Submitted:

15 May 2023

Posted:

18 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Participants

2.2. Sample Collection and Processing

2.3. Biochemical Analysis

2.4. Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Characteristics of Study Populations

| MGUS (n = 20) | MM(n = 30) | Between groups, P-value |

Reference range, male/female | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age in years (mean ± SD)* | 70.35 ± 11 | 70.7 ± 10 | 0.996 | |

| Male gender | 10 (50%) | 14 (47%) | ||

| Clinical and Biochemical characteristics | ||||

| ISS stage (%) | ||||

| I | 4 (13%) | |||

| II | 16 (53 %) | |||

| III | 10 (33%) | |||

| Bone changes (%) | ||||

| None | 8 (27%) | |||

| Halisteresis | 0 (0%) | |||

| Localized | 3 (10%) | |||

| Spread | 19 (63%) | |||

| M-protein, isotype (%) | ||||

| IgG | 15 (50%) | 22 (73%) | ||

| Kappa | 8 (53%) | 17 (77%) | ||

| Lambda | 7 (47%) | 5 (23%) | ||

| IgA | 4 (20%) | 8 (27%) | ||

| Kappa | 2 (50%) | 6 (75%) | ||

| Lambda | 2 (50%) | 2 (25%) | ||

| Plasma cells in bone marrow (%) | 6.0 ± 2.3 | 41 ± 19.4 | <0.001 | |

| M-protein (g/l) | 7.4 ± 6.6 | 42.9 ± 22.4 | <0.001 | |

| κ-Chain, free (mg/l) | 128.5 ± 355.3 | 1179.1 ± 3434.8 | 0.080 | 3.3-19.4 |

| λ-Chain, free (mg/l) | 26.3 ± 35.0 | 225.6 ± 652.5 | 0.014 | 5.7-26.3 |

| Creatinine (µmol/l) | 74.4± 26.6 | 120.2 ± 94.1 / 87.4 ± 35.6 | 0.199 | 60-105/45-90 |

| CRP (mg/l) | 7.4 ± 10.9 | 12.3 ± 25.0 | 0.812 | <8.0 |

| Protein (g/l) | 77.2 ± 7.2 | 107.8 ± 20.0 | <0.001 | 62-78 |

| Albumin (g/l) | 36.8 ± 3.1 | 29.5 ± 4.9 | <0.001 | 34-45 |

| Fibrinogen (μM) | 11.4 ± 3.4 | 10.6 ± 3.9 | 0.156 | 5-12 |

| Hemoglobin (M/F) (mmol/l) | 8.6 ± 1.3\7.7 ± 0.8 | 6.4 ± 1.4\5.8 ± 0.7 | <0.001 | 8.3-10.5/7.3-9.5 |

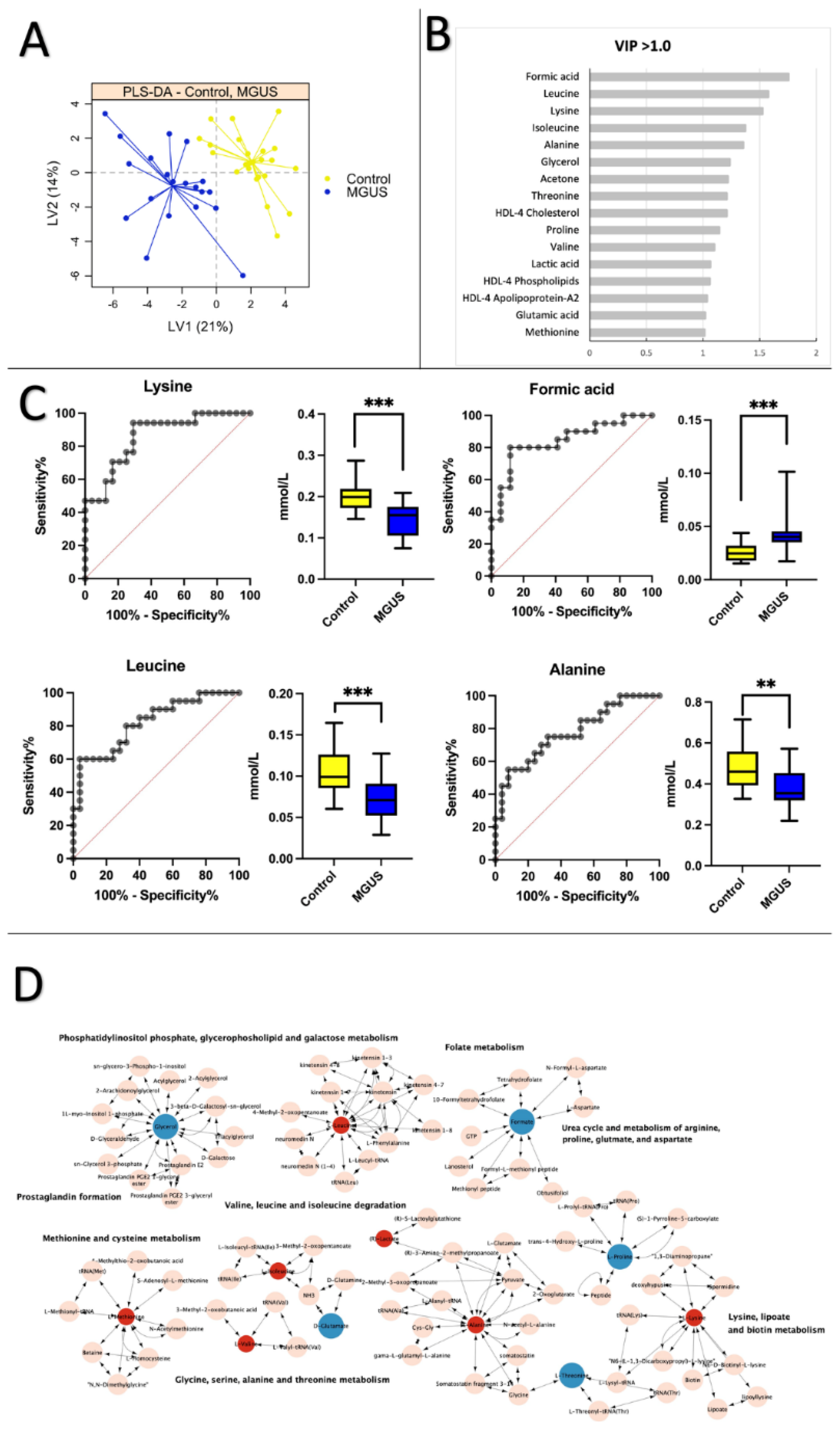

3.2. Healthy Control vs. MGUS: Progression of MGUS associated with imbalanced amino acid metabolism

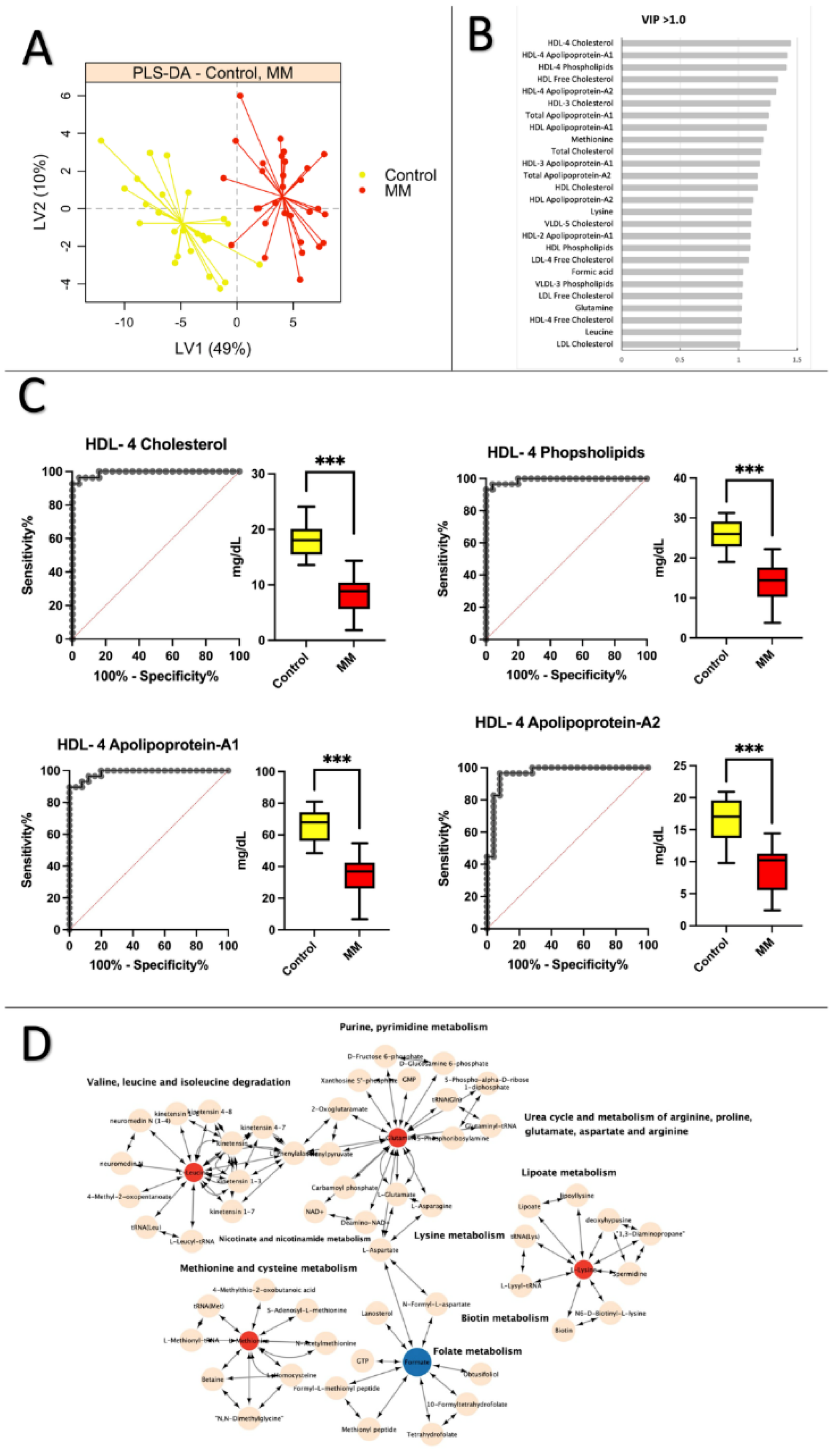

3.3. Healthy Control vs. MM: Low levels of apolipoprotein and cholesterol are prevalent in MM patients

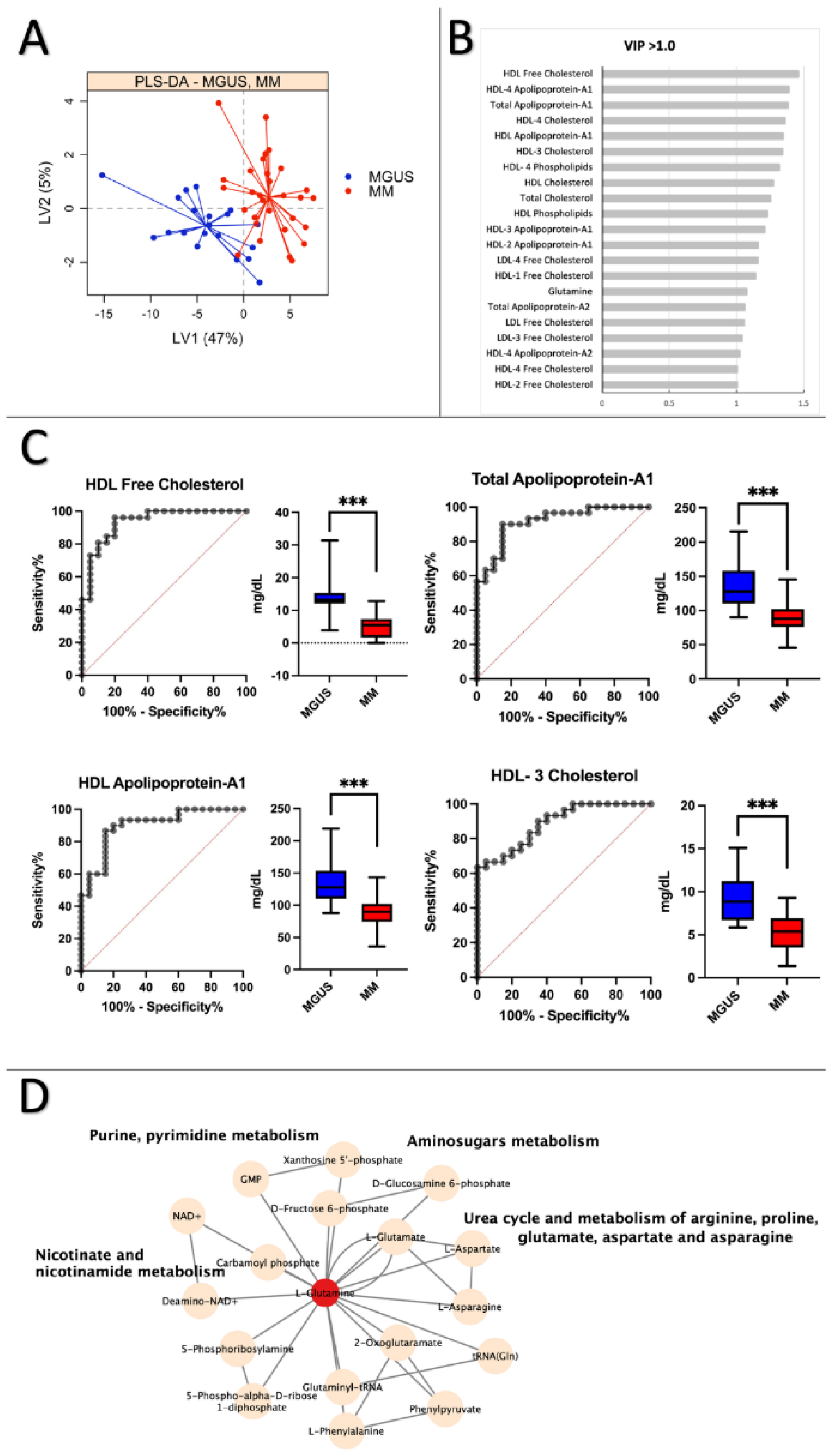

3.4. MGUS vs. MM: Lipoprotein subfractions alterations in MGUS contribute to symptomatic MM

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rajkumar SV. Updated Diagnostic Criteria and Staging System for Multiple Myeloma. American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book. 2016 May 19;(36):e418–23. https://www.nature.com/articles/nrdp201746 PMID: 20829374. [PubMed]

- Koshiaris C, Oke J, Abel L, Nicholson BD, Ramasamy K, van den Bruel A. Quantifying intervals to diagnosis in myeloma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2018 Jun 22;8(6):e019758. http://dx.doi.org.qulib.idm.oclc.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019758 PMID: 29934381. [PubMed]

- van de Donk NWCJ, Pawlyn C, Yong KL. Multiple myeloma. Lancet. 2021 Jan 30;397(10272):410-427. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00135-5 PMID: 33516340. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar SK, Rajkumar V, Kyle RA, van Duin M, Sonneveld P, Mateos MV, et al. Multiple myeloma. Nature Reviews Disease Primers 2017 3: 17046. 10.1038/nrdp.2017.46 PMID: 28726797. [PubMed]

- Bird SA, Boyd K. Multiple myeloma: an overview of management. Palliat Care Soc Pract. 2019 Oct 9;13:1178224219868235. https://doiorg.qulib.idm.oclc.org/10.1177/1178224219868235 PMID: 32215370. [PubMed]

- Donk NWCJ van de, Pawlyn C, Yong KL. Multiple myeloma. Lancet. 2021 Jan 30;397(10272):410-427. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00135-5 PMID: 3351634. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludwig H, Durie SN, Meckl A, Hinke A, Durie B. Multiple Myeloma Incidence and Mortality Around the Globe; Interrelations Between Health Access and Quality, Economic Resources, and Patient Empowerment. Oncologist. 2020 Sep;25(9):e1406-e1413. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2020-0141 PMID: 32335971. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu S, Li W, Lin M, Li T. Serum Protein Electrophoresis and Immunofixation Electrophoresis Detection in Multiple Myeloma. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2021 Jul;30(7):864-867. doi: 10.29271/jcpsp.2021.07.864 PMID: 34271795. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steiner N, Müller U, Hajek R, Sevcikova S, Borjan B, Jöhrer K, Göbel G, Pircher A, Gunsilius E. The metabolomic plasma profile of myeloma patients is considerably different from healthy subjects and reveals potential new therapeutic targets. PLoS One. 2018 Aug 10;13(8):e0202045. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0202045 PMID: 30096165. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hideshima T, Mitsiades C, Tonon G, Richardson PG, Anderson KC. Understanding multiple myeloma pathogenesis in the bone marrow to identify new therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007 Aug;7(8):585-98. doi: 10.1038/nrc2189 PMID: 17646864. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fairfield H, Falank C, Avery L, Reagan MR. Multiple myeloma in the marrow: pathogenesis and treatments. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2016 Jan;1364(1):32-51. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13038 PMID: 2700278. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiecchio L, Dagrada GP, White HE, Towsend MR, Protheroe RK, Cheung KL, Stockley DM, Orchard KH, Cross NC, Harrison CJ, Ross FM; UK Myeloma Forum. Frequent upregulation of MYC in plasma cell leukemia. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2009 Jul;48(7):624-36. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20670 PMID: 19396865. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puchades-Carrasco L, Lecumberri R, Martínez-López J, Lahuerta JJ, Mateos MV, Prósper F, San-Miguel JF, Pineda-Lucena A. Multiple myeloma patients have a specific serum metabolomic profile that changes after achieving complete remission. Clin Cancer Res. 2013 Sep 1;19(17):4770-9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2917 PMID: 23873687. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schraw JM, Junco JJ, Brown AL, Scheurer ME, Rabin KR, Lupo PJ. Metabolomic profiling identifies pathways associated with minimal residual disease in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. EBioMedicine. 2019 Oct;48:49-57. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.09.033 PMID: 31631039. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu T, Peng XC, Li B. The Metabolic Profiles in Hematological Malignancies. Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus. 2019 Oct;35(4):625-634. doi: 10.1007/s12288-019-01107-8 PMID: 31741613. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt DR, Patel R, Kirsch DG, Lewis CA, Vander Heiden MG, Locasale JW. Metabolomics in cancer research and emerging applications in clinical oncology. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021 Jul;71(4):333-358. https://doi-org.qulib.idm.oclc.org/10.3322/caac.2167. PMID: 33982817. [PubMed]

- Emwas AH. The strengths and weaknesses of NMR spectroscopy and mass spectrometry with particular focus on metabolomics research. Methods Mol Biol. 2015;1277:161-93. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2377-9_13 PMID: 25677154. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emwas AH, Roy R, McKay RT, Tenori L, Saccenti E, Gowda GAN, Raftery D, Alahmari F, Jaremko L, Jaremko M, Wishart DS. NMR Spectroscopy for Metabolomics Research. Metabolites. 2019 Jun 27;9(7):123. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo9070123 PMID: 31252628. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moco S. Studying Metabolism by NMR-Based Metabolomics. Front Mol Biosci. 2022 Apr 27;9:882487. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmolb.2022.882487 PMID: 35573745. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dieterle F, Riefke B, Schlotterbeck G, Ross A, Senn H, Amberg A. NMR and MS methods for metabonomics. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;691:385-415. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-849-2_24 PMID: 20972767. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajpai R, Matulis SM, Wei C, Nooka AK, Von Hollen HE, Lonial S, Boise LH, Shanmugam M. Targeting glutamine metabolism in multiple myeloma enhances BIM binding to BCL-2 eliciting synthetic lethality to venetoclax. Oncogene. 2016 Jul 28;35(30):3955-64. doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.464 PMID: 26640142. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludwig C, Williams DS, Bartlett DB, Essex SJ, McNee G, Allwood JW, et al. Alterations in bone marrow metabolism are an early and consistent feature during the development of MGUS and multiple myeloma. Blood Cancer J. 2015 Oct 16;5(10):e359. doi: 10.1038/bcj.2015.85 PMID: 26473531. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fei F, Ma T, Zhou X, Zheng M, Cao B, Li J. Metabolic markers for diagnosis and risk-prediction of multiple myeloma. Life Sci. 2021 Jan 15;265:118852. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118852 PMID: 33278388. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du H, Wang L, Liu B, Wang J, Su H, Zhang T, Huang Z. Analysis of the Metabolic Characteristics of Serum Samples in Patients With Multiple Myeloma. Front Pharmacol. 2018 Aug 22;9:884. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2018.00884 PMID: 30186161. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lodi A, Tiziani S, Khanim FL, Günther UL, Viant MR, Morgan GJ, Bunce CM, Drayson MT. Proton NMR-based metabolite analyses of archived serial paired serum and urine samples from myeloma patients at different stages of disease activity identifies acetylcarnitine as a novel marker of active disease. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e56422. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0056422 PMID: 23431376. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonsalves WI, Broniowska K, Jessen E, Petterson XM, Bush AG, Gransee J, Lacy MQ, Hitosugi T, Kumar SK. Metabolomic and Lipidomic Profiling of Bone Marrow Plasma Differentiates Patients with Monoclonal Gammopathy of Undetermined Significance from Multiple Myeloma. Sci Rep. 2020 Jun 24;10(1):10250. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-67105-3 PMID: 32581232. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medina EA, Oberheu K, Polusani SR, Ortega V, Velagaleti GV, Oyajobi BO. PKA/AMPK signaling in relation to adiponectin's antiproliferative effect on multiple myeloma cells. Leukemia. 2014 Oct;28(10):2080-9. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.112 PMID: 24646889. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuliszkiewicz-Janus M, Baczyński S. Chemotherapy-associated changes in 31P MRS spectra of sera from patients with multiple myeloma. NMR Biomed. 1995 May;8(3):127-32. https://doi-org.qulib.idm.oclc.org/10.1002/nbm.1940080308 PMID: 8580000. [PubMed]

- H Hachem, G Favre, G Raynal GS. Plasma lipoproteins and multiple myeloma. Variations of lipid constituents of HDL and apolipoproteins A1 and B. Ann Biol Clin (Paris). 1983; 1983;41(3):181-5. PMID: 6414341. [PubMed]

- Papachristou NI, Blair HC, Kypreos KE, Papachristou DJ. High-density lipoprotein (HDL) metabolism and bone mass. J Endocrinol. 2017 May;233(2):R95-R107. https://doi.org/10.1530/JOE-16-0657 PMID: 28314771. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazaris V, Hatziri A, Symeonidis A, Kypreos KE. The Lipoprotein Transport System in the Pathogenesis of Multiple Myeloma: Advances and Challenges. Front Oncol. 2021 Mar 26;11:638288. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.638288. PMID: 33842343. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang L, Li J, Fu H, Liu X, Liu P. Identification of High Serum Apolipoprotein A1 as a Favorable Prognostic Indicator in Patients with Multiple Myeloma. J Cancer. 2019 Aug 27;10(20):4852-4859. doi: 10.7150/jca.31357 PMID: 31598156. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang Y, Yang X. Prognostic Significance of Pretreatment Apolipoprotein A-I as a Noninvasive Biomarker in Cancer Survivors: A Meta-Analysis. Dis Markers. 2018 Oct 30;2018:1034037. doi: 10.1155/2018/1034037 PMID: 30510601. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palumbo A, Avet-Loiseau H, Oliva S, Lokhorst HM, Goldschmidt H, Rosinol L, et al. Revised International Staging System for Multiple Myeloma: A Report From International Myeloma Working Group. J Clin Oncol. 2015 Sep 10;33(26):2863-9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.2267. PMID: 26240224. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen T, Kristensen SR, Gregersen H, Teodorescu EM, Pedersen S. Prothrombotic abnormalities in patients with multiple myeloma and monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. Thromb Res. 2021 Jun 1;202:108–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2021.03.015 PMID: 33819778. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen S, Hansen JB, Maltesen RG, Szejniuk WM, Andreassen T, Falkmer U, Kristensen SR. Identifying metabolic alterations in newly diagnosed small cell lung cancer patients. Metabol Open. 2021 Sep 16;12:100127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metop.2021.100127 PMID: 34585134. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dona AC, Jiménez B, Schafer H, Humpfer E, Spraul M, Lewis MR, et al. Precision high-throughput proton NMR spectroscopy of human urine, serum, and plasma for large-scale metabolic phenotyping. nal Chem. 2014 Oct 7;86(19):9887-94. doi: 10.1021/ac5025039. PMID: 25180432. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez B, Holmes E, Heude C, Tolson RF, Harvey N, Lodge SL, et al. Quantitative Lipoprotein Subclass and Low Molecular Weight Metabolite Analysis in Human Serum and Plasma by 1H NMR Spectroscopy in a Multilaboratory Anal Chem. 2018 Oct 16;90(20):11962-11971. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.8b02412 PMID: 3021154. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma H, Sorokin A, Mazein A, Selkov A, Selkov E, Demin O, et al. The Edinburgh human metabolic network reconstruction and its functional analysis. Mol Syst Biol. 2007;3:135. doi: 10.1038/msb4100177 PMID: 17882155. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogata H, Goto S, Sato K, Fujibuchi W, Bono H, Kanehisa M. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999 Jan 1;27(1):29-34. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.1.29 PMID: 9847135. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanehisa M, Goto S. KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000 Jan 1;28(1):27-30. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.27 PMID: 10592173. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steiner N, Müller U, Hajek R, Sevcikova S, Borjan B, Jöhrer K, et al. The metabolomic plasma profile of myeloma patients is considerably different from healthy subjects and reveals potential new therapeutic targets. PLoS One. 2018 Aug 10;13(8):e0202045. PMID: 30096165. [PubMed]

- Mayers JR, vander Heiden MG. Nature and nurture: What determines tumor metabolic phenotypes? Cancer Res. 2017 Jun 15;77(12):3131-3134. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0165 PMID: 28584183. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieu EL, Nguyen T, Rhyne S, Kim J. Amino acids in cancer. Exp Mol Med. 2020 Jan;52(1):15-30. doi: 10.1038/s12276-020-0375-3 PMID: 31980738. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yavasoglu I, Tombuloglu M, Kadikoylu G, Donmez A, Cagirgan S, Bolaman Z. Cholesterol levels in patients with multiple myeloma. Ann Hematol. 2008 Mar;87(3):223-8. doi: 10.1007/s00277-007-0375-6 PMID: 17874102. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- abet F, Rye KA. High-density lipoproteins, inflammation and oxidative stress. Clin Sci (Lond). 2009 Jan;116(2):87-98. doi: 10.1042/CS20080106 PMID: 19076062. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang HT, Tian EB, Chen YL, Deng HT, Wang QT. Proteomic analysis for finding serum pathogenic factors and potential biomarkers in multiple myeloma. Chin Med J (Engl). 2015 Apr 20;128(8):1108-13. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.155112. PMID: 25881608. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangaraj M, Nanda R, Panda S. Apolipoprotein A-I: A Molecule of Diverse Function. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2016 Jul;31(3):253-9. doi: 10.1007/s12291-015-0513-1 PMID: 27382195. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hungria VTM, Latrilha MC, Rodrigues DG, Bydlowski SP, Chiattone CS, Maranhão RC. Metabolism of a cholesterol-rich microemulsion (LDE) in patients with multiple myeloma and a preliminary clinical study of LDE as a drug vehicle for the treatment of the disease. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2004 Jan;53(1):51-60. doi: 10.1007/s00280-003-0692-y PMID: 14574458. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Scolozzi, A Boccafogli, R Salmi, M R Furlani, C A Guidoboni, L Vicentini, M Coletti MT. Hypocholesterolemia in multiple myeloma. Inverse relation to the component M and the clinical stage. Minerva Med. 1983 Oct 20;74(40):2359-64. PMID: 6657102. [PubMed]

- Edwards CM, Zhuang J, Mundy GR. The pathogenesis of the bone disease of multiple myeloma. Bone. 2008 Jun;42(6):1007-13. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2008.01.027 PMID: 18406675. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Corral L, Gutiérrez NC, Vidriales MB, Mateos MV, Rasillo A, García-Sanz R, et al. The progression from MGUS to smoldering myeloma and eventually to multiple myeloma involves a clonal expansion of genetically abnormal plasma cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2011 Apr 1;17(7):1692-700. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1066 PMID: 21325290. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derman BA, Langerman SS, Maric M, Jakubowiak A, Zhang W, Chiu BC. Sex differences in outcomes in multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol. 2021 Feb;192(3):e66-e69. doi: 10.1111/bjh.17237. Epub 2020 Nov 20 PMID: 33216365. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).