Submitted:

17 February 2025

Posted:

18 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Orchards/Location

2.2. Bait Cards

2.3. Experimental Method/Field Collection

2.4. Molecular Identification

2.4.1. Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) of ITS2 Region

2.4.2. Restriction Analysis

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

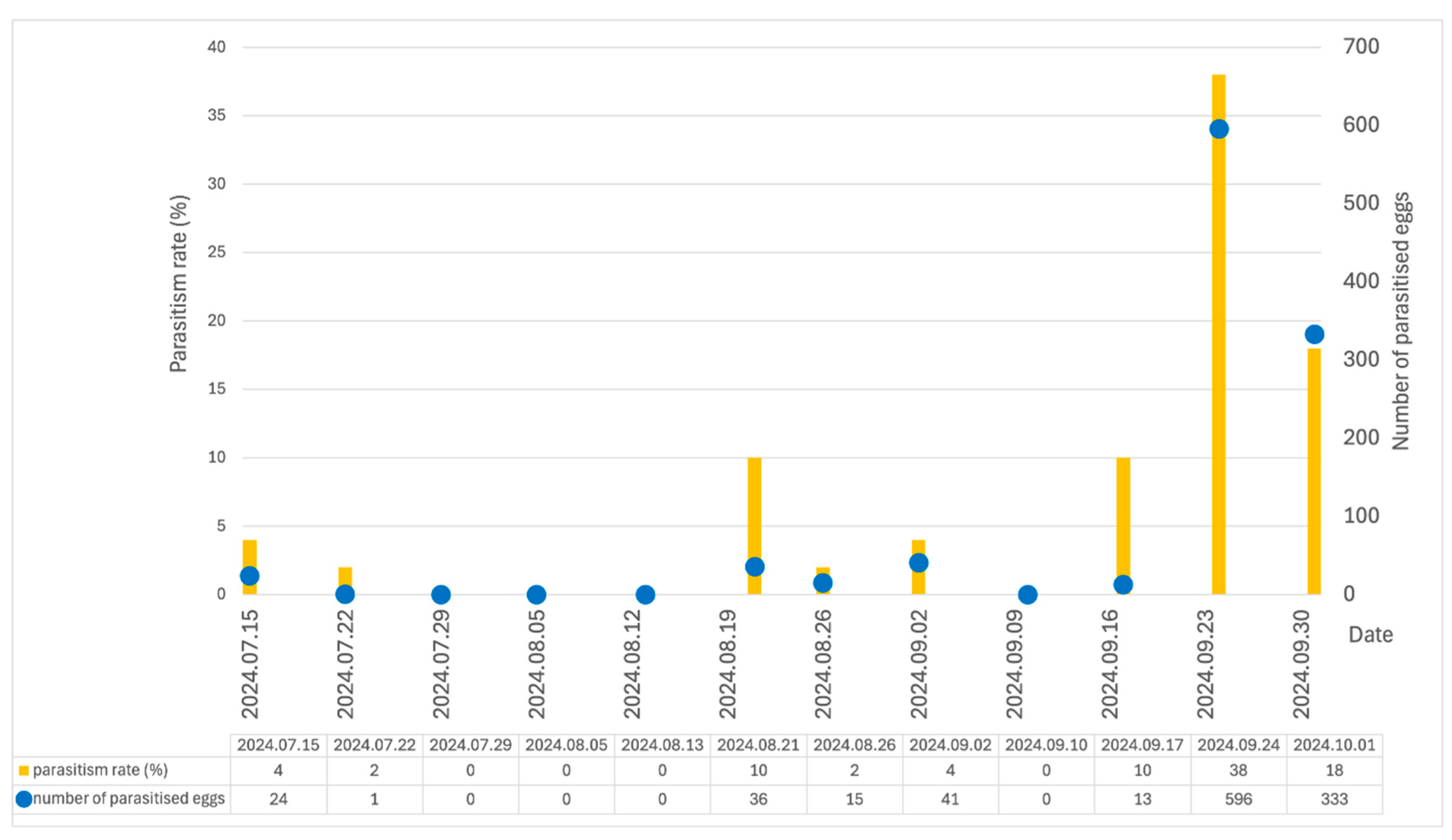

3.1. The Dependence of Discovery Rate and Parasitism Rate on the Time of Release

3.2. Relationship Between Parasitism Rate and the Number and Age of the Host Eggs

3.3. Relationship Between Hatching Rate and Time of Release and Age of the Host Eggs

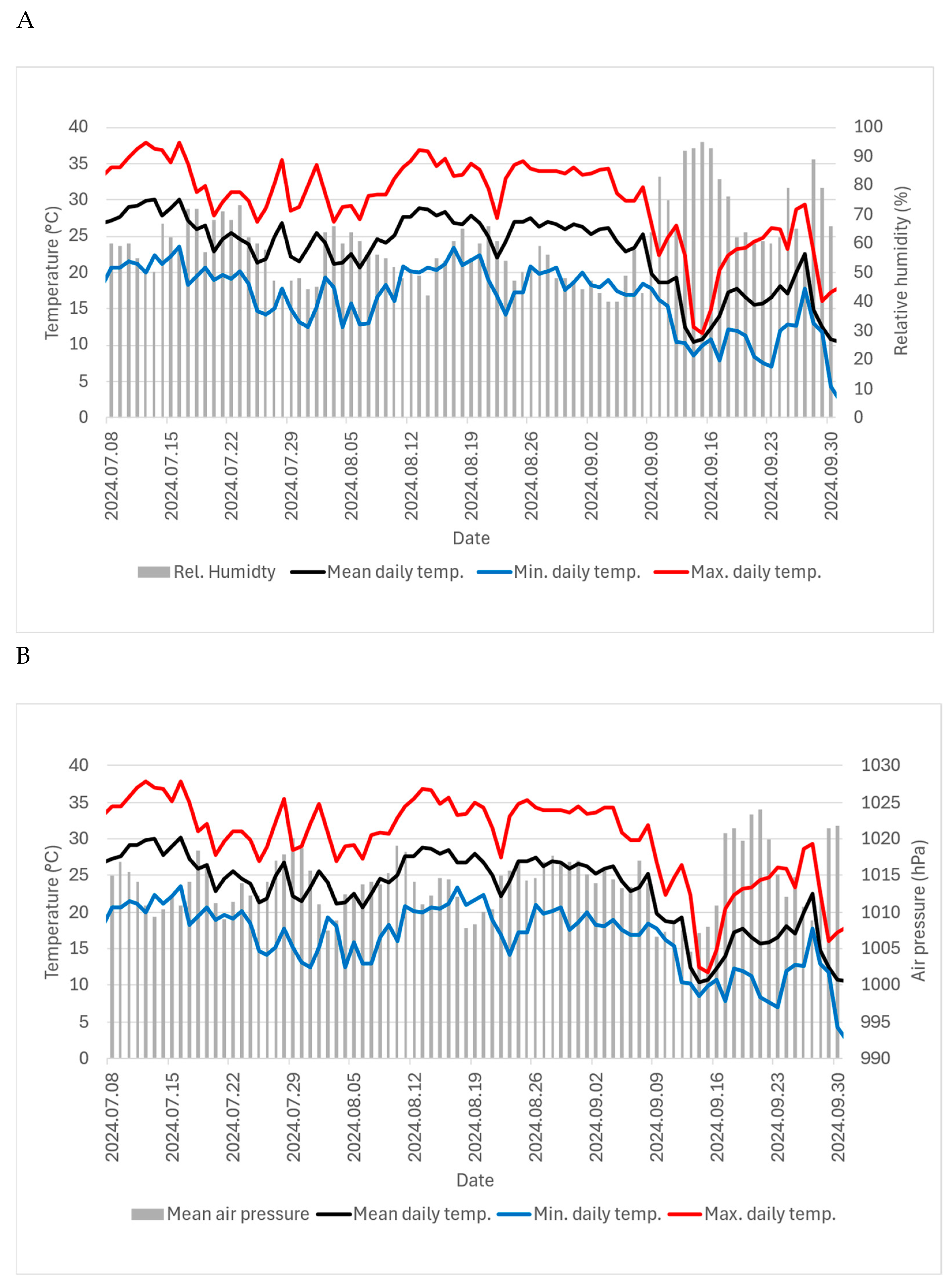

3.4. Relationship Between Parasitism, the Number of Parasitised Eggs and Meteorological Factors

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- A Knutson, A. The Trichogramma Manual. Bull. Agric. Ext. Serv. No 6071 1998.

- Pinto J.D.; Systematics of the North American Species of Trichogramma Westwood (Hymenoptera : Trichogrammatidae). Mem Entomol Soc Wash 1999, 22, 1–287.

- Yan, Z.; Yue, J.-J.; Zhang, Y.-Y. Biotic and Abiotic Factors That Affect Parasitism in Trichogramma Pintoi (Hymenoptera: Trichogrammatidae) as a Biocontrol Agent against Heortia Vitessoides (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae). Environ. Entomol. 2023, 52 (3), 301–308.

- Heimpel, G. E.; Boer, J. G. de. Sex Determination in the Hymenoptera. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2008, 53 (Volume 53, 2008), 209–230. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, W. J.; Nordlund, D. A.; Gueldner, R. C.; Teal, P. E. A.; Tumlinson, J. H. Kairomones and Their Use for Management of Entomophagous Insects. J. Chem. Ecol. 1982, 8 (10), 1323–1331. [CrossRef]

- Jervis, M. A.; Kidd, N. A. C.; Walton, M. A Review of Methods for Determining Dietary Range in Adult Parasitoids. Entomophaga 1992, 37 (4), 565–574. [CrossRef]

- Godfray, H. C. J. Parasitoids: Behavioral and Evolutionary Ecology; Princeton University Press, 1994.

- Giron, D.; Pincebourde, S.; Casas, J. Lifetime Gains of Host-Feeding in a Synovigenic Parasitic Wasp. Physiol. Entomol. 2004, 29 (5), 436–442. [CrossRef]

- Ellers, J.; Sevenster, J. G.; Driessen, G. Egg Load Evolution in Parasitoids. Am. Nat. 2000, 156 (6), 650–665. [CrossRef]

- [10] Farahani, H. K.; Ashouri, A.; Zibaee, A.; Abroon, P.; Alford, L. The Effect of Host Nutritional Quality on Multiple Components of Trichogramma Brassicae Fitness. Bull. Entomol. Res. 2016, 106 (5), 633–641. [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S. A. The Mass Rearing and Utilization of Trichogramma to Control Lepidopterous Pests: Achievements and Outlook. Pestic. Sci. 1993, 37 (4), 387–391. [CrossRef]

- Boivin, G. Overwintering Strategies of Egg Parasitoids. Biol. Control Egg Parasit. 1994, 219–244.

- Flanders, S. E. Mass Production of Egg Parasites Oí the Genus Trichogramma. 1930.Accessed: Dec. 03, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/full/10.5555/19310500283.

- Mills, N.; ‘Egg Parasitoids in Biological Control and Integrated Pest Management’, in Egg Parasitoids in Agroecosystems with Emphasis on Trichogramma, F. L. Consoli, J. R. P. Parra, and R. A. Zucchi, Eds., Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, 2010, pp. 389–411. [CrossRef]

- Smith, S. M. Biological Control with Trichogramma: Advances, Successes, and Potential of Their Use. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1996, 41 (Volume 41, 1996), 375–406. [CrossRef]

- Martel, V.; Johns, R. C.; Jochems-Tanguay, L.; Jean, F.; Maltais, A.; Trudeau, S.; St-Onge, M.; Cormier, D.; Smith, S. M.; Boisclair, J. The Use of UAS to Release the Egg Parasitoid Trichogramma Spp. (Hymenoptera: Trichogrammatidae) Against an Agricultural and a Forest Pest in Canada. J. Econ. Entomol. 2021, 114 (5), 1867–1881. [CrossRef]

- C Basso, C.; Chiaravalle, W.; Maignet, P.; Basso, C.; Chiaravalle, W.; Maignet, P. Effectiveness of Trichogramma Pretiosum in Controlling Lepidopterous Pests of Soybean Crops. Agrociencia Urug. 2020, 24 (SPE2). [CrossRef]

- Gavara, J.; Cabello, T.; Gámez, M.; Bastin, S.; Hernández-Suárez, E.; Piedra-Buena, A. Evaluation and Selection of New Trichogramma Spp. as Biological Control Agents of the Guatemalan Potato Moth (Tecia Solanivora) in Europe. Insects 2023, 14, 679, 2023. https://www.academia.edu/download/104845665/pdf.pdf (accessed 2024-12-03).

- Etilé, E.; Cabrera, P.; Boisclair, J.; Cormier, D.; Todorova, S.; Lucas, É. Field Evaluation of Trichogramma Ostriniae (Hymenoptera: Trichogrammatidae) and T. Brassicae as Biocontrol Agents of the European Corn Borer, Ostrinia Nubilalis (Lepidoptera: Crambidae), in Fresh Market Sweet Corn. Phytoprotection 2024, 104 (1), 35–46. [CrossRef]

- El, -Arnaouty S. A.; Galal, H. H.; Afifi, A. I.; Beyssat, V.; Pizzol, J.; Desneux, N.; Biondi, A.; Kortam, M. N.; Heikal, I. H. Assessment of Two Trichogramma Species for the Control of Tuta Absoluta in North African Tomato Greenhouses. Afr. Entomol. 2014, 22 (4), 801–809. [CrossRef]

- Sithanantham, S.; Abera, T. H.; Baumgärtner, J.; Hassan, S. A.; Löhr, B.; Monje, J. C.; Overholt, W. A.; Paul, A. V. N.; Wan, F. H.; Zebitz, C. P. W. EGG Parasitoids for Augmentative Biological Control of Lepidopteran Vegetable Pests in Africa: Research Status and Needs. Int. J. Trop. Insect Sci. 2001, 21 (3), 189–205. [CrossRef]

- Laminou, S. A.; Ba, M. N.; Karimoune, L.; Doumma, A.; Muniappan, R. Parasitism of Locally Recruited Egg Parasitoids of the Fall Armyworm in Africa. Insects 2020, 11 (7), 430. [CrossRef]

- Zang, L.-S.; Wang, S.; Zhang, F.; Desneux, N. Biological Control with Trichogramma in China: History, Present Status, and Perspectives. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2021, 66 (Volume 66, 2021), 463–484. [CrossRef]

- Navik, O.; Yele, Y.; Kedar, S. C.; Sushil, S. N. Biological Control of Fall Armyworm Spodoptera Frugiperda (JE Smith) Using Egg Parasitoids, Trichogramma Species (Hymenoptera: Trichogrammatidae): A Review. Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Control 2023, 33 (1), 118. [CrossRef]

- Vinson, S. B.; Greenberg, S. M.; Rao, A.; Volosciuk, L. F. Biological Control of Pests Using Trichogramma: Current Status and Perspectives; Xi bei nong lin ke ji da xue chu ban she, 2015.

- Schmidt, J. M. Host Recognition and Acceptance by Trichogramma. Biol. Control Egg Parasit. 1994, 165–200.

- Foerster, M. R.; Foerster, L. A. Effects of Temperature on the Immature Development and Emergence of Five Species of Trichogramma. BioControl 2009, 54 (3), 445–450. [CrossRef]

- Kalyebi, A.; Overholt, W. A.; Schulthess, F.; Mueke, J. M.; Sithanantham, S. The Effect of Temperature and Humidity on the Bionomics of Six African Egg Parasitoids (Hymenoptera: Trichogrammatidae). Bull. Entomol. Res. 2006, 96 (3), 305–314. [CrossRef]

- Atashi, N.; Shishehbor, P.; Seraj, A. A.; Rasekh, A.; Hemmati, S. A.; Riddick, E. W. Effects of Helicoverpa Armigera Egg Age on Development, Reproduction, and Life Table Parameters of Trichogramma Euproctidis. Insects 2021, 12 (7), 569. [CrossRef]

- Tayat, E.; Özder, N. Preference Study of Trichogramma Pintoi (Voegele) (Hymenoptera:Trichogrammatidae) on Host Eggs of Different Ages and Species. Mustafa Kemal Üniversitesi Tarım Bilim. Derg. 2023, 28 (2), 355–362. [CrossRef]

- HASSAN, S. A. Strategies to Select Trichogramma Species for Use in Biological Control. Biol. Control Egg Parasit. 1994., Accessed: Dec. 05, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1571980075268517376.

- van Lenteren, J. C.; Babendreier, D.; Bigler, F.; Burgio, G.; Hokkanen, H. M. T.; Kuske, S.; Loomans, A. J. M.; Menzler-Hokkanen, I.; van Rijn, P. C. J.; Thomas, M. B.; Tommasini, M. G.; Zeng, Q.-Q. Environmental Risk Assessment of Exotic Natural Enemies Used in Inundative Biological Control. BioControl 2003, 48 (1), 3–38. [CrossRef]

- Sherwani, A.; Mukhtar, M.; Wani, A. A. Insect Pests of Apple and Their Management. Insect Pest Manag. Fruit Crops 2016, 295–306.

- Sigsgaard, L.; Herz, A.; Korsgaard, M.; Wührer, B. Mass Release of Trichogramma Evanescens and T. Cacoeciae Can Reduce Damage by the Apple Codling Moth Cydia Pomonella in Organic Orchards under Pheromone Disruption. Insects 2017, 8 (2), 41.

- Mansfield, S.; Mills, N. J. Host Egg Characteristics, Physiological Host Range, and Parasitism Following Inundative Releases of Trichogramma Platneri (Hymenoptera: Trichogrammatidae) in Walnut Orchards. Environ. Entomol. 2002, 31 (4), 723–731.

- Samara, R. Y.; Carlos Monje, J.; Zebitz, C. P. W. Comparison of Different European Strains of Trichogramma Aurosum (Hymenoptera: Trichogrammatidae) Using Fertility Life Tables. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2008, 18 (1), 75–86. [CrossRef]

- Yu, D. S. K.; Hagley, E. A. C.; Laing, J. E. Biology of Trichogramma Minutum Riley Collected from Apples in Southern Ontario. Environ. Entomol. 1984, 13 (5), 1324–1329. [CrossRef]

- Dolphin, R. E.; Cleveland, M. L.; Mouzin, T. E.; Morrison, R. K. Releases of Trichogramma Minutum1 and T. Cacoeciae1 in an Apple Orchard and the Effects on Populations of Codling Moths 2. Environ. Entomol. 1972, 1 (4), 481–484. [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S. A.; Kohler, E.; Rost, W. M. Mass Production and Utilization ofTrichogramma: 10. Control of the Codling mothCydia Pomonella and the Summer Fruit Tortrix mothAdoxophyes Orana [Lep.: Tortricidae]. Entomophaga 1988, 33 (4), 413–420. [CrossRef]

- Cherif, A.; Grissa-Lebdi, K. Field Releases of Trichogramma Cacoeciae (Marchal, 1927) (Hymenoptera: Trichogrammatidae) against the Codling Moth, Cydia Pomonella (Linnaeus, 1758) (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae). J. OASIS Agric. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 6 (03), 35–40. [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, L.; Herz, A. Suitability of European Trichogramma Species as Biocontrol Agents against the Tomato Leaf Miner Tuta Absoluta. Insects 2020, 11 (6), 357. [CrossRef]

- Abbas, S. S.; Shahzad, M. F.; Iqbal, J.; Ullah, A.; Batool, A.; Nadeem, M.; Begum, H. A.; Rehman, H.-; Muhammad, K. Trichogramma Chilonis as Parasitoid: An Eco-Friendly Approach Against Tomato Fruit Borer, Helicoverpa Armigera. J. Agric. Sci. 2020, 12 (2), 167. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Tang, R.; Fang, H.; Liu, X.; Michaud, J. P.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Z. Laboratory and Field Studies Supporting Augmentation Biological Control of Oriental Fruit Moth, Grapholita Molesta (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae), Using Trichogramma Dendrolimi (Hymenoptera: Trichogrammatidae). Pest Manag. Sci. 2021, 77 (6), 2795–2803. [CrossRef]

- Reichart, G. Adatok a Magyarországi Gyümölcsösök Sodrómolyainak Ismeretéhez. Data Referring Knowl. Fruit Tree Leaf Roll. Hung. Orchards Ujabb Véd. Eljárások Kert. KártevHok És Bet. Ellen Bp. 1953, 21.

- Nagy, B. The Possible Role of Entomophagous Insects in the Genetic Control of the Codling Moth, with Special Reference toTrichogramma. Entomophaga 1973, 18 (2), 185–191. [CrossRef]

- [46] Bognár, S. Adatok Az Almamoly Magyarországi Természetes Ellenségeirôl És Szerepükrôl. (Data Concerning the Natural Enemies of the Apple Moth in Hungary and Their Role.). Kert. És Szőlészeti Főisk. Évkönyve 1962, 26, 31–43.

- Bokor, M.; Megújulóban van az almatermesztés Magyarországon. Agrofórum Online. https://agroforum.hu/agrarhirek/zoldseg-gyumolcs/megujuloban-van-az-almatermesztes-magyarorszagon/ (accessed 2024-12-08).

- Hedvig M. Mit tudnak a Trichogramma petefürkészek?. Biokontroll Hungária Nonprofit Kft. https://www.biokontroll.hu/mit-tudnak-a-trichogramma-petefuerkeszek/ (accessed 2024-12-08).

- Stouthamer, R.; Hu, J.; Van Kan, F. J. P. M.; Platner, G. R.; Pinto, J. D. [No Title Found]. BioControl 1999, 43 (4), 421–440. [CrossRef]

- Hegazi, E. M.; Herz, A.; Hassan, S.; Agamy, E.; Khafagi, W.; Shweil, S.; Zaitun, A.; Mostafa, S.; Hafez, M.; El-Shazly, A.; El-Said, S.; Abo-Abdala, L.; Khamis, N.; El-Kemny, S. Naturally Occurring Trichogramma Species in Olive Farms in Egypt. Insect Sci. 2005, 12 (3), 185–192. [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, C. I.; Huigens, M. E.; Verbaarschot, P.; Duarte, S.; Mexia, A.; Tavares, J. Natural Occurrence of Wolbachia-Infected and Uninfected Trichogramma Species in Tomato Fields in Portugal. Biol. Control 2006, 37 (3), 375–381. [CrossRef]

- Souza, A. R. de; Giustolin, T. A.; Querino, R. B.; Alvarenga, C. D. Natural Parasitism of Lepidopteran Eggs by Trichogramma Species (Hymenoptera: Trichogrammatidae) in Agricultural Crops in Minas Gerais, Brazil. Fla. Entomol. 2016, 99 (2), 221–225. [CrossRef]

- Ram, P. Studies on Strains of Trichogramma Evanescens Westwood from Different Regions of Eurasia. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 1995, 5 (3), 329–338. [CrossRef]

- Bírová H. Trichogramma Evanescens Westw. Als Beschrankungsfaktor Des Massenhaften Auftretens Des Maisziinslers (Pyrausta Nubilalis Hbn.).; 1956; Vol. The ontogeny of Insects, Acta symposii de evolutione insectorum Praha, 357-359.

- Bírová H. European Corn Borer-Pyrausta (i.e, Ostrinia) Nubilalis (Hbn.) (Lep. Pyralidae) in Czechoslovakia. 1962, a. Pol. Pismo Entomol. Bull., (Seria B,), 25–26, 25-29.

- írová H. VLskyt Vijacky Kukuricnej (Ostrinia Nubilalis Hbn.) v 19561985 v Oblasti Intenyivneho Pestovania Kukurice Na Slovensku. (Occurrence of the European Corn Borer (Ostrinia Nubilalis Hbn.) in 19561985 in a Region of Intensive Maize Production in Slovakia). XI. Czechoslovak Plant Protection Conference, Proceedings, 1988.

- Cagán, L.; Tancik, J.; Hassan, S. Natural Parasitism of the European Corn Borer Eggs Ostrinia Nubilalis Hbn. (Lep., Pyralidae) by Trichogramma in Slovakia—Need for Field Releases of the Natural Enemy. J. Appl. Entomol. 1998, 122 (1–5), 315–318. [CrossRef]

- Hochmut, R.; Martinek, V. Beitrag Zur Kenntnis Der Mitteleuropäischen Arten Und Rassen Der Gattung Trichogramma Westw. ( Hymenoptera, Trichogrammidae ). Z. Für Angew. Entomol. 1963, 52 (1–4), 255–274. [CrossRef]

- [59] Barnay, O.; Hommay, G.; Gertz, C.; Kienlen, J. C.; Schubert, G.; Marro, J. P.; Pizzol, J.; Chavigny, P. Survey of Natural Populations of Trichogramma (Hym., Trichogrammatidae) in the Vineyards of Alsace (France). J. Appl. Entomol. 2001, 125 (8), 469–477. [CrossRef]

- Castaneda-Samayoa, O.; Holst, H.; Ohnesorge, B. Evaluation of Some Trichogramma Species with Respect to Biological Control of Eupoecilia Ambiguella Hb. and Lobesia Botrana Schiff. (Lep., Tortricidae) / Evaluierung Einiger Trichogramma-Arten Hinsichtlich Ihrer Verwendbarkeit Zur Biologischen Bekämpfung von Eupoecilia Ambiguella Hb. Und Lobesia Botrana Schiff. (Lep., Tortricidae). Z. Für Pflanzenkrankh. Pflanzenschutz J. Plant Dis. Prot. 1993, 100 (6), 599–610.

- Dudich, E. Insect Parasites of the Corn Borer (Pyrausta Nubilalis Hb.) in Hungary. Int. Corn Borer Investig. Sci. Rep. 1928, 1, 184–190.

- B Nagy, B. On Some Aspects of the Investigations of the Maize Ecosystem in Hungary, with Special Respect to the European Corn Borer. Vedecke Pr. Vysk. Ustavu Kukurice V Trnave Czechoslov. 1985, No. 14.

- Sengonca, C.; Leisse, N. Vorkommen Und Bedeutung von Trichogramma Semblidis Auriv. (Hymenoptera, Trichogrammatidae) Als Eiparasit Beider Traubenwicklerarten Im Ahrtal. J. Appl. Entomol. 1987, 103 (1–5), 527–531. [CrossRef]

- Şengonca, Ç.; Leisse, N. Enhancement of the Egg Parasite Trichogramma Semblidis (Auriv.) (Hym., Trichogrammatidae) for Control of Both Grape Vine Moth Species in the Ahr Valley1,2. J. Appl. Entomol. 1989, 107 (1–5), 41–45. [CrossRef]

- Kot, J. Experiments in the Biology and Ecology of Species of the Genus Trichogramma Westw. and Their Use in Plant Protection. 1964.

- Zouba, A.; Zougari, S.; Mamay, M.; Kadri, N.; Ben Hmida, F.; Lebdi-Grissa, K. The Effect of Different Oviposition and Preadult Development Temperatures on the Biological Characteristics of Four Trichogramma Spp. Parasitoids (Hymenoptera: Trichogrammatidae) Species. Phytoparasitica 2024, 52 (1), 19. [CrossRef]

- Schöller, M.; Hassan, S. A. Comparative Biology and Life Tables of Trichogramma Evanescens and T. Cacoeciae with Ephestia Elutella as Host at Four Constant Temperatures. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2001, 98 (1), 35–40. [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, J. K.; Al-Jassany, R. F.; Ali, A.-S. A. Influence of Temperature on Some Biological Characteristics of Trichogramma Evanescens (Westwood)(Hymenoptera: Trichogrammatidae) on the Egg of Lesser Date Moth Batrachedra Amydraula Meyrick. 2015.

- Metwally, M. M.; El-Kordy, M. W.; Mohamed, H. A.; El-Sebai, A.; Atta, A. A. Effect of temperature, photoperiod, biological and chemical factors of three host species on the performance of the eggs parasitoid Trichogramma Evanescens WEST. J. Plant Prot. Pathol. 2013, 4 (9), 781–793. [CrossRef]

- Fournier, F.; Pelletier, D.; Vigneault, C.; Goyette, B.; Boivin, G. Effect of Barometric Pressure on Flight Initiation by Trichogramma Pretiosum and Trichogramma Evanescens (Hymenoptera: Trichogrammatidae). Environ. Entomol. 2005, 34 (6), 1534–1540. [CrossRef]

| Group Category Values | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group Category | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Discovery rate* (%) | 0 | 1–5 | 6–15 | >16 | ||

| Parasitism rate† | 0 | 0.001–0.1 | 0.101–0.4 | - | - | |

| Hatching rate (%)‡ | 0 | 0–95 | 96–99 | 100 | - | |

| Date of the placement | - | 08.07.2024–13.08.2024 | 14.08.2024–17.09.2024 | 18.09.2024–01.10.2024 | - | - |

| Age of host eggs (days) | - | 1–7 | 8–14 | >14 | - | - |

| Number of host eggs (pcs) | - | 1–100 | 101–200 | 201–300 | 301–400 | >400 |

| Average mean temperature* (°C) |

Average minimum temperature* (°C) | Average maximum temperature* (°C) |

Average relative humidity* (%) |

Average wind speed* (m/sec) | Average air pressure* (hPa) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parasitism rate (%) † |

R | -0.64 | -0.60 | -0.75 | 0.46 | -0.19 | 0.49 |

| t (df=10) | 2.64 | 2.38 | 3.59 | 1.62 | 0.60 | 1.78 | |

| p | 0.025 | 0.039 | 0.005 | 0.136 | 0.559 | 0.106 | |

| Number of parasitised eggs | R | -0.61 | -0.65 | -0.70 | 0.33 | -0.16 | 0.67 |

| t (df=10) | 2.46 | 2.74 | 3.06 | 1.09 | 0.50 | 2.83 | |

| p | 0.033 | 0.021 | 0.012 | 0.301 | 0.625 | 0.018 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).