1. Introduction

Spondylarthritis encompasses a group of inflammatory diseases—including ankylosing spondylitis (AS) and psoriatic arthritis (PsA)—that primarily affect the axial skeleton and often extend to peripheral joints. Axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) is characterized by both acute inflammatory episodes and chronic structural changes in the spine and sacroiliac joints. Chronic inflammation leads to increased production of proinflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-17), which disrupt normal bone remodeling by stimulating osteoclast-mediated bone resorption while inhibiting osteoblast function. Magrey and Khan (2010) reported that the prevalence of osteoporosis in SpA patients can range from 18.7% to 62%, underscoring the variability in disease presentation and the challenges in early detection [

1].

Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) remains the clinical standard for assessing bone mineral density (BMD) at the lumbar spine and hip; however, its utility in axSpA is limited by structural artifacts. The presence of syndesmophytes, vertebral fusion, and calcifications may lead to overestimated BMD values that mask true bone loss [

2]. Although technological advances (e.g., AI-assisted image processing) have improved DEXA’s usability, these inherent limitations persist. Quantitative computed tomography (qCT) offers volumetric BMD and detailed architectural insight but is constrained by higher radiation exposure and limited accessibility [

3].

In response, Radiofrequency Echographic Multispectrometry (REMS) has emerged as a promising, radiation-free alternative that not only estimates BMD but also provides a comprehensive evaluation of bone quality—assessing parameters such as elasticity, stiffness, and microarchitectural integrity. Updated REMS protocols now allow assessment at peripheral sites (e.g., the radius or tibia), thereby minimizing interference from axial artifacts [

4]. Furthermore, REMS computes a Fragility Score (FS) that predicts fracture risk independently of BMD; for example, Pisani et al. (2023) reported FS area-under-the-curve (AUC) values of 0.811 for women and 0.780 for men [

5]. REMS has been validated in diverse populations—a Polish study demonstrated high diagnostic agreement with DXA [

6], while validation studies have been performed in Brazil [

7] and Japan [

8]. In addition, a systematic review [

9] and a meta-analysis [

10] confirm that REMS not only correlates well with DXA but also provides additional insights into bone quality critical for accurate fracture risk prediction. Badea et al. (2022) further described REMS as a novel approach for bone health assessment [

11]. Collectively, these advancements position REMS as a transformative tool for early osteoporosis diagnosis and management in axSpA [

11,

12].

1.1. Pathophysiology of Osteoporosis in Spondyloarthritis

Osteoporosis in axSpA is primarily driven by chronic systemic inflammation that disrupts normal bone homeostasis. Proinflammatory cytokines—particularly TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-17—increase the expression of receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-Β ligand (RANKL) while suppressing osteoprotegerin (OPG), thereby promoting osteoclastogenesis and accelerating bone resorption [

13].

In addition, TNF-α and IL-17 interfere with osteoblast function by inhibiting the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway—essential for bone formation—and by stimulating the production of inhibitory proteins such as Dickkopf-1 (DKK-1) and sclerostin [

14]. These molecular events enhance bone resorption while impairing bone formation, ultimately resulting in a decline in bone strength.

Paradoxically, the chronic inflammation characteristic of axSpA can also induce aberrant new bone formation at the vertebral entheses, leading to syndesmophyte formation and ossification of spinal ligaments [

15]. Although these structural changes contribute to spinal rigidity and ankylosis, they may mask early bone loss, complicating accurate osteoporosis assessment. Moreover, factors such as reduced physical activity due to pain and stiffness [

16], long-term glucocorticoid therapy [

17], and nutritional deficiencies (e.g., vitamin D deficiency) [

18] further exacerbate osteoporosis in these patients.

Recent investigations have also examined immune-modulatory therapies. For example, anti-TNF agents have been shown to reduce inflammation and favorably affect bone remodeling markers [

19]. However, while such therapies may improve BMD, their effects on bone quality and microarchitecture require further elucidation [

19].

1.2. Principles of Radiofrequency Echographic Multispectrometry (REMS)

REMS is an ultrasound-based diagnostic tool that evaluates bone health by analyzing unfiltered radiofrequency (RF) signals obtained during a standard ultrasound scan. Unlike DXA—which measures areal BMD—REMS employs advanced spectral analysis to assess both quantitative (BMD) and qualitative (elastic properties and microarchitecture) aspects of bone.

1.3. Signal Acquisition

During a REMS examination, a high-frequency convex ultrasound probe (typically 3.5 MHz) is placed over the target region (usually the lumbar spine or proximal femur). The probe emits ultrasound waves that traverse the bone, and instead of processing these signals solely for image creation (as in conventional B-mode imaging), REMS records the complete RF data. Di Paola et al. (2019) reported correlation coefficients of 0.93–0.94 between REMS-derived BMD and DXA measurements, underscoring the importance of precise signal acquisition [

3].

1.4. Spectral Analysis and Reference Model Comparison

The recorded RF data are transformed into the frequency domain using techniques such as the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT). The resulting spectral profile represents the bone’s acoustic signature and reflects its physical properties. REMS software then compares the patient-specific spectral profile with a proprietary database of reference models developed from large, population-based studies (stratified by age, sex, and BMI), yielding an estimated BMD that closely aligns with DXA measurements [

3].

1.5. Derivation of Additional Diagnostic Parameters

In addition to BMD, REMS calculates the elastic modulus (E), which quantifies bone stiffness and correlates with mechanical strength and fracture resistance. REMS also evaluates microarchitectural integrity by analyzing subtle variations in the spectral data corresponding to the organization of trabecular and cortical bone. A key output is the Fragility Score (FS), a dimensionless index (ranging from 0 to 100) that quantifies bone fragility independently of BMD. Pisani et al. (2023) reported FS AUC values of 0.811 for women and 0.780 for men, demonstrating robust predictive capacity [

5].

1.6. Advantages and Limitations in Signal Processing

By integrating multiple parameters—BMD, elastic modulus, and microarchitectural indices—REMS provides a comprehensive view of bone health; however, its accuracy is sensitive to patient-specific factors (e.g., obesity, intestinal gas) and operator technique. Badea et al. (2022) noted that these factors can affect RF signal quality and measurement accuracy [

8]. Although precision values as low as 0.32–0.38% have been documented (Fuggle et al., 2024) [

22], further standardization and operator training are needed to minimize variability. Systematic reviews underscore both the promise of REMS and the need for the ongoing refinement of its algorithms [

8].

1.7. Advantages of REMS in SpA Patients

REMS offers significant benefits over DXA and qCT. Its non-ionizing ultrasound approach is safe for repeated examinations—a critical advantage for younger patients, pregnant women, and individuals requiring frequent monitoring [

8]. By assessing peripheral sites (e.g., the radius or tibia), REMS circumvents the axial skeletal artifacts (such as syndesmophytes, vertebral fusion, and calcifications) that may lead to overestimated DXA BMD values [

8,

9]. For example, Nowakowska-Płaza et al. (2021) reported that REMS identified osteoporosis in 35% of axSpA patients who were misclassified as normal by DXA [

6].

Additionally, REMS can detect extraskeletal calcifications (e.g., in the aorta or ligaments), further enhancing bone health assessment [

8]. Its ability to evaluate bone elasticity and microarchitectural integrity provides a more nuanced estimation of fracture risk than BMD alone. REMS has been validated in diverse populations—a Polish study demonstrated high diagnostic agreement with DXA [

6], and systematic reviews confirmed REMS’s strong correlation with DXA and its additional clinical value [

9,

10]. Furthermore, a recent case report by Kirilov et al. (2023) highlighted a new diagnostic aspect of REMS, reinforcing its potential to reveal subtle changes in bone quality [

28].

1.8. Evidence Supporting REMS in Osteoporosis Diagnosis and Its Use in Special Populations

A robust body of literature supports the diagnostic and prognostic utility of REMS in both primary and secondary osteoporosis. Di Paola et al. (2019) demonstrated that REMS achieved diagnostic concordance rates of approximately 89% with DXA for lumbar spine and femoral neck BMD, with correlation coefficients ranging from 0.93 to 0.94 [

3]. Cortet et al. (2021) reported sensitivity and specificity rates exceeding 90% in a large European cohort [

4]. Pisani et al. (2023) further validated the REMS-derived Fragility Score, with AUC values of 0.811 for women and 0.780 for men [

5].

1.9. REMS in Special Populations

-

Type II Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM):

Lombardi et al. (2024) demonstrated that REMS-derived BMD values were significantly lower in elderly diabetic women compared with DXA, resulting in a higher diagnostic rate of osteoporosis and suggesting greater sensitivity for diabetic osteopathy [

23].

-

Osteogenesis Imperfecta (OI):

Gonnelli et al. (2024) reported that REMS measurements in adult OI patients correlated more strongly with clinical fracture history and disease severity than DXA and were capable of differentiating between milder and more severe phenotypes [

24].

-

Anorexia Nervosa:

Caffarelli et al. (2021) found that REMS-derived Z-scores were significantly lower in adolescents with anorexia nervosa compared with healthy controls, and that REMS more effectively identified individuals with a history of fragility fractures than DXA [

25].

-

Impact of Anti-TNF Therapy:

A supplementary abstract by Icatoiu et al. (2024) in

Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases reported that anti-TNF therapy significantly improved BMD and reduced fracture risk in rheumatoid arthritis patients; an accompanying ARD BMJ supplementary abstract confirmed that REMS accurately assessed bone density in these patients despite degenerative changes [

26].

-

Additional Molecular Insights:

Mbalaviele et al. (2017) showed that IL-17 in synovial fluids is a potent stimulator of osteoclastogenesis [

10], and Lam et al. (2009) demonstrated that TNF-α induces DKK-1 expression in osteoblasts, thereby contributing to bone loss in inflammatory conditions [

13].

Meta-analyses and systematic reviews consistently conclude that REMS not only correlates strongly with DXA but also provides additional clinically relevant information on bone quality essential for accurate fracture risk prediction [

9].

1.10. Integrating REMS into Clinical Practice

National regulatory bodies in Italy and Japan have increasingly recognized REMS for osteoporosis assessment. The Italian Society of Osteoporosis, Mineral and Metabolic Diseases (SIOMMMS) has incorporated REMS into its guidelines [

27], and the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare has approved REMS for bone density evaluation [

28].

Given its numerous advantages, REMS should be integrated into routine osteoporosis screening protocols for axSpA patients—particularly when DXA results are ambiguous or compromised by artifacts. REMS can serve as a first-line diagnostic tool or complement DXA in primary care settings. Its sensitivity to subtle changes in bone quality is especially valuable for assessing the efficacy of biological therapies (e.g., anti-TNF agents, Denosumab) and antiresorptive treatments (e.g., bisphosphonates). Studies have documented significant improvements in REMS-derived stiffness scores following therapy—even when DXA BMD remains unchanged [

9,

25]. Cost-effectiveness analyses further support REMS by demonstrating reduced healthcare expenditures through decreased repeat imaging and earlier diagnosis [

29]. Recent multicenter investigations have validated REMS’s clinical benefits across diverse ethnic groups, as reflected in the Japanese guidelines [

28], while Fuggle et al. (2024) reported superior longitudinal fracture prediction compared to DXA [

20]. Furthermore, a case report by Kirilov et al. (2023) expanded the diagnostic applications of REMS by highlighting a new aspect of its use [

28]. Nevertheless, widespread adoption of REMS is currently limited by factors such as device availability, operator dependency, lack of standardized protocols, and reimbursement challenges. Future research should aim to refine REMS technology, establish uniform guidelines, expand operator training, and integrate REMS with biochemical markers of bone turnover to further enhance fracture risk prediction and therapeutic guidance [

9,

30].

The present study aims to evaluate and offer insight on the main capabilities of REMS compared to DXA in patients with SpA. The primary objective is to determine whether REMS has a higher sensibility in detecting mineral bone loss specifically for the lumbar spine, in regard to the presence of syndesmophytes or the calcification of longitudinal vertebral ligaments compared to DXA scans by measuring BMD with both methods. Secondary objectives are aimed at classifying the type of bone “age” individuals with SpA have, compared to control groups comprising patients without the presence of any inflammatory systemic disease or therapies that influence bone metabolism. Finally, this study aims to provide information on the applicability of REMS in day-to-day rheumatological practice by determining the differences between SpA patients and a group from the general population, helping describe the impact of these diseases on bone health.

2. Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional study was performed to evaluate REMS’s usefulness in diagnosing osteoporosis in individuals with axial spondyloarthritis (AxSpA). The diagnosis of AxSpA is based on the ASAS classification criteria for AxSpA approved in 2006 by the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) and the American College of Rheumatology (ACR). A total of 76 patients with AxSpA were enrolled (63 under the age of 45 and 13 above the age of 45), as well as 535 individuals in the control group (162 under 45 years and 373 above 45 years of age). The enrollment period and data gathering period were between May 2020 and August 2023 at two healthcare centers that included wards for internal medicine and rheumatology patients. One center was public, and the other private. The main inclusion criteria for both SpA patients are represented by the following:

Confirmed diagnosis of AxSpA based on ASAS classification criteria;

No former or present anti-osteoporotic or any Disease-Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drug (DMARD) treatment that can influence bone metabolism;

Had a recent DXA scan performed (less than a month) or will perform one in the future (less than a month) through recommendation and referral from a rheumatology physician based on clinical judgment;

DXA scans performed for L1-L4 lumbar vertebrae and hips;

Front and profile lumbar spine x-rays performed in the same year as normal follow-up investigations.

Exclusion criteria included the following:

Other comorbidities or medications that influence bone metabolism (e.g., Cushing’s syndrome, endocrine disorders, glucocorticoid therapy, antidepressive treatment, etc.);

No medical recommendation for DXA scan;

Patients under biological DMARDs;

Patients under classical synthetic DMARDs;

No imaging of the lumbar spine.

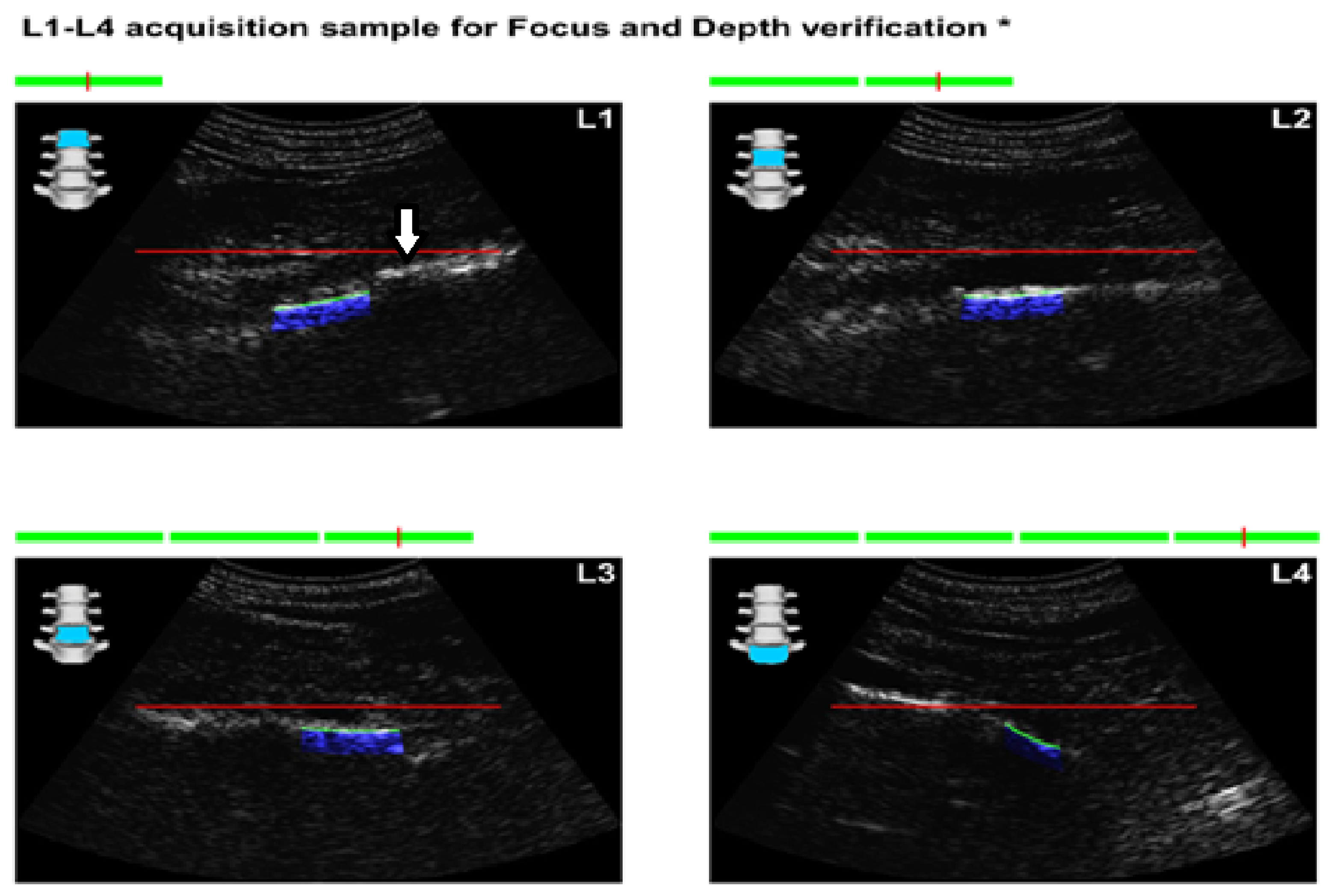

Figure 1.

Images obtained from the report form of REMS in an AxSpA patient. The arrow points at an anterior longitudinal ligament calcification that can lead to the overestimation of BMD in DXA scans.

Figure 1.

Images obtained from the report form of REMS in an AxSpA patient. The arrow points at an anterior longitudinal ligament calcification that can lead to the overestimation of BMD in DXA scans.

The recruitment of the control group was carried out on the population without any inflammatory rheumatic diseases, and they were selected after close analysis of their medical history, chronic medications, recent past medications, or current medications that could influence bone metabolism. The public hospital represented the main center where the control group was recruited from.

After careful analysis of the patient’s documents and finding individuals that respect both the inclusion and exclusion criteria, documents were checked to see if any recent DXA scans were performed. During regular clinical follow-up, frontal and profile X-rays were performed before any BMD measurement, with the main focus of describing the presence of syndesmophytes or other structural modifications of the spine (osteophytes, fragility fractures, vertebral fusion, etc.). Additionally, standard lab tests, including vitamin D testing, were performed. If the patients had no DXA scan performed and no indication of performing one, they were not included in the study. If individuals had indication for DXA scan, based on clinical judgment and an evaluation of risk factors such as smoking status, small stature, low body mass index (BMI), they were given an informed consent form and were given a full explanation of the study design, its aims, and the investigations performed. After signing, a referral for DXA analysis was given so they could perform the scan at a different accredited diagnostic center of their choosing. REMS scans were performed afterward in all patients included in the study at two centers, Dr. I. Cantacuzino Hospital Bucharest (public) and at Osteodensys private clinic in Bucharest, by trained professionals from the study team. The anatomical regions examined were the classical ones: the lumbar spine (L1–L4) and the femoral neck bilaterally.

Statistical analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel, Minitab version 20.3.0 (Minitab LLC), using

T-tests for independent variables when comparing the two main study groups in regard to age and vitamin D levels, and one-way ANOVA to compare BMD values the study groups (

Table 1). Tables and figures were created in Microsoft Excel and Minitab. Although the author fully wrote the manuscript, for clarity, Grammarly AI was used to make grammatical corrections to the text (Grammarly Inc.).

Data, including DXA BMD values, REMS BMD values, T scores, Z scores, Fragility Scores (FSs), gender, age, x-ray modifications, vitamin D levels, weight, and height, were collected in multiple Excel tabs, where sorting and initial descriptive statistics were performed. Afterward, they were transferred to Minitatab worksheets where the main statistical tests and graphs were carried out and created. Since there was no indication of the time needed to perform DXA scans, a mean value of 15 min was used based on the scientific data available at the moment in order to compare it with the acquisition time of REMS.

3. Results

After the data were acquired, values of BMD, BMI, FS, and baseline vitamin D levels (where available) were distributed according to age groups in quartiles of 10 years. The time of analysis for REMS was noted for every patient and compared to a mean value of 15 min that is usually required for DXA scans, not taking into consideration the time lost with patients requiring appointments and time lost for transit.

Descriptive analysis shows differences between the two study groups in regard to gender, with males comprising the majority of SpA patients, while the control group had a significant female population, probably because postmenopausal women have a clear recommendation for at least one baseline DXA evaluation (

Table 1).

Of the 76 patients with SpA who presented for REMS evaluation, 2 had recent vertebral fractures, where 1 classified as grade I wedge modification on the Genant scale affecting the T8 vertebra. Imaging performed during clinical practice for these patients did not show any structural modification related to AxSpA. The other patient had a grade I crush deformity on the L4 vertebra, and an X-ray showed multiple syndesmophytes in the lumbar area (

Figure 2).

Overall, REMS acquisition was faster than that of DXA, given the device’s portability. The mean time of acquisition for REMS was about 14.5 min, which can be carried out in the physician consultation room, compared to DXA, which has a mean acquisition time of about 15 min (two-sample T-test; p < 0.005). DXA also requires special measures to ensure the safety of the patient and the technician performing the examination. In addition, and this was strictly related to the study conditions, the patients were not able to undergo DXA scans at the two locations where enrollment was undertaken since neither had the hardware required, thus prolonging the theoretical time for acquisition to more than 15 min.

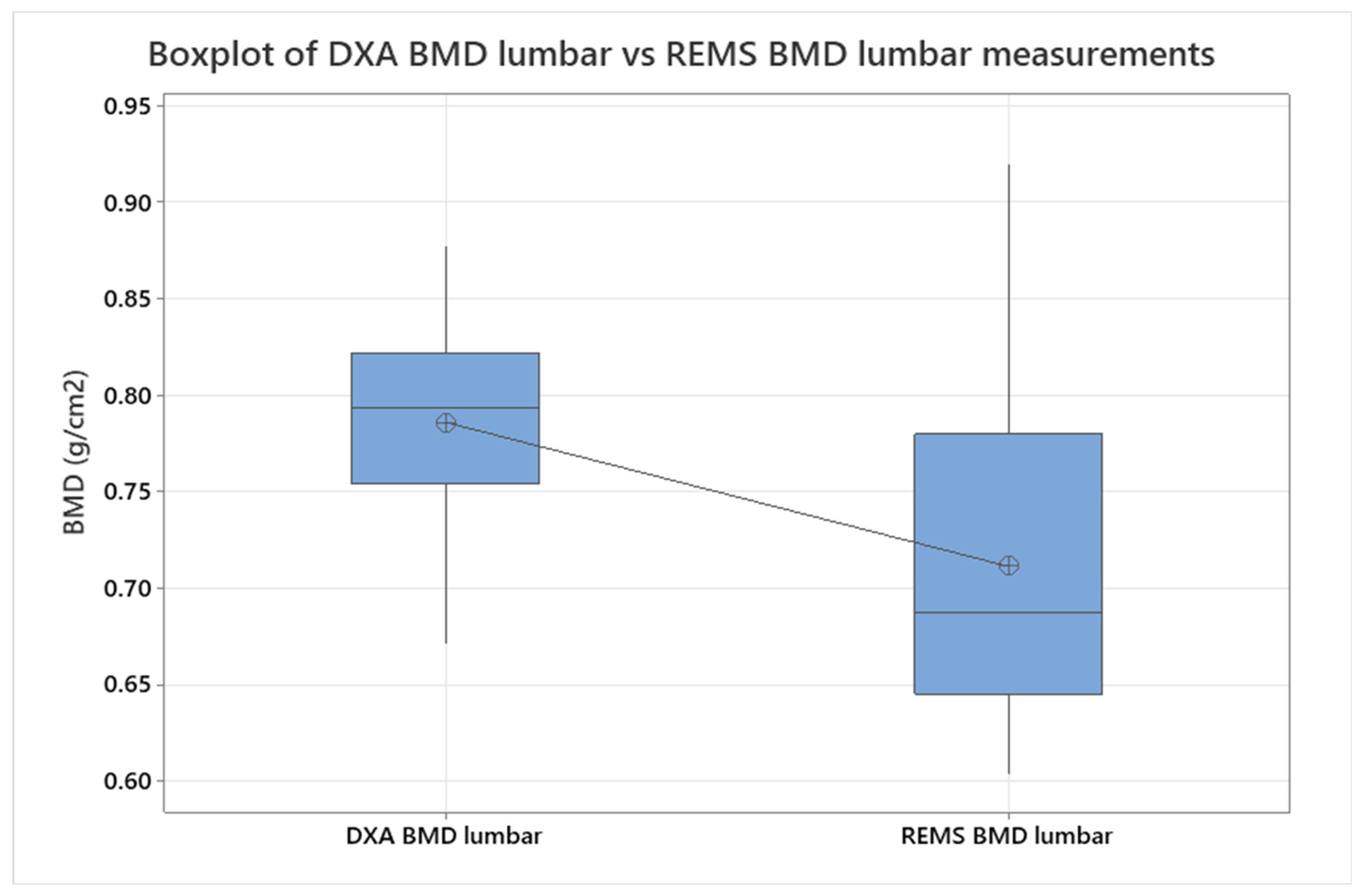

BMD data from lumbar analysis were compared between the control group and the SpA group using a two-sample T-test/Whelch (

Figure 3,

p < 0.005), showing a significant difference between BMD mean values measured with DXA vs. REMS. To refine the analysis, ANOVA was also performed for the same groups, obtaining a

p-value = 0.118. No significant differences were seen when comparing hip sites, neither in regard to DXA vs. REMS analysis nor between the control and SpA groups after only REMS measurements (two-sample T-test,

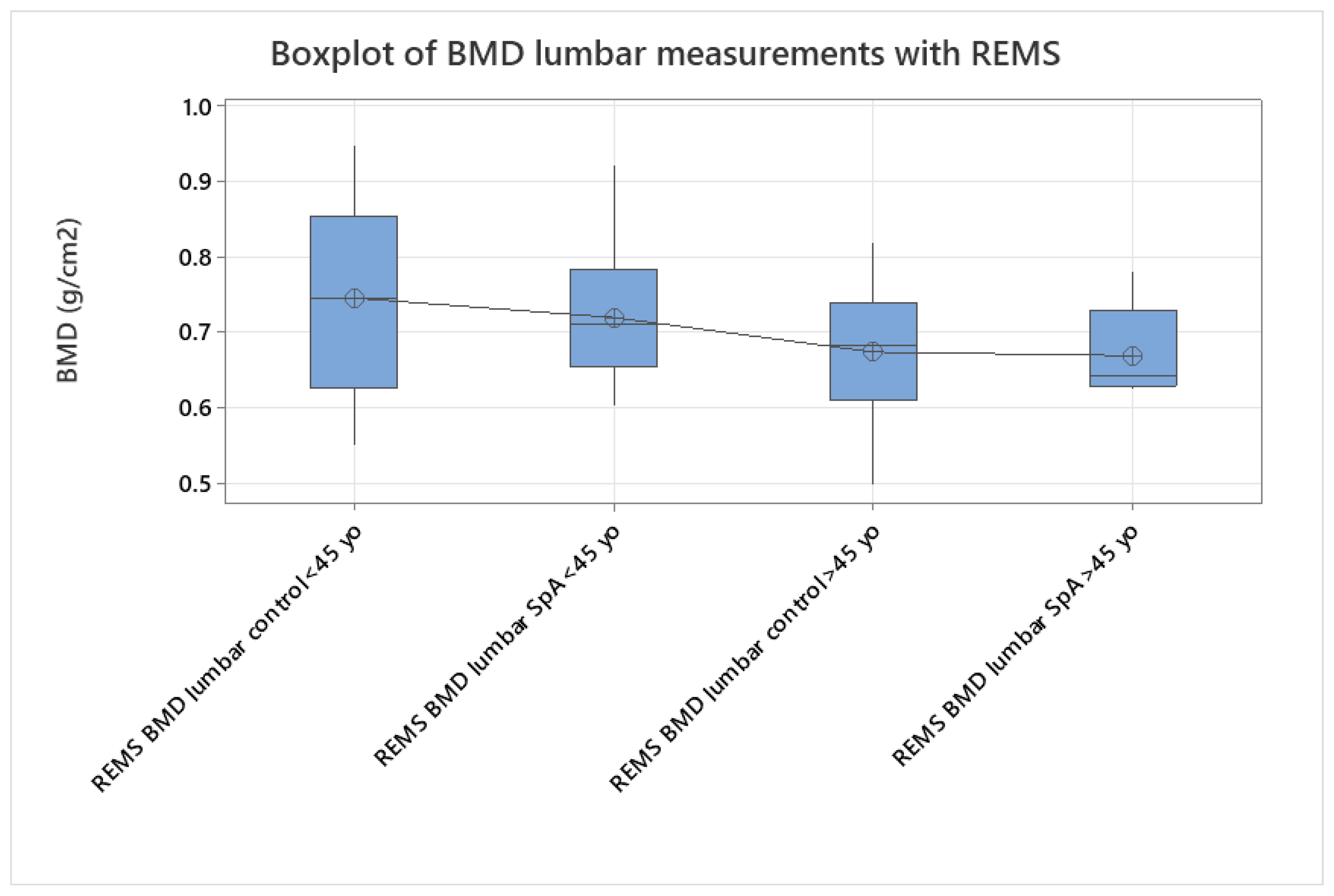

p < 0.005). We analyzed the differences between younger (under 45 yo) and older individuals (over 45 yo), comparing their BMD values measured with REMS (

Figure 4), where we found that younger patients with SpA have lower BMD values compared to their equivalent age controls. This might suggest that bone loss is present from the onset of the disease and can go unrecognized until classification criteria are met. This finding can explain the two patients described anteriorly that presented directly with vertebral fractures, with no other clinical manifestations suggestive of SpA.

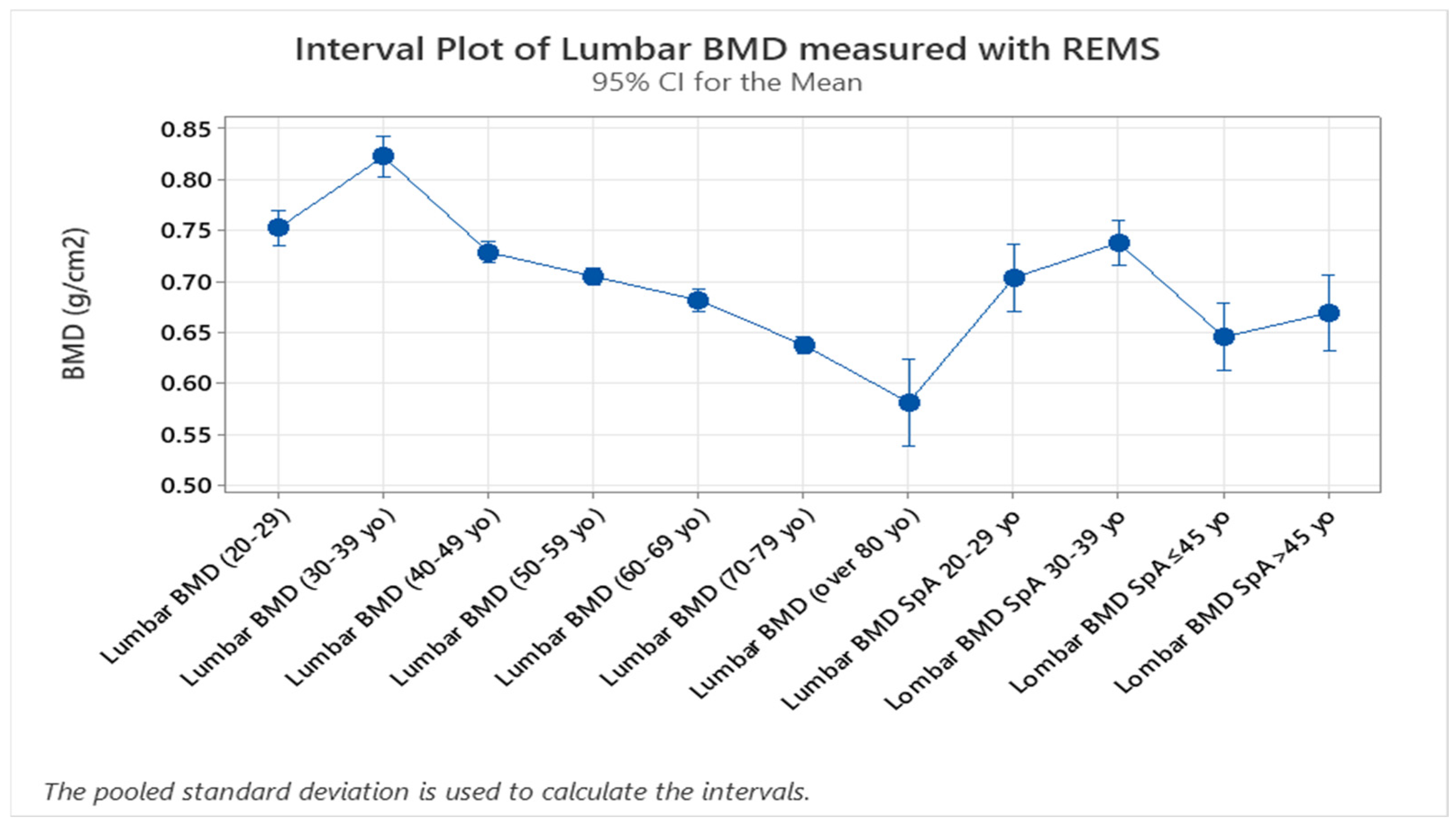

The study groups were further divided into age groups (quartiles of 10 years,

Figure 5, two-sample T-test,

p < 0.005), and a one-way ANOVA test for variance was applied to the study groups, showing a clear difference between spine BMD values and classifying values of patients with SpA as having the same bone density values as the control group with ages between 40 and 49. This might suggest that bone resorption due to chronic SpA starts in the early stages of the disease. Overall, SpA individuals showed lower BMD values compared to the specific age groups (one-way ANOVA,

p < 0.005,

Figure 5). This can be interpreted as a clear indication of significant loss of bone mass in patients with SpA. Additionally, given the fact that the BMD of the control group between 70 and 79 years of age is equivalent to the values obtained in the SpA patients with ages under 45 years, applying the two-sample T-test (

p < 0.005) proves the important impact that the disease has on bone mineralization (

Figure 5).

Additionally, vitamin D deficiency was more frequent in the SpA group compared to their specific age group, with

p < 0.005 based on one-way ANOVA testing comparing all age groups, which is a fact proved also in

Table 1, when correcting for the number of individuals enrolled in each study group.

Figure 5.

Interval plot graph obtained during one-way ANOVA statistical analysis of the 10-year groups of controls and SpA patients, defining the peak BMD values of the control group situated in the 30–39 age range compared to the much lower values obtained in the SpA group (one-way ANOVA, p < 0.005).

Figure 5.

Interval plot graph obtained during one-way ANOVA statistical analysis of the 10-year groups of controls and SpA patients, defining the peak BMD values of the control group situated in the 30–39 age range compared to the much lower values obtained in the SpA group (one-way ANOVA, p < 0.005).

4. Discussions

The higher percentage of female patients in the control group suggests the need of for BMD evaluation in females, especially after menopause. On the other hand, the SpA group had a majority of male patients, aligning with epidemiological studies that show that these types of diseases are more frequent in male populations.

The comparison between the BMD values obtained with REMS showing lower values than the control groups strengthens the claim that SpA influences bone metabolism and health, a common conclusion of most densitometric studies using DXA, REMS, and qCT. The statistical analysis comparing the DXA and REMS techniques has shown that REMS has a slightly higher sensibility in detecting bone demineralization in patients, especially in those with chronic axial involvement, making this a reliable tool for clinical use, also given its lower financial stress on public health systems. This opens up the possibility of monitoring either osteoporotic-specific treatments or DMARD treatments in specific inflammatory rheumatic diseases of the spondylarthritides group. These results might primarily stem from the ability of the method to discern between bone and other calcifications related to a multitude of pathologies. Moreover, although both methods offer results in 2D (g/cm2), the flexibility in examining vertebral sites through the angulation of the transducer and orienting ultrasound waves toward the area of interest may provide options for avoiding large calcifications or other artifact-generating conditions. Thorough preparation is needed to conduct REMS on the lumbar spine since improper dietary habits might lead to excessive gas accumulation in the bowels, which act as an ultrasonic shield, dispersing sound waves and invalidating the examination, and are a common limiter when it comes to acquisition times during the study.

The results point out the relative superiority of REMS vertebral scans compared to DXA vertebral scans in evaluating patients with SpA and vertebral modifications, as well as proving that there are no significant differences for hip scans for the two methods. As was expected, patients with SpA, especially with vertebral modifications have a lower BMD compared to patients with no structural vertebral modifications in the same age group, making their vertebra “older”. This result can be explained by the presence of the structural modification of the spine in SpA patients, such as syndesmophytes and calcifications of the longitudinal vertebral ligament, modifications that can influence BMD values of DXA scans by overestimating them. Further studies on larger populations and in a diverse range of rheumatic inflammatory diseases can provide more information in order to fully adapt the methods to the day-by-day need for rheumatology physicians. Recent scientific results make REMS a reliable method of evaluating bone health in a wider range of patients.

The study offers valuable information on the applicability of REMS in SpA patients in Romanian individuals, but multicenter trials on diverse populations from different geographical areas and of diverse ethnicities are needed to validate REMS’s diagnostic thresholds and fracture risk prediction capabilities across these diverse populations, including patients with SpA and other inflammatory rheumatic diseases.

Combining REMS data with biomarkers of bone turnover or inflammatory activity, such as beta-crosslaps and osteocalcin, could improve risk stratification for osteoporosis in individuals with SpA, representing a further improvement to the present study, emphasizing the need for a more complex methodology.

Ongoing innovations in ultrasound technology may enhance REMS’s resolution and expand its applications to other skeletal sites; the developers of this technology are already releasing software for osteoarthritis prediction capabilities.

Vitamin D deficits in the study’s geographical region are not a common finding. The presence of it when comparing it in SpA patients suggests a possible need for vitamin D supplementation, with the analysis of this aspect being currently performed. This will provide a clearer indication for vitamin D supplementation in these patients; this information has not yet been standardized and is solely left in the hands of practicing rheumatology physicians.

The main shortcomings of this study are the lack of any tests indicating bone metabolism and the absence of more complex groups and statistical comparisons, such as SpA patients with DMARD treatments versus controls and SpA patients without any treatment. Overall, this study adds to the present information in the scientific literature regarding the evaluation of patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases.

5. Conclusions

Radiofrequency Echographic Multispectrometry is a promising diagnostic tool for osteoporosis in spondylarthritis patients. Its ability to assess bone quality beyond density, its radiation-free nature, its portability, and its peripheral applicability address many challenges inherent to traditional diagnostic methods. The main advantage of REMS compared to DXA from a physician’s perspective is the ability to exclude extraosseous calcifications or formations in the analysis of BMD, being a more precise method of analysis for patients with long-standing SpA with spinal modifications. Consistent data from this study and from other scientific works aiming at evaluating bone health in AxSpA may help in accelerating the processes of adapting the method worldwide and even be fully compensated by more healthcare systems. As clinical evidence supporting REMS continues to grow, it is poised to become an integral part of osteoporosis management in SpA, improving patient outcomes through timely and accurate diagnosis.

Author Contributions

Methodology, I.-A.B., Ș.-S.A., and M.B.; software, I.-A.B.; formal analysis, I.-A.B.; investigation, I.-A.B., V.B., and C.N.; resources, M.B., V.B., G.G., and M.M.; data curation, I.-A.B.; writing—original draft, I.-A.B.; writing—review and editing, Ș.-S.A., M.B., A.-R.I., and M.-Ș.V.; supervision, Ș.-S.A. and M.B.; project administration, I.-A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not required.

Informed Consent Statement

Annexed.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Grammarly AI was used to correct grammatical errors in the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Magrey, M., & Khan, M. A. (2010). Osteoporosis in ankylosing spondylitis. Current Rheumatology Reports, 12(5), 332–336. [CrossRef]

- Mitra, D., Elvins, D. M., Speden, D. J., & Collins, A. J. (2000). The prevalence of vertebral fractures in mild ankylosing spondylitis and their relationship to bone mineral density. Rheumatology (Oxford), 39(1), 85–89.

- Di Paola, M., Gatti, D., Viapiana, O., Cianferotti, L., Cavalli, L., Caffarelli, C., Conversano, F., Quarta, E., Pisani, P., & Girasole, G. (2019). Radiofrequency echographic multispectrometry compared with dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry for osteoporosis diagnosis on lumbar spine and femoral neck. Osteoporosis International, 30(2), 391–402. [CrossRef]

- Cortet, B., Dennison, E., Diez-Perez, A., Locquet, M., Muratore, M., Nogués, X., Ovejero Crespo, D., Quarta, E., & Brandi, M. L. (2021). Radiofrequency echographic multispectrometry (REMS) for the diagnosis of osteoporosis in a European multicenter clinical context. Bone, 143, 115786. [CrossRef]

- Pisani, P., Conversano, F., Muratore, M., Adami, G., Brandi, M. L., Caffarelli, C., Casciaro, E., Di Paola, M., Franchini, R., Gatti, D., Gonnelli, S., Guglielmi, G., Lombardi, F. A., Natale, A., Testini, V., & Casciaro, S. (2023). Fragility Score: A REMS-based indicator for the prediction of incident fragility fractures at 5 years. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research, 35(4), 763–773. [CrossRef]

- Nowakowska-Płaza, A., Wroński, J., Płaza, M., Sudoł-Szopińska, I., & Głuszko, P. (2021). Diagnostic agreement between radiofrequency echographic multispectrometry and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry in the assessment of osteoporosis in a Polish group of patients. Polish Archives of Internal Medicine, 131(9), 840–847. [CrossRef]

- Amorim DMR, Sakane EN, Maeda SS, Lazaretti Castro M. New technology REMS for bone evaluation compared to DXA in adult women for the osteoporosis diagnosis: a real-life experience. Arch Osteoporos. 2021 Nov 16;16(1):175. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishizu, H., Shimizu, T., Sakamoto, Y., Toyama, F., Kitahara, K., Takayama, H., Miyamoto, M., & Iwasaki, N. (2024). Radiofrequency Echographic Multispectrometry (REMS) can overcome the effects of structural internal artifacts and evaluate bone fragility accurately. Calcified Tissue International, 114(3), 246–254. [CrossRef]

- Diez-Perez, A., Naylor, K. E., Abrahamsen, B., Agnusdei, D., Brandi, M. L., Cooper, C., Dennison, E., Eriksen, E. F., Gold, D. T., Guañabens, N., Hadji, P., Hiligsmann, M., Horne, R., Josse, R., Kanis, J. A., Obermayer-Pietsch, B., Prieto-Alhambra, D., Reginster, J. Y., Rizzoli, R., Silverman, S., … Adherence Working Group of the International Osteoporosis Foundation and the European Calcified Tissue Society. (2017). Recommendations for the screening of adherence to oral bisphosphonates. Osteoporosis International, 28(3), 767–774. [CrossRef]

- Al Refaie A, Baldassini L, Mondillo C, Giglio E, De Vita M, Tomai Pitinca MD, Gonnelli S, Caffarelli C. Radiofrequency Echographic Multi Spectrometry (R.E.M.S.): New Frontiers for Ultrasound Use in the Assessment of Bone Status-A Current Picture. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023 May 9;13(10):1666. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Badea, I.A., Bojinca M., Milicescu M., Vutcanu O., Ilina A.R. (2022). Literature review of Radiofrequency Echographic Multi-Spectrometry (REMS) in the diagnosis of osteoporosis and bone fragility, : Ro J Rheumatol. 2022;31(1). [CrossRef]

- Fassio, F. Pollastri, C. Benini, I. Galvagni, C. Dartizio, D. Gatti, M. Rossini, O. Viapiana, G. Adami. POS0296 Radiofrequency Echographic Multi-Spectrometry (REMS) and DXA for the evaluation of Bone Mineral Density in Axial Spondyloarthritis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. Volume 83, Supplement 1, 2024, Page 470, ISSN 0003-4967. [CrossRef]

- Mbalaviele, G., Novack D.V., Schett G., Teitelbaum S.L. (2017). Inflammatory osteolysis: a conspiracy against bone. J Clin Invest. 2017;127(6):2030–2039. [CrossRef]

- Li S, Yin Y, Yao L, Lin Z, Sun S, Zhang J, Li X. TNF-α treatment increases DKK1 protein levels in primary osteoblasts via upregulation of DKK1 mRNA levels and downregulation of miR-335-5p. Mol Med Rep. 2020 Aug;22(2):1017-1025. Epub 2020 May 18. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- van der Heijde, D., et al. (2008). Radiographic progression in ankylosing spondylitis over 12 years: Results from the OASIS study. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 67(5), 577–583.

- Björk, M., Dragioti, E., Alexandersson, H., Esbensen, B.A., Boström, C., Friden, C., Hjalmarsson, S., Hörnberg, K., Kjeken, I., Regardt, M., Sundelin, G., Sverker, A., Welin, E. and Brodin, N. (2022), Inflammatory Arthritis and the Effect of Physical Activity on Quality of Life and Self-Reported Function: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Arthritis Care Res, 74: 31-43. [CrossRef]

- van Staa, T. P., et al. (2000). Use of oral corticosteroids and risk of fractures. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, 15(6), 993–1000.

- Cai G, Wang L, Fan D, Xin L, Liu L, Hu Y, Ding N, Xu S, Xia G, Jin X, Xu J, Zou Y, Pan F. Vitamin D in ankylosing spondylitis: review and meta-analysis. Clin Chim Acta. 2015 Jan 1;438:316-22. Epub 2014 Sep 6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulyás K, Horváth Á, Végh E, Pusztai A, Szentpétery Á, Pethö Z, Váncsa A, Bodnár N, Csomor P, Hamar A, Bodoki L, Bhattoa HP, Juhász B, Nagy Z, Hodosi K, Karosi T, FitzGerald O, Szücs G, Szekanecz Z, Szamosi S, Szántó S. Effects of 1-year anti-TNF-α therapies on bone mineral density and bone biomarkers in rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Rheumatol. 2020 Jan;39(1):167-175. Epub 2019 Sep 14. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuggle, N., Reginster, JY., Al-Daghri, N. et al. Radiofrequency echographic multi spectrometry (REMS) in the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis: state of the art. Aging Clin Exp Res 36, 135 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Bruckmann, N. M., Rischpler, C., Tsiami, S., Kirchner, J., Abrar, D. B., Bartel, T., Theysohn, J., Umutlu, L., Herrmann, K., Fendler, W. P., Buchbender, C., Antoch, G., Sawicki, L. M., Tsobanelis, A., Braun, J., & Baraliakos, X. (2022). Effects of Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor Therapy on Osteoblastic Activity at Sites of Inflammatory and Structural Lesions in Radiographic Axial Spondyloarthritis: A Prospective Proof-of-Concept Study Using Positron Emission Tomography/Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Sacroiliac Joints and Spine. Arthritis & rheumatology (Hoboken, N.J.), 74(9), 1497–1505. [CrossRef]

- Fassio, A., et al. (2023). Role of REMS in the assessment of bone mineral density in patients with chronic kidney disease undergoing peritoneal dialysis: A pilot study. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research, 35, 185–192. [CrossRef]

- F.A. Lombardi, P. Pisani, F. Conversano, C. Stomaci, E. Casciaro, M. Muratore, M. Di Paola, S. Casciaro, AB0312 REMS TECHNOLOGY FOR THE ASSESSMENT OF THE EFFECT OF DMT2 ON BONE HEALTH, Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, Volume 83, Supplement 1, 2024, Page 1399, ISSN 0003-4967. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0003496724169968). [CrossRef]

- Gonnelli S., Caffarelli C. Radiofrequency echographic multispectrometry (REMS) in rare bone conditions. Int J Bone Frag. 2024; 4(1):26-31. [CrossRef]

- Caffarelli, C., et al. (2021). Assessment of bone status using REMS in adolescent patients with anorexia nervosa. Eating and Weight Disorders – Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 27(6), 3207–3213. [CrossRef]

- Icatoiu, E., Cobilinschi, C., Bălănescu, A., et al. (2024). Bone density in rheumatoid arthritis assessed by radiofrequency echographic multispectrometry: How frequent are osteopenia and osteoporosis? Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 83, 1394–1395.

- SIOMMMS Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Osteoporosis. (2020). Italian Society of Osteoporosis, Mineral and Metabolic Diseases. Retrieved from https://www.siommms.it.

- Guidelines on the Diagnosis and Management of Osteoporosis. (2019). Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan. Retrieved from https://www.mhlw.go.jp.

- Reginster, J. Y., Silverman, S. L., Alokail, M., Al-Daghri, N., & Hiligsmann, M. (2024). Cost-effectiveness of radiofrequency echographic multi-spectrometry for the diagnosis of osteoporosis in the United States. JBMR plus, 9(1), ziae138. [CrossRef]

- Kirilov, N., Bischoff, F., Vladeva, S., & Bischoff, E. (2023). A case showing a new diagnostic aspect of the application of radiofrequency echographic multi-spectrometry (REMS). Diagnostics, 13(20), 3224. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).