Submitted:

18 February 2025

Posted:

18 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

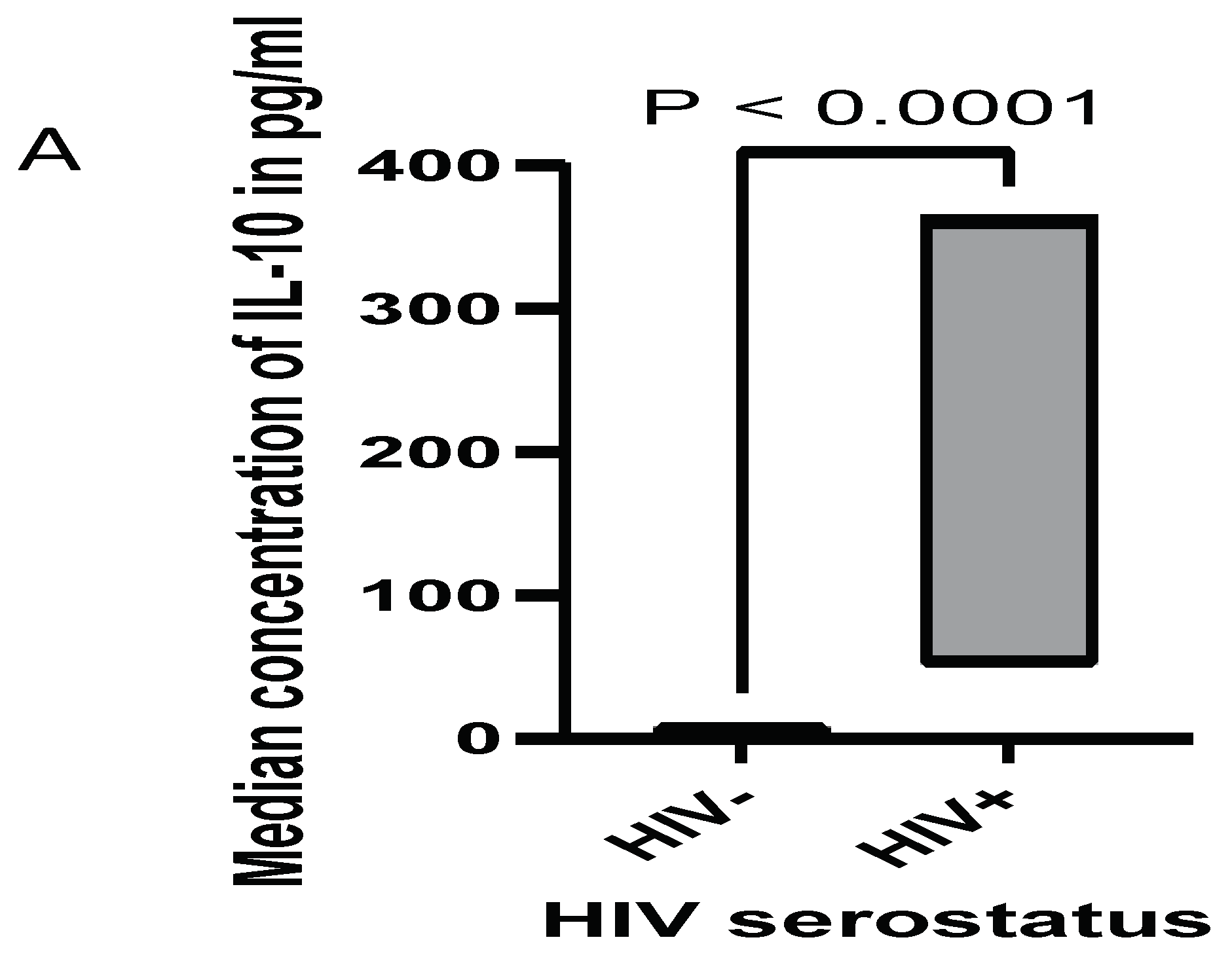

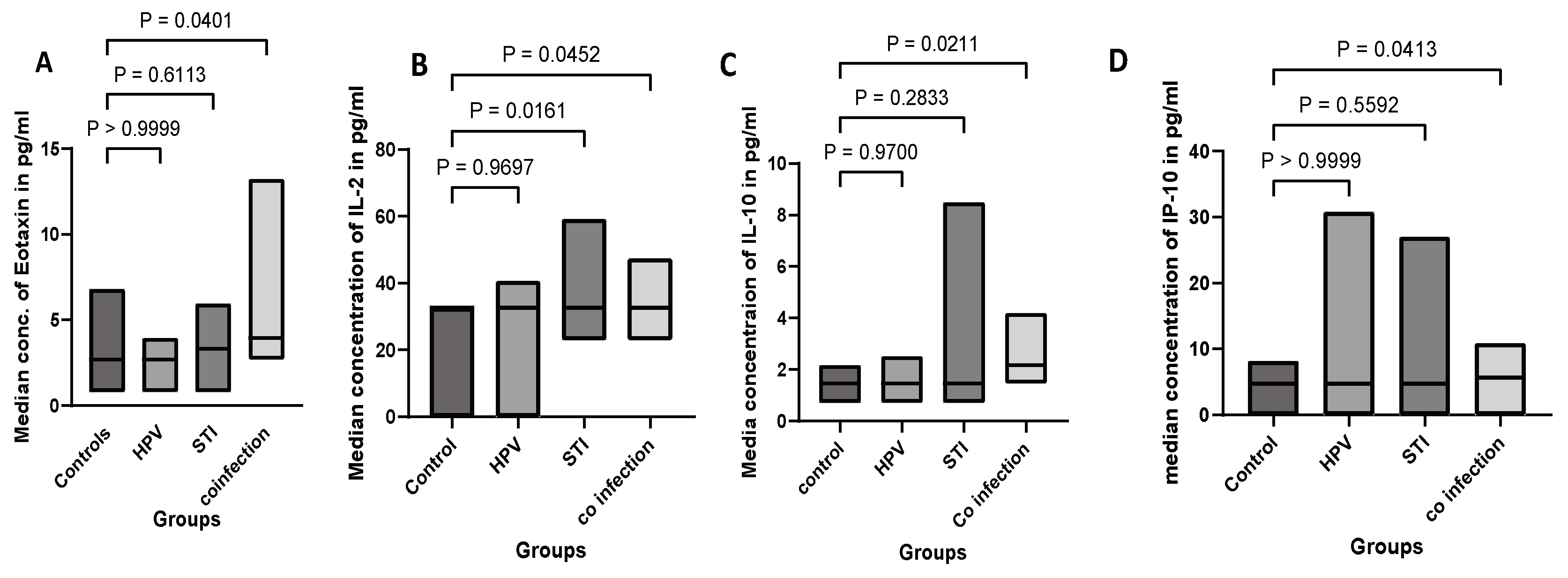

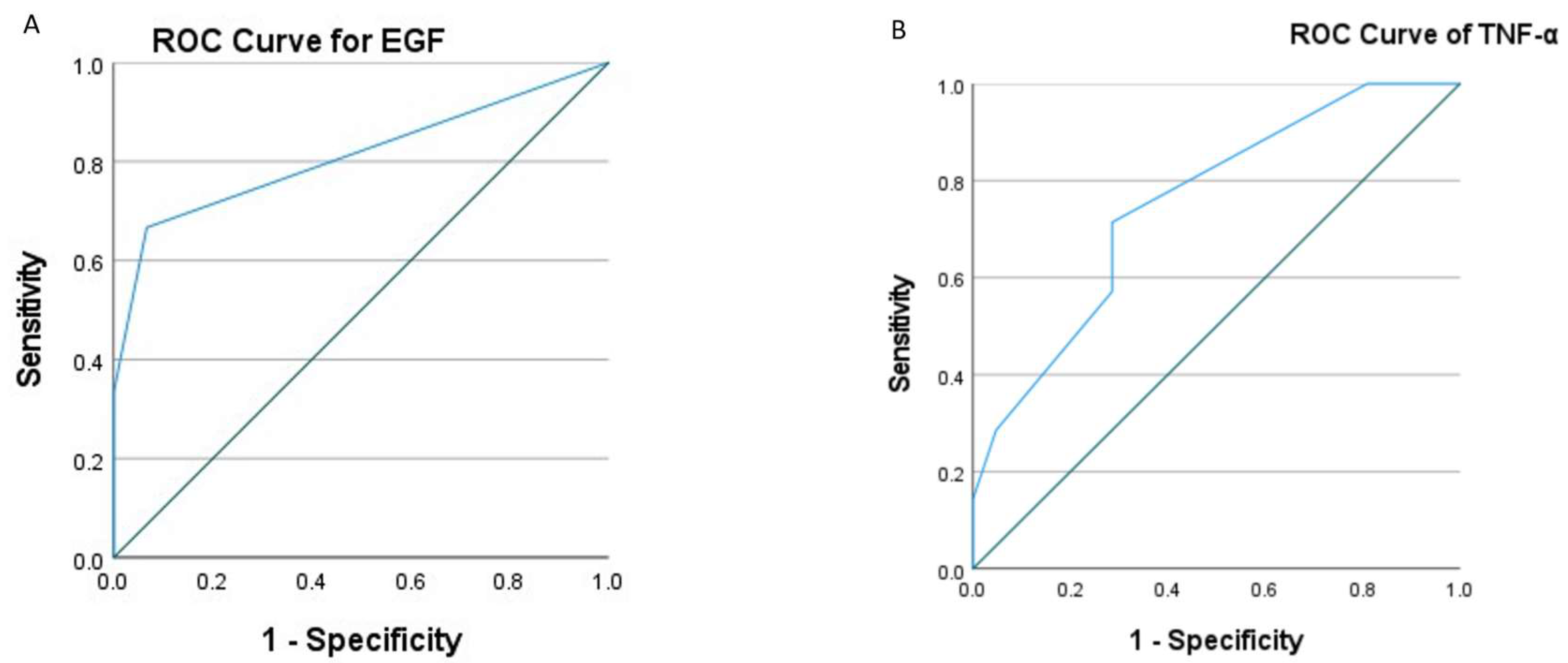

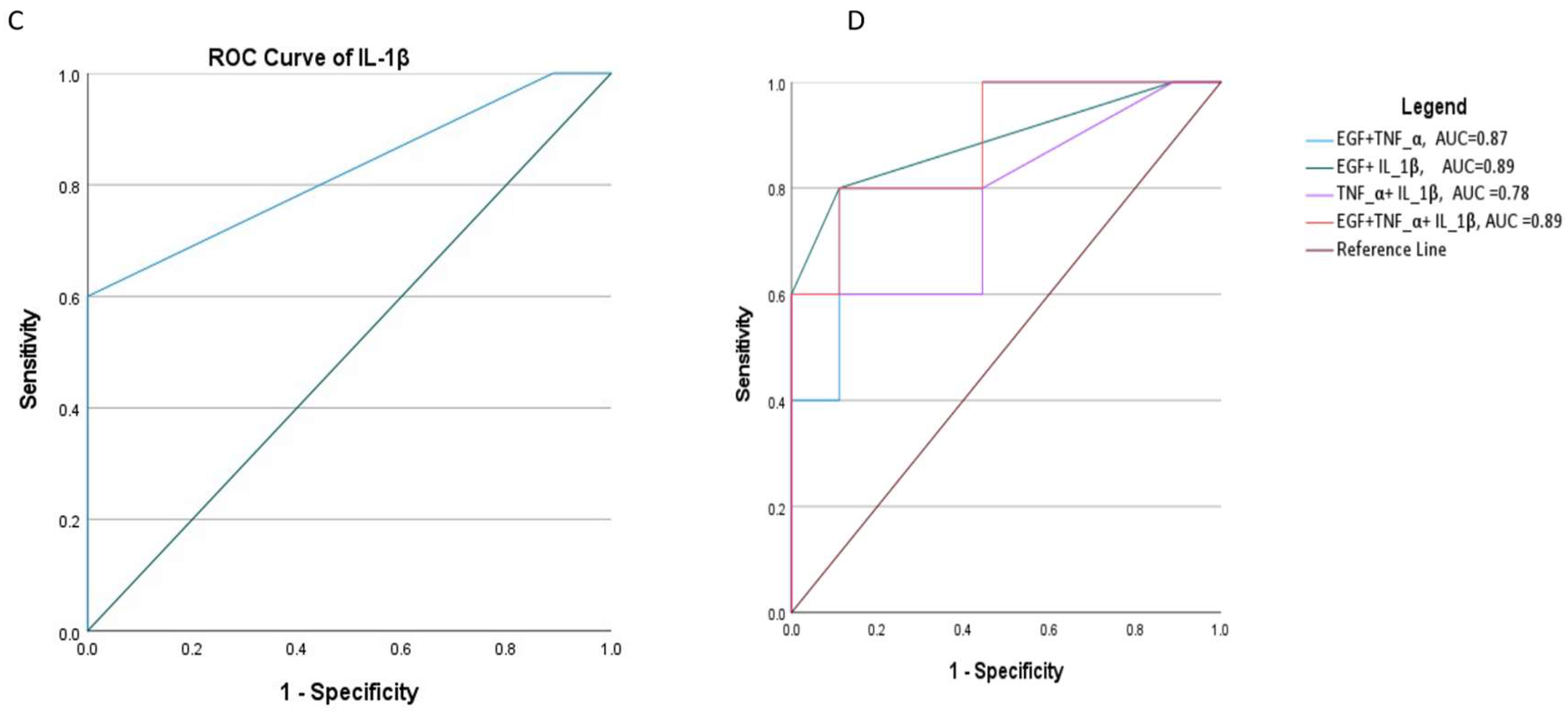

Background: The primary cause of cervical cancer is the high-risk human papillomavirus (hrHPV); the infection patterns may vary depending on the state of the vaginal immune system. Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) such as gonorrhea, trichomoniasis, and chlamydia can alter the local immune response, which in turn may affect the persistence and progression rate of hrHPV infections. The objective of this study was to compare cytokine levels from vaginal specimens collected from hrHPV positive, STI positive, and healthy controls, and to explore correlations with clinical parameters. Methods: Vaginal samples were collected from women diagnosed with hrHPV, asymptomatic STIs, and healthy controls. HrHPV and STIs status were confirmed through multiplex real time PCR. Vaginal cytokines and various growth factors were analyzed by Invitrogen ProcartaPlex™ Multiplex Immunoassay. Statistical analyses were performed to compare cytokine levels across different groups and to explore correlations with clinical parameters. Results: Women having STIs and hrHPV coinfection(n=26) had increased median concentration levels of Eotaxin (P=0.04), IL-2 (P=0.01), IL-10 (P=0.02), and IP-10 (P=0.04) compared to the control groups(n=22). Asymptomatic women with STIs (n=16) exhibited a distinct cytokine profile characterized by elevated levels of IL-2 (P=0.02) compared with control groups. Women with hrHPV(n=16) had lower levels of IL-15 (P=0.02) compared to controls. The median concentration levels of TNF-α (P=0.04), IL-1β (P=0.02), and EGF (P=0.01) were significantly greater in ≥CIN2+(n=8) than ≤CIN1(n=25). The area under the curve (AUC) of EGF, IL-1β, and the combination of EGF+IL-1β +TNF-α was good predictor for high-grade cervical lesions. Conclusion: The cytokine profiling revealed significant alterations in the vaginal immune environment in women with asymptomatic STIs and co-infection with hrHPV. The findings suggest that an inflammatory response in hrHPV infection may be modulated by co-existing STIs, potentially influencing disease progression. Elevated levels of EGF, IL-1β, and TNF-α in vaginal swabs suggest an inflammatory and proliferative environment that can contribute to the development and progression of cervical dysplasia.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Study Setting and Study Population

2.2. Data Collection and Laboratory Procedures

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Result

3.1. Characteristics of the Study Population

3.2. Expression Levels of Cytokines

3.3. Cytokine Expression in Women Live with HIV, and HIV+HPV

3.4. Cytokine Concentration in hrHPV, STI, hrHPV and STI Coinfection, and Controls

3.5. Cytokine Concentration in NILM/CIN1 and CIN2+ and Cervical Cancer

3.6. Cytokine Score Effectiveness in Diagnosing Advanced Cervical Lesions

Discussion

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Availability of data and material

Acknowledgments

Abbreviations

| 5PL | Five parameter logistic algorism |

| AUC | Area under curve |

| CIN1 | Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia 1 |

| CIN2+ | Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia 2 or 3 |

| HrHPV | High-risk human Papillomavirus |

| ICC | Invasive cervical cancer |

| NILM | Negative for Intraepithelial Lesion or Malignancy |

| PCR | Polymerase chain rection |

| PID | Pelvic inflammatory disease |

| ROC | Receiver operator characteristic |

| STIs | Sexually transmitted infections |

References

- Martinelli M, Musumeci R, Sechi I, Sotgiu G, Piana A, Perdoni F, et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus (HPV) and other sexually transmitted infections (STIS) among italian women referred for a colposcopy. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(24).

- WHO. Sexually transmitted infections (STIs);Key facts. 2024; Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/sexually-transmitted-infections-(stis).

- Castle PE, Giuliano AR. Chapter 4: Genital tract infections, cervical inflammation, and antioxidant nutrients--assessing their roles as human papillomavirus cofactors. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr [Internet]. 2003 Jun 1;2003(31):29–34. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/jncimono/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/oxfordjournals.jncimonographs.a003478.

- Duque GA, Descoteaux A. Macrophage cytokines: Involvement in immunity and infectious diseases. Front Immunol. 2014;5(OCT):1–12.

- Liu C, Chu D, Kalantar-Zadeh K, George J, Young HA, Liu G. Cytokines: From Clinical Significance to Quantification. Adv Sci. 2021;8(15).

- Masson L, Barnabas S, Deese J, Lennard K, Dabee S, Gamieldien H, et al. Inflammatory cytokine biomarkers of asymptomatic sexually transmitted infections and vaginal dysbiosis: A multicentre validation study. Sex Transm Infect. 2019;95(1):5–12.

- ter Horst R, Jaeger M, Smeekens SP, Oosting M, Swertz MA, Li Y, et al. Host and Environmental Factors Influencing Individual Human Cytokine Responses. Cell. 2016;167(4):1111-1124.e13.

- Vidal AC, Skaar D, Maguire R, Dodor S, Musselwhite LW, Bartlett JA, et al. IL-10, IL-15, IL-17, and GMCSF levels in cervical cancer tissue of Tanzanian women infected with HPV16/18 vs. non-HPV16/18 genotypes Clinical oncology. Infect Agent Cancer. 2015;10(1):1–7.

- Hibma, MH. The Immune Response to Papillomavirus During Infection Persistence and Regression. Open Virol J. 2013;6(1):241–8.

- Arnold KB, Burgener A, Birse K, Romas L, Dunphy LJ, Shahabi K, et al. Increased levels of inflammatory cytokines in the female reproductive tract are associated with altered expression of proteases, mucosal barrier proteins, and an influx of HIV-susceptible target cells. Mucosal Immunol [Internet]. 2016;9(1):194–205. [CrossRef]

- Mwatelah R, McKinnon LR, Baxter C, Abdool Karim Q, Abdool Karim SS. Mechanisms of sexually transmitted infection-induced inflammation in women: implications for HIV risk. J Int AIDS Soc. 2019;22(S6):32–9.

- Buder S, Schöfer H, Meyer T, Bremer V, Kohl PK, Skaletz-Rorowski A, et al. Bacterial sexually transmitted infections. JDDG - J Ger Soc Dermatology. 2019;17(3):287–315.

- Arnold KB, Burgener A, Birse K, Romas L, Dunphy LJ, Shahabi K, et al. Increased levels of inflammatory cytokines in the female reproductive tract are associated with altered expression of proteases, mucosal barrier proteins, and an influx of HIV-susceptible target cells. Mucosal Immunol [Internet]. 2016;9(1):194–205. [CrossRef]

- Thermo Fisher Scientific. ProcartaPlex TM Multiplex Immunoassay Multiplex immunoassays using magnetic bead technology for. 2022;0(41).

- Alcaide ML, Rodriguez VJ, Brown MR, Pallikkuth S, Arheart K, Martinez O, et al. High Levels of Inflammatory Cytokines in the Reproductive Tract of Women with BV and Engaging in Intravaginal Douching: A Cross-Sectional Study of Participants in the Women Interagency HIV Study. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2017;33(4):309–17.

- Perera PY, Lichy JH, Waldmann TA, Perera LP. The role of interleukin-15 in inflammation and immune responses to infection: Implications for its therapeutic use. Microbes Infect [Internet]. 2012;14(3):247–61. [CrossRef]

- Torres-Poveda K, Bahena-Román M, Delgado-Romero K, Madrid-Marina V. A prospective cohort study to evaluate immunosuppressive cytokines as predictors of viral persistence and progression to pre-malignant lesion in the cervix in women infected with HR-HPV: Study protocol. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):1–9.

- Sasagawa T, Takagi H, Makinoda S. Immune responses against human papillomavirus (HPV) infection and evasion of host defense in cervical cancer. J Infect Chemother. 2012;18(6):807–15.

- Adapen C, Réot L, Menu E. Role of the human vaginal microbiota in the regulation of inflammation and sexually transmitted infection acquisition: Contribution of the non-human primate model to a better understanding? Front Reprod Heal. 2022;4(December):1–19.

- Folci M, Ramponi G, Arcari I, Zumbo A, Brunetta E. Eosinophils as Major Player in Type 2 Inflammation: Autoimmunity and Beyond. In 2021. p. 197–219. Available from: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/5584_2021_640.

- Lugo LZA, Puga MAM, Jacob CMB, Padovani CTJ, Nocetti MC, Tupiná MS, et al. Cytokine profiling of samples positive for Chlamydia trachomatis and Human papillomavirus. PLoS One. 2023;18(3 March):1–15.

- Buckner LR, Lewis ME, Greene SJ, Foster TP, Quayle AJ. Chlamydia trachomatis infection results in a modest pro-inflammatory cytokine response and a decrease in T cell chemokine secretion in human polarized endocervical epithelial cells. Cytokine. 2013;63(2):151–65.

- Schindler S, Magalhães RA, Costa ELF, Brites C. Genital Cytokines in HIV/Human Papillomavirus Co-Infection: A Systematic Review. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses [Internet]. 2022 Sep 1;38(9):683–91. Available from: https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/aid.2021.0139.

- Cai Y, Zhai J, Wu Y, Chen R, Tian X. The Role of IL-2, IL-4, IL-10 and IFN-γ Cytokines Expression in the Microenvironment of Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia. Adv Reprod Sci. 2022;10(04):106–14.

- Spolski R, Li P, Leonard WJ. Biology and regulation of IL-2: from molecular mechanisms to human therapy. Nat Rev Immunol [Internet]. 2018;18(10):648–59. [CrossRef]

- Syrjänen S, Naud P, Sarian L, Derchain S, Roteli-Martins C, Longatto-Filho A, et al. Immunosuppressive cytokine Interleukin-10 (IL-10) is up-regulated in high-grade CIN but not associated with high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) at baseline, outcomes of HR-HPV infections or incident CIN in the LAMS cohort. Virchows Arch. 2009;455(6):505–15.

- Scott ME, Ma Y, Kuzmich L, Mescicki AB. Diminished IFN-γ and IL-10 and elevated Foxp3 mRNA expression in the cervix are associated with CIN 2 or 3. Int J Cancer. 2009;124(6):1379–83.

- WANG Y, LIU X-H, LI Y-H, LI O. The paradox of IL-10-mediated modulation in cervical cancer. Biomed Reports. 2013;1(3):347–51.

- Liu M, Guo S, Hibbert JM, Jain V, Singh N, Wilson NO, et al. CXCL10/IP-10 in infectious diseases pathogenesis and potential therapeutic implications. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev [Internet]. 2011;22(3):121–30. [CrossRef]

- Yang L, Chen P, Luo S, Li J, Liu K, Hu H, et al. CXC-chemokine-ligand-10 gene therapy efficiently inhibits the growth of cervical carcinoma on the basis of its anti-angiogenic and antiviral activity. Biotechnol Appl Biochem [Internet]. 2009 Jul 23;53(3):209–16. Available from: https://iubmb.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1042/BA20090012.

- Sato E, Fujimoto J, Toyoki H, Sakaguchi H, Alam SM, Jahan I, et al. Expression of IP-10 related to angiogenesis in uterine cervical cancers. Br J Cancer. 2007;96(11):1735–9.

- Lin W, Niu Z, Zhang H, Kong Y, Wang Z, Yang X, et al. Imbalance of Th1/Th2 and Th17/Treg during the development of uterine cervical cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol [Internet]. 2019;12(9):3604–12. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31934210%0Ahttp://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=PMC6949808.

- Vitkauskaite A, Urboniene D, Celiesiute J, Jariene K, Skrodeniene E, Nadisauskiene RJ, et al. Circulating inflammatory markers in cervical cancer patients and healthy controls. J Immunotoxicol [Internet]. 2020;17(1):105–9. [CrossRef]

- Ali KS, Ali HYM, Jubrael JMS. Concentration levels of IL-10 and TNFα cytokines in patients with human papilloma virus (HPV) DNA+ and DNA- cervical lesions. J Immunotoxicol. 2012;9(2):168–72.

- Kobayashi A, Weinberg V, Darragh T, Smith-McCune K. Evolving immunosuppressive microenvironment during human cervical carcinogenesis. Mucosal Immunol [Internet]. 2008;1(5):412–20. [CrossRef]

- Song D, Li H, Li H, Dai J. Effect of human papillomavirus infection on the immune system and its role in the course of cervical cancer (Review). Oncol Lett. 2015;10(2):600–6.

- Fernandes APM, Gonçalves MAG, Duarte G, Cunha FQ, Simões RT, Donadi EA. HPV16, HPV18, and HIV infection may influence cervical cytokine intralesional levels. Virology. 2005;334(2):294–8.

- Bukowski A, Hoyo C, Vielot NA, Graff M, Kosorok MR, Brewster WR, et al. Epigenome-wide methylation and progression to high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN2+): a prospective cohort study in the United States. BMC Cancer [Internet]. 2023;23(1):1–14. [CrossRef]

- Akoto C, Norris SA, Hemelaar J. Maternal HIV infection is associated with distinct systemic cytokine profiles throughout pregnancy in South African women. Sci Rep [Internet]. 2021;1–15. [CrossRef]

- Bebell LM, Passmore JA, Williamson C, Mlisana K, Iriogbe I, Van Loggerenberg F, et al. Relationship between levels of inflammatory cytokines in the genital tract and CD4+ cell counts in women with acute HIV-1 infection. J Infect Dis. 2008;198(5):710–4.

- Guimarães MVMIB, Michelin MA, Lucena AADS, Lodi CTDC, Lima MIDM, Murta EFC, et al. Cytokine expression in the cervical stroma of HIV-positive and HIV-negative women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Viral Immunol. 2014;27(7):350–5.

- Schindler S, Netto E, Deminco F, Figueiredo CA, de Andrade CM, Alves AR, et al. Detection of cytokines in cervicovaginal lavage in HIV-infected women and its association with high-risk human papillomavirus. Front Immunol. 2024;15(June):1–7.

| Variable | Responses | Count | Percent |

| Median age in years | 32 | ||

| Age group in years | < 30 | 31 | 38.8 |

| ≥30 | 49 | 61.2 | |

| High-risk Human papillomavirus (hrHPV)§ | Positive | 42 | 52.5 |

| Negative | 38 | 47.5 | |

| Histology result (n=33) | NILM or CIN1 | 25 | 75.8 |

| CIN2+ and cervical cancer | 8 | 24.2 | |

| Sexually transmitted infections (STI)|* | Positive | 42 | 52.5 |

| Negative | 38 | 47.5 | |

| HIV serostatus | Positive | 10 | 12.5 |

| Negative | 70 | 87.5 | |

| Infection Status of Participants | HPV only | 16 | 20 |

| STIs only | 16 | 20 | |

| Co-infection | 26 | 32.5 | |

| Health controls | 22 | 27.5 | |

| Cytokines | Number of samples expressed n (%) | IQR(Q3-Q1) | Median | Mean ±SE |

| BDNF | 2(3) | 0.72-4.72 | 2.72 | 2.7±2.0 |

| EGF | 52(65) | 24.25-24.25 | 24.25 | 35.7±4.78 |

| Eotaxin (CCL11) | 80(100) | 2.68-3.96 | 2.68 | 3.4±0.18 |

| FGF-2 | 2(3) | 13.59-50.04 | 31.82 | 31.8±18.23 |

| GM-CSF | 20(25) | 42.95-42.95 | 42.95 | 49.8±4.60 |

| GRO alpha (CXCL1) | 2(3) | 8.17-31.12 | 19.65 | 19.7±11.48 |

| HGF | 80(100) | 19.21-31.32 | 19.21 | 26.2±1.76 |

| IFN alpha | 11(14) | 0.61-0.97 | 0.61 | 1.03±0.25 |

| IFN gamma | 25(31) | 3.78-3.78 | 3.78 | 4.69±0.61 |

| IL-1 alpha | 2(3) | 0.23-0.62 | 0.425 | 0.43±0.20 |

| IL-1 beta | 31(39) | 10.3-18.4 | 10.3 | 14.2±1.67 |

| IL-1RA | 68(85) | 144.2-362.1 | 144.2 | 259±38.98 |

| IL-2 | 78(98) | 23.0-33.69 | 32.66 | 32.2±0.93 |

| IL-4 | 80(100) | 8.36-10.73 | 8.36 | 8.83±0.31 |

| IL-5 | 1(1) | 15.35-15.35 | 15.35 | 15.4±0 |

| IL-6 | 1(1) | 26.3-26.3 | 26.3 | 26.3±0 |

| IL-7 | 11(14) | 1.07-2.18 | 1.64 | 1.62±0.20 |

| IL-8 (CXCL8) | 1(1) | 79.97-79.97 | 79.97 | 80±0 |

| IL-9 | 1(1) | 36.78-36.78 | 36.78 | 36.8±0 |

| IL-10 | 79(99) | 1.47-2.18 | 1.47 | 1.89±0.12 |

| IL-12p70 | 80(100) | 2.45-3.283 | 2.45 | 2.70±0.13 |

| IL-13 | 69(86) | 8.62-15.21 | 8.62 | 11.6±0.92 |

| IL-15 | 70(88) | 3.39-6.19 | 3.39 | 5.69±0.61 |

| IL-17A (CTLA-8) | 80(100) | 4.94-6.96 | 4.94 | 6.14±0.34 |

| IL-18 | 6(8) | 14.37-33.73 | 20.22 | 25.3±6.70 |

| IL-21 | 1(1) | 9.48-9.48 | 9.48 | 9.48±0 |

| IL-22 | 6(8) | 5.21-14.63 | 5.21 | 11.5±6.28 |

| IL-23 | 1(1) | 138.4-138.4 | 138.4 | 138±0 |

| IL-27 | 76(95) | 23.69-49.88 | 49.88 | 43.6±3.19 |

| IL-31 | 1(1) | 117.3-117.3 | 117.3 | 117±0 |

| IP-10 (CXCL10) | 67(84) | 4.75-6.61 | 4.75 | 6.29±0.52 |

| LIF | 80(100) | 6.76-8.47 | 6.76 | 8.11±0.42 |

| MCP-1 (CCL2) | 44(55) | 6.4-7.585 | 6.4 | 8.65±1.26 |

| MIP-1 alpha (CCL3) | 3(4) | 1.01-3.96 | 2.12 | 2.36±0.86 |

| MIP-1 beta (CCL4) | 2(3) | 10.77-56.66 | 33.72 | 33.7±22.95 |

| NGF beta | 3(4) | 1.51-3.97 | 2.78 | 2.75±0.71 |

| PDGF-BB | 2(3) | 8.08-15.02 | 11.55 | 11.6±3.47 |

| PlGF-1 | 0(0) | |||

| RANTES (CCL5) | 1(1) | 1.59-1.59 | 1.59 | 1.59±0 |

| SCF | 73(91) | 0.66-1.26 | 0.66 | 1.07±0.10 |

| SDF-1 alpha | 1(1) | 113.9-113.9 | 113.9 | 114±0 |

| TNF alpha | 79(99) | 20.12-26.19 | 20.12 | 23.2±1.0 |

| TNF beta | 0(0) | |||

| VEGF-A | 66(83) | 4.52-7.53 | 6.06 | 77.4±67.99 |

| VEGF-D | 0(0) |

| Cytokine classification | Cytokines | Median (IQR) (pg/ml) | |||

| Groups | |||||

| Controls | HrHPV | STI | Co-infection | ||

| Chemokines | MCP-1 | 6.4(6.4-6.4) | 6.4(4.4-33.4) | 6.4(6.4-8.6) | 6.4(6.4-9.0) |

| P value | - | >0.99 | >0.99 | >0.99 | |

| IP-10 | 4.8 (4.8-5.5) | 4.8(2.4-4.8) | 4.8(4.8-6.6) | 5.7(4.8-7.8) | |

| P value | - | >0.99 | >0.99 | 0.04* | |

| Eotaxin | 2.7(2.7-3) | 2.7(2.7-3) | 3.9 (2.7-5.0) | 4.0 (4.0-5.0) | |

| P value | - | >0.99 | 0.61 | 0.04* | |

| Growth factors | GM-CSF | 43(43-43) | 43(43-43) | 53.1 (43-63.3) | 43(43-63.3) |

| P value | - | >0.99 | 0.35 | 0.20 | |

| HGF | 19.2(19.2-31.3) | 19.2(19.2-31.3) | 19.2(19.2-42.9) | 19.2(31.3-31.3) | |

| P value | - | >0.99 | >0.99 | >0.99 | |

| EGF | 24.3(24.3-39.1) | 24.3(24.3-24.3) | 24.3(24.3-41.4) | 24.3(24.3-47.2) | |

| P value | - | 0.79 | >0.99 | >0.99 | |

| SCF | 0.7(0.7-1.26 | 0.7(0.7-1.1) | 1.3(0.7-1.3) | 1.3(0.7-1.5) | |

| P value | - | >0.99 | 0.33 | 0.056 | |

| VEGF-A | 6.1(4.1-7.5) | 6.1(0.0-6.1) | 4.5(2.9-6.8) | 6.1(2.9-9.3) | |

| P value | - | >0.99 | >0.99 | 0.50 | |

| Interferons | INF-γ | 3.8(3.8-8.1) | 3.8(3.8-3.8) | 3.8(3.8-3.8) | 3.8(2.9-5.3) |

| P value | - | >0.99 | >0.99 | >0.99 | |

| Anti-Inflammatory or Immunoregulatory Cytokines | IL-10 | 1.5(1.5-2.2) | 1.5(1.5-1.8) | 1.5(1.5-2.0) | 2.2(1.5-2.9) |

| P value | - | 0.93 | >0.99 | 0.02* | |

| IL-1RA | 144(144-144) | 144(144.2-199) | 144(144-144.2) | 144(306-362.1) | |

| P value | - | >0.99 | >0.99 | 0.25 | |

| T-Cell Differentiation Cytokines | IL-2 | 33(23-33) | 33(23-33) | 33(23-41) | 33(33-41) |

| P value | - | >0.99 | 0.02* | 0.01* | |

| IL-4 | 8.4(8.4-9) | 8.4(6-11) | 8.4(7.4-10.7) | 8.4(8.4-13) | |

| P value | - | 0.94 | 0.99 | 0.56 | |

| IL-13 | 8.6(8.6-14) | 8.6(8.6-10.3) | 8.6(8.6-15.2) | 8.6(8.6-15.2) | |

| P value | - | >0.99 | >0.99 | >0.99 | |

| IL-17A | 4.9(4.9-5.5) | 4.9(3.3-4.9) | 6.0(4.9-8.4) | 5.5(4.9-7.4) | |

| P value | - | 0.73 | 0.19 | 0.11 | |

| Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines | IL-1β | 10.3(10.3-10.3) | 8.0(5.7-10.3) | 14.5(10.3-25.9) | 10.3(10.3-18.4) |

| P value | - | 0.95 | 0.22 | 0.61 | |

| TNF-α | 20.1(18.6-26.2) | 20.1(13.5-25.5) | 20.1(20.1-26.2) | 26.2(20.1-27.6) | |

| P value | - | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.08 | |

| Other Cytokines |

IL-12P70 | 2.5(2.5-2.5) | 2.5(1.5-2.5) | 2.5(2.5-3.4) | 2.5(2.5-3.6) |

| P value | - | 0.83 | >0.99 | 0.24 | |

| IL-15 | 6.2 (3.4-6.2) | 3.4(3.4-3.4) | 3.4(3.4-8.7) | 6.2(3.4-6.2) | |

| P value | - | 0.02* | >0.99 | >0.99 | |

| IL-27 | 23.7(23.7-49.9) | 23.7(23.7-43.3) | 23.7(49.9-49.9) | 23.7(49.9-55.6) | |

| P value | - | 0.83 | >0.99 | 0.22 | |

| LIF | 6.8(6.8-8.5) | 6.8 (5.1-8.5) | 6.8(5.4-8.5) | 8.5(6.8-10) | |

| - | >0.99 | >0.99 | 0.46 | ||

| S. No | Cytokines | Median (IQR) in pg/ml | P value | |

| ≤CIN1 | ≥CIN2+ | |||

| 1 | EGF | 24(24-24) | 47(24-125) | 0.01* |

| 2 | Eotaxin | 2.7(2.7-4.0) | 3.3(2.7-5.0) | 0.14 |

| 3 | GM-CSF | 43(43-43) | 43(43-130) | 0.33 |

| 4 | HGF | 19(19-31) | 19(19-40) | 0.90 |

| 5 | INF-γ | 3.8(2.1-4.5) | 3.8(3.8-14) | 0.27 |

| 6 | IL-1β | 10(10-10) | 14(10-36) | 0.02* |

| 7 | IL-1RA | 144(144-362) | 362(144-2037) | 0.99 |

| 8 | IL-2 | 33(23-31) | 37(33-41) | 0.06 |

| 9 | IL-4 | 8.4(5.8-11) | 9.0(6.4-12) | 0.47 |

| 10 | IL-10 | 1.7(1.5-2.2) | 2.2(1.6-2.4) | 0.28 |

| 11 | IL-12p70 | 2.5(1.9-3.4) | 2.5(2.5-4.3) | 0.27 |

| 12 | IL-13 | 8.6(8.6-10) | 8.6(8.6-14) | 0.56 |

| 13 | IL-15 | 3.4(3.4-6.2) | 3.4(3.4-35) | 0.56 |

| 14 | IL-17A | 4.9(4.9-7) | 4.9(4.9-8.4) | 0.55 |

| 15 | IL-27 | 50(24-50) | 37(24-73) | 0.61 |

| 16 | IP-10 | 4.8(4.8-6.6) | 5.7(4.8-7.8) | 0.47 |

| 17 | LIF | 6.8(6.8-8.5) | 8.5(6.8-9.7) | 0.46 |

| 18 | MCP-1 | 6.4(6.4-6.4) | 9.3(6.4-13) | 0.10 |

| 19 | SCF | 0.97(0.66-1.3) | 0.66(0.66-2.2) | 0.97 |

| 20 | TNF-α | 20(20-26) | 26(21-30) | 0.04* |

| 21 | VEGF-A | 6.1(4.5-7.5) | 7.5(6.1-36) | 0.12 |

| Cytokines | AUC(95%CI) | P value |

| EGF | 0.81(0.57-1.0) | 0.029 |

| TNF-α | 0.75(0.56-0.96) | 0.05 |

| IL-1β | 0.82(0.56-1.0) | 0.053 |

| EGF +TNF-α | 0.87(0.67-1.0) | 0.028 |

| EGF +IL-1β | 0.89(0.68-1.0) | 0.02 |

| TNF-α + IL-1β | 0.78(0.49-1.0) | 0.096 |

| EGF +TNF-α + IL-1β | 0.89(0.70-1.0) | 0.02 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).