Submitted:

16 February 2025

Posted:

17 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

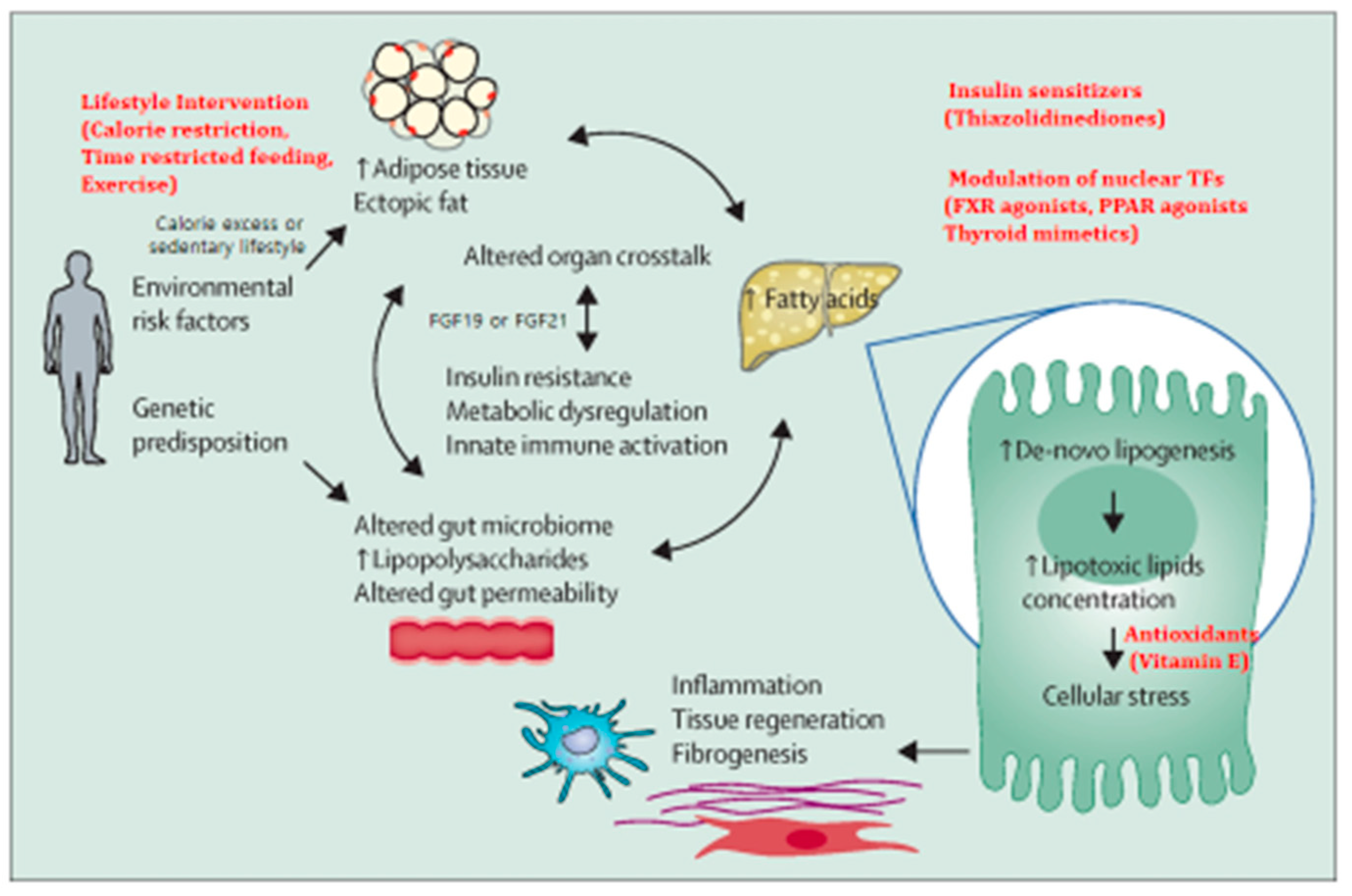

2. Pathogenesis in General

3. Molecular Pathways of NAFLD Progression

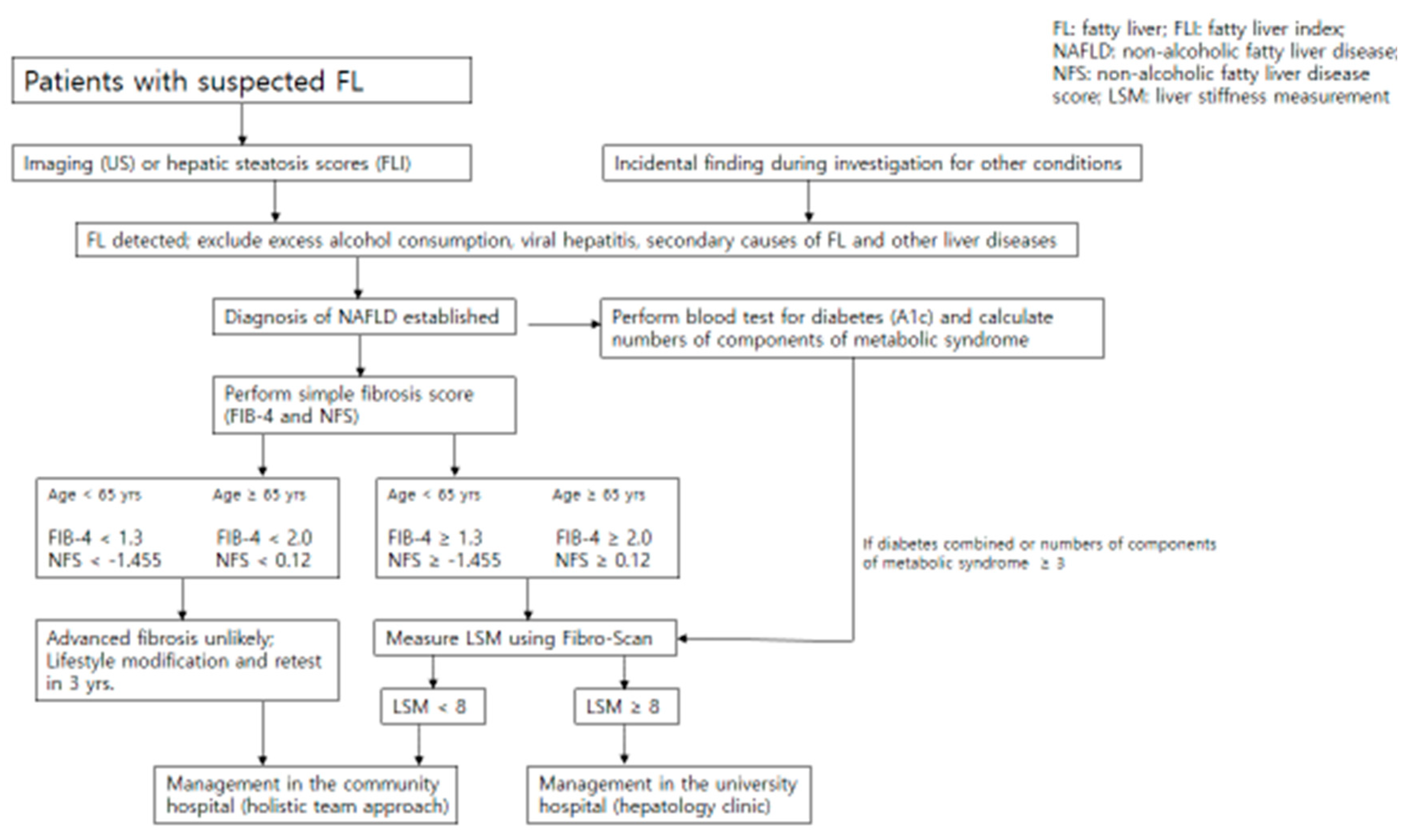

4. Diagnosis and Assessment of Disease Severity

5. Non-Invasive Tests of Disease Severity

6. Comorbid Conditions

7. Prevention & Management of NAFLD

8. Management of NAFLD in the Community

9. Optimizing Management with Existing Therapeutics

10. Emerging Therapeutics of NASH

11. MiRNA Targeting for NAFLD

12. Therapeutic Potential of a New Antioxidant Protein Delivery in NAFLD

13. Challenges and Prospects

References

- Park Y, Lee HK, Koh C-S, Min HK, Yoo KY, Kim YI, Shin YS: Prevalence of diabetes mellitus and IGT in Yonchon County, Korea. Diabetes Care 18: 534-538, 1995.

- Shin CS, Lee HK, Koh C-S, Kim YI, Shin YS, Yoo KY, Paik HY, Park Y, Yang BG: Risk factors for the development of NIDDM in Yonchon County, Korea. 1: Diabetes Care 20(12), 1842.

- Younossi, Z.M.; Koenig, A.B.; Abdelatif, D.; Fazel, Y.; Henry, L.; Wymer, M. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease—meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology 2016; 64: 73–84.

- Younossi Z, Anstee QM, Marietti M, Hardy T, Henry L, Eslam M, George J, Bugianesi E: Global burden of NAFLD and NASH: trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018; 15: 11–20.

- Park Y, Kim TW: Liver cirrhosis and diabetes mellitus. Taehan Kan Hakhoe Chi 8(1): 22-34, 2002.

- Paik, J.M.; Golabi, P.; Younossi, Y.; Mishra, A.; Younossi, Z.M. Changes in the global burden of chronic liver diseases from 2012 to 2017: the growing impact of NAFLD. Hepatology 2020; 72: 1605–16.

- Powell, E.E.; Wong, V.W.-S.; Rinella M:, N.A.F.L.D. Lancet 2021; 397:, 2212–24.

- Estes, C.; Razavi, H.; Loomba, R.; Younossi, Z.; Sanyal, A.J. Modeling the epidemic of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease demonstrates an exponential increase in burden of disease. Hepatology 2018; 67: 123–33.

- Cusi K, Isaacs S, Barb D, Basu R, Caprio S, Garvey WT, Kashyap S, Mechanick JI, Mouzaki M, Nadolsky K, Rinella ME, Vos MB, Younossi Z: American association of clinical endocrinology clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in primary care and endocrinology clinical settings: Co-sponsored by the American association for the study of liver diseases (AASLD). Endocr Pract 2022; 28(5):528-562.

- Eslam M, Newsome PN, Sarin SK, Anstee QM, Targher G, Romero-Gomez M, Zelber-Sagi S, Wong VW, Dufour JF, Schattenberg JM, Kawaguchi T, Arrese M, Valenti L, Shiha G, Tiribelli C, Yki-Järvinen H, Fan JG, Grønbæk H, Yilmaz Y, Cortez-Pinto H, Oliveira CP, Bedossa P, Adams LA, Zheng MH, Fouad Y, Chan WK, Mendez-Sanchez N, Ahn SH, Castera L, Bugianesi E, Ratziu V, George J: A new definition for metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: an international expert consensus statement. J Hepatol 2020; 73: 202–09.

- Hue, L.; Taegtmeyer, H. The Randle cycle revisited: a new head for an old hat. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2009; 297: E578-91.

- García-Ruiz, C.; Baulies, A.; Mari, M.; García-Rovés, P.M.; Fernandez-Checa, J.C. Mitochondrial dysfunction in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and insulin resistance: cause or consequence? Free Radic Res. 2013; 47: 854-68.

- Smith, G.I.; Shankaran, M.; Yoshino, M.; Schweitzer, G.G.; Chondronikola, M.; Beals, J.W.; Okunade, A.L.; Patterson, B.W.; Nyangau, E.; Field, T.; Sirlin, C.B.; Talukdar, S.; Hellerstein, M.K.; Klein, S. Insulin resistance drives hepatic de novo lipogenesis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Clin Invest 2020; 130: 1453-1460.

- Barrow, F.; Khan, S.; Wang, H. ; Revelo XS: The emerging role of B cells in the pathogenesis of, N.A.F.L.D. Hepatology 2021; 74: 2277-2286.

- Friedman, S.L.; Neuschwander-Tetri, B.A.; Rinella, M.; Sanyal, A.J. Mechanisms of NAFLD development and therapeutic strategies. Nat Med 2018; 24: 908–22.

- Sanyal, A.J. Past, present and future perspectives in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol.

- Lefere, S.; Tacke, F. Macrophages in obesity and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: crosstalk with metabolism. JHEP Rep.

- Azzu, V.; Vacca, M.; Virtue, S.; Allison, M.; Vidal-Puig, A. Adipose tissue liver cross talk in the control of whole-body metabolism: implications in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology 2020; 158: 1899–912.

- Aron-Wisnewsky, J.; Warmbrunn, M.V.; Nieuwdorp, M.; Clément, K. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: modulating gut microbiota to improve severity? Gastroenterology 2020; 158: 1881–98.

- Somm E, Jornayvaz FR: Fibroblast Growth Factor 15/19: From Basic Functions to Therapeutic Perspectives. Endocr Rev 2018; 39: 960–989.

- Asrih, M.; Altirriba, J.; Rohner-Jeanrenaud, F.; Jornayvaz, F.R. Ketogenic Diet Impairs FGF21 Signaling and Promotes Differential Inflammatory Responses in the Liver and White Adipose Tissue. PLoS ONE, 2015; 10: e0126364. [Google Scholar]

- Author’s unpublished observation.

- Loomba R, Seguritan V, Li W, Long T, Klitgord N, Bhatt A, Dulai PS, Caussy C, Bettencourt R, Highlander SK, Jones MB, Sirlin CB, Schnabl B, Brinkac L, Schork N, Chen CH, Brenner DA, Biggs W, Yooseph S, Venter JC, Nelson KE: Gut microbiome-based metagenomic signature for non-invasive detection of advanced fibrosis in human nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Cell Metab, 2017; 25: 1054–62.e5.

- Caussy C, Tripathi A, Humphrey G, Bassirian S, Singh S, Faulkner C, Bettencourt R, Rizo E, Richards L, Xu ZZ, Downes MR, Evans RM, Brenner DA, Sirlin CB, Knight R, Loomba R: A gut microbiome signature for cirrhosis due to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat Commun, 2019; 10: 1406.

- Inciardi RM, Mantovani A, Targher G: Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease as an emerging risk factor for heart failure. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2023; 20(4):308-319.

- Badmus OO, Hillhouse SA, Anderson CD, Hinds TD, Stec DE: Molecular mechanisms of metabolic associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD): functional analysis of lipid metabolism pathways. Clin Sci (Lond). 2022; 136(18):1347-1366.

- Buzzetti E, Pinzani M, Tsochatzis EA: The multiple-hit pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Metabolism 2016; 65: 1038–1048.

- Parthasarathy G, Revelo X, Malhi H: Pathogenesis of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis: An Overview. Hepatol Commun, 2020; 4: 478–492.

- Ferguson D, Finck BN: Emerging therapeutic approaches for the treatment of NAFLD and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2021; 17(8):484-495.

- Samuel, V.T.; Shulman, G.I. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease as a nexus of metabolic and hepatic diseases. Cell Metab, 2018;27:22–41. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu YY, Zhang J, Zeng FY, Zhu YZ: Roles of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) in the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Pharmacol Res 2023; 192:106786.

- Bril F, Ortiz-Lopez C, Lomonaco R, Orsak B, Freckleton M, Chintapalli K, Hardies J, Lai S, Solano F, Tio F, Cusi K: Clinical value of liver ultrasound for the diagnosis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in overweight and obese patients. Liver Int, 2015; 35: 2139–46.

- Wong, V.W.; Adams, L.A.; de Lédinghen, V.; Wong, G.L.; Sookoian, S. Noninvasive biomarkers in NAFLD and NASH—current progress and future promise. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2018; 15: 461–78. [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis H, Craig D, Barker R, Spiers G, Stow D, Anstee QM, Hanratty B: Metabolic risk factors and incident advanced liver disease in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): a systematic review and meta-analysis of population-based observational studies. PLoS Med, 2020; 17: e1003100.

- Pitisuttithum P, Chan WK, Piyachaturawat P, Imajo K, Nakajima A, Seki Y, Kasama K, Kakizaki S, Fan JG, Song MJ, Yoon SK, Dan YY, Lesmana L, Ho KY, Goh KL, Wong VWS, Treeprasertsuk S: Predictors of advanced fibrosis in elderly patients with biopsy-confirmed nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: the GOASIA study. BMC Gastroenterol, 2020; 20: 88.

- Chen VL, Oliveri A, Miller MJ, et al. PNPLA3 Genotype and Diabetes Identify Patients With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease at High Risk of Incident Cirrhosis. Gastroenterology, 2023;164:966-977.e17.

- Koo, B.K.; Lee, D.H.; Park, J.H.; Kim, W. Heterogeneity in the risk of incident liver cirrhosis driven byPNPLA3genotype and diabetes among different populations. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr, 2024;13(1):115-118. [Google Scholar]

- Wong VW, Wong GL, Tsang SW, Hui AY, Chan AW, Choi PC, Chim AM, Chu S, Chan FK, Sung JJ, Chan HL: Metabolic and histological features of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease patients with different serum alanine aminotransferase levels. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2009; 29: 387–396.

- Mahady SE, Macaskill P, Craig JC, Wong GLH, Chu WCW, Chan HLY, George J, Wong VWS: Diagnostic accuracy of noninvasive fibrosis scores in a population of individuals with a low prevalence of fibrosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2017; 15: 1453–60.e1.

- Hagström, H.; Talbäck, M.; Andreasson, A.; Walldius, G.; Hammar, N. Ability of noninvasive scoring systems to identify individuals in the population at risk for severe liver disease. Gastroenterology, 2020; 158: 200–14. [Google Scholar]

- Eddowes PJ, Sasso M, Allison M, Tsochatzis E, Anstee QM, Sheridan D, Guha IN, Cobbold JF, Deeks JJ, Paradis V, Bedossa P, Newsome PN: Accuracy of FibroScan controlled attenuation parameter and liver stiffness measurement in assessing steatosis and fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology, 2019; 156: 1717–30.

- Tsochatzis EA, Newsome PN: Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and the interface between primary and secondary care. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2018; 3: 509–17.

- Lee YH, Cho Y, Lee BW, Park CY, Lee DH, Cha BS, Rhee EJ: Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in diabetes. Part I: epidemiology and diagnosis. Diabetes Metab J, 2019;43:31-45.

- Lucero D, Miksztowicz V, Gualano G, Longo C, Landeira G, Álvarez E, Zago V, Brites F, Berg G, Fassio E, Schreier L: Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease associated with metabolic syndrome: Influence of liver fibrosis stages on characteristics of very low-density lipoproteins. Clin Chim Acta. 2017; 473:1-8.

- Allen AM, Hicks SB, Mara KC, Larson JJ, Therneau TM: The risk of incident extrahepatic cancers is higher in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease than obesity - a longitudinal cohort study. J Hepatol, 2019; 71: 1229–36.

- Ma J, Hennein R, Liu C, Long MT, Hoffmann U, Jacques PF, Lichtenstein AH, Hu FB, Levy D: Improved diet quality associates with reduction in liver fat, particularly in individuals with high genetic risk scores for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology, 2018; 155: 107–17.

- Gerage AM, Ritti-Dias RM, Balagopal PB, Conceição RD, Umpierre D, Santos RD, Cucato GG, Bittencourt MS: Physical activity levels and hepatic steatosis: a longitudinal follow-up study in adults. J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2018; 33: 741–46.

- Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE, Charlton M, Cusi K, Rinella M, Harrison SA, Brunt EM, Sanyal AJ: The diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: practice guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology, 2018; 67: 328–57.

- Anstee, Q.M.; Targher, G.; Day, C.P. Progression of NAFLD to diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease or cirrhosis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2013; 10: 330–44. [Google Scholar]

- Patel PJ, Hayward KL, Rudra R, Horsfall LU, Hossain F, Williams S, Johnson T, Brown NN, Saad N, Clouston AD, Stuart KA, Valery PC, Irvine KM, Russell AW, Powell EE: Multimorbidity and polypharmacy in diabetic patients with NAFLD: implications for disease severity and management. Medicine (Baltimore), 2017; 96: e6761.

- Lee BW, Lee YH, Park CY, Rhee EJ, Lee WY, Kim NH, Choi KM, Park KG, Choi YK, Cha BS, Lee DH; Korean Diabetes Association (KDA) Fatty Liver Research Group: Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a position statement of the fatty liver research group of the Korean diabetes association. Diabetes Metab J, 2020; 44: 382–401.

- Cusi, K. A diabetologist’s perspective of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH): knowledge gaps and future directions. Liver Int, 2020; 40 (suppl 1): 82–88. [Google Scholar]

- American Diabetes Association. 4. Comprehensive medical evaluation and assessment of comorbidities: standards of medical care in diabetes—2019. Diabetes Care 2019; 42 (suppl 1): S34–45.

- Vilar-Gomez E, Martinez-Perez Y, Calzadilla-Bertot L, Torres-Gonzalez A, Gra-Oramas B, Gonzalez-Fabian L, Friedman SL, Diago M, Romero-Gomez M: Weight loss through lifestyle modification significantly reduces features of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology, 2015; 149: 367–78.e5.

- Pavlou V, Cienfuegos S, Lin S, Ezpeleta M, Ready K, Corapi S, Wu J, Lopez J, Gabel K, Tussing-Humphreys L, Oddo VM, Alexandria SJ, Sanchez J, Unterman T, Chow LS, Vidmar AP, Varady KA, Effect of time-restricted eating on weight loss in adults with type 2 diabetes. A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open, 2023;6(10):e2339337.

- Wilkinson MJ, Manoogian ENC, Zadourian A, Lo H, Fakhouri S, Shoghi A, Wang X, Fleischer JG, Navlakha S, Panda S, Taub PR: Ten-hour time-restricted eating reduces weight, blood pressure, and atherogenic lipids in patients with metabolic syndrome. Cell Metab. 2020;31(1):92-104.e5.

- Lassailly G, Caiazzo R, Ntandja-Wandji L-C, Gnemmi V, Baud G, Verkindt H, Ningarhari M, Louvet A, Leteurtre E, Raverdy V, Dharancy S, Pattou F, Mathurin P: Bariatric surgery provides long-term resolution of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and regression of fibrosis. Gastroenterology, 2020; 159: 1290–301.e5.

- Musso G, Cassader M, Rosina F, Gambino R: Impact of current treatments on liver disease, glucose metabolism and cardiovascular risk in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. Diabetologia, 2012; 55: 885-904.

- Sanyal AJ, Chalasani N, Kowdley KV, McCullough A, Diehl AM, Bass NM, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Lavine JE, Tonascia J, Unalp A, Van Natta M, Clark J, Brunt EM, Kleiner DE, Hoofnagle JH, Robuck PR; NASH CRN: Pioglitazone, vitamin E, or placebo for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. N Engl J Med, 2010; 362: 1675–85.

- Cusi K, Orsak B, Bril F, Lomonaco R, Hecht J, Ortiz-Lopez C, Tio F, Hardies J, Darland C, Musi N, Webb A, Portillo-Sanchez P: Long-term pioglitazone treatment for patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and prediabetes or type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med, 2016; 165: 305–15.

- Athyros VG, Mikhailidis DP, Didangelos TP, Giouleme OI, Liberopoulos EN, Karagiannis A, Kakafika AI, Tziomalos K, Burroughs AK, Elisaf MS: Effect of multifactorial treatment on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in metabolic syndrome: a randomised study. Curr Med Res Opin, 2006; 22: 873-83.

- Vilar-Gomez E, Vuppalanchi R, Gawrieh S, Ghabril M, Saxena R, Cummings OW, Chalasani N: Vitamin E improves transplant-free survival and hepatic decompensation among patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and advanced fibrosis. Hepatology, 2020; 71: 495–509.

- Bril F, Biernacki DM, Kalavalapalli S, Lomonaco R, Subbarayan SK, Lai J, Tio F, Suman A, Orsak BK, Hecht J, Cusi K: Role of vitamin E for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care, 2019; 42: 1481–88.

- Armstrong MJ, Gaunt P, Aithal GP, Barton D, Hull D, Parker R, Hazlehurst JM, Guo K; LEAN trial team; Abouda G, Aldersley MA, Stocken D, Gough SC, Tomlinson JW, Brown RM, Hübscher SG, Newsome PN: Liraglutide safety and efficacy in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (LEAN): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 2 study. Lancet, 2016; 387: 679–90.

- Newsome PN, Buchholtz K, Cusi K, Linder M, Okanoue T, Ratziu V, Sanyal AJ, Sejling AS, Harrison SA; NN9931-4296 Investigators: A placebo-controlled trial of subcutaneous semaglutide in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. N Engl J Med, 2021; 384: 1113–24.

- Eriksson JW, Lundkvist P, Jansson PA, Johansson L, Kvarnström M, Moris L, Miliotis T, Forsberg GB, Risérus U, Lind L, Oscarsson J: Effects of dapagliflozin and n-3 carboxylic acids on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in people with type 2 diabetes: a double-blind randomised placebo-controlled study. Diabetologia, 2018; 61: 1923-1934.

- Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Loomba R, Sanyal AJ, Lavine JE, Van Natta ML, Abdelmalek MF, Chalasani N, Dasarathy S, Diehl AM, Hameed B, Kowdley KV, McCullough A, Terrault N, Clark JM, Tonascia J, Brunt EM, Kleiner DE, Doo E; NASH Clinical Research Network: Farnesoid X nuclear receptor ligand obeticholic acid for non-cirrhotic, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (FLINT): a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet, 2015; 385: 956–65.

- Gawrieh S, Noureddin M, Loo N, Mohseni R, Awasty V, Cusi K, Kowdley KV, Lai M, Schiff E, Parmar D, Patel P, Chalasani N: Saroglitazar, a PPAR-α/γ Agonist, for Treatment of NAFLD: A Randomized Controlled Double-Blind Phase 2 Trial. Hepatology, 2021; 74:1809-1824.

- Harrison SA, Bashir MR, Guy CD, Zhou R, Moylan CA, Frias JP, Alkhouri N, Bansal MB, Baum S, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Taub R, Moussa SE: Resmetirom (MGL-3196) for the treatment of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet, 2019; 394: 2012–24.

- Harrison SA, Bedossa P, Guy CD, Schattenberg JM, Loomba R, Taub R, Labriola D, Moussa SE, Neff GW, Rinella ME, Anstee QM, Abdelmalek MF, Younossi Z, Baum SJ, Francque S, Charlton MR, Newsome PN, Lanthier N, Schiefke I, Mangia A, Pericàs JM, Patil R, Sanyal AJ, Noureddin M, Bansal MB, Alkhouri N, Castera L, Rudraraju M, Ratziu V; MAESTRO-NASH Investigators: A Phase 3, Randomized, Controlled Trial of Resmetirom in NASH with Liver Fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2024; 390:497-509.

- Harrison SA, Neff G, Guy CD, Bashir MR, Paredes AH, Frias JP, Younes Z, Trotter JF, Gunn NT, Moussa SE, Kohli A, Nelson K, Gottwald M, Chang WCG, Yan AZ, DePaoli AM, Ling L, Lieu HD: Efficacy and Safety of Aldafermin, an Engineered FGF19 Analog, in a Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Patients With Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology, 2021; 160: 219-231.e1.

- Loomba, R.; Sanyal, A.J.; Kowdley, K.V.; Bhatt, D.L.; Alkhouri, N.; Frias, J.P.; Bedossa, P.; Harrison, S.A.; Lazas, D.; Barish, R.; Gottwald, M.D.; Feng, S.; Agollah, G.D.; Hartsfield, C.L.; Mansbach, H.; Margalit, M. ; Abdelmalek MF: Randomized controlled trial of the FGF21 analogue Pegozafermin in, N.A.S.H. N Engl J Med 2023; 389: 998-1008.

- Celi, F.S.; Shuldiner, A.R. The role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma in diabetes and obesity. Curr Diab Rep, 2002;2(2):179-185. [Google Scholar]

- Belfort R, Harrison SA, Brown K, Darland C, Finch J, Hardies J, Balas B, Gastaldelli A, Tio F, Pulcini J, Berria R, Ma JZ, Dwivedi S, Havranek R, Fincke C, DeFronzo R, Bannayan GA, Schenker S, Cusi K: A placebo-controlled trial of pioglitazone in subjects with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. N Engl J Med, 2006; 355: 2297–307.

- Marso SP, Bain SC, Consoli A, Eliaschewitz FG, Jódar E, Leiter LA, Lingvay I, Rosenstock J, Seufert J, Warren ML, Woo V, Hansen O, Holst AG, Pettersson J, Vilsbøll T; SUSTAIN-6 Investigators: Semaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med, 2016; 375: 1834–44.

- O’Neil PM, Birkenfeld AL, McGowan B, Mosenzon O, Pedersen SD, Wharton S, Carson CG, Jepsen CH, Kabisch M, Wilding JPH: Efficacy and safety of s\emaglutide compared with liraglutide and placebo for weight loss in patients with obesity: a randomised, double-blind, placebo and active controlled, dose-ranging, phase 2 trial. Lancet, 2018; 392: 637–49.

- Hsiang JC, Wong VW. SGLT2 inhibitors in liver patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2020; 18: 2168–72.e2.

- Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM, Fitchett D, Bluhmki E, Hantel S, Mattheus M, Devins T, Johansen OE, Woerle HJ, Broedl UC, Inzucchi SE; EMPA-REG OUTCOME Investigators: Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med, 2015; 373: 2117–28.

- Jang H, Kim Y, Lee DH, Joo SK, Koo BK, Lim S, Lee W, Kim W: Outcomes of various classes of oral antidiabetic drugs on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. JAMA Intern Med. Published online , 2024.

- Neuschwander-Tetri, B.A. Therapeutic landscape for NAFLD in 2020. Gastroenterology 2020; 158: 1984–98.e3.

- Younossi ZM, Ratziu V, Loomba R, Rinella M, Anstee QM, Goodman Z, Bedossa P, Geier A, Beckebaum S, Newsome PN, Sheridan D, Sheikh MY, Trotter J, Knapple W, Lawitz E, Abdelmalek MF, Kowdley KV, Montano-Loza AJ, Boursier J, Mathurin P, Bugianesi E, Mazzella G, Olveira A, Cortez-Pinto H, Graupera I, Orr D, Gluud LL, Dufour JF, Shapiro D, Campagna J, Zaru L, MacConell L, Shringarpure R, Harrison S, Sanyal AJ; REGENERATE Study Investigators: Obeticholic acid for the treatment of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: interim analysis from a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet, 2019; 394: 2184–96.

- Pockros PJ, Fuchs M, Freilich B, Schiff E, Kohli A, Lawitz EJ, Hellstern PA, Owens-Grillo J, Van Biene C, Shringarpure R, MacConell L, Shapiro D, Cohen DE: CONTROL: a randomized phase 2 study of obeticholic acid and atorvastatin on lipoproteins in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis patients. Liver Int, 2019; 39: 2082–93.

- Loomba R, Noureddin M, Kowdley KV, Kohli A, Sheikh A, Neff G, Bhandari BR, Gunn N, Caldwell SH, Goodman Z, Wapinski I, Resnick M, Beck AH, Ding D, Jia C, Chuang JC, Huss RS, Chung C, Subramanian GM, Myers RP, Patel K, Borg BB, Ghalib R, Kabler H, Poulos J, Younes Z, Elkhashab M, Hassanein T, Iyer R, Ruane P, Shiffman ML, Strasser S, Wong VW, Alkhouri N; for the ATLAS Investigators: Combination therapies including cilofexor and firsocostat for bridging fibrosis and cirrhosis attributable to NASH. Hepatology, 2021; 73: 625–43.

- Hochreuter MY, Dall M, Treebak JT, Barrès R: MicroRNAs in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Progress and perspectives, Mol Metab 2022; 65:101581. Epub 2022 Aug 23.

- 2: M, Sobolewski C, Dolicka D, de Sousa MC, Foti M: miRNAs and NAFLD: from pathophysiology to therapy, Gut 2019;68, 2019.

- Park L, Min D, Kim H, Chung HY, Lee CH, Park IS, Kim Y, Park Y: TAT-enhanced delivery of metallothionein can partially prevent the development of diabetes. Free Radic Biol Med, 2011;51(9):1666-74.

- Min, D.; Kim, H.; Park, L.; Kim, T.H.; Hwang, S.; Kim, M.J.; Jang, S. ; Park Y: Amelioration of diabetic neuropathy by TAT-mediated enhanced delivery of metallothionein, S.O.D. Endocrinology 2012;153(1):81-91.

- Park L, Min D, Kim H, Park J, Choi S, Park Y: The combination of metallothionein and superoxide dismutase protects pancreatic β cells from oxidative damage. Diab Metab Res Rev, 2011; 27(8):802-8.

- Park Y, Kim H, Park L, Min D, Park J, Choi S, Park MH: Effective delivery of endogenous antioxidants ameliorates diabetic nephropathy. PLOS One, 2015;10(6): e0130815.

- Park Y, Cai L: Reappraisal of metallothionein; Clinical applications in patients with diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes, 2018;10(3): 213-231.

| Treatment modality | Specific treatment | Subjects | Effect | Quality of evidences followed | Adverse reactions | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lifestyle-induced weight loss | Weight reduction ≥ 7% | NAFLD (NASH) | Improve disease severity | Several small to moderate RCTs | None | [54] |

| Bariatric surgery | Roux-Y Gastric Bypass | NASH | Resolve NAFLD/NASH and regress fibrosis | Several small to moderate RCTs | Not completely safe due to surgery | [57] |

| Metformin | Metformin | NASH | Improve ALT, did not improve NASH histology | None, because of clear information |

Hypoglycemia, lactic acidosis | [58] |

| Thiazolidinedione | Pioglitazone | NASH (most are non-diabetics) | Improve NAFLD activity score, resolve NASH in some patients | Edema, bone loss | [59] | |

| Pioglitazone | NASH (prediabetes, or T2D) | Improve steatosis, inflammation and fibrosis progression, but did not improve fibrosis | Several small to moderate phase 2 RCTs | Edema, bone loss | [58,60] | |

| Statins | Simvastatin | NASH | Not improve steatosis, fibrosis, necroinflammation | None, because of clear information |

[58,61] | |

| Antioxidants | Vitamin E (800IU/D, 2 yrs) |

NASH | Improve NAFLD acitivity score, resolve definite NASH in some patients | Several small to moderate RCTs | Bleeding, adverse CV outcomes in higher doses | [59,62,63] |

| GLP-1 agonists | Semaglutide 0.4mg/D 72wks |

NASH | Improves hepatic steatosis, necroinflammation | Several small to moderate RCTs | Safe and effective (except nausea, anorexia, constipation) | [64,65] |

| SGLT2 inhibitors | Dapagliflozin 10mg/D 12wks |

NAFLD c T2D | Improves hepatic steatosis, necroinflammation, and liver enzymes | Several small RCTs with non-invasive tests | hypoglycemia, ketoacidosis, urinary tract and genital infections | [66] |

| FXR agonists | Obeticholic acid 25mg/D 72wks | NASH | Improve histology of NASH | Improve liver fibrosis in a phase III RCT | severe adverse reactions (pruritus, LDL increase) limit long-term use | [67] |

| PPARα agonists | Saroglitazar 4mg/D 16wks | NASH | improve dyslipidemia; reduce fat and triglyceride in the liver | Safe and effective | [68] | |

| THRβ agonist | Resmetirom 80mg/D 36wks | NASH | Reduce liver fat content | FDA approved | Safe and effective, but further studies are needed |

[69,70] |

| FGF19 analog | NGM282 1 or 3 mg/D 12wks | NASH | improve histological features and fibrosis score of NASH | Well-tolerated in a phase IIb study | Cholesterol increase, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea. | [71] |

| FGF21 analog | Pegozafermin s.c. weeky of biweekly |

NASH | improve histological features and fibrosis score of NASH | Well-tolerated in a phase Ib/IIa study | Safe and effective | [72] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).