Submitted:

17 February 2025

Posted:

18 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. CORTICOSTEROID INJECTIONS

3.2. HIGH VOLUME IMAGE GUIDED INJECTION (HVIGI)

3.2.1. Corticosteroid, local anesthetic, saline

3.2.2. Saline

3.2.3. Aprotinin, saline and local anesthetic

3.3. SCLEROSING AGENTS (POLIDOCANOL)

3.4. HYPEROSMOLAR DEXTROSE

3.5. APROTININ

3.6. HYALURONIC ACID, HA

3.7. AUTOLOGOUS BLOOD INJECTION

3.8. PLATELET RICH PLASMA (PRP)

PRP WITH TENOTOMY

3.9. AUTOLOGOUS CONDITIONED SERUM

3.10. AUTOLOGOUS ADIPOSE-DERIVED STROMAL VASCULAR FRACTION SVF

3.11. COMPARING THE TECHNIQUES

3.12. OTHER THERAPIES

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Longo, U.G.; Ronga, M.; Maffulli, N. Achilles tendinopathy. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2009, 17, 112–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malliaras, P.; Barton, C.J.; Reeves, N.D.; Langberg, H. Achilles and patellar tendinopathy loading programmes : A systematic review comparing clinical outcomes and identifying potential mechanisms for effectiveness. Sports Med. 2013, 43, 267–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfredson, H.; Pietilä, T.; Jonsson, P.; Lorentzon, R. Heavy-load eccentric calf muscle training for the treatment of chronic Achilles tendinosis. Am J Sports Med. 1998, 26, 360–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capasso, G.; Maffulli, N.; Testa, V.; Sgambato, A. Preliminary results with peritendinous potease inhibitor injections in the management of Achilles tendinitis. J Sports Traumatol Rel Res 1993, 15, 37–40. [Google Scholar]

- Aubin, F.; Javaudin, L.; Rochcongar, P. Case report of aprotinin in Achilles tendinopathies with athletes [in French]. J Pharmacie Clinique. 1997, 16, 270–273. [Google Scholar]

- Finnoff, J.T.; Fowler, S.P.; Lai, J.K.; et al. Treatment of chronic tendinopathy with ultrasound-guided needle tenotomy and platelet-rich plasma injection. PM R. 2011, 3, 900–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owens, R.F., Jr.; Ginnetti, J.; Conti, S.F.; Latona, C. Clinical and magnetic resonance imaging outcomes following platelet rich plasma injection for chronic midsubstance Achilles tendinopathy. Foot Ankle Int. 2011, 32, 1032–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monto, R.R. Platelet rich plasma treatment for chronic Achilles tendinosis. Foot Ankle Int. 2012, 33, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrero, G.; Fabbro, E.; Orlandi, D.; et al. Ultrasound-guided injection of platelet-rich plasma in chronic Achilles and patellar tendinopathy. J Ultrasound. 2012, 15, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deans, V.M.; Miller, A.; Ramos, J. A prospective series of patients with chronic Achilles tendinopathy treated with autologous-conditioned plasma injections combined with exercise and therapeutic ultrasonography. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2012, 51, 706–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resteghini, P.; Yeoh, J. High-volume injection in the management of recalcitrant mid-body Achilles tendinopathy: A prospective case series assessing the influence of neovascularity and outcome. International Musculoskeletal Medicine 2012, 34, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maffulli, N.; Spiezia, F.; Longo, U.G.; Denaro, V.; Maffulli, G.D. High volume image guided injections for the management of chronic tendinopathy of the main body of the Achilles tendon. Phys Ther Sport. 2013, 14, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, P.C. The use of high-volume image-guided injections (HVIGI) for Achilles tendinopathy – A case series and pilot study. International Musculoskeletal Medicine 2014, 36, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, T.G.; Miller, L.L.; Mygind-Klavsen, B.; Lind, M. The effect of high-volume image-guided injection in the chronic non-insertional Achilles tendinopathy: A retrospective case series. J Exp Orthop. 2020, 7, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohberg, L.; Alfredson, H. Ultrasound guided sclerosis of neovessels in painful chronic Achilles tendinosis: Pilot study of a new treatment. Br J Sports Med. 2002, 36, 173–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohberg, L.; Alfredson, H. Ultrasound guided sclerosis of neovessels in painful chronic Achilles tendinosis: Pilot study of a new treatment. Br J Sports Med. discussion 176-7. 2002, 36, 173–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kearney, R.S.; Parsons, N.; Costa, M.L. Achilles tendinopathy management: A pilot randomised controlled trial comparing platelet-richplasma injection with an eccentric loading programme. Bone Joint Res. 2013, 2, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyaswamy, B.; Vaghela, M.; Alderton, E.; Majeed, H.; Limaye, R. Early Outcome of a Single Peri-Tendinous Hyaluronic Acid Injection for Mid-Portion Non-Insertional Achilles Tendinopathy - A Pilot Study. Foot (Edinb). 2021, 49, 101738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.S.; Gelbke, M.K.; Mattson, S.L.; Anderson, M.W.; Hurwitz, S.R. Fluoroscopically guided low-volume peritendinous corticosteroid injection for Achilles tendinopathy. A safety study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004, 86, 802–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orchard, J.; Massey, A.; Brown, R.; Cardon-Dunbar, A.; Hofmann, J. Successful management of tendinopathy with injections of the MMP-inhibitor aprotinin. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008, 466, 1625–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Sterkenburg, M.N.; de Jonge, M.C.; Sierevelt, I.N.; van Dijk, C.N. Less Promising Results with Sclerosing Ethoxysclerol Injections for Midportion Achilles Tendinopathy: A Retrospective Study. The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2010, 38, 2226–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mautner, K.; Colberg, R.E.; Malanga, G.; et al. Outcomes after ultrasound-guided platelet-rich plasma injections for chronic tendinopathy: A multicenter, retrospective review. PM R. 2013, 5, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guelfi, M.; Pantalone, A.; Vanni, D.; Abate, M.; Guelfi, M.G.; Salini, V. Long-term beneficial effects of platelet-rich plasma for non-insertional Achilles tendinopathy. Foot Ankle Surg. 2015, 21, 178–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Wehren, L.; Pokorny, K.; Blanke, F.; Sailer, J.; Majewski, M. Injection with autologous conditioned serum has better clinical results than eccentric training for chronic Achilles tendinopathy. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2019, 27, 2744–2753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, M.; Wong, A.; Taunton, J. Favorable outcomes after sonographically guided intratendinous injection of hyperosmolar dextrose for chronic insertional and midportion achilles tendinosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010, 194, 1047–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynen, N. Treatment of chronic tendinopathies with peritendinous hyaluronan injections under sonographic guidance – an interventional, prospective, single-arm, multicenter study. OUP Orthopäedische und Unfallchirgurgische Praxis. 2012, 1, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filardo, G.; Kon, E.; Di Matteo, B.; et al. Platelet-rich plasma injections for the treatment of refractory Achilles tendinopathy: Results at 4 years. Blood Transfus. 2014, 12, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, N.J.; Ryan, M.B.; Taunton, J.E.; Gillies, J.H.; Wong, A.D. Sonographically guided intratendinous injection of hyperosmolar dextrose to treat chronic tendinosis of the Achilles tendon: A pilot study. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007, 189, W215–W220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, O.; O'Dowd, D.; Padhiar, N.; et al. High volume image guided injections in chronic Achilles tendinopathy. Disabil Rehabil. 2008, 30, 1697–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, J.; Chan, O.; Crisp, T.; et al. The short-term effects of high volume image guided injections in resistant non-insertional Achilles tendinopathy. J Sci Med Sport. 2010, 13, 295–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaweda, K.; Tarczynska, M.; Krzyzanowski, W. Treatment of Achilles tendinopathy with platelet-rich plasma. Int J Sports Med. 2010, 31, 577–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fogli, M.; Giordan, N.; Mazzoni, G. Efficacy and safety of hyaluronic acid (500-730kDa) Ultrasound-guided injections on painful tendinopathies: A prospective, open label, clinical study. Muscles Ligaments Tendons, J. 2017, 7, 388–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frizziero, A.; Vittadini, F.; Oliva, F.; et al. THU0492 efficacy of us-guided hyaluronic acid injections in achilles and patellar mid-portion tendinopathies: A prospective multicentric clinical trial. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2019, 78, 536–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredberg, U.; Bolvig, L.; Pfeiffer-Jensen, M.; Clemmensen, D.; Jakobsen, B.W.; Stengaard-Pedersen, K. Ultrasonography as a tool for diagnosis, guidance of local steroid injection and, together with pressure algometry, monitoring of the treatment of athletes with chronic jumper's knee and Achilles tendinitis: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Scand J Rheumatol. 2004, 33, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfredson, H.; Ohberg, L. Sclerosing injections to areas of neo-vascularisation reduce pain in chronic Achilles tendinopathy: A double-blind randomised controlled trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2005, 13, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.; Orchard, J.; Kinchington, M.; et al. Aprotinin in the management of Achilles tendinopathy: A randomised controlled trial. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2006, 40, 275–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Vos, R.J.; Weir, A.; van Schie, H.T.; et al. Platelet-rich plasma injection for chronic Achilles tendinopathy: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010, 303, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Jonge, S.; de Vos, R.J.; Weir, A.; et al. One-year follow-up of platelet-rich plasma treatment in chronic Achilles tendinopathy: A double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2011, 39, 1623–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yelland, M.J.; Sweeting, K.R.; Lyftogt, J.A.; et al. Prolotherapy injections and eccentric loading exercises for painful Achilles tendinosis: A randomised trial. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2011, 45, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, J.; Rowlands, D.; Highet, R. Autologous blood injection to treat achilles tendinopathy? A randomized controlled trial. J Sport Rehabil. 2012, 21, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, K.J.; Fulcher, M.L.; Rowlands, D.S.; Kerse, N. Impact of autologous blood injections in treatment of mid-portion Achilles tendinopathy: Double blind randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2013, 346, f2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krogh, T.P.; Ellingsen, T.; Christensen, R.; Jensen, P.; Fredberg, U. Ultrasound-Guided Injection Therapy of Achilles Tendinopathy With Platelet-Rich Plasma or Saline: A Randomized, Blinded, Placebo-Controlled Trial. The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2016, 44, 1990–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Girolamo, L.; Grassi, M.; Viganò, M.; Orfei, C.P.; Montrasio, U.A.; Usuelli, F. Treatment of Achilles Tendinopathy with Autologous Adipose-derived Stromal Vascular Fraction: Results of a Randomized Prospective Clinical Trial. Orthop J Sports Med. 2016, 4 (Suppl. S4), 2325967116S00128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynen, N.; De Vroey, T.; Spiegel, I.; Van Ongeval, F.; Hendrickx, N.J.; Stassijns, G. Comparison of Peritendinous Hyaluronan Injections Versus Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy in the Treatment of Painful Achilles' Tendinopathy: A Randomized Clinical Efficacy and Safety Study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017, 98, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boesen, A.P.; Hansen, R.; Boesen, M.I.; Malliaras, P.; Langberg, H. Effect of High-Volume Injection, Platelet-Rich Plasma, and Sham Treatment in Chronic Midportion Achilles Tendinopathy: A Randomized Double-Blinded Prospective Study. Am J Sports Med. 2017, 45, 2034–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usuelli, F.G.; Grassi, M.; Maccario, C.; et al. Intratendinous adipose-derived stromal vascular fraction (SVF) injection provides a safe, efficacious treatment for Achilles tendinopathy: Results of a randomized controlled clinical trial at a 6-month follow-up. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2018, 26, 2000–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boesen, A.P.; Langberg, H.; Hansen, R.; Malliaras, P.; Boesen, M.I. High volume injection with and without corticosteroid in chronic midportion achilles tendinopathy. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2019, 29, 1223–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Vlist, A.C.; van Oosterom, R.F.; van Veldhoven, P.L.J.; et al. Effectiveness of a high volume injection as treatment for chronic Achilles tendinopathy: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2020, 370, m3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearney, R.S.; Ji, C.; Warwick, J.; et al. Effect of Platelet-Rich Plasma Injection vs Sham Injection on Tendon Dysfunction in Patients With Chronic Midportion Achilles Tendinopathy: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2021, 326, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannsen, F.; Olesen, J.L.; Øhlenschläger, T.F.; et al. Effect of Ultrasonography-Guided Corticosteroid Injection vs Placebo Added to Exercise Therapy for Achilles Tendinopathy: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2022, 5, e2219661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinman, M.; Gross, A.E. Achilles tendon rupture following steroid injection. Report of three cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1983, 65, 1345–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rochcongar, P.; Thoribe, B.; Le Beux, P.; Jan, J. Tendinopathie calcanéenne et sport : Place des injections d'aprotinine. Science & Sports 2005, 20, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, U.G.; Rittweger, J.; Garau, G.; et al. No influence of age, gender, weight, height, and impact profile in achilles tendinopathy in masters track and field athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2009, 37, 1400–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maffulli, N.; Longo, U.G.; Denaro, V. Novel approaches for the management of tendinopathy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010, 92, 2604–2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orchard, J.; Massey, A.; Rimmer, J.; Hofman, J.; Brown, R. Delay of 6 weeks between aprotinin injections for tendinopathy reduces risk of allergic reaction. J Sci Med Sport. 2008, 11, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anitua, E.; Sánchez, M.; Nurden, A.T.; Nurden, P.; Orive, G.; Andía, I. New insights into and novel applications for platelet-rich fibrin therapies. Trends Biotechnol. 2006, 24, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardie, K.A.; Bergeson, A.J.; Anderson, M.C.; Erie, A.C.; Van Demark, R.E. Flexor tendon rupture following repeated corticosteroid injections for carpal tunnel syndrome: A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep 2024, 123, 110277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, T.S.S.; van Linschoten, R.; Vicenzino, B.; Weir, A.; de Vos, R.J. Terminating Corticosteroid Injection in Tendinopathy? Hasta la Vista, Baby. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2024, 54, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, S.; Chan, O.; King, J.; et al. High volume image-guided Injections for patellar tendinopathy: A combined retrospective and prospective case series. Muscles Ligaments Tendons, J. 2014, 4, 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llombart, R.; Mariscal, G.; Barrios, C.; Llombart-Ais, R. The Best Current Research on Patellar Tendinopathy: A Review of Published Meta-Analyses. Sports. 2024, 12, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, J.; Jeong Hwan, S.; Myeng Hwan, K.; Young Joo, S. The Effect of Paratendinous Aprotinin Injection in Patients with Rotator Cuff Tendinitis. Journal of the Korean Academy of Rehabilitation Medicine 2008, 32, 56. [Google Scholar]

- Maffulli, N.; Del Buono, A.; Oliva, F.; Testa, V.; Capasso, G.; Maffulli, G. High-Volume Image-Guided Injection for Recalcitrant Patellar Tendinopathy in Athletes. Clin J Sport Med. 2016, 26, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agostini, F.; de Sire, A.; Paoloni, M.; et al. Effects of hyaluronic acid injections on pain and functioning in patients affected by tendinopathies: A narrative review. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2022, 35, 949–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, H.; Reeves, K.D.; Bennett, C.J.; Bicknell, S.; Cheng, A.L. Dextrose Prolotherapy Versus Control Injections in Painful Rotator Cuff Tendinopathy. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2016, 97, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Rabago, D.; Chung, V.C.; Reeves, K.D.; Wong, S.Y.; Sit, R.W. Effects of Hypertonic Dextrose Injection (Prolotherapy) in Lateral Elbow Tendinosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2022, 103, 2209–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resteghini, P.; Khanbhai, T.A.; Mughal, S.; Sivardeen, Z. Double-blind randomized controlled trial, injection of autologous blood in the treatment of chronic patella tendinopathy—A pilot study. Clin. J. Sport Med. 2016, 26, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braaksma, C.; Otte, J.; Wessel, R.N.; Wolterbeek, N. Investigation of the efficacy and safety of ultrasound standardized autologous blood injection as treatment for lateral epicondylitis. Clin Shoulder Elb. 2022, 25, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raeissadat, S.A.; Rayegani, S.M.; Jafarian, N.; Heidari, M. Autologous conditioned serum applications in the treatment of musculoskeletal diseases: A narrative review. Future Sci, O.A. 2022, 8, FSO776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ipek, D.; Çalbıyık, M.; Zehir, S. Intratendinous Injection of Autologous Conditioned Serum for Treatment of Lateral Epicondylitis of the Elbow: A Pilot Study. Arch Iran Med. 2022, 25, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barman, A.; Sinha, M.K.; Sahoo, J.; et al. Platelet-rich plasma injection in the treatment of patellar tendinopathy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Knee Surg Relat Res. 2022, 34, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masiello, F.; Pati, I.; Veropalumbo, E.; Pupella, S.; Cruciani, M.; De Angelis, V. Ultrasound-guided injection of platelet-rich plasma for tendinopathies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood Transfus. 2023, 21, 119–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargel, İ.; Tuncel, A.; Baysal, N.; Hartuç-Çevik, İ.; Korkusuz, F. Autologous Adipose-Derived Tissue Stromal Vascular Fraction (AD-tSVF) for Knee Osteoarthritis. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23, 13517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author | Research type | Modality of administration | Agent, dosing, timing | Evaluation tools | Timing | Results | Observations |

| Capasso, 1993 [4] |

Prospective, longitudinal, interventional, case series, 77 tendons | Peritendinous | Aprotinin (62 500 kIU), 4 injections | Patient satisfaction | N/A | 78% improvement | 7% failure |

| Aubin, 1997 [5] | Prospective, longitudinal, interventional, case series, 62 tendons | Peritendinous | Aprotinin (20 000 kIU), 4 injections | Patient satisfaction | N/A | 74% improvement | 16% failure |

| Kleinman, 1983 [51] | Retrospective, case report, 3 tendons | Intratendinous | Corticosteroids | Pain Return to previous activities |

2 -3 weeks | Tendon rupture | Avoid administration |

| Ohberg, 2002 [15] | Prospective, longitudinal, interventional, pilot, 10 tendons | Intratendinous, within the neovascularization area, possible repetition after 3 – 6 weeks, up to 4 injections | Polidocanol, 5 mg/ml, 2 – 4 ml | Ultrasound neovascularization Pain on VAS Patient satisfaction |

Baseline 6 months |

8/10 patients reduced neovascularization and pain | No side effects |

| Ohberg, 2003 [16] | Prospective, longitudinal, interventional, pilot, 11 tendons | Intratendinous, within the neovascularization area, possible repetition at 3 – 6 weeks, up to 4 injections | Polidocanol, 5mg/ml, 2 ml | Pain on VAS Ultrasound (neovascularization) Patient satisfaction |

Baseline, 3 – 6 weeks, 8 months (mean) |

8/11 improved pain | No side effects |

| Gill, 2004 [19] | Retrospective cohort study, therapeutic, 43 pts | Fluoroscopically guided corticosteroid injections into the space surrounding the Achilles tendon | Corticosteroid | Complications | 2 years | Pain and function improvement | No major complications and one minor complication |

| Fredberg, 2004 [34] | Prospective, randomized, double blind, placebo controlled, 24 tendons | Peritendinous, as close to the lesion as possible, US guided | Corticosteroid, 3 injections (days 0, 7 and 21): 4 ml (20 mg triamcinolone + lidocaine) | Walking pain (NRS), Pressure-pain detection thresholds, US (tendon thickness) |

Days 0, 7, 21, 28, 6 months |

Tendon thickness and pain decreased in the CS group at 1 and 3 weeks and increased lightly at 6 months | 4 days’ rest after injection. Complications: local atrophy, reversible. 25% referred to surgery at 6 months |

| Rochcongar, 2005 [52] | Non-randomized prospective trial, 128 tendons (athlets) | Peritendinous, 20 000 kIU, 5 weekly injections |

Six groups: Aprotinine Physical exercise Orthosis NSAIDs per os Cryotherapy NSAIDs Surgery |

Return to sport | 2 – 3 months | 82% of aprotinine patients returned to previous level of sport | Not important |

| Alfredson, 2005 [35] | Prospective, randomized, controlled, double-blind, 20 tendons | Intratendinous, right into the neovascularization area, ultrasound guided | Polidocanol (5 mg/ml) 1 – 4 ml versus blind (lidocaine + adrenaline), 2 treatments 3 – 6 weeks apart | Pain on activity, US exam (neo-vascularization, tendon structure) Patient satisfaction |

3 months | Significant improvement in all parameters in the polidocanol group No improvement in the blind group |

|

| Brown, 2006 [36] | Prospective, randomized, double-blinded, placebo controlled, 26 pts, 33 tendons | Peritendinous, 3 weekly injections | Aprotinin + exercise versus placebo + exercise, 3 weekly injections | Primary outcome: VISA-A, Secondary outcomes: Pain on VAS Function (no of single heel raises) Return to previous level of sport Patient satisfaction |

3 weeks, 1, 3 and 12 months |

Both groups improved all parameters at all moments, with better results for aprotinin group, but not significant | No side effects, no allergic reaction. Lack of significance: groups were too small |

| Maxwell, 2007 [28] | Prospective, before and after, a sub-group of 23 mid-portion tendinopathy | Intratendinous, US-guided within the area of abnormality | 3 mL of a mixture of 2 mL 2% lignocaine and 1 mL of 50% dextrose, giving a 25% dextrose solution One injection every 6 weeks, maximum 4 injections |

GSUS, color flow-DUS, VAS at rest, daily activity and strenuous activity |

Baseline, 6 weeks after completion, 12 months |

VAS at rest, daily and strenuous activity improved significantly after therapy US features improved |

Lack of significance may be due to too smaller a size. |

| Chan, 2008 [29] |

Prospective, longitudinal, interventional, pre- and post-treatment, 21 tendons | Peritendinous, ultrasound guidance, on the anterior aspect of the tendon | A mixture of 10 ml 0.5% bupivacaine hydrochloride and 25 mg of hydrocortisone acetate, followed by 4 x 10 ml of normal saline. | VISA-A Pain on VAS |

Baseline 2 weeks 30 weeks |

Significant improvement of pain and function on short- and long-term | |

| Orchard, 2008 [20] | Retrospective, longitudinal, interventional, cohort study, 149 tendons | Peritendinous, palpatory guidance | Solution 5 mL (aprotinin 30 000 kIU and 2 ml local anesthetic), 2 – 3 injections |

Patient satisfaction questionnaire | 3 – 54 months after the first injection | 61% improved, 3% failure |

Itching (25%) Rush (7%) Uncommon (sweating, nausea, allergy, headache) |

| Yelland, 2009 [39] | single-blinded randomised clinical trial, 40 tendons | tender points in the subcutaneous tissues adjacent to the tendon | Prolotherapy (5 ml solution glucose + local anesthetic) 4 to 12 weekly injections versus Eccentric training versus Eccentic training + prolotherapy |

VISA-A Patient satisfaction (Likert scale) Economic costs |

Baseline 12 weeks (completion) 6 and 12 months |

Intra-group: significant improvement at all moments Inter-group: at 6 months the combined therapy improved better Economic: combined therapy best value for money |

|

| Ryan, 2009 [25] | Prospective, longitudinal, interventional, 86 tendons | Intratendon, US guided | Dextrose (2 ml 25% + lignocaine), 1 – 3 sites, repeated at 6 weeks if necessary | Pain Ultrasound aspect Number of injections |

Baseline 6 weeks 28 months |

Pain improved at all moments 28 months: US aspect improved |

Number of injections: between 1 and 5 |

| De Vos, 2010 [37], De Jonge, 2011 [38] |

Prospective, randomized, double-blind, longitudinal, placebo-controlled trial, 54 pts | intratendinous | PRP (4 mL) versus saline, 3 different puncture locations. | VISA-A Patient satisfaction, return to sports, Adherence to the eccentric exercises, Ultrasound exam |

Baseline, 6, 12 and 24 weeks, One year |

Both groups improved significantly at all moments No significant differences between groups |

No benefit for PRP group |

| Van Sterkenburg, 2010 [21] | Retrospective, longitudinal, interventional, 53 tendons | Intratendon, into the hypervascularity area | Polidocanol (2 – 4 ml), at 6 weeks interval and a maximum of 5 sessions | Pain on VAS | 6 weeks (short term), 3,9 years (midterm) |

44% pain free 42% same amount of pain 14% worse pain |

No high beneficial value |

| Humphrey, 2010 [30] | Prospective, longitudinal, interventional, pre- and post-treatment, 11 tendons | Peritendinous, on the anterior aspect, ultrasound guided | A mixture of 10 mL 0.5% bupivacaine hydrochloride and 25 mg of hydrocortisone acetate, followed by 4 × 10 mL of normal saline | VISA-A Ultrasound morphology |

3 weeks | Significant improvement in all aoutcomes, with thickness reduction on US | No serious event |

| Gaweda, 2010 [31] | Prospective, observational, before after, 15 tendons | Intratendinous, US-guided within the hypoechogenic area | PRP, 3 mL, one injection | AOFAS* scale, VISA-A scale US assessment |

Baseline, 6 weeks, 3,6 and 18 months | All parameters improved significantly at all moments | |

| Finnoff, 2011 [6] | Prospective, longitudinal, observational, case series, 11 tendons | PRP, intra-tendon | US-guided percutaneous needle tenotomy and one PRP injection (2,5 – 3,5 mL) | Pain Function US morphology |

Baseline, 14 months (mean) |

Improvement Maximum effect: 4 months |

PRP augmented the benefits of tenotomy |

| Owens, 2011 [7] | Retrospective, longitudinal, interventional, case series, 11 tendons | Intratendinous, US guided, | PRP, 6 mL | FAAM*, FAAMS*, SF-8*, MRI, |

Pre- and post-injection 13.9 (range, 10.1 to 19.5) months | Modest improvement in clinical scales. Minor MRI changes. | |

| Monto, 2012 [8] | Prospective, longitudinal, Interventional, case series, 30 tendons |

Intratendinous, US-guided into the lesion, diamond injection pattern | PRP, 4 mL | AOFAS MRI Patient satisfaction |

1, 2, 3, 6, 12, and 24 months MRI at 6 months |

Significant improvement in pain, function, return to activities MRI: structural improvement |

No placebo group |

| Pearson, 2012 [40] | Prospective randomized controlled trial, 33 tendons | Autologous blood injection, peritendinous | Eccentric training + autologous blood injection (peritendinous) versus eccentric training alone, second injection 6 weeks apart | Pain VISA-A Ratings of perceived discomfort during and after the injection. |

6, 12 weeks | 6 weeks, inconsistent improvement in pain and function 12 weeks, moderate improvement |

Discomfort at injection site during the procedure and up to 48 hours after |

| Ferrero, 2012 [9] | Prospective, longitudinal, interventional, case series, 30 tendons | Intratendinous, US-guidance | PRP, 6 mL, 2 injections 3 weeks apart | VISA-A Pain (VAS) US Patient satisfaction |

Baseline, 20 days, 6 months |

Minimal improvement VISA-A, pain and US appearance at 20 days, significant improvement at 6 months, | Moderate post-procedural pain (average 4 days) |

| Deans, 2012 [10] | Case series, prospective, 28 tendons | Intratendinous, into the maximum pain area | Autologous-conditioned plasma, one or two injections (6 weeks apart)s | Pain Function Quality of life |

Baseline, 6 weeks |

Improvement in all parameters | |

| Resteghini, 2012 [11] | Prospective, longitudinal, interventional, case series, 32 tendons | Peritendon, US guided | 40 ml (25 mg of hydrocortisone, 5 ml of 1% lignocaine and up to 40 ml of normal saline) |

Pain (VAS) VISA-A Ultrasound exam |

Baseline 1 and 3 months |

Pain and function improved at all moments US exam improved at 3 months |

6% rate of failure |

| Lynen, 2012 [26] | Longitudinal, interventional, prospective, single-arm, multicenter trial, 19 tendons | Peritendon, US guided | Hyaluronic acid (40 mg/2 ml + mannitol), 2 weekly injections | Pain US exam |

Baseline 5 and 12 weeks |

Improvement in pain and US structure | None |

| Mautner, 2013 [22] | Retrospective, interventional, cross-sectional, 27 tendons | Intratendinous, US-guided | One or more injections, according to clinical evolution | Pain (at rest, function) Patient satisfaction |

15 months (average) | All patients: at least moderate improvement. 96% mostly complete improvement |

|

| Maffulli, 2013 [12] | Prospective, longitudinal, interventional, case series, 94 tendons (athletes) | Peritendinous, on the anterior side, US-guided | 10 mL mixture (bupivacaine and aprotinin 62 500 kIU), eventually followed by another injection, 2 weeks, with corticosteroid instead aprotinin | VISA-A, Ultrasound (grey-scale, Doppler) Return to athletic activity |

Baseline, 2 weeks, 1 year |

60% required a second injection One year: 68% success (return to previous level), 11% returned to a lower level |

9% failure (surgery) |

| Bell, 2013 [41] | Prospective, randomised controlled trial, 53 tendons | Autologous blood injection, peritendinous, | Standard eccentric training alone versus standard eccentric training + autologous blood injections, 2 injections 4 weeks apart | VISA-A Perceived rehabilitation (Likert scale) The ability to return to sport. |

6 months | Both groups improved significantly, | No differences between groups |

| Kearney, 2013 [17] | Randomized longitudinal, interventional, controlled trial, pilot trial, 20 tendons | Intratendinous administration (peppering, single-skin penetration and 5 penetrations of the tendon) | PRP (3 – 5 mL) versus excentric exercise program | VISA-A Pain (VAS) EQ-5D for general health |

Baseline, 6 weeks, 3 and 6 months | No significant differences | |

| Filardo, 2014 [27] | Prospective, longitudinal, interventional, 37 tendons | Intratendinous, multiple perforations, US-guided | PRP, 5 mL, 3 injections every 2 weeks | Blazina score, VISA-A, EQ-VAS for general health, Tegner score |

Baseline, 2 and 6 months, 4 years |

Improvement on all parameters, in the short and medium term Maintenance at 4 years |

|

| Guelfi, 2014 [23] | Retrospective, interventional, 98 tendons | Intra- and peritendon injection, US guided | PRP, one injection | Blazina score Pain VISA-A |

Baseline, 3 weeks, 3 and 6 months 50 months |

||

| Wheeler, 2014 [13] | Prospective, longitudinal, interventional, pre- and post-treatment, case series, 14 tendons |

Peritendon, on the anterior side, US guided | HVIGI 50 ml (10 ml lidocaine + 40 ml saline), one injection | Pain VISA-A |

Baseline 347 days mean follow-up |

Significant improvement in pain and function | 14% failure (went to surgery) |

| Krogh, 2016 [42] | Randomized placebo-controlled, single blind trial, 24 tendons | Intratendinous, ultrasound-guided injection. |

PRP (6 mL) versus saline; peppering technique (3 to 4 skin portals and about 7 tendon perforations evenly distributed in the thickest part of the tendon) | VISA-A Pain at rest, when walking, and when the Achilles tendon was squeezed. Ultrasound: color Doppler activity and tendon thickness |

Baseline 3, 6 and 12 months |

No differences between groups at 3 months for all parameters, except for the tendon thickness, that increased in PRP-group at 3 months | A huge drop-out rate (54%) due to lack of results for both groups at 12 months |

| Girolamo, 2016 [43] | Prospective, controlled, randomized, 56 tendons | Intra-tendon and peritendon | adipose tissue SVF versus PRP, one injection | Pain (VAS) VISA-A SF-36 MRI/ultrasond |

Baseline, 15, 30, 60, 120 and 180 days | Both groups improved at all moments SVF patients improved more rapidly (15 days) 6 months: imagistic were equal |

|

| Lynen, 2016 [44] | Prospective, randomized controlled, blinded-observer trial, 59 tendons | Peritendon | Hyaluronic acid HA (40 mg/2ml + mannitol), 2 weekly injections versus ESWT (3 weekly sessions) |

Pain (VAS) VISA-A Ultrasound exam |

Baseline 4 weeks, 3 and 6 months |

Intra-group: improvement in both groups Inter-group: HA group better result on all parameters |

Few adverse effects in both groups |

| Fogli, 2017 [32] | Prospective, open-label, single-center study, 34 tendons | Peritendon, on the anterior aspect | Hyaluronic acid (40 mg/2ml + mannitol), 2 weekly injections | Pain US exam Clinical symptoms Safety |

Baseline Days 7, 14 and 56 |

Pain and clinical symptoms improved at all moments. On 14 and 56 days, reduction of tendon thickness |

No adverse effects |

| Boesen, 2017 [45] | double-blinded, randomized prospective trial, 60 tendons | Peritendinous, on anterior aspect, ultrasound guided | HVIGI (one injection corticosteroid+anesthetic +saline) PRP (4 injections, every 2 weeks) Saline |

Primary outcome: VISA-A Secondary outcome: VAS, satisfaction Ultrasound: tendon thickness and color Doppler |

Baseline, 6, 12 and 24 weeks | Both HVIGI and PRP improve parameters at all moments. HVIGI was more effective than PRP on pain, function and satisfaction at 6 and 12 weeks, but not at 24 weeks |

|

| Usuelli, 2018 [46] | Double blinded RCT, 44 pts | Intra-tendon and peritendon | One injection either of PRP or adipose tissue SVF | Pain on VAS VISA-A AOFAS SF-36 US and MRI |

15, 30, 60, 120 and 180 days | All patients improved, SVF group with a faster evolution (15 days) 6 months: equally structural evolution |

|

| Boesen, 2019 [47] | Double blinded, randomized controlled, 28 tendons | Peritendinous, on the anterior side | HVIGI with and without corticosteroid (CS) | Primary outcome: VISA-a Secondary: VAS on weight-bearing, ultrasound (tendon thickness, Doppler), patient satisfaction |

6, 12, 24 weeks | HVIGI with CS improved better in the short term and equally on medium term. | |

| Von Wehren, 2019 [24] | Retrospective, longitudinal, comparative study, 50 tendons | Intratendinous, into the area of maximum pain | Autologous condioned serum (2 mL, 3 weekly injections) versus eccentric training | VISA-A MRI (baseline and 6 months) |

Baseline 6, 12 weeks, 6 months |

VISA-A improved better in autologous conditioned serum group at all moments |

|

| Frizziero, 2019 [33] | Prospective, longitudinal, interventional trial, 26 tendons | Peritendinous, US guided | Hyaluronic acid (20 mg/2 ml; 500-730 kDa), 3 weekly injections | Pain VISA-A Quality of life (EQ-5D-5L) US assessment |

Baseline 14, 45 and 90 days |

Significant improvement in pain and function up to 90 days Structural improvement at 90 days |

None |

| Der Vlist, 2020 [48] | Prospective, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, 80 tendons | Peritendin, on the anterior side, into the area of maximum Doppler flow | 50 mL versus 2 mL mixture of saline and 1% lidocaine | VISA-A. Patient satisfaction, return to sport, Doppler flow |

2, 6, 12, 24 weeks | No benefit for the high-volume group | None |

| Ayyaswamy, 2020 [18] | Prospective, longitudinal, interventional, pilot study, 17 tendons | Peritendon, US-guided | Hyaluronic acid (40mg/2ml with 0.5% mannitol), one injection | Pain (VAS) Manchester-Oxford Foot Questionnaire |

Baseline 2 and 12 weeks |

Significant improvement at all moments | No adverse effects |

| Nielsen, 2020 [14] | Retrospective, longitudinal, interventional, case series, 30 tendons | Peritendon, on the anterior side, US guided | One HVIGI (10 mL of marcaine, 0,5 ml of triamcinolonacetonid and 40 mL of saline) | VISA-A US exam |

Baseline One year |

33% of patiens improved | The low rate might be the result of long duration of symptoms and multiple failures |

| Kearney, 2021 [49] | Randomized placebo-controlled, longitudinal, multicenter clinical trial, 221 tendons | Intratendinous, a single skin portal and 5 penetrations of the tendon |

PRP (3 – 5 mL) versus saline | VISA-A Health-related quality of life assessed (EQ-5D-5L) |

Baseline 3 and 6 months |

No difference between groups at 3 and 6 months | |

| Johansson, 2022 [50] | Double-blinded randomized, controlled, placebo, 100 pts | Peritendinous, US guided | Corticosteroid, 3 injections with an interval of at least 4 weeks versus placebo, followed by exercise | Primary: VISA-A Secondary: pain on VAS, global assessment, US exam (thickness, PDUS) |

1, 2, 3, 6, 12, and 24 months. | Both groups improved. CS group improved better, 6 months. | No deleterious effect of CS |

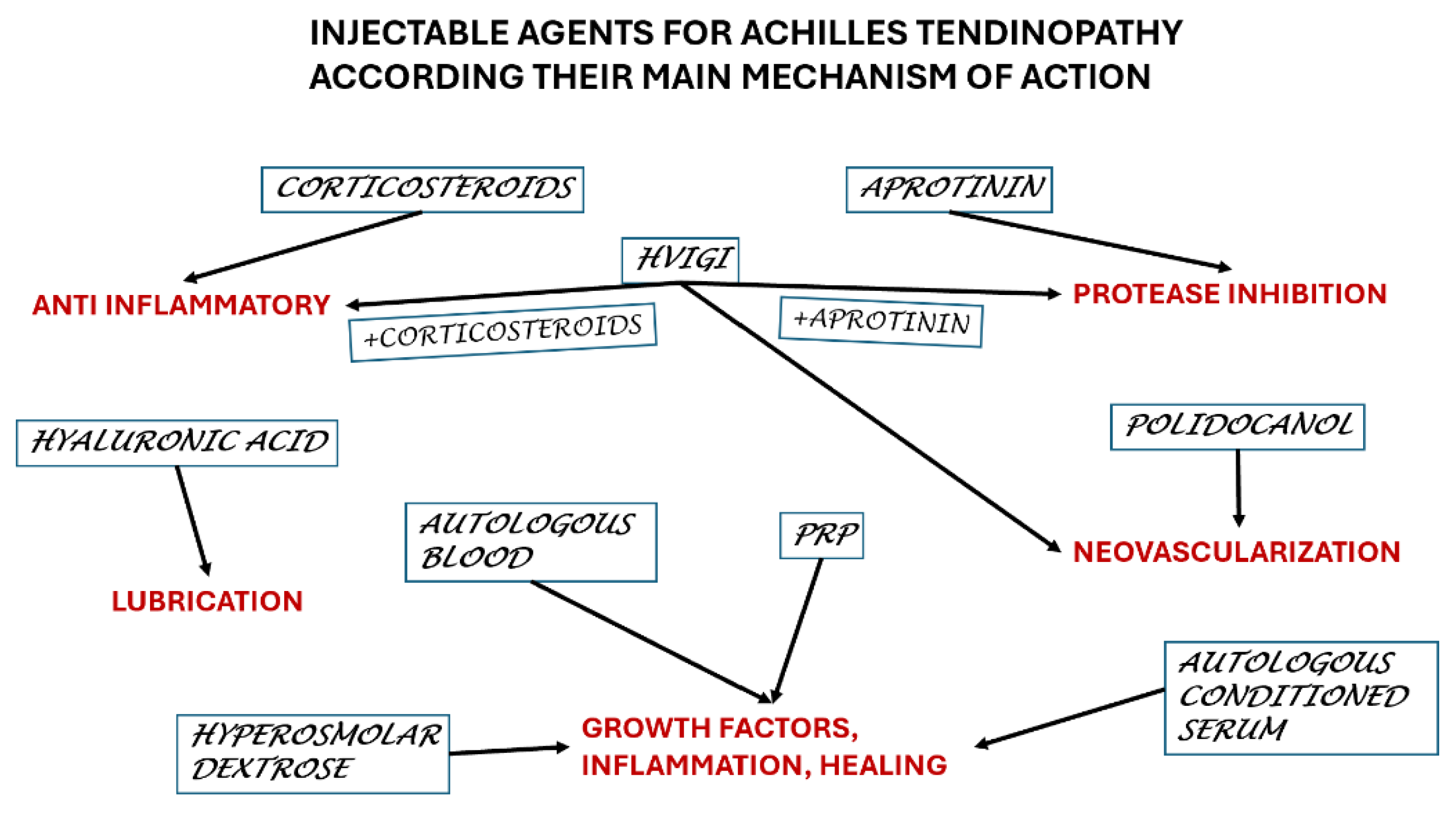

| Agent | Main mechanism | Administration |

| Corticosteroids | Anti-inflammatory | Intra tendon – to be avoided Peritendon - advisable |

| HVIGI a. Corticosteroids b. Saline c. Aprotinin |

Sclerosing agent for neovascularization a. + anti-inflammatory b. No other effect c. Proteolytic |

Peritendon |

| Polidocanol | Sclerosing agent for neovascularization | Peritendon |

| Hyperosmolar dextrose | Inflammatory reaction to promote healing | Intra tendon |

| Aprotinin | Proteolytic | Intra tendon / Peritendon |

| Hyaluronic acid | Lubricating, breaking adhesions | Peritendon |

| Autologous blood | Inflammatory reaction to promote healing | Peritendon |

| PRP | Inflammatory reaction to promote healing | Intra tendon |

| Autologous serum | Inflammatory reaction to promote healing | Intra tendon |

| Autologous adipose-derived stromal vascular fraction | Inflammatory reaction to promote healing | Intra tendon |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).