Submitted:

15 February 2025

Posted:

17 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

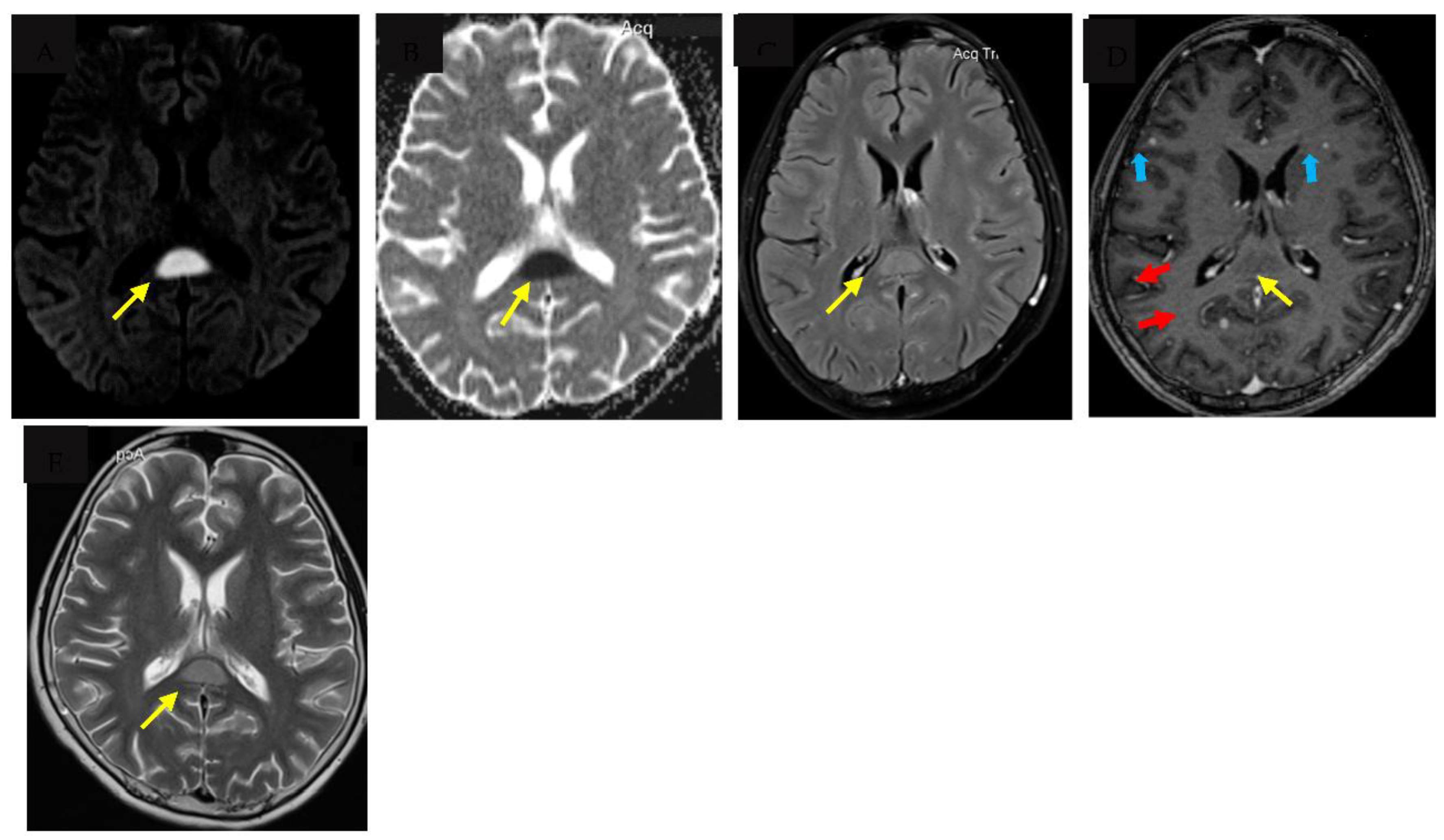

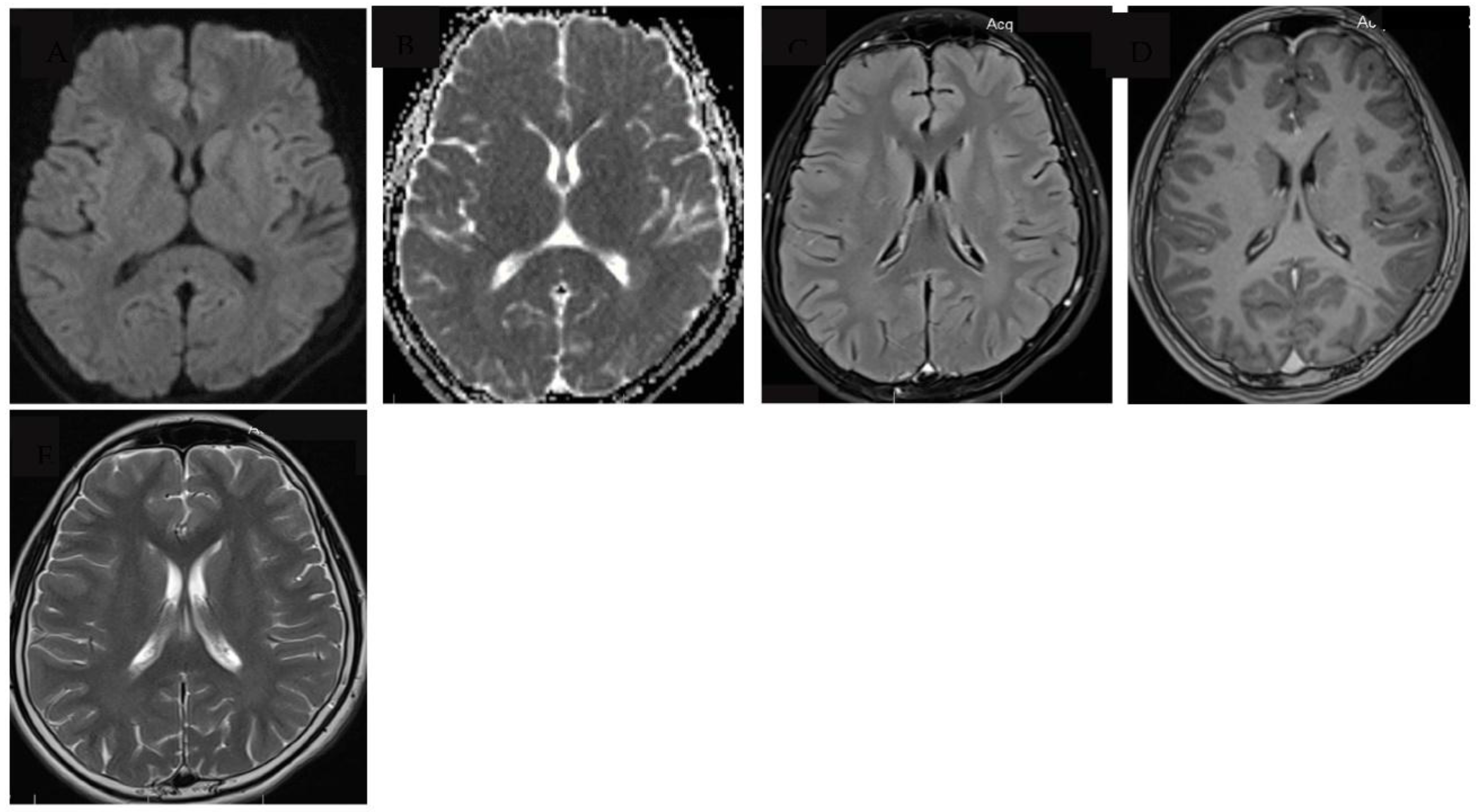

Tuberculous meningitis (TBM) is the most severe form of tuberculosis, disproportionately affecting vulnerable populations such as young children and people living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Major challenges to accurate and early diagnosis of TBM are the non-specific clinical features which overlap with other infectious syndromes and the lack of adequately sensitive tests to detect Mycobacterium Tuberculosis in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Diagnosis is therefore still dependent on clinical suspicion along with clinical features, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) characteristics and where facilities are available, neuroimaging. Typical neuroimaging features of TBM include hydrocephalus, infarcts, tuberculomas and basal exudates, however less well described are very rare features such as cytotoxic lesion of the corpus callosum (CLOCC) otherwise known as transient splenic lesion. We describe the first case report of a child with confirmed TBM who had a very rare presentation of CLOCC, present a literature review on the pathophysiology and alternative aetiologies where CLOCC is more commonly seen.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Case report

3. Discussion

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed consent statement

Data availability statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Global tuberculosis report 2024. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2024. Licence:CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- Roadmap towards ending TB in children and adolescents, third edition. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2023. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- du Preez K, Jenkins HE, Martinez L, Chiang SS, Dlamini SS, Dolynska M, et al. Global burden of tuberculous meningitis in children aged 0-14 years in 2019: a mathematical modelling study. Lancet Glob Health. 2025;13(1):e59-e68. [CrossRef]

- Donovan J, Cresswell FV, Thuong NTT, Boulware DR, Thwaites GE, Bahr NC, et al. Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra for the Diagnosis of Tuberculous Meningitis: A Small Step Forward. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(8):2002-5. [CrossRef]

- Donovan J, Walker TM. Diagnosing tuberculous meningitis: a testing process. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2021;25(8):605-6. [CrossRef]

- Chiang S, Khan F, Milstein M, Tolman A, Benedetti A, Starke J, et al. Treatment outcomes of childhood tuberculous meningitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14:947-57. [CrossRef]

- Wen A, Cao WF, Liu SM, Zhou YL, Xiang ZB, Hu F, et al. Incidence and Risk Factors of Cranial Nerve Palsy in Patients with Tuberculous Meningitis: A Retrospective Evaluation. Infect Drug Resist. 2023;16:829-41. [CrossRef]

- van Well GT, Paes BF, Terwee CB, Springer P, Roord JJ, Donald PR, et al. Twenty years of pediatric tuberculous meningitis: a retrospective cohort study in the western cape of South Africa. Pediatrics. 2009;123(1):e1-8.

- van der Merwe DJ, Andronikou S, Van Toorn R, Pienaar M. Brainstem ischemic lesions on MRI in children with tuberculous meningitis: with diffusion weighted confirmation. Childs Nerv Syst. 2009;25(8):949-54. [CrossRef]

- Thwaites GE, van Toorn R, Schoeman J. Tuberculous meningitis: more questions, still too few answers. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(10):999-1010.

- Grobbelaar M, van Toorn R, Solomons R. Lumbar Cerebrospinal Fluid Evolution in Childhood Tuberculous Meningitis. J Child Neurol. 2018;33(11):700-7. [CrossRef]

- Huynh J, Abo YN, du Preez K, Solomons R, Dooley KE, Seddon JA. Tuberculous Meningitis in Children: Reducing the Burden of Death and Disability. Pathogens. 2021;11(1).

- Patel VB, Burger I, Connolly C. Temporal evolution of cerebrospinal fluid following initiation of treatment for tuberculous meningitis. S Afr Med J. 2008;98(8):610-3.

- Ssebambulidde K, Gakuru J, Ellis J, Cresswell FV, Bahr NC. Improving Technology to Diagnose Tuberculous Meningitis: Are We There Yet? Front Neurol. 2022;13:892224.

- World Health Organisation. WHO consolidated guidelines on tuberculosis. Module 3: diagnosis - rapid diagnostics for tuberculosis detection 2020 [Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/who-consolidated-guidelines-on-tuberculosis-module-3-diagnosis---rapid-diagnostics-for-tuberculosis-detection.

- Davis AG, Rohlwink UK, Proust A, Figaji AA, Wilkinson RJ. The pathogenesis of tuberculous meningitis. J Leukoc Biol. 2019;105(2):267-80. [CrossRef]

- Theron S, Andronikou S, Grobbelaar M, Steyn F, Mapukata A, du Plessis J. Localized basal meningeal enhancement in tuberculous meningitis. Pediatr Radiol. 2006;36(11):1182-5.

- Andronikou S, Wieselthaler N. Modern imaging of tuberculosis in children: thoracic, central nervous system and abdominal tuberculosis. Pediatr Radiol. 2004;34(11):861-75.

- Tai MS, Viswanathan S, Rahmat K, Nor HM, Kadir KAA, Goh KJ, et al. Cerebral infarction pattern in tuberculous meningitis. Sci Rep. 2016;6:38802. [CrossRef]

- Pienaar M, Andronikou S, van Toorn R. MRI to demonstrate diagnostic features and complications of TBM not seen with CT. Childs Nerv Syst. 2009;25(8):941-7.

- Sanei Taheri M, Karimi MA, Haghighatkhah H, Pourghorban R, Samadian M, Delavar Kasmaei H. Central nervous system tuberculosis: an imaging-focused review of a reemerging disease. Radiol Res Pract. 2015;2015:202806. [CrossRef]

- Desai N, Gable B, Ortman M. Tuberculous brain abscess in an adolescent with complex congenital cyanotic heart disease. Heart. 2013;99(16):1220-1.

- Kumar R, Pandey CK, Bose N, Sahay S. Tuberculous brain abscess: clinical presentation, pathophysiology and treatment (in children). Childs Nerv Syst. 2002;18(3-4):118-23. [CrossRef]

- Tada H, Takanashi J, Barkovich AJ, Oba H, Maeda M, Tsukahara H, et al. Clinically mild encephalitis/encephalopathy with a reversible splenial lesion. Neurology. 2004;63(10):1854-8.

- Garcia-Monco JC, Cortina IE, Ferreira E, Martínez A, Ruiz L, Cabrera A, et al. Reversible splenial lesion syndrome (RESLES): what's in a name? J Neuroimaging. 2011;21(2):e1-14.

- Oztoprak I, Engin A, Gumus C, Egilmez H, Oztoprak B. Transient splenial lesions of the corpus callosum in different stages of evolution. Clin Radiol. 2007;62(9):907-13.

- Starkey J, Kobayashi N, Numaguchi Y, Moritani T. Cytotoxic Lesions of the Corpus Callosum That Show Restricted Diffusion: Mechanisms, Causes, and Manifestations. Radiographics. 2017;37(2):562-76. [CrossRef]

- Doherty MJ, Jayadev S, Watson NF, Konchada RS, Hallam DK. Clinical implications of splenium magnetic resonance imaging signal changes. Arch Neurol. 2005;62(3):433-7.

- Yum KS, Shin DI. Transient splenial lesions of the corpus callosum and infectious diseases. Acute Crit Care. 2022;37(3):269-75. [CrossRef]

- Hayashi M, Ueda M, Hayashi K, Kawahara E, Azuma SI, Suzuki A, et al. Case report: Clinically mild encephalitis/encephalopathy with a reversible splenial lesion: an autopsy case. Front Neurol. 2023;14:1322302.

- Moors S, Nakhostin D, Ilchenko D, Kulcsar Z, Starkey J, Winklhofer S, et al. Cytotoxic lesions of the corpus callosum: a systematic review. Eur Radiol. 2024;34(7):4628-37.

- Colas RA, Nhat LTH, Thuong NTT, Gómez EA, Ly L, Thanh HH, et al. Proresolving mediator profiles in cerebrospinal fluid are linked with disease severity and outcome in adults with tuberculous meningitis. The FASEB Journal. 2019;33(11):13028-39. [CrossRef]

- Thuong NTT, Heemskerk D, Tram TTB, Thao LTP, Ramakrishnan L, Ha VTN, et al. Leukotriene A4 Hydrolase Genotype and HIV Infection Influence Intracerebral Inflammation and Survival From Tuberculous Meningitis. J Infect Dis. 2017;215(7):1020-8.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).