1. Introduction

The American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) reported that the United States has more than 617,000 bridges, many exceeding 50 years in age, with 42% requiring repairs and 7.5% classified as structurally deficient [1]. This situation highlights the critical need for effective condition monitoring to maintain structural integrity. Many organizations use traditional monitoring methods that are often expensive and time-intensive, increasing interest in more innovative and efficient solutions. Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), or drones, are increasingly adopted across industries for their ability to efficiently cover and assess large infrastructure areas, providing comprehensive visual data often missed in manual inspections [2]. These capabilities accelerate evaluations and offer a cost-effective alternative to traditional approaches.

Drones provide valuable capabilities for bridge monitoring but also have notable limitations. The American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) categorized bridge inspections into eight types: initial, routine, damage, in-depth, fracture-critical, underwater, routine wading, and special inspections. Routine inspections, the most common type, primarily rely on visual methods to identify defects. While drones enhance routine inspections with their broad coverage, they are less effective in tasks requiring direct physical interaction, such as inspection of internal structural elements. Drones are also unsuited for underwater inspections and cannot detect fractures due to their lack of tactile assessments or advanced nondestructive testing [3].

Drones are particularly effective in inspecting steel and concrete structures. However, they face challenges in navigating tight spaces, capturing specific angles, and detecting subtle color changes in steel bridges. Drones cannot assess the subsurface conditions of composite and timber bridges [4]. These limitations highlight the importance of considering both inspection types and bridge materials when implementing drone technology for monitoring purposes. Hence, the most effective application of drones lies in the routine inspection of concrete and steel bridges, which is the scope of this study’s focus.

The main contribution of this study is a framework and methodology to evaluate the costs and benefits of drone-based condition monitoring (D-BCM) relative to traditional-based condition monitoring (T-BCM) of linear transportation assets. The proposed framework aims to help organizations make informed decisions regarding the adoption of drone technology by providing insights into its economic viability, potential benefits, and associated risks.

The rest of this paper proceeds as follows:

Section 2 reviews the literature on drone technology, remote sensing technologies, and quantitative modeling.

Section 3 outlines the methodology used to quantify the costs and benefits of D-BCM.

Section 4 presents the results and discusses their implications for stakeholders.

Section 5 concludes the research and suggests directions for future work.

2. Literature Review

Recent research highlights the significant benefits of drone technology in bridge inspection and monitoring. Perry et al. (2020) demonstrated the efficiency and accuracy of drones in assessing structural damage, improving both visualization and quantification [5]. Hubbard and Hubbard (2020) investigated the safety advantages of drones, quantifying these benefits through worker compensation rates and survey data from a state Department of Transportation case study [6]. Azari, O’Shea, and Campbell (2022) introduced a sensor-equipped drone prototype that enhances data collection and management processes for bridge inspections [7].

Song, Yoo, and Zatar (2022) have developed iBIRD, a web-based tool for managing drone-assisted bridge inspections, featuring 3D modeling and report generation [8]. Dorafshan and Maguire (2018) demonstrated drones equipped with self-navigation and image processing, enabling the creation of accurate, autonomous 3D models for damage identification [9]. Chen et al. (2019), however, point out the limitations of image-based methods in areas lacking distinct features [10]. Addressing environmental challenges, Aliyari et al. (2021) performed a hazard analysis on drone inspection risks under harsh conditions, focusing on human performance impacts, including drone pilots [11].

Dorafshan et al. (2017) demonstrated the effectiveness of drones in detecting damage on concrete and steel bridges, with results comparable to human inspections and the added advantage of real-time feedback. They argued that current drone technology primarily serves as an assistive tool, improving the speed, cost-efficiency, and safety of bridge inspections while eliminating the need for traffic closures [12]. Hubbard et al. (2020) investigated the role of drones in enhancing bridge inspection safety [6]. The study surveyed bridge inspectors and developed a benefit-cost methodology based on worker compensation rates to assess the safety benefits of drones. Although both studies recognize the cost and time efficiencies of drones, they lacked detailed quantification of these benefits. The present study fills these research gaps by developing a comprehensive framework to quantify the benefits and costs of using drones in bridge condition monitoring.

3. Methodology

The next subsections discuss the data mining workflow, define the variables in the framework, and explain the methods of quantifying the costs and benefits, data analysis, uncertainty management, and related simulations.

3.1. Data Mining Workflow

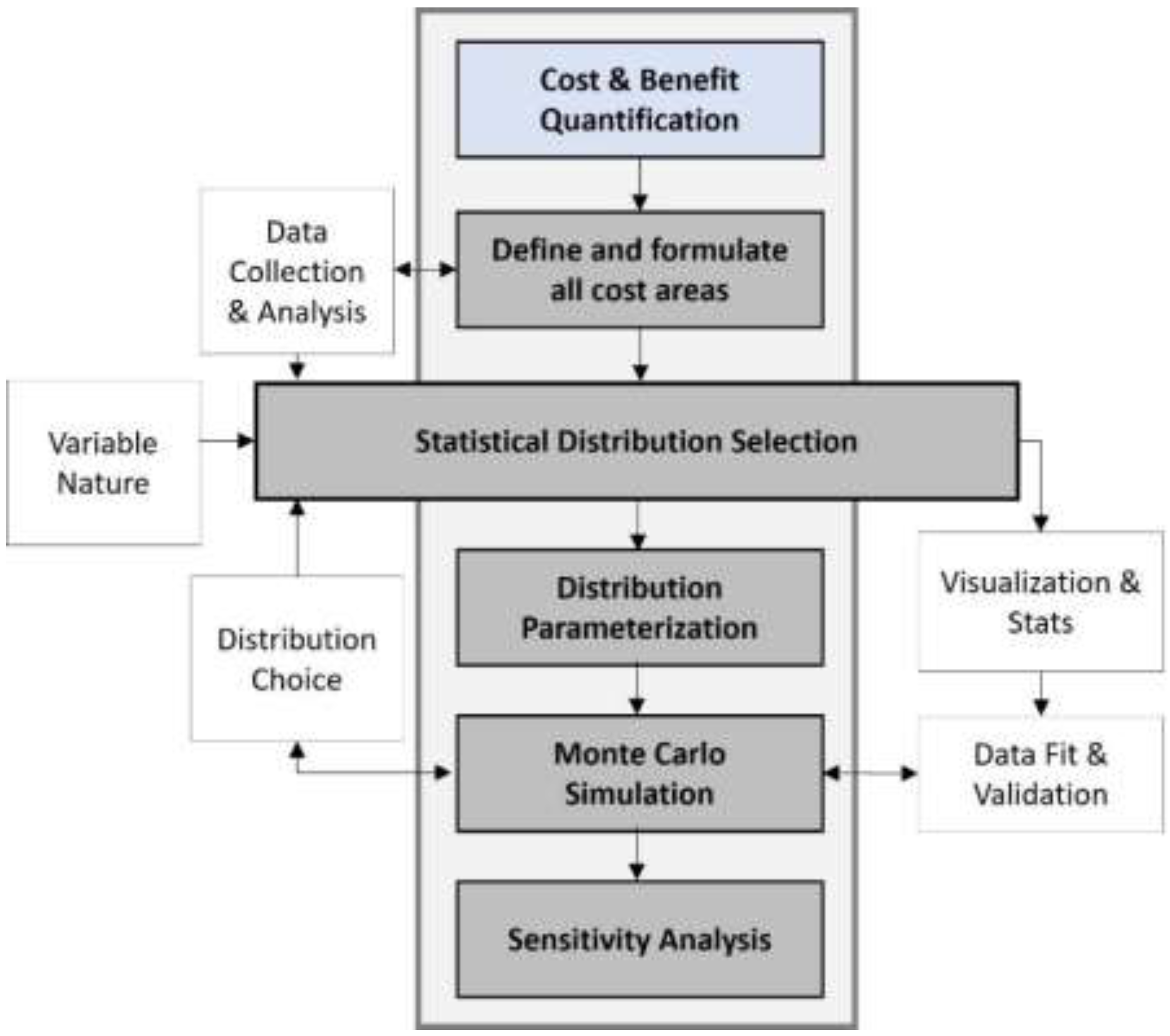

Figure 1 illustrates the data mining and analytical workflow for quantifying variables. The workflow starts by identifying the cost and benefit components of D-BCM. It then models these aspects for both drone-based and traditional methods, incorporating direct and indirect factors before formulating the overall cost-benefit structure.

Monte Carlo simulation (MCS) serves as a probabilistic forecasting tool, selecting values from a user-defined probability distribution to assess multiple model scenarios [13]. The workflow compiles data by categorizing variables as either stochastic or deterministic. Statistical models and goodness-of-fit tests fit appropriate distributions to the data. Given database uncertainties, stochastic variables undergo MCS, and results are compared with empirical data to validate accuracy. Additionally, the case study utilizes sensitivity analysis and scenario forecasting for future drone pricing trends.

3.2. Cost and Benefit Quantification

Several cost components collectively shape the economic landscape of D-BCM. As the technology progresses, components such as drone hardware, software algorithms, and operational expenses experience fluctuations. This study categorizes costs into eight groups: drone components, ground infrastructure, personnel, maintenance, IT infrastructure, data processing, insurance, and deployment. The cost model integrates these elements to quantify total costs (

Ctotal), covering acquisition, maintenance, infrastructure setup, personnel expenses, software, data processing, insurance, and regulatory fees. This structured approach ensures a transparent and systematic evaluation of the financial feasibility of D-BCM.

Table 1 presents the cost components and their sub-components used in this case study’s cost model.

The following cohesive financial model consolidates these varied costs:

Table 2 summarizes the benefit components and their sub-components used in the benefit model.

The total benefits (

Btotal) is the sum of contributions from various direct and indirect benefits as follows:

Crew time savings (

B1) result from the reduced workforce required for drone-based inspections compared with traditional methods. High-definition drone cameras minimize the need for roles such as BILT and ABI, where costs depend on the number of inspectors and their durations. Operational vehicle cost savings (

B2) stem from decreased reliance on UBIV. These savings include costs for fuel, wages, operational hours, maintenance and infrastructure expenses for vehicle facilities. Additionally, drones equipped with advanced sensors and cameras replace specialized inspection tools like gauges or ultrasonic testing devices, leading to tool cost savings (

B3).

Drone-based inspections offer significant indirect benefits, including cost savings from enhanced safety (

B4). For example, drones reduce reliance on costly safety equipment like harnesses and scaffolding. Drones also lower the risk of injuries or fatalities, which are more common in traditional methods due to hazardous conditions, fatigue, and extended work hours. This reduced risk translates into lower insurance premiums and fewer injury-related costs. Where

PF and

PI are, respectively, the likelihood of fatality and injury during inspection. According to the United States Department of Transportation (USDOT), the value of a statistical life primarily finds application in health economics, transport economics, and environmental economics.

Drones minimize the need for lane or track closures during inspections (

B5), reducing labor, equipment, and permit costs associated with disruptions. This accounts for direct lane closure costs, travel time costs, vehicle operation costs, and accident risks. By avoiding closures and delays, drones enhance operational efficiency and reduce public inconvenience.

where

DV is average delay. The Wisconsin Department of Transportation (WisDOT) data indicate that vehicles on major highways endure an average delay of 10 minutes (or 0.1667 hours) due to lane closures. In contrast, those on minor roads experience a five-minute delay (or 0.0833 hours) [14]. The value of travel time savings (

VTTS) refers to the benefits provided by reductions in the amount of time spent riding in a vehicle [15]. The values are based on USDOT hourly

VTTS values of

$17.00/person-hour for personal journeys and

$31.90/person-hour for business trips. Accounting for the customary distribution of 88.2% personal and 11.8% business travel, the result is a blended rate of

$18.76/person-hour [16]. Considering the average vehicle occupancy rates (

AVOR) of 1.48 persons per vehicle during weekday peak times and 1.58 persons per vehicle in off-peak times [16], the TTC values become

$5.10/vehicle and

$2.75/vehicle, respectively.

Further, data from the FWHA specify an average traffic volume of 1,500 vehicles per hour on major highways during peak hours and 500 vehicles per hour on minor roads in off-peak times [17]. This results in an aggregate TTCTotal of $6,915 per hour for major highways at peak times and $1,235 per hour for minor roads during off-peak hours.

3.3. Characteristics of the Variables

The framework classified the variables into deterministic and stochastic categories based on the databases and their nature to provide a clear overview of the economic factors considered.

3.3.1. Stochastic Variables

Table 3 shows the stochastic variables used in the analysis, including their time frame and data source.

Drone Price. For monitoring linear assets, multicopters are preferred, with quadcopters accounting for the majority and hexacopters making up the remaining 40% [21]. Among drone manufacturers, DJI currently leads the industry, holding over 70% of the global drone market, as reported by CNBC [22]. Aside from any governmental restrictions on manufacture origin, key considerations when selecting a drone for inspections include flight time, camera quality, weather stability, obstacle detection capabilities, and industrial-grade features [23]. Inspectors commonly use optical cameras, thermal cameras, and LiDAR systems, based on specific inspection requirements. The present study focuses on concrete and steel bridge inspections, where cameras are the most suitable payload. Table 4 provides a summary of suitable drones and their payload specifications.

Standardized Battery Price. D-BCM necessitates multiple battery replacements. The price of drone batteries varies based on type (LiPo or Li-ion), the number of batteries required, drone brand, and battery life. While some drones require only one battery, others may need up to six. This variability makes it challenging to directly compare prices. Thus, for a clear comparison of drone batteries, standardization becomes essential. This formula converts the raw battery cost into a standardized cost per flight hour.

where

FT is the battery flight time and

CC denotes the estimated number of charge cycles (approximately 300) before the LiPo battery degrades by retaining 80% of its original capacity [24, 25]. The lifespan of a Skydio X2 battery is one year or 200 battery cycles

[26]. BP is the price of battery, and

NBP is the required number of batteries for each drone.

Post-processing Time. A significant benefit of D-BCM is that it not only decreases the duration of inspections but also reduces the need for extensive crew and time spent on inspection vehicles. The Minnesota Department of Transportation (MnDOT) provided inspection time data for both traditional and D-BCM [18].

Annual Maintenance and Unexpected Repair Cost. In alignment with other electronic devices, the values for AMP and URC are 10% and 2% of the drone price [20, 19].

Software Cost. Effective D-BCM relies on specialized software for flight planning, photogrammetry, real-time monitoring, and data management. Manufacturers equip many drone models with proprietary software for flight planning and real-time monitoring, often including it in the package at no additional cost. Advanced cataloging systems, incorporating photogrammetric 3D models of bridges, enable precise identification and examination of specific bridge sections within inspection images [33].

Table 5 consolidates data from various DOT reports, showcasing commonly used software solutions and their associated costs in this field.

Insurance Cost. According to a DroneDeploy survey, most drone service providers choose liability insurance coverage of $1 million [41]. The insurance costs database lists 12 drone insurance companies for $1M coverage.

Inspection time saving percentage.Table 6 details the inspection durations for each method and lists the corresponding bridge sizes in feet [18].

Vehicle operation. Maintenance inspections for various bridge types require access to the upper or lower bridge areas, often utilizing under-bridge inspection vehicles. These specialized vehicles, equipped with articulated booms (sometimes extendable to three or four booms for enhanced reach), are available in self-propelled, truck-mounted, and trailer-mounted configurations [42]. Organizations typically rent these vehicles daily due to their high costs, often including operator services. The case study evaluates the costs associated with T-BCM by considering distinct vehicle types, their rental costs (including operators), and usage probabilities using data from MnDOT.

Table 7 details vehicle categories, costs, and probabilities.

Reduced Lane Closure. T-BCM often requires lane or road closures, increasing costs and disruptions. Temporary traffic control measures must comply with the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD) and local standards. Using equipment like UBIV requires lane closures, incurring traffic control costs ranging from

$500 to

$2,500 daily. Drone inspections reduce reliance on such equipment, minimizing lane closures and associated direct and user costs.

Table 8 presents the direct costs associated with various road closure types, based on data sourced from MnDOT

[18].

3.3.2. Deterministic Variables

Table 9 shows the deterministic variables used in the analysis and their time frame, cost, and data source.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Variables and Scenarios

4.1.1. Uncertainty and Simulations

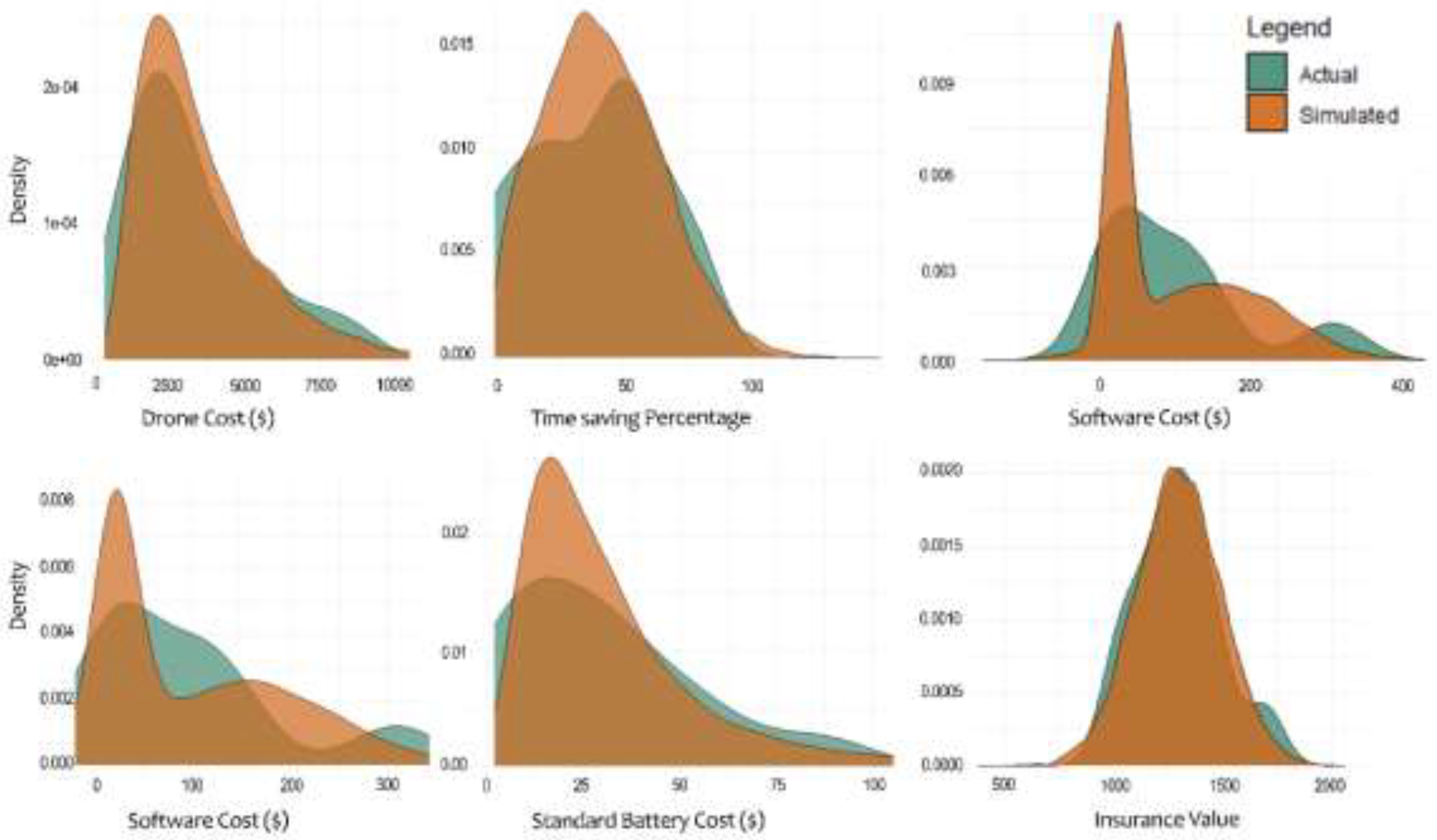

The case study employs random sampling from the probability distributions of uncertain variables to account for uncertainty in the quantitative analysis and decision-making processes involving stochastic variables. Simulated distributions are essential when actual distributions are incomplete due to derivation from limited observations. While actual distributions provide empirical insights, they often lack sufficient data points to fully capture variability and uncertainty. MCS mitigates this limitation by generating a large set of possible outcomes, enabling a more comprehensive assessment of risk and probabilistic trends. Moreover, simulated distributions facilitate sensitivity analysis, revealing how changes in input variables impact results. Comparing actual and simulated distributions ensures accurate modeling of stochastic variability, enhancing the reliability of cost-benefit assessments in D-BCM.

Figure 2 presents the results of 10,000 MCS, showing the mean, standard deviation (SD), and distribution type for each variable.

4.1.2. Sensitivity Analysis & Scenario Forecasting

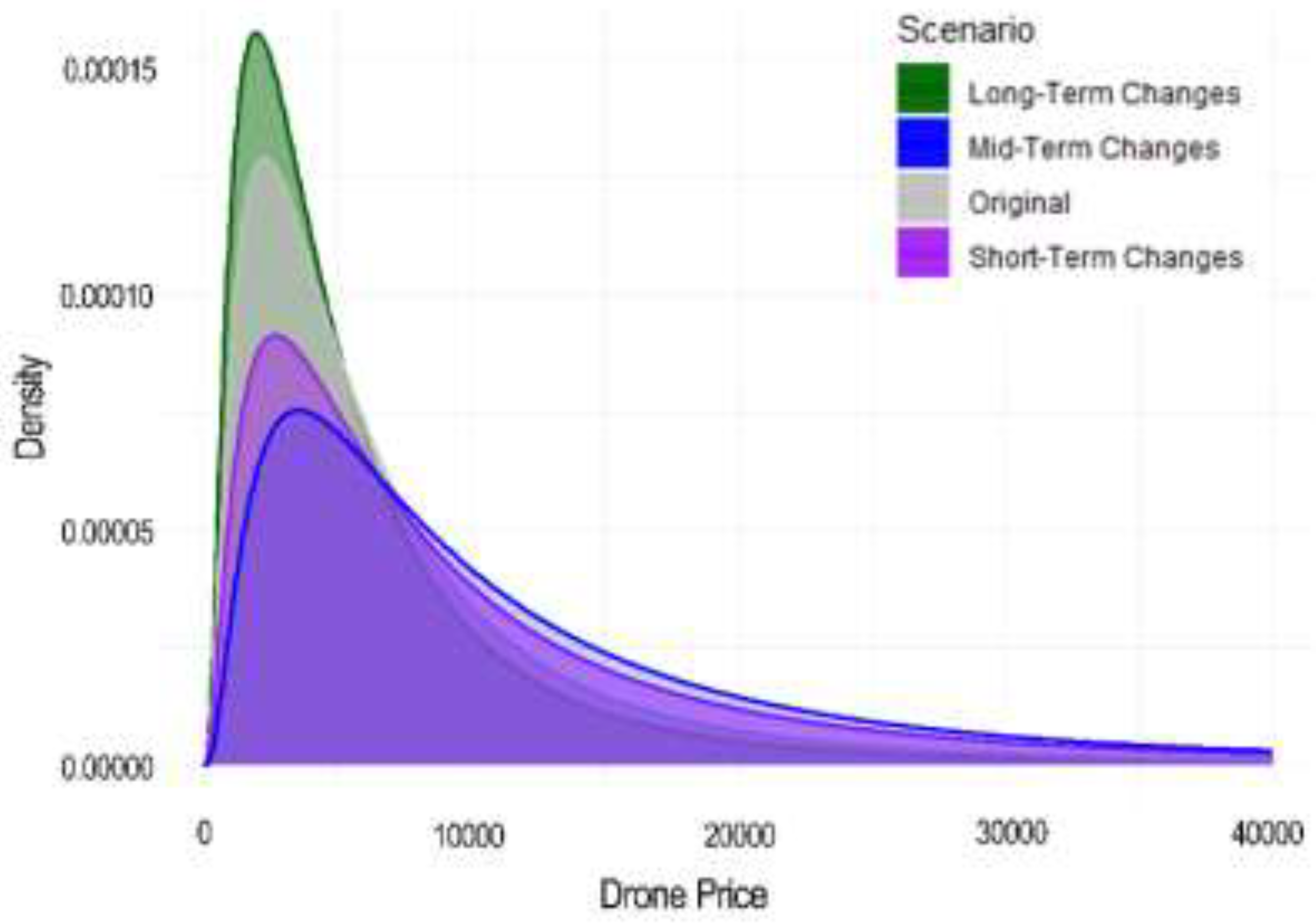

The sensitivity analysis used smartphone pricing trends as a benchmark to predict drone price evolution, assuming similar trajectories driven by technological advancements and market growth [47].

In the short term (2023–2028), the present study predicts that drones will advance in AI, autonomy, and navigation as FAA regulatory updates enable more beyond visual line of sight operations. Energy storage may improve slightly, and consumer drones will likely become more user-friendly, differentiating them from commercial models. Following smartphone pricing trends, drone prices may increase by a mean of 40% with a 20% variance.

In the mid-term (2028–2033), further AI developments and automated fleet management are anticipated, boosting drone adoption for inspections and logistics. The study expects the consumer drone market to stabilize with standardized technology and pricing, leading to a +70% mean price change and a +10% variance. By the long term (2033+), universal regulations and advanced AI autonomy will enable complex operations and broader applications, with the market maturing into diverse offerings. Analysts forecast a mean price change of -20% and a variance of -5%.

Figure 3 illustrates these trends, showing higher prices in the short and mid-term, balancing in the long term with stable, diverse options for varied needs.

4.2. Stochastic Investment Costs

The case study models the investment cost (

) using the following equation:

Here,

represents the distribution of

I, derived from 10,000 MCS.

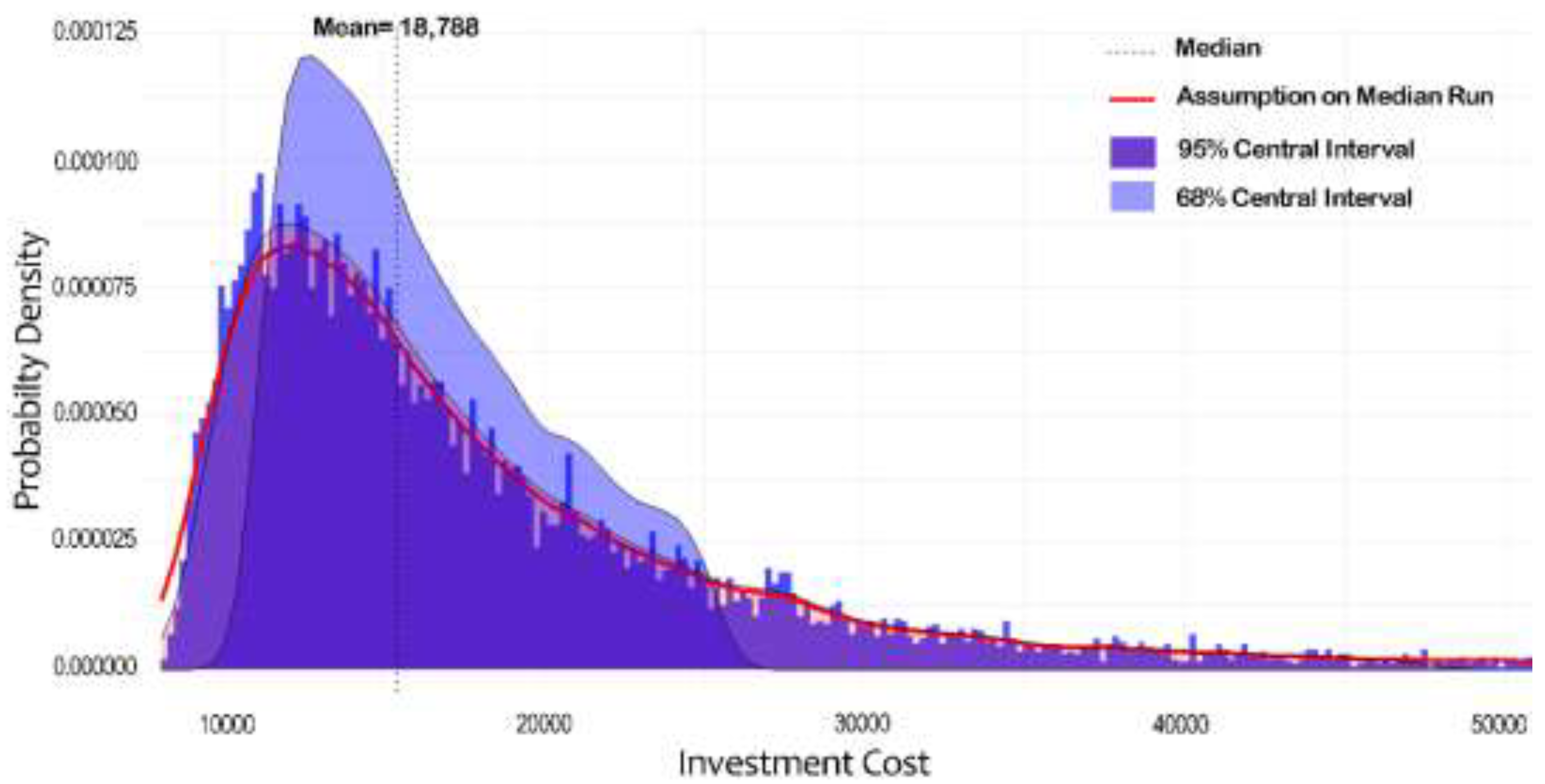

Figure 4 illustrates the empirical distribution of

I, revealing a mean cost of

$18,788.63, a median cost of

$15,483.40, and a mode of approximately

$8,124.33. The standard deviation of

$11,214.13 indicates significant cost variation, with half of the values between the 25th percentile (

$12,272.6) and the 75th percentile (

$21,362.03). The histogram displays 68% and 95% confidence intervals, highlighting likely cost boundaries. The right-skewed distribution suggests costs are more concentrated near the mode but with occasional spikes in the longer tail. Most costs fall below

$30,000, aligning with the median and providing stakeholders with reliable cost expectations.

4.3. Stochastic Cost and Benefits per Inspection

The present research used stochastic variables to model the costs per inspection for both D-BCM and T-BCM. For D-BCM, inspection costs (

DCS) depend on inspection time, data processing, and battery price, with deterministic inputs such as wages for

BILT,

ABI, and

PPE, calculated as:

For T-BCM, inspection costs (

DB) account for stochastic UBIV costs and deterministic variables, calculated as:

The analysis used MCS to compare cost distributions for both methods.

Figure 5 shows the results, with D-BCM demonstrating a median cost of

$1,770, significantly lower than T-BCM’s

$7,216. Quartile values reinforce this trend: D-BCM costs remain below T-BCM across all percentiles, peaking at

$4,870 compared with

$9,716.

The standard deviation for D-BCM is $653.85, indicating more consistent costs than T-BCM with $1,258.37. Kurtosis values highlight differences in distribution shapes, with D-BCM showing a leptokurtic distribution (3.01), while T-BCM displays a platykurtic one (2.39). The 95% confidence interval further emphasizes the advantage of D-BCM, with costs likely between $532.81 and $3,117.12, compared with between $5,216.5 and $9,716.5 for T-BCM.

The findings illustrate the financial superiority of D-BCM, offering lower and more predictable costs. Hence, adopting D-BCM can provide substantial savings, particularly for large-scale or recurring inspections.

4.4. Net Saving

Net savings distribution (

DNS) reflect the cost difference between T-BCM and D-BCM, calculated as:

MCS reveal an average net savings of $5,043 per inspection, with a median of $4,935. Most outcomes fall between the 1st quartile ($3,997) and the 3rd quartile ($5,983), with a maximum saving of $9,271. Variability, indicated by a standard deviation of $1,435.83, remains moderate. The dataset exhibits a skewness of 0.243 and a kurtosis of 2.5, indicating a slightly right-skewed distribution with fewer outliers. The 95% confidence interval, ranging from $2,512.42 to $7,912.54, highlights consistent financial advantages of drone-based methods.

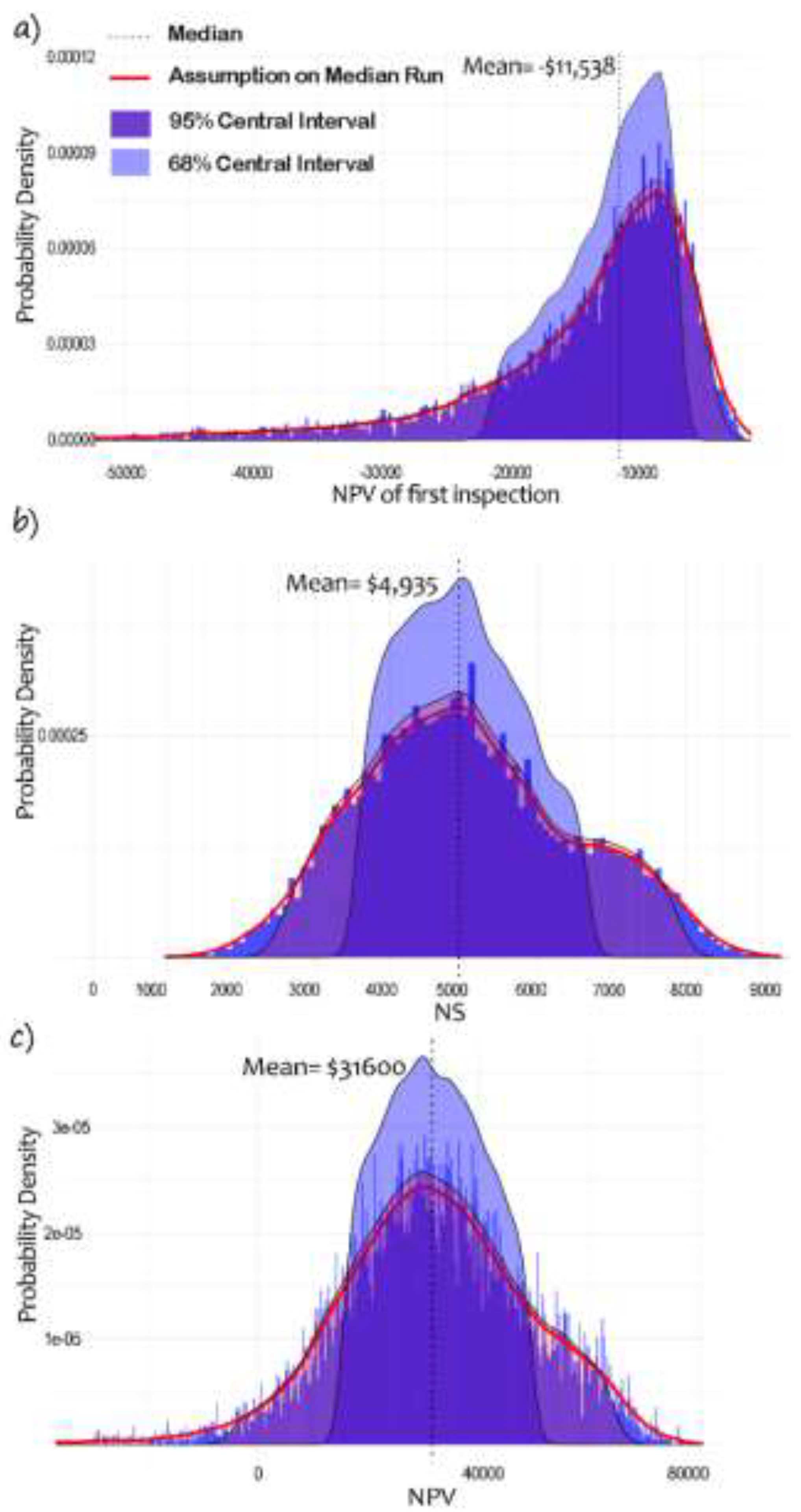

4.5. Net Present Value

The net present value (NPV) distribution (

DNPV of First Inspection) for the first inspection combines investment, cost, and benefit distributions:

The first inspection yields a median NPV of -

$11,538, with a significant standard deviation of

$13,157.72 and a left-skewed distribution (skewness: -4.03). The 95% confidence interval (-

$43,833 to -

$4,275) confirms predominantly negative NPVs initially. Annual NPV analysis for 10 inspections shows a shift to positive returns, calculated as:

The average annual NPV increases to

$31,600, with reduced variability (SD:

$12,849.6) and a symmetric distribution (skewness near zero). The confidence interval (

$45,481 to

$64,569) emphasizes the long-term financial benefits of D-BCM, highlighting their cost-effectiveness as cumulative inspections offset initial expenses.

Figure 6 compares the distribution of NS, NPV of the first inspection, and NPV of 10

th inspection.

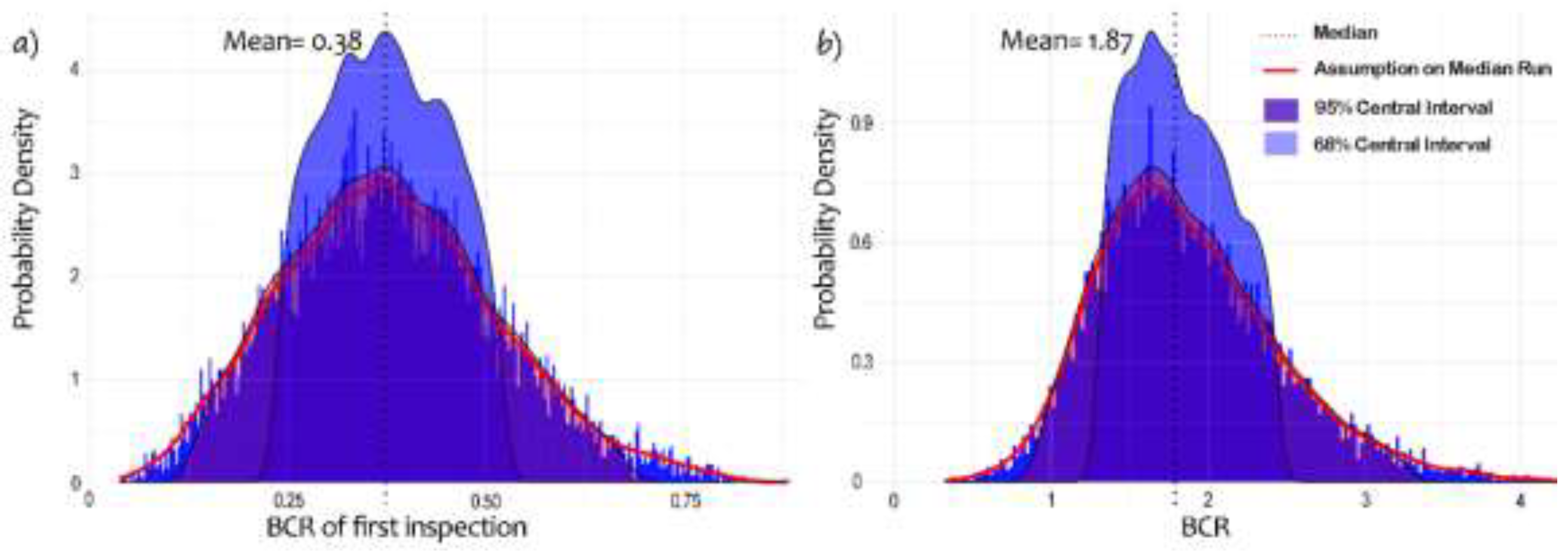

4.6. Benefit Cost Ratio

Figure 7 compares the benefit cost ratio (BCR) distribution (

DBCR of first Inspection) for the initial and 10

th inspections, calculated as:

In first inspection the distribution is unimodal with a slight rightward skew, as the mean (0.38) exceeds the median (0.37) and a skewness of 0.31. Most values cluster near the mean within the 68% interval, while the 95% interval captures broader variability. The model aligns well with observed data, as shown by the red curve matching the median.

The distribution for the 10th inspection shows a similar unimodal shape but with increased skewness (0.89), as the mean (1.87) surpasses the median (1.79). Greater variability is evident, with a standard deviation of 0.60 compared with 0.13 for the first inspection. The 95% interval expands from [0.13, 0.68] to [0.91, 3.28], indicating growing uncertainty over time.

The skewness and variability of the BCR increase from the first to the 10th inspection, reflecting greater potential for high or varied BCR values. This trend suggests that repeated inspections yield a broader range of benefit-cost outcomes, driven by changes in costs, benefits, or both.

4.7. Cost-Benefit Measures

The NPV calculates the difference between current benefits (

Bi) and costs (

Ci) over a specific timeframe, indicating cost-effectiveness. A positive NPV signifies profitability, while a negative value suggests otherwise. Among multiple alternatives with positive NPVs, the option with the highest value yields the greatest return. The NPV formula is:

Here,

r is the discount rate,

i is the year, and

Y is the total payback period.

Bi includes benefits such as reduced lane closures, improved safety, and cost savings from T-BCM. Costs (

Ci) are derived as:

where

I is the investment cost (

),

is the inspection cost

), and

CV is the monthly deployment cost (

).

The BCR measures the ratio of benefits to costs. A BCR above 1 indicates cost-effectiveness, with higher values denoting greater returns. For multiple alternatives, the option with the highest BCR is preferred. The BCR formula is:

The USDOT (2023) recommends using a real discount rate of 7% per year to discount monetized benefits and costs to their present value, excluding inflation effects [16]. This case study adopts a 10-year duration, reflecting the anticipated operational lifespan of current drone technologies [48].

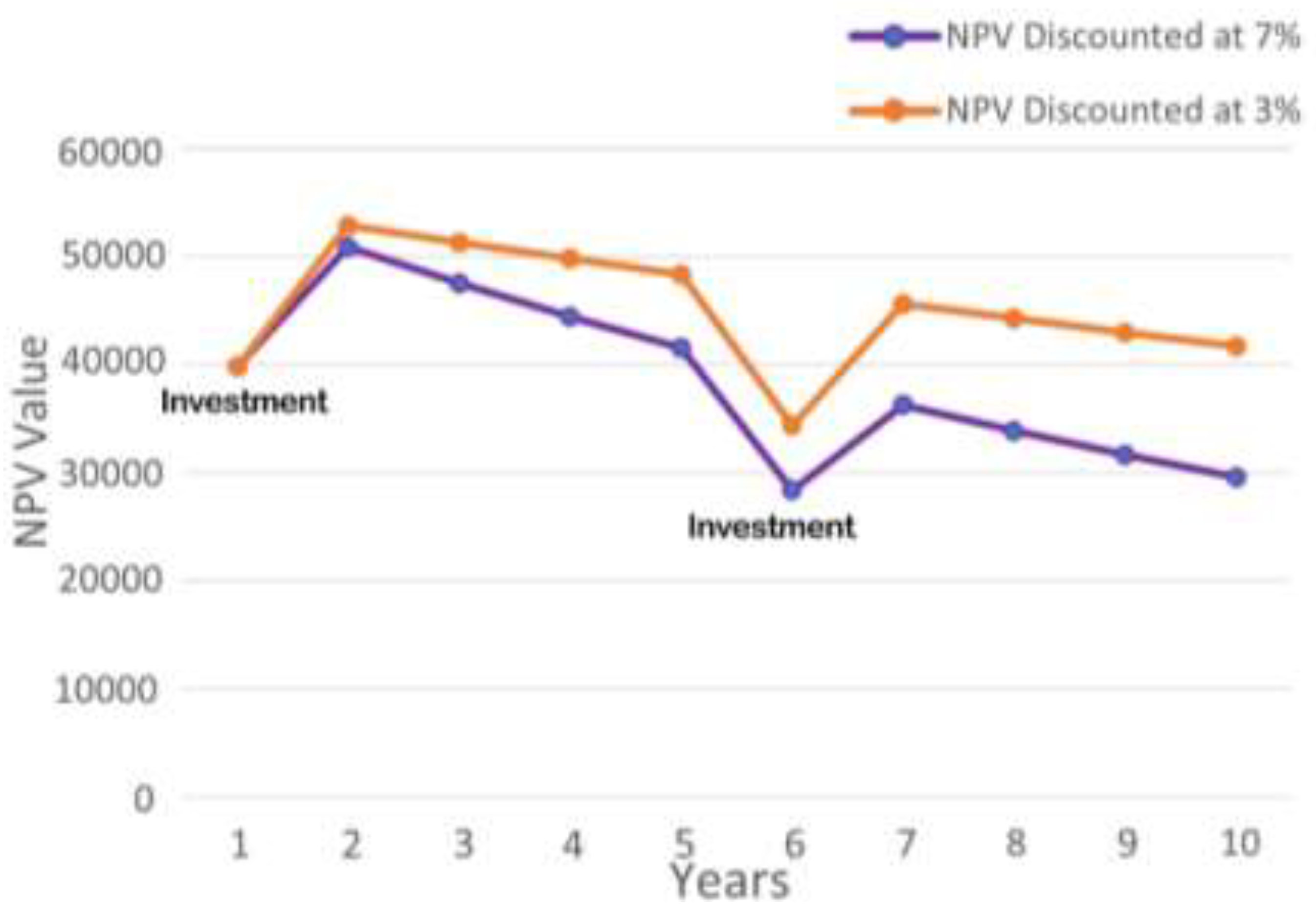

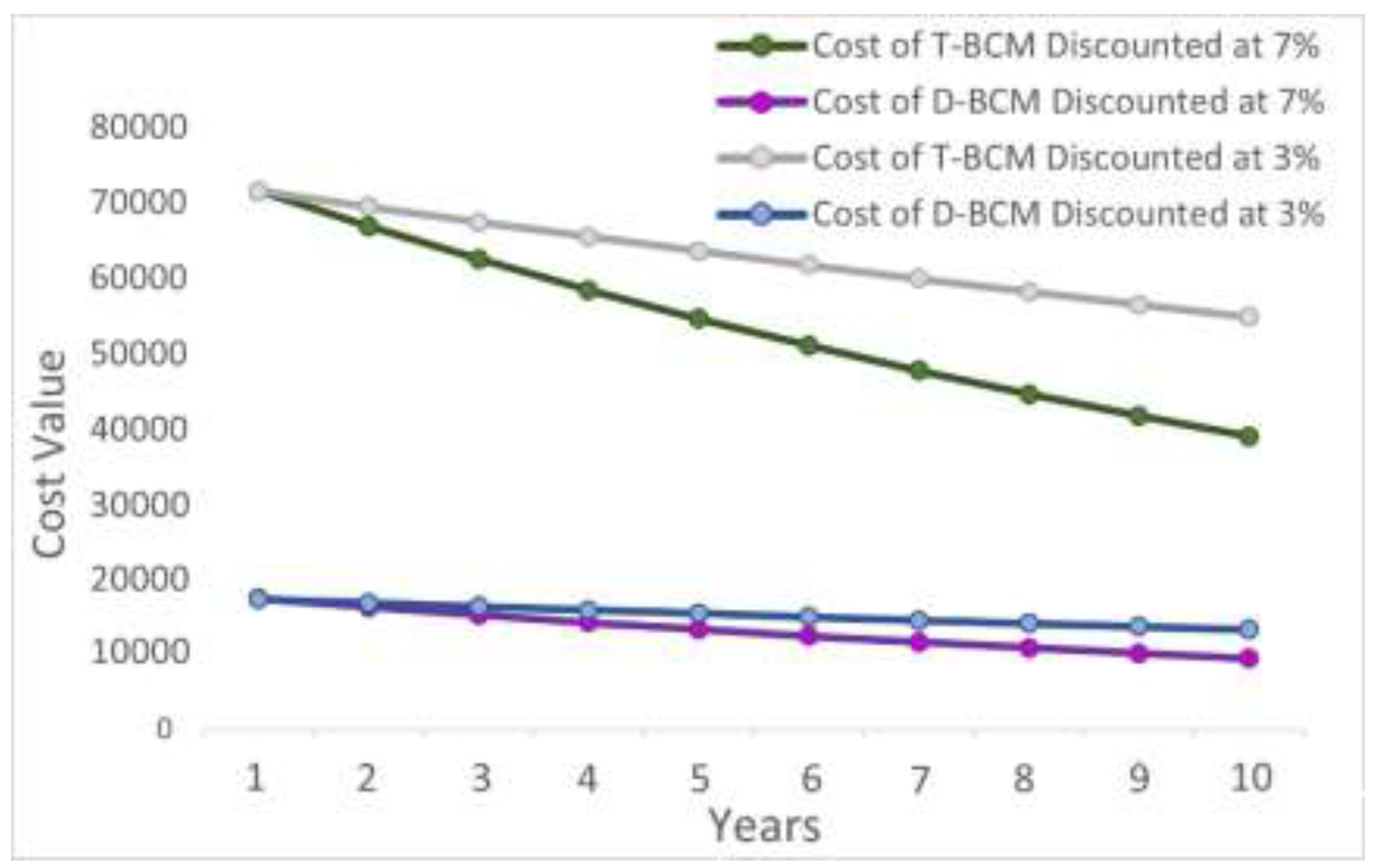

4.8. Case Scenario

This scenario assumes an eight-hour traditional inspection time. The simulation identified a 75% reduction in inspection time (ITSP), reducing drone-based inspection time to two hours.

Table 10 shows that the initial costs for D-BCM is

$14,605.99, compared with

$1,528.78 for T-BCM. The NPV for the first inspection is negative (-

$9,011.45), and the BCR is 0.44, indicating non-cost-effectiveness at the outset. However, cumulative NPV turns positive after the second inspection, as shown in

Table 11.

The analysis evaluates 10 inspections annually over a 10-year period with 3% and 7% discount rates. The five-year lifespan of drones requires two investments. At both rates, the first-year NPV is

$39,797, with BCRs of 2.27 for investment years and 4.23 for subsequent years (

Table 12 and

Table 13).

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 highlight the cost advantage of D-BCM, which consistently outperforms traditional methods. The savings grow significantly under a 7% discount rate, demonstrating greater cost efficiency for D-BCM over time.

4.9. Sensitivity Analysis

Based on the 15-year changes in drone prices discussed earlier, this scenario adjusts drone prices in the investment component every five years. Additionally, the model re-simulates all stochastic variables every five years using MCS to generate new random values. However, benefits, costs, and inspection durations—eight hours for T-BCM and two hours for D-BCM—remain constant.

Table 14 presents the sensitivity analysis of NPV and BCR values, highlighting the financial feasibility of drone investments. A negative NPV and a BCR below 1 indicate that the initial investment may not yield immediate returns.

Table 15 highlights the downward trend of NPV over time. This suggests limited gains initially but improved outcomes with sustained drone use. The sixth year shows a significant dip, with the mid-term drone purchase yielding a more negative NPV, reducing profitability. However, in the long term, the NPV improves and the BCR approaches 0.4, driven by lower drone prices.

The 15-year sensitivity analysis of drone prices provides insight into the economic impact of adopting drone technology. Although initial investments may not yield immediate profits, consistent benefits and long-term cost reductions can make the initiative economically viable. Hence, balancing upfront costs with long-term gains and strategic opportunities is essential.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights the economic benefits of drone-based monitoring for bridge inspections by presenting a comprehensive framework to evaluate its cost-efficiency and effectiveness. Although initial investments may pose challenges due to startup costs, the findings highlight substantial long-term financial advantages, including reduced inspection times, enhanced safety, and decreased operational disruptions. Sensitivity analyses reveal the potential for cost reductions driven by technological advancements, with improvements in NPVs and BCRs over time. This analysis further shows that by balancing upfront expenditures with sustained savings, drone technology becomes a viable and strategic solution for improving the efficiency and reliability of linear transportation asset monitoring. Future work will update the analysis based on survey data and apply the framework to other types of transportation assets.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.A. and R.B.; methodology, T.A. and R.B.; software, T.A.; validation, T.A. and R.B.; formal analysis, T.A.; investigation, T.A. and R.B.; resources, R.B.; data curation, T.A.; writing—original draft preparation, T.A.; writing—review and editing, T.A. and R.B.; visualization, T.A. and R.B.; supervision, R.B.; project administration, R.B.; funding acquisition, R.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received funding from the United States Department of Transportation, Center for Transformative Infrastructure Preservation and Sustainability (CTIPS), Funding Number 69A3552348308.

Data Availability Statement

This article includes the data presented in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- ASCE, "Report Card for America's Infrastructure," ASCE, 2021.

- Askarzadeh, T.; Bridgelall, R.; Tolliver, D. Drones for Road Condition Monitoring: Applications and Benefits. Journal of Transportation Engineering, Part B: Pavements 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AASHTO, "The Manual For Bridge Evaluation Second Edition," American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials, 2011.

- J. Seo, L. Duque and J. Wacker, "Drone-enabled bridge inspection methodology and application," Civil Engineering, 2018.

- B. J. Perry, Y. Guo, R. Atadero and J. W. Van De Lindt, "Streamlined bridge inspection system utilizing unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and machine learning," Measurement: Journal of the International Measurement Confederation, vol. 164, 2020.

- B. Hubbard and S. Hubbard, "Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS) for Bridge Inspection Safety," Drones, vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 1-18, 2020.

- H. Azari, D. O’Shea and J. Campbell, "Application of Unmanned Aerial Systems for Bridge Inspection," Transportation Research Record, vol. 2676, no. 1, pp. 401-407, 2022.

- H. Song, W.-S. Yoo and W. Zatar, "Interactive Bridge Inspection Research using Drone," in COMPSAC 2022, 2022.

- S. Dorafshan and M. Maguire, "Bridge inspection, human performance, unmanned aerial systems and automation," Journal of Civil Structural Health Monitoring, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 443-476, 2018.

- S. Chen, D. F. Laefer, E. Mangina, I. S. Zolanvari and J. Byrne, "UAV Bridge Inspection through Evaluated 3D Reconstructions," Journal of Bridge Engineering, vol. 24, no. 4, 2019.

- M. Aliyari, B. Ashrafi and Y. Z. Ayele, "Drone-based Bridge Inspection in Harsh Operating Environment: Risks and Safeguards," International Journal of Transport Development and Integration, vol. 5, no. 2, p. 118–135, 2021.

- S. Dorafshan, M. Maguire, N. V. Hoffer and C. Coopmans, "Challenges in bridge inspection using small unmanned aerial systems: Results and lessons learned," in International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS), Miami, FL, USA, 2017.

- J. Mun, Modeling Risk, Applying Monte Carlo Risk Simulation, Strategic Real Options, Stochastic Forecasting, and Portfolio Optimization, 2010.

- WisDOT, "General Lane Closure Impact Analysis," 2020.

- B. J. Glover, "2021 URBAN MOBILITY REPORT," Texas A&M Transportation Institute, 2021.

- USDOT, "Benefit cost analysis guidance for discretionary grant programs," U.S. Department of Transportation, 2023.

- FHWA, "Traffic Data Computation Method Pocket Guide. Publication No. FHWA-PL-18-027," FHWA, 2018.

- J. Wells and B. Lovelace, "Improving the Quality of Bridge Inspections Using Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS)," Minnesota Department of Transportation, 2018.

- H. Lofsten, "Measuring maintenance performance in search for a maintenance productivity index," International Journal of Production Economics, vol. 63, pp. 47-58, 2000.

- R. Dunn, "Advanced maintenance technologies,," Plant Engineering, vol. 40, pp. 80-82, 1987.

- T. Askarzadeh, R. Bridgelall and D. D. Tolliver, "Systematic Literature Review of Drone Utility in Railway Condition Monitoring," Journal of Transportation Engineering, Part A: Systems, 2023.

- N. Anwar, "World’s largest drone maker is unfazed — even if it’s blacklisted by the U.S.," 07 02 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.cnbc.com/2023/02/08/worlds-largest-drone-maker-dji-is-unfazed-by-challenges-like-us-blacklist.html. [Accessed 01 06 2023].

- T. Askarzadeh, R. Bridgelall and D. Tolliver, "Monitoring Nodal Transportation Assets with Uncrewed Aerial Vehicles: A Comprehensive Review," Drones, 2024.

- T. Bradbury, "The Drone Girl," 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.thedronegirl.com/2020/05/24/lipo-batteries-last/.

- J. Castro, C. Flores, D. Gonzalez, V. Quintero and A. Perez, "From the Air to the Ground: An Experimental Approach to Assess LiPo Batteries for a Second Life," in Prognostics and Health Management Conference (PHM-2022 ), London, 2022.

- Skydio, "Skydio," 20 7 2023. [Online]. Available: https://support.skydio.com/hc/en-us/articles/1260804644430-How-to-charge-and-maintain-your-Skydio-X2-batteries. [Accessed 27 9 2023].

- DJI, "Consumer Drones Comparison," 1 8 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.dji.com/products/comparison-consumer-drones. [Accessed 2023].

- Parrot., "ANAFI Ai Photogrammetry," 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.parrot.com/us/drones/anafi-ai/technical-documentation/photogrammetry. [Accessed 2 8 2023].

- Yuneec., "Yuneec a Company of ATL Drones," 2023. [Online]. Available: https://yuneec.online/e30z/. [Accessed 4 8 2023].

- RMUS Unmanned Solutions., "Flyability Elios 3," 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.rmus.com/products/flyability-elios-3. [Accessed 15 7 2023].

- DJI Inspire, "DJI Inspire 3," 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.dji.com/inspire-3. [Accessed 27 8 2023].

- Autelrobotics, "Go Beyond The Boundaries Of Aerial Photography," 2023. [Online]. Available: https://shop.autelrobotics.com/collections/autel-evo-ii-series. [Accessed 29 8 2023].

- W. Helmi, R. Bridgelall and T. Askarzadeh, "Remote Sensing and Machine Learning for Safer Railways: A Review," Applied Sciences, 2024.

- D. T. Gillins, C. Parrish, M. N. Gillins and C. Simpson, "EYES IN THE SKY: BRIDGE INSPECTIONS WITH UNMANNED AERIAL VEHICLES," Oregon DOT, Washington DC, 2018.

- Michael Baker International, "UAS Bridge Inspection Pilot," Wisconsin Department of Transportation, 2017.

- J. O’Neil-Dunne, "Unmanned Aircraft Systems for Transportation Decision Support," U.S. Department of Transportation, 2016.

- Zajkowski, Tom; Snyder, Kyle; Arnold, Evan; Divakaran, Darshan, "Unmanned Aircraft Systems: A New Tool for DOT Inspections," NCDOT, NC, 2016.

- S. Dorafshan, H. N. V. Maguire and C. Coopmans, "Fatigue Crack Detection Using Unmanned Aerial Systems in Under-Bridge Inspection," Idaho Transportation Department, 2017.

- J. A. Bridge, P. G. Ifju, T. Whitley and A. P. Tomiczek, "Use of Small Unmanned Aerial Vehicles for Structural Inspection," Florida Department of Transportation, 2018.

- J. M. Burgett, D. C. Bausman and G. Comert, "Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS) Impact on Operational Efficiency and Connectivity," U.S. DOT., 2019.

- DroneDeploy, "Drone Insurance and Liability Coverage: Do You Need It?," 17 01 2018. [Online]. Available: https://www.dronedeploy.com/blog/drone-insurance-and-liability-coverage-do-you-need. [Accessed 02 10 2023].

- FHWA BIRM, "Bridge Inspector’s Reference Manual (BIRM)," FHWA, 2023.

- M. Lau Banh, A. Foina, D. Li, Y. Lin, X. A. N. Redondo, C. Shong and W.-B. Zhang, "Evaluation of Feasibility of UAV Technologies for Remote Surveying BART Rail Systems," Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART), 2017.

- FAA, "FAA," 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.faa.gov/faq/how-much-does-it-cost-get-remote-pilot-certificate. [Accessed 27 09 2023].

- USDOT, "Departmental Guidance Treatment of the Value of Preventing Fatalities and Injuries in Preparing Economic Analyses," 2021.

- MnDOT, "Bridge Inspectors Reference Manual," 2012.

- M. Cordella, F. Alfieri and J. Sanfelix, "Guidance for the Assessment of Material Efficiency: Application to Smartphones," Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2020.

- P. Cohn, A. Green, M. Langstaff and M. Roller, "Commercial drones are here: The future of unmanned aerial systems," 2017. [Online]. Available: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/travel-logistics-and-infrastructure/our-insights/commercial-drones-are-here-the-future-of-unmanned-aerial-systems#/.

Figure 1.

Figure 1. Workflow for quantifying the variables.

Figure 1.

Figure 1. Workflow for quantifying the variables.

Figure 2.

Comparing actual and simulated distributions of stochastic variables, their distribution type, mean, and SD.

Figure 2.

Comparing actual and simulated distributions of stochastic variables, their distribution type, mean, and SD.

Figure 3.

Histograms of sensitivity analysis of DP.

Figure 3.

Histograms of sensitivity analysis of DP.

Figure 4.

Distribution of investment cost.

Figure 4.

Distribution of investment cost.

Figure 5.

Distribution of D-BCM and T-BCM cost per inspection.

Figure 5.

Distribution of D-BCM and T-BCM cost per inspection.

Figure 6.

Distribution of a) NPV of the first inspection, b) net saving, c), and NPV of 10th inspection.

Figure 6.

Distribution of a) NPV of the first inspection, b) net saving, c), and NPV of 10th inspection.

Figure 7.

The BCR distribution of a) the first and b) 10th inspections.

Figure 7.

The BCR distribution of a) the first and b) 10th inspections.

Figure 8.

Ten-Year NPV projection comparing 3% and 7% discount rates.

Figure 8.

Ten-Year NPV projection comparing 3% and 7% discount rates.

Figure 9.

Comparative 10-year cost analysis of T-BCM and D-BCM at 3% and 7%.

Figure 9.

Comparative 10-year cost analysis of T-BCM and D-BCM at 3% and 7%.

Table 1.

Variables used in the cost model.

Table 1.

Variables used in the cost model.

| Cost components |

Variable |

Description |

| Drone Component Costs (C1) |

|

Number of drones |

|

Cost of a drone |

|

Number of payloads (e.g., cameras, sensors) |

|

Number of standardized batteries |

|

Cost of a payload |

|

Cost of a standardized battery |

| Ground Infrastructure Costs (C2) |

|

Cost of the ground control station |

|

Cost of ground landing pads |

| Personnel Costs (C3) |

|

Time required for the bridge inspection team leader (BILT) |

|

Time required for assistant bridge inspectors (ABI) |

|

Number of ABI |

|

Cost of a drone pilot |

|

Number of drone pilots |

|

Training costs for personnel |

| Upkeep Costs (C4) |

|

Annual maintenance costs |

|

Unexpected repair costs |

| IT Infrastructure Costs (C5) |

|

Number of software licenses required |

|

Cost of software licenses |

|

Cost of data storage |

| Data Processing Costs (C6) |

|

Cost of post-processing engineers |

|

Number of post-processing engineers |

|

Time required for post-processing engineers |

| Insurance Costs (C7) |

|

Cost of liability insurance |

|

Cost of hull insurance |

|

Number of insured equipment units |

| Deployment Costs (C8) |

|

Cost of registration fees |

|

Number of registered drones |

Table 2.

Variables used in the benefit model.

Table 2.

Variables used in the benefit model.

| Benefit Components |

|

Variable |

Variable Explanation |

| Crew Time Savings (B1) |

|

|

Time required for the BILT |

| |

|

Number of assistant inspectors |

| |

|

Time required for assistant inspectors |

| Operational Vehicle Cost Savings (B2) |

|

UBIV |

Cost of under-bridge inspection vehicles (UBIV) |

| |

|

Time required for UIBV |

| |

|

Number of UIBV |

| |

|

Maintenance costs of UIBV |

| |

|

Infrastructure costs associated with UIBV |

| Tool Cost Savings (B3) |

|

|

Number of inspection tools replaced by drones |

| |

|

Cost of traditional monitoring tools |

| Safety Cost Savings (B4) |

|

ISE |

Cost savings from reduced use of safety equipment |

| |

|

Risk reduction costs |

| |

VSL |

Value of a statistical life |

| |

|

Probability of fatality during inspections |

| |

VSI |

Value of a statistical injury |

| |

|

Probability of injury during inspections |

| Reduced Lane Closure & Traffic Costs (B5) |

|

LCC |

Lane closure costs |

| |

|

Total travel time cost savings |

| |

AVOR |

Average vehicle occupancy rates |

| |

VOC |

Vehicle operation cost savings |

| |

OP |

Operating cost per mile |

| |

AMTD |

Annual miles traveled |

| |

|

Reduced accident risks and associated cost savings |

Table 3.

The stochastic variables.

Table 3.

The stochastic variables.

| Variable |

Description |

Time Frame |

Source |

| DP |

Drone price |

Once |

Market |

| SBP |

Standardized battery price |

Hour |

Market |

| TPPE |

Time of preprocessing engineer |

Inspection |

[18] |

| AMC |

Annual maintenance cost |

Year |

[19] |

| URC |

Unexpected repair cost |

Year |

[20, 19] |

| CSoft |

Software cost |

Month |

Market |

| LI |

Liability insurance cost |

Year |

Market |

| ITSP |

Inspection time saving percentage |

% |

[18] |

| VO |

Operational vehicle |

Daily |

|

| LCC |

Lane closure cost |

Hour |

|

Table 4.

Recommended drones and their payload for D-BCM.

Table 4.

Recommended drones and their payload for D-BCM.

| Drone |

Price |

Flight Time (Min) |

Built-in Payload |

Extra Required Payload |

Data Source |

| DJI Mavic 3 Pro |

$2,199 to $3,299 |

43 |

Hasselblad: 4/3 CMOS, 20 MP Medium Tele: 1/1.3-inch CMOS, 48 MP Tele: 1/2-binch CMOS, 12 MP |

- |

[27] |

| DJI Air 3 |

$1,099 to 1,550 |

46 |

Wide-Angle:1/1.3-inch CMOSEffective Pixels: 48 MP Medium Tele:1/1.3-inch CMOSEffective Pixels: 48 MP |

- |

| DJI Phantom 4 Pro |

$1,599 to $1,699 |

30 |

1” CMOSEffective Pixels: 20 MP |

- |

| DJI Matrice 600 Pro |

$5,000 to $6,000 |

32 |

- |

Zenmuse (Z) X3: 1/2.3” CMOS/12 MP photos and 4K video at 30fps:$500 – $700ZX5 & X5R:$1,400 – $1,600/ $3,000ZX7: $2,700 – $3,000 Z30: $2,500 – $4,000. |

| DJI Matrice 300 RTK |

$13,000 |

55 |

Infrared Sensing System |

ZH20 series: hybrid multi-sensor camera $5,000 to $10,000ZP1: full-frame sensor camera: $8,000 |

| MATRICE 210 RTK V2 |

$10,000 to $15,000 |

34 |

- |

Z30: $2,500 – $4,000.ZX4S: $600 – $800.ZX5S: t $1,900 – $2,200.ZX7: $2,700 – $3,000 ZXT2 |

| Skydio 2+ |

$5,000 |

27 |

Camera: Sony IMX577 CMOS sensor and Qualcomm RedDragon™ QCS605: 12 MP photos,4K60 HDR video/45 MP |

- |

[26] |

| Skydio X10 |

$15,000 |

40 |

Narrow camera: 64 MP 1” wide camera: 50 MP Radiometric thermal: 640x512 px |

- |

| Parrot Anafi |

$7,000 |

32 |

Vertical camera, ultra-sonar/ 2x6-axis IMU, 2x3-axis accelerometers, 2x3-axis gyroscopes, 4k video, thermal |

- |

[28] |

| Yuneec H520E |

$2,500 |

28 |

- |

E90 Camera: 1-inch CMOS sensor, 20 MP resolution. $1,299 – $1,499.E50 Camera: $1,200CGOET Camera: $1,900 |

[29] |

| Elios 3 |

$5,000 |

12 |

Visual camera and onboard LED lighting capable of 4K UHD videos. CMOS Effective Pixels: 12.3 |

- |

[30] |

| DJI Inspire 3 |

$16,500 |

28 |

X9-8K Air |

- |

[31] |

| AUTEL EVO 2 PRO RTK |

$1,500 – $3,000 |

40 |

1-inch CMOS |

- |

[32] |

Table 5.

Software cost used by DOTs for D-BCM.

Table 5.

Software cost used by DOTs for D-BCM.

| Software |

Price Range |

DOT |

| Photogrammetry |

|

|

| Pix4D |

$32 – $291/month |

[18] [34][35] [36] [37] |

| Agisoft Metashape |

$179 – $3,500 (one-time) |

[38] [39] [37] |

| AutoCAD |

$40/month |

[18][35] |

| ContextCapture |

$3,900/year |

[18][40] |

| Data Management |

|

|

| Airdata UAV |

Free to $300/year |

- |

| Dronelogbook |

$10/month |

- |

| Intel Insight |

$99/month |

[18] |

Table 6.

Comparison of inspection hours for D-BCM and T-BCM.

Table 6.

Comparison of inspection hours for D-BCM and T-BCM.

| T-BCM |

D-BCM |

BS (feet) |

| TBILT |

TABI |

TUBIV |

TBILT |

TABI |

|

| 8 |

8 |

0 |

4 |

4 |

505 |

| 4 |

4 |

0.5 |

1 |

1 |

2,740 |

| 4 |

4 |

0 |

4 |

4 |

45 |

| 8 |

8 |

0 |

4 |

4 |

1,887 |

| 24 |

24 |

3 |

20 |

20 |

635 |

| 8 |

8 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

214 |

| 8 |

8 |

0 |

6 |

6 |

3,360 |

| 12 |

12 |

0 |

6 |

6 |

160 |

| 4 |

4 |

0.5 |

3 |

3 |

1,914 |

| 4 |

4 |

1 |

4 |

4 |

2,100 |

| 8 |

8 |

0 |

4 |

4 |

2,769 |

Table 7.

Inspection vehicles for T-BCM, their associated costs, and usage probabilities.

Table 7.

Inspection vehicles for T-BCM, their associated costs, and usage probabilities.

| Vehicle with Operator |

Probability |

Daily Rental ($) |

Type of Inspection |

| Snooper Truck |

30% |

$3,000 |

Under-bridge access |

| Bucket Truck |

40% |

$700 |

Mainly used for overhead inspections where direct access is required at a certain height. Effective for bridge superstructure elements. |

| Scissor Lift |

15% |

$500 |

Where vertical elevation is required without the need for lateral movement. Primarily used for low-height under-bridge areas or decks. |

| Boom Lift |

25% |

$1,000 |

For both vertical and horizontal movement, facilitating access to difficult areas of a bridge, especially for superstructure elements. |

Table 8.

Direct costs per day for various road closure types.

Table 8.

Direct costs per day for various road closure types.

| Category |

Cost ($) |

| Misc. Traffic Control (Ped. Only, Etc.) |

$500 |

| Low Speed Lane/Shoulder Closure |

$2,000 |

| Mobile Lane/Shoulder Closure |

$1,500 |

| High Speed Lane/Shoulder Closure |

$2,500 |

Table 9.

The Deterministic Variables.

Table 9.

The Deterministic Variables.

| Variable |

Description |

Time Frame |

Cost |

Source |

|

GCS,LP

|

Ground control station, and landing pad |

Once |

$5,000 |

[43] |

| TBILT |

Inspection team leader |

Hour |

$150 |

[18] |

| TABI |

Assistant inspector |

Hour |

$120 |

| PPE |

Post-processing engineers |

Hour |

$120 |

| TP |

Cost of training pilot |

Once |

$2,575 |

[44] |

| CStorage |

Storage cost |

Month |

$180 once + $100 per month |

Market |

| CRegistration |

Registration cost |

3 Years |

$5 |

[44] |

| TTC |

Travel time cost |

Hour |

$6,915 at peak hrs.$1,235 during off-peak hrs. |

[17] |

| VOC |

Vehicle operation costs |

Hour |

$345 during peak times$115 during off-peak times |

[16] |

| FC+IC |

|

Year |

$2,250 + $369 Per worker |

[45] |

| ISE |

Safety equipment savings |

Inspection/Person |

$275 |

[46] |

Table 10.

NPV and BCR of the first D-BCM (snapshot: September 2023).

Table 10.

NPV and BCR of the first D-BCM (snapshot: September 2023).

| Investment Cost Area |

Cost ($) |

Costs Area |

Time |

Cost ($) |

Benefits Area |

Time |

Cost ($) |

| Drone |

5,000 |

SBP |

2 hours |

22.62 |

TBI |

8 hours |

960 |

| Payload |

1,850.99 |

CostSoft

|

1 month |

260 |

TABI |

8 hours |

1,200 |

| Training Pilot |

2,575 |

LI |

1 month |

126.16 |

UBIV |

1 hour |

1,056.82 |

| GCS |

5,000 |

BILT |

2 hours |

300 |

LCC |

1 hour |

1,850 |

| Memory Card |

180 |

ABI |

2 hours |

240 |

RiskFI

|

1 day |

431.5 |

| Registration cost |

5 |

PPE |

4 hours |

480 |

ISE |

1 inspection |

275 |

| |

|

CostStorage

|

1 month |

100 |

TTC |

1 hours |

1,235 |

| |

|

|

|

|

VOC |

1 hours |

115 |

| Total |

14,605.99 |

|

|

1,528.78 |

|

|

7,123.32 |

| NPV |

-9,011.45 |

| BCR |

0.441488785 |

Table 11.

The payback inspection and return rate.

Table 11.

The payback inspection and return rate.

| Payback Inspection |

Cumulative NPV |

Return Rate |

| 1 |

-9,011.45 |

-61.72% |

| 2 |

-3,416.91 |

-23.40% |

| 3 |

2,177.63 |

14.92% |

| 4 |

7,772.17 |

53.23% |

| 5 |

13,366.71 |

91.54% |

| 6 |

19,961.25 |

136.64% |

| 7 |

26,555.79 |

181.75% |

| 8 |

33,150.33 |

226.86% |

| 9 |

39,744.87 |

271.97% |

| 10 |

44,755.41 |

306.51% |

Table 12.

NPV and BCR analysis for a 10-Year time horizon at a 7% discount rate.

Table 12.

NPV and BCR analysis for a 10-Year time horizon at a 7% discount rate.

| Year |

Project Year |

Discounted Investment Cost at 7% |

Discounted Monthly Costs at 7% |

Discounted Maintenance Costs at 7% |

Discounted Costs per Inspection at 7% |

Discounted Benefits per Inspection at 7% |

Discounted NPV at 7% |

BCR |

| 2023 |

0 |

14,605.99 |

5,833.92 |

570.00 |

1,0426.20 |

71,233.20 |

39,797.09 |

2.26 |

| 2024 |

1 |

0 |

5,452.26 |

532.71 |

9,744.11 |

66,573.08 |

50,844.00 |

4.23 |

| 2025 |

2 |

0 |

5,095.57 |

497.86 |

9,106.64 |

62,217.83 |

47,517.76 |

4.23 |

| 2026 |

3 |

0 |

4,762.21 |

465.28 |

8,510.88 |

58,147.50 |

44,409.12 |

4.23 |

| 2027 |

4 |

0 |

4,450.66 |

434.85 |

7,954.09 |

54,343.46 |

41,503.85 |

4.23 |

| 2028 |

5 |

10,413.86 |

4,159.50 |

406.40 |

7,433.73 |

50,788.28 |

28,374.78 |

2.26 |

| 2029 |

6 |

0 |

3,887.38 |

379.81 |

6,947.41 |

47,465.68 |

36,251.07 |

4.23 |

| 2030 |

7 |

0 |

3,633.07 |

354.96 |

6,492.91 |

44,360.45 |

33,879.50 |

4.23 |

| 2031 |

8 |

0 |

3,395.39 |

331.74 |

6,068.14 |

41,458.37 |

31,663.09 |

4.23 |

| 2032 |

9 |

0 |

3,173.26 |

310.04 |

5,671.16 |

38,746.14 |

29,591.67 |

4.23 |

Table 13.

NPV and BCR analysis for a 10-year time horizon at a 3% discount rate.

Table 13.

NPV and BCR analysis for a 10-year time horizon at a 3% discount rate.

| Year |

Project Year |

Discounted Investment Cost at 3% |

Discounted Monthly Costs at 3% |

Discounted Maintenance Costs at 3% |

Discounted Costs per Inspection at 3% |

Discounted Benefits per Inspection at 3% |

Discounted NPV at 3% |

BCR |

| 2023 |

0 |

14,605.99 |

5,833.92 |

570.00 |

10,426.20 |

71,233.20 |

39,797.09 |

2.26 |

| 2024 |

1 |

0 |

5,664.00 |

553.39 |

10,122.52 |

69,158.44 |

52,818.52 |

4.23 |

| 2025 |

2 |

0 |

5,499.02 |

537.27 |

9,827.69 |

67,144.12 |

51,280.12 |

4.23 |

| 2026 |

3 |

0 |

5,338.86 |

521.63 |

9,541.44 |

65,188.46 |

49,786.52 |

4.23 |

| 2027 |

4 |

0 |

5,183.36 |

506.43 |

9,263.54 |

63,289.77 |

48,336.43 |

4.23 |

| 2028 |

5 |

12,599.25 |

5,032.39 |

491.68 |

8,993.73 |

61,446.38 |

34,329.32 |

2.26 |

| 2029 |

6 |

0 |

4,885.81 |

477.36 |

8,731.77 |

59,656.68 |

45,561.72 |

4.23 |

| 2030 |

7 |

0 |

4,743.51 |

463.46 |

8,477.45 |

57,919.11 |

44,234.68 |

4.23 |

| 2031 |

8 |

0 |

4,605.35 |

449.96 |

8,230.53 |

56,232.14 |

42,946.29 |

4.23 |

| 2032 |

9 |

0 |

4,471.21 |

436.85 |

7,990.81 |

54,594.31 |

41,695.43 |

4.23 |

Table 14.

Statistics of sensitivity analysis ($).

Table 14.

Statistics of sensitivity analysis ($).

| |

DP |

NPV |

BCR |

Investment Costs |

Monthly Costs |

Maintenance Costs |

| Short Term |

10,363.19 |

-15,245.725 |

0.318445 |

20,784.19 |

505.31 |

380 |

| Mid-Term |

12,365.81 |

-19,180.20417 |

0.270812 |

24,751.81 |

466.51 |

851 |

| Long Term |

5,911 |

-10,765.20083 |

0.398206 |

16,382 |

468.57 |

199.5 |

Table 15.

NPV Analysis of DP scenario at a 7% and 3% discount rate ($).

Table 15.

NPV Analysis of DP scenario at a 7% and 3% discount rate ($).

| Calendar Year |

NPV Discounted at 7% |

NPV Discounted at 3% |

| 2023 |

33,209.83 |

33,209.83 |

| 2024 |

50,461.70 |

52,421.37 |

| 2025 |

47,160.46 |

50,894.54 |

| 2026 |

44,075.20 |

49,412.17 |

| 2027 |

41,191.77 |

47,972.98 |

| 2028 |

29,636.14 |

35,855.38 |

| 2029 |

35,937.18 |

45,167.22 |

| 2030 |

33,586.15 |

43,851.67 |

| 2031 |

31,388.93 |

42,574.44 |

| 2032 |

29,335.45 |

41,334.41 |

| 2033 |

25,592.53 |

36,802.86 |

| 2034 |

25,920.51 |

39,414.47 |

| 2035 |

24,224.78 |

38,266.47 |

| 2036 |

22,639.98 |

37,151.92 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).