1. Introduction

Cervical cancer (CC) represents the second most prevalent oncological disease among women worldwide, with a significant impact on quality of life and economic costs. In Spain, estimates for 2023 indicates 2047 women are diagnosed with CC and 664 deaths are attributed to this disease [

1]. Nevertheless, there is substantial scientific evidence that preventive measures against CC can be both feasible and effective. Firstly, although not typically fatal, the disease predominantly affects young, sexually active women. Secondly, it is associated with modifiable environmental risk factors. Thirdly, it is frequently preceded by progressive cell dysplasia. Finally, the cervix is easily accessible for diagnostic procedures, specimen collection and indirect observation.

In relation to the aforementioned environmental risk factors, a number of microorganisms have been identified as contributing to the development of alterations and malignancy that lead to CC by altering the cellular environment [

2]. However, the Spanish CC screening programme, apart from smear tests, only include high-risk human papillomavirus (HR-HPV) detection [

3,

4,

5], despite the fact that HPV infections are encountered by over 80% of women during their lifetime, with less than 2% developing CC [

6] and the majority of infections being cleared by the host [

7,

8].

In fact, the risk of developing CC and/or cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) as well as the incidence and persistence of HR-HPV and other sexually transmitted infections (STI-O), have been found to be increased in the presence of vaginal dysbiosis and vaginosis (symptomatic vaginal dysbiosis) [

9,

10,

11]. Conversely, the absence of STI-O in addition to HR-HPV is associated with a reduced likelihood of histological abnormalities. Furthermore, certain microorganisms have been found associated with the appearance of CIN even with a higher OR for CC than HR-HPV. This is exemplified by

Chlamydia trachomatis (CT), the most prevalent STI in western countries: its coinfection with HR-HPV increases the OR for high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HGSIL) and CC even further [

10,

12]. Indeed, screening for CT is recommended in sexually active women under 25 years of age and in sexually active women over 25 years old when at increased risk [

13].

Besides, in addition to CC, STIs can lead to significant complications, including infertility and chronic pain; therefore, it is of the utmost importance that diagnosis and treatment be promptly initiated in order to ensure optimal medical care. The greatest risk factor for an STI is a previous diagnosis of another STI. This is due in part to the fact that the subsequent oxidative stress and/or chronic inflammation serves as a facilitator for new pathogens to exert damage, thereby increasing the risk of co-infections, chronic infections and further disorders. Despite the focus on HR-HPV infection has been linked to its role in the development of CC, it is crucial to recognise that HPV is the most frequent STI worldwide and should be treated as such. This entails assessing for co-infection, establishing a window of opportunity for treatment and promoting HPV clearance.

There is considerable variation in the prevalence of STIs-O between countries, however, it is higher in women who are HR-HPV-positive, hence, numerous studies have emphasised the necessity for routine screening and monitoring of HR-HPV coinfection with STIs-O [

14,

15,

16,

17], aligning with the viewpoint that this approach is cost-effective when the rate of co-infection exceeds 3% [

18]. In this regard, it is well documented that the prevalence of CT exceeds 3% in women up to 40 years of age in other countries [

19]. However, the presence of HR-HPV and STIs-O, as well as the rates of co-infection, remain insufficiently documented in our setting. Furthermore, a unifying criterion is currently being established at the national level to provide a standardised guideline for CC prevention programmes, which have previously been implemented at the discretion of each Autonomous Community [

3,

20]. Consequently, new local insights are essential to inform public health guidelines regarding screening, diagnosis and treatment of HR-HPV infection and STIs-O, with the aim of reducing their contribution to the burden of disease.

Therefore, the present study aims to determine the presence of the major STIs (Chlamydia trachomatis (CT), Trichomonas vaginalis (TV), Neisseria gonorrhoeae (NG), and Mycoplasma genitalium (MG)) and the rate of co-infection with HR-HPV in women previously diagnosed with HR-HPV infection in a Spanish setting.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Setting and Design

A prospective cross-sectional observational study was conducted in the Miguel Servet University Hospital, a Spanish tertiary care hospital located in Zaragoza, which serves a total catchment area of over 400,000 people. Samples were collected from February 2024 to November 2024.

2.2. Participants and Sample Collection

All women attending the hospital’s Gynaecology Department for the CC screening programme, who met the above eligibility criteria and signed the informed consent form, were recruited to participate in the study. The following inclusion criteria were applied: participants had to be followed up for HR-HPV infection detected in the last year, and be aged between 18 and 65 years old. As exclusion criteria, participants had to have no history of CC, and they could not have been treated for an STI-O or enrolled in a HPV vaccine study in the previous year.

Their endocervical specimens were collected by a trained gynaecologist, and preserved in transport medium (PreservCyt® solution, Hologic, MA, USA) for transfer to the laboratory on the same day. They were stored at room temperature until the next day, when they were analysed in accordance with the routine procedure.

2.3. Laboratory testing, Outcomes of Interest

The samples were processed at the hospital microbiology laboratory for the detection of HR-HPV, and those with a positive result were subjected to further analysis to determine the presence of CT, NG, MG and TV. All analyses were conducted using real-time PCR (polymerase chain reaction) on the cobas® 5800 System with the use of cobas® HPV, cobas® CT/NG and cobas® TV/MG reagents (Roche Diagnostics, IN, USA).

The results were classified in accordance with the manufacturer’s specifications as either negative or positive. In cases where the initial classification was inconclusive, a second test was conducted to provide further clarification. In instances where uncertainty persisted, a new sample from the participant was analysed.

The results obtained from the cobas® 5800 System software regarding the HR-HPV, CT, NG, TC and MG tests, were exported as a tab-separated values file from the instrument and converted into a spreadsheet for analysis. The designated investigator extracted the results for data storage and analysis, and the age of each participant at the time of sample collection was added as an additional outcome of interest.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

A descriptive analysis of the clinical results was conducted. The rates of STIs co-infection were determined by calculating the ratio of the total number of cases to the number of positive results. Further analysis of the data were conducted using descriptive and inferential statistics. Categorical variables were presented as absolute and relative frequencies (n, %) and age as median and interquartile range. Group-wise comparisons by age were performed using Student’s t-test or Chi-square (χ2). A two-tailed p value was considered statistically significant when p ≤ 0.05. All analyses and graphs were conducted using the open-source software Jamovi 2.2.5 (The Jamovi Project, Australia), MS Excel 2016 (Microsoft, WA, USA), MS PowerPoint 2016 (Microsoft, WA, USA) and MS Word 2016 (Microsoft, WA, USA).

2.5. Ethics

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent modifications. Prior to sample collection, all participants provided written informed consent. The protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Aragon and by the hospital management.

3. Results

A total of 254 women were selected for the present analysis, with a median age of 40.5 years (interquartile range 35.0-8.0).

Table 1 shows the overall infection rates, which were 38.6% for HR-HPV and 4.3% for ITSs-O (3.8% in HR-HPV-negative women and 5.1% in HR-HPV-positive women). Additionally, ITSs-O rates were shown according to age group. A higher rate of ITSs-O was found among women under 35 years of age with a HR-HPV positive result, in comparison to those with a negative HR-HPV result (20.0% vs 4.2%). Furthermore, in this age group, the odds ratio for an ITS-O positive result in HR-HPV positive women was 5.2 when compared to HR-HPV negative women (p=0.05). In the case of eldest women, non STIs were found up to 48 years of age (the positive ITS results found in those HR-HPV-negative women over the age of 45 belong to women aged between 47 and 48).

Supplementary Figure S1 illustrates the distribution of age according to the HR-HPV and ITS-O results. The distribution of the age differs significantly according to the ITS-O result in both HR-HPV positive and negative women. No older women from 55 to 64 year tested positive for ITS-O (independently of HR-HPV result), and only two (33%) women between 45 and 54 years tested positive for ITS-O among those with a negative HR-HPV result.

Supplementary Figure S2 depicts the values for age according to the presence or absence of each ITS. The age of women with a positive result for MG was found to be lower (31.0 (interquartile range 29.5-32.5) than that of women with a negative result (41.0 (interquartile range 35.0-48.0)). Conversely, the age of women with a positive result for overall HR-HPV was higher (39.5 (interquartile range 33.0-47.3) than that of women with a negative result (42.0 (interquartile range 37.0-48.8)). Both p values ≤ 0.05.

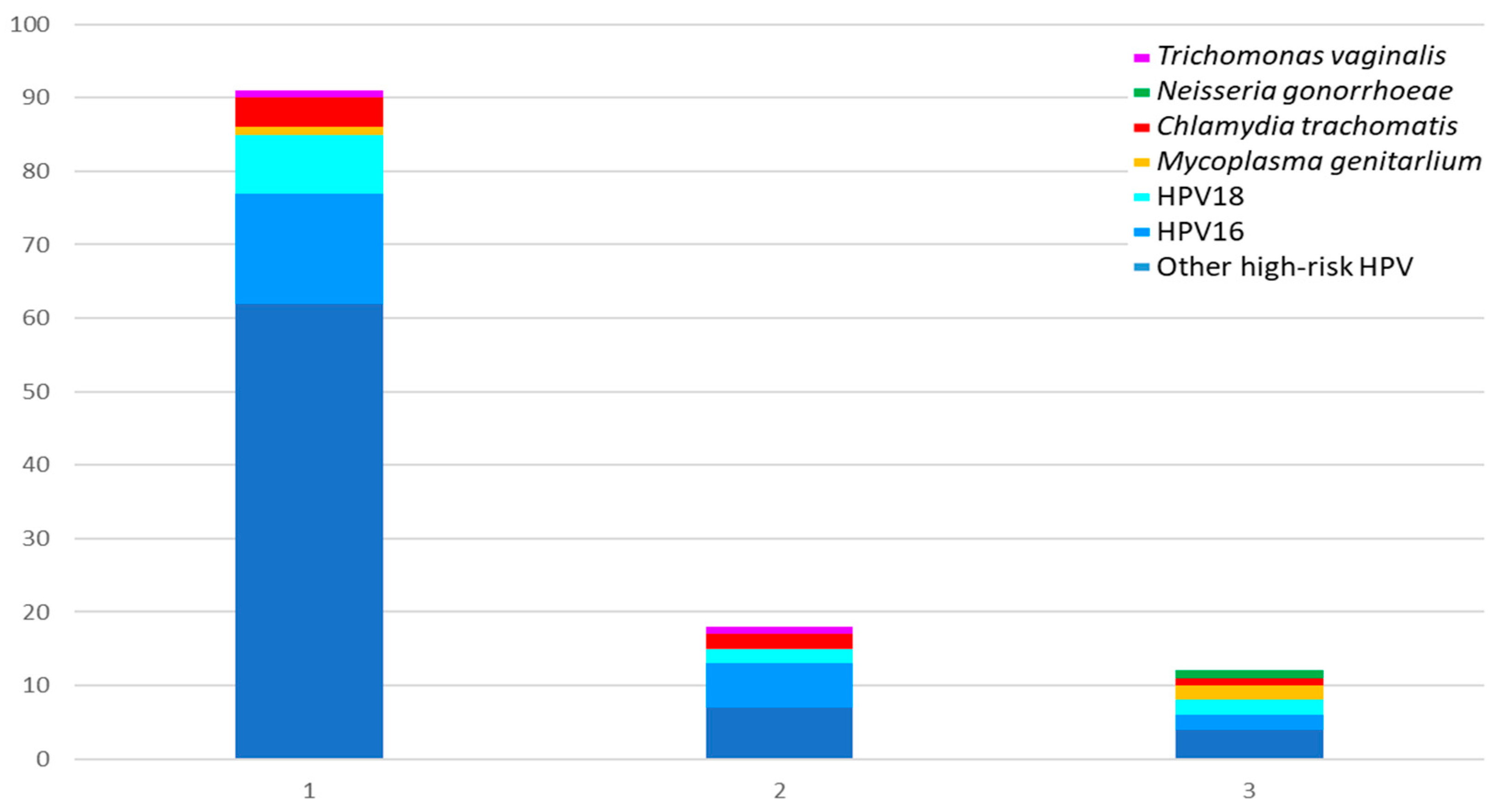

Figure 1 and

Table 2 shows the microorganisms involved in ITS co-infections.

Figure 1 depicts a total of 104 infected specimens, representing 40.9% of the total number tested. Of these, four (1.6%) were triple infections, nine (3.5%) were double infections, and 91 (35.8%) were single infections. HR-HPV (in particular those differing from HPV16 and HPV18) were the microorganisms most frequently involved (100% in triple and double infection, and 93.4% in single infection), being followed by CT (present in 25.0%, 22.2% and 4.4% respectively) and MG (present in 50.0%, 0.0% and 1.1% respectively), as

Table 2 shows. In addition, in women with HR-HPV positivity, one case was identified with MG and CT, and another with MG and NG. The remaining cases were identified as co-infections between different types of HR-HPV. Eight specimens with multiple HR-HPV co-infections were found. These included five cases of co-infection with HPV16 and other HR-HPVs, one case of co-infection with HPV18 and other HR-HPVs, and two cases of co-infection with HPV16, HPV18 and other HR-HPVs. In samples from women negative for HR-HPV, only single ITS were found: CT was found in four samples, MG in one, and TV in another.

4. Discussion

In women participating in a CC screening program who had a previous HR-HVP positive result in the last year, the following rates were documented: a persistent positive result for HR-HPV (38.6%), an any ITS rate (40.9%), and a multiple infection rate (5.1%) involving at least one HR-HPV (in 100%) and one ITS-O (in 38.5%). Furthermore, a significant higher presence of ITS-O was observed in women under 35 years old with a persistent positive HR-HPV result when compared to women with a negative HR-HPV result (20% vs 4.2%).

The present findings are in alignment with those of several studies from various countries, which also identified a simultaneous presence of HR-HPV with the STI-O [

10,

12,

14,

18,

19]. However, it should be note that the rates vary according to the specific population and methods under study. For instance, a study conducted in our city in 2005 which found HR-HPV in the 8.4% of their total population, compared to our 38.6%, and this rate differed significantly according to age (10.6% vs 24.2% in 25-35 years, 4.4% vs 43.0% in 35-44 years, 5% vs 45.8% in 45-54 years, and 0% vs 39.4% in 55-64 years)), but all these differences could be explained by the fact that their participants were not identified as having a previous HR-HPV positive result [

21]. Likewise, a study on female sex workers in Galicia, published in 2012, found that HR-HPV presence was associated with bacterial vaginosis, including TV and Candida spp. [

22]. Moreover, a large European study (with notable Spanish contributions) identified a positive correlation between the number of identified STIs and the risk for CC development [

23]. To the best of our knowledge, however, the present study is the first to assess several STI-O regarding HR-VPH presence in our city and region.

Notwithstanding the unavailability of a framework for the comparison of studies, it is anticipated that our findings will contribute to the scientific evidence that the prevailing guidelines for CC screening would observe to ensure their continued utility. Indeed, the Spanish CC screening programme is currently under review [

24], and nowadays it includes a citology every three years for those between 25 and 34 years of age; and a HR-HPV test every five years for the rest under 65 years, except in case of a positive result for HR-HPV, for which cytology is conditionally performed and the frequency of HR-HPV testing is reduced to one year. Although Spanish guidelines already recognised that co-infection with some STI-O is one of the risk factors for VPH persistence and CIN and CC development [(23)], this concern is not currently incorporated to the general protocol, but it is asserted that specific action protocols should be implemented for women who meet the high-risk criteria for their individual risk assessment and follow-up [

24].

In this regard, the findings of the present study suggest that the routine indication for ITS-O screening should be considered as conditional on a HR-HPV positive result on Spanish women, as it would be cost-effective at the rates observed [

18] and it is aligned with the criteria described in the Spanish CC screening programme consensus [

24]. In fact, given that in vaccinated (younger) women the sensitivity and predictive value of HR-HPV detection is higher than that of cytology, and the frequency of STIs detection is also higher, screening for STI-O by PCR conditional on the primary HR-HPV result has added value for this specific population. Besides, extending testing for STIs-O by using the same unique sample and extract with a similar PCR technique by using multiplex kits (as enabled by Roche Diagnostic reagents, instruments and platforms), would facilitate implementation into laboratory routine contributing to improve its cost-effectiveness.

However, it is important to recognise the limitations of the study. Its cross-sectional design does not allow causality or other longitudinal effects to be observed. The potential for bias arising from the desire to participate could not be assessed. Besides, the relatively small size of our sample limits the power of our results, but this could be improved by recruiting more participants, which would also allow the search for additional related findings. In addition, although the major STIs were the focus of our study, other microorganisms have been found to be associated with the development of CC and other gynaecological conditions [

2,

25,

26]. Therefore, further studies are needed to explore the usefulness of additional microorganism determinations and other biomarkers in order to improve future preventive screening.

5. Conclusions

The findings of the present study support the benefits of implementing STIs screening in Spanish women under 50 years old previously diagnosed with a HR-HPV infection, especially in those under 35.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

www.mdpi.com/xxx/s1, Figure S1: Distribution of age according to the HR-HPV and other sexually transmitted infections (STISs-O) results; Figure S2: Age by STI result.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.R., A.T.B., and M.L.M.; methodology, A.T.B. and M.L.M.; validation, M.P.A. and A.M.M; formal analysis, M.L.M., N.B. and M.A.; investigation, M.L.M., A.T.B..; resources, A.R., L.B., A.B.; data curation, M.L.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.L.M.; writing—review and editing, M.L.M, N.B., M.A., A.T.B., A.M.M., M.P.A., L.B., A.B. A.R.; visualization, M.L.M., A.T.B.; supervision, A.R.; project administration, A.R., A.T.B., M.L.M; funding acquisition, A.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by ROCHE DIAGNOSTICS GmbH (Sanhofer Str. 116 68305 Mannheim, Germany), which provided the PCR reagents (cobas® CT/NG and cobas® TV/MG) for performing the tests included in the present study, contract signed 30/07/2024 (internal code F24-096).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Autonomous Community of Aragon (CEICA) (protocol code PI23/530 and date of approval 20/12/2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data can be accessed upon request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the participants who kindly allowed us to utilize their samples. Furthermore, we are indebted to our laboratory colleagues for their invaluable assistance in the reception and processing of the samples.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

CC: cervical cancer, CEICA: Ethics Committee of the Autonomous Community of Aragon, CT: Chlamydia trachomatis, HPV: human papillomavirus, HR-HPV: high-risk human papillomavirus, IN: Indiana, TV: Trichomonas vaginalis, NG: Neisseria gonorrhoeae, MG: Mycoplasma genitalium, PCR: polymerase chain reaction, RT-PCR: real-time polymerase chain reaction, STIs: sexually transmitted infections, STIs-O: sexually transmitted infections other than HR-HPV, USA: United States of America, WA: Washington.

References

- Asociación Española Contra el Cáncer (AEECC). Dimensiones del cáncer [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2024 Dec 19]. Available from: https://observatorio.contraelcancer.es/explora/dimensiones-del-cancer.

- Li XY, Li G, Gong TT, Lv JL, Gao C, Liu FH, et al. Non-Genetic Factors and Risk of Cervical Cancer: An Umbrella Review of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Observational Studies. Int J Public Health. 2023;68:1605198.

- European Cancer Inequalities Registry. European Commission. Country Cancer Profile, 2023: Spain [Internet]. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).European Commission; 2023 [cited 2024 Dec 18]. Available from: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2023/02/eu-country-cancer-profile-spain-2023_2c613050/260cd4e0-en.pdf.

- Recomendaciones de la Sociedad Española de Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiología Clínica (SEIMC) para el Cribado de Cancer de Cuello de Útero [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2024 Dec 18]. Available from: https://seimc.org/contenidos/inf_institucional/recomendacionesinstitucionales/seimc-rc-2013-1.pdf.

- Mateos Lindermann M, Pérez-Castro S, Pérez-Gracia M, Rodríguez-Iglesias M. Diagnóstico microbiológico de la infección por el virus del papiloma humano. 57. [Internet]. Sociedad Española de Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiología Clínica (SEIMC); 2016 [cited 2024 Dec 18]. (Procedimientos en Microbiología Clínica). Available from: https://www.seimc.org/contenidos/documentoscientificos/procedimientosmicrobiologia/seimc-procedimientomicrobiologia57.pdf.

- Koster S, Gurumurthy RK, Kumar N, Prakash PG, Dhanraj J, Bayer S, et al. Modelling Chlamydia and HPV co-infection in patient-derived ectocervix organoids reveals distinct cellular reprogramming. Nat Commun. 2022 Feb 24;13(1):1030. [CrossRef]

- Yang D, Zhang J, Cui X, Ma J, Wang C, Piao H. Status and epidemiological characteristics of high-risk human papillomavirus infection in multiple centers in Shenyang. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:985561.

- Liu Z, Li P, Zeng X, Yao X, Sun Y, Lin H, et al. Impact of HPV vaccination on HPV infection and cervical related disease burden in real-world settings (HPV-RWS): protocol of a prospective cohort. BMC Public Health. 2022 Nov 18;22(1):2117.

- Gillet E, Meys JFA, Verstraelen H, Verhelst R, De Sutter P, Temmerman M, et al. Association between bacterial vaginosis and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e45201. [CrossRef]

- Lima L de M, Hoelzle CR, Simões RT, Lima MI de M, Fradico JRB, Mateo ECC, et al. Sexually Transmitted Infections Detected by Multiplex Real Time PCR in Asymptomatic Women and Association with Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2018 Sep;40(9):540–6.

- Brusselaers N, Shrestha S, van de Wijgert J, Verstraelen H. Vaginal dysbiosis and the risk of human papillomavirus and cervical cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Jul;221(1):9-18.e8.

- Mosmann JP, Zayas S, Kiguen AX, Venezuela RF, Rosato O, Cuffini CG. Human papillomavirus and Chlamydia trachomatis in oral and genital mucosa of women with normal and abnormal cervical cytology. BMC Infect Dis. 2021 May 5;21(1):422.

- U.S. Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention. Getting Tested for STIs [Internet]. [cited 2024 Dec 17]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/sti/testing/index.html.

- Mendoza L, Mongelos P, Paez M, Castro A, Rodriguez-Riveros I, Gimenez G, et al. Human papillomavirus and other genital infections in indigenous women from Paraguay: a cross-sectional analytical study. BMC Infect Dis. 2013 Nov 9;13:531.

- Deng D, Shen Y, Li W, Zeng N, Huang Y, Nie X. Challenges of hesitancy in human papillomavirus vaccination: Bibliometric and visual analysis. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2023 Sep;38(5):1161–83.

- de Cabezón RH, Sala CV, Gomis SS, Lliso AR, Bellvert CG. Evaluation of cervical dysplasia treatment by large loop excision of the transformation zone (LLETZ). Does completeness of excision determine outcome? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1998 May;78(1):83–9. [CrossRef]

- Chen MM, Mott N, Clark SJ, Harper DM, Shuman AG, Prince MEP, et al. HPV Vaccination Among Young Adults in the US. JAMA. 2021 Apr 27;325(16):1673–4.

- Robial R, Longatto-Filho A, Roteli-Martins CM, Silveira MF, Stauffert D, Ribeiro GG, et al. Frequency of Chlamydia trachomatis infection in cervical intraepithelial lesions and the status of cytological p16/Ki-67 dual-staining. Infectious Agents and Cancer [Internet]. 2017 Jan 6 [cited 2024 Dec 19];12(1):3. [CrossRef]

- Lu Z, Zhao P, Lu H, Xiao M. Analyses of human papillomavirus, Chlamydia trachomatis, Ureaplasma urealyticum, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and co-infections in a gynecology outpatient clinic in Haikou area, China. BMC Womens Health. 2023 Mar 21;23(1):117.

- ICO/IARC Information Centre on HPV and Cancer. Spain: Human Papillomavirus and Related Cancers, Fact Sheet 2023 [Internet]. 2023. Available from: https://hpvcentre.net/statistics/reports/ESP_FS.pdf.

- Puig F, Echavarren V, Yago T, Crespo R, Montañés P, Palacios M, et al. Prevalencia del virus del papiloma humano en una muestra de población urbana en la ciudad de Zaragoza. Prog Obstet Ginecol [Internet]. 2005 Apr 1 [cited 2024 Dec 19];48(4):172–8. Available from: http://www.elsevier.es/es-revista-progresos-obstetricia-ginecologia-151-articulo-prevalencia-del-virus-del-papiloma-13074110.

- Rodriguez-Cerdeira C, Sanchez-Blanco E, Alba A. Evaluation of Association between Vaginal Infections and High-Risk Human Papillomavirus Types in Female Sex Workers in Spain. ISRN Obstet Gynecol. 2012;2012:240190.

- Prospective seroepidemiologic study on the role of Human Papillomavirus and other infections in cervical carcinogenesis: Evidence from the EPIC cohort - Castellsagué - 2014 - International Journal of Cancer - Wiley Online Library [Internet]. [cited 2024 Dec 19]. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ijc.28665.

- Grupo de trabajo sobre cribado de cáncer de cérvix. Documento de consenso sobre la modificación del Programa de Cribado de Cáncer de Cérvix [Internet]. Ministerio de Sanidad. Dirección General de Salud Pública y Equidad en Salud. S.G. de Promoción de la Salud y Prevención; 2023 [cited 2024 Dec 19]. Available from: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/areas/promocionPrevencion/cribado/cribadoCancer/cancerCervix/docs/DocumentoconsensomodificacionCervix.pdf.

- Głowienka-Stodolak M, Bagińska-Drabiuk K, Szubert S, Hennig EE, Horala A, Dąbrowska M, et al. Human Papillomavirus Infections and the Role Played by Cervical and Cervico-Vaginal Microbiota-Evidence from Next-Generation Sequencing Studies. Cancers (Basel). 2024 Jan 17;16(2):399.

- Nguyen HDT, Le TM, Lee E, Lee D, Choi Y, Cho J, et al. Relationship between Human Papillomavirus Status and the Cervicovaginal Microbiome in Cervical Cancer. Microorganisms. 2023 May 27;11(6):1417. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).