Submitted:

03 February 2025

Posted:

19 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Sunflower Husk Ashes Composition

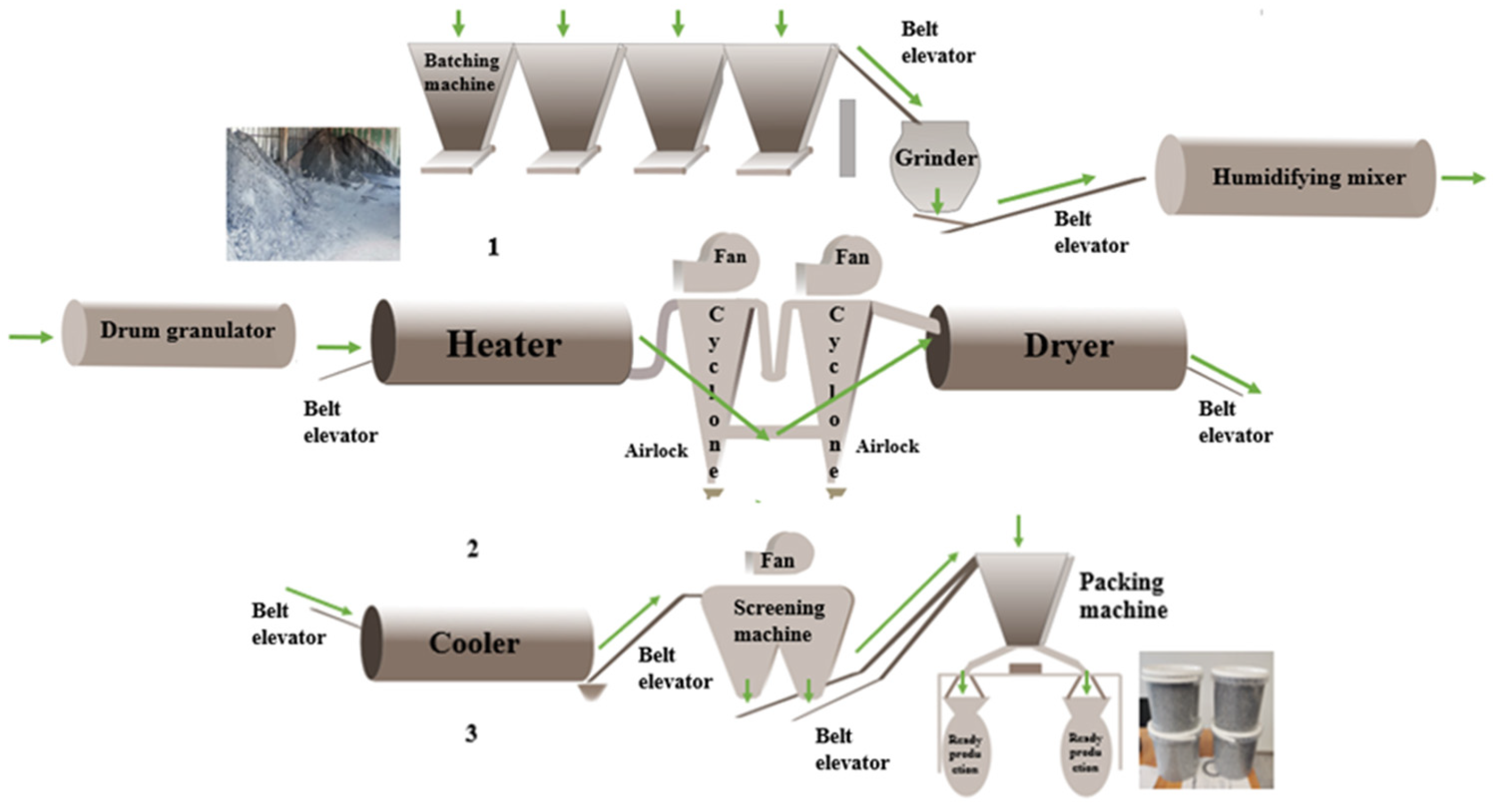

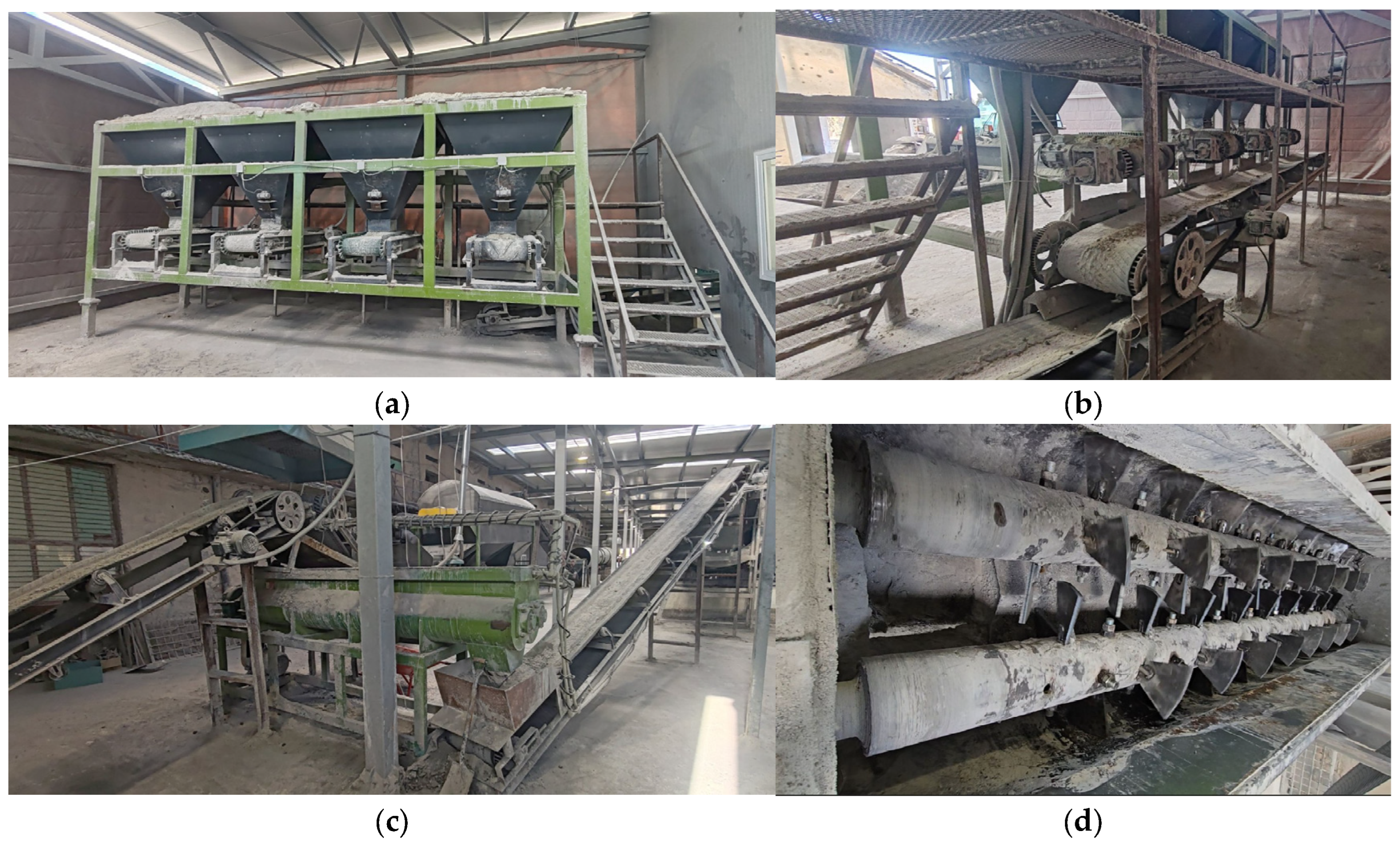

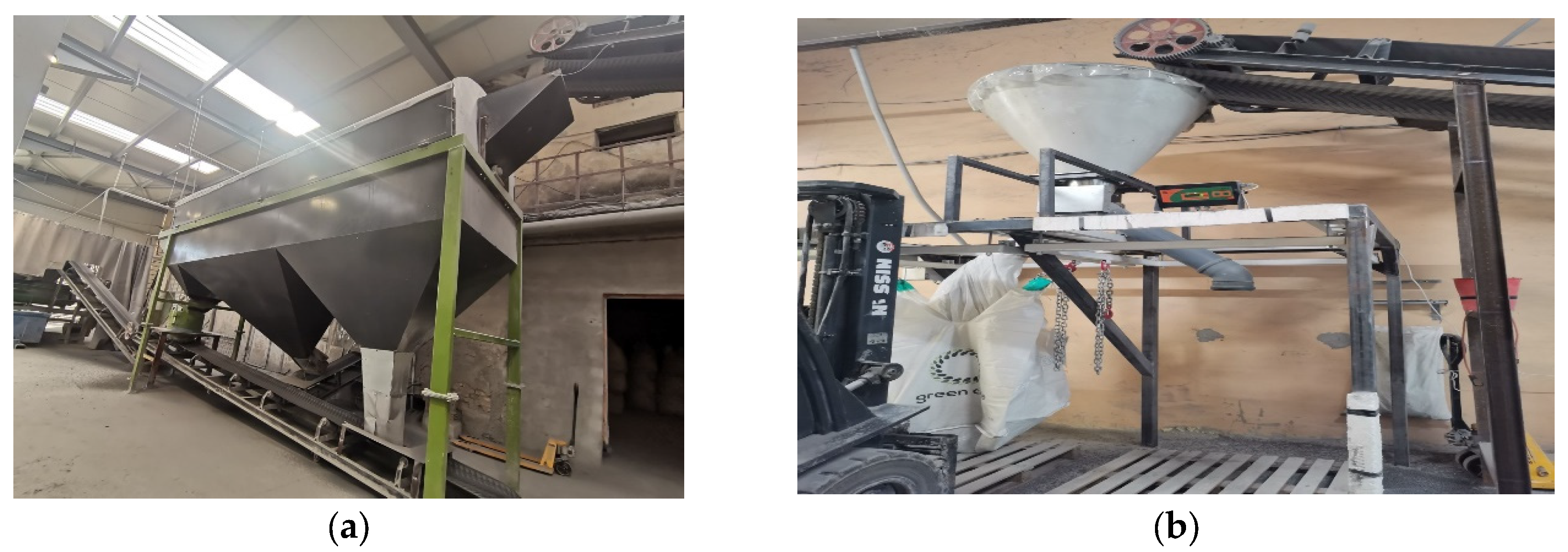

3.2. Commissioning of Full-Scale Technology and Adjustment of Process Parameters

|

Win wt. % |

5–8 | 9–12 | 13–15 |

|

Gtw l/min |

18 | 8 | 2 |

| Experiment | SHA sample |

tin °C |

τ min |

Wgran wt.% | Crushing test | К2О wt. % |

P2O5 wt. % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exp. 1 | SHA1-F | 80 | 20 | > 5 | passed | 23.3 | 4.3 |

| Exp. 2 | SHA2-F | 100 | 20 | > 5 | passed | 18.9 | 5.6 |

| Exp. 3 | SHA7-F | 100 | 20 | > 5 | passed | 27.0 | 6.9 |

| Exp. 4 | SHA7-F | 100 | 40 | > 5 | passed | 22.3 | 5.1 |

| Exp. 5 | SHA7-S | 180 | 20 | 5 | passed | 28.7 | 5.4 |

| Exp. 6 | SHA7-F | 220 | 20 | 5 | passed | 29.8 | 5.0 |

| Exp. 7 | SHA1-F | 320 | 20 | < 3 | failed | 26.5 | 5.2 |

3.3. Mixing of Sunflower Husk Ashes by Different Sources for Granulation

3.4. Analyzing of Applicability of Sunflower Husk Ashes Granules as Bio-Fertilizer

4. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Food and Agriculture Organization. Available online: https://www.fao.org/about/about-fao/en/ (accessed on day month year).

- Hale, A.; Köker, A.R. Analyzing and mapping agricultural waste recycling research:An integrative review for conceptual framework and future directions. Resources Policy 2023, 85, 103987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finore, I.; Romano, I.; Leone, L.; Di Donato, P.; Nicolaus, B.; Poli, A.; Lama, L. Biomass Valorization: Sustainable Methods for the Production of Hemicellulolytic Catalysts from Thermoanaerobacterium thermostercoris strain BUFF. Resources 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Agriculture and Food. Available online: https://www.mzh.government.bg/en/ (accessed on day month year).

- Ng, H. S.; Kee, P. E.; Yim, H. S.; Chen, P.; Wei, H.; Lan, J. W. Recent advances on the sustainable approaches for conversion and reutilization of food wastes to valuable bioproducts. Bioresource Technology 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liua, H.; Jianga, G.M.; Zhuang, H.Y.; Wang, K.J. Distribution, utilization structure and potential of biomass resources in rural China: With special references of crop residues. Elsevier 2008, 1402–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez, A.; Garrido-Chamorro, S.; Vasco-Cárdenas, M.F.; Barreiro, C. From Lab to Field: Biofertilizers inthe 21st Century. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chojnacka, K.; Moustakas, K.; Witek-Krowiak, A. Bio-based fertilizers: A practical approach towards circular economy. Bioresource Technology 2020, 295, 122223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimi, A.; Roopnarain, A.; Adeleke, R. Biofertilizer production in Africa: Current status, factors impeding adoption and strategies for success. Scientific African 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunus, M.U.; Silas, K.; Yaum, A.L.; Kwaji, B.H. A Review of Biofertilizer Production: Bioreactor, Feedstocks and Kinetics. SSRG International Journal of Recent Engineering Science 2022, 9, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pociene, O.; Šlinkšiene, R. Properties and Production Assumptions of Organic Biofertilisers Based on Solid and Liquid Waste from the Food Industry. Appl. Sci. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przygocka-Cyna, K.; Barłóg, P.; Spizewski, T.; Grzebisz, W. Bio-Fertilizers Based on Digestate and Biomass Ash as an Alternative to Commercial Fertilizers—The Case of Tomato. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nramat, W.; Traiphat, W.; Sukruan, P.; Utaprom, P.; Namgaew, S.; Sodajaroen, S.; Chatpuk, R.; Phetduang, L. Development of a Bio-Fertilizer Machine (Holmon Egg) Integrated with NPK Sensor Technology for Enhancing Organic Vegetable Production in Sufficiency Community Enterprises. International Journal of Geoinformatics 2024, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czekała, W.; Jeżowska, A.; Chełkowski, D. The Use of Biochar for the Production of Organic. Journal of Ecological Engineering 2019, 20, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaikh, M.S.; Patil, M. Production and utilization strategies of organic fertilizers for organic farming: an eco-friendly approach. International Jurnal of Life scince & Pharma Research 2013, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Bharti, N.; Suryavansh, M. Chapter 10—Quality control and regulations of biofertilizers: Current scenario and future prospects. Biofertilizers 2021, 1, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, D.U. Surajudeen Abdulsalam 2. Assessement of Bio-fertilizer Quality of Anaerobic Digestion of Watermelon Peels and Cow Dung. Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering 2017, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehata, M.M.; El-Khawas, S.S. Effect of Two Biofertilizers on Growth Parameters, Yield Characters, Nitrogenous Components, Nucleic Acids Content, Minerals, Oil Content, Protein Profiles and DNA Banding Pattern of Sunflower (Helianthus annus L. cv. Vedock) Yield. Pakistan Jurnal of Biological Sciences 2003, 6, 1257–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paleckienė, R.; Sviklas, A.M.; Šlinkšienė, R.; Virginijus Štreimikis. Complex Fertilizers Produced.

- from the Sunflower Husk Ash. Polish J. of Environ. Stud. 2010, 19, 973–979.

- Akca, M.O.; Bozkurt, P.A.; Gokmen, F.; Akca, H.; Yagcıogluq, K.D.; Uygur, V. Engineering the biochar surfaces through feedstock variations and pyrolysis temperatures. Industrial Crops & Products 2024, 118819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somba, B.E.; Napitupulu, M.; Walanda, D.K.; Anshary, A.; Talo, W.S. Optimizing the Performance of Sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) Seed Shell-Derived Biochar for Lead Ion Adsorption. International Journal of Design & Nature and Ecodynamics 2024, 19, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Zhang, C.; Liu, R.; Li, S.; Wang, M. Sunflower straw ash as an alternative activator in alkali-activated grouts: A new 100% waste-based material. Ceramics International 2023, 49, 32308–32312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahunsi, S.O.; Ogunwole, O.J. Biofertilizer production systems: Industrial insights. Biofertilizers 2021, 1, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanowska-Duda, Z.; Janas, R.; Grzesik, M. Increasing Fertilization Efficiency of Biomass Ash by the Synergistically Acting Digestate and Extract fromWater Plants Sequestering CO2 in Sorghum Crops. Molecules 2024, 4397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rushan, G.; Sotnikov, V. Characteristics of granulated activated carbon from a mixture of plant raw material waste. Bulletin of the Tomsk Polytechnic University. Geo Аssets Engineering 2024, 335, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirparsa, T.; Ganjali, H.R.; Dahmardeh, M. The Effect of Bio Fertilizers on Yield and Yield Components of Sunflower Oil Seed and Nut. International Journal of Agriculture and Biosciences 2016, 5, 46–49. [Google Scholar]

- Yelatontsev, D.; Mukhachev, A. Utilizing of sunflower ash in the wet conversion of phosphogypsum—a comparative study. Environmental Challenges 2021, 5, 100241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Șerbănoiu, A.A.; Gradinaru, C.M.; Cimpoesu, N.; Filipeanu, D.; Serbanoiu, B.V.; Chereches, C.C. Study of an Ecological Cement-Based Composite with a Sustainable Raw Material, Sunflower Stalk Ash. Materials 2021, 14, 7177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondarenko, A.M.; Lipkovich, E.I.; Kachanova, L.S. Control of Technological Processes of Organic Fertilizers Application as a Tool to Ensure Food Safety. Journal of Environmental Management and Tourism 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Mohanty, S.; Sahu, G.; Rana, M.; Pilli, K. Biochar: A Sustainable Approach for Improving Soil Health and Environment, Soil Erosion—Current Challenges and Future Perspectives in a Changing World. IntechOpen 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninkov, J.; Jakšić, S.; Nenin, P.; Gvozdenović, M.; Mijić, B.; Radović, B.; Milić, S. Waste ashes from burned sunflower hulls as new fertilising materials. Environmental Engineering 2023. [CrossRef]

- El-Kader, A.A.ABD.; Mohamedin, A.A.M.; Ahmed, M.K.A. Growth and Yield of Sunflower as Affected by Different Salt Affected Soils. Int. J. Agri. Biol. 2006, 8, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Turzynski, T.; Kluska, J.; Ochnio, M.; Kardas, D. Comparative Analysis of Pelletized and Unpelletized Sunflower Husks Combustion Process in a Batch-Type Reactor. Materials 2021, 14, 2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kundu, A.K.; Reddy, S.S.; Kaur, G.; Chhabra, V. Effect of sulphur fertilization on growth and yield of sunflower crop-a review. Indian Journal of Agriculture and Allied Sciences 2022, 8, 3. [Google Scholar]

| Sample ID | Region of supplier | Sampling zone |

|---|---|---|

| SHA1-F | Northeastern Bulgaria | Filter |

| SHA1-S | Central northern Bulgaria | Storage place |

| SHA2-F | Central northern Bulgaria | Filter |

| SHA2-S | Central northern Bulgaria | Storage place |

| SHA3-S | Northern Bulgaria | Storage place |

| SHA4-F | Northeastern Bulgaria | Filter |

| SHA4-B | Northeastern Bulgaria | Bottom ash |

| SHA4-S | Northeastern Bulgaria | Storage place |

| SHA5-F | Southeastern Bulgaria | Filter |

| SHA5-B | Southeastern Bulgaria | Bottom ash |

| SHA6-S | Southern Bulgaria | Storage place |

| SHA7-F | Central northern Bulgaria | Filter |

| SHA7-S | Central northern Bulgaria | Storage place |

| SHA8-S | Northeastern Bulgaria | Storage place |

| SHA9-S | Northeastern Bulgaria | Storage place |

| SHA10-S | Northeastern Bulgaria | Storage place |

| SHA11-S | Central northern Bulgaria | Storage place |

| SHA12-S | Northeastern Bulgaria | Storage place |

| SHA13-S | Southern Romania 1 | Storage place |

| SHA14-S | Southern Romania 2 | Storage place |

| SHA15-S | Southern Romania 3 | Storage place |

| SHA16-S | Southern Romania 4 | Storage place |

| Sample | К2О wt. % |

P2O5 wt. % |

Fe2O3 wt. % |

MgO wt. % |

SO3 wt. % |

CaO wt. % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHA1-F | 40.9 | 4.5 | 0.0 | 7.3 | 7.2 | 14.8 |

| SHA1-S | 30.7 | 4.0 | 0.3 | 9.3 | 7.4 | 22.5 |

| SHA2-F | 17.9 | 9.2 | 0.6 | 15.3 | 4.1 | 29.0 |

| SHA2-S | 24.6 | 6.6 | 0.3 | 13.8 | 7.1 | 22.7 |

| SHA3-S | 22.5 | 10.5 | 0.2 | 14.9 | 3.8 | 24.4 |

| SHA4-F | 39.4 | 1.5 | 0.0 | 14.1 | 3.7 | 17.8 |

| SHA4-B | 12.0 | 7.4 | 1.9 | 15.1 | 3.7 | 33.8 |

| SHA4-S | 30.8 | 3.8 | 0.3 | 9.3 | 7.4 | 22.5 |

| SHA5-F | 40.0 | 1.4 | 0.1 | 11.2 | 6.5 | 16.9 |

| SHA5-B | 23.2 | 6.3 | 0.3 | 13.9 | 3.6 | 24.5 |

| SHA6-S | 18.9 | 6.5 | 0.9 | 15.5 | 4.0 | 25.7 |

| SHA7-F | 32.7 | 7.8 | 0.3 | 12.3 | 4.4 | 19.9 |

| SHA7-S | 32.5 | 5.2 | 0.4 | 12.5 | 4.5 | 21.1 |

| SHA8-S | 22.9 | 6.3 | 0.4 | 14.7 | 3.1 | 29.0 |

| SHA9-S | 20.3 | 9.5 | 0.4 | 16.1 | 7.2 | 18.3 |

| SHA10-S | 22.8 | 3.9 | 0.4 | 16.0 | 6.9 | 22.4 |

| SHA11-S | 23.5 | 6.9 | 0.6 | 15.4 | 3.4 | 28.9 |

| SHA12-S | 20.3 | 9.0 | 0.5 | 14.8 | 4.1 | 27.9 |

| SHA13-S | 33.0 | 5.9 | 0.4 | 11.7 | 4.3 | 21.7 |

| SHA14-S | 30.9 | 6.3 | 0.3 | 11.7 | 6.1 | 22.3 |

| SHA15-S | 44.0 | 3.8 | 0.0 | 7.3 | 15.8 | 11.7 |

| SHA16-S | 26.9 | 8.9 | 0.3 | 13.7 | 5.7 | 24.1 |

| Experiment | Samples in mixture |

Volumetric ratio |

К2О wt. % |

P2O5 wt. % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exp. 8 | SHA1-F and SHA7-F | 50/50 | 30.8 | 4.9 |

| Exp. 9 | SHA1-S and SHA2-S | 50/50 | 29.5 | 5.8 |

| Exp. 10 | SHA7-S and SHA2-S | 70/30 | 30.0 | 4.7 |

| Exp. 11 | SHA4-F, SHA4-B and SHA2-S | 0.26/0.24/0.5 | 31. 0 | 6.6 |

| Exp. 12 | SHA4-F, SHA4-B and SHA2-S | 0.36/0.34/0.3 | 33.6 | 4.8 |

| Exp. 13 | SHA5-F, SHA5-B and SHA2-S | 0.43/0.37/0.2 | 25.8 | 5.2 |

| Chemical element |

Result mg/kg |

Chemical element |

Result mg/kg |

|---|---|---|---|

| Boron | 620 | Sulfur | 29992 |

| Vanadium | 2.2 | Thallium | < 0.050 |

| Iron | 749 | Phosphorus | 21564 |

| Potassium | 355573 | Chromium | 43.5 |

| Calcium | 137394 | Zinc | 164 |

| Magnesium | 71023 | Arsenic | < 0.050 |

| Manganese | 203 | Cadmium | 1.37 |

| Copper | 263 | Mercury | < 0.050 |

| Nickel | 23.5 | Lead | 1.20 |

| PAH concentration, μg/kg | PAH concentration, μg/kg | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANA | Acenaphthene | < 10.0 | CHR | Chrysene | < 10.0 |

| ANY | Acenaphthylene | < 10.0 | DBA | Dibenzo(a,h)anthracene | 41.5 |

| ANT | Anthracene | < 10.0 | FA | Fluoranthene | < 10.0 |

| BaA | Benzo(a)anthracene | < 10.0 | FLU | Fluorene | < 10.0 |

| BaP | Benzo(a)pyrene | < 10.0 | IPY | Indeno(1,2,3-cd)pyrene | < 10.0 |

| BbF | Benzo(b)fluoranthene | < 10.0 | NAP | Naphthalene | 15.7 |

| BPE | Benzo(g,h,i)perylene | < 10.0 | PHE | Phenanthrene | < 10.0 |

| BkF | Benzo(k)fluoranthene | < 10.0 | PYR | Pyrene | < 10.0 |

| Non-dioxin-like PCBs μg/kg |

Mono-ortho PCBs ng/kg |

Non-ortho PCBs ng/kg |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCB 28 | < 0.10 | PCB 123 | < 0.66 | PCB 81 | < 0,73 |

| PCB 52 | < 0.10 | PCB 118 | 15.95 | PCB 77 | < 0,72 |

| PCB 101 | < 0.10 | PCB 114 | < 0.65 | PCB 126 | < 0,98 |

| PCB 138 | < 0.10 | PCB 105 | 5.51 | PCB 169 | < 1,39 |

| PCB 153 | < 0.10 | PCB 167 | 7.02 | ||

| PCB 180 | < 0.10 | PCB 156 | 3.98 | ||

| PCB 157 | < 0.96 | ||||

| PCB 189 | < 1.08 | ||||

| Polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxin ng/kg | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2.3.7.8-TCDF | < 0.100 | 1.2.3.4.7.8-HxCDD | < 0.149 |

| 2.3.7.8-TCDD | < 0.061 | 1.2.3.6.7.8-HxCDD | < 0.125 |

| 1.2.3.7.8-PeCDF | < 0.073 | 1.2.3.7.8.9-HxCDD | < 0.131 |

| 2.3.4.7.8-PeCDF | < 0.070 | 1.2.3.4.6.7.8-HpCDF | < 0.061 |

| 1.2.3.7.8-PeCDD | < 0.148 | 1.2.3.4.7.8.9-HpCDF | < 0.092 |

| 1.2.3.4.7.8-HxCDF | < 0.133 | 1.2.3.4.6.7.8-HpCDD | < 0.087 |

| 1.2.3.6.7.8-HxCDF | < 0.137 | OCDF | < 0.590 |

| 2.3.4.6.7.8-HxCDF | < 0.142 | OCDD | < 0.167 |

| 1.2.3.7.8.9-HxCDF | < 0.232 | 1.2.3.4.7.8-HxCDD | < 0.149 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).