Submitted:

18 February 2025

Posted:

19 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

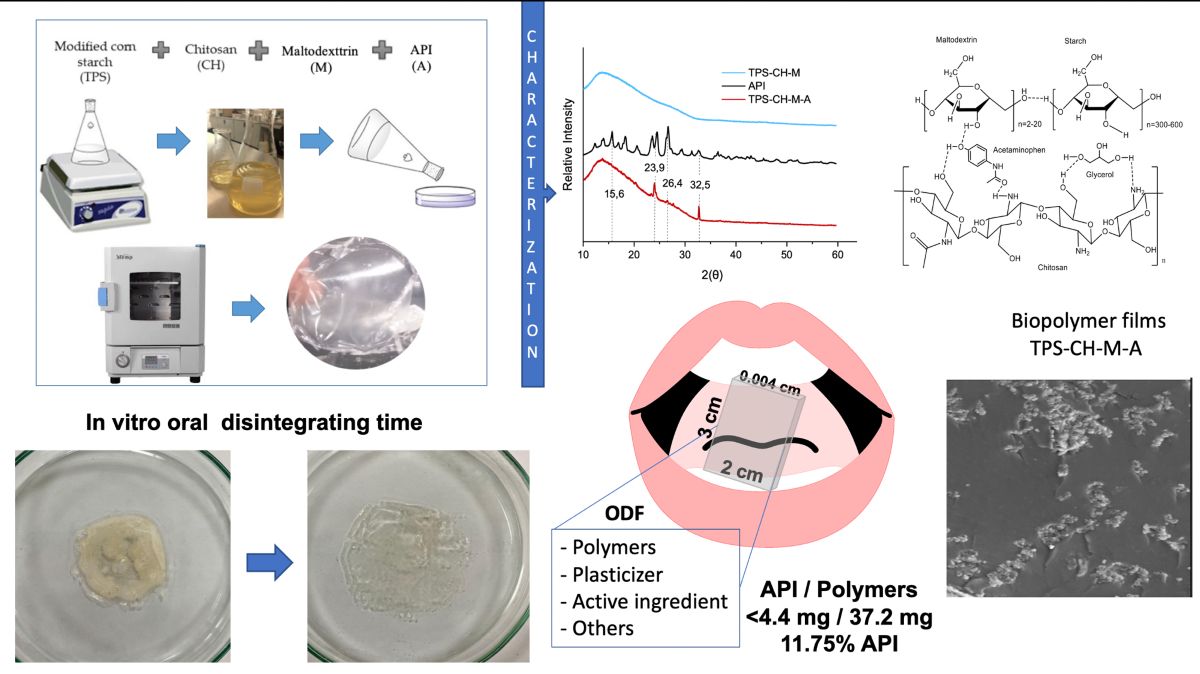

2.2. Preparation of Oral Disintegrating Films

2.2.1. Preparation of Film-Forming Solutions

2.2.2. Preparation of Biopolymeric Films

2.2.3. Preparation of Biopolymeric Films Containing a Pharmaceutical Ingredient

2.3. Characterization of Biopolymeric Films

2.3.1. Pharmaceutical Active Ingredient (API) Quantification

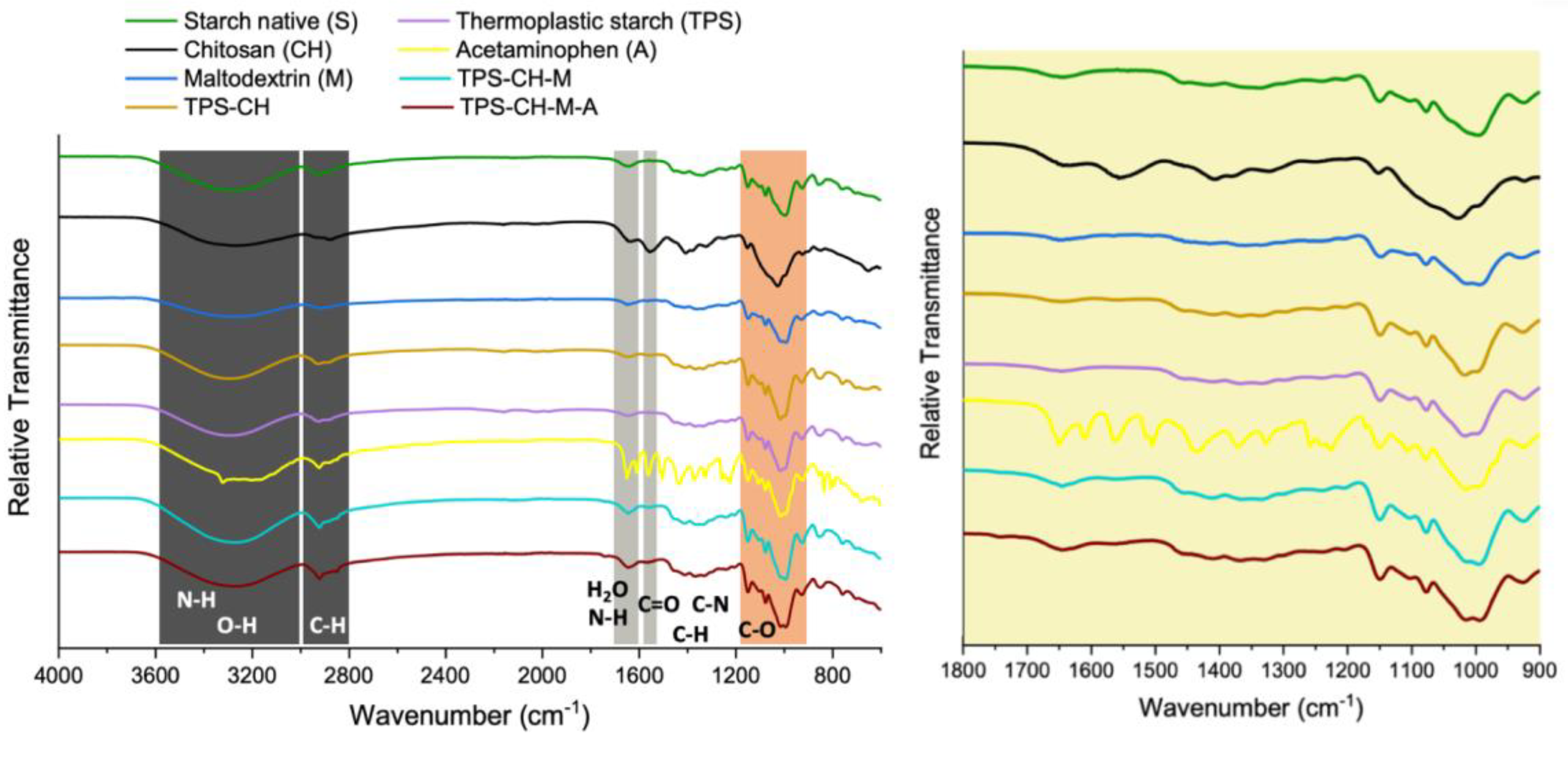

2.3.2. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

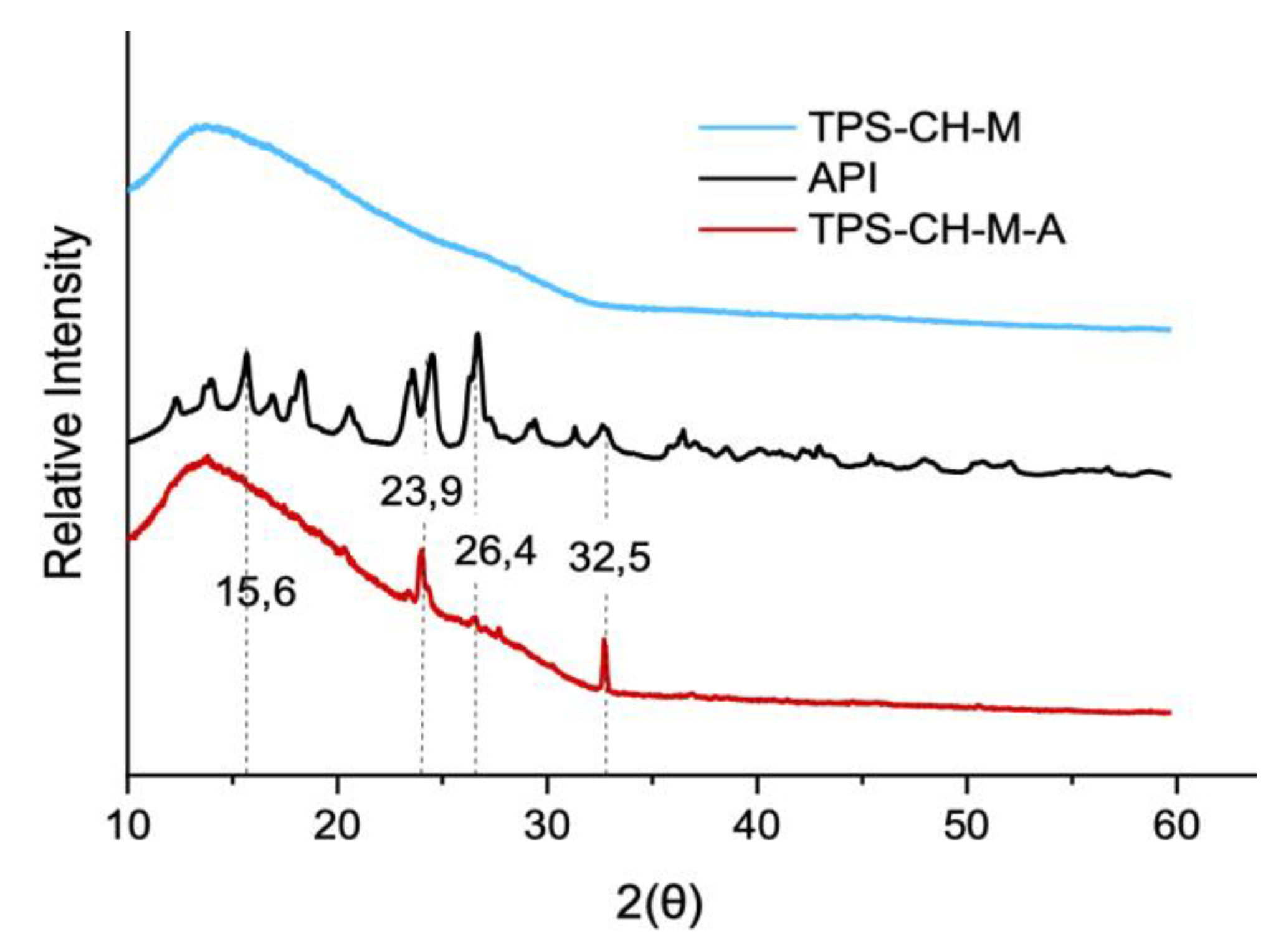

2.3.3. X-Ray Diffraction Analysis

2.3.4. Simultaneous Thermal Analysis: Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA), Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC).

2.3.5. Mechanical Tests

2.3.6. Scanning Electron Microscopy

2.3.7. Measurement of Sessile Drop

2.3.8. Absorption (Swelling) Test

2.3.9. Disintegration Time

In Vitro Oral Disintegrating Time

In Vitro Dissolution Time

Sugars Determination (°Brix)

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Quantification of the Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API)

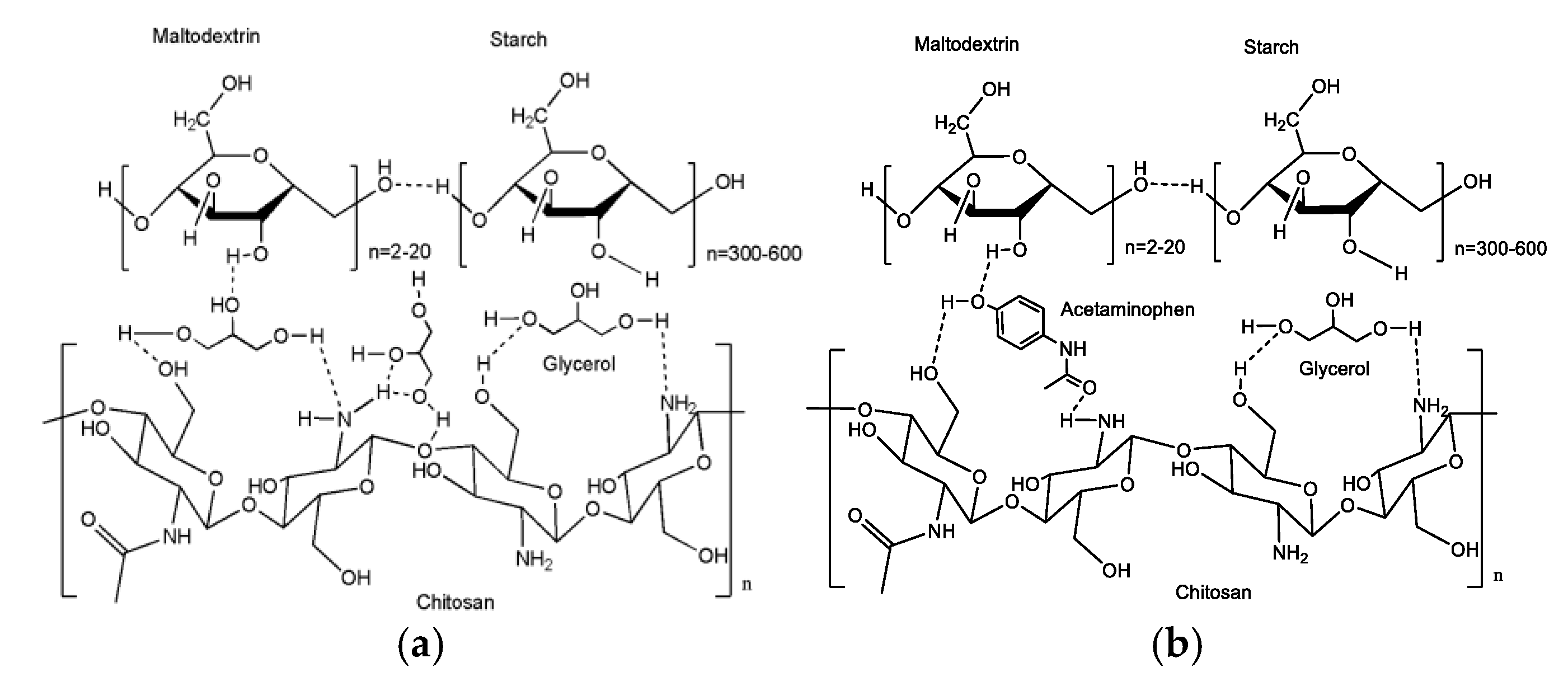

3.2. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy

3.3. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) Analysis

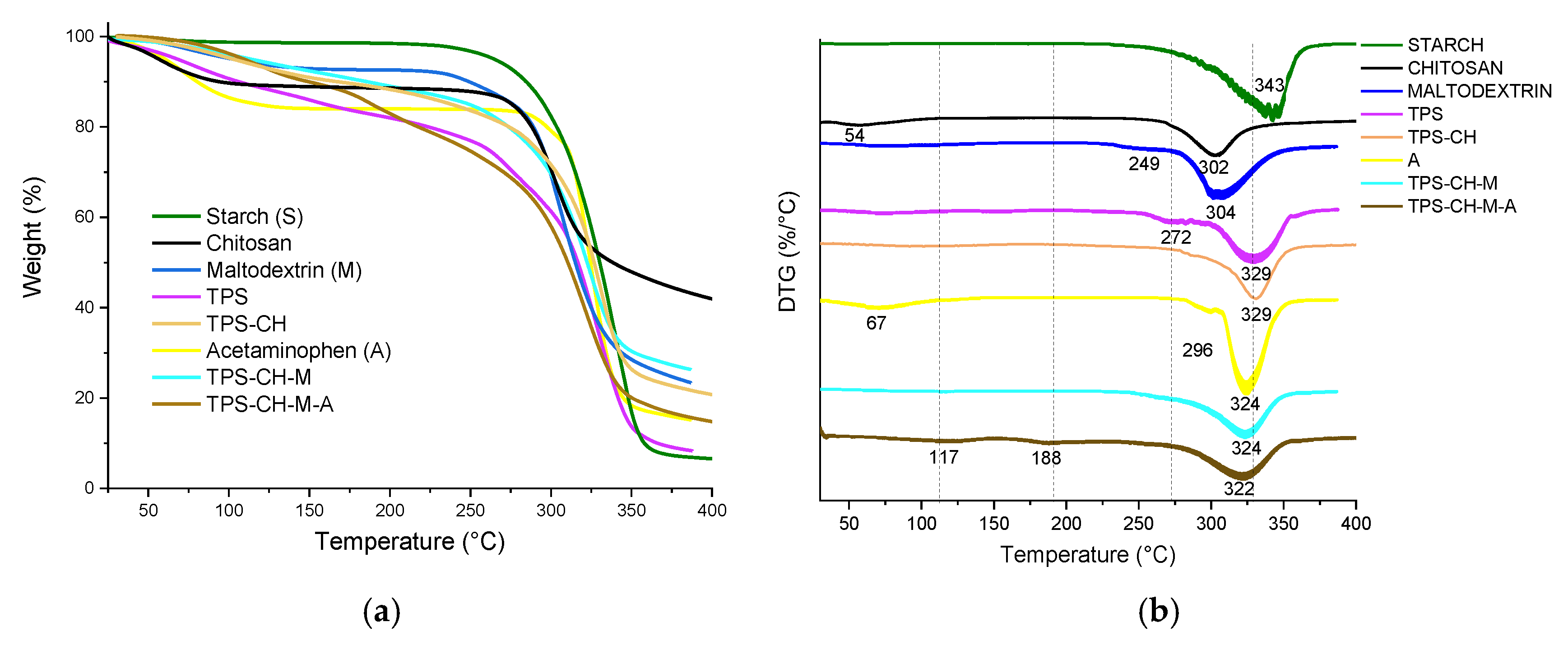

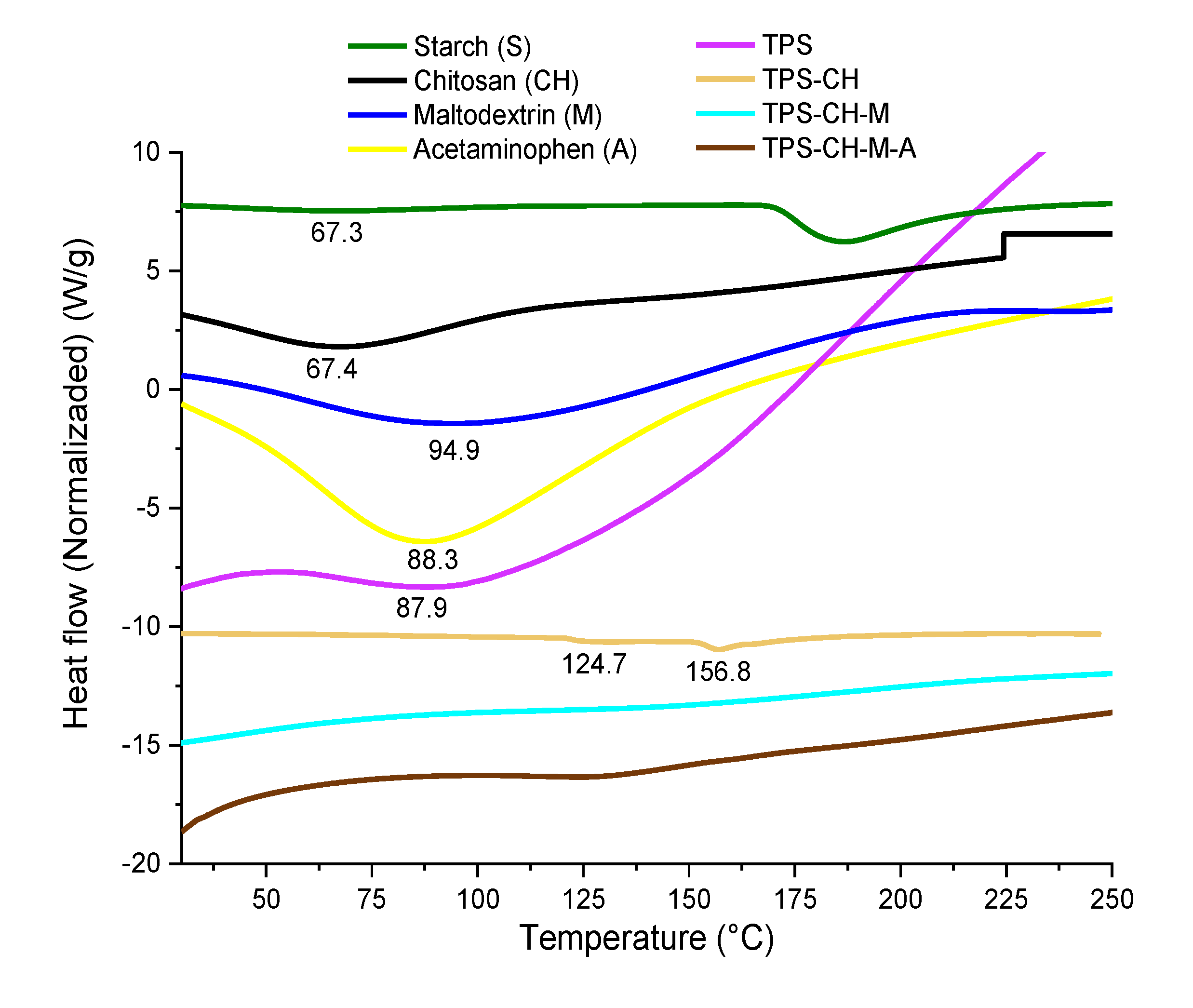

3.4. Simultaneous Thermal Analysis (TGA-DSC)

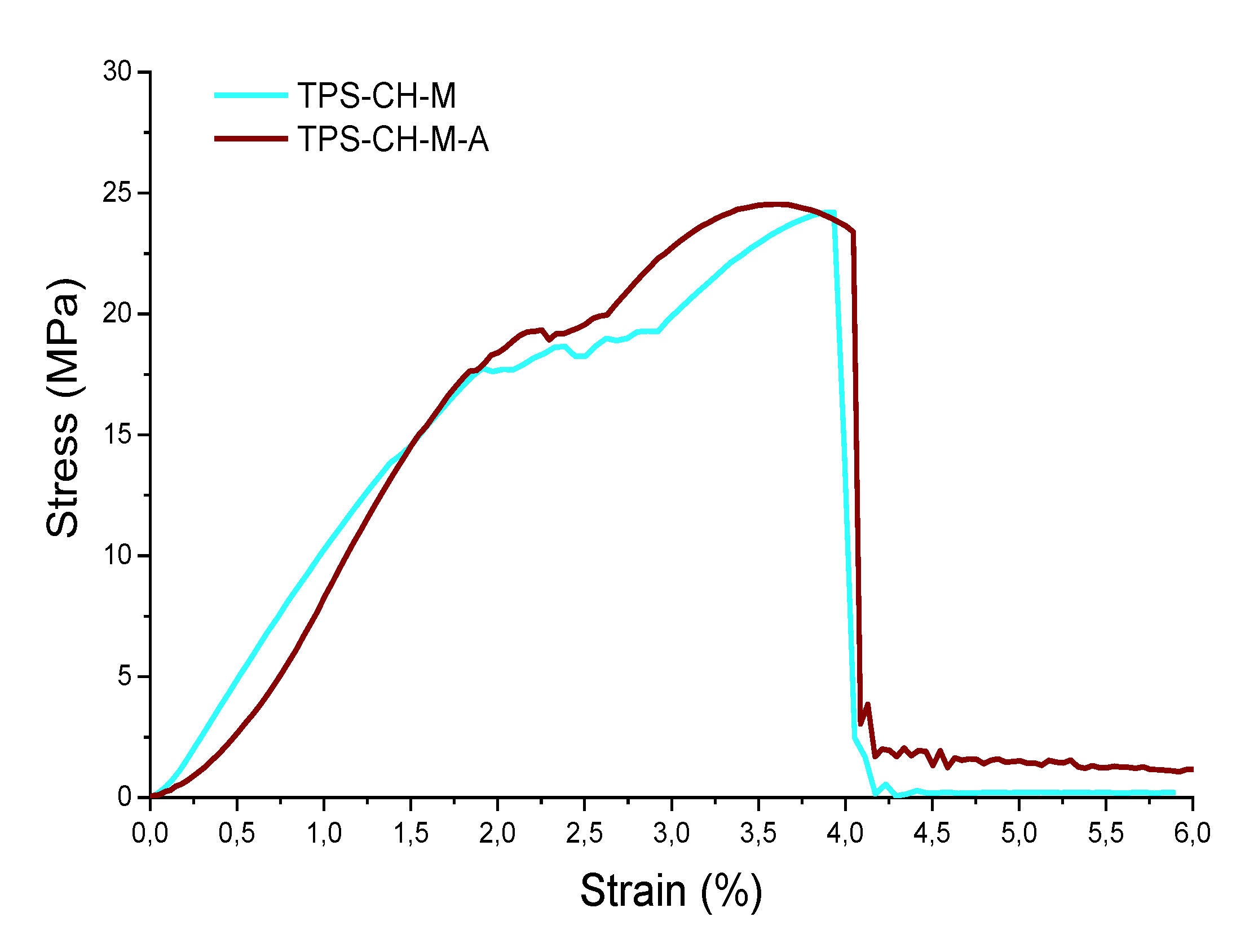

3.5. Mechanical Tests

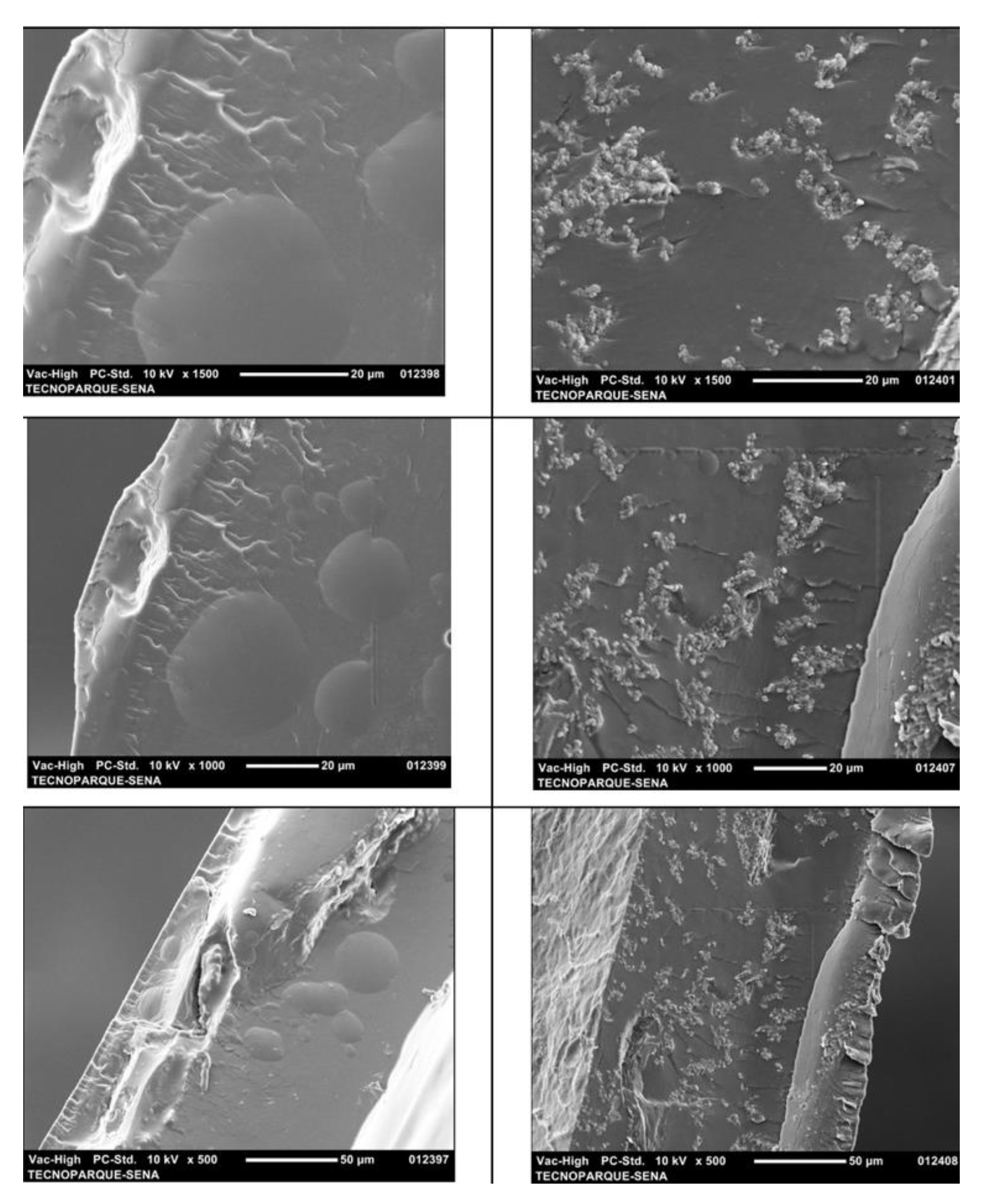

3.6. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

3.7. Contact Angle

3.8. In Vitro Disintegration Test

3.8.1. In Vitro Oral Disintegrating Time

3.8.2. In Vitro Dissolution Time

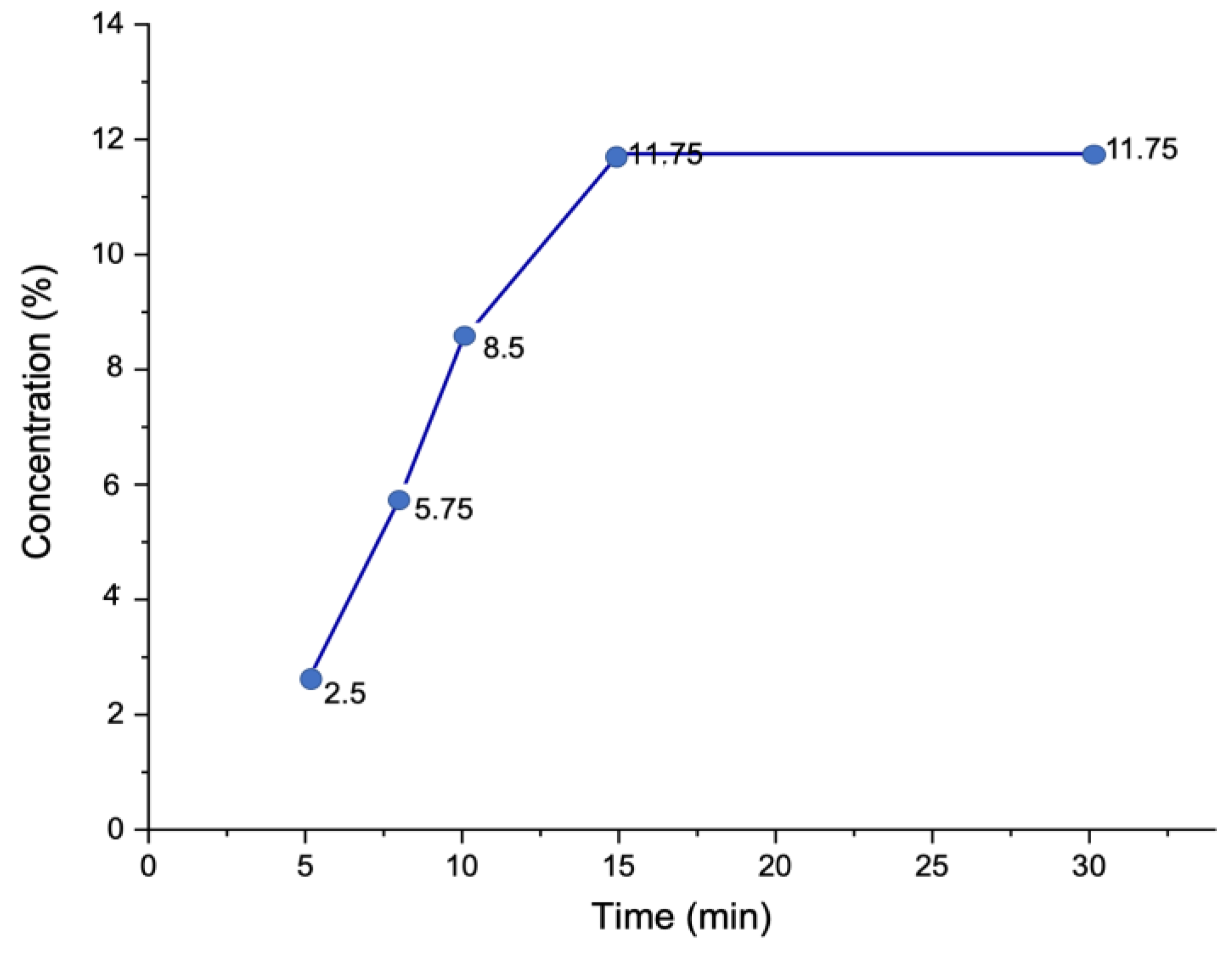

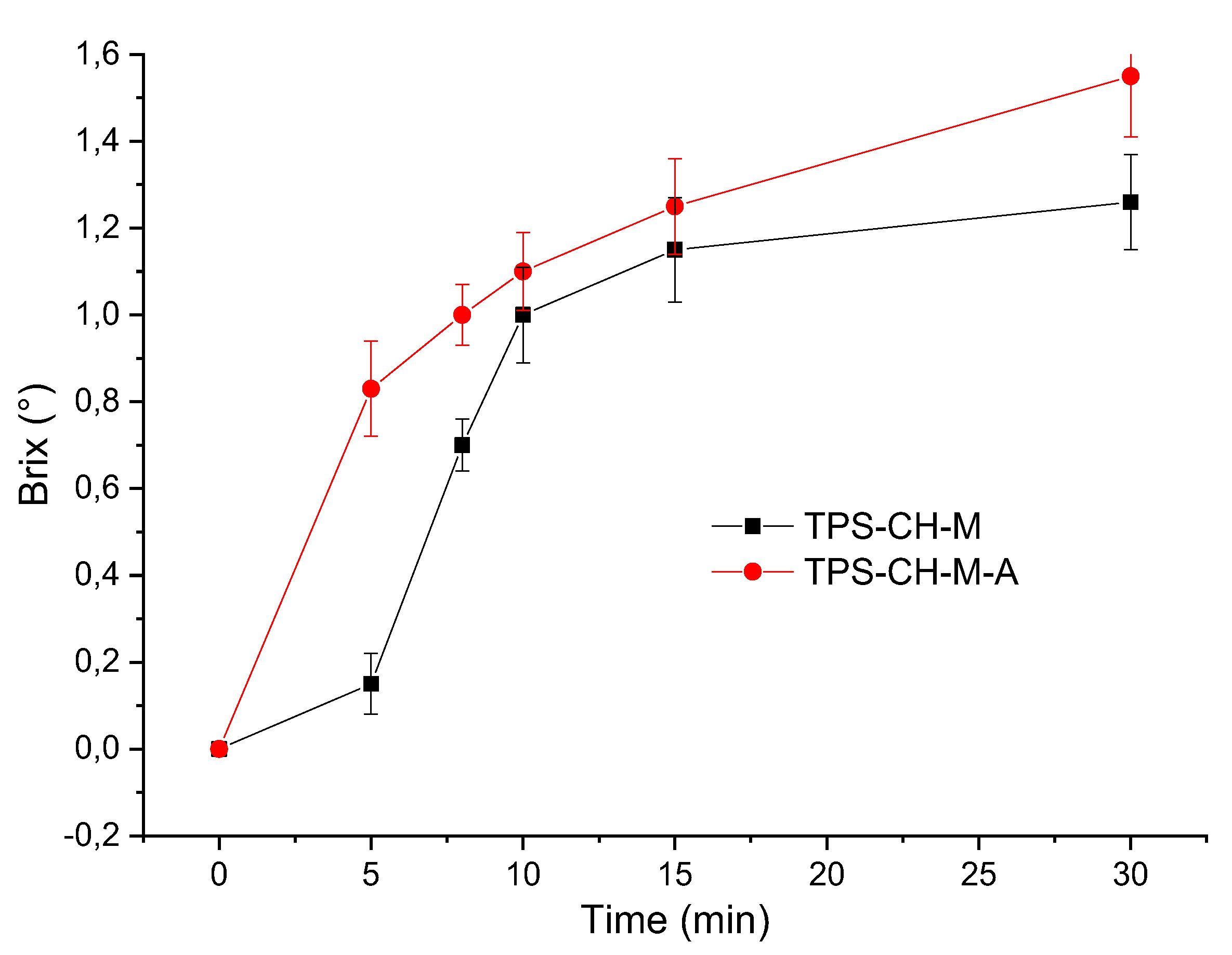

2.8.3. Total Soluble Solids (TSS)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pacheco, M.S.; Barbieri, D.; da Silva, C.F.; de Morales, M.A. A review on orally disintegrating films (ODFs) made from natural polymers such as pullulan, maltodextrin, starch, and others. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 178, 504–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariza-Galindo, C.J.; Rojas Aguilar, D.M. Disfagia en el adulto mayor. Univ. Med. 2020, 61, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turković, E.; Vasiljević, I.; Drašković, M.; Parojčić, J. Orodispersible films—Pharmaceutical development for improved performance: A review. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2022, 103708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos Garcia, V.A.; Borges, J.G.; Vanin, F.M.; de Carvalho, R.A. Orally disintegrating films of biopolymers for drug delivery. Biopolymer Membranes and Films 2020, 289–307. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, M.; Yan, C.; Liu, H.; Yu, D.G. Advances in the Application of Electrospun Drug-Loaded Nanofibers in the Treatment of Oral Ulcers. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alopaeus, J.F.; Hellfritzsch, M.; Gutowski, T.; Scherließ, R.; Almeida, A.; Sarmento, B.; Tho, I. Mucoadhesive buccal films based on a graft co-polymer–A mucin-retentive hydrogel scaffold. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 142, 105142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Zhu, L.; Yang, N.; Li, H.; Yang, Q. Recent advances of oral film as platform for drug delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 604, 120759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.X.; Kim, K.M.; Hanna, M.A.; Nag, D. Chitosan–starch composite film: preparation and characterization. Ind. Crops Prod. 2005, 21, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugstad, K.E.; Håti, A.G.; Nordgård, C.T.; Adl, P.S.; Maurstad, G.; Sletmoen, M.; Stokke, B.T. Direct determination of chitosan–mucin interactions using a single-molecule strategy: Comparison to alginate–mucin interactions. Polymers 2015, 7, 161–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Vale, D.A.; Vieira, C.B.; Vidal, M.F.; Claudino, R.L.; Andrade, F.K.; Sousa, J.R.; de Souza, B.W.S. Chitosan-Based Edible Films Produced from Crab-Uçá (Ucides cordatus) Waste: Physicochemical, Mechanical and Antimicrobial Properties J. Polym. Environ. 2021, 29, 694–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, A.; Fabra, M.J.; Talens, P.; Chiralt, A. Edible and Biodegradable Starch Films: A Review. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2012, 5, 2058–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.W.; Lee, B.H.; Kim, H.J.; Sriroth, K.; Dorgan, J.R. Thermal and mechanical properties of cassava and pineapple flours-filled PLA bio-composites. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2012, 108, 1131–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olomo, V.; Ajibola, O. Processing factors affecting the yield and physicochemical properties of starch from cassava chips and flour. Starch-Stärke 2003, 55, 476–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abera, B.; Duraisamy, R.; Birhanu, T. Study on the preparation and use of edible coating of fish scale chitosan and glycerol blended banana pseudostem starch for the preservation of apples, mangoes, and strawberries. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 15, 100916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barranco-García, J.E.; Caicedo, C.; Jiménez-Regalado, E.J.; Espinoza-González, C.; Morales, G.; Aguirre-Loredo, R.Y.; Fonseca-García, A. The potential of starch-chitosan blends with poloxamer for the preparation of microparticles by spray-drying. Particuology 2024, 89, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amalia, A.; Nining, N.; Dandi, M. Characterization of modified sorghum starch and its use as a film-forming polymer in orally dissolving film formulations with glycerol as a plasticizer. J. Res. Pharm. 2023, 27, 1855–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cupone, I.E.; Roselli, G.; Marra, F.; Riva, M.; Angeletti, S.; Dugo, L.; Giori, A.M. Orodispersible film based on maltodextrin: A convenient and suitable method for iron supplementation. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chranioti, C.; Tzia, C. Thermooxidative Stability of Fennel Oleoresin Microencapsulated in Blended Biopolymer Agents. J. Food Sci. 2014, 79, C1091–C1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chranioti, C.; Nikoloudaki, A.; Tzia, C. Saffron and beetroot extracts encapsulated in maltodextrin, gum Arabic, modified starch and chitosan: Incorporation in a chewing gum system. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 127, 252–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brune, K.; Renner, B.; Tiegs, G. Acetaminophen/paracetamol: A history of errors, failures and false decisions. Eur. J. Pain 2015, 19, 953–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acheampong, P.; Thomas, S.H. Determinants of hepatotoxicity after repeated supratherapeutic paracetamol ingestion: Systematic review of reported cases. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2016, 82, 923–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; Salim, M.; Barber, B.W.; Pham, A.C.; McDowell, A.; Boyd, B.J. Dissolution of pain-relief drugs: Does beverage choice matter? J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2024, 91, 105247. [Google Scholar]

- Skoog, D.A.; Holler, F.J.; Nieman, T.A. Principios de análisis instrumental, 5th ed.; McGraw-Hill: Madrid, 2001; pp. 614–633. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, S.Y.; Goh, C.F.; Lau, J.Y.; Tiew, Y.C.; Balakrishnan, T. Rice starch thin films as a potential buccal delivery system: Effect of plasticiser and drug loading on drug release profile. Int. J. Pharm. 2019, 562, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ASTM D882-12, Standard Test Method for Tensile Properties of Thin Plastic Sheeting; ASTM International.

- Kumar, S.; Madan, S.; Bariha, N.; Suresh, S. Swelling and shrinking behavior of modified starch biopolymer with iron oxide. Starch-Stärke 2021, 73, 2000108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, M.F.; Clark, A.H.; Adams, S. Swelling and Mechanical Properties of Biopolymer Hydrogels Containing Chitosan and Bovine Serum Albumin. Biomacromolecules 2006, 7, 2961–2970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garsuch, V.; Breitkreutz, J. Comparative investigations on different polymers for the preparation of fast-dissolving oral films. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2010, 62, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, H.; Taguchi, H.; Iida, K.; Danjo, K. Development of polymer film dosage forms of lidocaine for buccal administration: I. Penetration rate and release rate. J. Controlled Release 2001, 77, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helrich, K. Official Methods of Analysis of the Association of Official Analytical Chemists; Association of Official Analytical Chemists: 1990.

- Trivedi, M.; Patil, S.; Shettigar, H.; Bairwa, K.; Jana, S. Effect of biofield treatment on spectral properties of paracetamol and piroxicam. Chem. Sci. J. 2015, 3, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Sritham, E.; Gunasekaran, S. FTIR spectroscopic evaluation of sucrose-maltodextrin-sodium citrate bioglass. Food Hydrocolloids 2017, 70, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakili, M.; Rafatullah, M.; Salamatinia, B.; Abdullah, A.Z.; Ibrahim, M.H.; Tan, K.B.; Amouzgar, P. Application of chitosan and its derivatives as adsorbents for dye removal from water and wastewater: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 113, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, S.; Tabassum, A.; Muslim, S.; Nasreen, T.; Baradoke, A.; Kim, T.H.; Bilal, M. Effective assessment of biopolymer-based multifunctional sorbents for the remediation of environmentally hazardous contaminants from aqueous solutions. Chemosphere 2023, 329, 138552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonseca-García, A.; Osorio, B.H.; Aguirre-Loredo, R.Y.; Calambas, H.L.; Caicedo, C. Miscibility study of thermoplastic starch/polylactic acid blends: Thermal and superficial properties. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 293, 119744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B.; Li, P.; Yang, R.; Li, A.; Yang, H. Investigation of multiple adsorption mechanisms for efficient removal of ofloxacin from water using lignin-based adsorbents. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jendrzejewska, I.; Goryczka, T.; Pietrasik, E.; Klimontko, J.; Jampilek, J. X-ray and Thermal Analysis of Selected Drugs Containing Acetaminophen. Molecules 2020, 25, 5909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrin, M.A.; Neumann, M.A.; Elmaleh, H.; Zaske, L. Crystal structure determination of the elusive paracetamol Form III. Chem. Commun. 2009, 22, 3181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, D.J.; Rostami, S. The miscibility of high polymers: The role of specific interactions. In Key Polymers Properties and Performance; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2005; pp. 119–169. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, B.Y.; Kong, J.; Xu, Y.; Yung, K.L.; Cai, A. Polymer nanowire arrays with high thermal conductivity and superhydrophobicity fabricated by a nano-molding technique. Heat Transfer Eng. 2013, 34, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino, D.; Gutiérrez, T.J.; Alvarez, V.A. Potential Agricultural Mulch Films Based on Native and Phosphorylated Corn Starch With and Without Surface Functionalization with Chitosan. J. Polym. Environ. 2019, 27, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacchetti, M. Thermodynamic Analysis of DSC Data for Acetaminophen Polymorphs. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2000, 63, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashpa, P.; Bijudas, K.; Tom, A.M.; Archana, P.K.; Murshida, K.P.; Banu, K.N.; Vimisha, K. A paracetamol-poly (3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) composite film for drug release studies. Int. J. Chem. Stud. 2014, 1, 25–29. [Google Scholar]

- Awasthi, S.; Singhal, R. A study on interaction and solubility of acetaminophen with poly (AM-co-HEA-co-AA) hydrogels by DSC: Effect on drug diffusion behavior. J. Macromol. Sci., Part A 2013, 50, 72–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, J.F.; Paschoalin, R.T.; Carmona, V.B.; Neto, A.R.S.; Marques, A.C.P.; Marconcini, J.M.; Oliveira, J.E. Biodegradable polymer blends based on corn starch and thermoplastic chitosan processed by extrusion. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 137, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.K.; Kim, J.K.; Jeong, O.C. Measurement of nonlinear mechanical properties of PDMS elastomer. Microelectron. Eng. 2011, 88, 1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre-Loredo, R.Y.; Fonseca-García, A.; Calambas, H.L.; Salazar-Arango, A.; Caicedo, C. Improvements of thermal and mechanical properties of achira starch/chitosan/clay nanocomposite films. Heliyon 2023, 9, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Cao, X.; Feng, X.; Ma, Y.; Zou, H. Fabrication of super-hydrophobic film from PMMA with intrinsic water contact angle below 90. Polymer 2007, 48, 7455–7460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panraksa, P.; Tipduangta, P.; Jantanasakulwong, K.; Jantrawut, P. Formulation of orally disintegrating films as an amorphous solid solution of a poorly water-soluble drug. Membranes 2020, 10, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Yu, B.; Yuan, C.; Guo, L.; Liu, P.; Gao, W.; Li, D.; Cui, B.; Abd El-Aty, A.M. An overview on plasticized biodegradable corn starch-based films: The physicochemical properties and gelatinization process. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 2569–2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Jing, Y. Study on the barrier properties of glycerol to chitosan coating layer. Mater. Lett. 2017, 209, 345–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Runge, T.; Wang, L.; Li, R.; Feng, J.; Shu, X.L.; Shi, Q.S. Hydrogen bonding impact on chitosan plasticization. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 200, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garsuch, V.; Breitkreutz, J. Novel analytical methods for the characterization of oral wafers. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2009, 73, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garsuch, V.; Breitkreutz, J. Comparative investigations on different polymers for the preparation of fast-dissolving oral films. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2010, 62, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Setouhy, D.A.; El-Malak, N.S.A. Formulation of a novel tianeptine sodium orodispersible film. AAPS Pharmscitech 2010, 11, 1018–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pechová, V.; Gajdziok, J.; Muselík, J.; Vetchý, D. Development of orodispersible films containing benzydamine hydrochloride using a modified solvent casting method. AAPS Pharmscitech 2018, 19, 2509–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Pharmacopoeia Commission. European Pharmacopoeia, 7th ed.; European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines (EDQM): Strasbourg, France, 2012; pp. 4257–4259. [Google Scholar]

- Onkov, K.Z.; Kassamakov, I.V. Computer models for adjustment of fiber-optic refractometers for concentration measurement of sugar solutions. Comput. Ind. 1993, 21, 279–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Tian, C.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, S.; Wang, X.; Chen, W.; Han, Y.; Du, Y.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, K. Dynamic changes of starch properties, sweetness, and β-amylases during the development of sweet potato storage roots. Food Biosci. 2024, 104964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.Z.; Nupur, A.H.; Habiba, U.; Robin, M.A.; Akash, S.I.; Rawdkuen, S.; Mazumder, M.A.R. Incorporation of orange peel polyphenols in buttermilk, maltodextrin and gum acacia suspension improve its stability. Food Hum. 2023, 1, 1345–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mechanical properties | ODF Pristine | ODF with API |

| E (MPa) | 9.27 | 9.38 |

| Yield point (MPa) | 17.76 | 17.67 |

| Tensile strength Yield (MPa) | 24.21 | 24.54 |

| Breaking point (MPa) | 24.21 | 23.39 |

| Resilience (MPa) | 17.84 | 15.04 |

| Tenacity (MPa) | 61.28 | 66.01 |

| Sample | Contact angle (°) and picture | AW (%) | |

| TPS-CH-M | 62.18 ± 0.12 |  |

321.28 ± 2.85 |

| TPS-CH-M-A | 62.91 ± 0.03 |  |

410.52 ± 3.03 |

| Sample | Time (min) | |||||

| 0 | 5 | 8 | 10 | 15 | 30 | |

| TPS-CH-M |  |

|

|

|

|

|

| TPS-CH-M-A |  |

|

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).