Submitted:

16 February 2025

Posted:

17 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Samples

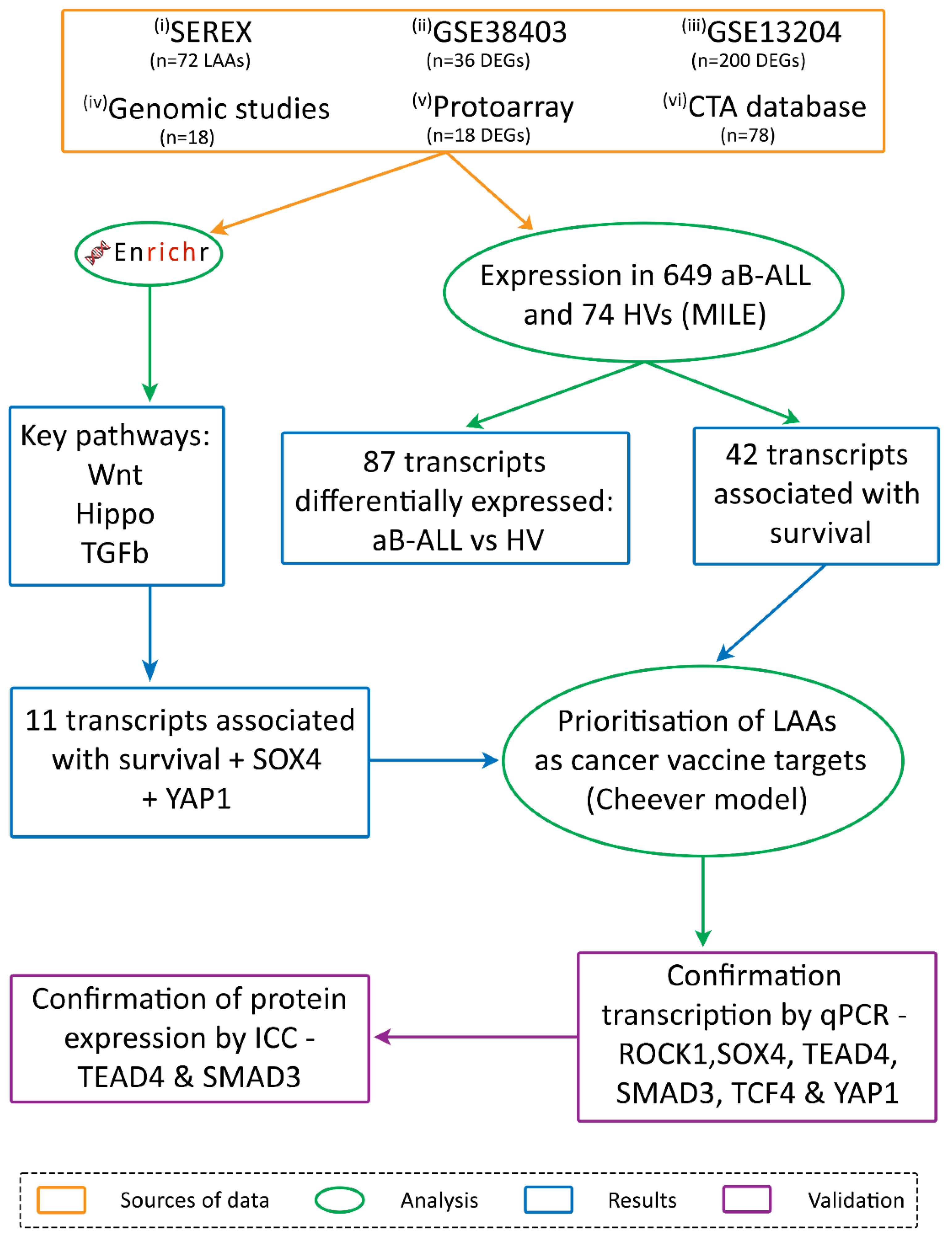

2.2. Antigen Identification

- (i) Serological analysis of recombinant cDNA expression libraries (SEREX)

- (ii) & (iii) Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) identified through the analysis of two microarray databases

- (iv) A review of genomic studies

- (v) Proto-array analysis

- (vi) the CTA database

2.3. Pathway Analysis and Survival

2.4. qPCR

2.5. Immunocytochemistry

3. Results

3.1. Immunoscreening Identified 72 aB-ALL Associated Antigens

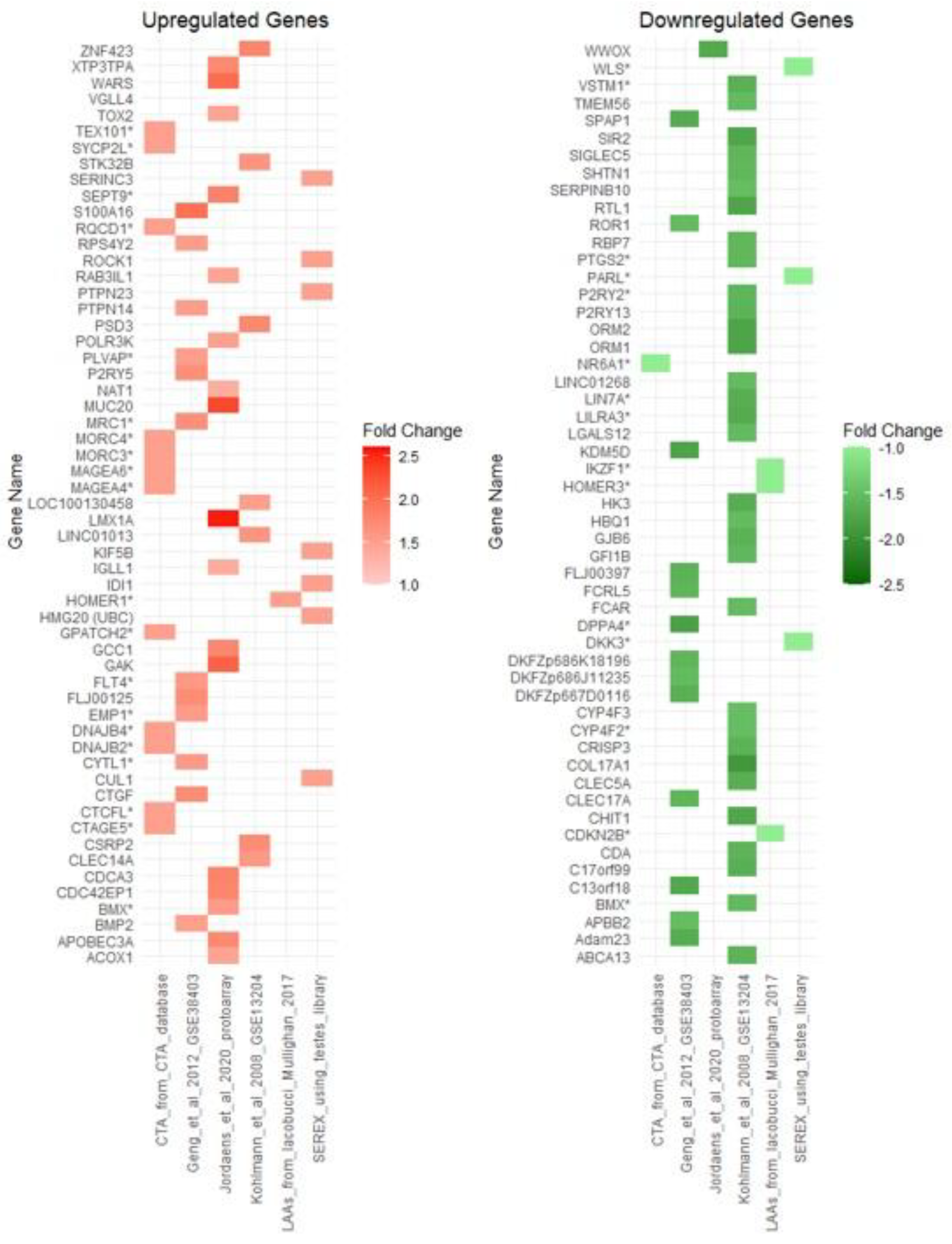

3.2. Association Between Leukaemia Associated Antigen (LAA) Expression in aB-ALL Cells and Patient Survival

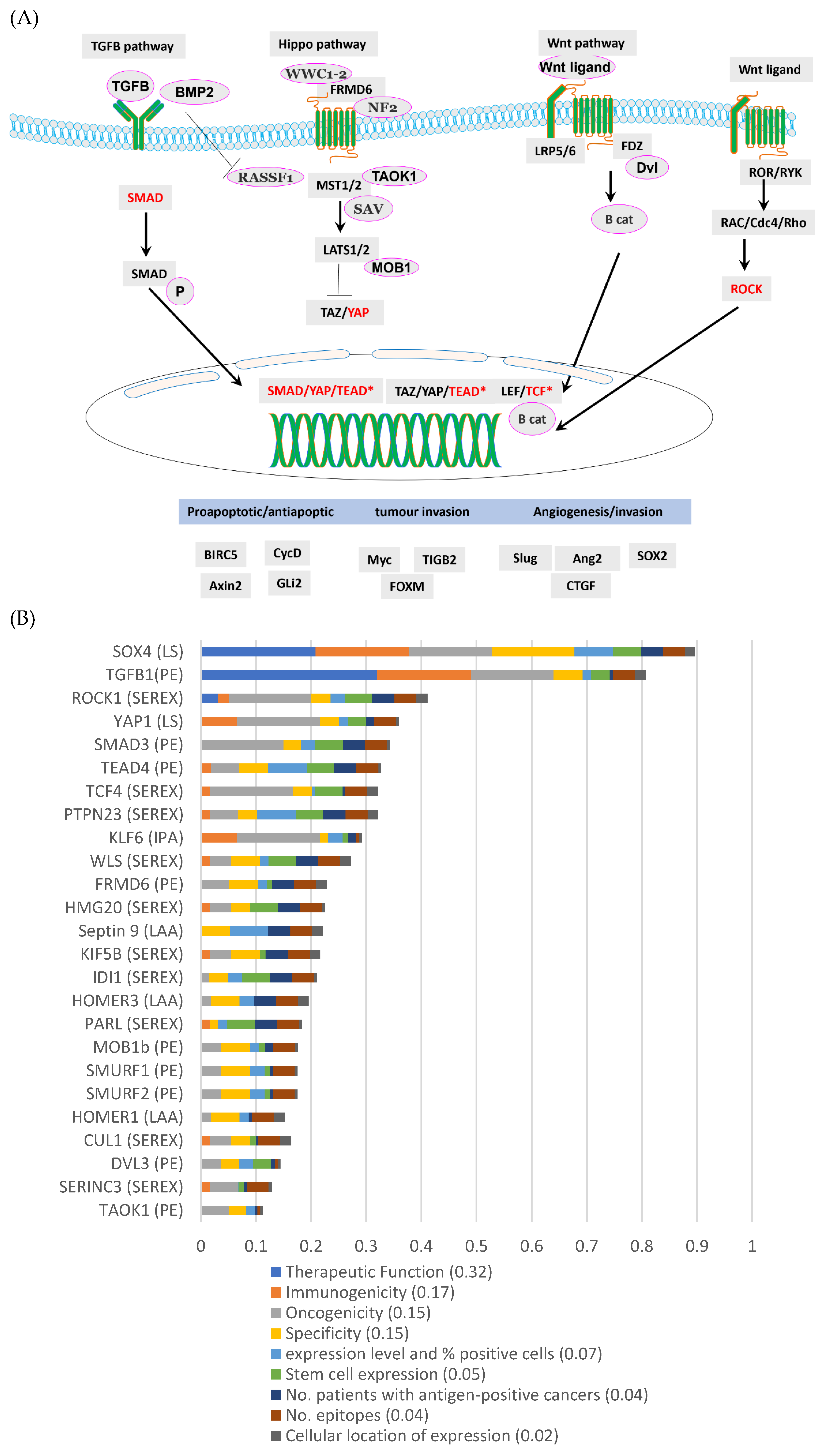

3.3. TGFβ, Wnt and Hippo Pathways Were Highly Represented by the DEGs in aB-ALL Samples

3.4. Most of the aB-ALL Antigens Were Differentially Expressed in Solid Tumours

3.5. SOX4 and TGFβ1 Were the Top-Ranking aB-ALL Vaccine Targets

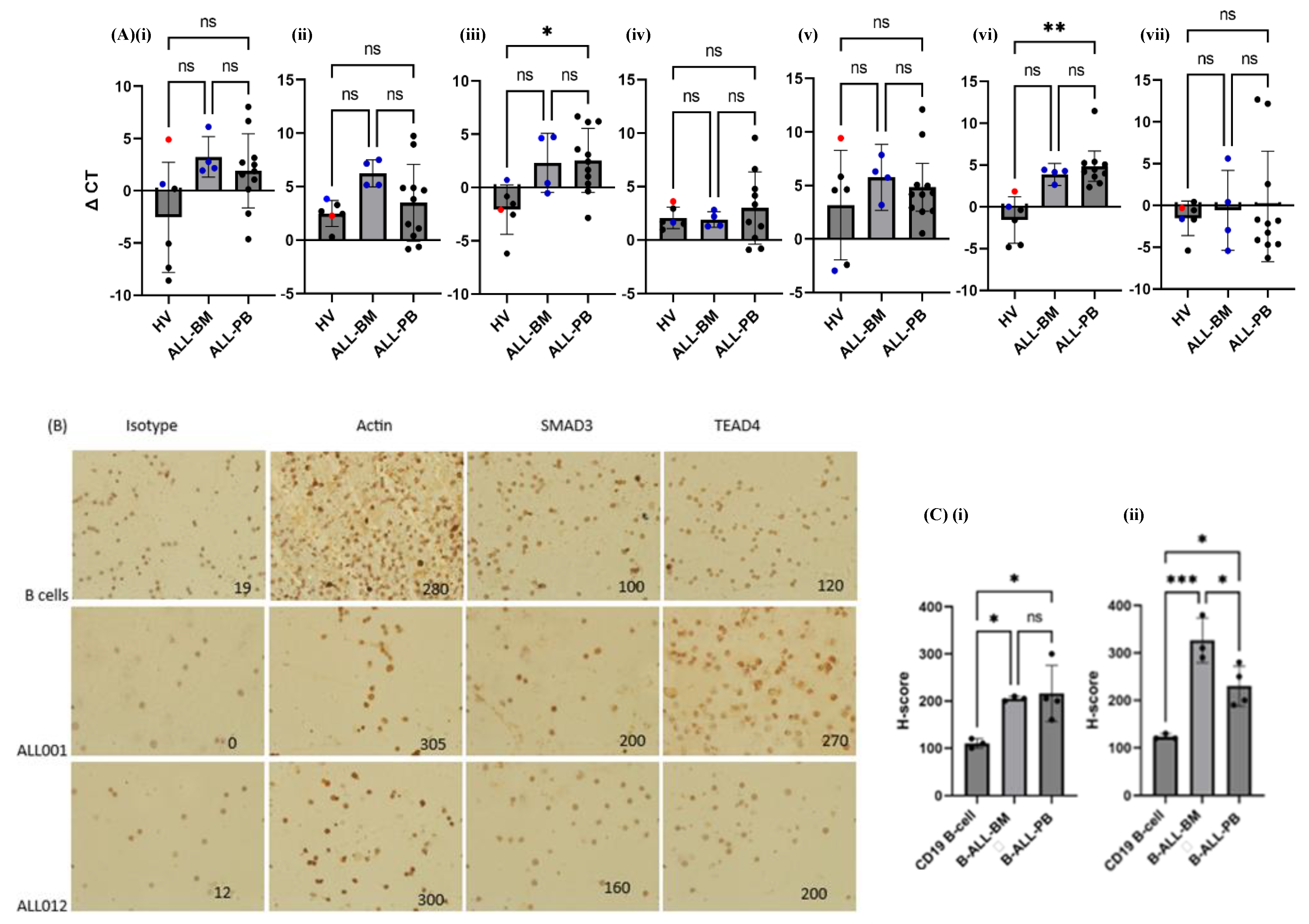

3.6. TCF4, SOX4 and SMAD3 Transcription Was Increased in Almost All aB-ALL Subtypes

3.7. TEAD4 and SMAD3 Protein Expression Was Elevated in aB-ALL Samples

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| aB-ALL | Adult B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia |

| BIRC5 | baculoviral IAP repeat containing 5 |

| BMX | bone marrow tyrosine kinase |

| CAR | chimeric antigen receptor |

| cB-ALL | children with B-ALL |

| CTA | cancer testis antigen |

| DEGs | Differentially expressed genes |

| HV | Healthy volunteer |

| LAA | leukaemia associated antigens |

| NS | Not significant |

| PB | Peripheral blood |

| PRKG1 | protein kinase cGMP-dependent 1 |

| R/R | relapsed/refractory |

| ROCK1 | Rho associated coiled-coil containing protein kinase 1 |

| SMAD3 | SMAD family member 3 |

| SOX4 | SRY-Box Transcription Factor 4 |

| TAAs | Tumour associated antigens |

| TBP1 | TATA-box binding protein |

| TCF4 | T cell Factor 4 |

| TEAD4 | TEA Domain Transcription Factor 4 |

| TGFβ | Transforming Growth Factor-β |

| YAP1 | Yes-associated protein1 |

References

- Samra B, Jabbour E, Ravandi F, Kantarjian H, Short NJ. Evolving therapy of adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia: state-of-the-art treatment and future directions. J Hematol Oncol. 2020;13(1):70. [CrossRef]

- DeAngelo DJ, Jabbour E, Advani A. Recent advances in managing acute lymphoblastic leukemia. American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book. 2020;40:330-42. [CrossRef]

- Gokbuget N, Dombret H, Giebel S, Bruggemann M, Doubek M, Foa R, et al. Minimal residual disease level predicts outcome in adults with Ph-negative B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Hematology. 2019;24(1):337-48. [CrossRef]

- Kantarjian HM, Vandendries E, Advani AS. Inotuzumab Ozogamicin for Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(21):2100-1. [CrossRef]

- Brown PA, Ji L, Xu X, Devidas M, Hogan LE, Borowitz MJ, et al. Effect of Postreinduction Therapy Consolidation With Blinatumomab vs Chemotherapy on Disease-Free Survival in Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults With First Relapse of B-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2021;325(9):833-42. [CrossRef]

- Stackelback AV, Jaschke K, Jousseaume E, Templin C, Jeratsch U, Kosmides D, et al. Tisagenlecleucel vs. historical standard of care in children and young adult patients with relapsed/refractory B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2023;37(12):2346-55. [CrossRef]

- Paul S, Kantarjian H, Jabbour EJ, editors. Adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Mayo Clinic Proceedings; 2016: Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Martino M, Alati C, Canale FA, Musuraca G, Martinelli G, Cerchione C. A Review of Clinical Outcomes of CAR T-Cell Therapies for B-Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021;22(4):2150. [CrossRef]

- Webster J, Luskin MR, Prince GT, DeZern AE, DeAngelo DJ, Levis MJ, et al. Blinatumomab in combination with immune checkpoint inhibitors of PD-1 and CTLA-4 in adult patients with relapsed/refractory (R/R) CD19 positive B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL): preliminary results of a phase I study. Blood. 2018;132:557. [CrossRef]

- Namuduri M, Brentjens RJ. Enhancing CAR T cell efficacy: the next step toward a clinical revolution? Expert review of hematology. 2020;13(5):533-43. [CrossRef]

- Gardner R, Wu D, Cherian S, Fang M, Hanafi L-A, Finney O, et al. Acquisition of a CD19-negative myeloid phenotype allows immune escape of MLL-rearranged B-ALL from CD19 CAR-T-cell therapy. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology. 2016;127(20):2406-10. [CrossRef]

- Jordaens S, Cooksey L, Freire Boullosa L, Van Tendeloo V, Smits E, Mills KI, et al. New targets for therapy: antigen identification in adults with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2020;69(5):867-77. [CrossRef]

- Paavonen K, Ekman N, Wirzenius M, Rajantie I, Poutanen M, Alitalo K. Bmx tyrosine kinase transgene induces skin hyperplasia, inflammatory angiogenesis, and accelerated wound healing. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15(9):4226-33. [CrossRef]

- Coutre SE, Byrd JC, Hillmen P, Barrientos JC, Barr PM, Devereux S, et al. Long-term safety of single-agent ibrutinib in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia in 3 pivotal studies. Blood Adv. 2019;3(12):1799-807. [CrossRef]

- Hillmen P, Eichhorst B, Brown JR, Lamanna N, O'Brien SM, Tam CS, et al. Zanubrutinib Versus Ibrutinib in Relapsed/Refractory Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia and Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma: Interim Analysis of a Randomized Phase III Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(5):1035-45. [CrossRef]

- Brown JR, Eichhorst B, Hillmen P, Jurczak W, Kazmierczak M, Lamanna N, et al. Zanubrutinib or Ibrutinib in Relapsed or Refractory Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(4):319-32. [CrossRef]

- Boullosa LF, Savaliya P, Bonney S, Orchard L, Wickenden H, Lee C, et al. Identification of survivin as a promising target for the immunotherapy of adult B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Oncotarget. 2018;9(3):3853. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, He W, Gao X, Lu X, Xie F, Um S-W, et al. Cullin7 induces docetaxel resistance by regulating the protein level of the antiapoptotic protein Survivin in lung adenocarcinoma cells. Journal of Thoracic Disease. 2023;15(9). [CrossRef]

- Li F, Aljahdali I, Ling X. Cancer therapeutics using survivin BIRC5 as a target: what can we do after over two decades of study? Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research. 2019;38(1):368. [CrossRef]

- Valipour B, Abedelahi A, Naderali E, Velaei K, Movassaghpour A, Talebi M, et al. Cord blood stem cell derived CD16+ NK cells eradicated acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells using with anti-CD47 antibody. Life Sciences. 2020;242:117223. [CrossRef]

- Boncheva VB, Linnebacher M, Kdimati S, Draper H, Orchard L, Mills KI, et al. Identification of the Antigens Recognised by Colorectal Cancer Patients Using Sera from Patients Who Exhibit a Crohn's-like Lymphoid Reaction. Biomolecules. 2022;12(8). [CrossRef]

- Liggins AP, Guinn BA, Banham AH. Identification of lymphoma-associated antigens using SEREX. Methods Mol Med. 2005;115:109-28. [CrossRef]

- Sahin U, Tureci O, Schmitt H, Cochlovius B, Johannes T, Schmits R, et al. Human neoplasms elicit multiple specific immune responses in the autologous host. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92(25):11810-3. [CrossRef]

- Akhmedov M, Martinelli A, Geiger R, Kwee I. Omics Playground: a comprehensive self-service platform for visualization, analytics and exploration of Big Omics Data. NAR Genom Bioinform. 2020;2(1):lqz019.

- Geng H, Brennan S, Milne TA, Chen W-Y, Li Y, Hurtz C, et al. Integrative epigenomic analysis identifies biomarkers and therapeutic targets in adult B-acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer discovery. 2012;2(11):1004-23. [CrossRef]

- Kohlmann A, Kipps TJ, Rassenti LZ, Downing JR, Shurtleff SA, Mills KI, et al. An international standardization programme towards the application of gene expression profiling in routine leukaemia diagnostics: the Microarray Innovations in LEukemia study prephase. Br J Haematol. 2008;142(5):802-7. [CrossRef]

- Haferlach T, Kohlmann A, Wieczorek L, Basso G, Kronnie GT, Béné M-C, et al. Clinical utility of microarray-based gene expression profiling in the diagnosis and subclassification of leukemia: report from the International Microarray Innovations in Leukemia Study Group. Journal of clinical oncology. 2010;28(15):2529-37. [CrossRef]

- Iacobucci I, Mullighan CG. Genetic basis of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2017;35(9):975. [CrossRef]

- Naik A, Lattab B, Qasem H, Decock J. Cancer testis antigens: Emerging therapeutic targets leveraging genomic instability in cancer. Mol Ther Oncol. 2024;32(1):200768. [CrossRef]

- Almeida LG, Sakabe NJ, deOliveira AR, Silva MC, Mundstein AS, Cohen T, et al. CTdatabase: a knowledge-base of high-throughput and curated data on cancer-testis antigens. Nucleic acids research. 2009;37(Database issue):816-9. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed E. Identification of tumour antigens that may facilitate effective cancer detection and treatment: University of Hull; 2023.

- Gislason MH, Demircan GS, Prachar M, Furtwangler B, Schwaller J, Schoof EM, et al. BloodSpot 3.0: a database of gene and protein expression data in normal and malignant haematopoiesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024;52(D1):D1138-D42. [CrossRef]

- Kuleshov MV, Jones MR, Rouillard AD, Fernandez NF, Duan Q, Wang Z, et al. Enrichr: a comprehensive gene set enrichment analysis web server 2016 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(W1):W90-7. [CrossRef]

- Chen EY, Tan CM, Kou Y, Duan Q, Wang Z, Meirelles GV, et al. Enrichr: interactive and collaborative HTML5 gene list enrichment analysis tool. BMC Bioinformatics. 2013;14:128. [CrossRef]

- Szklarczyk D, Gable AL, Lyon D, Junge A, Wyder S, Huerta-Cepas J, et al. STRING v11: protein–protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic acids research. 2019;47(D1):D607-D13. [CrossRef]

- Cheever MA, Allison JP, Ferris AS, Finn OJ, Hastings BM, Hecht TT, et al. The prioritization of cancer antigens: a national cancer institute pilot project for the acceleration of translational research. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2009;15(17):5323-37. [CrossRef]

- Lossos IS, Czerwinski DK, Wechser MA, Levy R. Optimization of quantitative real-time RT-PCR parameters for the study of lymphoid malignancies. Leukemia. 2003;17(4):789-95. [CrossRef]

- Gomarasca M, Maroni P, Banfi G, Lombardi G. microRNAs in the antitumor immune response and in bone metastasis of breast cancer: from biological mechanisms to therapeutics. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2020;21(8):2805. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Chen H-x, Zhou S-y, Wang S-x, Zheng K, Xu D-d, et al. Sp1 and c-Myc modulate drug resistance of leukemia stem cells by regulating survivin expression through the ERK-MSK MAPK signaling pathway. Molecular cancer. 2015;14:1-18. [CrossRef]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402-8. [CrossRef]

- Khan G, Brooks S, Mills K, Guinn B. Infrequent expression of the cancer–testis antigen, PASD1, in ovarian cancer. Biomark Cancer. 2015;7:31-8. [CrossRef]

- Biesterfeld S, Veuskens U, Schmitz F, Amo-Takyi B, Böcking A. Interobserver reproducibility of immunocytochemical estrogen-and progesterone receptor status assessment in breast cancer. Anticancer research. 1996;16(5A):2497-500.

- Deng Z, Hasegawa M, Aoki K, Matayoshi S, Kiyuna A, Yamashita Y, et al. A comprehensive evaluation of human papillomavirus positive status and p16INK4a overexpression as a prognostic biomarker in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. International journal of oncology. 2014;45(1):67-76. [CrossRef]

- Mehta GA, Angus SP, Khella CA, Tong K, Khanna P, Dixon SA, et al. SOX4 and SMARCA4 cooperatively regulate PI3k signaling through transcriptional activation of TGFBR2. NPJ breast cancer. 2021;7(1):1-15. [CrossRef]

- Steinhardt AA, Gayyed MF, Klein AP, Dong J, Maitra A, Pan D, et al. Expression of Yes-associated protein in common solid tumors. Human pathology. 2008;39(11):1582-9. [CrossRef]

- Mostufi-Zadeh-Haghighi G, Veratti P, Zodel K, Greve G, Waterhouse M, Zeiser R, et al. Functional Characterization of Transforming Growth Factor-β Signaling in Dasatinib Resistance and Pre-BCR+ Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Cancers. 2023;15(17):4328. [CrossRef]

- Silva WA, Gnjatic S, Ritter E, Chua R, Cohen T, Hsu M, et al. PLAC1, a trophoblast-specific cell surface protein, is expressed in a range of human tumors and elicits spontaneous antibody responses. Cancer Immunity Archive. 2007;7(1).

- Luo X, Ji X, Xie M, Zhang T, Wang Y, Sun M, et al. Advance of SOX transcription factors in hepatocellular carcinoma: From role, tumor immune relevance to targeted therapy. Cancers. 2022;14(5):1165. [CrossRef]

- Mali RS, Kapur S, Kapur R. Role of Rho kinases in abnormal and normal hematopoiesis. Current opinion in hematology. 2014;21(4):271. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Gao X, Tian X. High expression of long intergenic non-coding RNA LINC00662 contributes to malignant growth of acute myeloid leukemia cells by upregulating ROCK1 via sponging microRNA-340-5p. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2019;859:172535. [CrossRef]

- Pan T, Wang S, Feng H, Xu J, Zhang M, Yao Y, et al. Preclinical evaluation of the ROCK1 inhibitor, GSK269962A, in acute myeloid leukemia. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:1064470. [CrossRef]

- Mali RS, Ramdas B, Ma P, Shi J, Munugalavadla V, Sims E, et al. Rho kinase regulates the survival and transformation of cells bearing oncogenic forms of KIT, FLT3, and BCR-ABL. Cancer Cell. 2011;20(3):357-69. [CrossRef]

- Tamayo E, Alvarez P, Merino R. TGFβ superfamily members as regulators of B cell development and function—implications for autoimmunity. International journal of molecular sciences. 2018;19(12):3928. [CrossRef]

- Vicioso Y, Gram H, Beck R, Asthana A, Zhang K, Wong DP, et al. Combination Therapy for Treating Advanced Drug-Resistant Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Cancer Immunology Research. 2019;7(7):1106-19. [CrossRef]

- Rouce RH, Shaim H, Sekine T, Weber G, Ballard B, Ku S, et al. The TGF-β/SMAD pathway is an important mechanism for NK cell immune evasion in childhood B-acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2016;30(4):800-11. [CrossRef]

- Khoury H, Pinto R, Meng Y, He R, Wu S, Minden MD. Noggin Overexpression Enhances Leukemic Progenitors Self-Renewal in AML by Abrogating the BMP Pathway Activation. Blood. 2006;108(11):2214-. [CrossRef]

- Chiarini F, Paganelli F, Martelli AM, Evangelisti C. The Role Played by Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway in Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2020;21(3):1098. [CrossRef]

- Cassaro A, Grillo G, Notaro M, Gliozzo J, Esposito I, Reda G, et al. FZD6 triggers Wnt–signalling driven by WNT10BIVS1 expression and highlights new targets in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Hematological Oncology. 2021;39(3):364-79. [CrossRef]

- Yu J, Zheng Y, Dong J, Klusza S, Deng W-M, Pan D. Kibra functions as a tumor suppressor protein that regulates Hippo signaling in conjunction with Merlin and Expanded. Developmental cell. 2010;18(2):288-99. [CrossRef]

- Hill VK, Dunwell TL, Catchpoole D, Krex D, Brini AT, Griffiths M, et al. Frequent epigenetic inactivation of KIBRA, an upstream member of the Salvador/Warts/Hippo (SWH) tumor suppressor network, is associated with specific genetic event in B-cell acute lymphocytic leukemia. Epigenetics. 2011;6(3):326-32. [CrossRef]

- Fun XH, Thibault G. Lipid bilayer stress and proteotoxic stress-induced unfolded protein response deploy divergent transcriptional and non-transcriptional programmes. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids. 2020;1865(1):158449. [CrossRef]

- Liu SX, Xiao HR, Wang GB, Chen XW, Li CG, Mai HR, et al. Preliminary investigation on the abnormal mechanism of CD4(+)FOXP3(+)CD25(high) regulatory T cells in pediatric B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Exp Ther Med. 2018;16(2):1433-41. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi H, Kajiwara R, Kato M, Hasegawa D, Tomizawa D, Noguchi Y, et al. Treatment outcome of children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: the Tokyo Children's Cancer Study Group (TCCSG) Study L04-16. Int J Hematol. 2018;108(1):98-108. [CrossRef]

- Caron E, Aebersold R, Banaei-Esfahani A, Chong C, Bassani-Sternberg M. A case for a human immuno-peptidome project consortium. Immunity. 2017;47(2):203-8. [CrossRef]

- Backert L, Kohlbacher O. Immunoinformatics and epitope prediction in the age of genomic medicine. Genome medicine. 2015;7:1-12. [CrossRef]

- Thomas DA, Massagué J. TGF-β directly targets cytotoxic T cell functions during tumor evasion of immune surveillance. Cancer cell. 2005;8(5):369-80. [CrossRef]

- Chen M, Wang J, Yao SF, Zhao Y, Liu L, Li LW, et al. Effect of YAP Inhibition on Human Leukemia HL-60 Cells. Int J Med Sci. 2017;14(9):902-10. [CrossRef]

- Brown G. Lessons to cancer from studies of leukemia and hematopoiesis. Frontiers in cell and developmental biology. 2022;10:993915. [CrossRef]

| ID | Disease stage | Cytogenetics | WCC (109/L) |

BM blast % | Relapse | Survival post-sample (mo) | Age≠ | Sex | Sample type |

| ALL001 | Diagnosis Ph+ ALL | Ph+ ALL: t(9;22) | 4.9 | 40 | NK | NK | 39 | M | PB |

| ALL002 | Diagnosis T-ALL | 46,XY,t(1;7)(p36;p15) | 232 | 88 | No | Alive (post allo) | 19 | M | PB |

| ALL003 | Diagnosis B-ALL | t(1;19) | 28.6 | 91 | No | Alive | 26 | F | PB |

| ALL004* | Diagnosis T-ALL | Complex karyotype | 591 | NK | No | Died 19mo (post allo) | 19 | M | PB |

| ALL005* | ¶Post-allo T-ALL | No result | NK | NK | No | Died 3.5mo (post allo) | 46 | M | PB |

| ALL007 | Diagnosis Pre B-ALL | Loss of one copy of ETV6 (12p13) and gain of one copy of ABL1 (9q34) by FISH | 8.2 | 92 | No | Alive | 24 | M | PB |

| ALL008 | Diagnosis Pre-B-ALL | 46XY, 5,del(5)(q15q33),dic(9;16)(p11;q11),del(13)(q12q14) | 10.4 | 72 | No | Alive | 19 | M | PB |

| ALL009 | Diagnosis Pre-B-ALL | 46,XY,t(1;7)(q25;q3?5),add(3)(p1?3) | 48.1 | 89.6 | Yes | Died 94mo (post allo, CART) | 19 | M | BM |

| ALL010* | Diagnosis Pre-B-ALL | Complex including t(4;11) | 229.1 | 85 | Yes | Died 3mo | 64 | M | PB |

| ALL011 | Diagnosis Pre-B-ALL | No result – external referral | NK | NK | NK | NK | 19 | F | PB |

| ALL012 | Diagnosis Pre-B-ALL | t(11;14)(q24;q32) | 4.3 | 83 | No | Alive (post allo) | 33 | M | BM |

| ALL014 | Diagnosis Pre-B-ALL | 47,XY,+2,add(2)(p1)[3]/46,XY[47].nucish (CRLF2)x2[100] | 4.9 | 53 | Yes | Alive (post allo & CART) | 56 | M | BM |

| ALL015 | Diagnosis Pre-B-ALL | Gain of one copy of CRLF2 (Xp22.3/Yp11.3) and loss of one copy of CSFR1 (5q32) and EBF1 (5q33.3) detected by FISH | 68.0 | 94 | No | Alive | 20 | F | PB |

| ALL016 | Diagnosis Pre-B-ALL | Hyperdiploid; 56-57 XX +X,+4,+6,+9,+10,+14,+17,+18,+21,+marker | 1.9 | 96 | No | Alive | 27 | F | BM |

| ALL017† | Diagnosis, Pre-B-ALL | No cytogenetics available, no FISH | 3.0 | 96 | No | Alive | 19 | F | PB |

| ALL018† | Diagnosis, T-ALL | Normal cytogenetics, SET/CAN fusion detected by FISH | 58.8 | 74 | No | Alive | 22 | M | PB |

| ALL020 | Diagnosis Pre-B-ALL | 46,XY, t(1;7)(q25;q3?5), add(3)(p1?3) TCF3 ex16-PBX1 ex3 fusion transcript detected |

31.9 | 92 | Yes | Died 34.5mo (Post allo, relapse, salvage chemo then CART & relapse) | 56 | F | PB/BM |

| HV control | Age≠ | Sex | Sample type |

| HV008 | 40 | F | PB |

| HV010 | 22 | M | PB |

| HV012 | 46 | F | PB |

| HV021 | 34 | M | PB |

| HV043 | NK | M | PB |

| CD19+ cells | 18-66 | F | PB |

| Pathway | p-value | q-value | SEREX-identified genes involved in this pathway | Database used |

| Envelope proteins and their potential roles in EDMD physiopathology | 0.0007 | 0.0892 | TCF7L2, WNT2B | Wiki Pathway |

| Hematopoietic stem cell gene regulation | 0.001 | 0.064 | DNMT1, MCL1 | |

| TGFβ signalling pathway | 0.015 | 0.229 | TRAP1, ROCK1, CUL1 | |

| Mitotic spindle | 0.001 | 0.038 | ROCK1, KIF5B, FLNB, KIF1B, MYH10 | MSigDB Hallmark 2020 |

| Notch signalling | 0.007 | 0.117 | TCF7L2, CUL1 | |

| Apoptosis | 0.026 | 0.286 | ROCK1, TIMP1, MCL1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).