Submitted:

18 February 2025

Posted:

19 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

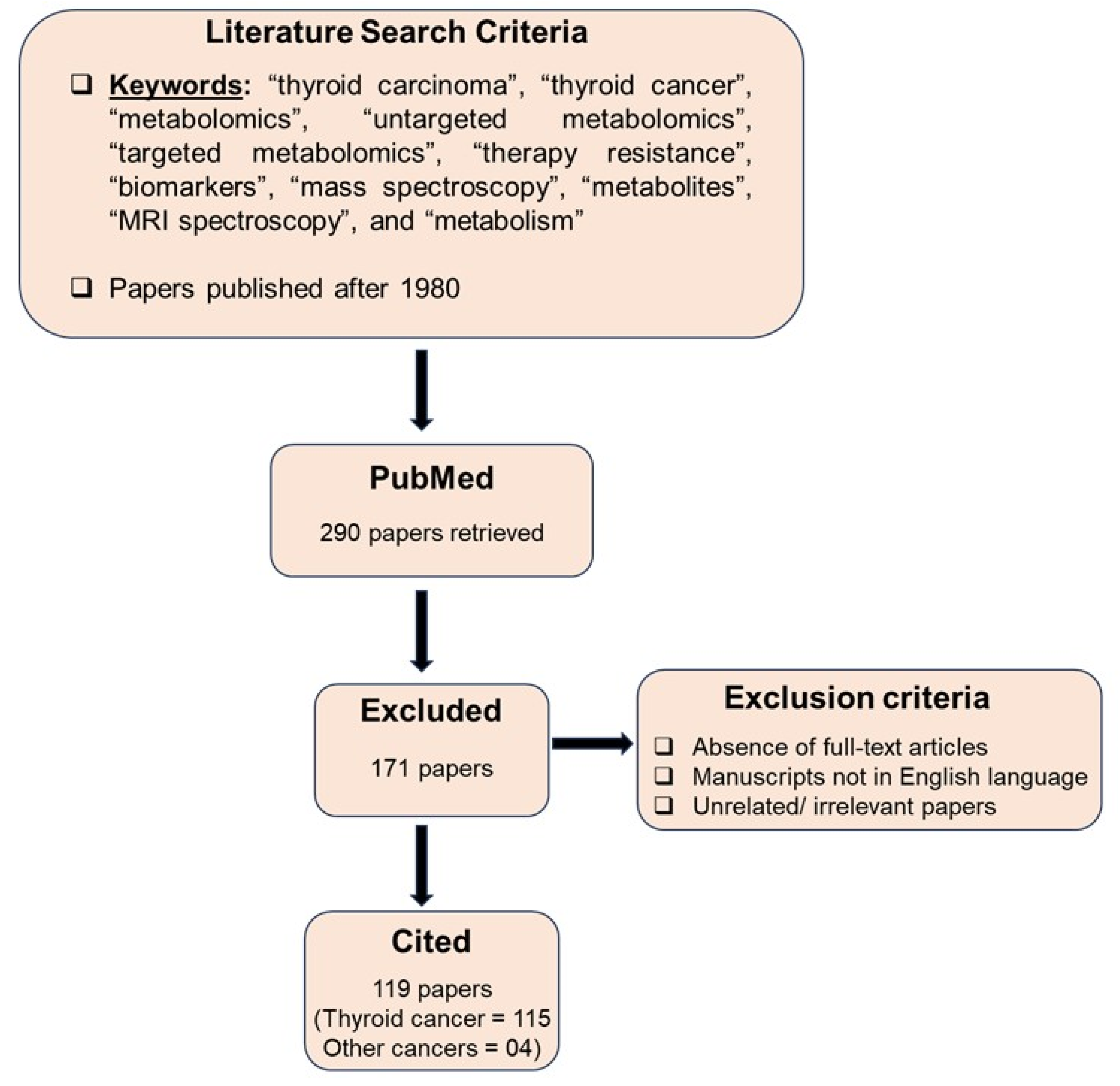

2. Search Strategy

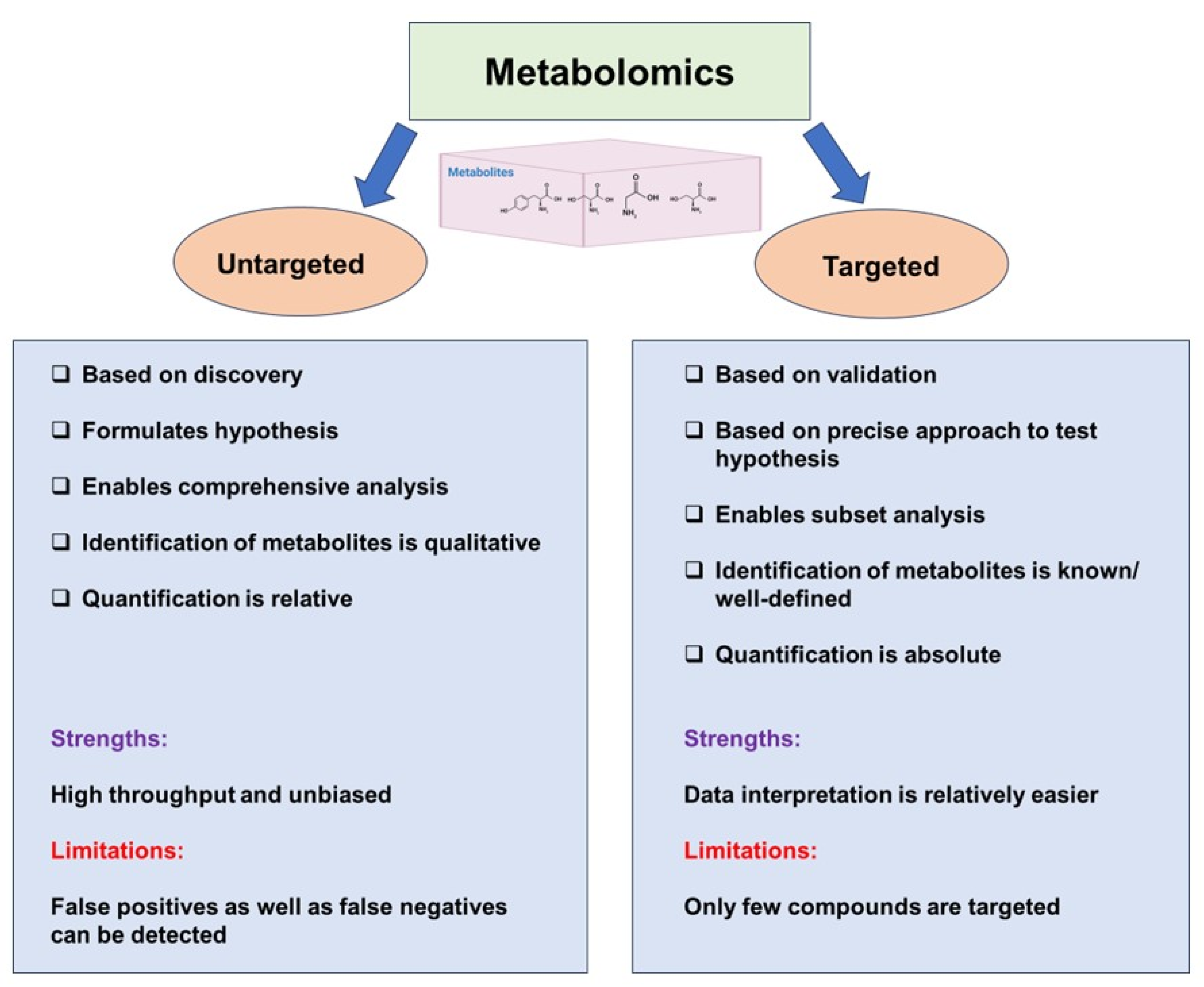

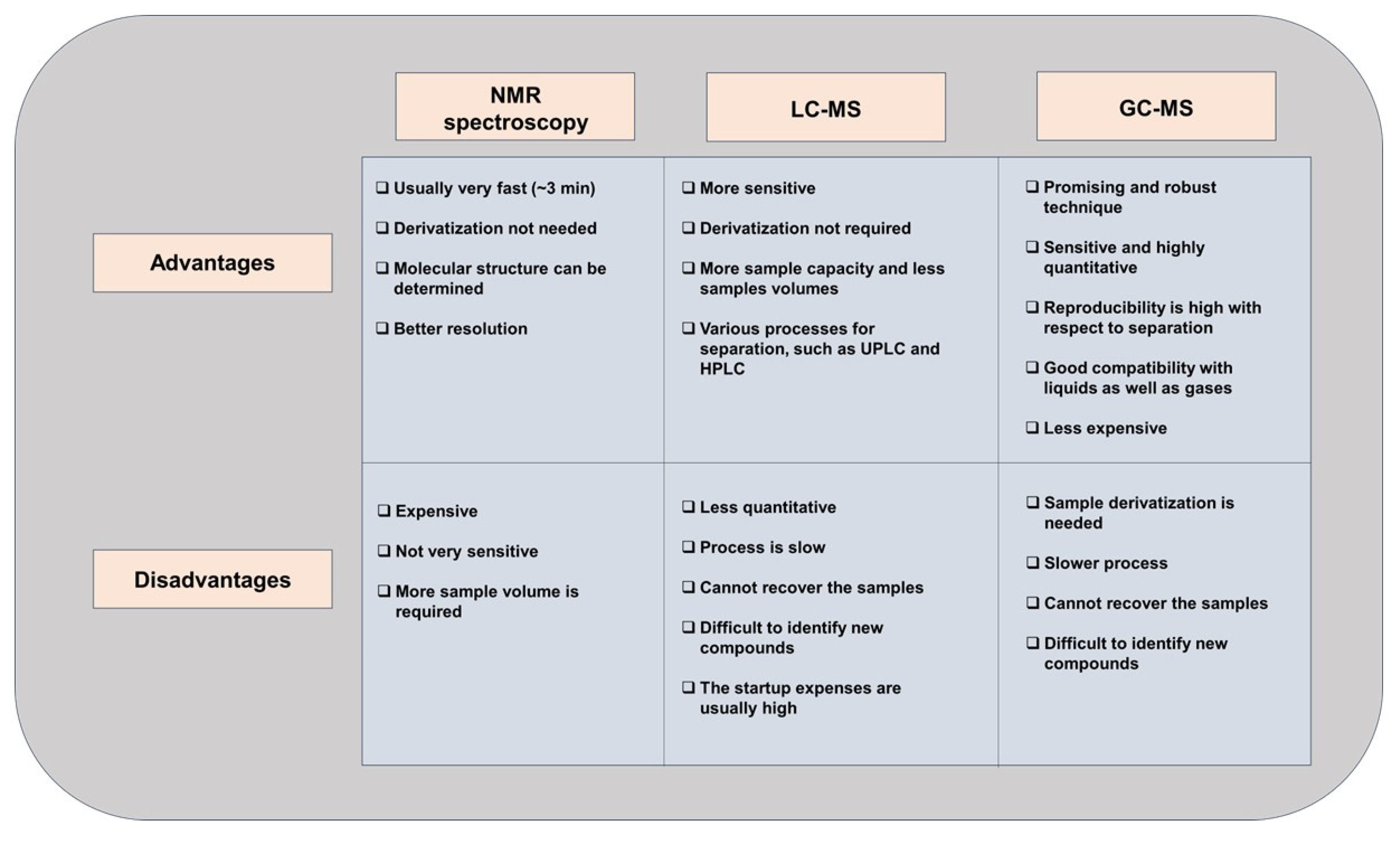

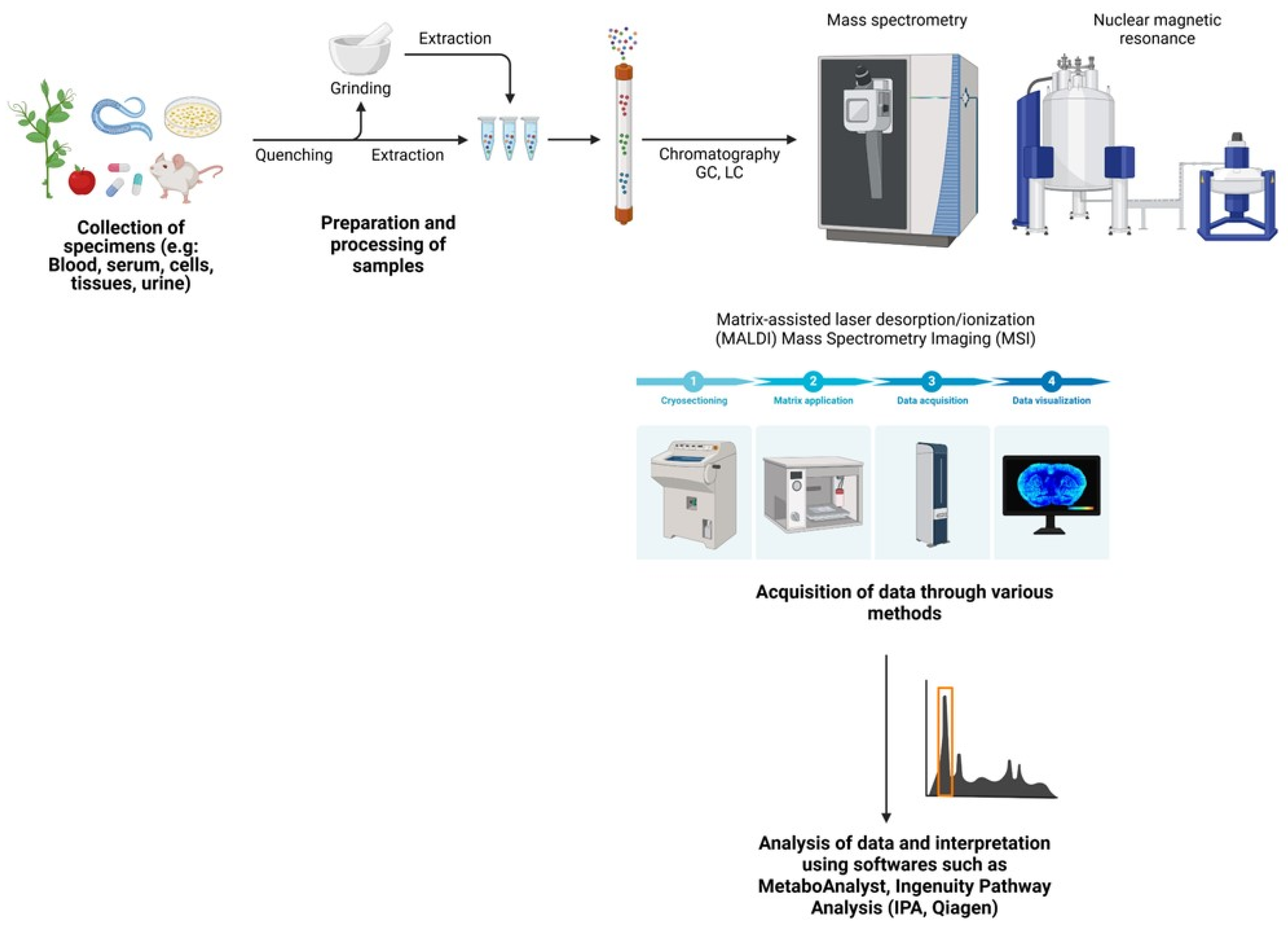

3. Untargeted and Targeted Metabolomics

4. Metabolomics for Biomarker Discovery

5. Metabolomics in Disease Subtyping

6. Metabolomics for Overcoming Therapy Resistance

7. Models for Metabolomic Studies

8. Metabolomics: Bridging other Omics

9. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TCA | Tricarboxylic acid |

| FDG-PET | 18F-deoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography |

| OXPHOS | Oxidative phosphorylation |

| MS | Mass Spectrometry |

| NMR | Nuclear Magnetic Resonance |

| FNAB | Fine-needle aspiration biopsy |

| LC-MS | Liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry |

| GC-MS | Gas chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry |

| LCM | Laser-capture microdissection |

| AUS | Atypia of undetermined significance |

| FLUS | Follicular lesion of undetermined significance |

| FN | Follicular neoplasm |

| SMC | Suspicious for malignant cells |

| MALDI-IMS | Matrix Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization-Imaging Mass Spectrometry |

| HR-MAS NMR | High-Resolution Magic Angle Spinning Nuclear Magnetic Resonance |

| LASS2 | Longevity assurance homologue 2 |

| BUME | Butanol/methanol |

| MTBE | Methyl tert-butyl ether |

| NIS | Sodium/iodide symporter |

| TSHR | Thyroid stimulating hormone receptor |

| DTC | Differentiated thyroid cancer |

| PTC | Papillary thyroid cancer |

| FTC | Follicular thyroid cancer |

| MTC | Medullary thyroid cancer |

| ATC | Anaplastic thyroid cancer |

| TSP | Trimethylsilylpropanoic acid |

| DSS | 4,4-dimethyl-4-silapentane-1-sulfonic acid |

| TKI | Tyrosine kinase inhibitors |

References

- Sipos, J.; Mazzaferri, E. Thyroid Cancer Epidemiology and Prognostic Variables. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 22, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherman, S.I. Thyroid carcinoma. Lancet 2003, 361, 501–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kondo, T.; Ezzat, S.; Asa, S.L. Pathogenetic mechanisms in thyroid follicular-cell neoplasia. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2006, 6, 292–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knudsen, N.; Laurberg, P.; Perrild, H.; Bülow, I.; Ovesen, L.; Jørgensen, T. Risk Factors for Goiter and Thyroid Nodules. Thyroid® 2002, 12, 879–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albi, E. , et al., Radiation and Thyroid Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2017, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Society, A.C. , Cancer Facts & Figures 2025. 2025.

- Zhou, Q.; Zhang, L.-Y.; Xie, C.; Zhang, M.-L.; Wang, Y.-J.; Liu, G.-H. Metabolomics as a potential method for predicting thyroid malignancy in children and adolescents. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2019, 36, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaballos, M.A.; Santisteban, P. Key signaling pathways in thyroid cancer. J. Endocrinol. 2017, 235, R43–R61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cibas, E.S.; Ali, S.Z. The Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology. Thyroid 2009, 19, 1159–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Schnadig, V.; Logrono, R.; Wasserman, P.G. Fine-needle aspiration of thyroid nodules: A study of 4703 patients with histologic and clinical correlations. Cancer 2007, 111, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.Z. , et al. , The 2023 Bethesda System for reporting thyroid cytopathology. Journal of the American Society of Cytopathology 2023, 12, 319–325. [Google Scholar]

- Yassa, L.; Cibas, E.S.; Benson, C.B.; Frates, M.C.; Doubilet, P.M.; Gawande, A.A.; Moore, F.D., Jr.; Kim, B.W.; Nosé, V.; Marqusee, E.; et al. Long-term assessment of a multidisciplinary approach to thyroid nodule diagnostic evaluation. Cancer 2007, 111, 508–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacini, F. , et al, Erratum: European consensus for the management of patients with differentiated thyroid carcinoma of the follicular epithelium. European Journal of Endocrinology 2006, 155, 385–385. [Google Scholar]

- Bongiovanni, M.; Spitale, A.; Faquin, W.C.; Mazzucchelli, L.; Baloch, Z.W. The Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology: A Meta-Analysis. Acta Cytol. 2012, 56, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, A.S.; Sarti, E.E.; Jain, K.S.; Wang, H.; Nixon, I.J.; Shaha, A.R.; Shah, J.P.; Kraus, D.H.; Ghossein, R.; Fish, S.A.; et al. Malignancy Rate in Thyroid Nodules Classified as Bethesda Category III (AUS/FLUS). Thyroid® 2014, 24, 832–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavromati, M.; Saiji, E.; Demarchi, M.S.; Lenoir, V.; Seipel, A.; Kuczma, P.; Jornayvaz, F.R.; Becker, M.; Fernandez, E.; De Vito, C.; et al. Unnecessary thyroid surgery rate for suspicious nodule in the absence of molecular testing. Eur. Thyroid. J. 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannoush, Z.C.; Ruiz-Cordero, R.; Jara, M.; Kargi, A.Y. Current State of Molecular Cytology in Thyroid Nodules: Platforms and Their Diagnostic and Theranostic Utility. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durante, C.; Hegedüs, L.; Czarniecka, A.; Paschke, R.; Russ, G.; Schmitt, F.; Soares, P.; Solymosi, T.; Papini, E. 2023 European Thyroid Association Clinical Practice Guidelines for thyroid nodule management. Eur. Thyroid. J. 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKay, C.; Turner, B.; Clarke, S.; Wallace, T.; Rigby, M.H. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of Molecular Testing for Indeterminate Thyroid Nodules in Nova Scotia. J. Otolaryngol.-Head Neck Surg. 2024, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, J.K.; Lindon, J.C.; Holmes, E. ‘Metabonomics’: Understanding the metabolic responses of living systems to pathophysiological stimuli via multivariate statistical analysis of biological NMR spectroscopic data. Xenobiotica 1999, 29, 1181–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojakowska, A.; Chekan, M.; Widlak, P.; Pietrowska, M. Application of Metabolomics in Thyroid Cancer Research. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2015, 2015, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spratlin, J.L.; Serkova, N.J.; Eckhardt, S.G. Clinical Applications of Metabolomics in Oncology: A Review. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 15, 431–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denkert, C.; Bucher, E.; Hilvo, M.; Salek, R.; Orešič, M.; Griffin, J.; Brockmöller, S.; Klauschen, F.; Loibl, S.; Barupal, D.K.; et al. Metabolomics of human breast cancer: new approaches for tumor typing and biomarker discovery. Genome Med. 2012, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thysell, E.; Surowiec, I.; Hörnberg, E.; Crnalic, S.; Widmark, A.; Johansson, A.I.; Stattin, P.; Bergh, A.; Moritz, T.; Antti, H.; et al. Metabolomic Characterization of Human Prostate Cancer Bone Metastases Reveals Increased Levels of Cholesterol. PLOS ONE 2010, 5, e14175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kind, T. , et al. , A comprehensive urinary metabolomic approach for identifying kidney cancerr. Anal Biochem, 2007, 363, 185–95. [Google Scholar]

- Howe, F.; Barton, S.; Cudlip, S.; Stubbs, M.; Saunders, D.; Murphy, M.; Wilkins, P.; Opstad, K.; Doyle, V.; McLean, M.; et al. Metabolic profiles of human brain tumors using quantitative in vivo 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Magn. Reson. Med. 2003, 49, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claudino, W.M.; Goncalves, P.H.; di Leo, A.; Philip, P.A.; Sarkar, F.H. Metabolomics in cancer: A bench-to-bedside intersection. Crit. Rev. Oncol. 2012, 84, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miccoli, P.; Torregrossa, L.; Shintu, L.; Magalhaes, A.; Chandran, J.; Tintaru, A.; Ugolini, C.; Minuto, M.N.; Miccoli, M.; Basolo, F.; et al. Metabolomics approach to thyroid nodules: A high-resolution magic-angle spinning nuclear magnetic resonance–based study. Surgery 2012, 152, 1118–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grogan, R.H.; Mitmaker, E.J.; Clark, O.H. The Evolution of Biomarkers in Thyroid Cancer—From Mass Screening to a Personalized Biosignature. Cancers 2010, 2, 885–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Wang, C.; Chi, C.; Wang, X.; Liu, S.; Zhao, W.; Ke, C.; Xu, G.; Li, E. Exhaled breath volatile biomarker analysis for thyroid cancer. Transl. Res. 2015, 166, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, X.; Zhong, X.; Tian, X. Metabolomics of papillary thyroid carcinoma tissues: potential biomarkers for diagnosis and promising targets for therapy. Tumor Biol. 2016, 37, 11163–11175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Shen, M.; Li, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhou, K.; Hu, W.; Xu, B.; Xia, Y.; Tang, W. GC-MS-based metabolomic analysis of human papillary thyroid carcinoma tissue. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2015, 36, 1607–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wenk, M.R. The emerging field of lipidomics. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2005, 4, 594–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandu, R.; Mok, H.J.; Kim, K.P. Phospholipids as cancer biomarkers: Mass spectrometry-based analysis. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2016, 37, 107–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, M.; Haugen, B.R.; Schlumberger, M. Progress in molecular-based management of differentiated thyroid cancer. Lancet 2013, 381, 1058–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krause, K.; Jeßnitzer, B.; Fuhrer, D.; Führer-Sakel, D. Proteomics in Thyroid Tumor Research. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009, 94, 2717–2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpi, A.; Mechanick, J.I.; Saussez, S.; Nicolini, A. Thyroid tumor marker genomics and proteomics: Diagnostic and clinical implications. J. Cell. Physiol. 2010, 224, 612–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrimpe-Rutledge, A.C.; Codreanu, S.G.; Sherrod, S.D.; McLean, J.A. Untargeted Metabolomics Strategies—Challenges and Emerging Directions. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2016, 27, 1897–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Qiu, L.; Wang, Y.; Qin, X.; Liu, H.; He, M.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Chen, X. Tissue imaging and serum lipidomic profiling for screening potential biomarkers of thyroid tumors by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2014, 406, 4357–4370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deja, S.; Dawiskiba, T.; Balcerzak, W.; Orczyk-Pawiłowicz, M.; Głód, M.; Pawełka, D.; Młynarz, P. Follicular Adenomas Exhibit a Unique Metabolic Profile. 1H NMR Studies of Thyroid Lesions. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e84637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalbert, A.; Brennan, L.; Fiehn, O.; Hankemeier, T.; Kristal, B.S.; van Ommen, B.; Pujos-Guillot, E.; Verheij, E.; Wishart, D.; Wopereis, S. Mass-spectrometry-based metabolomics: limitations and recommendations for future progress with particular focus on nutrition research. Metabolomics 2009, 5, 435–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beger, R.D. A Review of Applications of Metabolomics in Cancer. Metabolites 2013, 3, 552–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brennan, L. NMR-based metabolomics: From sample preparation to applications in nutrition research. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 2014, 83, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffin, J.L.; Kauppinen, R.A. Tumour Metabolomics in Animal Models of Human Cancer. J. Proteome Res. 2006, 6, 498–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felli, I.C.; Brutscher, B. Recent Advances in Solution NMR: Fast Methods and Heteronuclear Direct Detection. Chemphyschem 2009, 10, 1356–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warburg, O. On the Origin of Cancer Cells. Science 1956, 123, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suman, S.; Sharma, R.K.; Kumar, V.; Sinha, N.; Shukla, Y. Metabolic fingerprinting in breast cancer stages through 1H NMR spectroscopy-based metabolomic analysis of plasma. 2018, 160, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michálková, L. , et al., Diagnosis of pancreatic cancer via(1)H NMR metabolomics of human plasma. Analyst 2018, 143, 5974–5978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.J.; Cho, H.R.; Kim, T.M.; Keam, B.; Kim, J.W.; Wen, H.; Park, C.-K.; Lee, S.-H.; Im, S.-A.; Kim, J.E.; et al. An NMR metabolomics approach for the diagnosis of leptomeningeal carcinomatosis in lung adenocarcinoma cancer patients. Int. J. Cancer 2014, 136, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San-Millán, I.; Brooks, G.A. Reexamining cancer metabolism: lactate production for carcinogenesis could be the purpose and explanation of the Warburg Effect. Carcinog. 2016, 38, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagayama, Y.; Hamada, K. Reprogramming of Cellular Metabolism and Its Therapeutic Applications in Thyroid Cancer. Metabolites 2022, 12, 1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abooshahab, R.; Gholami, M.; Sanoie, M.; Azizi, F.; Hedayati, M. Advances in metabolomics of thyroid cancer diagnosis and metabolic regulation. Endocrine 2019, 65, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abooshahab, R.; Ardalani, H.; Zarkesh, M.; Hooshmand, K.; Bakhshi, A.; Dass, C.R.; Hedayati, M. Metabolomics—A Tool to Find Metabolism of Endocrine Cancer. Metabolites 2022, 12, 1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coelho, M.; Raposo, L.; Goodfellow, B.J.; Atzori, L.; Jones, J.; Manadas, B. The Potential of Metabolomics in the Diagnosis of Thyroid Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neto, V.; Esteves-Ferreira, S.; Inácio, I.; Alves, M.; Dantas, R.; Almeida, I.; Guimarães, J.; Azevedo, T.; Nunes, A. Metabolic Profile Characterization of Different Thyroid Nodules Using FTIR Spectroscopy: A Review. Metabolites 2022, 12, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi, S.A.; Khorsand, B.; Salehipour, P.; Hedayati, M. Metabolite signature of human malignant thyroid tissue: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Med. 2024, 13, e7184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi, S.A.; Kalari, M.; Haghzad, T.; Haddadi, F.; Nasiri, S.; Hedayati, M. Exploring the potential of myo-inositol in thyroid disease management: focus on thyroid cancer diagnosis and therapy. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1418956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, L.; Luo, Y.; Zhou, M.; Huo, L.; Chen, H.; Zuo, Q.; Deng, W. Comparison of Diagnostic Accuracy of Thyroid Cancer With Ultrasound-Guided Fine-Needle Aspiration and Core-Needle Biopsy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi, S.A.; Mahmanzar, M.; Gh. , B.F.N.M.; Zamani, Z.; Nasiri, S.; Hedayati, M. Plasma metabolites analysis of patients with papillary thyroid cancer: A preliminary untargeted 1H NMR-based metabolomics. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2023, 241, 115946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Liu, C.; Hou, Y.; Li, J.; Guo, Z.; Chen, X.; Zhang, L.; Peng, S.; Hong, S.; Xu, L.; et al. Integrative metabolomic characterization identifies plasma metabolomic signature in the diagnosis of papillary thyroid cancer. Oncogene 2022, 41, 2422–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’andréa, G.; Jing, L.; Peyrottes, I.; Guigonis, J.-M.; Graslin, F.; Lindenthal, S.; Sanglier, J.; Gimenez, I.; Haudebourg, J.; Vandersteen, C.; et al. Pilot Study on the Use of Untargeted Metabolomic Fingerprinting of Liquid-Cytology Fluids as a Diagnostic Tool of Malignancy for Thyroid Nodules. Metabolites 2023, 13, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezig, L.; Servadio, A.; Torregrossa, L.; Miccoli, P.; Basolo, F.; Shintu, L.; Caldarelli, S. Diagnosis of post-surgical fine-needle aspiration biopsies of thyroid lesions with indeterminate cytology using HRMAS NMR-based metabolomics. Metabolomics 2018, 14, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryoo, I.; Kwon, H.; Kim, S.C.; Jung, S.C.; A Yeom, J.; Shin, H.S.; Cho, H.R.; Yun, T.J.; Choi, S.H.; Sohn, C.-H.; et al. Metabolomic analysis of percutaneous fine-needle aspiration specimens of thyroid nodules: Potential application for the preoperative diagnosis of thyroid cancer. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 30075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torregrossa, L.; Shintu, L.; Chandran, J.N.; Tintaru, A.; Ugolini, C.; Magalhães, A.; Basolo, F.; Miccoli, P.; Caldarelli, S. Toward the Reliable Diagnosis of Indeterminate Thyroid Lesions: A HRMAS NMR-Based Metabolomics Case of Study. J. Proteome Res. 2012, 11, 3317–3325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Planque, M.; Igelmann, S.; Campos, A.M.F.; Fendt, S.-M. Spatial metabolomics principles and application to cancer research. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2023, 76, 102362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, X.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, M.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, X.; Guo, K.; Wang, X.; Huang, J.; Li, T.; Sun, L.; et al. Spatially resolved metabolomics: From metabolite mapping to function visualising. Clin. Transl. Med. 2024, 14, e70031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojakowska, A. , et al., Discrimination of papillary thyroid cancer from non-cancerous thyroid tissue based on lipid profiling by mass spectrometry imaging. Endokrynol Pol 2018, 69, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeHoog, R.J. , et al., Preoperative metabolic classification of thyroid nodules using mass spectrometry imaging of fine-needle aspiration biopsies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019, 116, 21401–21408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, E.N.; West, C.A.; McDowell, C.T.; Lu, X.; Bruner, E.; Mehta, A.S.; Aoki-Kinoshita, K.F.; Angel, P.M.; Drake, R.R. An N-glycome tissue atlas of 15 human normal and cancer tissue types determined by MALDI-imaging mass spectrometry. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Huang, L.; Li, T.; Abliz, Z.; He, J.; Chen, J. Identification of Diagnostic Metabolic Signatures in Thyroid Tumors Using Mass Spectrometry Imaging. Molecules 2023, 28, 5791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatami, F.; Payab, M.; Sarvari, M.; Gilany, K.; Larijani, B.; Arjmand, B.; Tavangar, S.M. Oncometabolites as biomarkers in thyroid cancer: a systematic review. Cancer Manag. Res. 2019, 11, 1829–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abooshahab, R.; Razavi, F.; Ghorbani, F.; Hooshmand, K.; Zarkesh, M.; Hedayati, M. Thyroid cancer cell metabolism: A glance into cell culture system-based metabolomics approaches. Exp. Cell Res. 2024, 435, 113936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berinde, G.M.; Socaciu, A.I.; Socaciu, M.A.; Petre, G.E.; Socaciu, C.; Piciu, D. Metabolic Profiles and Blood Biomarkers to Discriminate between Benign Thyroid Nodules and Papillary Carcinoma, Based on UHPLC-QTOF-ESI+-MS Analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berinde, G.M.; Socaciu, A.I.; Socaciu, M.A.; Petre, G.E.; Rajnoveanu, A.G.; Barsan, M.; Socaciu, C.; Piciu, D. In Search of Relevant Urinary Biomarkers for Thyroid Papillary Carcinoma and Benign Thyroid Nodule Differentiation, Targeting Metabolic Profiles and Pathways via UHPLC-QTOF-ESI+-MS Analysis. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Wen, X.; Li, X.; Yan, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhao, X.; Tian, Y.; Ling, R.; Duan, Y. Identifying potential breath biomarkers for early diagnosis of papillary thyroid cancer based on solid-phase microextraction gas chromatography-high resolution mass spectrometry with metabolomics. Metabolomics 2024, 20, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wen, X.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Qian, C.; Tian, Y.; Ling, R.; Duan, Y. Diagnostic approach to thyroid cancer based on amino acid metabolomics in saliva by ultra-performance liquid chromatography with high resolution mass spectrometry. Talanta 2021, 235, 122729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Hu, Q.; Hou, H.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Chen, H.; Deng, H.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, L.; et al. Metabolite analysis-aided diagnosis of papillary thyroid cancer. Endocrine-Related Cancer 2019, 26, 829–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, W.; Wang, C.; Wang, X.; Luo, J.; He, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, S.; Zhou, Q.; Sun, D.; et al. Study on identification of diagnostic biomarkers in serum for papillary thyroid cancer in different iodine nutrition regions. Biomarkers 2024, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Lin, Y.; Qin, L.; Zeng, X.; Jiang, H.; Liang, Y.; Wen, S.; Li, X.; Huang, S.; Li, C.; et al. Serum metabolome associated with novel and legacy per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances exposure and thyroid cancer risk: A multi-module integrated analysis based on machine learning. Environ. Int. 2024, 195, 109203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Liu, Y.; Peng, J.; Jiang, Y.; Lin, X.; Zhang, J. Identification of serum metabolites associated with polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) exposure in papillary thyroid carcinoma: a case–control study. Environ. Geochem. Heal. 2024, 46, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Li, R.; Miao, C.; Miccoli, P.; Lu, J. Non-invasive diagnosis of papillary thyroid microcarcinoma using a novel metabolomics analysis of urine. Endocrine 2024, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojakowska, A.; Chekan, M.; Marczak, Ł.; Polanski, K.; Lange, D.; Pietrowska, M.; Widlak, P. Detection of metabolites discriminating subtypes of thyroid cancer: Molecular profiling of FFPE samples using the GC/MS approach. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2015, 417, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baloch, Z.W.; Asa, S.L.; Barletta, J.A.; Ghossein, R.A.; Juhlin, C.C.; Jung, C.K.; LiVolsi, V.A.; Papotti, M.G.; Sobrinho-Simões, M.; Tallini, G.; et al. Overview of the 2022 WHO Classification of Thyroid Neoplasms. Endocr. Pathol. 2022, 33, 27–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, N.; Chen, D.; Ma, B.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Ni, Z.; Wang, W.; Liao, T.; et al. Integrated proteogenomic and metabolomic characterization of papillary thyroid cancer with different recurrence risks. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Y.J.; Yi, J.W.; Oh, S.W.; A Kim, Y.; Yi, K.H.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, K.E. Upregulation of SLC2 (GLUT) family genes is related to poor survival outcomes in papillary thyroid carcinoma: Analysis of data from The Cancer Genome Atlas. Surgery 2017, 161, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, S.; i Luo, Y.; Wu, W.; Zhang, T.; Yang, Y.; Ji, Q.; Wu, Y.; Shi, R.; Ma, B.; Xu, M.; et al. Identification of lipid metabolism-related genes as prognostic indicators in papillary thyroid cancer. Acta Biochim. et Biophys. Sin. 2021, 53, 1579–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, E.J.; Kim, D.; Kim, J.K.; Kang, S.-W.; Lee, J.; Jeong, J.J.; Nam, K.-H.; Chung, W.Y.; Kim, K. Lactate Dehydrogenase A as a Potential New Biomarker for Thyroid Cancer. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 36, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, F. Construction and evaluation of a prognosis prediction model for thyroid carcinoma based on lipid metabolism-related genes. 2022, 43, 323–332. [Google Scholar]

- Enomoto, K.; Hotomi, M. Amino Acid Transporters as Potential Therapeutic Targets in Thyroid Cancer. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 35, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Sun, W.; Wang, Z.; Lv, C.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, D.; Dong, W.; Shao, L.; He, L.; Ji, X.; et al. FTO suppresses glycolysis and growth of papillary thyroid cancer via decreasing stability of APOE mRNA in an N6-methyladenosine-dependent manner. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 41, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.E.; Park, S.; Yi, S.; Choi, N.R.; Lim, M.A.; Chang, J.W.; Won, H.-R.; Kim, J.R.; Ko, H.M.; Chung, E.-J.; et al. Unraveling the role of the mitochondrial one-carbon pathway in undifferentiated thyroid cancer by multi-omics analyses. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Du, J.; Li, D.; He, W.; Liu, Z.; Liu, L.; Yang, X.; Cheng, X.; Chen, R.; Yang, Y. LASS2 suppresses metastasis in multiple cancers by regulating the ferroptosis signalling pathway through interaction with TFRC. Cancer Cell Int. 2024, 24, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, B.; Gao, W.; Xu, T.; Liu, C.; Wu, D.; Tang, W. A UPLC Q-Exactive Orbitrap Mass Spectrometry-Based Metabolomic Study of Serum and Tumor Tissue in Patients with Papillary Thyroid Cancer. Toxics 2022, 11, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, J.W.; Han, K.; Lee, J.; Kim, E.-K.; Moon, H.J.; Yoon, J.H.; Park, V.Y.; Baek, H.-M.; Kwak, J.Y. Application of metabolomics in prediction of lymph node metastasis in papillary thyroid carcinoma. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0193883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yin, S.; Zhang, X.; Wei, W.; Sun, Z.; Song, H.; Qiu, Z.; Wang, C.; et al. A distinct serum metabolic signature of distant metastatic papillary thyroid carcinoma. Clin. Endocrinol. 2017, 87, 844–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cararo Lopes, E. , et al. , Integrated metabolic and genetic analysis reveals distinct features of human differentiated thyroid cancer. Clin Transl Med. 2023, 13, e1298. [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang, J.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, J.; Tan, L.; Zou, L. Integration of metabolomics and transcriptomics reveals metformin suppresses thyroid cancer progression via inhibiting glycolysis and restraining DNA replication. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 168, 115659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, S.; Daley, B.; Gaskins, K.; Vasko, V.V.; Boufraqech, M.; Patel, D.; Sourbier, C.; Reece, J.; Cheng, S.-Y.; Kebebew, E.; et al. Metformin Targets Mitochondrial Glycerophosphate Dehydrogenase to Control Rate of Oxidative Phosphorylation and Growth of Thyroid Cancer In Vitro and In Vivo. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 4030–4043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Tang, X.; Dong, J.; Feng, J.; Chen, M.; Zhu, X. Metabolomic screening of radioiodine refractory thyroid cancer patients and the underlying chemical mechanism of iodine resistance. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xu, Q.; Xuan, Z.; Mao, Y.; Tang, X.; Yang, K.; Song, F.; Zhu, X. Metabolomics reveals the implication of acetoacetate and ketogenic diet therapy in radioiodine-refractory differentiated thyroid carcinoma. Oncol. 2024, 29, e1120–e1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Ning, K.; Liu, X.; Liang, Y.; Jiao, Z.; Zou, B.; Cai, T.; Yang, Z.; Chen, W.; Wu, T.; et al. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) exposure is associated with radioiodine therapy resistance and dedifferentiation of differentiated thyroid cancer. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 367, 125629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, G.; Gao, D.; Liu, Y.; Yu, X.; Jiang, W.; Lv, Z. Early and long-term responses of intestinal microbiota and metabolites to 131I treatment in differentiated thyroid cancer patients. BMC Med. 2024, 22, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, G.; Gao, D.; Jiang, W.; Yu, X.; Tong, J.; Liu, X.; Qiao, T.; Wang, R.; Zhang, M.; Wang, S.; et al. Disrupted gut microecology after high-dose 131I therapy and radioprotective effects of arachidonic acid supplementation. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. 2024, 51, 2395–2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumari, S.; Thakur, S.; Cardenas, S.; Makarewicz, A.; Klubo-Gwiezdzinska, J. Metabolic Reprogramming Contributes to Resistance Towards Lenvatinib in Thyroid Cancer. VideoEndocrinology 2024, 11, 54–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Wang, J.; Mao, Y.; Xuan, Z.; Yang, K.; Tang, X.; Zhu, X. Combined BRAF and PIM1 inhibitory therapy for papillary thyroid carcinoma based on BRAFV600E regulation of PIM1: Synergistic effect and metabolic mechanisms. Neoplasia 2024, 52, 100996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Peng, Y.; Su, Y.; Diao, C.; Qian, J.; Zhan, X.; Cheng, R. Transcriptome and metabolome sequencing identifies glutamate and LPAR1 as potential factors of anlotinib resistance in thyroid cancer. Anti-Cancer Drugs 2024, 35, 741–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.H. C. Lin, and C.C. Chen, Lysophosphatidic Acid Receptor Antagonists and Cancer: The Current Trends, Clinical Implications, and Trials. Cells 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, A.; Kouznetsova, V.L.; Kesari, S.; Tsigelny, I.F. Diagnostics of Thyroid Cancer Using Machine Learning and Metabolomics. Metabolites 2023, 14, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurashige, T.; Shimamura, M.; Hamada, K.; Matsuse, M.; Mitsutake, N.; Nagayama, Y. Characterization of metabolic reprogramming by metabolomics in the oncocytic thyroid cancer cell line XTC.UC1. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, S.; Adewale, R.; Klubo-Gwiezdzinska, J. The Molecular Landscape of Hürthle Cell Thyroid Cancer Is Associated with Altered Mitochondrial Function—A Comprehensive Review. Cells 2020, 9, 1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tronci, L.; Serreli, G.; Piras, C.; Frau, D.V.; Dettori, T.; Deiana, M.; Murgia, F.; Santoru, M.L.; Spada, M.; Leoni, V.P.; et al. Vitamin C Cytotoxicity and Its Effects in Redox Homeostasis and Energetic Metabolism in Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma Cell Lines. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yu, X.; Qu, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Jia, K.; Du, Q.; Han, J.; Liu, H.; Zhang, X.; et al. High-Performance Metabolic Profiling of High-Risk Thyroid Nodules by ZrMOF Hybrids. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 21336–21346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cristiani, S.; Bertolini, A.; Carnicelli, V.; Contu, L.; Vitelli, V.; Saba, A.; Saponaro, F.; Chiellini, G.; Sabbatini, A.R.M.; Giambelluca, M.A.; et al. Development and primary characterization of a human thyroid organoid in vitro model for thyroid metabolism investigation. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2024, 594, 112377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Liang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Liu, J.; Wei, H.; Chen, H.; Wei, W.; Chen, D.; Zhao, Y. Establishment of papillary thyroid cancer organoid lines from clinical specimens. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1140888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.; Tan, Y.; Li, Z.; Li, W.; Yu, L.; Chen, W.; Liu, Y.; Liu, L.; Guo, L.; Huang, W.; et al. Organoid Cultures Derived From Patients With Papillary Thyroid Cancer. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 106, 1410–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhuli, K.; Medori, M.C.; Donato, K.; E Maltese, P.; Tanzi, B.; Tezzele, S.; Mareso, C.; Miertus, J.; Generali, D.; A Donofrio, C.; et al. Omics sciences and precision medicine in thyroid cancer. . 2023, 174, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jundi, M.; Thakur, S.; Gubbi, S.; Klubo-Gwiezdzinska, J. Novel Targeted Therapies for Metastatic Thyroid Cancer—A Comprehensive Review. Cancers 2020, 12, 2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boufraqech, M.; Nilubol, N. Multi-omics Signatures and Translational Potential to Improve Thyroid Cancer Patient Outcome. Cancers 2019, 11, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulfidan, G.; Soylu, M.; Demirel, D.; Erdonmez, H.B.C.; Beklen, H.; Sarica, P.O.; Arga, K.Y.; Turanli, B. Systems biomarkers for papillary thyroid cancer prognosis and treatment through multi-omics networks. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2021, 715, 109085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | Review Design | Biospecimen used | Significantly Altered Metabolites |

|---|---|---|---|

| Khatami et al., 2019 [71] |

Systematic review of 31 metabolomic studies (15 targeted and 16 untargeted) investigating metabolite biomarkers of TC. All metabolomic techniques included in search criteria. | Plasma, serum, urine, or FNA specimens. Malignant TC vs. control (healthy, benign nodules, goiter) |

Citrate ↓ Lactate ↑ |

| Abooshahab et al., 2022 [53] |

Systematic review of metabolomics in endocrine cancers. 35 articles published from 2010-2022 on thyroid cancer metabolomics. Techniques included NMR (15 papers), GC/MS (8 papers), and LC/MS (12 papers). | Tissue, serum/plasma, urine, FNA samples Malignant vs. benign tumors |

Lactate ↑ Choline ↓ Mono- and disaccharides, and TCA intermediates altered |

| Coelho et al., 2020 [54] |

Review includes 45 original studies on TC metabolomic biomarkers. NMR (21 papers), MS (19 papers), other techniques (5 papers). Spatial metabolomics applied in several listed studies. | Tissue, plasma, serum, urine, feces, breath TC vs. healthy/benign controls |

Choline ↑ Lactate ↑ Tyrosine ↑ |

| Abooshahab et al., 2024 [72] |

Review of metabolomic studies on TC cell lines. 7 papers identified. MS (6 papers) and NMR (1 paper). | TC cell lines | Various alterations in glycolysis and TCA cycle metabolites |

| Neto et al., 2022 [55] |

Review of studies using FTIR spectroscopy to characterize normal vs. tumor samples. 13 papers met the criteria. | Thyroid tissue and cytology samples | Lipids ↓ Carbohydrates ↓ Lipid metabolism ↑ |

| Razavi et al., 2024 [56] |

Systematic review and meta-analysis of NMR-based metabolomic studies. 12 studies met the search criteria. | Tissue and FNAB specimens. Malignant vs. benign. |

Lactate ↑ Alanine ↑ Citrate ↓ |

| Nagayama et al., 2022 [51] |

Summarize the recent findings of metabolic reprogramming in TC as well as recent reports of metabolism-targeted therapies. | Thyroid tissue and cytology samples | Glucose metabolism ↑ Amino acid metab. ↑ Lipid metabolism ↑ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).