1. Introduction

The College of American Pathologists guidance states “a contaminated urine culture was defined as the presence of more than 2 isolates at greater than or equal to 10 000 CFU/mL” (Valenstein P 1998; Bekeris LG 2008). This includes commensal microbes thought to be of skin origin or, in adult females, vulvo-vaginal contaminants (Brubaker L 2021a). Standard practice is to resample although often the same result is obtained. Then, the predominant microbe is reported (often E. coli), while the other detected microbes are often ignored (SfeirMM 2018). Examples include reports of “contamination” or “mixed flora” in asymptomatic bacteriuria of pregnant individuals (46.7%) (O'Leary BD 2020), in general practice (54.9%) (Hansen MA 2022), and in outpatient clinics (46.2%) (Whelan P 2022). This is comparable to results obtained with a multiplex polymerase chain reaction (M-PCR) panel, where 56.1% of an older cohort (>65 years old) with diagnosed urinary tract infection (UTI) had polymicrobial (more than one microbe) results (Vollstedt A 2020).

While the method of urine collection can sample different aspects of the urinary tract (e.g., suprapubic aspirate and transurethral catheter: bladder and upper urinary tract; midstream void: entire urinary tract including urethra and peri-urethral skin plus urogenital regions), there are subtle differences in microbes detected depending on sampling technique (Chen YB 2020; Pohl HG 2020; Brubaker L 2021a; Wang D 2023; Du J 2024). Nevertheless, midstream void or the so-called “clean catch” is most often used in clinical practice (LaRocco MT 2015; Moreland RB 2024). A recent meta-analysis of urine collection methods and contamination concluded that methods to decrease contamination (e.g. cleansing, boric acid preservative, and refrigerating urine sample to prevent nonspecific growth) were of limited value (LaRocco MT 2015). The possibility remains that many microbes reported as contamination or mixed flora could represent potential polymicrobial infection that, in some cases, may breach the renal urine blood barrier and progress to urosepsis (Siegman-Igra Y 1994; Siegman-IgraY 1994; Peach BC 2016; Akhtar A 2021; Collaborators 2024). Distinguishing contamination from the presence of clinically relevant microbes is essential to test interpretation and reporting. It is helpful to understand the history of urine culture contamination.

2. Origins of Urine Sample Contamination

The belief that urine is sterile above the urethral sphincter is attributed to Pasteur and his studies proposing germ theory in the 1860s (Asscher AW 1966; Roll-HansenN 1979; Brubaker L and Khasriya R 2023). The seminal fact omitted in many contemporary accounts is that Pasteur boiled the urine, vacuum sealed the flasks and observed no growth. Indeed, Pasteur considered urine alone to be an excellent bacterial growth media (Asscher AW 1966). The point of his famous experiment was to demonstrate that the growth he observed in urine open to the environment resulted from microbes and not spontaneous generation from miasma (Roll-HansenN 1979). Later publications by Roberts reported no detectable microbes in fresh urine of healthy subjects using the techniques of the day (e.g., microscopy) (RobertsW 1881). However, all samples left open to the air and at room temperature developed cloudiness and an ammonia odor in two to three days. This was attributed to microbes that could metabolize urea (RobertsW 1881) and later shown to be due to urease expressing facultative anaerobes such as Proteus (Armbruster CE 2017).

The success of Koch’s postulates in identifying single microbes as causes of mortal diseases led to a quantum advance in the diagnosis of infectious disease in the late nineteenth century (Blevins SM 2010). As culture methods evolved for the detection of UTI-associated pathogens, protocols that detected the most common pathogen, Bacterium coli commune (later Escherichia coli), became standard clinical laboratory practice (FriedmannHC 2014). Although multiple publications during the twentieth century reported microbes in the “sterile” urine of healthy individuals without symptoms (HortEC 1914; MarpleCD 1941; PhilpotVB 1956; McFadyen IR 1968; MaskellR 1986; MaskellRA 1988), special methods were necessary to culture these presumably “uncultivatable” microbes (MaskellRA 1988; Khasriya R 2013; Hilt EE 2014; Price TK 2016; Legaria MC 2022), and the dogma remained that urine was sterile in the absence of clinical conditions, such as UTI. Thus, contamination as it is currently defined is thought to arise from extravesicular (outside the bladder) sources and be unrelated to the cause of symptoms or infection; contamination is simply thought of as an artifact of urine sample collection (Valenstein P 1998; Bekeris LG 2008; LaRocco MT 2015). The prevailing view is that urine specimens can easily become contaminated with periurethral, epidermal, perianal, and vaginal flora (LaRocco MT 2015). One report defined contamination as “bacteria that are found in normal vaginal or skin flora and do not cause UTI” (Blake DR 2006).

Skin contaminants are usually identified as Gram-positive diphtheroids (Corynebacteria, club-like), Gram-positive clusters of grapes (Staphylococcus), and Gram-positive cocci (Streptococcus, Micrococcus). Of the 22 different microbes identified among the ten most abundant taxa in four different regions of skin (dry, moist, sebaceous, and feet), 21 are Gram-positive aerobes, microaerophiles or facultative anaerobes (Byrd AL 2018) (Supplemental Table S1). Three are within the Viridians group streptococci (VGS) (Doern CD 2010). Only one is Gram-negative; the anaerobic coccus Veillonella parvula (found only in the dry region sample). Thus, skin contamination would be consistent with Gram-positive commensals.

The vaginal microbiome changes with age and reproductive status (menarche, reproductive age and post-menopausal) (Ravel J 2011; Nunn KL 2016; Saraf VS 2021; Park MG 2023). Consequently, vaginal microbiota can vary with the patient. In general, the healthy vaginal microbiome is predominated by Lactobacilli, although other taxa have been observed (Ravel J 2011, Nunn KL 2016, Saraf VS 2021) (Supplemental Table S2). Vaginal contaminants are usually identified as Gram-positive bacilli and are attributed to commensal flora. These include L. iners, L. crispatus, L. gasseri and L. jensenii but can also include Gardnerella vaginalis (Gram-variable) and Gram-positive anaerobe Atopobium vaginae (now known as Fannyhessea vaginae) (Nouioui I 2018).

The vulvar microbiome has recently been investigated and includes representative taxa from both skin and vagina, including the genera Corynebacterium, Lactobacillus, Staphylococcus, Prevotella, Propionibacterium (Cutibacterium) and Finegoldia (Pagan L 2021). These microbes are Gram-positive diphtheroids, rods, and cocci except for the Gram-negative anaerobe Prevotella. Assessing gastrointestinal contamination including perianal and perineal regions becomes problematic as these microbes are usually Gram-negative facultative anaerobes that can also be uropathogens.

Guidelines for common microbial contaminants in blood culture are available (Palavecino EL 2024) and the Centers for Disease Control maintains a list of microbes that have been detected as commensals in UTI and blood infections (CDC 2022). However, a list of urinary tract microbial contaminants is much more nebulous beyond listing niches (periurethral, epidermal, perianal, and vaginal), or assuming that microbes that are commensals in one niche are commensals in another (Blake DR 2006, LaRocco MT 2015) (Supplementary Tables S1 and S2).

Thus, in current clinical diagnostic practice, if a sample contains mixed flora, it is the number of different microbes (> 2 or more at 104 CFU/ml) that determines contamination and not the actual microbe unless it is a commonly recognized urinary pathogen (Bekeris LG 2008, LaRocco MT 2015, SfeirMM 2018, Mancuso G 2023).

3. Limitations of Diagnostic Standard Urine Culture

Today, diagnosis of UTIs typically relies on patient symptoms and urinalysis. The latter uses urine dipstick testing and, in some cases, the standard urine culture (SUC) method (Chambliss AB 2022; Moreland RB 2024; Werneburg GT 2023). Urine dipstick testing, frequently used to determine further testing, such as urine cultures is reviewed elsewhere (Moreland RB 2024; Chambliss AB 2022). The limitations of SUC have been identified and are starting to impact current diagnostics (Price TK 2017; Dixon M 2020; Wojno KJ and Jafri SMA 2020; Brubaker L and Khasriya R 2023; Gleicher S 2024; Werneburg GT 2024a).

It is now well recognized that SUC under aerobic conditions (Gillespie WA 1960), or even under 5% CO

2, detects a limited number of microbes, almost all facultative anaerobes (Price TK 2016; Price TK 2017; Wojno KJ and Jafri SMA 2020; Brubaker L and Khasriya R 2023; Festa RA 2023). As a result, reports based on SUC, including almost all literature to date, repeatedly document a constellation of the same microbes from the genera

Escherichia,

Pseudomonas,

Klebsiella,

Proteus,

Staphylococcus, and

Enterococcus, with

Escherichia coli by far considered the predominant cause of UTI (

Table 1) (Flores-Mireles AL 2015; Kline KA 2016; Mancuso G 2023; Moreland RB, Gonzalez C, and Putonti C 2023; Werneburg GT 2023; Timm MR 2025). However, these results have been obtained because SUC was designed to detect fast growing, non-fastidious, facultative anaerobes, and thus fails to detect many other microbes. For example, a recent study directly compared SUC results to those of a multiplex polymerase chain reaction (M-PCR) panel for a cohort of 1,132 diagnosed UTI patients. M-PCR detected microbes in 823 of these patients, who also exhibited elevated infection-associated urine biomarkers (Haley E 2024). Of the 10 microbes most detected by M-PCR, only 4 were detected by SUC with 2 of those often not detected (Haley E 2024). Most striking was the failure of SUC to detect 3 of the 5 microbes most detected by M-PCR. These were the genera

Aerococcus and

Actinotignum and the Viridians group Streptococcus (including

S. anginosus,

S. oralis, and

S. gallolyticus subsp.

pasteurianus (formerly known as

Streptococcus pasteurianus). Thus, except for

E. coli, all known uropathogens (“the usual suspects”) represented only 13% or less of UTIs diagnosed with symptoms (Haley E 2024) (

Table 1).

One outstanding issue with SUC has been the diagnosis of sterile pyuria, defined as positive for white blood cells but negative urine cultures in patients that report UTI symptoms (Wise GJ 2015; Horton LE 2018; Cohen JE 2019; Xu R 2024). Yet, a recent report suggests that Actinotignum (which SUC cannot detect but M-PCR diagnostics finds to be quite common) may be an underlying cause of sterile pyuria (Horton LE 2018). Until recently, however, few had questioned the standard diagnostic method as flawed. As this standard method supports the established dogma that UTIs are caused by microbes arising from the gastrointestinal tract and, in females, vulvo-vagina reservoirs, it has, for the most part, gone unchallenged (Timm MR 2025).

4. The Urobiome “Complication”

With the advent of DNA-based techniques (metagenomics) and enhanced culture methods (metaculturomics), the existence of female urethral and bladder microbiota has been confirmed with subtle differences existing between the two (Chen YB 2020; Wang D 2023). Thus, we now know that the typical human urinary tract above the urinary sphincter is not sterile; instead, it contains an indigenous urinary microbiome (also known as the urobiome) (Price TK 2020; Brubaker L 2021b; Du J 2024). We also know that the urobiome can have multiple healthy states (Pearce MM 2014; Price TK 2020; Jayalath S 2022; Joos R 2024). Moreover, many adult males and most adult females have a detectable urobiome without experiencing relevant urinary symptoms. Clearly, this does not mean we all have a UTI (FinucaneTE 2017). Consistent with clinical diagnosis of UTI, in the absence of relevant urinary symptoms, there is no “infection.” Diagnosis of a UTI requires that the patient exhibits at host response, and typically experiences symptoms (including urgency, frequency, urinary incontinence, and/or pain) (Anger J 2019).

Within any microbiome, microbes can be classified into 6 categories: non-pathogen (i.e., those that do not cause disease), pathogen (i.e., those that cause disease), commensal (i.e., those resident within the tissue and benefiting the host), symbiont (i.e., those resident within the tissue and benefiting both the host and the microbe), colonizer (i.e. resident within the tissue and may or may not cause disease), and pathobiont (i.e., resident within the tissue and generally beneficial but disease-causing under certain conditions) (Dey P 2022). The urobiome has the full range of the 6 categories described above, including pathogens and pathobionts (Thomas-White K 2018; Du J 2024). Yet, most human beings do not have a clinical infection (i.e., UTI) even though pathogens or pathobionts are “citizens” of their urobiome community. An informative study enrolled heathy volunteers > 65 years old without urinary symptoms as a comparison group for patients diagnosed with UTIs (Akhlaghpour M 2024). In that study, an M-PCR panel consistently detected the known uropathogens E. coli and Enterococcus faecalis, as well as the emerging uropathogens Aerococcus urinae, Actinotignum schaalli, and members of the Viridians group Streptococcus in healthy volunteers without urinary tract symptoms. In addition, few of these volunteers experienced an increase in infection-related immune markers, a hallmark of infection (Akhlaghpour M 2024). Furthermore, many adult females do not get UTIs. Finally, it is well known that UTIs can resolve spontaneously (Hoffmann T 2020; Barnes HC 2021; Midby JS 2024). This implies that the indigenous urobiome together with both innate and adaptive immune responses can often restore urinary health and resolve infection.

Biomass influences microbial communities. The gastrointestinal tract is the best-known example of a high biomass microbial niche. In contrast, the urobiome has relatively low microbial biomass and thus, in some cases, urine samples yield culture-negative and DNA-based-negative test results (Hilt EE 2014; Pearce MM, Sung VW, and Gai X 2015; Neugent ML 2020). An analogy would be a city block in the Bronx with 35,000 inhabitants versus a high plains plateau in Wyoming with sparse settlements. Within both types of communities, however, interactions occur among the residents. The same is true for ecological microcosms within the human microbiome.

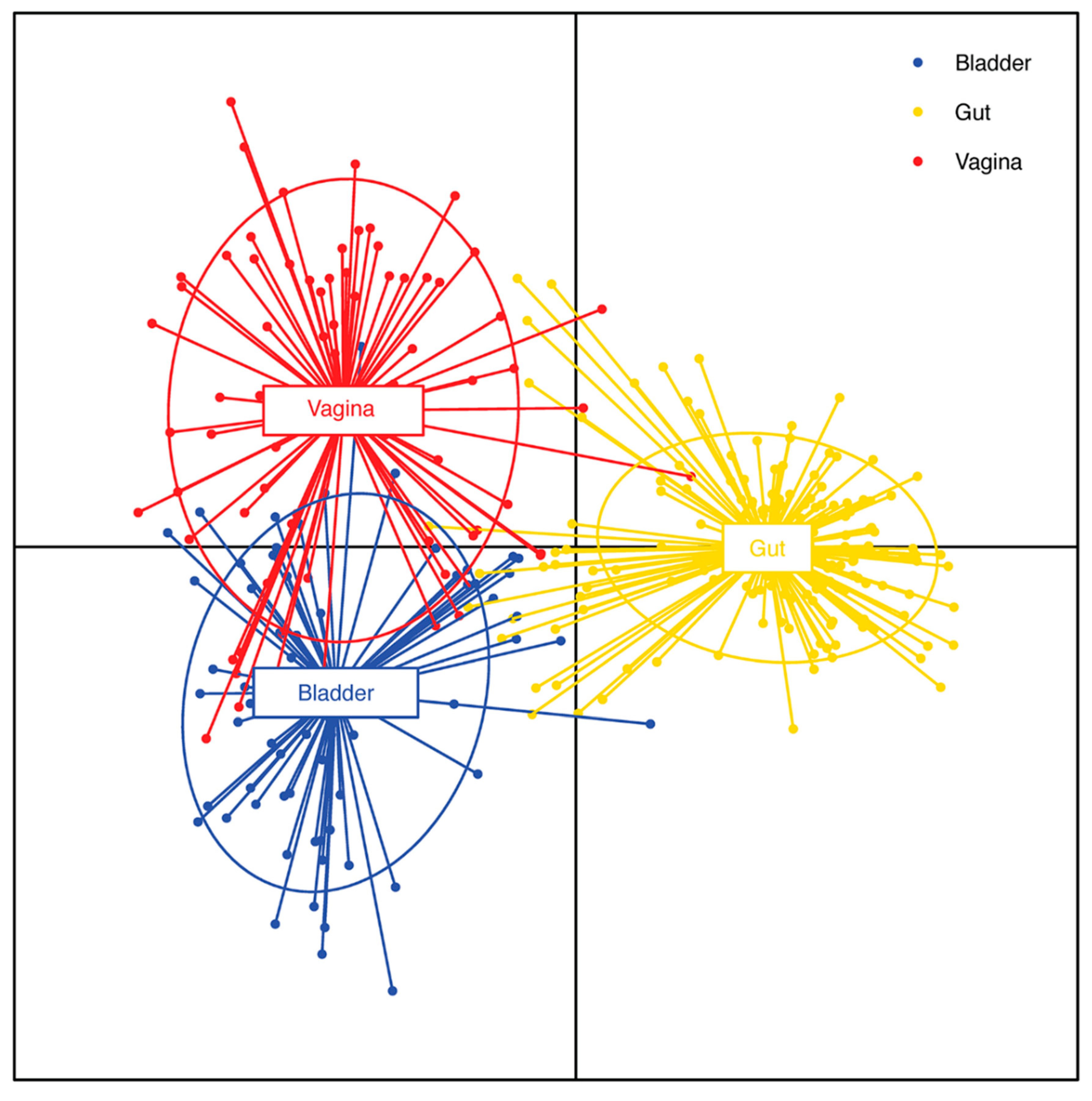

If most contamination arises from periurethral, epidermal, perianal, and vaginal flora as suggested (LaRocco MT 2015), it would be helpful to compare the bladder urobiome to these other niches. A comparison of gastrointestinal, vaginal and bladder microbiomes revealed that while all three niches were distinct from each other, there were similarities between the vagina and bladder microbiomes (Thomas-White K 2018; Du J 2024) (

Figure 1). Furthermore, a recent survey of the skin microbiome lists the top ten taxa from four different niches (Byrd AL 2018). Of the 22 different microbes identified among the ten most abundant taxa in four different regions of skin (dry, moist, sebaceous, and feet), 18 (82%) are also found in urine obtained directly from the bladder by transurethral catheterization (Thomas-White K 2018; Du J 2024) (Supplementary Table S1). Therefore, mere taxonomic identity (via Gram stain, oxygen tolerance, metabolic panel, and/or MALDI-TOF MS) cannot distinguish bladder residents from skin periurethral, perianal, and vaginal residents. To make such a distinction requires genome sequencing and complex bioinformatic analysis that determines whether two isolates are of the same lineage or not.

5. Polymicrobial Infections

The history of polymicrobial infections dates to the late nineteenth century and W.D. Miller, a microbiologist and dentist who had worked in Robert Koch’s lab (Murray JL 2014; SedgleyC 2004). By microscopy and characterization of pus from oral abscesses, he reported that the application of Koch’s postulates was not consistent with cultured microbes isolated from murine models. In fact, Miller obtained a more virulent response from the abscess pus than he did the cultured, recovered microbes. Armed with only culture conditions, a microscope and staining, Miller concluded that uncultivatable microbes worsened the infection (Murray JL 2014). It was not until the availability of DNA sequence-based methods in the late twentieth and early twenty-first century that microbial ecology and polymicrobial infections were confirmed and appreciated in some human niches.

Thus, the concept of polymicrobial UTIs is not new but their existence has been confirmed with many examples reported in the late twentieth century (Siegman-Igra Y 1994; Siegman-Igra Y 1988; Siegman-Igra Y 1993; Siegman-IgraY 1994). Yet, it may be useful to divide the studies on mixed cultures/polymicrobial infections into two groups: before and after the advent of DNA molecular techniques. The former was limited to urine sediment, urine culture, microscopy, Gram staining, and metabolic panels. Urine culture limited to SUC (most often aerobic) identified mostly facultative anaerobes (

Table 1 and

Table 2). Consequently, this literature identified mostly Gram-negative rods as pathogens and excluded most Gram-positive rods and cocci as contaminants (with a few exceptions such as

Enterococcus and coagulase negative

Staphylococcus (CoNS), especially

S. saprophyticus. Early studies on urosepsis and mixed (polymicrobial) cultures from patients revealed that matching cultures from urine and blood of the same microbe suggested that upper urinary tract infection had transitioned into the bloodstream. In one study, 716 bacteremic episodes were observed in 692 patients out of 52,012 admissions over 5 years (Siegman-Igra Y 1994). Of these, 307 episodes in 303 patients were due to UTI. In this group, 198 had at least one microbe that was detected in both blood and urine culture (

Table 2). These 198 urosepsis cases represented 194 patients (96 male, 98 female) with a mean age of 68 years. The most common microbe in monomicrobial infections was

Escherichia coli; however, in polymicrobial infections,

Pseudomonas aeruginosa was most predominant.

P. aeruginosa also was among the microbes associated with fatal outcomes. In an earlier study of polymicrobial bacteremia, of 67 cases across multiple organ systems and causes, 46 percent were diagnosed with UTI (Siegman-Igra Y 1988). Of the 67 cases, 28 died, with 42 percent diagnosed with UTI. While urosepsis is considered rare among the population, in neonates and patients 65 and older, it is a significant morbidity (Peach BC 2016; Akhtar A 2021; Collaborators 2024).

While traditional urinary pathogens are predominantly Gram-negative facultative anaerobes, Gram-positive microbes are also detected in patients diagnosed with UTI, particularly in polymicrobial infections (Kline KA 2016). While usually regarded as commensals, Gram-positive microbes’ pathogenic potential have been questioned (Clarke TM 2010; Kline KA 2016; Leal SM Jr 2016). Yet, Gram-positive CoNS and Enterococcus, as well as emerging urinary pathogens such as Aerococcus, Actinotignum, Gardnerella, and Corynebacteria are found prevalently and abundantly in patients with UTI symptoms (Kline KA 2016; Moreland RB, Gonzalez C, and Putonti C 2023). Microaerophiles and anaerobes also have been observed (Legaria MC 2022; MaskellR 1986) and cultures to rule out these microbes was suggested as part of diagnosis seventy years ago (JawetzE 1953).

With the advent of metaculturomic methods (approaches designed to permit growth of typically uncultivated microbes) and metagenomic approaches (DNA-dependent methods that do not require growth), attempts (e.g., the human microbiome project) have sought to define the microbiota of various human niches, notably skin, respiratory tract, and the gastrointestinal tract, as well as the urogenital and reproductive tracts (Lloyd-Price J 2016; Joos R 2024). Lessons learned from the last two decades of research have taught us that there are multiple healthy states within niches that vary with sex, age and reproductive status (Lloyd-Price J 2016; Joos R 2024). Also, disease states are more complicated than originally anticipated by Koch and his postulated approach (Blevins SM 2010; Murray JL 2014). A recent opinion paper questioned whether the urobiome has any impact on UTI, in part because Koch’s postulates have not been performed to determine whether any of the members of the newly identified urobiome cause disease symptoms (Werneburg GT 2024b). Yet, Koch’s postulates (one organism, one infection, one cause of disease) cannot be applied to polymicrobial infections including UTIs (Ronald LS 2008; Murray JL 2014; Short FL 2014). The request to use Koch’s postulates to validate the role of the urobiome (Werneburg GT 2024b) is further complicated by the currently accepted tools that may no longer apply: a detection system (urine dipsticks, SUC) that misses many uropathogens (Moreland RB 2024) and standards that define polymicrobial infections as contamination (Siegman-Igra Y 1993; Siegman-IgraY 1994; Bekeris LG 2008).

One DNA-dependent method, multiplex PCR (M-PCR), allows quantitative, real-time detection of microbial DNA as long as a primer set is present to detect them (Moreland RB 2024). Using M-PCR, a surprisingly high rate of polymicrobial specimens have been detected in older patients (> 65) with diagnosed UTI symptoms, ranging from 45 to 65 percent depending on simple or complex UTI, sex, and comorbidities (Vollstedt A 2020; Wojno KJ and Jafri SMA 2020; Korman HJ 2023; Wang D 2023; Akhlaghpour M 2024; Haley E 2024). For example, in one study examining the differences of microbes based on catheterized (bladder) urine versus midstream void (entire urinary tract including urogenital areas), more polymicrobial infections were detected in midstream voided compared to catheter-collected samples (64.4% vs 45.7%, p < 0.0001) in females but the opposite in males (35.6% vs 47.0%, p = 0.002 (Wang D 2023). While M-PCR detected microbes that are not detected by SUC, the use of inflammatory markers of infection allowed the distinction of volunteers without relevant clinical symptoms from symptom-diagnosed UTI patients and stratifying those microbes into tiers based on abundance of occurrence (Akhlaghpour M 2024; Haley E 2024).

In the laboratory, specific microbes are studied in isolation using a reductionist approach. In the real world, communities of microbes make up an ecosystem that changes based on the predominating species and interactions between them (Murray JL 2014; Short FL 2014; Jayalath S 2022). These communities interact in synergy with residents by providing nutrients, soluble signaling factors, cell contact through adhesins, or in some cases facilitating antibiotic resistance (Ryan RP 2008; Short FL 2014; Murray JL 2014; Gaston JR 2021). Likewise, some microbes secrete molecules that eliminate their competition such as Pseudomonas (Gaston JR 2021) or kill uropathogens such as commensal Lactobacillus (Abdul-Rahim O, Price TK, and Bugni TS 2021; Johnson JA 2022; Szczerbiec D 2022).

While polymicrobial results in the studies described above were reported as a group, the individual microbes within the subsets of polymicrobial infections were not identified but rather individual microbes were reported by taxa (Vollstedt A 2020; Wojno KJ and Jafri SMA 2020; Korman HJ 2023; Wang D 2023; Akhlaghpour M 2024; Haley E 2024). A reanalysis of the data from these studies could reveal associations of specific microbes that as a group or community are more pathogenic than as single isolates. In an effort to understand microbial ecology of polymicrobial isolates, one study examined 72 bacteria isolates collected from 23 patients diagnosed with polymicrobial UTI (de Vos MGJ 2017). An ecological network analysis was developed, finding that most interactions clustered based on evolutionary relatedness. Eight complete communities of four different microbes were found, four of which were predicted to be stable and four not stable (de Vos MGJ 2017). The isolates used for this study were originally collected using standard culture techniques (Croxall G 2011), which may explain the predominance of classical uropathogens. Expanding and extending this concept, another study examined pathogens and bladder commensal isolates grown under urine-like conditions and the effects different microbes had on the community (Zandbergen LE 2021). Artificial urine media conditioned by commensals had effects on growth of uropathogens and vice versa. This early attempt at gaining insights into the complexities of urobiome ecology shows that while a microbe in isolation may have certain growth characteristics, the community - through direct interaction, secretion of signaling molecules or metabolites, or interaction with the host - may exhibit a different response than a single microbe in monoculture (Heidrich V 2022; Short FL 2014; Murray JL 2014).

6. Future Directions: A Call to Action

To advance diagnosis, we suggest the following:

1. Reexamine the standards for urine collection/culture contamination to ensure accurate sampling taking into consideration the new knowledge concerning the urobiome. A recent scoping review highlights the issues, especially the lack of consensus among guidelines for a urine culture thresholds for UTI and the reliance on dated and sparse evidence for current standards (Hilt EE 2023). To achieve accuracy, we must recognize that urine must be processed immediately or be stored under conditions that do not permit growth of microbes in the sample (LaRocco MT 2015).

2. The concept of contamination must be reevaluated in the context of the new knowledge that the urobiome exists. Urine is not sterile above the urethral sphincter and the existence of communities of commensal, non-pathogenic microbes with known and potential uropathogens (pathobionts) should be acknowledged. While dysbiosis is generally a concept foreign to the UTI literature, it needs to be recognized, and diagnostics updated to reflect the current science (Price TK 2017; Jayalath S 2022; Simoni A 2024). Koch’s postulates are invalid in polymicrobial systems (Murray JL 2014; Short FL 2014) but persist as a consequence of the dogma that single microbes are causative of disease (Blevins SM 2010; Werneburg GT 2024b).

The danger of dismissing genera that are considered routine contaminants, such as members of the genus Corynebacterium, can lead to dismissing pathogens like C. urealyticium, which is nitrate negative by urine dipstick and grows slowly under SUC conditions. While PCR testing is much more rapid (Dixon M 2020; Gleicher S 2024; Zering J 2024), without some reference to host immune response (infection), the practicing clinician is left with 10-20 names on a page with little clue what to do next (Zering J 2024; Xu R 2021). One test correlates an M-PCR panel of 30 microbes with biomarkers of inflammation (Akhlaghpour M 2024; Haley E 2024). While this is one study with older patients, it opens the opportunity to examining other age groups, males and females, pregnant and non-pregnant. It is likely the differences encountered will require tailored treatment depending on the type of patient.

3. Recognize the shortcomings of SUC. There is now sufficient data in the literature to adjudicate the accuracy of this method. It should be examined, weighing its strengths and acknowledging its weaknesses (Price TK 2017; Wojno KJ and Jafri SMA 2020; Xu R 2021; Festa RA 2023; Brubaker L and Khasriya R 2023; Gleicher S 2024). Besides its ability to detect only a limited group of facultative anaerobes, time is also a consideration as re-sampling and re-culturing requires time that may allow an infection to progress.

4. Recognize the presence and importance of polymicrobial UTI. There is literature to support that these infections are more prevalent than previously believed and misdiagnosis as contamination should be considered and evaluated. Ultimately, clinical diagnostic pathways might be modified to diagnose these infections before they can progress to upper tract UTI and potentially urosepsis (Siegman-Igra Y 1994; Peach BC 2016; Akhtar A 2021).

5. Take a lesson from other organ systems and diseases (Murray JL 2014; Short FL 2014), and ask how diagnostic tools can be improved and new tools developed or implemented to characterize the bacterial communities in polymicrobial infections/mixed cultures. One way to accomplish this would be to reanalyze data from polymicrobial samples to determine the individuals in the communities and if any groups of microbes were more common than others (Vollstedt A 2020; Wang D 2023; Akhlaghpour M 2024; Haley E 2024).

6. Recognize the importance of redefining contamination, acknowledging polymicrobial infection, and developing accurate and rapid diagnostics that not only detect microbes but determine if they are involved in a host immune response is critical for antibiotic stewardship. The increase in antibiotic resistance and future predictions are sobering (Collaborators 2024). Proper and appropriate use of antibiotics to treat UTI not only affects the health of patients but preserves critical antibiotics for those who need them (Simoni A 2024).

7. Conclusions

In this review, we have presented the current diagnostic state of urine contamination and discussed the limitations of current diagnostic techniques, such as SUC. We have reviewed the evidence for polymicrobial UTI, raising doubt concerning the appropriateness of applying Koch’s postulates and recognizing the consequences of potential missed diagnosis. The challenges for clinical microbiologists, clinicians and research scientists are to question the current dogmas, address polymicrobial infections, and work to define the microbial ecology of the urinary tract. The future is bright as multidisciplinary collaboration offers cross-pollination of efforts to improve patient care and quality of life.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, AJW, RBM. writing—original draft preparation, AJW, RBM, writing—review and editing, AJW, LB, RBM. supervision, AJW. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sector.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank Amanda Harrington, PhD, D(ABMM), for thought-provoking and helpful discussions. We also thank Christopher Beger, Gail Hendler, and the staff of the Loyola Health Sciences Library, Loyola University Chicago, for assistance with interlibrary loans and obtaining articles and reviews.

Conflicts of Interest

AJW declares membership on the Scientific Advisory Boards of Astek, Carrillo, Pathnostics, and Urobiome Therapeutics. LB declares editorial stipends from UpToDate and JAMA. RBM has no conflicts.

References

- Abdul-Rahim O, Wu Q, Pistone G Price TK, Diebel K, and Wolfe AJ Bugni TS. 'Phenyl-Lactic Acid Is an Active Ingredient in Bactericidal Supernatants of Lactobacillus crispatus'. J Bacteriol, 2021, 203, e0036021.

- Akhlaghpour M, Haley E Parnell L, Luke N, Mathur M, Festa RA, Percaccio M, Magallon J, Remedios-Chan M, Rosas A, Wang J, Jiang Y, Anderson L, Baunoch D. 'Urine biomarkers individually and as a consensus model show high sensitivity and specificity for detecting UTIs'. BMC Infect Dis 2024, 24, 153.

- Akhtar A, Ahmad Hassali MA, Zainal H, Ali I, Khan AH. 'A Cross-Sectional Assessment of Urinary Tract Infections Among Geriatric Patients: Prevalence, Medication Regimen Complexity, and Factors Associated With Treatment Outcomes', Front Public Health 2021, 9, 657199. [CrossRef]

- Anger, J.T.; Lee, U.; Ackerman, A.L.; Chou, R.; Chughtai, B.; Clemens, J.Q.; Hickling, D.; Kapoor, A.; Kenton, K.S.; Kaufman, M.R.; et al. Recurrent Uncomplicated Urinary Tract Infections in Women: AUA/CUA/SUFU Guideline. J. Urol. 2019, 202, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armbruster, C.E.; Smith, S.N.; Johnson, A.O.; DeOrnellas, V.; Eaton, K.A.; Yep, A.; Mody, L.; Wu, W.; Mobley, H.L.T. The Pathogenic Potential of Proteus mirabilis Is Enhanced by Other Uropathogens during Polymicrobial Urinary Tract Infection. Infect. Immun. 2017, 85, e00808–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asscher, A.; Sussman, M.; Waters, W.; Davis, R.; Chick, S. URINE AS A MEDIUM FOR BACTERIAL GROWTH. Lancet 1966, 288, 1037–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, H.C.; Wolff, B.; Abdul-Rahim, O.; Harrington, A.; Hilt, E.E.; Price, T.K.; Halverson, T.; Hochstedler, B.R.; Pham, T.; Acevedo-Alvarez, M.; et al. A Randomized Clinical Trial of Standard versus Expanded Cultures to Diagnose Urinary Tract Infections in Women. J. Urol. 2021, 206, 1212–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekeris LG, Jones BA, Walsh MK, Wagar EA. 'Urine culture contamination: a College of American Pathologists Q-Probes study of 127 laboratories', Arch Pathol Lab Medicine 2008, 132, 913–17. [CrossRef]

- Blake, D.R.; Doherty, L. Effect of Perineal Cleansing on Contamination Rate of Mid-stream Urine Culture. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2006, 19, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blevins SM, Bronze MS. 'Robert Koch and the 'golden age' of bacteriology', Int J Infect Dis 2010, 14, e744–51.

- Brubaker L, Chai TC, Horsley H,, and Moreland RB Khasriya R, Wolfe AJ. 'Tarnished gold—the “standard” urine culture: reassessing the characteristics of a criterion standard for detecting urinary microbes'. Frontiers in Urology 2023, 3.

- Brubaker, L.; Gourdine, J.-P.F.; Siddiqui, N.Y.; Holland, A.; Halverson, T.; Limeria, R.; Pride, D.; Ackerman, L.; Forster, C.S.; Jacobs, K.M.; et al. Forming Consensus To Advance Urobiome Research. mSystems 2021, 6, e0137120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brubaker L, Putonti C, Dong Q, Wolfe AJ. 'The Human Urobiome'. Mamm Genome 2021, 32, 232–238.

- Byrd, A.L.; Belkaid, Y.; Segre, J.A. The human skin microbiome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambliss, A.B.; Van, T.T. Revisiting approaches to and considerations for urinalysis and urine culture reflexive testing. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2021, 59, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.B.; Hochstedler, B.; Pham, T.T.; Alvarez, M.A.; Mueller, E.R.; Wolfe, A.J. The Urethral Microbiota: A Missing Link in the Female Urinary Microbiota. J. Urol. 2020, 204, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, T.M.; Citron, D.M.; Towfigh, S. The Conundrum of the Gram-Positive Rod: Are We Missing Important Pathogens in Complicated Skin and Soft-Tissue Infections? A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Surg. Infect. 2010, 11, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.E.; Yura, E.M.; Chen, L.; Schaeffer, A.J. Predictive Utility of Prior Negative Urine Cultures in Women with Suspected Recurrent Uncomplicated Urinary Tract Infections. J. Urol. 2019, 202, 979–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collaborators, GBD 2021 Antimicrobial Resistance. 2024. 'Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance 1990–2021: a systematic analysis with forecasts to 2050', Lancet, Online , 2024. 16 September.

- Croxall, G.; Weston, V.; Joseph, S.; Manning, G.; Cheetham, P.; McNally, A. Increased human pathogenic potential of Escherichia coli from polymicrobial urinary tract infections in comparison to isolates from monomicrobial culture samples. J. Med Microbiol. 2011, 60, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vos MGJ, Zagorski M, McNally A, Bollenbach T. 'Interaction networks, ecological stability, and collective antibiotic tolerance in polymicrobial infections', Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017, 114, 10666–71. [CrossRef]

- Dey, P.; Ray Chaudhuri, S. The opportunistic nature of gut commensal microbiota. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2022, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon, M.; Sha, S.; Stefil, M.; McDonald, M. Is it Time to Say Goodbye to Culture and Sensitivity? The Case for Culture-independent Urology. Urology 2019, 136, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doern CD, Burnham CA. 'It's not easy being green: the viridans group streptococci, with a focus on pediatric clinical manifestations', J Clin Microbiol. 2010, 48, 3829–35. [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Khemmani, M.; Halverson, T.; Ene, A.; Limeira, R.; Tinawi, L.; Hochstedler-Kramer, B.R.; Noronha, M.F.; Putonti, C.; Wolfe, A.J. Cataloging the phylogenetic diversity of human bladder bacterial isolates. Genome Biol. 2024, 25, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festa, R.A.; Luke, N.; Mathur, M.; Parnell, L.; Wang, D.; Zhao, X.; Magallon, J.; Remedios-Chan, M.; Nguyen, J.; Cho, T.; et al. A test combining multiplex-PCR with pooled antibiotic susceptibility testing has high correlation with expanded urine culture for detection of live bacteria in urine samples of suspected UTI patients. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2023, 107, 116015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FinucaneTE. ' "Urinary Tract Infection"-Requiem for a Heavyweight.'. J American Geriatr Soc. 2017, 65, 1650–55. [CrossRef]

- Flores-Mireles AL, Walker JN, Caparon M, Hultgren SJ. 'Urinary tract infections: epidemiology, mechanisms of infection and treatment options', Nat Rev Microbiol. 2015, 13, 269–84. [CrossRef]

- FriedmannHC. 'Escherich and Escherichia'. EcoSal Plus 2014, 6.

- Gaston JR, Johnson AO, Bair KL, White AN, Armbruster CE. 2021. 'Polymicrobial interactions in the urinary tract: is the enemy of my enemy my friend?', Infect Immun.

- Gillespie, W.A.; Linton, K.B.; Miller, A.; Slade, N. The diagnosis, epidemiology and control of urinary infection in urology and gynaecology. J. Clin. Pathol. 1960, 13, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleicher, S.; Karram, M.; Wein, A.J.; Dmochowski, R.R. Recurrent and complicated urinary tract infections in women: Utility of advanced testing to enhance care. Neurourol. Urodynamics 2023, 43, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haley, E.; Luke, N.; Mathur, M.; Festa, R.; Wang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Anderson, L.; Baunoch, D. The Prevalence and Association of Different Uropathogens Detected by M-PCR with Infection-Associated Urine Biomarkers in Urinary Tract Infections. Res. Rep. Urol. 2024, 16, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, M.A.; Valentine-King, M.; Zoorob, R.; Schlueter, M.; Matas, J.L.; Willis, S.E.; Danek, L.C.; Muldrew, K.L.; Zare, M.; Hudson, F.; et al. Prevalence and predictors of urine culture contamination in primary care: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2022, 134, 104325–104325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidrich, V.; Inoue, L.T.; Asprino, P.F.; Bettoni, F.; Mariotti, A.C.H.; Bastos, D.A.; Jardim, D.L.F.; Arap, M.A.; Camargo, A.A. Choice of 16S Ribosomal RNA Primers Impacts Male Urinary Microbiota Profiling. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 862338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilt, E.E.; McKinley, K.; Pearce, M.M.; Rosenfeld, A.B.; Zilliox, M.J.; Mueller, E.R.; Brubaker, L.; Gai, X.; Wolfe, A.J.; Schreckenberger, P.C. Urine Is Not Sterile: Use of Enhanced Urine Culture Techniques To Detect Resident Bacterial Flora in the Adult Female Bladder. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2014, 52, 871–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E Hilt, E.; Parnell, L.K.; Wang, D.; E Stapleton, A.; Lukacz, E.S. Microbial Threshold Guidelines for UTI Diagnosis: A Scoping Systematic Review. Pathol. Lab. Med. Int. 2023, 15, 43–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, T.; Peiris, R.; Del Mar, C.; Cleo, G.; Glasziou, P. Natural history of uncomplicated urinary tract infection without antibiotics: a systematic review. Br. J. Gen. Pr. 2020, 70, e714–e722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HortEC. 'The Sterility of Normal Urine in Man', J Hyg (Lond) 1914, 14, 509–16.

- Horton LE, Mehta SR, Aganovic L, Fierer J. 'Actinotignum schaalii Infection: A Clandestine Cause of Sterile Pyuria?', Open Forum Infect Diseases 2018, 5, ofy015. [CrossRef]

- JawetzE. 'Urinary tract infections; problems in medical management', California Med. 1953, 79, 99–102.

- Jayalath, S.; Magana-Arachchi, D. Dysbiosis of the Human Urinary Microbiome and its Association to Diseases Affecting the Urinary System. Indian J. Microbiol. 2021, 62, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.A.; Delaney, L.F.; Ojha, V.; Rudraraju, M.; Hintze, K.R.; Siddiqui, N.Y.; Sysoeva, T.A. Commensal Urinary Lactobacilli Inhibit Major Uropathogens In Vitro With Heterogeneity at Species and Strain Level. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 870603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joos R, Boucher K, Lavelle A, Arumugam M, Blaser MJ, Claesson MJ, Clarke G, Cotter PD, De Sordi L, Dominguez-Bello MG, Dutilh BE, Ehrlich SD, Ghosh TS, Hill C, Junot C, Lahti L, Lawley TD, Licht TR, Maguin E, Makhalanyane TP, Marchesi JR, Matthijnssens J, Raes J, Ravel J, Salonen A, Scanlan PD, Shkoporov A, Stanton C, Thiele I, Tolstoy I, Walter J, Yang B, Yutin N, Zhernakova A, Zwart H; Human Microbiome Action Consortium; Doré J, Ross RP. 2024.

- Khasriya, R.; Sathiananthamoorthy, S.; Ismail, S.; Kelsey, M.; Wilson, M.; Rohn, J.L.; Malone-Lee, J. Spectrum of Bacterial Colonization Associated with Urothelial Cells from Patients with Chronic Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2013, 51, 2054–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kline KA, Lewis AL. 'Gram-Positive Uropathogens, Polymicrobial Urinary Tract Infection, and the Emerging Microbiota of the Urinary Tract', Microbiol Spect 2016, 4, 101128.

- Korman HJ, Baunoch D, Luke N, Wang D, Zhao X, Levin M, Wenzler DL, Mathur M. 'A Diagnostic Test Combining Molecular Testing with Phenotypic Pooled Antibiotic Susceptibility Improved the Clinical Outcomes of Patients with Non-E. coli or Polymicrobial Complicated Urinary Tract Infections', Res Rep Urol. 2023, 15, 141–47.

- LaRocco, M.T.; Franek, J.; Leibach, E.K.; Weissfeld, A.S.; Kraft, C.S.; Sautter, R.L.; Baselski, V.; Rodahl, D.; Peterson, E.J.; Cornish, N.E. Effectiveness of Preanalytic Practices on Contamination and Diagnostic Accuracy of Urine Cultures: a Laboratory Medicine Best Practices Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2016, 29, 105–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, S.M.; Jones, M.; Gilligan, P.H. Clinical Significance of Commensal Gram-Positive Rods Routinely Isolated from Patient Samples. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2016, 54, 2928–2936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legaria MC, Barberis C, Famiglietti A, De Gregorio S, Stecher D, Rodriguez CH, Vay CA. 'Urinary tract infections caused by anaerobic bacteria. Utility of anaerobic urine culture', Anaerobe 2022, 78, 102636.

- Lloyd-Price, J.; Abu-Ali, G.; Huttenhower, C. The healthy human microbiome. Genome Med. 2016, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancuso, G.; Midiri, A.; Gerace, E.; Marra, M.; Zummo, S.; Biondo, C. Urinary Tract Infections: The Current Scenario and Future Prospects. Pathogens 2023, 12, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MarpleCD. 'The frequency and character of urinary tract infections in a group of unselected women', Annals Internal Medicine 1941, 14, 2220–39. [CrossRef]

- MaskellR. 1986. Are fastidious organisms an important cause for dysuria and frequency- the case for (John Wiley and Sons: London, UK).

- MaskellRA. 1988. Pathogenesis, consequences and natural history of urinary tract infection (Edward Arnold: London, UK).

- Mcfadyen, I.; Eykyn, S. SUPRAPUBIC ASPIRATION OF URINE IN PREGNANCY. Lancet 1968, 291, 1112–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Midby, J.S.; Miesner, A.R. Delayed and Non-Antibiotic Therapy for Urinary Tract Infections: A Literature Review. J. Pharm. Pr. 2022, 37, 212–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreland, R.B.; Brubaker, L.; Tinawi, L.; Wolfe, A.J. Rapid and accurate testing for urinary tract infection: new clothes for the emperor. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2024, e0012924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreland RB, Choi BI, Geaman W,, Hochstedler-Kramer BR Gonzalez C, John J, Kaindl J, Kesav N, Lamichhane J, Lucio L, Saxena M, Sharma A, Tinawi L, Vanek ME,, and Brubaker L Putonti C, Wolfe AJ. 2023. 'Beyond the usual suspects: emerging uropathogens in the microbiome age', Front Urology, 3.

- Murray, J.L.; Connell, J.L.; Stacy, A.; Turner, K.H.; Whiteley, M. Mechanisms of synergy in polymicrobial infections. J. Microbiol. 2014, 52, 188–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neugent, M.L.; Hulyalkar, N.V.; Nguyen, V.H.; Zimmern, P.E.; De Nisco, N.J. Advances in Understanding the Human Urinary Microbiome and Its Potential Role in Urinary Tract Infection. mBio 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouioui, I.; Carro, L.; García-López, M.; Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Woyke, T.; Kyrpides, N.C.; Pukall, R.; Klenk, H.-P.; Goodfellow, M.; Göker, M. Genome-Based Taxonomic Classification of the Phylum Actinobacteria. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunn, K.L.; Forney, L.J. Unraveling the Dynamics of the Human Vaginal Microbiome. 2016, 89, 331–337.

- O’leary, B.D.; Armstrong, F.M.; Byrne, S.; Talento, A.F.; O’coigligh, S. The prevalence of positive urine dipstick testing and urine culture in the asymptomatic pregnant woman: A cross-sectional study. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2020, 253, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.G.; Cho, S.; Oh, M.M. Menopausal Changes in the Microbiome—A Review Focused on the Genitourinary Microbiome. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peach BC, Garvan GJ, Garvan CS, Cimiotti JP. 2016. 'Risk Factors for Urosepsis in Older Adults: A Systematic Review', Gerontol Geriatr Med, 2: 2333721416638980.

- Pearce, M.M.; Hilt, E.E.; Rosenfeld, A.B.; Zilliox, M.J.; Thomas-White, K.; Fok, C.; Kliethermes, S.; Schreckenberger, P.C.; Brubaker, L.; Gai, X.; et al. The Female Urinary Microbiome: a Comparison of Women with and without Urgency Urinary Incontinence. mBio 2014, 5, e01283–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce MM, Zilliox MJ, Rosenfeld AB, Thomas-White KJ, Richter HE, Nager, CW, Visco AG, Nygaard IE, Barber MD, Schaffer J, Moalli P,, Smith Al Sung VW, Rogers R, Nolen TL, Wallace D, Meikle SF,, and Wolfe AJ Gai X, Brubaker L, Pelvic Floor Disorders, Network. 'The female urinary microbiome in urgency urinary incontinence', Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2015, 213, 347 e1–11.

- PhilpotVB. 'The bacterial flora of urine specimens from normal adults.', J Urol. 1956, 75, 562–68.

- Pohl, H.G.; Groah, S.L.; Pérez-Losada, M.; Ljungberg, I.; Sprague, B.M.; Chandal, N.; Caldovic, L.; Hsieh, M. The Urine Microbiome of Healthy Men and Women Differs by Urine Collection Method. Int. Neurourol. J. 2020, 24, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price TK, Dune T, Hilt EE, Thomas-White KJ, Kliethermes S, Brincat C, Brubaker L, Wolfe AJ, Mueller ER, Schreckenberger PC. 'The Clinical Urine Culture: Enhanced Techniques Improve Detection of Clinically Relevant Microorganisms', J Clin Microbiol. 2016, 54, 1216–22. [CrossRef]

- Price, T.K.; Hilt, E.E.; Dune, T.J.; Mueller, E.R.; Wolfe, A.J.; Brubaker, L. Urine trouble: should we think differently about UTI? Int. Urogynecology J. 2017, 29, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, T.K.; Lin, H.; Gao, X.; Thomas-White, K.J.; Hilt, E.E.; Mueller, E.R.; Wolfe, A.J.; Dong, Q.; Brubaker, L. Bladder bacterial diversity differs in continent and incontinent women: a cross-sectional study. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 223, 729.e1–729.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravel, J.; Gajer, P.; Abdo, Z.; Schneider, G.M.; Koenig, S.S.K.; McCulle, S.L.; Karlebach, S.; Gorle, R.; Russell, J.; Tacket, C.O.; et al. Vaginal microbiome of reproductive-age women. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108 (Suppl. S1), 4680–4687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RobertsW. 'On the occurrence of micro-organisms in fresh urine', Br Med J, 1881, 2: 623-25.

- Roll-HansenN. 'Experimental method and spontaneous generation: the controversy between Pasteur and Pouchet 1859–64', J Hist Med Allied Sci. 1979, 34, 273–92.

- Ronald, L.S.; Yakovenko, O.; Yazvenko, N.; Chattopadhyay, S.; Aprikian, P.; Thomas, W.E.; Sokurenko, E.V. Adaptive mutations in the signal peptide of the type 1 fimbrial adhesin of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2008, 105, 10937–10942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.P.; Dow, J.M. Diffusible signals and interspecies communication in bacteria. Microbiology 2008, 154, 1845–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraf, V.S.; Sheikh, S.A.; Ahmad, A.; Gillevet, P.M.; Bokhari, H.; Javed, S. Vaginal microbiome: normalcy vs dysbiosis. Arch. Microbiol. 2021, 203, 3793–3802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SedgleyC. 'Root canal irrigation--a historical perspective', J Hist Dent. 2004, 52, 61–65.

- Sfeir, M.; Hooton, T. Practices of clinical microbiology laboratories in reporting voided urine culture results. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2018, 24, 669–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, F.L.; Murdoch, S.L.; Ryan, R.P. Polybacterial human disease: the ills of social networking. Trends Microbiol. 2014, 22, 508–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegman-Igra Y, Kulka T, Schwartz D, Konforti N. 'The significance of polymicrobial growth in urine: contamination or true infection', Scand J Infect Dis. 1993, 25, 85–91. [CrossRef]

- Polymicrobial and monomicrobial bacteraemic urinary tract infection', J Hosp Infect, 28: 49-56.

- Siegman-Igra, Y.; Schwartz, D.; Konforti, N. Polymicrobial bacteremia. Med Microbiol. Immunol. 1988, 177, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegman-IgraY. 'The significance of urine culture with mixed flora', Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens, 1994, 3, 656–59.

- Simoni, A.; Schwartz, L.; Junquera, G.Y.; Ching, C.B.; Spencer, J.D. Current and emerging strategies to curb antibiotic-resistant urinary tract infections. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2024, 21, 707–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczerbiec D, Piechocka J, Głowacki R, Torzewska A. 'Organic Acids Secreted by Lactobacillus spp. Isolated from Urine and Their Antimicrobial Activity against Uropathogenic Proteus mirabilis.', Molecules 2022, 27, 5557. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas-White, K.; Forster, S.C.; Kumar, N.; Van Kuiken, M.; Putonti, C.; Stares, M.D.; Hilt, E.E.; Price, T.K.; Wolfe, A.J.; Lawley, T.D. Culturing of female bladder bacteria reveals an interconnected urogenital microbiota. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timm MR, Russell SK, Hultgren SJ. 'Urinary tract infections: pathogenesis, host susceptibility and emerging therapeutics', Nat Rev Microbiol 2025, 23, 72–86. [CrossRef]

- Valenstein, P.; Meier, F. Urine culture contamination: a College of American Pathologists Q-Probes study of contaminated urine cultures in 906 institutions. . 1998, 122, 123–9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vollstedt, A.; Baunoch, D.; Wolfe, A.; Luke, N.; Wojno, K.J.; Cline, K.; Belkoff, L.; Milbank, A.; Sherman, N.; Haverkorn, R.; et al. Bacterial Interactions as Detected by Pooled Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing (P-AST) in Polymicrobial Urine Specimens. 2020, 1. 1.

- Wang D, Haley E, Luke N, Festa RA, Zhao X Anderson LA, Allison LL, Stebbins KL, Diaz MJ, Baunoch D. 'Emerging and Fastidious Uropathogens Were Detected by M-PCR with Similar Prevalence and Cell Density in Catheter and Midstream Voided Urine Indicating the Importance of These Microbes in Causing UTIs', Infect Drug Resist 2023, 16, 7775–95.

- Werneburg, G.T.; Hsieh, M.H. Clinical Microbiome Testing for Urology. Urol. Clin. North Am. 2024, 51, 493–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werneburg, G.T.; Lewis, K.C.; Vasavada, S.P.; Wood, H.M.; Goldman, H.B.; Shoskes, D.A.; Li, I.; Rhoads, D.D. Urinalysis Exhibits Excellent Predictive Capacity for the Absence of Urinary Tract Infection. Urology 2023, 175, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werneburg, G.T.; Southgate, J. Urinary Microbiome Research Has Not Established a Conclusive Influence: Revisiting Koch’s Postulates. Eur. Urol. Focus 2024, 10, 686–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whelan, P.S.; Nelson, A.; Kim, C.J.; Tabib, C.; Preminger, G.M.; Turner, N.A.; Lipkin, M.; Advani, S.D. Investigating risk factors for urine culture contamination in outpatient clinics: A new avenue for diagnostic stewardship. Antimicrob. Steward. Heal. Epidemiology 2022, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise GJ, Schlegel PN. 'Sterile pyuria', N Engl J Med. 2015, 372, 1048–54.

- Wojno KJ, Baunoch D, Luke N Opel M, Korman H, Kelly C,, and Keating P Jafri SMA, Hazelto D, Hindu S, Makhloouf B, Wenzler D, Sabry, M, Burks F, Penaranda M, Smith DE, Korman, A, Sirls L. 'Multiplex PCR Based Urinary Tract Infection (UTI) Analysis Compared to Traditional Urine Culture in Identifying Significant Pathogens in Symptomatic Patients', Urol. 2020, 136, 119–26.

- Xu, R.; Deebel, N.; Casals, R.; Dutta, R.; Mirzazadeh, M. A New Gold Rush: A Review of Current and Developing Diagnostic Tools for Urinary Tract Infections. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu R, Ritts R, Badlani G. 'Unresolved Pyuria', Current Bladder Dysfunction Rep 2024, 1–9.

- Zandbergen, L.E.; Halverson, T.; Brons, J.K.; Wolfe, A.J.; de Vos, M.G.J. The Good and the Bad: Ecological Interaction Measurements Between the Urinary Microbiota and Uropathogens. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 659450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zering, J.; Stohs, E.J. Urine polymerase chain reaction tests: stewardship helper or hinderance? Antimicrob. Steward. Heal. Epidemiology 2024, 4, e77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).