Submitted:

18 February 2025

Posted:

19 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

The exploration of alternatives to the use of animal models and cell cultures has culminated in the creation of organ-on-a-chip systems in which organs in physio-pathological conditions and their reactions to the presence of external stimuli are simulated. In addition, they support the recreation of tissue interfaces such as tissue-air, tissue-liquid and tissue-tissue, which are very similar to those present in vivo, even through the presence of biomechanical stimuli. In this way they are best suited to mimic biological barriers, such as the skin, placenta, blood-brain barrier and others, which are characterized by tissue interface and their functioning is important to ensure the homeostasis of the organism. This review shows the different biological membranes that we can simulate within an organ-on-chip, also using induced pluripotent stem cells to act in the direction of personalized medicine. Different methods that can be used to detect barrier formation, including the integration of electrodes for real-time monitoring, are also explained, highlighting advantages and challenges.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

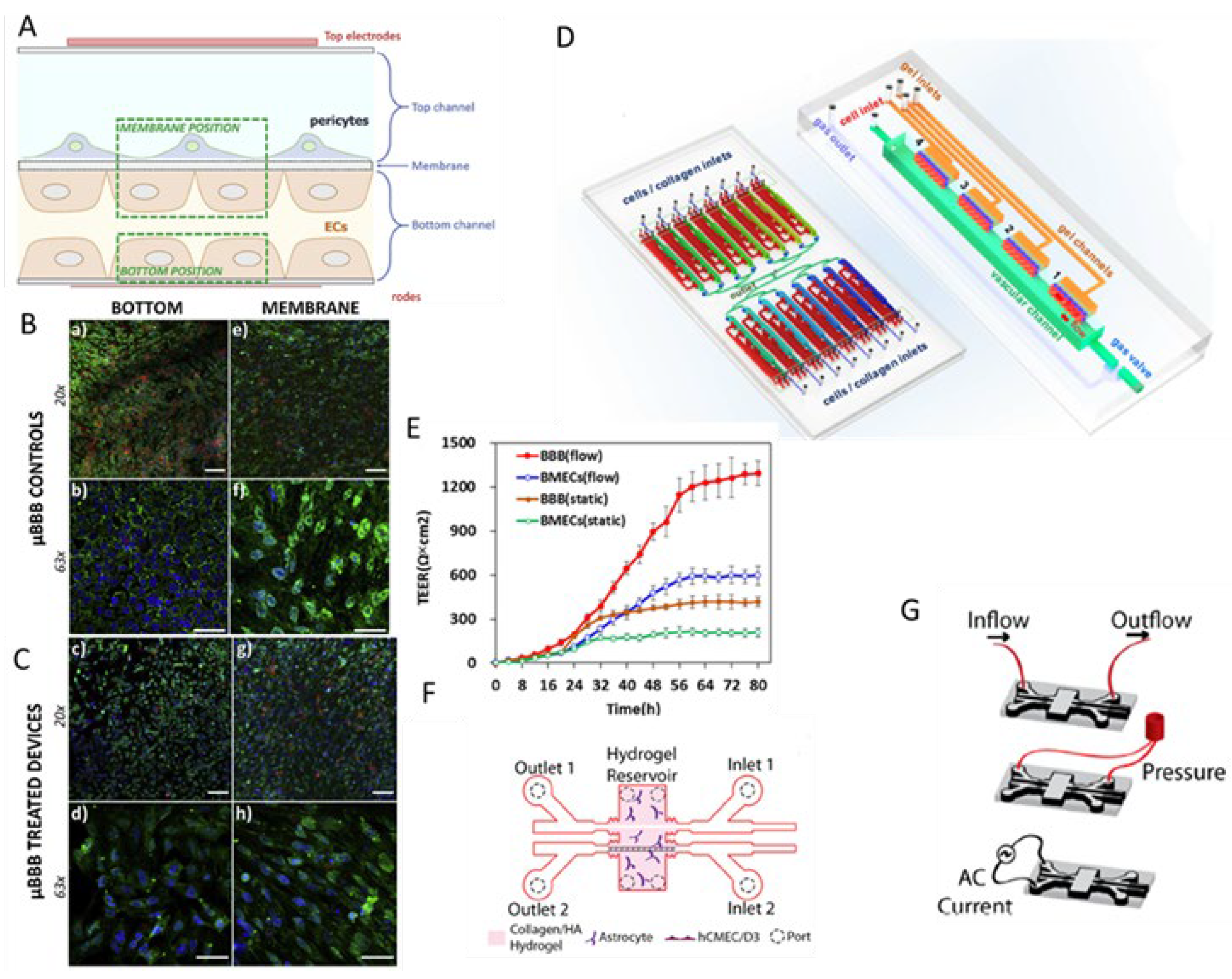

2. Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB) on-a-Chip

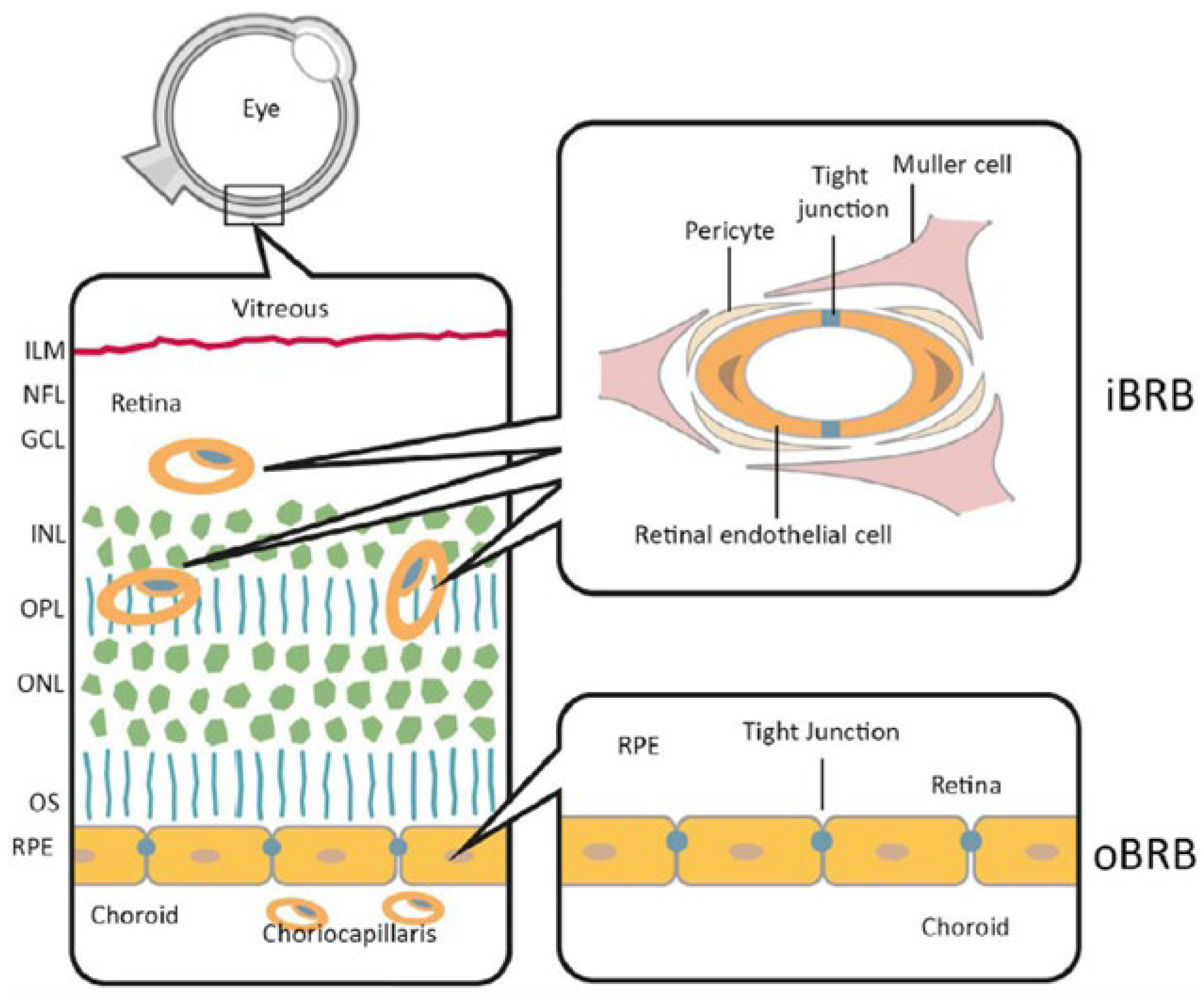

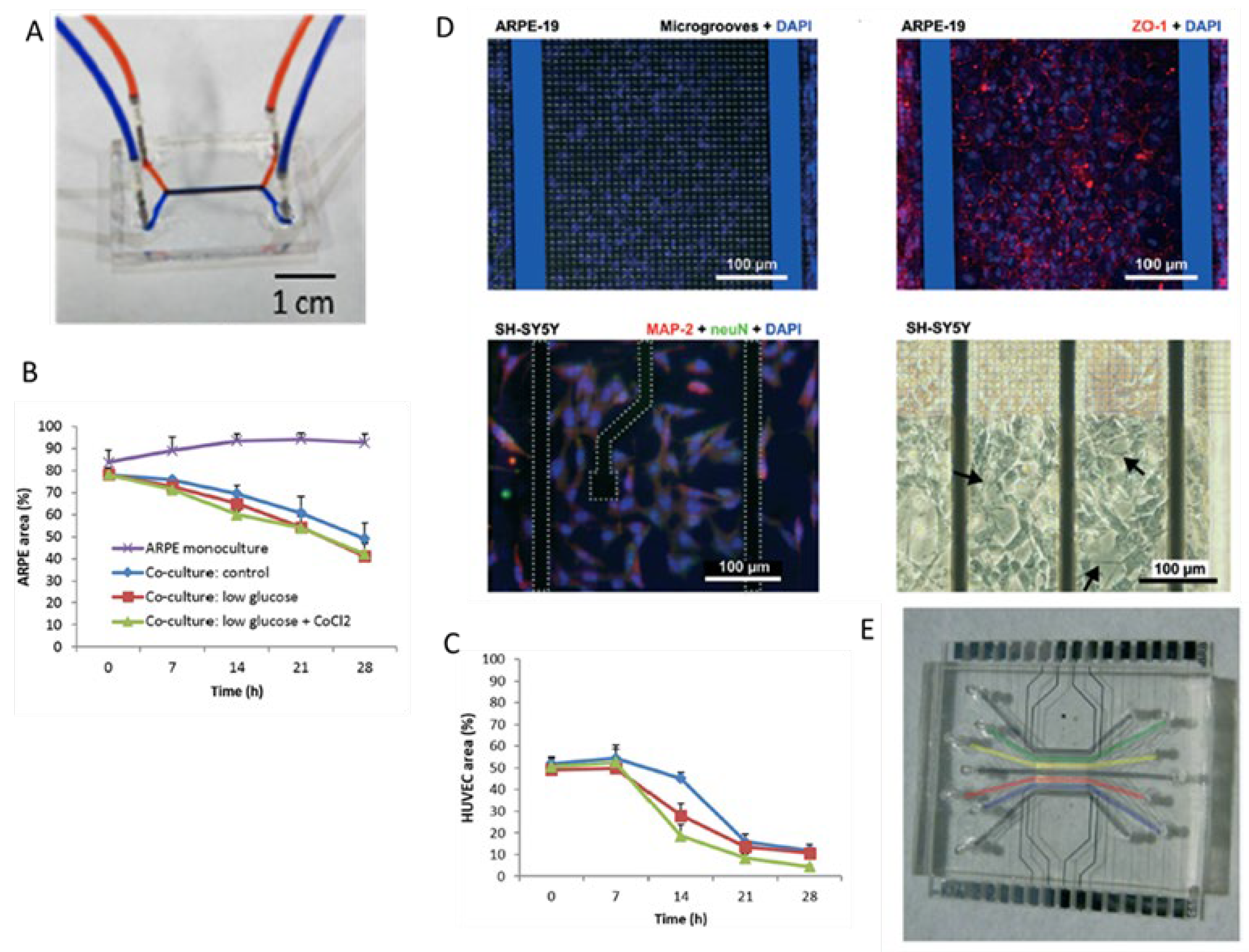

3. Blood-Retinal Barrier (BRB)-on-Chip

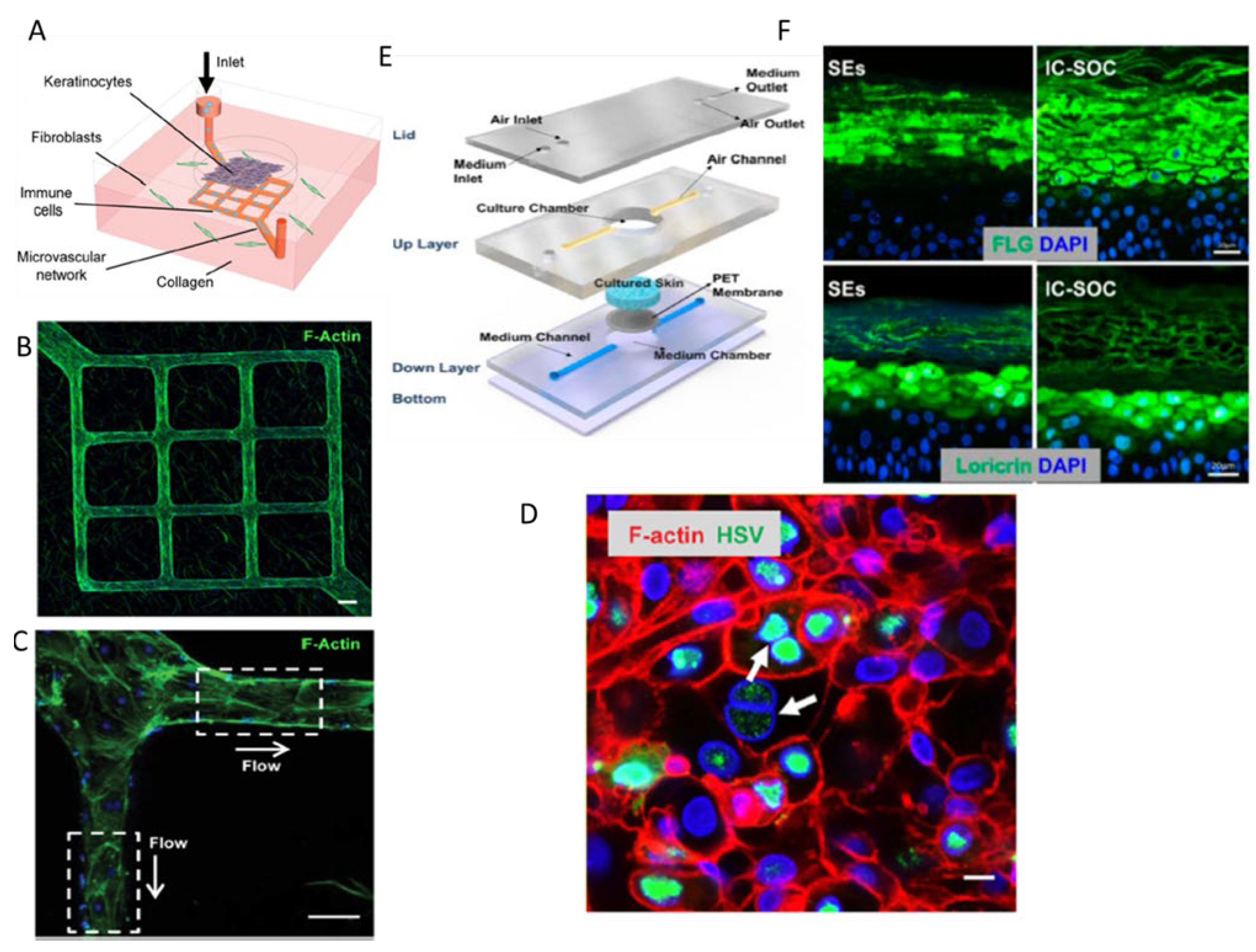

4. Skin-on-Chip

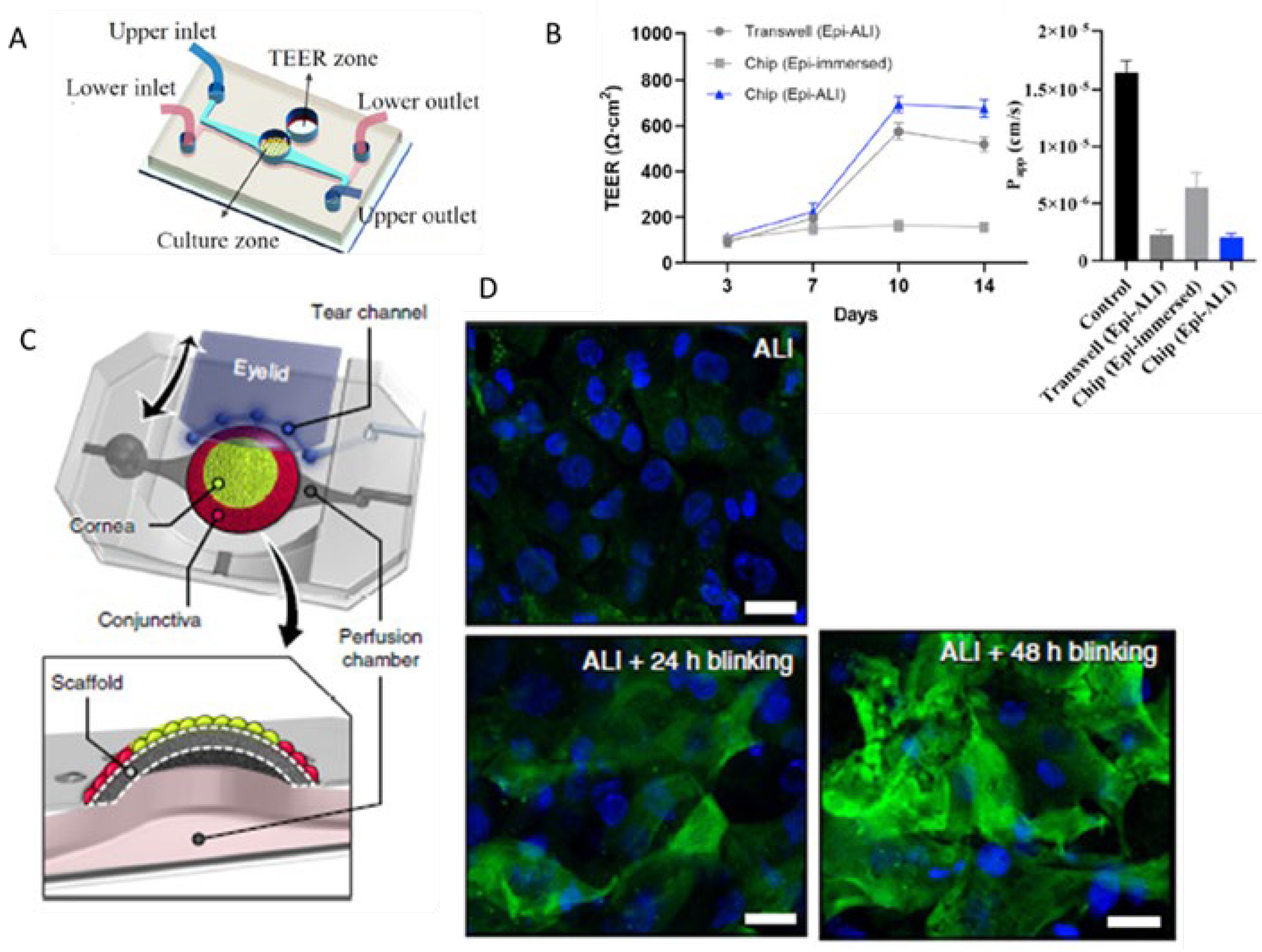

5. Cornea-on-Chip

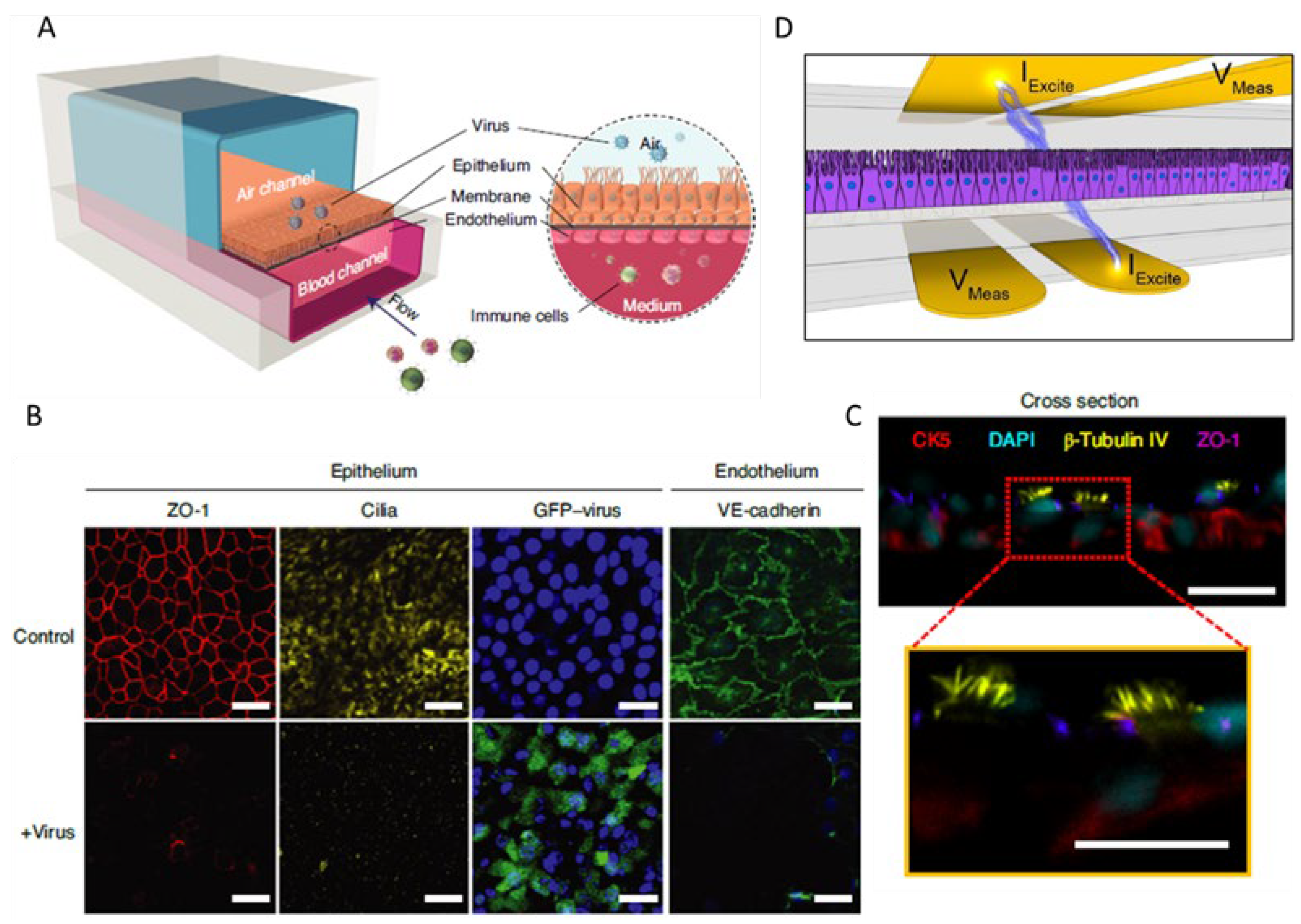

6. Airway-on-Chip

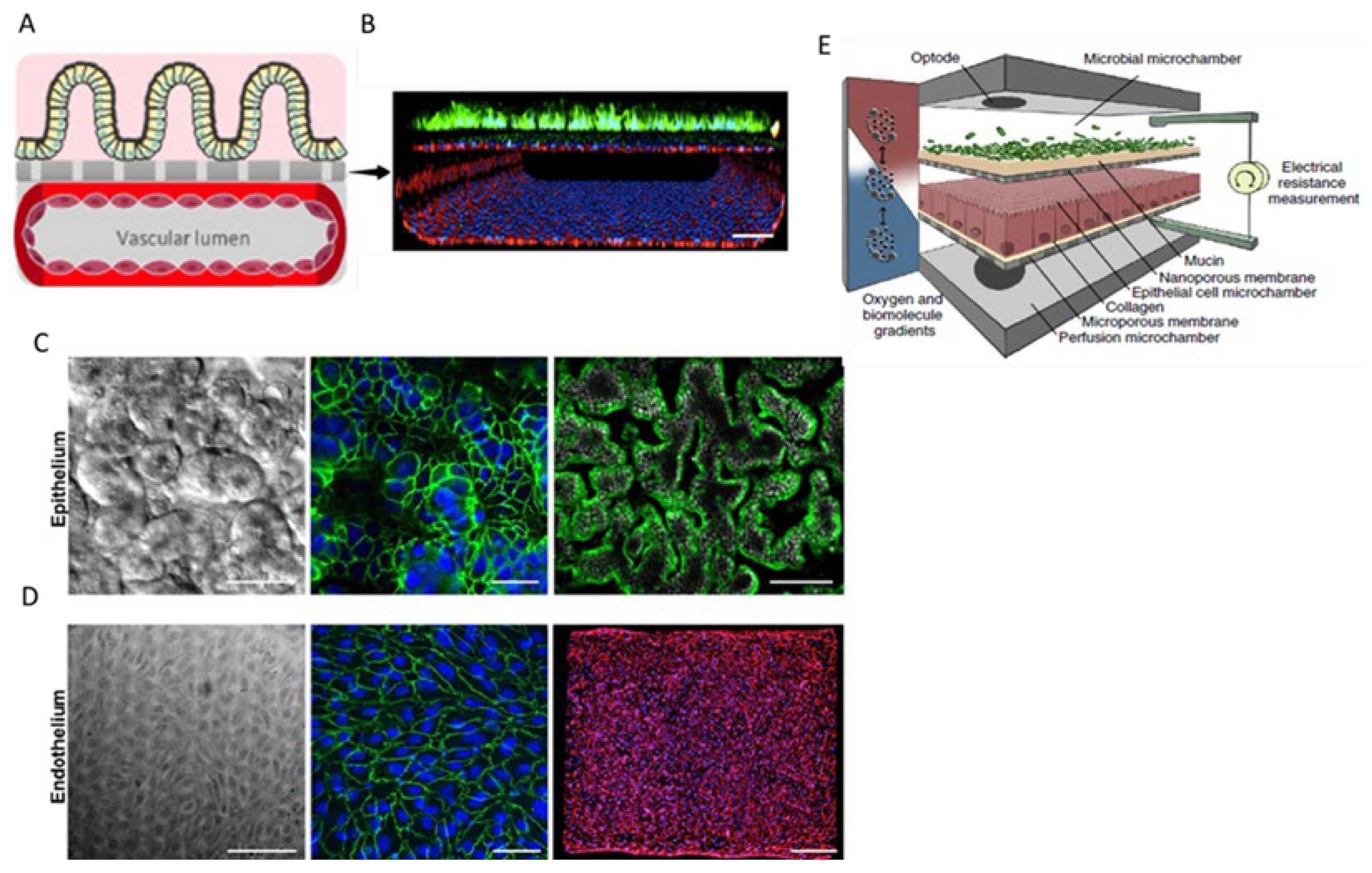

7. Gastrointestinal Barrier-on-Chip

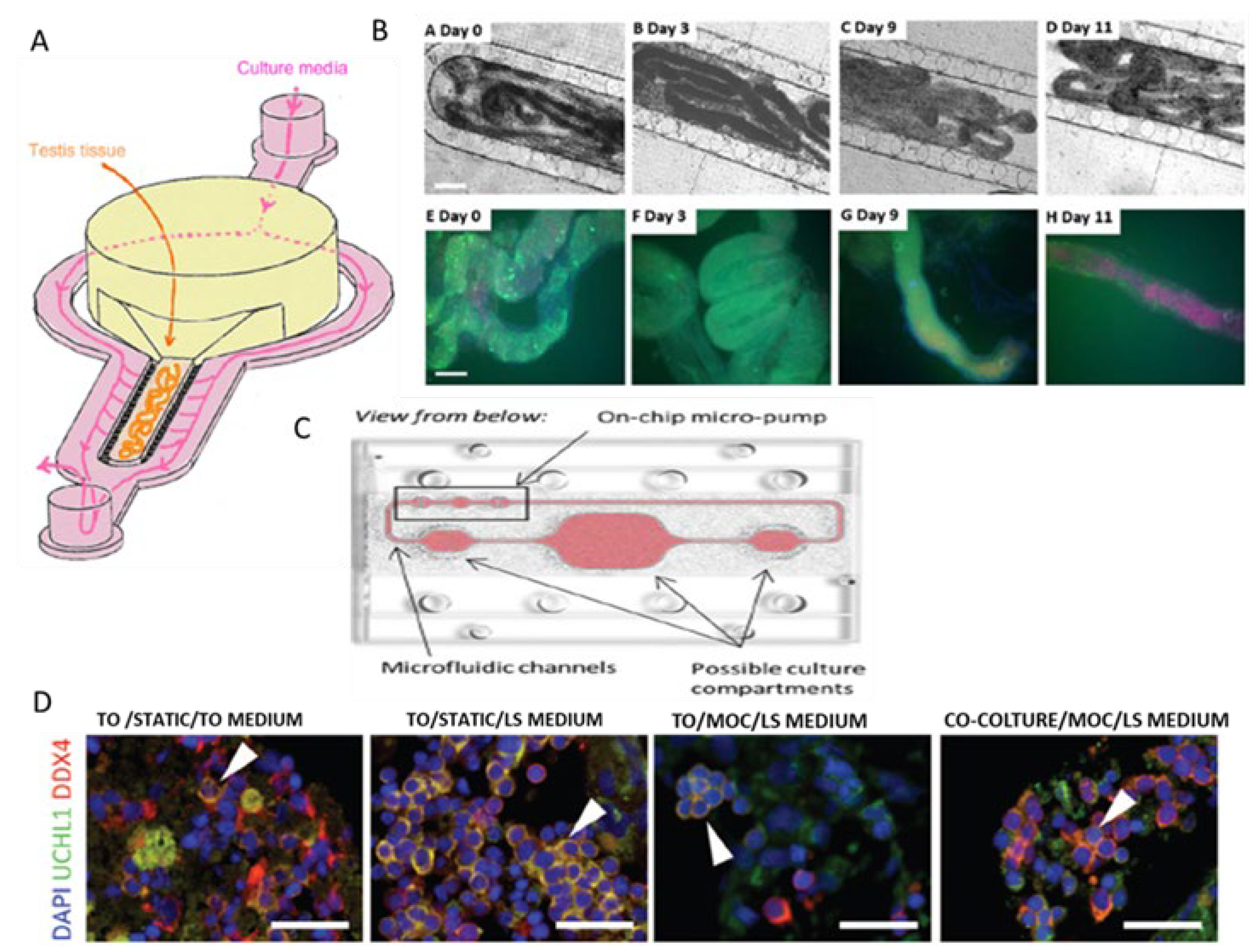

8. Testis-on-Chip

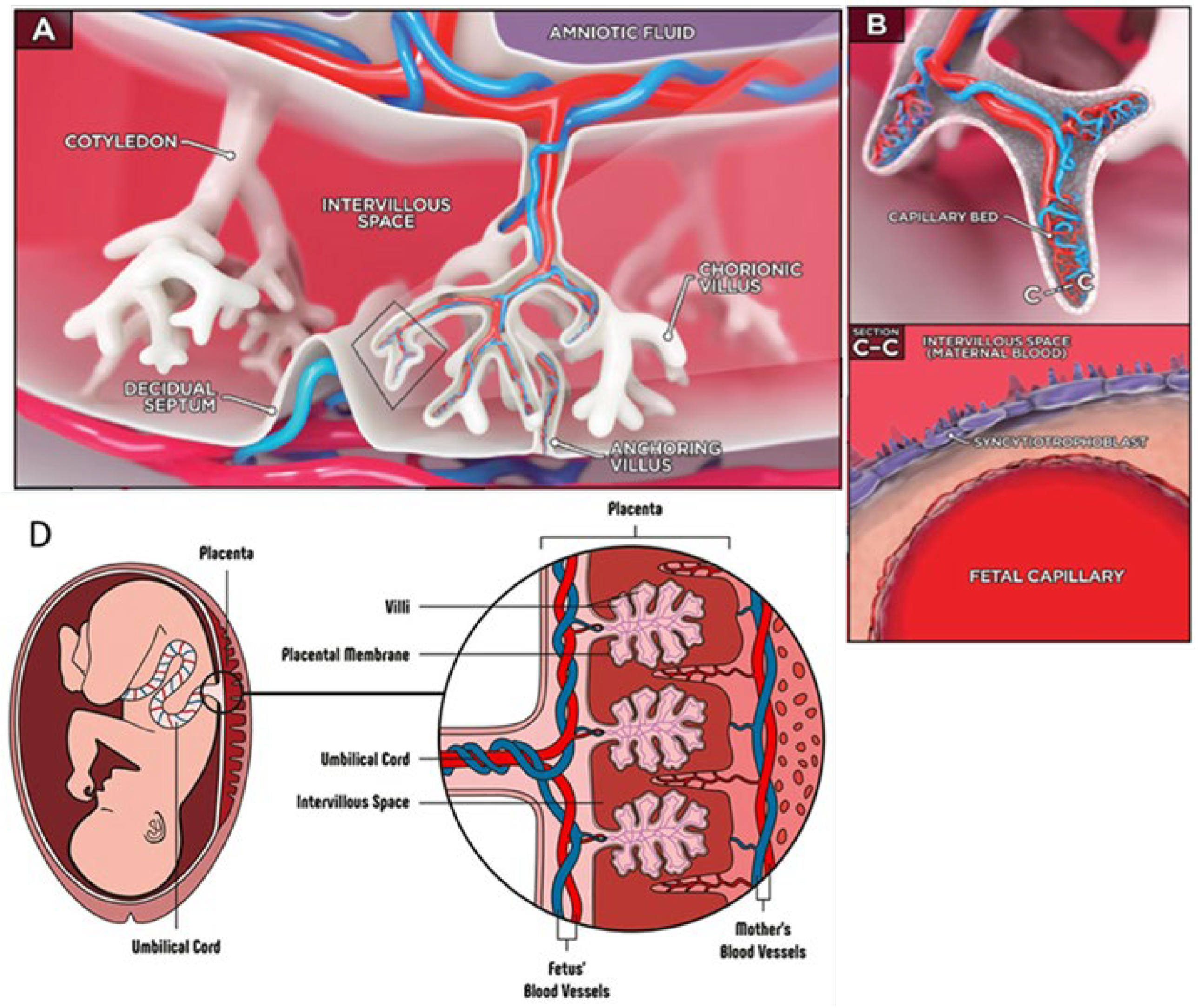

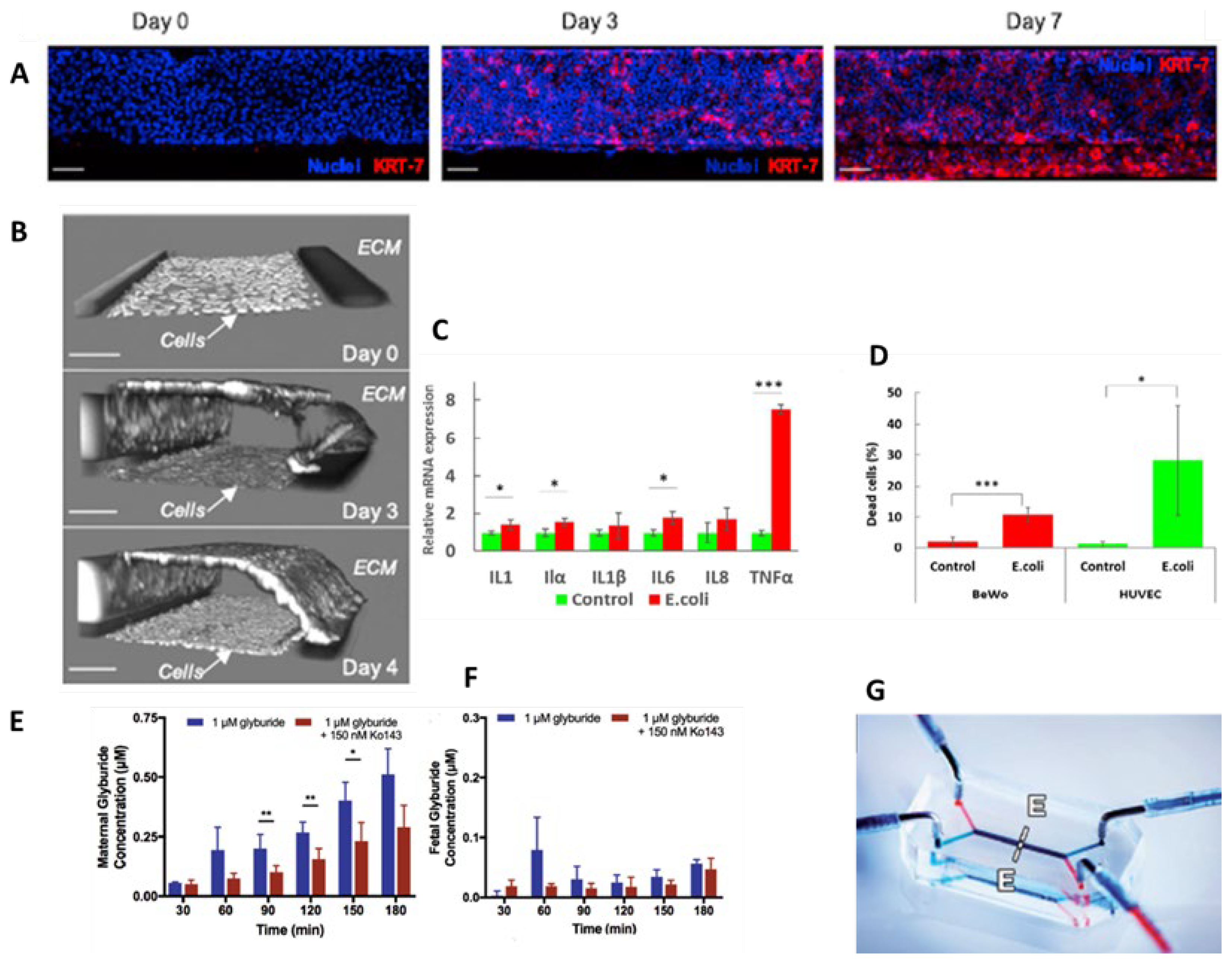

9. Placenta-on-Chip

| BARRIERS-ON-CHIP | KEY FEATURES | CRITICAL ISSUES | CELL LINES | PRECLINICAL APPLICATIONS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood–brain barrier-on-chip |

|

Endotelial cell: hCMEC/D3 Astrocytes Bovine pericytes. [17,18,19] |

Optimization of drug passage through the BBB for studies of neurodegenerative diseases and tumor. [15,16,17] | |

| Blood-retinal barrier-on-chip | Generate an endothelial and an epithelial compartment to simulate iBRB and oBRB, respectively. [20,21]

|

|||

| Skin-on-chip |

|

|

||

| Cornea-on-chip |

|

|||

| Airway-on-chip | ||||

| Gastrointestinal barrier-on chip | ||||

| Testis-on-chip |

|

|

||

| Placenta-on-chip |

10. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zoio, P.; Lopes-Ventura, S.; Oliva, A. Barrier-on-a-Chip with a Modular Architecture and Integrated Sensors for Real-Time Measurement of Biological Barrier Function. Micromachines 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arik, Y.B.; et al. Barriers-on-chips: Measurement of barrier function of tissues in organs-on-chips. Biomicrofluidics, 2018, 12, 042218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cary, C. ; Stapleton, Determinants and mechanisms of inorganic nanoparticle translocation across mammalian biological barriers. Arch Toxicol 2023, 97, 2111–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazari, H.; et al. Advances in TEER measurements of biological barriers in microphysiological systems. Biosens Bioelectron 2023, 234, 115355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.Y.; et al. Palmitoyl Acyltransferase Activity of ZDHHC13 Regulates Skin Barrier Development Partly by Controlling PADi3 and TGM1 Protein Stability. J Invest Dermatol 2020, 140, 959–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; et al. Zebrafish as a visual and dynamic model to study the transport of nanosized drug delivery systems across the biological barriers. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces, 2017, 156, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, L.A.; et al. Organs-on-chips: into the next decade. Nat Rev Drug Discov, 2021, 20, 345–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R, N.; et al. Organ-On-A-Chip: An Emerging Research Platform. Organogenesis, 2023, 19, 2278236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, C.M.; et al. A guide to the organ-on-a-chip. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers, 2022, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavrou, M.; et al. Organ-on-chip systems as a model for nanomedicine. Nanoscale, 2023, 15, 9927–9940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteduro, A.G.; et al. Organs-on-chips technologies - A guide from disease models to opportunities for drug development. Biosens Bioelectron, 2023, 231, 115271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahadian, S.; et al. Organ-On-A-Chip Platforms: A Convergence of Advanced Materials, Cells, and Microscale Technologies. Adv Healthc Mater, 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 10.1016/j.bios.2023.115271. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; et al. Sensors-integrated organ-on-a-chip for biomedical applications. Nano Res.

- Lucchetti, M.; et al. Integration of multiple flexible electrodes for real-time detection of barrier formation with spatial resolution in a gut-on-chip system. Microsyst Nanoeng, 2024, 10, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzreuter, M.A. and L.I. Segerink, Innovative electrode and chip designs for transendothelial electrical resistance measurements in organs-on-chips. Lab Chip.

- Bhatia, S.N. and D.E. Ingber, Microfluidic organs-on-chips. Nat Biotechnol, 2014, 32, 760–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palasantzas, V.; et al. iPSC-derived organ-on-a-chip models for personalized human genetics and pharmacogenomics studies. Trends Genet, 2023, 39, 268–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagadeesan, S.; et al. Generation of a Human iPSC-Based Blood-Brain Barrier Chip. J Vis Exp.

- Benam, K.H.; et al. Small airway-on-a-chip enables analysis of human lung inflammation and drug responses in vitro. Nat Methods, 2016, 13, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albani, M.D.P.e.D., S. Tomasoni, and R. Gatta. Cellule staminali pluripotenti indotte e Organ on Chip: cosa sono e come funziona la ricerca del futuro. 2023; Available from: https://www.marionegri.it/magazine/cellule-staminali-pluripotenti-indotte-e-organ-on-chip.

- Shi, Y.; et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell technology: a decade of progress. Nat Rev Drug Discov, 2017, 16, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, H. and S. Yamanaka, The use of induced pluripotent stem cells in drug development. Clin Pharmacol Ther, 2011, 89, 655–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lermant, A.; et al. Development of a human iPSC-derived placental barrier-on-chip model. iScience, 2023, 26, 107240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taggi, V.; et al. Transporter Regulation in Critical Protective Barriers: Focus on Brain and Placenta. Pharmaceutics.

- in ISTITUTO DELLA ENCICLOPEDIA ITALIANA FONDATA DA GIOVANNI TRECCANI S.P.A.

- Wu, D.; et al. The blood-brain barrier: structure, regulation, and drug delivery. Signal Transduct Target Ther, 2023, 8, p217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bi, W.; et al. Implementation of blood-brain barrier on microfluidic chip: Recent advance and future prospects. Ageing Res Rev, 2023, 87, 101921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guarino, V.; et al. Advancements in modelling human blood brain-barrier on a chip. Biofabrication.

- van der Helm, M.W.; et al. Microfluidic organ-on-chip technology for blood-brain barrier research. Tissue Barriers, 2016, 4, e1142493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, M.; et al. Biosensors Integration in Blood-Brain Barrier-on-a-Chip: Emerging Platform for Monitoring Neurodegenerative Diseases. ACS Sens, 2022, 7, 1237–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, B. and S.W. Cho, Blood-brain barrier-on-a-chip for brain disease modeling and drug testing. BMB Rep, 2022, 55, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badiola-Mateos, M.; et al. A novel multi-frequency trans-endothelial electrical resistance (MTEER) sensor array to monitor blood-brain barrier integrity. Sens. Actuators B: Chem. 2021, 334, 129599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; et al. A dynamic in vivo-like organotypic blood-brain barrier model to probe metastatic brain tumors. Sci Rep, 2016, 6, 36670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partyka, P.P.; et al. Mechanical stress regulates transport in a compliant 3D model of the blood-brain barrier. Biomaterials, 2017, 115, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, F. and M. Campbell, The blood-retina barrier in health and disease. FEBS J, 2023, 290, 878–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragelle, H.; et al. Organ-On-A-Chip Technologies for Advanced Blood-Retinal Barrier Models. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther, 2020, 36, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragelle, H.; et al. Human Retinal Microvasculature-on-a-Chip for Drug Discovery. Adv Healthc Mater, 2020, 9, e2001531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeste, J.; et al. A compartmentalized microfluidic chip with crisscross microgrooves and electrophysiological electrodes for modeling the blood-retinal barrier. Lab Chip, 2017, 18, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.J.; et al. Microfluidic co-cultures of retinal pigment epithelial cells and vascular endothelial cells to investigate choroidal angiogenesis. Sci Rep, 2017, 7, 3538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadi, M.H.; et al. Skin Diseases Modeling using Combined Tissue Engineering and Microfluidic Technologies. Adv Healthc Mater, 2016, 5, 2459–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, J.H. and J.J. Kim, Recent advances in in vitro skin-on-a-chip models for drug testing. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol, 2023, 19, 249–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J. and H.E. Abaci, Human skin-on-a-chip for mpox pathogenesis studies and preclinical drug evaluation. Trends Pharmacol Sci, 2023, 44, 865–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; et al. 3D skin models along with skin-on-a-chip systems: A critical review. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2023, 34, 107819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smythe, and H. N. Wilkinson, The Skin Microbiome: Current Landscape and Future Opportunities. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Townsend, E.C. and L.R. Kalan, The dynamic balance of the skin microbiome across the lifespan. Biochem Soc Trans 2023, 51, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Carro, E.; et al. Modeling an Optimal 3D Skin-on-Chip within Microfluidic Devices for Pharmacological Studies. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, Q.; et al. Analysis of drug efficacy for inflammatory skin on an organ-chip system. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2022, 10, 939629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, J.; et al. Modeling of three-dimensional innervated epidermal like-layer in a microfluidic chip-based coculture system. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, S.; et al. Modeling human HSV infection via a vascularized immune-competent skin-on-chip platform. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 5481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martorina, F.; et al. In vitro activation of the neuro-transduction mechanism in sensitive organotypic human skin model. Biomaterials, 2017, 113, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Meenen, J.; et al. An Overview of Advanced In Vitro Corneal Models: Implications for Pharmacological Testing. Tissue Eng Part B Rev 2022, 28, 506–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieto, K.; et al. Looking into the Eyes-In Vitro Models for Ocular Research. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kravchenko, S.V., V. V. Myasnikova, and S.N. Sakhnov, Application of the organ-on-a-chip technology in experimental ophthalmology. Vestn Oftalmol, 2023, 139, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; et al. Current microfluidic platforms for reverse engineering of cornea. Mater Today Bio 2023, 20, 100634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; et al. A Human Cornea-On-A-Chip. 2021, 982-985.

- Manafi, N.; et al. Organoids and organ chips in ophthalmology. Ocul Surf 2021, 19, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; et al. A human cornea-on-a-chip for the study of epithelial wound healing by extracellular vesicles. iScience 2022, 25, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.; et al. Multiscale reverse engineering of the human ocular surface. Nat Med 2019, 25, 1310–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dezube, R. , Panoramica sui sintomi delle patologie polmonari, 2023.

- Frey, A.; et al. More Than Just a Barrier: The Immune Functions of the Airway Epithelium in Asthma Pathogenesis. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sunil, A.A. and T. Skaria, Novel regulators of airway epithelial barrier function during inflammation: potential targets for drug repurposing. Expert Opin Ther Targets 2022, 26, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benam, K.H., M. Konigshoff, and O. Eickelberg, Breaking the In Vitro Barrier in Respiratory Medicine. Engineered Microphysiological Systems for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and Beyond. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2018, 197, 869–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S., H. Zhang, and X. Wang, Microfluidic-Chip-Integrated Biosensors for Lung Disease Models. Biosensors 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennet, T.J.; et al. Airway-On-A-Chip: Designs and Applications for Lung Repair and Disease. Cells 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; et al. Biomimetic human lung-on-a-chip for modeling disease investigation. Biomicrofluidics 2019, 13, 031501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, O.Y.F.; et al. Organs-on-chips with integrated electrodes for trans-epithelial electrical resistance (TEER) measurements of human epithelial barrier function. Lab Chip 2017, 17, 2264–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, M.A.U.; et al. A lung cancer-on-chip platform with integrated biosensors for physiological monitoring and toxicity assessment. Biochem. Eng. J. 2020, 155, 107469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, C.R.; et al. A High-Throughput, High-Containment Human Primary Epithelial Airway Organ-on-Chip Platform for SARS-CoV-2 Therapeutic Screening. Cells 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, L.; et al. A human-airway-on-a-chip for the rapid identification of candidate antiviral therapeutics and prophylactics. Nat Biomed Eng 2021, 5, 815–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; et al. Microfluidic strategies for biomimetic lung chip establishment and SARS-CoV2 study. Mater Today Bio 2024, 24, 100905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Tommaso, N., A. Gasbarrini, and F.R. Ponziani, Intestinal Barrier in Human Health and Disease. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Vincenzo, F.; et al. Gut microbiota, intestinal permeability, and systemic inflammation: a narrative review. Intern Emerg Med 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morelli, M.; et al. Gut-on-a-Chip Models: Current and Future Perspectives for Host-Microbial Interactions Research. Biomedicines 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trujillo-de Santiago, G.; et al. Gut-microbiota-on-a-chip: an enabling field for physiological research. Microphysiol Syst 2018, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, M.S.; et al. Contributions of the microbiome to intestinal inflammation in a gut-on-a-chip. Nano Converg 2022, 9, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; et al. The Gut-Organ-Axis Concept: Advances the Application of Gut-on-Chip Technology. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xian, C.; et al. Gut-on-a-chip for disease models. J Tissue Eng 2023, 14, 20417314221149882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; et al. Current gut-on-a-chip platforms for clarifying the interactions between diet, gut microbiota, and host health. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 134, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.P.; et al. Microfluidic Gut-on-a-Chip: Fundamentals and Challenges. Biosensors 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, H.J.; et al. Organoid-Based Human Stomach Micro-Physiological System to Recapitulate the Dynamic Mucosal Defense Mechanism. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2023, 10, e2300164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer, M.; et al. A three-dimensional immunocompetent intestine-on-chip model as in vitro platform for functional and microbial interaction studies. Biomaterials 2019, 220, 119396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Signore, M.A.; et al. Gut-on-Chip microphysiological systems: Latest advances in the integration of sensing strategies and adoption of mature detection mechanisms. Sens. Bio-Sens. Res. 2021, 33, 100443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, P.; et al. A microfluidics-based in vitro model of the gastrointestinal human-microbe interface. Nat Commun 2016, 7, 11535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; et al. Testis-on-chip platform to study ex vivo primate spermatogenesis and endocrine dynamics. Organs-on-a-Chip 2022, 4, 100023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ercan, F. and M. Acikel Elmas, The alterations of blood-testis barrier in experimental testicular ınjury models. Marmara Med. J.

- Su, J.; et al. Study of spermatogenic and Sertoli cells in the Hu sheep testes at different developmental stages. FASEB J 2023, 37, e23084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbuMadighem, A.; et al. Testis on a chip-a microfluidic three-dimensional culture system for the development of spermatogenesisin-vitro. Biofabrication 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baert, Y.; et al. A multi-organ-chip co-culture of liver and testis equivalents: a first step toward a systemic male reprotoxicity model. Hum Reprod 2020, 35, 1029–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arumugasaamy, N.; et al. Microphysiological systems of the placental barrier. Adv Drug Deliv Rev.

- Lee, J.S.; et al. Placenta-on-a-chip: a novel platform to study the biology of the human placenta. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2016, 29, 1046–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deval, G.; et al. On Placental Toxicology Studies and Cerium Dioxide Nanoparticles. Int J Mol Sci.

- Blundell, C.; et al. Placental Drug Transport-on-a-Chip: A Microengineered In Vitro Model of Transporter-Mediated Drug Efflux in the Human Placental Barrier. Adv Healthc Mater 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morganti, P. , The solved and unsolved mysteries of human life. J. Appl. Cosmetol. 2023, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, J.; et al. The Role of the 3Rs for Understanding and Modeling the Human Placenta. J Clin Med.

- Elzinga, F.A.; et al. Placenta-on-a-Chip as an In Vitro Approach to Evaluate the Physiological and Structural Characteristics of the Human Placental Barrier upon Drug Exposure: A Systematic Review. J Clin Med 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shojaei, S.; et al. Dynamic placenta-on-a-chip model for fetal risk assessment of nanoparticles intended to treat pregnancy-associated diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis, 2021, 1867, 166131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; et al. Placental Barrier-on-a-Chip: Modeling Placental Inflammatory Responses to Bacterial Infection. ACS Biomater Sci Eng, 2018, 4, 3356–3363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, R., A. Egurbide-Sifre, and L. Medina, Organ-on-a-Chip systems for new drugs development. ADMET DMPK, 2021, 9, 111–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitworth, C.P. and W.J. Polacheck, Vascular organs-on-chip made with patient-derived endothelial cells: technologies to transform drug discovery and disease modeling. Expert Opin Drug Discov.

Animal model

|

Cell culture 2D |

Cell culture 3D

|

Organ-on-chip

|

|

| Translatability of results | LOW | MEDIUM | HIGH | HIGH |

|

Ethical issues |

HIGH | LOW | LOW | LOW |

| Recapitulate disease model | MEDIUM | LOW | MEDIUM | HIGH |

| Drug discovery | MEDIUM | MEDIUM | HIGH |

HIGH |

| Biosensor equipment incorporation | LOW | HIGH | HIGH | HIGH |

| Cell-cell interaction | HIGH | LOW | HIGH | HIGH |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).