The oral Candida carriage in a group of Sri Lankan male oral fibroepithelial

polyps patients with oral risk habits

1. Introduction

Fibroepithelial polyps are inflammatory hyperplastic lesions characterized by para-keratinized stratified squamous epithelium. They develop in response to chronic irritation and display arcading patterns with a mixed infiltrate of inflammatory cells, predominantly lymphocytes, along with plasma cells. In the oral cavity, these lesions typically appear on the buccal mucosa and the tongue [

1,

2]. The most frequent causes of these lesions include repeated lip or cheek biting, irregular denture borders, overhanging dental restorations, calculus buildup, sharp tooth edges, and other oral prostheses. Fibroepithelial polyps are often found in individuals between their second and fourth decades [

3]. Fibroepithelial polyps are usually asymptomatic, but they can cause difficulties with speech and chewing if they grow large. Typically, these polyps present as painless swellings, which may be either sessile (directly attached) or pedunculated (attached by a stalk). The treatment for fibroepithelial polyps is surgical excision, after which the tissue is sent for histopathological diagnosis [

1,

2,

3]. It is important to note that patients with these polyps often engage in risky behaviors, such as chewing betel quid, which may lead to mucosal irritation and potentially increase the likelihood of developing these polyps [

1,

3]. Additionally, substances like smokeless tobacco, areca nut, smoked tobacco, and alcohol contain irritants and carcinogens that can cause chronic inflammation of the oral epithelium [

4,

5,

6,

7].

Candida is a normal resident of the oral cavity and is considered a potential member of the oral mycobiome meta-community. The species of

Candida are among the most common commensal fungi that colonize the oral mucosa, with carriage rates varying between 3% to 70% in healthy individuals [

4]. When the immune system is compromised, Candida species can cause oral candidiasis in individuals with predisposing factors. As a result, the carriage rate of Candida tends to increase during middle and later life. In the oral cavity, an overgrowth of

Candida can lead to discomfort, pain, and an altered sense of taste. If the infection spreads to the esophagus, it can cause dysphagia, making it difficult to eat and swallow, ultimately resulting in poor nutrition [

8,

9]. In immuno-compromised patients, the infection can potentially spread through the bloodstream or upper gastrointestinal tract, leading to severe infections that increase morbidity and mortality. The mortality rate from systemic candidiasis can be as high as 79% [

9]. This study aimed to investigate

Candida carriage among a group of Sri Lankan male patients with oral fibroepithelial polyps who engage in oral risk behaviors.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

Ethical approval for the study was received from the Faculty Research Committee, Faculty of Dental Sciences, University of Peradeniya, Sri Lanka (FRC/FDS/UOP/E/2014/32) and Griffith University Human Research Ethics Committee, Australia (DOH/18/14/HREC). Written informed consent was obtained from each participant as described previously. [

2,

8].

2.2. Study Design, Sample Size Calculation, Exclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The main sample consisted of 134 cases of oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC), alongside a 134 control group comprised of individuals with benign mucosal lesions. The sample size was calculated using the formula outlined by Kelsey et al. [

11]. The study included Sinhala males 40 years and older, histologically confirmed OSCC originating from the buccal mucosa or tongue. Participants were required to have oral risk habits and must not have been on antibiotics for two months before data collection. Individuals who were non-Sinhalese, younger than 40 years, did not have at least one oral risk habit, or were on antibiotics within the past two months were excluded from this study.

2.2. Data Collection, Clinical Oral Examination and Statistical Analysis

Data collection using an interviewer-administered questionnaire designed to gather information on socio-demographics and risky behaviors, including smokeless tobacco, consumption of areca nut, betel quid chewing, tobacco smoking, and alcohol consumption for each individual. Clinical oral examination by a dental public health specialist thoroughly inspected the oral mucosa for any growths, ulcerations, or white patches. The number of missing teeth was recorded, and oral hygiene status was assessed using the Simplified Oral Hygiene Index. Additionally, periodontal health was evaluated by measuring bleeding on probing (BOP), periodontal pocket depth (PPD), and clinical attachment loss (CAL) at four sites for anterior teeth and six sites for posterior teeth, as previously explained [

6,

7]. Data entry and analysis were performed using SPSS-21, a statistical software package. The statistical significance of qualitative and quantitative data was determined using descriptive statistics for percentages, frequencies, means, and standard deviations [

6,

7].

2.3. Sampling Technique, Tissues Selection and DNA Extraction

Non-probability consecutive sampling was conducted to obtain freshly excised, clinically diagnosed tissue samples (FEPs). A new sterile surgical blade was used for each sample to ensure their integrity [6.7]. The samples were transferred aseptically into screw-cap vials and placed in a polystyrene box filled with dry ice. They were transported to a -80°C freezer in a university laboratory as quickly as possible [6.7]. Approximately 100 mg of each tissue sample was finely chopped using a sterile blade. DNA extraction was then performed using the Gentra Puregene Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), following the manufacturer's instructions for solid tissue protocols. The total DNA concentration and purity were assessed using the Nano Drop™ 1000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). The extracted DNA was stored at -80°C as previously described [6.7].

2.4. Fungal Load Determination

The fungal load was measured by quantifying the ribosomal internal transcribed spacer 2 (ITS2) relative to the human β-actin gene using SYBR Green-based real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and the 2–ΔΔCt method, as previously detailed [

6,

7].

2.5. Amplicon Library Preparation and Sequencing

The ITS2 amplification by the primers ITS3-F and ITS4-R linked to Illumina’s specific adapter sequences in standard PCR conditions. The resultant PCR amplicons (~250–590 bp) were purified using Agencourt AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA). A second PCR was performed to tag the amplicons with unique eight-base barcodes using Nextera XT v2 Index Kit sets A-D (Illumina, San Diego, CA). A set of negative amplification controls (master alone and with other reaction components) was included for both the amplicon production and indexing reactions. The tagged amplicons were then pooled together in equimolar concentrations and sequenced on a MiSeq Sequencing System (Illumina) using v3 2 × 300bp, paired-end sequencing chemistry in the Australian Centre for Ecogenomics, according to the manufacturer’s protocol as revealed previously [

6,

7].

2.6. The Processing of Sequencing Data

Raw sequencing data were deposited in the Sequence Reads Archive (SRA) and are publicly available under project number PRJNA375780. Reads with primer mismatches were removed, and primer sequences were trimmed. Paired sequences were then merged using PEAR [

2,

8] with the following parameters: a minimum amplicon length of 213 bp, a maximum amplicon length of 552 bp, and a p-value of 0.001. Preprocessing of the merged reads was carried out using Mothur v1.38.1 [

2,

8]. First, to minimize sequencing errors, reads containing ambiguous bases, reads with homopolymer stretches longer than 8 bp, or reads that did not achieve a sliding 50-nucleotide Q-score average of ≥30 were filtered out. Second, high-quality reads were checked for chimeras using Uchime [

6,

7] with the self-reference approach [

6,

7]. Finally, sequences representing non-fungal lineages were identified through preliminary taxonomy using Mothur's classification commands, and any unrelated sequences were removed.

2.6. Taxonomy Assignment Algorithm and Downstream Analysis

The reads were individually BLASTN searched against the reference set at alignment coverage of ≥99% and a percent identity of ≥98.5%. Hits were ranked by percent identity and, when equal, by bit score. Reads were assigned taxonomies of the best hits. Reads with the best hits representing more than one species were screened again for chimeras using a de novo check at 98% similarity with USEARCH v8.1.1861 and, if not chimeric, were assigned multiple-species taxonomy as described previously [

6,

7]. Reads with no matches at the specified criteria underwent secondary de novo chimera checking as above, and then de novo, species-level operational taxonomy unit (OTU) calling at 98% using USEARCH. Singleton OTUs were excluded; the rest were considered potentially novel species. A representative read from each was BLASTN-searched against the same reference sequence set again to determine the closest species for taxonomy assignment. The average relative abundance of each phylum, genera, and species was presented as a percentage [

6,

7].

3. Results

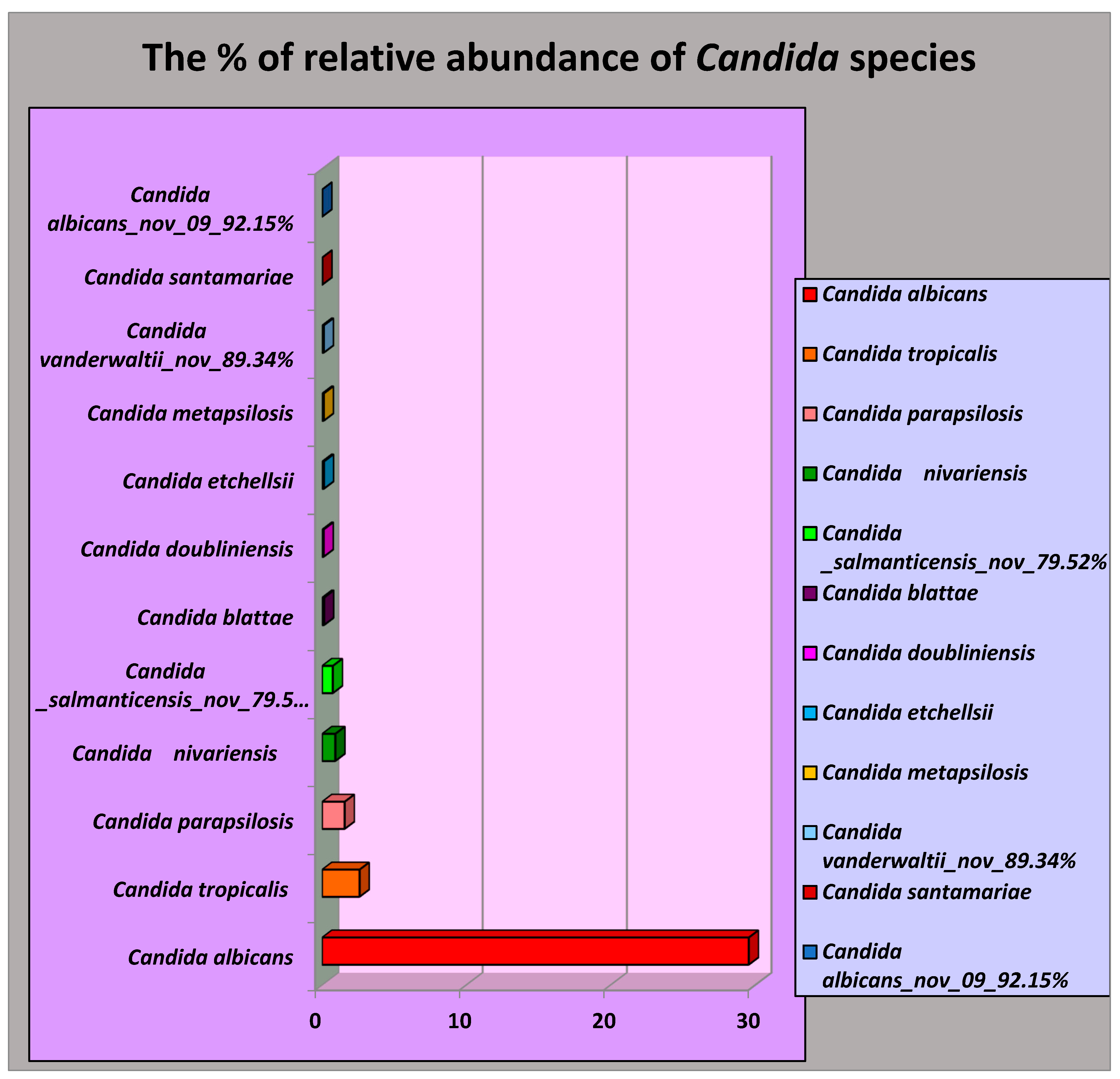

The carriage of Candida species in oral 25 FEP tissues expressed in the average relative abundance and their oral risk habits as follows.

Interestingly, 12 species of

Candida were identified in the FEP tissues of a group of Sri Lankan male patients with oral risk habits. Among these,

C. albicans was the most prevalent, with an average relative abundance of 29.56%. The other species detected included

Candida tropicalis (2.59%),

Candida parapsilosis (1.56%),

Candida niveriensis (0.91%),

Candida salmanticensis (0.74%),

Candida blattae (0.13%),

Candida doubliniensis (0.10%),

Candida etchellsii (0.12%),

Candida metapsilosis (0.10%),

Candida vanderwaltii (0.34%),

Candida santamariae (0.11%), and

Candida albicans_nov_92.15% (0.002%) as shown in

Figure 1.

According to

Table 1, 12 out of the FEP subjects, representing 48.0%, were daily betel chewers, while 28.0% reported chewing betel sometimes. Regarding smoking habits, 6 out of the controls, or 22.7%, were daily smokers. In terms of alcohol consumption, the majority, 15 individuals or 60.0%, were classified as occasional drinkers.

4. Discussion

According to the author, this was the first time NGS technologies were applied to speciate

Candida in a group of FEP patients with at least one of oral risk habit out of betel quid chewing, smoking and alcohol consumption also host factors in OSCC tissues of a group of Sri Lankan male patients. Since 1938, studies have reported that the prevalence of oral carriers of Candida albicans varies widely, ranging from fewer than 3% to 77% of adults [

8]. In the present study, the Sri Lankan male patients with fibro epithelial polyps), the carrier status reached 100%, with C. albicans being found at a significantly higher average relative abundance (29.56%) compared to Candida tropicalis (2.59%). The Candida species are known to cause a variety of superficial and systemic opportunistic infections, especially in immuno-compromised or weakened patients. Among these species, Candida albicans is the most prevalent. The body's strong innate and adaptive immune responses play a crucial role in preventing Candida from becoming pathogenic and help maintain its status as a harmless commensal organism. Experimental animal models of mucosal candidiasis have been essential in clarifying the various compartmentalized immune responses to C. albicans at different mucosal sites. Additionally, rodent models have played a crucial role in understanding host responses during the initiation and progression of several systemic C. albicans infections. Pathogenic effects of C. albicans carriage in in the present further to explore. In our study, 12 (48) % of FEP individuals were daily betel-quid chewers. Our finding supports the belief of betel quid chewers and the concept of smoking as one of the iatrogenic factors effects on oral candidiasis or as a local predisposing factor of Candida colonization and infection [

12]. Mortality is even higher in patients with septic shock following if resolves to candidemia [

12].

Furthermore, 15 out of 25 fibro epithelial polyp (FEP) subjects (60.0%) reported consuming alcohol weekly. This alcohol consumption is believed to potentially increase Candida colonization, as certain Candida species can produce carcinogenic acetaldehyde through alcohol metabolism. Chronic inflammation caused by these inflammatory substances may lead to a higher presence of Candida species in these carriers. Additionally, only 4 out of 25 subjects (16.0%) reported being non-smokers, indicating that 84% were smokers. Since C. albicans can undergo nitrosation, metabolizing the carcinogenic nitrosyl groups present in cigarette smoke, there may be an elevated presence of C. albicans among smokers. It is important to note that the small sample size was a limitation of this study. Furthermore, 15 out of 25 first-episode psychosis (FEP) subjects (60.0%) reported consuming alcohol weekly. This alcohol consumption is believed to potentially increase Candida colonization, as certain Candida species can produce carcinogenic acetaldehyde through alcohol metabolism. Chronic inflammation caused by these inflammatory substances may lead to a higher presence of Candida species in these carriers. Additionally, only 4 out of 25 subjects (16.0%) reported being non-smokers, indicating that 84% were smokers. Since C. albicans can undergo nitrosation, metabolizing the carcinogenic nitrosyl groups present in cigarette smoke, there may be an elevated presence of C. albicans among smokers as C. albicans is the most virulent of all It is important to note that the small sample size was a limitation of this study. The small sample size was a limitation of the present study. Moreover, inability of application of conventional culture techniques to identify the Candida species is another limitation of this study.

5. Conclusion and Recommendation

C. albicans was the most prevalent, with an average relative abundance of 29.56%. The other species detected included Candida tropicalis (2.59%), Candida parapsilosis (1.56%), Candida niveriensis (0.91%), Candida salmanticensis (0.74%), Candida blattae (0.13%), Candida doubliniensis (0.10%), Candida etchellsii (0.12%), Candida metapsilosis (0.10%), Candida vanderwaltii (0.34%), Candida santamariae (0.11%), and Candida albicans_nov_92.15% (0.002%) The oral Candida carriage in a group of Sri Lankan male oral fibroepithelial polyps patients with oral risk habits is worthy of further exploration, as immunosuppression can do more harm than good in these patients.

References

- Sahoo, S.R. GAIMS. J. Med. Sci. 2023, 3, 41–42.

- Perera, M.L.; Perera, I.R. Are there co-variations between herpes simplex virus status and oral risk habits in a cohort of Sri Lankan male oral fibroepithelial polyp patients? Findings from a Preliminary Study. Preprints.org, 20 August. [CrossRef]

- Lees, T.F.A.; Bogdashich, L.; Godden, D. Conserving resources in the diagnosis of intraoral fibroepithelial polyps. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2021, 59, e9–e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perera, M.; Perera, I.; Tilakaratne, W.M. Oral Microbiome and Oral Cancer. Immunol. Dent. 2020, 79–99. [Google Scholar]

- Perera, M.; Al-hebshi, N.N.; Perera, I.; Ipe, D.; Ulett, G.C.; Speicher, D.J.; Chen, T.; Johnson, N.W. A dysbiotic mycobiome dominated by Candida albicans is identified within oral squamous-cell carcinomas, J. Oral Microbiol. 2017, 9, 1385369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, M.L. The microbiome profile of oral squamous cell carcinoma tissues in a group of Sri Lankan male patients; Griffith University: Queensland, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, M.L.; Perera, I.R. Insight Into Versatility of Bacteriome Dominated by Rothia Mucilaginosa in Oral Fibro Epithelial Polyps. Biomed J Sci Tech Res BJSTR 2022, 47, MS.ID–007527. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, P.; Martin, M.V. Oral Microbiology, 4th ed.; Wright Edinburgh: London, UK; New York, NY, USA; Oxford, UK; Philadelphia, PA, USA; St Louis, MO, USA; Sydney, Australia; Toronto, ON, Canada, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, V.J.; Jones, M.; Dunkel, J.; Storfer, S.; Medoff, G.; Dunagan, W.C. Candidemia in a tertiary care hospital: Epidemiology, risk factors, and predictors of mortality. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1992, 15, 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wooley, M.T. Mycological findings in sputum. J. Lab. clin. Med. 1938, 23, 553–565. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, M. Oral Cavity and Candida albicans: Colonisation to the Development of Infection. Pathogens 2022, 11, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welagedara, P.G.R.U.M.; Jayasekera, P.I. 2024, 69. 69.

- Kollef, M.; Micek, S.; Hampton, N.; Doherty, J.A.; Kumar, A. Septic Shock Attributed to Candida Infection: Importance of Empiric Therapy and Source Control. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012, 54, 1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).