Submitted:

17 February 2025

Posted:

18 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Process Description and Model Objective

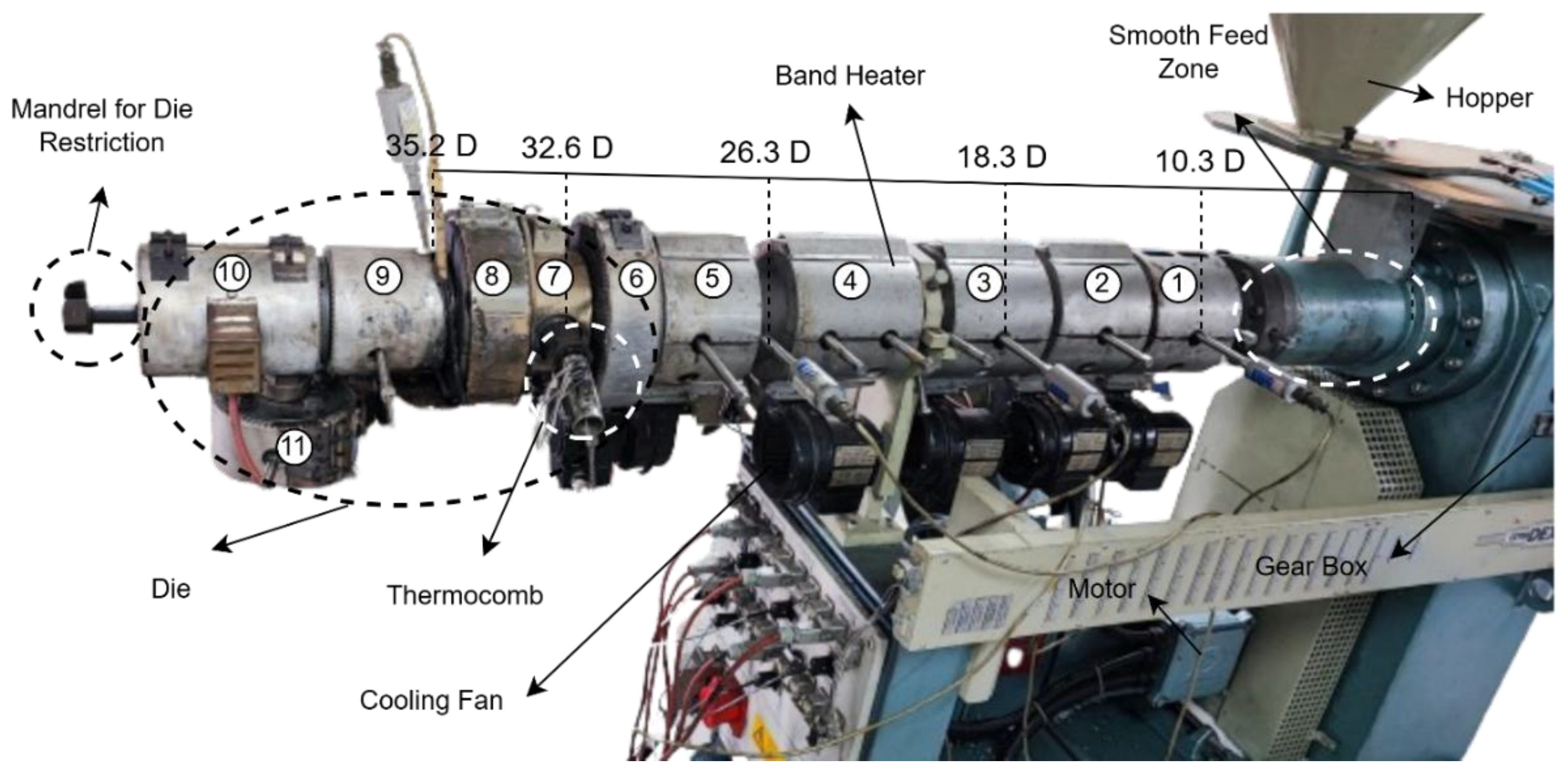

| No. | Zone | Dynisco® Model | Class | Range [bar] | |

| 1 | 10.3 D | Solid Conveying | MDA420-1/2-1.4M-15 | 1 | 0-1400 |

| 2 | 18.3 D | Melting | MDA420-1/2-1.4M-15 | 1 | 0-1400 |

| 3 | 26.3 D | Melting | MDA420-1/2-1.4M-15 | 1 | 0-1400 |

| 4 | 35.2 D | Melt Flow in the Die | Dyna-4-5c-T80 | 1 | 0-500 |

2.2. Data Collection and Processing

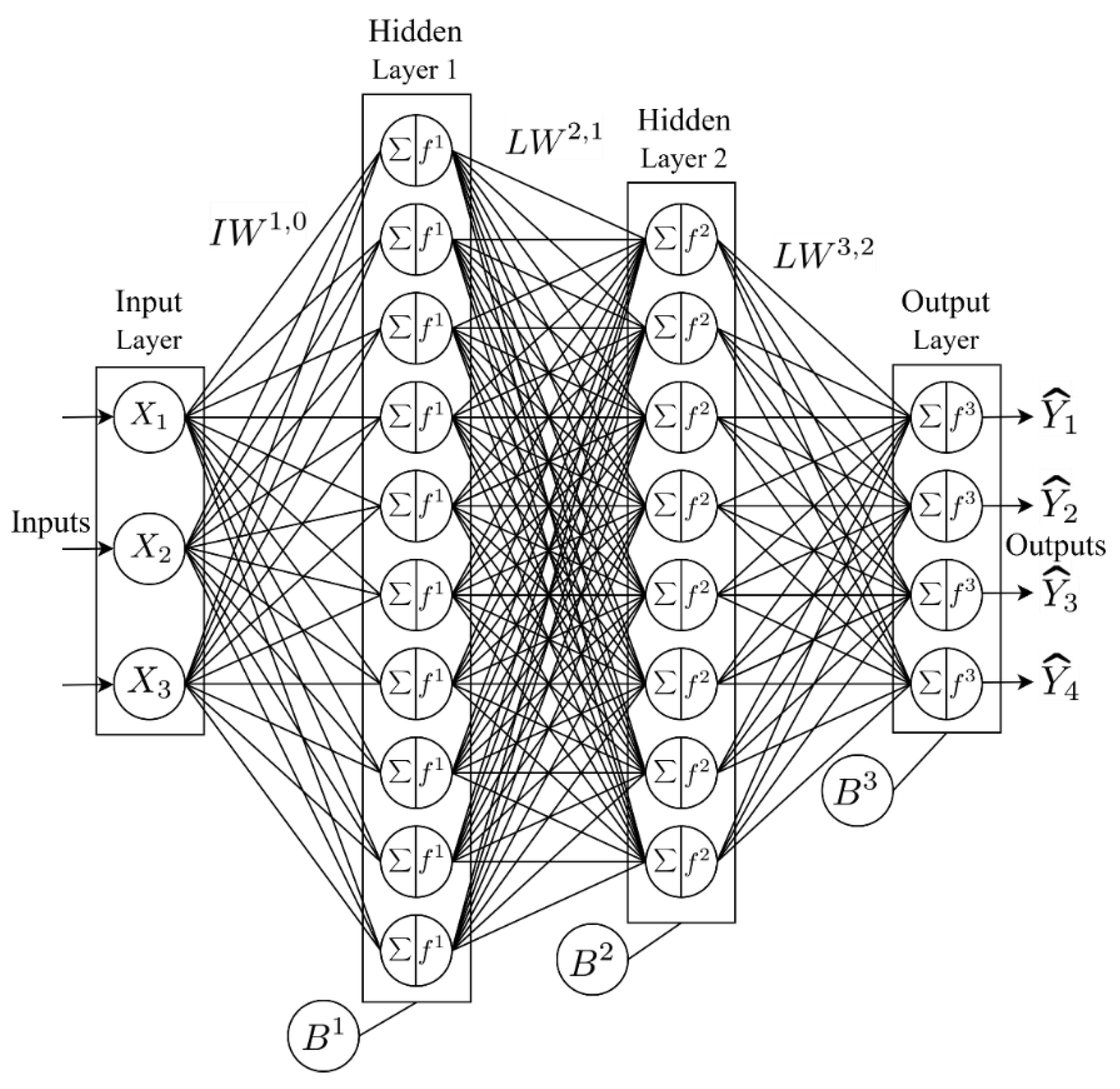

2.3. Feedforward Artificial Neural Networks

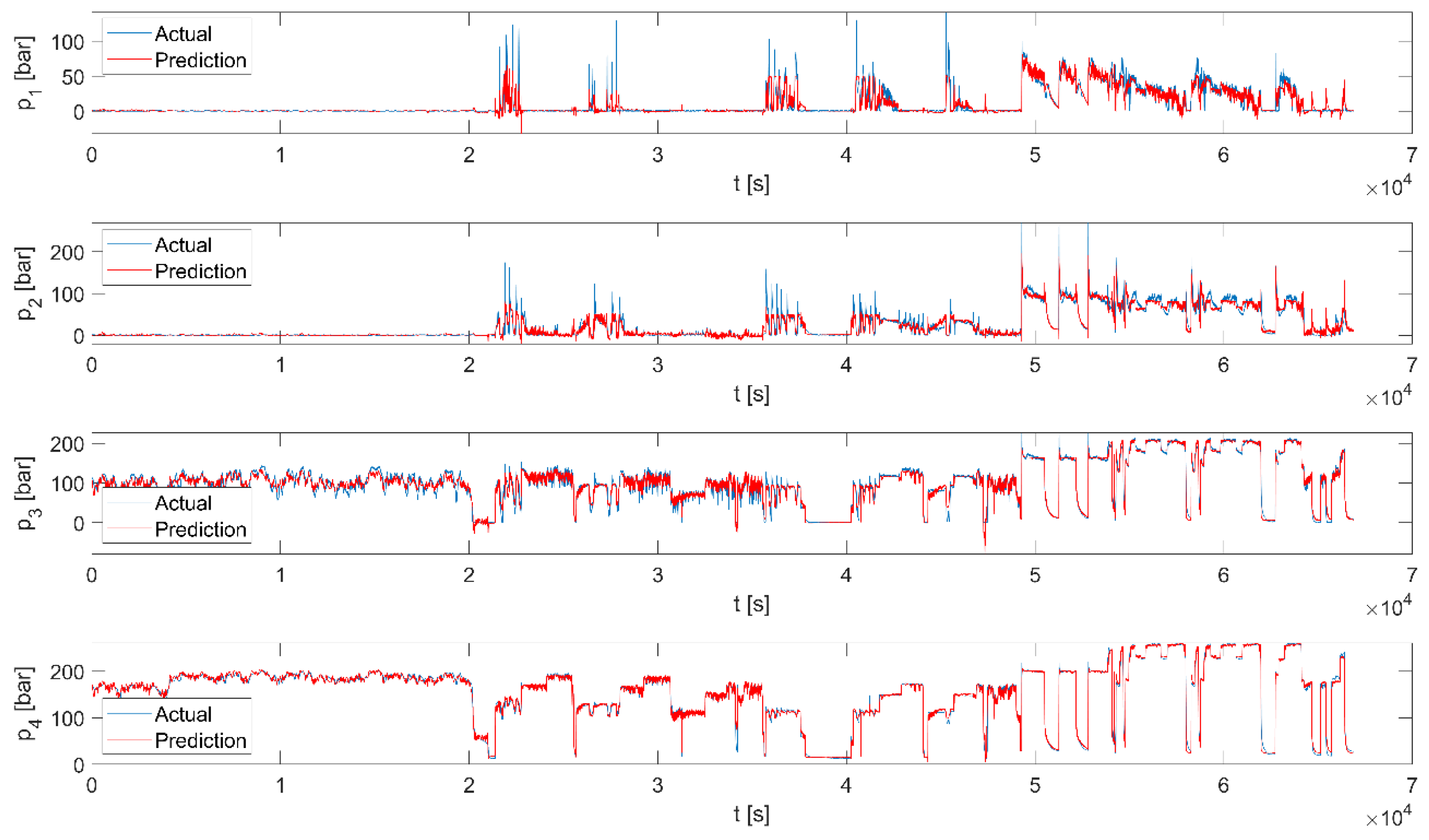

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Nomenclature

| Symbol | Description | Units |

| Activation function | - | |

| Bias | - | |

| Barrel diameter | ||

| Epochs | - | |

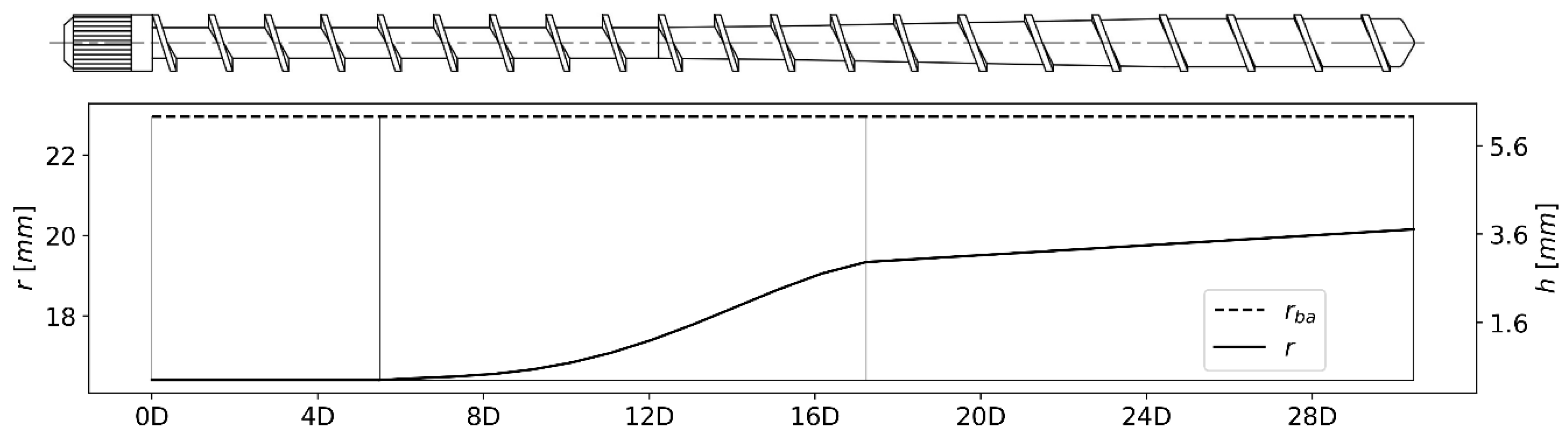

| Channel height | ||

| Hidden layer | - | |

| Identity matrix | ||

| Input variables | - | |

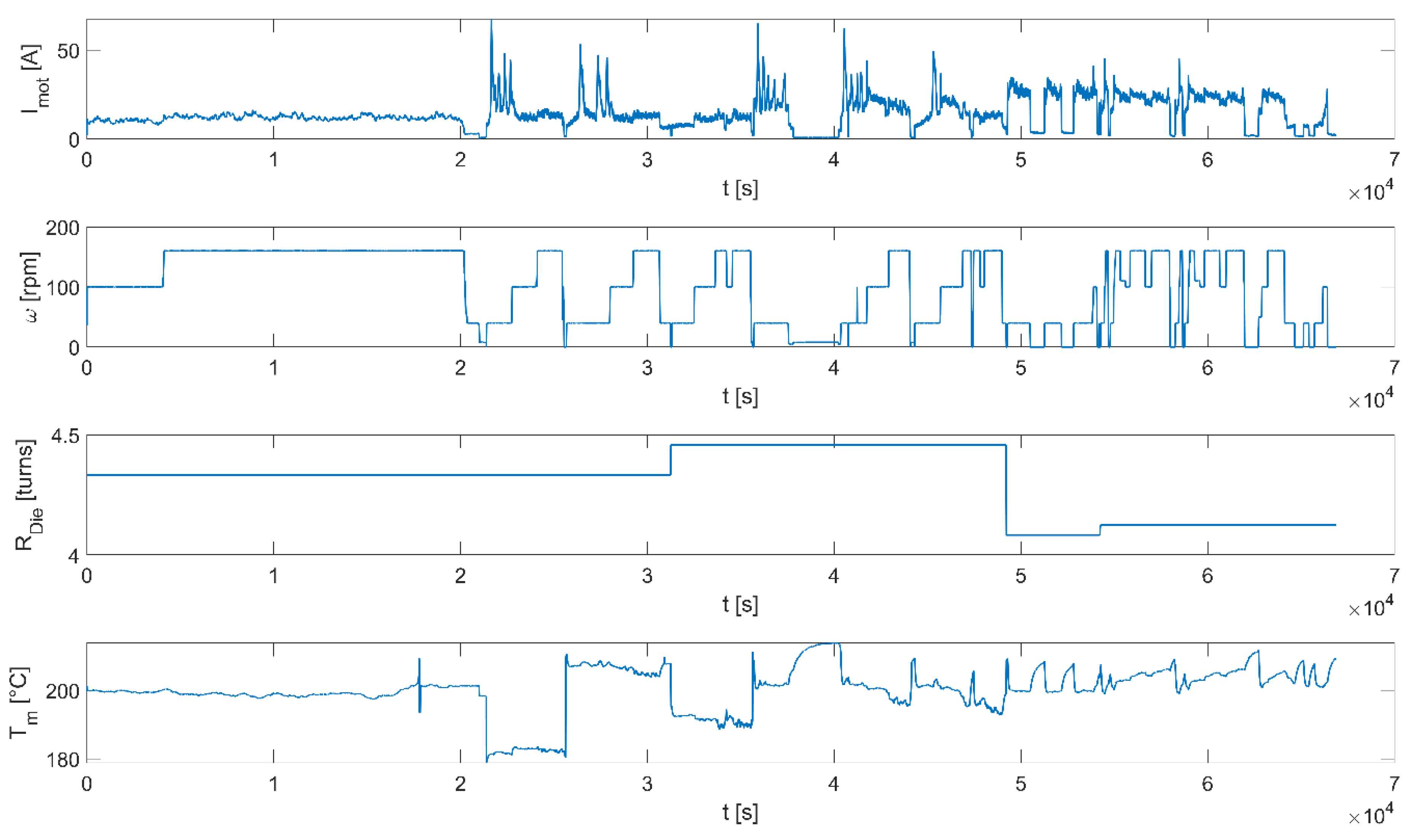

| Motor current demand | ||

| Input layer | - | |

| Weight matrix from the input layer to the first hidden layer | - | |

| Length | ||

| Weight matrix from the first hidden layer to the second hidden layer | - | |

| Weight matrices from the second hidden layer to the output layer | - | |

| Mean squared error | - | |

| Number of data points | - | |

| Number of neurons | - | |

| Activation function of output layer | - | |

| Output layer | - | |

| Output variables | - | |

| Pressure | ||

| Screw radius | ||

| Coefficient of Determination | - | |

| Die restriction | ||

| Time | ||

| Melting temperature | ° | |

| Barrel and die temperature profile | ° | |

| Channel width | ||

| Weights | - | |

| Maximum value of the measured data | - | |

| Minimum value of the measured data | - | |

| Measured data | - | |

| Normalized data | - | |

| Mean value of the observed data | - | |

| Predicted output | - | |

| Maximum value of the normalized data | - | |

| Minimum value of the normalized data | - | |

| Greek symbols | ||

| Adaptive learning rate | - | |

| Rotational screw speed | ||

References

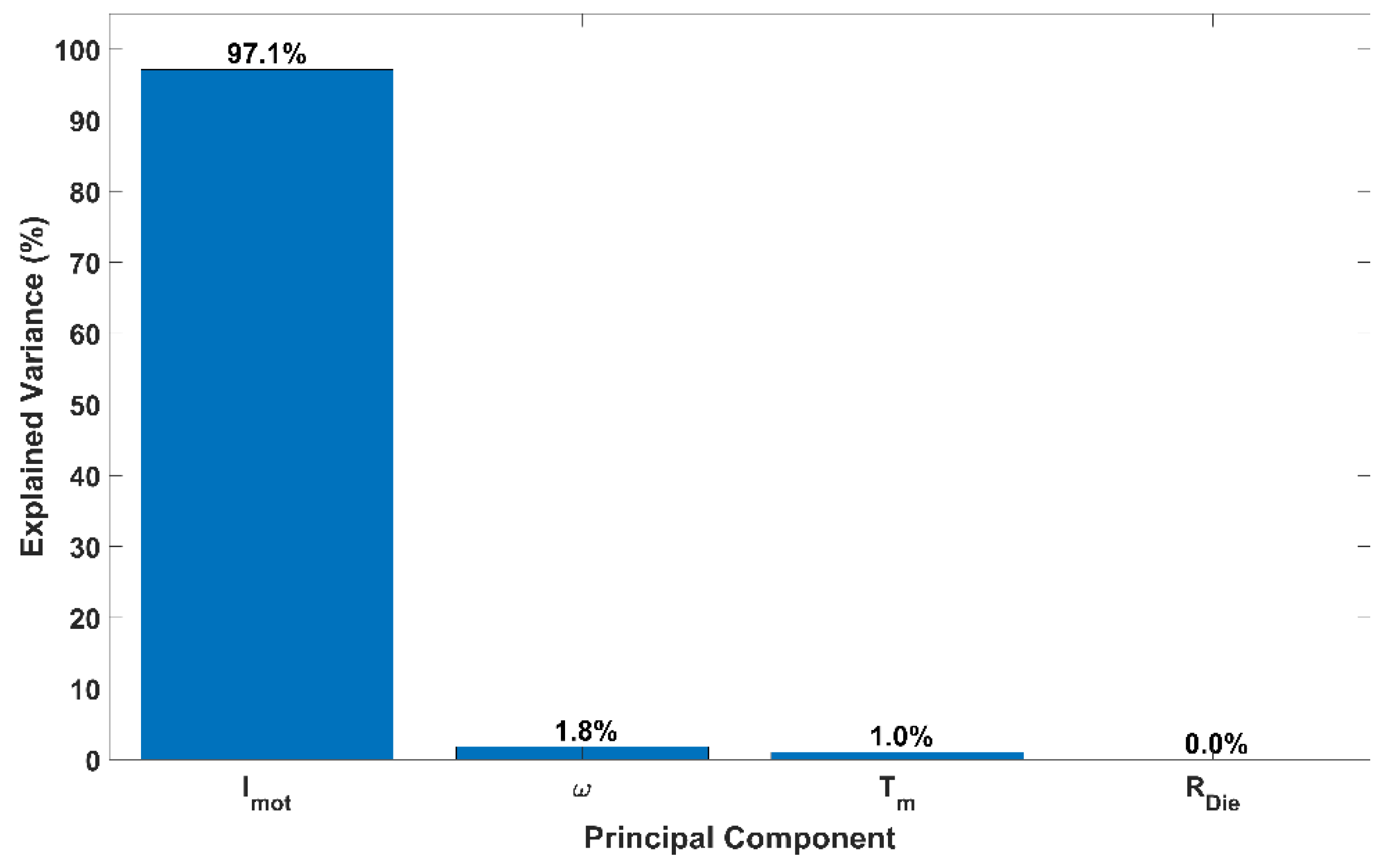

- Abdi, H., & Williams, L. J. (2010). Principal component analysis. In Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Computational Statistics (Vol. 2, Issue 4, pp. 433–459). [CrossRef]

- Abeykoon, C. (2016). Single screw extrusion control: A comprehensive review and directions for improvements. Control Engineering Practice, 51, 69–80. [CrossRef]

- Abeykoon, C., Li, K., Martin, P. J., & Kelly, A. L. (2011). Modelling of melt pressure development in polymer extrusion: Effects of process settings and screw geometry. Proceedings of 2011 International Conference on Modelling, Identification and Control, ICMIC 2011, 197–202. [CrossRef]

- Abeykoon, C., McAfee, M., Li, K., Martin, P. J., Deng, J., & Kelly, A. L. (2010). Modelling the Effects of Operating Conditions on Motor Power Consumption in Single Screw Extrusion (pp. 9–20). [CrossRef]

- Abeykoon, C., McMillan, A., & Nguyen, B. K. (2021). Energy efficiency in extrusion-related polymer processing: A review of state of the art and potential efficiency improvements. In Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews (Vol. 147). Elsevier Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Abeykoon, C., Pérez, P., & Kelly, A. L. (2020). The effect of materials’ rheology on process energy consumption and melt thermal quality in polymer extrusion. Polymer Engineering and Science, 60(6), 1244–1265. [CrossRef]

- Benardos, P. G., & Vosniakos, G. C. (2007). Optimizing feedforward artificial neural network architecture. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence, 20(3), 365–382. [CrossRef]

- Bilski, J., & Wilamowski, B. M. (2017). Parallel Levenberg-Marquardt Algorithm Without Error Backpropagation. Springer International Publishing ICAISC 2017, Part I, LNAI, 10245, 25–39. [CrossRef]

- Buchaniec, S., Gnatowski, M., & Brus, G. (2021). Integration of classical mathematical modeling with an artificial neural network for the problems with limited dataset. Energies, 14(16). [CrossRef]

- Cai, S., Wang, Z., Wang, S., Perdikaris, P., & Karniadakis, G. E. (2021). Physics-informed neural networks for heat transfer problems. Journal of Heat Transfer, 143(6). [CrossRef]

- Carson, J. S. (2005). Introduction to modeling and simulation. Proceedings of the Winter Simulation Conference, 2005., 8 pp.-. [CrossRef]

- De Tommaso, J., Rossi, F., Moradi, N., Pirola, C., Patience, G. S., & Galli, F. (2020). Experimental methods in chemical engineering: Process simulation. In Canadian Journal of Chemical Engineering (Vol. 98, Issue 11, pp. 2301–2320). Wiley-Liss Inc. [CrossRef]

- Diagne, M.; Shang, P.; Wang, Z. (2016a). Feedback Stabilization for the Mass Balance Equations of an Extrusion Process. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control, 61(3), 760–765. [CrossRef]

- Diagne, M.; Shang, P.; Wang, Z. (2016b). Well-posedness and exact controllability of the mass balance equations for an extrusion process. Mathematical Methods in the Applied Sciences, 39(10), 2659–2670. [CrossRef]

- Dyadichev, V. V.; Kolesnikov, A. V.; Menyuk, S. G.; Dyadichev, A. V. (2019). Improvement of extrusion equipment and technologies for processing secondary combined polymer materials and mixtures. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1210(1). [CrossRef]

- Esenttia. (2021). 05H82-AV - Esenttia S.A. https://www.esenttia.co/zp/api/webroot/productos/BT_Espanol/BT_ES_05H82-AV.pdf.

- Estrada, O.; Janna, F. C. (2022). A novel melting model for polymer extrusion: Mechanically induced transition layer removal. Polymer Engineering and Science, 62(10), 3290–3309. [CrossRef]

- Estrada, O.; Ortiz, J. C.; Hernández, A.; López, I.; Chejne, F.; del Pilar Noriega, M. (2020). Experimental study of energy performance of grooved feed and grooved plasticating single screw extrusion processes in terms of SEC, theoretical maximum energy efficiency and relative energy efficiency. Energy, 194. [CrossRef]

- Faegh, M.; Ghungrad, S.; Oliveira, J. P.; Rao, P.; Haghighi, A. (2025). A review on physics-informed machine learning for process-structure-property modeling in additive manufacturing. Journal of Manufacturing Processes, 133, 524–555. [CrossRef]

- Fayose, F. T.; Huan, Z. (2014). Specific mechanical energy requirement of a locally developed extruder for selected starchy crops. Food Science and Technology Research, 20(4), 793–798. [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Zhou, H.; Dong, H. (2019). Using deep neural network with small dataset to predict material defects. Materials and Design, 162, 300–310. [CrossRef]

- Gaspar-Cunha, A.; Monaco, F.; Sikora, J.; Delbem, A. (2022). Artificial intelligence in single screw polymer extrusion: Learning from computational data. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence, 116. [CrossRef]

- Hosain, M. L.; Fdhila, R. B. (2015). Literature Review of Accelerated CFD Simulation Methods towards Online Application. Energy Procedia, 75, 3307–3314. [CrossRef]

- Hyvärinen, M.; Jabeen, R.; Kärki, T. (2020). The modelling of extrusion processes for polymers-A review. In Polymers (Vol. 12, Issue 6). MDPI AG. [CrossRef]

- Jollife, I. T.; Cadima, J. (2016). Principal component analysis: A review and recent developments. In Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences (Vol. 374, Issue 2065). Royal Society of London. [CrossRef]

- Kacir, L.; Tadmor, Z. (1972). Solids Conveying in Screw Extruders Part 111: The Delay Zone". Polymer Engineering and Science, 12, 387–395. [CrossRef]

- Kadyirov, A.; Gataullin, R.; Karaeva, J. (2019). Numerical simulation of polymer solutions in a single-screw extruder. Applied Sciences (Switzerland), 9(24). [CrossRef]

- Kent, R. (2018). Targeting and controlling energy costs. In Energy Management in Plastics Processing (pp. 79–104). Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Kim, D. J.; Kim; Il, S.; Kim, H. S. (2022). Thermal simulation trained deep neural networks for fast and accurate prediction of thermal distribution and heat losses of building structures. Applied Thermal Engineering, 202. [CrossRef]

- Long, Z.; Lu, Y.; Ma, X.; Dong, B. (2018). PDE-Net: Learning PDEs from Data. In International conference on machine learning (pp. 3208–3216). PMLR.

- Marschik, C.; Roland, W.; Osswald, T. A. (2022). Melt Conveying in Single-Screw Extruders: Modeling and Simulation. In Polymers (Vol. 14, Issue 5). MDPI. [CrossRef]

- Meißner, P.; Watschke, H.; Winter, J.; Vietor, T. (2020). Artificial neural networks-based material parameter identification for numerical simulations of additively manufactured parts by material extrusion. Polymers, 12(12), 1–28. [CrossRef]

- Mekras, N.; Artemakis, I. (2012). Using artificial neural networks to model extrusion processes for the manufacturing of polymeric micro-tubes. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 40(1). [CrossRef]

- Patel, H.; Thakkar, A.; Pandya, M.; Makwana, K. (2018). Neural network with deep learning architectures. Journal of Information and Optimization Sciences, 39(1), 31–38. [CrossRef]

- Perera, Y. S.; Li, J.; Kelly, A. L.; Abeykoon, C. (2023). Melt Pressure Prediction in Polymer Extrusion Processes with Deep Learning. IEEE.

- (2023). Plastics - the fast Facts 2023. https://plasticseurope.org/knowledge-hub/plastics-the-fast-facts-2023/.

- Raissi, M.; Perdikaris, P.; Karniadakis, G. E. (2019). Physics-informed neural networks: A deep learning framework for solving forward and inverse problems involving nonlinear partial differential equations. Journal of Computational Physics, 378, 686–707. [CrossRef]

- Rauwendaal, C. (2016). Heat transfer in twin screw compounding extruders. AIP Conference Proceedings, 1779. [CrossRef]

- Rauwendaal, C. (2018). Understanding Extrusion. https://doi.org/10.3139/9781569906996. [CrossRef]

- Roland, W.; Marschik, C.; Kommenda, M.; Haghofer, A.; Dorl, S.; Winkler, S. (2021). Predicting the Non-Linear Conveying Behavior in Single-Screw Extrusion: A Comparison of Various Data-Based Modeling Approaches used with CFD Simulations. International Polymer Processing, 36(5), 529–544. [CrossRef]

- Savytskyi, O.; Tymoshenko, M.; Hramm, O.; Romanov, S. (2020). Application of soft sensors in the automated process control of different industries. E3S Web of Conferences, 166. [CrossRef]

- Udoewa, V.; Kumar, V. (2012). Computational Fluid Dynamics. In Applied Computational Fluid Dynamics. InTech. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Sankaran, S.; Wang, H.; Perdikaris, P. (2023). AN EXPERT’S GUIDE TO TRAINING PHYSICS-INFORMED NEURAL NETWORKS. ArXiv, abs/2308.08468.

| Heating Zone | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| 160 | 190 | 210 | 220 | 220 | 220 | 220 | 220 | 220 | 220 | 220 | |

| 10.3D | 14.3D | 18.3D | 24.3D | 28.3D | 30.5D | 32.3D | 35.8D | 41.8D | 50D | 54.2D |

| s | Metrics | ||||||||||||

| Train | Val | Test | All | Train | Val | Test | All | ||||||

| ,,, | 4 | 10 | 8 | 0.0075 | 0.0078 | 0.0078 | 0.0077 | 0.9894 | 0.9888 | 0.9889 | 0.9892 | 195 | 108 |

| , , , | 4 | 8 | 6 | 0.0092 | 0.0091 | 0.0093 | 0.0092 | 0.9869 | 0.9869 | 0.9868 | 0.9869 | 209 | 41 |

| , , | 3 | 10 | 8 | 0.0093 | 0.0097 | 0.0097 | 0.0096 | 0.9867 | 0.9861 | 0.9863 | 0.9866 | 224 | 80 |

| , , | 3 | 8 | 6 | 0.0099 | 0.0094 | 0.0099 | 0.0097 | 0.9858 | 0.9864 | 0.9860 | 0.9859 | 509 | 147 |

| , | 2 | 10 | 8 | 0.0261 | 0.0254 | 0.0255 | 0.0257 | 0.9623 | 0.9631 | 0.9634 | 0.9626 | 234 | 65 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).