1. Introduction

African swine fever (ASF) is a highly contagious disease caused by African swine fever virus (ASFV), with the main susceptible animals being domestic pigs and wild boars [

1]. The symptoms of diseased pigs include elevated body temperature, respiratory disorders, neurological symptoms, and other clinical symptoms [

2]. The mortality rate of pigs infected with virulent strains is as high as 100% [

3]. ASFV was first reported in Kenya in 1921 and was introduced to Georgia in 2007 [

4,

5]. In August 2018, ASF first appeared in Shenyang, Liaoning Province, China, and quickly spread to various parts of the country [

6]. ASF has a history of over a hundred years; however, there is still a lack of effective commercial vaccines and antiviral drugs. Therefore, establishing efficient ASF detection is of great significance for the prevention and control of ASF.

ASFV is a double stranded DNA virus with a symmetrical icosahedral structure and a diameter of approximately 260-300 nm [

7]. The ASFV genome has a total length of 170 kb to 190 kb, encoding 150-200 viral proteins which can be divided into over 60 structural proteins and over 100 non-structural proteins [

8]. The p54 protein is an important structural protein encoded by the E183L gene with a relative molecular weight of 24-28 kD. It is located in the inner envelope of viral particles and appears in the late stage of viral infection as a late stage protein [

9]. The term "p54" is not related to its molecular weight (about 25 kD), but to its relative position in the two-dimensional gel [

10].

The viral p54 protein can rely on its transmembrane structure to transform the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane into viral inner membrane precursor, and thus play an important role in the process of viral particle assembly [

9]. There is a segment of dynein binding domain (DBD) between amino acids 149-161 in the C-terminus of p54 protein [

11]. After the virus enters the cell, p54 interacts with the intracellular dynein to promote the movement of virus particles in the cytoplasm [

11,

12]. In addition, the DBD is involved in activating caspase-3, leading to apoptosis [

13]. Studies showed that p54 was capable of inducing neutralization antibody in immunized pigs and plays an important role in inducing protective immune response [

14,

15,

16]. The ELISA antibody detection based on p54 protein has the same performance as the WOAH standard ELISA assay based on whole virus antigen [

17]. Due to its strong immunogenicity and antigenicity, p54 protein is often used as a target as p72 and p30, in the development of serological diagnosis technology [

18].

In this study, we expressed and purified p54 truncated protein, immunized mice and generated three monoclonal antibodies (mAbs). The novel antigenic epitopes recognized by the three mAbs were identified, namely 60AAIEEEDIQFINP72, 128MATGGPAAAPAAASAPAHPAE148 and 163MSAIENLRQRNTY175. In addition, an epitope based indirect ELISA was established, which can specifically detect ASFV positive serum.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mice, Cells, Sera, and Viruses

BALB/c mice of 6 to 8 weeks were purchased from the experimental animal facility of Yangzhou University. HEK-293T cells, Marc-145 cells and myeloma SP2/0 cells were cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM, Hyclone Laboratories, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Eallbio, Beijing, China). Primary porcine alveolar macrophages (PAMs) were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Hyclone Laboratories) containing 2% FBS. The ASFV strain (genotype II, GenBank accession No. 456300) was kept in the facility of Yangzhou University Animal Biosafety Level 3 (ABSL-3) certified by the Ministry of agriculture and rural affairs (0714002001109-1). The porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV), recombinant PRRSV expressing p54 (PRRSV-p54), porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV), swine influenza virus (SIV) and porcine serum samples were stored in our lab. Animal experiments were conducted in strict accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of Yangzhou University (SYXK(JS) -2021-0026).

2.2. Expression and Purification of p54 Truncation Protein

The truncated ASFV p54 gene (p54 JD, 55-184 aa) was obtained by PCR amplification using the primers shown in

Table S1, from the pENTR4-ASFV p54-2HA plasmid stored in our laboratory. The PCR product was cloned into the

SalI and

XhoI sites of pET28a-6His vector through Seemless/In- Fusion cloning and sequenced confirmed by DNA sequencing. The recombinant pET28a-p54 JD-6His was transformed into BL21 competent

E.coli cells to explore the induction conditions by 1mM IPTG, including time and temperature. Under optimal induction, the bacteria were collected by centrifugation, resuspended in PBS and sonicated on ice. After centrifugation, the bacterial pellet was resuspended in PBS solution containing 8 M urea, shaken overnight at 4 °C, and then subjected to gradient dialysis and subsequent refolding.

2.3. Generation of Anti-p54 Monoclonal Antibodies (mAbs)

Mice were immunized with purified p54 protein plus adjuvant Montanide gel (SEPPIC SA, Cedex, France), following the same procedure as we described before [

19,

20]. Five days post the three immunizations, blood samples were collected from the tail vein of mice and the serum titer was determined by ELISA and confirmed by Western blotting. The mice with the highest titer of serum ELISA antibody were used for final booster, and splenocytes from the mice were harvested and fused with SP2/0 cells following standard procedure. Hybridomas secreting p54 specific antibody were screened out by p54 coated indirect ELISA and confirmed by Western blotting. Positive hybridomas were subcloned three times by limiting dilution and confirmed by antibody production. Mouse ascites was prepared using sterile liquid paraffin and subcloned hybridoma following the standard procedure.

2.4. Mapping of the Antigenic Epitopes of p54 Protein

According to the epitope prediction results, the full-length p54 protein was first truncated into three fragments (1-54aa, 55-122aa, 123-184aa), cloned into the eukaryotic expression vector pEGFP-N1, respectively, and transfected into 293T cells. The truncated protein fragments recognized by p54 mAbs were identified by Western blotting. According to the results, the p54 protein fragments were further truncated and examined for recognition by p54 mAbs. Next, the p54 protein fragments were progressively shortened from both ends to clarify the minimal antigenic epitopes targeted by p54 mAbs by Western blotting. A total of 28 p54 fragments (P1-P28) were designed and cloned into pEGFP-N1, with all the cloning primers listed in

Table S1.

2.5. Western Blotting (WB) and Immunofluorescence Assay (IFA)

The protein samples were mixed with 4×loading buffer with the ratio of 3:1, heated at 100℃ for 5–10 min and run by 8–10% SDS-PAGE. The gel was stained with Coomassie blue staining or detected by immunoblotting as we described previously [

19,

21], with p54 mAbs as the primary antibodies and HRP conjugated Goat anti mouse IgG (1:10000, BBI, Shanghai, China) as secondary antibody.

The 293T cells in 12 well cell culture plates (2×105 cells/well) were transfected with pCAGGS-p54-2HA and control pCAGGS-2HA for 24 h. Marc-145 cells in 12 well cell culture plates (2×105 cells/well) were mock infected or with recombinant PRRSV-p54 virus (MOI=1) for 72 h. The cells were fixed, permeabilized and stained with ascites p54 mAbs and Goat anti-mouse IgG H & L Alexa fluor 594 (1:500, Abcam, Shanghai, China). After DAPI staining (1:500, Abcam, Shanghai, China), the stained samples were visualized by a fluorescence microscope.

2.6. ASFV p54 Protein Indirect ELISA and Antigenic Peptide Indirect ELISA

For p54 protein indirect ELISA, the purified p54 JD fusion protein was diluted in PBS (0.625 μg/mL) as the coating antigen. For epitope mediated indirect ELISA, the synthesized epitope peptide was diluted in PBS (0.3125-10 μg/mL) as the coating antigen. Both indirect ELISAs followed the same procedures as we described previously [

19,

21]. After termination by 2 M H

2SO

4, the OD

450 nm value of each well was determined. The ratios of hybridoma supernatant versus negative supernatant and positive sera versus negative serum (P/N) were calculated, with P/N ≥ 2.1 as positive.

2.7. Bioinformatics Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Production and Identification of Recombinant p54 Truncation Protein

ASFV p54 protein is a transmembrane protein [

8,

9]. As expected, bioinformatics analysis showed that ASFV p54 protein possesses a highly hydrophobic transmembrane domain (TM) of 23 amino acids (30-52aa) near the N-terminal end (Fig 1A and B). Because the protein with transmembrane domain is difficult for expression and the C-terminal intramembrane region contains more antigenicity (Fig 1C), the C-terminal intramembrane domain (p54 JD, 55-184aa) was chosen for expression. The p54 JD encoding sequence was cloned into pET28a vector, and the recombinant protein was expressed in

E.coli BL21 cells. SDS-PAGE results showed that p54 JD protein was obviously induced by 1 mM IPTG at 25 °C or 37 °C for 24 h, appearing as 20 kD bands (Fig 1D). At 25 °C, under induction of 1 mM IPTG for 24 h, p54 JD protein was expressed in both soluble form and in inclusion body and the bands were relatively single at 25 °C (Fig 1E). The purified p54 JD from inclusion body had high purity and molecular weight about 20 kD (Fig 1F). After three immunizations, the serum antibody titer in mice reached higher than 1:409600, indicating that the p54 recombinant protein has good immunogenicity (Fig 1G).

Figure 1.

Production and identification of the p54 truncated fusion proteins. (A-C) Prediction of the transmembrane (A), hydrophilicity (B), and antigenic regions (C) of p54 protein using online tools described in Methods. In panel C, the yellow and green represent the regions of high and low antigenicity, respectively. (D) The p54 JD were induced with or without 1 mM IPTG at 16 ℃, 25 ℃ and 37 ℃. (E) The p54 JD was induced by 1 mM IPTG for 6 h, 12 h, 16 h and 24 h at 25 ℃, with the empty pET28a vector transformed bacteria as a control. Whole bacterial lysate, supernatant, and precipitate were examined for p54 JD protein expressions by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining. (F) The purified p54 JD protein was confirmed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie brilliant blue staining. The p54 JD of 20 kD was indicated by arrow heads. (G) Serum antibody titration of immunized mice were measured in an indirect ELISA coated with different concentrations of p54 JD protein.

Figure 1.

Production and identification of the p54 truncated fusion proteins. (A-C) Prediction of the transmembrane (A), hydrophilicity (B), and antigenic regions (C) of p54 protein using online tools described in Methods. In panel C, the yellow and green represent the regions of high and low antigenicity, respectively. (D) The p54 JD were induced with or without 1 mM IPTG at 16 ℃, 25 ℃ and 37 ℃. (E) The p54 JD was induced by 1 mM IPTG for 6 h, 12 h, 16 h and 24 h at 25 ℃, with the empty pET28a vector transformed bacteria as a control. Whole bacterial lysate, supernatant, and precipitate were examined for p54 JD protein expressions by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining. (F) The purified p54 JD protein was confirmed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie brilliant blue staining. The p54 JD of 20 kD was indicated by arrow heads. (G) Serum antibody titration of immunized mice were measured in an indirect ELISA coated with different concentrations of p54 JD protein.

3.2. Generation of Monoclonal Antibodies (mAbs) Specific for p54 Protein

Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) were obtained by standard cell fusion protocol. After 6-8 days of fusion, the cell supernatant of hybridomas were collected and used for screening of p54 mAbs by indirect ELISA. Through screening and subsequent three subcloning, three p54 mAb clones, named 6B11, 3E3 and 3C10, were obtained (Fig 2A). Indirect ELISA was utilized to measure the affinity of three mAbs to purified p54 protein. As shown in Fig 2B, the highest affinity of clone 6B11 was 1:409600, and those of clones 3E3 and 3C10 were 1:204800. The antibody subclass identification showed that the mAb 6B11 was IgG1, and the mAbs 3E3 and 3C10 were both IgG2b (Fig 2C and 2D).

Figure 2.

Preparation and characterization of anti-p54 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs). (A) The reactivity of mAbs was tested in p54 JD protein coated indirect ELISA. The cell supernatants of hybridoma clones were used as the primary antibodies, the SP2/0 cell supernatant was used as the negative control, and the serum of immunized mice was used as positive control. (B) Measurement of antibody titers of the ascites 6B11、3E3 and 3C10 mAbs by the p54 JD ELISA. (C-D) Identification of the mAb subtypes by the monoclonal antibody subclass identification kit (C060101) purchased from CELLWAY-LAB (Louyang China), following the product’s manual.

Figure 2.

Preparation and characterization of anti-p54 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs). (A) The reactivity of mAbs was tested in p54 JD protein coated indirect ELISA. The cell supernatants of hybridoma clones were used as the primary antibodies, the SP2/0 cell supernatant was used as the negative control, and the serum of immunized mice was used as positive control. (B) Measurement of antibody titers of the ascites 6B11、3E3 and 3C10 mAbs by the p54 JD ELISA. (C-D) Identification of the mAb subtypes by the monoclonal antibody subclass identification kit (C060101) purchased from CELLWAY-LAB (Louyang China), following the product’s manual.

The prepared ascites p54 mAbs were used as the primary antibodies to detect the specific reactions with different types of p54 proteins in Western blotting. The p54 proteins included those in 293T cells transfected with pCAGGS-p54-2HA, in primary PAMs infected with ASFV, and in Marc-145 infected with recombinant PRRSV-p54. The results showed that three mAbs 6B11, 3E3 and 3C10, all reacted specifically with different types of p54 proteins (Fig 3A). Further, three p54 mAbs were tested in Western blotting for the reactivity with different porcine viruses, including porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV), porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) and swine influenza virus (SIV). The results showed that the three p54 mAbs only specifically recognized ASFV, but not PRRSV, PEDV and SIV (Fig 3B). Additionally, immunofluorescence assay showed that three p54 mAbs had specific reactions with eukaryotic p54 in plasmid transfected cells (Fig 4A) and in PRRSV-p54 infected cells (Fig 4B), with the expressed p54 mainly localized in cytoplasm.

Figure 3.

Specific reactivity p54 mAbs determined using Western blotting. (A) 293T cells were transfected with pCAGGS-p54-2HA and pCAGGS-2HA vector control, respectively, for 24 h. (B) Primary PAMs were mock infected or infected with ASFV (MOI 0.1) for 96 h. (C) Marc-145 were mock infected or infected with PRRSV-p54 (MOI 0.1) for 96 h. The cells were collected and cell lysates were detected for p54 expressions by Western blotting with the mAbs 6B11, 3E3 and 3C10 as primary antibodies. (D) Western blotting of PRRSV, PEDV and SIV positive samples with three p54 mAbs, with ASFV positive sample as the positive control.

Figure 3.

Specific reactivity p54 mAbs determined using Western blotting. (A) 293T cells were transfected with pCAGGS-p54-2HA and pCAGGS-2HA vector control, respectively, for 24 h. (B) Primary PAMs were mock infected or infected with ASFV (MOI 0.1) for 96 h. (C) Marc-145 were mock infected or infected with PRRSV-p54 (MOI 0.1) for 96 h. The cells were collected and cell lysates were detected for p54 expressions by Western blotting with the mAbs 6B11, 3E3 and 3C10 as primary antibodies. (D) Western blotting of PRRSV, PEDV and SIV positive samples with three p54 mAbs, with ASFV positive sample as the positive control.

Figure 4.

The specific reactivity of p54 mAbs analyzed with Immunofluorescence assay. (A) 293T cells were transfected with pCAGGS-p54-2HA and pCAGGS-2HA vector, respectively for 24 h. (B) Marc-145 were infected with PRRSV-p54 (MOI 0.1) or mock infected as controls for 72 h. Cells were fixed and stained with 6B11, 3E3 or 3C10 mAb, together with Goat anti-mouse IgG H&L Alexa Fluor 594. Cellular nuclei were counterstained with 4’, 6’-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). The small boxed areas are magnified at the upper-right corners. Scale bars, 200 μm.

Figure 4.

The specific reactivity of p54 mAbs analyzed with Immunofluorescence assay. (A) 293T cells were transfected with pCAGGS-p54-2HA and pCAGGS-2HA vector, respectively for 24 h. (B) Marc-145 were infected with PRRSV-p54 (MOI 0.1) or mock infected as controls for 72 h. Cells were fixed and stained with 6B11, 3E3 or 3C10 mAb, together with Goat anti-mouse IgG H&L Alexa Fluor 594. Cellular nuclei were counterstained with 4’, 6’-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). The small boxed areas are magnified at the upper-right corners. Scale bars, 200 μm.

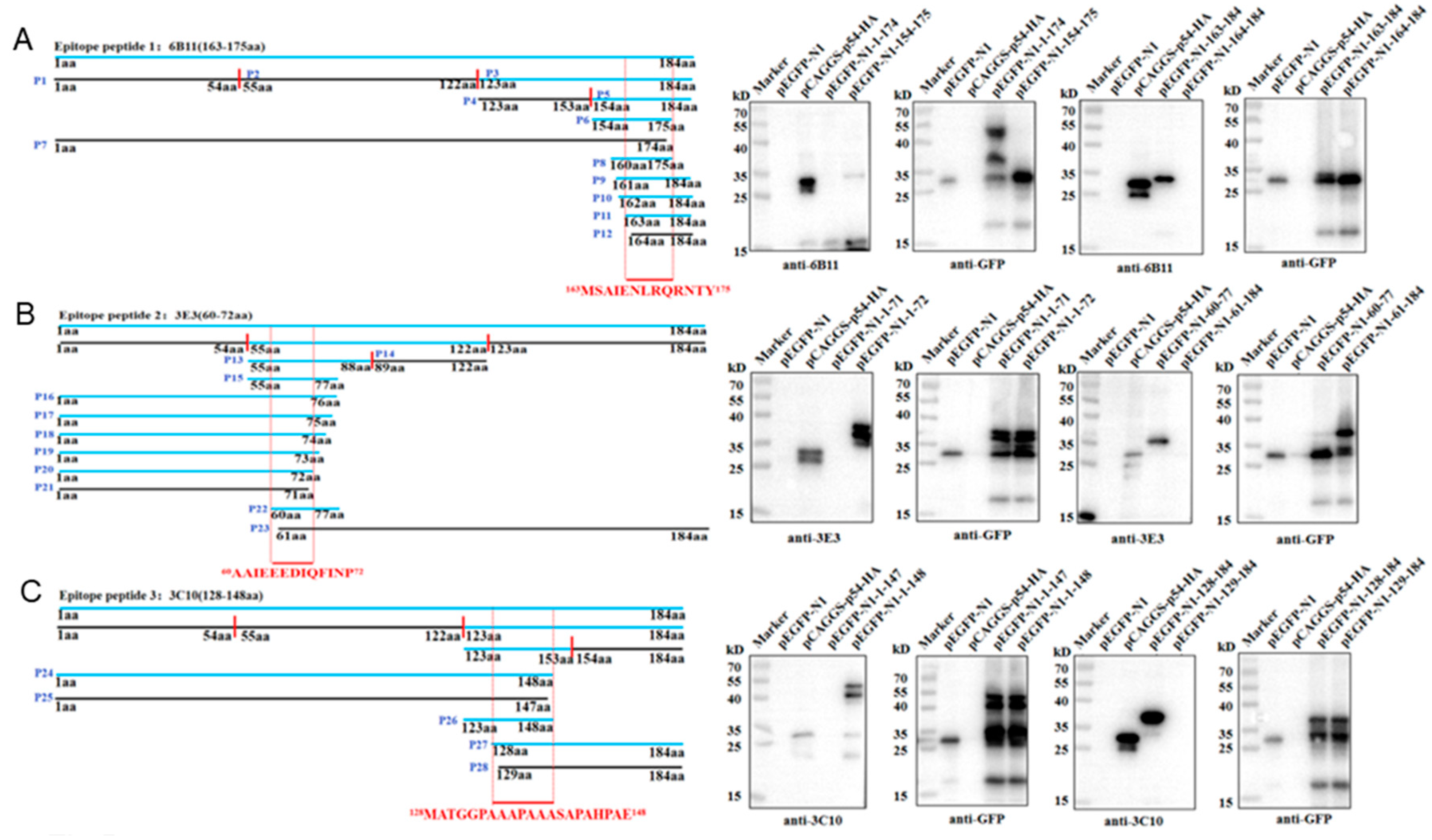

3.3. Identification of the Precise Antigenic Epitopes Targeted by p54 mAbs

The antigenic epitopes recognized by three p54 mAbs were determined by Western blotting. According to the prediction results of antigenic epitopes in Fig 1C, the full-length p54 protein was separated into three fragments (P1, 1-54aa; P2, 55-122aa; P3, 123-184aa), and the recombinant plasmids were constructed and transfected in 293T cells for truncation protein expressions. The results showed that 6B11 (Fig 5A) and 3C10 (Fig 5C) recognize the P3 region, and 3E3 (Fig 5B) recognizes the P2 region. The P2 and P3 were further separated into two fragments (P13, P14 and P4, P5), and it turned out that the 6B11, 3E3 and 3C10 recognize the P5, P13 and P4, respectively. Based on information of the reactive fragments, p54 protein was gradually shortened from both ends until it could not react with the p54 mAbs, so as to determine the minimum epitopes recognized by p54 mAbs, After rounds of shortening and testing, the final results showed that 6B11 recognizes the epitope 163MSAIENLRQRNTY175 (Fig 5A), 3E3 recognizes the epitope 60AAIEEEDIQFINP72 (Fig 5B), and 3C10 recognizes the epitope 128MATGGPAAAPAAASAPAHPAE148 (Fig 5C).

Figure 5.

Identification of the antigenic epitopes recognized by p54 mAbs. (A) Schematic diagram of p54 and its truncated fragments. Blue colored p54 and fragments denote reactive with mAbs, whereas black colored p54 fragments denote non-reactive with mAbs. The minimal epitopes recognized by mAbs are red colored and position labeled. The aa is an abbreviation for amino acid. (B) Western blotting analysis of the critical C-terminal amino acid (left) and N-terminal amino acid (right) for reactivity of p54 with mAbs 6B11, 3E3 and 3C10, respectively.

Figure 5.

Identification of the antigenic epitopes recognized by p54 mAbs. (A) Schematic diagram of p54 and its truncated fragments. Blue colored p54 and fragments denote reactive with mAbs, whereas black colored p54 fragments denote non-reactive with mAbs. The minimal epitopes recognized by mAbs are red colored and position labeled. The aa is an abbreviation for amino acid. (B) Western blotting analysis of the critical C-terminal amino acid (left) and N-terminal amino acid (right) for reactivity of p54 with mAbs 6B11, 3E3 and 3C10, respectively.

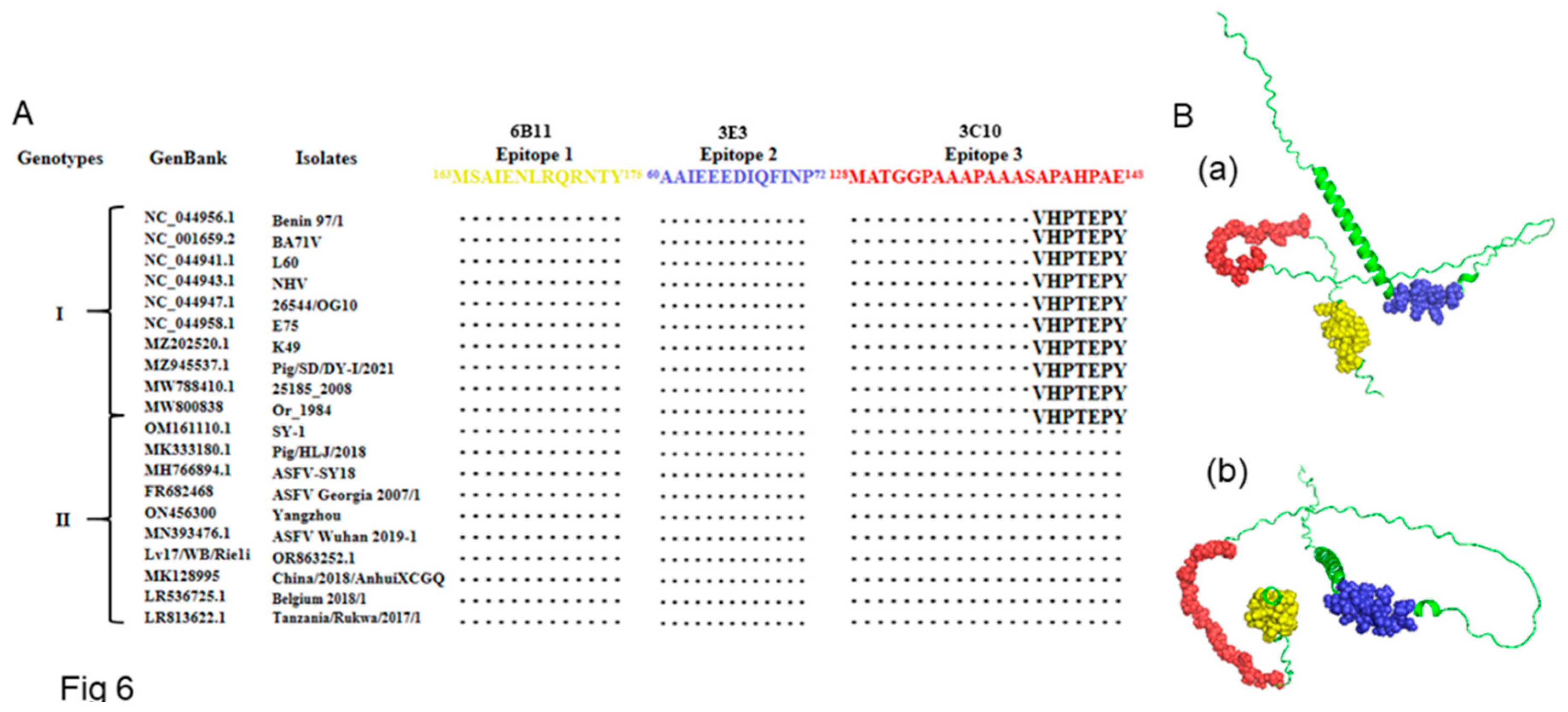

To determine the conservation of the three identified p54 antigenic epitopes, 170 ASFV E183L gene sequences were downloaded from GenBank, and the encoded protein sequences were aligned with the three antigenic epitope sequences. The results showed that the two antigenic epitopes of mAbs 6B11 and 3E3 were highly conserved across genotype I and genotype II ASFV strains, and the one of 3C10 was highly conserved in genotype II ASFV strains (Fig 6A and

Table S2). The p54 protein structure predicted by Alphafold2 is composed of a α helix and random coils. Among the three epitopes, one is located in the α helix, and two are inside the random coils (Fig 6B).

Figure 6.

Sequence conservation analysis of the identified epitopes across different genotypes ASFV strains. (A) Alignment of p54 protein sequences of representative genotypes I and II ASFV strains with the three antigenic epitopes identified (epitope 1, 163MSAIENLRQRNTY175, epitope 2, 60AAIEEEDIQFINP72 and epitope 3, 128MATGGPAAAPAAASAPAHPAE148). The GenBank accession number and isolate name of each ASFV strains are indicated. The dotted area indicate the identical conserved amino acid sequences; otherwise, the amino acids are marked. (B) Localization of the three mAb recognized epitopes in the structure of ASFV p54 protein. Antigenic epitopes 1 is in yellow, epitopes 2 is in blue, and epitopes 3 is in red, respectively, in the front view (a) and bottom view (b).

Figure 6.

Sequence conservation analysis of the identified epitopes across different genotypes ASFV strains. (A) Alignment of p54 protein sequences of representative genotypes I and II ASFV strains with the three antigenic epitopes identified (epitope 1, 163MSAIENLRQRNTY175, epitope 2, 60AAIEEEDIQFINP72 and epitope 3, 128MATGGPAAAPAAASAPAHPAE148). The GenBank accession number and isolate name of each ASFV strains are indicated. The dotted area indicate the identical conserved amino acid sequences; otherwise, the amino acids are marked. (B) Localization of the three mAb recognized epitopes in the structure of ASFV p54 protein. Antigenic epitopes 1 is in yellow, epitopes 2 is in blue, and epitopes 3 is in red, respectively, in the front view (a) and bottom view (b).

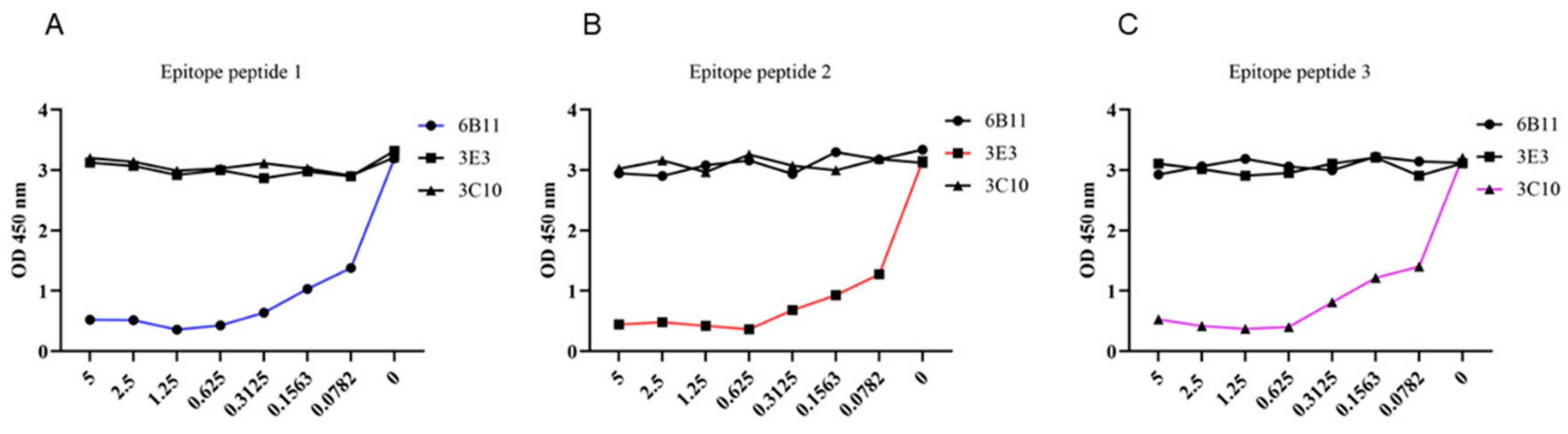

3.4. Validation of the p54 Epitopes by Competitive ELISA and Establishment of Epitope Indirect ELISA for Detection of ASF Antibody

To further determine whether the identified three epitopes are B cell epitopes recognized by monoclonal antibodies, we synthesized three epitope peptides and applied them in the p54 JD coated indirect ELISA for competitive binding. The competitive ELISA results demonstrated that the synthesized 6B11, 3E3 and 3C10 epitope peptides can inhibit the reaction of the corresponding mAbs with coated antigen of p54 JD protein, in dose-dependent manners, but not inhibit the reaction of the other two p54 mAbs with the p54 JD protein. These results further verified the correctness of epitope peptides recognized by p54 mAbs (Fig 7A-C).

Figure 7.

Competitive ELISA validation of epitope peptides recognized by p54 mAbs. In the p54 JD protein coated indirect ELISA, three synthesized short peptides were diluted at the indicated concentrations (μg/mL), and added with the primary antibodies of three ascites mAbs 6B11 (A), 3E3 (B) and 3C10 (C) for competitive binding with mAbs. The groups without short peptides were set as the negative controls. Finally, based on the OD450 results in ELISA, the graphs were drawn and correct epitopes were determined.

Figure 7.

Competitive ELISA validation of epitope peptides recognized by p54 mAbs. In the p54 JD protein coated indirect ELISA, three synthesized short peptides were diluted at the indicated concentrations (μg/mL), and added with the primary antibodies of three ascites mAbs 6B11 (A), 3E3 (B) and 3C10 (C) for competitive binding with mAbs. The groups without short peptides were set as the negative controls. Finally, based on the OD450 results in ELISA, the graphs were drawn and correct epitopes were determined.

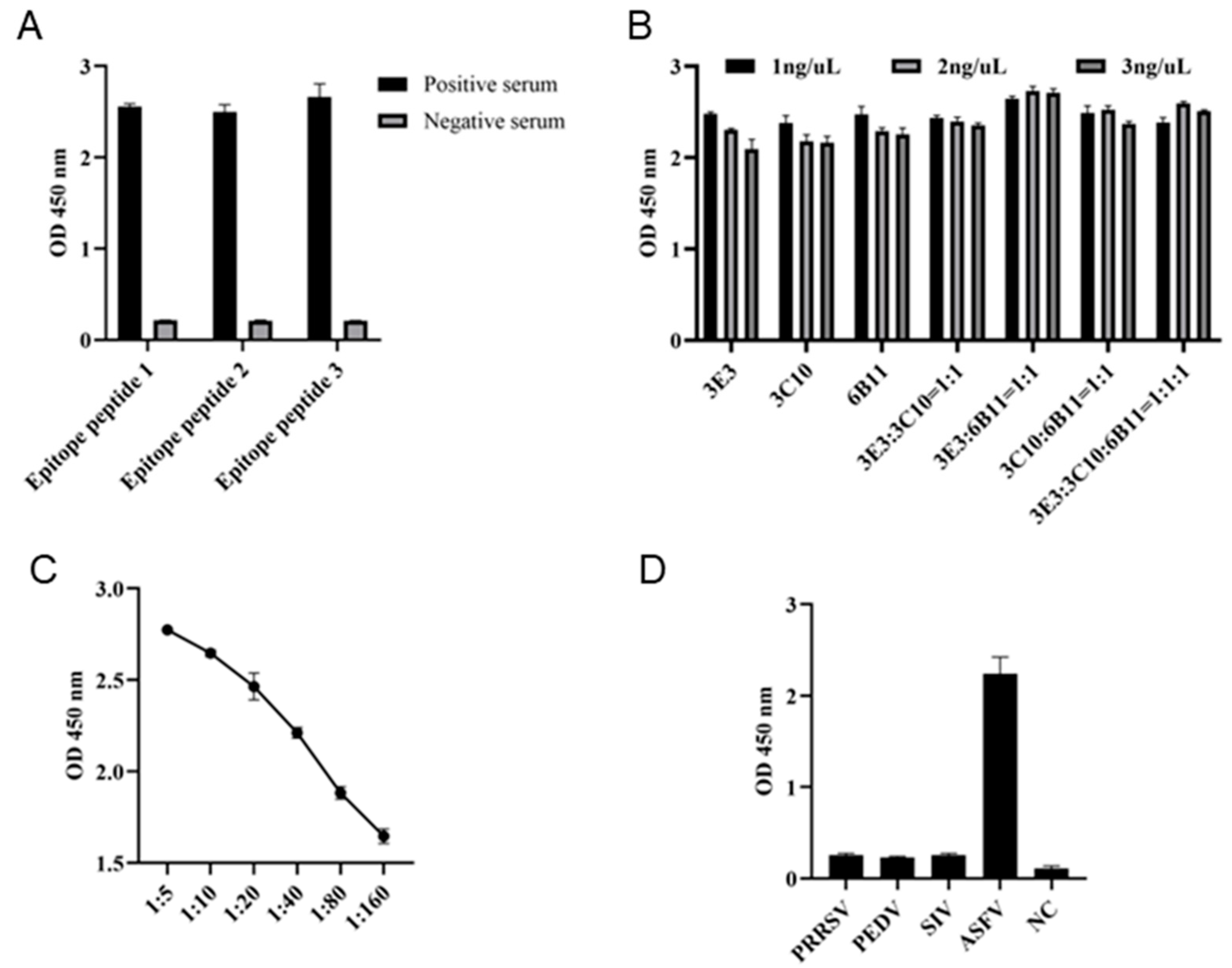

In order to determine whether the three epitopes can be used for diagnosis, the three epitope peptides were each used as the coated antigen with a concentration of 1 ng/μL, and the ASF positive and negative sera were diluted 1:10 for indirect ELISA detection of serum antibody. The results showed that all the three epitope peptides can be used for detection of antibody in ASF positive serum (Fig 8A). Subsequently, the combination of epitope peptides in indirect ELISA was explored by checkerboard method. The results showed that the highest OD450 values can be obtained with the coating peptide combination of 6B11:3E3 = 1:1 and a total concentration of 2 ng/μL (Fig 8B). With the optimal coating peptides, we continued to explore the optimal dilution of serum. The 1:5 dilution of ASF positive serum was shown to give the best performance (Fig 8C). The established epitope ELISA was used to detect antibody in ASFV, PRRSV, PEDV and SIV positive pig sera, and only ASFV positive serum but not others was successfully detected, indicating the high specificity (Fig 8D).

Figure 8.

Development of epitope indirect ELISA for detecting ASF specific antibody. (A) The p54 epitope peptides were used for coating at a concentration of 1 ng/μL. The epitope based ELISA were each tested for detection of ASFV positive and negative sera, with a serum dilution of 1:10. (B) The coating epitope combinations and concentrations in indirect ELISA for detection of ASFV positive serum (1:10 dilution). (C) The serum dilution in indirect ELISA with coating of peptide 1 and 2 combination and concentration at 2 ng/μL. (D) Specificity of the established epitope indirect ELISA. PRRSV, PEDV, SIV and ASFV positive pig sera and negative pig serum were used.

Figure 8.

Development of epitope indirect ELISA for detecting ASF specific antibody. (A) The p54 epitope peptides were used for coating at a concentration of 1 ng/μL. The epitope based ELISA were each tested for detection of ASFV positive and negative sera, with a serum dilution of 1:10. (B) The coating epitope combinations and concentrations in indirect ELISA for detection of ASFV positive serum (1:10 dilution). (C) The serum dilution in indirect ELISA with coating of peptide 1 and 2 combination and concentration at 2 ng/μL. (D) Specificity of the established epitope indirect ELISA. PRRSV, PEDV, SIV and ASFV positive pig sera and negative pig serum were used.

4. Discussion

Since the outbreak of ASF in Kenya in the 1920s, it has had a serious impact on the global pig industry [

22]. Despite that extensive research has been carried out on ASF, there is still a lack of effective vaccines or antiviral strategies, and the control of ASF mainly relies on strict hygiene measures [

22]. Further, the emergence of low virulence natural mutants has brought greater difficulties to the early diagnosis of ASF and new challenges to ASFV control [

23]. Therefore, in-depth study on the mechanism of pathogenesis and immune evasion of ASFV and establishment of detection methods for early detection and rapid diagnosis are of great significance for the prevention and control of ASF.

Since the outbreak of ASF, researchers have prepared a number of mAbs against different proteins of ASFV, and used the mAbs to establish a variety of ASF detection methods, providing a strong technical support for the detection of ASF [

21,

24,

25,

26]. The ASFV structural protein p54 encoded by E183L is a good target for ASF detection and vaccine development [

14,

27,

28]; however, the expression efficiency of full-length p54 is poor due to the feature of a transmembrane protein. Therefore, we discarded the hydrophobic transmembrane region and chose the intramembrane region with high antigenicity for expression. It has greatly improved the expression efficiency in the BL21 prokaryotic system and a large amount of immunogenic p54 protein was obtained. The three p54 mAbs generated could be successfully used for various immunological experiments, including ELISA, WB and IFA, demonstrating broad spectrum of application.

B cell antigenic epitopes are key factors that determine the antigenicity of viral structural proteins and induce humoral immune responses, helpful for improving the detection efficiency of detection reagents and development of subunit vaccines [

29], especially for key ASFV antigen proteins such as p30, p72 and p54. In addition to two linear epitopes 46-60 aa and one between 149-161aa in the dynein binding region (DBD) [

30], previous studies have demonstrated that p54 protein has different linear epitopes, including 5-9 aa, 10-13 aa, 37-44 aa, 63-72 aa, 65-75 aa, 76-81 aa, 93-113 aa, 103-111 aa, 118-127 aa, 110-118 aa, 112-122 aa, 143-152 aa, 175-184 aa [

24,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36]. In this study, we identified three precise p54 epitopes of 60-72aa, 128-148aa and 163-175aa, which are new antigenic epitopes different from the above reported epitopes. These new epitopes all have reactivity with ASFV positive serum, indicating as natural antigenic epitopes. The p54 new antigenic epitopes can become a new target to improve the detection of ASF, and have a potential application value in the monitoring and control of ASF epidemic.

ASF is mainly distributed in major economic regions with frequent trade in pig industry [

22]. As ASF continues to prevail in a region, ASFV will mutate, causing chronic infection or asymptomatic infection [

37,

38]. In this case, an accurate serological detection method is needed to detect the antibodies of animals to screen out recessive or asymptomatic infected pigs. Therefore, sensitive and reliable serological diagnostic assay of ASF infection is needed. Studies have shown that the epitope based serological detection has advantage to protein antigen based detection, with lower cross reaction and higher specificity [

39,

40]. Here, we demonstrated that the combination of 6B11 and 3E3 peptides mixed at 1:1 as coating antigen can obtain the better detection of serum ASF antibody. Considering that both antigenic peptides of 6B11 and 3E3 are highly conserved across all genotypes I and II ASFV strains, the peptide ELISA is not only useful for detection of genotype I and II ASFV infections, but also useful for detection of recombinant genotype I/II recombinant ASFV infection which appeared recently [

41].

In summary, three mAbs specific for ASFV p54 protein were generated, and three corresponding new linear B cell epitopes were identified. The identified epitopes 60AAIEEEDIQFINP72 and 163MSAIENLRQRNTY175 are highly conserved in genotype I and II ASFV strains. Based on these two peptides, an indirect ELISA detecting p54 antibody was established, which can be applied potentially for early detection and rapid diagnosis of ASF. In addition, the new epitopes identified will also help for development of ASFV subunit vaccine.

Author Contributions

JZ.Z conceived and designed the experiments; JJ.Z, K.Z, S.S, P.H, D.D, H.L, M.X and P.Z performed the experiments; W.Z, N.C and J.B provided the resources; JJ.Z and JZ.Z wrote the paper. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its

Supplementary Materials.

Acknowledgments

This work was partly supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFD1800105), National Science Foundation of China (32473040; 32172867), the 111 Project under Grant D18007, and A Project Funded by the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD). JJ.Z is supported by Research and Practice Innovation Project of Jiangsu Province Graduate Students (SJCX24_2310).

Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Yang, S.; Miao, C.; Liu, W.; Zhang, G.; Shao, J.; Chang, H. , Structure and function of African swine fever virus proteins: Current understanding. Front Microbiol 2023, 14, 1043129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salguero, F. J. , Comparative Pathology and Pathogenesis of African Swine Fever Infection in Swine. Front Vet Sci 2020, 7, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudreault, N. N.; Madden, D. W.; Wilson, W. C.; Trujillo, J. D.; Richt, J. A. , African Swine Fever Virus: An Emerging DNA Arbovirus. Front Vet Sci 2020, 7, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penrith, M. L.; Vosloo, W.; Jori, F.; Bastos, A. D. , African swine fever virus eradication in Africa. Virus Res 2013, 173, 228–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolbasov, D.; Titov, I.; Tsybanov, S.; Gogin, A.; Malogolovkin, A. , African Swine Fever Virus, Siberia, Russia, 2017. Emerg Infect Dis 2018, 24, 796–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Li, N.; Luo, Y.; Liu, Y.; Miao, F.; Chen, T.; Zhang, S.; Cao, P.; Li, X.; Tian, K.; Qiu, H. J.; Hu, R. , Emergence of African Swine Fever in China, 2018. Transbound Emerg Dis 2018, 65, 1482–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas, M. L.; Andrés, G. , African swine fever virus morphogenesis. Virus Res 2013, 173, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, N.; Ou, Y.; Pejsak, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J. , Roles of African Swine Fever Virus Structural Proteins in Viral Infection. J Vet Res 2017, 61, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, J. M.; García-Escudero, R.; Salas, M. L.; Andrés, G. , African swine fever virus structural protein p54 is essential for the recruitment of envelope precursors to assembly sites. J Virol 2004, 78, 4299–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcaraz, C.; Brun, A.; Ruiz-Gonzalvo, F.; Escribano, J. M. Cell culture propagation modifies the African swine fever virus replication phenotype in macrophages and generates viral subpopulations differing in protein p54. Virus Res 1992, 23, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, C.; Miskin, J.; Hernáez, B.; Fernandez-Zapatero, P.; Soto, L.; Cantó, C.; Rodríguez-Crespo, I.; Dixon, L.; Escribano, J. M. , African swine fever virus protein p54 interacts with the microtubular motor complex through direct binding to light-chain dynein. J Virol 2001, 75, 9819–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Mayoral, M. F.; Rodríguez-Crespo, I.; Bruix, M. , Structural models of DYNLL1 with interacting partners: African swine fever virus protein p54 and postsynaptic scaffolding protein gephyrin. FEBS Lett 2011, 585, 53–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernáez, B.; Díaz-Gil, G.; García-Gallo, M.; Ignacio Quetglas, J.; Rodríguez-Crespo, I.; Dixon, L.; Escribano, J. M.; Alonso, C. , The African swine fever virus dynein-binding protein p54 induces infected cell apoptosis. FEBS Lett 2004, 569, 224–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neilan, J. G.; Zsak, L.; Lu, Z.; Burrage, T. G.; Kutish, G. F.; Rock, D. L. , Neutralizing antibodies to African swine fever virus proteins p30, p54, and p72 are not sufficient for antibody-mediated protection. Virology 2004, 319, 337–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Puertas, P.; Rodríguez, F.; Oviedo, J. M.; Brun, A.; Alonso, C.; Escribano, J. M. , The African swine fever virus proteins p54 and p30 are involved in two distinct steps of virus attachment and both contribute to the antibody-mediated protective immune response. Virology 1998, 243, 461–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, A. L.; Parkhouse, R. M. E.; Penedos, A. R.; Martins, C.; Leitão, A. , Systematic analysis of longitudinal serological responses of pigs infected experimentally with African swine fever virus. J Gen Virol 2007, 88 Pt 9, 2426–2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo, C.; Reis, A. L.; Kalema-Zikusoka, G.; Malta, J.; Soler, A.; Blanco, E.; Parkhouse, R. M.; Leitão, A. , Recombinant antigen targets for serodiagnosis of African swine fever. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2009, 16, 1012–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyilagha, C.; Quizon, K.; Zhmendak, D.; El Kanoa, I.; Truong, T.; Ambagala, T.; Clavijo, A.; Le, V. P.; Babiuk, S.; Ambagala, A. , Development and Validation of an Indirect and Blocking ELISA for the Serological Diagnosis of African Swine Fever. Pathogens 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, N.; Cao, Q.; Liu, A.; Zhang, J.; Han, H.; Jiao, J.; He, P.; Sun, Z.; Xu, Z.; Zheng, W.; Jiang, S.; Chen, N.; Bai, J.; Zhu, J. , Identification of a New Conserved Antigenic Epitope by Specific Monoclonal Antibodies Targeting the African Swine Fever Virus Capsid Protein p17. Vet Sci 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Q.; Li, S.; Cao, Q.; Gu, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, K.; Zheng, W.; Chen, N.; Shang, S.; Zhu, J. , Development of Specific Monoclonal Antibodies against Porcine RIG-I-like Receptors Revealed the Species Specificity. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, K.; Sun, S.; He, P.; Deng, D.; Zhang, P.; Zheng, W.; Chen, N.; Zhu, J. , Specific Monoclonal Antibodies against African Swine Fever Virus Protease pS273R Revealed a Novel and Conserved Antigenic Epitope. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, K.; Liu, J.; Wang, L.; Fan, S.; Li, Z.; Li, Y.; Yi, L.; Ding, H.; Zhao, M.; Chen, J. , Current State of Global African Swine Fever Vaccine Development under the Prevalence and Transmission of ASF in China. Vaccines (Basel) 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, E.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Z.; He, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, W.; Huang, L.; Xi, F.; Huangfu, H.; Tsegay, G.; Huo, H.; Sun, J.; Tian, Z.; Xia, W.; Yu, X.; Li, F.; Liu, R.; Guan, Y.; Zhao, D.; Bu, Z. , Emergence and prevalence of naturally occurring lower virulent African swine fever viruses in domestic pigs in China in 2020. Sci China Life Sci 2021, 64, 752–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovan, V.; Murgia, M. V.; Wu, P.; Lowe, A. D.; Jia, W.; Rowland, R. R. R. , Epitope mapping of African swine fever virus (ASFV) structural protein, p54. Virus Res 2020, 279, 197871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimerman, M. E.; Murgia, M. V.; Wu, P.; Lowe, A. D.; Jia, W.; Rowland, R. R. , Linear epitopes in African swine fever virus p72 recognized by monoclonal antibodies prepared against baculovirus-expressed antigen. J Vet Diagn Invest 2018, 30, 406–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Qiao, S.; Liu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Tong, W.; Dong, S.; Liu, C.; Jiang, Y.; Guo, Z.; Zheng, H.; Zhao, R.; Tong, G.; Li, G.; Gao, F. , A highly efficient indirect ELISA and monoclonal antibody established against African swine fever virus pK205R. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 1103166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubillos, C.; Gómez-Sebastian, S.; Moreno, N.; Nuñez, M. C.; Mulumba-Mfumu, L. K.; Quembo, C. J.; Heath, L.; Etter, E. M.; Jori, F.; Escribano, J. M.; Blanco, E. , African swine fever virus serodiagnosis: a general review with a focus on the analyses of African serum samples. Virus Res 2013, 173, 159–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netherton, C. L.; Goatley, L. C.; Reis, A. L.; Portugal, R.; Nash, R. H.; Morgan, S. B.; Gault, L.; Nieto, R.; Norlin, V.; Gallardo, C.; Ho, C. S.; Sánchez-Cordón, P. J.; Taylor, G.; Dixon, L. K. , Identification and Immunogenicity of African Swine Fever Virus Antigens. Front Immunol 2019, 10, 1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potocnakova, L.; Bhide, M.; Pulzova, L. B. , An Introduction to B-Cell Epitope Mapping and In Silico Epitope Prediction. J Immunol Res 2016, 2016, 6760830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmet, C.; Coelho-Cruz, B.; Mehn, D.; Colpo, P.; Ruiz-Moreno, A. , ASFV epitope mapping by high density peptides microarrays. Virus Res 2024, 339, 199287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Han, D.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, K.; Du, N.; Tong, W.; Li, G.; Zheng, H.; Liu, C.; Gao, F.; Tong, G. , Identification of one novel epitope targeting p54 protein of African swine fever virus using monoclonal antibody and development of a capable ELISA. Res Vet Sci 2021, 141, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Jiang, M.; Liu, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Chen, Y.; Ding, P.; Wang, Y.; Pang, W.; Qi, Y.; Zhang, G. , Development and characterization of monoclonal antibodies against the N-terminal domain of African swine fever virus structural protein, p54. Int J Biol Macromol 2021, 180, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Wang, G.; Dong, H.; Wu, S.; Du, Y.; Wan, B.; Ji, P.; Wu, Y.; Jiang, D.; Zhuang, G.; Duan, H.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, A. , Identification of a Linear B Cell Epitope on p54 of African Swine Fever Virus Using Nanobodies as a Novel Tool. Microbiol Spectr 2023, 11, e0336222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, N.; Li, C.; Hou, H.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, A.; Han, S.; Wan, B.; Wu, Y.; He, H.; Wang, N.; Du, Y. , A Novel Linear B-Cell Epitope on the P54 Protein of African Swine Fever Virus Identified Using Monoclonal Antibodies. Viruses 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Xia, T.; Bai, J.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, H.; Jiang, P. , Preparation of Monoclonal Antibodies against the Viral p54 Protein and a Blocking ELISA for Detection of the Antibody against African Swine Fever Virus. Viruses 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Cao, C.; Yang, Z.; Jia, W. , Identification of a conservative site in the African swine fever virus p54 protein and its preliminary application in a serological assay. J Vet Sci 2022, 23, e55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo, C.; Soler, A.; Nurmoja, I.; Cano-Gómez, C.; Cvetkova, S.; Frant, M.; Woźniakowski, G.; Simón, A.; Pérez, C.; Nieto, R.; Arias, M. , Dynamics of African swine fever virus (ASFV) infection in domestic pigs infected with virulent, moderate virulent and attenuated genotype II ASFV European isolates. Transbound Emerg Dis 2021, 68, 2826–2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C, G.; I, N.; A, S.; V, D.; A, S.; E, M.; C, P.; R, N.; M, A. , Evolution in Europe of African swine fever genotype II viruses from highly to moderately virulent. Vet Microbiol 2018, 219, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tesfagaber, W.; Wang, L.; Tsegay, G.; Hagoss, Y. T.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Huangfu, H.; Xi, F.; Li, F.; Sun, E.; Bu, Z.; Zhao, D. , Characterization of Anti-p54 Monoclonal Antibodies and Their Potential Use for African Swine Fever Virus Diagnosis. Pathogens 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Chen, J.; Peng, Y.; Xie, Y.; Xiao, Y. , A Promising Tool in Serological Diagnosis: Current Research Progress of Antigenic Epitopes in Infectious Diseases. Pathogens 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Sun, E.; Huang, L.; Ding, L.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Shen, D.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Ren, T.; Wang, W.; Li, F.; He, X.; Bu, Z. , Highly lethal genotype I and II recombinant African swine fever viruses detected in pigs. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 3096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).