1. Introduction

The cosmetics industry is a dynamic and constantly evolving sector, with global prominence in key markets such as the European Union (EU), the United States (US), China, Brazil and Japan [

1]. Today, industry develops and produces innovative and successful products. This leads consumers to select cosmetic creams on the basis of performance and efficacy [

2].

In Ecuador, the consumption of cosmetics for personal care is of significant importance, representing 1.6% of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and experiencing an annual growth of 10% [

3]. Based on recent research Gordillo López

, et al. [

4] mentions that the country consumes approximately 51.5 million beauty products per year, equivalent to an average of 3.09 units per person.

From a technical perspective, a cosmetic emulsion may be defined as a semi-solid system composed of two distinct phases: an aqueous and an oily phase, which are kept stable by the addition of an emulsifying agent [

5]. As they are thermodynamically unstable, energy is required for their formation [

6]. Its basic composition is enriched by the presence of active ingredients, preservatives, fragrances and flavourings, among other components [

7].

However, cosmetic emulsions are classified into several groups, the most representative of which are: water-in-oil (W/O), where the water is dispersed in a continuous oil phase, and the most commonly used formulation is oil-in-water (O/W), in which the continuous phase is aqueous and the oil is dispersed in it [

8]. These emulsions have the function of softening the skin and making it supple [

9]. In addition, the most important properties include viscosity, colour, stability, ease of dilution and formation [

10].

Increasing market interest in formulated products (emulsions) has driven the advancement of innovative approaches to their design. Today, scale-up is done by trial-and-error methods based on modeling [

11]. According to Ruiz and Álvarez [

12], this process is traditionally done on the basis of dimensional analysis, geometric similarity, and empirical relationships from a data set.

Scaling up from the laboratory to the industrial environment is therefore a critical and decisive step during process design [

13]. In general, newtonian fluids are simpler to scale [

14]. In contrast, non-Newtonian or in this case emulsions, are more complex due to changes in their properties such as viscosity and flow conditions [

15].

In general, the process of scaling up involves obtaining data at different levels, on a laboratory scale it allows us to take data to design another plant of a different size. It is therefore crucial that a product made in small quantities must present the same properties and characteristics as one produced in larger series [

16].

Research by Burakova, et al. (2022) suggests that to scale up an emulsion technology it is necessary to consider the risks that can lead to the production of heterogeneous and unstable creams. Another study by Türedi and Acaralı [

17], argues that it depends on the correct choice of stirrer speed, mixing time and process temperature.

According to Burakova et al. (2022), they developed a technology to produce emulsions based on dry extract of bergenia (Bergenia crassifolia) under laboratory conditions. In this regard, they used 3 pilot series for production, considering possible risks such as mixer speed, mixing time, temperature etc., where they obtained a stable cosmetic product.

Likewise, Campos Prada [

18], proposed the scaling up of the mixing process of concentrated O/W emulsions in order to study their dynamics under controlled hydrodynamic conditions. In the same way Restrepo Jiménez [

19] conducted a similar scaling study, using the multi-scale design to observe whether more pumping of the agitator reduces the energy consumption and whether the energy consumption remains constant.

Moreover, May-Masnou, et al., (2013), add that the quality and final properties of emulsions are linked to various process factors. Even small changes in the agitation speed, the way in which the components are added, or the size of the container can cause variations in the product, in addition to the loss of raw material, time and economic resources. Therefore, it is essential to perform a scaling analysis of these procedures and to study the impact of the variables to predict their behaviors and optimization at the industrial level, by saving resources and time in inefficient trials.

Although several attempts have been made to bring the laboratory scale-up of certain technological processes to pilot scale, they are not sufficient, due to the lack of information on experimental data to design it. For this reason, the aim of the study is to carry out the conceptual design of the process of obtaining cosmetic cream.

2. Materials and Methods

The methodology applied for technological process design (

Figure 2), shows a scheme adapted by Suaza Montalvo [

20] for the generation of the scaling proposal of the technological process at an experimental level. The procedures involved in each stage are described below, as well as the objective of each of them and the tools that were used.

Figure 1.

Methodology applied to the design proposal for technological process design.

Figure 1.

Methodology applied to the design proposal for technological process design.

Step 1. Information retrieval and experimental data collection

The aim of this stage was to recover all the information involved in the processes of extracting vegetable oils and making cosmetic cream. In terms of operating times, temperatures used, quantities added, and operations involved in each of the processes and waste generated. For this purpose, detailed and systematic annotations were made to accurately record the observations, thus enabling a thorough understanding of the procedures and their variations.

Step 2. Identification of operations and equipment proposal

With the information gathered, we proceeded to identify the operations, unit processes and equipment within the framework of the technological process. Those related to the separation of mixtures or chemical reactions were especially highlighted. This detailed identification allowed a precise analysis of each stage, laying the groundwork for future studies and optimizations by categorizing, classifying operations and processes according to their nature and function. This systematic approach provided a comprehensive understanding of the complexity of the system and is essential to identify critical areas for the efficiency of the technology.

Step 3. Construction and description of the diagrams

Once the relevant operations had been identified, the next stage was the construction of the block diagram. This step involved the integration of the procedures identified in the previous stage, as well as the inclusion of the corresponding equipment in the process flow diagram. Using SuperPro Designer V10.0, the Gantt chart was established, representing the flow chart of the activities according to the actions performed. In addition, it covered the ingredients and the specific operational conditions. This systematic approach not only allowed a comprehensive visualization of the different operations and their sequence but also facilitated the detailed planning of the resources and times associated with each stage, resulting in efficient and optimized production management. The steps proposed by Pérez-Martínez

, et al. [

21] for the process design were followed.

2.3 Case studies

Concerning the case studies, the methodology described in the previous section was used to obtain the oils (Morete oil and Ungurahua oil), as well as to produce cosmetic cream. The process started with data collection and identification of operations at laboratory level.

Table 1 shows the formulation used to make 1 kg of cosmetic cream, with the ingredients and quantities used.

3. Results

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

3.1. Step 1 Information Retrieval and Experimental Data Collection

This process began with the collection of data at laboratory level from the case studies, starting with the extraction of the vegetable oils.

Extraction of oil from Morete (Mauritia flexuosa L.f.)

The fruit of M. flexuosa were acquired at the ‘Mercado del Centro Agrícola’ in the city of Puyo, Pastaza province, in September 2023.

The Morete fruits were selected and separated from those showing any damage. Subsequently, 35 kg of fruit was weighed, cleaned and washed with 12.5 L of water to remove impurities such as soil. Then, the fruits were softened with 20 L of water at a temperature of 60 °C for two hours to facilitate the removal of the seed. The rind and pulp of the seed were then separated from the fruit by hand.

As a result of this procedure, 8 kg of pulp and 27 kg of residue were obtained. The pulp was subjected to a drying process for a period of 24 hours at a temperature of 60 °C, resulting in 3000 g of dry pulp. The oil is then extracted using the decoction method. At this stage, the pulp is boiled to extract the oil contained in it, obtaining 325 mL or 280.82 g of the product. The percentage yield at this stage is 9.36 %, which is the proportion of oil in relation to the weight of the dehydrated pulp obtained after the drying process.

Extraction of oil from Ungurahua (Oenocarpus bataua Mart)

The fruit of O. bataua were acquired at the ‘Mercado del Centro Agrícola’ in the city of Puyo, Pastaza province, in September 2023

3498.30 g of fruit were received and washed to remove moulds and impurities. The plant material was then softened by boiling in 6996.6 mL of water. After boiling, the fruit was introduced and kept for a period of two hours to allow softening and pulp extraction. The husk and pulp were then ground. After obtaining 1097.53 g of ground pulp, the decoction process was carried out to extract the oil. This procedure resulted in obtaining a total of 19 mL of oil, equivalent to 17.16 g with a yield of 0.6 %.

Emulsion production

For the preparation of the cream, after obtaining the raw material in optimal conditions, the ingredients to produce one kg of the final product were weighed. This process was divided into two parts: an aqueous part, consisting of 645 g of purified sterile water, and an oily part, containing 3 g of Montanov 202, ten g of Montanov 68 (emulsifiers), 155 g of cocoa butter, 44 g of Morete, 102 g of Ungurahua and ten g of preservative. Previously, the mixtures were subjected to a water bath at a temperature of 75 °C for 20 minutes, making sure to achieve liquid homogeneity between all ingredients (

Figure 2).

Once the desired temperature was reached and the ingredients were ready, they were transferred to the homogeniser/emulsifier at 7000 rpm for 40 minutes, where the water was added slowly to the oil phase to achieve a uniform fluid.

3.2. Step 2. Identification of the operations

The procedures carried out at laboratory level are shown, as well as the unitary operations used to obtain oil from Morete (

M. flexuosa). Four alternatives for oil extraction are proposed: decoction, solvent, cold and hot pressing. After evaluating these alternatives, it is determined that cold pressing is the optimal method. Furthermore, the corresponding equipment to be used to carry out the extraction process is specified (

Table 2).

The processes carried out at laboratory level and the unitary operations used to obtain oil from Ungurahua fruits (

O. bataua) are detailed. Four alternatives for oil extraction are proposed: decoction, solvent, cold and hot pressing. After evaluating the options, it is determined that cold pressing is the optimal method. The corresponding equipment to be used to carry out this extraction process is also specified (

Table 2).

The corresponding data for each of the stages carried out at laboratory level are presented, together with the unit operations identified to produce the cosmetic emulsion. Likewise, the use of the turbo emulsifier is suggested as the optimal equipment to carry out each of these operations (

Table 3).

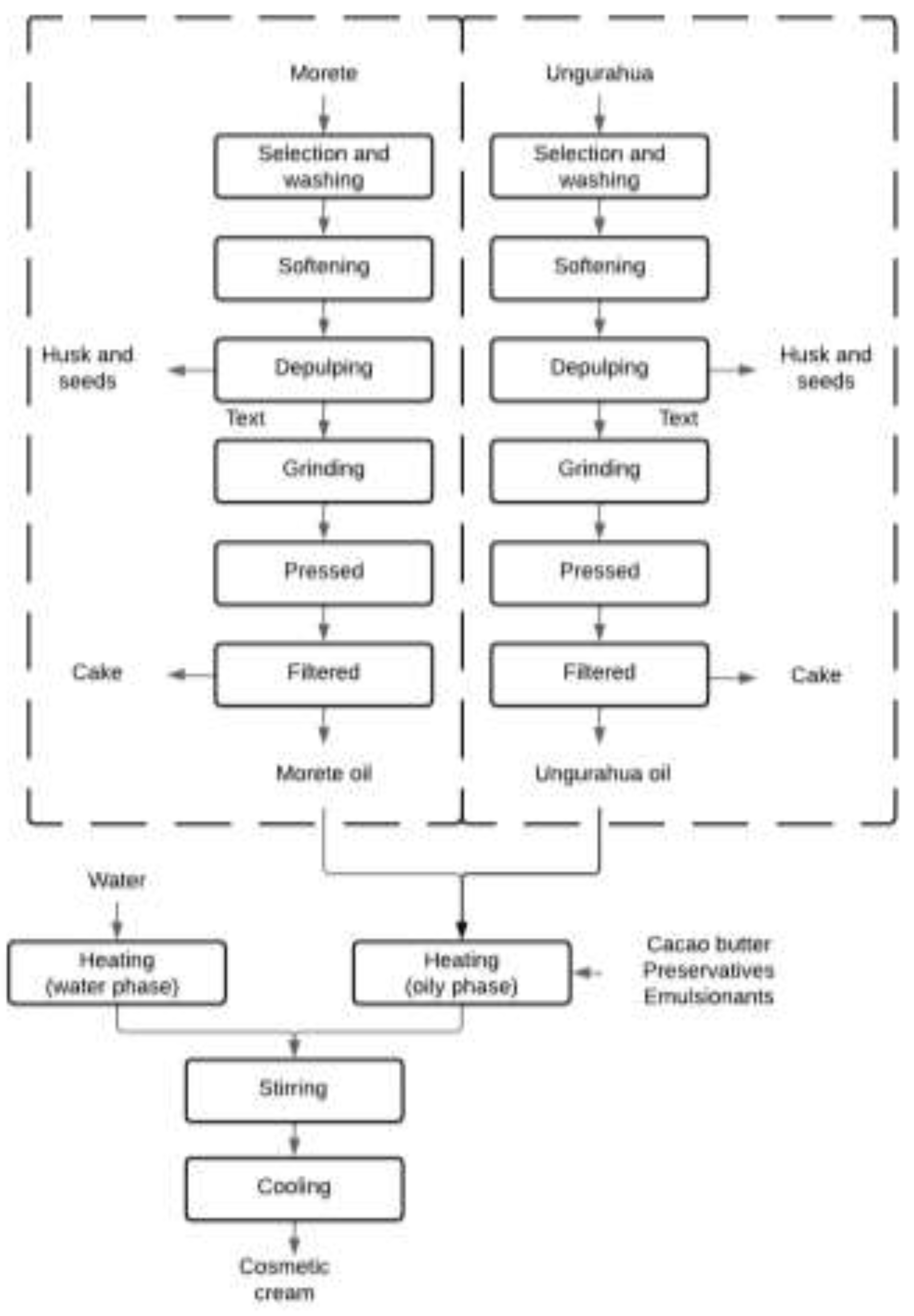

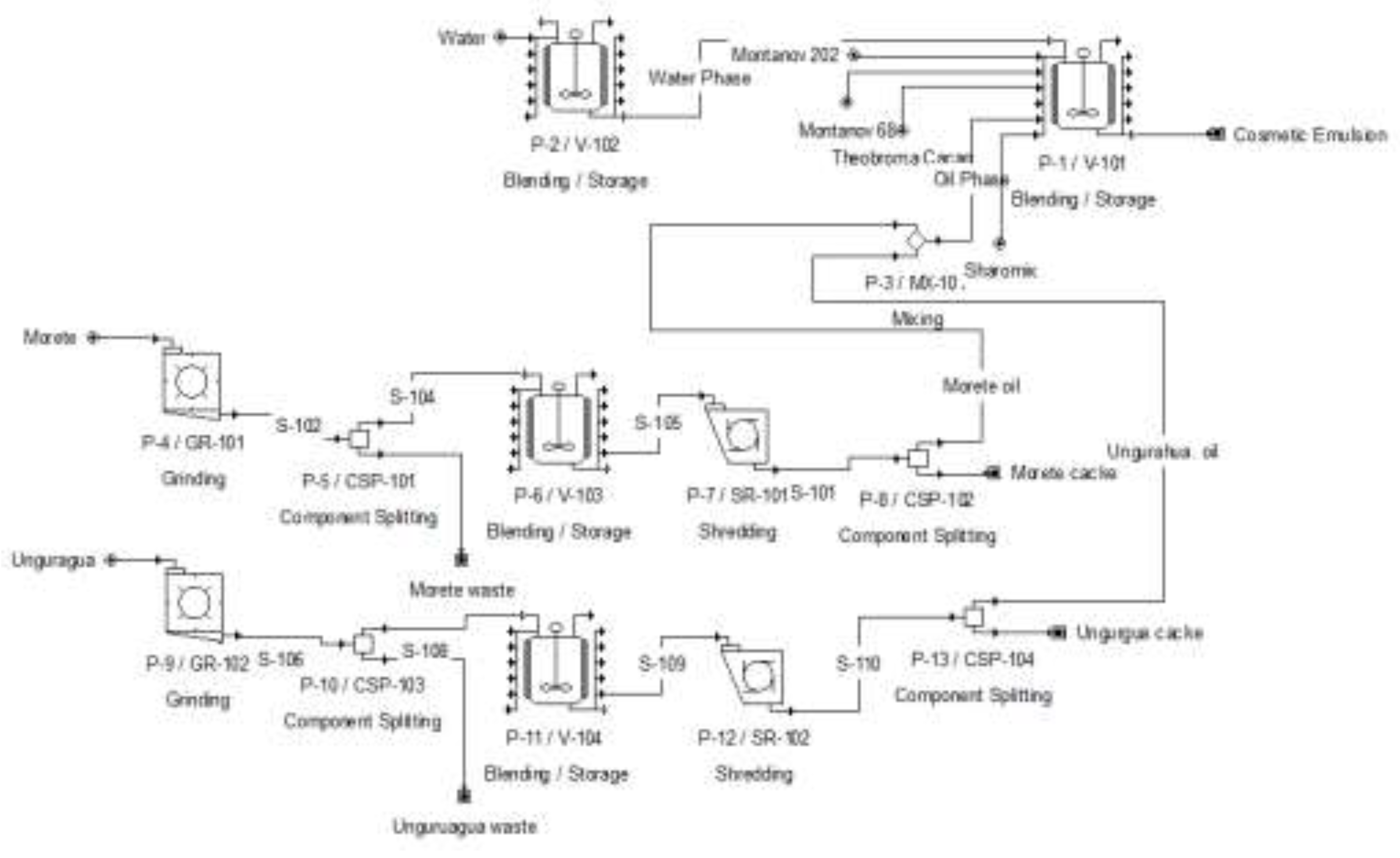

3.3. Step 3. Construction/ Description of the Diagrams

After completing the previous stage, the diagrams that will facilitate the identification of the processes, quantities and production time of the cosmetic cream are drawn up and described. The block diagram (

Figure 3a) shows how technology is integrated with the unitary operations necessary to obtain cosmetic cream from the oils (Morete oil and Ungurahua oil).

The technological process used in the extraction of vegetable oils from Morete and Ungurahua uses various technologies. First, the raw materials are selected and meticulously washed. The fruit is then softened at a temperature of 100 °C for one hour to facilitate pulping, which separates the pulp from the fruit and separates the seed and peel as residues. The resulting pulp is crushed to facilitate subsequent pressing. Once the oil is obtained, a filtering process is carried out to obtain a final product free of impurities and residues, and finally to use it in the production of cosmetic cream.

The production of the cosmetic cream starts with the simultaneous incorporation of the two phases, oily and aqueous. The first phase involves heating a combination of cocoa butter, emulsifiers (Montanov 68, 202), oils and preservative (Sharomix), while the second phase comprises exclusively water. This procedure is carried out at a temperature of 70-80 °C for a period of 40 minutes.

Then, both phases are mixed at the end of the heating process, and by constant stirring at 7000 rpm, the aqueous phase is incorporated into the oily phase. Finally, once the desired emulsion is achieved, it is cooled to room temperature.

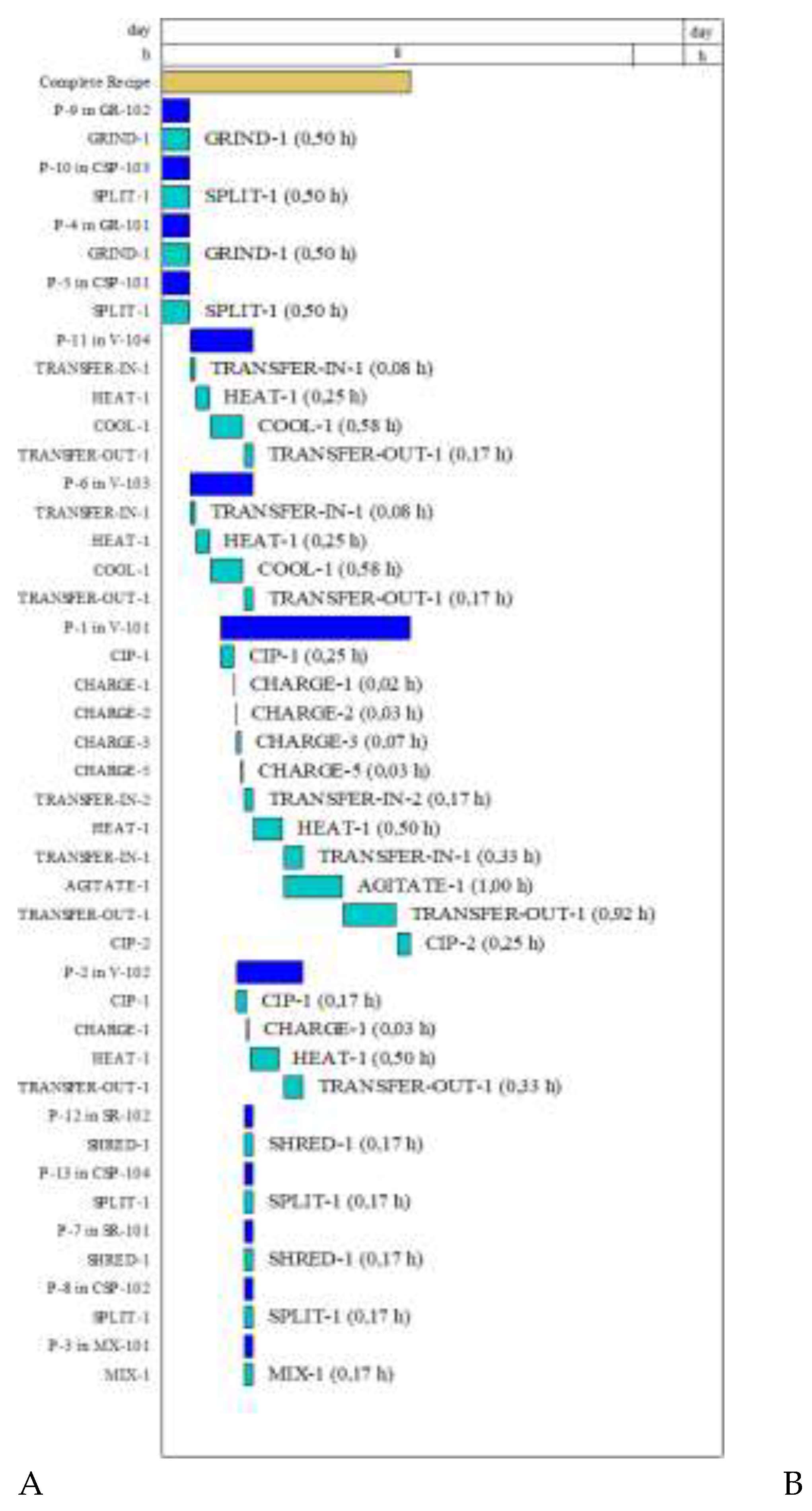

The above-mentioned procedures coincide with the Gantt Chart (

Figure 3b). It starts with the extraction of Morete and Ungurahua oils. Once obtained, both oils pass simultaneously to the heating phase of the aqueous and oily phase in separate equipment, both starting at the same temperature and time. At the end of this process, the aqueous phase is combined with the oily phase to homogenize and form the desired emulsion. The total duration of the process to produce cosmetic cream is 4.25 hours.

In the Gantt chart (

Figure 5), the progress of the activities and the logical sequence for carrying out both phases are graphically summarized, given the dependence between them. For this, the aqueous phase is prepared and then the lipid phase, since it is a W/O emulsion. Each activity is represented vertically, with its start and duration indicated by a horizontal line along a time scale [

22].

In the process flow diagram (

Figure 4) you can see the technology containing two turbo emulsifiers with a capacity of 10 kg: the first one is used to prepare the aqueous phase, and the second one is used for the oily phase to obtain emulsion. This process follows detailed operations (

Figure 3) to obtain cosmetic cream.

In the same way we can see in (

Figure 5), the process flow diagram for obtaining oils (Morete oil and Ungurahua oil). The process begins with the entry of the fruits into the pulper to separate the seeds and peels from the fruit. Subsequently, the fruits are cooked to soften them and obtain the condensate as a residue. Once the fruits have a smooth texture, they are crushed and subjected to cold pressing to extract the oil, and as a residue the Morete and Ungurahua cake. The oil obtained is filtered to eliminate the particles present, resulting in the final product being vegetable oils.

Mass and energy balance, consumption vs. availability of PM and environmental compatibility of technology

Table 4 presents a comprehensive analysis of the consumption of environmental indicators linked to the annual production of 4717.48 kg of cosmetic cream. This analysis provides a detailed overview of the consumption of raw materials, water and energy, as well as the amount of waste generated from the initial waste and the residual cake resulting from the Morete and Ungurahua pressing process. The data presented provides a clear and accurate picture of the environmental footprint associated with the production of cosmetic cream, allowing for a comprehensive technical assessment of its environmental impact.

Equipment sizing and procurement cost

For the sizing and acquisition cost of the equipment, it is essential to establish the entire manufacturing process of the technologies.

Table 5 shows the equipment involved in the processes of obtaining vegetable oils and cosmetic cream, the design parameter that characterizes each one of them, the quantity and the acquisition cost of each one of them. The acquisition cost of all the equipment amounts to 126 000.00 USD.

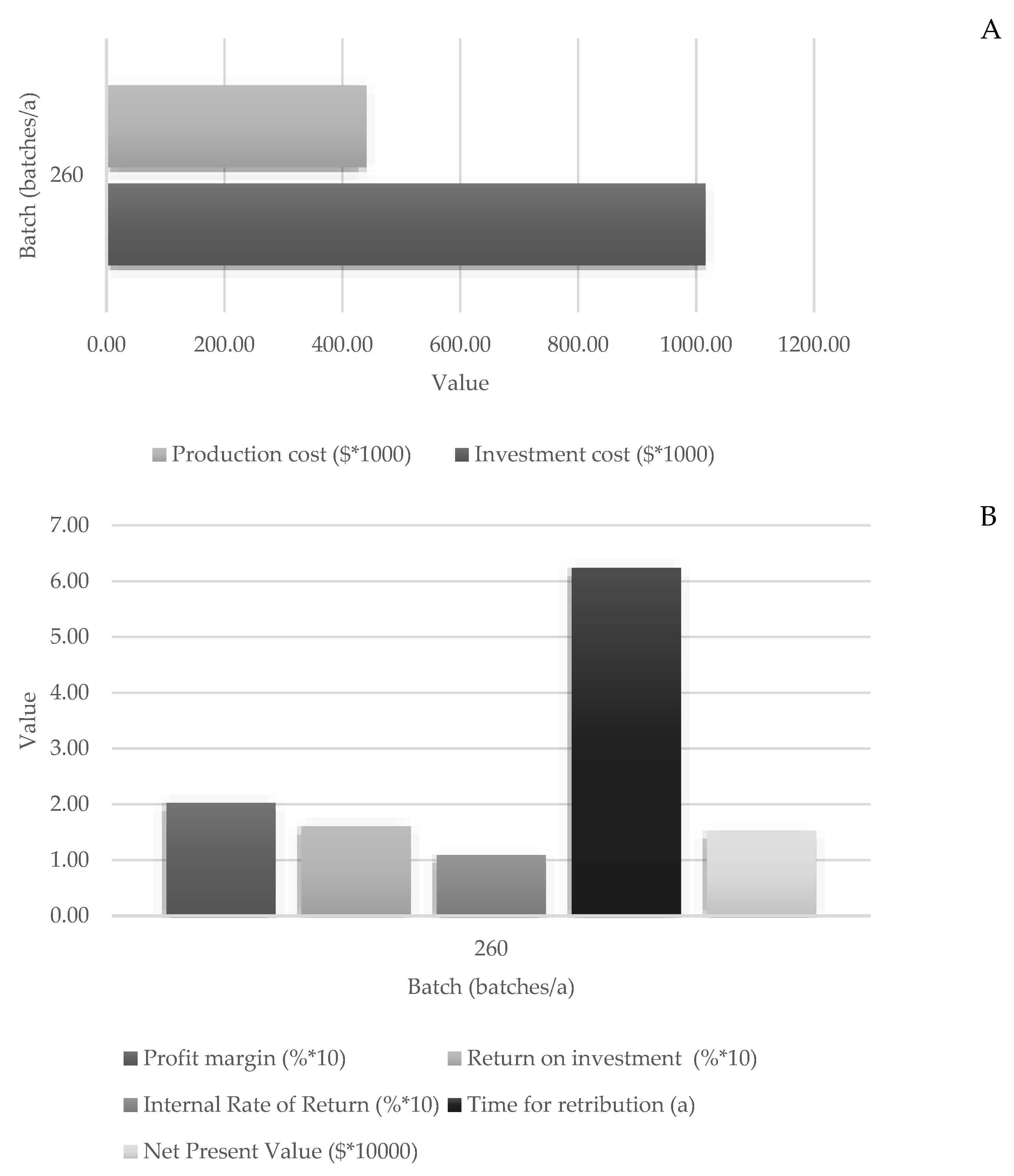

Analysis and economic feasibility

The investment cost (

Figure 5a) for 260 batches is

$ 1016000.00 while the production cost (Figure 6a) is lower compared to the investment with a value of

$ 44100.00 per year. The Net Present value (NPV) determines the different costs and benefits of technological investment, which, to produce the cosmetic cream was positive for the number of batches with a value of

$216,000.00. This value indicates that it is possible to recover the investment and is economically feasible, which leads to an increase in profitability (

Figure 5b). On the other hand, the payback time is 6.24 years, which indicates a timely payback. While the Internal Rate of Return (IRR) is positive, indicating higher profitability. The profit margin and return on investment show positive values of 20.22% and 16.04% respectively. Therefore, it suggests that the operation is profitable and generates profits that exceed the initial capital.

Figure 5.

Results of the economic analysis: (a) Investment and production costs; (b) Dynamic economic and profitability indicators.

Figure 5.

Results of the economic analysis: (a) Investment and production costs; (b) Dynamic economic and profitability indicators.

4. Discussion

4.1. Stage 1. Information Retrieval and Experimental Data Collection Morete oil extraction

The extraction yield of Morete by the decoction method was 9.36% relative to the dehydrated pulp. Rivera

, et al. [

23] in his research suggests that the most efficient method for Morete oil extraction is by using the pulp under cold pressing, with a pre-treatment at 85 °C for a period of 10 minutes, generating a yield of 56.77%. Whereas Rivera Chasiquiza [

24], reported the oil content in Morete pulp by mechanical pressing of 59.42%, when heat treatment was applied and the rindless fruit was used at 85 °C for 10 min. As reported by Paredes Amasifuen [

25] shows that by applying heat treatment prior to oil extraction, a high fat percentage of more than 19.0% is achieved. The process involves heating, crushing, extraction with a manual press, and separation by decantation and filtration. Furthermore, another study by Adrianzén

, et al. [

26] comments that the amount of oil extracted is directly related to the heating temperature of the pulp. They also show that this percentage decreases when using the pulp with peel during pre-treatment prior to pressing.

Ungurahua oil extraction

The yield using the decoction method of dried Ungurahua pulp was 0.6%. This figure is significantly below the results reported by various authors who have used different techniques during pulp softening and extraction methods, which could contribute to obtaining higher yields. The procedures used to obtain oil from Ungurahua are like those reported by the following authors [

27,

28], who agree on the seed softening time, set at 2 hours. According to Peña

, et al. [

29], reports that a yield of 19.06% was obtained using the pressing method. On the other hand, the methodology described by Chaves Yela

, et al. [

30] to extract oil from Ungurahua, begins with the harvesting and storage of ripe fruits for 24 hours, followed by washing, selection, softening, pulping, and filtration at 130 °C. Emphasis is placed on the process of filtering with cloth as a guarantee of the oil's purity, and proper storage ensures the preservation of its properties and a high quality product.

Cream preparation

The process for the preparation of the cosmetic cream involved the separate heating of the lipid and aqueous phases. Once the components of the oil phase reached a liquid state and the required temperature, the aqueous phase was combined with the oil phase to obtain the desired cosmetic emulsion. This coincides with the phase inversion method, also known as the indirect method, used by [

31,

32]. In this method, the oil phase is heated separately from the aqueous phase, and through continuous stirring, the aqueous phase is gradually incorporated into the oil phase until the desired emulsion is achieved.

4.2. Stage 2. Identification of Operations and Equipment Proposal

Oil extraction

The study carried out by Rivera et al., (2022) highlights that cold pressing, complemented by preheating at 85 °C for 10 minutes, represents the most efficient option in terms of yield, with a production of over 56.77%. This method preserves the functional properties of the product during extraction, unlike hot pressing, which prevents the loss of volatile components observed in decoction extraction methods. In addition, it is noted that this technique does not cause potential skin irritation associated with the use of hexane or others organic solvents, making it a safer and more effective alternative.

The equipment selected for the extraction of oils from both Morete and Ungurahua is the same, because these two fruits share similar characteristics in terms of their softening, pulping and oil extraction. For this choice, we have based ourselves on the information provided by Aliaga Zumaeta and Quispe Alarcon [

33] where they use a pulper designed to separate the pulp from the fibrous material, pips and skin of various fruits. This equipment, made of stainless steel, consists of brushes and nylon that rotate at high speeds, which facilitates the breaking of the fruit. It has a processing capacity of 1,200 kg per hour. Finally, a pressure and temperature regulator are used. It has a capacity of 370 kg/h. The pressure applied helps to raise the temperature of the pulp, thus helping to obtain a high-quality oil.

Cosmetic emulsion production

In the selection of the technology, we were guided by the methodology proposed by Mosquera, Noriega, Tapia and Pérez [

32], which involves the creation of a water-in-oil (W/O) cosmetic emulsion and rapid agitation and by a cooling process with slow agitation.

For the selection of the necessary equipment, we relied on the work of Romero

, et al. [

34] in which they suggest the use of an emulsifier made of stainless steel. This equipment is designed to heat and withstand both external and internal pressures, as well as vacuum. In addition, it has the capacity to mix at different agitation speeds, adapting to the viscosity of the emulsion. Finally, the device has a cooling system by means of a double chamber through which water and steam circulate. For these reasons, it is considered that this equipment is the most suitable for carrying out the cosmetic cream production process.

4.3. Step 3. Construction/Description of the Diagrams

The time required to produce the cosmetic cream is 4.25 hours. Therefore, it is feasible to produce 2 or more batches per day. In comparison, a research carried out by Aguilar [

35] for the production of 10 kg of cosmetic cream, the total time is 0.52 hours. In the heating phase, Zurita Acosta and López Pérez [

36] They point out that they were carried out in a jacketed mixing tank at 65-75 °C for 20 minutes. Also Chauhan and Gupta [

37], use the melting kettle for heating at 90°c for 10 to 15 minutes until the oils and fats are melted. In the mixing and melting process, [

38,

39] report that it is kept running for 15 to 20 minutes until a homogeneous mixture is obtained.

Mass and energy balance, consumption vs. availability of PM and environmental compatibility of technology

The raw materials (PM) used in this context are of a renewable nature, so the technology used is environmentally compatible. In addition, a minimal amount of solid waste is generated, as detailed in

Table 5. The small amounts of waste disposal, together with the efficient use of raw materials and energy, as well as the implementation of sustainable practices in the production and collection of these raw materials, ensure that the proposed technology complies with the recommendations set out by Bom et al. (2019) and [

40].

Analysis and economic feasibility

The values obtained in the production of 260 batches/a, evaluated through dynamic economic indicators, indicate that the process is economically viable and that the recovery of the investment is feasible, which is in line with the research of [

41,

42]. In addition, both product quality and market demand suggest the possibility of increasing the quantity of batches produced, resulting in an increase in revenue and a reduction in the time required to recover the investment, as noted by [

43].

Authors should discuss the results and how they can be interpreted from the perspective of previous studies and of the working hypotheses. The findings and their implications should be discussed in the broadest context possible. Future research directions may also be highlighted.

5. Conclusions

With this research, it has been possible to prove that, to carry out the conceptual design of a technological process, it is essential to obtain experimental data that allows its subsequent scaling up. The unit operations, the equipment and the operating time of the case study designed in this research are an example of the previous statement.

In the conceptual design for obtaining cosmetic cream, an operating time of 4.25 hours is estimated, which would allow the production of two or more batches per day, depending on demand. Furthermore, the initial investment is expected to be recovered within 6.24 years.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, A.P.M. and E.G.Y.; methodology, I.S.G.G. and M.E.F.F.; software, A.P.M. and R.A.-N; formal analysis, L.S., M.R, and L.R.B.S.; investigation, E.G.Y.; and L.R.B.S.; writing—original draft preparation, R.A.-N. and E.G.Y.; writing—review and editing, M.R. and L.S.; supervision, A.P.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript”.

Funding

This study was funded by Universidad Estatal Amazónica in Puyo, Ecuador and it has been has been completed internally the project “Development of new agro-industrial products with high added value from fixed oils, essential oils and plant extracts rich in antioxidant or antimicrobial metabolites”.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable. All relevant data are included within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| UO |

Unitary Operations |

| Equip J |

Equipment |

| OE |

Oil extraction |

References

- Bermond, C.; Cherrad, S.; Trainoy, A.; Ngari, C.; Poulet, V. Real-time qpcr to evaluate bacterial contamination of cosmetic cream and the efficiency of protective ingredients. Journal of Applied Microbiology 2021, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez Guarguati, I.C. Diseño integrado multiescala de emulsiones directas: Relación entre propiedades reológicas y texturales. Trabajo de Maestría. , Universidad de Los Andes, Colombia, 2020.

- Laura, R.; Javier, O.; Alejandro, H.; Bladimir, G. La cadena de valor de los ingredientes naturales del biocomercio en las industrias farmacéutica, alimentaria y cosmética-fac; Editorial Tadeo Lozano, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gordillo López, R.C.; Romero Moya, E.A.; Romero, M.E. Optimización del capital de trabajo de una empresa de la industria cosmética por medio de un esquema de incentivos a la fuerza de ventas. Tesis Doctoral, ESPOL. FCSH., Ecuador, 2020.

- Torres, Y. Elaboración de una crema con actividad exfoliante con cáscara de cacao (theobroma cacao l.), proveniente de la provincia de manabí. Tesis Doctoral, Universidad Central del Ecuador, Ecuador, 2017.

- Lendínez Gris, M. Estudio de emulsiones altamente concentradas de tipo w/o: Relación entre tamaño de gota y propiedades. Tesis Doctorals, Universitad de Barcelona, 2015.

- Torres Taipe, K.V. Estudio de factibilidad para la elaboración de una crema hidratante a base de cáscaras de huevo en la ciudad de ambato, provincia de tungurahua. Tesis de Licenciatura., Universidad Técnica de Ambato, Ecuador, 2021.

- Salvador, A.; Chisvert, A. Analysis of cosmetic products; Elsevier: USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Milan, A.L.K.; Milão, D.; Souto, A.A.; Corte, T.W.F. Estudo da hidratação da pele por emulsões cosméticas para xerose e sua estabilidade por reologia. Revista Brasileira de Ciências Farmacêuticas 2018, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkataramani, D.; Tsulaia, A.; Amin, S. Fundamentals and applications of particle stabilized emulsions in cosmetic formulations. Adv Colloid Interface Sci 2020, 283, 102234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suaza Montalvo, A. Desarrollo de una estrategia de escalamiento para procesos de producción de emulsiones. Tesis de maestria., Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Colombia, 2020.

- Ruiz, Á.A.; Álvarez, H. Escalamiento de procesos químicos y bioquímicos basado en un modelo fenomenológico. Información tecnológica 2011, 22, 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eraso Lasso, S.L. Aproximación al proceso de escalado de emulsiones concentradas desde el diseño multiescala. Trabajo de Pregrado. , Universidad de Los Andes, Colombia, 2015.

- Schramm, L. Emulsions, foams, and suspensions; Wiley-VCH: USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- May-Masnou, A.; Porras, M.; Maestro, A.; González, C.; Gutiérrez, J.M. Scale invariants in the preparation of reverse high internal phase ratio emulsions. Chemical Engineering Science 2013, 101, 721–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burakova, M.A.; Abrosimova, O.N.; Ladutko, Y.M.; Smekhova, I.E. Transfer of cosmetic emulsion cream technology from laboratory to pilot phase. Drug development & registration 2022, 11, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türedi, E.; Acaralı, N. Evaluation of cosmetic creams containing black cumin (nigella sativa)-lemon balm (melissa officinalis l.)-aloe vera (aloe barbadensis miller) essences by modeling with box behnken method in design expert. Industrial Crops and Products 2022, 187, 115303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos Prada, D. Estudio de correlaciones experimentales para una emulsión aceite en agua (o/w) comercial. Tesis de grado., Universidad de los Andes, Colombia, 2018.

- Restrepo Jiménez, D. Aproximación al diseño multiescala en el proceso de escalado de emulsiones concentradas-parámetro de escalado. Tesis de grado. , Universidad de los Andes, Colombia, 2014.

- Suaza Montalvo, A. Desarrollo de una estrategia de escalamiento para procesos de producción de emulsiones. Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Colombia, 2020.

- Pérez-Martínez, A.; Cervantes-Mendieta, E.; Julián-Ricardo, M.C.; González-Suárez, E.; Gómez-Atanay, A.; Oquendo-Ferrer, H.; Galindo-Llanes, P.; Ramos-Sánchez, L. Procedimiento para enfrentar tareas de diseño de procesos de la industria azucarera y sus derivados. Revista Mexicana de Ingeniería Química 2012, 11, 333–349. [Google Scholar]

- Gallegos, J.d.C. Análisis del riesgo en la administración de proyectos de tecnología de información. Industrial Data 2006, 9, 104–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, M.; Ramos, M.; Silva, M.; Briceño, J.; Álvarez, M. Efecto de la temperatura previa a la extracción en el rendimiento y perfil de ácidos grasos del aceite de morete (mauritia flexuosa lf). LA GRANJA. Revista de Ciencias de la Vida 2022, 35, 98–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera Chasiquiza, M. Efecto de la temperatura de extracción en el rendimiento y perfil de ácidos grasos del aceite de morete (mauritia flexuosa lf). Tesis de Licenciatura., Universidad Técnica de Ambato, Ecuador, 2019.

- Paredes Amasifuen, J.A. Determinación del rendimiento y características fisicoquímicas del aceite obtenido mediante extracción mecánica en frío de tres ecotipos de aguaje (mauritia flexuosa l.) en la región de ucayali. Tesis de pregrado Universidad Nacional de Ucayali, Perú, 2021.

- Adrianzén, N.; Rojas, C.; Luján, G.L. Efecto de la temperatura y tiempo de tratamiento térmico de las almendras trituradas de sacha inchi (plukenetia volubilis l.) sobre el rendimiento y las características físico-químicas del aceite obtenido por prensado mecánico en frío. Agroindustrial Science 2011, 1, 46–55. [Google Scholar]

- Ocampo-Duran, Á.; Fernández-Lavado, A.; Castro-Lima, F. Aceite de la palma de seje oenocarpus bataua mart. Por su calidad nutricional puede contribuir a la conservación y uso sostenible de los bosques de galería en la orinoquia colombiana. ORINOQUIA 2013, 17, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacopini, M.I.; Guerrero, O.; Moya, M.; Bosch, V. Estudio comparativo del consumo de aceite de oliva virgen o seje sobre el perfil lipídico y la resistencia a la oxidación de las lipoproteínas de alta densidad (hdl) del plasma de rata. Archivos Latinoamericanos de Nutrición 2011, 61, 143. [Google Scholar]

- Peña, L.F.; Carrillo, M.P.; Giraldo, B.; Castro, S.Y.; Cardona, J.; Díaz, R.; Mosquera, L.E.; Hernández, M.S. Desarrollo tecnológico para el aprovechamiento sostenible de frutos de las palmas asaí (euterpe precatoria), seje (oenocarpus bataua), moriche (mauritia flexuosa); Instituto Amazónico de Investigaciones Científicas SINCHI: Colombia, 2018; p. 95. [Google Scholar]

- Chaves Yela, J.A.; Ortiz Tobar, D.P.; Bahos Ordoñez, E.M.; Ordoñez Forero, G.A.; Villota Padilla, D.C. Análisis del perfil de ácidos grasos y propiedades fisicoquímicas del aceite de palma de mil pesos (oenocarpus bataua). Perspectivas en Nutrición Humana 2020, 22, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bom, S.; Jorge, J.; Ribeiro, H.M.; Marto, J. A step forward on sustainability in the cosmetics industry: A review. Journal of Cleaner Production 2019, 225, 270–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosquera, T.; Noriega, P.; Tapia, W.; Pérez, S.H. Evaluación de la eficacia cosmética de cremas elaboradas con aceites extraídos de especies vegetales amazónicas: Mauritia flexuosa (morete), plukenetia volubilis (sacha inchi) y oenocarpus bataua (ungurahua). La Granja 2012, 16, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliaga Zumaeta, E.; Quispe Alarcon, A. Estudio de prefactibilidad para la implementación de una planta productora de mascarillas de tela hidratante a base de camu camu (myrciaria dubia). Tesis de Licenciatura. , Universidad de Lima, Perú, 2022.

- Romero, D.P.; Freire, A.; Aillon, F.E.; Radice, M. Design of an industrial process focused on the elaboration of cosmetics using amazonian vegetal oils: A biotrade opportunity. International Conference on Multidisciplinary Sciences. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, C. Optimización del proceso de fabricación de productos de tocador y limpieza en una industria cosmética de ventas por catálogo. Tesis para optar el Título Profesional de Ingeniero Industrial. , Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala, Guatemala:, 2011.

- Zurita Acosta, N.; López Pérez, A.M. Elaboración de emulsiones cosméticas con ingredientes de origen natural. Universidad de los Andes., Colombia, 2021.

- Chauhan, L.; Gupta, S. Creams: A review on classification, preparation methods, evaluation and its applications. Journal of Drug Delivery and Therapeutics 2020, 10, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celeiro, M.; Garcia-Jares, C.; Llompart, M.; Lores, M. Recent advances in sample preparation for cosmetics and personal care products analysis. Molecules 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quillupangui, L.; Arroyo, F. Mejoramiento de la eficiencia general del equipo mediante la simulación de eventos discretos. Estudio de caso en la industria cosmética. Espacios 2021, 42, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocca, R.; Acerbi, F.; Fumagalli, L.; Taisch, M. Sustainability paradigm in the cosmetics industry: State of the art. Cleaner Waste Systems 2022, 3, 100057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerda, V.R.; González, E.; Guardado, E.; Cerda, G.L.; Pérez, A. Producción de gel hidroalcohólico en tiempos de covid-19, oportunidad para diseñar el proceso que garantice la calidad. Centro Azúcar 2021, 48, 88–97. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, V.B.F.d.; Valério, V.E.d.M.; Miranda, R.d.C. Economic analysis of a cosmetic initiative addressing stochastic aspects and risk quantification. Acta Scientiarum. Technology 2023, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerda, V.R.; Guardado, E.; Cerda, G.L.; Vinocunga, R.; Pérez, A.; González, E. Procedure for the determination of operation and design parameters considering the quality of non-centrifugal cane sugar. Entre Ciencia e Ingeniería 2022, 16, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).