1. Introduction

In an era where digital transformation is reshaping industries, social media has emerged as a central platform for communication, influence, and promotion. The rapid growth of social platforms has created new opportunities for brands, businesses, and influencers to engage with their audiences and drive growth. As the need for personalized, efficient, and scalable strategies increases, AI tools have become crucial for optimizing social promotion efforts (Akilkhanov 2024). One such tool, the Copilot for social promotion, leverages advanced AI technologies to assist in the creation, management, and evaluation of social campaigns.

This chapter explores the application of copilot technology in social promotion, focusing on its ability to automate content generation, audience targeting, and campaign optimization. The paper examines how AI-driven copilots can support marketers in navigating the complexities of social media algorithms, consumer behavior, and engagement metrics. Additionally, it addresses the ethical considerations and potential challenges of relying on AI for promotional activities in a highly competitive and fast-paced digital environment. By analyzing the effectiveness of copilot tools, this study aims to provide insights into how they can enhance the efficiency and success of social promotion campaigns across various platforms.

Through a combination of theoretical exploration and practical case studies, this chapter seeks to contribute to the growing body of knowledge on AI’s role in transforming digital marketing strategies and its impact on the future of social promotion.

In the ever-evolving landscape of social media promotion, the integration of AI tools has become a game-changer. In this context, the social media manager assumes the role of the captain, guiding campaigns, crafting strategies, and interpreting data to drive engagement and growth (Galitsky 2023). Meanwhile, the AI acts as the copilot, providing invaluable support in navigating the complexities of the digital space, optimizing content creation, and enhancing campaign performance. Much like a captain and copilot work in tandem to ensure a successful flight, the collaboration between human expertise and AI technology forms a powerful partnership that maximizes the potential of social promotion efforts.

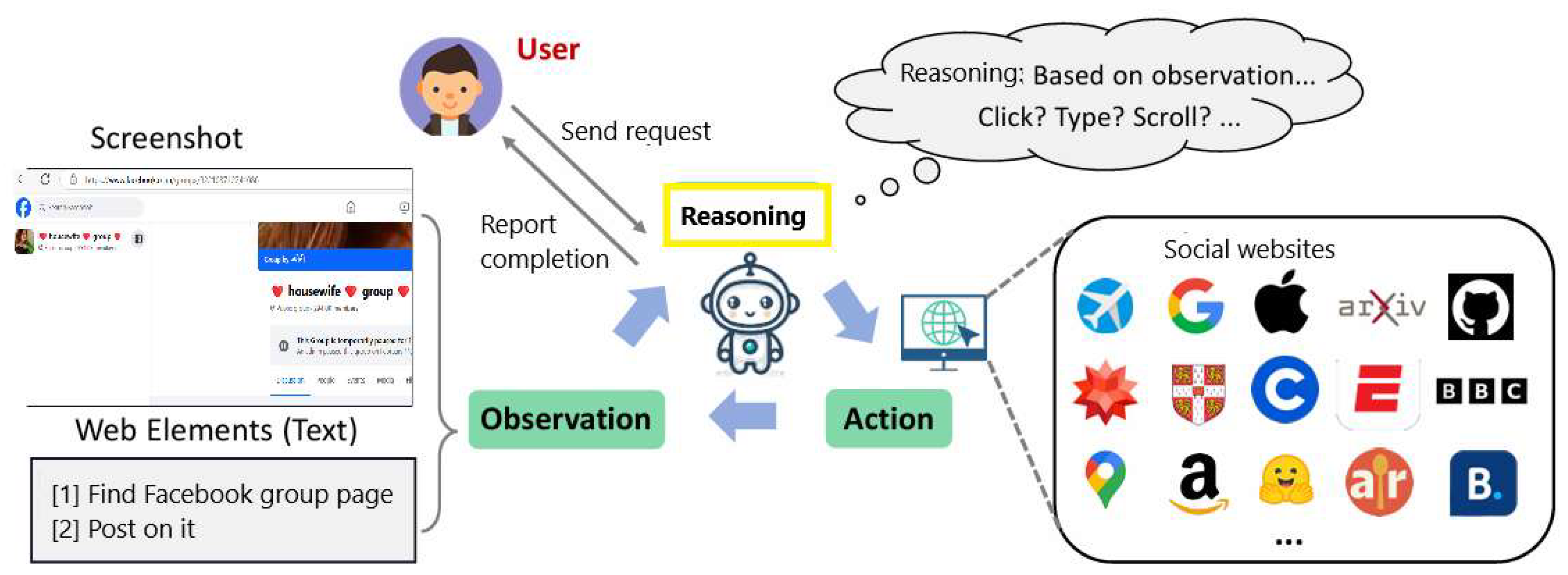

By leveraging AI tools, social media managers can unlock new opportunities for more efficient, personalized, and impactful campaigns (

Figure 1). These tools assist in everything from content generation to audience segmentation, streamlining processes and improving overall results. Eager & Brunton (2023), Xu (2024), and (Su and Yang 2023) study the transformative role of AI copilots in education, focusing on how tools such as ERNIE Bot (PRNewswire 2023), ElevenLabs, and Classpoint can enhance the effectiveness of teaching strategies. Although applications of copilots in self-driving cars, education, retail (Furmakiewicz et al 2024), health (Chiam et al 2024, Zou et al 2024) and other domains has been thoroughly explored, it is not the case for social promotion domain.

In this chapter we introduce A Social Promotion Copilot (SPC) for the optimization of social campaigns, drive engagement, and empower brands to navigate the digital landscape with greater agility and success. SPC is also a part of a customer relationship management pipeline (Galitsky 2021) supporting communication with a customer, customer retention and handling complaints. Moreover, SPC can be an assistant in individual social promotion in professional and personal domains.

Existing web agents are typically evaluated only in simplified web simulators or static web snapshots, greatly limiting their applicability in real-world scenarios. To bridge this gap, we enable SPC with LLM-powered web agent capabilities so that it can complete user instructions end-to-end by interacting with real-world social websites.

1.1. Social Promotion of New Products

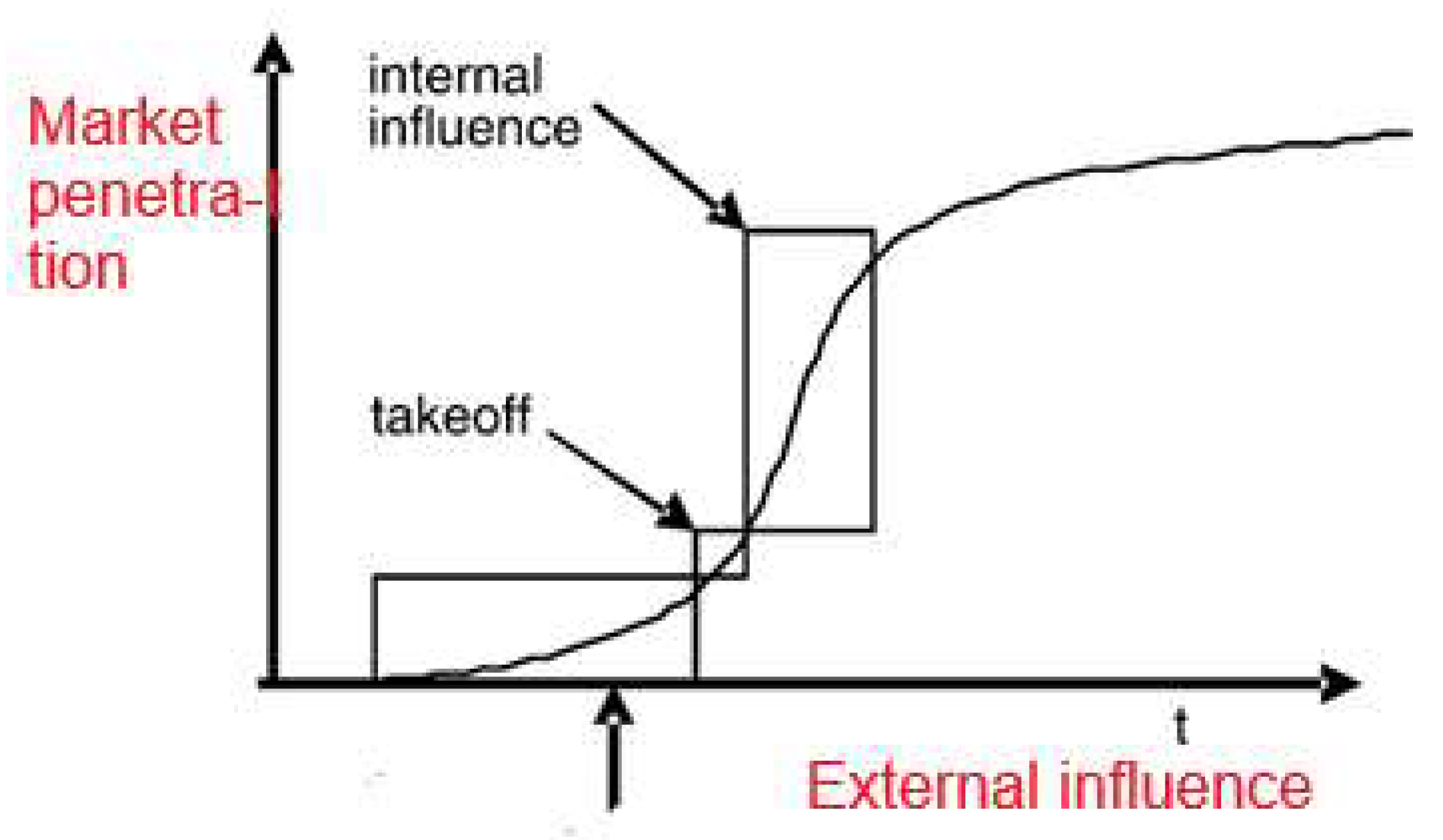

A significant portion of a firm’s efforts is dedicated to introducing new products and technologies to the market. However, these initiatives come with substantial risks, as launching a new product is inherently unpredictable (Mahajan & Muller, 1979). The initial market penetration phase is particularly critical, as it sets the trajectory for the product’s future adoption. A rapid and widespread takeoff can provide a competitive edge, trigger viral consumer adoption, and ultimately determine whether the product succeeds or fails (Golder & Tellis, 2004).

To navigate these uncertainties, promotional strategies play a crucial role in accelerating early diffusion. By strategically deploying marketing efforts—especially promotional campaigns—companies can stimulate initial demand, generate awareness, and create momentum that drives product adoption. Effective promotional activities not only help overcome market inertia but also maximize exposure, encourage early adopters, and establish a foundation for long-term success.

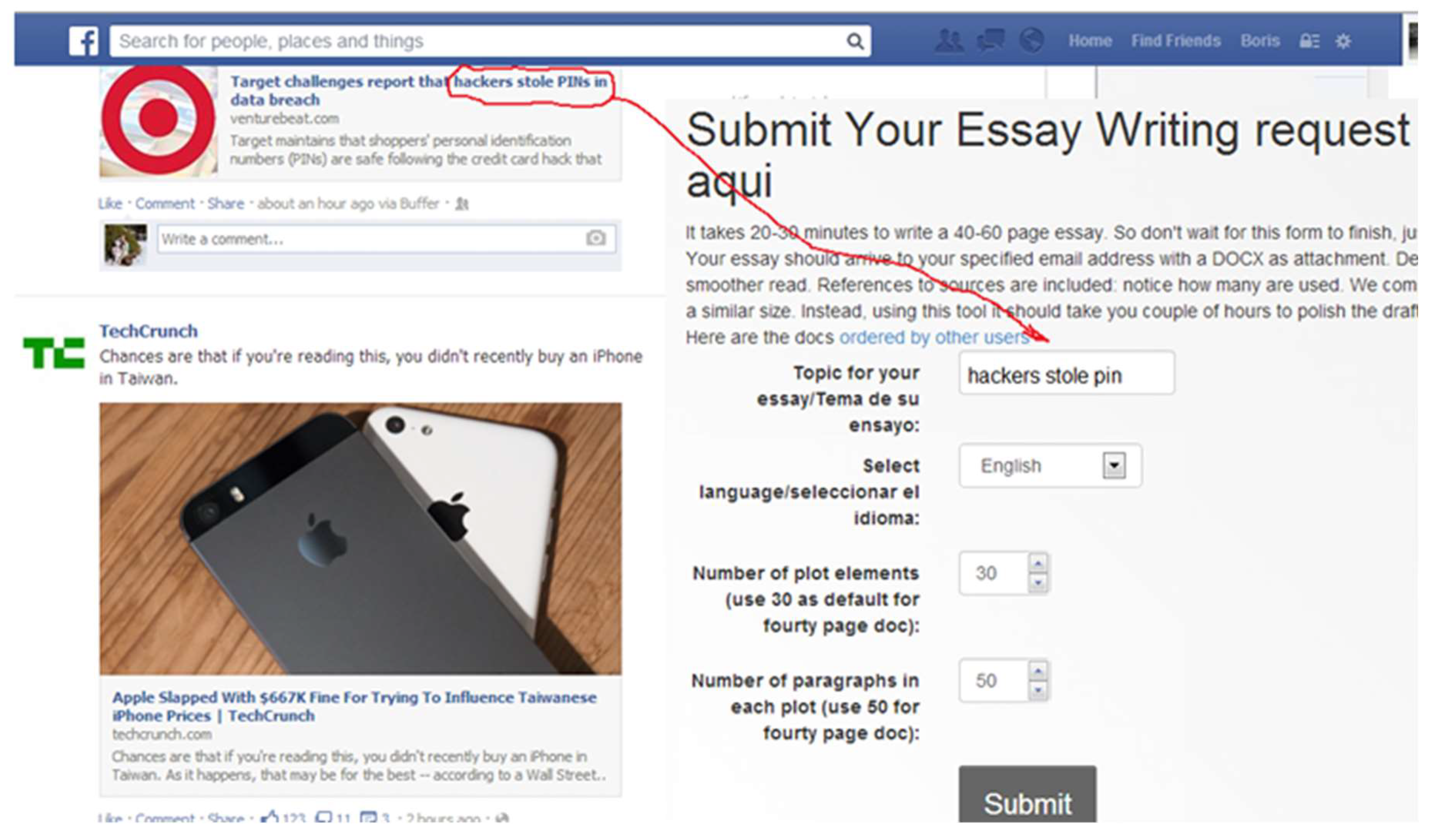

SPC can significantly enhance these promotional efforts by leveraging AI-driven automation, real-time data analysis, and personalized engagement to optimize product launches. By monitoring consumer sentiment, identifying key influencers, and tailoring promotional content to specific audience segments, SPC ensures that marketing messages reach the right people at the right time. It can dynamically adjust campaign strategies based on real-time feedback, ensuring that promotional efforts remain relevant and impactful throughout the diffusion process. Additionally, SPC can automate interactions, fostering engagement across social platforms and amplifying word-of-mouth effects. By streamlining and optimizing promotional activities, a Social Promotion Copilot increases the likelihood of a successful product takeoff, reduces the risk of launch failure, and maximizes the efficiency of marketing investments. At the level of an individual user, performing social promotion, SPC might raise self-confidence (

Figure 2).

2. Social Promotion Copilot

The Social Promotion Copilot is an AI-driven tool designed to enhance visibility, engage audiences, and automate content distribution across social media platforms. It assists users in crafting optimized posts, analyzing engagement, and suggesting strategies for better outreach.

The users provide a raw idea or draft (e.g., “Promote my new blog post about AI trends”), and the copilot enhances and optimizes the post for different platforms:

- 1)

Twitter/X: Concise, engaging with hashtags → “🚀 AI is transforming industries! Check out the latest trends in my new blog: [link] #AI #FutureTech”

- 2)

LinkedIn: Professional and thought-leadership style → “The AI landscape is evolving rapidly. In my latest article, I explore key trends shaping the future. Read more: [link]”

- 3)

Instagram/Facebook: Visually engaging, story-driven → “AI is the future! Swipe to see the latest trends. Full article here: [link] 📲🔥 #ArtificialIntelligence #TechNews”

The copilot supports auto-scheduling and multi-platform posting. Posts can be scheduled for optimal engagement times (based on AI analysis). The system automatically adapts the same content for multiple platforms with platform-specific tweaks (

Figure 3). Moreover, the copilot performs engagement analysis and smart recommendations, monitoring likes, shares, and comments. It uses LLM-driven insights to suggest improvements:

- 1)

“Your posts perform best on Thursdays at 6 PM.”

- 2)

“Try adding a question to increase engagement!”

- 3)

“Hashtags #AI and #Tech are trending, consider adding them!”

It can also do LLM-powered audience targeting and hashtag suggestions, identifying target audiences based on post content and suggesting relevant hashtags and tagging influencers for better reach. The copilot drafts quick replies to user comments and detects potential collaborations and suggests outreach messages.

An example flow in action can be as follows:

For user input “I want to promote my new startup on social media” social promotion copilot optimizes post suggestions:

- 1)

Twitter: “Exciting news! 🚀 Our startup [Startup Name] is launching soon! Stay tuned for innovation in [industry]. #Startup #Innovation”

- 2)

LinkedIn: “We are thrilled to introduce [Startup Name], a game-changer in [industry]. Learn more about our journey here: [link]”

- 3)

Instagram: “A dream turning into reality! 🏆 Follow our startup journey. #Startuplife #NewBeginnings”

It suggests best posting time “Your audience is most active between 5 PM and 11 PM. Schedule now?” and Hashtag & Tagging: “#Entrepreneurship #TechStartup #Innovation”. Copilot also recommends to “Consider tagging industry leaders like @TechInfluencer to boost visibility!”. If someone comments

“Congrats!”, Copilot suggests:

“Thank you! Exciting times ahead! 🚀”. Copilot can help in a broad spectrum of domains including health (

Figure 4).

2.1. An Algorithm for SPC Engagement Analysis and Recommendation

The algorithm monitors engagement, learns from past performance, and adapts SPC’s social promotion strategy in real time. It enables data-driven, intelligent posting strategies, ensuring maximum visibility and user interaction.

Its inputs are:

Post Data: Text, media, category (complaint, promotion, discussion, etc.).

Engagement Metrics: Likes, shares, comments, replies, follower growth.

Timeframe: The period over which engagement is analyzed.

Competitor Benchmarking: Engagement metrics of similar posts by competitors (if available).

Outputs:

Performance Score: Engagement score per post.

Smart Recommendations: Suggestions to improve future posts (timing, tone, content type).

Collection of engagement metrics for each post:

Weighted engagement score E=wLL+wSS+wCC+wRR+wFF

Different weights based on impact need to be involved (e.g., shares are more valuable than likes).

Engagement score needs to be relative to past performance and competitors:

Enormalized=(E−Emin) / (Emax−Emin).

Smart recommendation generation identify trends in engagement. In includes a comparison of E scores over time to detect improvement or decline, identification of high-engagement content types (e.g., complaints get more shares, promotions get more likes), and detection of peak engagement timeframes (when users interact the most).

Generation of post optimization recommendations include:

- 1)

Timing Adjustment: If peak engagement occurs at 6 PM, shift future post scheduling.

- 2)

Content Type Adaptation: If complaints generate the highest interaction, increase strategic complaint-based posts.

- 3)

Tone Analysis: If negative sentiment (e.g., strong complaints) generates more engagement, adjust response strategy.

- 4)

Hashtag & Tagging Optimization: Recommend popular hashtags or relevant user tags based on trending engagement patterns.

Adaptive posting strategy includes the following rules. If engagement drops, alter post frequency (e.g., reduce frequency to avoid spamming). If positive engagement increases, prioritize successful content types. Continuous learning and auto-tuning updates weight values wL,wS, wC, wR, and wF, based on real-world outcomes. It also adjusts recommendation logic dynamically based on performance feedback (if new engagement types emerge including video interactions, it incorporate them into scoring).

3. Copilot Architecture

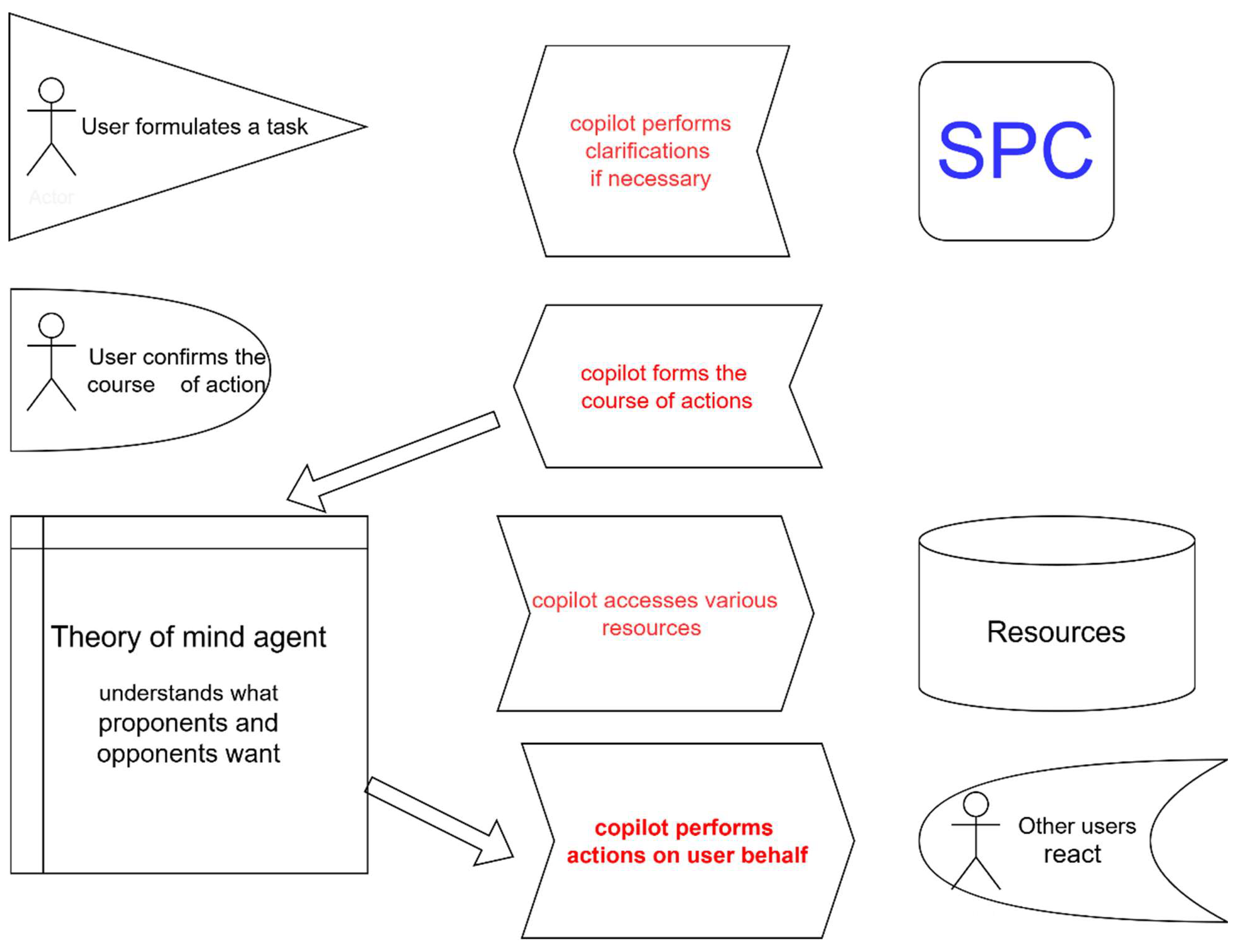

LangGraph is a multi-agent framework that enables structured interactions between AI agents, making it well-suited for building a Social Promotion Copilot. LangGraph enhances the copilot’s capabilities in the following ways (

Figure 5):

- 1)

User Interaction & Task Formulation. A user formulates a promotional task (e.g., “Promote my new product on social media”). LangGraph triggers a multi-agent process to refine the request.

- 2)

Multi-Agent LLM Processing. LangGraph orchestrates different AI agents to process the request. User request enrichment agent analyzes the task and asks follow-up questions (e.g., “What platforms should be targeted?”). User request verification agent ensures clarity and coherence and verifies correctness before execution.

- 3)

Copilot meta-agent (decision maker) determines the best promotional strategy and generates an optimized course of actions. The copilot accesses external resources (e.g., market data, previous campaigns, user preferences) and automates content creation based on the refined user request.

- 4)

The copilot performs action execution and social media automation. It automatically performs actions (e.g., posting content, engaging with users, analyzing responses. Automation tools (e.g., Selenium, APIs) execute the generated promotional tasks.

- 5)

LangGraph optimizes future actions using orchestrator-Worker Agents (for automation execution), evaluator-optimizer for engagement analytics and routing Agents (for personalized content delivery). Copilot also monitors how other users react to posts. It dynamically adjusts engagement strategies (e.g., replying to comments, boosting trending content). Feedback loops ensure continuous improvement.

Hence LangGraph provides a structured agent-based approach for building a Social Promotion Copilot, ensuring efficient task automation, decision-making, and engagement tracking. Its multi-agent design allows for scalability and adaptability, making it an ideal framework for AI-driven social media promotion.

LangGraph utilizes three primary architectural components — Orchestration-Worker, Evaluator-Optimizer, and Routing — to manage and improve complex processes like those involved in social promotion campaigns. Each component has a specific role in ensuring that the system functions efficiently, responds to real-time data, and adapts to user behaviors.

The Orchestration-Worker in LangGraph is the central hub that coordinates the execution of tasks across various agents and platforms. It ensures that the workflow is distributed efficiently and effectively, managing all aspects of content delivery, campaign scheduling, and real-time interactions. This component allows LangGraph to handle multiple processes concurrently.

The Evaluator-Optimizer in LangGraph monitors the performance of various campaigns and adjusts strategies dynamically to ensure that marketing efforts are continually improved. This component uses real-time data to assess the effectiveness of different promotional activities and modifies them to maximize impact. Router is a meta-agent maintaining state transitions.

Selenium is primarily used for web application testing and can be used across various browsers (e.g., Chrome, Firefox, Safari) and platforms. The core component allows interaction with web browsers through programming scripts. In this project we use Selenium to automate scraping and posting on behalf of a user (

Figure 6).

3.1. Enabling SPC with Theory of Mind

SPC can leverage Theory of Mind (ToM, Chapter ??) to enhance its ability to engage with users by modeling their intentions, emotions, and perspectives. By understanding the mental states of different users, SPC can tailor its responses and promotional strategies more effectively.

Adapting to user sentiment: SPC can analyze the emotional tone of conversations and adjust its messaging accordingly. For example, in the complaint domain, it can distinguish between frustrated and indifferent customers, providing empathetic responses to the former while offering neutral or informative replies to the latter.

Predicting reactions and engagement: By retrospection and modeling how users are likely to respond to different types of posts (e.g., complaints, promotions, or discussions), SPC can optimize content to maximize engagement. For instance, it can anticipate that a strongly worded complaint might trigger a viral discussion and adjust its phrasing to align with user sentiment.

Personalized interaction strategies: instead of using generic responses, SPC can infer a user’s intent behind interactions (e.g., whether they seek resolution, validation, or public attention) and tailor replies accordingly. For instance, if a user frequently engages in debates, SPC might respond with thought-provoking questions rather than straightforward solutions.

Social dynamics awareness: in multi-user interactions, SPC can predict social influences, such as how a user’s opinion might shift based on peer reactions. This allows it to strategically time responses or escalate issues when it detects growing dissatisfaction among a user group.

Handling ambiguity and humor: ToM enables SPC to better interpret sarcasm, irony, and cultural nuances in user interactions, reducing the risk of miscommunication. This is especially useful in social platforms where humor and indirect complaints are common.

By incorporating Theory of Mind, SPC evolves from a rule-based automation tool into an adaptive, socially intelligent agent capable of engaging users in a way that feels natural, persuasive, and emotionally aware.

3.2. Run-Time Execution of a Textual Task

Another essential feature of SPC to assure its flexibility is to generate necessary code on the fly and execute it. This is illustrated by the following example:

- 1)

The user inputs a task description (e.g., “Generate a function that calculates Fibonacci numbers”).

- 2)

The script queries an LLM to generate Python code.

- 3)

It prints the generated code.

- 4)

It executes the generated code using exec().

def generate_code(task_description):

"“““

Uses an LLM to generate Python code based on a textual task description.

"“““

prompt = f”Write a Python script that accomplishes the following task:\n{task_description}\n\nOnly provide the code without explanations.”

response = openai.ChatCompletion.create(

model=“gpt-4”, # Use GPT-4 or another available model

messages=[{“role”: “user”, “content”: prompt}],

temperature=0.2

)

code = response[“choices”][0][“message”][“content”]

return code

def execute_code(code):

"“““

Executes the generated Python code safely.

"“““

try:

exec_globals = {}

exec(code, exec_globals)

except Exception as e:

print(“Error executing code:”, e)

if __name__ == “__main__”:

task_description = input(“Describe the coding task: “)

generated_code = generate_code(task_description)

print(“\nGenerated Code:\n”, generated_code)

print(“\nExecuting Code...\n”)

execute_code(generated_code) |

The steps are as follows:

- 1)

Copilot inputs a task description (e.g., “Generate Selenium code to do authentication and submit a complaint via form”).

- 2)

The script queries an LLM to generate Python code.

- 3)

It executes the generated code using exec().

The generated code for SPC included the script to perform certain actions on a web form (

Table 1)

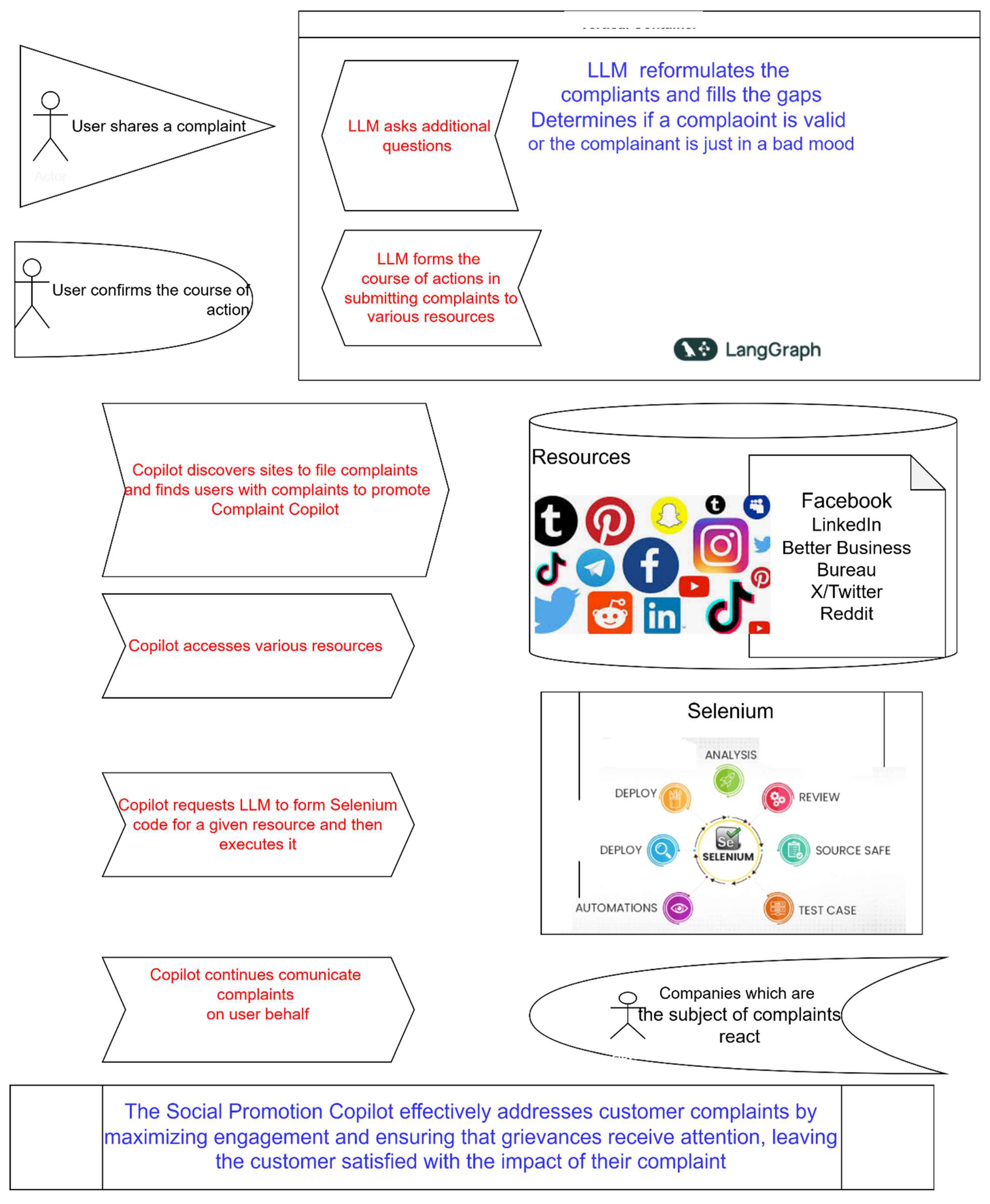

4. Use Case: Complain Copilot

The Complaint Copilot is an intelligent system designed to assist users in filing complaints efficiently. It helps by analyzing, reformulating, and enhancing complaints while also suggesting further actions and automating complaint submissions across multiple platforms, such as social media and consumer advocacy websites.

The user submits a raw complaint such as, “My internet provider has constant outages, and support is unhelpful”. The system extracts key entities like company name, issue type, location, and service type. The system dynamically generates follow-up questions to gather more details:

o “How long have you experienced these issues?”

o “Have you contacted customer support? If yes, what was their response?”

o “Do you have supporting evidence (screenshots, receipts, chat logs)?”

These questions ensure that the complaint is detailed enough to be effective (

Figure 7)

SPC in complaint mode rewords the complaint into a more formal, persuasive, and legally sound version. It uses LLM-based sentiment analysis to enhance clarity and impact. An example reformulation is as:

- 1)

Original: “My internet provider sucks. It’s always down, and support ignores me.”

- 2)

Enhanced: “I have been experiencing frequent internet outages with [Provider Name] for the past [X] weeks. Despite multiple attempts to contact customer support, my issue remains unresolved. This has significantly impacted my work and daily life. I request immediate intervention and a resolution.”

Based on the complaint type, the system suggests next actions, such as:

- 1)

Filing a complaint with regulatory authorities (e.g., FCC, Ombudsman).

- 2)

Contacting consumer protection organizations.

- 3)

Seeking compensation (e.g., refund, discount, service credit).

The advice is customized using LLM-driven recommendations.

Complaint copilot performs auto-posting on social media and consumer advocacy platforms. The enhanced complaint is automatically formatted for posting on:

- 1)

Twitter/X, Facebook, Instagram, Reddit – for public awareness.

- 2)

Consumer advocacy sites (e.g., Trustpilot, BBB, Ripoff Report).

- 3)

Company complaint portals (e.g., “Submit a complaint” pages).

Complaint copilot retrieves company-specific contact handles (e.g., @CompanySupport) and inserts them into posts for maximum visibility.

Complaint copilot leverages LLM-powered NLP – Text analysis, question generation, complaint enhancement, API Integrations that performs Social media posting (X/Twitter, Facebook API), consumer complaint portals, sentiment and intent Detection – to improve phrasing and impact. Moreover, complaint copilot uses Automation Scripts – Auto-filling complaint forms on advocacy websites.

Example Flow in Action:

| User Input: |

| “My flight was canceled last minute, and the airline refused a refund. What should I do?” |

| Complaint Copilot Workflow: |

-

Follow-up questions:

- ○

“Which airline was it?” - ○

“Do you have proof of cancellation?” - ○

“Did they offer an alternative flight?” - ○

“Are you requesting a refund or compensation?”

-

Reformulated Complaint:

- ○

“I booked a flight with [Airline] on [Date], but it was canceled at the last minute. The airline has refused to issue a refund despite my request. According to aviation regulations, I am entitled to compensation. I seek immediate resolution and reimbursement.”

-

- ○

“File a complaint with the airline’s dispute resolution team.” - ○

“Report the issue to the Department of Transportation or Air Passenger Rights agency.” - ○

“If unresolved, escalate to a consumer protection body.”

-

Automated Posting:

- ○

Twitter post: “@Airline, my flight was canceled, and I was denied a refund. As per regulations, I am entitled to compensation. Please resolve this immediately! #CustomerRights #FlightCancellation” - ○

Complaint submitted on Trustpilot & BBB.

|

The architecture of the Complaint Copilot based on Selenium consists of multiple components working together to automate the complaint submission process across various platforms (

Figure 10). Through a user interaction layer, a user shares a complaint. An LLM processes the Complaint, reformulates the complaint and fills in missing details. Also, the LLM determines whether the complaint is valid or just an emotional reaction, asking additional questions to refine the complaint. The user confirms the course of action.

Complaint Copilot (Automation Layer) makes the discovery, identifying relevant sites where complaints can be filed. It also discovers users with complaints to promote the Complaint Copilot service. The Copilot accesses various complaint submission resources, including social Media (Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter/X, Reddit, Instagram, TikTok ) and consumer protection sites: Better Business Bureau, official company support forums, etc.

Under automated complaint filing using Selenium, the Copilot requests the LLM to generate Selenium scripts for automated complaint submission on different platforms. Selenium executes the generated scripts, automating complaint postings across multiple resources. The engagement is continuous: the Copilot monitors responses and continues communication on behalf of the user. It tracks reactions from companies and updates users.

The Copilot uses Selenium for web automation, including automating form submissions, navigating different platforms and handling authentication if necessary. Hence the Selenium engine supports complaint submission, review, and tracking.

Companies may react to complaints submitted by the Copilot. The system tracks responses and informs the user of updates. If needed, the Copilot can generate follow-up responses.

This architecture leverages LLMs for complaint refinement and decision-making, while Selenium handles automation of complaint submission across multiple platforms. The combination allows for an efficient and scalable way to manage consumer complaints, ensuring that they are effectively submitted and followed up.

5. Marketing Strategies

Many marketing efforts focus on promotional activities that support the launch of new products, playing a crucial role in the early stages of the product life cycle. The success of these promotions significantly influences the diffusion and adoption of new products in competitive markets (Delre et al 2007). With the rise of artificial intelligence and automation, social promotion copilots — AI-driven assistants designed to optimize and execute promotional strategies across digital platforms—offer a transformative approach to enhancing product visibility and consumer engagement.

This chapter extends traditional promotional strategy models by integrating an agent-based simulation of a Social Promotion Copilot that automates and personalizes social media interactions, content distribution, and influencer engagement to optimize product launches. The model investigates the efficacy of SPC-driven promotional strategies by focusing on three key aspects: targeting, timing, and adaptive engagement.

Simulation experiments indicate that AI-assisted promotional activities significantly impact diffusion dynamics, amplifying both reach and engagement. The findings highlight that:

The absence of promotional support and/or improper timing can lead to product diffusion failure. AI-powered copilots can mitigate this risk by dynamically adjusting promotion schedules based on real-time consumer sentiment, trends, and engagement metrics.

The optimal targeting strategy involves addressing distant, small, and cohesive consumer groups. The copilot leverage machine learning to identify micro-communities within social networks, tailoring messages to resonate with their specific interests and behaviors.

The optimal timing for promotions varies by product category, particularly between durable goods (e.g., home appliances) and consumer electronics. AI-enhanced strategies can refine timing by analyzing historical data, seasonality trends, and consumer readiness indicators.

Beyond these findings, the integration of the Copilot introduces continuous learning and adaptive engagement, allowing brands to refine their promotional strategies dynamically (Figure 11). By utilizing natural language processing, sentiment analysis, and reinforcement learning, the Copilot can craft personalized responses, automate influencer collaborations, and enhance social proof mechanisms—further accelerating product diffusion.

This research contributes to the planning and management of AI-enhanced promotional strategies, demonstrating how Copilots can revolutionize product launch campaigns by maximizing efficiency, engagement, and long-term adoption rates.

5.1. Diffusion of New Products

SPC can play a crucial role in supporting and accelerating product diffusion throughout the entire S-shaped adoption curve (

Figure 13) by leveraging AI-driven strategies that optimize both external and internal influences on consumer behavior.

In the early phase, when sales are slow and external influences dominate, SPC can enhance traditional promotional activities by identifying and targeting early adopters more effectively. Using advanced predictive analytics and sentiment analysis, SPC can pinpoint potential buyers based on online behavior, interests, and engagement history. It can also automate personalized outreach, manage influencer collaborations, and optimize ad placements across social media platforms to ensure the right audience is exposed to the product at the right moment.

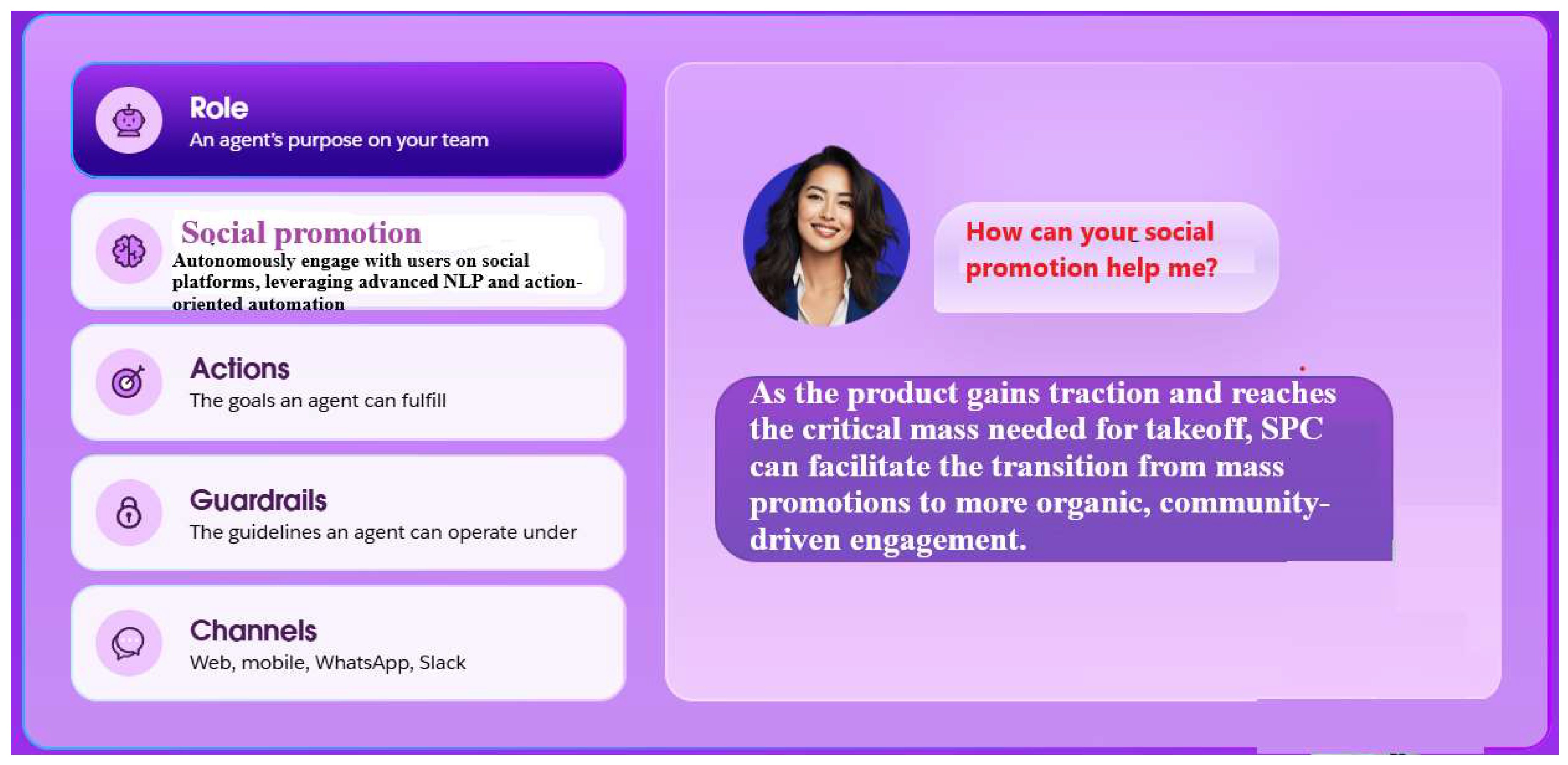

As the product gains traction and reaches the critical mass needed for takeoff, SPC can facilitate the transition from mass promotions to more organic, community-driven engagement. By continuously analyzing consumer interactions, it can refine messaging to amplify word-of-mouth marketing and social contagion effects. SPC can also monitor customer feedback in real-time, enabling businesses to quickly adjust strategies, resolve concerns, and boost positive sentiment, which further accelerates adoption.

In the mature phase, where internal influences become dominant, SPC can sustain engagement by curating user-generated content, encouraging reviews and testimonials, and maintaining brand presence through personalized interactions. By automating customer follow-ups and loyalty campaigns, it helps maximize long-term retention while identifying opportunities for cross-selling and up-selling.

Ultimately, the Copilot enhances the efficiency of each phase of product diffusion by ensuring seamless coordination between promotional efforts, customer engagement, and organic adoption trends. This AI-driven approach minimizes wasted marketing spend, shortens the time to critical mass, and maximizes the overall impact of a product launch.

5.2. Business-to-Consumer and Business-to-Business settings of SPC

SPC operates differently in Business-to-Consumer (B2C) and Business-to-Business (B2B) settings, adapting its strategies to suit the distinct characteristics of each market.

In a B2C environment, SPC focuses on high-volume, emotion-driven, and fast-paced interactions with individual consumers. The copilot uses AI-powered personalization, real-time engagement, and automation to maximize outreach and drive conversions.

Personalized Marketing at Scale: SPC analyzes consumer data, behaviors, and preferences to deliver highly targeted ads, product recommendations, and promotional messages. For example, it can send personalized discounts to consumers who have shown interest in a product but haven’t made a purchase.

Social Media Engagement: SPC automates interactions on platforms like Instagram, TikTok, and Facebook by commenting, liking, and engaging with potential customers, fostering brand visibility. It also monitors trends and viral content to adjust marketing strategies dynamically.

Influencer and WOM Amplification: SPC identifies key influencers and brand advocates to encourage product endorsements and reviews, amplifying word-of-mouth marketing.

Automated Customer Support & Retention: Through AI-powered chatbots and automated messaging, SPC answers FAQs, processes orders, and provides personalized follow-ups, increasing brand loyalty and repeat purchases.

In B2B markets, where sales cycles are longer and decision-making involves multiple stakeholders, SPC acts as a relationship-building and lead-nurturing assistant. Instead of mass outreach, it focuses on high-value engagement, trust-building, and decision support.

AI-Driven Lead Qualification: SPC analyzes potential leads’ online behavior, company size, and engagement with marketing materials to prioritize high-quality prospects, ensuring sales teams focus on the most promising opportunities.

Automated Outreach & Content Personalization: SPC crafts personalized email sequences, LinkedIn messages, and follow-ups tailored to different stakeholders in the decision-making process, ensuring continued engagement.

Thought Leadership & Brand Positioning: SPC automates content distribution by posting whitepapers, case studies, and industry insights on LinkedIn, Twitter, and professional forums, establishing the company as an authority in its field.

CRM Integration & Sales Support: By integrating with Customer Relationship Management (CRM) systems, SPC ensures seamless tracking of interactions, sends reminders for follow-ups, and provides insights into when and how to engage with leads.

Event and Webinar Engagement: SPC can automate invitations, reminders, and post-event follow-ups, ensuring that businesses maximize attendance and engagement in virtual or physical networking events.

Key Differences in SPC’s Role for B2C vs. B2B are shown in

Table 2.

Hence the Copilot adapts to the unique dynamics of B2C and B2B markets by optimizing engagement strategies for each setting. In B2C, it focuses on personalization, automation, and viral reach to drive consumer purchases. In B2B, it prioritizes lead nurturing, trust-building, and long-term relationship management. By leveraging AI, SPC ensures that businesses, regardless of their market type, achieve more efficient, data-driven, and impactful promotional efforts.

6. Evaluation

6.1. Datasets

Zhou et al (2023) developed WebArena, a realistic and reproducible environment for training and evaluating language-guided agents, with a particular focus on web-based task execution. The environment is designed to simulate real-world internet interactions, enabling agents to navigate and perform tasks across fully functional websites spanning four common domains: e-commerce, social forum discussions, collaborative software development, and content management. In our evaluation, we focus on social forum discussions.

To emulate human problem-solving, WebArena also embeds tools and knowledge resources as independent websites. WebArena introduces a benchmark on interpreting high-level realistic natural language command to concrete web-based interactions (

Figure 14).

To enhance the authenticity of task-solving, the environment incorporates interactive tools such as maps, calendars, and search functions, as well as external knowledge bases like user manuals, FAQs, and structured datasets. These resources enable agents to engage in complex, multi-step reasoning processes akin to human decision-making on the web.

We rely on Zhou et al (2023)’s benchmark suite designed to rigorously evaluate an agent’s ability to complete web-based tasks with functional correctness. This benchmark includes diverse, long-horizon tasks that reflect real-world internet usage, such as searching for products, posting on discussion forums, navigating collaborative coding platforms, and managing digital content. These tasks assess not only task completion accuracy but also an agent’s ability to adapt, plan, and interact effectively with dynamic web interfaces. We reduced the set of tasks to the ones related to social promotion (

Figure 15).

WebVoyager, introduced by He et al. (2024), is an advanced web-browsing agent designed to autonomously navigate the internet in response to human-formulated web activity tasks. Unlike SPC, which may involve information sharing, WebVoyager strictly focuses on retrieving information without contributing content. The system operates by analyzing screenshots and text-based elements on web pages, including the type and content of various interface components. At each step, it determines the most suitable action to take, ensuring efficient task completion. Once the objective is achieved, the retrieved information is returned to the user. For instance, WebVoyager can execute a request such as “Find a housewife social group and identify an appropriate post to reply to,” demonstrating its ability to process complex, open-ended tasks.

He et al. (2024) create a benchmark composed of real-world tasks sourced from fifteen widely used websites, including social platforms. This benchmark provides a structured way to assess the system’s capabilities in realistic browsing scenarios. Additionally, they propose an automatic evaluation protocol that leverages the multi-modal understanding abilities of visual LLMs. This protocol enables a more comprehensive assessment of open-ended web agents by measuring their ability to interpret and interact with web environments.

6.2. Assessment of Auto Web Browsing

We conduct an evaluation of the web-browsing capabilities of SPC using data from WebArena and WebVoyager, focusing on both full datasets and specific subsets related to social websites. To provide a comprehensive comparison, we assess the performance of SPC against various benchmarks, including human performance, GPT-3 with Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting in the WebArena setting, GPT-4 in a similar environment, and Operator. Our evaluation considers two versions of SPC: the default version and an enhanced variant equipped with Theory of Mind capabilities (section 3.1). The results of our evaluation are summarized in

Table 3, highlighting SPC’s relative strengths and weaknesses in different browsing contexts.

Our findings reveal that SPC underperforms across all three full datasets within our evaluation framework, indicating that it struggles to compete with other models in general web-browsing tasks. However, when analyzing the social website subsets from WebArena and WebVoyager, SPC demonstrates a notable advantage. Specifically, it surpasses the performance of all competing systems—including WebVoyager and Operator—on GitHub and AllRecipes tasks within these subsets. This suggests that SPC’s strengths may be more pronounced in environments where social interaction or community-driven content is central, even if it falls short in broader web navigation tasks.

A key factor contributing to SPC’s success in social-oriented datasets is its unique ability to engage in posting, rather than merely gathering information. Unlike WebArena, WebVoyager, and Operator—which primarily focus on retrieving data—SPC actively participates in online discourse, making it more adaptable in settings that require user interaction. On average, SPC+ToM outperforms both WebVoyager and Operator by approximately 6%, further reinforcing the idea that its Theory of Mind-enhanced capabilities provide an edge in tasks involving social reasoning and engagement. This distinction underscores SPC’s potential for applications where not only information retrieval but also meaningful interaction is necessary.

6.3. End-to-End Evaluation of Social Promotion Copilot

Evaluating the effectiveness of a Social Promotion Copilot (SPC) requires a comprehensive analysis of various performance metrics, ranging from user engagement levels to the overall impact of its promotional strategies. One key aspect of this evaluation involves measuring how frequently users interact with SPC-managed posts, including likes, shares, comments, replies, and friend or colleague requests. By analyzing these interactions, we can assess the extent to which SPC successfully engages with online communities. Our study includes an examination of 100 posts across multiple social websites, with the detailed results presented in

Table 4. This analysis allows us to identify platform-specific trends in user behavior, offering insights into how SPC’s promotional strategies perform in different social media environments.

The results indicate that Facebook users exhibit a strong reaction to SPC-generated complaint posts, with an unusually high number of friend requests. This suggests that dissatisfied customers are highly engaged when SPC posts content addressing consumer grievances, particularly when it provides actionable steps for resolving issues with customer service. The ability of SPC to facilitate such discussions appears to resonate with users, driving higher engagement. On VKontakte, while there is still a noticeable level of social interaction, the absence of direct customer support participation results in significantly lower engagement numbers compared to Facebook. The difference highlights the impact of customer service responsiveness on user interactions, suggesting that platforms with more active brand engagement foster greater SPC-driven social activity.

In contrast, LinkedIn demonstrates a more restrained response to SPC activity. Although likes and shares remain comparable to other platforms, replies to posts and colleague requests are markedly lower, particularly for negative posts. This trend reflects LinkedIn’s professional nature, where users tend to engage less with complaints and controversy compared to more socially oriented platforms.

To distinguish SPC-generated posts from organic, manually crafted content, we provide relative engagement metrics in

Table 5, computed as SPC-to-genuine posting percentages where data is available. Overall, SPC posts generate 14% less engagement compared to genuine human posts. This indicates that while users generally respond to SPC activity in a similar manner to human-created content, there is still a slight engagement gap, suggesting potential areas for improvement in making SPC’s interactions more authentic and compelling.

7. Related Work

Galitsky et al (2014) introduced a simulated human-like agent designed to act on behalf of its human host, facilitating and managing online communication. This agent alleviates its host from routine and less critical social networking activities, such as sharing news, commenting on messages, blogs, forums, images, and videos. Unlike many applications of simulated human characters, the agent’s social interactions occur without necessarily revealing its automated nature to conversation partners. It engages in the exchange of news, opinions, and updates as if it were the human host. This system was names Conversational Agent for Social Promotion (CASP). To evaluate CASP’s effectiveness and trustworthiness, we conducted experiments across multiple Facebook accounts, analyzing its performance in fostering engagement and facilitating seamless human-like interactions.

In today’s digital era, social media platforms like Facebook, LinkedIn, Instagram, and X have expanded users’ networks far beyond close friends and family. On average, individuals maintain connections with hundreds or even thousands of contacts across these platforms. However, despite the vastness of these networks, active engagement remains limited to a small circle—typically 10-20 close friends, family members, and colleagues. The majority of connections receive little to no interaction, leading to the perception that these relationships have been neglected or abandoned.

Yet, maintaining a broader and more active social presence is increasingly valuable for both personal and professional growth. Whether for career networking, personal branding, or community engagement, users are expected to demonstrate interest in their connections by responding to posts, acknowledging life events, and actively participating in discussions. However, the sheer volume of interactions required to sustain these relationships demands significant time and effort—something many users struggle to manage.

To bridge this gap, intelligent automation, such as CASP, can assist users by handling routine social interactions (

Figure 16). While users continue to engage personally with close friends and family, CASP can maintain communication with wider networks by liking, sharing, and commenting on posts in a meaningful and contextually appropriate manner. By automating aspects of social interaction, CASP helps users sustain a consistent and engaged online presence without the overwhelming time commitment, ensuring that professional and social relationships remain active and beneficial.

To enhance the legacy CASP system, modern LLMs and related AI technologies significantly improve its capabilities in personalization, contextual understanding, and automation. Here are some key technologies that would enhance CASP today:

- 1)

Transformer-Based LLMs (e.g., GPT-4, Claude, Gemini, Mistral) improve context awareness, processing long conversations, understanding nuances in social interactions, and generating contextually appropriate responses. These LLMs can adapt to a user’s communication style by learning from past interactions (Galitsky 2025).

- 2)

Use of Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) would enhanced relevance: by integrating real-time information retrieval, CASP can generate responses based on recent news, trends, or user-specific data. Also, leveraging personalized knowledge base, CASP would be able to maintain a dynamic memory of a user’s preferences, conversation history, and past engagements.

- 3)

Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback would assure better engagement optimization: CASP can be trained with human feedback to ensure responses align with user intent, avoiding robotic or inappropriate messaging. It would also assure ethical and safe communication, preventing generating controversial or insensitive responses that could harm relationships (Bai et al 2022).

- 4)

Fine-Tuned Social AI Models (e.g., Llama 3, Mixtral) provide context-specific adaptation (Bakker et al 2022, Yin et al 2024). By fine-tuning models on social media data, CASP can generate responses that align with social norms and platform-specific etiquette. The emotional intelligence is essential as well: CASP can be trained to detect emotional tones in posts and respond empathetically.

- 5)

Role-specific agents can be a foundation of different AI modules that handle various aspects of social promotion—one for casual interactions (

Figure 17), another for professional networking, and one for content recommendation. Using AI planning models (like AutoGPT or BabyAGI), CASP can decide when to engage and when to remain passive.

Future Potential Enhancements include LLM-powered auto-generated posts & replies: CASP could draft meaningful social media posts based on a user’s interests, past interactions, and trending topics. Emotion and sentiment-based responses can be achieved based on the sentiment detected in messages, ensuring a more natural and engaging interaction. As virtual spaces grow, CASP could extend to managing interactions in 3D social environments. By leveraging these advancements, CASP can evolve into an intelligent social assistant that maintains a user’s digital presence seamlessly while ensuring meaningful and context-aware interactions.

7.1. Empowering Social Media Engagement

Teens and content creators often struggle to effectively promote positive messages and engage meaningfully on social media. One promising approach is to empower users with AI-driven assistance to enhance engagement strategies and cultivate supportive online communities. While numerous social media automation tools exist, little research has explored designing chatbots that provide contextualized, real-time guidance for improving online interactions.

This study involved social media users and digital marketers in two design sessions: (1) an in-depth interview to identify challenges in effective promotion and audience engagement, and (2) interaction with the SPC prototype to develop design guidelines for overcoming these challenges. Qualitative analysis of these interactions revealed three primary barriers to successful social media promotion:

1) Lack of strategic knowledge about platform algorithms, audience preferences, and engagement techniques.

2) Emotional barriers, such as fear of negative feedback, imposter syndrome, or uncertainty in messaging.

3) Limited understanding of audience dynamics, leading to ineffective or misaligned messaging.

Key parameters were identified to optimize chatbot responses and support effective promotion, including:

1) Adopting multiple personas to simulate diverse audience perspectives.

2) Using an engaging, friendly, and supportive tone to encourage confidence.

3) Providing clear, specific, and adaptable suggestions for different platforms and audiences.

4) Optimizing message length and format for each platform’s best practices.

These insights inform the design of personalized and scalable AI-driven tools that empower users to enhance social media engagement, foster positive interactions, and amplify meaningful content effectively.

Brik et al (2024) illustrate the merits, potentials, and limitations of using ChatGPT as a co-pilot to assist faculty in refining the assessment design process. This research brings into evidence the importance of keeping a ‘human in the loop’ perspective during the faculty-ChatGPT assessment co-creation activities (

Figure 18)

7.2. Retail Copilot

Building a successful AI copilot involves a comprehensive and systematic approach, ensuring both technical excellence and alignment with user needs.. To illustrate the practical application of these concepts, (Furmakiewicz et al 2024) uses a case study of Microsoft’s development of copilot templates within the retail domain, highlighting the significance of each design component. Additionally to LLM, the authors examine the role of plugins, which enable the copilot to retrieve knowledge and execute actions, enhancing its functionality. Orchestration, which ensures seamless coordination between components, is also discussed, along with system prompts that guide the copilot’s behavior. Furthermore, responsible AI guardrails are explored, emphasizing the importance of fairness, transparency, and safety in AI systems.

Testing and evaluation are the keys to ensuring the AI copilot meets its objectives and avoids unintended negative outcomes in real-world applications. This includes the use of an end-to-end human-AI decision loop framework, which offers a structured approach for assessing how the copilot interacts with users and impacts business processes. Furmakiewicz et al 2024 discuss methods for measuring and improving both the quality and safety of the copilot, ensuring it is reliable, effective, and aligned with ethical standards.

By providing a detailed examination of both the design and evaluation stages, this paper offers concrete insights into the anatomy of an AI copilot. It underscores the importance of thoughtful design practices and robust testing methodologies in building AI assistants that are not only technologically advanced but also human-centered, ethical, and capable of driving positive outcomes in business contexts.

7.3. Github Copilot

GitHub Copilot is an AI-powered code completion tool developed by GitHub in collaboration with OpenAI. It acts as an intelligent assistant that helps software developers write code faster and more efficiently by suggesting relevant code snippets, functions, and even entire lines of code based on the context of the project. Built on OpenAI’s Codex model, GitHub Copilot is trained on a vast array of publicly available programming resources, including open-source projects, which enables it to provide relevant, context-aware suggestions across various programming languages. This makes Copilot a powerful tool for both experienced developers and beginners, offering real-time coding assistance and reducing the need to search for solutions or consult documentation.

One of GitHub Copilot’s most notable features is its ability to generate code based on simple comments or descriptions written by the developer. For instance, by typing a comment outlining the desired functionality of a specific function, Copilot can generate a functional implementation in the chosen programming language. This makes it especially valuable for streamlining the development process, as it reduces the time spent on routine coding tasks. Additionally, Copilot supports multiple languages and frameworks, making it versatile for a wide range of development projects, from web development to machine learning.

Despite its potential, GitHub Copilot also raises important questions about intellectual property, ethics, and dependency on AI in software development. Since Copilot is trained on publicly available code, concerns have emerged about the tool inadvertently suggesting copyrighted or non-original code without proper attribution. GitHub has introduced some guardrails to address these concerns, such as disclaimers about code reuse and safeguards to prevent inappropriate suggestions. Furthermore, while Copilot helps accelerate development, it is important for developers to maintain a critical eye and not rely solely on AI-generated code without verifying its accuracy and suitability for the intended project. As AI tools like GitHub Copilot continue to evolve, their role in software development will likely grow, prompting ongoing discussions about best practices and responsible usage.

7.4. Salesforce’s Agentforce

Agentforce is a proactive, autonomous AI application that provides specialized, always-on support to employees or customers. Agentforce can be enabled with any necessary business knowledge to execute tasks according to its specific role.

SPC and Salesforce’s AgentForce both focus on AI-driven automation for online interactions, but they differ in scope and application. They are designed to enhance user engagement and response management. Each system aims to improve efficiency and effectiveness in online communication.

However, AgentForce primarily designed for customer service automation within the Salesforce ecosystem. It acts as an AI-powered agent to handle customer inquiries, automate workflows, and assist human agents. It is also integrated deeply with CRM systems to optimize sales, service, and support processes.

While SPC focuses on social engagement and marketing, AgentForce is tailored for enterprise-level customer support and CRM automation (

Figure 19). However, an advanced SPC could potentially integrate with systems like AgentForce to bridge social media engagement with customer relationship management (CRM,

Figure 20), creating a seamless flow from online interactions to sales and support pipelines.

7.5. Uncanny Valley and Social Actors paradigms

The Uncanny Valley hypothesis (Mori et al 2012) suggests that as a robot or virtual agent becomes more human-like, people tend to feel increasingly comfortable with it—until a certain threshold is reached. At this point, slight imperfections in realism create an eerie, unsettling feeling, leading to negative emotional reactions (

Figure 21). This dip in emotional response is referred to as the “Uncanny Valley.” However, as realism continues to improve beyond this valley, human acceptance increases again. Human-like virtual influencers may fall into the Uncanny Valley if their appearance and behavior are almost, but not quite, human, leading to lower engagement and discomfort among users. For example, a cartoonish robot may feel friendly and non-threatening, but a highly realistic android with unnatural facial expressions or slightly stiff movements can feel unsettling.

The Computers Are Social Actors paradigm (Reeves and Nass 1996), suggests that humans naturally apply social rules and expectations to computers, AI, and virtual agents, even when they know they are interacting with a machine. People subconsciously treat digital entities as if they have personalities, emotions, and social roles, responding with politeness, social norms, and biases similar to those in human-to-human interactions. If users unconsciously treat virtual influencers as social beings, their expectations for natural behavior and emotional authenticity may shape their reactions. This could lead to differences in engagement and trust between human-like and non-human-like virtual agents. Users might say “thank you” to a virtual assistant like Siri or Alexa, or feel frustrated when a chatbot provides an unhelpful response.

7.6. OpenAI Operator

OpenAI’s Operator is an advanced AI agent capable of autonomously navigating the web and performing tasks on behalf of users. Unlike traditional automation tools that rely on predefined scripts or APIs, Operator interacts with websites just as a human would—by typing, clicking, and scrolling within a browser. This enables it to handle a variety of online tasks, from filling out web forms and ordering medicines to posting on social media and making reservations.

As one of the first fully autonomous AI agents developed by OpenAI, Operator represents a major leap in AI-driven automation, allowing users to delegate repetitive digital work efficiently. By using the same interfaces and tools that humans engage with daily, Operator enhances productivity and unlocks new opportunities for businesses looking to streamline customer interactions, online operations, and digital workflows.

At the core of Operator lies CUA (

Computer User Agent), a multimodal AI model that combines GPT-4o’s vision capabilities with advanced reasoning through reinforcement learning. Unlike traditional automation systems that depend on OS- or web-specific APIs, CUA is designed to interact directly with graphical user interfaces (GUIs)—the buttons, menus, text fields, and other elements that make up digital environments (

Figure 22).

By leveraging foundational research in multimodal understanding and structured problem-solving, CUA enables AI to perform complex web-based tasks without requiring specialized integrations. This makes Operator highly adaptable, self-correcting, and capable of handling real-world digital environments with ease.

Operator follows a three-step process that allows it to perceive its environment, reason through tasks, and execute actions in real time:

- 1)

Perception: Operator continuously captures and analyzes screenshots of the web page it is interacting with, using computer vision to understand the current state of the interface.

- 2)

Reasoning: Using chain-of-thought reasoning, Operator determines the most effective next steps by analyzing past and present interactions. This inner monologue enables it to plan multi-step tasks, recognize obstacles, and make dynamic adjustments.

- 3)

Action: Operator clicks, scrolls, types, and interacts with the page as needed, progressing toward task completion. For sensitive actions—such as entering login credentials or solving CAPTCHAs—it requests user confirmation to ensure security and privacy.

This iterative loop of perception, reasoning, and action allows Operator to handle a wide range of digital workflows, including:

1) Form Filling – Completing online applications, registrations, and checkouts.

2) Data Entry & Extraction – Collecting, copying, and organizing online information.

3) E-commerce Transactions – Searching for products, comparing prices, and placing orders.

4) Content Interaction – Posting updates, commenting, and engaging on social media.

5) Customer Support Assistance – Navigating FAQ pages, submitting tickets, and retrieving information.

An advantage of Operator over SPC lies in its advanced visual analysis capabilities, allowing it to interpret and interact with graphical user interfaces (GUIs) more effectively. By leveraging OpenAI’s multimodal models, Operator can process complex web layouts, recognize patterns in visual data, and navigate websites with human-like precision. This makes it highly suitable for tasks that require an understanding of dynamic elements, such as interactive dashboards, media-heavy web pages, and forms with evolving structures. However, while Operator excels in raw functional automation, it lacks social and psychological adaptability. It is not specifically designed to engage with the nuances of social interactions, interpret sentiment, or perform tasks that require an understanding of human emotions and social cues, which are crucial for meaningful participation in social networks and community-driven discussions.

Another key limitation of Operator is its restricted functionality in adversarial or competitive online environments. Many platforms, especially social media websites, actively work to prevent automated engagement, enforcing strict anti-bot measures to ensure authentic user activity. As an OpenAI-managed service, Operator may face resistance from these platforms, potentially leading to restrictions on automated posting or interaction. In contrast, SPC operates at an individual user level, allowing it to seamlessly integrate with personal accounts without triggering large-scale automated detection systems. This decentralized approach makes SPC more resilient in maintaining engagement across social networks, ensuring that users can continue interacting with their communities without disruption. While Operator offers powerful automation, SPC’s ability to blend naturally into social ecosystems makes it the preferred choice for socially driven tasks that require adaptive human-like interaction in competitive or restrictive digital spaces.

Startups such as Browserbase and Browser Use are actively contributing to the rapidly expanding field of browser-using AI agents, leveraging their proprietary technology to develop and open-source advanced automation tools. By making their agents publicly available, these companies aim to democratize access to AI-driven web interaction, enabling developers, researchers, and businesses to integrate intelligent browsing capabilities into their own applications.

These open-source browser-using agents are designed to navigate, interact with, and extract information from the web autonomously, mimicking human behavior while optimizing efficiency. They support a wide range of use cases, including automated form filling, web scraping, and real-time data analysis, making them valuable assets for industries reliant on digital automation. By fostering an open ecosystem, startups like Browserbase and Browser Use are helping to drive innovation in human-computer interaction, paving the way for more intelligent, adaptable, and scalable AI-powered browsing solutions (Cunningham et al 2025).

7.7. Interactive LLM-Based Agents

In the field of interactive decision-making agents, researchers have explored various approaches to enhancing AI’s ability to navigate and perform tasks on the web. Nakano et al. (2021) introduced WebGPT, an AI system designed to search the web, process search results, and generate informed responses to user queries. This method leverages LLMs to integrate real-time information retrieval with reasoning capabilities, improving the reliability of AI-generated answers. Building on this idea, Gur et al. (2023) proposed a more action-oriented web agent capable of synthesizing JavaScript code to execute tasks autonomously. This advancement allows AI agents to interact dynamically with web applications, expanding their functionality beyond simple information retrieval to direct task execution within browser environments.

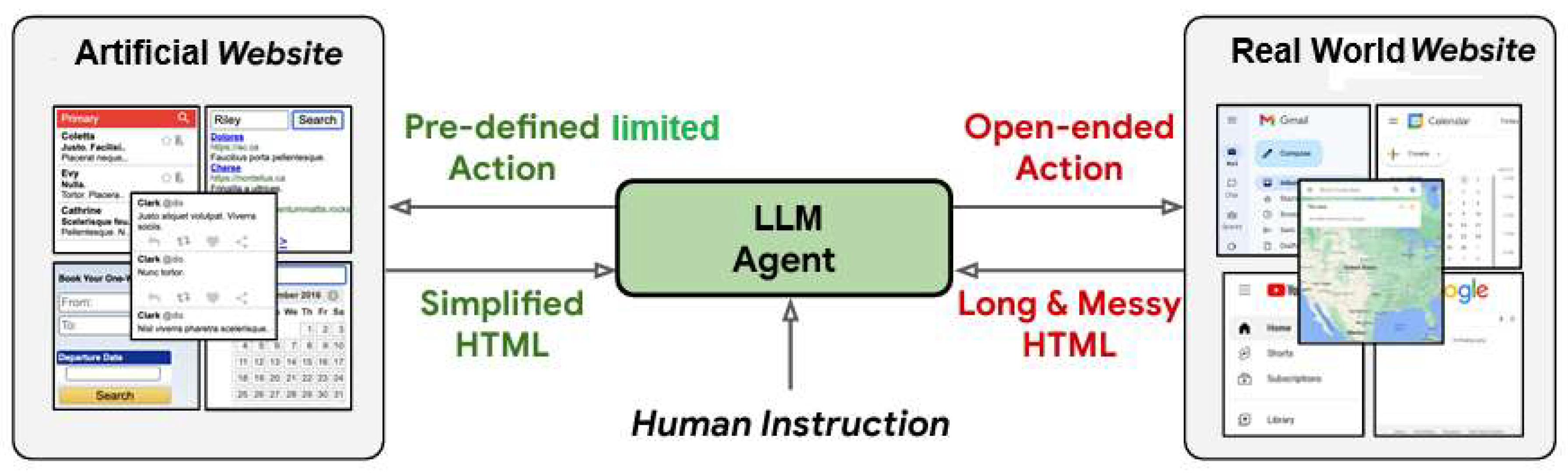

Recent advancements in language model agents have enabled AI systems to navigate and interact with simulated websites effectively (Furuta et al., 2023) These simulated environments, such as MiniWoB (Yao et al., 2022), provide agents with structured, predefined actions and simplified HTML representations, allowing for efficient training and evaluation. By operating in controlled settings where the HTML content is well-structured and noise-free, these agents can successfully complete a variety of web-based tasks, including form-filling, data retrieval, and navigation. However, while these models demonstrate proficiency in constrained environments, their capabilities remain limited when applied to real-world web interactions.

In contrast, real-world websites present significantly greater challenges for language model agents (

Figure 23). Unlike simulated environments, these websites feature dynamic content, interactive elements, and non-standardized structures that complicate AI-driven navigation. Agents must handle open-ended actions, where available choices are not predefined but depend on contextual and situational factors. Moreover, the HTML documents of real-world websites are often lengthy and cluttered with irrelevant data, advertisements, tracking scripts, and dynamically loaded content, making efficient information extraction and action planning more difficult. Overcoming these obstacles requires AI models to develop advanced perception, reasoning, and adaptability, enabling them to process complex, unstructured web environments while maintaining robust and reliable performance in real-world applications.

A significant leap in web-based AI agents has been the incorporation of multi-modal processing, which enables agents to perceive and act on graphical interfaces rather than relying solely on textual representations. Shaw et al. (2023) introduced models that predict user actions based on screenshots of web pages, allowing AI to interact with websites similarly to human users. This approach moves beyond Document Object Model tree-based navigation, which can be limited by dynamically loaded content and evolving web structures. By interpreting visual elements such as buttons, menus, and form fields, these agents demonstrate greater adaptability and robustness, making them more effective for complex and dynamic web tasks.

Successfully performing tasks in interactive digital environments requires agents to develop a range of sophisticated capabilities. These include hierarchical planning, where an agent breaks down tasks into structured sub-goals, state tracking, which enables the system to remember past actions and adjust behavior accordingly, and error recovery, allowing agents to recognize and correct mistakes in real time. As AI continues to evolve in this space, these competencies will be crucial for the development of autonomous web agents capable of seamless interaction, adaptive decision-making, and efficient task completion across a variety of online platforms.

7.8. Other LLM + Action Engines Integration

LaVague (2024) Introduce Web Agent framework for builders. Similar to the current work, it combines LLM and automation tool like Selenium

LaVague is an open-source framework designed for developers who want to create AI Web Agents to automate processes for their end users.

Our Web Agents can take an objective, such as “Print installation steps for Hugging Face’s Diffusers library,” and generate and perform the actions required to achieve the objective.

LaVague Agents are made up of:

- 1)

A world Model that takes an objective and the current state (aka the current web page) and outputs an appropriate set of instructions.

- 2)

An action engine which “compiles” these instructions into action code, e.g., Selenium or Playwright & executes them

8. Conclusions

Complaint copilot:

✔ Saves Time – Automates the tedious process of crafting and submitting complaints.

✔ Enhances Impact – Ensures complaints are well-written and legally sound.

✔ Improves Success Rate – Directs users to the best escalation paths.

✔ Public Pressure – Leverages social media for faster company responses.

As virtual agents become increasingly common across various domains, virtual influencers have emerged on social media platforms, engaging with users and integrating into human networks.

Drawing on research in human-computer interaction, the Uncanny Valley hypothesis, and the Computers Are Social Actors paradigm, Arsenyan and Mirowska (2021) examines:

1) how virtual agents exhibit human-like behavior within social networks, and

2) how users react to human versus virtual agents in publicly visible interactions. Analyzing text and emoji responses to posts made by a human influencer, a human-like virtual influencer, and an anime-style virtual influencer over an 11-month period, we found that the human-like virtual influencer received significantly fewer positive reactions. This supports the Uncanny Valley hypothesis, as additional measures of negative reactions followed a similar trend, despite the generally positive nature of the platform.

Traditional automation tools require custom scripts, pre-configured workflows, or API access, making them rigid and time-consuming to set up. In contrast, Copilot interacts with the web naturally, just like a human user, offering greater flexibility, adaptability, and accessibility.

By leveraging SPC ability to understand web interfaces, Copilot opens doors to a new wave of AI-driven productivity, allowing individuals and businesses to automate time-consuming digital tasks, improve efficiency, and optimize online interactions with minimal effort.

As AI continues to evolve, Copilot represents a crucial step toward autonomous digital assistants, making AI not just an information provider but an active participant in the digital world—capable of executing real tasks, adapting to changing environments, and enhancing human productivity in ways never seen before.

In Jan 2025 OpenAI announces its much-anticipated Operator agent, which uses computer vision capabilities to perform tasks for a user by directly taking over their computer. The underlying model that powers Operator, referred to as the Computer-Using Agent, is a variant of GPT-4o fine-tuned through reinforcement learning to interact with graphical user interfaces. This distinguishes CUA from many conventional AI agents, which are typically confined to text-based interfaces. By enabling interaction with a wide range of computer software in a manner akin to human users, CUA significantly broadens the scope of AI-driven automation. According to OpenAI, CUA achieves state-of-the-art performance on WebArena (Zhou et al 2023) and WebVoyager (He et al 2024), which specifically evaluate AI proficiency in web-based interactions.

Despite the impressive capabilities demonstrated by Operator, OpenAI is a relatively late entrant into the rapidly expanding domain of AI-powered computer agents. Competing models had already been introduced by other research institutions and companies. Anthropic’s Claude Computer Use debuted in October, followed by Google’s Mariner two months later (

Figure 24). The field’s origins can be traced even further back to Adept, a startup that launched its first computer-using agent in 2022. These developments highlight the growing interest in AI-driven automation for software interaction, emphasizing both the competitive landscape and the increasing sophistication of AI agents in this domain.

References

- Akilkhanov A (2024) AI And Personalization In Marketing. Forbes. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/councils/forbescommunicationscouncil/2024/01/05/ai-and-personalization-in-marketing/.

- Arsenyan J, Agata Mirowska. Almost human? A comparative case study on the social media presence of virtual influencers, International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 2021, 155.

- Bakker M, Martin Chadwick, Hannah Sheahan, Michael Tessler, Lucy Campbell-Gillingham, Jan Balaguer, Nat McAleese, Amelia Glaese, John Aslanides, Matt Botvinick, Christopher Summerfield. Fine-tuning language models to find agreement among humans with diverse preferences. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, 35.

- Chiam J, Aloysius Lim, Cheryl Nott, Nicholas Mark, Ankur Teredesai, Sunil Shinde. Co-Pilot for Health: Personalized Algorithmic AI Nudging to Improve Health Outcomes. 2024. arXiv:2401. 2024, arXiv:2401.10816.

- Cunningham M (2025) Operator is OpenAI’s attempt to catch up.

- Delre SA, W. Jager, T.H.A. Bijmolt, M.A. Janssen. Targeting and timing promotional activities: An agent-based model for the takeoff of new products. Journal of Business Research 2007, 60, 826–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eager, B., & Brunton, R. Prompting higher education towards AI-augmented teaching and learning practice. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice 2023, 20. [CrossRef]

- Furmakiewicz M, Chang Liu, Angus Taylor, Ilya Venger. Design and evaluation of AI copilots -- case studies of retail copilot templates. Design and evaluation of AI copilots -- case studies of retail copilot templates. 2024, arXiv:2407.09512.

- Furuta H, Ofir Nachum, Kuang-Huei Lee, Yutaka Matsuo, Shixiang Shane Gu, and Izzeddin Gur. Multimodal web navigation with instruction-finetuned foundation models. arXiv preprint 2305, arXiv:2305.11854.

- Galitsky B, D Ilvovsky, N Lebedeva, Usikov D (2014) Improving trust in automation of social promotion. AAAI Spring Symposium Series, Stanford CA 28-35.

- Galitsky B (2019) A social promotion chatbot. In Developing Enterprise Chatbots. Springer Cham.

- Galitsky B (2021) Artificial Intelligence for Customer Relationship Management: Solving Customer Problems. Springer Cham.

- Galitsky B. Social autonomous agent implementation using lattice queries and relevancy detection. US Patent 11,645,459, 2023.

- Galitsky B (2025) LLM- based Personalized Recommendations in Health. In Health Applications of Neuro-symbolic AI. Elsevier.

- Golder PN, G.J. Tellis. Growing, growing, gone: cascades, diffusion, and turning points in the product life cycle. Marketing Sci 2004, 23, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gur I, Hiroki Furuta, Austin Huang, Mustafa Safdari, Yutaka Matsuo, Douglas Eck, and Aleksandra Faust. A real-world webagent with planning, long context understanding, and program synthesis. arXiv preprint 2023, arXiv:2307.12856.

- He H, Wenlin Yao, Kaixin Ma, Wenhao Yu, Yong Dai, Hongming Zhang, Zhenzhong Lan, Dong Yu. WebVoyager: Building an End-to-End Web Agent with Large Multimodal Models. 2024, arXiv:2401.13919.

- International Journal of Child-Computer Interaction, V 41.

- Its release gives OpenAI a badly-needed boost — but will it be enough to close the gap with rivals like Anthropic? Medium. Available online: https://medium.com/%40mcunningham1440/operator-is-openais-attempt-to-catch-up-68fd61bfb643.

- Journal of Marketing, 43 (1979), pp. 55–68.

- Kai Yin K, Chengkai Liu, Ali Mostafavi, Xia Hu. CrisisSense-LLM: Instruction Fine-Tuned Large Language Model for Multi-label Social Media Text Classification in Disaster Informatics. 2024, arXiv:2406.15477.

- LaVague (2024) LaVague: Web Agent framework for builders. Available online: https://github.com/lavague-ai/LaVague.

- Mahajan V, E. Muller. Innovation diffusion and new product growth models in marketing.

- Mori, M., MacDorman, K. F., & Kageki, N. The Uncanny Valley [From the Field]. IEEE Robotics & Automation Magazine 2012, 19, 98–100.

- Nakano R, Jacob Hilton, Suchir Balaji, Jeff Wu, Long Ouyang, Christina Kim, Christopher Hesse, Shantanu Jain, Vineet Kosaraju, William Saunders, et al. WebGPT: Browser-assisted question-answering with human feedback. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2112.09332.

- OpenAI. ChatGPT: Optimizing language models for dialogue. 2022.

- OpenAI. GPT-4 technical report. arXiv, pp. 2303–08774, 2023.

- PRNewswire (2023) Baidu Unveils ERNIE Bot, the Latest Generative AI Mastering Chinese Language and Multi-Modal Generation. Available online: https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/baidu-unveils-ernie-bot-the-latest-generative-ai-mastering-chinese-language-and-multi-modal-generation-301774240.html.

- Reeves, B. , & Nass, C. (1996). The Media Equation: How People Treat Computers, Television, and New Media Like Real People and Places. Cambridge University Press.

- Shaw P, Mandar Joshi, James Cohan, Jonathan Berant, Panupong Pasupat, Hexiang Hu, Urvashi Khandelwal, Kenton Lee, and Kristina Toutanova. From pixels to ui actions: Learning to follow instructions via graphical user interfaces. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2306.00245.

- Social Media Co-pilot: Designing a chatbot with teens and educators to combat cyberbullying. Media Co-pilot.

- Su, J., & Yang, W.. Unlocking the power of ChatGPT: A framework for applying Generative AI in education. ECNU Review of Education 2023, 6, 355–366. [CrossRef]

- Xu C (2024) Integrating AI Tools into Teaching Practice: Unleash the Potential of Your AI Co-pilot. The Future of Education 14th Edition 2024.

- Yao S, Jeffrey Zhao, Dian Yu, Nan Du, Izhak Shafran, Karthik Narasimhan, and Yuan Cao. React: Synergizing reasoning and acting in language models. arXiv preprint 2022, arXiv:2210.03629.

- Yuntao Bai Y, Andy Jones, Kamal Ndousse, Amanda Askell, Anna Chen, Nova DasSarma, Dawn Drain, Stanislav Fort, Deep Ganguli, Tom Henighan, Nicholas Joseph, Saurav Kadavath, Jackson Kernion, Tom Conerly, Sheer El-Showk, Nelson Elhage, Zac Hatfield-Dodds, Danny Hernandez, Tristan Hume, Scott Johnston, Shauna Kravec, Liane Lovitt, Neel Nanda, Catherine Olsson, Dario Amodei, Tom Brown, Jack Clark, Sam McCandlish, Chris Olah, Ben Mann, Jared Kaplan. Training a Helpful and Harmless Assistant with Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback. 2022, arXiv:2204.05862.

- Zhou S, Frank F. Xu, Hao Zhu, Xuhui Zhou, Robert Lo, Abishek Sridhar, Xianyi Cheng, Tianyue Ou, Yonatan Bisk, Daniel Fried, Uri Alon, Graham Neubig. WebArena: A Realistic Web Environment for Building Autonomous Agents. 2023, arXiv:2307.13854.

- Zou W, Qian Yang, Dominic DiFranzo, Melissa Chen, Winice Hui, Natalie N. Bazarova (2024).

Figure 1.

It is never late to start social promotion.

Figure 1.

It is never late to start social promotion.

Figure 2.

SPC might help with self-confidence.

Figure 2.

SPC might help with self-confidence.

Figure 3.

A high-level view at the Social Promotion Copilot (SPC).

Figure 3.

A high-level view at the Social Promotion Copilot (SPC).

Figure 4.

A patient is ready for his social promotion.

Figure 4.

A patient is ready for his social promotion.

Figure 5.

LangGraph Supports Social Promotion Copilot Architecture.

Figure 5.

LangGraph Supports Social Promotion Copilot Architecture.

Figure 6.

ChatGPT and Selenium (on the top). The job of the web page navigation agent is the hardest (on the bottom).

Figure 6.

ChatGPT and Selenium (on the top). The job of the web page navigation agent is the hardest (on the bottom).

Figure 7.

From compliment to complaint.

Figure 7.

From compliment to complaint.

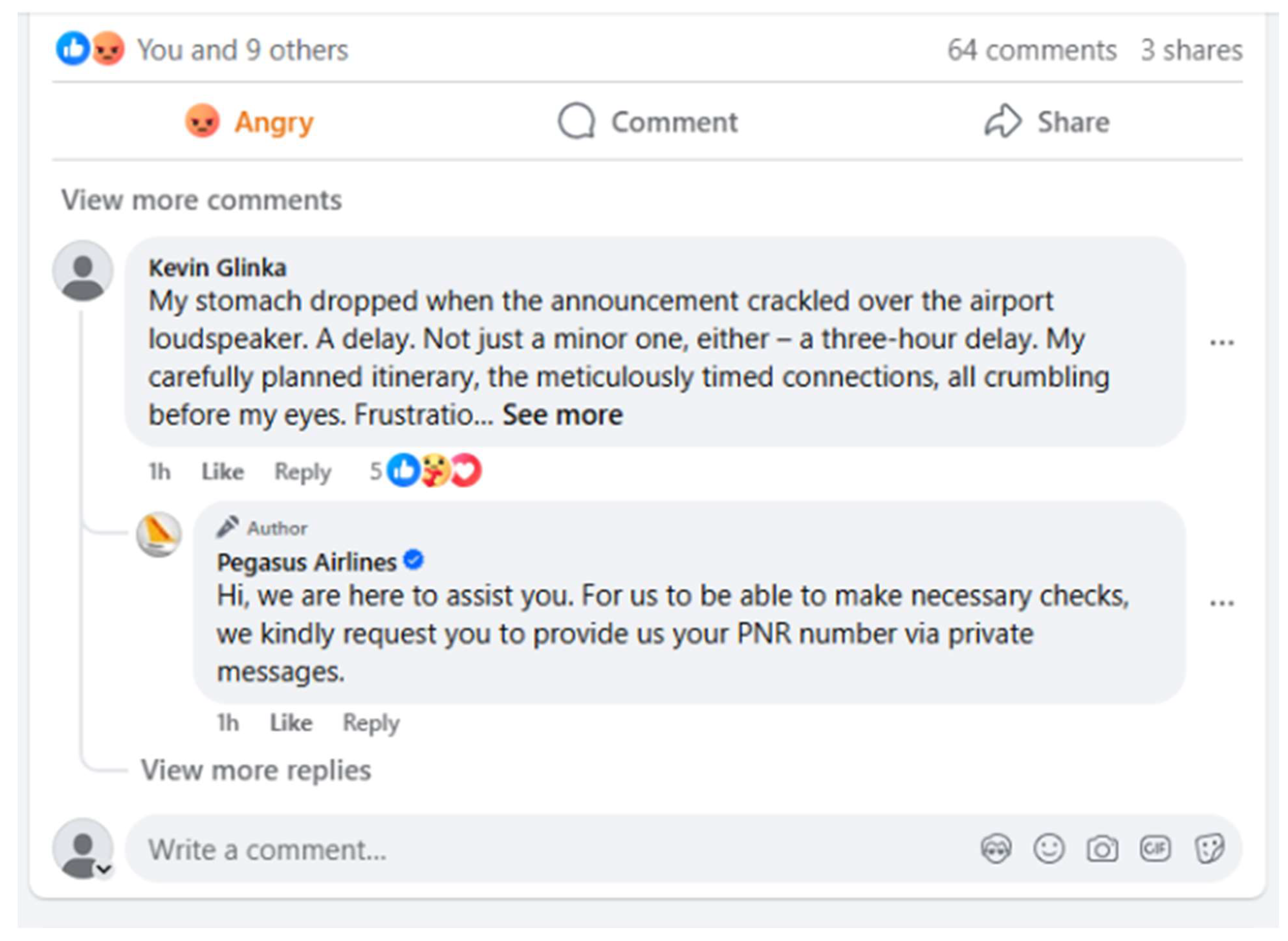

Figure 8.

A customer files a complaint via Complaint Copilot on the airline Facebook page.

Figure 8.

A customer files a complaint via Complaint Copilot on the airline Facebook page.

Figure 9.