Submitted:

17 February 2025

Posted:

18 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

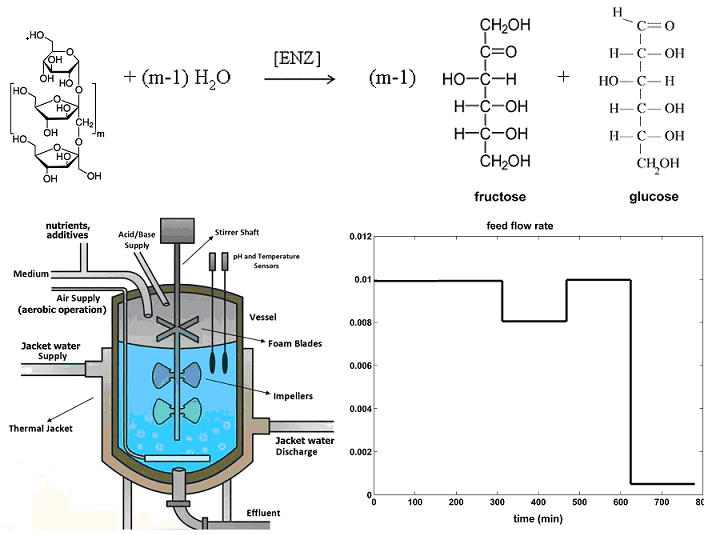

2. The Experimental Enzymatic Reactor

3. Process Kinetics and Reactor Dynamic Model

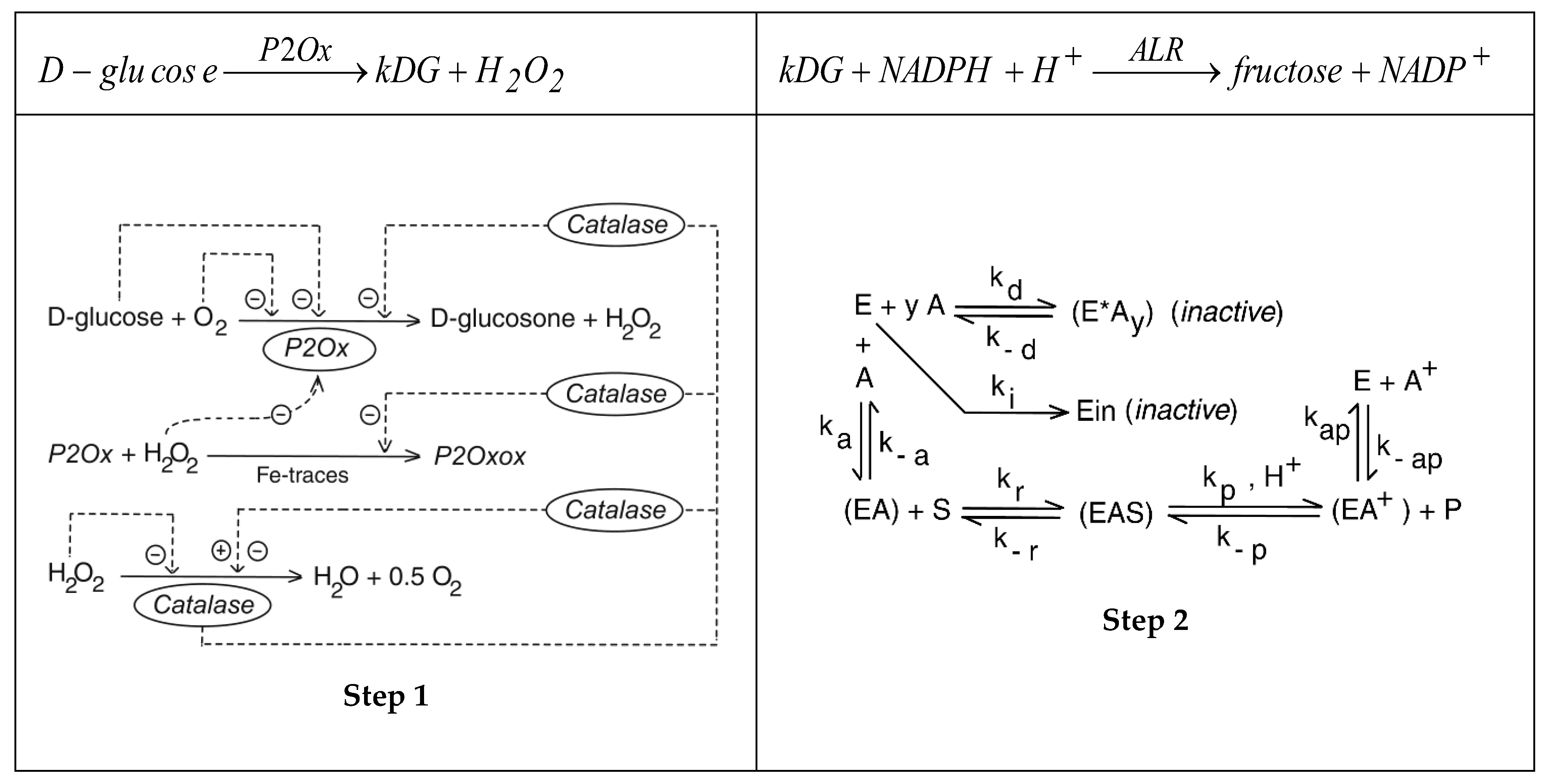

| Reaction pathway (Figure 2): | |

|

; ; ; ; The above consecutive scheme is approximated by the overall reaction: | |

| Rate expressions: [a] | Parameters: |

|

; = ; = ; Or, equivalently, one can write: ; = ; = |

“m= 29; = 18 g/mol == 180 g/mol =, g/U·min [b] =, g/L ” |

| Enzyme deactivation model: | |

| - adopted first-order model: , ⇒ Or, equivalently, one can write: |

=, 1/h (experimental, free enzyme) |

| - other data from literature: “free-enzyme (Santos et al., 2007) immobilized-enzyme (Santos et al., 2007) |

, 1/min , 1/min |

| - other rate expressions (pseudo second-order, not tested here): , ⇒ free-enzyme (Catana et al., 2007) immobilized-enzyme (Catana et al., 2007)” |

, 1/h , 1/h |

| Species | Remarks |

|

Species mass balances: ; “j” = species index (S, F, W, G, E), With the initial conditions of: ; where “j” = (S, E, W) are to be optimized; = 0 , for j = (F, G). |

The species reaction rate () expressions, the rate constants, and the stoichiometry (νij) are given in Table 3. Enzyme (E) deactivation is included in this dynamic balance. The optimal BR initial load (Table 5) is off-line determined by in-silico solving the associated NLP optimization problem (this paper). C = species concentration vector ; k = rate constants vector |

| Species | Remarks | |

|

Species mass balances: ; ; for species i = S, F, G, E , for i= S,E ; = control variables, where i = S,E; j = 1,.., time stepwise unknown values to be determined from the FBR optimization; For species W the mass balance is [b]: [W]o = 988 g/L; = 0 , for j = (F, G). |

For the optimal FBR with adopted Ndiv = 5, the feeding policy are (Footnote [a]): |

|

|

Liquid volume in the reactor (footnote [c]): = control variable; j = 1,..,time stepwise unknown values to be determined from the FBR optimization. The unknown = (t = 0) = is determined together with the all values. |

For the optimal FBR with adopted Ndiv =10, the feeding policy is (Footnote [a]): |

|

| ) to ensure the FBR optimal operation. | ||

4. Optimization Problem for the BR and FBR Reactors

4.1. Control Variables Selection

4.2. NLP Optimization with a Single Objective Function (Ω)

|

Given [F]o = 0, [G]o = 0, find control variables [S]o [E]o, [W]o, such that: Max Ω(C, Co, k) , where: Ω = [F(t)] |

(1-BR) |

|

Given [F]o = 0, [G]o = 0, Find the control variables: ; ; , For j = 1,…, Ndiv , with the adopted Ndiv = 5 time-arcs, and the FBR initial condition of Table 4-FBR, so as to obtain: Max Ω(C, Co, k) , where: Ω = [F(t)] |

(1-FBR) |

| Reactor operation | Raw-material consumption [b] |

Max F (fructose), (g)[b] |

Final VL (L) | |||||||

| Type | Ndiv | Operating parameters |

S (inulin), (g) (Eq.4) |

E (enzyme) (U) (Eq.4) |

[a] | |||||

|

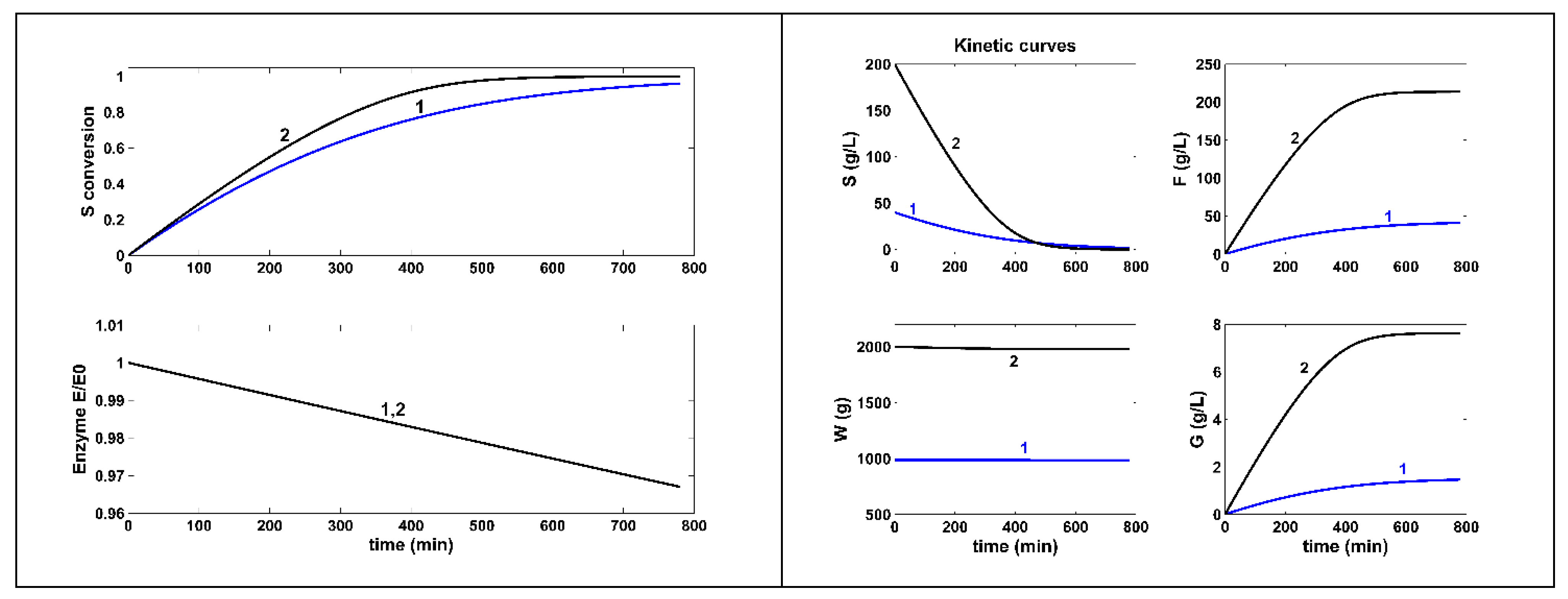

BR not-optimal [Ricca et al. 2009b] |

1 |

Nominal load [c,f] (Figure 4) |

40 |

9.7 (poor) |

41.05 | 1 | ||||

| [S]o | 40 | |||||||||

| [E]o | 9.7 | |||||||||

| Wo | 988.4 | |||||||||

|

BR Optimal load NLP (this paper) [h] |

1 |

Initial load [f,b,h] (Figure 3) |

200 |

302 (fairy good) |

213.7 | 2 [g] | ||||

| [S]o | 200 | |||||||||

| [E]o | 301.87 | |||||||||

| Wo | 2000 | |||||||||

|

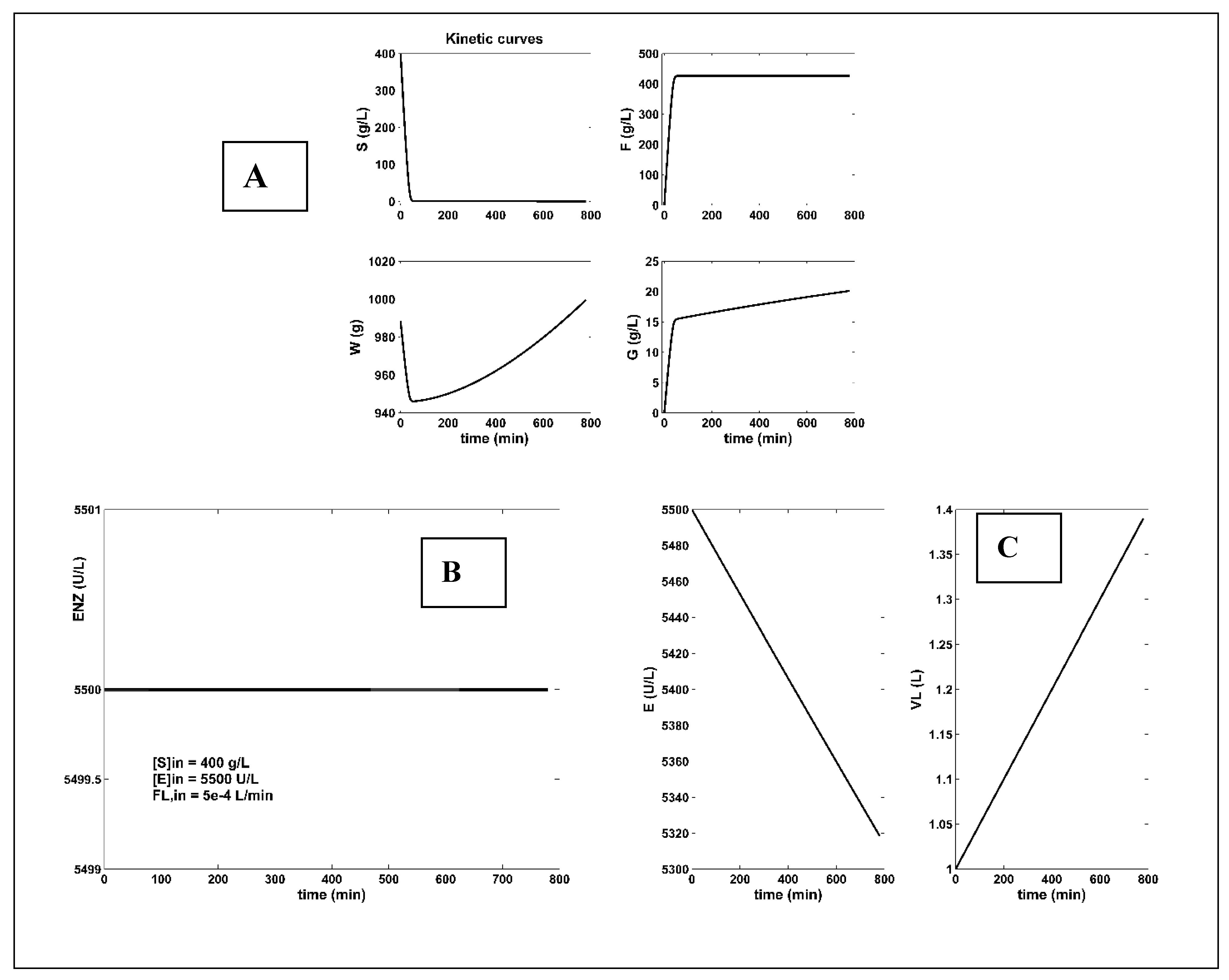

FBR Constant, but NLP optimal feeding, (this paper) [d] |

1 |

optimal feeding [f,j] (Figure 4) |

156 |

2145.9 (almost best) |

426.9 | 1.4 | ||||

| [S]in | 400 | |||||||||

| [E]in | 5500 | |||||||||

| FL,in | 5e-4 | |||||||||

|

FBR Constant, but Pareto optimal feeding, (this paper) [d] |

1 | optimal feeding [f,j] | 180.4 |

357.9 (best) |

422.9 | 1.4 | ||||

| [S]in | 399.88 | |||||||||

| [E]in | 793.19 | |||||||||

| FL,in | 5.78e-4 | |||||||||

|

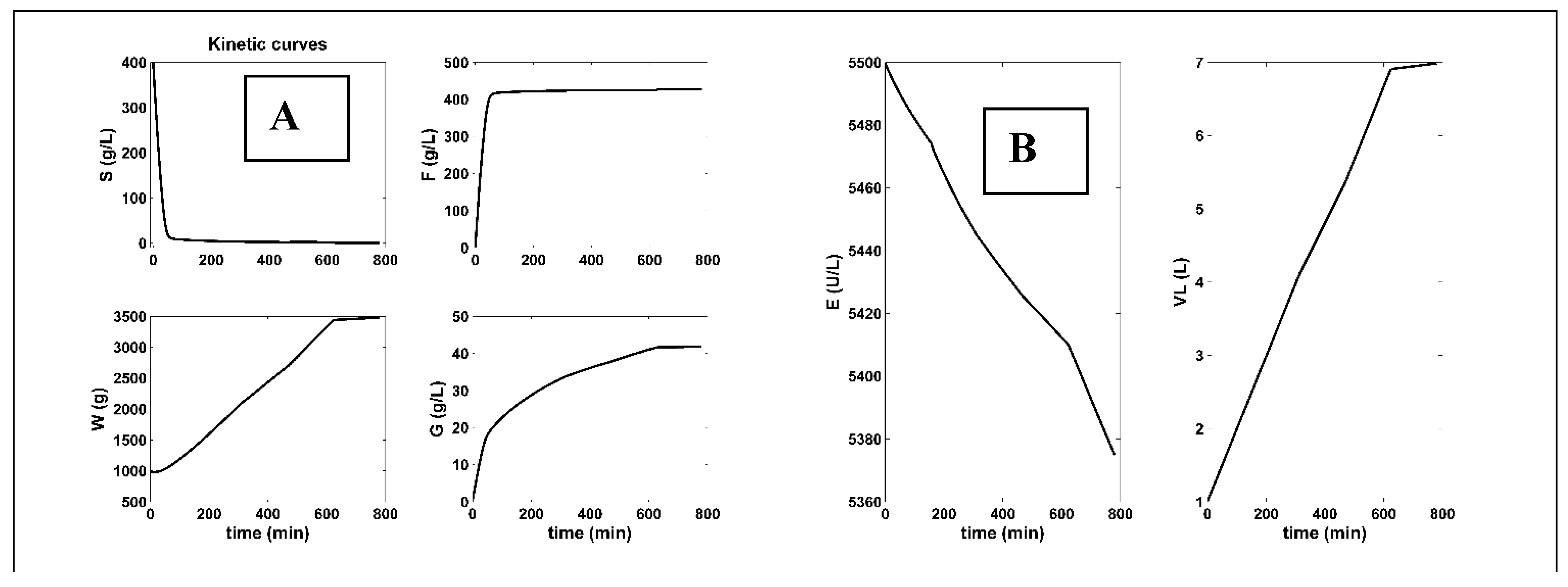

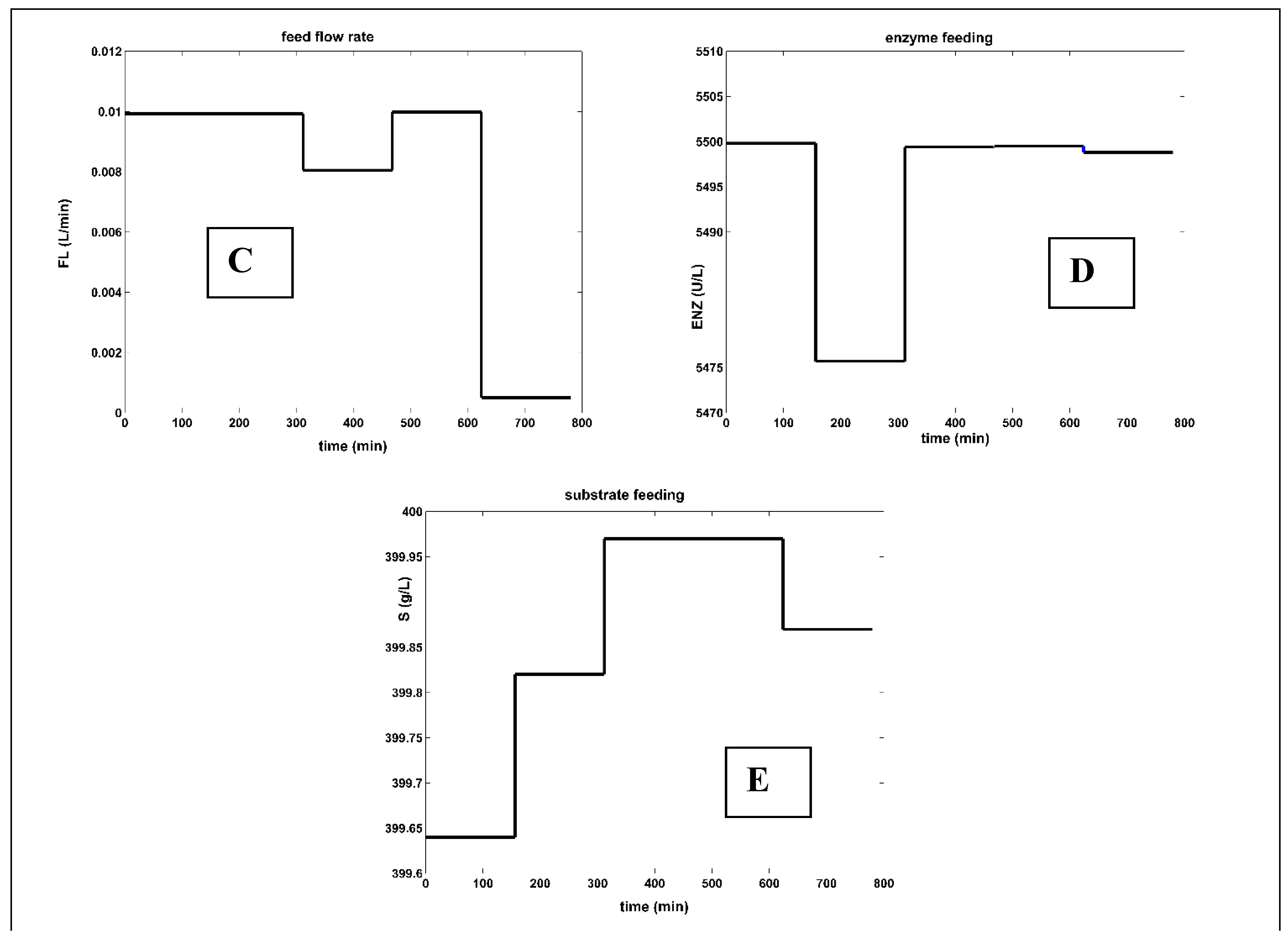

FBR Variable optimal NLP feeding , (this paper) [e] |

5 |

optimal feeding [f,j] (Figure 5) |

2,393.7 |

3.29E+4 (high consumptions, and dilution) |

428 | 6.98 | ||||

|

[S]in [40-400] |

variable Figure 6D |

|||||||||

|

[E]in [97-5500] |

variable Figure 6D |

|||||||||

|

FL,in [5e-4 – 0.01] |

variable Figure 6C |

|||||||||

|

Footnotes: [a] Initial liquid volume VL,o = 1 L. [b] The displayed digits come from the numerical simulations. [c] The checked BR set-point of Ricca et al. [69]. [d] The FBR operation with a constant over time feeding for all the control variables, that is (Table 4-FBR): ; ; the only 3 variables to be optimized being the initial inlet values of , , , under the constraints Eq.(2i-iv). See the resulted FBR optimal operating policy in Figure 4. [e]. The FBR optimal time step-wise variable feeding policy is obtained by using the control variable limits of the footnote [j]. In this FBR operating case, the control variables, that is , , ; j = 1,…(Ndiv -1) of Table 4-FBR, follows an uneven policy to be optimized (that is 15 unknowns for Ndiv = 5). The optimal control variables policy is given in Figure 5. [f] The units are: [S] g/L ; [E] U/L ; [W] g; FL L/min. [g] The volume corresponds to the water (W) mass required by the reaction. [h] Search intervals of the control variables are the followings: [S]in = [40-200] g/L ; [E]in = [97-5500] U/L. [j] Search intervals of control variables are: [S]in = [40-400] g/L ; [E]in = [97-5500] U/L; FL,in = [5e-4 – 0.01] L/min. [67]. | ||||||||||

4.3. Optimization Problem Constraints

|

Nonlinear process and reactor model: Table 4-BR, for the BR case. Table 4-FBR, for the FBR case. |

(2i) |

|

Physical significance constraints: “, in Table 4-BR, and Table 4-FBR, for all the species of index ‘j’, and for all t Є [0-tf]” |

(2ii) |

|

Searching ranges for the control variables are given in (Table 2), that is: [S]o; [S]in ∈ [40-400] g/L [E]o; [E]in ∈ [97-5500] (U/L) [W]o ∈ [988- 4000](g) FL ∈ [5e-4 – 0.01] (L/min) |

(2iii) |

| ≤ 10 L (reactor capacity) | (2iv) |

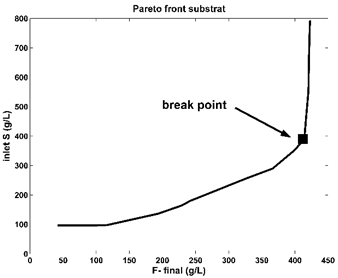

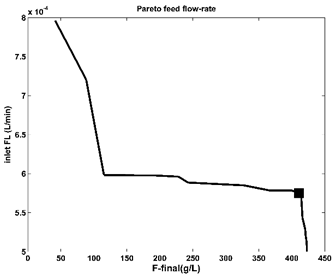

4.4. Pareto Optimal Front Optimization with Opposite Objective Functions

| Maximum F production vs.- Minimum substrate (S) consumption. Minimum constant feed flow rate, for various maximum F produced. Maximum F production vs.- Minimum enzyme (E) consumption. |

(3) |

|

|

|

Figure 6. The Pareto-optimal front for the FBR (of Table 1) with a constant feeding in terms of two opposite objectives, that is maximum F production vs.- minimum substrate (S) consumption. This problem Eq. (3) solution was obtained by imposing the control variable limits given in Table 5. The set-point was chosen as being the “break point” of the Pareto-optimal front, according to the suggestions of Dan and Maria [42] |

Figure 7. The Pareto-optimal operating policy of the FBR (of Table 1) in terms of required minimum constant feed flow rate, for various maximum F produced. The marked point is the chosen set-point corresponding to those of the Pareto-optimal curve of Figure 6. |

4.5. The Used Solvers

5. Optimization Results and Their Discussion

6. Conclusions

| - | species j concentration | |

| ,, | - | kinetic model constants |

| k | - | rate constants vector |

| - | molecular weight | |

| - | mass | |

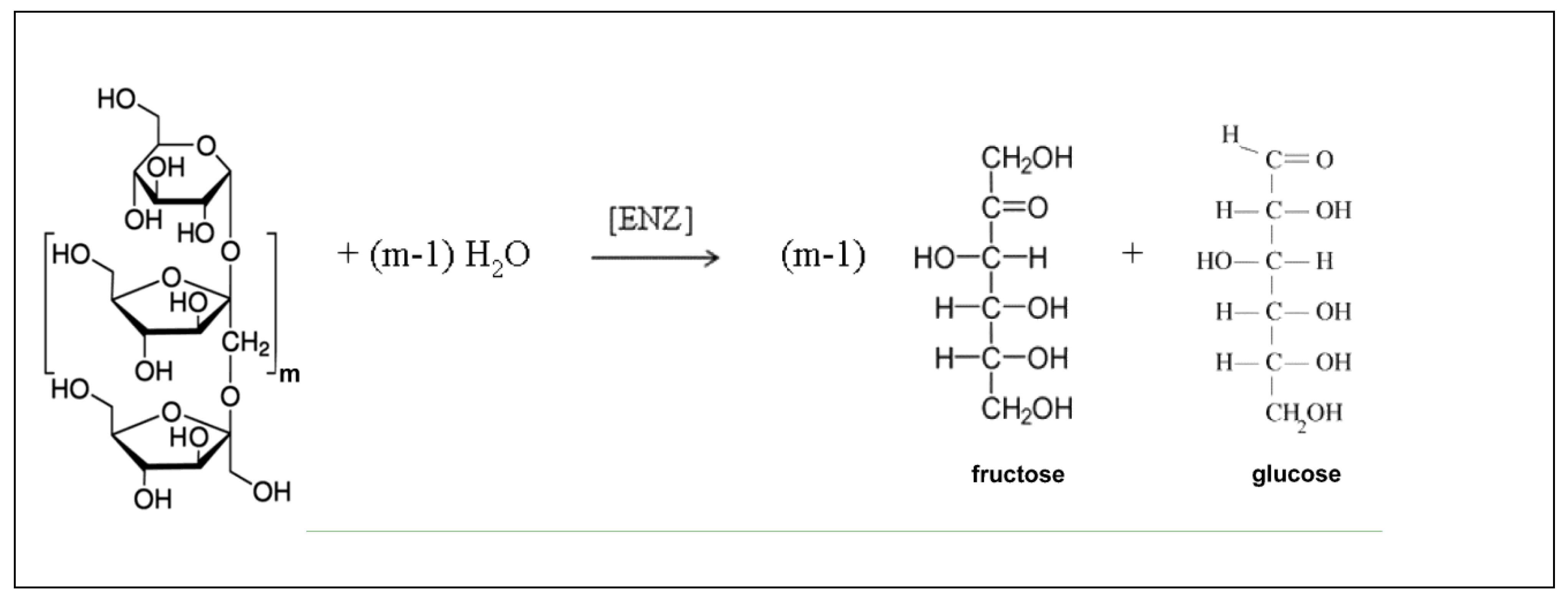

| - | fructose degree of polymerization in the inulin | |

| - | Number of time “arcs”, that is the number of equal divisions of the batch time for a FBR with variable feeding case | |

| - | species j reaction rate | |

| - | temperature | |

| - | time | |

| - | time interval | |

| - | batch time | |

| VL, VL | - | liquid volume |

| Greeks | ||

| ,, , , | - | Kinetic model constants |

| - | finite difference | |

| νij | - | The stoichiometric coefficient of the species “j” in the reaction “i” |

| Ω | - | optimization objective function |

| - | density | |

| Index | ||

| In, inlet | - | inlet |

| 0,o | - | initial |

| S ,F, W, E, G | - | Substrate, fructose, water, enzyme, glucose, respectivelly |

| kDG | - | Keto D-Glucose (D-glucosone) |

| Max | - | maximum |

| NLP | - | nonlinear programming |

| PO2x | - | Pyranose 2-oxidase |

| S | - | Substrate (inulin) |

| SBR | - | semi-batch reactor |

| W | - | water |

References

- Moulijn, J.A.; Makkee, M.; van Diepen, A. , Chemical process technology, Wiley, New York, 2001.

- Wang, P. Multi-scale Features in Recent Development of Enzymic Biocatalyst Systems. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2008, 152, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasić-Rački, D.; Findrik, Z.; Presečki, A.V. Modelling as a tool of enzyme reaction engineering for enzyme reactor development. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 91, 845–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maria, G. , A review of algorithms and trends in kinetic model identification for chemical and biochemical systems, Chem. Biochem. Eng. Q., 2004, 18, 195–222. [Google Scholar]

- Gernaey, K.V.; Lantz, A.E.; Tufvesson, P.; Woodley, J.M.; Sin, G. Application of mechanistic models to fermentation and biocatalysis for next-generation processes. Trends Biotechnol. 2010, 28, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonvin, D.; Srinivasan, B.; Hunkeler, D. , Control and optimization of batch processes, IEEE Control systems magazine, 2006, 34-45.

- Srinivasan, B.; Primus, C.; Bonvin, D.; Ricker, N. Run-to-run optimization via control of generalized constraints. Control. Eng. Pr. 2001, 9, 911–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewasme, L.; Amribt, Z.; Santos, L.; Hantson, A.-L.; Bogaerts, P.; Wouwer, A.V. Hybridoma cell culture optimization using nonlinear model predictive control. IFAC Proc. Vol. 2013, 46, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewasme, L.; Côte, F.; Filee, P.; Hantson, A.-L.; Wouwer, A.V. Macroscopic Dynamic Modeling of Sequential Batch Cultures of Hybridoma Cells: An Experimental Validation. Bioengineering 2017, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, R.; Rocha, I.; Pinto, J.P.; Ferreira, E.C.; Rocha, M. , Differential evolution for the offline and online optimization of fed-batch fermentation processes. In: Chakraborty, U.K. (ed.), Advances in differential evolution. Studies in Computational Intelligence, Springer verlag, Berlin, 2008, pp. 299-317.

- Liu, Y.; Gunawan, R. Bioprocess optimization under uncertainty using ensemble modeling. J. Biotechnol. 2017, 244, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, F.; Keil, F.J.; Luus, R. , Comparison of optimization methods for a fed-batch reactor, Hung. J. Ind. Chem., 1996, 23, 81–160. [Google Scholar]

- Amribt, Z.; Dewasme, L.; Wouwer, A.V.; Bogaerts, P. Optimization and robustness analysis of hybridoma cell fed-batch cultures using the overflow metabolism model. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2014, 37, 1637–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonvin, D. Optimal operation of batch reactors—a personal view. J. Process. Control. 1998, 8, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonvin, D. , Real-time optimization, MDPI, Basel, 2017.

- DiBiasio, D. , Introduction to the control of biological reactors. In: Shuler, M.L. (ed.), Chemical engineering problems in biotechnology, American Institute of Chemical Engineers, New York, 1989, pp. 351-391.

- Abel, O.; Marquardt, W. Scenario-integrated on-line optimisation of batch reactors. J. Process. Control. 2003, 13, 703–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lee, K.S.; Lee, J.H.; Park, S. An on-line batch span minimization and quality control strategy for batch and semi-batch processes. Control. Eng. Pr. 2001, 9, 901–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruppen, D.; Bonvin, D.; Rippin, D. Implementation of adaptive optimal operation for a semi-batch reaction system. 22. [CrossRef]

- Loeblein, C.; Perkins, J.; Srinivasan, B.; Bonvin, D. Performance analysis of on-line batch optimization systems. Comput. Chem. Eng. 1997, 21, S867–S872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, M.; Qiu, H. , Process control engineering: a textbook for chemical, mechanical and electrical engineers, Gordon and Breach Science, Amsterdam, 1993.

- Maria, G. Enzymatic reactor selection and derivation of the optimal operation policy, by using a model-based modular simulation platform. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2012, 36, 325–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maria, G. Model-Based Optimization of a Fed-Batch Bioreactor for mAb Production Using a Hybridoma Cell Culture. Molecules 2020, 25, 5648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maria, G.; Crişan, M. Operation of a mechanically agitated semi-continuous multi-enzymatic reactor by using the Pareto-optimal multiple front method. J. Process. Control. 2017, 53, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smets, I.Y.; Claes, J.E.; November, E.J.; Bastin, G.P.; Van Impe, J.F. Optimal adaptive control of (bio)chemical reactors: Past, present and future. J. Process Control 2004, 14, 795–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, B.; Bonvin, D.; Visser, E.; Palanki, S. Dynamic optimization of batch processes: II. Role of measurements in handling uncertainty. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2003, 27, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maria, G.; Renea, L. Tryptophan Production Maximization in a Fed-Batch Bioreactor with Modified E. coli Cells, by Optimizing Its Operating Policy Based on an Extended Structured Cell Kinetic Model. Bioengineering 2021, 8, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, E. , Batch-to-batch optimization of batch processes using the STATSIMPLEX search method, Proc. 2nd Mercosur Congress on Chemical Engineering. Rio de Janeiro, Costa Verde, Brasil, 2005, paper #20.

- Engasser, J.-M. Bioreactor engineering: The design and optimization of reactors with living cells. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1988, 43, 1739–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şcoban, A.G.; Maria, G. Model-based optimization of the feeding policy of a fluidized bed bioreactor for mercury uptake by immobilized Pseudomonas putida cells. Asia-Pacific J. Chem. Eng. 2016, 11, 721–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutinas, M.; Kiparissides, A.; Pistikopoulos, E.N.; Mantalaris, A. Bioprocess systems engineering: transferring traditional process engineering principles to industrial biotechnology. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2012, 3, e201210022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisan, M.; Maria, G. Modular Simulation to Determine the Optimal Operating Policy of a Batch Reactor for the Enzymatic Fructose Reduction to Mannitol with the in situ Continuous Enzymatic Regeneration of the NAD Cofactor. Rev. de Chim. 2017, 68, 2196–2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maria, G. Model-based optimisation of a batch reactor with a coupled bi-enzymatic process for mannitol production. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2020, 133, 106628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Quan, H.; Xu, X. Optimal Design of Multiproduct Batch Chemical Process Using Genetic Algorithms. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1996, 35, 3560–3566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, S.S.; Palsson, B.Ø. Effect of initial cell density on hybridoma growth, metabolism, and monoclonal antibody production. J. Biotechnol. 1990, 16, 259–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lübbert, A.; Jørgensen, S.B. Bioreactor performance: a more scientific approach for practice. J. Biotechnol. 2001, 85, 187–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binette, J.-C.; Srinivasan, B. On the Use of Nonlinear Model Predictive Control without Parameter Adaptation for Batch Processes. Processes 2016, 4, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maria, G.; Peptănaru, I.M. Model-Based Optimization of Mannitol Production by Using a Sequence of Batch Reactors for a Coupled Bi-Enzymatic Process—A Dynamic Approach. Dynamics 2021, 1, 134–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotopoulos, J.; Georgakis, C.; Stenger jr., H.G., Uncertainty Issues in the Modeling and Optimization of Batch Reactors with Tendency Models. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1994, 49, 5533–5547. [CrossRef]

- Maria, G.; Crisan, M. Evaluation of optimal operation alternatives of reactors used for d-glucose oxidation in a bi-enzymatic system with a complex deactivation kinetics. Asia-Pacific J. Chem. Eng. 2014, 10, 22–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco-Lara, E.; Weuster-Botz, D. Estimation of optimal feeding strategies for fed-batch bioprocesses. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2005, 28, 71–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, A.; Maria, G. Pareto Optimal Operating Solutions for a Semibatch Reactor Based on Failure Probability Indices. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2012, 35, 1098–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avili, M.G.; Fazaelipoor, M.H.; Jafari, S.A.; Ataei, S.A. , Comparison between batch and fed-batch production of rhamnolipid by Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Iranian Journal of Biotechnology, 2012, 10, 263-269.

- Koller, M. A Review on Established and Emerging Fermentation Schemes for Microbial Production of Polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) Biopolyesters. Fermentation 2018, 4, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinterinwa, O.; Khankal, R.; Cirino, P.C. Metabolic engineering for bioproduction of sugar alcohols. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2008, 19, 461–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Ding, L.; Singleton, M.L.; Idrissi, H.; Hermans, S. Synergistic effects altering reaction pathways: The case of glucose hydrogenation over Fe-Ni catalysts, Applied Catalysis B: Environmental, 2021, 288, 119997.

- Ahmed, M.; Hameed, B. Hydrogenation of glucose and fructose into hexitols over heterogeneous catalysts: A review. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2018, 96, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liese, A.; Seelbach, K.; Wandrey, C. (Eds), Industrial biotransformations, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2006.

- Myande Comp., Fructose syrup production, China, 2024, https://www.myandegroup.com/starch-sugar-technology?ad_account_id=755-012-8242&gad_source=1.

- Marianou, A.A.; Michailof, C.M.; Pineda, A.; Iliopoulou, E.F.; Triantafyllidis, K.S.; Lappas, A.A. Glucose to Fructose Isomerization in Aqueous Media over Homogeneous and Heterogeneous Catalysts. ChemCatChem 2016, 8, 1100–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanover, L.M.; White, J.S. Manufacturing, composition, and applications of fructose. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1993, 58, 724S–732S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitner, C.; Neuhauser, W.; Volc, J.; Kulbe, K.D.; Nidetzky, B.; Haltrich, D. The Cetus Process Revisited: A Novel Enzymatic Alternative for the Production of Aldose-Free D-Fructose. Biocatal. Biotransformation 1998, 16, 365–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaked, Z.; Wolfe, S. Stabilization of pyranose 2-oxidase and catalase by chemical modification. Methods Enz. 1988, 137, 599–615. [Google Scholar]

- Ene, M.D.; Maria, G. , Temperature decrease (30-25oC) influence on bi-enzymatic kinetics of D-glucose oxidation, Journal of Molecular Catalysis B: Enzymatic, 2012, 81, 19-24.

- Maria, G.; Ene, M.D.; Jipa, I. Modelling enzymatic oxidation of d-glucose with pyranose 2-oxidase in the presence of catalase. J. Mol. Catal. B: Enzym. 2011, 74, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maria, G.; Ene, M.D. , Modelling enzymatic reduction of 2-keto-D-glucose by suspended aldose reductase, Chemical & Biochemical Engineering Quarterly, 2013, 27, 385–395.

- Chenault, H.K.; Whitesides, G.M. Regeneration of nicotinamide cofactors for use in organic synthesis. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 1987, 14, 147–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmentier, S.; Arnaut, F.; Soetaert, W.; Vandamme, E.J. , Enzymatic production of D-mannitol with the Leuconostoc pseudomesenteroides mannitol dehydrogenase coupled to a coenzyme regeneration system, Biocatalysis and Biotransformation, 2005, 23, 1-7.

- Gijiu, C.L.; Maria, G.; Renea, L. , Pareto optimal operating policies of a batch bi-enzymatic reactor for mannitol production, Chemical Engineering and Technology, 2024, e202300555. [CrossRef]

- Leonida, M.D. Redox Enzymes Used in Chiral Syntheses Coupled to Coenzyme Regeneration. Curr. Med. Chem. 2001, 8, 345–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Wang, P. Cofactor regeneration for sustainable enzymatic biosynthesis. Biotechnol. Adv. 2007, 25, 369–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berenguer-Murcia, A.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R. New Trends in the Recycling of NAD(P)H for the Design of Sustainable Asymmetric Reductions Catalyzed by Dehydrogenases. Curr. Org. Chem. 2010, 14, 1000–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoreishi, S.; Shahrestani, R.G. Innovative strategies for engineering mannitol production. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2009, 20, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treitz, G.; Maria, G.; Giffhorn, F.; Heinzle, E. Kinetic model discrimination via step-by-step experimental and computational procedure in the enzymatic oxidation of d-glucose. J. Biotechnol. 2001, 85, 271–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannwarth, M.; Heckmann-Pohl, D.; Bastian, S.; Giffhorn, F.; Schulz, G.E. Reaction Geometry and Thermostable Variant of Pyranose 2-Oxidase from the White-Rot Fungus Peniophora sp., Biochemistry 2006, 45, 6587–6595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberfroid, M. , Inulin-Type Fructans, CRC press, Boca Raton, 2005.

- Ricca, E.; Calabrò, V.; Curcio, S.; Iorio, G. The State of the Art in the Production of Fructose from Inulin Enzymatic Hydrolysis. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2007, 27, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricca, E.; Calabrò, V.; Curcio, S.; Iorio, G. Fructose production by chicory inulin enzymatic hydrolysis: A kinetic study and reaction mechanism. Process. Biochem. 2009, 44, 466–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricca, E.; Calabrò, V.; Curcio, S.; Iorio, G. Optimization of inulin hydrolysis by inulinase accounting for enzyme time- and temperature-dependent deactivation. Biochem. Eng. J. 2009, 48, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, E.G.; Catana, R.; Ferreira, B.S.; Luque, S.; Fernandes, P.; Cabral, J.M. Towards the development of a membrane reactor for enzymatic inulin hydrolysis. J. Membr. Sci. 2006, 273, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, J.; Catana, R.; Ferreira, B.; Cabral, J.; Fernandes, P. Design and characterisation of an enzyme system for inulin hydrolysis. Food Chem. 2005, 95, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toneli, J.T.C.L.; Park, K.J.; Murr, F.E.X.; Martinelli, P.O. , Rheological bahavior of concentrated inulin solution: Influence of soluble solids concentration and temperature. Journal of Texture Studies, 2008, 39, 369–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bot, A.; Erle, U.; Vreeker, R.; Agterof, W.G. Influence of crystallisation conditions on the large deformation rheology of inulin gels. Food Hydrocoll. 2004, 18, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelps, C.F. , The physical properties of inulin solutions. Biochem. J., 1965, 95, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendayan, M.; Rasio, E.A. Transport of insulin and albumin by the microvascular endothelium of the rete mirabile. J. Cell Sci. 1996, 109, 1857–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.T.C.R. , Fructose solubility in water and ethanol/water, AIChE Meeting, 2009, paper 1543.

- Chen, J.C.P.; Chou, G.C. , Chen-Chou cane sugar handbook, Wiley, New York, 1993, pp. 24.

- Okutomi, T.; Nemoto, M.; Mishiba, E.; Goto, F. Viscosity of diluent and sensory level of subarachnoid anaesthesia achieved with tetracaine. Can. J. Anaesth. 1998, 45, 84–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, R.L.C.; Giordano, R.C.; Cooney, C.L. , A study on intra-particle diffusion effects in enzymatic reactions: glucose-fructose isomerisation. Bioprocess Engineering, 2000, 23, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.; Oliveira, M.; Maugeri, F. Modelling thermal stability and activity of free and immobilized enzymes as a novel tool for enzyme reactor design. Bioresour. Technol. 2007, 98, 3142–3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catana, R.; Eloy, M.; Rocha, J.; Ferreira, B.; Cabral, J.; Fernandes, P. Stability evaluation of an immobilized enzyme system for inulin hydrolysis. Food Chem. 2006, 101, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.Y.; Byun, S.M.; Uhm, T.B. Hydrolysis of inulin from Jerusalem artichoke by inulinase immobilized on aminoethylcellulose. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 1982, 4, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.H.; Rhee, S.K. Fructose production from Jerusalem artichoke by inulinase immobilized on chitin. Biotechnol. Lett. 1989, 11, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, T.; Ogata, Y.; Shitara, A.; Nakamura, A.; Ohta, K. Continuous production of fructose syrups from inulin by immobilized inulinase from Aspergillus niger mutant 817. J. Ferment. Bioeng. 1995, 80, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.W.; Kim, D.H.; Kim, B.W.; Song, S.K. Production of inulo-oligosaccharides from inulin by immobilized endoinulinase from Pseudomonas sp. J. Ferment. Bioeng. 1997, 84, 369–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.K.; Singh, D.P.; Kaur, N.; Singh, R. , Production, purification and immobilisation of inulinase from Kluyveromyces fragilis, J. Chem. Tech. Biotechnol., 1994, 59, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenling, W.; Le Huiying, W.W.; Shiyuan, W. Continuous preparation of fructose syrups from Jerusalem artichoke tuber using immobilized intracellular inulinase from Kluyveromyces sp. Y-85. Process. Biochem. 1999, 34, 643–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Workman, W.E.; Day, D.F. Enzymatic hydrolysis of inulin to fructose by glutaraldehyde fixed yeast cells. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1984, 26, 905–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tewari, Y.B.; Goldberg, R.N. Thermodynamics of the conversion of aqueous glucose to fructose. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 1985, 11, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illanes, A.; Zúñiga, M.E.; Contreras, S.; Guerrero, A. Reactor design for the enzymatic isomerization of glucose to fructose. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 1992, 7, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.S.; Hong, J. Kinetics of glucose isomerization to fructose by immobilized glucose isomerase: anomeric reactivity of d-glucose in kinetic model. J. Biotechnol. 2000, 84, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straathof, A.J.J. , Adlercreutz, P., Applied biocatalysis, Harwood Academic Publ., Amsterdam, 2005.

- Dehkordi, A.M.; Safari, I.; Karima, M.M. Experimental and modeling study of catalytic reaction of glucose isomerization: Kinetics and packed-bed dynamic modeling. AIChE J. 2008, 54, 1333–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, M. An introduction to chemistry, Chiral publ., 2013, https://preparatorychemistry.com/Bishop_contact.html.

- Laos, K.; Harak, M. , The viscosity of supersaturated aqueous glucose, fructose and glucose-fructose solutions, J. Food Physics, 2014, 27, 27–30. [Google Scholar]

- Bui, A.; Nguyen, M. Prediction of viscosity of glucose and calcium chloride solutions. J. Food Eng. 2004, 62, 345–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maria, G.; Renea, L.; Gheorghe, D. , In-silico optimization of a FBR for ethanol production by using several algorithms and operating alternatives, Revue Roumaine de Chimie, 2024, 70, in-press.

- Moser, A. , Bioprocess technology - kinetics and reactors, Springer Verlag, Berlin, 1988.

- Maria, G.; Renea, L.; Maria, C. Multiobjective Optimization of a Fed-Batch Bienzymatic Reactor for Mannitol Production. Dynamics 2022, 2, 270–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.S. , Engineering optimization – Theory and practice, Wiley, New York, 2009, Chapter 14.10.

- Maria, G. , Adaptive Random Search and Short-Cut Techniques for Process Model Identification and Monitoring, AIChE Symp. Series, 1998, 94, 351–359. [Google Scholar]

- Maria, G. , ARS combination with an evolutionary algorithm for solving MINLP optimization problems. In: Hamza, M.H.(ed.), Modelling, identification and control, IASTED/ACTA Press, Anaheim (CA, USA), 2003, pp. 112-118.

- Dutta, R. , Fundamentals of biochemical engineering, Springer, Berlin, 2008.

- Bickerstaff, G.F. (Ed.), Immobilization of Enzymeas and Cells, Humana Press Inc., Totowa (New Jersey), 1997.

- Muscalu, C.; Maria, G. Pareto optimal operating solutions for a catalytic reactor for benzene oxidation based on safety indices and an extended process kinetic model, Revue Roumaine de Chimie, 2016, 61, 881-892.

- Dan, A.; Maria, G. , Effect of batch time on the Pareto optimal operating solutions of a chemical reactor based on failure probability indices, Environmental Engineering and Management Journal, 2013, 12, 245-250. https://www.eemj.eu/index.

- Dan, A.; Maria, G. Pareto optimal operating solutions for a catalytic reactor for butane oxidation based on safety indices, U.P.B. Sci. Bull., Series B – Chemie, 2014, 76, 35-48. http://www.scientificbulletin.upb.ro/.

- Maria, G.; Khwayyir, H.H.S.; Dinculescu, D. Derivation of Pareto optimal operating policies based on safety indices for a catalytic multitubular reactor used for nitrobenzene hydrogenation, Chemical & Biochemical Engineering Quarterly, 2016, 30, 279-290. [CrossRef]

| Characteristics |

Glucose isomerization [a,d] |

Cetus two steps process [b] | Inulin hydrolysis [c] |

| Number of steps | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Conversion (%) | 50 (limited by the equilibrium) [d] |

99 | 99.5 |

| Raw-materials availability | Glucose from the starch of crops, mollases, cellulose, and food processing byproducts [Kanagasabai etal.,2023; Akbas and Stark,2016] | genetically modified chicory crop; cultures of Aspergillus sp. | |

| Impurities in the product | yes | traces | negligibles |

| Reaction type | Enzymatic isomerization | Enzymatic oxidation (step 1), followed by enzymatic reduction (step 2) | Enzymatic hydrolysis |

| Enzyme mobility | Immobilized [d] | Free (suspended) | immobilized |

| Enzyme stability, and other additives | Intra-cellular glucose-isomerase (e.g. Streptomyces murinus) of low stability; metal (Al) salts |

Pyranose 2-oxidase (P2Ox) and catalase (step 1); aldose reductase and NAD(P)H (step 2); enzymes are very costly |

Inulinase |

| Temperature | 50-60oC | 25-30oC (50-60oC)/ 30oC |

55oC (40-60oC) |

| Reaction time | 7 h | 3-20 h (step 1); 25 h (step 2) |

13 h |

| pH | 7-8.5 | 6.5-7(-8.5); 7-8.5 |

5.5 |

| Number of reaction steps | 1 isomerization |

2 oxidation (step 1), reduction (step 2) |

1 hydrolysis |

| Coenzyme necessary? | No | yes catalase for (step 1) to prevent P2Ox quick inactivation; NAD(P)H for step 2. NAD(P)H is continuously in-situ regenerated |

No |

| Product purification | Difficult [d] | simple (due to high selectivity) | simple (due to high selectivity) |

| Product purity | 2-5% impurities [d] | High (99.9%) |

High (99.9%) |

| Operating conditions | Value | Remarks |

| Reactor liquid volume | 1 L (initial) | Up to 10 L capacity |

| Temperature / pressure / pH (buffer solution) | 50-55oC / normal / 4.5-5 | Batch time ( tf ) = 780 min. |

| Initial concentrations of Ricca et al. [69] | [S]o = 40 (g/L) [E]o = 97 (U/L) [W]o = 988.4 (g/L) [F]o = 0; [G]o = 0 |

To be optimized within imposed limits (this paper) |

| Optimization limits of control variables (initial BR, or in the FBR feeding)[68] [b,c,d] | [S]o; [S]in ∈ [40-200] g/L [E]o; [E]in ∈ [97-5500] (U/L) [W]o ∈ [988- 4000](g) FL ∈ [5e-4 – 0.01] (L/min) |

For FBR optimization, the W amount depends on the inlet feed flow rate (FL) of aqueous solution |

| Fructose polimerization degree in the inulin (m) | 29 (adopted) | 27-29 Inulin from chicory |

| Number of time-arcs for the optimized FBR (Ndiv) | 5 | FBR with variable feeding |

| Imposed inulin (S) conversion | Min. 90 % | |

| Inulin solubility [b] | 60 g/L (10oC) 160– 400 g/L (50oC), 330 g/L (90oC) | [67,70,74] |

| Inulin solutions viscosity, density [a] | Comparable to those of water | For [S] < 100 g/L [72,73] |

| Fructose solubility | 4000 g/L (ca. 22.2 M) (25°C) | [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fructose] |

| Glucose solution solubility | 5-7M (25-30oC) | [94] |

| Glucose / fructose solution viscosity | Ca. 1-3 cps (for up to 0.3 M) 1000 cps (4.5M, 30oC) |

[95] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).