1. Introduction

The oral cavity provides the sanctuary to approximately 1000 bacterial species, followed by fungi, the vast majority being

Candida, methanogenic archaea, and two protozoa species (

Trichomonas tenax and Entamoeba gingivalis) according to the latest metagenomic revelations based on high-end next generation sequencing technologies [

1]. Compared to the oral bacteriome, the oral mycobiome is described as the rare biosphere [

2] because the oral mycobiome comprises less than 0.06% of saliva and 0.0001% of dental plaque in the microbial community [

3].

Candida species are normal inhabitant present in 7- 75% healthy individuals and immunosuppressive people with comorbidities [

4]. Thus, genus,

Candida dominated over 12 other taxa formed the core oral mycobiome [

2].

The sequelae of commensal to opportunistic pathogen are inarguably associated with the virulence attributes of this eukaryote [

5]. An array of local, systemic, and iatrogenic host factors act in concert and seem responsible for the aetiopathogenesis of candidiasis. The outcome of immunosuppression of the host provides an ideal opportunity for this opportunistic pathogen to increase the virulence and cause the disease [

5]. An unhealthy mucosal barrier, impaired phagocyte function, and acidic salivary pH are considered local host factors that may contribute to oral candidiasis [

5]. Systemic host factors that may predispose to oral candida infections include immuno-compromised individuality, diabetes, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infections, malignancies (leukaemia, lymphoma, and oral cancer), altered nutritional states (iron and vitamin deficiencies), and iatrogenic factors comprising oral risk habits [

2,

5,

6] antibiotic therapy, corticosteroid therapy, cytotoxic therapy, and radiotherapy) [

5].

Even though not included in the top10 cancer types globally according to GLOBOSCAN 2018, [2.7] oral squamous cell carcinoma representing (OSCC) more than 90% of oral cancer with poor prognosis and unsatisfactory five year survival poses a devastating public health burden due to higher prevalence in South Asia and Pacific islands [

2,

7]. In the local context it is the commonest thus ranking 1

st and the leading cause of cancer death among Sri Lankan men [

8,

9].There are substantial evidence on association of oral candidiasis with OSCC [

2,

7]. Even with promising evidence of high nitrosation potential of certain

Candida albicans strains to induce dysplasia experimentally and production carcinogenic acetaldehydes by candida spp. the causative role of

C. albicans in oral carcinogenesis yet to be proven [

2,

10]. In the light of these findings, the present retrospective study aimed to discover the host’s factors and the relative abundance of

Candida species of oral squamous cell carcinoma tissues in a group of Sri Lankan male patients.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

Ethical approval for the study was taken from the Faculty Research Committee, Faculty of Dental Sciences, University of Peradeniya, Sri Lanka (FRC/FDS/UOP/E/2014/32) and Griffith University Human Research Ethics Committee, Australia (DOH/18/14/HREC). Written informed consent was obtained from each participant as described previously [

2,

8].

2.2. Study Design, Sample Size Calculation, Exclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The main sample consisted of 134 cases of oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC), alongside a 134 control group comprised of individuals with benign mucosal lesions. The sample size was calculated using the formula outlined by Kelsey et al. [

11]. The study included Sinhala males 40 years and older, histologically confirmed OSCC originating from the buccal mucosa or tongue. Participants were required to have oral risk habits and must not have been on antibiotics for two months before data collection. Individuals who were non-Sinhalese, younger than 40 years, did not have at least one oral risk habit, or were on antibiotics within the past two months were excluded from this study.

2.2. Data Collection, Clinical Oral Examination and Statistical Analysis

Data were collected using a pretested, interviewer-administered questionnaire that gathered information on socio-demographics and risky habits, including smokeless tobacco use, areca nut consumption, betel quid chewing, tobacco smoking, and alcohol consumption. Clinical oral examinations were conducted by dental public health specialists, who thoroughly inspected the oral mucosa for any growths, ulcerations, or white patches. The number of missing teeth was recorded, and oral hygiene status was assessed using the Simplified Oral Hygiene Index. Additionally, periodontal health was evaluated by measuring bleeding on probing (BOP), periodontal pocket depth (PPD) and clinical attachment loss (CAL) at four sites for anterior teeth and six sites for posterior teeth as explained previously [

2,

8]. Data entering and analysis were performed by the SPSS-21, Statistical Package. The statistical significance of qualitative and quantitative data was obtained by descriptive statistics for percentage, frequency, mean, and standard deviation

2.3. Sampling Technique, Tissues Selection and DNA Extraction

Non-probability consecutive sampling technique was used. For suspected OSSC cases, tissue samples were collected from incisional biopsies taken for diagnosis for OSCC cases. The freshly obtained biopsy was placed on a stack of sterile gauze, and a small piece of tissue (approximately 3 mm³) was excised from the deep tissue at the macroscopically visible advancing edge of the neoplasm, ensuring that contamination from the tumor surface was avoided. A new sterile surgical blade was used for each case. The sample was then aseptically transferred into a screw-cap vial and placed in a polystyrene box filled with dry ice. These samples were transferred to a −80°C freezer in a university laboratory as soon as possible. At the same time, the remainder of the biopsy was sent in 10% buffered formalin for histopathologically diagnosis. Only samples that were histopathologically confirmed as OSSC were included in the study as published previously [

2,

8].

Tissue samples (~100 mg each) were finely chopped using a sterile blade. DNA extraction was then performed using Gentra Puregene Tissue kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), according to the manufacturer’s instructions (solid tissue protocol).

Total DNA concentration and purity were determined using the NanoDrop™1000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). The extracts were stored at –80°C as explained previously [

2,

8].

2.4. Fungal Load Determination

The fungal load was assessed by quantification of the ribosomal internal transcribed spacer 2 (ITS2) normalized to the human β-actin gene using SYBR Green based real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and the 2–ΔΔCt method as described in detail previously [

2,

8].

2.5. Amplicon Library Preparation and Sequencing

The ITS2 was amplified using the primers ITS3-F and ITS4-R, linked to Illumina’s specific adapter sequences in standard PCR conditions. The resultant PCR amplicons (~250–590 bp) were purified using Agencourt AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA). A second PCR was performed to tag the amplicons with unique eight-base barcodes using Nextera XT v2 Index Kit sets A-D (Illumina, San Diego, CA). A set of negative amplification controls (master alone and with other reaction components) was included for both the amplicon production and indexing reactions. The tagged amplicons were then pooled together inequimolar concentrations and sequenced on a MiSeq Sequencing System (Illumina) using v3 2 × 300bp, paired-end sequencing chemistry in the Australian Centre for Ecogenomics, according to the manufacturer’s protocol as revealed previously [

2,

8].

2.6. The Processing of Sequencing Data

Raw sequencing data were deposited in the Sequence Reads Archive (SRA) and are publicly available under project number PRJNA375780. Reads with primer mismatches were removed, and primer sequences were trimmed. Paired sequences were then merged using PEAR [

2,

8] with the following parameters: a minimum amplicon length of 213 bp, a maximum amplicon length of 552 bp, and a p-value of 0.001. Preprocessing of the merged reads was carried out using Mothur v1.38.1 [

2,

8]. First, to minimize sequencing errors, reads containing ambiguous bases, reads with homopolymer stretches longer than 8 bp, or reads that did not achieve a sliding 50-nucleotide Q-score average of ≥30 were filtered out. Second, high-quality reads were checked for chimeras using Uchime [

2,

8] with the self-reference approach [

2,

8]. Finally, sequences representing non-fungal lineages were identified through preliminary taxonomy using Mothur's classification commands, and any unrelated sequences were removed.

2.7. Taxonomy Assignment Algorithm and Downstream Analysis

The reads were individually BLASTN searched against the reference set at alignment coverage of ≥99% and a percent identity of ≥98.5%. Hits were ranked by percent identity and, when equal, by bit score. Reads were assigned taxonomies of the best hits. Reads with the best hits representing more than one species were screened again for chimeras using a de novo check at 98% similarity with USEARCH v8.1.1861 and, if not chimeric, were assigned multiple-species taxonomy as described previously [

2,

8]. Reads with no matches at the specified criteria underwent secondary de novo chimera checking as above, and then de novo, species-level operational taxonomy unit (OTU) calling at 98% using USEARCH. Singleton OTUs were excluded; the rest were considered potentially novel species and a representative read from each was BLASTN-searched against the same reference sequence set again to determine the closest species for taxonomy assignment as explained previously. The average relative abundance of each phyla, genera and species were presented as a percentage [

2,

8].

3. Results

The results of 22 OSCC cases were presented here to understand host factors and proportion of Candida species in a group of Sri Lankan OSCC males as four samples ended up with a low read count (<3,000) and one with very high count (an outlier) and were thus excluded. Results of host associated factors are presented as hereafter for 22 OSCC subjects.

3.1. Host Associated Factors

As per the

Table 1, samples were collected from nine oro-maxillofacial (OMF) units located in six provinces. The highest number of subjects with oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) was recruited from the District General Hospital in Kegalle, accounting for five participants (22.7%). This was followed by the National Dental Hospital (Teaching) in Colombo 07 and the Provincial General Hospital in Badulla, each contributing four subjects (18.2%). The OMF units were selected to obtain a representative subsample of the majority of oral cancer patients, adhering to stringent inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Table 2 presents the socio-demographic profile of subjects with Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma (OSCC). The mean age of these subjects was 61.18 years, with a standard deviation of± 7.85 years. Additionally, a higher proportion of individuals with OSCC reported lower levels of educational attainment, including no formal education, primary education, Education-Ordinary Level, Advanced Level, and Degree/Diploma (see

Table 2). Furthermore, the majority of cases were associated with occupations such as farming and skilled/unskilled manual labor. Thus, the vast majority of these OSCC subjects 18 (95.5%) were belonged to a low socioeconomic profile

Table 3 presents the distribution of OSCC subjects based on their tooth-cleaning habits and various clinical indicators. Exactly, half of the OSCC subjects, 11 (50%) were used to less optimal tooth cleaning methods, such as cleaning with a finger, using charcoal, or combining charcoal with a toothbrush. Additionally, individuals with OSCC exhibited a higher number of missing and mobile teeth. This was further highlighted by the assessment of oral hygiene status using the OHI-S [

12], which revealed that 27.3% of OSCC subjects had poor oral hygiene, while 63.6% had a fair oral hygiene status. Furthermore, OSCC subjects showed significantly high levels of periodontal disease, with 36.4% classified as having severe periodontitis and 50.0% as having moderate periodontitis, according to case definitions established by the Centres for Disease Control (CDC) Periodontal Disease Surveillance Group, as outlined by Page and Eke in 2007 [

13].

Table 4 illustrates the risk habit profile for betel chewing, smoking, and alcohol consumption among OSCC subjects, as well as their daily vegetable and fruit intake, categorized as consuming less than 5 portions or 5 or more portions. The findings show that the vast majority18 (81.8%) of OSCC cases were daily betel chewers, with 3 (13.6%) reporting a history of past betel chewing. Regarding smoking habits, 40.0% of the cases smoked daily. In terms of alcohol consumption, most OSCC subjects 13 (59.1%) were weekly drinkers. Additionally, the most of the 18 (81.8%) of the study subjects consumed fewer than 5 portions of vegetables and fruits daily.

3.2. The Proportion of Candida Species of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Tissues in a Group of Sri Lankan Male Patients

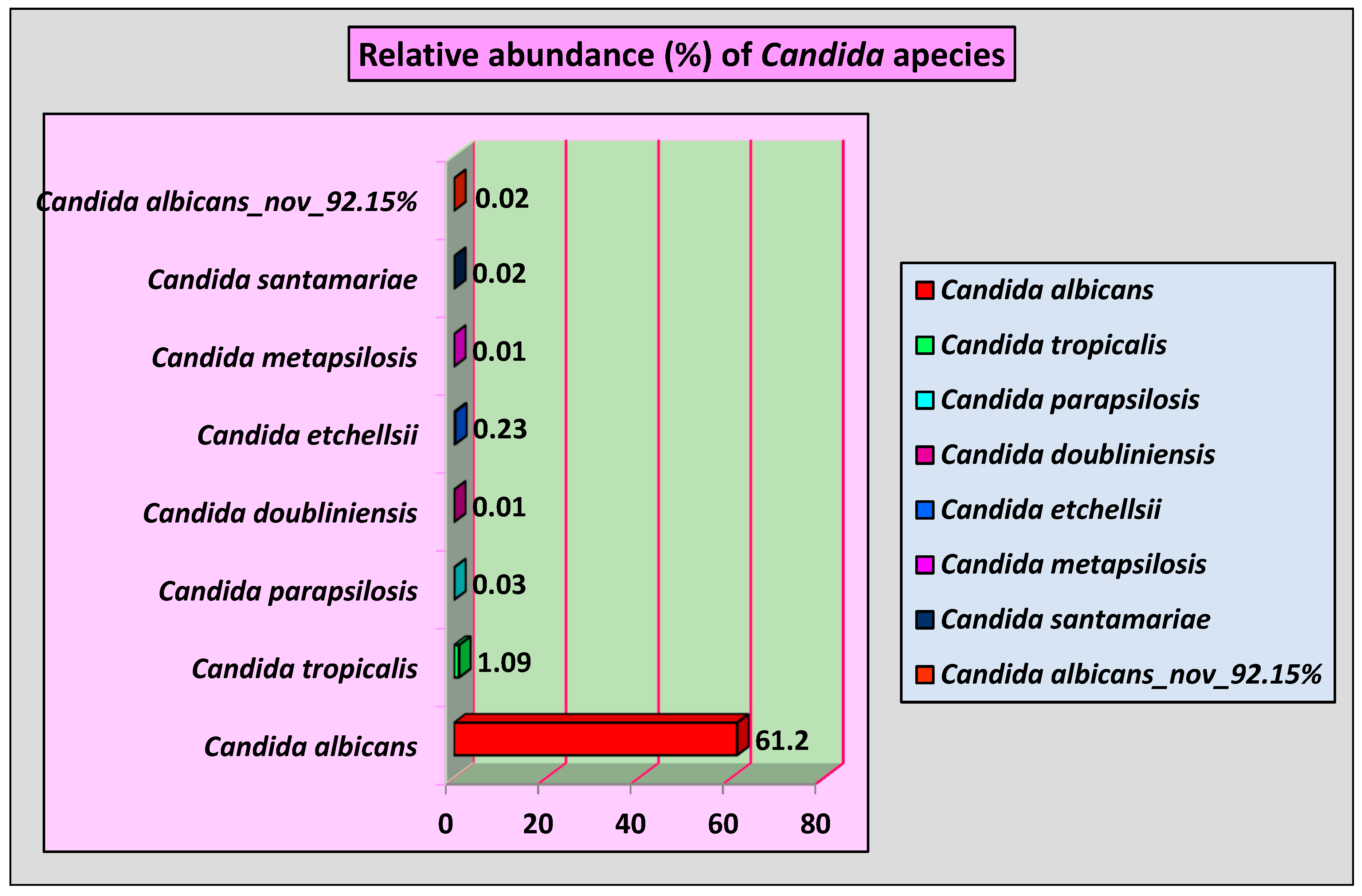

As demonstrated in

Figure 1, eight

Candida species were identified. Among them,

Candida albicans was detected in 100% of OSCC subjects with average relative abundance of 61.2%. Moreover,

Candida tropicalis was identified with an average relative abundance of 1.09% followed by

Candida etchelslii, which was presented in OSCC subjects with an average relative abundance of 0.23%. For the 1st time, a novel

Candida species named

Candida albicans_nov_92.15% was identified by nucleotide sequencing with an average relative abundance of 0.02%.

Candida doubliniensis and

Candida metapsilosis were the least abundant each with 0.01 average relative abundance in OSCC tissue.

4. Discussion

According to the author, this was the first time NGS technologies were applied to identify

Candida species and host factors in OSCC tissues of a group of Sri Lankan male patients. Thus, there is a dearth of information on the statistically significant association of risk factors with the prevalence of

C. albicans obtained by applying logistic regression in powered studies after controlling for confounders. Since 1938, studies have reported that the prevalence of oral carriers of

Candida albicans varies widely, ranging from fewer than 3% to 77% of adults [

14]. In the present study, the Sri Lankan male patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC), the carrier status reached 100%, with

C. albicans being found at a significantly higher prevalence (61.2%) compared to

Candida tropicalis (1.09%).[

2]. There is promising evidence from case-control studies indicating that the prevalence of candidiasis is higher in OSCC and oral potentially malignant disorders (OPMD) cases compared to healthy controls.

Candida species are known to cause a variety of superficial and systemic opportunistic infections, especially in immuno-compromised or weakened patients. Among these species,

Candida albicans is the most prevalent. The body's strong innate and adaptive immune responses play a crucial role in preventing

Candida from becoming pathogenic and help maintain its status as a harmless commensal organism. The rate of Candida colonization tends to increase in the presence of a tumor microenvironment, particularly in neoplastic diseases like oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC). Experimental animal models of mucosal candidiasis have been essential in clarifying the various compartmentalized immune responses to C. albicans at different mucosal sites. Additionally, rodent models have played a crucial role in understanding host responses during the initiation and progression of systemic C. albicans infections.

In our study, the mean age of OSCC subjects was 61.18±7.85 years. Our finding was consistent with the finding that age above 60 years was statistically significantly associated with high levels of

Candida in oral potentially malignant disorders (OPMDs) and oral cancer (OC) in Thailand [

17] and up to 74% in elderly carry

Candida in their oral cavities as published elsewhere [

18]. The vast majority of these OSCC subjects 18 (95.5%) were belonged to a low socioeconomic profile in our study. Our finding was corroborating the notion of poor socio economic status is well established factor for oral cancer as well as candidiasis [

2,

8]. Furthermore, 9.36±8.73 of missing teeth, 6 (27.3%) of poor oral hygiene and 11 (50.0%) of moderate as well as 8 (36.4%) severe periodontitis can be considered as local predisposing factors for oral candidiasis [

16,

19].

In our study, 18(81. 8) % of OSCC individuals were daily betel-quid chewers. Our finding is on par with a statistically significant association between betel quid chewing and high levels of intra-oral

Candida compared with non-betel quid chewers [

17]. Exactly, 9 (40.0%) of OSCC subjects were daily smokers. This finding of the present study substantiates the finding of a statistically significant association between smoking and the higher prevalence of oral candidiasis published elsewhere [

17] and the concept of smoking as one of the iatrogenic factors effects on oral candidiasis or as a local predisposing factor of

Candida colonization and infection [

19]. Moreover, 13 (59.1%) of OSCC subjects were weekly alcohol consumers but alcohol consumption was not statistically significantly associated with oral candidiasis in a study conducted to investigate the presence of

Candida and its related factors in participants who attended the oral cancer screening program in the lower northeastern districts of Thailand [

17]. Lastly, almost 82% of OSCC subjects did not consume <5 portions of fruits and vegetables. Our finding confirms the belief that altered nutritional status and iron/vitamin deficiencies may act as systemic host factors to promote oral candidiasis [

16]. Small sample size was limitation of the present study.

5. Conclusion and Recommendations

Candida albicans was elevated immensely in OSCC tissues, followed by Candida tropicalis, Candida parapsilosis, Candida doubliniensis, Candida etchellsii, Candida metapsilosis, Candida santamariae and Candida albicans_nov_92.15%. The older age, low socio-economic status, poor oral hygiene status, periodontal disease status, oral risk habits, nutritional deficiencies, and OSCC status appeared as host factors that accounted for elevated C. albicans occurrence (61.2% of average relative abundance) in all OSCC tissues (100%) of a group of male patients. Powered matched case-control studies, controlling confounders to apply multivariate logistic regression are much recommended to find out the reliability of results of the present study.

Author Contributions

Manosha Perera:

Conceptualization; experimenta design; laboratory analysis; interpretation of results obtained by laboratory and statistical analysis; writing the original draft. Irosha Perera: Conceptualization; study design; sample size calculation; performing excisional biopsies; followed patients and revision; statistical analysis; revision of the manuscript.

Funding

This study is funded by Griffith University International Postgraduate Research Scholarship (GUIPRS) 2012, Grant No: MSC 1010, class H,MPP and self-finance (M.P. and I.P.)

Ethics Statement

The microbiome profile of oral squamous cell carcinoma tissues in a group of Sri Lankan male patients which received ethical approval from the Faculty Research Committee, Faculty of Dental Sciences, University of Peradeniya, Sri Lanka (FRC/ FDS/UOP/E/2014/32) and Griffith University Human Research Ethics Committee, Australia (DOH/18/14/ HREC).

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the late Professor Newell Johnson and Associate Professor Glen Ulett, Professor of Microbiology at the School of Medical Science and Pharmacy, Gold Coast Campus, Griffith University, for their valuable contributions that helped make this study a success. We are grateful to Professor W.M. Tilakaratne, Senior Professor of Oral Pathology, and Professor L. Samaranayake, Professor of Oral Microbiology, for their guidance throughout this research. We also thank the Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons — Dr. Sharika Gunathilake, Dr. S.A.K.J. Kumara, Dr. Ranjith Lal Kandewatte, Dr. P. Kirupakaran, Dr. D.K. Dias, Dr. Chamara Athukorale, Dr. Suresh Shanmuganathan, and Dr. T. Sabesan — for facilitating data and sample collection from their respective Oral and Maxillofacial Units. Last but certainly not least, we express our appreciation to Dr. Rohitha Muthugala, Consultant Virologist at the National Hospital, Kandy, Sri Lanka, for his crucial advocacy role.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Perera, M., Perera, I., & Tilakaratne, W. M. Oral Microbiome and Oral Cancer. Immunology for Dentistry. 2020; 79-99.

- Perera M, Al-hebshi NN, Perera I, Ipe D, Ulett GC, Speicher DJ, Chen T, Johnson NW. A dysbiotic mycobiome dominated by Candida albicans is identified within oral squamous-cell carcinomas. J Oral Microbiol.2017 9(1):1385369.

- Baraniya D, Chen T, Nahar A, et al. Supragingival mycobiome and inter-kingdom interactions in dental caries. J Oral Microbiol. 2020; 12(1):1729305.

- Rindum JL, Stenderup A, Holmstrup P. Identification of Candida albicans types related to healthy and pathological oral mucosa. J Oral Pathol Med 1994; 23: 406-412.

- C van Wyk & V Steenkamp (2011) Host factors affecting oral candidiasis, Southern African Journal of Epidemiology and Infection, 2011; 26:1, 18-21. [CrossRef]

- Deeiam et al. BMC Oral Health (2023) 23:527. [CrossRef]

- Perera M, Al-Hebshi N, Perera I, Ipe D, Ulett G, Speicher D, et al. Inflammatory Bacteriome and Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Journal of dental research. 2018:0022034518767118.

- Perera, M. L. The microbiome profile of oral squamous cell carcinoma tissues in a group of Sri Lankan male patients. Griffith University, Queensland, Australia. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Manosha Lakmali P, Irosha Rukmali P. Impact of Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) Status on Well Established Risk Profile of Oral Cancer in Sri Lanka. Adv Dent & Oral Health. 2021; 14(1): 555880. [CrossRef]

- Kang, J., He, Y., Hetzl, D., Jiang, H.Q., Jun, M.K., Jun, M.S., Khng, M., Cirillo, N. and McCullough, M.J. (2016) A Candid Assessment of the Link between Oral Candida Containing Biofilms and Oral Cancer. Advances in Microbiology, 2016; 201; 6,115-123. [CrossRef]

- Kelsey et al Methods in Observational Epidemiology 2nd Edition, Table 12–15 Fleiss, Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions, formulas 3.18 &3.19.

- Greene, J.C. and Vermillion, J.R. (1964) The Simplified Oral Hygiene Index. The Journal of the American Dental Association, 68. [CrossRef]

- Page RC, Eke PI. Case definitions for use in population-based surveillance of periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2007 Jul; 78(7 Suppl):1387-99. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wooley M. T. 1938. Mycological findings in sputum. J. Lab. clin. Med.1938; 23, 553-565.

- Belibasakis GN, Seneviratne CJ, Jayasinghe RW, Thi- Duy PV. Bostanci N, Choi Y. Bacteriome and mycobiome dysbiosis in oral mucosal dysplasia and oral cancer. Periodontology 2000. 2024; 00:1–17. wiley online library.

- C van Wyk & V Steenkamp (2011) Host factors affecting oral candidiasis, Southern African Jornal of Epidemiology and Infection, 26:1, 18-21. [CrossRef]

- Deeiam K, Pankam J, Sresumatchai V, Visedketkan P, Jindavech W, Rungraungrayabkul D, Pimolbutr K, Klongnoi B, Khovidhunkit SP. Presence of Candida and its associated factors in participants attending oral cancer screening in the lower northeastern area of Thailand. BMC Oral Health. 2023 Jul 28;23(1):527. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sato, T.; Kishi, M.; Suda, M.; Sakata, K.; Shimoda, H.; Miura, H.; Ogawa, A.; Kobayashi, S. Prevalence of Candida albicans Non-Albicans the tongue dorsa of elderly people living in a post-disaster area: A cross-sectional survey. BMC Oral Health 2017, 17, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, M. Oral Cavity and Candida albicans: Colonisation to the Development of Infection. Pathogens 2022, 11, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).