Submitted:

16 February 2025

Posted:

18 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

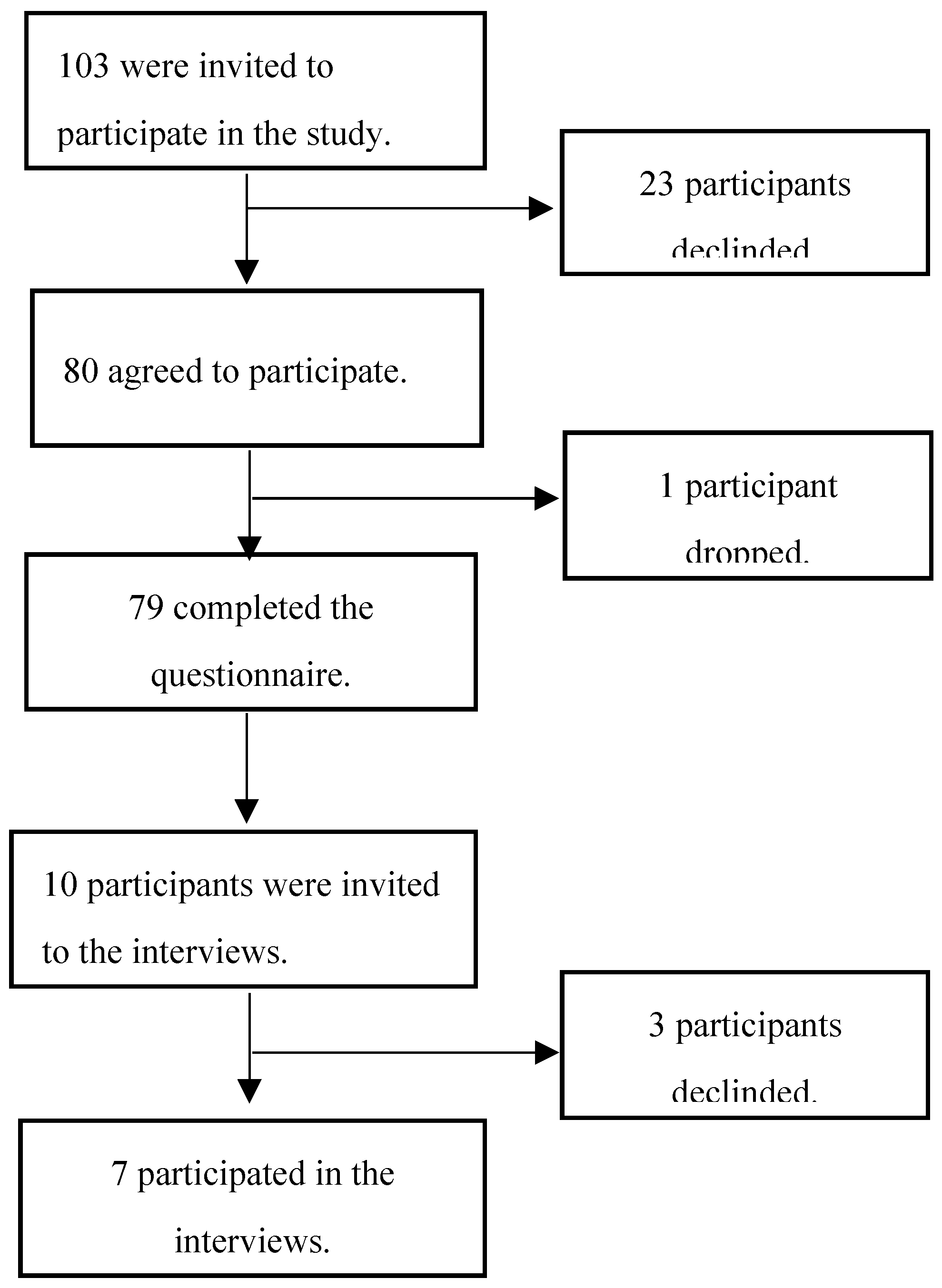

2.2. Study Population and Recruitment

2.3. Adaptation of Tools and Instruments

- ▪

- For the General Attitudes towards Maternal Vaccines, we applied minor changes to the questions for clarity as follows: “Vaccines given during pregnancy are important for my health,” “All recommended vaccines for pregnant women offered by the government program in my community are beneficial,” and “Recommended vaccines for pregnant women are effective.”

- ▪

- For the VAX scale, a five-point Likert scale “Strongly Disagree”, “Disagree”, “Neutral”, “Agree”, “Strongly Agree” was used instead of a six-point Likert scale, “Strongly Disagree”, “Disagree”, “Somewhat disagree”, “Somewhat agree”, “Agree”, “Strongly Agree”.

- ▪

- For the BeSD COVID-19 tool, the “Reasons for low ease of access,” “Service satisfaction,” and “Service quality” constructs were not included, as the focus of the study was on knowledge and attitudes. Most of the questions were adapted for use among pregnant women. For instance, “How concerned are you about getting COVID-19 during pregnancy?”, “Do you want to get a COVID-19 vaccine during pregnancy?”, and “How safe do you think a COVID-19 vaccine is for you as a pregnant woman?” Minor changes to the multiple-choice options were applied to a few questions, such as “Have you ever been contacted about being due for a COVID-19 vaccine?” (answer options: Yes, before pregnancy; Yes, during this pregnancy; No), etc. We also added the following questions: “Has a health worker recommended you get a COVID-19 vaccine before pregnancy?” as participants might have received a health worker recommendation before pregnancy. We added a question about the reason for receiving the COVID-19 vaccine before pregnancy, a question on whether COVID-19 has been discussed with the participant during the current pregnancy, and a question on what will make the participant confident in accepting the COVID-19 vaccine during pregnancy.

- ▪

- We added "Yes or No" questions about trust in COVID-19 and routine childhood vaccines to compare participants' trust in the different vaccines.

- ▪

- For the interview guide, the following BeSD constructs were explored for both COVID-19 and childhood vaccines: “What people feel and think,” “Motivation,” and “Social processes.”

- ▪

-

Questions about the following topics were added to the interview guide:

- ◦

- Questions about the participants’ knowledge and attitudes towards vaccines in general and vaccination during pregnancy.

- ◦

- Questions regarding COVID-19 vaccine decision-making before pregnancy to compare the participants' attitudes before and during pregnancy.

- ◦

- At the time of the study, the National Department of Health in South Africa was planning to switch from Tetanus-reduced diphtheria (Td), which had been administered during antenatal care, to Tetanus, reduced-strength diphtheria, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) starting in January 2024 [25]. Therefore, we also discussed whether they would accept the Tdap vaccine after being informed about it.

2.4. Data Collection Procedures

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Ethics

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics of the Study Population

3.2. Participant Feedback and Usability of Tools

3.3. Findings on General Attitudes Toward Vaccination

“I don't know anything about them. I just know that they protect you from the viruses.” Participant #1.

“ It helps to prevent you from getting sick….Or If you get it, you won't get it so bad…That's all I know.” Participant #6.

“In my religion, we don't believe in vaccines and vitamins…I would take it still because I believe it prevents you from getting sick.” Participant #6.

“I would say yes, because like in some religions would say like, do not take the vaccine then we can always pray about it. Because when you, when you're sick, there's only one person that can heal you. And it's, it's our lord. So, I would say I would consider, their opinion…I've got a pastor. So, he sends me to church. And he would always tell us like, you can go, but it's your own decision. Decision to make. But you must also know that this is stuff that is here to test us. To see if you, if your faith is gonna be strong. So, you can have your vaccine. It's not a problem, but you can also just pray. And ask God, to protect you and your family.” Participant #7.

“Because usually I listen to what the doctor says. Like I'm a hypertension person. If he tells me, you must take your tablets at 7 a.m. I usually do that on time. So, when it comes to my health it's gonna be better for me. My blood pressure will stay normal. Because I take it every day at the same time. So, I would say the doctor's opinion in vaccination.” Participant #1.

“If it's recommended to me by a doctor, then I will take it. But if it's not by a doctor, then I will not”. Participant #3.

“…If they are against it that's their problem. I will still go for it.” Participant #6.

“I would say my family's opinion, yeah, would also make me not take it.” Participant #2.

3.4. Knowledge and Attitudes Toward Maternal Vaccination

“I don't know anything.” Participant #2.

“I don't know much about it; to be honest, I haven't really seen people getting vaccinated during pregnancy. I think there might not be enough information about it. Because I'm six months in now. This is the first time I heard about getting vaccinated while pregnant. Because when you're pregnant, they just tell you, don't do this, don't do that. You can't take this medication; you can't take that. So, you just stay away from everything. So, I don't think there's enough information about it.” Participant #5.

“If it's recommended by the doctor, then I would take it.” Participant #7

“I will get it for the safety of my baby. ” Participant #3

“I will take it because I want to protect the baby.” Participant #4

“I need to know that if I take this COVID vaccine right now, while I'm pregnant, it's going to be safe, I'm not going to be sick, and it's not going to cause a problem in my body.” Participant #4

3.5. Knowledge and Attitudes Toward Routine Childhood Vaccines

“I know that they should get it since the period of being small and that it helps them with their immune system and growing up.” Participant #1

“It's important that the baby must get the vaccine. Because babies must not be getting the illness and get sick and sick.” Participant #4

“Trusted sources of information are my doctor and nurses, that's all.” Participant #6

“Because I want her to be protected.” Participant #2

“Because I want him must get healthy, not getting sick. Getting coughing, I don't want to, I don't want to lose him.” Participant #4

“Definitely. Because that is just my belief. Because I was raised that way, my mother made sure I was up to date. My siblings were up to date with our vaccines. I've already chosen for my son, my first baby, to have all these vaccines.” Participant #5

“I have discussed it with no one. I just decided to do it...When my child was vaccinated, I felt relieved. Really relieved!”. Participant #5

3.6. COVID-19 Vaccination Knowledge and Perceptions

“I was scared of getting COVID because I heard that COVID is dangerous, it's killing people. Yeah. I was very scared. “Participant #4.

“The very first time I was obviously very worried. Because I didn't know much about it. I didn't know what it was like. When we got COVID the first time, it was just off the road, shutdown happened. So, we didn't, there wasn't a lot of information out there. And I was very worried. Because my husband was very, very sick. We also had my son; my son was only a year or two at the time. And then uhm, the second time I got COVID, I had COVID and all these fevers. My son was very sick.” Participant #5.

”Everyone in the house had COVID. Yeah, so and we didn't even know it was COVID. And I went for a COVID test. When the test came back, I was fine you know. But it showed now we had COVID. But other than that, I wasn't scared. I was just relaxed, I didn't panic… Maybe it was self-esteem, because I said to myself, it was just the flu. So, I wasn't scared. Nobody panicked. We were normal in the house. Everyone had it. So, it was normal for us. It was just like the flu.”

“Yeah, it's important, because it makes us safe”. Participant #4.

“I think it's very safe. Like I said, I don't think people would put in the time and the effort. And all that money to then produce a product that is not good and not safe. I don't think the government would do that to the people. And I don't think it would be promoted on such a large scale. If It's a good potential to be harmful.” Participant #5.

“I've heard a lot of stuff; I heard that it gives you the flu. I have heard it from family, friends and like, they were complaining. Those who took the vaccine were complaining about, the pain they got in their arms. I don't know if it is true because I never had it…I heard nothing positive.”

“Because of how ill we were in the beginning. When we got COVID the first time. And then obviously, when the vaccine came out, we did our research. Is it safe? Is it good for us to take the vaccine? And it was then when I got COVID the second time around, it wasn't that bad. I haven't been sick even since it has been a few years now. Since I’ve had the vaccine.”

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Findings and Appraisal

4.2. Strengths and Limitations of This Pilot Study

4.3. Implications for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Healy, C.M.; Rench, M.A.; Montesinos, D.P.; Ng, N.; Swaim, L.S. Knowledge and attitiudes of pregnant women and their providers towards recommendations for immunization during pregnancy. Vaccine 2015, 33, 5445–5451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creanga, A.A.; Johnson, T.F.; Graitcer, S.B.; Hartman, L.K.; Al-Samarrai, T.; Schwarz, A.G.; Chu, S.Y.P.; Sackoff, J.E.; Jamieson, D.J.; Fine, A.D.; et al. Severity of 2009 Pandemic Influenza A (H1N1) Virus Infection in Pregnant Women. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 115, 717–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamieson, D.J.; A Honein, M.; A Rasmussen, S.; Williams, J.L.; Swerdlow, D.L.; Biggerstaff, M.S.; Lindstrom, S.; Louie, J.K.; Christ, C.M.; Bohm, S.R.; et al. H1N1 2009 influenza virus infection during pregnancy in the USA. Lancet 2009, 374, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Alessandro, A.; Napolitano, F.; D'Ambrosio, A.; Angelillo, I.F. Vaccination knowledge and acceptability among pregnant women in Italy. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2018, 14, 1573–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, R.; Bartlett j Fireman, B.; Lewis, E.; Klein, N.P. Effectiveness of Vaccination During Pregnancy to Prevent Infant Pertussis. Pediatrics 2017, 139, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, M.C.; Cutland, C.L.; Jones, S.; Downs, S.; Weinberg, A.; Ortiz, J.R.; Neuzil, K.M.; Simões, E.A.F.; Klugman, K.P.; A Madhi, S. Efficacy of Maternal Influenza Vaccination Against All-Cause Lower Respiratory Tract Infection Hospitalizations in Young Infants: Results From a Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2017, 65, 1066–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoff, T.H.; Blain, A.E.; Watt, J.; Scherzinger, K.; McMahon, M.; Zansky, S.M.; et al. Impact of the US Maternal Tetanus, Diphtheria, and Acellular Pertussis Vaccination Program on Preventing Pertussis in Infants <2 Months of Age: A Case-Control Evaluation. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2017, 65, 1977–1983. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zerbo, O.; Modaressi, S.; Chan, B.; Goddard, K.; Lewis, N.; Bok, K.; Fireman, B.; Klein, N.P.; Baxter, R. No association between influenza vaccination during pregnancy and adverse birth outcomes. Vaccine 2017, 35, 3186–3190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, B.; Jain, P.; Holder, B.S.; Lindsey, B.; Regan, L.; Kampmann, B. What determines uptake of pertussis vaccine in pregnancy? A cross sectional survey in an ethnically diverse population of pregnant women in London. Vaccine 2015, 33, 5822–5828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ditsungnoen, D.; Greenbaum, A.; Praphasiri, P.; Dawood, F.S.; Thompson, M.G.; Yoocharoen, P.; Lindblade, K.A.; Olsen, S.J.; Muangchana, C. Knowledge, attitudes and beliefs related to seasonal influenza vaccine among pregnant women in Thailand. Vaccine 2016, 34, 2141–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDougall, D.M.; Halperin, B.A.; Langley, J.M.; McNeil, S.A.; MacKinnon-Cameron, D.; Li, L.; Halperin, S.A. Knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors of pregnant women approached to participate in a Tdap maternal immunization randomized, controlled trial. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2016, 12, 879–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manjunath, U.; Pareek, R.P. Maternal knowledge and perceptions aboutthe routine immunization programme--a study in a semiurban area in Rajasthan. Indian J. Med. Sci. 2003, 57, 158–163. [Google Scholar]

- Adedire, E.B.; Ajumobi, O.; Bolu, O.; Nguku, P.; Ajayi, I. Maternal knowledge, attitude, and perception about childhood routine immunization program in Atakumosa-west Local Government Area, Osun State, Southwestern Nigeria. Pan. Afr. Med. J. 2021, 40, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Luman, E.T.; McCauley, M.M.M.; Shefer, A.; Chu, S.Y. Maternal Characteristics Associated With Vaccination of Young Children. Pediatrics 2003, 111, 1215–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatiregun, A.A.; Okoro, A.O. Maternal determinants of complete child immunization among children aged 12–23 months in a southern district of Nigeria. Vaccine 2012, 30, 730–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilich, E.; Dada, S.; Francis, M.R.; Tazare, J.; Chico, R.M.; Paterson, P.; Larson, H.J. Factors that influence vaccination decision-making among pregnant women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0234827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larson, H.J.; Jarrett, C.; Schulz, W.S.; Chaudhuri, M.; Zhou, Y.; Dubé, E.; Schuster, M.; MacDonald, N.E.; Wilson, R.; The SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. Measuring vaccine hesitancy: The development of a survey tool. Vaccine 2015, 33, 4165–4175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L.R.; Petrie, K.J. Understanding the Dimensions of Anti-Vaccination Attitudes: the Vaccination Attitudes Examination (VAX) Scale. Ann. Behav. Med. 2017, 51, 652–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health O. Behavioural and social drivers of vaccination: tools and practical guidance for achieving high uptake 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240049680 (accessed on 6 January 2025).

- Hub VD. BEHAVIORAL AND SOCIAL DRIVERS OF VACCINATION (BeSD). Available online: https://demandhub.org/behavioral-and-social-drivers-of-vaccination-besd/ (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Roberts, H.A.; Clark, D.A.; Kalina, C.; Sherman, C.; Brislin, S.; Heitzeg, M.M.; Hicks, B.M. To vax or not to vax: Predictors of anti-vax attitudes and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy prior to widespread vaccine availability. PLOS ONE 2022, 17, e0264019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otieno, N.A.; Nyawanda, B.; Otiato, F.; Adero, M.; Wairimu, W.N.; Atito, R.; Wilson, A.D.; Gonzalez-Casanova, I.; Malik, F.A.; Verani, J.R.; et al. Knowledge and attitudes towards influenza and influenza vaccination among pregnant women in Kenya. Vaccine 2020, 38, 6832–6838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otieno, N.A.; Otiato, F.; Nyawanda, B.; Adero, M.; Wairimu, W.N.; Ouma, D.; Atito, R.; Wilson, A.; Gonzalez-Casanova, I.; Malik, F.A.; et al. Drivers and barriers of vaccine acceptance among pregnant women in Kenya. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2020, 16, 2429–2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Government WC. The Western Cape Language Policy. Available online: https://d7.westerncape.gov.za/general-publication/western-cape-language-policy (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- National Department of Health RoSA. Tetanus, reduced-strength diphtheria and acellular pertussis (Tdap), Knowledge Hub Webinar 2023. Available online: https://knowledgehub.health.gov.za/system/files/2023-11/KH%20webinar%20Session%202%20Tdap%20-%20final.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2024).

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform. 2009, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Minor, B.L.; Elliott, V.; Fernandez, M.; O'Neal, L.; McLeod, L.; Delacqua, G.; Delacqua, F.; Kirby, J.; et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J. Biomed. Inform. 2019, 95, 103208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortelmans, D. Analyzing Qualitative Data Using NVivo. In The Palgrave Handbook of Methods for Media Policy Research; Van den Bulck, H., Puppis, M., Donders, K., Van Audenhove, L., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019; pp. 435–450. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen, J.W.C. (Ed.) Fault lines: a primer on race, science and society; African Sun Media: Stellenbosch, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rikard-Bell, M.; Elhindi, J.; Lam, J.; Seeho, S.; Black, K.; Melov, S.; Jenkins, G.; McNab, J.; Wiley, K.; Pasupathy, D. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among pregnant women and the reasons for hesitancy: A multi-centre cross-sectional survey. Aust. New Zealand J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2022, 63, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiersnowska, I.; Kalita-Kurzyńska, K.; Piekutowska-Kowal, W.; Baranowska, J.; Krzych-Fałta, E. Attitudes towards Maternal Immunisation of Polish Mothers: A Cross-Sectional, Non-Representative Study. Vaccines 2024, 12, 1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, A.; Mullin, S.; Chapman, S.; Barnard, K.; Bakhbakhi, D.; Ion, R.; Neuberger, F.; Standing, J.; Merriel, A.; Fraser, A.; et al. Interventions to enhance medication adherence in pregnancy- a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2023, 23, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manyazewal, T.; Woldeamanuel, Y.; Blumberg, H.M.; Fekadu, A.; Marconi, V.C. The potential use of digital health technologies in the African context: a systematic review of evidence from Ethiopia. npj Digit. Med. 2021, 4, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Lee, Y.-J.; Kim, S.; Choi, W.; Jeong, Y.; Rhim, N.J.; et al. Perceptions on Data Quality, Use, and Management Following the Adoption of Tablet-Based Electronic Health Records: Results from a Pre–Post Survey with District Health Officers in Ghana. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare 2022, 15, 1457–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, S.Y.J.; Acharya, A.; Basnet, O.; Haaland, S.H.; Gurung, R.; Gomo, Ø.; Ahlsson, F.; Meinich-Bache, Ø.; Axelin, A.; Basula, Y.N.; et al. Mothers’ acceptability of using novel technology with video and audio recording during newborn resuscitation: A cross-sectional survey. PLOS Digit. Heal. 2024, 3, e0000471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Health SA. NATIONAL INTEGRATED MATERNAL AND PERINATAL CARE GUIDELINES FOR SOUTH AFRICA 2024. Fifth edition. Available online: https://knowledgehub.health.gov.za/system/files/elibdownloads/2024-10/Integrated%20Maternal%20and%20Perinatal%20Care%20Guideline_23_10_2024_0.pdf (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- Ashkir, S.; Khaliq, O.P.; Hunter, M.; Moodley, J. Maternal vaccination: A narrative review. South. Afr. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 37, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The National Institute for Communicable Diseases (NICD) SA. Vaccination of pregnant and breastfeeding women (August update) 2021. Available online: https://www.nicd.ac.za/vaccination-of-pregnant-and-breastfeeding-women-august-update/ (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- Wei, C.R.; Kamande, S.; Lang’at, G.C. Vaccine inequity: a threat to Africa’s recovery from COVID-19. Trop. Med. Heal. 2023, 51, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, B.; Olivier, J.; Amponsah-Dacosta, E. Health Systems Determinants of Delivery and Uptake of Maternal Vaccines in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Qualitative Systematic Review. Vaccines 2023, 11, 869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 31 ± 6 | - |

| Gestational age (weeks) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 15 ± 8 | - |

| Pregnancy risk status | ||

| High risk | 47 | 62 |

| Low risk | 29 | 38 |

| Race* | ||

| Black African | 47 | 59.4 |

| Colored | 29 | 36.7 |

| White | 1 | 1.3 |

| Indian | 1 | 1.3 |

| Asian | 1 | 1.3 |

| Educational level | ||

| Primary | 2 | 2.5 |

| Secondary | 52 | 65.8 |

| Post-secondary certificate | 6 | 7.6 |

| Tertiary | 19 | 24.1 |

| Employment | ||

| Employed | 55 | 70 |

| Unemployed | 24 | 30 |

| Household income | ||

| Low | 76 | 96 |

| Middle | 3 | 4 |

| HIV status | ||

| HIV positive | 11 | 13.9 |

| HIV negative | 68 | 86.1 |

| No | Statement | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly Agree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | I feel safe after being vaccinated. | 13 (17.1%) | 5 (6.7%) | 18 (23.7%) | 20 (26.7%) | 22 (29.0%) |

| 2 | I can rely on vaccines to stop serious infectious diseases. | 8 (10.5%) | 7 (9.2%) | 12 (15.8%) | 24 (31.6%) | 25 (32.9%) |

| 3 | I feel protected after getting vaccinated. | 7 (9.3%) | 5 (6.7%) | 16 (21.3%) | 27 (36.0%) | 20 (26.7%) |

| 4 | Although most vaccines appear to be safe, there may be problems that we haven't yet discovered. | 14 (18.4%) | 3 (4.0%) | 14 (18.4%) | 19 (25.0%) | 26 (34.2%) |

| 5 | Vaccines can cause unforeseen problems in children. | 14 (18.4%) | 8 (10.5%) | 19 (25%) | 24 (31.6%) | 11 (14.5%) |

| 6 | I worry about the unknown effects of vaccines in the future. | 7 (9.2%) | 7 (9.2%) | 12 (15.8%) | 24 (31.6%) | 26 (34.2%) |

| 7 | Vaccines make a lot of money for pharmaceutical companies but don't do much for regular people. | 15 (19.7%) | 10 (13.2%) | 24 (31.6%) | 14 (18.4%) | 13 (17.1%) |

| 8 | Authorities promote vaccination for financial gain, not for people's health. | 21 (27.6%) | 12 (15.8%) | 22 (29.0%) | 11 (14.5%) | 10 (13.2%) |

| 9 | Vaccination programs are a big scam. | 23 (30.3%) | 11 (14.5%) | 21 (27.6%) | 15 (19.7%) | 6 (7.9%) |

| 10 | Natural immunity lasts longer than a vaccination. | 11 (14.5%) | 10 (13.2%) | 29 (38.2%) | 15 (19.7%) | 11 (14.5%) |

| 11 | Natural exposure to viruses and germs gives the safest protection. | 12 (15.8%) | 11 (14.5%) | 29 (38.2%) | 14 (18.4%) | 10 (13.2%) |

| 12 | Being exposed to diseases naturally is safer for the immune system than being exposed through vaccination. | 13 (17.1%) | 11 (11.8%) | 31 (40.8%) | 13 (17.1%) | 10 (13.2%) |

| No | Statement | Agree | Neutral/ No opinion | Disagree |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Vaccines given in pregnancy are important for my health. | 37 (49.3%) | 26 (34.6%) | 12 (16.0%) |

| 2 | All recommended vaccines for pregnant women offered by the government program in my community are beneficial. | 38 (50.7%) | 25 (33.3%) | 12 (16.0%) |

| 3 | Recommended vaccines for pregnant women are effective. | 40 (53.3%) | 27 (36.0%) | 8 (10.7%) |

| 4 | New vaccines carry more risks than older vaccines. | 11 (14.7%) | 44 (58.7%) | 20 (26.7%) |

| 5 | Getting vaccines is a good way to protect myself from disease. | 51 (68.0%) | 15 (20.0%) | 9 (12.0%) |

| 6 | I am concerned about serious adverse effects of vaccines. | 46 (61.3%) | 18 (24.0%) | 11 (14.7%) |

| 7 | I do not need vaccines for diseases that are not common anymore. | 22 (29.3%) | 32 (42.7%) | 21 (28.0%) |

| Statement | Response options | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

|

- How important do you think getting a COVID-19 vaccine during pregnancy is for your health? |

|||

| Not at all important | 27 | 34.2 | |

| A little important | 16 | 20.3 | |

| Moderately important | 16 | 20.3 | |

| Very important | 20 | 25.3 | |

|

- Do you want to get a COVID-19 vaccine during pregnancy? |

|||

| No, you do not want to | 54 | 68.4 | |

| Yes you want to | 1 | 1.3 | |

| You are not sure | 3 | 11.4 | |

| No, I don't want to because I am already vaccinated | 15 | 19.0 | |

|

- Do you think most of your close family and friends want you to get a COVID-19 vaccine while you are pregnant? |

|||

| Yes | 18 | 22.8 | |

| No | 61 | 77.2 | |

| - Do you know where to go to get a COVID-19 vaccine for yourself? | |||

| Yes | 59 | 74.7 | |

| No | 20 | 25.3 | |

| - How easy is it to pay for COVID-19 vaccination? When you think about the cost, please consider any payments to the clinic, the cost of getting there and the cost of taking time away from work? | |||

| Not at all easy | 9 | 11.4 | |

| A little easy | 18 | 22.8 | |

| Moderately easy | 13 | 16.5 | |

| Very easy |

39 | 49.4 | |

| - How important do you think routine childhood vaccines (immunization) are for your child's health? | |||

| Not at all important | 7 | 8.9 | |

| A little important | 7 | 8.9 | |

| Moderately important | 7 | 8.9 | |

| Very important | 58 | 73.4 | |

| - Do you think most of your close family and friends want you to get your child vaccinated? | |||

| Yes | 56 | 70.9 | |

| No | 23 | 29.1 | |

| - South Africa has an immunization schedule of recommended vaccines for children. Do you want your child to get none of these vaccines (immunization), some of these vaccines (immunization), or all of these vaccines (immunization)? | |||

| None | 7 | 8.9 | |

| Some | 25 | 31.7 | |

| All | 47 | 59.5 | |

|

- Do you know where to go to get your child vaccinated? |

|||

| Yes | 67 | 84.8 | |

| No |

12 | 15.2 | |

|

- How easy is it to pay for your child vaccination? When you think about the cost, please consider any payments to the clinic, the cost of getting there, plus the cost of taking time away from work? (Think of any related cost even if the vaccines will be given for free at the clinic that you will go to get your child vaccinated) |

|||

| Not at all easy | 15 | 19.0 | |

| A little easy | 24 | 30.4 | |

| Moderately easy | 16 | 20.2 | |

| Very easy | 24 | 30.4 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).