:0.89 mc. (a): results of BONENAVI analysis (b): CT image (c): SPECT image.

Figure 10.

A patient showing a false-positive result in BONENAVI. Total-C: 3.17 mc, Skel-C:0.89 mc. (a): results of BONENAVI analysis (b): CT image (c): SPECT image.

Figure 11.

Distribution of post-injection waiting times and results of significance tests for each group stratified by Skel-C threshold.

Figure 11.

Distribution of post-injection waiting times and results of significance tests for each group stratified by Skel-C threshold.

Table 1.

Details of each grouping with the total count (Total-C) and skeletal count (Skel-C) as thresholds.

Table 1.

Details of each grouping with the total count (Total-C) and skeletal count (Skel-C) as thresholds.

| |

N |

Bone meta (+) |

Bone meta

(-) |

Injected dose

[MBq] |

Post-injection waiting time

[hour] |

| Skel-C 0.9 low |

42 |

6 |

36 |

755 |

3.93 |

| Skel-C 1.0 low |

87 |

21 |

66 |

757 |

3.83 |

| Skel-C 1.1 low |

137 |

37 |

100 |

752 |

3.84 |

| Skel-C 1.2 low |

167 |

48 |

119 |

753 |

3.82 |

| Skel-C 0.9 high |

194 |

75 |

119 |

751 |

3.73 |

| Skel-C 1.0 high |

149 |

60 |

89 |

749 |

3.72 |

| Skel-C 1.1 high |

99 |

44 |

55 |

751 |

3.66 |

| Skel-C 1.2 high |

69 |

33 |

36 |

747 |

3.63 |

| Total-C 1.75 low |

47 |

14 |

33 |

757 |

3.88 |

| Total-C 2.0 low |

112 |

35 |

77 |

758 |

3.72 |

| Total-C 2.25 low |

153 |

51 |

102 |

758 |

3.83 |

| Total-C 1.75 high |

189 |

67 |

122 |

758 |

3.68 |

| Total-C 2.0 high |

124 |

46 |

78 |

758 |

3.81 |

| Total-C 2.25 high |

83 |

30 |

53 |

758 |

3.63 |

| Total-C 1.5 high |

236 |

81 |

155 |

752 |

3.76 |

Table 2.

Mean [million count (mc)], median [mc], minimum (Min) [mc], maximum (Max) [mc], and standard deviation (SD) of Total-C and Skel-C grouped by bone metastasis (Bone meta).

Table 2.

Mean [million count (mc)], median [mc], minimum (Min) [mc], maximum (Max) [mc], and standard deviation (SD) of Total-C and Skel-C grouped by bone metastasis (Bone meta).

| |

Bone meta (+) |

Bone meta (-) |

| |

Total-C |

Skel-C |

Total-C |

Skel-C |

| Mean [mc] |

2.25 |

1.18 |

2.18 |

1.09 |

| Median [mc] |

2.07 |

1.13 |

2.02 |

1.03 |

| Min [mc] |

1.56 |

0.81 |

1.51 |

0.73 |

| Max [mc] |

4.82 |

1.85 |

4.11 |

2.14 |

| SD |

0.63 |

0.23 |

0.54 |

0.26 |