1. Introduction

Modeling virtual elements to simulate real scenarios represents a significant reform in engineering education. This method addresses specific challenges encountered during practical training, such as limited equipment and the potential risks of certain operations [

1,

2,

3]. Consequently, it is necessary to integrate virtual elements into practice courses. According to information reviewed, the most important advantage of integrating virtual elements into practice courses lies in promoting interactivity [

4,

5,

6]. For example, HAI C.P. et al. [

7] from Chung-ang University in South Korea developed a Virtual Field Trip System (VIFITS) utilizing 360-degree panoramic virtual reality for the purpose of safety education among construction engineering students. The theoretical framework, system architecture and design prototype of the VIFITS are elucidated in detail. Through questionnaires and interviews they objectively evaluated its efficacy and limitations compared with traditional pedagogical methods. They concluded that VIFITS provided an interactive environment to improve students’ practical ability and safety knowledge. Clemson University [

8] in the United States developed a virtual reality-based learning system for mechanical engineering undergraduate students. This took the form of extra-curricular supplementary materials, including eBooks, mini-video lectures, three-dimensional virtual reality technologies and online assessments. The evaluation on the proposed learning system revealed that the integration of a virtual environment into educational resources can enhance cognition for students, thereby improving both interaction and experimental safety. Krupnova T. et al. [

9] from South Ural State University created a Virtual Environmental Chemistry Laboratory (VECL) to provide descriptions and simulations of several kinds of experiments, including models for water treatment and toxic gas diffusion experiments. Students after using the VECL asserted that the primary role of the VECL lies in its capacity to enhance operating skills through iterative training without limitation of time and region. In summary, modeling virtual elements shows advantages in engineering education, which requires scenes and operations [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14].

Practice courses are an important component in mechanical engineering education, however giving students real hands-on experience is restricted by the available time, incurs high costs, and has risks. The cost of industrial robots, CNC machines and other engineering machinery is typically high, making it a challenge to provide access for every student. Additionally, the limited class time restricts students' opportunities to gain hands-on experience in operating the machines.

In the case of risks for example, turning and milling operations pose a potential risk of finger or limb loss, while welding and casting operations involve the risk of scalding. Additionally, there are various unforeseen perils such as electric shock, impact injuries and exposure to toxic gases. All these potential risks may pose irreparable harm to novices who are in the initial stages of their mechanical engineering training. Creating a virtual environment, which is closely consistent with the real environment, is an effective way to solve these problems. Students can first operate and program in the virtual environment before transitioning to the real environment, thereby reducing costs and health and safety issues, while enhancing training efficiency. Ivanova G.I. et al. [

15] presented an interactive 3D virtual learning environment (3D VLE) for measuring constructive and geometrical parameters of Gear Hobs in cutting tool courses. Findings from a Likert scale survey, which encompassed five dimensions, revealed that students who utilized the 3D VLE exhibited enhanced proficiency and accuracy in mastering the measurement technique when compared to their counterparts without access to 3D VLE. Peidró A. et al. [

16] presented m-PaRoLa, an interactive web based educational virtual laboratory for operating robots interactively. The primary function of m-PaRoLa is to facilitate students' comprehension of five-bar and 3RRR robots. The distinct advantage lies in the sofware’s compatibility with mobile devices, thus the mobile laboratory. In summary, constructing virtual environments or scenes is a significant way to enhance training in mechanical engineering education. A literature review spanning the past decade finds that specific applications of the virtual scenes include laboratory activities [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21], additive manufacturing [

22], PLC programming [

23], maintenance [

24], assembly [

25], lean manufacturing [

26], casting processes [

27] and welding [

28].

The Ministry of Education in China [

29] introduced “New Engineering” [

30] initiative to facilitate engineering education. Emerging technologies such as virtual reality (VR), digital twins, big data analysis [

31] and AI (Artificial Intelligence) [

32,

33,

34] are introduced. All these efforts aim to foster a digital transformation in engineering education. In China, many universities have established digitized education systems or platforms. For example, Nanjing University of Aeronautics & Astronautics, Tianjin University and Beijing Forestry University developed education systems for aviation [

35], biochemistry [

36] and forestry [

37], which can effectively engage students to train in operations. It is hoped that students' perceptions of traditional industries will shift towards intelligence, digitalization and information. As a consequence enabling them to better align with the evolving industry landscape upon entering future jobs [

38]. An education platform integrating the virtual environment with the real environment/scene is employed for engineering practice in NCUT [

39]. The specific design of the workshop and corresponding application is described in this article.

2. Layout and functions of the Virtual Reality Combined Education Platform

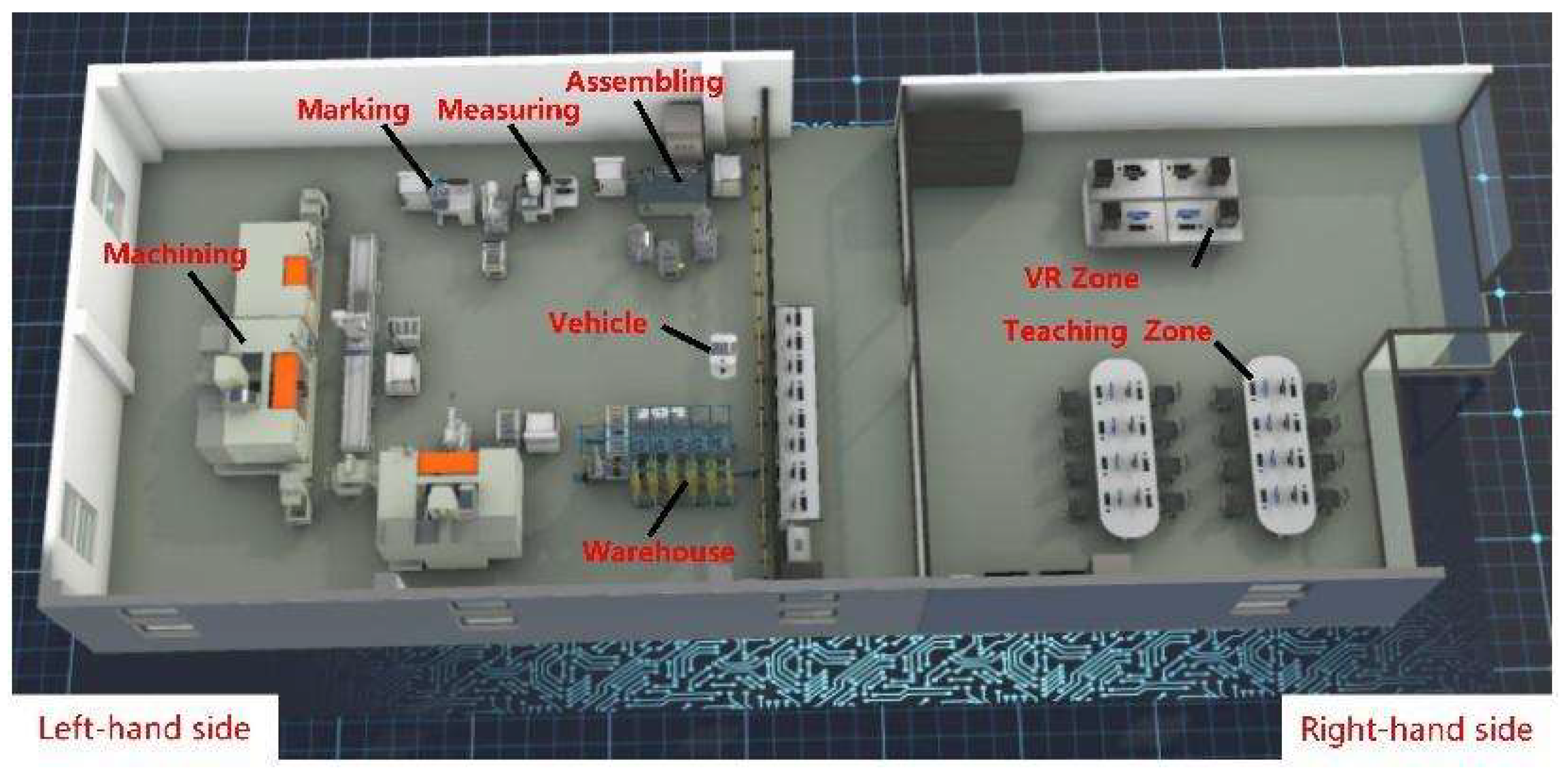

The layout of the platform is illustrated in

Figure 1, and consists of two parts. The left-hand side of

Figure 1 is a production line, including CNC machines, industrial robots and some non-standard equipment. The line is divided into six stations according to their functions, see Sections 2.1.1-2.1.6. The layout is slightly different from a real manufacturing production line in enterprises but is more suitable for mechanical engineering education.

The right-hand side of

Figure 1 is the digital twin of the production line, consisting of two zones, a teaching zone and a VR zone. In the teaching zone the students design the manufacturing process by using CAD to design the components, followed by CAM (computer-aided manufacturing) software to generate the NC (Numerical Control) machining codes. Then, the codes are sent to the manufacturing simulation environment in the VR zone. The students simulate and finalize the manufacturing process in the virtual environment. The final manufacturing process is then executed on the production line, the left-hand side of

Figure 1.

2.1. Production Line Layout

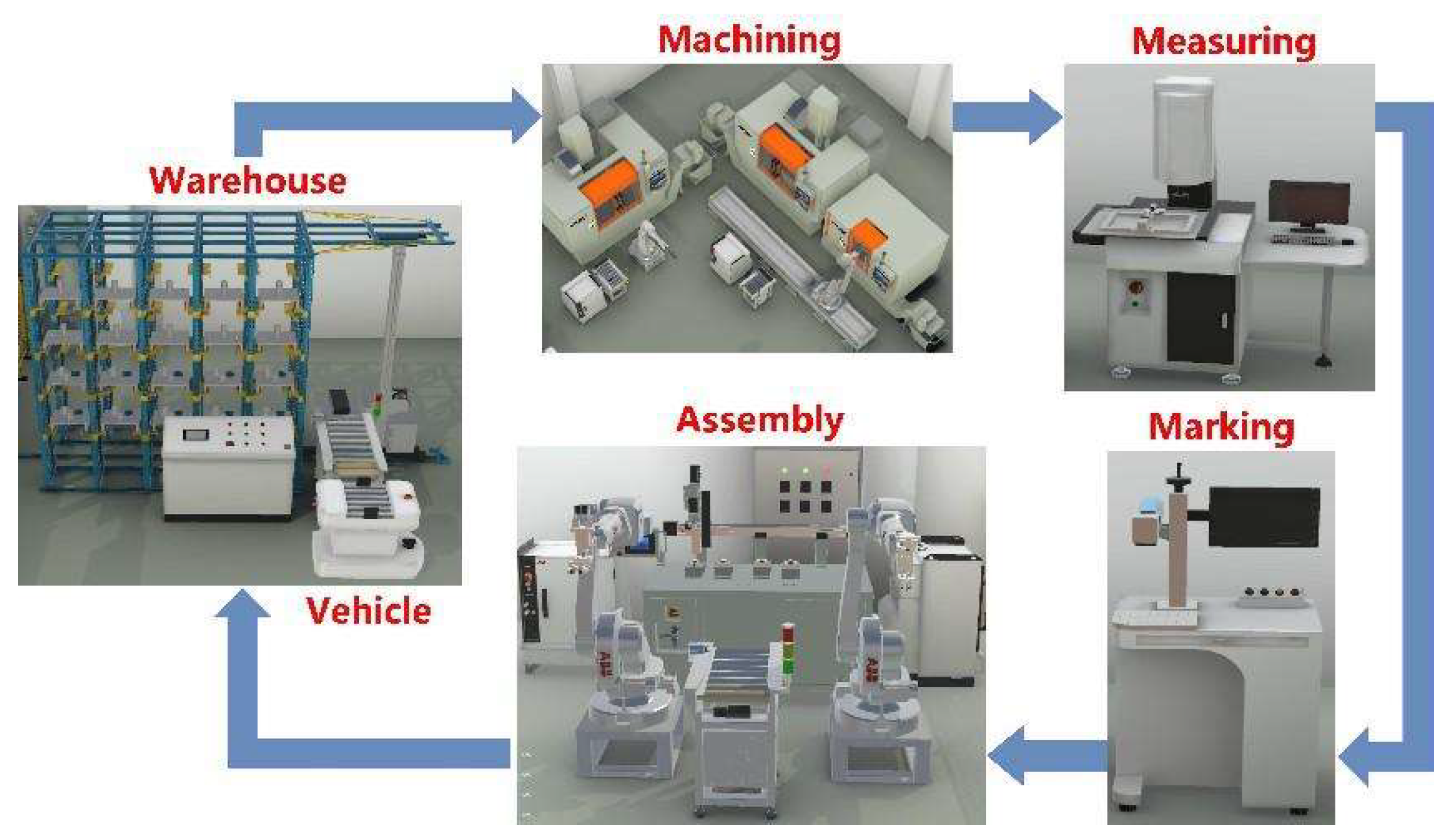

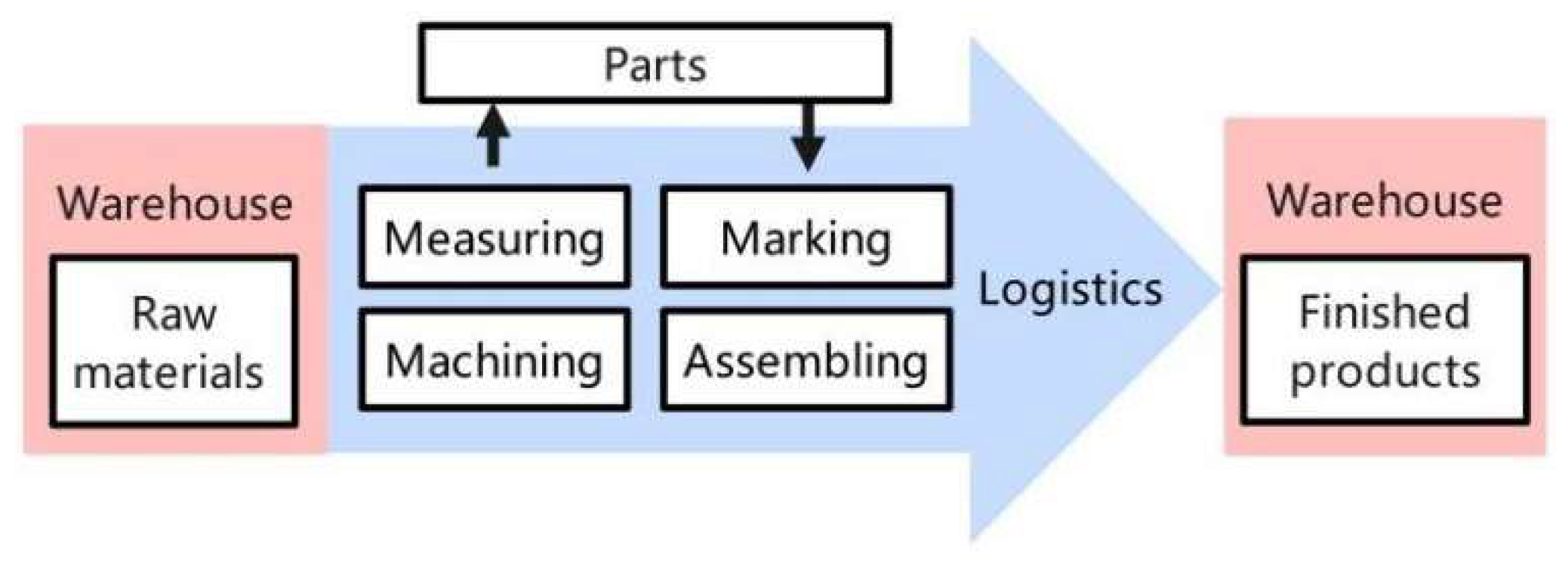

The operation of the production line is shown in

Figure 2. The warehouse serves as the starting point for raw materials delivery and also the end point for finished product storage. Raw materials are processed at four stations into finished products. The stations in order are machining, measuring, marking and assembly. Industrial robots and vehicles are used to transfer the in-production items between each station. Detail description of each station is as follows.

2.1.1. The Warehouse

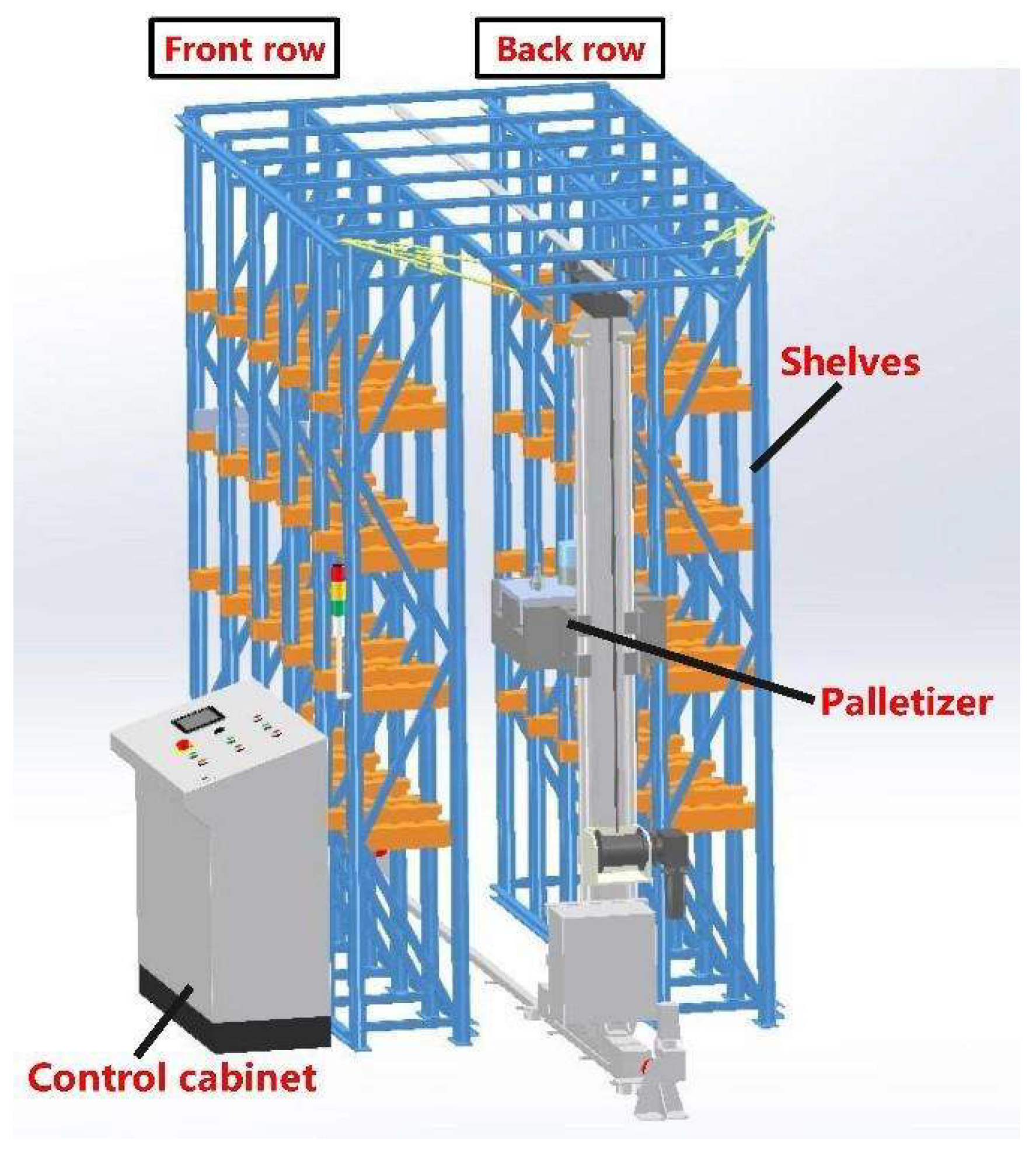

As shown in

Figure 3, the warehouse is equipped with shelves, palletizer and a control cabinet. The shelves are arranged in two rows: the front row holds raw materials purchased from suppliers, while the back row stores the finished products produced by the described production line. The palletizer, located between the two rows, automatically moves items. An S7-1200 series PLC (Programmable Logic Controller) from SIEMENS® is installed in the control cabinet and connected to the server in VR zone via a LAN (Local Area Network) for centralized operation.

2.1.2. The Machining Station

The machining station includes CNC lathes, three-axis CNC milling machines and four-axis CNC milling machines. The controller, provided by FANUC, are connected to the server in the VR zone through a LAN.

2.1.3. The Measuring Station

The measuring station mainly consists of a visual measuring instrument used for geometric measurement. Before the experiment, the teacher sets criterial to determine whether the machined parts meet the required specifications. For example, in the case of a rotary part shown in

Figure 4, the angle of the cone is measured using the instrument. The measurement results serve as key reference for evaluating students’ performance in the experiment.

2.1.4. The Marking Station

The marking station mainly consists of a laser marking machine used to mark two-dimensional codes onto the surface of the components. Usually each code is a unique serial number, required for inspection, tracing and management.

2.1.5. The Assembly Station

At the assembly station the components are assembled to form the final product. It is at this station the product is also packaged. The station contains a ball screw, guide rail, servo motor, air cylinder, proximity sensor and operating screen.

3. Architecture of the Virtual Reality Combined Education Platform

Development of intelligent manufacturing technology begins with the intelligent transformation of individual pieces of equipment. The individual pieces can then be connected using the industrial internet to form an intelligent manufacturing line [

40]. Based on this technical progress, workshops are formed by connecting multiple production lines, and factories are formed by connecting multiple workshops, finally forming an intelligent factory. The connections are made through central nodes at different networks, enabling MES (Manufacturing Execution System) to achieve comprehensive control.

Further developments recently focused on using computer driven simulation to represent a real production line and thus workshop. This virtual representation is known as the digital twin of a production line or workshop. The concept of a digital twin was first proposed by Michael Grieves [

41] of the University of Michigan and developed by companies including SIEMENS® [

42], DASSAULT® [

43] and PTC® [

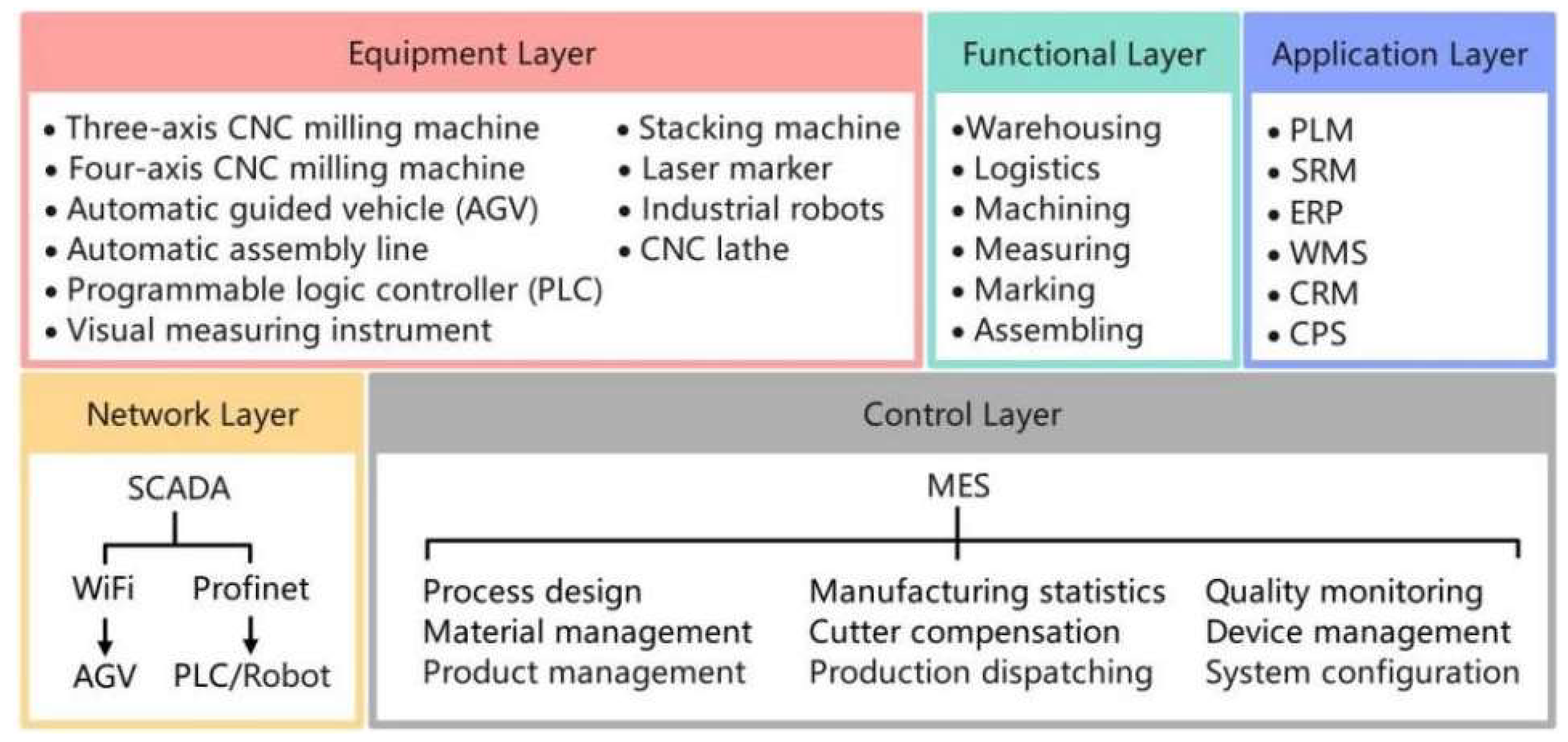

44]. Today, it has evolved into a mature technology. In this paper, digital twin technology is applied to engineering education. First, students design the machining process of a machine part in a virtual environment. Then, the designed parts are produced on the production line. Machining data, such as cutting speed, force and temperature are recorded and displaced in the digital twin, allowing students to observe and analyze the machining process. This virtual reality based approach, integrated with digital twin technology, offers advantages over traditional hands-on operations, as it helps prevent accidents and mistakes. The architecture of the platform, illustrated in

Figure 5, consists of five layers: equipment, functional, application, network, and an control layer. Each of these layers is explained in Sections 3.1-3.5.

3.1. Equipment Layer

The equipment layer contains a range of equipment required to perform manufacturing tasks, including CNC milling machines, an AGV (Automatic Guided Vehicle ), an automatic assembly line, PLCs, a visual measuring instrument, a stacking machine, a laser marker, industrial robots, and a CNC lathe.

As stated before to build a digital twin of a workshop each piece of equipment has to be intelligent and networked. Common equipment utilized for intelligent manufacturing includes CNC machine and industrial robots.

3.1.1. CNC Machine

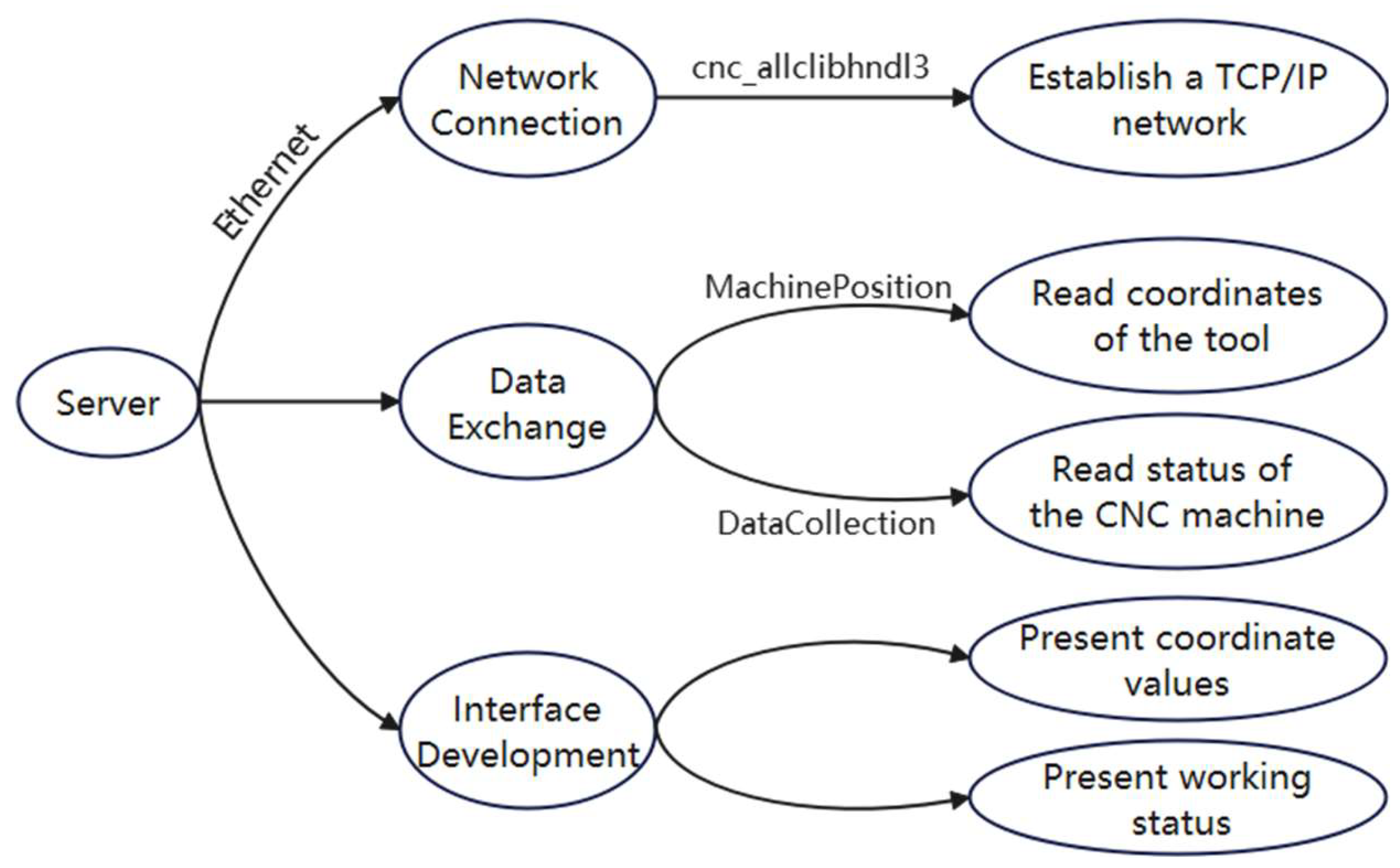

Controller of the CNC machine used in the platform is FANUC Series 0i-TF/MF Plus, which offers a dynamic link library for secondary development. The controller's secondary development includes three aspects: network connection, data exchange and interface development, as shown in

Figure 6. The controller is physically connected to the server via Ethernet cables, and then the

cnc_allclibhndl3 function from the

FWLIB32/64.DLL library is invoked to establish TCP/IP network. The functions within the

DataCollection classes and

MachinePosition classes is invoked to read coordinates of tool and status of the CNC machine. A text box is incorporated on interactive interface to dynamically present coordinate values and working status.

3.1.2. Industrial Robot

Industrial robots are featured with excellent flexibility, high level of automation, exceptional programmability and remarkable versatility, so it is an indispensable component to realize intelligent and automated manufacturing. Generally, the robot is integrated with other equipment or tools to facilitate production, rather than existing independently in the production line [

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50]. The presented education platform in this paper is equipped with five ABB® IRB1600 series industrial robots. They are positioned near the CNC machine, visual measuring instrument, laser marking machine and assembly station to load and unload machined parts. RobotStudio software developed by ABB® is a comprehensive development platform with offline programming, motion simulation, parameter configuration and some essential functionalities to operate the robots. It is installed in the Windows operating systems [

51].

In summary, the equipment suitable for intelligent manufacturing exhibits following characteristics:

Standardized protocol and opening architecture to develop new functions;

On-line monitoring function to collect working status, optimize parameters and compensate errors;

Networking function to establish real-time interaction with other devices.

3.2. Function Layer

Manufacturing enterprises are categorized into two types based on the characteristics of the production process: flow type and discrete type. The flow type enterprises handle materials in uniform and continuous manner, which are common in industries such as metallurgy, chemical engineering, food processing, pharmaceuticals and those replying on chemical reaction for production. In contrast, discrete type enterprise organizes manufacturing through independent methods like cut, grind and drill. These methods are often grouped into distinct regions with factories, workshops, departments and stations. Components and semi-finished products are transferred between these regions and ultimately assembled into finished products. This approach is typical in industries such as vehicle manufacturing, electronics and household appliance. Based on the characteristics of the discrete manufacturing, the equipment on the proposed education platform are categorized according to different functions, thereby summarized as the function layer. Specific functions include storage, logistics, machining, measuring, marking and assembly.

The relationship of each function of the education platform is shown in

Figure 7. The raw materials in the warehouse are processed, forming parts and then assembled into products. Finally, the finished products are sent back to the warehouse. Transfer of parts between each region is facilitated by the logistics function.

3.3. Network Layer

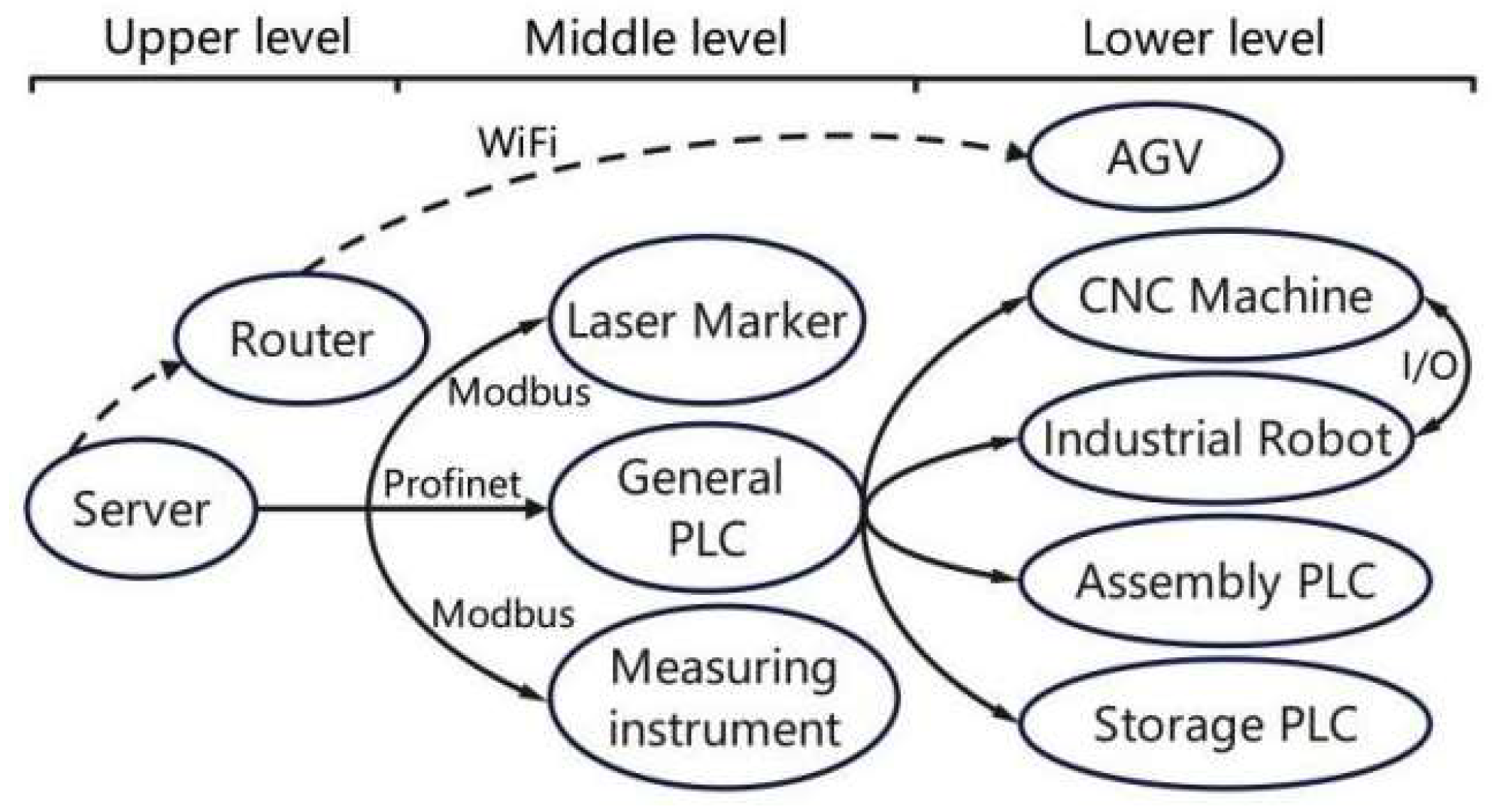

An industrial network connects distributed equipment for process monitoring and control, which is a prerequisite for intelligent manufacturing. The network topology of the education platform is shown in

Figure 8. The network server, located at the upper level, serves as the source node responsible for data collection, data processing and instruction transmission. The equipment at the lower level communicate with each other through wired or wireless communication. For example, the fixed equipment uses Profinet protocol or Modbus protocol to establish wired communication with the server, offering better real-time performance. The Profinet protocol is an industrial network protocol that complies TCP/IP standards, and its physical interface is a standard RJ-45 jack. It is commonly used for process automation, status inspection and motion control [

52]. The AGV, which moves across different equipment, utilizes WiFi (IEEE802.11) protocol to establish a wireless communication with the server. The general PLC in the middle level serves as an instruction dispatcher between the server at the upper level and the equipment at the lower level. The PLC is used for data mapping, processing and transmission. Benefit of using a PLC in the proposed education platform lies in its cache capability, which helps prevent memory overflow.

SCADA (Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition) system running on the server enables centralized management and decentralized control of all equipment. The SCADA system supports a range of protocols and ports to establish both wired and wireless communication, accommodating various communication mediums such as coaxial cable, optical fiber, and microwave. It seamlessly integrates with PLCs, RTU (Remote Terminal Units), micro-controllers and other devices for network connectivity.

3.4. Control Layer

ISA-95 is an international standard developed by ISO (International Standard Organization for Standardization) to standardize the integration of enterprise and control systems [

53]. It is widely adopted in manufacturing enterprises. The processes of transforming raw materials and components into products in manufacturing enterprise involves various activities, including managing raw materials, machinery, information related to planning, scheduling, purchasing and finance. To ensure coordination among stuff, equipment, materials and energy, a control system is required. In this paper, these management activities are categorized under the control layer.

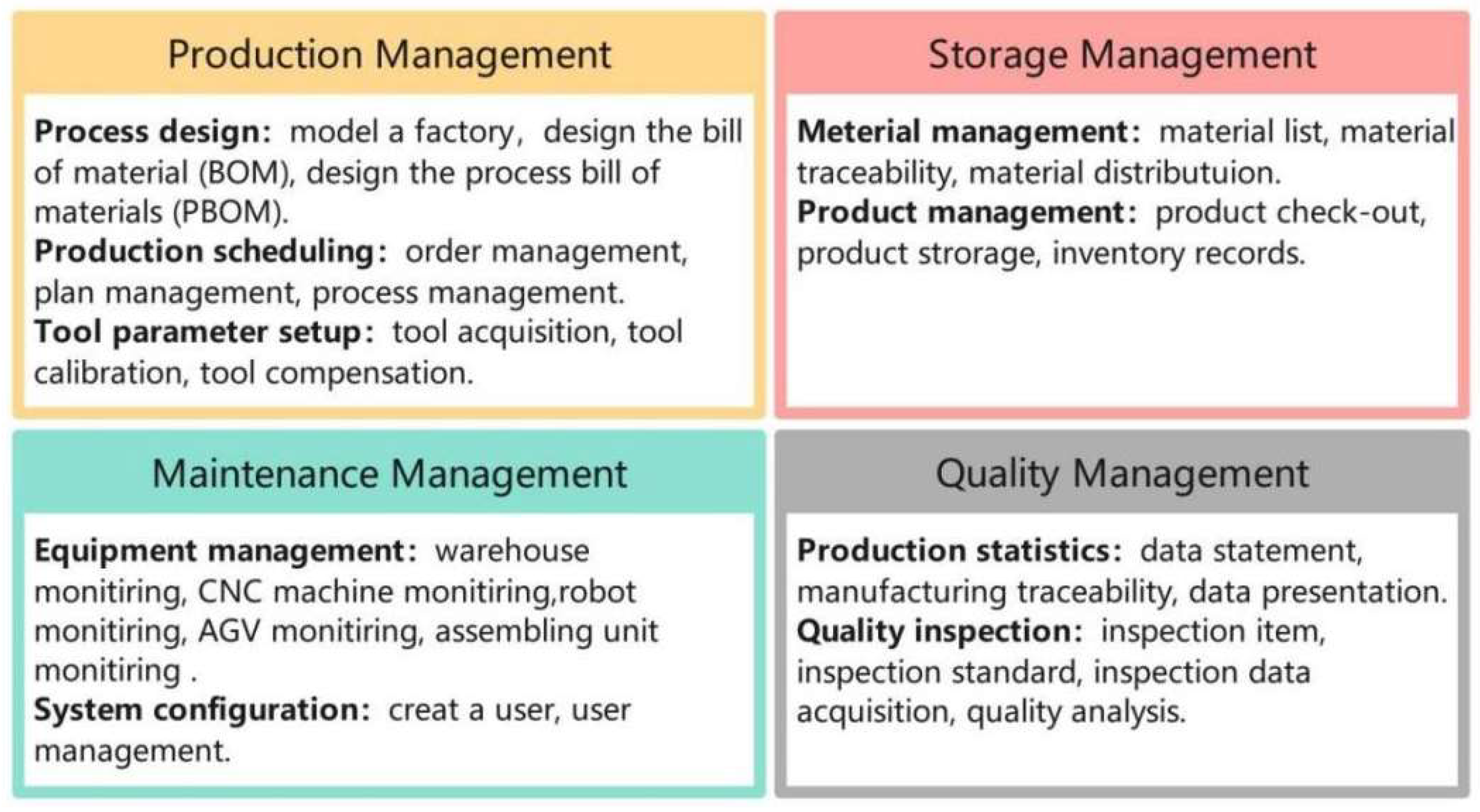

A Manufacturing Execution System (MES), compliant with the ISA-95 standard, is implemented on the server of the proposed education platform. The MES provides various functions, including process design, production scheduling, tool parameter setup, material management, product management, equipment management, system configuration, production statistics and quality inspection. Its architecture adopts B/S (Browser/Server) model, enabling access from any computer within the LAN via a web browser. Following the ISA-95 guidelines for the hierarchy of manufacturing operation management [

54], the MES functions are divided into four groups: production management, storage management, maintenance management and quality management, as illustrated in

Figure 9.

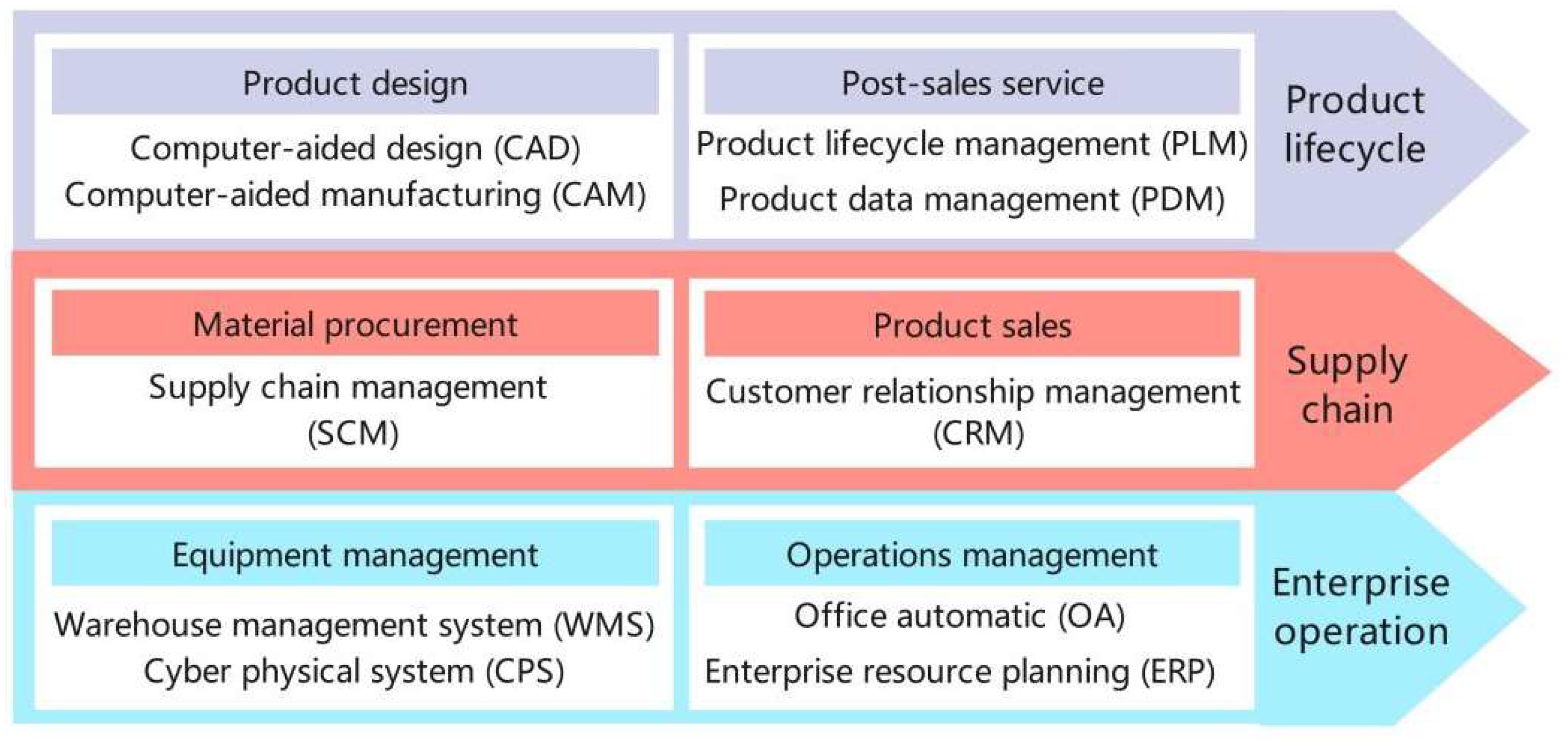

3.5. Application Layer

The presented education platform incorporates various application softwares, including CAD, CAM, PLM, PDM, CRM, SCM, WMS, CPS, OA and ERP. These software are compatible with multiple devices, such as PCs, tablets, mobile phones and cloud platforms, and are classified under the application layer. Their full names are shown in

Figure 10. CAD, CAM, PLM and PDM are used throughout the product life cycle, from product design to post-sales service [

55,

56]. SCM and CRM manage the entire supply chain, covering material procurement to product sales [

57,

58]. WMS, CPS, OA and ERP are employed to improve operational efficiency [59-62]. Integrated seamlessly, these software applications play a crucial role in manufacturing and are included in the education platform to helps students understand the operations of an enterprise.

4. Design of Practice Courses for Students Based on the Education Platform

The proposed education platform has been established at NCUT, with the control system and application software fully integrated. The physical layout of the platform, consistent with the design presented in

Section 2 is shown in

Figure 11 and includes a production line, server, console, VR zone and teaching zone. Modular courses focusing on key technologies in intelligent manufacturing have been designed and implemented. The key innovation of these courses is the integration of virtual reality with hands-on practice. Students learn and design manufacturing process in a virtual environment, and then validate these processes on the actual production line. The course content and practical implementation are detailed, and their effectiveness is evaluated for ongoing improvement.

4.1. Content of the Practice Courses

Students engage in four practice courses based on the platform: structure design, NC code programming, robot operation and manufacturing process design. The software used in these courses includes SolidWorks®, MasterCAM® [

63], RobotStudio® and NX® MCD (Mechatronics Concept Designer) [

64]. The process begins in the teaching zone, where students design 3D model and program NC code. Then they move to the VR zone to observe manufacturing process and record process data via the digital twin. The parts are subsequently manufactured and measured using the instruments shown in

Figure 4.

4.1.1. Structure Design

In the structure design course, design tasks are assigned to students, who then create 3D models of the parts based on the task requirements using SolidWorks. Theses requirements include dimensions, tolerances and material characteristics. After completing the models, students submit engineering drawings that meet the specified criteria. The drawings are then assessed by the teacher after class.

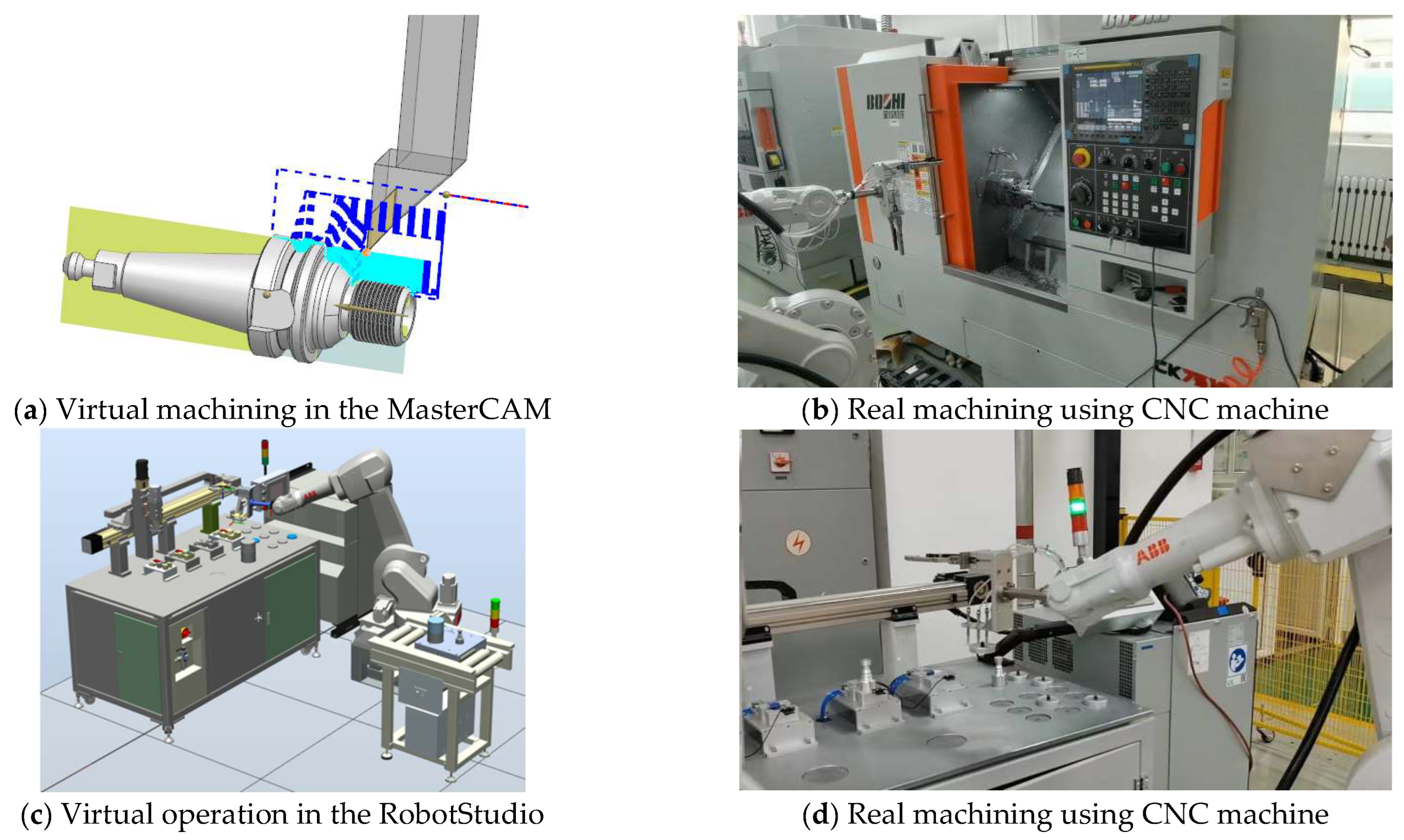

4.1.2. NC Code Programming

In NC code programming course, students import their designed 3D model into MasterCAM software and configure parameters such as speed, feed rate, cutter path and cutter complement for CNC machining. The machining tool path is first simulated in a virtual environment, followed by adjustments before generating the NC code. This code is then uploaded to the production line for manufacturing. The simulation and corresponding real machining process are shown in

Figure 12(a) and

Figure 12(b).

4.1.3. Robot Operation

In robot operation course, students create a virtual model that mirrors the real-world setup using RobotStudio to design movement paths for industrial robots. The movement programs are then generated within RobotStudio and imported into the real industrial robots to move parts onto or off the machine. The robot’s I/O signals are synchronized with the server for monitoring. The virtual model in RobotStudio and the corresponding real-world scenario on the production line is shown in

Figure 12(c) and

Figure 12(d).

4.1.4. Manufacturing Process Design

In manufacturing process design course, students build a virtual production line using the NX® MCD software to simulate the manufacturing process. Specific application of the NX® MCD software is as follows:

Equipment in the production line are arranged according to the layout presented in

Figure 1.

- 4.

Degree of freedoms are added to each equipment, for example six rotations are added to the industrial robot.

- 5.

The logic is programmed to simulate the production process.

The objective of the practice is to develop students' skills in design, operation, and management ability within a manufacturing environment. By the end of the course, students will have designed and manufactured real parts themselves, applying the knowledge gained from all four courses.

4.2. Implementation of the Practice Courses

Taking the rotating part shown in

Figure 12(a) as an example, the students preview layout, functions, equipment, and safety rules of the production line before beginning the courses. The class are divided into four groups, each focusing on a specific task: structure design, NC code programming, robot operation and process design. The structure design group is tasked with designing 3D models and creating engineering drawings of the parts using SolidWorks. The NC code programming group programs tool path in MasterCAM® according to the 3D models and engineering drawings, and then the NC code are generated using the MasterCAM® software. The robot operation group handles programming movement paths. This includes programming path for the AGV to transfer parts between different equipment and programming the industrial robot to load or unload parts from the machinery. The process design group collects the engineering drawings, NC codes and robot movement codes and uploads them into the MES software for production. Additionally, this group is responsible for arranging models and simulating the production process using NX® MCD software. The software and corresponding equipment used by each group are shown in

Table 1.

Each group submits a comprehensive report after practice, including videos, photos, and other supporting materials to demonstrate their achievements. Teachers evaluates students’ performance based on factors such as their attendance, practical execution, comprehensive reports, parts quality and other supporting evidence from the courses.

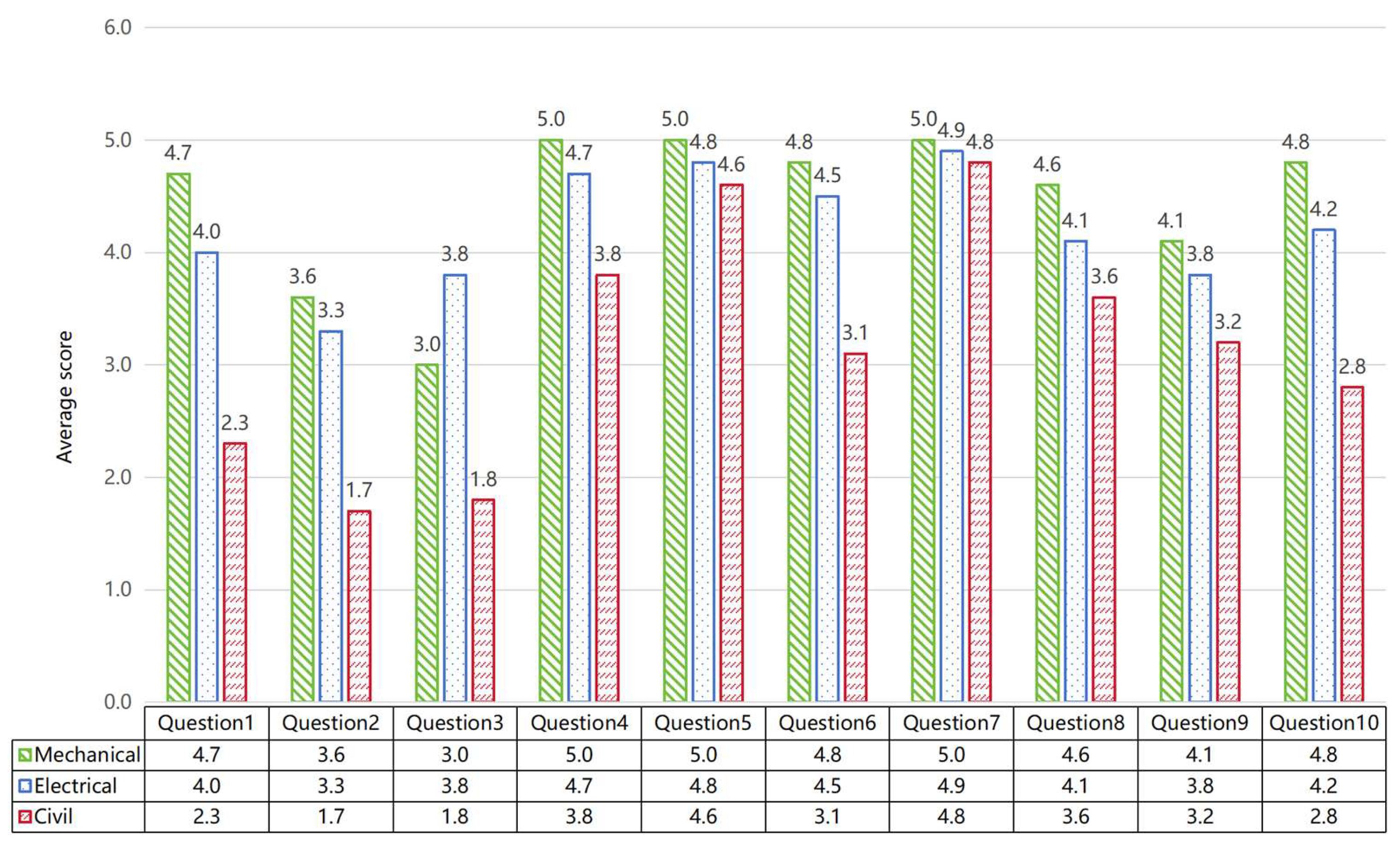

4.3. Assessment of the Practice Courses

To evaluate the usability of the platform and the effectiveness of the practice courses in enhancing students’ engagement and practical skills, a questionnaire was developed to collect student feedback. The assessment uses Likert response scale, a widely used method in psychology for measuring the degree or intensity of the feelings toward specific subjects. This scale consists of a series of statements or opinions, where participants select an option reflecting their level of agreement or attitude. In this assessment, a Likert scale with ten questions was designed, as shown in

Table 2. The questionnaire collects students’ feedback in three key areas: learning outcomes, interaction quality and recommendations. Responses to each question are scored from 1 to 5, with 1 representing “strongly disagree” and 5 representing “strongly agree”. An additional “Not sure” option is included for students who prefer not to respond. For statistical analysis, responses marked as “Not sure” will be excluded.

At the beginning of the courses, students appeared reserved, but over time, they gradually became more proficient with the operations after engaging in hands-on activities. Students from mechanical, electrical and civil engineering disciplines were included in the survey. Questionnaires were distributed after the courses to evaluate the platform’s usability from the students’ perspectives. The statistics are summarized in

Figure 13. It was found that mechanical and electrical students showed a higher level of recognition and appreciation for the platform and courses. Civil engineering students demonstrated less engaged, as reflected in the questionnaire responses. Compared to mechanical students, lots of civil students selected “Not sure” in question 1, 2 and 3. However, the majority still agreed that the courses provided better interactivity than traditional practice based learning.

5. Conclusions

Traditional practice courses such as welding, casting and forging only partially meet the needs of modern enterprises, therefore engineering education platforms needs innovation. Technology related to information, intelligence and digitalization needs to be introduced to enrich the engineering education, so that students studying engineering are educated appropriately for jobs of the future. An education system at NCUT was presented as an example of how to reform the teaching of practice courses, by coupling the virtual to the real environment. A five-layer architecture was proposed to facilitate students’ comprehension of the platform, the layers are equipment composition, process flow, networking technology, management system, and software application. Teachers can also develop a series of training projects from different directions to meet practice and research needs in different disciplines.

Since the establishment of the education platform at NCUT, several training courses have been offered to students studying mechanical engineering. More than 4,000 students have participated in NCUT’s training courses. They were deeply engaged with the course through the combination of virtual and real environments. The students' practical ability, teamworking and organizational leadership improved as a result of the training. In addition, they gained an intuitive understanding of the operations in modern enterprises.

The construction of the education platform at NCUT and the corresponding practice courses is a good example for other training organizations including universities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Hanming Zhang; Funding acquisition, Canzhi Guo; Resources, Xizhi Sun; Writing – original draft, Hanming Zhang; Writing – review & editing, Diane Mynors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Chinese Higher Education Association educational science planning project, grant number 24KC0410; the Beijing educational science planning project, grant number CDDB23202 and the research start-up project in North China University of Technology.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Román-Ibáñez, V.; Pujol-López F.A.; Mora-Mora H.; Pertegal-Felices M.I.; Jimeno-Morenilla A. A Low-Cost Immersive Virtual Reality System for Teaching Robotic Manipulators Programming, Sustainability, 2018, 10(4), 1102. [CrossRef]

- Peña A.M. and Ragan E.D. Contextualizing construction accident reports in virtual environments for safety education. In IEEE Virtual Reality (VR), Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Radianti J.; Majchrzak T.A.; Fromm J.;Wohlgenannt I. A systematic review of immersive virtual reality applications for higher education: Design elements, lessons learned, and research agenda, Computers & Education, 2020, 147, 103778. [CrossRef]

- Liu J.; Liang J.; Zhao S.; Jiang Y.; Wang J.; Jin Y. Design of a Virtual Multi-Interaction Operation System for Hand-Eye Coordination of Grape Harvesting Robots, Agronomy-Basel, 2023, 13(3), 829. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. Z.; Yuan, Y.; Gao, Y.; Tang, S. Q.; Li, Z. G. Virtual Model of Grip-and-Cut Picking for Simulation of Vibration and Falling of Grape Clusters, Transactions of the ASABE, 2019, 62(3), 603-614. [CrossRef]

- Zhou Y.; Ji S.; Xu T.; Wang Z. Promoting knowledge construction: a model for using virtual reality interaction to enhance learning, Procedia computer science, 2018, 130, 239–246. [CrossRef]

- Hai C.P.; Nhu-Ngoc D.; Akeem P.; Quang T.L; Rahat H.; Sungrae C.; Chan S.P. Virtual Field Trip for Mobile Construction Safety Education Using 360-Degree Panoramic Virtual Reality, The international journal of engineering education, 2018, 34(4), 1174–1191.

- Syed Z.A.; Trabookis Z.; Bertrand J.W.; Madathil K.C.; Hartley R.S.; Frady K.K.; Wagner J.R.; Gramopadhye A.K. Evaluation of Virtual Reality Based Learning Materials as a Supplement to the Undergraduate Mechanical Engineering Laboratory Experience, The international journal of engineering education, 2019, 35(3), 842–852.

- Krupnova T.; Rakova O.; Lut A.; Yudina E.; Shefer E.; Bulanova A. Virtual Reality in Environmental Education for Manufacturing Sustainability in Industry 4.0, In Global Smart Industry Conference, Chelyabinsk, Russia, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Gao X.; Zhou P.; Xiao Q.; Peng L.; Zhang M. Research on the Effectiveness of Virtual Reality Technology for Locomotive Crew Driving and Emergency Skills Training, Applied Science-Basel, 2023, 13, 12452. [CrossRef]

- Viitaharju P.; Nieminen M.; Linnera J.; Yliniemi K.; Karttunen A. J. Student experiences from virtual reality-based chemistry laboratory exercises, Education for Chemical Engineers, 2023, 44, 191–199. [CrossRef]

- Azher S.; Cervantes A.; Marchionni C.; Grewal K.; Marchand H.; Harley J.M. Virtual Simulation in Nursing Education: Headset Virtual Reality and Screen-based Virtual Simulation Offer A Comparable Experience, Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 2023, 79, 61–74. [CrossRef]

- Bhagat K.K.; Liou W.K.; Chang C.Y. A cost-effective interactive 3D virtual reality system applied to military live firing training, Virtual Reality, 2016, 20(2), 127–140. [CrossRef]

- Wan Y.; Guo, Z. Improving the Sense of Gain of Graduate Students in Food Science, Journal Of Food Quality, 2021, 2021, 3525667. [CrossRef]

- Ivanova G.I.; Ivanov A. and Radkov M. 3D Virtual Learning and Measuring Environment for Mechanical Engineering Education, In 42nd International Convention on Information and Communication Technology, Electronics and Microelectronics, Opatija, Croatia, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Peidró A.; Tendero C.; Marín J.M.; Gil A.; Payá L.; Reinoso Ó. m-PaRoLa: a Mobile Virtual Laboratory for Studying the Kinematics of Five-bar and 3RRR Planar Parallel Robots, IFAC-PapersOnLine, 2018, 51(4), 178–183. [CrossRef]

- Majid H.; Farahani M.H. and Mert B. A modular virtual reality system for engineering laboratory education, Computer Application in Engineering Education, 2011, 19(2), 305–314. [CrossRef]

- Gu W.; Wen W.; Wu S.; Zheng C.; Lu X.; Chang W.; Xiao P.; Guo X. 3D Reconstruction of Wheat Plants by Integrating Point Cloud Data and Virtual Design Optimization, Agriculture-Basel, 2024, 14(3), 391. [CrossRef]

- Cui L.; Mao H.; Xue X.; Ding S.; Qiao B. Optimized design and test for a pendulum suspension of the crop spray boom in dynamic conditions based on a six DOF motion simulator, International Journal Of Agricultural And Biological Engineering, 2018, 11(3), 76-85. [CrossRef]

- Wang W.; Yang S. Research on the Smart Broad Bean Harvesting System and the Self-Adaptive Control Method Based on CPS Technologies, Agronomy-Basel, 2024, 14(7), 1405. [CrossRef]

- Chen X.; Wang X.; Bai J.; Fang W.; Hong T.; Zang N.; Wang G. Virtual parameter calibration of pod pepper seeds based on discrete element simulation, Heliyon, 2024, 10(11), e31686. [CrossRef]

- Mogessie M.; Wolf S.D.; Barbosa M.; Jones N.; McLaren B.M. Work-in-Progress—A Generalizable Virtual Reality Training and Intelligent Tutor for Additive Manufacturing, In 6th International Conference of the Immersive Learning Research Network, San Luis Obispo, CA, USA, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Kim Y.S.; Lee J.O. and Park C.W. A hybrid learning system proposal for PLC wiring training using AR, In 5th IEEE International Conference on E-Learning in Industrial Electronics, Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Güler O. and Yücedağ I. Developing an CNC lathe augmented reality application for industrial maintanance training, In 2nd international symposium on multidisciplinary studies and innovative technologies, Ankara, Turkey, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Bhatti A.; Khoo Y.B.; Creighton D.; Anticev J.; Nahavandi S.; Zhou M. Haptically enabled interactive virtual reality prototype for general assembly, In World Automation Congress, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 2008.

- Gamlin A.; Breedon P. and Medjdoub B. Immersive Virtual Reality Deployment in a Lean Manufacturing Environment, In International Conference on Interactive Technologies and Games, Nottingham, UK, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Lee J.H.; Choi J.Y.; Kim Y.S. Virtual reality operator training system for continuous casting process in steel industry, In Proceedings of the 2013 winter simulation conference, Pohang, Korea, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Liang X.; Kato H.; Hashimoto N. and Okawa K. Simple Virtual Reality Skill Training System for Manual Arc Welding, Journal of Robotics and Mechatronics, 2014, 26(1), 78–84.

- Ministry of education of the People’s Republic of China, Available online: www.moe.gov.cn, (accessed on 13 November 2023).

- Zheng L.A. and Wei S.Q. Institutionalizing Engineering Education Research (EER) in China under the Context of New Engineering Education: Departments, Programs, and Research Agenda, International Journal of Engineering Education, 2023, 39(2), 353-368.

- Raza A.; Saber K.; Hu Y.; L. Ray R.; Ziya Kaya Y.; Dehghanisanij H.; Kisi O.; Elbeltagi A. Modelling reference evapotranspiration using principal component analysis and machine learning methods under different climatic environments, Irrigation And Drainage, 2023, 72(4), 945-970. [CrossRef]

- Wu Q.; Gu J. Design and Research of Robot Visual Servo System Based on Artificial Intelligence, Agro Food Industry Hi-Tech, 2017, 28(1), 125-128.

- Chen J.; Zhang M.; Xu B.; Sun J.; Mujumdar A. S. Artificial intelligence assisted technologies for controlling the drying of fruits and vegetables using physical fields: A review, Trends In Food Science & Technology, 2020, 105, 251-160. [CrossRef]

- Wang H.; Gu J.; Wang M. A review on the application of computer vision and machine learning in the tea industry, Frontiers In Sustainable Food Systems, 2023, 7, 1172543. [CrossRef]

- Liu H. and Jin X. Digital manufacturing course framework for senior aircraft manufacturing engineering undergraduates, Computer Application in Engineering Education, 2020, 28(2), 338–356. [CrossRef]

- Yu H.Y.; Liu L.P.; Wang C.; Yuan H.; Bai R.F. Construction of intelligent manufacturing practice teaching platform for new engineering, Experimental Technology and Management, 2023, 40(9), 275–279. [CrossRef]

- Li H.Y.; Li N.; Wu J.; Huang C. Design and research of engineering training teaching link for intelligent manufacturing, China Modern Educational Equipment, 2023, 13, 127–129.

- Chryssolouris G.; Mavrikios D.; Papakostas N.; Mourtzis D.; Michalos G.; Georgoulias K. Digital manufacturing: History, perspectives, and outlook, Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part B: Journal of Engineering Manufacture, 2009, 223(5), 451–462. [CrossRef]

- Zhang H.M.; Xu H.H.; Wei L.H.; Jiang F. Exploration of intelligent manufacturing practice teaching mode based on the combination of virtual and reality, Experimental Technology and Management, 2024, 41(5), 203-210. [CrossRef]

- Qiao M. and Meng B. Technical construction of intelligent processing production line for aircraft structural parts, In 5th international conference on green power, materials and manufacturing technology and applications, Taiyuan, China, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Corentin A. and Frédéric V. Towards a Holistic Framework for Digital Twins of Human-Machine Systems, IFAC-PapersOnLine, 2022, 55(29), 67-72. [CrossRef]

- Guerra-Zubiaga D. A.; Bondar A.; Escobedo G.; Schumacher A. Digital Twin In a Manufacturing Integrated System: Siemens TIA and PLM Case Study, In ASME international mechanical engineering congress and exposition, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Gabet L.; Golden D.; Vernon N.; Gille F.; Fechner B. 3D Digital Twin of the Earth from Satellite Imagery & Quantitative Simulation, In International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Stojadinovic S. M.; Zivanovic S.; Slavkovic N.; Durakbasa N. M. Digital measurement twin for CMM inspection based on step-NC, International Journal of Computer Integrated Manufacturing, 2021, 34(12), 1327-1347. [CrossRef]

- Chen D. Application of industrial robots in stamping automation production line, International Conference on Algorithms, In High Performance Computing, and Artificial Intelligence, Sanya, China, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Hao X.D.; Bian Y.; Bai L.; Li H.; Sun C. J. The Research and Application of Industrial Robot in Steel Deep Processing Field, In 5th Annual International Conference on Material Engineering and Application, Wuhan, China, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Ding C.L. and Jin L. The research of key technologies and simulation of industrial robot welding production line, In 2nd International Conference on Advanced Robotics and Mechatronics, Hefei and Tai'an, China, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Jin Y.; Liu J.; Xu Z.; Yuan S.; Li P.; Wang J. Development status and trend of agricultural robot technology, International Journal Of Agricultural And Biological Engineering, 2021, 14(4), 1-19. [CrossRef]

- Han L.; Mao H.; Kumi F.; Hu J. Development of a Multi-Task Robotic Transplanting Workcell for Greenhouse Seedlings, Applied Engineering in Agriculture, 2018, 34(2), 335-342. [CrossRef]

- Ji W.; Zhang T.; Xu B.; He G. Apple recognition and picking sequence planning for harvesting robot in a complex environment, Journal of Agricultural Engineering, 2024, 55(1), 1549. [CrossRef]

- Connolly C. Technology and applications of ABB RobotStudio, Industrial Robot, 2009, 36(6), 540–545. [CrossRef]

- Yang M. and Li G. Analysis of PROFINET IO Communication Protocol. In Fourth International Conference on Instrumentation and Measurement, Computer, Communication and Control, Harbin, China, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Mazak A. and Huemer C. From Business Functions to Control Functions: Transforming REA to ISA-95, In 17th Conference on Business Informatics, Lisbon, Portugal, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Yue L.; Niu P.; Wang Y. Guidelines for defining user requirement specifications (URS) of manufacturing execution system (MES) based on ISA-95 standard, In International Conference on Computer Information Science and Application Technology, Daqing, China, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Ming X.G.; Yan J.Q.; Wang X.H.; Li S.N.; Lu W.F.; Peng Q.J.; Ma Y.S. Collaborative process planning and manufacturing in product lifecycle management, Computers in Industry, 2008, 59(2–3), 154–166. [CrossRef]

- Xu X.W. and Liu D.T. A web-enabled PDM system in a collaborative design environment, Robotics and Computer-Integrated Manufacturing, 2003, 19(4), 315–328. [CrossRef]

- Kache F. and Seuring S. Challenges and opportunities of digital information at the intersection of Big Data Analytics and supply chain management, International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 2017, 37(1), 10–36. [CrossRef]

- Oscar G.B.; Venturini W.T. and Javier G.B. CRM Technology: Implementation Project and Consulting Services as Determinants of Success, International Journal of Information Technology & Decision Making, 2017, 16(2), 421–441. [CrossRef]

- Mao J.; Xing H.H.; Zhang X.Z. Design of Intelligent Warehouse Management System, Wireless Personal Communications, 2018, 102(2), 1355–1367.

- Yu Z.; Jie O.; Li S. and Peng X. Formal modeling and control of cyber-physical manufacturing systems, Advances in Mechanical Engineering, 2017, 9(10), 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Wu S.L.; Xu L. and He W. Industry-oriented enterprise resource planning, Enterprise Information Systems, 2009, 3(4), 409–424. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y.; Chen L.; Battino M.; Farag M.A.; Xiao J.; Simal-Gandara J.; Gao, H.; Jiang, W. Blockchain: An emerging novel technology to upgrade the current fresh fruit supply chain, Trends In Food Science & Technology, 2022, 124, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Munro D. Development of an automated manufacturing course with lab for undergraduates, In 2013 IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE), Oklahoma, USA, 2013.

- Zhang L.; Cai Z. Q.; Ghee L. J. Virtual Commissioning and Machine Learning of a Reconfigurable Assembly System, In 2020 2nd International Conference on Industrial Artificial Intelligence (IAI), Shenyang, China, 2020. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).