1. Introduction

Solid oxide fuel cells (SOFCs) can directly convert chemical energy into electrical energy and are promising energy conversion devices [

1]. A SOFC single cell consists of an electrolyte, a cathode, and an anode. Among various factors, the polarization resistance of the cathode, which is the energy required to overcome the oxygen reduction reaction (ORR), has the greatest effect on reaction activity. Therefore, reducing cathode polarization resistance and improving cathode performance are effective ways to increase the power generation efficiency of SOFCs [

2]. Exploring new cathode materials with high catalytic activity will become a research hotspot in the field of SOFCs.

Given their excellent electrochemical properties and mixed ion–electron conductivity, perovskite oxides are attracting considerable attention as a new type of mixed ion–electron conductor (MIEC) [

3]. Extending the ORR region to the entire electrode surface beyond the electrolyte–electrode–gas three-phase boundary is beneficial to improve electrode performance and has high research value in the field of SOFC cathode materials. Woo et al. [

4] found that the conductivity of SOFC cathode materials with Pr and La at the A site is higher than that of compounds with Sm and Gd, and the conductivity of Co-based compound at the B site is considerably higher than that of Fe-based materials [

5,

6]. Jiang et al. [

7] showed that the electrical conductivity of Pr

1+xBa

1-xCo

2O

5+δ as a SOFC cathode material is generally above 550 S/cm. Co-based materials have become a hot topic in the research on SOFC cathode materials due to their excellent electrical conductivity and power density [

8,

9]. However, given their high thermal expansion coefficient, they have poor thermal matching with electrolyte materials [

10]. Doping Ta [

11], Ni [

12], Nb [

13], and Cu [

14] at the B site of Co-based materials can promote the ORR at the electrode and improve electrochemical performance and catalytic activity. Ni doping at the B site can reduce proton migration capacity, increase oxygen vacancy concentration, and improve proton absorption and ORR catalytic activity [

15]. Zhu et al. [

12] demonstrated that the Pr

0.7Ba

0.3Co

0.6Fe

0.2Ni

0.2O

3+δ material has good ORR activity in dry and wet air.

In this study, PrBaCo1-XNiXO3+δ (PBCNix, X = 0, 0.05, 0.1, 0.15) cathode materials were prepared through the sol–gel method with Ni as the doping element. The synthesized perovskite PBCNiX cathode material was characterized by using X-ray diffraction (XRD), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and energy disperse spectroscopy (EDS). The effects of Ni content on the microstructure and electrochemical properties of the PBC cathode materials were investigated.

3. Results and Discussion

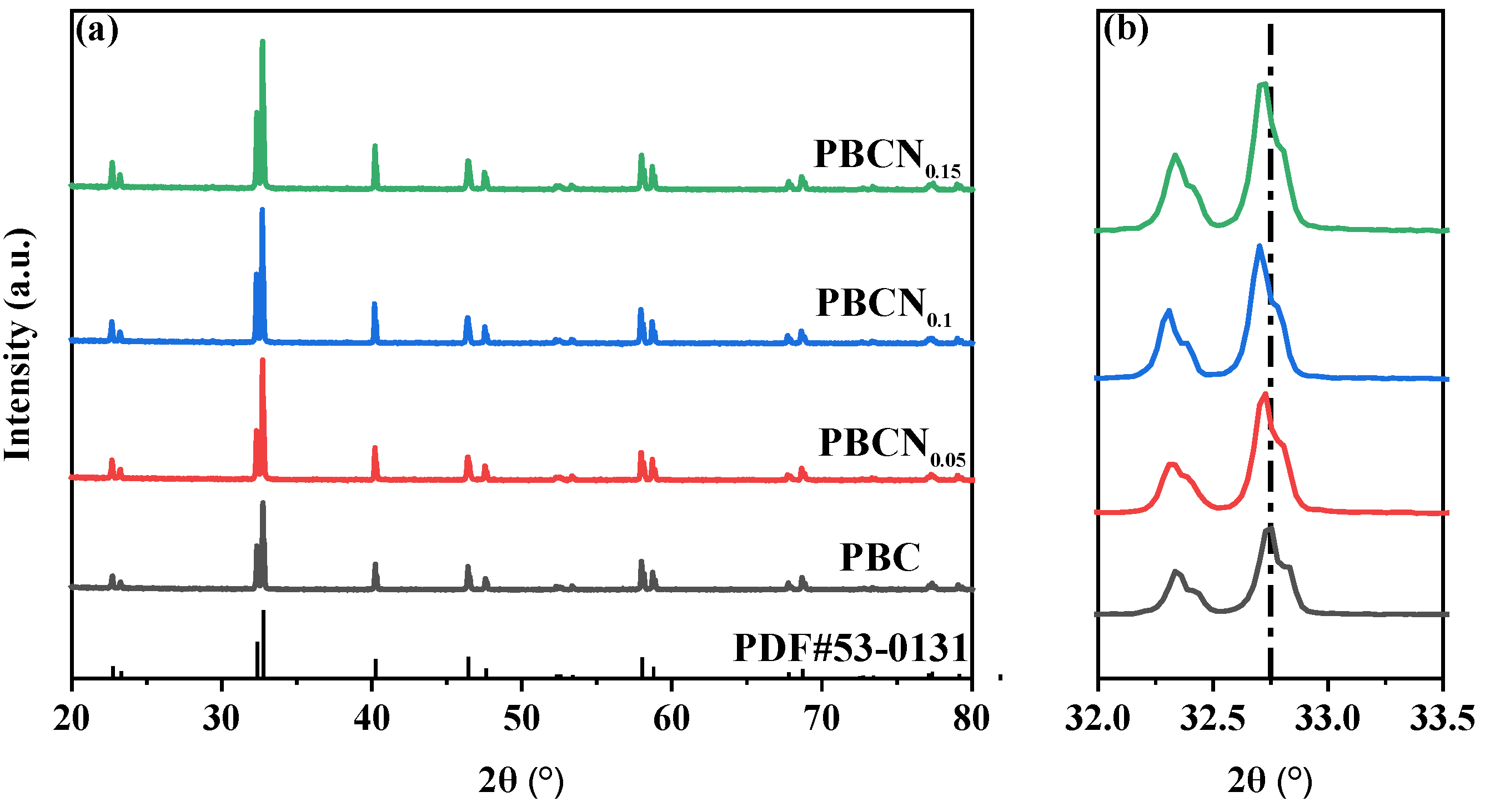

The XRD pattern of PBCNi

X (X = 0, 0.05, 0.1, 0.15) is provided in

Figure 1(a). The diffraction peaks are narrow and sharp, and the main diffraction peak position of the Ni-doped sample is consistent with the structure of Pr

0.5Ba

0.5CoO

3+δ (PBC, PDF#53-0131), showing a typical quartet-phase perovskite structure [

16]. These results demonstrate that perovskite PBCNi

X materials have been prepared successfully and no secondary phase has formed.

Figure 1(b) presents an enlarged cross-section of 2θ = 32°–33.5°. The characteristic peaks of the PBCNi

X materials have shifted to a low angle with the doping of Ni. Given that the radius of the Ni

2+ ion is greater than that of the Co

3+ ion, the XRD diffraction peak caused by lattice expansion shifts to a low angle, and the deviation of the diffraction peak gradually increases with the increase in doping amount. The Rietveld method was used to refine the XRD pattern of PBC to study the effect of Ni ion doping on the crystal structure of PBC further.

Figure S1 shows the Rietveld-refined pattern of PBCNi

X, which is consistent with the XRD patterns.

Table S1 shows that materials with high Ni doping amounts have large cell volumes, indicating that Ni ions have successfully entered the lattice of the PBC cathode materials. The results show that the prepared PBCNi

X has the same spatial structure as the undoped PBC, indicating that Ni doping does not change the original crystal structure and has a simple tetragonal structure (P4/mmm).

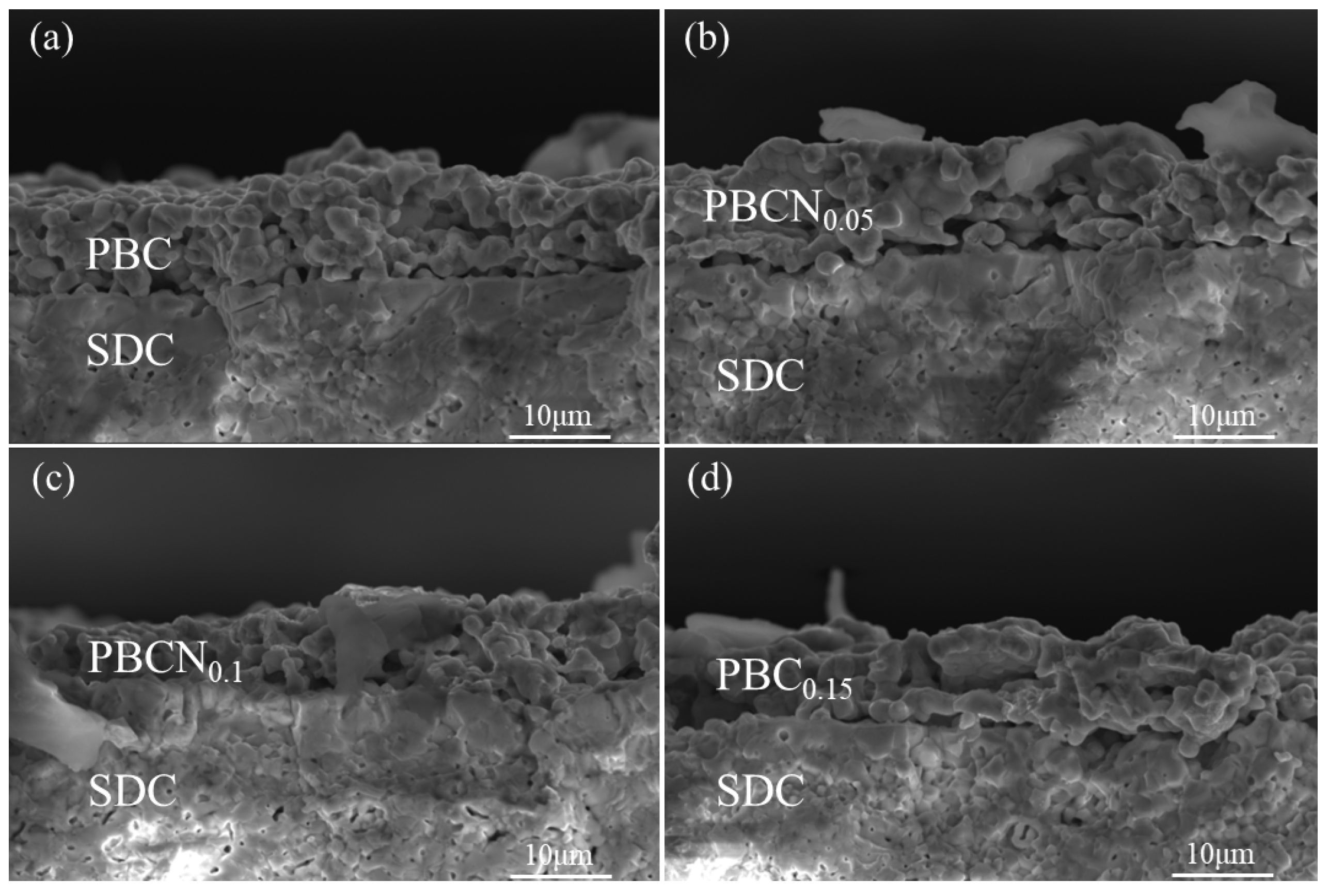

Figure 2 shows the SEM images of the symmetrical cells of PBC and the PBCNi

X cathode materials after calcination at 1100 °C and subsequent electrochemical performance tests. The results indicate that Ni doping has no discernible effect on the structure of PBC. The prepared cathode materials are loose and porous and therefore have relatively high porosity. The formation of a porous structure in the cathode is conducive to providing additional active sites for ORR and offering supplemental gas diffusion channels, which are beneficial for gas exchange and diffusion. The adhesion between the cathode material and SDC electrolyte is good, and no delamination or fracture is observed, indicating that the cathode and SDC electrolyte have good thermal compatibility.

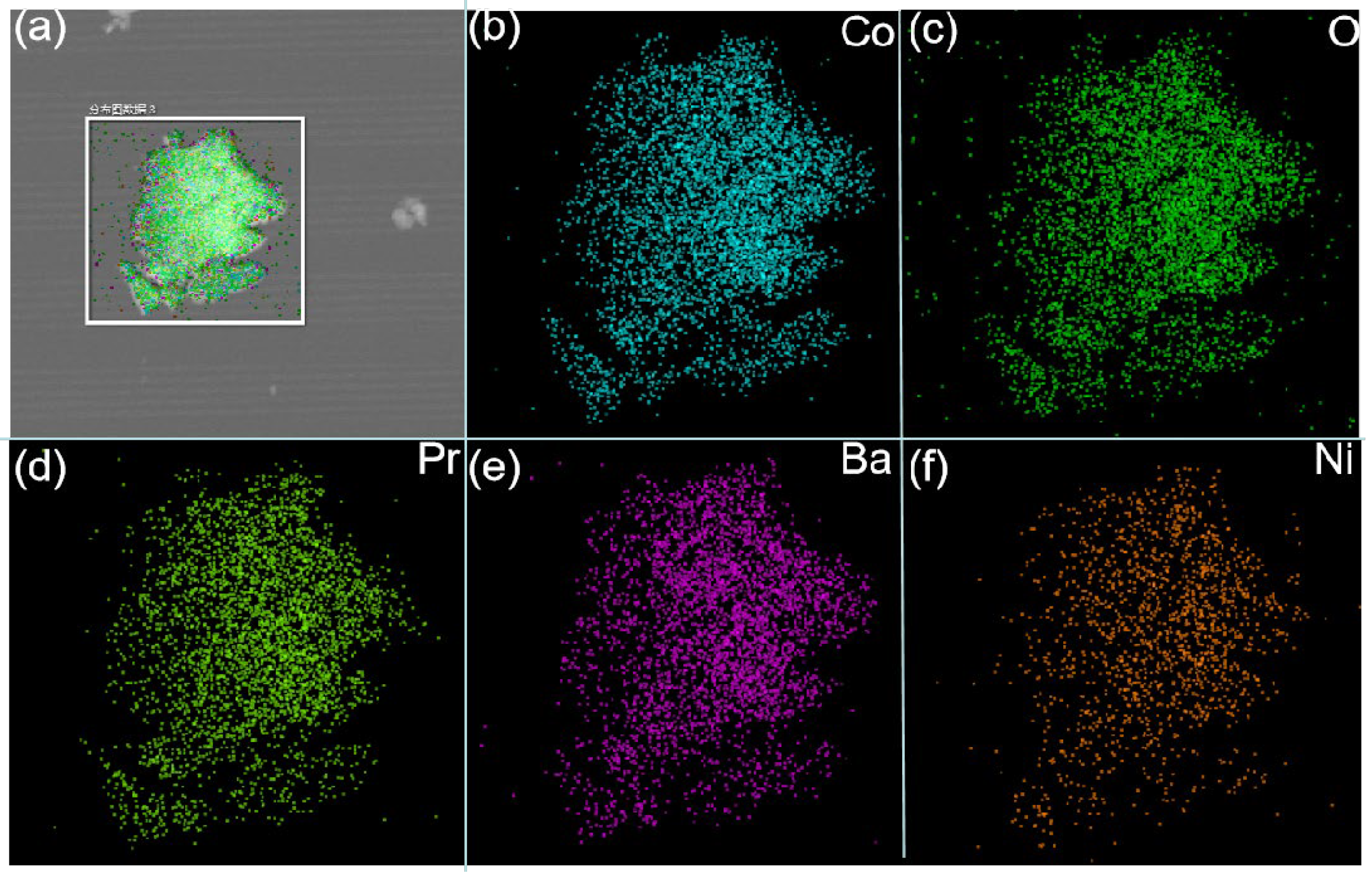

Figure 3(b–f) show the element distribution maps of PBC and PBCNi

0.1, as well as the corresponding energy dispersion spectra, to illustrate the distribution of elements in the cathode materials doped with Ni ions. The results show that all elements in the synthesized materials are uniformly distributed, no element agglomeration has occurred, and the peaks of all elements are detectable. These findings further prove that Ni ions are effectively doped into the PBC materials.

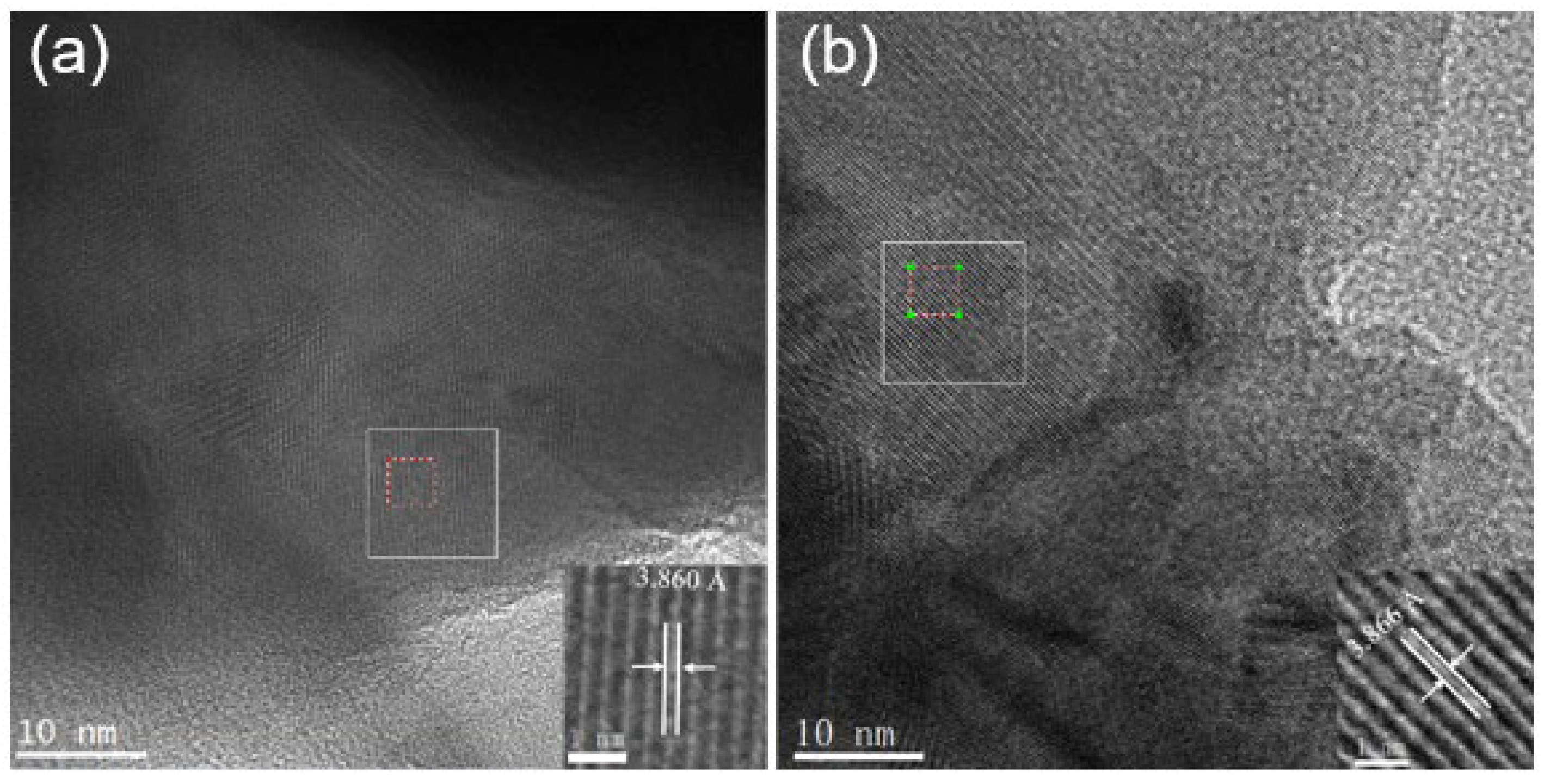

Figure 4 shows the HR-TEM and locally amplified images.

Figure 4(a) depicts that the diffraction fringe width of the substrate material (PBC) is 3.860 Å.

Figure 4(b) illustrates that the diffraction fringe width of the cathode material with doping amount X = 0.1 is 3.866 Å. The TEM result is consistent with the refined XRD data. The synthesized PBCNi

0.1 material is further shown to be centrosymmetric and has a simple tetragonal structure (P4/mmm).

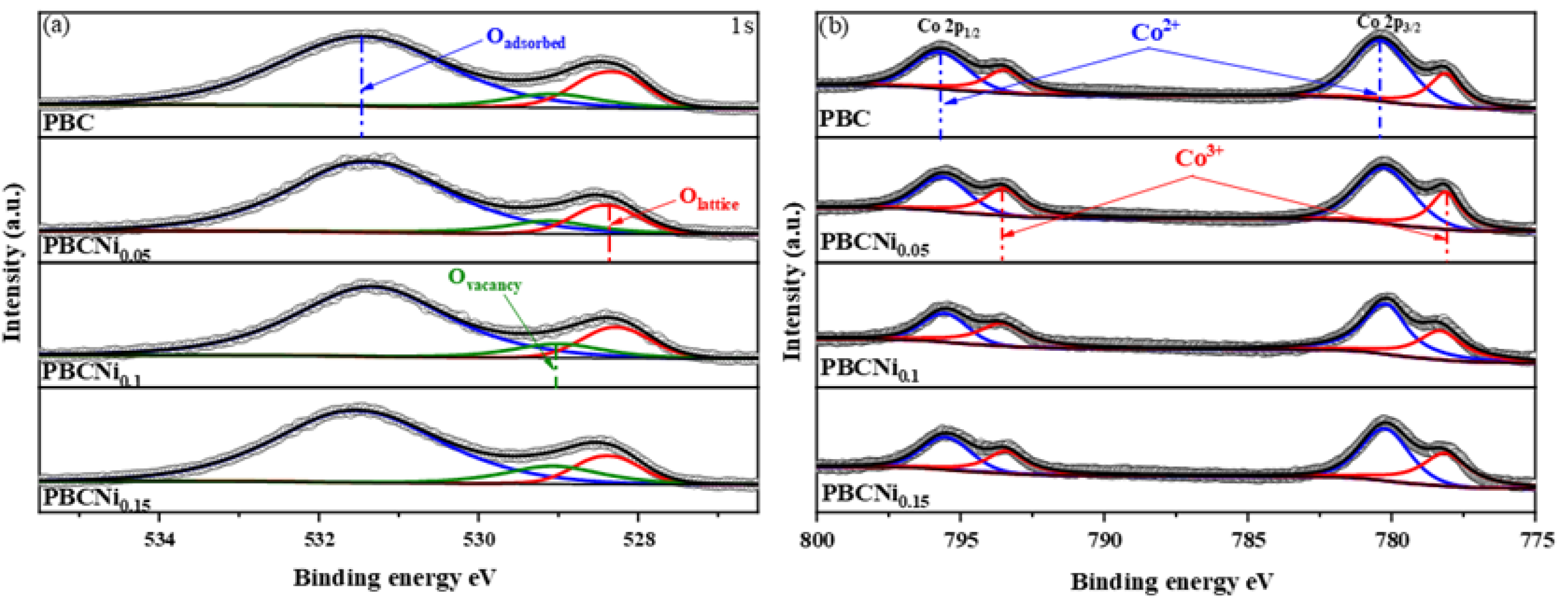

XPS was used for characterization to determine the surface composition of the PBCNi

X materials. The XPS spectral data of the O1s and Co2p orbitals in the PBCNi

X samples were fitted, and the corresponding spectra are provided in

Figure 5.

Figure 5(a) shows that the O element exists in three forms: lattice oxygen (

Olattice, 528.54 eV), oxygen vacancy (

Ovacancy, 529.07 eV), and adsorbed oxygen (

Oadsorbed, 531.34 eV). As shown in

Table S2, the concentration of

Ovacancy in the Ni-doped samples is higher than that in PBC, indicating that Ni doping can increase the concentration of oxygen vacancies on the material surface. The PBCNi

X cathode materials were tested through electron paramagnetic resonance, as illustrated in

Figure S2. The oxygen vacancy signal increases with Ni doping, indicating that Ni doping can increase the concentration of oxygen vacancies in the material and enhance the catalytic activity of oxygen [

17]. As shown in

Figure 5(b), low-valent Ni ions are doped into the PBC materials to replace Co. Co is induced to change from low valence to high valence, generating additional Co

3+, as shown in

Table S3, to maintain charge balance. Given that the ionic radius of Ni

2+ ions is larger than that of Co

3+ ions, additional oxygen vacancies are produced. This result is consistent with the findings of the previous analysis of the O1s orbital. In summary, Ni-doped samples can increase the oxygen vacancy content of the materials and are expected to become cathode materials with excellent electrical performance.

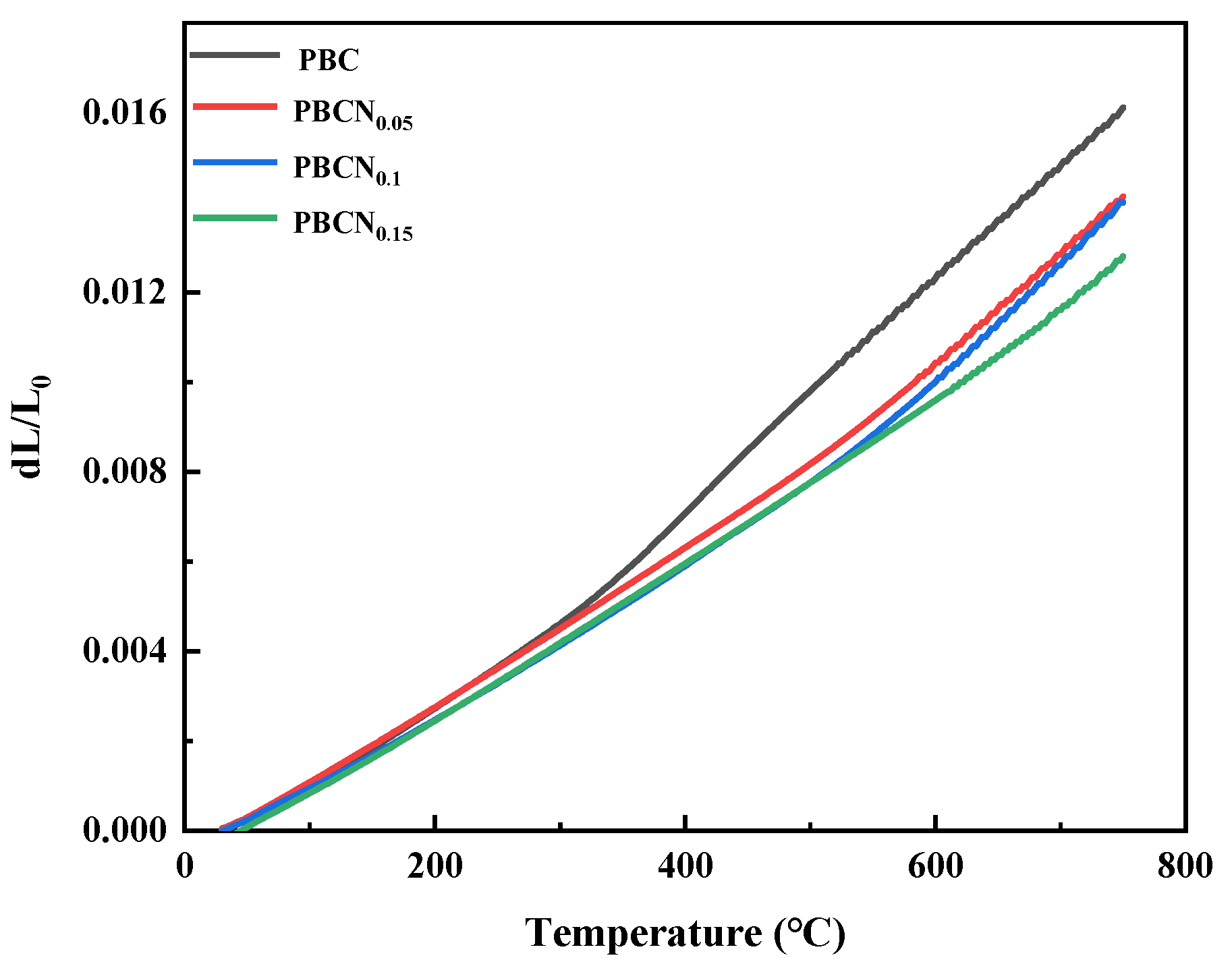

Figure 6 shows that the average TEC values of the PBCNi

X (X = 0, 0.05, 0.1, 0.15) series cathode materials within the temperature range of 30 °C–800 °C are 22.0474 × 10

−6 K

−1 (X = 0), 19.598 × 10

−6 K

−1 (X = 0.05), 19.4837 × 10

−6 K

−1 (X = 0.1), and 18.0548 × 10

−6 K

−1 (X = 0.15). The TEC of SDC is 12.14 × 10

−6 K

−1 [

18]. The doping of Ni reduces the average TEC of the PBC materials, making it close to that of SDC, indicating good thermal matching between the PBCNi

X cathode materials and SDC electrolyte. It thus minimizes the risk of fracture caused by TEC mismatch between the electrolyte and cathode material and confers the cell with good stability and a long service life.

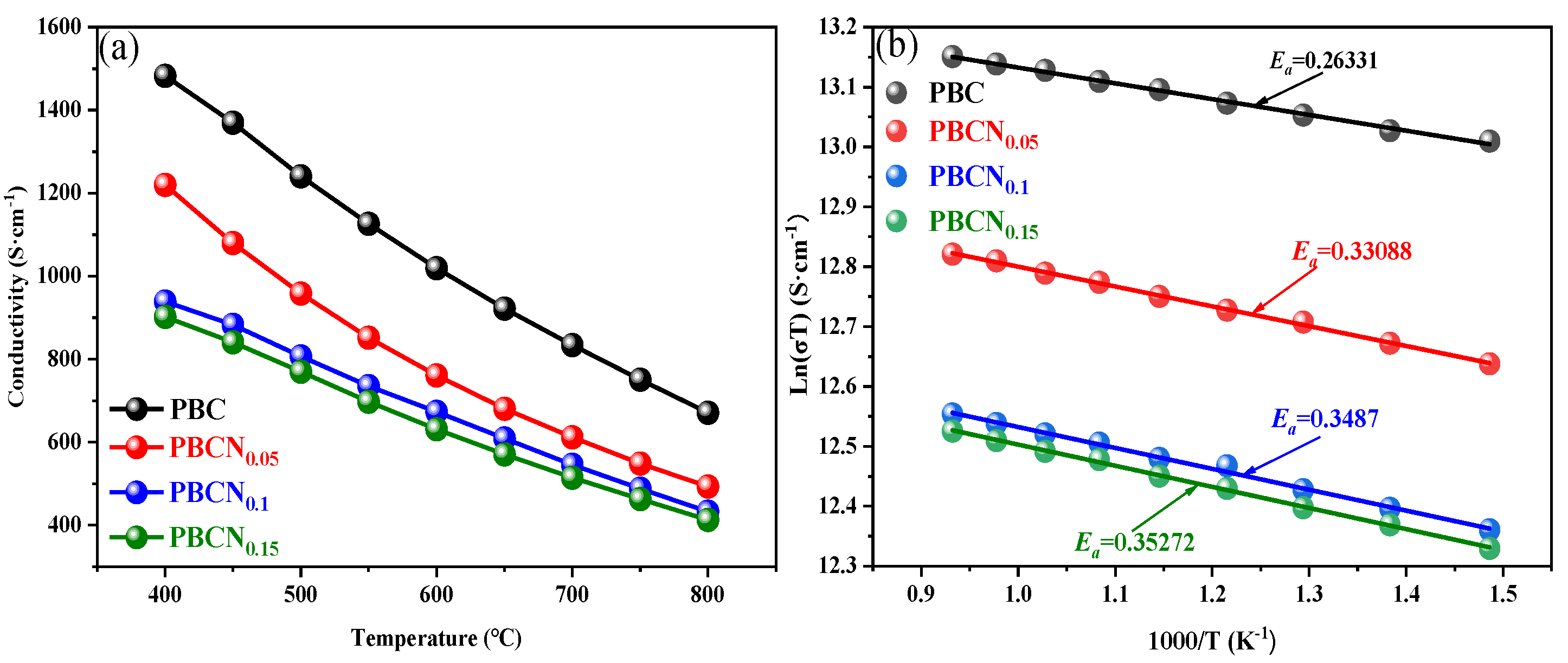

Figure 7(a) shows the relationship between temperature and the electrical conductivity (σ) of the PBCNi

X materials in an air atmosphere within the temperature range of 400 °C–800 °C. As the temperature increases, the conductivity of the sample decreases. The conductivity of the PBC and PBCNi

X series cathode materials decreases in the range of 400 °C–800 °C. At the same temperature, the electrical conductivity of the PBCNi

X series materials is lower than that of PBC because electron transfer between Co

2+ and Co

3+ enhances electronic conductivity. With the increase in Ni doping content, the concentration of high-valent Co ions in the PBCNi

X cathode materials decreases, whereas that of oxygen vacancies increases, resulting in a decrease in the electrical conductivity of the materials.

Figure 7(b) presents the Arrhenius plot of the electrical conductivity of the PBCNi

X cathode materials versus temperature within the temperature range of 400 °C–800 °C. The activation energy

Ea of the PBCNi

X cathode materials with different Ni ion doping amounts was calculated by using the Arrhenius formula, as shown in

Figure 7(b) [

19].

Where

k is the reaction rate constant at temperature

T, which is 8.617 × 10

−5; σ is the electrical conductivity; A is the pre-exponential factor; and

Ea is the conductivity activation energy. Consistent with the trend of the change in electrical conductivity, the conductivity activation energy of the PBCNi

X cathode materials continues to increase with the increase in the doping amount of Ni ions. Although electrical conductivity decreases due to the doping of Ni, it can still reach 900 S/cm at 400 °C, meeting the requirements for the electrical conductivity of cathode material samples [

20].

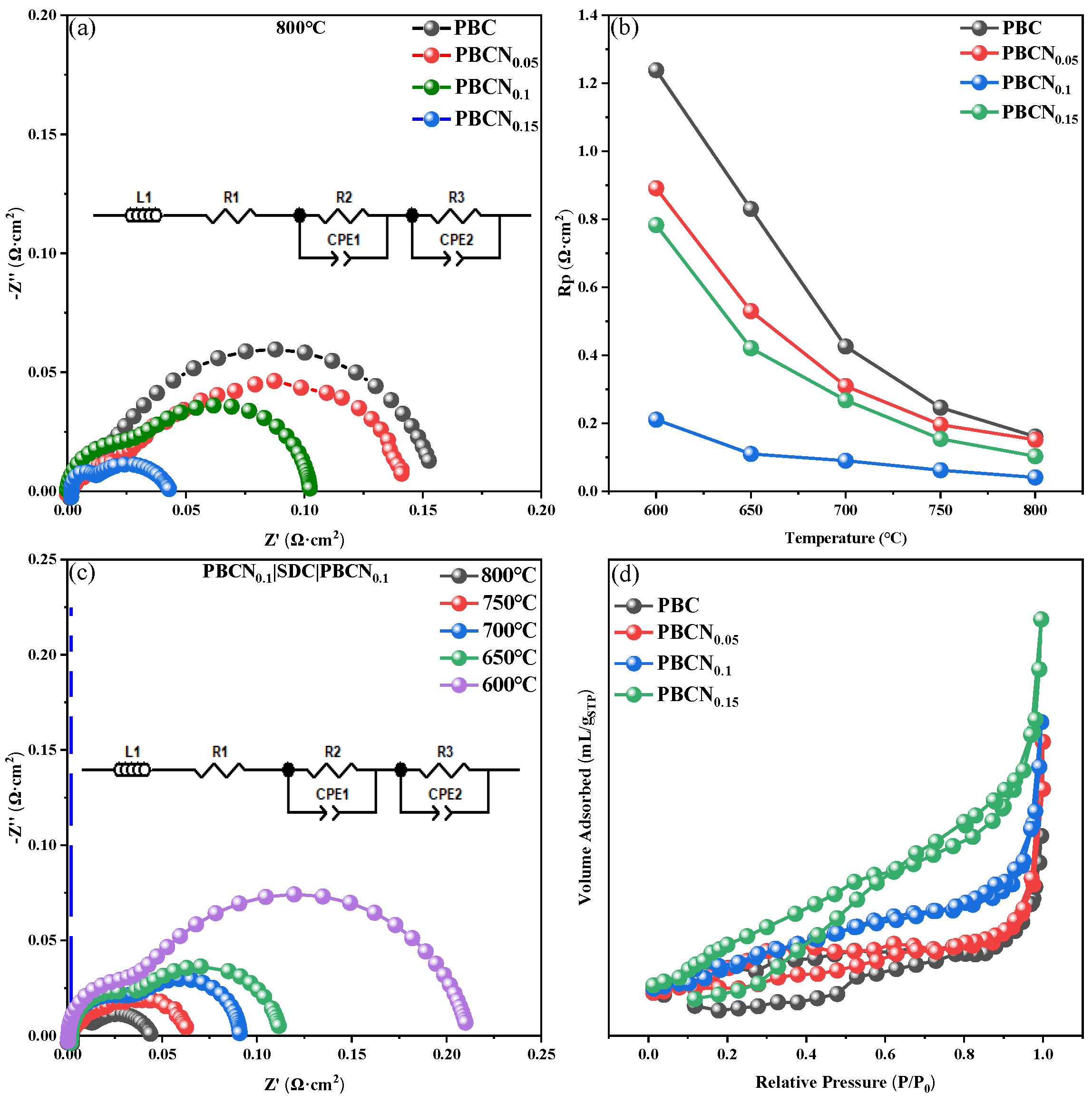

The electrochemical characteristics of the PBCNi

X cathodes with a symmetrical cell structure and SDC electrolyte were investigated through AC impedance spectroscopy.

Figure 8(a) shows that the polarization resistance (

Rp) of PBC at 800 °C is approximately 0.159 Ω·cm², whereas the corresponding resistances of the PBCNi

X materials with X = 0.05, 0.10, 0.15 are only approximately 0.146, 0.041, and 0.103 Ω·cm², respectively. Ni ion doping remarkably reduces the polarization resistance at the cathode interface. As the Ni doping amount increases to 0.1,

Rp gradually decreases.

Figure 8(b) provides the impedance spectra of the PBCNi

X series cathodes at 600 °C–800 °C. After Ni is doped at the B site of PBCNi

X,

Rp initially decreases then increases. As illustrated in

Figure 8(c), when the Ni doping amount is 0.1, impedance continuously increases with the decrease in working temperature, reaching a minimum value of 0.041 Ω·cm² at 800 °C. This finding indicates that Ni doping has a substantial effect on the electrochemical performance of the PBC cathode materials. The overall performance of SOFC cathodes has been found to depend mainly on O ion transport performance and the catalytic performance of ORR [

21]. Excessive Co content can lead to a decrease in the oxygen vacancy coefficient δ. By doping Ni to improve the stoichiometry of Co in the cathode material, the oxygen vacancy coefficient can be increased and electrochemical impedance can be reduced. The performance of the PBC and PBCNi

X cathode materials depends not only on cathode conductivity, it also depends on the catalytic activity of the cathode surface and gas transport rate through the porous cathode. Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) pore size distribution tests were conducted to explore the catalytic activity of the cathode surface and gas transport rate through the porous cathode, and the results are provided in

Figure 8(d). With the doping of Ni ions, the specific surface area of the cathode materials gradually increases. This effect would enhance the exchange of the cathode with air oxygen, increase reaction activity, and reduce impedance. When the Ni doping amount is greater than 0.1, the polarization impedance shows an increasing trend again because with the continuous increase in doping amount, the excessively high oxygen vacancy concentration would cause the association of defects in the cathode material and lead to the localization of oxygen vacancies [

22], thereby reducing the O ion transport rate and increasing

Rp. As shown in

Table 1, the polarization impedance of PBCNi

0.1 is already lower than that of most Co-based materials. In summary, the PBCNi

0.1 material can be considered as a potential and promising cathode material with prospects for SOFCs.

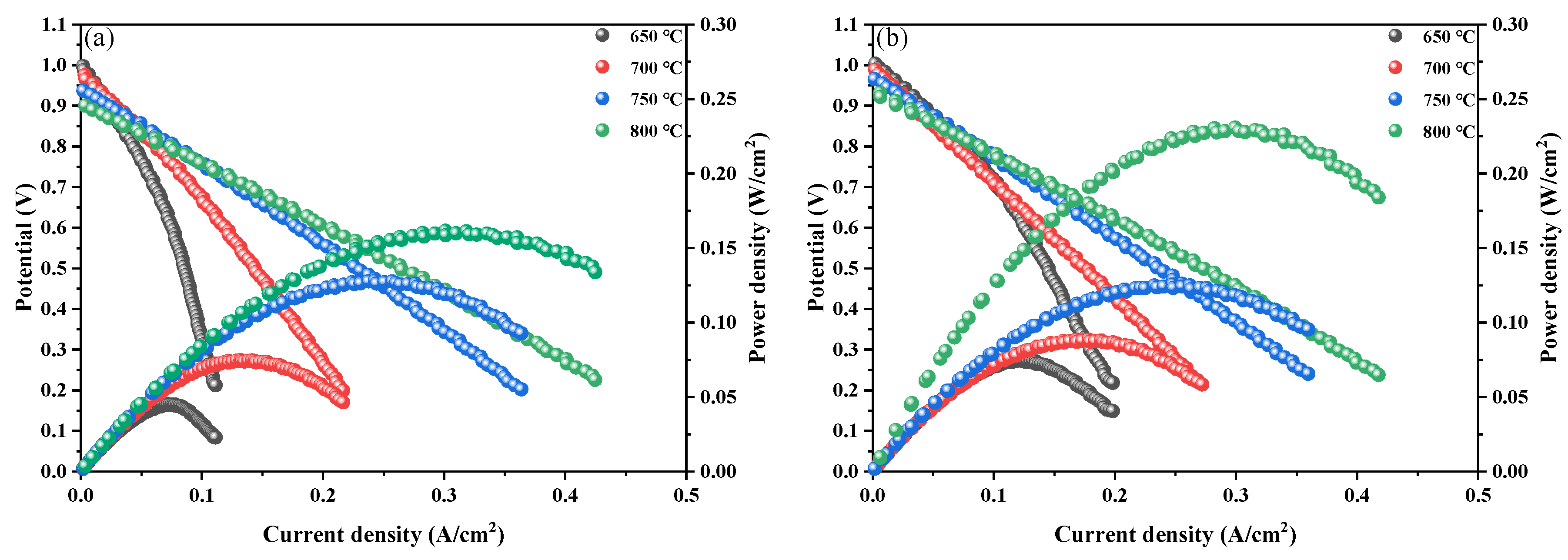

The electrolyte-supported single cell has excellent performance in terms of heat resistance and mechanical strength because of its relatively hard electrolyte layer. It was chosen to construct and evaluate the output performance of PBCN

X as the cathode of SOFCs because of its simple preparation and flexible selection of electrode materials.

Figure 9(a) and (b) show the power densities of PBC and PBCN

0.1 at 650 °C–800 °C in a hydrogen atmosphere. The results indicate that power density increases with the rise in temperature. At 650 °C, the open-circuit voltages (OCVs) are 0.99 and 1.0 V, which are lower than the theoretical voltage of 1.1 V [

27]. These low OCVs are attributed to the partial reduction of Ce

4+ in the SDC electrolyte into Ce

3+ under the reducing atmosphere. This phenomenon leads to electronic conductivity and internal short circuits [

28]. At 800 °C, the power density of the single cell prepared with PBC is 161.1 mW/cm

2 and that of the single cell prepared with PBCNi

0.1 has increased by 69.5 mW/cm

2 to 230.6 mW/cm

2. This result indicates that Ni doping enhances the output power density of the PBC cell and improves its catalytic activity.