Submitted:

19 February 2025

Posted:

20 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

3. Results

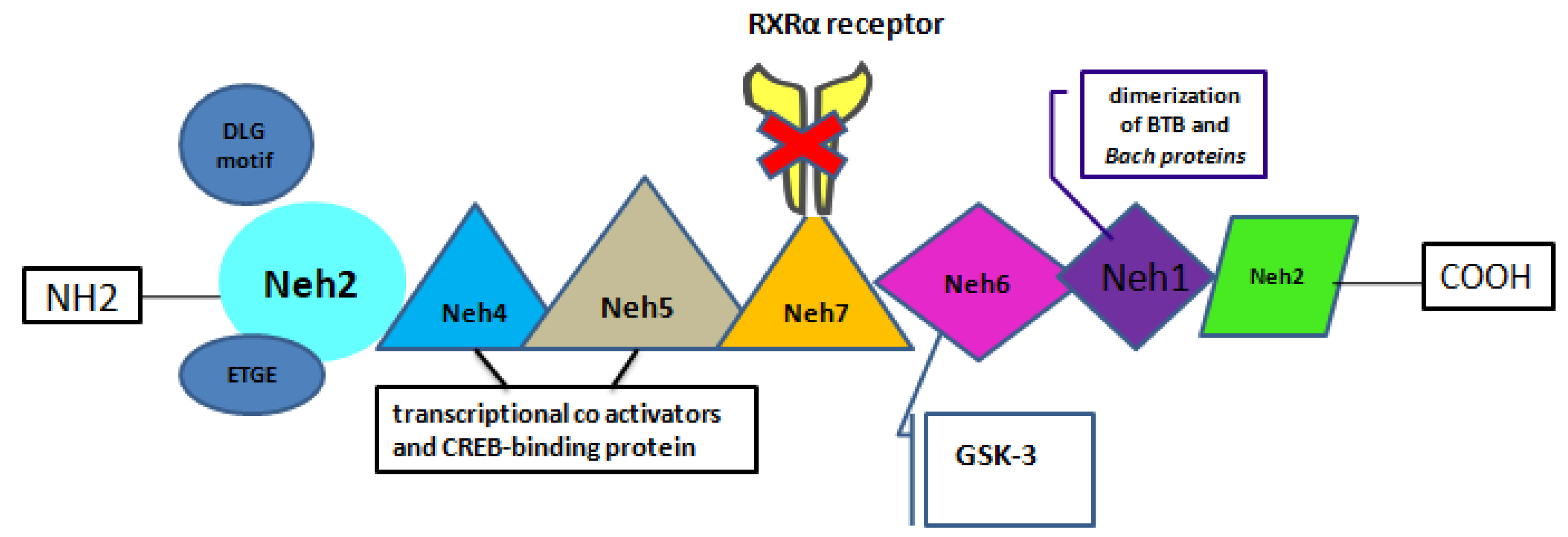

3.1. Key Features of Nrf2

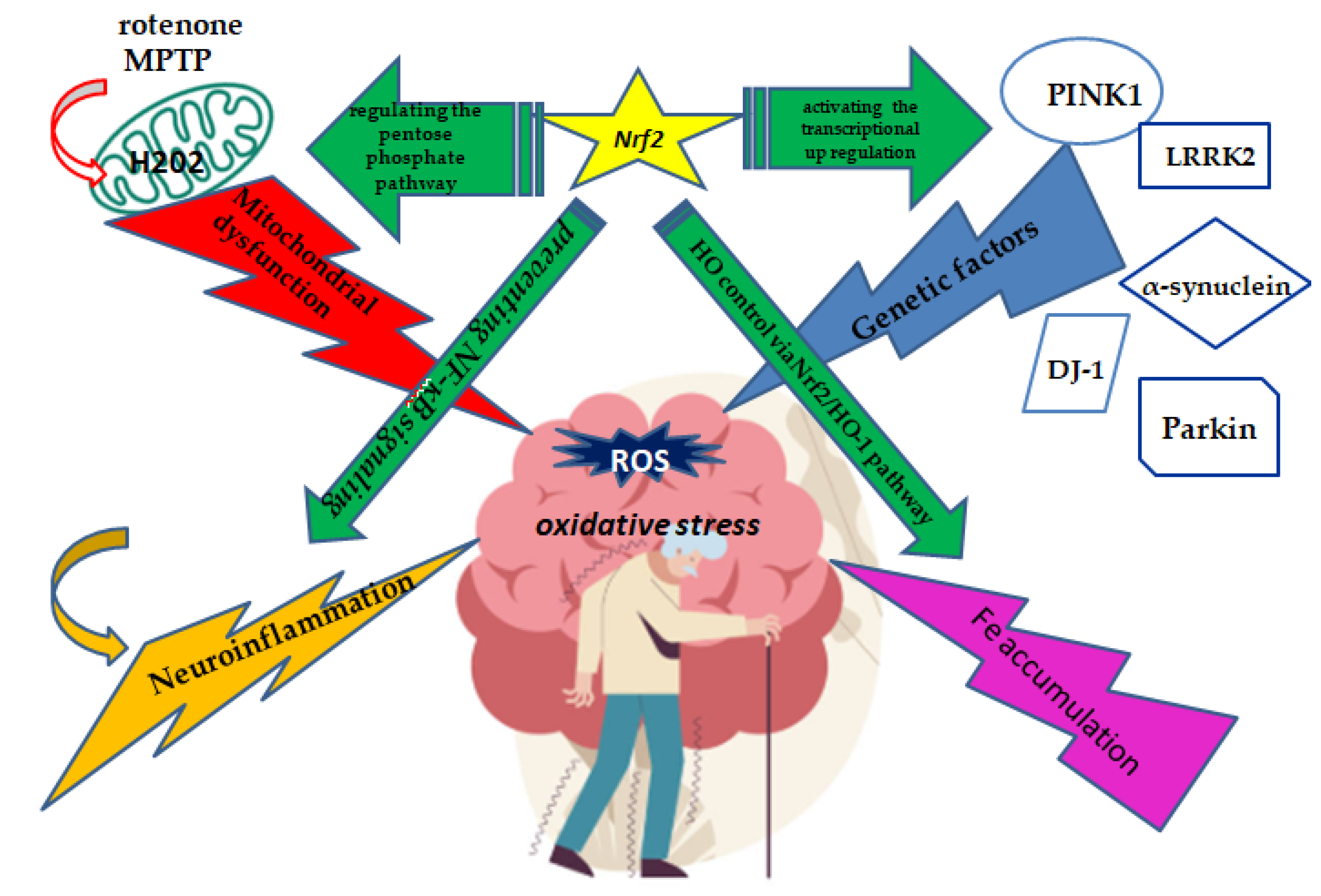

3.2. The Neuroprotective Role of Nrf2 in the Iron Death PD Related Mechanism

3.3. The Neuroprotective Role of Nrf2 in Oxidative Stress Related Mechanisms of PD Pathogenesis

3.4. The Neuroprotective Role of Nrf2 in Neuroinflammation Related Mechanisms of PD Pathogenesis

3.5. The Neuroprotective Role of Nrf2 in Dysfunctional Mitochondria Related Mechanisms of PD Pathogenesis

3.6. Activation of Nrf2 as Therapeutical Modulator of PD

3.6.1. Natural Compounds Targeting the Nrf2/HO-1 Signaling Pathway as a Neuroprotective Agent

4. Discussion

4.1. Challenges and Suggestions for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Marino, B.L.B.; de Souza, L.R.; Sousa, K.P.A.; Ferreira, J.V.; Padilha, E.C.; da Silva, C.; Taft, C.A.; Hage-Melim, L.I.S. Parkinson’s Disease: A Review from Pathophysiology to Treatment. Mini reviews in medicinal chemistry 2020, 20, 754–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mylius, V.; Möller, J.C.; Bohlhalter, S.; Ciampi de Andrade, D.; Perez Lloret, S. Diagnosis and Management of Pain in Parkinson’s Disease: A New Approach. Drugs & aging 2021, 38, 559–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, A.; Berger, K.; Chen, H.; Leslie, D.; Mailman, R.B.; Huang, X. Projection of the prevalence of Parkinson’s disease in the coming decades: Revisited. Movement disorders : official journal of the Movement Disorder Society 2018, 33, 156–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gao, L.; Chen, J.; Li, Q.; Huo, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Du, J. Pharmacological Modulation of Nrf2/HO-1 Signaling Pathway as a Therapeutic Target of Parkinson’s Disease. Frontiers in pharmacology 2021, 12, 757161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, V.; Duennwald, M.L. Nrf2 and Oxidative Stress: A General Overview of Mechanisms and Implications in Human Disease. Antioxidants (Basel, Switzerland) 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panieri, E.; Telkoparan-Akillilar, P.; Suzen, S.; Saso, L. The NRF2/KEAP1 Axis in the Regulation of Tumor Metabolism: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Perspectives. Biomolecules 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, S.; Buttari, B.; Profumo, E.; Tucci, P.; Saso, L. A Perspective on Nrf2 Signaling Pathway for Neuroinflammation: A Potential Therapeutic Target in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Diseases. Frontiers in cellular neuroscience 2021, 15, 787258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.; Zhong, Y.; Gao, B.; Zheng, B.; Liu, Y. Nrf2-mediated therapeutic effects of dietary flavones in different diseases. Frontiers in pharmacology 2023, 14, 1240433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Dong, M. Nrf2 as a potential target for Parkinson’s disease therapy. Journal of molecular medicine (Berlin, Germany) 2021, 99, 917–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakkittukandiyil, A.; Sajini, D.V.; Karuppaiah, A.; Selvaraj, D. The principal molecular mechanisms behind the activation of Keap1/Nrf2/ARE pathway leading to neuroprotective action in Parkinson’s disease. Neurochemistry international 2022, 156, 105325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moi, P.; Chan, K.; Asunis, I.; Cao, A.; Kan, Y.W. Isolation of NF-E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), a NF-E2-like basic leucine zipper transcriptional activator that binds to the tandem NF-E2/AP1 repeat of the beta-globin locus control region. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 1994, 91, 9926–9930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, K.I.; Katoh, Y.; Kusunoki, H.; Itoh, K.; Tanaka, T.; Yamamoto, M. Keap1 recruits Neh2 through binding to ETGE and DLG motifs: characterization of the two-site molecular recognition model. Molecular and cellular biology 2006, 26, 2887–2900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, S.C.; Li, X.; Henzl, M.T.; Beamer, L.J.; Hannink, M. Structure of the Keap1:Nrf2 interface provides mechanistic insight into Nrf2 signaling. The EMBO journal 2006, 25, 3605–3617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonelli, C.; Chio, I.I.C.; Tuveson, D.A. Transcriptional Regulation by Nrf2. Antioxidants & redox signaling 2018, 29, 1727–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhry, S.; Zhang, Y.; McMahon, M.; Sutherland, C.; Cuadrado, A.; Hayes, J.D. Nrf2 is controlled by two distinct β-TrCP recognition motifs in its Neh6 domain, one of which can be modulated by GSK-3 activity. Oncogene 2013, 32, 3765–3781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telkoparan-Akillilar, P.; Suzen, S.; Saso, L. Pharmacological Applications of Nrf2 Inhibitors as Potential Antineoplastic Drugs. International journal of molecular sciences 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, O.A.; Malagelada, C.; Greene, L.A. Cell death pathways in Parkinson’s disease: proximal triggers, distal effectors, and final steps. Apoptosis : an international journal on programmed cell death 2009, 14, 478–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yu, C.; Kang, R.; Tang, D. Iron Metabolism in Ferroptosis. Frontiers in cell and developmental biology 2020, 8, 590226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chorley, B.N.; Campbell, M.R.; Wang, X.; Karaca, M.; Sambandan, D.; Bangura, F.; Xue, P.; Pi, J.; Kleeberger, S.R.; Bell, D.A. Identification of novel NRF2-regulated genes by ChIP-Seq: influence on retinoid X receptor alpha. Nucleic acids research 2012, 40, 7416–7429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.C.; Vargas, M.R.; Pani, A.K.; Smeyne, R.J.; Johnson, D.A.; Kan, Y.W.; Johnson, J.A. Nrf2-mediated neuroprotection in the MPTP mouse model of Parkinson’s disease: Critical role for the astrocyte. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2009, 106, 2933–2938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh, K.; Wakabayashi, N.; Katoh, Y.; Ishii, T.; Igarashi, K.; Engel, J.D.; Yamamoto, M. Keap1 represses nuclear activation of antioxidant responsive elements by Nrf2 through binding to the amino-terminal Neh2 domain. Genes & development 1999, 13, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinkova-Kostova, A.T.; Abramov, A.Y. The emerging role of Nrf2 in mitochondrial function. Free radical biology & medicine 2015, 88, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tastan, B.; Arioz, B.I.; Genc, S. Targeting NLRP3 Inflammasome With Nrf2 Inducers in Central Nervous System Disorders. Frontiers in immunology 2022, 13, 865772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yim, J.; Hwang, Y.S.; Lee, J.J.; Kim, J.H.; Baek, J.Y.; Jeong, J.; Choi, Y.I.; Jin, B.K.; Park, S.B. Inflachromene ameliorates Parkinson’s disease by targeting Nrf2-binding Keap1. Chemical science 2024, 15, 3588–3595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawelec, P.; Ziemka-Nalecz, M.; Sypecka, J.; Zalewska, T. The Impact of the CX3CL1/CX3CR1 Axis in Neurological Disorders. Cells 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, L.; Johnson, D.A.; Johnson, J.A. Keap1-Nrf2 activation in the presence and absence of DJ-1. The European journal of neuroscience 2010, 31, 967–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrich, M.T.; Oertel, W.H.; Surmeier, D.J.; Geibl, F.F. Mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease—a key disease hallmark with therapeutic potential. Molecular neurodegeneration 2023, 18, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasai, S.; Shimizu, S.; Tatara, Y.; Mimura, J.; Itoh, K. Regulation of Nrf2 by Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species in Physiology and Pathology. Biomolecules 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.; Wang, R.S.; Handy, D.E.; Loscalzo, J. NAD(H) and NADP(H) Redox Couples and Cellular Energy Metabolism. Antioxidants & redox signaling 2018, 28, 251–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Zheng, J.; Ma, J.; Wang, Z.; Shi, X.; Li, M.; Huang, S.; Hu, S.; Zhao, Z.; Li, D. Increased Plasma Heme Oxygenase-1 Levels in Patients With Early-Stage Parkinson’s Disease. Frontiers in aging neuroscience 2021, 13, 621508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schipper, H.M. Heme oxygenase expression in human central nervous system disorders. Free radical biology & medicine 2004, 37, 1995–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.Y.; Son, T.G.; Park, H.R.; Jang, Y.J.; Oh, S.B.; Jin, B.; Lee, J. Naphthazarin has a protective effect on the 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydropyridine-induced Parkinson’s disease model. Journal of neuroscience research 2012, 90, 1842–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, K.T.; Ko, M.C.; Chen, B.Y.; Huang, J.C.; Hsieh, C.W.; Lee, M.C.; Chiou, R.Y.; Wung, B.S.; Peng, C.H.; Yang, Y.L. Neuroprotective effects of resveratrol on MPTP-induced neuron loss mediated by free radical scavenging. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry 2008, 56, 6910–6913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Tang, X.Q.; Zhi, J.L.; Cui, Y.; Yu, H.M.; Tang, E.H.; Sun, S.N.; Feng, J.Q.; Chen, P.X. Curcumin protects PC12 cells against 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium ion-induced apoptosis by bcl-2-mitochondria-ROS-iNOS pathway. Apoptosis : an international journal on programmed cell death 2006, 11, 943–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathore, A.S.; Singh, S.S.; Birla, H.; Zahra, W.; Keshri, P.K.; Dilnashin, H.; Singh, R.; Singh, S.; Singh, S.P. Curcumin Modulates p62-Keap1-Nrf2-Mediated Autophagy in Rotenone-Induced Parkinson’s Disease Mouse Models. ACS chemical neuroscience 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Q.; Zou, Q.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Qu, Y.; Wang, N.; Murayama, S.; Qi, Q.; Hashimoto, K.; Lin, S.; et al. Regulation of BDNF transcription by Nrf2 and MeCP2 ameliorates MPTP-induced neurotoxicity. Cell death discovery 2022, 8, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jazwa, A.; Rojo, A.I.; Innamorato, N.G.; Hesse, M.; Fernández-Ruiz, J.; Cuadrado, A. Pharmacological targeting of the transcription factor Nrf2 at the basal ganglia provides disease modifying therapy for experimental parkinsonism. Antioxidants & redox signaling 2011, 14, 2347–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, H.C.; Wang, M.H.; Fang, C.H.; Lin, Y.W.; Soung, H.S. Neuroprotective Potentials of Berberine in Rotenone-Induced Parkinson’s Disease-like Motor Symptoms in Rats. Brain sciences 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Li, W.; Su, Z.Y.; Kong, A.N. The complexity of the Nrf2 pathway: beyond the antioxidant response. The Journal of nutritional biochemistry 2015, 26, 1401–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturchio, A.; Rocha, E.M.; Kauffman, M.A.; Marsili, L.; Mahajan, A.; Saraf, A.A.; Vizcarra, J.A.; Guo, Z.; Espay, A.J. Recalibrating the Why and Whom of Animal Models in Parkinson Disease: A Clinician’s Perspective. Brain sciences 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, N.; Ferger, B. Neurochemical findings in the MPTP model of Parkinson’s disease. Journal of neural transmission (Vienna, Austria : 1996) 2001, 108, 1263–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.T.; Dodson, M. The untapped potential of targeting NRF2 in neurodegenerative disease. Frontiers in aging 2023, 4, 1270838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagishita, Y.; Gatbonton-Schwager, T.N.; McCallum, M.L.; Kensler, T.W. Current Landscape of NRF2 Biomarkers in Clinical Trials. Antioxidants (Basel, Switzerland) 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, W.; Guo, L.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xia, S.; Gong, H.; Zhang, B.K.; Yan, M. Dissecting the Crosstalk Between Nrf2 and NF-κB Response Pathways in Drug-Induced Toxicity. Frontiers in cell and developmental biology 2021, 9, 809952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robledinos-Antón, N.; Fernández-Ginés, R.; Manda, G.; Cuadrado, A. Activators and Inhibitors of NRF2: A Review of Their Potential for Clinical Development. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity 2019, 2019, 9372182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Kang, N.; Liu, Y.; Xu, G. Formononetin Exerts Neuroprotection in Parkinson’s Disease via the Activation of the Nrf2 Signaling Pathway. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland) 2024, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, C.; Riera-Ponsati, L.; Kauppinen, S.; Klitgaard, H.; Erler, J.T.; Hansen, S.N. Targeting the NRF2 pathway for disease modification in neurodegenerative diseases: mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Frontiers in pharmacology 2024, 15, 1437939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinkova-Kostova, A.T.; Copple, I.M. Advances and challenges in therapeutic targeting of NRF2. Trends in pharmacological sciences 2023, 44, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashino, T.; Yamamoto, M.; Numazawa, S. Nrf2 Antioxidative System is Involved in Cytochrome P450 Gene Expression and Activity: A Delay in Pentobarbital Metabolism in Nrf2-Deficient Mice. Drug metabolism and disposition: the biological fate of chemicals 2020, 48, 673–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, K.I.W.; Moreno, E.L.; Hachi, S.; Walter, M.; Jarazo, J.; Oliveira, M.A.P.; Hankemeier, T.; Vulto, P.; Schwamborn, J.C.; Thoma, M.; et al. Automated microfluidic cell culture of stem cell derived dopaminergic neurons. Scientific reports 2019, 9, 1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolognin, S.; Fossépré, M.; Qing, X.; Jarazo, J.; Ščančar, J.; Moreno, E.L.; Nickels, S.L.; Wasner, K.; Ouzren, N.; Walter, J.; et al. 3D Cultures of Parkinson’s Disease-Specific Dopaminergic Neurons for High Content Phenotyping and Drug Testing. Advanced science (Weinheim, Baden-Wurttemberg, Germany) 2019, 6, 1800927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Authors, year | Agent | Model | AdministrationRoute/ Dosage | Assessment tools/ measures | Neuroprotective Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chen et al. 2006 | curcumin | PC12 cells | MTT solution (final concentration, 0.5 mg/ml) for 4 h | FCM iNOS and Bcl-2 |

decrease in cell viability in PC12 cells and overexpression of Bcl-2 |

| Jazwa et al. 2011 | SFN | Nrf2 + / + and Nrf2—/ - mice | Intraperitoneal | protein levels of MAO-B DAT |

Attenuates the MPTP-induced dopaminergic neuron damage and astrogliosis |

| Cao et al.2022 | SFN |

MPP+ treated SH-SY5Y cells

MPTP-treated mouse model |

i.p SFN (10 mg/kg) and MPTP (30 mg/kg) | rotarod test | Ameliorate dopaminergic neurotoxicity via activation of BDNF and suppression of MeCP2 |

| Rathore et al. 2023 | curcumin | subcutaneous injection | Nrf2, Keap1, p62, LC3, Bcl2, Bax, and caspase 3 | autophagy-mediated clearance of misfolded α-syn proteins by increasing the LC3-II expression and blocked apoptotic cascade | |

| Tseng et al. 2024 | BBR | RTN model rat |

subcutaneous RTN at 0.5 mg/kg for 21 days orally BBR at 30 or 100 mg/kg doses |

open-field, bar catalepsy, beam-crossing, rotarod, and grip strength TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 levels |

modulation of the Nrf2-mediated pathway via the activation of PI3K/Akt, p38, and HO-1 expressions |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).