1. Introduction

Human papillomavirus (HPV) encompasses a group of over 200 related viruses known to infect the genital areas, mouth, and throat of both men and women [

1]. As a common sexually transmitted infection globally, HPV poses a significant health risk, being the primary cause of cervical cancer. Notably, HPV types 16 and 18 are implicated in around 70% of all cervical cancer cases worldwide [

2,

3]. The prevalence of HPV is so widespread that an estimated 80% of sexually active individuals will have been infected with at least one type of HPV by the age of 45 [

3]. This high prevalence underscores the importance of early detection, regular screening, and preventive measures, notably vaccination, to mitigate the associated health risks [

4,

5].

The global fight against HPV has been bolstered by the development and dissemination of three primary HPV vaccines: the bivalent, quadrivalent, and nonavalent vaccines. These vaccines have demonstrated high safety, immunogenicity, and efficacy against the most oncogenic HPV types, especially types 16 and 18 [

2]. The broad impact of these vaccines is seen in their ability to prevent specific HPV-related infections and conditions, as evidenced in the decreased rates of oral HPV infections among vaccinated young adults [

6]. The administration of these vaccines typically occurs in a series of doses, with the recommended age for vaccination varying by country. The World Health Organization (WHO) advocates for achieving high vaccination coverage with at least one dose of an HPV vaccine among girls aged 9 to 14 years, before they become sexually active, thereby indirectly reducing HPV infection rates in boys as well [

2].

In South Africa, cervical cancer ranks as a leading cause of cancer-related deaths among women, with the country experiencing a high number of new cases annually [

7]. In response, South Africa launched a school-based HPV vaccination programme in 2014, targeting girls in grade four aged nine years or older, with the bivalent vaccine [

8]. Since a substantial proportion of girls in grade four are below nine years of age, the target population for HPV vaccination in South Africa was later changed to grade five girls aged nine years or older [

9]. While the programme has achieved significant vaccination coverage of more than 80% nationally, wide variations exist within and between subnational geographies, with some areas like the eThekwini District in the province of KwaZulu-Natal reporting vaccination coverage as low as 40% [

8,

9]. Research indicates that factors such as limited awareness, safety concerns, cultural beliefs, challenges with healthcare access, and social stigma around sexual health discussions contribute to these disparities in vaccine uptake [8-10]. Understanding these barriers and facilitators is crucial for designing targeted interventions to enhance vaccine uptake and, ultimately, reduce the burden of HPV-related diseases in South Africa. We therefore conducted this cross-sectional study to assess the behavioural and social factors that influence HPV vaccination decisions within eThekwini District of KwaZulu-Natal Province in South Africa [

10].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

This is a cross-section study conducted from 15 April 2023 to 15 May 2023 among parents and other persons fulfilling parental roles (henceforth referred to as caregivers) in four neighbourhoods of eThekwini District namely, Chatsworth, Embo, Umlazi, and Wentworth.

We employed a stratified random sampling technique because of its effectiveness in achieving representativeness in diverse populations [

11]. The district was segmented into various strata based on socio-demographical factors, including income levels, educational backgrounds, ethnic group, and urban versus rural residency. This approach is in line with Newman and Gough's advocacy for capturing a wide range of perspectives in educational and social research [

12]. Each stratum was proportionally represented in the sample, in accordance with the district's demographical distribution, to ensure a comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing HPV vaccine uptake.

Caregivers were selected from varied healthcare access points, including schools, public clinics, private practices, and community health centers. Furthermore, the sample included caregivers with different employment statuses and levels of community engagement, for a nuanced understanding of community-level influences on health behaviours. Participant recruitment was conducted in collaboration with local healthcare facilities, schools, and community organizations.

2.2. Sample Size

The planned sample size for the survey, targeting caregivers of children aged 9 to 14 years, was set at 713 participants. The sample size was determined to provide sufficient statistical power to adequately assess factors associated with the uptake of HPV vaccination in this district, ensuring sufficient statistical power [

13]. This sample size offers 80% statistical power to detect small correlation effects (r=0.2) with a significance level of 5% [13, 14], thereby enabling the identification of even subtle associations within the data.

2.3. Data Management and Analyses

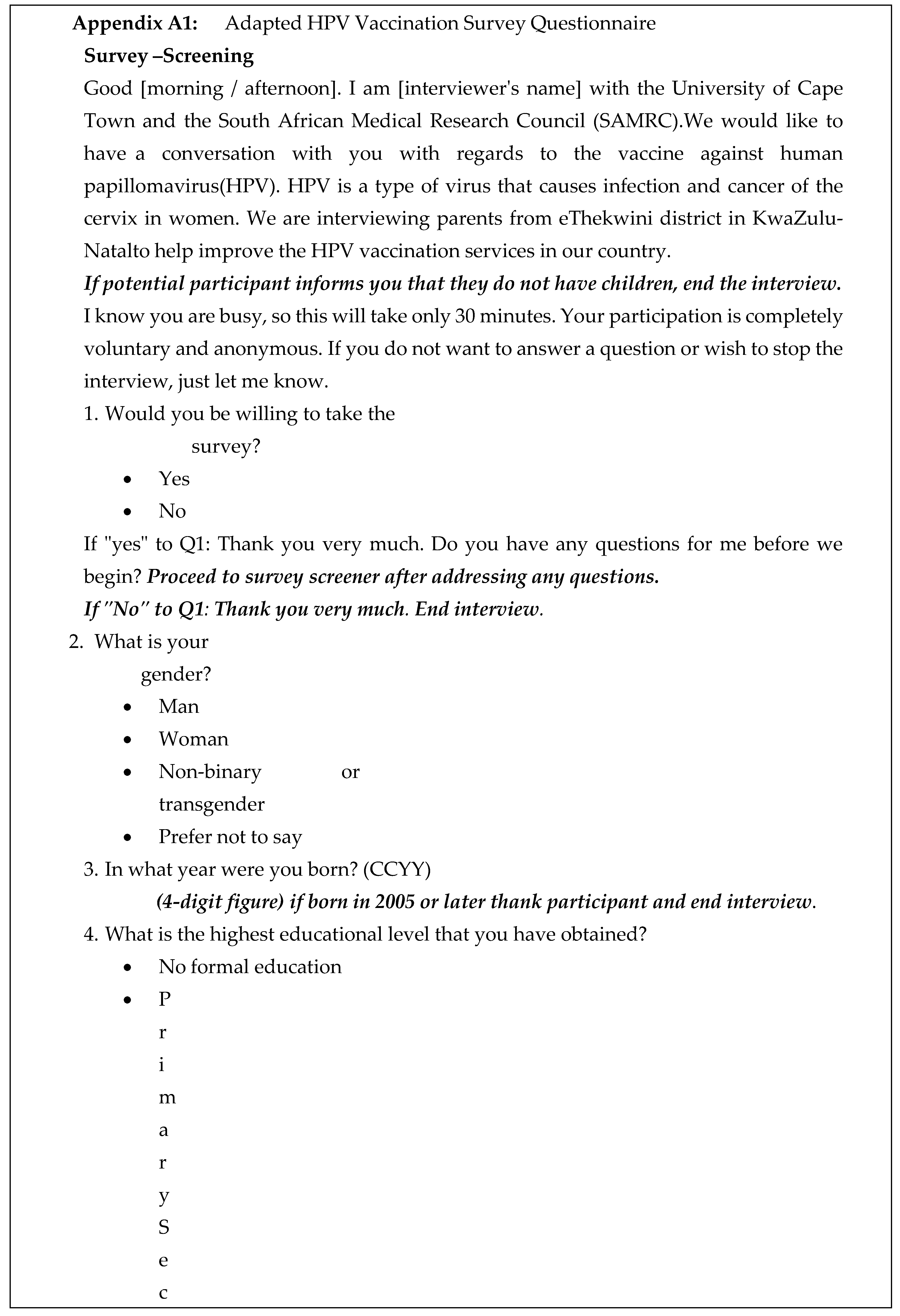

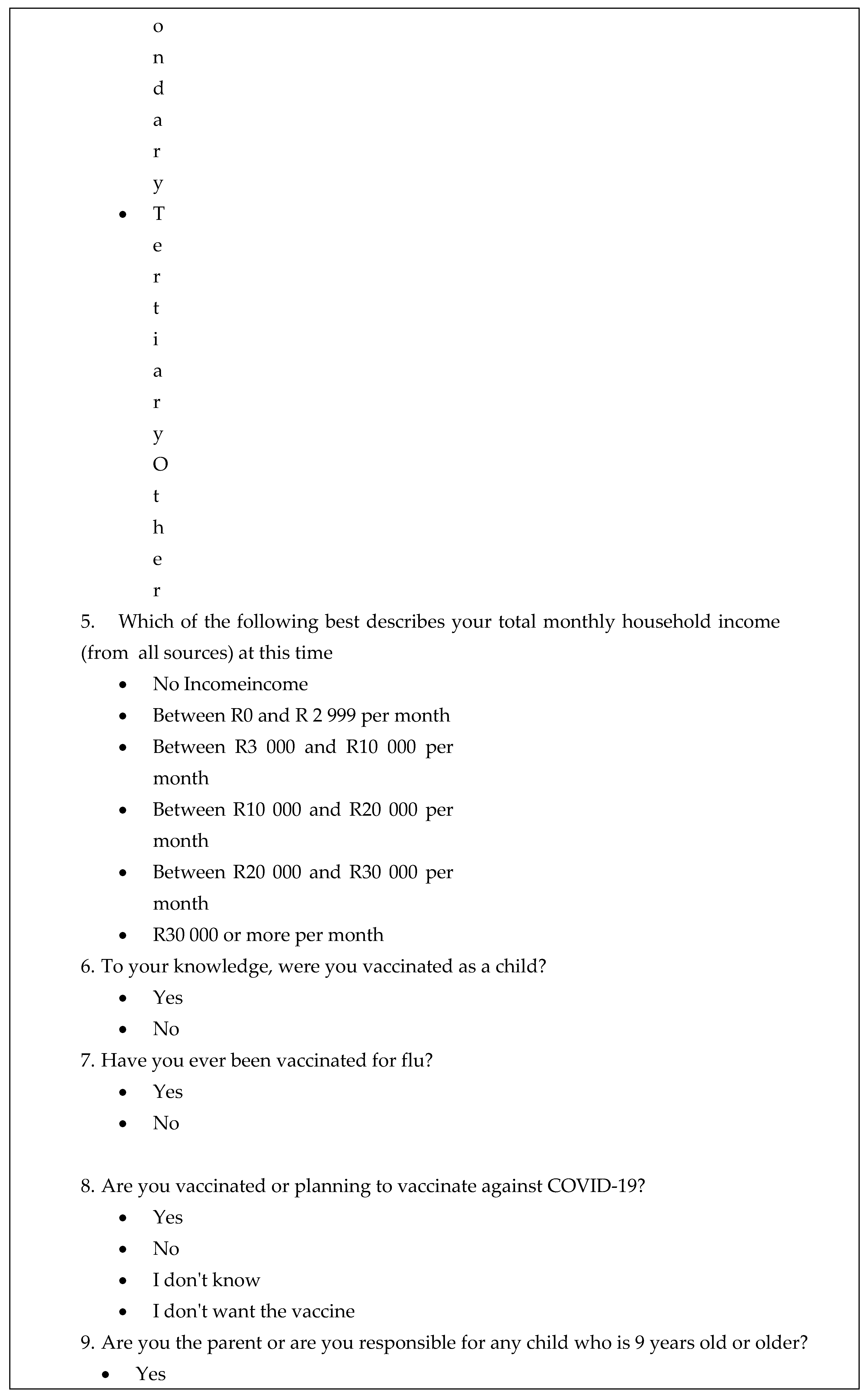

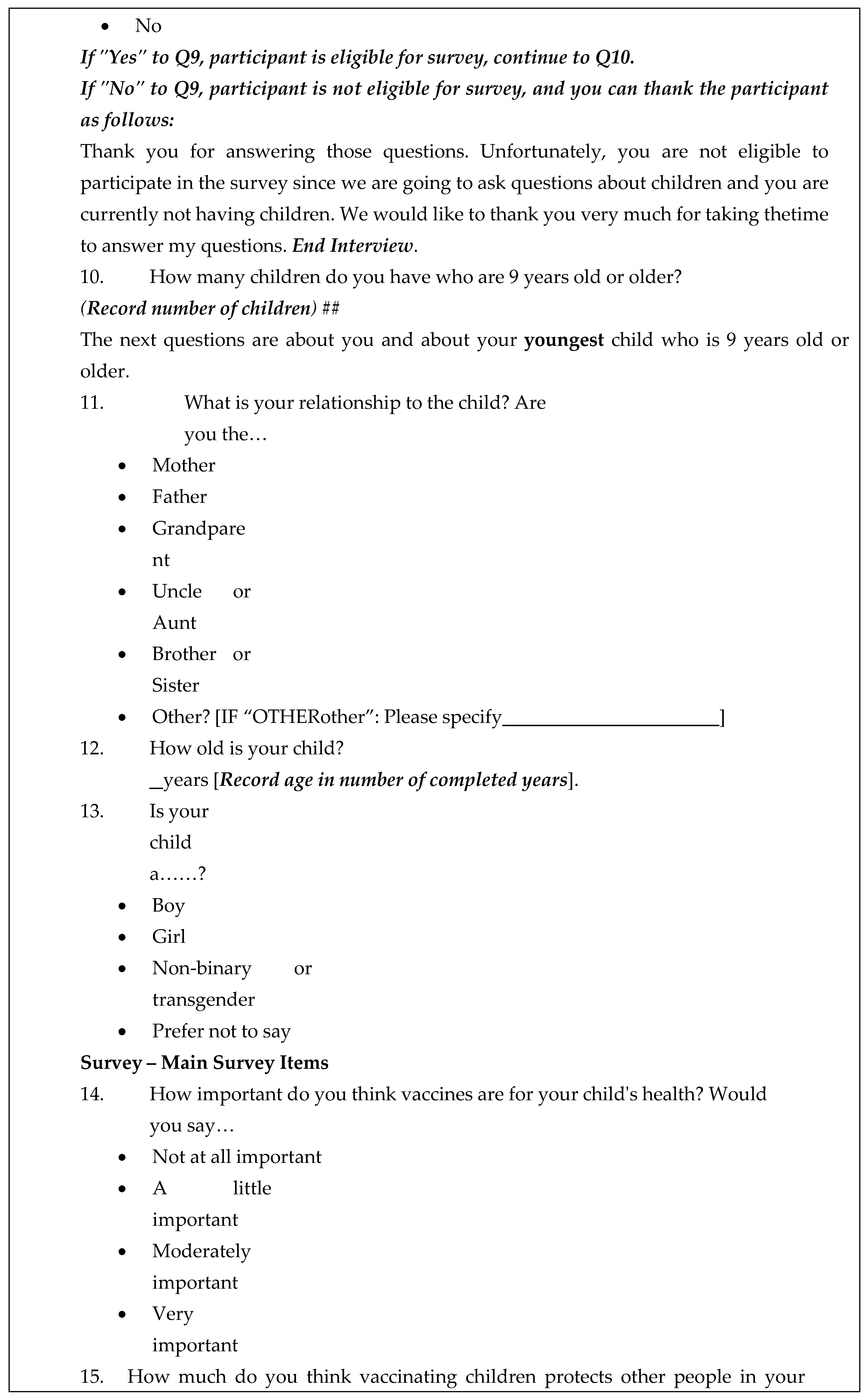

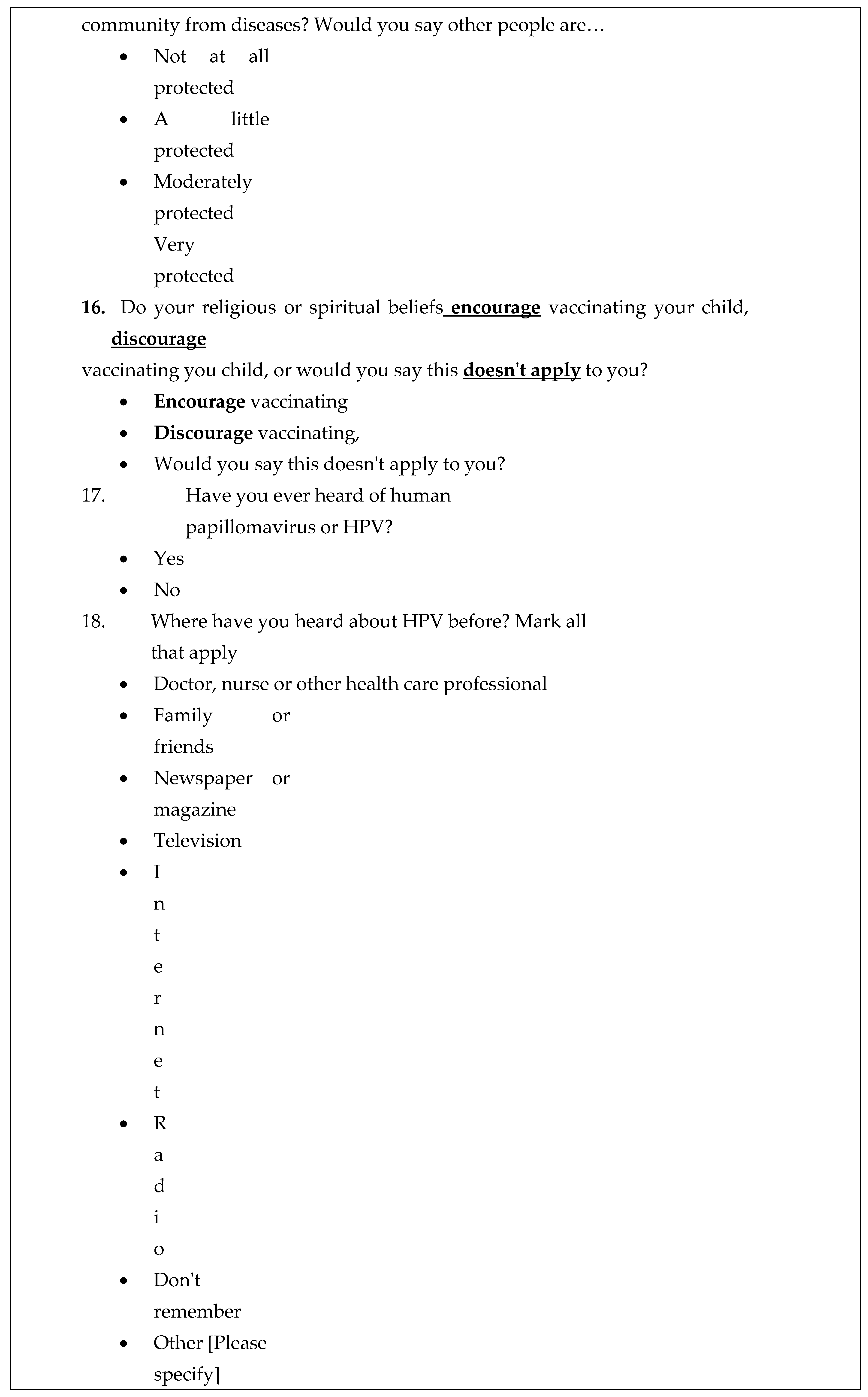

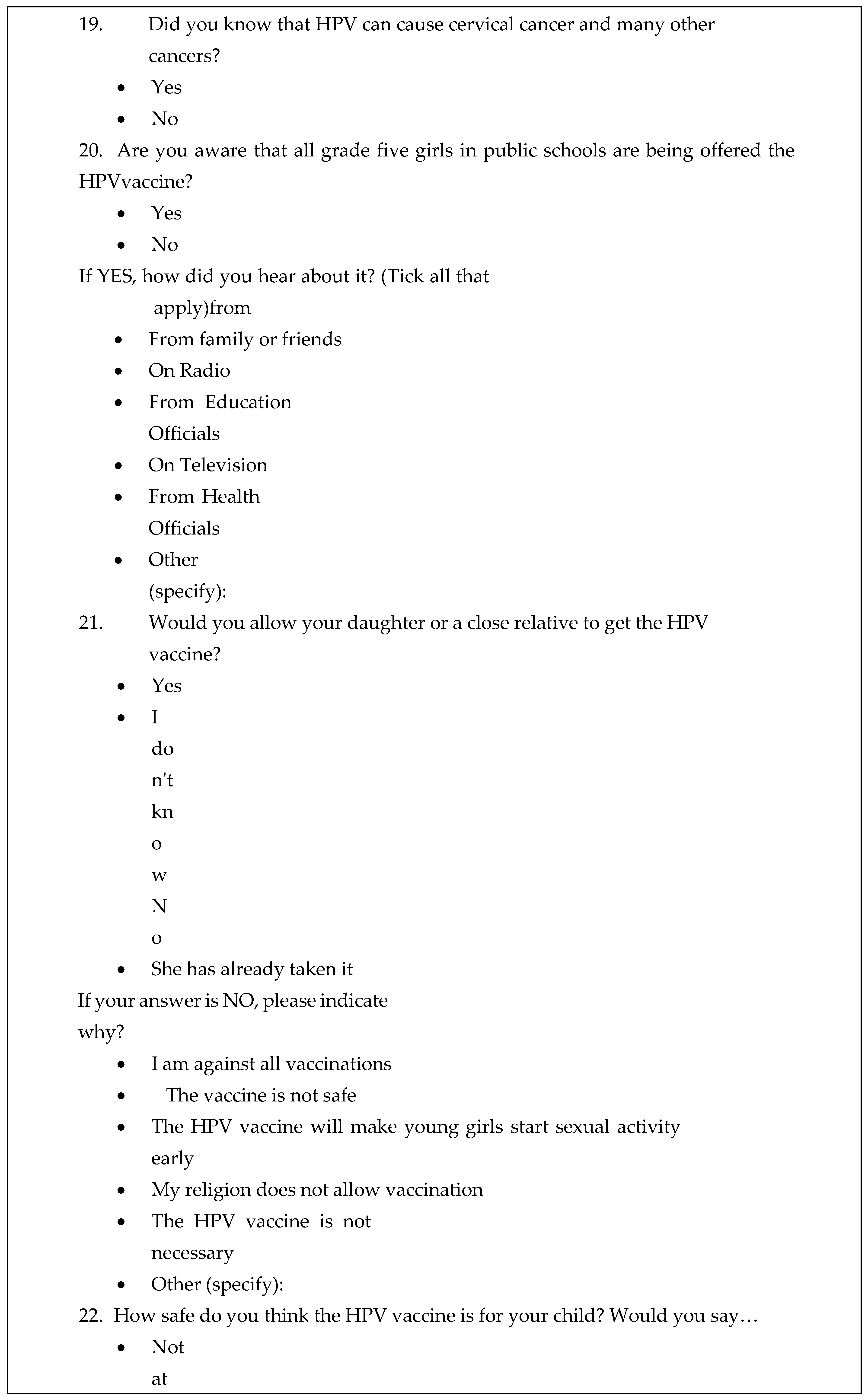

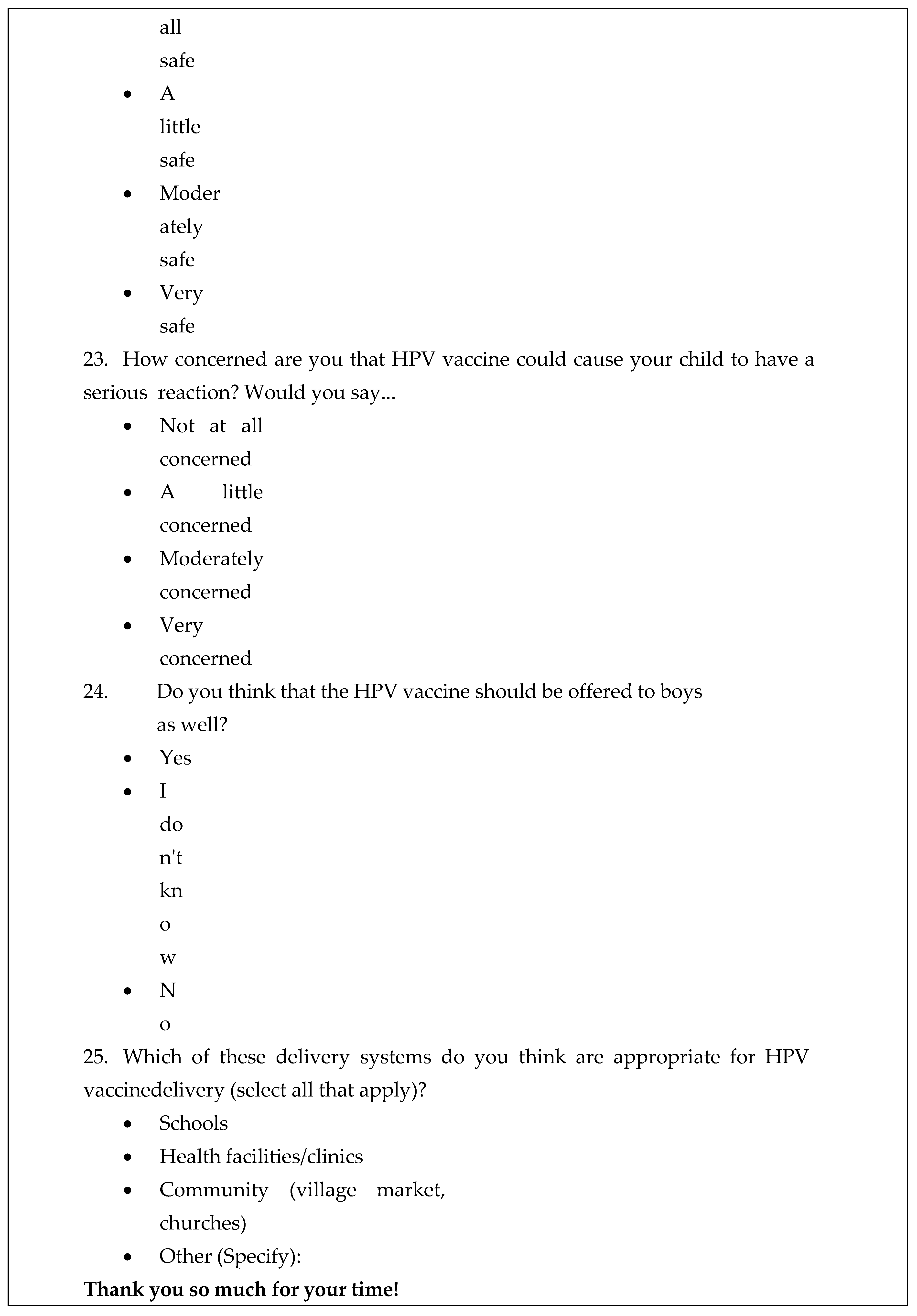

Trained research assistants explained the importance and procedures of the study to eligible individuals, and those who consented to participate in the study signed both the study consent form and information leaflet. A structured questionnaire was then administered to consenting participants by the trained research assistants to collect the required data. We adapted the questionnaire from the WHO framework for behavioural and social drivers of vaccination (BeSD) [

15]. We have previously adapted the BeSD questionnaire, which was initially developed for childhood vaccination, to study COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in South Africa [

16]. The BeSD framework is designed to explore and measure multiple behavioural and social factors that influence vaccination decisions. It encompasses a range of elements including individual beliefs, trust, social norms, motivation, and structural barriers to vaccine uptake. By assessing these factors, the BeSD model aids public health professionals and researchers in identifying key drivers and barriers to vaccine uptake, thereby facilitating the development of more effective and tailored public health strategies for enhancing vaccine confidence and uptake.

To ensure the clarity and relevance of the questionnaire, we conducted pilot testing through cognitive interviews. This involved two rounds of interviews in one neighbourhood, each involving four to eight participants. The aim of this pilot testing was to ensure that participants could easily understand the questions and that their responses accurately reflected the intended constructs. This step was crucial to confirm that all survey items, including the questions and their respective response options, were not only correctly translated but also conveyed the intended meanings in the context of HPV vaccination. The adapted questionnaire (

Appendix A1) has questions on socio-demographical characteristics; knowledge of HPV, the relationship between HPV and cervical cancer, and the national HPV vaccination programme and its target population; willingness to allow daughters or close relatives to receive the HPV vaccine; and safety of the HPV vaccine.

We tested for associations between variables using the chi-squared test (for binary data) and student’s t-test (for continuous data). We then used the modified Poisson regression (that is, Poisson regression with log link and robust sandwich standard error) to assess the association between exploratory factors and HPV vaccine acceptance [

17]. We examined the correlation matrix, which showed that while some predictors were correlated, they did not significantly impact the model’s interpretability. Therefore, we determined that multicollinearity was not a significant concern in our analyses, and no variables were removed. We believe that these steps ensured the robustness of our multivariable model. We processed datasets using Microsoft Excel and conducted analyses using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (IBM SSPS Inc, Chicago, IL) V.27.0 and R (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) V4.0.5 software.

2.4. Ethics Approval

We obtained ethics approval from the University of Cape Town’s Human Research Ethics Committee (Reference: HREC 286/2021) and administrative clearance from the KwaZulu-Natal Provincial Department of Health.

3. Results

We invited 793 eligible participants and 713 (89.9%) accepted the invitation, consented, and participated in the study. The characteristics of the study population are shown in

Table 1. The mean age (± standard deviation) of the study population was 42.6 (± 11.6) years and there were 614 (86.1%) female participants. Most of the participants had secondary or lower education (83.7%) and household income less than 10,000 South African Rand (92.0%).

Among the participants, 70.9% (504/710) had heard of HPV and 59.7% (425/712) knew that HPV causes cervical cancer. A higher proportion of 86.0% (602/700) were aware of the school-based HPV vaccination programme that targets girls in grade five in public schools. In addition, 93.7% (664/709) were confident that the HPV vaccine was safe for girls and 77.0% (545/708) said the vaccine should also be offered to boys. Overall, 93.5% (667/713) of study participants accept HPV vaccination of their girls. This group includes 42.9% of study participants who had already vaccinated their daughters and 50.6% of participants who expressed willingness to allow their daughters or close relatives to receive the HPV vaccine. A negligible proportion was either undecided (2.1%) or unwilling to allow their daughters or next of kins to take the HPV vaccine (4.4%). Denominators differ slightly due to a small number of missing data.

Univariate analyses revealed the following exploratory variables to be associated with acceptance of HPV vaccination: knowledge of HPV (crude prevalence ratio [cPR] = 1.06; 95% confidence intervals [CI] = 1.01 to 1.11); awareness of the existence of the national school-based HPV vaccination programme (cPR 1.23; 95% CI 1.10 to 1.36); belief that HPV vaccination is important (cPR 1.12; 95% CI 1.03 to 1.23); confidence in the safety of HPV vaccines (cPR 1.17; 95% CI 1.12 to 1.24); and recommendation from religious leaders encouraging HPV vaccination (cPR 1.45]; 95% CI 1.05 to 2.00). As shown in

Table 2, there was no distinct association between acceptance of HPV vaccination and any of the following variables: age, gender, level of formal education, household income, and vaccination against COVID-19.

Finally, in the multivariable analyses, controlling for awareness of the existence of the school-based HPV vaccination programme, confidence in the importance of HPV vaccines, confidence in the safety of HPV vaccines, and recommendation by religious leaders, two factors emerged as independent predictors of HPV vaccine acceptance in eThekwini District. These are knowledge of the school-based HPV vaccination programme (adjusted prevalence ratio [aPR] 1.16; 95% CI 1.06 to 1.28) and confidence in the safety of HPV vaccines (aPR 1.14; 95% CI 1.08 to 1.19). In addition, recommendation from religious leaders in favour of HPV vaccination was a marginally significant independent predictor of HPV vaccine acceptance (aPR 1.30; 95% CI 0.98 to 1.72).

4. Discussion

Cervical has a significant health and social impact on South African society, ranking among the top causes of cancer-related deaths among women [

7]. One of the main tools to fight the scourge of cervical cancer is HPV vaccination of girls before they become sexually active, introduced in South Africa in 2014; but wide variations exist within and between subnational geographies in HPV vaccination coverage, with some areas like the eThekwini District having coverage as low as 40% [

8,

9]. However, in this cross-sectional study, we found very high HPV vaccine acceptance of 93.5% in eThekwini District. This acceptance is influenced by what caregivers think and feel (including knowledge of the HPV vaccination programme and confidence in vaccine safety) and, to a certain extent, social norms (including recommendations by religious leaders). Our finding of high acceptance of HPV vaccination among caregivers of young girls is a powerful positive message that can form the basis of a comprehensive vaccine communication and education strategy in South Africa. The high levels of knowledge and acceptance of HPV vaccination found in this study can be compared with findings from other studies in South Africa [

18] and in other low and middle-income countries [

19].

Vaccine literacy and vaccine confidence are crucial factors which influence vaccine acceptance and uptake. Vaccine literacy plays an important role in shaping public perceptions and influencing behaviour regarding vaccination. In a previous study in Israel, Gendler and Ofri found that parents with higher levels of vaccine literacy showed more positive vaccine perceptions and were more likely to accept vaccination for their children [

20]. These findings are supported by a systematic review by Mavundza and colleagues of the factors that influence caregivers' views and practices regarding vaccines in Africa. The review found that caregivers' views and practices regarding vaccination in Africa are influenced by various factors including lack of information or knowledge about vaccines [

21]. There is therefore need for providing reliable and accessible information about vaccines to enhance understanding and acceptance. However, several studies highlight persisting gaps in awareness and understanding of HPV vaccination among different population groups in South Africa [

8,

9,

22]. In particular, a study by Tathiah and colleagues targeting the South African private health sector found that low awareness levels about HPV and its vaccines remain a significant barrier to achieving high vaccine coverage and reducing the burden of HPV-related illnesses [

22]. These studies collectively suggest that while there are ongoing efforts to improve HPV vaccination coverage in countries like South Africa, low level awareness about HPV and its vaccines remains a fundamental barrier. There is thus a need to address this gap through public education in the form of targeted vaccine literacy campaigns to provide information about vaccines, including HPV vaccines, where it is presently lacking. Education campaigns, public health communication, and messaging should also provide information regarding where girls can access HPV vaccination services and address any concerns about the vaccine.

We found that vaccine confidence, which encompasses trust in the safety and efficacy of vaccines, is a major determinant of vaccine acceptance. A literature review focusing on COVID-19 vaccination in Eastern European countries also identified public confidence in vaccine safety and efficacy as a central attitude associated with vaccine acceptance [

23]. The study emphasized that improving public confidence through transparent communication about vaccine development and safety profiles is essential to increase vaccine uptake. The perception of vaccine safety as a critical factor in willingness to vaccinate is a common finding in vaccination literature worldwide [

24]. Addressing safety concerns is central to vaccine acceptance. Systematic reviews of HPV vaccine acceptance research conducted in Africa provide evidence to support this view, which places significant emphasis on the importance of addressing safety concerns to improve vaccine uptake [

25]. It is therefore important to have a comprehensive vaccine communication strategy that disseminates timely, accurate, and transparent information about HPV vaccines to address any apprehensions about the vaccine and ensure vaccine confidence and uptake.

This study revealed high willingness to get vaccinated against HPV in eThekwini District, but actual HPV vaccine uptake in the district is still low [

8,

9]. Willingness and good knowledge alone do not always translate to high vaccine uptake [26, 27]. Beyond motivation to get vaccinated, factors such as vaccine availability also drive actual vaccine uptake [

27]. Caregiver’s vaccination attitudes and behaviours consist of an ongoing engagement that is contingent on unfolding personal and social circumstances, which can potentially change over time [

26]. Therefore, communication on HPV vaccination should involve more than information and factor in that people develop their beliefs through their life experiences and that culture, personal background, and religion all shape people’s reactions to facts presented to them. The study identifies religious leaders as key influencers within communities. Integrated faith-based perspectives with public health objectives could present a considerable opportunity for synergistic action in favour of vaccination programmes. In addition, communication strategies should resonate with various cultural sentiments within communities. The intersection of health care, education, and religion presents a tapestry of channels through which vaccine literacy can be effectively amplified.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: PB, CSW; methodology: PB, CSW, MS; formal analysis: PB and PK; investigation: SB, AVM, TS, MS, DS, LGT; resources: CSW and DN; writing—original draft preparation: PB, CSW, PDMCK; writing—review and editing: PB, CSW, PDMCK, DN, SC, SB, AVM, TS, MS, DS, LGT, PK, MS; supervision: CSW, DN, and MS; project administration: PB. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the South African Medical Research Council (SAMRC), through Cochrane South Africa (Project 43500). PB received a training fellowship from the SAMRC through its Division of Research Capacity Development (under the Bongani Mayosi National Health Scholars Programme funded by the South African National Department of Health).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Cape Town Faculty of Health Sciences Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC Reference: 286/2021). We also obtained permission to carry out the study from the KwaZulu-Natal Provincial Department of Health of Health and Department of Education. All research procedures were conducted according to Helsinki declaration.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data generated in this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support received from the South African Medical Research Council. The authors are also grateful to the caregivers who participated in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results. The content of this manuscript is the sole responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the South African Medical Research Council or any institutions to which the authors are directly or indirectly affiliated.

References

- Bruni L, Saura-Lázaro A, Montoliu A, Brotons M, Alemany L, Diallo MS, Afsar OZ, LaMontagne DS, Mosina L, Contreras M, Velandia-González M, Pastore R, Gacic-Dobo M, Bloem P. HPV vaccination introduction worldwide and WHO and UNICEF estimates of national HPV immunization coverage 2010-2019. Prev Med 2021; 144:106399.

- World Health Organization. Human papillomavirus vaccines: WHO position paper (2022 update). Weekly Epidemiological Record 2022;97:645-672.

- Chesson HW, Dunne EF, Hariri S, Markowitz LE. The estimated lifetime probability of acquiring human papillomavirus in the United States. Sexually Transmitted Diseases 2014;41(11):660-4.

- Adamu AA, Jalo RI, Ndwandwe D, Wiysonge CS. Exploring the complexity of the implementation determinants of human papillomavirus vaccination in Africa through a systems thinking lens: a rapid review. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics 2024;20(1):2381922.

- Mavundza EJ, Mmotsa TM, Ndwandwe D. Human papillomavirus (HPV) trials: a cross-sectional analysis of clinical trials registries. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics 2024;20(1):2393481.

- Chaturvedi AK, Graubard BI, Broutian T, Pickard RK, Tong ZY, Xiao W, Kahle L, Gillison ML. Effect of prophylactic human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination on oral HPV infections among young adults in the United States. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2018;36(3):262-7.

- Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 2018;68(6):394-424.

- Ngcobo NJ, Burnett RJ, Cooper S, Wiysonge CS. Human papillomavirus vaccination acceptance and hesitancy in South Africa: research and policy agenda. S Afr Med J 2018;109(1):13-15.

- Amponsah-Dacosta E, Blose N, Nkwinika VV, Chepkurui V. Human papillomavirus vaccination in South Africa: programmatic challenges and opportunities for integration with other adolescent health services?. Frontiers in Public Health 2022;10:799984.

- Bhengu P, Ndwandwe D, Cooper S, Katoto PDMC, Wiysonge CS, Shey M. Behavioural and social drivers of human papillomavirus vaccination in eThekwini District of KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa. PLoS One 2024;19(12):e0311509.

- Iliyasu R, Etikan I. Comparison of quota sampling and stratified random sampling. Biom Biostat. Int J Rev 2021;10(1):24-27.

- Newman M, Gough D. Systematic reviews in educational research: Methodology, perspectives and application. Systematic reviews in educational research: Methodology, perspectives and application 2020:3-22.

- Kumar, R. Research methodology: A step-by-step guide for beginners. SAGE Publications Limited, 2019.

- Pett, M. , Lackey, N. & Sullivan, J. Making Sense of Factor Analysis. SAGE Publications Limited, 2003.

- World Health Organization. Understanding the behavioural and social drivers of vaccine uptake: WHO position paper. Weekly Epidemiological Record 2022;97(20):209-24.

- Katoto PDMC, Parker S, Coulson N, Pillay N, Cooper S, Jaca A, Mavundza E, Houston G, Groenewald C, Essack Z, Simmonds J, Shandu LD, Couch M, Khuzwayo N, Ncube N, Bhengu P, van Rooyen H, Wiysonge CS. Predictors of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in South African Local Communities: The VaxScenes Study. Vaccines 2022;10(3):353.

- Barros AJ, Hirakata VN. Alternatives for logistic regression in cross-sectional studies: an empirical comparison of models that directly estimate the prevalence ratio. BMC Medical Research Methodology 2003;3(1):1-3.

- Maree JE, Moitse KA. Exploration of knowledge of cervical cancer and cervical cancer screening amongst HIV-positive women. Curationis 2014;37(1):1209.

- Santos AC, Silva NN, Carneiro CM, Coura-Vital W, Lima AA. Knowledge about cervical cancer and HPV immunization dropout rate among Brazilian adolescent girls and their guardians. BMC Public Health 2020;20(1):301.

- Gendler Y, Ofri L. Investigating the influence of vaccine literacy, vaccine perception and vaccine hesitancy on Israeli parents’ acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine for their children: a cross-sectional study. Vaccines. 2021;9(12):1391.

- Mavundza EJ, Cooper S, Wiysonge CS. A Systematic Review of Factors That Influence Parents' Views and Practices around Routine Childhood Vaccination in Africa: A Qualitative Evidence Synthesis. Vaccines 2023;11(3):563.

- Tathiah N, Naidoo M, Moodley I. Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination of adolescents in the South African private health sector: Lessons from the HPV demonstration project in KwaZulu-Natal. South African Medical Journal 2015;105(11):933-936.

- Popa AD, Enache AI, Popa IV, Antoniu SA, Dragomir RA, Burlacu A. Determinants of the hesitancy toward COVID-19 vaccination in Eastern European countries and the relationship with health and vaccine literacy: a literature review. Vaccines 2022;10(5):672.

- Larson HJ, Cooper LZ, Eskola J, Katz SL, Ratzan S. Addressing the vaccine confidence gap. Lancet 2011;378(9790):526-535.

- Perlman S, Wamai RG, Bain PA, Welty T, Welty E, Ogembo JG. Knowledge and awareness of HPV vaccine and acceptability to vaccinate in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. PloS ONE 2014;9(3): e90912.

- Cooper S, Schmidt BM, Sambala EZ, Swartz A, Colvin CJ, Leon N, Wiysonge CS. Factors that influence parents' and informal caregivers' views and practices regarding routine childhood vaccination: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2021;10(10):CD013265.

- Cooper S, Wiysonge CS. Towards a More Critical Public Health Understanding of Vaccine Hesitancy: Key Insights from a Decade of Research. Vaccines 2023;11(7):1155.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population.

| Exploratory variables |

Summary statistics |

| |

All |

Accept HPV vaccine |

Do not accept HPV vaccine |

| Sample size |

N = 713 (100%) |

N = 667 (93.5%) |

N = 46 (6.5%) |

| Mean age (standard deviation) |

42.6 (11.6) years |

42.5 (11.4) years |

44.5 (12.9) years |

Gender:

Male

Female |

99 (13.9%)

614 (86.1%) |

88 (13.2%)

579 (86.8%) |

11 (23.9)

35 (76.1) |

Education:

Primary and below

Secondary

Tertiary and above

Missing |

45 (6.3%)

552 (77.4%)

113 (15.8%)

5 (0.4%) |

44 (6.6%)

513 (76.9%)

105 (15.7%)

5 (0.7%) |

1 (2.2%)

38 (82.6%)

7 (15.2%)

0 (0.0%) |

Household income:

<Less than 10,000 ZAR*10,0000- to 20,000 ZAR>More than 20,000 ZAR |

656 (92.0%)

41 (5.8%)

16 (2.2%) |

613 (91.9%)

38 (5.7%)

14 (2.1%) |

41 (89.1%)

3 (6.52)

2 (4.3%) |

Neighbourhood:

Chatsworth

Embo

Wentworth

Umlazi

Missing |

182 (25.5%)

144 (20.2%)

190 (26.6%)

197 (27.6%)

2 (0.3%) |

169 (25.3%)

134 (20.1%)

166 (24.9%)

196 (29.4%)

2 (0.3%) |

13 (28.3%)

10 (21.7%)

23 (50.0%)

0 (0.0%)

0 (0.0%) |

Table 2.

Predictors of acceptance of HPV in eThekwini District of KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa.

Table 2.

Predictors of acceptance of HPV in eThekwini District of KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa.

| Exploratory variables |

n |

cPR (95% CI) |

P value |

aPR (95% CI) |

P value |

| Age |

713 |

1.00 (0.99 to 1.00) |

0.30 |

--- |

--- |

Gender:

Male

Female |

99

614 |

Baseline

1.06 (0.99 to 1.14) |

0.11 |

---

--- |

---

--- |

Education level:

Primary and below

Secondary

Tertiary |

4

5552

113 |

Baseline

0.95 (0.91 to 1.00)

0.96 (0.90 to 1.02) |

---

0.0

50.21 |

---

---

--- |

---

---

--- |

Household income:

0 to 10,000 ZAR

10,00 to 20,000 ZAR

More than 20,000 ZAR |

656

41

16 |

Baseline

0.99 (0.91 to 1.08)

0.93 (0.77 to 1.12) |

---

0.80

0.47 |

---

---

--- |

---

---

--- |

Vaccinated against COVID-19:

No

Yes |

260

452 |

Baseline

1.02 (0.98 to 1.07) |

---

0.28 |

---

--- |

---

--- |

Knowledge of HPV:

No

Yes |

206

504 |

Baseline

1.06 (1.01 to 1.11) |

---

0.03 |

---

1.00 (0.97 to 1.04) |

---

0.79 |

Knowledge of school-based HPV vaccination programme:

No

Yes |

98

602 |

Baseline

1.23 (1.10 to 1.36) |

---

<0.001 |

---

1.16 (1.06 to 1.28) |

---

0.002 |

View on importance of HPV vaccine:

Not important

Very important |

90

618 |

Baseline

1.12 (1.03 to 1.23) |

---

0.012 |

---

1.03 (0.95 to 1.12) |

---

0.45 |

Recommendation from religious leaders on vaccines:

Discourages vaccination

Encourages vaccination |

20

691 |

Baseline

1.45 (1.05 to 2.00) |

---

0.023 |

---

1.30 (0.98 to 1.72) |

---

0.07 |

View on HPV vaccine safety:

Skeptical

Very safe |

270

439 |

Baseline

1.17 (1.12 to 1.24) |

<0.001 |

1.14 (1.08 to 1.19) |

<0.001 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).