Submitted:

20 December 2024

Posted:

23 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Study Population

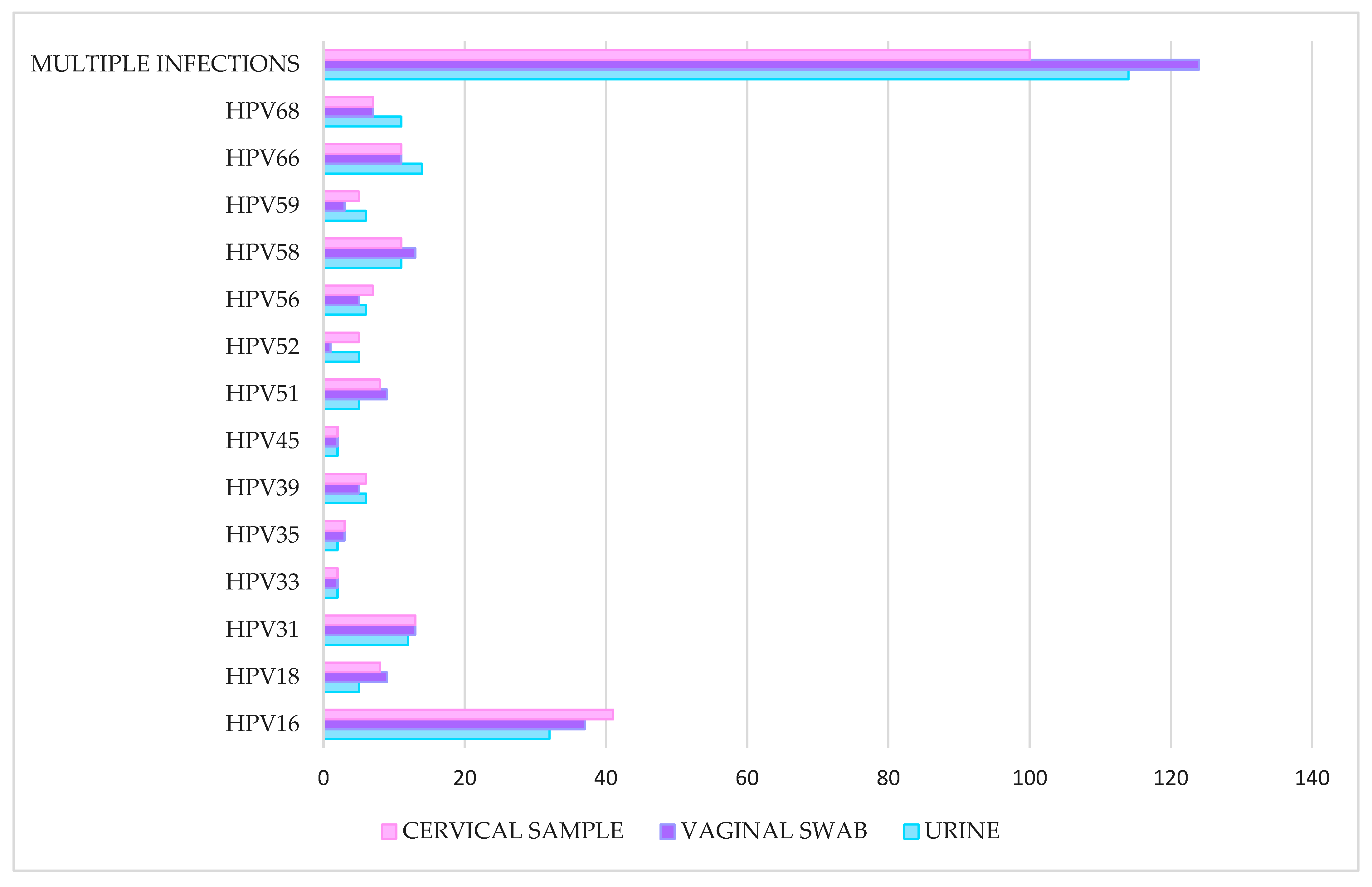

2.2. HPV Detection and Genotyping

2.3. STIs Prevalence

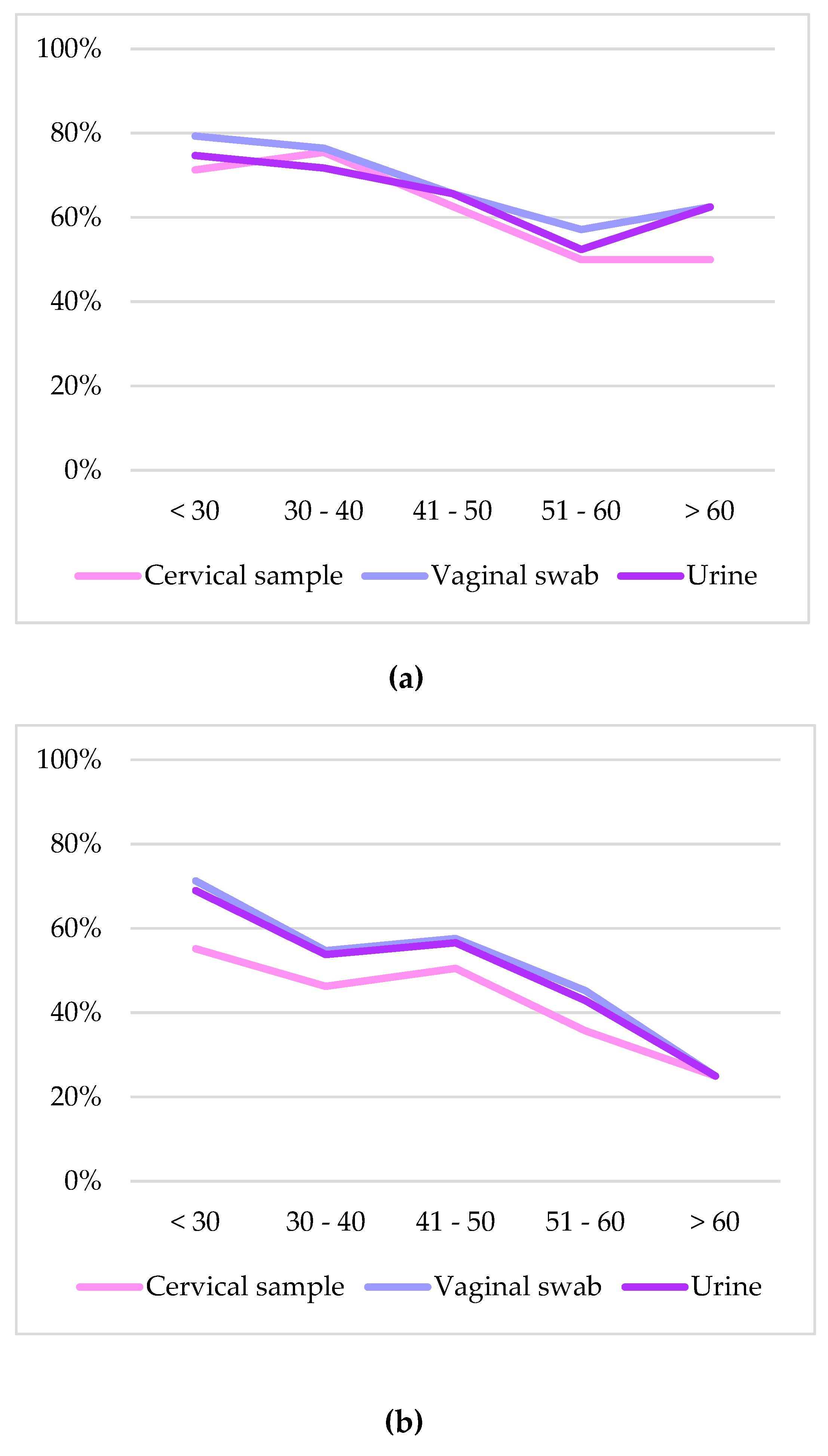

2.4. hrHPV and STIs Prevalence in the Different Age Groups

2.5. hrHPV and STI Co-Infections

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Design and Sample Collection

4.2. Pre-Analytical Samples Processing and Nucleic Acids Extraction

4.3. HPV and STIs Detection

4.4. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R. L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global Cancer Statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA. Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74 (3), 229–263. [CrossRef]

- Burd, E. M. Human Papillomavirus and Cervical Cancer. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2003, 16 (1), 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Walboomers, J. M. M.; Jacobs, M. V.; Manos, M. M.; Bosch, F. X.; Kummer, J. A.; Shah, K. V.; Snijders, P. J. F.; Peto, J.; Meijer, C. J. L. M.; Muñoz, N. Human Papillomavirus Is a Necessary Cause of Invasive Cervical Cancer Worldwide. J. Pathol. 1999, 189 (1), 12–19. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Shen, Z.; Luo, H.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, X. Chlamydia Trachomatis Infection-Associated Risk of Cervical Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016, 95 (13), e3077. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhu, L.; Li, H.; Ma, N.; Huang, H.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Fang, J. Association between Asymptomatic Sexually Transmitted Infections and High-Risk Human Papillomavirus in Cervical Lesions. J. Int. Med. Res. 2019, 47 (11), 5548–5559. [CrossRef]

- Martinelli, M.; Musumeci, R.; Sechi, I.; Sotgiu, G.; Piana, A.; Perdoni, F.; Sina, F.; Fruscio, R.; Landoni, F.; Cocuzza, C. E. Prevalence of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) and Other Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs) among Italian Women Referred for a Colposcopy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2019, 16 (24), 5000. [CrossRef]

- Panchanadeswaran, S.; Johnson, S. C.; Mayer, K. H.; Srikrishnan, A. K.; Sivaran, S.; Zelaya, C. E.; Go, V. F.; Solomon, S.; Bentley, M. E.; Celentano, D. D. Gender Differences in the Prevalence of Sexually Transmitted Infections and Genital Symptoms in an Urban Setting in Southern India. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2006, 82 (6), 491–495. [CrossRef]

- Otieno, F. O.; Ndivo, R.; Oswago, S.; Ondiek, J.; Pals, S.; McLellan-Lemal, E.; Chen, R. T.; Chege, W.; Gray, K. M. Evaluation of Syndromic Management of Sexually Transmitted Infections within the Kisumu Incidence Cohort Study. Int. J. STD AIDS 2014, 25 (12), 851–859. [CrossRef]

- Paudyal, P.; Llewellyn, C.; Lau, J.; Mahmud, M.; Smith, H. Obtaining Self-Samples to Diagnose Curable Sexually Transmitted Infections: A Systematic Review of Patients’ Experiences. PLOS ONE 2015, 10 (4), e0124310. [CrossRef]

- Nodjikouambaye, Z. A.; Compain, F.; Sadjoli, D.; Mboumba Bouassa, R.-S.; Péré, H.; Veyer, D.; Robin, L.; Adawaye, C.; Tonen-Wolyec, S.; Moussa, A. M.; Koyalta, D.; Belec, L. Accuracy of Curable Sexually Transmitted Infections and Genital Mycoplasmas Screening by Multiplex Real-Time PCR Using a Self-Collected Veil among Adult Women in Sub-Saharan Africa. Infect. Dis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 2019, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Ogale, Y.; Yeh, P. T.; Kennedy, C. E.; Toskin, I.; Narasimhan, M. Self-Collection of Samples as an Additional Approach to Deliver Testing Services for Sexually Transmitted Infections: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ Glob. Health 2019, 4 (2), e001349. [CrossRef]

- Serrano, B.; Ibáñez, R.; Robles, C.; Peremiquel-Trillas, P.; De Sanjosé, S.; Bruni, L. Worldwide Use of HPV Self-Sampling for Cervical Cancer Screening. Prev. Med. 2022, 154, 106900. [CrossRef]

- Arbyn, M.; Verdoodt, F.; Snijders, P. J. F.; Verhoef, V. M. J.; Suonio, E.; Dillner, L.; Minozzi, S.; Bellisario, C.; Banzi, R.; Zhao, F.-H.; Hillemanns, P.; Anttila, A. Accuracy of Human Papillomavirus Testing on Self-Collected versus Clinician-Collected Samples: A Meta-Analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15 (2), 172–183. [CrossRef]

- Arbyn, M.; Smith, S. B.; Temin, S.; Sultana, F.; Castle, P. Detecting Cervical Precancer and Reaching Underscreened Women by Using HPV Testing on Self Samples: Updated Meta-Analyses. BMJ 2018, k4823. [CrossRef]

- Arbyn, M.; Peeters, E.; Benoy, I.; Vanden Broeck, D.; Bogers, J.; De Sutter, P.; Donders, G.; Tjalma, W.; Weyers, S.; Cuschieri, K.; Poljak, M.; Bonde, J.; Cocuzza, C.; Zhao, F. H.; Van Keer, S.; Vorsters, A. VALHUDES: A Protocol for Validation of Human Papillomavirus Assays and Collection Devices for HPV Testing on Self-Samples and Urine Samples. J. Clin. Virol. 2018, 107, 52–56. [CrossRef]

- Latsuzbaia, A.; Van Keer, S.; Vanden Broeck, D.; Weyers, S.; Donders, G.; De Sutter, P.; Tjalma, W.; Doyen, J.; Vorsters, A.; Arbyn, M. Clinical Accuracy of Alinity m HR HPV Assay on Self- versus Clinician-Taken Samples Using the VALHUDES Protocol. J. Mol. Diagn. 2023, 25 (12), 957–966. [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.-W.; Ouh, Y.-T.; Hong, J. H.; Min, K. J.; So, K. A.; Kim, T. J.; Paik, E. S.; Lee, J.; Moon, J. H.; Lee, J. K. Comparison of Urine, Self-Collected Vaginal Swab, and Cervical Swab Samples for Detecting Human Papillomavirus (HPV) with Roche Cobas HPV, Anyplex II HPV, and RealTime HR-S HPV Assay. J. Virol. Methods 2019, 269, 77–82. [CrossRef]

- Martinelli, M.; Giubbi, C.; Di Meo, M. L.; Perdoni, F.; Musumeci, R.; Leone, B. E.; Fruscio, R.; Landoni, F.; Cocuzza, C. E. Accuracy of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Testing on Urine and Vaginal Self-Samples Compared to Clinician-Collected Cervical Sample in Women Referred to Colposcopy. Viruses 2023, 15 (9), 1889. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation. WHO Guideline for Screening and Treatment of Cervical Pre-Cancer Lesions for Cervical Cancer Prevention, 2nd ed.; Geneva, 2021.

- Brandt, T.; Wubneh, S. B.; Handebo, S.; Debalkie, G.; Ayanaw, Y.; Alemu, K.; Jede, F.; Von Knebel Doeberitz, M.; Bussmann, H. Genital Self-Sampling for HPV-Based Cervical Cancer Screening: A Qualitative Study of Preferences and Barriers in Rural Ethiopia. BMC Public Health 2019, 19 (1), 1026. [CrossRef]

- Bansil, P.; Wittet, S.; Lim, J. L.; Winkler, J. L.; Paul, P.; Jeronimo, J. Acceptability of Self-Collection Sampling for HPV-DNA Testing in Low-Resource Settings: A Mixed Methods Approach. BMC Public Health 2014, 14 (1), 596. [CrossRef]

- Shafer, M.-A.; Moncada, J.; Boyer, C. B.; Betsinger, K.; Flinn, S. D.; Schachter, J. Comparing First-Void Urine Specimens, Self-Collected Vaginal Swabs, and Endocervical Specimens To Detect Chlamydia Trachomatis and Neisseria Gonorrhoeae by a Nucleic Acid Amplification Test. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2003, 41 (9), 4395–4399. [CrossRef]

- Davis, A.; Gaynor, A. Testing for Sexually Transmitted Diseases in US Public Health Laboratories, 2016. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2020, 47 (2), 122–127. [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for the Laboratory-Based Detection of Chlamydia Trachomatis and Neisseria Gonorrhoeae--2014. MMWR Recomm. Rep. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. Recomm. Rep. 2014, 63 (RR-02), 1–19.

- Verteramo, R.; Pierangeli, A.; Mancini, E.; Calzolari, E.; Bucci, M.; Osborn, J.; Nicosia, R.; Chiarini, F.; Antonelli, G.; Degener, A. M. Human Papillomaviruses and Genital Co-Infections in Gynaecological Outpatients. BMC Infect. Dis. 2009, 9 (1), 16. [CrossRef]

- Friberg, J.; Gnarpe, H. Mycoplasmas in Semen from Fertile And-Infertile Men. Andrologia 2009, 6 (1), 45–52. [CrossRef]

- Valasoulis, G.; Pouliakis, A.; Michail, G.; Magaliou, I.; Parthenis, C.; Margari, N.; Kottaridi, C.; Spathis, A.; Leventakou, D.; Ieronimaki, A.-I.; Androutsopoulos, G.; Panagopoulos, P.; Daponte, A.; Tsiodras, S.; Panayiotides, I. G. Cervical HPV Infections, Sexually Transmitted Bacterial Pathogens and Cytology Findings—A Molecular Epidemiology Study. Pathogens 2023, 12 (11), 1347. [CrossRef]

- Kong, F.; Ma, Z.; James, G.; Gordon, S.; Gilbert, G. L. Species Identification and Subtyping of Ureaplasma Parvum and Ureaplasma Urealyticum Using PCR-Based Assays. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2000, 38 (3), 1175–1179. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Li, T.; Chen, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, G.; Liu, Z. Epidemiological Investigation of the Relationship between Common Lower Genital Tract Infections and High-Risk Human Papillomavirus Infections among Women in Beijing, China. PLOS ONE 2017, 12 (5), e0178033. [CrossRef]

- Koskela, P.; Anttila, T.; Bjørge, T.; Brunsvig, A.; Dillner, J.; Hakama, M.; Hakulinen, T.; Jellum, E.; Lehtinen, M.; Lenner, P.; Luostarinen, T.; Pukkala, E.; Saikku, P.; Thoresen, S.; Youngman, L.; Paavonen, J. Chlamydia Trachomatis Infection as a Risk Factor for Invasive Cervical Cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2000, 85 (1), 35–39. [CrossRef]

- Smith, J. S.; Bosetti, C.; Muñoz, N.; Herrero, R.; Bosch, F. X.; Eluf-Neto, J.; Meijer, C. J. L. M.; Van Den Brule, A. J. C.; Franceschi, S.; Peeling, R. W. Chlamydia Trachomatis and Invasive Cervical Cancer: A Pooled Analysis of the IARC Multicentric Case-control Study. Int. J. Cancer 2004, 111 (3), 431–439. [CrossRef]

- Biernat-Sudolska, M.; Szostek, S.; Rojek-Zakrzewska, D.; Klimek, M.; Kosz-Vnenchak, M. Concomitant Infections with Human Papillomavirus and Various Mycoplasma and Ureaplsasma Species in Women with Abnormal Cervical Cytology. Adv. Med. Sci. 2011, 56 (2), 299–303. [CrossRef]

- Robial, R.; Longatto-Filho, A.; Roteli-Martins, C. M.; Silveira, M. F.; Stauffert, D.; Ribeiro, G. G.; Linhares, I. M.; Tacla, M.; Zonta, M. A.; Baracat, E. C. Frequency of Chlamydia Trachomatis Infection in Cervical Intraepithelial Lesions and the Status of Cytological P16/Ki-67 Dual-Staining. Infect. Agent. Cancer 2017, 12 (1), 3. [CrossRef]

- Castle, P. E.; Escoffery, C.; Schachter, J.; Rattray, C.; Schiffman, M.; Moncada, J.; Sugai, K.; Brown, C.; Cranston, B.; Hanchard, B.; Palefsky, J. M.; Burk, R. D.; Hutchinson, M. L.; Strickler, H. D. Chlamydia Trachomatis, Herpes Simplex Virus 2, and Human T-Cell Lymphotrophic Virus Type 1 Are Not Associated With Grade of Cervical Neoplasia in Jamaican Colposcopy Patients: Sex. Transm. Dis. 2003, 30 (7), 575–580. [CrossRef]

- Castle, P. E.; Giuliano, A. R. Chapter 4: Genital Tract Infections, Cervical Inflammation, and Antioxidant Nutrients--Assessing Their Roles as Human Papillomavirus Cofactors. JNCI Monogr. 2003, 2003 (31), 29–34. [CrossRef]

- Rokos, T.; Holubekova, V.; Kolkova, Z.; Hornakova, A.; Pribulova, T.; Kozubik, E.; Biringer, K.; Kudela, E. Is the Physiological Composition of the Vaginal Microbiome Altered in High-Risk HPV Infection of the Uterine Cervix? Viruses 2022, 14 (10), 2130. [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.; Cerqueira, F.; Medeiros, R. Chlamydia Trachomatis Infection: Implications for HPV Status and Cervical Cancer. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2014, 289 (4), 715–723. [CrossRef]

- Lv, P.; Zhao, F.; Xu, X.; Xu, J.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, Z. Correlation between Common Lower Genital Tract Microbes and High-Risk Human Papillomavirus Infection. Can. J. Infect. Dis. Med. Microbiol. 2019, 2019, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Lukic, A.; Canzio, C.; Patella, A.; Giovagnoli, M.; Cipriani, P.; Frega, A.; Moscarini, M. Determination of Cervicovaginal Microorganisms in Women with Abnormal Cervical Cytology: The Role of Ureaplasma Urealyticum. Anticancer Res. 2006, 26 (6C), 4843–4849.

- Liang, Y.; Chen, M.; Qin, L.; Wan, B.; Wang, H. A Meta-Analysis of the Relationship between Vaginal Microecology, Human Papillomavirus Infection and Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia. Infect. Agent. Cancer 2019, 14 (1), 29. [CrossRef]

- A, D.; Bi, H.; Zhang, D.; Xiao, B. Association between Human Papillomavirus Infection and Common Sexually Transmitted Infections, and the Clinical Significance of Different Mycoplasma Subtypes. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1145215. [CrossRef]

- Parthenis, C.; Panagopoulos, P.; Margari, N.; Kottaridi, C.; Spathis, A.; Pouliakis, A.; Konstantoudakis, S.; Chrelias, G.; Chrelias, C.; Papantoniou, N.; Panayiotides, I. G.; Tsiodras, S. The Association between Sexually Transmitted Infections, Human Papillomavirus, and Cervical Cytology Abnormalities among Women in Greece. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2018, 73, 72–77. [CrossRef]

- Macpherson, I.; Russell, W. Transformations in Hamster Cells Mediated by Mycoplasmas. Nature 1966, 210 (5043), 1343–1345. [CrossRef]

- Tsai, S.; Wear, D. J.; Shih, J. W.; Lo, S. C. Mycoplasmas and Oncogenesis: Persistent Infection and Multistage Malignant Transformation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1995, 92 (22), 10197–10201. [CrossRef]

- Ssedyabane, F.; Amnia, D. A.; Mayanja, R.; Omonigho, A.; Ssuuna, C.; Najjuma, J. N.; Freddie, B. HPV-Chlamydial Coinfection, Prevalence, and Association with Cervical Intraepithelial Lesions: A Pilot Study at Mbarara Regional Referral Hospital. J. Cancer Epidemiol. 2019, 2019, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Naldini, G.; Grisci, C.; Chiavarini, M.; Fabiani, R. Association between Human Papillomavirus and Chlamydia Trachomatis Infection Risk in Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Public Health 2019, 64 (6), 943–955. [CrossRef]

- Arévalos, A.; Valenzuela, A.; Mongelós, P.; Barrios, H.; Rodríguez, M. I.; Báez, R.; Centurión, C.; Vester, J.; Soilán, A.; Ortega, M.; Meza, L.; Páez, M.; Castro, A.; Cristaldo, C.; Soskin, A.; Deluca, G.; Baena, A.; Herrero, R.; Almonte, M.; Kasamatsu, E.; Mendoza, L.; ESTAMPA Paraguayan Study Group. Genital Infections in High-Risk Human Papillomavirus Positive Paraguayan Women Aged 30–64 with and without Cervical Lesions. PLOS ONE 2024, 19 (10), e0312947. [CrossRef]

- Ginindza, T. G.; Dlamini, X.; Almonte, M.; Herrero, R.; Jolly, P. E.; Tsoka-Gwegweni, J. M.; Weiderpass, E.; Broutet, N.; Sartorius, B. Prevalence of and Associated Risk Factors for High Risk Human Papillomavirus among Sexually Active Women, Swaziland. PLOS ONE 2017, 12 (1), e0170189. [CrossRef]

- ECDC. STI Cases on the Rise across Europe. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/news-events/sti-cases-rise-across-europe.

- Smith, J. H. F. Bethesda 2001. Cytopathology 2002, 13 (1), 4–10. [CrossRef]

- WHO Classification of Tumours. Female Genital Tumours, 5th ed.; IARC: Lyon, 2020; Vol. 4.

| Cytology (n = 345) | N | % |

| HSIL | 47 | 13.6% |

| ASCH | 26 | 7.5% |

| LSIL | 164 | 47.5% |

| ASCUS | 86 | 24.9% |

| AGC | 14 | 4.1% |

| NILM | 8 | 2.3% |

| Colposcopy (n = 345) | ||

| POS | 127 | 36.8% |

| NEG | 218 | 63.2% |

| Histological outcome (n = 84) | ||

| Negative | 11 | 13.1% |

| CIN 1 | 13 | 15.5% |

| CIN 2 | 12 | 14.3% |

| CIN 3 | 44 | 52.4% |

| Cervical cancer | 4 | 4.8% |

|

Cervical sample n. (%) n = 229 |

Vaginal swab n. (%) n = 244 |

Urine n. (%) n = 233 |

|

| Single hrHPV | 129 (56.3%) | 120 (49.2%) | 119 (51.1%) |

| 2 hrHPV | 58 (25.3%) | 77 (31.6%) | 65 (27.9%) |

| 3 hrHPV | 30 (13.1%) | 24 (9.8%) | 27 (11.6%) |

| More than 3 hrHPV | 12 (5.2%) | 23 (9.4%) | 22 (9.4%) |

| HPV type | +/+¹ | +/- | -/+ | -/- | Agreement [%] | Kappa² [95% CI] | |

| hrHPV | 227 | 2 | 17 | 96 | 94.4 | 0.870 (0.814 - 0.927) | |

| HPV16 | 79 | 1 | 7 | 255 | 97.7 | 0.936 (0.893 - 0.980) | |

| HPV18 | 18 | 0 | 4 | 320 | 98.8 | 0.894 (0.791 - 0.997) | |

| HPV31 | 44 | 2 | 9 | 287 | 96.8 | 0.870 (0.795 - 0.945) | |

| HPV33 | 10 | 5 | 3 | 324 | 97.7 | 0.702 (0.506 - 0.898) | |

| HPV35 | 7 | 0 | 4 | 331 | 98.8 | 0.772 (0.556 - 0.988) | |

| Total | HPV39 | 19 | 1 | 2 | 320 | 99.1 | 0.922 (0.835 - 1.000) |

| population | HPV45 | 10 | 2 | 5 | 325 | 98.0 | 0.730 (0.539 - 0.922) |

| (n = 342) | HPV51 | 26 | 0 | 10 | 306 | 97.1 | 0.823 (0.717 - 0.929) |

| HPV52 | 27 | 3 | 3 | 309 | 98.2 | 0.890 (0.804 - 0.977) | |

| HPV56 | 25 | 0 | 4 | 313 | 98.8 | 0.920 (0.842 - 0.998) | |

| HPV58 | 24 | 2 | 8 | 308 | 97.1 | 0.812 (0.699 - 0.925) | |

| HPV59 | 19 | 0 | 4 | 319 | 98.8 | 0.899 (0.800 - 0.997) | |

| HPV66 | 33 | 1 | 8 | 300 | 97.4 | 0.865 (0.779 - 0.951) | |

| HPV68 | 27 | 2 | 8 | 305 | 97.1 | 0.828 (0.724 - 0.932) |

| HPV type | +/+¹ | +/- | -/+ | -/- | Agreement [%] | Kappa² [95% CI] | |

| hrHPV | 214 | 15 | 19 | 94 | 90.06 | 0.773 (0.701 - 0.845) | |

| HPV16 | 68 | 12 | 11 | 251 | 93.3 | 0.812 (0.738 - 0.886) | |

| HPV18 | 14 | 4 | 3 | 321 | 98.0 | 0.789 (0.638 - 0.941) | |

| HPV31 | 43 | 2 | 6 | 291 | 97.7 | 0.901 (0.834 - 0.969) | |

| HPV33 | 10 | 5 | 3 | 324 | 97.7 | 0.702 (0.506 - 0.898) | |

| HPV35 | 7 | 0 | 6 | 329 | 98.2 | 0.692 (0.459 - 0.924) | |

| Total | HPV39 | 16 | 4 | 4 | 318 | 97.7 | 0.788 (0.645 - 0.930) |

| population | HPV45 | 9 | 3 | 2 | 328 | 98.5 | 0.775 (0.584 - 0.966) |

| (n = 342) | HPV51 | 23 | 3 | 11 | 305 | 95.9 | 0.745 (0.617 - 0.872) |

| HPV52 | 24 | 6 | 2 | 310 | 97.7 | 0.775 (0.584 - 0.966) | |

| HPV56 | 25 | 0 | 5 | 312 | 98.5 | 0.901 (0.816 - 0.987) | |

| HPV58 | 21 | 5 | 8 | 308 | 96.2 | 0.743 (0.609 - 0.877) | |

| HPV59 | 18 | 1 | 4 | 319 | 98.5 | 0.870 (0.758 - 0.982) | |

| HPV66 | 31 | 3 | 11 | 297 | 95.9 | 0.793 (0.689 - 0.897) | |

| HPV68 | 23 | 6 | 17 | 296 | 93.3 | 0.630 (0.492 - 0.769) |

| UP n (%) | UU n (%) | MH n (%) | MG n (%) | CT n (%) | NG n (%) | TV n (%) | |

| Cervical sample (n = 342) | 129 (37.7%) | 34 (9.9%) | 31 (9.1%) | 8 (2.3%) | 11 (3.2%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (1.2%) |

| Vaginal swab (n = 342) | 165 (48.2%) | 40 (11.7%) | 40 (11.7%) | 11 (3.2%) | 13 (3.8%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (0.9%) |

| Urine (n = 342) | 158 (46.2%) | 38 (11.1%) | 39 (11.4%) | 10 (2.9%) | 11 (3.2%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (0.9%) |

|

Cervical sample n. (%) n = 164 |

Vaginal swab n. (%) n = 198 |

Urine n. (%) n = 193 |

|

| Single STI | 122 (74.4%) | 143 (72.2%) | 141 (73.1%) |

| 2 STIs | 32 (19.5%) | 38 (19.2%) | 39 (20.2%) |

| More than 2 STIs | 10 (6.1%) | 17 (8.6%) | 13 (6.7%) |

| STI | +/+¹ | +/- | -/+ | -/- | Agreement [%] | Kappa² [95% CI] | |

|

Total Population (n = 342) |

STI | 162 | 2 | 36 | 142 | 88.9 | 0.779 (0.714 - 0.844) |

| UP | 127 | 2 | 38 | 175 | 88.3 | 0.764 (0.697 - 0.831) | |

| UU | 30 | 4 | 10 | 298 | 95.9 | 0.788 (0.681 - 0.895) | |

| MH | 31 | 0 | 9 | 302 | 97.4 | 0.859 (0.769 - 0.949) | |

| MG | 8 | 0 | 3 | 331 | 99.1 | 0.838 (0.657 - 1.000) | |

| CT | 11 | 0 | 2 | 329 | 99.4 | 0.914 (0.795 - 1.000) | |

| NG | 0 | 0 | 0 | 342 | 100 | Not Applicable | |

| TV | 3 | 1 | 0 | 338 | 99.7 | 0.856 (0.576 - 1.000) |

| STI | +/+¹ | +/- | -/+ | -/- | Agreement [%] | Kappa² [95% CI] | |

| STI | 156 | 8 | 37 | 141 | 86.8 | 0.738 (0.668 - 0.808) | |

| UP | 121 | 8 | 37 | 176 | 86.8 | 0.732 (0.660 - 0.804) | |

| UU | 26 | 8 | 12 | 296 | 94.1 | 0.690 (0.562 - 0.817) | |

| Total | MH | 27 | 4 | 12 | 299 | 95.3 | 0.746 (0.627 - 0.864) |

| population | MG | 8 | 0 | 2 | 332 | 99.4 | 0.886 (0.729 - 1.000) |

| (n = 342) | CT | 9 | 2 | 2 | 329 | 98.8 | 0.812 (0.632 - 0.992) |

| NG | 0 | 0 | 0 | 342 | 100 | Not Applicable | |

| TV | 3 | 1 | 0 | 338 | 99.7 | 0.856 (0.576 - 1.000) |

| UP | UU | MH | MG | CT | NG | TV | |||||||||

| n (%) | p | n (%) | p | n (%) | p | n (%) | p | n (%) | p | n (%) | p | n (%) | p | ||

| Cervical samples |

hrHPV-positive (n = 229) |

102 (44.5%) | *** | 27 (11.8%) | 0.15 | 29 (12.7%) | *** | 8 (3.5%) | 0.06 | 10 (4.4%) | 0.11 | 0 (0%) | 1 | 3 (1.3%) | 1 |

| hrHPV-negative (n = 113) |

27 (23.9%) | 7 (6.2%) | 2 (1.8%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.9%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.9%) | ||||||||

| Vaginal swabs |

hrHPV-positive (n = 244) |

137 (56.1%) | *** | 32 (13.1%) | 0.27 | 37 (15.2%) | ** | 11 (4.5%) | 0.04* | 12 (4.9%) | 0.12 | 0 (0%) | 1 | 2 (0.8%) | 1 |

| hrHPV-negative (n = 98) |

28 (28.6%) | 8 (8.2%) | 3 (3.1%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.0%) | ||||||||

| Urine | hrHPV-positive (n = 233) |

125 (53.6%) | *** | 30 (12.9%) | 0.18 | 34 (14.6%) | ** | 9 (3.9%) | 0.18 | 10 (4.3%) | 0.18 | 0 (0%) | 1 | 2 (0.9%) | 1 |

| hrHPV-negative (n = 109) |

33 (30.3%) | 8 (7.3%) | 5 (4.6%) | 1 (0.9%) | 1 (0.9%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.9%) | ||||||||

| hrHPV positivity on cervical sample n (%) | |

| Age in years (n = 342) | |

| <30 | 62/87 (71.3%) |

| 30-40 | 80/106 (75.5%) |

| 41-50 | 61/99 (61.6%) |

| 51-60 | 21/42 (50.0%) |

| >60 | 4/8 (50.0%) |

| Cytology (n = 342) | |

| NILM | 1/8 (12.5%) |

| ASCUS | 52/85 (61.2%) |

| AGC | 5/14 (35.7%) |

| LSIL | 112/162 (69.1%) |

| ASCH | 21/26 (80.8%) |

| HSIL | 38/47 (80.9%) |

| Colposcopy (n = 342) | |

| Negative | 126/217 (58.0%) |

| Positive | 103/125 (82.4%) |

| Histology (n = 84) | |

| < CIN 2 | 16/24 (66.7%) |

| ≥ CIN 2 | 58/60 (96.7%) |

| hrHPV+ / STI+ | hrHPV+ / STI- | hrHPV- / STI+ | hrHPV- / STI- | Total | |

| Total population | 130 (38.0%) | 99 (28.9%) | 34 (9.9%) | 79 (23.1%) | 342 |

| Age in years (n = 342) | |||||

| <30 | 40 (46.0%) | 22 (25.3%) | 8 (9.2%) | 17 (19.5%) | 87 |

| 30-40 | 40 (37.7%) | 40 (37.7%) | 9 (8.5%) | 17 (16.1%) | 106 |

| 41-50 | 34 (34.3%) | 27 (27.3%) | 16 (16.2%) | 22 (22.2%) | 99 |

| 51-60 | 13 (31.0%) | 8 (19.0%) | 2 (4.8%) | 19 (45.2%) | 42 |

| >60 | 2 (25.0%) | 2 (25.0%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (50.0%) | 8 |

| Cytology (n = 342) | |||||

| NILM | 0 (0%) | 1 (12.5%) | 1 (12.5%) | 6 (75.0%) | 8 |

| ASCUS | 26 (30.6%) | 26 (30.6%) | 10 (11.8%) | 23 (27.0%) | 85 |

| AGC | 3 (21.4%) | 2 (14.3%) | 1 (7.1%) | 8 (57.1%) | 14 |

| LSIL | 71 (43.8%) | 41 (25.3%) | 15 (9.3%) | 35 (21.6%) | 162 |

| ASCH | 13 (50.0%) | 8 (30.8%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (19.2%) | 26 |

| HSIL | 16 (34.0%) | 22 (46.8%) | 7 (14.9%) | 2 (4.3%) | 47 |

| Colposcopy (n = 342) | |||||

| Negative | 73 (33.6%) | 53 (24.4%) | 28 (12.9%) | 63 (29.1%) | 217 |

| Positive | 57 (45.6%) | 46 (36.8%) | 6 (4.8%) | 16 (12.8%) | 125 |

| Histology (n = 84) | |||||

| < CIN 2 | 10 (41.7%) | 6 (25.0%) | 2 (8.3%) | 6 (25.0%) | 24 |

| ≥ CIN 2 | 29 (48.3%) | 29 (48.3%) | 2 (3.4%) | 0 (0%) | 60 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).