Submitted:

15 February 2025

Posted:

17 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

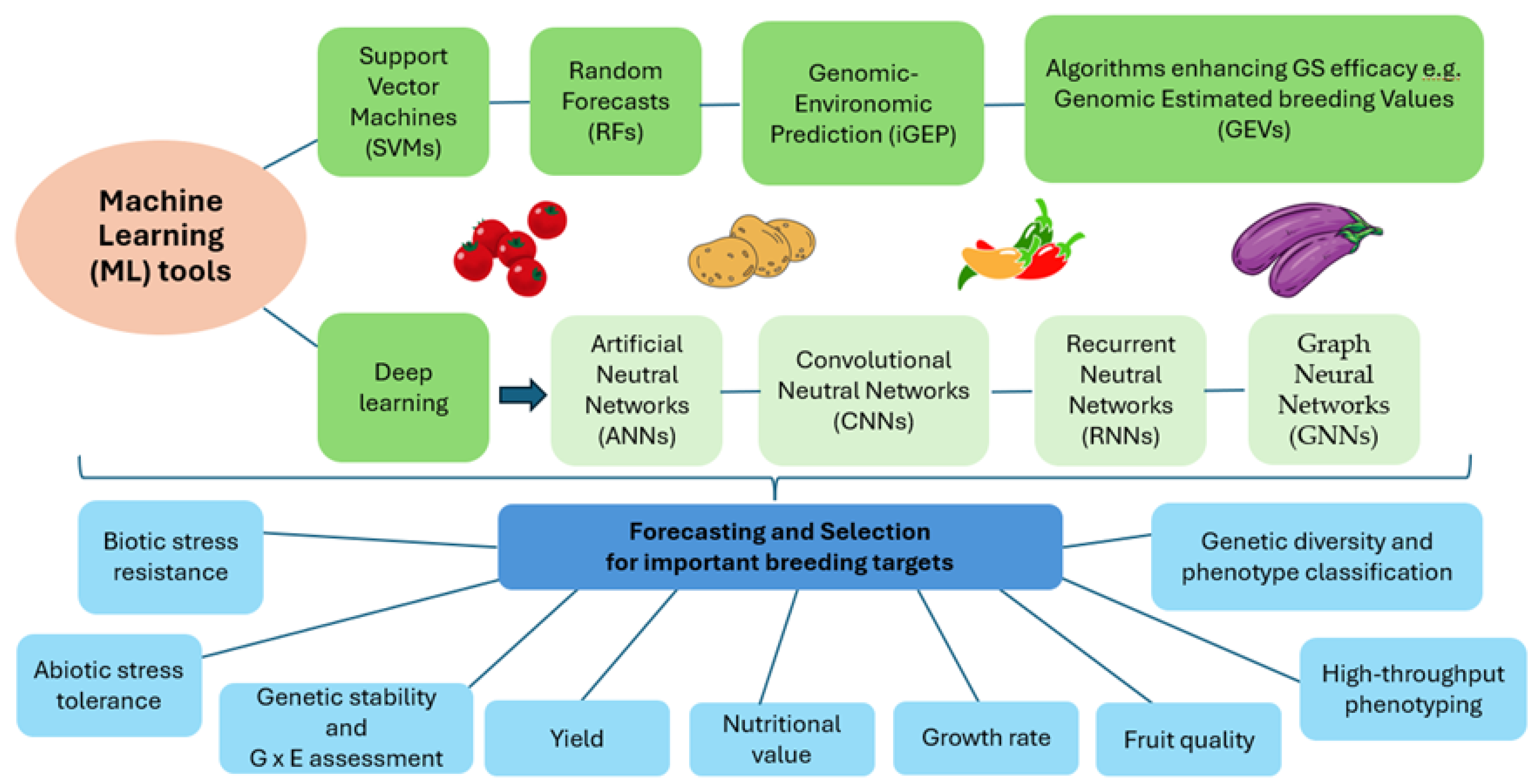

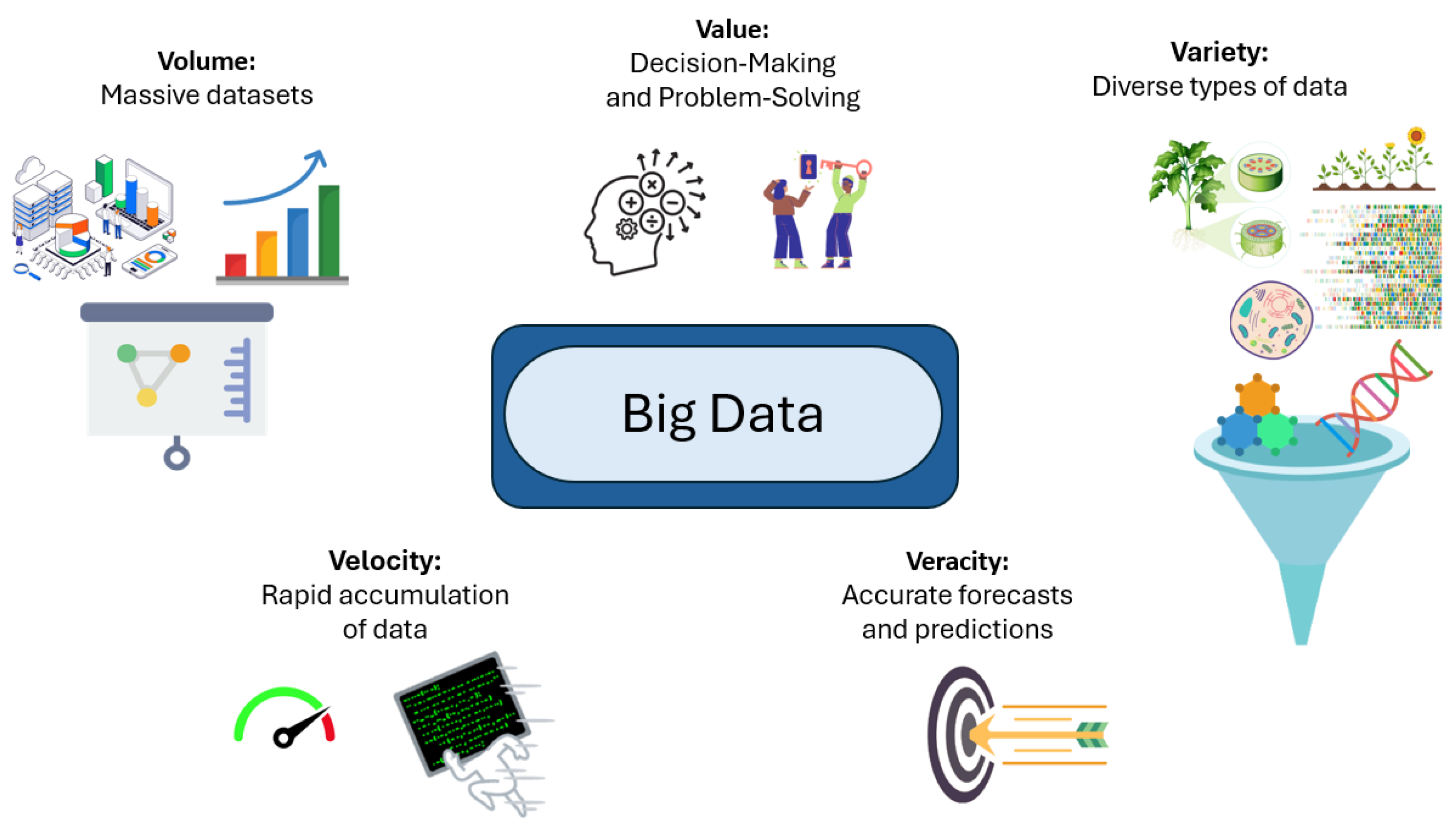

Artificial intelligence (AI), including machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL), has become an essential tool in modern agriculture, revolutionizing traditional practices and offering sustainable solutions to critical challenges, such as climate change, population growth, and resource scarcity. Through advanced algorithms and predictive models, ML and DL enhance precise genomic selection (GS), trait characterization, and the acceleration of crop breeding processes. These technologies facilitate the identification and optimization of key traits, including increased yield, improved quality, pest resistance, and tolerance to extreme climatic conditions. Additionally, ML-driven tools support gene-editing technologies, such as CRISPR-Cas9, contributing to the development of resilient and adaptable crops. By leveraging big data analytics and omic technologies, they provide valuable insights into linking genetic and phenotypic data, fostering the development of sustainable agricultural practices. This research explores the transformative potential of AI, particularly ML and DL, in Solanaceous crops by developing advanced breeding strategies to address challenges posed by climate change and rapid population growth. Furthermore, this study highlights the significant role of these technologies in creating novel crop varieties that are resilient to environmental stressors, while exhibiting superior agronomic and quality traits. AI and its applications, such as ML and DL, contribute to the genetic improvement of Solanaceous crops, strengthening agricultural resilience, ensuring food security, and promoting environmental sustainability.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Applications of Machine Learning in Solanaceaous Crop Breeding

2.1. Tomato

2.1.1. ML Applications for Productivity Monitoring and Yield Prediction

2.1.2. ML Applications for Quality Traits and Seed Selection

2.1.3. ML Applications for Breeding Against Environmental Stressors

2.1.4. ML Applications for Multiple Trait Combinations and GP

2.2. Eggplant

2.2.1. ML Applications for Selecting Superior Plants Based on Yield Prediction

2.2.2. ML Applications for Growth Parameters and Seed Quality

2.2.3. ML Applications for Breeding Against Environmental Stressors

2.2.4. ML Applications for Breeding Multiple Traits

2.3. Potato

2.3.1. ML Applications for Productivity Monitoring and Yield Prediction

2.3.2. ML Applications for Variey Identification and Potato Tuber Quality

2.3.3. ML Applications for Breeding Against Environmental Stressors

2.4. Pepper

2.4.1. ML Applications for Yield Prediction and Favourable Agronomic Traits

2.4.2. ML Applications for Variety Identification, Chemical Clasification, Seed Selection and Fruit Quality

2.4.3. ML Applications for Breeding Against Environmental Stressors

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Monteiro, A.; Santos, S.; Gonçalves, P. Precision Agriculture for Crop and Livestock Farming-Brief Review. Animals 2021, 11, 2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Talaviya, T.; Shah, D.; Patel, N.; Yagnik, H.; Shah, M. Implementation of artificial intelligence in agriculture for optimisation of irrigation and application of pesticides and herbicides. Artificial Intelligence in Agriculture 2020, 4, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dengiz, O.; Alaboz, P.; Saygın, F.; Adem, k.; Yüksek, E. Evaluation of soil quality of cultivated lands with classification and regression-based machine learning algorithms optimization under humid environmental condition. Advances in Space Research 2024, 74, 5514–5529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandelwal, C.; Singhal, M.; Gaurav, G.; Dangayach, G.S.; Meena, M.L. Agriculture Supply Chain Management: A Review (2010–2020). Materials Today: Proceedings 2021, 47, 3144–3153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogili, U.M.R.; Deepak, B.B.V.L. Review on application of drone systems in precision agriculture International Conference on Robotics and Smart Manufacturing. Procedia Computer Science 2018, 133, 502–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, J.; Zhang, X. Data analytics for crop management: A big data view. Journal of Big Data 2022, 9, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, V.; Guo, W.; Chandra, A.; Desai, S.V. Computer Vision with Deep Learning for Plant Phenotyping in Agriculture: A Survey. Advanced Computing and Communications 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, I.K.; Vieira, C.C.; Dias, K.O.G. Using machine learning to combine genetic and environmental data for maize grain yield predictions across multi-environment trials. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2024, 137, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, C.; Zafar, S.; Hasnain, Z.; Aslam, N.; Iqbal, N.; Abbas, S.; Li, H.; Li, J.; Chen, B.; Ragauskas, A.; Abbas, M. Machine and Deep Learning: Artificial Intelligence Application in Biotic and Abiotic Stress Management in Plants. Frontiers in Bioscience-Landmark 2024, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustaka, J.; Moustakas, M. Early-Stage Detection of Biotic and Abiotic Stress on Plants by Chlorophyll Fluorescence Imaging Analysis. Biosensors 2023, 13, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoosefzadeh Najafabadi, M.; Hesami, M.; Eskandari, M. Machine Learning-Assisted Approaches in Modernized Plant Breeding Programs. Genes 2023, 14, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- van Dijk, A.D.J.; Kootstra, G.; Kruijer, W.; de Ridder, D. Machine learning in plant science and plant breeding. iScience 2021, 24, 101890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montesinos López, O.A.; Montesinos López, A.; Crossa, J. Random Forest for Genomic Prediction. In Multivariate Statistical Machine Learning Methods for Genomic Prediction; Springer: Cham, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, S.; Tardaguila, J.; Fernández-Novales, J.; Diago, M.P. Support Vector Machine and Artificial Neural Network Models for the Classification of Grapevine Varieties Using a Portable NIR Spectrophotometer. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0143197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, J.; Xu, Y.; Cheng, Q.; et al. LightGBM: accelerated genomically designed crop breeding through ensemble learning. Genome Biol 2021, 22, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karahan, T.; Nabiyev, V. Plant identification with convolutional neural networks and transfer learning. Pamukkale University Journal of Engineering Sciences 2021, 27, 638–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Ganapathysubramanian, B.; Singh, A.K.; Sarkar, S. Machine learning for high-throughput stress phenotyping in plants. Trends in Plant Science 2016, 21, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, T.; Gill, S.K.; Saini, D.K.; Chopra, Y.; de Koff, J.P.; Sandhu, K.S. A comprehensive review of high throughput phenotyping and machine learning for plant stress phenotyping. Phenomics 2020, 2, 156–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohmed, G.; Heynes, X.; Naser, A.; et al. Modelling daily plant growth response to environmental conditions in Chinese solar greenhouse using Bayesian neural network. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 4379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.G.; Azevedo, A.M.; Siman, L.I.; da Silva, G.H.; Carneiro, C.D.S.; Alves, F.M.; Nick, C. Automation in accession classification of Brazilian Capsicum germplasm through artificial neural networks. Scientia Agricola 2017, 74, 203–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, S.; Ruggieri, V.; Tripodi, P. Editorial: Machine Learning for Big Data Analysis: Applications in Plant Breeding and Genomics. Front. Genet. 2020, 13, 916462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Huang, J.; Wu, Q.; Nguyen, T.; Li, M. Genome-wide association data classification and SNPs selection using two-stage quality-based Random Forests. BMC Genomics 2015, 16 (Suppl. 2), S5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Montesinos-López, O.A.; Montesinos-López, A.; Crossa, J.; Gianola, D.; Hernández-Suárez, C.M.; Martín-Vallejo, J. Multi-trait, Multi-environment Deep Learning Modeling for Genomic-Enabled Prediction of Plant Traits. G3 (Bethesda) 2018, 8, 3829–3840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crossa, J.; Pérez-Rodríguez, P.; Cuevas, J.; Montesinos-López, O.; Jarquín, D.; De Los Campos, G.; Varshney, R.K. Genomic selection in plant breeding: methods, models, and perspectives. Trends in Plant Science 2017, 22, 961–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montesinos-López, A.; Montesinos-López, O.A.; Gianola, D.; Crossa, J.; Hernández-Suárez, C.M. Multi-environment Genomic Prediction of Plant Traits Using Deep Learners With Dense Architecture. G3 Genes|Genomes|Genetics 2018, 8, 3813–3828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, H.; Zheng, H.; Zhang, J.; Olsen, M.S.; Qian, Q. Smart breeding driven by big data, artificial intelligence, and integrated genomic-enviromic prediction. Molecular Plant 2022, 15, 1664–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heslot, N.; Yang, H.P.; Sorrells, M.E.; Jannink, J.L. Genomic selection in plant breeding: a comparison of models. Crop Science 2012, 52, 146–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birhanu, C.; Mekbib, F.; Lule, D.; Bekeko, Z.; Girma, G.; Tirfessa, A.; Ayana, G.; Nida, H.; Mengiste, T. Genotype by environment interactions and stability for grain yield and other agronomic traits in selected sorghum genotypes in Ethiopia. Agrosystems, Geosciences & Environment 2024, 7, e20544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Seo, H.; Jung, M.W. Neural basis of reinforcement learning and decision making. Annu Rev Neurosci 2012, 35, 287–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Moeinizade, S.; Hu, G.; Wang, L. A reinforcement Learning approach to resource allocation in genomic selection. Intelligent Systems with Applications 2022, 14, 200076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoah, P.; Oumarou Mahamane, A.R.; Byiringiro, M.H.; Mahula, N.J.; Manneh, N.; Oluwasegun, Y.R.; Assfaw, A.T.; Mukiti, H.M.; Garba, A.D.; Chiemeke, F.K.; Bernard Ojuederie, O.; Olasanmi, B. Genome editing in Sub-Saharan Africa: a game-changing strategy for climate change mitigation and sustainable agriculture. GM Crops Food 2024, 15, 279–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Angon, P.B.; Mondal, S.; Akter, S.; Sakil, M.A.; Jalil, M.A. Roles of CRISPR to mitigate drought and salinity stresses on plants. Plant Stress 2023, 8, 100169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoj, K.; Ranjan, P.M.; Manish, K.P.; Kumar, S.P.; Abhishek, B.; Baozhu, G.; Rajeev, K.V. Application of CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing for abiotic stress management in crop plants. Frontiers in Plant Science 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Lindhout, P. Domestication and Breeding of Tomatoes: What Have We Gained and What Can We Gain in the Future. Annals of Botany 2007, 100, 1085–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasparini, K.; Figueiredo, Y.G.; Araújo, W.L.; Peres, L.E.; Zsögön, A. De novo domestication in the Solanaceae: advances and challenges. Current Opinion in Biotechnology 2024, 89, 103177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, H.; Nankar, A.N.; Liu, J.; Todorova, V.; Ganeva, D.; Grozeva, S.; Nikoloski, Z. Genomic prediction of morphometric and colorimetric traits in Solanaceous fruits. Horticulture Research 2022, 9, uhac072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palakshappa, A.; Kuthkunja, A.; Aditya, G.; Anvitha, V. Analysis of Leaf Disease Detection in the Solanaceae family plants using Machine Learning Algorithms. 2024, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaji Prabhu, B.V. ARIA: Augmented Reality and Artificial Intelligence enable mobile application for Yield and grade prediction of tomato crops. Procedia Computer Science 2024, 235, 2693–2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darra, N.; Espejo-Garcia, B.; Kasimati, A.; Kriezi, O.; Psomiadis, E.; Fountas, S. Can satellites predict yield? Ensemble machine learning and statistical analysis of Sentinel-2 imagery for processing tomato yield prediction. Sensors 2023, 23, 2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemming, S.; Zwart, F.d.; Elings, A.; Petropoulou, A.; Righini, I. Cherry Tomato Production in Intelligent Greenhouses—Sensors and AI for Control of Climate, Irrigation, Crop Yield, and Quality. Sensors 2020, 20, 6430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belouz, K.; Nourani, A.; Zereg, S.; Bencheikh, A. Prediction of greenhouse tomato yield using artificial neural networks combined with sensitivity analysis. Scientia Horticulturae 2022, 293, 110666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, B.; Kumar, P.P.; Hazra, S.; Dutta, S.; Saha, S.; Roy, S.; Maji, A.; Chakraborty, I.; Chattopadhyay, A.; Hazra, P. Genetic control of important yield attributing characters predicted through machine learning in segregating generations of interspecific crosses of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.). Acta Physiologiae Plantarum 2024, 46, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polder, G.; Blok, P.M.; De Villiers, H.A.C.; Van Der Wolf, J.M.; Kamp, J. Potato Virus Y Detection in Seed Potatoes Using Deep Learning on Hyperspectral Images. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmilovitch, Z.; Ignat, T.; Alchanatis, V.; Gatker, J.; Ostrovsky, V.; Felföldi, J. Hyperspectral imaging of intact bell peppers. Biosystems Engineering 2014, 117, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollazade, K.; Omid, M.; Akhlaghian Tab, F.; Rezaei kalaj, Y.; Mohtasebi, S. Data Mining-Based Wavelength Selection for Monitoring Quality of Tomato Fruit by Backscattering and Multispectral Imaging. International Journal of Food Properties 2015, 18, 880–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Li, W.; Zhang, H.; Li, L. Big data and artificial intelligence-aided crop breeding: Progress and prospects. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duangjit, J.; Causse, M.; Sauvage, C. Efficiency of genomic selection for tomato fruit quality. Molecular Breeding 2016, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Bendary, N.; El-hariri, E.; Hassanien, A.E.; Badr, A. Using machine learning techniques for evaluating tomato ripeness. Expert Systems with Applications 2014, 42, 1892–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez, D.V.; Spetale, F.E.; Nankar, A.N.; Grozeva, S.; Rodríguez, G.R. Machine Learning-Based Tomato Fruit Shape Classification System. Plants 2024, 13, 2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeon, J.; Nguyen, T.T.P.; Kim, M.; et al. Prediction accuracy of genomic estimated breeding values for fruit traits in cultivated tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.). BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappetta, E.; Andolfo, G.; Di Matteo, A.; Barone, A.; Frusciante, L.; Ercolano, M.R. Accelerating tomato breeding by exploiting genomic selection approaches. Plants 2020, 9, 1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, T.; Adem, I. An AI taste ‘connoisseur’ could be the future of crop breeding. Agriculture Dive. 2023, pp. 1–3. https://www.agriculturedive.com/news/an-ai-taste-connoisseur-could-be-thefuture-of-crop-breeding/700086/.

- Ropelewska, E.; Piecko, J. Discrimination of tomato seeds belonging to different cultivars using machine learning. European Food Research and Technology 2022, 248, 685–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Jiang, S.; Tian, Y.; Dong, X.; Xiao, J.; Lu, Y.; Xia, Z. Smart breeding driven by advances in sequencing technology. Modern Agriculture 2023, 1, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, R.H.; Eti, F.S.; Ahmed, R.; Gupta, S.D.; Jhan, P.K.; Islam, T.; Bhuiyan, M.A.R.; Rubel, M.H.; Khayer, A. Drought-responsive genes in tomato: meta-analysis of gene expression using machine learning. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 19374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chele, K.; Tinte, M.; Piater, L.; Dubery, I.; Tugizimana, F. Soil Salinity, a Serious Environmental Issue and Plant Responses: A Metabolomics Perspective. Metabolites 2021, 11, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bupi, N.; Sangaraju, V.K.; Phan, L.T.; Lal, A.; Vo, T.T.B.; Ho, P.T.; Qureshi, M.A.; Tabassum, M.; Lee, S.; Manavalan, B. An Effective Integrated Machine Learning Framework for Identifying Severity of Tomato Yellow Leaf Curl Virus and Their Experimental Validation. Research 2023, 6, 0016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dias, F.; Valente, D.; Oliveira, C.; Dariva, F.; Copati, M. Remote sensing and machine learning techniques for high throughput phenotyping of late blight-resistant tomato plants in open field trials. International Journal of Remote Sensing 2023, 44, 1900–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadade, H.; Kirange, D. Machine Learning Based Identification of Tomato Leaf Diseases at Various Stages of Development. 2021, 814–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.; Lu, J.; Jiang, H. Tomato Leaf Diseases Classification Based on Leaf Images: A Comparison between Classical Machine Learning and Deep Learning Methods. AgriEngineering 2021, 3, 542–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, K.; Morton, M.J.L.; Malbeteau, Y.; Aragon, B.; Al-Mashharawi, S.; Ziliani, M.G.; et al. Predicting biomass and yield in a tomato phenotyping experiment using UAV imagery and random forest. Front. Artif. Intell. 2020, 3, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, S.; Banerjee, S.; Kumar, S.; Saha, A.; Nandy, D.; Hazra, S. Review of applications of artificial intelligence (AI) methods in crop research. Journal of Applied Genetics 2024, 65, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, E.; Matsunaga, H.; Onogi, A.; Kajiya-Kanegae, H.; Minamikawa, M.; Suzuki, A.; Fukuoka, H. A simulation-based breeding design that uses whole-genome prediction in tomato. Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 19454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, H.; Zheng, H.; Zhang, J.; Olsen, M.S.; Varshney, R.K.; Prasanna, B.M.; Qian, Q. Smart breeding driven by big data, artificial intelligence, and integrated genomic-enviromic prediction. Mol Plant 2022, 15, 1664–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ansari, R.; Manna, A.; Hazra, S.; Bose, S.; Chatterjee, A.; Sen, P. Breeding 4.0 vis-à-vis application of artificial intelligence (AI) in crop improvement: an overview. New Zealand Journal of Crop and Horticultural Science 2024, 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martina, M.; De Rosa, V.; Magon, G.; Acquadro, A.; Barchi, L.; Barcaccia, G.; De Paoli, E.; Vannozzi, A.; Portis, E. Revitalizing agriculture: next-generation genotyping and-omics technologies enabling molecular prediction of resilient traits in the Solanaceae family. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1278760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bannari, A.; Morin, D.; Bonn, F.; Huete, A.R. A review of vegetation indices. Remote Sensing Reviews 1995, 13, 95–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taşan, S.; Cemek, B.; Taşan, M.; Cantürk, A. Estimation of eggplant yield with machine learning methods using spectral vegetation indices. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2022, 202, 107367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.; Samsuzzaman Reza, M.N.; Lee, K.-H.; Ahmed, S.; Cho, Y.J.; Noh, D.H.; Chung, S.-O. Image Processing and Support Vector Machine (SVM) for Classifying Environmental Stress Symptoms of Pepper Seedlings Grown in a Plant Factory. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Fortea, E.; García-Pérez, A.; Gimeno-Páez, E.; Sánchez-Gimeno, A.; Vilanova, S.; Prohens, J.; Pastor-Calle, D. A Deep Learning-Based System (Microscan) for the Identification of Pollen Development Stages and Its Application to Obtaining Doubled Haploid Lines in Eggplant. Biology 2020, 9, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sun, C.; Feng, L.; Zhang, Z.; Ma, Y.; Crosby, T.; Naber, M.; Wang, Y. Prediction of End-Of-Season Tuber Yield and Tuber Set in Potatoes Using In-Season UAV-Based Hyperspectral Imagery and Machine Learning. Sensors 2020, 20, 5293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, K.; Kaneko, T.; Iwao, T.; Kitayama, M.; Goto, Y.; Kitano, M. Hybrid AI model for estimating the canopy photosynthesis of eggplants. Photosynthesis Research 2023, 155, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaniyassery, A.; Goyal, A.; Thorat, S.A.; Rao, M.R.; Chandrashekar, H.K.; Murali, T.S.; Muthusamy, A. Association of meteorological variables with leaf spot and fruit rot disease incidence in eggplant and YOLOv8-based disease classification. Ecological Informatics 2024, 83, 102809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lajom, M.P.; Remigio, J.P.; Arboleda, E.; Sacala, R.J.R. Design and Development of Eggplant Fruit and Shoot Borer (Leucinodes Orbonalis) Detector Using Near-Infrared Spectroscopy. Journal of Engineering and Sustainable Development 2024, 28, 439–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cemek, B.; Tasan, S.; Canturk, A. Machine learning techniques in estimation of eggplant crop evapotranspiration. Appl. Water Sci. 2023, 13, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prusty, M.; Panda, N.; Dash, A.K.; Mishra, N. Nutrient Management Modules for Eggplant (Solanum melongena L.): Yield, Quality, Economics, Nutrient Uptake and Post-Harvest Soil Properties. Journal of the Indian Society of Coastal Agricultural Research 2022, 40, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Xu, Y. Applications of deep-learning approaches in horticultural research: A review. Horticulture Research 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador, P.; Gómez, D.; Sanz, J.; Casanova, J.L. Estimation of Potato Yield Using Satellite Data at a Municipal Level: A Machine Learning Approach. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, D.; Salvador, P.; Sanz, J.; Casanova, J.L. Potato Yield Prediction Using Machine Learning Techniques and Sentinel 2 Data. Remote Sens 2019, 11, 1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, D.; Salvador, P.; Sanz, J.; Casanova, J.L. New spectral indicator Potato Productivity Index based on Sentinel-2 data to improve potato yield prediction: a machine learning approach. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2021, 42, 3426–3444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurek, J.; Niedbała, G.; Wojciechowski, T.; Świderski, B.; Antoniuk, I.; Piekutowska, M.; Kruk, M.; Bobran, K. Prediction of Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) Yield Based on Machine Learning Methods. Agriculture 2023, 13, 2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kenawy, E.-S.M.; Alhussan, A.A.; Khodadadi, N.; Mirjalili, S.; Eid, M.M. Predicting Potato Crop Yield with Machine Learning and Deep Learning for Sustainable Agriculture. Potato Res. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Miao, Y.; Gupta, S.K.; Rosen, C.J.; Yuan, F.; Wang, C.; Wang, L.; Huang, Y. Improving Potato Yield Prediction by Combining Cultivar Information and UAV Remote Sensing Data Using Machine Learning. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 3322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulibali, Z.; Cambouris, A.N.; Parent, S.-É. Cultivar-specific nutritional status of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) crops. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0230458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Zhou, J.; Fan, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z. Potato Leaf Area Index Estimation Using Multi-Sensor Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) Imagery and Machine Learning. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.A.; Khan, A.A.; Hasan, M.M.; Rahman, M.S.; Habib, M.T. Deep Learning Modeling for Potato Breed Recognition. IEEE Trans. AgriFood Electron. 2024, 2, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizi, A.; Abbaspour-Gilandeh, Y.; Nooshyar, M.; Afkari-Sayah, A. Identifying Potato Varieties Using Machine Vision and Artificial Neural Networks. International Journal of Food Properties 2015, 19, 618–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Westergaard, J.C.; Sundmark, E.H.R.; Bagge, M.; Liljeroth, E.; Alexandersson, E. Automatic late blight lesion recognition and severity quantification based on field imagery of diverse potato genotypes by deep learning. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2021, 214, 106723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, K.M.; Townsend, P.A.; Herrmann, I.; Gevens, A.J. Investigating potato late blight physiological differences across potato cultivars with spectroscopy and machine learning. Plant Sci. 2020, 295, 110316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparajita Sharma, R.; Singh, A.; Dutta, M.K.; Riha, K.; Kriz, P. Image processing based automated identification of late blight disease from leaf images of potato crops. In Proceedings of the 2017 40th International Conference on Telecommunications and Signal Processing (TSP); pp. 758–762. [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.A.; Talukder, K.H. Detection of Potato Disease Using Image Segmentation and Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Wireless Communications Signal Processing and Networking (WiSPNET), Chennai, India; IEEE, 2020; pp. 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sholihati, R.A.; Sulistijono, I.A.; Risnumawan, A.; Kusumawati, E. Potato Leaf Disease Classification Using Deep Learning Approach. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Electronics Symposium (IES), Surabaya, Indonesia; IEEE, 2020; pp. 392–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarik, M.I.; Akter, S.; Mamun, A.A.; Sattar, A. Potato Disease Detection Using Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 2021 Third International Conference on Intelligent Communication Technologies and Virtual Mobile Networks (ICICV), Tirunelveli, India; IEEE, 2021; pp. 800–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, J.; Khan, I.; Ali, G.; Almotiri, S.H.; AlGhamdi, M.A.; Masood, K. Multi-Level Deep Learning Model for Potato Leaf Disease Recognition. Electronics 2021, 10, 2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasalkar, J.; Gorde, G.; More, C.; Memane, S.; Gaikwad, V. Potato Leaf Disease Detection using Machine Learning. Curr. Agric. Res. J. 2023, 11, 949–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, M.-Y.; Gonzalez Viejo, C.; Tongson, E.; Wiechel, T.; Taylor, P.W.J.; Fuentes, S. Early detection of Verticillium wilt of potatoes using near-infrared spectroscopy and machine learning modeling. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhere, H.; Jariwala, V.; Sharma, A.; Nemade, V. Potato Plant Leaf Disease Classification Using Deep CNN, in: Potato Plant Leaf Disease Classification Using Deep CNN. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference, ESDA 2022; Springer: Singapore; pp. 367–378. [CrossRef]

- Sugiura, R.; Tsuda, S.; Tsuji, H.; Murakami, N. Virus-Infected Plant Detection in Potato Seed Production Field by UAV Imagery. In Proceedings of the 2018 Detroit, Michigan, 29 July–1 August 2018; American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffel, L.M.; Delparte, D.; Edwards, J. Using Support Vector Machines classification to differentiate spectral signatures of potato plants infected with Potato Virus Y. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2018, 153, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boguszewska-Mańkowska, D.; Ruszczak, B.; Zarzyńska, K. Classification of Potato Varieties Drought Stress Tolerance Using Supervised Learning. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapajne, J.; Vojnović, A.; Vončina, A.; Žibrat, U. Enhancing Water-Deficient Potato Plant Identification: Assessing Realistic Performance of Attention-Based Deep Neural Networks and Hyperspectral Imaging for Agricultural Applications. Plants 2024, 13, 1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozada, D.N.; Sandhu, K.S.; Bhatta, M. Ridge regression and deep learning models for genome-wide selection of complex traits in New Mexican Chile peppers. BMC Genomic Data 2023, 24, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabanci, K.; Fatih Aslan, M.; Ropelewska, E.; Fahri Unlersen, M. A convolutional neural network-based comparative study for pepper seed classification: Analysis of selected deep features with support vector machine. J. Food Process Eng. 2021, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtulmuş, F.; Kavdir, I.; Alibaş, İ. Classification of pepper seeds using machine vision based on neural network. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2016, 9, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, K.; Li, L.; Yang, L.; Wang, J.; Sun, Q. Selection for high quality pepper seeds by machine vision and classifiers. Journal of Integrative Agriculture 2016, 17, 1999–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Meraz, M.; Méndez-Aguilar, R.; Hidalgo-Martínez, D.; Villa-Ruano, N.; Zepeda-Vallejo, L.G.; Vallejo-Contreras, F.; Hernández-Guerrero, C.J.; Becerra-Martínez, E. Experimental races of Capsicum annuum cv. jalapeño: Chemical characterization and classification by 1H NMR/machine learning. Food Res. Int. 2020, 138, 109763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dissanayake, A.; Rajapaksha, I.; Gunarathna, R.; Jayasinghe, S.; De Silva, H.; Hettiarachchi, S. Detection of Diseases and Nutrition in Bell Pepper. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Advancements in Computing (ICAC), Colombo, Sri Lanka; IEEE, 2023; pp. 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, I.; Islam, M.A.; Roy, K.; Rahaman, M.M.; Shohan, A.A.; Islam, M.S. Classifying Pepper Disease based on Transfer Learning: A Deep Learning Approach. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Applied Artificial Intelligence and Computing (ICAAIC), Salem, India; 2022; pp. 620–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fumia, N.; Kantar, M.; Lin, Y.; Schafleitner, R.; Lefebvre, V.; Paran, I.; Börner, A.; Diez, M.J.; Prohens, J.; Bovy, A.; Boyaci, F.; Pasev, G.; Tripodi, P.; Barchi, L.; Giuliano, G.; Barchenger, D.W. Exploration of high-throughput data for heat tolerance selection in Capsicum annuum. Plant Phenome J. 2023, 6, e20071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ataş, M.; Yardimci, Y.; Temizel, A. A new approach to aflatoxin detection in chili pepper by machine vision. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2012, 87, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J. Breeding 5.0: AI-Driven Revolution in Designed Plant Breeding. Molecular Plant Breeding 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).