Submitted:

18 February 2025

Posted:

19 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

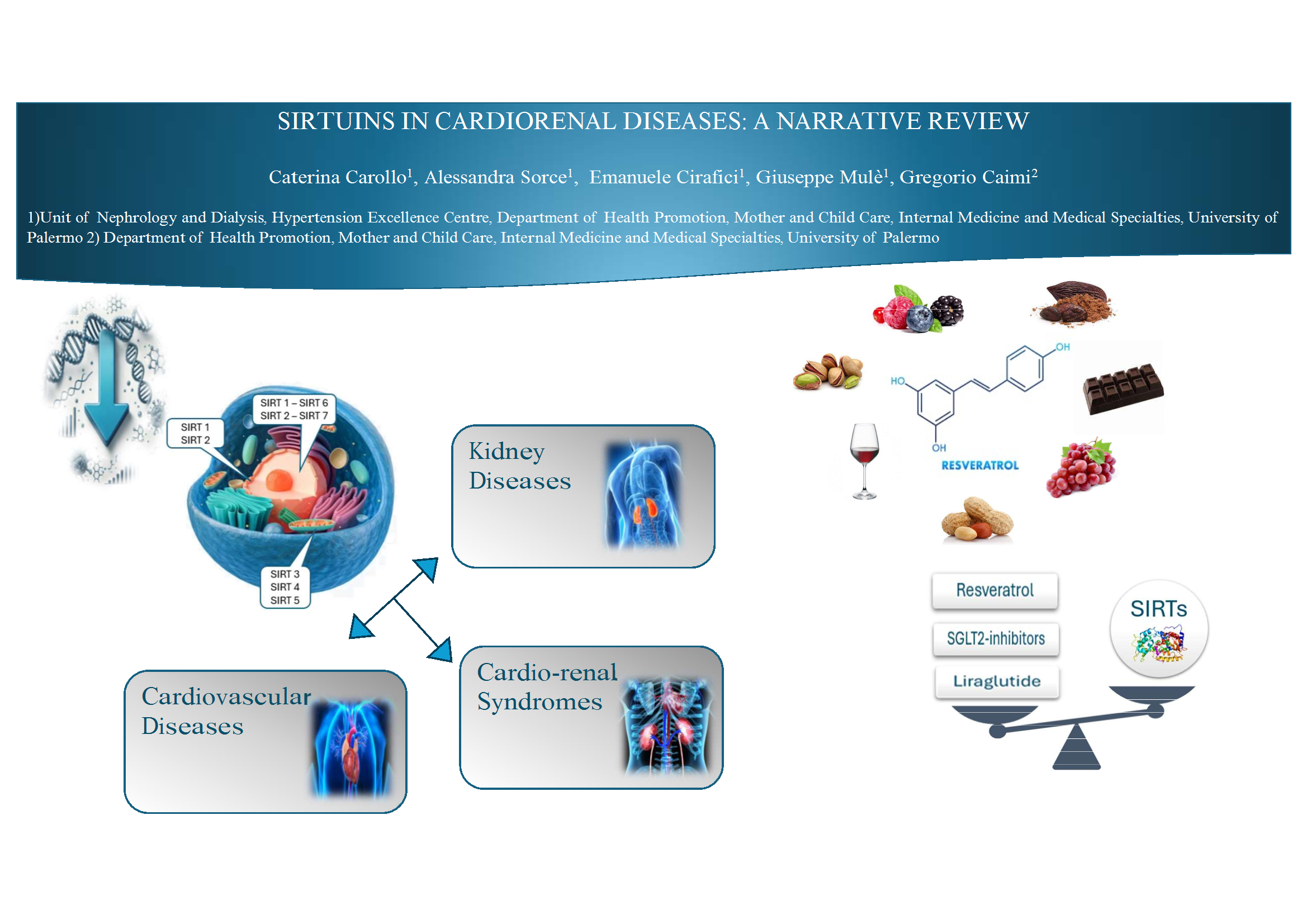

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Sirtuins in Kidney Diseases

Sirtuins and Cardiovascular Diseases

Sirtuins and Cardio-Renal Diseases

Resveratrol and Sirtuins Agonists in Cardio-Renal Diseases

Conclusions and Future Directions

References

- Carollo, C.; Urso, C.; Lo Presti, R.; Caimi, G. Sirtuins and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Food and Nutrition Sciences 2018, 9, 1254–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carollo, C.; Firenze, A.; Caimi, G. Sirtuins and Aging: Is there a Role for Resveratrol? International Journal of Advanced Nutritional and Health Science 2016, 4, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michishita, E.; Park, J.Y.; Burneskis, J.M.; Barrett, J.C.; Horikawa, I. Evolutionarily conserved and non conserved cellular localizations and functions of human SIRT proteins. Mol Biol Cell 2005, 16, 4623–4635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balaban, R.S.; Nemoto, S.; Finkel, T. Mitochondria, oxidants, and aging. Cell 2005, 120, 483–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group 2024. Kidney International 2024, 105 (Suppl. 4S), S117–S314. [CrossRef]

- Abdel Kader, K. Symptoms with or because of Kidney Failure? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2022, 17, 475–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Renal Data System 2023.

- Nitta, K.; Okada, K.; Yanai, M.; Takahashi, S. Aging and chronic kidney disease. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2013, 38, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenvinkel, P.; Larsson, T.E. Chronic kidney disease: A clinical model of premature aging. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013, 62, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooman, J.P.; van der Sande, F.M.; Leunissen, K.M. Kidney disease and aging: A reciprocal relation. Exp Gerontol. 2017, 87, 156–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morigi, M.; Perico, L.; Benigni, A. Sirtuins in Renal Health and Disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2018, 29, 1799–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y.J.; Lee, A.S.; Nguyen-Thanh, T.; Kim, D.; Kang, K.P.; Lee, S.; et al. SIRT2 Regulates LPS-Induced Renal Tubular CXCL2 and CCL2 Expression. J Am Soc Nephrol 2015, 26, 1549–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michishita, E.; Park, J.Y.; Burneskis, J.M.; Barrett, J.C.; Horikawa, I. Evolutionarily conserved and nonconserved cellular localizations and functions of human SIRT proteins. Mol Biol Cell. 2005, 16, 4623–4635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyama, T.; Kume, S.; Koya, D.; Araki, S.; Isshiki, K.; Chin-Kanasaki, M.; et al. SIRT3 Attenuates Palmitate-Induced ROS Production and Inflammation in Proximal Tubular Cells. Free Radic Biol Med 2011, 51, 1258–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiba, T.; Peasley, K.D.; Cargill, K.R.; Maringer K v Bharathi, S.S.; Mukherjee, E.; et al. Sirtuin 5 Regulates Proximal Tubule Fatty Acid Oxidation to Protect Against AKI. J Am Soc Nephrol 2019, 30, 2384–2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyasato, Y.; Yoshizawa, T.; Sato, Y.; Nakagawa, T.; Miyasato, Y.; Kakizoe, Y.; et al. Sirtuin 7 Deficiency Ameliorates Cisplatin-Induced Acute Kidney Injury Through Regulation of the Inflammatory Response. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 5927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitada, M.; Kume, S.; Koya, D. Role of sirtuins in kidney disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2014, 23, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, W.K.; Erion, K.; Florez, J.C.; Hattersley, A.T.; Hivert, M.F.; Lee, C.G.; McCarthy, M.I.; Nolan, J.J.; Norris, J.M.; Pearson, E.R.; Philipson, L.; McElvaine, A.T.; Cefalu, W.T.; Rich, S.S.; Franks, P.W. Precision Medicine in Diabetes: A Consensus Report From the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care. 2020, 43, 1617–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Lee, K.; He, J.C. SIRT1 is a potential drug target for treatment of diabetic kidney disease. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2018, 9, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong YJLiu, N.; Xiao, Z.; Sun, T.; Wu, S.H.; Sun, W.X.; Xu, Z.G.; Yuan, H. Renal protective effect of Sirtuin 1. J Diabetes Res. 2014, 2014, 843786. [Google Scholar]

- Bian, C.; Ren, H. Sirtuin Family and Diabetic Kidney Disease. Front Endocrinol 2022, 13, 901066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, K.; Wakino, S.; Simic, P.; Sakamaki, Y.; Minakuchi, H.; Fujimura, K.; Hosoya, K.; Komatsu, M.; Kaneko, Y.; Kanda, T.; Kubota, E.; Tokuyama, H.; Hayashi, K.; Guarente, L.; Itoh, H. Renal tubular SIRT1 attenuates diabetic albuminuria by epigenetically suppressing Claudin-1 overexpression in podocytes. Nat Med 2013, 19, 1496–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, R.; Chen, J.; Hu, Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, S.; Shetty, S.; Fu, J. SIRT1 Deletion leads to enhanced inflammation and aggravates endotoxin -induced acute kidney injury. PLoS ONE, 2014, 9, e98909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Lin, Z.; Xiao, H.; Xu, Z.; Li, C.; Zeng, J.; Xie, X.; Deng, L.; Huang, H. Fyn deficiency inhibits oxidative stress by decreasing c-Cbl-mediated ubiquitination of Sirt1 to attenuate diabetic renal fibrosis. Metabolism 2023, 139, 155378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, J.; Lu, L.; Huang, T.; Hou, W.; Wang, F.; Yu, L.; Wu, F.; Qi, J.; Chen, X.; et al. Sirt7 associates with ELK1 to participate in hyperglycemia memory and diabetic Nephropathy via modulation of DAPK3 expression and endothelial inflammation. Transl Res. 2022, 247, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Z.; Sun, M.; Wu, J.; Fang, H.; Cai, S.; An, S.; Huang, Q.; Chen, Z.; Wu, C.; Zhou, Z.; et al. SIRT1 attenuates sepsis-induced acute kidney injury via Beclin1 deacetylation-mediated autophagy activation. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, K.A.; Huynh, F.K.; Fisher-Wellman, K.; Stuart, J.D.; Peterson, B.S.; Douros, J.D. SIRT4 Is a lysine deacylase that controls leucine metabolism and insulin secretion. Cell Metab 2017, 25, 838–855.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picard, F.; Kurtev, M.; Chung, N.; Topark-Ngarm, A.; senawong, T.; Machado De Oliveira, R.; et al. SIRT1 promotes fat mobilization in white adipocytes by repressing PPAR gamma. Nature 2004, 429, 771–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillum, M.P.; Kotas, M.E.; Erion, D.M.; Kursawe, R.; Chatterjee, P.; Nead, K.T.; et al. SIRT1 regulates adipose tissue inflammation. Diabetes 2011, 60, 3100–3102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutkowski, J.M.; Wang, Z.V.; Park, A.S.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, D.; Hu, M.C.; et al. Adiponectin promotes functional recovey after podocyte ablation. JASN 2013, 24, 268–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, T.; Lomb, D.J.; Haigis, M.C.; Guarente, L. SIRT5 deacetylates carbamoyl phosphate synthetase 1 and regulates the urea cycle. Cell 2009, 137, 560–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rardin, M.J.; He, W.; Nishida, Y.; Newman, J.C.; Carrico, C.; Danielson, S.R. SIRT5 regulates the mitochondrial lysine succinylome and metabolic networks. Cell Metab 2013, 18, 920–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Zhou, Y.; Su, X.; Yu, J.J.; Khan, S.; Jiang, H. Sirt5 is a NAD-dependent protein lysine demalonylase and desuccinylase. Science 2011, 334, 806–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jian, Y.; Yang, Y.; Cheng, L.; Yang, X.; Liu, H.; Li, W.; Wan, Y.; Yang, D. Sirt3 mitigates LPS-induced mitochondrial damage in renal tubular epithelial cells by deacetylating YME1L1. Cell Prolif. 2023, 56, e13362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, Y.; Lee, K.; He, J.C. SIRT1 Is a Potential Drug Target for Treatment of Diabetic Kidney Disease. Front Endocrinol 2018, 9, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Fu Yc Chen, C.J.; Wang, X.; Wang, W. SIRT1, a novel target to prevent atherosclerosis. J Cell Biochem 2009, 108, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Wang, J.; He, J.C.; Zhong, Y. Sirtuin 1 in Chronic Kidney Disease and Therapeutic Potential of Targeting Sirtuin 1. Front Endocrinol 2022, 13, 917773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takemura, A.; Iijima, K.; Ota, H.; Son, B.K.; Ito, Y.; Ogawa, S.; et al. Sirtuin 1 Retards Hyperphosphatemia-Induced Calcification of Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2011, 31, 2054–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dioum, E.M.; Chen, R.; Alexander, M.S.; Zhang, Q.; Hogg, R.T.; Gerard, R.D.; et al. : Regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor 2alpha signaling by the stress-responsive deacetylase sirtuin 1. Science 2009, 324, 1289–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Q.; Ma, F.; Liu, T. Sirtuins in kidney diseases: Potential mechanism and therapeutic targets. Cell Commun Signal 2024, 22, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasko, R.; Xavier, S.; Chen, J.; Lin, C.H.; Ratliff, B.; Rabadi, M.; et al. Endothelial Sirtuin 1 Deficiency Perpetrates Nephrosclerosis Through Downregulation of Matrix Metalloproteinase-14: Relevance to Fibrosis of Vascular Senescence. J Am Soc Nephrol JASN 2014, 25, 276–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponnusamy, M.; Zhou, X.; Yan, Y.; Tang, J.; Tolbert, E.; Zhao, T.C.; Gong, R.; Zhuang, S. Blocking sirtuin 1 and 2 inhibits renal interstitial fibroblast activation and attenuates renal interstitial fibrosis in obstructive Nephropathy. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2014, 350, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Wen, P.; Luo, J.; Ding, H.; Cao, H.; He, W.; Zen, K.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, J.; Jiang, L. Sirtuin 3 regulates mitochondrial protein acetylation and metabolism in tubular epithelial cells during renal fibrosis. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Liu, H.; Zhu, S.; Woodson, M.; Liu, R.; Tilton, R.G.; Miller, J.D.; Zhang, W. Sirt6 deficiency results in progression of glomerular injury in the kidney. Aging 2017, 9, 1069–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.; Liu, H.; Zhu, S.; Woodson, M.; Liu, R.; Tilton, R.G.; et al. Sirt6 Deficiency Results in Progression of Glomerular Injury in the Kidney. Aging 2017, 9, 1069–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, J.; Liu, Z.; Huang, X.; Shu, S.; Hu, X.; Zheng, M.; et al. The Deacetylase Sirtuin 6 Protects Against Kidney Fibrosis by Epigenetically Blocking β-Catenin Target Gene Expression. Kidney Int 2020, 97, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, W.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, W.; Huang, H. SIRT6 overexpression retards renal interstitial fibrosis through targeting HIPK2 in chronic Kidney Disease. Front Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1007168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, J.; Chen, Y.; Jing, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, C.; Hao, Z.; Zhang, L. Sirtuin 3 suppresses the formation of renal calcium oxalate crystals through promoting M2 polarization of macrophages. J Cell Physiol. 2019, 234, 11463–11473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-H.; Zhang, Y.-X.; Lv, J.-L.; Liu, Y.-Y.; Guo, J.-Y.; Zhao, L.; Nan, Y.-X.; Wu, Q.-J.; Zhao, Y.-H. Role of sirtuins in metabolic disease-related renal injury. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2023, 161. [Google Scholar]

- Ozkan Kurtgoz, P.; Karakose, S.; Cetinkaya, C.D.; et al. Evaluation of sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) levels in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Int Urol Nephrol 2022, 54, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Fan, L.X.; Sweeney, W.E.; Denu, J.M.; Avner, E.D.; Li, x. Sirtuin 1 inhibition delays cyst formation in autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Clin Invest 2013, 123, 3084–3098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, H.; Hong, Y.; Lu, X.; Zhang, J.; Chen, H.; Li, Y.; et al. SIRT2 mediates oxidative stress-induced apoptosis of differentiated PC12 cells. Neuroreport 2014, 25, 838–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kume, S.; Uzu, T.; Horiike, K.; Chin-Kanasaki, M.; Isshiki, K.; Araki, S.; Sugimoto, T.; Haneda, M.; Kashiwagi, A.; Koya, D. Calorie restriction enhances cell adaption to hypoxia through SIRT1-dependent mitochondrial autophagy in mouse aged kidney. J Clin Invest 2010, 120, 1043–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Che, R.; Wang, P.; Zhang, A. Mitochondrial dysfunction in the pathophysiology of renal diseases. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2024, 326, F768–F779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth, G.A.; Mensah, G.A.; Johnson, C.O.; et al. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risk factors, 1990-2019: Update from the GBD 2019 study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 2982–3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.P.; Zhai, P.; Yamamoto, T.; Maejima, Y.; Matsushima, S.; Hariharan, N.; Shao, D.; Takagi, H.; Oka, S.; Sadoshima, J. Silent information regulator 1 protects the heart from ischemia/reperfusion. Circulation 2010, 122, 2170–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, G.A.; Urciuoli, W.R.; Brookes, P.S.; Nadtochiy, S.M. SIRT3 deficiency exacerbates ischemia-reperfusion injury: Implication for aged hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2014, 306, H1602–H1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.X.; Wang, X.L.; Tong, M.M.; et al. SIRT6 protects cardiomyocytes against ischemia/reperfusion injury by augmenting FoxO3α-dependent antioxidant defense mechanisms. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2016, 111, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcendor, R.R.; Gao, S.; Zhai, P.; Zablocki, D.; Holle, E.; Yu, X.; Tian, B.; Wagner, T.; Vatner, S.F.; Sadoshima, J. Sirt1 regulates aging and resistance to oxidative stress in the heart. Circ Res 2007, 100, 1512–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaresan, N.R.; Gupta, M.; Kim, G.; Rajamohan, S.B.; Isbatan, A.; Gupta, M.P. Sirt3 blocks the cardiac hypertrophic response by augmenting Foxo3a-dependent antioxidant defense mechanisms in mice. J Clin Invest 2009, 119, 2758–2771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaresan, N.R.; Vasudevan, P.; Zhong, L.; Kim, G.; Samant, S.; Parekh, V.; Pillai, V.B.; Ravindra, P.V.; Gupta, M.; Jeevanandam, V.; Cunningham, J.M.; Deng, C.X.; Lombard, D.B.; Mostoslavsky, R.; Gupta, M.P. The sirtuin SIRT6 blocks IGF-Akt signaling and development of cardiac hypertrophy by targeting c-Jun. Nat Med 2012, 18, 1643–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynn, E.G.; McLeod, C.J.; Gordon, J.P.; Bao, J.; Sack, M.N. SIRT2 is a negative regulator of anoxia-reoxygenation tolerance via regulation of 14-3-3 zeta and BAD in H9c2 cells. FEBS Lett 2008, 582, 2857–2862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-P.; Wen, R.; Liu, C.-F.; Zhang, T.-N.; Yang, N. Cellular and molecular biology of sirtuins in cardiovascular disease. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2023, 164, 114931. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.; Li, Y.; Xie, Y.; Bu, J.; Yuan, R.; Zhang, X. Exploring Sirtuins: New Frontiers in Managing Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2024, 25, 7740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Böhm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Čelutkienė, J.; Chioncel, O.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: Developed by the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. (Engl. Ed.) 2022, 75, 523. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wu, Q.-J.; Zhang, T.-N.; Chen, H.-H.; Yu, X.-F.; Lv, J.-L.; Liu, Y.-Y.; Liu, Y.-S.; Zheng, G.; Zhao, J.-Q.; Wei, Y.-F.; et al. The sirtuin family in health and disease. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 402. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zeisberg, E.M.; Tarnavski, O.; Zeisberg, M.; Dorfman, A.L.; McMullen, J.R.; Gustafsson, E.; Chandraker, A.; Yuan, X.; Pu, W.T.; Roberts, A.B.; Neilson, E.G.; Sayegh, M.H.; Izumo, S.; Kalluri, R. Endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition contributes to cardiac fibrosis. Nat Med 2007, 13, 952–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeisberg, E.M.; Potenta, S.E.; Sugimoto, H.; Zeisberg, M.; Kalluri, R. Fibroblasts in kidney fibrosis emerge via endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition. J Am Soc Nephrol 2008, 19, 2282–2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kizu, A.; Medici, D.; Kalluri, R. Endothelial-mesenchymal transition as a novel mechanism for generating myofibroblasts during diabetic nephropathy. Am J Pathol 2009, 175, 1371–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardali, E.; Sanchez-Duffhues, G.; Gomez-Puerto, M.C.; Ten Dijke, P. TGF-beta-Induced endothelial-mesenchymal transition in fibrotic diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Wang, F.; Zha, S.; Cao, Q.; Sheng, J.; Chen, S. SIRT1 inhibits TGF-β-induced endothelial-mesenchymal transition in human endothelial cells with Smad4 deacetylation. J Cell Physiol 2018, 233, 9007–9014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.R.; Zheng, Y.J.; Zhang, Z.B.; Shen, W.L.; Li, X.D.; Wei, T.; Ruan, C.C.; Chen, X.H.; Zhu, D.L.; Gao, P.J. Suppression of Endothelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition by SIRT (Sirtuin) 3 Alleviated the Development of Hypertensive Renal Injury. Hypertension 2018, 72, 350–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Valero, B.; Cachofeiro, V.; Martínez-Martínez, E. Fibrosis, the Bad Actor in Cardiorenal Syndromes: Mechanisms Involved. Cells 2021, 10, 1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iside, C. Sirtuin 1 activation by natural phytochemicals: An overview. Front Pharmacol 2020, 11, 1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, W.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, X.; Chen, N. Resveratrol combats chronic diseases through enhancing mitochondrial quality. Food Science and Human Wellness 2024, 13, 597–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, D.; Capili, A.; Choi, M.E. Mitochondrial dysfunction in kidney injury, inflammation, and disease: Potential therapeutic approaches. Kidney Res Clin Pract. 2020, 39, 244–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.-H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Fan, X.-F.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Gong, Y.-S.; Han, L.-P. SIRT1 activation attenuates cardiac fibrosis by endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2019, 118. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Y.; Du, C.; Shi, Y.; Wei, J.; Wu, H.; Cui, H. . The Sirt 1 activator, SRT1720, attenuates renal fibrosis by inhibiting CTGF and oxidative stress. Int J Mol Med 2017, 39, 1317–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Ortiz, K.; Pérez-Vázquez, V.; Macías-Cervantes, M.H. Exercise and Sirtuins: A Way to Mitochondrial Health in Skeletal Muscle. Int J Mol Sci. 2019, 20, 2717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, J.Y.; Choi, S.E.; Ha, E.S.; Lee, H.B.; Kim, T.H.; Han, S.J.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, D.J.; Kang, Y.; Lee, K.W. Role of liraglutide in brain repair promotion through Sirt1-mediated mitochondrial improvement in stroke. Int J Mol Med. 2019, 44, 1161–1171. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Liu, H.; Takagi, S.; Nitta, K.; Kitada, M.; Srivastava, S.P.; Takagaki, Y.; Kanasaki, K.; Koya, D. Renal protective effects of empagliflozin via inhibition of EMT and aberrant glycolysis in proximal tubules. JCI Insight. 2020, 5, e129034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osataphan, S.; Macchi, C.; Singhal, G.; Chimene-Weiss, J.; Sales, V.; Kozuka, C.; Dreyfuss, J.M.; Pan, H.; Tangcharoenpaisan, Y.; Morningstar, J. SGLT2 inhibition reprograms systemic metabolism via FGF21-dependent and -independent mechanisms. JCI Insight. 2019, 4, e123130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Packer, M. Cardioprotective effects of sirtuin-1 and its downstream effectors: Potential role in mediating the heart failure benefits of SGLT2 (Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter 2) inhibitors. Circ Heart Fail. 2020, 13, e007197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Mukherjee, M.; Kumar, A.; Sharma, G.; Tabassum, F.; Akhtar, S.; Imam, M.T.; Saeed Almalki, Z.S. Preliminary investigation on impact of intergenerational treatment of resveratrol endorses the development of 'super-pups'. Life Sci 2023, 314, 121322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirmiran, P.; Yuzbashian, E.; Rahbarinejad, P.; Asghari, G.; Azizi, F. Dietary Intakes of Total Polyphenol and Its Subclasses in Association with the Incidence of Chronic Kidney Diseases: A Prospective Population-based Cohort Study. Res. Sq. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Peng, W.; Hu, F.; Li, G. Association between dietary intake of flavonoid and chronic kidney disease in US adults: Evidence from NHANES 2007-2008, 2009-2010, and 2017-2018. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0309026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arisi, T.O.P.; da Silva, D.S.; Stein, E.; Weschenfelder, C.; de Oliveira, P.C.; Marcadenti, A.; Lehnen, A.M.; Waclawovsky, G. Effects of cocoa consumption on cardiometabolic risk markers: Protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najjar, R.S.; Turner, C.G.; Wong, B.J.; Feresin, R.G. Berry-Derived Polyphenols in Cardiovascular Pathologies: Mechanisms of Disease and the Role of Diet and Sex. Nutrients 2021, 13, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).