Submitted:

18 February 2025

Posted:

18 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Computational Details

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Identification and Construction of Research Subjects

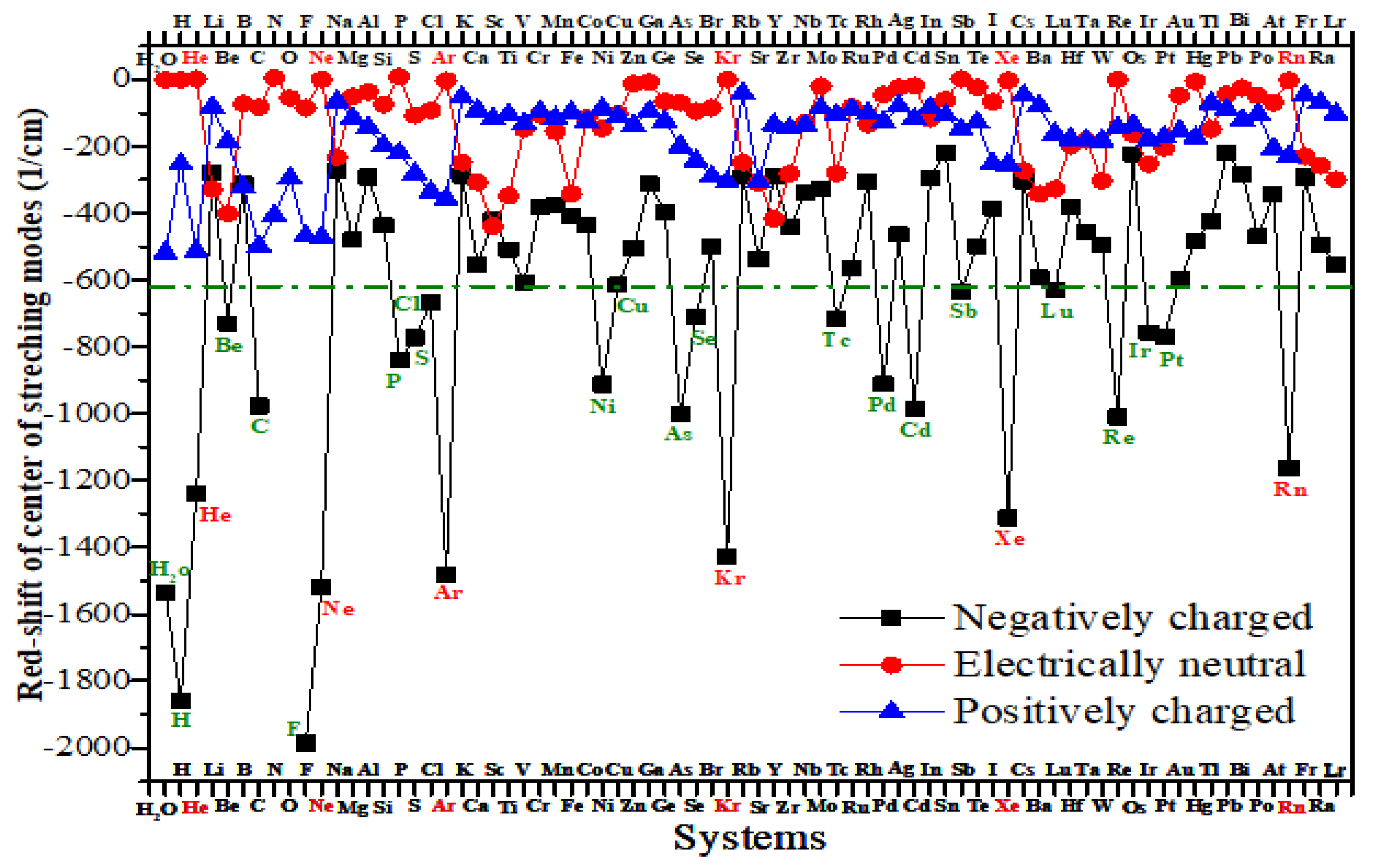

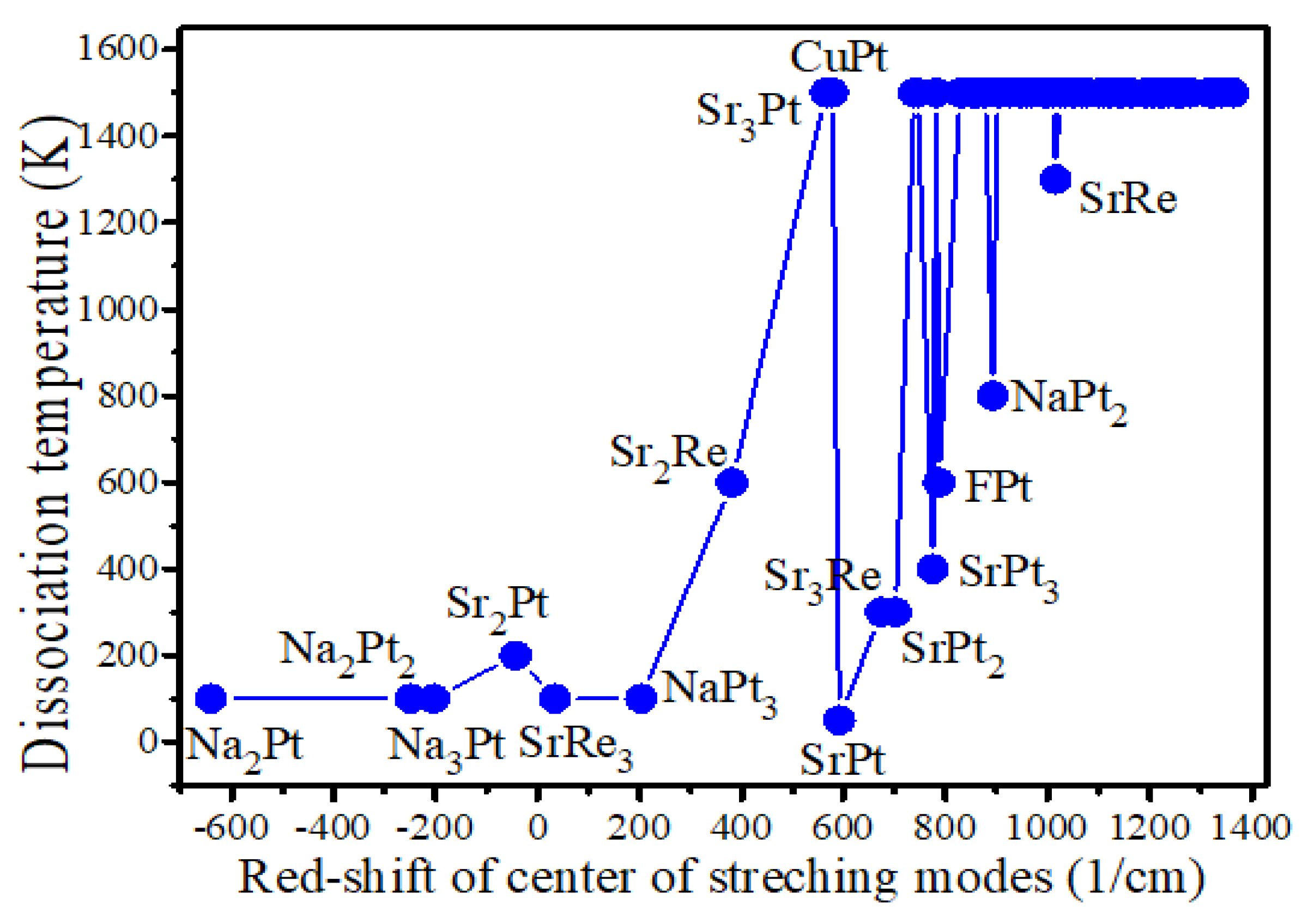

3.2. Dependence of Dissociation Temperature on Infrared Vibrational Spectra

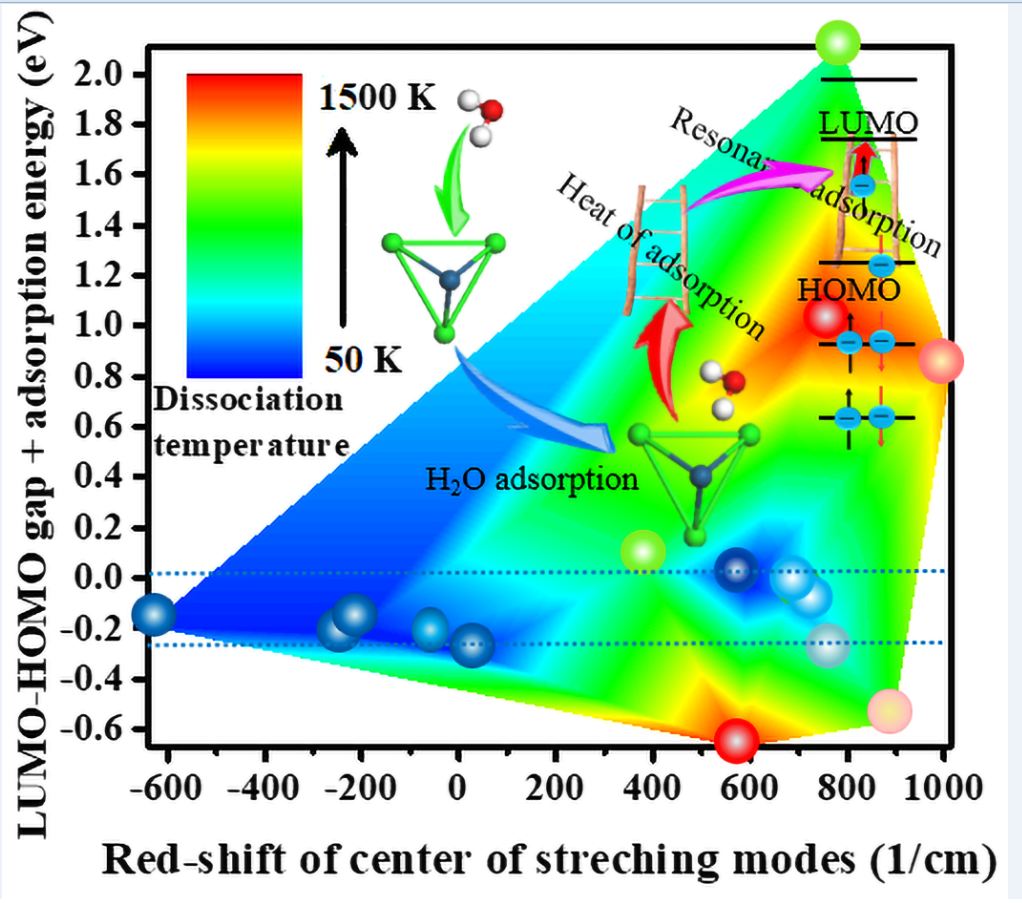

3.3. Resonant Absorption of Heat of Adsorption Versus Dissociation Temperature

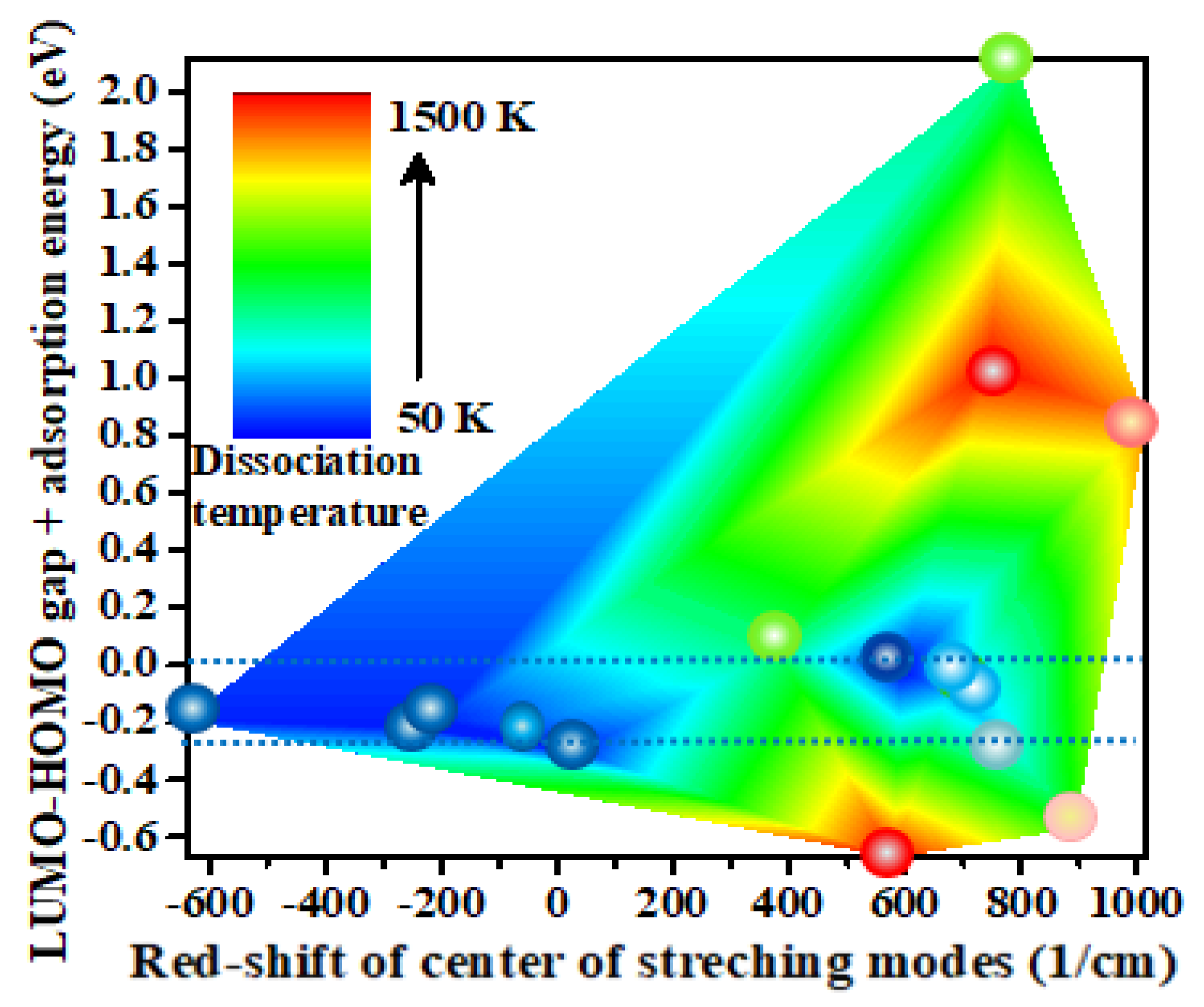

3.4. The Function of the Frontier Molecular Orbitals (FMOs)

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Y.; et al. Recent Advances on Water-Splitting Electrocatalysis Mediated by Noble-Metal-Based Nanostructured Materials. Adv. Energy Mater. 2020, 10, 1903120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; et al. Visualizing H2O Molecules Reacting at TiO2 Active Sites with Transmission Electron Microscopy. Science 2020, 367, 428–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishiyama, H.; et al. Photocatalytic Solar Hydrogen Production from Water on a 100-m2 Scale. Nature 2021, 598, 304–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranz, C.; Wächtler, M. Characterizing photocatalysts for water splitting: from atoms to bulk and from slow to ultrafast processes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 1407–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujishima, A.; Honda, K. Electrochemical Photolysis of Water at a Semiconductor Electrode. Nature 1972, 238, 37–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujitani, T.; Nakamura, I.; Takahashi, A. H2O Dissociation at the Perimeter Interface between Gold Nanoparticles and TiO2 Is Crucial for Oxidation of CO. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 2517–2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajin, J.L.C.; Cordeiro, M.N.D.S.; Illas, F.; Gomesc, J.R.B. Influence of step sites in the molecular mechanism of the water gas shift reaction catalyzed by copper. J. Catal. 2009, 268, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prats, H.; Gamallo, P.; Illas, F.; Sayós, R. Comparing the catalytic activity of the water gas shift reaction on Cu(321) and Cu(111) surfaces: Step sites do not always enhance the overall reactivity. J. Catal. 2016, 342, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.C.; Lin, C.H.; Wang, J.H. Trends of Water Gas Shift Reaction on Close-Packed Transition Metal Surfaces. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 114, 9826–9834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, F.; Agusta, M.K.; Maezono, R.; Dipojono, H.K. DFT + U study of H2O adsorption and dissociation on stoichiometric and nonstoichiometric CuO(111) surfaces. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 2020, 32, 045001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, N.A.; Alias, M.S.; Kamarudin, S.K. The Mechanism of the Water Dissociation and Dehydrogenation of Glycerol on Au(111) and PdAu Alloy Catalyst Surfaces. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2021, 46, 30937–30947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; et al. Amorphization Activated Ruthenium-Tellurium Nanorods for Efficient Water Splitting. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajin, J.L.C.; Cordeiro, M.N.D.S.; Illas, F.; Gomesc, J.R.B. Descriptors controlling the catalytic activity of metallic surfaces toward water splitting. J. Catal. 2010, 276, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; et al. A Janus Nickel Cobalt Phosphide Catalyst for High-Efficiency Neutral-PH Water Splitting. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 47, 15671–15675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Feng, Z.; Zhang, S.; Liang, Y.; Wang, R. Engineering MoS2 Basal Planes for Hydrogen Evolution via Synergistic Ruthenium Doping and Nanocarbon Hybridization. Adv. Sci. 2019, 6, 1900090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; et al. d-Band Center Modulating of CoOx/Co9S8 by Oxygen Vacancies for Fast-Kinetics Pathway of Water Oxidation. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 427, 130915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, X.; et al. Quadruple Perovskite Ruthenate as a Highly Efficient Catalyst for Acidic Water Oxidation. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takata, T.; Domen, K. Defect Engineering of Photocatalysts by Doping of Aliovalent Metal Cations for Efficient Water Splitting. J. Phys. Chem. C 2009, 113, 19386–19388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takata, T.; Jiang, J.; Sakata, Y.; Nakabayashi, M.; Domen, K. Photocatalytic Water Splitting with a Quantum Efficiency of Almost Unity. Nature 2020, 581, 411–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, L.; et al. Enhancing Charge Separation on High Symmetry SrTiO3 Exposed with Anisotropic Facets for Photocatalytic Water Splitting. Energy Environ. Sci. 2016, 9, 2463–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; et al. Single-atom Cu anchored catalysts for photocatalytic renewable H2 production with a quantum efficiency of 56%. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haxton, D.J.; Rescigno, T.N.; McCurdy, C.W. Dissociative electron attachment to the H2O molecule. II. Nuclear dynamics on coupled electronic surfaces within the local complex potential model. Phys. Rev. A 2007, 75, 012711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adaniya, H.; et al. Imaging the molecular dynamics of dissociative electron attachment to water. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 103, 233201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Ren, X.; Xie, D.; Guo, H. Enhancing dissociative chemisorption of H2O on Cu(111) via vibrational excitation. PNAS 2012, 109, 10224–10227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, B.N.J.; Baratoff, A. Inelastic electron tunneling from a metal tip: the contribution from resonant processes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1987, 59, 339–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.C.; Chiang, K.Y.; Okuno, M.; et al. Vibrational couplings and energy transfer pathways of water’s bending mode. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling, T.; Dennison, D.M. The Water Vapor Molecule. Phys. Rev. 1940, 57, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polanyi, J.C. Concepts in reaction dynamics. Acc. Chem. Res. 1972, 5, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; An, F.; Chen, Z.; et al. Vibrationally excited molecular hydrogen production from the water photochemistry. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crim, F.F. State- and Bond-Selected Unimolecular Reactions. Science 1990, 249, 1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crim, F.F. Vibrational state control of bimolecular reactions: discovering and directing the chemistry. Acc. Chem. Res. 1999, 32, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Xie, D.; Guo, H. Vibrationally mediated bond selective dissociative chemisorption of HOD on Cu(111). Chem. Sci. 2013, 4, 503–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, A.; Seenivasan, H.; Tiwari, A.K. Water dissociation on Cu (111): Effects of molecular orientation, rotation, and vibration on reactivity. J. Chem. Phys. 2012, 137, 094708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, B.; Li, J.; Xie, D.; Guo, H. Effects of reactant internal excitation and orientation on dissociative chemisorption of H2O on Cu(111): Quasi-seven-dimensional quantum dynamics on a refined potential energy surface. J. Chem. Phys. 2013, 138, 044704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seenivasan, H.; Tiwari, A.K. Water dissociation on Ni(100) and Ni(111): Effect of surface temperature on reactivity. J. Chem. Phys. 2013, 139, 174707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, T.; Fu, B.; Yang, X.; Zhang, D.H. First-Principles Quantum Dynamical Theory for the Dissociative Chemisorption of H2O on Rigid Cu(111). Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seenivasan, H.; Jackson, B.; Tiwari, A.K. Water dissociation on Ni(100), Ni(110), and Ni(111) surfaces: Reaction path approach to mode selectivity. J. Chem. Phys. 2017, 146, 074705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Ray, D.; Tiwari, A.K. Effects of alloying on mode-selectivity in H2O dissociation on Cu/Ni bimetallic surfaces. J. Chem. Phys. 2019, 150, 114702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hundt, P.M.; Jiang, B.; van Reijzen, M.E.; Guo, H.; Beck, R.D. Vibrationally Promoted Dissociation of Water on Ni(111). Science 2014, 344, 504–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Guo, H. Control of mode/bond selectivity and product energy disposal by the transition state: X + H2O (X = H, F, O(3P), and Cl) reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 15251–15256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Guo, H. Relative efficacy of vibrational vs. translational excitation in promoting atom-diatom reactivity: Rigorous examination of Polanyi’s rules and proposition of sudden vector projection (SVP) model. J. Chem. Phys. 2013, 138, 234104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, H.J.; Jung, J.; Motobayashi, K.; et al. State-selective dissociation of a single water molecule on an ultrathin MgO film. Nature Mater. 2010, 9, 442–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavlo, M.; Maxim, G.; Thomas, R.R.; Oleg, V.B. State-resolved spectroscopy of high vibrational levels of water up to the dissociative continuum. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 2012, 370, 2710–2727. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wu, G. Shift of Infrared Vibrational Spectra and H2O Activation on PtCu Alloy Clusters. AIP Adv. 2020, 10, 085019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z. A DFT Study of Enhancement of H2O Activation in Vibrational Excitation. Inorganica Chim. Acta. 2020, 514, 119980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdew, J.P.; Burke, K.; Ernzerhof, M. Generalized Gradient Approximation Made Simple. Generalized Gradient Approximation Made Simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865–3868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delley, B. Hardness conserving semilocal pseudopotentials. Phys. Rev. B 2002, 66, 155125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Tang, Z.; Zang, W.; et al. Ferromagnetic single-atom spin catalyst for boosting water splitting. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2023, 18, 763–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mtangi, W.; Kiran, V.; Fontanesi, C.; Naaman, R. Role of the Electron Spin Polarization in Water Splitting. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2015, 6, 4916–4922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faradzhev, N.S.; Kostov, K.L.; Feulner, P.; Madey, T.E.; Menzel, D. Stability of water monolayers on Ru(0 0 0 1): Thermal and electronically induced dissociation. Chemical Physics Letters 2005, 415, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauhon, L.J.; Ho, W. Inducing and observing the abstraction of a single hydrogen atom in bimolecular reactions with a scanning tunneling microscope. J. Phys. Chem. B 2001, 105, 3987–3992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgenstern, K.; Rieder, K.H. Dissociation of water molecules with the scanning tunnelling microscope. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2002, 358, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugarza, A.; Shimizu, T.K.; Ogletree, D.F.; Salmeron, M. Chemical reaction of water molecules on Ru(0001) induced by selective excitation of vibrational modes. Surf. Sci. 2009, 603, 2030–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maksyutenko, P.; Rizzo, T.R.; Boyarkin, O.V. A direct measurement of the dissociation energy of water. J. Chem. Phys. 2006, 125, 181101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Su, N.Q.; Yang, W. Describing Chemical Reactivity with Frontier Molecular Orbitalets. JACS Au 2022, 2, 1383–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browna, J.J.; Cockroft, S.L. Aromatic reactivity revealed: beyond resonance theory and frontier orbitals. Chem. Sci. 2013, 4, 1772–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohara, M.; Kim, Y.; Yanagisawa, S.; Morikawa, Y.; Kawai, M. Role of Molecular Orbitals Near the Fermi Level in the Excitation of Vibrational Modes of a Single Molecule at a Scanning Tunneling Microscope Junction. PRL 2008, 100, 136104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Diatomic clusters 24 |

BePt | CPt | NPt | FPt | NaPt | PPt |

| NiPt | Cu2 | CuPt | AsPt | SrCd | SrRe | |

| SrPt | TcPt | PdPt | Cd2 | CdRe | CdPt | |

| SbPt | Re2 | RePt | IrPt | Pt2 | PtAu | |

| Triatomic clusters30 | Be2Pt | C2Pt | N2Pt | F2Pt | Na2Pt | NaPt2 |

| P2Pt | Ni2 | Ni2Pt | Cu3 | Cu2Pt | As2Pt | |

| Sr2Cd | Sr2Re | Sr2Pt | SrCd2 | SrRe2 | SrPt2 | |

| Tc2Pt | Pd2Pt | Cd3 | Cd2Re | Cd2Pt | CdRe2 | |

| Sb2Pt | Re3 | Re2Pt | Ir2Pt | Pt3 | PtAu2 | |

| Tetraatomic clusters 34 |

Be3Pt | C3Pt | N3Pt | F3Pt | Na4 | Na3Pt |

| Na2Pt2 | NaPt3 | P3Pt | Ni3Pt | NiPt3 | Cu4 | |

| Cu3Pt | As3Pt | Sr4 | Sr3Cd | Sr3Re | Sr3Pt | |

| Sr2Re2 | Sr2Pt2 | SrCd3 | SrRe3 | SrPt3 | Tc3Pt | |

| Pd3Pt | Cd4 | Cd3Re | Cd3Pt | CdRe3 | Sb3Pt | |

| Re4 | Re3Pt | Ir3Pt | Pt4 |

| Systems | ∆IR (1/cm) | Eg (eV) | Ea (eV) | Ea+Eg (eV) | Td (K) |

| Na2Pt | -640.5 | 0.71 | -0.90 | -0.19 | 100 |

| Na2Pt2 | -249.5 | 0.75 | -0.97 | -0.22 | 100 |

| Na3Pt | -203.1 | 0.67 | -0.86 | -0.19 | 100 |

| Sr2Pt | -42.8 | 0.60 | -0.80 | -0.20 | 200 |

| SrRe3 | 34.1 | 0.28 | -0.58 | -0.30 | 100 |

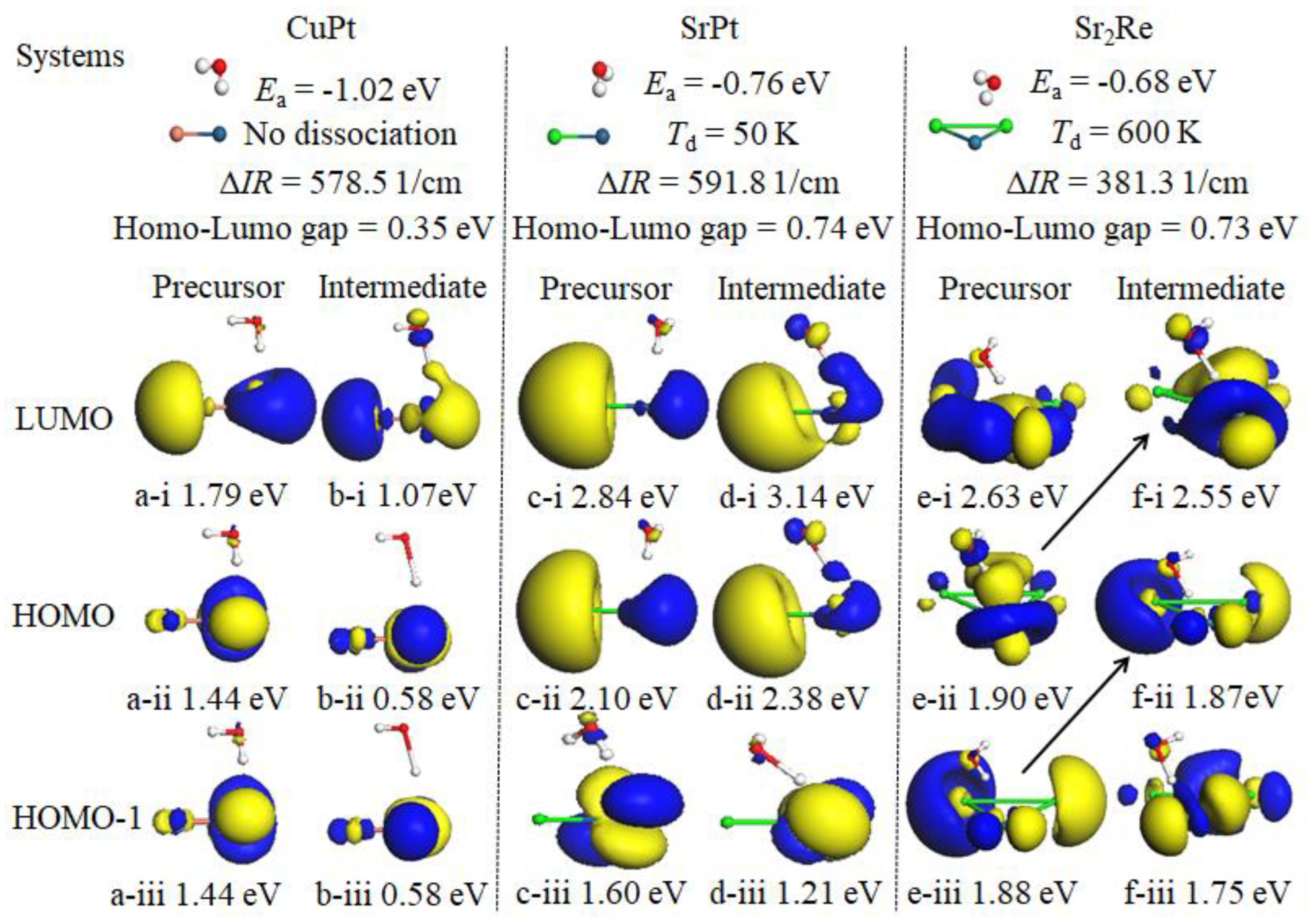

| Sr2Re | 381.3 | 0.73 | -0.68 | 0.05 | 600 |

| CuPt | 578.5 | 0.35 | -1.02 | -0.67 | 1500 |

| SrPt | 591.8 | 0.74 | -0.76 | -0.02 | 50 |

| Sr3Re | 673.8 | 0.59 | -0.68 | -0.09 | 300 |

| SrPt2 | 702.0 | 0.96 | -1.09 | -0.13 | 300 |

| Sr2Pt2 | 745.3 | 0.45 | 0.59 | 1.04 | 1500 |

| SrPt3 | 774.9 | 0.73 | -0.98 | -0.25 | 400 |

| FPt | 787.4 | 2.95 | -0.84 | 2.11 | 600 |

| NaPt2 | 892.9 | 0.44 | -1.01 | -0.57 | 800 |

| SrRe | 1015.9 | 0.55 | 0.30 | 0.85 | 1300 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).