Submitted:

17 February 2025

Posted:

18 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

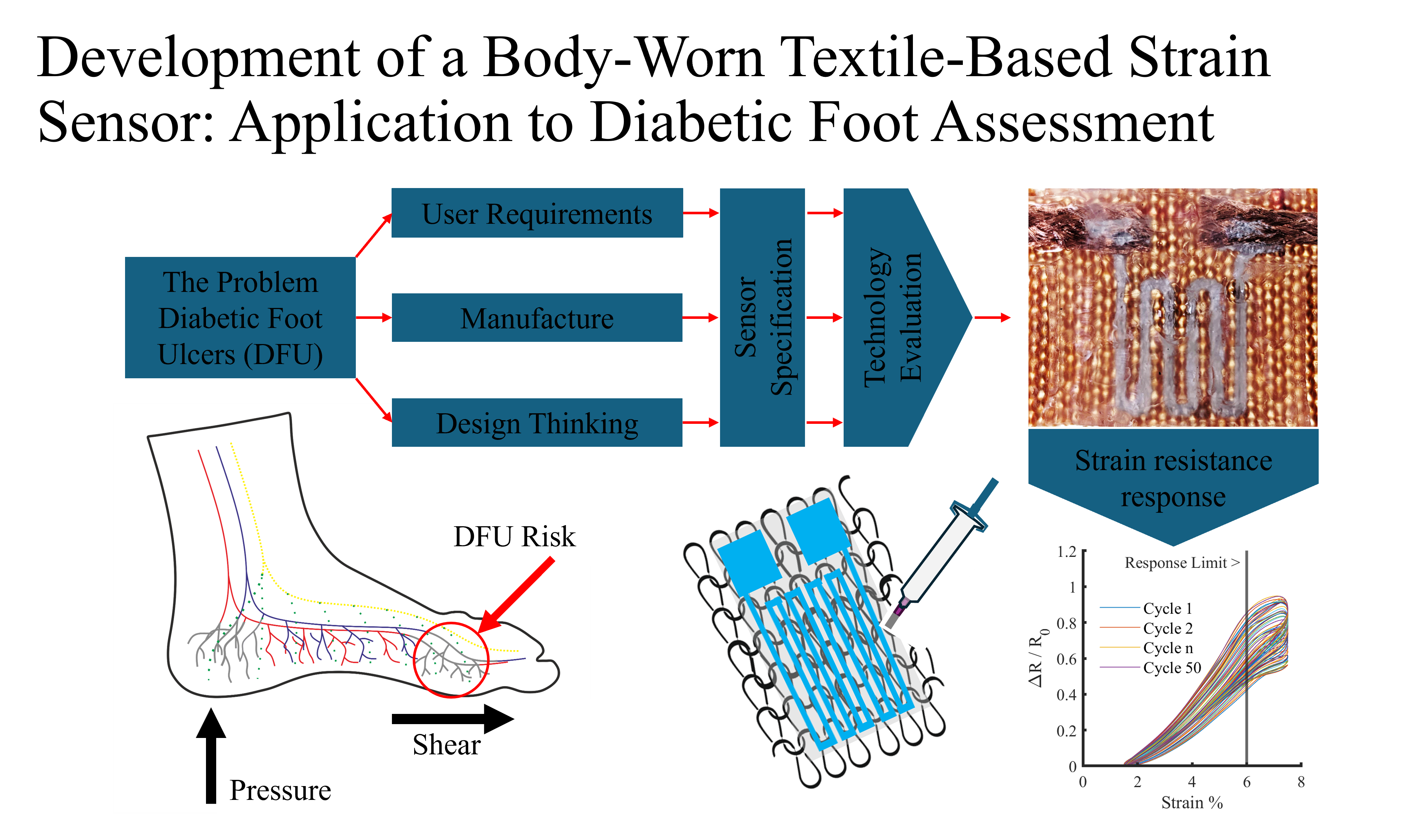

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Scope

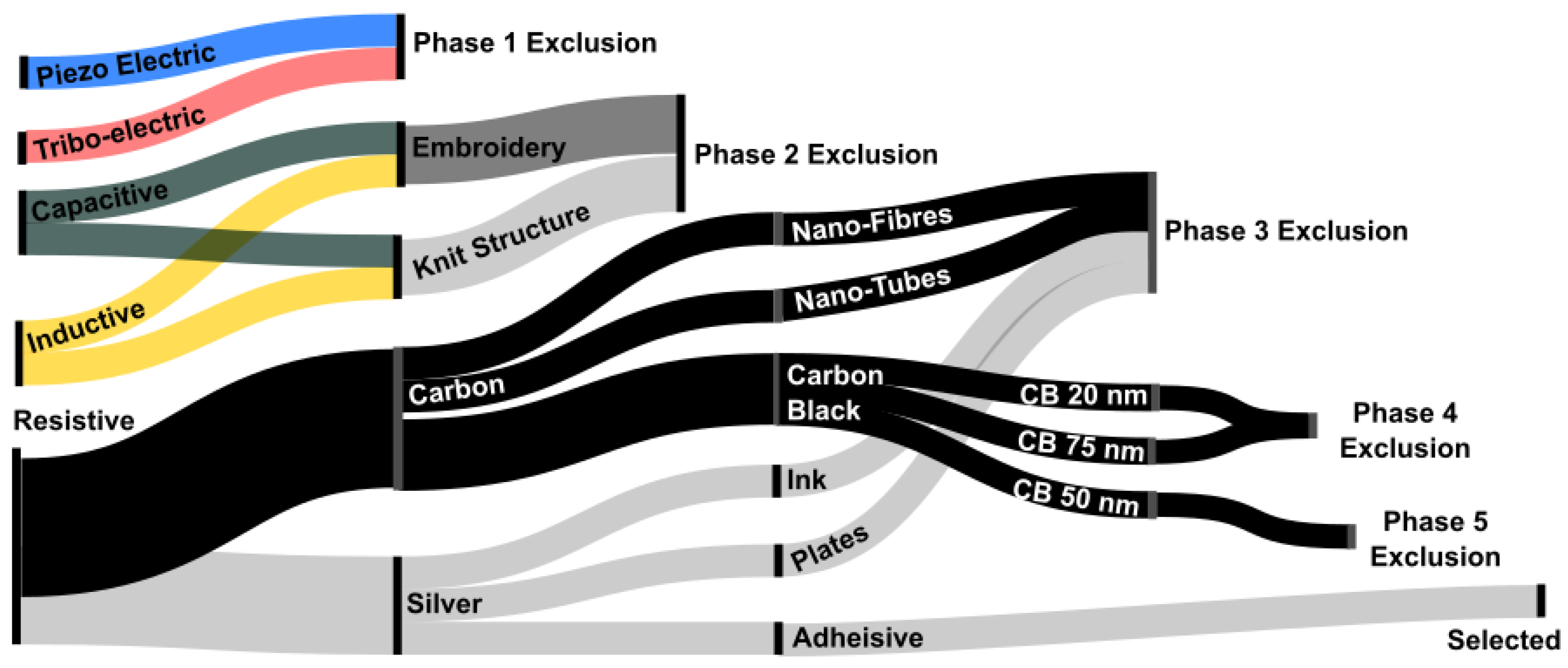

2.2. Technology Evaluation

2.2.1. Self-Generating

2.2.2. Capacitance

2.2.3. Resistive: Yarns

2.2.4. Resistive: Carbon Particles

2.2.5. Resistive: Silver Particles

2.2.6. Evaluation Summary

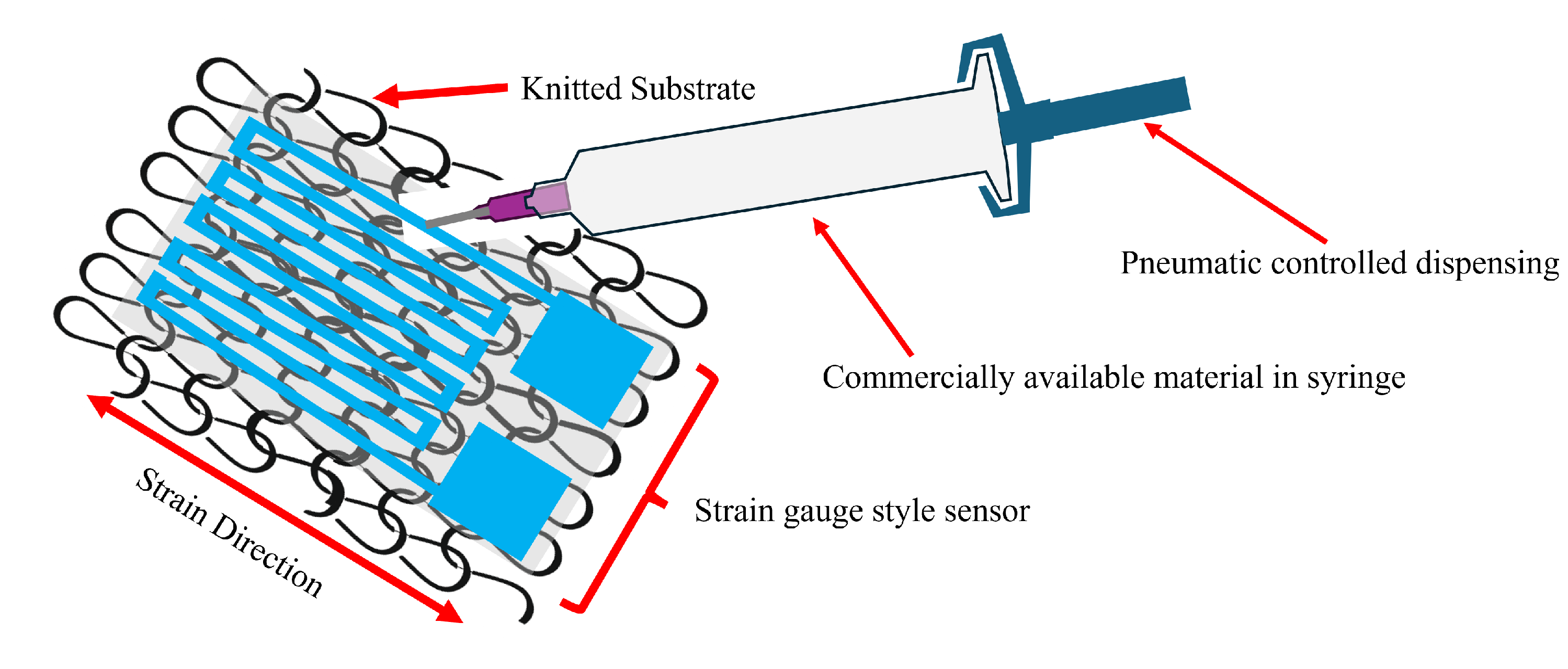

3. Sensor Development

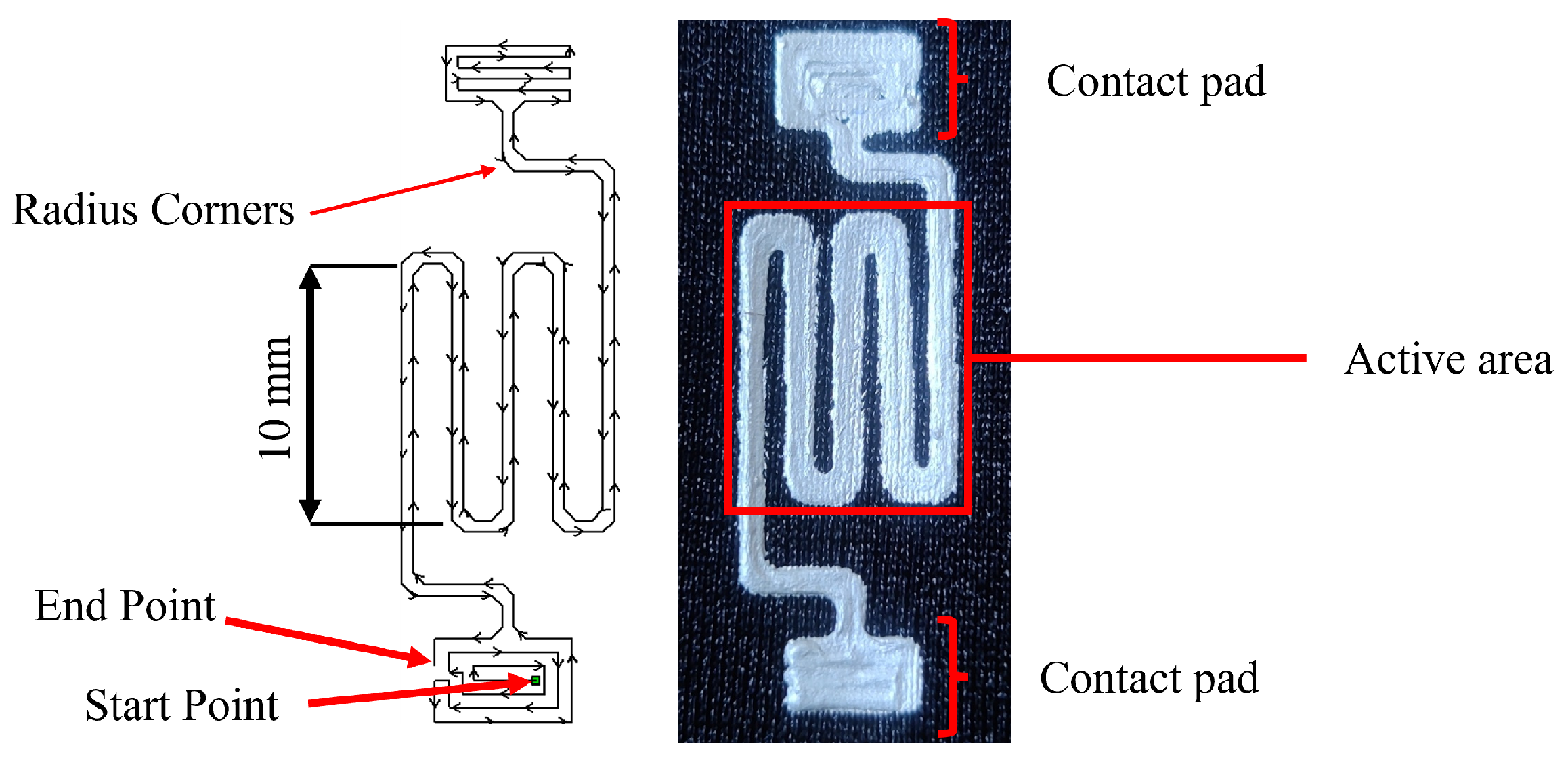

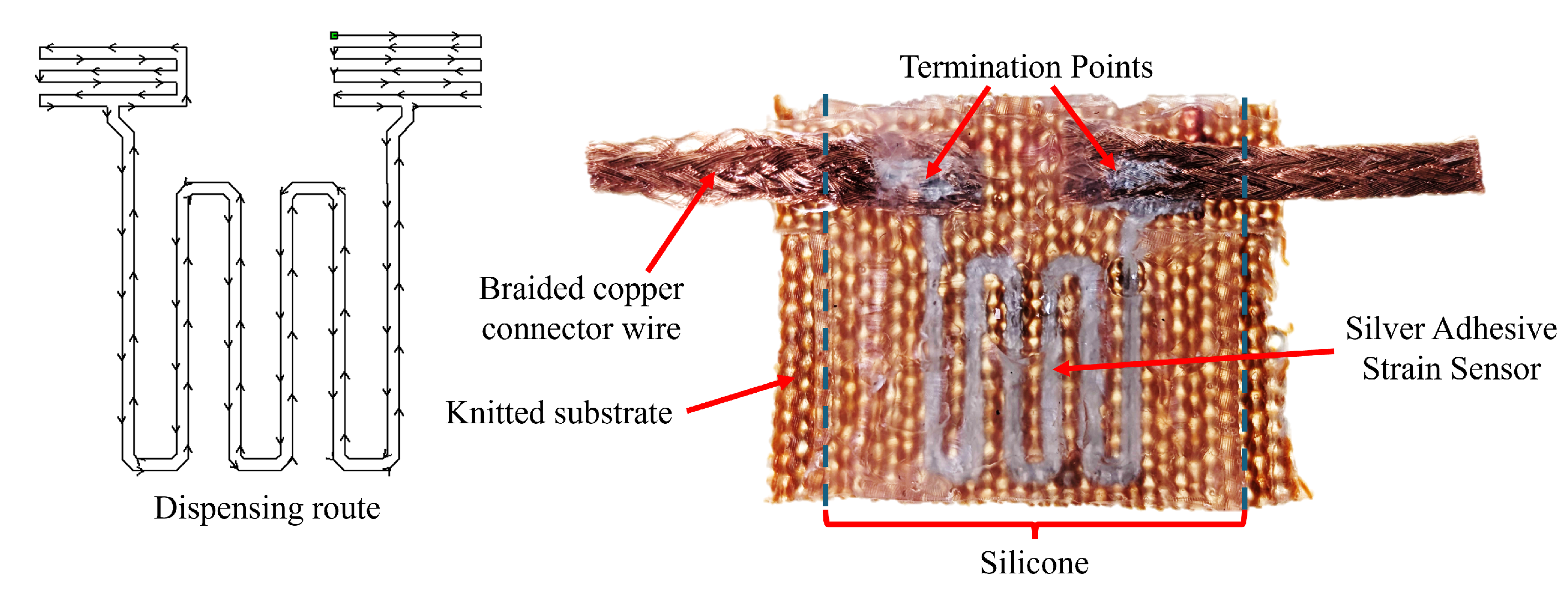

3.1. Design and Manufacture

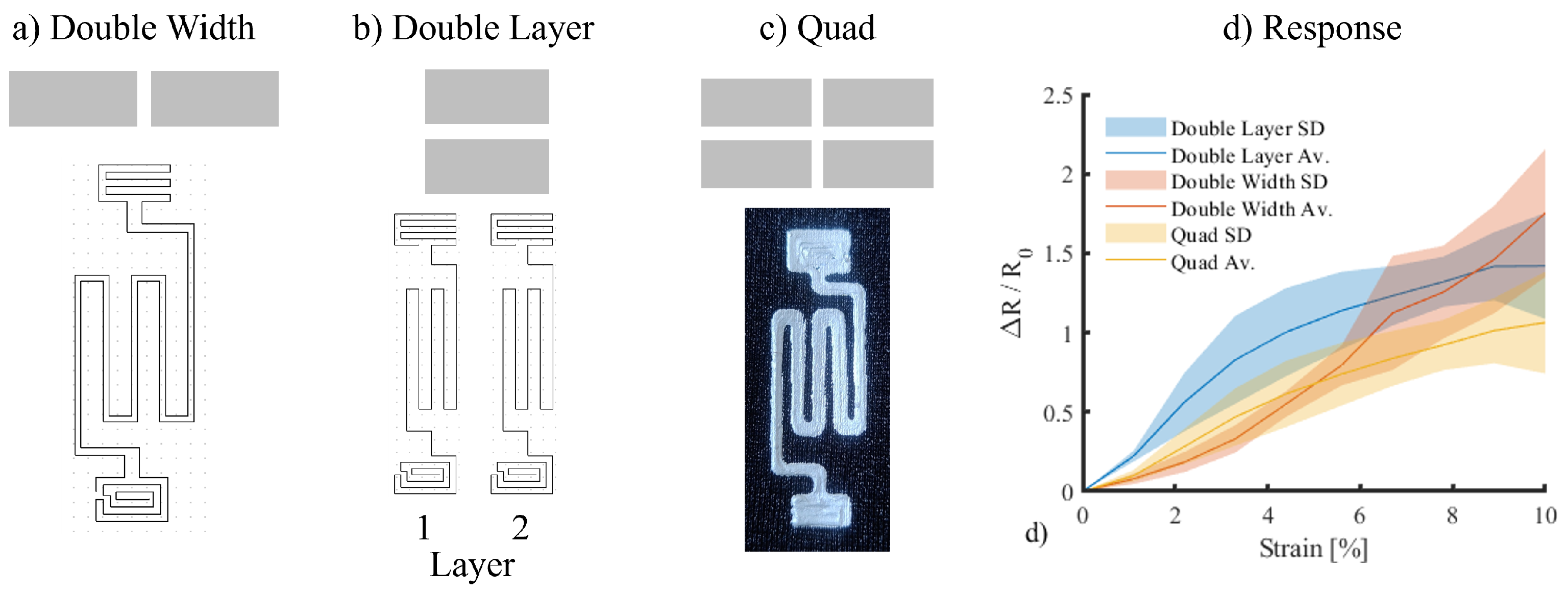

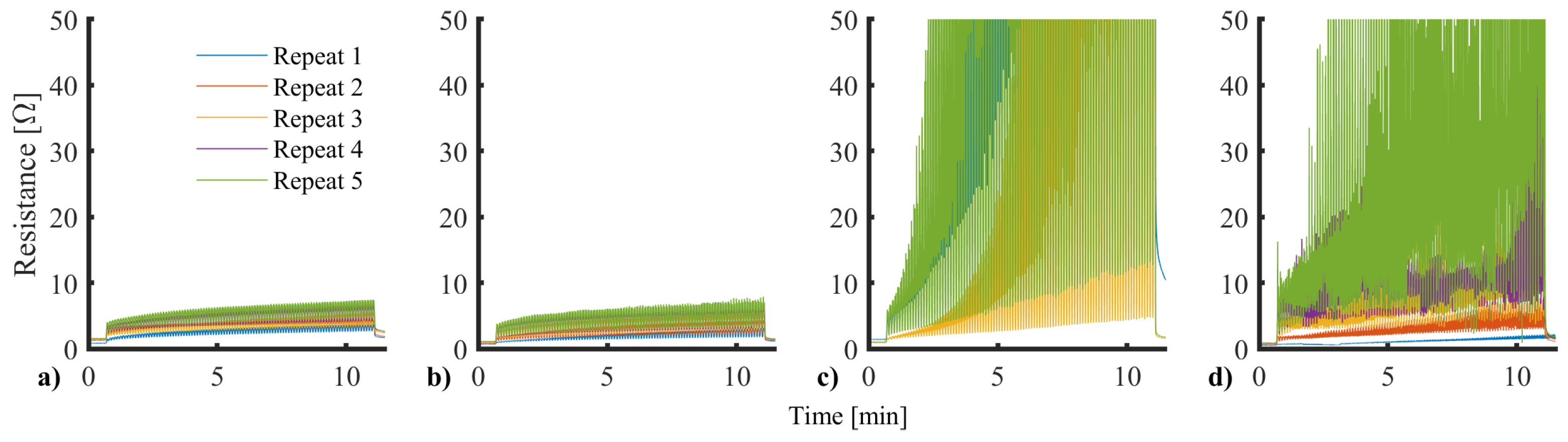

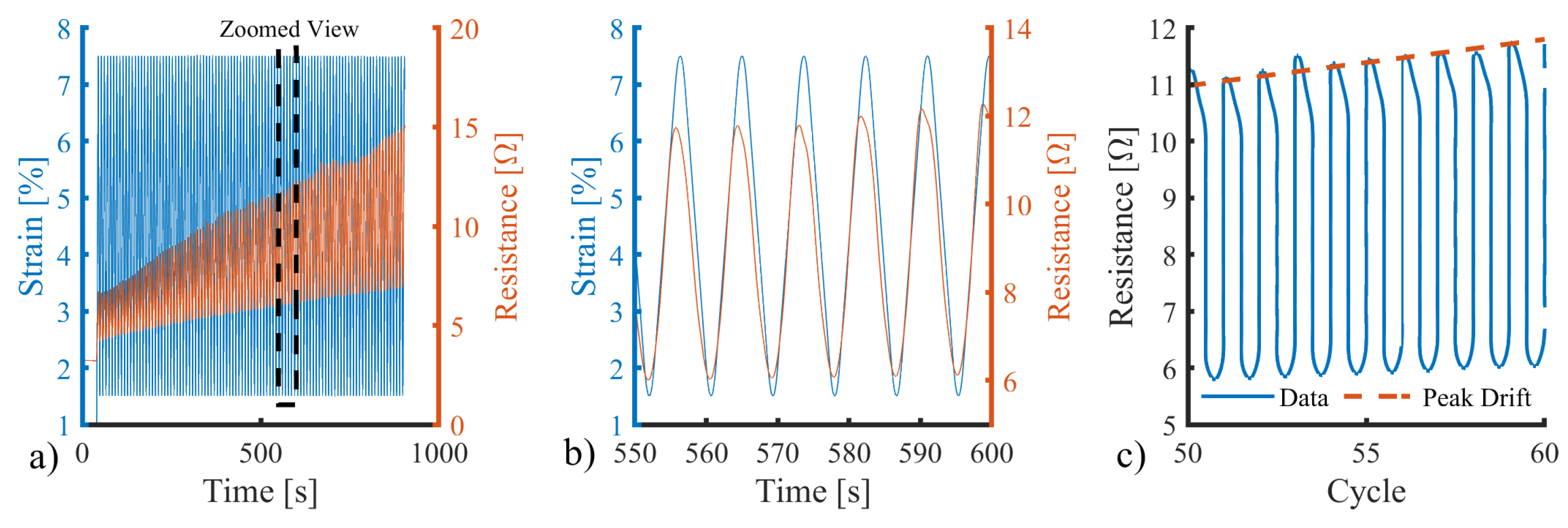

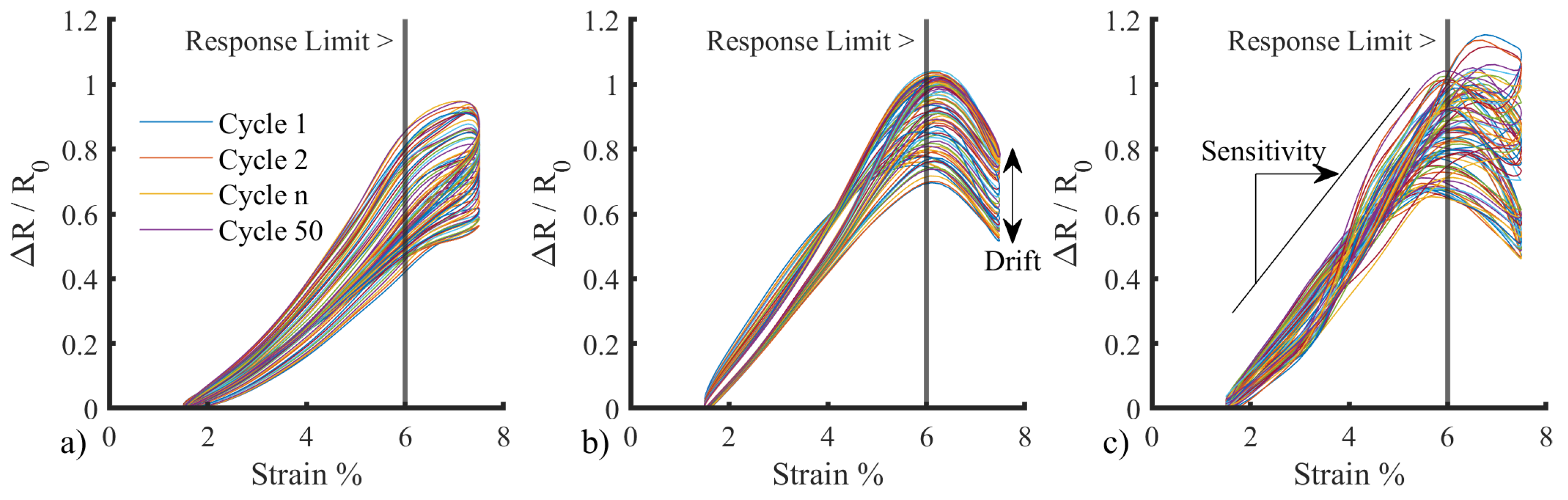

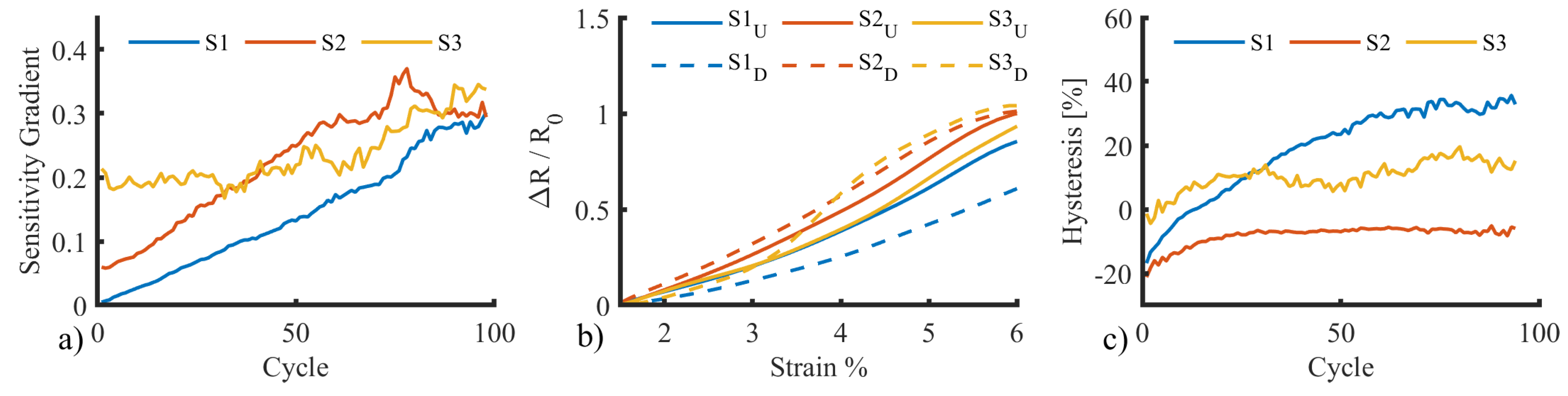

3.2. Design Parametric Testing

3.3. Robustness Improvements

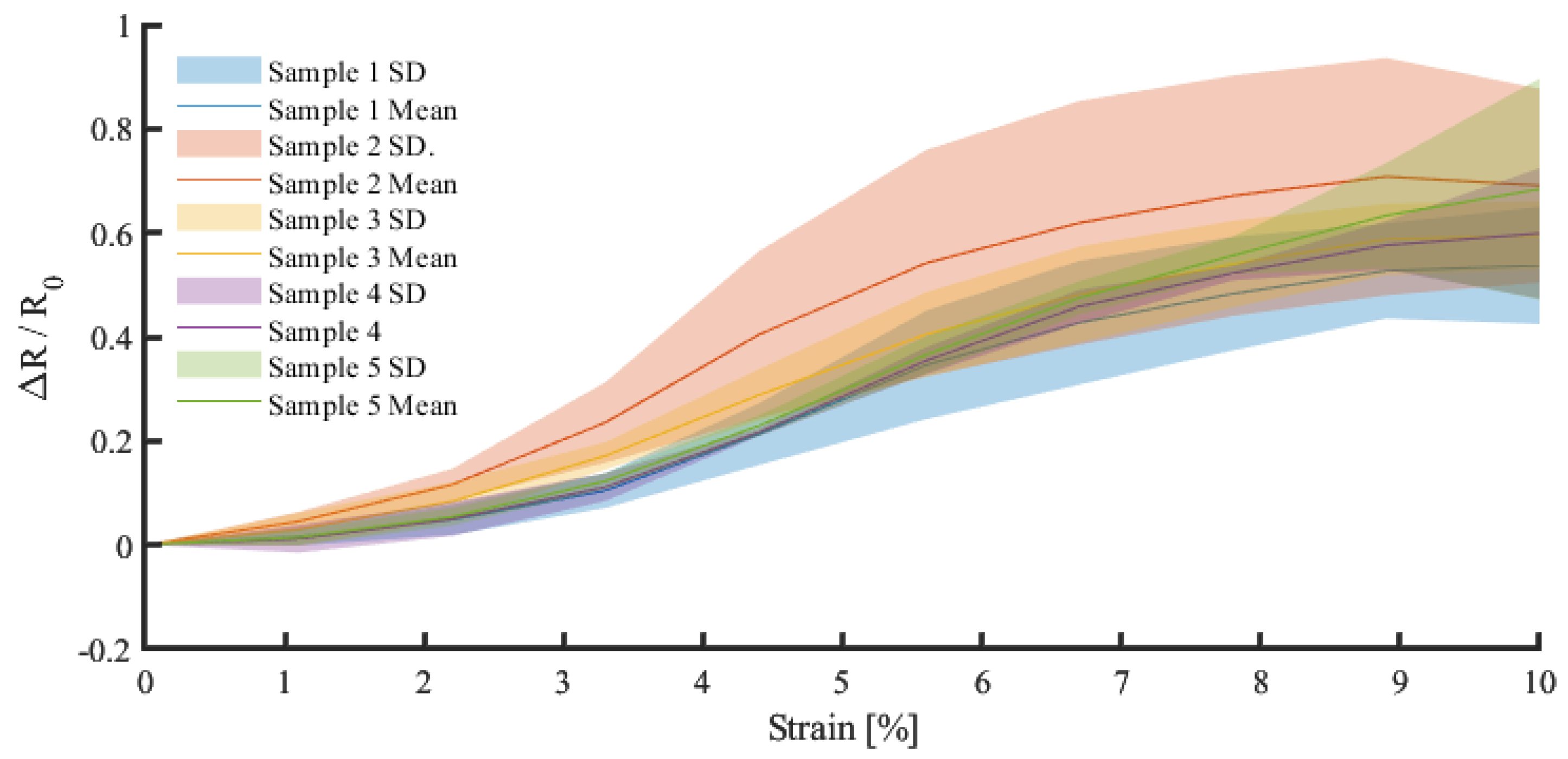

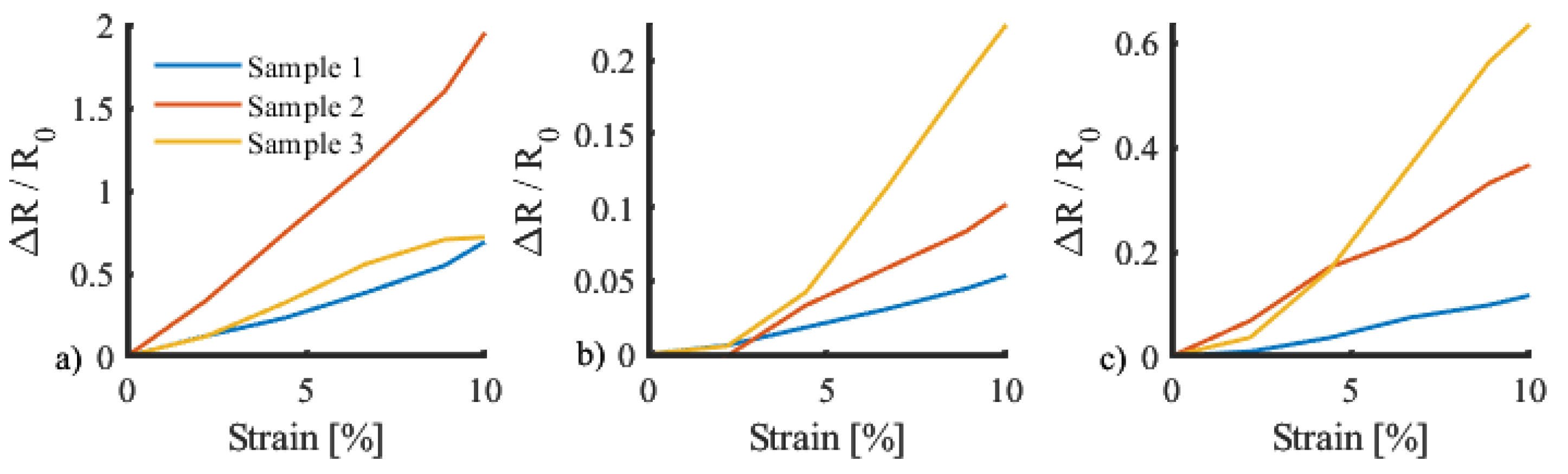

3.4. Lycra Performance Evaluation

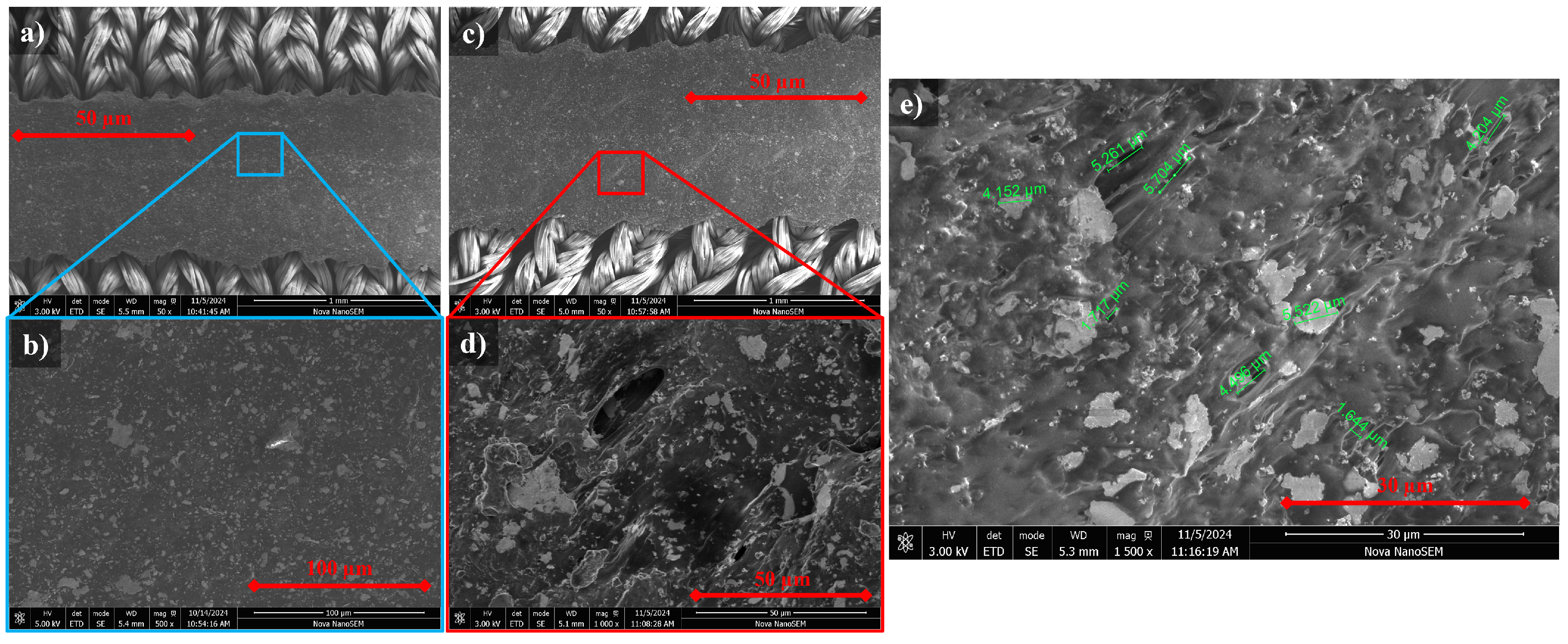

3.5. Mechanism of Action

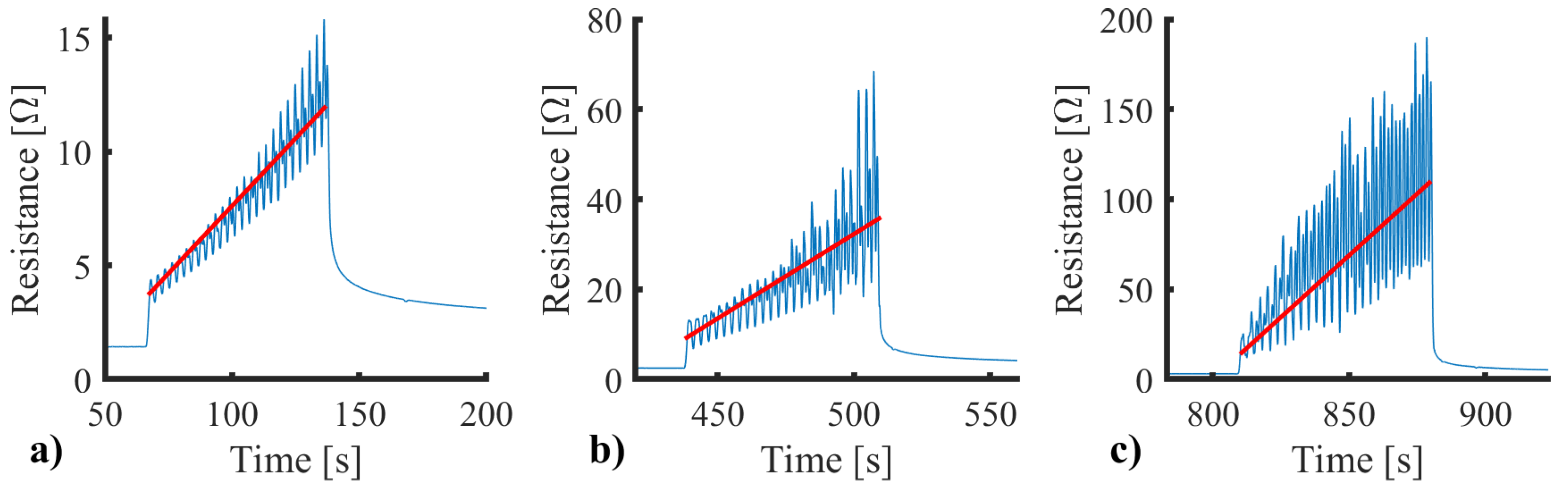

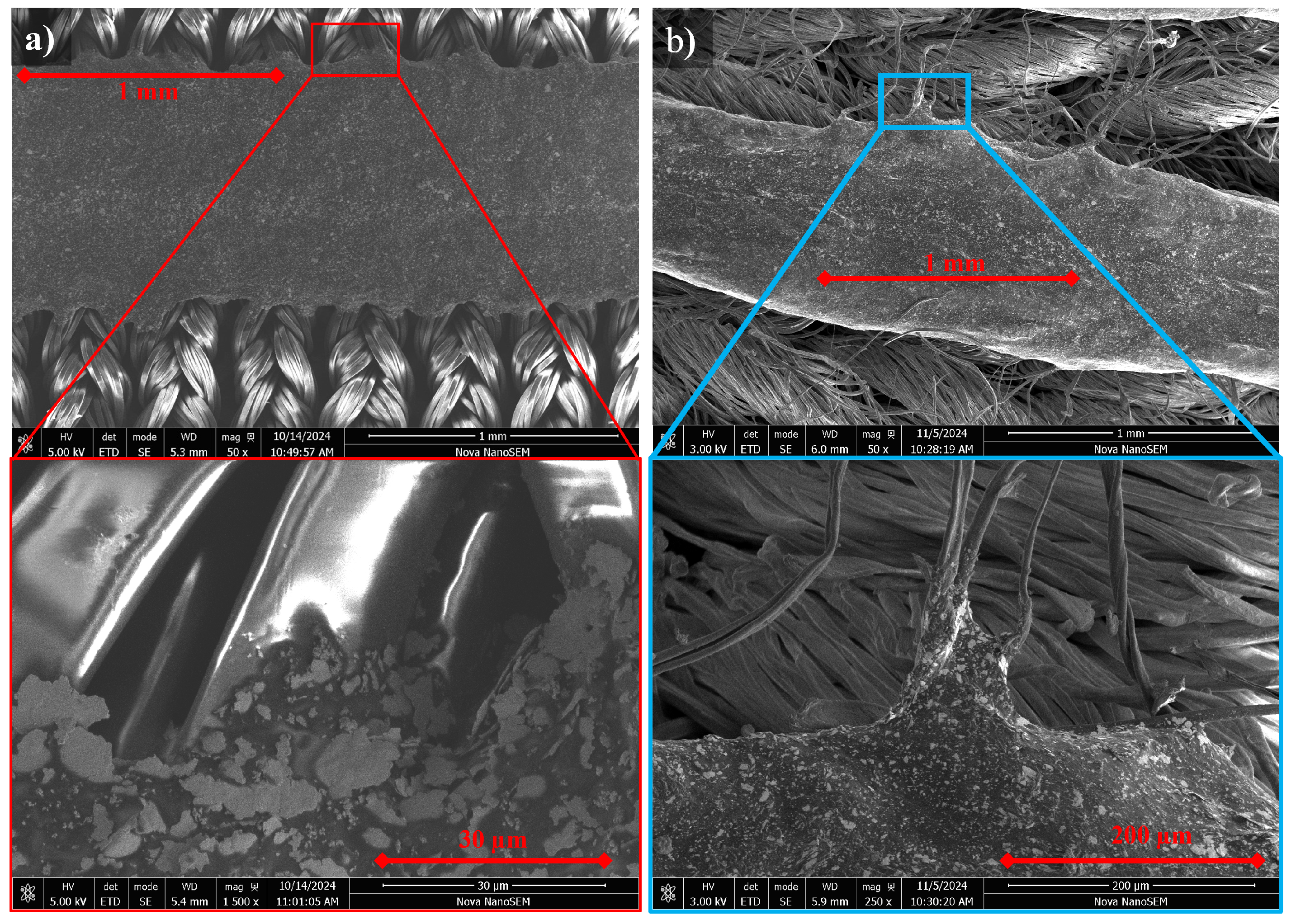

3.6. Reinforcement of Sensing Element

3.6.1. Knitted Substrate Implementation

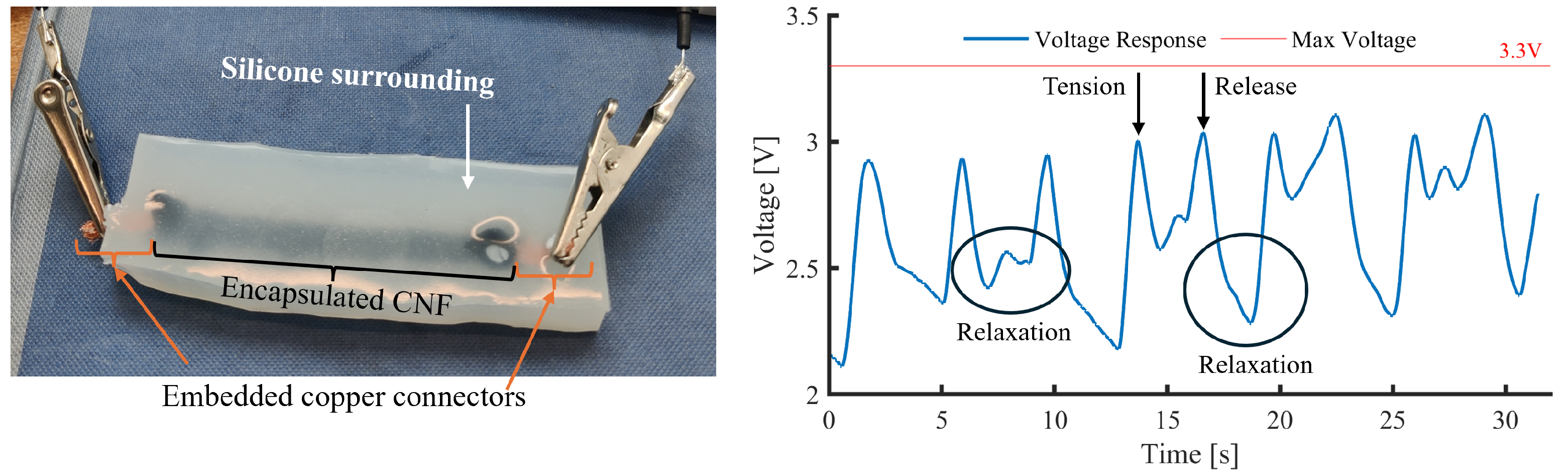

3.6.2. Sensor Encapsulation in Silicone

4. Final Sensor Design and Evaluation

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CB | Carbon Black |

| CNF | Carbon Nano-Fibres |

| CNT | Carbon Nano-Tubes |

| DFU | Diabetic Foot Ulcer |

| DL | Double Layer |

| DW | Double Width |

| TRL | Technology Readiness Level |

References

- Armstrong, D.G.; Tan, T.W.; Boulton, A.J.M.; Bus, S.A. Diabetic Foot Ulcers: A Review. JAMA 2023, 330, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NDFC. National Diabetes Foot Care Audit 2018 to 2023. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/national-diabetes-footcare-audit/2018-2023, 2023.

- Tresierra-Ayala, M.A.; García Rojas, A. Association between Peripheral Arterial Disease and Diabetic Foot Ulcers in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus Type 2. Medicina Universitaria 2017, 19, 123–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubský, M.; Jirkovská, A.; Bem, R.; Fejfarová, V.; Skibová, J.; Schaper, N.C.; Lipsky, B.A. Risk Factors for Recurrence of Diabetic Foot Ulcers: Prospective Follow-up Analysis in the Eurodiale Subgroup. International Wound Journal 2013, 10, 555–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dirac, P. The Principles of Quantum Mechanics; Comparative Pathobiology - Studies in the Postmodern Theory of Education, Clarendon Press, 1981.

- Baclawski, K. The Observer Effect. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Conference on Cognitive and Computational Aspects of Situation Management (CogSIMA); 2018; pp. 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyzelman, A.M.; Koelewyn, K.; Murphy, M.; Shen, X.; Yu, E.; Pillai, R.; Fu, J.; Scholten, H.J.; Ma, R. Continuous Temperature-Monitoring Socks for Home Use in Patients With Diabetes: Observational Study. J Med Internet Res 2018, 20, e12460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao Huang.; Cheng Wang.; Hao Yu.; Hongzhi Wang.; Qinghong Zhang.; Meifang Zhu. Human Walking-Driven Wearable All-Fiber Triboelectric Nanogenerator Containing Electrospun Polyvinylidene Fluoride Piezoelectric Nanofibers | Elsevier Enhanced Reader, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Xu, C.; Pan, S.; Xia, S.; Wei, P.; Noh, H.Y.; Zhang, P.; Jiang, X. Conductive Thread-Based Textile Sensor for Continuous Perspiration Level Monitoring. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland) 2018, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, K.; Narayana, H.; Servati, A.; Bahi, A.; Soltanian, S.; Servati, P.; Ko, F.K. Electronic Textiles for Electrocardiogram Monitoring: A Review on the Structure–Property and Performance Evaluation from Fiber to Fabric. Textile Research Journal 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, S.; McCullough, M.B.A.; Akangah, P.M. The Structural Effects of Diabetes on Soft Tissues: A Systematic Review. CRB 2021, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Xu, B.; Chen, W. Influence of Hallux Valgus Deformity on Forefoot Pressure Distribution of Chinese Diabetic Patients. Int J Diabetes Dev Ctries 2015, 35, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veves, A.; Murray, H.J.; Young, M.J.; Boulton, A.J.M. The Risk of Foot Ulceration in Diabetic Patients with High Foot Pressure: A Prospective Study. Diabetologia 1992, 35, 660–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatwin, K.E.; Abbott, C.A.; Boulton, A.J.; Bowling, F.L.; Reeves, N.D. The Role of Foot Pressure Measurement in the Prediction and Prevention of Diabetic Foot Ulceration—A Comprehensive Review. Diabetes/Metabolism Research and Reviews 2019, 36, e3258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luger, E.; Nissan, M.; Karpf, A.; Steinberg, E.; Dekel, S. Dynamic Pressures on the Diabetic Foot. Foot Ankle Int. 2001, 22, 715–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, J.E.; Hall, J.O.; Davis, B.L. Simultaneous Measurement of Plantar Pressure and Shear Forces in Diabetic Individuals. Gait & Posture 2002, 15, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.D.; De Siqueira, J.; Nixon, J.E.; Siddle, H.J.; Culmer, P.R.; Russell, D.A. Plantar Shear Stress in the Diabetic Foot: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Diabet Med 2022, 39, e14661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hicks, C.W.; Selvin, E. Epidemiology of Peripheral Neuropathy and Lower Extremity Disease in Diabetes. Current diabetes reports 2019, 19, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitei, D.L.; Ison, K.; Edmonds, M.E.; Lord, M. Time-Dependent Behaviour of a Force-Sensitive Resistor Plantar Pressure Measurement Insole. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part H: Journal of Engineering in Medicine 1996, 210, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, H.; Guan, J.; Weatherly, M. Accuracy and Precision of Two In-Shoe Pressure Measurement Systems. Ergonomics 2002, 45, 537–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Ma, H.; Qin, L.Y.; Guan, X.; Chan, K.M.; Law, S.W.; Qin, L.; Liao, W.H. Design of a Lower Extremity Exoskeleton for Motion Assistance in Paralyzed Individuals. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Biomimetics, IEEE-ROBIO 2015, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Anas, M.N. An Instrumented Insole System for Gait Monitoring and Analysis. International Journal of Online and Biomedical Engineering (iJOE) 2014, 10, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabiri, F.; Vahdatpour, A.; Noshadi, H.; Hagopian, H.; Sarrafzadeh, M. Electronic Orthotics Shoe: Preventing Ulceration in Diabetic Patients. In Proceedings of the 2008 30th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society; 2008; pp. 771–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKnight, M.; Tabor, J.; Agcayazi, T.; Fleming, A.; Ghosh, T.K.; Huang, H.; Bozkurt, A. Fully Textile Insole Seam-Line for Multimodal Sensor Mapping. IEEE Sensors Journal 2020, 20, 10145–10153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Ivanov, K.; Mei, Z.; Li, H.; Li, H.; Lubich, L.; Wang, C.; Wang, L. A Soft Wearable and Fully-Textile Piezoresistive Sensor for Plantar Pressure Capturing. Micromachines 2021, 12, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aqueveque, P.; Osorio, R.; Pastene, F.; Saavedra, F.; Pino, E. Capacitive Sensors Array for Plantar Pressure Measurement Insole Fabricated with Flexible PCB. In Proceedings of the 2018 40th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC); 2018; pp. 4393–4396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guignier, C.; Camillieri, B.; Schmid, M.; Rossi, R.M.; Bueno, M.A. E-Knitted Textile with Polymer Optical Fibers for Friction and Pressure Monitoring in Socks. Sensors 2019, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal-Junior, A.G.; Frizera, A.; Avellar, L.M.; Marques, C.; Pontes, M.J. Polymer Optical Fiber for In-Shoe Monitoring of Ground Reaction Forces During the Gait. IEEE Sensors Journal 2018, 18, 2362–2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollard, J.P.; Le Quesne, L.P. Method of Healing Diabetic Forefoot Ulcers. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1983, 286, 436–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Jones, D.; Chapman, G.J.; Siddle, H.J.; Russell, D.A.; Alazmani, A.; Culmer, P. A Review of Wearable Sensor Systems to Monitor Plantar Loading in the Assessment of Diabetic Foot Ulcers. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 2020, 67, 1989–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro-Martins, P.; Marques, A.; Coelho, L.; Vaz, M.; Baptista, J.S. In-Shoe Plantar Pressure Measurement Technologies for the Diabetic Foot: A Systematic Review. Heliyon 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, L.; Zhu, X.; Zhe, J. An Inductive Sensor for Real-Time Measurement of Plantar Normal and Shear Forces Distribution. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 2015, 62, 1316–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Jones, D.; Chapman, G.J.; Siddle, H.J.; Russell, D.A.; Alazmani, A.; Culmer, P. Design of a Digital Triaxial Force Sensor for Plantar Load Measurements. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE SENSORS; 2019; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, M.; Hosein, R. A Study of In-Shoe Plantar Shear in Patients with Diabetic Neuropathy. Clinical Biomechanics 2000, 15, 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, T.; Hamatani, M.; Noguchi, H.; Oe, M.; Sanada, H. Insole-Type Simultaneous Measurement System of Plantar Pressure and Shear Force During Gait for Diabetic Patients. Journal of Robotics and Mechatronics 2012, 24, 766–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Bader, D.L.; Moser, D.; Parker, D.J.; Forghany, S.; Nester, C.J.; Jiang, L. A Wearable Insole System to Measure Plantar Pressure and Shear for People with Diabetes. Sensors 2023, 23, 3126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amemiya, A.; Noguchi, H.; Oe, M.; Takehara, K.; Ohashi, Y.; Suzuki, R.; Yamauchi, T.; Kadowaki, T.; Sanada, H.; Mori, T. Factors Associated with Callus Formation in the Plantar Region through Gait Measurement in Patients with Diabetic Neuropathy: An Observational Case-Control Study. Sensors 2020, 20, 4863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.D.; Crossland, S.R.; Nixon, J.E.; Siddle, H.J.; Russell, D.A.; Culmer, P.R. STrain Analysis and Mapping of the Plantar Surface (STAMPS) – A Novel Technique of Plantar Load Analysis during Gait, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; De Boer, G.; Kow, J.; Alazmani, A.; Ghajari, M.; Hewson, R.; Culmer, P. Design Methodology for Magnetic Field-Based Soft Tri-Axis Tactile Sensors. Sensors 2016, 16, 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Jones, D.; de Boer, G.; Kow, J.; Beccai, L.; Alazmani, A.; Culmer, P. Design and Characterization of Tri-Axis Soft Inductive Tactile Sensors. IEEE Sensors Journal 2018, 18, 7793–7801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajala, S.n.K.; Lekkala, J. Plantar Shear Stress Measurements — A Review. Clinical Biomechanics 2014, 29, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corser, J.; Yoldi, I.; Reeves, N.D.; Culmer, P.; Venkatraman, P.; Orlando, G.; Turnbull, R.; Boakes, P.; Woodin, E.; Lightup, R.; et al. Beyond Sensors and Alerts: Smart Wearables for Diabetic Foot Ulcer Prevention Need to Be Part of a Wider Behaviour Change Intervention. Journal Medical Internet Research 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Viry, L.; Levi, A.; Totaro, M.; Mondini, A.; Mattoli, V.; Mazzolai, B.; Beccai, L. Flexible Three-Axial Force Sensor for Soft and Highly Sensitive Artificial Touch. Advanced Materials 2014, 26, 2659–2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.K.; Chung, J.; Chang, S.I.; Yoon, E. Real-Time Measurement of the Three-Axis Contact Force Distribution Using a Flexible Capacitive Polymer Tactile Sensor. J. Micromech. Microeng. 2011, 21, 035010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, V.M.; Gomes, B.B.; Neto, M.A.; Amaro, A.M. A Systematic Review of Insole Sensor Technology: Recent Studies and Future Directions. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 6085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahin, L.; Tourlonias, M.; Bueno, M.A.; Sharma, K.; Rossi, R.M. Smart Textiles with Polymer Optical Fibre Implementation for In-Situ Measurements of Compression and Bending. SSRN. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhu, W.; Zhang, L.; Gong, J.; Zhao, D.; Liu, M.; Lin, L.; Meng, Q.; Thompson, R.; Sun, Y. Magnetic Properties of Smart Textile Fabrics through a Coating Method with NdFeB Flake-like Microparticles. Journal of Engineered Fibers and Fabrics 2019, 14, 0–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, E. Design Potentials of Magnetic Yarns. IRE Transactions on Broadcast and Television Receivers 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.K.; Lin, L.; Yi, F.; Li, X.; Pradel, K.C.; Zi, Y.; Wu, C.I.; He, J.H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.L. A Flexible, Stretchable and Shape-Adaptive Approach for Versatile Energy Conversion and Self-Powered Biomedical Monitoring. Advanced Materials 2015, 27, 3817–3824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Tao, J.; Liu, Y.; Mo, Y.; Bao, R.; Pan, C. Fully Fibrous Large-Area Tailorable Triboelectric Nanogenerator Based on Solution Blow Spinning Technology for Energy Harvesting and Self-Powered Sensing. Small 2022, 18, 2202477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; He, Q.; Meng, K.; Tan, X.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, G.; Yang, J.; Wang, Z.L. Machine-Knitted Washable Sensor Array Textile for Precise Epidermal Physiological Signal Monitoring. Science Advances 2020, 6, eaay2840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mokhtari, F.; Cheng, Z.; Raad, R.; Xi, J.; Foroughi, J. Piezofibers to Smart Textiles: A Review on Recent Advances and Future Outlook for Wearable Technology. Journal of Materials Chemistry 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Diao, D.; Sun, K.; Fan, X.; Wang, P. Study on Friction-Electrification Coupling in Sliding-Mode Triboelectric Nanogenerator. Nano Energy 2018, 48, 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudec, R.; Matúška, S.; Kamencay, P.; Benco, M. A Smart IoT System for Detecting the Position of a Lying Person Using a Novel Textile Pressure Sensor. Sensors 2021, 21, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleskova, H.; Ishaku, A.; Bednar, T.; Hudec, R. Optimization of All-Textile Capacitive Sensor Array for Smart Chair. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 48615–48621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fobelets, K.; Thielemans, K.; Mathivanan, A.; Papavassiliou, C. Characterization of Knitted Coils for E-Textiles. IEEE Sensors J. 2019, 19, 7835–7840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajitsu, Y. Development of E-Textile Sewn Together with Embroidered Fabric Having Motion-Sensing Function Using Piezoelectric Braided Cord for Embroidery. IEEE Transactions on Dielectrics and Electrical Insulation 2020, 27, 1644–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajitsu, Y.; Takarada, J.; Hikichi, T.; Sugii, R.; Takatani, K.; Yanagimoto, H.; Nakanishi, R.; Shiomi, S.; Kitamoto, D.; Nakiri, T.; et al. Application of Piezoelectric PLLA Braided Cord as Wearable Sensor to Realize Monitoring System for Indoor Dogs with Less Physical or Mental Stress. Micromachines 2023, 14, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uno, M.O.; Morita, S.; Omori, M.; Yoshimura, K. Pressure Sensor Yarns with a Sheath-Core Structure Using Multi-Fiber Polymer. Sensors and Actuators A: Physical 2022, 337, 113440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Fu, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Dong, Y.; Wang, X.; Lin, L. A Naturally Integrated Smart Textile for Wearable Electronics Applications. Advanced materials and technologies 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souri, H.; Bhattacharyya, D. Wearable Strain Sensors Based on Electrically Conductive Natural Fiber Yarns. Materials & Design 2018, 154, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, Y.; Yu, H.; Wang, M.; Yang, X.; Zhang, H. Ultrasensitive Wearable Pressure Sensors Based on Silver Nanowire-Coated Fabrics. Nanoscale Res Lett 2020, 15, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seyedin, S.; Razal, J.M.; Innis, P.C.; Jeiranikhameneh, A.; Beirne, S.; Wallace, G.G. Knitted Strain Sensor Textiles of Highly Conductive All-Polymeric Fibers. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 21150–21158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santoni SPA. Sangiacomo Star-D: Sangiacomo Electronic Knitting Machine, 2025.

- Zhu, Y.; Assadian, M.; Ramezani, M.; Aw, K.C. Printing of Soft Stretch Sensor from Carbon Black Composites. In Proceedings of the EUROSENSORS 2018. MDPI; 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honnet, C.; Perner-Wilson, H.; Teyssier, M.; Fruchard, B.; Steimle, J.; Baptista, A.C.; Strohmeier, P. PolySense: Augmenting Textiles with Electrical Functionality Using In-Situ Polymerization. Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems - Proceedings, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souri, H.; Bhattacharyya, D. Highly Stretchable and Wearable Strain Sensors Using Conductive Wool Yarns with Controllable Sensitivity. Sensors and Actuators A: Physical 2019, 285, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anike, J.C.; Le, H.H.; Brodeur, G.E.; Kadavan, M.M.; Abot, J.L. Piezoresistive Response of Integrated CNT Yarns under Compression and Tension: The Effect of Lateral Constraint. C 2017, 3, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiranata, A.; Ohsugi, Y.; Minaminosono, A.; Mao, Z.; Kurata, H.; Hosoya, N.; Maeda, S. A DIY Fabrication Approach of Stretchable Sensors Using Carbon Nano Tube Powder for Wearable Device. Front. Robot. AI 2021, 8, 773056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, T.; Gu, Y.; Liu, T.; Pecht, M. Resistive and Capacitive Strain Sensors Based on Customized Compliant Electrode: Comparison and Their Wearable Applications. Sensors and Actuators A: Physical 2021, 326, 112720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Wang, S.; Lin, A.; Min, H.K.; Zhou, Z.; Dou, W.; Sun, Y.; Huang, X.; Tran, H.; Liu, X. Conductive and Elastic Bottlebrush Elastomers for Ultrasoft Electronics. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muth, J.T.; Vogt, D.M.; Truby, R.L.; Mengüç, Y.; Kolesky, D.B.; Wood, R.J.; Lewis, J.A. Embedded 3D Printing of Strain Sensors within Highly Stretchable Elastomers. Advanced Materials 2014, 26, 6307–6312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shintake, J.; Piskarev, Y.; Jeong, S.H.; Floreano, D. Ultrastretchable Strain Sensors Using Carbon Black-Filled Elastomer Composites and Comparison of Capacitive Versus Resistive Sensors. Advanced Materials Technologies 2018, 3, 1700284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cholleti, E.R.; Stringer, J.; Assadian, M.; Battmann, V.; Bowen, C.; Aw, K. Highly Stretchable Capacitive Sensor with Printed Carbon Black Electrodes on Barium Titanate Elastomer Composite. Sensors 2019, 19, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, P.; Wang, G.; Zhang, Y. Preparation and Performance of Graphene/Carbon Black Silicone Rubber Composites Used for Highly Sensitive and Flexible Strain Sensors. Sensors and Actuators A: Physical 2021, 323, 112659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giffney, T.; Bejanin, E.; Kurian, A.S.; Travas-Sejdic, J.; Aw, K. Highly Stretchable Printed Strain Sensors Using Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotube/Silicone Rubber Composites. Sensors and Actuators A: Physical 2017, 259, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuhisa, N.; Kaltenbrunner, M.; Yokota, T.; Jinno, H.; Kuribara, K.; Sekitani, T.; Someya, T. Printable Elastic Conductors with a High Conductivity for Electronic Textile Applications. Nat Commun 2015, 6, 7461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuhisa, N.; Inoue, D.; Zalar, P.; Jin, H.; Matsuba, Y.; Itoh, A.; Yokota, T.; Hashizume, D.; Someya, T. Printable Elastic Conductors by in Situ Formation of Silver Nanoparticles from Silver Flakes. Nature Mater 2017, 16, 834–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, I.S.; Kim, S.H.; Oh, Y.; Ju, B.K.; Hong, J.M. Ag Flake/Silicone Rubber Composite with High Stability and Stretching Speed Insensitive Resistance via Conductive Bridge Formation. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 5036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Wong, C.P. Thermal Decomposition of Silver Flake Lubricants. Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry 2000, 61, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Lin, W.; Moon, K.s.; Wong, C.P. Fast Preparation of Printable Highly Conductive Polymer Nanocomposites by Thermal Decomposition of Silver Carboxylate and Sintering of Silver Nanoparticles. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2010, 2, 2637–2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clement, J.L.; Jarrett, P.S. Antibacterial Silver. Met Based Drugs 1994, 1, 467–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DM-SAS-10010.

- Shen, H.; Ke, H.; Feng, J.; Jiang, C.; Wei, Q.; Wang, Q. Highly Sensitive and Stretchable C-MWCNTs/PPy Embedded Multidirectional Strain Sensor Based on Double Elastic Fabric for Human Motion Detection. Nanomaterials (Basel, Switzerland) 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Miao, X.; Chen, J.Y.; Jiang, G.; Liu, Q. Sensing Performance of Knitted Strain Sensor on Two-Dimensional and Three-Dimensional Surfaces. Materials & Design 2021, 197, 109273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SID | Name | Requirement |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Robustness | Placed on the foot’s plantar surface up to , bodyweight can be exerted during gait, requiring a robust solution. |

| 2 | Biocompatibility | Solutions must be biocompatible due to the increased risk of infection due to cracked or fissured skin increasing access through natural barriers. |

| 3 | Technology Readiness Level | With the interest of producing a real-world impact on patient quality of life. Solutions using commercially available technology will be prioritised. |

| 4 | Production Scale | The processes used in production must involve scalable technology. |

| 5 | Production Compatible | Relating to ID4 solutions must be compatible with industrial knitting machines. |

| 6 | Sensor Localisation | A discrete rather than global sensing approach for response localisation. |

| 7 | Low Profile | Due to increased sensitivity to ulcer formation of soft tissue, ridges and point forces must be avoided. |

| Parameter | Selected Value |

|---|---|

| Number of Turns | 5 |

| Length | 10 mm |

| Cure Temperature | 75°C |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).