1. Introduction

The larvae of black soldier fly [BSF, Hermetia illucens L., (Diptera: Stratiomyidae)] possess versatile bioconversion capabilities and offer a nutrient-rich biomass, making them highly valuable for various applications (Chia et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2017; Spranghers et al., 2017). BSF larvae efficiently convert a wide range of waste materials into a consumable and nutritious biomass. The biomass derived from the larvae or pupae can further be processed into food suitable for pets or humans. Additionally, the residual substrate and frass (insect feces) left behind after processing can be repurposed as soil amendments (Lohri et al., 2017; Shelomi et al., 2020). BSF larvae also play a vital role in reducing bacterial contamination in organic substrates due to their voracious feeding behavior and natural antimicrobial properties (Achuoth et al., 2024; Park and Yoe, 2017; Zhang et al., 2022). As they consume organic matter, they break down and metabolize bacterial populations within the substrate. BSF larvae produce antimicrobial peptides that inhibit the growth of harmful bacteria, further aiding in reducing bacterial load (Park and Yoe, 2017; Vogel et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2021). This antimicrobial activity not only sanitizes the substrate but also creates a favorable environment for the larvae's growth. In addition, BSF larvae has shown remarkable capabilities to thrive in substrates contaminated with xenobiotics compounds including antibiotics and pesticides, and to accelerate their degradation (Lalander et al., 2016; Van der Fels-Klerx et al., 2020). For instance, studies have demonstrated that BSF larvae can effectively grow and develop in substrates containing pharmaceuticals and pesticides (Lalander et al., 2016). Furthermore, BSF larvae have also been reported to suppress the populations of other disease-carrying flies in organic manure, such as houseflies (Adjavon et al., 2021). Their efficient bioconversion abilities and adaptability to various organic substrates highlight their potential in addressing food security, waste management, and energy sustainability challenges.

It has been suggested that the series of actions including bioconversion and reduction in pathogen load of substrates are primarily facilitated by the presence of symbiotic gut microbes within the larvae's digestive system (Eke et al., 2023; Engel and Moran, 2013). These symbiotic microbes play a crucial role by producing a variety of digestive enzymes and antibiotics that aid in cleansing the larval diet. As the larvae consume organic matter, the gut microbes break down the feed into smaller, digestible components through enzymatic action. Additionally, these microbes produce antibiotics that target and destroy harmful bacteria present in the feed, thereby helping to maintain the larvae's health and ensure the efficient digestion of nutrients. This symbiotic relationship between BSF larvae and their gut microbes is essential for their survival and contributes significantly to their ability to process a wide range of organic substrates efficiently.

2. Bioconversion Versatility of BSF

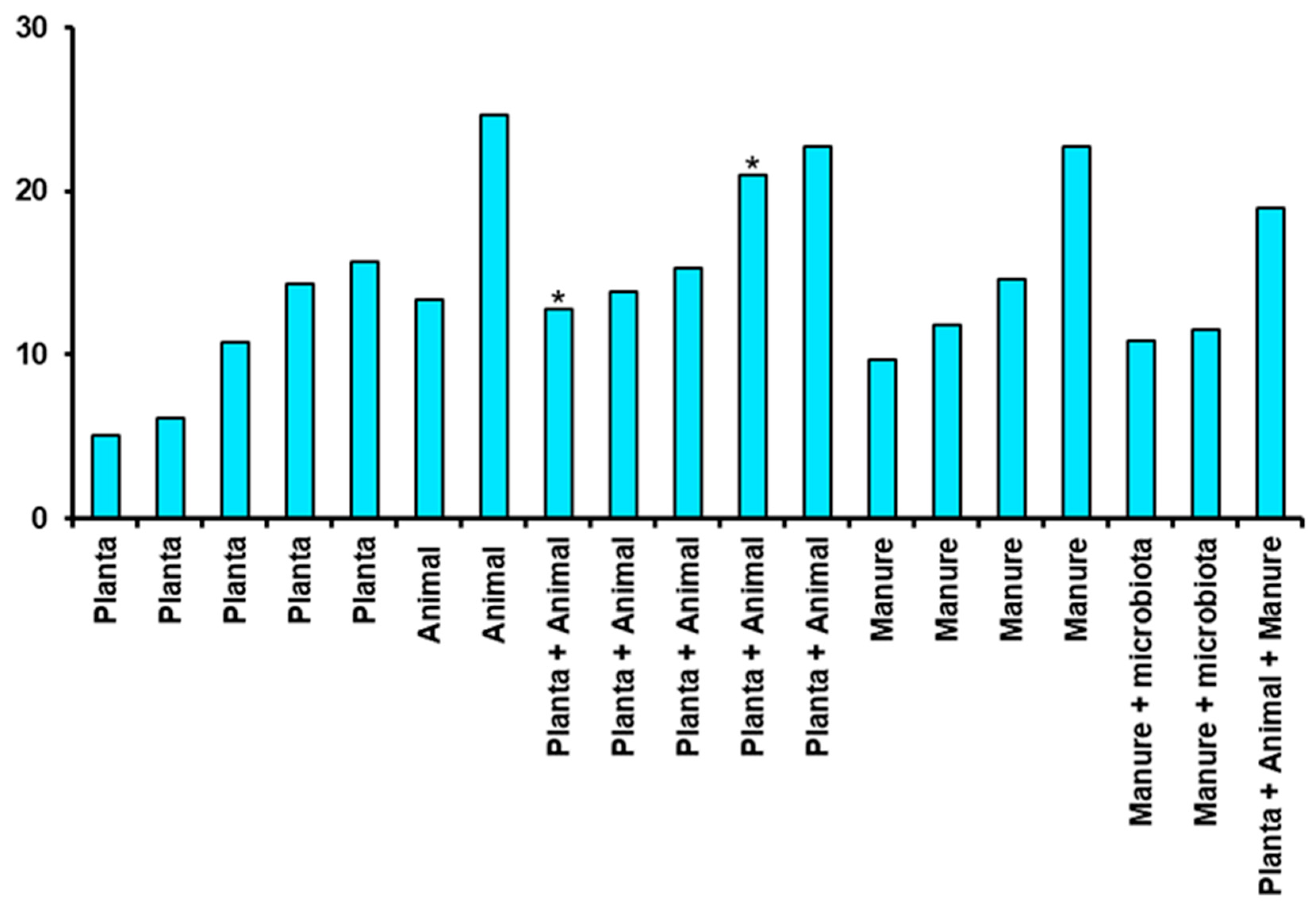

The larvae of BSF possess remarkable capabilities in degrading various organic materials, with material degradation reaching up to 70% (Diener

et al., 2011) and the waste-to-biomass conversion rate up to 22.7 % (Gold

et al., 2020a). However, these conversion rates vary significantly across different substrates (Table 1). Notably, BSF larvae demonstrated high rates of waste-to-biomass conversion with vegetable canteen waste and human feces (both reaching 22.70%), and closely followed by poultry feed (at 21%) (Gold

et al., 2020a). Another study reported a 12.80% biomass conversion rate of poultry feed by BSF larvae, highlighting variations in conversion rates across studies (Lalander

et al., 2019) . Other substrates, such as a mixture of food waste and human feces also exhibited high bio-conversion at 19% (Dortmans, 2015), while conversion rate with food waste and poultry slaughterhouse waste was slightly lower at 13.90% and 13.40%, respectively (Gold

et al., 2020a; Lalander

et al., 2019). Expired fish feed demonstrated a broader range of bioconversion rates, ranging from 6.09% to 24.7% (Rodrigues

et al., 2022), while mushroom root waste and olive oil extraction residue displayed a notably lower waste- to-biomass conversion rate of 5.06% and 6.14%, respectively (Ameixa

et al., 2023; Cai

et al., 2019). However, mixing mushroom root waste with the kitchen waste and their subsequent treatment with BSF larvae, significantly increases the conversion rate to 15.30% (Cai

et al., 2019). Lastly, sewage sludge mixed with the Gainesville diet presented a notably higher conversion rate ranging from 33% to 38.4% for protein (Arnone

et al., 2022). Based on the Table 1, the substrates were categorized under plant based, animal based, or manure to plot a graph for waste to biomass conversion rate maxima (

Figure 1). The graph reflect that plant based substrate in itself were less efficient in regards to waste to biomass conversion. Animal based substrate or a mixture of plants and animal-based substrate provided much efficient conversion with BSF larvae. The substrates containing animal manure also proved to be efficient for conversion efficiency of BSF larva, but conversion efficiency seemed to decrease in presence of specific microbiota.

3. Black Soldier Fly Larvae − A Rich Source of High-Quality Protein and Nutrients

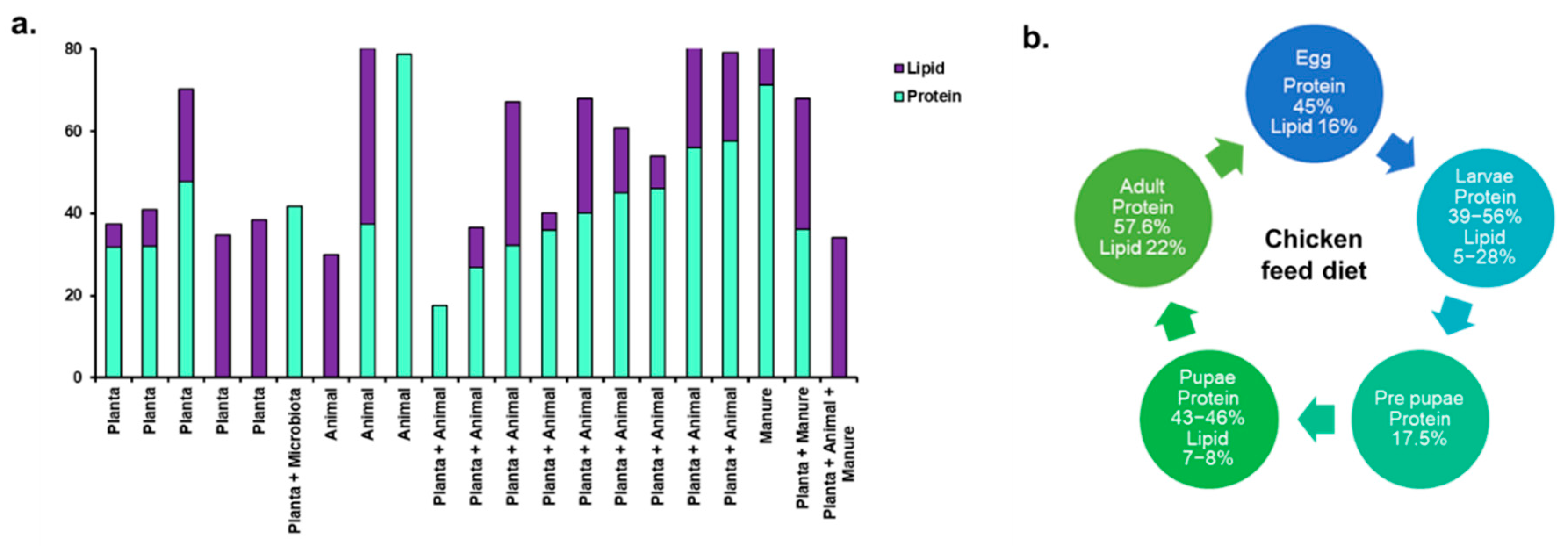

The converted BSF biomass in the form of larvae are primarily employed as a sustainable and highly nutritious source of protein for animal feed formulations, offering an eco-friendly alternative to traditional feed ingredients. As the larvae feed on organic substrates, they accumulate high levels of proteins, fats, and other essential nutrients within their biomass (Table 2). This nutrient-rich composition that is high in protein content with balanced amino acid profile make BSF larvae particularly suitable for livestock, poultry, and aquaculture diets. Furthermore, BSF larvae can be processed into valuable products such as biodiesel, biogas, and organic fertilizers through anaerobic digestion and composting, showcasing their potential for renewable energy production and soil enrichment. The nutritional composition of different developmental stages of BSF, including larva, prepupa, pupa, and postmortem adult, varies significantly depending on their feed source. Table 2 provide insights into the nutritional composition of different life stages of insects, along with their respective substrate sources. This provides insights into how the nutritional profile of BSF larvae can be influenced by the composition of their diet (Chia

et al., 2018; (Heckmann and Gligorescu, 2019). Evidently, BSF larvae can efficiently accumulate lipids when fed with lipid-rich substrates like rapeseed cake, offering a potential source of both protein and lipids for animal feed formulations or other applications. These studies also highlight the versatility of BSF larvae in converting various organic substrates into protein and lipid-rich biomass. From the limited number of studies, it was difficult to discern a specific trend for protein and lipid production in the larval biomass. Still, planta based substrate and poultry feed substrate (kept under ‘plant + animal’ type) seemed optimal for production of protein (

Figure 2). However, these particular substrates showed an erratic trend in case of lipid production.

BSF larvae fed on chicken feed exhibited a rich nutrition profile with 39-56% of protein, 4.8-28% of lipid, and significant levels of vitamin E, calcium, phosphorus, sodium, iron, and zinc (Liu et al., 2017). The high protein content underscores the ability of BSF larvae to efficiently utilize protein-rich substrates for biomass accumulation, whereas variability in lipid content could be attributed to factors such as the composition of the chicken feed and the specific nutrient requirements of the BSF larvae at different stages of development (Spranghers et al., 2017). With a protein content of 175 g/kg of dry matter, BSF prepupae represent a concentrated source of dietary protein. The nutritional analysis also identified substantial amounts of both saturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids, minerals such as calcium and phosphorus, and essential amino acids such as glutamic acid, leucine, lysine, and proline, crucial for protein synthesis, enzyme function, and overall health. The high protein content in BSF larvae is significant, especially considering that protein is an essential nutrient required for growth, development, and maintenance of bodily functions in both animals and humans, while the fatty acids facilitates energy production, maintenance of cell membrane structure, and various physiological processes in organisms. BSF larvae are particularly rich in essential amino acids and micronutrients, facilitating growth, development, and overall health in feeding animals. The amino acids, like leucine, isoleucine, and valine, are essential for muscle protein synthesis and repair, and thus inclusion of BSF larvae in animal diets supports the development of lean muscle mass, improving overall growth and performance of feeding animals. Certain amino acids, such as arginine and glutamine, have immunomodulatory properties and contribute to the proper functioning of the immune system, enhancing feeding animals' ability to resist pathogens and diseases. In addition to amino acids, BSF larvae are rich in micronutrients essential for various physiological functions. They contain vitamins that are crucial for energy metabolism, and enzyme activation, and minerals like calcium, phosphorus, and iron that support bone formation, muscle contraction, and oxygen transport in the body. By incorporating BSF larvae into animal diets, these micronutrients contribute to overall health and vitality (Rehman et al., 2019). That highlighted the significance of the composition of the substrate (in this case, a mixture of dairy manure and chicken manure) in influencing the nutritional profile of BSF larvae. The specific ratio of 2 parts dairy manure to 3 parts chicken manure led to a notable increase in both protein and lipid contents in the resulting larvae. The high protein and lipid contents of 71.20% and 67.80%, respectively, are particularly noteworthy as they surpass typical values reported in literature for BSF larvae. This observation underscores the importance of substrate optimization in BSF larval production systems. Different types of organic waste can vary significantly in their nutrient composition, moisture content, and digestibility, all of which can impact larval growth and nutrient uptake. By carefully selecting and blending waste materials, it might be possible to enhance the nutritional quality of BSF larvae, making them even more valuable as a sustainable protein and lipid source for various applications. In another study, investigated the potential of using BSF larvae to convert fish waste from Sardinella aurita into a valuable protein source (Hopkins et al., 2021). Like many other fish species, Sardinella aurita generates significant amounts of waste during processing, including heads, viscera, and trimmings, which can pose environmental challenges if not managed properly. In this study, BSF larvae were fed with the fish waste, and the resulting larvae were analyzed for their nutritional composition. The researchers found that the larvae reared on this fish waste substrate exhibited a remarkably high protein content of 78.8%. This finding is particularly significant because it demonstrates the ability of BSF larvae to efficiently convert fish waste into biomass with a concentrated protein content. As global demand for protein continues to rise, particularly with concerns about sustainability and environmental impact associated with traditional feed sources such as soy and fish meal, the utilization of insect-based BSF larvae presents a sustainable and economically viable solution. The high protein content of the BSF larvae makes them a promising alternative protein source for various applications, including animal feed and potentially human consumption.

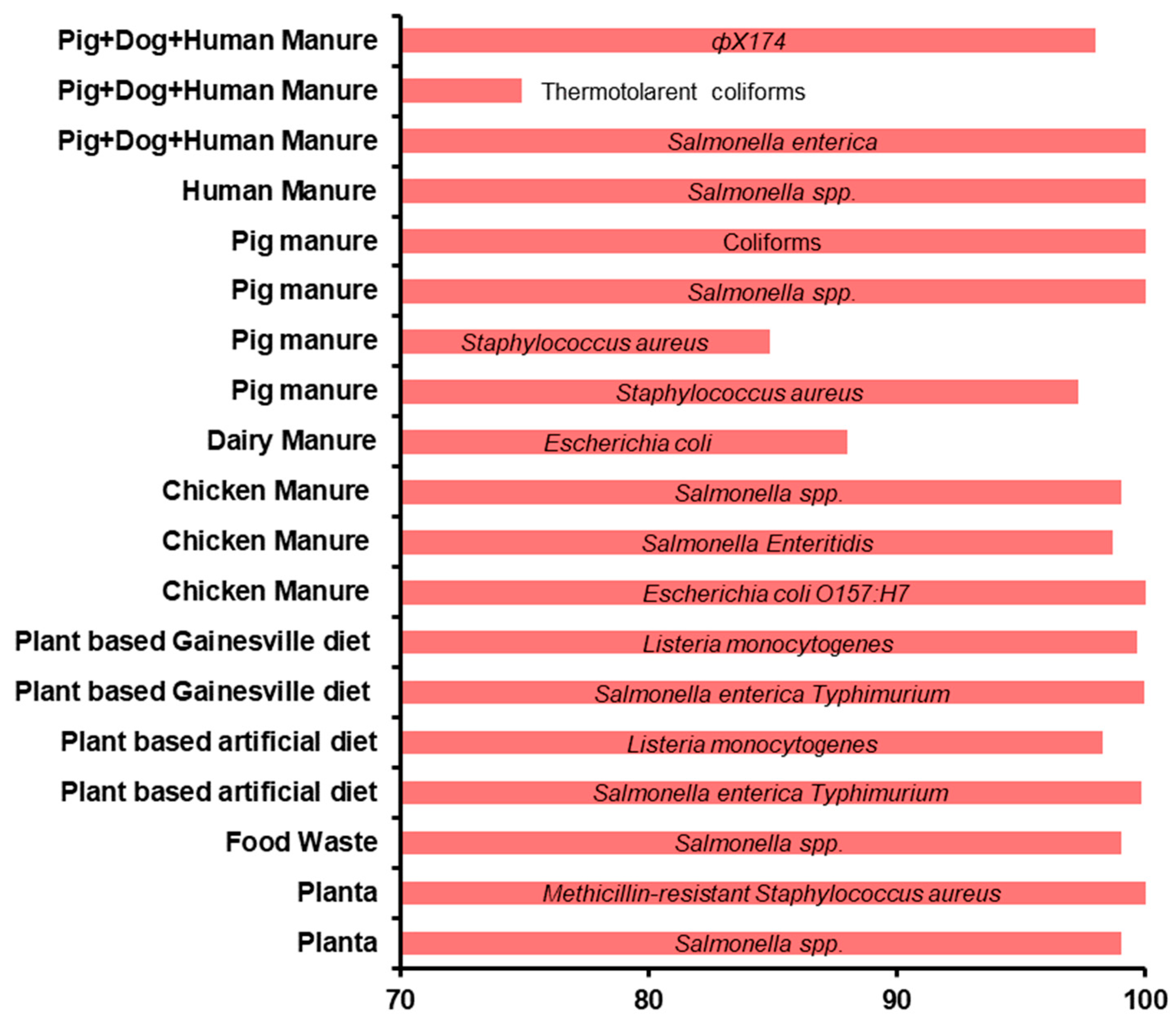

4. Antimicrobial Activity − Diminishing Pathogens Within the Substrate

The feeding behavior of BSF larvae can significantly alter the physical and microbiological properties of their substrate. The microbiological characteristics of substrates are depended on their microbial composition and abundance. The BSF larvae's feeding activity can lead to modification of microbial profile by virtue of changes introduced, such as changes in substrate pH due to metabolic byproducts of feeding that may lead to microbial shift (Grisendi

et al., 2022). Additionally, the breakdown of organic matter by the BSF larvae may influence water activity, and thus microbial composition. Studies have shown a significant decrease in pathogen levels, including

Escherichia coli,

Salmonella spp., and viruses, in BSF-treated systems, making the degraded material safer (Lalander

et al., 2015; Park and Yoe, 2017; Van Looveren

et al., 2022) (

Figure 3). Treatment of chicken manure with BSF larvae, introduces notable changes in the microbial composition of the substrate, with residual substrate depicting a significant decrease in the abundance of Proteobacteria and Bacteroides (Zhang

et al., 2021). The reduction in Proteobacteria abundance is of particular significance as this phylum encompasses many pathogenic microorganisms, rendering the residual substrate safer and less harmful. Similarly, the taxonomic composition analysis of pig manure substrate treated with BSF larvae revealed that larvae were able to effectively reduce the abundance of several bacterial taxa in the residual substrate, including

Streptococcus,

Prevotella, Treponema,

Lactobacillus,

Lachnospiraceae,

Ruminococcaceae, and

Muribaculaceae (Zhang

et al., 2022). The analysis of the microbial community structure highlighted the dominance of three main bacterial phyla: Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, and Bacteroidetes. Among these phyla, Firmicutes were particularly abundant and served a crucial function in the digestion of animal feces by secreting enzymes like proteases and pectinases, facilitating the breakdown of complex organic matter in animal waste and the degradation of indigestible carbohydrates, including those present in straw-associated compost. Awasthi

et al. (2020) investigated the impact of BSF larvae on the survival of pathogenic bacteria in the residual of various organic waste substrates, including chicken manure, pig manure, cow manure, and sewage sludge compost. Before the inoculation of BSF larvae, the substrates revealed a diverse microbial community with Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, and Bacteroidetes found to be the dominant phyla, collectively accounting for 98.78% of the total pathogenic bacteria population. Upon inoculation of BSF larvae into the substrates, there was a noticeable reduction in the relative abundance of bacterial populations, specifically, Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, and Bacteroidetes. The highest reduction (90-92%) in both pathogenic bacteria and organic biomass was observed in chicken manure within the initial 9 days of the experiment. This significant reduction in the abundance of these pathogenic bacterial genera suggests the potential of BSF larvae in mitigating pathogenic bacterial contamination in organic waste management systems.

The BSF larvae reared on contaminated substrates containing Salmonella Typhimurium or Listeria monocytogenes, although not able to completely eliminate these pathogens, but were able to successfully reduce the microbial load of the pathogens present in the substrate (Grisendi et al., 2022). In contrast to this study, Zhang et al. (2022) investigated the biodegradation ability of BSF larvae on the populations of Staphylococcus aureus and Salmonella spp. in pig manure, and found that BSF larvae were able to significantly reduce the counts of these pathogens in the residual manure. The researchers further isolated eight bacterial strains from the BSF larval gut that exhibited inhibitory effects on S. aureus, suggesting that suppression of pathogens could be attributed to the presence of specific microbes in the larval gut. Similarly, (Dong et al., 2021) tested the antimicrobial activity of various products derived from BSF larvae against Clostridium perfringens, and observed a significant inhibition in the viability and growth of C. perfringens. The observed antimicrobial activity was attributed to the presence of many small AMPs (<5 amino acids). Elhag et al. (2022) reported significant impact of BSF larvae in mitigating zoonotic pathogens commonly found in pig manure. They observed that after eight days of conversion, the populations of Coliform bacteria were undetectable in the residual substrate, while the populations of Staphylococcus aureus and Salmonella spp. exhibited significant decreases. Again, the antimicrobial activity of BSF larvae was attributed to AMP, defensin-like peptide 4 (DLP4).

The antibacterial activity of BSF larvae extracts reared on various waste substrates was tested against common pathogens, including Bacillus subtilis, Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Escherichia coli (Achuoth et al., 2024). The study observed that the antibacterial activity against S. aureus was highest with acetic acid extract of the larvae reared on market waste (inhibition zone, 17.00 mm). Additionally, the hexane extract from BSF larvae exhibited rapid bactericidal activity, with a time to kill of 4 hours against B. subtilis, E. coli, and P. aeruginosa. The authors identified lauric acid as the key components in the hexane extracts from BSFL, and attributed observed antibacterial activities on the antimicrobial properties of lauric acid against a wide range of bacteria. In another study, the methanol extracts derived from BSF larvae exhibited significant antibacterial effects against specific Gram-negative bacteria, including Klebsiella pneumoniae, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and Shigella sonnei (Choi et al., 2012). The methanol extracts of BSF larvae not only demonstrated growth inhibition and proliferation of the susceptible bacteria, but also effectively hindered the viability of these bacteria. The authors speculated that the observed antibacterial effect could be attributed to the interaction between the active substances present in the extracts with either the bacterial ribosome or the bacterial cell wall, which may disrupt the essential bacterial processes or structures, leading to inhibition of bacterial growth and proliferation. Nevertheless, no antibacterial effects were observed against Gram-positive bacteria such as Bacillus subtilis, Streptococcus mutans, and Sarcina lutea. In continuation to this study, Park et al. (2014) demonstrated significant efficacy of antimicrobial compounds from methanol extract of BSF larvae against Gram-positive bacterium Staphylococcus aureus, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), and the Gram-negative bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The authors suggested the presence of species-specific antibacterial substances in BSF larvae. Park et al. (2015) demonstrated the species specific antibacterial activity of acetic acid extracts of BSF larva against Pseudomonas marginalis (MIC, 50 mg/mL), Pseudomonas viridiflava (MIC, 100 mg/mL), and Pseudomonas syringae (MIC, 150 mg/mL). The larval extract was found to contain a substances of 3–10 kDa, identified to be mostly alkaline peptides comprising of 18–50 amino acids, as principal antibacterial agent.

BSF larvae produce various AMPs that possess the ability to effectively eliminate a wide range of microorganisms (Vogel et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2021). The DLP4 was first isolated from the hemolymph of BSF larvae, and was reported for its particularly strong antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive bacteria, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) (S.-I. Park et al., 2015). In 2017, two variants of DLP was isolated from BSF larvae: DLP3, which exhibited potent activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, and DLP4, which showed activity only against Gram-positive bacteria (Park and Yoe, 2017). In silico analysis to elucidate the molecular basis of the difference in antibacterial activity, revealed variations in six amino acid sequence (Gly-10, Val-18, Met-23, Arg-25, Asp-32, and Arg-40) between DLP3 and DLP4. It was hypothesized that these specific amino acid differences may be crucial for conferring the ability to kill Gram-negative bacteria. The transcriptomic analysis of BSF larvae revealed that compared to many other insects, BSF larvae possessed a higher number of predicted AMPs from various families, including 6 attacins, 7 cecropins, 26 defensins, 10 diptericins, and 4 knottin-like peptides, totaling 53 putative AMP-encoding genes (Vogel et al., 2018). Moreover, the analysis also identified genes responsible for bacterial recognition, such as those encoding peptidoglycan recognition proteins (PGRPs), Gram-negative bacteria binding proteins (GNBPs), and phenoloxidases. These findings suggest that BSF larvae have evolved a diverse arsenal of immune-related genes to interact with and adapt to the complex microbial communities present in their environment and within their digestive tract. Interestingly, it was observed that the composition of the larval diet shapes the expression of AMPs, which in turn influences the larvae's ability to inhibit the growth and proliferation of diverse bacterial species (Vogel et al., 2018). These AMPs are notably induced by the larvae's diet, particularly when it contains high bacterial loads. The ability of diet to modulate the expression of AMPs and subsequently impact the larvae's antimicrobial activity highlights the intricate interplay between nutrition and immunity in the BSF larvae. The authors deemed the diet-dependent expression of AMPs to be essential for adaption of BSF larvae to the environmental microbiome present in their diet and the core microbiome associated with the host as this adaptation facilitates the digestion of diverse and flexible diets.

The above studies suggests that BSF larvae have some degree of antimicrobial activity or capability to inhibit the proliferation of pathogens during their growth and feeding stages. Nevertheless, some reports contradicts the above. BSF larvae reared on chicken feed inoculated with varying levels of Salmonella, did not exhibit a significant reduction in Salmonella counts in the residual substrate, but observed slower outgrowth of Salmonella when the initial contamination level was lower (De Smet et al., 2021). This finding contrasted with some previous studies that reported a decrease in Salmonella counts in substrate treated with BSF larvae. Similarly, (Moyet et al., 2023) investigated the impact of BSF larvae on the abundance of Bacillus cereus in potato substrate. However, contrary to previous studies, authors did not observe any reduction in B. cereus abundance when the substrate was inoculated with BSF larvae, but instead observed an increase in the amount of B. cereus, as well as an increase in the abundance of the hblD marker gene associated with B. cereus toxin production. The impact of BSF larvae on B. cereus abundance in potato substrate were found to be influenced by the factors such as larval density and the duration of exposure. The BSF larvae possess a unique digestive system where they release digestive enzymes, including amylase, directly into the substrate in which they are feeding. In the case of potato substrate, the extra intestinal digestion by the BSF larvae break down complex carbohydrates into simpler sugars, which the larvae can then absorb as nutrients. This process also make the nutrients more accessible to other organisms present in the environment, including B. cereus, providing them with additional nutrients, facilitating its growth and proliferation. It was speculate that the simultaneous production of digestive enzyme amylase by both BSF larvae and B. cereus could contribute to the observed facilitation of bacterial growth in the presence of BSF larvae, particularly when introduced at lower densities. However, at higher larval densities, the positive effects of this potential synergism between the larvae and B. cereus may be offset by increased competition for resources. With more larvae present, there may be greater consumption of available substrate and nutrients, leaving less for bacterial growth. Thus, while extra intestinal digestion by the larvae may initially benefit B. cereus, the overall outcome may be influenced by factors such as larval density and competition for resources. Müller et al. (2019) assessed the BSF larvae in controlling coccidian parasites (specifically Eimeria nieschulzi and Eimeria tenella) and eggs of the nematode Ascaris suum, and revealed that neither living BSF larvae nor the extracts from their intestines had any discernible effect on the oocysts of the coccidian parasites or the eggs of the nematode. Coccidian parasites and nematodes are significant pathogens affecting livestock and can lead to diseases with detrimental effects on animal health and productivity. The finding raises concerns regarding the potential transmission of parasites through untreated BSF larvae used as animal feed. In case BSF larvae harbor parasitic oocysts or eggs without effective control measures, there might be a risk of introducing these pathogens into the gastrointestinal tracts of animals consuming the larvae as feed, which could than lead to infections and diseases in the animals, impacting their health and productivity. In another study, Van Looveren et al. (2022) investigated the presence of foodborne pathogen Clostridium perfringens in the rearing substrate and processing stages of BSF larvae. Interestingly, there was no evidence of transmission of C. perfringens from the substrate to the larvae. This suggests that, in the context of this production site and based on the samples investigated, the pathogen did not colonize the larvae. This also indicated that the BSF larvae were not acting as carriers or reservoirs for C. perfringens in this particular context. However, these results highlight the importance of ongoing monitoring of pathogens by the insect producers, and underscores the necessity of implementing and maintaining good hygiene practices to prevent contamination throughout the production process.

5. Xenobiotic Degradation Activity

Various xenobiotics, including antibiotics and pesticides, pose significant environmental challenges due to their complex molecular structures, high stability, and extended persistence in the environment. However, the BSF larva has been found to significantly reduce the half-life of these xenobiotics, indicating enhanced degradation compared to traditional degradation rates (Lalander et al., 2016). This study investigated the fate of three pharmaceuticals (carbamazepine, roxithromycin, trimethoprim) and two pesticides (azoxystrobin, propiconazole) within a BSF larvae-composting system. The results indicated that all five substances exhibited a shorter half-life in the fly larvae compost, with levels dropping to less than 10% of those observed in the control treatment. Additionally, no bioaccumulation of these substances was detected in the larvae, suggesting that the larvae effectively degraded or metabolized the pharmaceuticals and pesticides during the composting process. Purschke et al. (2017) investigated the extent of bioaccumulation of contaminants in BSF larvae and their effects on larval growth. The results revealed that the heavy metal contamination in the substrate had a detrimental effect on larval growth. This negative impact was evident from the low mass of the larvae at the end of the trial period and a high feed conversion ratio, indicating inefficient utilization of the feed. Specifically, the accumulation of cadmium and lead in the larval tissue was found to be considerable, with bioaccumulation factors (BAFs) of 9 for cadmium and 2 for lead. These BAF values indicate that the larvae accumulated these heavy metals from the contaminated substrate at levels exceeding statutory thresholds for animal feed. This accumulation of toxic heavy metals likely contributed to the observed negative effects on larval development. In contrast, the tested mycotoxins and pesticides were not found to accumulate in the larval tissue. Furthermore, the presence of mycotoxins and pesticides in the rearing substrate did not compromise the growth performance of the BSF larvae, suggesting that unlike heavy metals, mycotoxins and pesticides present in the substrate did not have a significant detrimental effect on larval development or growth. It was observed that BSF larvae can successfully be reared on former food products containing 3-6% plastic fragments or paperboard carton packaging materials without adverse effects on their growth or survival. Despite the presence of plastic or paperboard contaminants in the feed substrate, the larvae exhibited normal growth and survival rates. However, it was observed that the bioaccumulation of cadmium was higher in larvae reared on products contaminated with paperboard carton packaging material compared to those with plastic contamination (Van der Fels-Klerx et al., 2020). This indicated that the type of contaminant can influence the extent of bioaccumulation in BSF larvae. Elevated levels of heavy metals in BSF larvae raise concerns about their safety as feed or food sources, as contaminated larvae could transfer metals to animals or humans consuming them, thereby posing health risks. In another study, it was noted that type of feed influences the heavy metal accumulation in the BSF larvae (Bessa et al., 2021). These findings underscore the importance of assessing the potential risks associated with different types of contaminants in BSF larvae rearing substrates and their implications for larval growth and safety as a sustainable protein source. The potential mechanisms underlying the degradation of antibiotics by the intestinal microorganisms of BSF larvae through the analysis of Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COG) functions, discovered a potential involvement of RNA processing and modification in antibiotic degradation (Ruan et al., 2024) . RNA processing and modification are essential cellular processes involved in gene expression regulation and post-transcriptional modifications of RNA. Certain enzymes involved in RNA processing and modification might possess the ability to metabolize or modify antibiotic molecules, facilitating their degradation or inactivation within the BSF larvae gut microbiota. Secondly, cell mobility emerged as another COG function potentially associated with antibiotic degradation. Microorganisms with enhanced mobility may have a competitive advantage in colonizing antibiotic-rich environments and might possess specific mechanisms for antibiotic degradation or resistance. Lastly, the COG analysis highlighted cell wall/membrane/envelope biology as a relevant functional category in antibiotic degradation. The cell wall, membrane, and envelope are critical structures that mediate interactions between microorganisms and their surrounding environment, including antibiotics. Modifications in cell wall composition or membrane permeability can influence the susceptibility of microorganisms to antibiotics and may also contribute to antibiotic degradation processes. Overall, the COG functions analysis suggested that the intestinal microorganisms of BSF larvae may employ various cellular processes and molecular mechanisms to degrade antibiotics.

6. Conclusions

The review discusses the up-to-date evidences that the substrate composition plays a crucial role in determining the energy content and antibacterial activity of BSF larvae. That underscore the importance of selecting appropriate substrates for rearing larvae, not only for optimizing their growth and development but also for enhancing their potential to produce bioactive compounds with antibacterial properties. The specific components of the larval diet play a crucial role in determining the extent of degradation activity and accumulation factors. Different substrates provide varying amounts and types of nutrients, which affect the metabolic activity of the larvae accordingly, thereby influencing the resulting changes in pH, water activity, and microbial composition (Grisendi et al., 2022). Understanding how the feeding behavior of BSF larvae interacts with the substrate's composition to modify its physical and microbiological characteristics is essential for optimizing the rearing conditions and enhancing the efficiency of BSF-based waste management systems.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Funding

This research was funded by the Israeli Innovation Authority, BSF Consortium, Project No. 79649 to DM.

Conflicts of Interest

All co-authors have approved to participate and declare no conflict of interests.

References

- Abu Bakar, N.-H.; Abdul Razak, S.; Mohd Taufek, N.; Alias, Z. Evaluation of black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) prepupae oil as meal supplementation in diets for red hybrid tilapia (Oreochromis sp.). International Journal of Tropical Insect Science 2021, 41, 2093–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achuoth, M.P.; Mudalungu, C.M.; Ochieng, B.O.; Mokaya, H.O.; Kibet, S.; Maharaj, V.J.; Subramanian, S.; Kelemu, S.; Tanga, C.M. Unlocking the Potential of Substrate Quality for the Enhanced Antibacterial Activity of Black Soldier Fly against Pathogens. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 8478–8489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjavon, F.J.M.A.; Li, X.; Hu, B.; Dong, L.; Zeng, H.; Li, C.; Hu, W. Adult House Fly (Diptera: Muscidae) Response to Black Soldier Fly (Diptera: Stratiomyidae) Associated Substrates and Potential Volatile Organic Compounds Identification. Environmental Entomology 2021, 50, 1037–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ameixa, O.M.C.C.; Pinho, M.; Domingues, M.R.; Lillebø, A.I. Bioconversion of olive oil pomace by black soldier fly increases eco-efficiency in solid waste stream reduction producing tailored value-added insect meals. Plos One 2023, 18, e0287986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnone, S.; De Mei, M.; Petrazzuolo, F.; Musmeci, S.; Tonelli, L.; Salvicchi, A.; Defilippo, F.; Curatolo, M.; Bonilauri, P. Black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens L.) as a high-potential agent for bioconversion of municipal primary sewage sludge. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2022, 29, 64886–64901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, M.K.; Liu, T.; Awasthi, S.K.; Duan, Y.; Pandey, A.; Zhang, Z. Manure pretreatments with black soldier fly Hermetia illucens L. (Diptera: Stratiomyidae): A study to reduce pathogen content. Science of the Total Environment 2020, 737, 139842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bessa, L.W.; Pieterse, E.; Marais, J.; Dhanani, K.; Hoffman, L.C. Food Safety of Consuming Black Soldier Fly (Hermetia illucens) Larvae: Microbial, Heavy Metal and Cross-Reactive Allergen Risks. Foods 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohm, K.; Hatley, G.A.; Robinson, B.H.; Gutiérrez-Ginés, M.J. Black Soldier Fly-based bioconversion of biosolids creates high-value products with low heavy metal concentrations. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2022, 180, 106149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Zhang, K.; Zhong, W.; Liu, N.; Wu, X.; Li, W.; Zheng, L.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, J. Bioconversion-Composting of Golden Needle Mushroom (Flammulina velutipes) Root Waste by Black Soldier Fly (Hermetia illucens, Diptera: Stratiomyidae) Larvae, to Obtain Added-Value Biomass and Fertilizer. Waste and Biomass Valorization 2019, 10, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, S.Y.; Tanga, C.M.; Osuga, I.M.; Mohamed, S.A.; Khamis, F.M.; Salifu, D.; Sevgan, S.; Fiaboe, K.K.M.; Niassy, S.; van Loon, J.J.A. Effects of waste stream combinations from brewing industry on performance of Black Soldier Fly, Hermetia illucens (Diptera: Stratiomyidae). PeerJ 2018, 6, e5885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.; Yun, J.; Chu, J.; Chu, K. Antibacterial effect of extracts of H ermetia illucens (D iptera: S tratiomyidae) larvae against G ram-negative bacteria. Entomological research 2012, 42, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Smet, J.; Vandeweyer, D.; Van Moll, L.; Lachi, D.; Van Campenhout, L. Dynamics of Salmonella inoculated during rearing of black soldier fly larvae (Hermetia illucens). Food Research, Int. 2021, 149, 110692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, S.; Studt Solano, N.M.; Roa Gutiérrez, F.; Zurbrügg, C.; Tockner, K. Biological treatment of municipal organic waste using black soldier fly larvae. Waste and Biomass Valorization 2011, 2, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Ariëns, R.M.C.; America, A.H.P.; Paul, A.; Veldkamp, T.; Mes, J.J.; Wichers, H.J.; Govers, C. Clostridium perfringens suppressing activity in black soldier fly protein preparations. LWT 2021, 149, 111806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dortmans, B. ; 2015. Valorisation of Organic Waste-Effect of the Feeding Regime on Process Parameters in a. Examensarbete Institutionen För Energi Och Tek. SLU 2015 06.

- Eke, M.; Tougeron, K.; Hamidovic, A.; Tinkeu, L.S.N.; Hance, T.; Renoz, F. Deciphering the functional diversity of the gut microbiota of the black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens): recent advances and future challenges. Animal Microbiome 2023, 5, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elhag, O.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, X.; Cai, M.; Zheng, L.; Jordan, H.R.; Tomberlin, J.K.; Huang, F.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, J. Inhibition of Zoonotic Pathogens Naturally Found in Pig Manure by Black Soldier Fly Larvae and Their Intestine Bacteria. Insects 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsayed, M.; Ran, Y.; Ai, P.; Azab, M.; Mansour, A.; Jin, K.; Zhang, Y.; Abomohra, A.E.-F. Innovative integrated approach of biofuel production from agricultural wastes by anaerobic digestion and black soldier fly larvae. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 263, 121495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, P.; Moran, N.A. The gut microbiota of insects – diversity in structure and function. FEMS Microbiology Reviews 2013, 37, 699–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, M.C.; Islam, M.; Sheppard, C.; Liao, J.; Doyle, M.P. Reduction of Escherichia coli O157:H7 and Salmonella enterica Serovar Enteritidis in Chicken Manure by Larvae of the Black Soldier Fly. Journal of food protection 2004, 67, 685–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Wang, W.; Lu, X.; Zhu, F.; Liu, W.; Wang, X.; Lei, C. Bioconversion performance and life table of black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) on fermented maize straw. Journal of cleaner production, Prod. 2019, 230, 974–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannetto, A.; Oliva, S.; Ceccon Lanes, C.F.; de Araújo Pedron, F.; Savastano, D.; Baviera, C.; Parrino, V.; Lo Paro, G.; Spanò, N.C.; Cappello, T.; Maisano, M.; Mauceri, A.; Fasulo, S. Hermetia illucens (Diptera: Stratiomydae) larvae and prepupae: Biomass production, fatty acid profile and expression of key genes involved in lipid metabolism. Journal of Biotechnology 2020, 307, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gold, M.; Cassar, C.M.; Zurbrügg, C.; Kreuzer, M.; Boulos, S.; Diener, S.; Mathys, A. Biowaste treatment with black soldier fly larvae: Increasing performance through the formulation of biowastes based on protein and carbohydrates. Waste Management 2020, 102, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gold, M.; Egger, J.; Scheidegger, A.; Zurbrügg, C.; Bruno, D.; Bonelli, M.; Tettamanti, G.; Casartelli, M.; Schmitt, E.; Kerkaert, B.; Smet, J. De, Campenhout, L. Van, Mathys, A. Estimating black soldier fly larvae biowaste conversion performance by simulation of midgut digestion. Waste Management 2020, 112, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorrens, E.; Van Looveren, N.; Van Moll, L.; Vandeweyer, D.; Lachi, D.; De Smet, J.; Van Campenhout, L. Staphylococcus aureus in substrates for black soldier fly larvae (Hermetia illucens) and its dynamics during rearing. Microbiology Spectrum 2021, 9, e02183–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grisendi, A.; Defilippo, F.; Lucchetti, C.; Listorti, V.; Ottoboni, M.; Dottori, M.; Serraino, A.; Pinotti, L.; Bonilauri, P. Fate of Salmonella enterica Typhimurium and Listeria monocytogenes in Black Soldier Fly (Hermetia illucens) Larvae Reared on Two Artificial Diets. Foods 2022. [CrossRef]

- Heckmann, L.-H.L.; Gligorescu, A. Bioconversion of Guldborgsund Municipality’s Residual Substrates into Insect Meal. Teknol. Inst. Aarhus 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins, I.; Newman, L.P.; Gill, H.; Danaher, J. The Influence of Food Waste Rearing Substrates on Black Soldier Fly Larvae Protein Composition: A Systematic Review. Insects 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klammsteiner, T.; Walter, A.; Bogataj, T.; Heussler, C.D.; Stres, B.; Steiner, F.M.; Schlick-Steiner, B.C.; Insam, H. Impact of processed food (canteen and oil wastes) on the development of black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) larvae and their gut microbiome functions. Frontiers in microbiology 2021, 12, 619112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalander, C.; Diener, S.; Magri, M.E.; Zurbrügg, C.; Lindström, A.; Vinnerås, B. Faecal sludge management with the larvae of the black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) — From a hygiene aspect. Science of the Total Environment 2013, 458–460, 312–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalander, C.; Diener, S.; Zurbrügg, C.; Vinnerås, B. Effects of feedstock on larval development and process efficiency in waste treatment with black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens). Journal of cleaner production 2019, 208, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalander, C.; Senecal, J.; Gros Calvo, M.; Ahrens, L.; Josefsson, S.; Wiberg, K.; Vinnerås, B. Fate of pharmaceuticals and pesticides in fly larvae composting. Science of the Total Environment 2016, 565, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lalander, C.H.; Fidjeland, J.; Diener, S.; Eriksson, S.; Vinnerås, B. High waste-to-biomass conversion and efficient Salmonella spp. reduction using black soldier fly for waste recycling. Agronomy for Sustainable Development 2015, 35, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Li, M.; Zheng, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, Z.; Ma, Z.; Li, Q. Simultaneous utilization of glucose and xylose for lipid accumulation in black soldier fly. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2015, 8, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Tomberlin, J.K.; Brady, J.A.; Sanford, M.R.; Yu, Z. Black soldier fly (Diptera: Stratiomyidae) larvae reduce Escherichia coli in dairy manure. Environmental entomology 2008, 37, 1525–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Chen, X.; Wang, H.; Yang, Q.; ur Rehman, K.; Li, W.; Cai, M.; Li, Q.; Mazza, L.; Zhang, J.; Yu, Z.; Zheng, L. Dynamic changes of nutrient composition throughout the entire life cycle of black soldier fly. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0182601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohri, C.R.; Diener, S.; Zabaleta, I.; Mertenat, A.; Zurbrügg, C. Treatment technologies for urban solid biowaste to create value products: a review with focus on low-and middle-income settings. Reviews in Environmental Science and Bio/Technology 2017, 16, 81–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loiotine, Z.; Gasco, L.; Biasato, I.; Resconi, A.; Bellezza Oddon, S. Effect of larval handling on black soldier fly life history traits and bioconversion efficiency. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 2024, 11, 1330342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marissa, K.; Matthew, M.; Edward, B.; Andrei, A. Suppression of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Reduction of Other Bacteria by Black Soldier Fly Larvae Reared on Potato Substrate. Microbiology Spectrum 2022, 10, e02321–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneguz, M.; Schiavone, A.; Gai, F.; Dama, A.; Lussiana, C.; Renna, M.; Gasco, L. Effect of rearing substrate on growth performance, waste reduction efficiency and chemical composition of black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) larvae. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 2018, 98, 5776–5784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyet, M.; Morrill, H.; Espinal, D.L.; Bernard, E.; Alyokhin, A. Early Growth Patterns of Bacillus cereus on Potato Substrate in the Presence of Low Densities of Black Soldier Fly Larvae. Microorganisms 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, A.; Wiedmer, S.; Kurth, M. Risk Evaluation of Passive Transmission of Animal Parasites by Feeding of Black Soldier Fly (Hermetia illucens) Larvae and Prepupae. Journal of food protection 2019, 82, 948–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.H.; Kwak, K.W.; Nam, S.H.; Choi, J.Y.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, H.G.; Kim, S.H. Antibacterial activity of larval extract from the black soldier fly Hermetia illucens (Diptera: Stratiomyidae) against plant pathogens. J. Entomol. Zool. Stud 2015, 3, 176–179. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.; Chang, B.S.; Yoe, S.M. Detection of antimicrobial substances from larvae of the black soldier fly, H ermetia illucens (D iptera: S tratiomyidae). Entomological Research 2014, 44, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Yoe, S.M. Defensin-like peptide3 from black solder fly: Identification, characterization, and key amino acids for anti-Gram-negative bacteria. Entomological Research 2017, 47, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-I.; Kim, J.-W.; Yoe, S.M. Purification and characterization of a novel antibacterial peptide from black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) larvae. Developmental & Comparative Immunology 2015, 52, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parodi, A.; De Boer, I.J.M.; Gerrits, W.J.J.; Van Loon, J.J.A.; Heetkamp, M.J.W.; Van Schelt, J.; Bolhuis, J.E.; Van Zanten, H.H.E. Bioconversion efficiencies, greenhouse gas and ammonia emissions during black soldier fly rearing – A mass balance approach. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 271, 122488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parodi, A.; Gerrits, W.J.J.; Van Loon, J.J.A.; De Boer, I.J.M.; Aarnink, A.J.A.; Van Zanten, H.H.E. Black soldier fly reared on pig manure: Bioconversion efficiencies, nutrients in the residual material, greenhouse gas and ammonia emissions. Waste Management 2021, 126, 674–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purschke, B.; Scheibelberger, R.; Axmann, S.; Adler, A.; Jäger, H. Impact of substrate contamination with mycotoxins, heavy metals and pesticides on the growth performance and composition of black soldier fly larvae (Hermetia illucens) for use in the feed and food value chain. Food Additives & Contaminants Part A 2017, 34, 1410–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, K. ur, Rehman, A.; Cai, M.; Zheng, L.; Xiao, X.; Somroo, A.A.; Wang, H.; Li, W.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, J. Conversion of mixtures of dairy manure and soybean curd residue by black soldier fly larvae (Hermetia illucens L.). Journal of Cleaner Production 2017, 154, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, K. ur, Ur Rehman, R.; Somroo, A.A.; Cai, M.; Zheng, L.; Xiao, X.; Ur Rehman, A.; Rehman, A.; Tomberlin, J.K.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, J. Enhanced bioconversion of dairy and chicken manure by the interaction of exogenous bacteria and black soldier fly larvae. Journal of Environmental Management 2019, 237, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, D.P.; Calado, R.; Pinho, M.; Rosário Domingues, M.; Antonio Vázquez, J.; Ameixa, O.M.C.C. Bioconversion and performance of Black Soldier Fly (Hermetia illucens) in the recovery of nutrients from expired fish feeds. Waste Management 2022, 141, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, G.; Ojha, S.; Müller-Belecke, A.; Schlüter, O.K. Fresh aquaculture sludge management with black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens L.) larvae: investigation on bioconversion performances. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 20982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, L.; Ye, K.; Wang, Z.; Xiong, A.; Qiao, R.; Zhang, J.; Huang, Z.; Cai, M.; Yu, C. Characteristics of gut bacterial microbiota of black soldier fly (Diptera: Stratiomyidae) larvae effected by typical antibiotics. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2024, 270, 115861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scala, A.; Cammack, J.A.; Salvia, R.; Scieuzo, C.; Franco, A.; Bufo, S.A.; Tomberlin, J.K.; Falabella, P. Rearing substrate impacts growth and macronutrient composition of Hermetia illucens (L. ) (Diptera: Stratiomyidae) larvae produced at an industrial scale. Scientific reports 2020, 10, 19448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelomi, M.; Wu, M.-K.; Chen, S.-M.; Huang, J.-J.; Burke, C.G. Microbes associated with black soldier fly (Diptera: Stratiomiidae) degradation of food waste. Environmental Entomology 2020, 49, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spranghers, T.; Ottoboni, M.; Klootwijk, C.; Ovyn, A.; Deboosere, S.; De Meulenaer, B.; Michiels, J.; Eeckhout, M.; De Clercq, P.; De Smet, S. Nutritional composition of black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) prepupae reared on different organic waste substrates. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 2017, 97, 2594–2600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- St-Hilaire, S.; Cranfill, K.; McGuire, M.A.; Mosley, E.E.; Tomberlin, J.K.; Newton, L.; Sealey, W.; Sheppard, C.; Irving, S. Fish offal recycling by the black soldier fly produces a foodstuff high in omega-3 fatty acids. Journal of the World Aquaculture Society 2007, 38, 309–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Fels-Klerx, H.J.; Meijer, N.; Nijkamp, M.M.; Schmitt, E.; Van Loon, J.J.A. Chemical food safety of using former foodstuffs for rearing black soldier fly larvae (Hermetia illucens) for feed and food use. Journal of Insects as Food and Feed 2020, 6, 475–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Looveren, N.; Vandeweyer, D.; van Schelt, J.; Van Campenhout, L. Occurrence of Clostridium perfringens vegetative cells and spores throughout an industrial production process of black soldier fly larvae (Hermetia illucens). Journal of Insects as Food and Feed 2022, 8, 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, H.; Müller, A.; Heckel, D.G.; Gutzeit, H.; Vilcinskas, A. Nutritional immunology: Diversification and diet-dependent expression of antimicrobial peptides in the black soldier fly Hermetia illucens. Developmental & Comparative Immunology 2018, 78, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Qian, L.; Wang, W.; Wang, T.; Deng, Z.; Yang, F.; Xiong, J.; Feng, W. Exploring the potential of lipids from black soldier fly: New paradigm for biodiesel production (I). Renewable Energy 2017, 111, 749–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Mazza, L.; Yu, Y.; Cai, M.; Zheng, L.; Tomberlin, J.K.; Yu, J.; van Huis, A.; Yu, Z.; Fasulo, S.; Zhang, J. Efficient co-conversion process of chicken manure into protein feed and organic fertilizer by Hermetia illucens L. (Diptera: Stratiomyidae) larvae and functional bacteria. Journal of environmental management 2018, 217, 668–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, L.; Yu, X.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, J.; Feng, Z.; Zhang, Xiang, Chen, G. ; Zhang, Z. Black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) larvae significantly change the microbial community in chicken manure. Current Microbiology 2021, 78, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Xiao, X.; Elhag, O.; Cai, M.; Zheng, L.; Huang, F.; Jordan, H.R.; Tomberlin, J.K.; Sze, S.; Yu, Z. Hermetia illucens L. larvae–associated intestinal microbes reduce the transmission risk of zoonotic pathogens in pig manure. Microbial Biotechnology 2022, 15, 2631–2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).