2.2.2. Advanced TEA Programs and Program Debugging via The TEA DEBUGGER

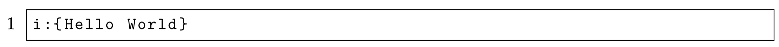

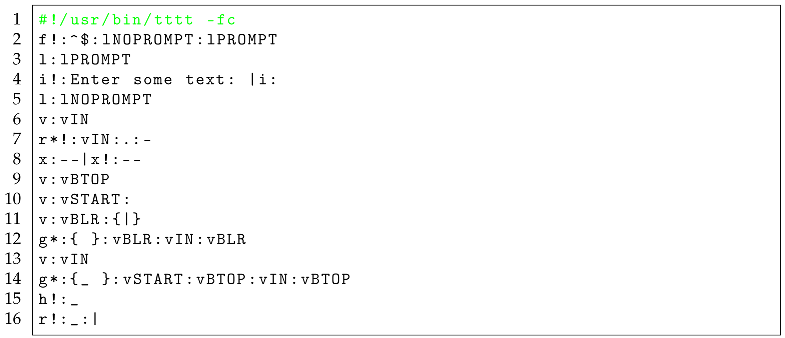

The program in Listing is a basic TEA program meant to draw a simple textbox around some text the user provides — either at invocation time or at run-time.

|

Listing 2.A Textbox Drawing Program in TEA |

|

In

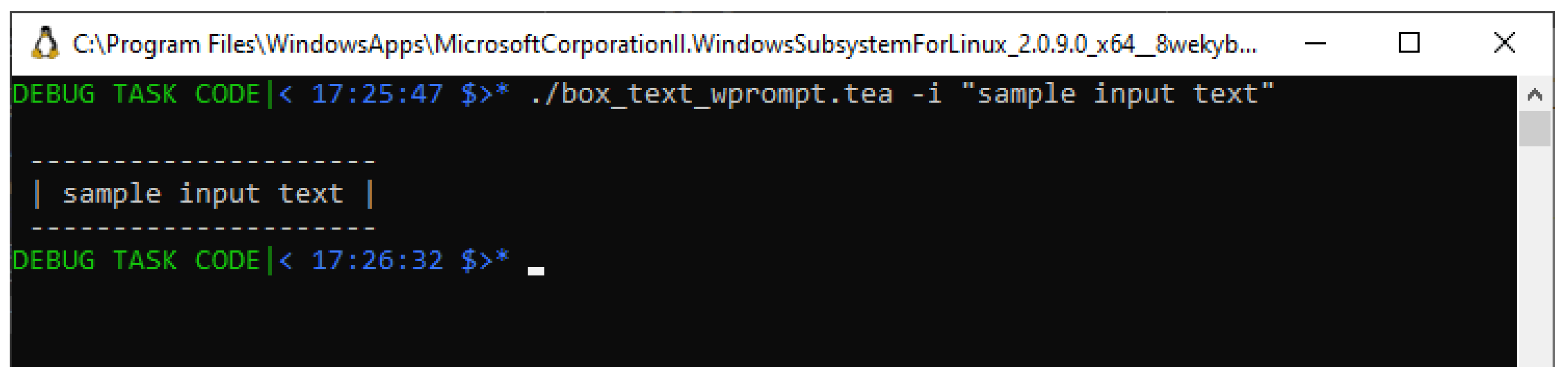

Scenario 1, let us look at what happens when that program from Listing is invoked with an explicit input text specified at invocation time — refer to

Figure 3, in which case the user invokes the program’s script with the explicit input as the string “sample input text".

We see, by looking at the provided screenshot, that the program indeed obeys the logic in the TEA program — refer to

Line #2 in Listing , which controls the TEA program thus; in case the program at that moment — which, given this is the first instruction in the program; happens immediately after the TEA program’s code starts to be interpreted/processed — happens to have some non-empty value in the active memory — what in TEA is called the “Active Input", or rather “AI" (refer to the

TEA TAZ for details [

3]), and this because the instruction uses the condition

^$ — a regular expression matching an empty string, to test for whether the AI is

NOT empty — because of the

! qualifier applied to the

f: —

[conditionally] Fork TEA command, then, we jump to the location/sector in the TEA program under the label

lNOPROMPT since we need not prompt for an input

then. However, if there was no explicit input provided — meaning AI is empty at the instruction on

Line #2, then we jump to the sector or code-block under the label

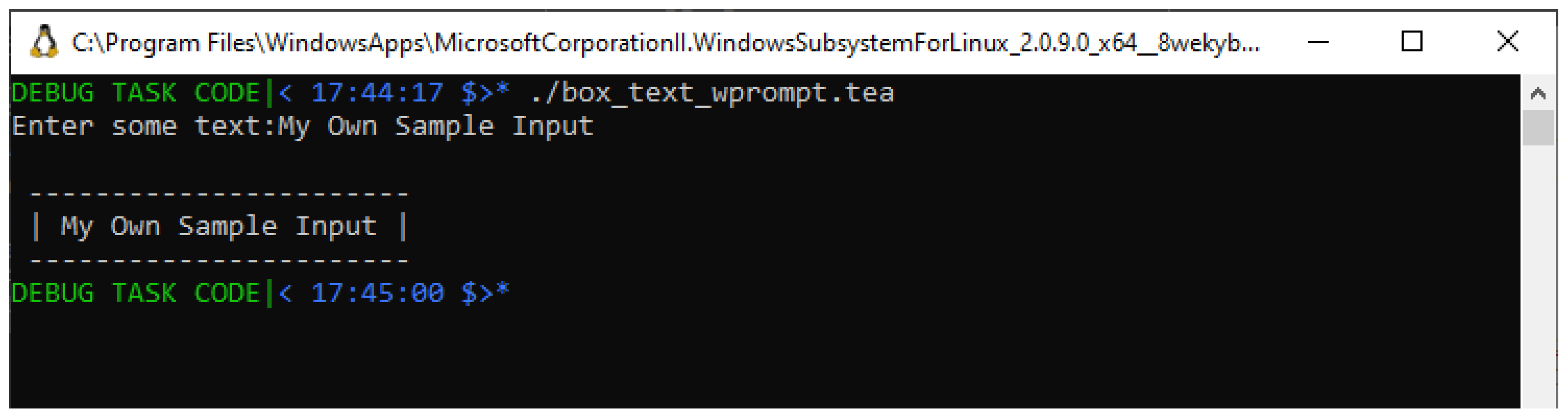

lPROMPT. As can be seen in the screenshot in

Figure 4, invoking the same program in Listing without an explicit input shall result in the TEA runtime prompting for user input as per the [two] instructions on

Line #4.

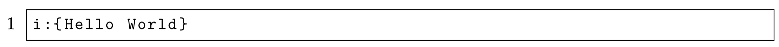

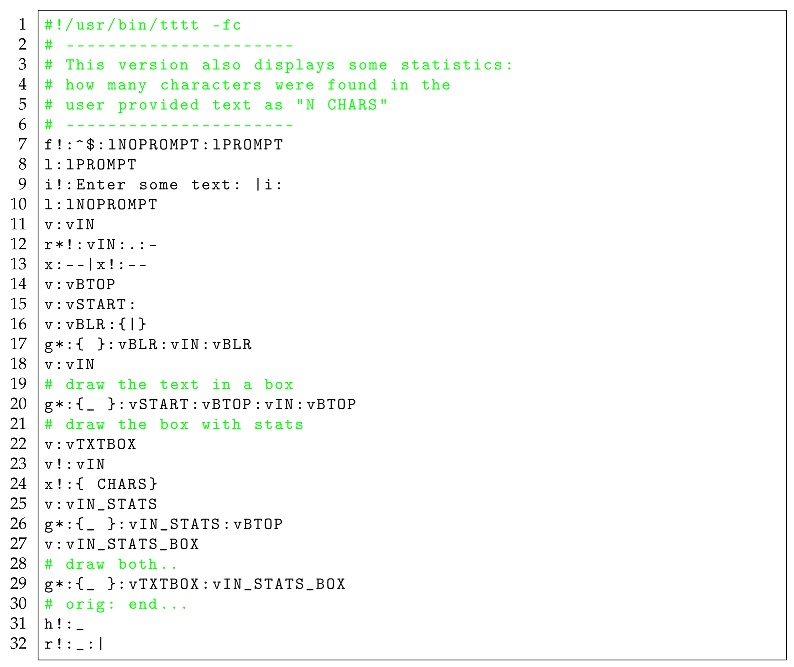

So, to appreciate how TEA DEBUGGING works, let us take a moment to look at yet another version of the program in Listing .

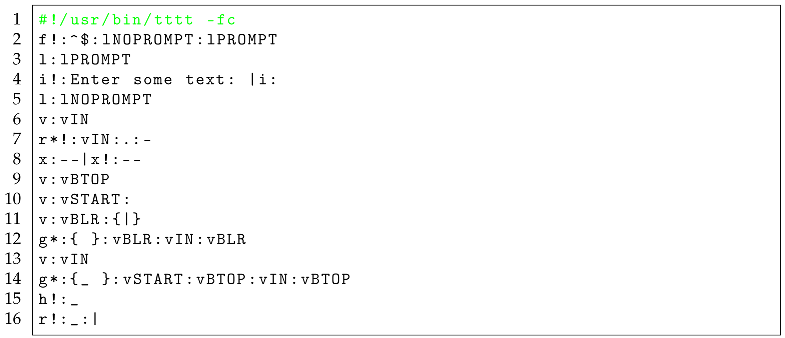

The version of the Textbox Drawing Program shown in Listing is meant to improve on the one in Listing by doing just one extra thing: Drawing an extra textbox below the one with the input text, merely showing the basic statistic of “how many characters" were found in the input text; e.g. for the input string “Hello", it should draw a textbox containing that word alone, and then a second one below that, containing just the information “5 CHARS".

|

Listing 3.A Textbox Drawing Program in TEA with STATISTICS |

|

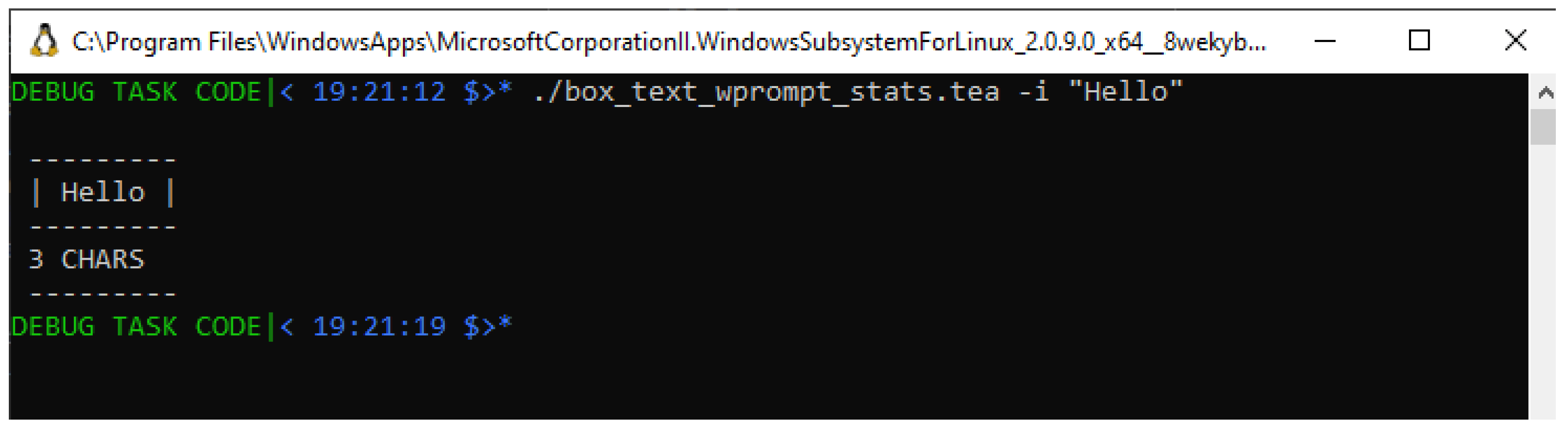

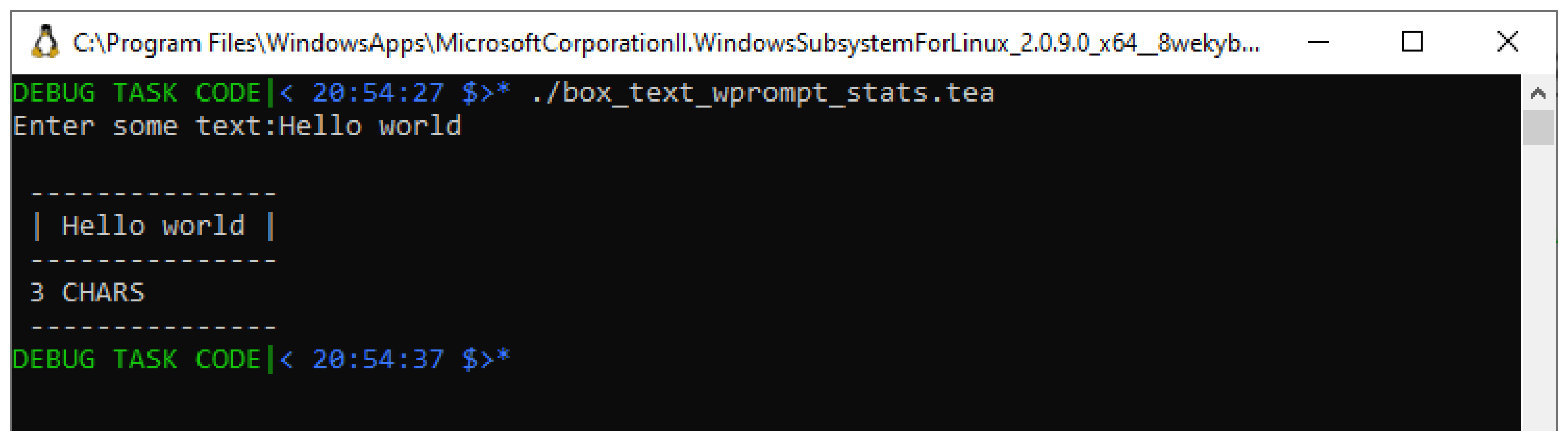

When we attempt to run the TEA program in Listing with the explicit input “Hello" as introduced above, we see that the program then produces the output shown in

Figure 5

You shall immediately notice that this screenshot in

Figure 5 doesn’t seem to produce the result we expect; in particular, the input that was provided, is the string “Hello", which by basic enumeration of the characters it contains,

is expected to report a CHARACTER COUNT equivalent to “5" — not the reported “3 CHARS".

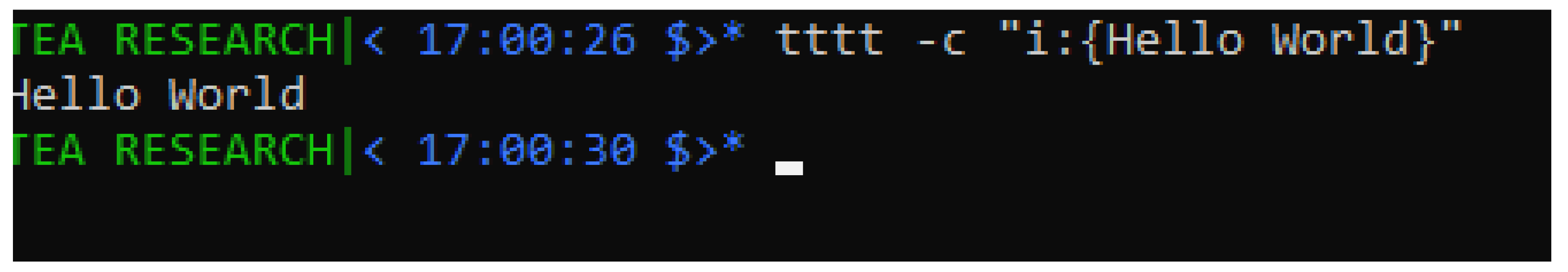

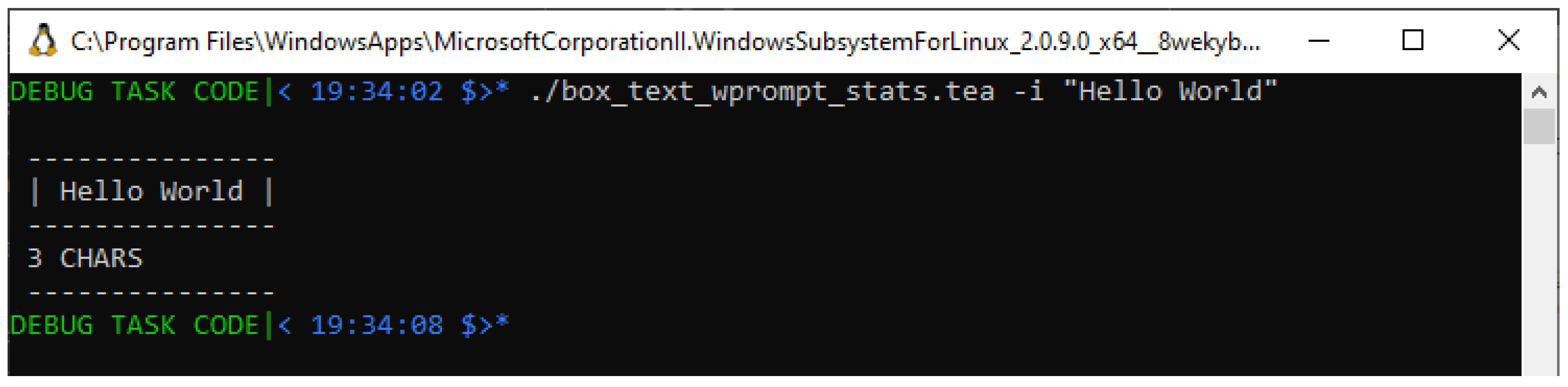

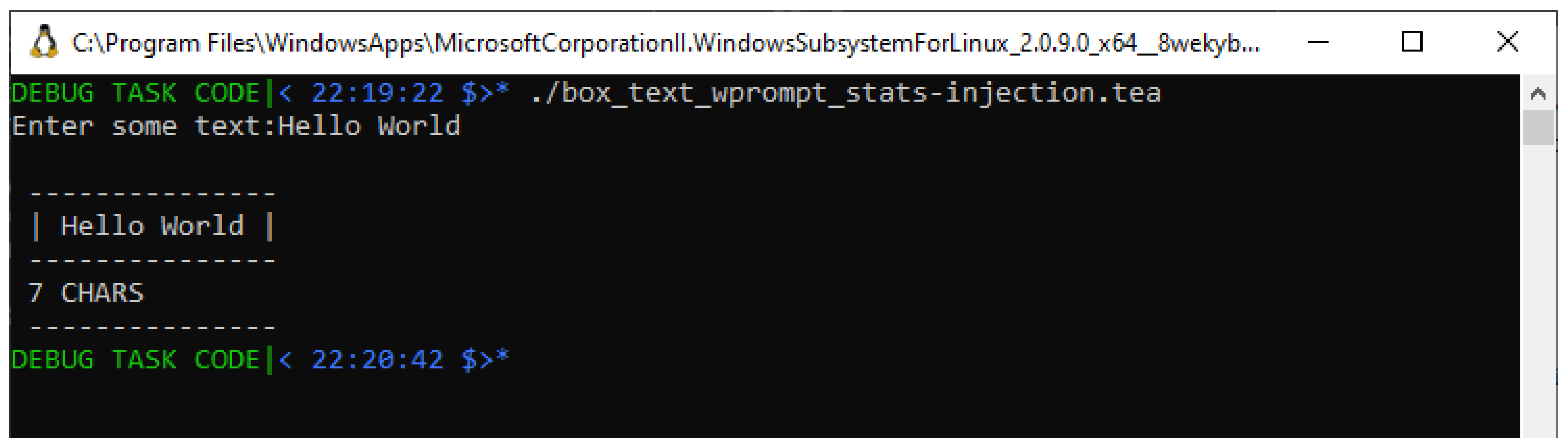

To establish whether indeed we are dealing with a potential BUG in that program, we might invoke it again with a different input string — for example, with the longer string “Hello World" — which we expect to tally to “11 CHARS". So, looking at what happens when we invoke the program in Listing with such an explicit input — see

Figure 6, we surely find that

instead of the Expected Output of “11 CHARS", this program AGAIN reports the erroneous output “3 CHARS".

2.2.3. The Debugging Process in TEA

Because software debugging is not just about identifying a problem in the software but also resolving it (see Definition 1) [

5], a good way to approach debugging problems then must also include a sane dose of how to understand the

nature and

root-cause of the problem thus identified, so as to eventually eliminate it. To use the terminology and philosophy of other researchers and authorities on the subject; in debugging software, we must begin by clearly understanding what exactly is going on; so-called

fault localization [

7] — which basically is about identifying where in the problematic source-code of the program the error seems to originate from. That attempt to localize the bug might be approached by careful attempts to reproduce the error or bug [

8], while eliminating invalid hypotheses of where it is that the error is originating from in the system. We must then proceed to

fault understanding [

7], which basically deals with getting to understand the root-cause of the problem/bug thus identified — and this, we realize might proceed by careful stripping down of the original program into smaller or more manageable instances or perhaps leveraging more focused “test cases" for the bug, so that we eventually arrive at a clearer, closest-to-root-cause understanding of the problem [

8]. Thereafter, and also finally, we must apply some remedial actions — so-called

fault correction, so that a means to “fix" the program’s source-code; basically, eliminating the problematic behavior from the program by modifying it as necessary, is conducted, and thus the root-cause of the bug is thus eliminated. That is essentially what debugging is about [

7].

With the above theoretical insights to aid our approach to debugging in TEA, we can then return to our example debugging task in

Section 2.2.2, and deal with the bug we have seen manifest in the outputs of running the TEA program in Listing .

As of this moment in our debugging process, we are still trying to locate where exactly the bug is originating from —

fault localization, however, we also wish to understand exactly what this bug is so we can clearly pinpoint where it is in the program. Thus, to better clarify on what the bug is, we must add to the two tests we’ve already run in the cases illustrated in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6; one with the explicit input “Hello", the other with “Hello World".

First, to pinpoint where the bug is originating from, we note — since we have some good understanding of the TEA language semantics[

3], that the potentially erroneous section of the problematic program should be around the section where we approach the computation of the length of the input text. Thus, revisiting our program in Listing , we note that the problematic sections should be the

Lines #22-#27; the section dealing with both computing and presenting the statistic of interest.

To test whether this is where the problem is actually originating from, we note that in particular, the instruction at Line #23 seems to be where the problem is. Why? Perhaps because, we know that whatever happens past that instruction — such as in instruction on Line #24 where we construct the text reporting the statistic; using the x!: — Xenograft TEA primitive with the ! qualifier which then implies we wish to affix the provided suffix “ CHARS" to AI — where it is understood that AI, the Active Input, shall at that moment contain just a number — the computed length of the text we wish to report the length for.

To test whether indeed we are looking at the right section in the code, we might conduct two more tests;

We might instead run the same program but with the input to be processed obtained using a different method; for example, instead of the explicit, command-line input argument approach shown in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6, we could let the program prompt for a run-time user-provided input so we see if we might obtain the correct or a different statistic in the result.

Alternatively, we might forego all user input, and inject an explicit input for which we know the exact length, right before we compute the input’s length, and thus determine if the problem is either with our program logic or perhaps with the underlying TEA language semantics or runtime.

So, starting with Test Case #1 above, we run the same, unmodified program from Listing , however, this time, not providing an explicit invocation-time input, and instead letting the program proceed to prompt for a user input (see instructions on

Lines #9; the first being the prompt, the other the one capturing the input the user provides). We can see an instance of this test running in a screenshot in

Figure 7, in which case the run-time input we provide is still “Hello World".

Having run this 3rd test case, and still finding that instead of the expected “11 CHARS" the program, despite having used an input provided in a different way still reports the erroneous “3 CHARS", we seem to now be getting closer to the actual source of the problem.

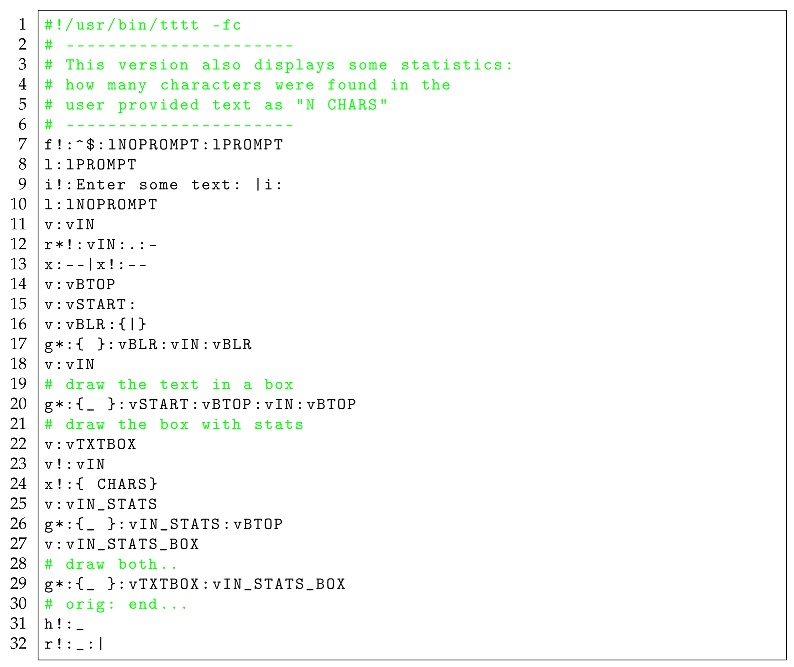

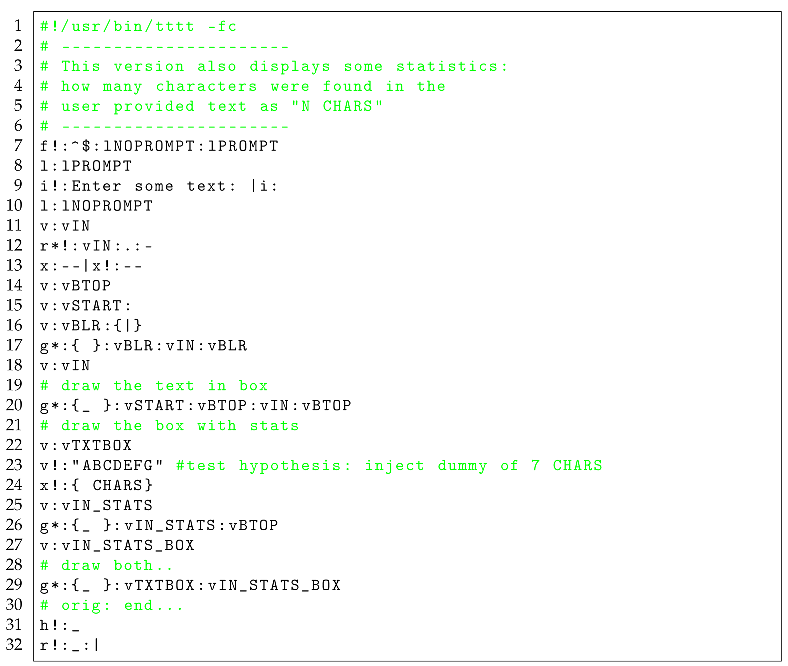

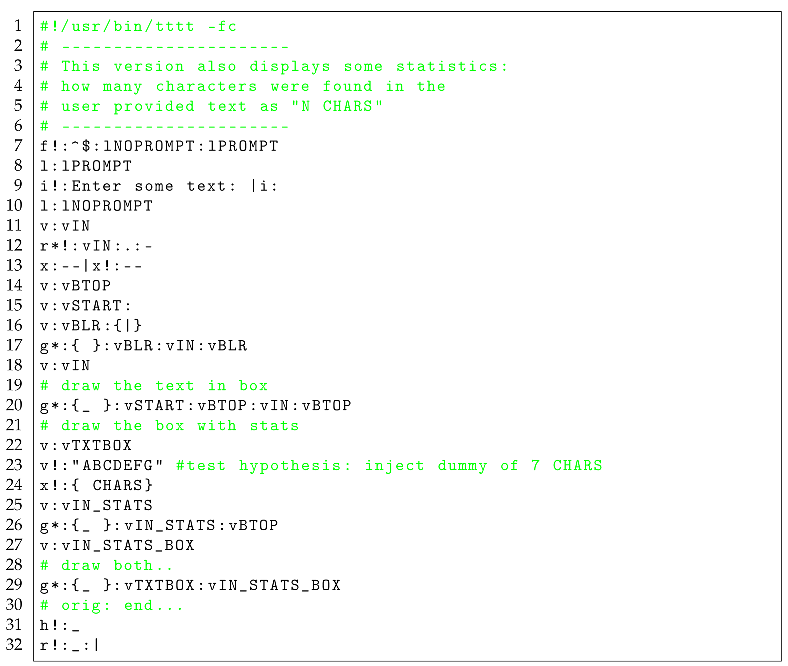

We then attempt a better localization of the fault, by proceeding to implement the Test Case #2 specified above; we basically modify the program in Listing as shown in Listing .

|

Listing 4.A MODIFIED Textbox Drawing Program in TEA with STATISTICS |

|

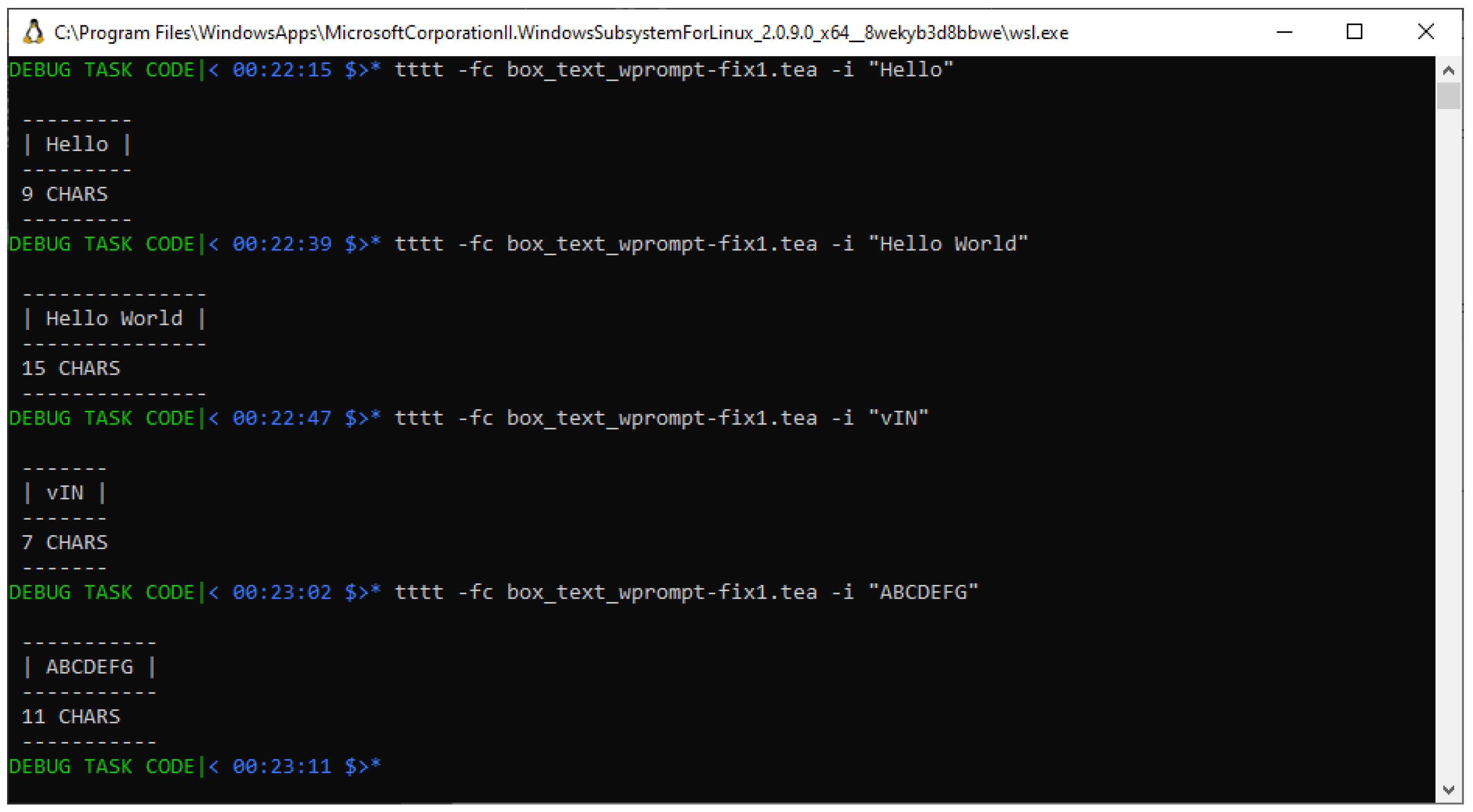

In particular, looking at the altered program in Listing , we particularly note that the modified instruction — see

Line #23: effectively, the new instruction being

v!:"ABCDEFG", injects the explicit string “ABCDEFG" of 7 characters in length, and indeed, as we see in the screenshot after running this modified program — see

Figure 8, we notice that now, given the same [run-time] input — “Hello World", of 11 characters, as we’ve used in the tests shown in

Figure 6 and

Figure 7, we then see our new test case present a

different result; “7 CHARS" it says, which is exactly proving our hypothesis that the code/instruction(s) computing the input’s length must be where the problem has been stemming from.

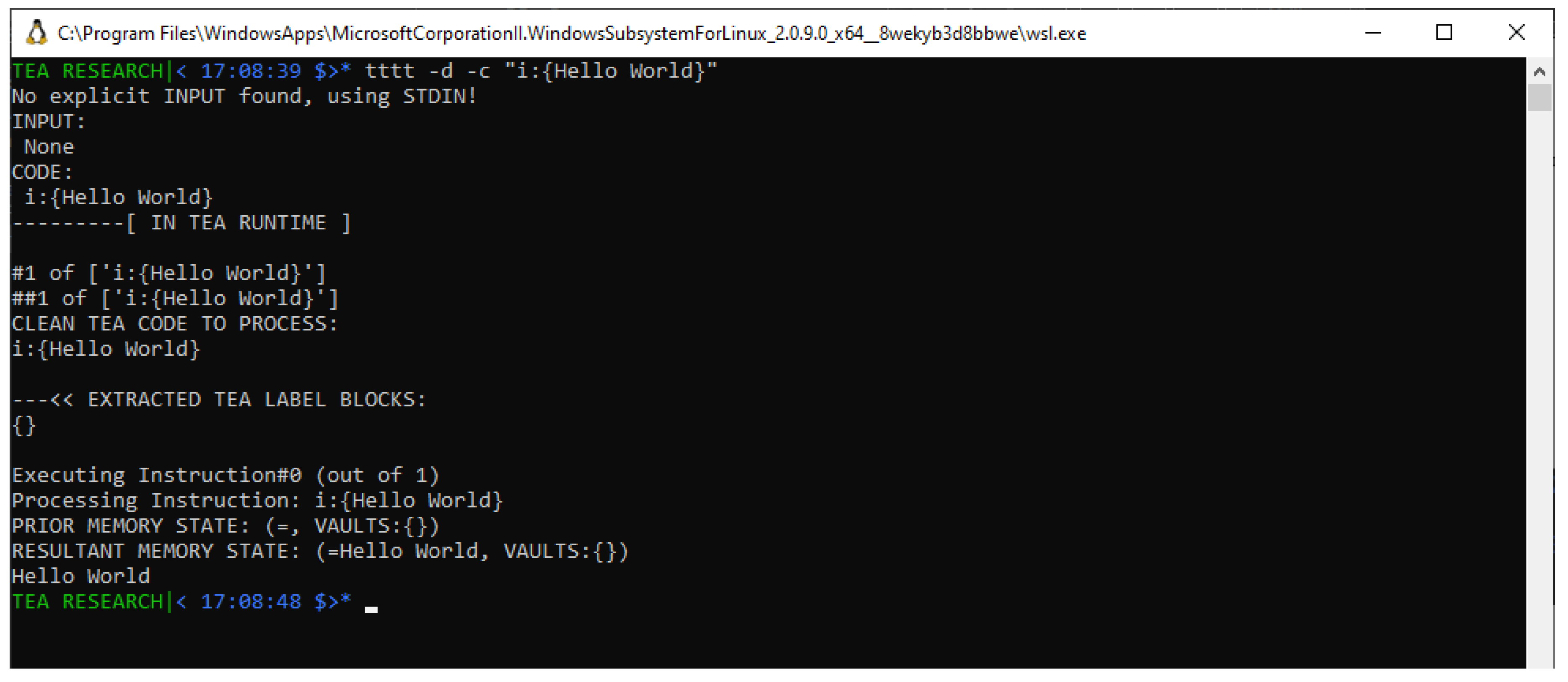

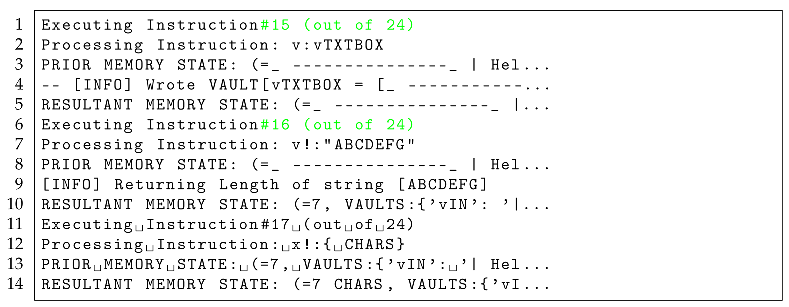

At this point then, we must bring the TEA DEBUGGER into context once more; given that we have an idea where the problematic code is within the program — in particular, having noticed that modifying Line #23 seems to be causing alterations in the error/bug, we can then use the DEBUG MODE of tttt, to ascertain what exactly is going on both in our program as well as the TEA runtime when this bug manifests.

For this case, we shall invoke the same program as in Listing , but with the addition of the “-d" flag to the TEA interpreter when we invoke it. Also, this time, we shall return to passing an explicit invocation-time input parameter as in the case demonstrated in

Figure 6. The invocation we are to make is:

tttt -fc box_text_wprompt_stats-injection.tea -d -i "Hello World"

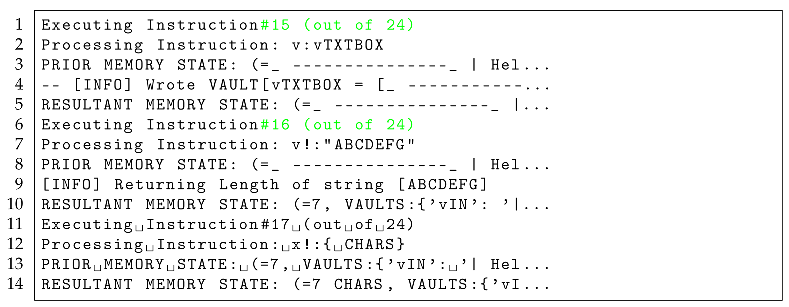

And making this call, we notice as captured in the TEA debugger dump

1 for this test as captured in a Github Gist, that indeed, around

Lines #165-#168, also shown [with long lines truncated with ellipses] in Listing — see

Lines #6-#10, that indeed, the debugger reports that the instruction we just modified is in fact computing the length of the string “ABCDEFG" and not our input “Hello World" as we had originally intended.

|

Listing 5.Excerpt of TEA debugger Trace Dump |

|

Thus, we are done with our fault localization, and have also enhanced our fault understanding. Now, we must embark on fault correction!

Of course, when it comes to fixing the bugs thus identified in a software system such as we are currently looking at, one could leverage several things as far as addressing the identified error is concerned; by manipulating the problematic program as through experimentation, the identified [and/or visible] problem with a system might be eliminated — but, this doesn’t necessarily imply that the underlying cause of the problem has been addressed[

7]. But also, knowledge — both via experience as well as that of the problem domain and technicalities of the system under development can help the software engineer or developer to arrive at a sufficient solution for the problem at hand once it has been identified and well understood.

In our case, since we have isolated the instruction causing the problem in our target program, we can look at it critically, and with knowledge of what it is we originally intended to achieve versus what is actually happening, and then proceed to try out some potentially effective solutions. In particular, looking at the problematic instruction (Line #23 in Listing ) in the original program before we modified it:

v!:vIN

We notice the following telling problems:

-

First of all, we notice that, the instruction was meant to actually compute the length of a string stored in a vault — essentially, a kind of pointer, however, based on the known semantics of TEA instructions, we can tell with sufficient knowledge that this instruction signature isn’t possibly doing the right thing. Why?

- (a)

We know that the convention in TEA is that vault-accessing instructions use the

* qualifier against the TEA primitive command of interest so as to make it clear they are meant to manipulate some pointer [

3]. However, this instruction’s signature, though it is qualified with

!, which for the

v: command also maps to length-computation operations, is missing the expected

* qualifier!

- (b)

By looking at the semantics of the v: — Vault TEA command in the TEA TAZ, we find that indeed, the correct variant of this command for the computation of the length of a string held in a vault is the command with the signature: v*!:vNAME — which is defined as “Return the length of what is stored in the vault vNAME. Without vNAME, is like v!:"

Further, by looking at the evidence we amassed while testing around this bug in the cases above, we see that, before we modified the instruction — such as in Listing ), the program was reporting the length of the input as “3 CHARS", which, looking at the above problematic instruction signature as well as what we just uncovered concerning the computation of the length of strings held in TEA vaults, is enough to explain why the result was always “3 CHARS" irrespective of the input passed to the program; basically, as it was, the instruction on Line #23 in Listing was treating the provided instruction argument vIN as an explicit string and not as the pointer to the vault with the name “vIN"! And so, it was correct to return the length of the string as 3, because that’s how many characters are in that instruction’s argument when treated as a literal string!

Thus, armed with the above context and potential theories for why the bug was manifesting, we can then embark on a hunt for a potentially final solution thus: we shall go back to the program of interest in Listing , modify it so as to eliminate the wrong instruction on line Line #23, and make any other necessary modifications so as to fix the error.

Solution#1: First of all, by merely correcting the instruction signature in that program on Line #23 to the following:

v*!:vIN

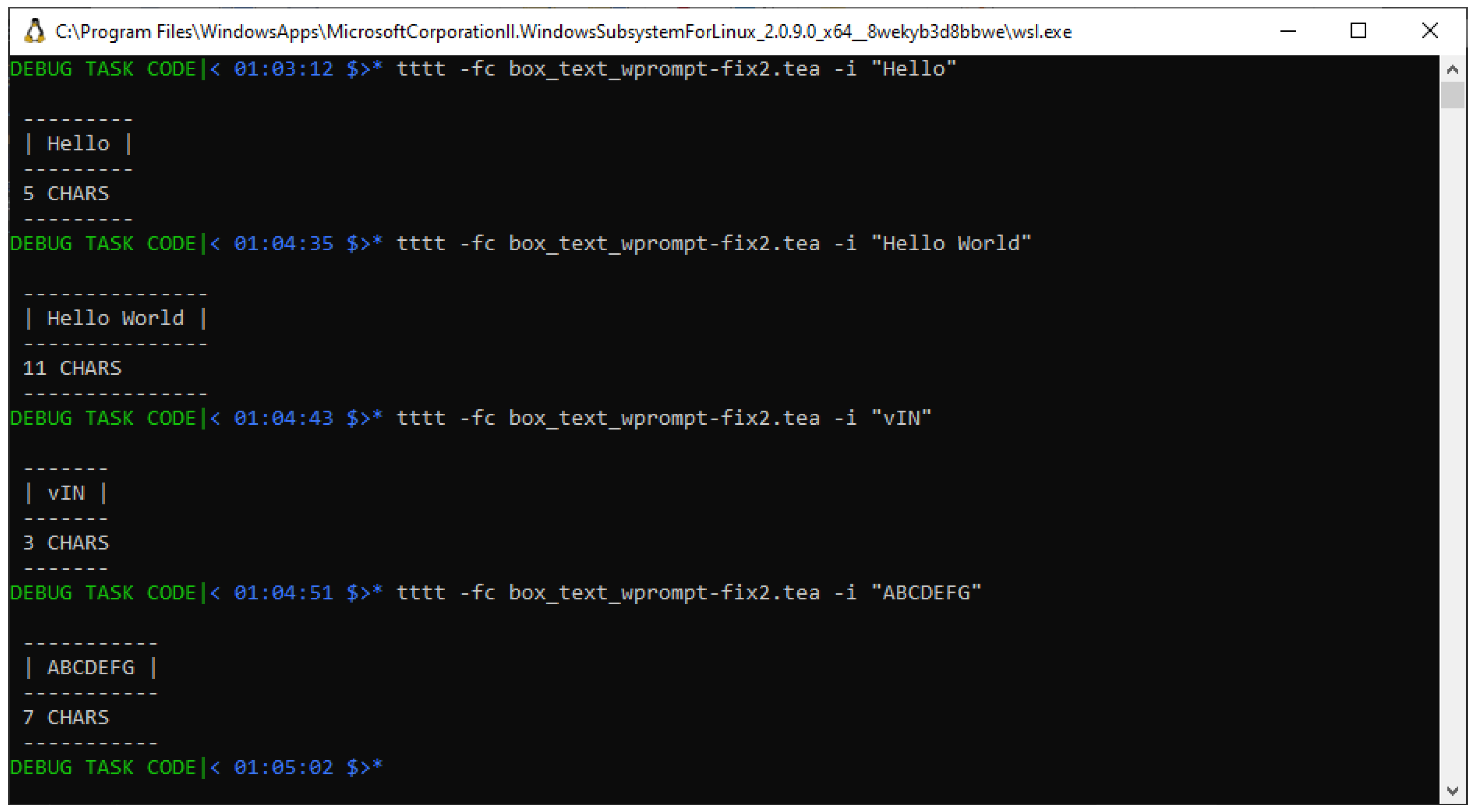

We notice that re-running the program with that fix now starts to produce meaningful outputs as shown in the screenshot in

Figure 9; in particular, notice that the reported statistics

nowsomewhat correspond to the expected values – see

Table 1.

Thus we see that despite the solution having addressed the lack of variance in the computed input statistic as was the case in the problematic program in Listing , and yet, still with this solution, we haven’t yet obtained the exact solution we originally set out to accomplish — but we are somewhat closer to a solution.

A further scrutiny of the original program, together with this newly introduced solution shall reveal some other problems such as:

We notice that, now that we are correctly referencing the input in the modified instruction on

Line #23, and yet, the discrepancy in the input lengths computed as shown in

Table 1 begs for an explanation!

-

A closer looks then, reveals that, despite the modified instruction referencing the original vault holding the input value — which, we see being set on Line #11 in Listing in the instruction:

v:vIN

And yet, before we compute the length of the value in vIN on Line #23, we notice that this value gets overridden by the instruction on Line #18; basically, the following instruction that occurs before that:

g*:{ }:vBLR:vIN:vBLR

Pads the actual input in

vIN with 2 characters before and after as part of the code for constructing the string that will be used to display the final text in the textbox, thus the

4 extra characters we see being reported in

Table 1!

Thus we come to

Solution#2: Basically, apart from what we have already done in

Solution#1, we shall also need to ensure that the original input value is exactly what we are computing the length against, and not some later modification of it. Thus, with this in mind, we arrive at the correct program as depicted in Listing , and which we correctly see performing as shown in

Figure 10 and which results are likewise depicted in

Table 2.

|

Listing 1.A Textbox Drawing Program in TEA with STATISTICS After SOLUTION#2 |

|

Thus we come to the conclusion of a practical exploration of how software debugging is conducted or approached in TEA, the TEA SOE or with the TEA RI runtime. In the next section, we shall wrap it up with a quick summary of all that TEA debugging does from a high-level.