1. Introduction

During long-term co-evolution, insects and their endosymbiotic bacteria have established close mutualistic relationships [

1]. Endosymbiotic bacteria not only regulate the host insect nutritional and reproductive metabolism but also assist in resisting biotic and abiotic stresses, enhancing resistance to chemical pesticides, and improving adaptability to host plants [

2,

3]. The association between phytophagous insects and their endosymbiotic bacteria affects various interactions between insects and plants, such as expanding the range of host plants [

4], or promoting host plant utilization by altering plant chemical composition [

5]. However, little is known about the role of endosymbiotic bacteria in manipulating plant defense responses. In the long-term co-evolutionary processes between insects and plants, plants have continuously evolved various defense mechanisms to resist insect feeding, while insects have developed counter-defense strategies to overcome plant defenses. In the arms race of plant defense and insect counter-defense during co-evolution, the exact role of endosymbiotic bacteria remained unclear. Different studies have different conclusions. Some studies suggested that endosymbiotic bacteria induced and activated plant defense responses, while others found that they inhibited plant defense responses, and some indicated that they have no significant effect on plant defense responses. At the same time, the specific mechanism by which endosymbiotic bacteria mediate host-plant defense responses is also unclear, which greatly restricts our in-depth understanding of the interaction between insects and plants.

Frago et al. (2012) suggested that endosymbiotic bacteria might play a hidden role as "executor" [

6]. Giron et al. (2014) and Groen et al. (2016) indicated that endosymbiotic bacteria within insects play a significant role in suppressing plant defense responses, both direct and indirect [

7,

8]. Chung et al. (2013) found that the

Colorado potato beetle inhibited plant defense responses through symbiotic bacteria present in its oral secretions, facilitating the growth of its host beetle [

9]. Su et al. (2015) found that the infection of

Bemisia tabaci with the endosymbiont

Hamiltonella defensa suppressed the JA mediated defense responses in tomatoes, enhancing the growth and development of

whiteflies [

10]. Staudacher et al. (2017), using quantitative RT-PCR to detect the expression levels of defense marker genes such as PPO, POD, LOX, and AOS, as well as the accumulation of plant hormones JA and SA, showed that while different combinations of

Wolbahia,

Cardinium, and

Spiroplasma altered plant defense parameters and affected the performance of

Tetranychus urticae, there was no causal relationship between the two, indicating that endosymbionts do not influence the plants induced defense mechanisms [

11]. Li et al. (2019) found that the infection with

H. defensa inhibited the expression of key genes in the SA and JA mediated defense pathways in wheat, inhibited the activity of protective defense enzymes (PPO, POD), and enhanced the activity of detoxification enzyme of the host

Sitobion avenae [

12]. Zhu et al. (2020) reported that infection with

Wolbachia and

Spiroplasma in

T. truncatus altered the activity of defense enzymes and the expression of defense genes in tomatoes, but had no significant effect on the accumulation of JA and SA, suggesting that this regulatory effect mainly occurs downstream of JA and SA synthesis, and there is no antagonistic relationship between JA and SA. The above studies mainly focused on detecting the expression of plant defense marker genes, plant defense enzyme activities, or the accumulation of plant hormones JA and SA [

13]. However, the limitation of these studies lies in the inability of single molecule research to explain complex biological responses, which are often the result of interactions among genes, proteins, and metabolites. Omics technologies can identify biomolecules as many as possible in complex samples. This study aims to investigate the role of endosymbionts in mediating plant defense using metabolomics, providing new insights and methodologies for exploring the molecular mechanisms of endosymbiont-induced plant defenses.

Xinjiang is the largest cotton-producing region in the world. The Turkestan mite (

Tetranychus turkestani), belonging to the order Trombidiformes, family Tetranychidae, and genus Tetranychus, is the dominant pest species in Xinjiang cotton fields [

14].

Wolbachia is a widespread symbiotic bacteria found in arthropods, classified under the class α-Proteobacteria, order Rickettsiales, family Anaplasmataceae, and genus

Wolbachia [

15]. It can infect up to 70% of arthropod species [

16], causing various reproductive regulations in hosts, such as cytoplasmic incompatibility [

17]. In this study,

T. turkestani strains infected and uninfected with

Wolbachia were obtained through parthenogenetic backcrossing and antibiotic screening, which were then used to infest cotton leaves. Metabolomics was used to identify significantly differential metabolites in cotton leaves. The functions and pathways of key differential metabolites, especially the role of secondary metabolites in plant chemical defense, were further validated. This research aims to systematically elucidate the molecular mechanisms of endosymbiont-induced plant defense from a metabolic perspective, contributing to the expansion and enrichment of theories on insect-plant co-evolution.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials

Cotton (Gossypium hirsutum, variety: Zhongmian 36) was planted in a greenhouse (25/18℃ day/night temperature, 16L/8D photoperiod, 50-60% relative humidity). Experiments involving plants were conducted after a seven day acclimatization period in a climate chamber (25℃, 16L/8D photoperiod, 60% relative humidity). T. turkestani mites were collected in June 2023 from the experimental fields of the College of Agriculture, Shihezi University. They were reared on cotton in a light incubator (25℃, 16L/8D photoperiod, 60% relative humidity) without exposure to any pesticides.

2.2. Detection of Wolbachia Infection in T. turkestani

The total DNA of

T. turkestani was extracted following the method described by Yang Kang et al. [

18]. Specific primers targeting the

wsp gene of

Wolbachia were designed (see Appendix Table A1). The PCR reaction volume was 25 μL, containing 2.0 μL DNA template, 14.8 μL ddH

2O, 2.5 μL 10 x buffer, 2.0 μL dNTPs, 1.5 μL MgCl2, 0.2 μL Taq polymerase, and 0.5 μL each of forward and reverse primers (20 mmol/L). The PCR conditions were as follows: pre-denaturation at 94 ℃ for 2 min; 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 ℃ for 30 s, annealing at 55℃ for 45 s, and extension at 72 ℃ for 45 s, followed by a final extension at 72 ℃ for 5 min. PCR products (15-20 μL) were analyzed using 1% agarose gel electrophoresis.

2.3. Screening of Mite Strains with Different Wolbachia Infection Status

Cultivation of 100%

Wolbachia-Infected strains: The parthenogenetic backcrossing was employed to cultivate strains fully infected with

Wolbachia. Fresh, intact kidney bean leaves ware placed in petri dishes (9 cm diameter) containing sponges. The leaves were divided into 3-5 compartments of approximately equal area using moist, absorbent cotton strips. A single unmated female deutonymph from the laboratory strain was placed in each compartment for parthenogenetic reproduction to produce male offspring. Once the eggs developed into adult males, they were backcrossed with their mother. After two days of backcrossing, the mother was transferred to a new compartment to lay eggs. Seven days later, the mother was tested for

Wolbachia infection via PCR. The offspring of

Wolbachia-infected females were subjected to the same process for four to five generations. Subsequently, 50 adult female offspring were tested by PCR, and strains showing 100%

Wolbachia infection were used for experiments [

19].

Cultivation of

Wolbachia-Uninfected Strains:Bean leaves were soaked in 0.1% tetracycline solution for 24 hours and then used to feed newly hatched doubly infected larval mites. PCR was performed on 50 adult female mites per generation to detect

Wolbachia infection. Strains showing complete absence of infection were considered

Wolbachia-uninfected. Prior to experimentation, these uninfected strains were reared for four to five generations without tetracycline to eliminate potential adverse effects of the antibiotic [

20].

2.4. Infection Process of Mite Strains with Different Wolbachia Infection Status on Host Plants

The selected T. turkestani strains were acclimated to cotton plants. Five 21-day-old cotton plants were selected for each strain, with three leaves per plant. Mites aged 3 ± 1 days were placed on the experimental cotton leaves, with 30 mites per leaf for a 7 day infection period. Moist, absorbent cotton was used to block mite escape from the petioles. The number of adult mites was checked daily, and any escaped or dead mites were replenished promptly replaced. After 7 days of infection, cotton leaves were collected. Prior to sampling, mites were gently removed from the leaf surfaces using fine brushes, ensuring no residual mite mouthparts or other body parts remained on the leaves. The leaves were quickly excised (within 5 seconds) using sterilized scissors, immediately flash frozen in liquid nitrogen for 10 minutes, and then transferred to a -80℃ ultra low temperature freezer for storage, which were then used for metabolomics sequencing analysis.

2.5. Metabolomics Sequencing of Host Plants

Cotton leaves infected by Wolbachia-infected mites were labeled as YJ, and those infected by Wolbachia-uninfected mites were labeled as WJ. After gradual thawing at 4℃, appropriate amounts of samples were mixed with pre-cooled methanol/acetonitrile/water solution (2:2:1, v/v), vortexed, and ultrasonicated at low temperature for 30 min, and left to stand at -20℃ for 10 min. The samples were centrifuged at 14,000 g at 4 ℃ for 20 min. The supernatant was collected and vacuum-dried. For mass spectrometry analysis, the dried samples were reconstituted with 100 μL acetonitrile-water solution (1:1, v/v), vortexed, centrifuged at 14,000 g at 4 ℃ for 15 min, and the supernatant was used for analysis. Samples were separated using an Agilent 1290 Infinity LC ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC) system equipped with a HILIC column. The primary and secondary spectra were collected using an AB Triple TOF 6600 mass spectrometer (AB SCIEX). Mass spectrometry analysis was performed in both positive and negative electrospray ionization (ESI) modes. The raw data were converted to .mzXML format using ProteoWizard, and XCMS software was used for peak alignment, retention time correction, and peak area extraction. The extracted data were subjected to metabolite structure identification, data preprocessing, and experimental data quality evaluation, followed by data analysis. Metabolites with a variable importance in projection (VIP) > 1 and a p value < 0.05 were considered as differential metabolites.

2.6. Transcriptomic Sequencing of T. turkestani

Sample Collection and Numbering: Uninfected strains of T. turkestani (free of Wolbachia infection) were selected. Sample of eggs (E), larvae (L), nymphs (N), adult females (A_F), and adult males (A_M) were collected into 1.5 mL sterile centrifuge tubes, with approximately 50 mg per tube, in three replicates. For the Wolbachia-infected strains, samples of eggs (E_W), larvae (L_W), nymphs (N_W), adult females (A_W_F), and adult males (A_W_M) were similarly collected. The collected samples were immediately placed in liquid nitrogen and then rapidly transferred to a -80 ℃ ultra-low temperature freezer for storage.

Total RNA was extracted following the protocols provided by Invitrogen Trizol Reagent. Libraries were prepared using 1 µg of total RNA. Poly(A) mRNA was isolated using Oligo(dT) beads and fragmented using divalent cations. cDNA synthesis was performed using the NEBNext UltraTM RNA Library Prep Kit (NEB, Ipswich, MA, USA). The purified double-stranded cDNA was end-repaired, dA tailed, and ligated with adapters. Size selection of adaptor-ligated DNA was performed using DNA Clean Beads. PCR amplification of each sample was carried out using P5 and P7 primers, and PCR products were verified. The libraries, indexed with different barcodes, were multiplexed and loaded onto the Illumina HiSeq 3000 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) for sequencing, following the manufacturer's instructions, using a 2×150 paired-end (PE) configuration. Quality control (QC) was performed using fastp. High-quality data were subjected to downstream analysis. QC statistics, including total reads, raw data, raw depth, error rates, and Q30 percentages were calculated. Clean reads were aligned to the T. urticae reference genome using Hisat2 (v2.2.1) software. Gene and isoform counts were estimated using HTSeq (v0.6.1), and FPKM (fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads) values were calculated based on gene length. Differential gene expression analysis was conducted using DESeq2 (V1.26.0) with the following criteria: |log2FoldChange|>1 and p-value< 0.05.

2.7. Influence of Wolbachia on the Lifespan and Developmental Duration of Mites

Influence of Wolbachia on the Lifespan of Mites: Due to the susceptibility of male mites to drowning during rearing, only the lifespan of female mites was observed. A total of 90 quiescent stage III female mites were selected. After 12 hours, newly hatched females were removed, and females hatched within the next 8 hours were transferred to fresh leaves. Four females of the same infection status were placed on each leaf, with 13 leaves per infection status, totaling 52 females per strain. To ensure adequate nutrition, mites were transferred to fresh leaves every three days. The number of dead females was recorded daily, and deceased females were removed until all mites had died. Survival rates at different stages were compared using the Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank test in SPSS 20.0.

Influence of Wolbachia on the Developmental Duration of Mites: Infected and uninfected female mites were placed on fresh leaves to oviposit for 8 hours. After eight hours, the eggs were transferred to fresh leaves partitioned with absorbent paper, with one egg per section. Development stages were observed every 12 hours, and the duration of each instar was recorded. Since the development time data did not follow a normal distribution after transformation, non-parametric Mann-Whitney U tests were conducted for statistical analysis using SPSS 20.0.

2.8. Comparison of Leaf Damage Area

After seven days of infection, all mites and eggs were removed from the cotton leaves. The leaves were flattened using a thin glass plate, and images were captured with a Nikon camera to assess the feeding damage caused by spider mites. The damaged leaf area (mm

2) was estimated using the "Compu Eye, Leaf & Symptom Area" software [

21].

3. Results

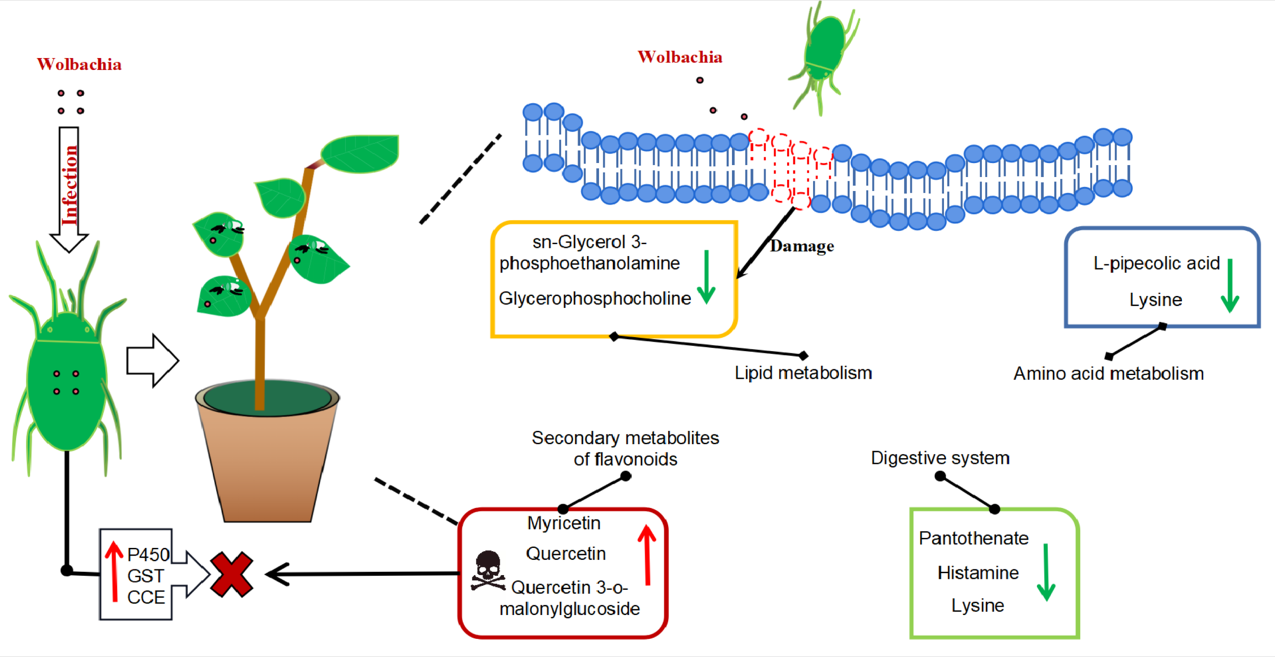

3.1. Phenotypic Analysis of Cotton Leaves Infected by Different Mites

The impact of

Wolbachia within mites on the phenotypic damage of cotton leaves is shown in

Figure 1. There were significant differences in the extent and type of damage caused by mites infected and uninfected with

Wolbachia after feeding on cotton. Mites infected with

Wolbachia caused rust-colored necrotic spots on the leaf surface, resembling symptoms of plant pathogens (

Figure 1A), whereas mites without

Wolbachia infection caused chlorotic spots on the leaf surface (

Figure 1B). However, there was no significant differences in the damaged leaf area between the

Wolbachia-infected and uninfected mite strains (

Figure 1C).

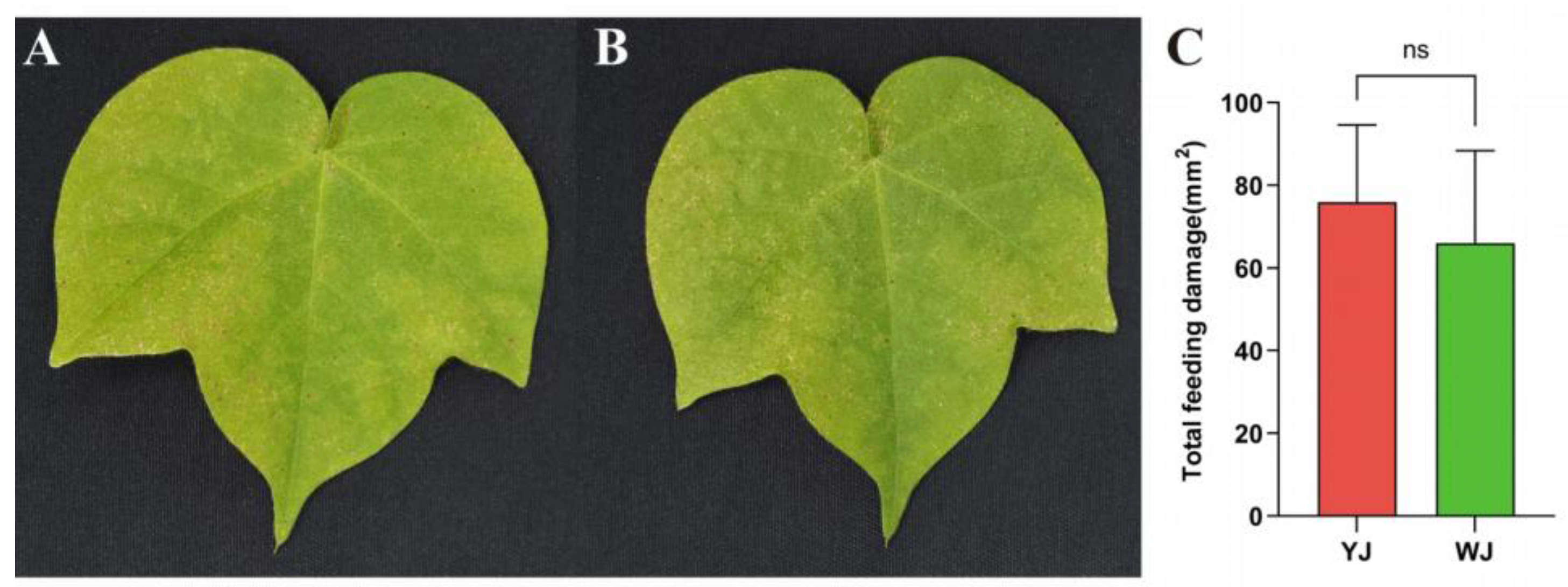

3.2. Metabolomic Analysis of Cotton Leaves Infected by Different Mites

Non-targeted metabolomic sequencing was performed on cotton leaves infected by

Wolbachia-infected (YJ) and uninfected (WJ) mites. To evaluate the metabolic differences between YJ and WJ and the variability within each sample, principal component analysis (PCA) was conducted on the metabolites in both positive and negative ion modes. The analysis showed that the contribution rates of PCA1 and PCA2 were 57.6% in positive ion mode and 60.4% in the negative ion mode (

Figure 2A, 2B). In both modes, the samples clustered within the 95% confidence interval, and samples from different groups were distinctly separated, indicating significant metabolic differences between groups. The QC overlap indicated high similarity and good quality among samples. Orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) was performed on the comparative groups. The OPLS-DA score plots showed that the R2 values in both positive and negative ion modes were greater than 0.71, and the Q2 values were greater than 0.67, indicating good predictive ability of the model. Samples clustered within the 95% confidence interval, with clear separation between groups (

Figure 2C, 2D). LC-MS/MS sequencing identified a total of 1532 differential metabolites, with 883 metabolites identified in positive ion mode and 649 metabolites in negative ion mode (

Figure 2E).

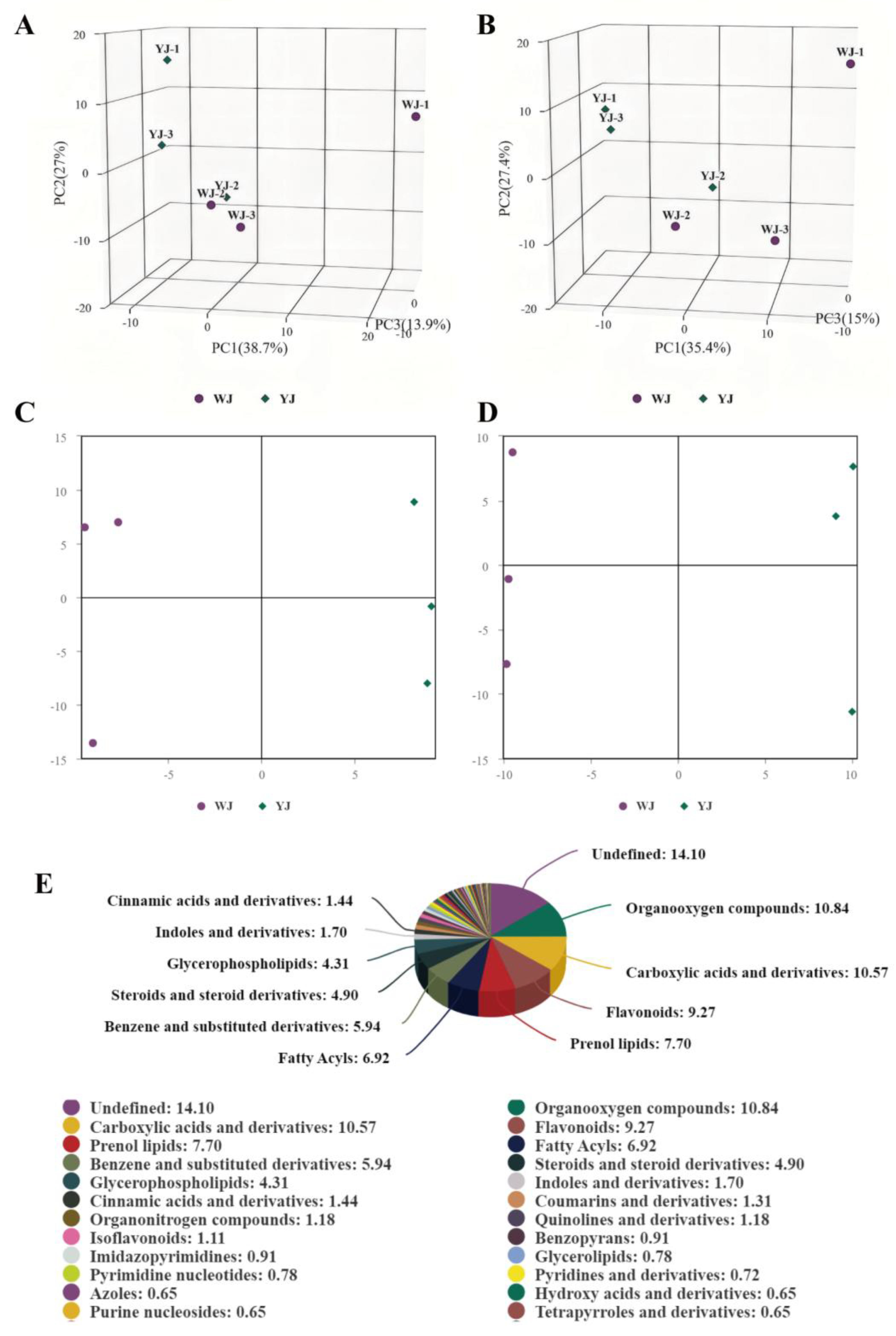

Significant differential metabolites were identified based on the variable importance in projection (VIP) values from the OPLS-DA model and student’s t-test p-values. Metabolites with VIP > 1 and p < 0.05 were considered significantly different. A total of 55 differential metabolites were identified using fold change (FC) thresholds of >1.5 or <0.67 (

Figure 3A, 3B), including 33 in positive ion mode and 22 in negative ion mode (

Figure 3C, 3D) (see Appendix Table A2). Differential compounds were classified, revealing that the metabolites differing between YJ and WJ samples were primarily lipids (13 types), phenylpropanoids and polyketides (13 types), organic heterocyclic compounds (7 types), organic acids and derivatives (7 types), organic oxygen compounds (2 types), organic nitrogen compounds (1 type), lignans, neolignans and related compounds (1 type), and benzene derivatives (1 type). Hierarchical clustering analysis of YJ vs WJ samples showed that, in positive ion mode, 19 metabolites were upregulated and 14 were downregulated in the YJ group. In negative ion mode, 16 metabolites were upregulated and 6 were downregulated in the YJ group (

Figure 3E,

Figure 3F).

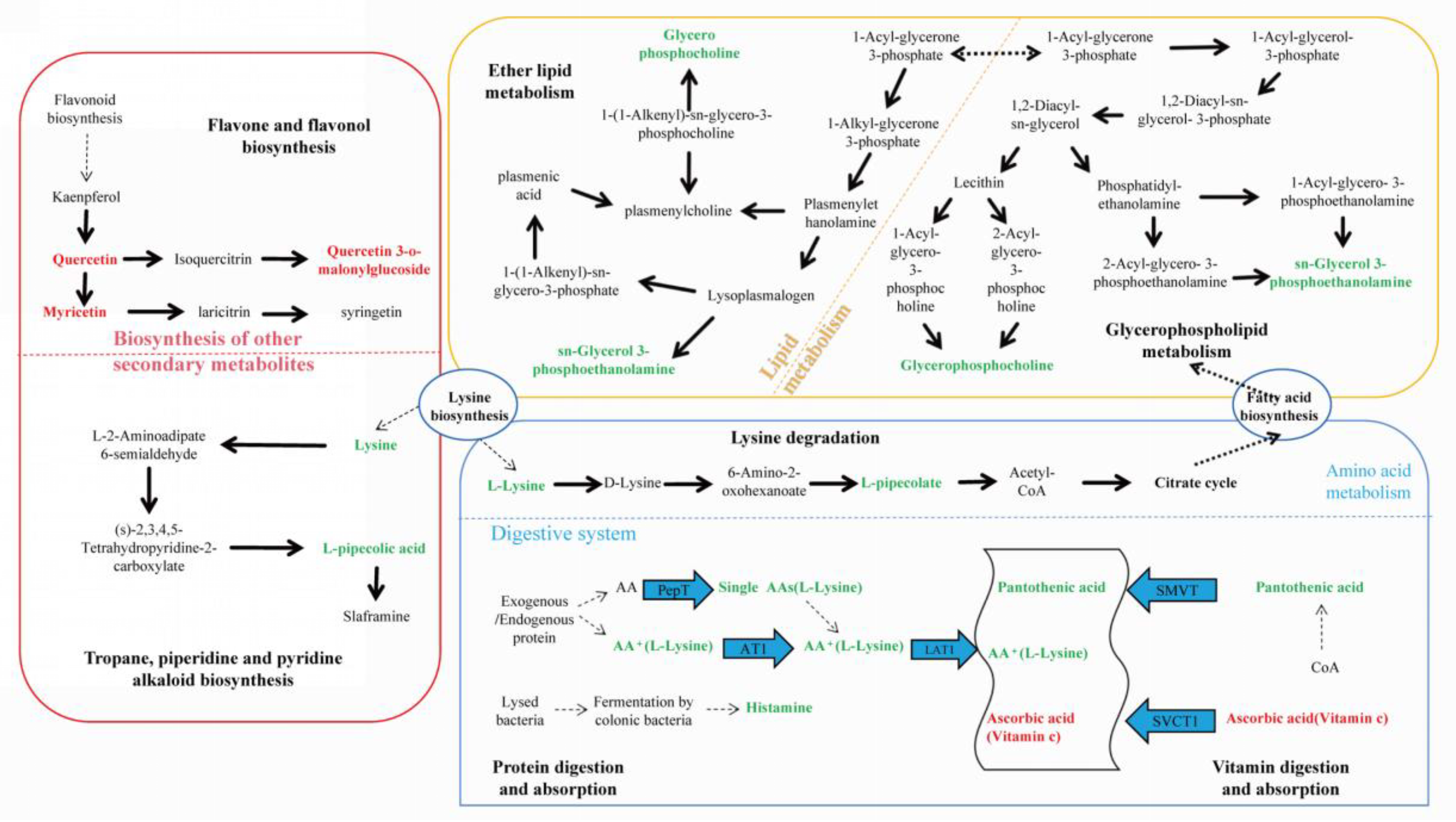

In cotton leaves infected with Wolbachia, lysine was downregulated, which might have led to a deficiency in the essential amino acid lysine required by the cotton spider mite, negatively affecting its lifespan and fitness. L-malic acid, known to reduce fat content in insects, was upregulated with a fold change of 9.25 in Wolbachia infected cotton leaves, potentially decreasing the essential fat content required by the spider mite, impairing its fat storage processes and compromising its survival. Glycerophosphocholine (GPC) was significantly downregulated with a fold change of 0.23, and sn-glycerol-3-phosphoethanolamine (PE) was significantly downregulated with a fold change of 0.06. These metabolites are associated with the formation of cellular membranes, and their downregulation suggested that Wolbachia might have compromised the integrity and function of the plant cell membrane structures, thereby assisting the host spider mite in better accessing the intracellular sap of plant cells. Among secondary metabolites, flavonoid such as quercetin and myricetin were significantly upregulated with fold changes of 4.4 and 1.83, respectively. The upregulation of these secondary metabolites might have enhanced the defensive capability of cotton leaves against spider mite infection.

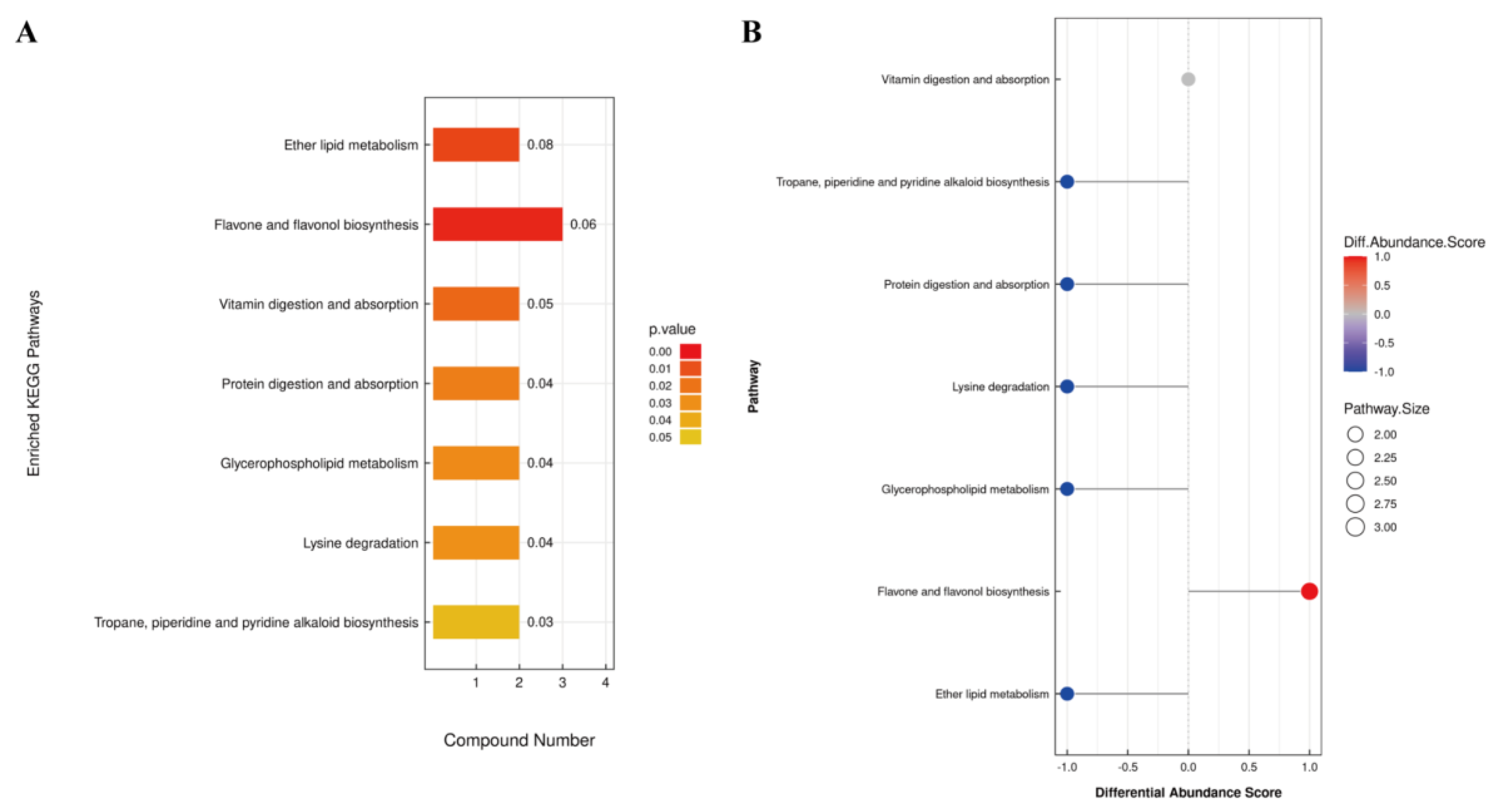

KEGG pathway analysis of differential metabolites identified 15 metabolites enriched in 7 pathways (

Figure 4). Among these, ether lipid metabolism, flavonoid and flavonol biosynthesis pathways exhibited extremely significant differences in YJ vs WJ comparison (p < 0.01). The protein digestion and absorption pathway enriched 2 metabolites: histamine and lysine. The flavonoid and flavonol biosynthesis pathway enriched 3 metabolites: quercetin, myricetin, and quercetin 3 – O - malonylglucoside. The vitamin digestion and absorption pathway enriched 2 metabolites: pantothenic acid and vitamin C. The tropane, piperidine, and pyridine alkaloid biosynthesis pathway enriched lysine and pipecolic acid. The lysine degradation pathway enriched lysine and pipecolic acid as well. Both glycerophospholipid metabolism and ether lipid metabolism pathways enriched (GPC) and (PE).

Among the 15 differential metabolites, lysine was annotated in three pathways: lysine degradation, protein digestion and absorption, and tropane, piperidine, and pyridine alkaloid biosynthesis. GPC and PE were annotated in both glycerophospholipid metabolism and ether lipid metabolism pathways.

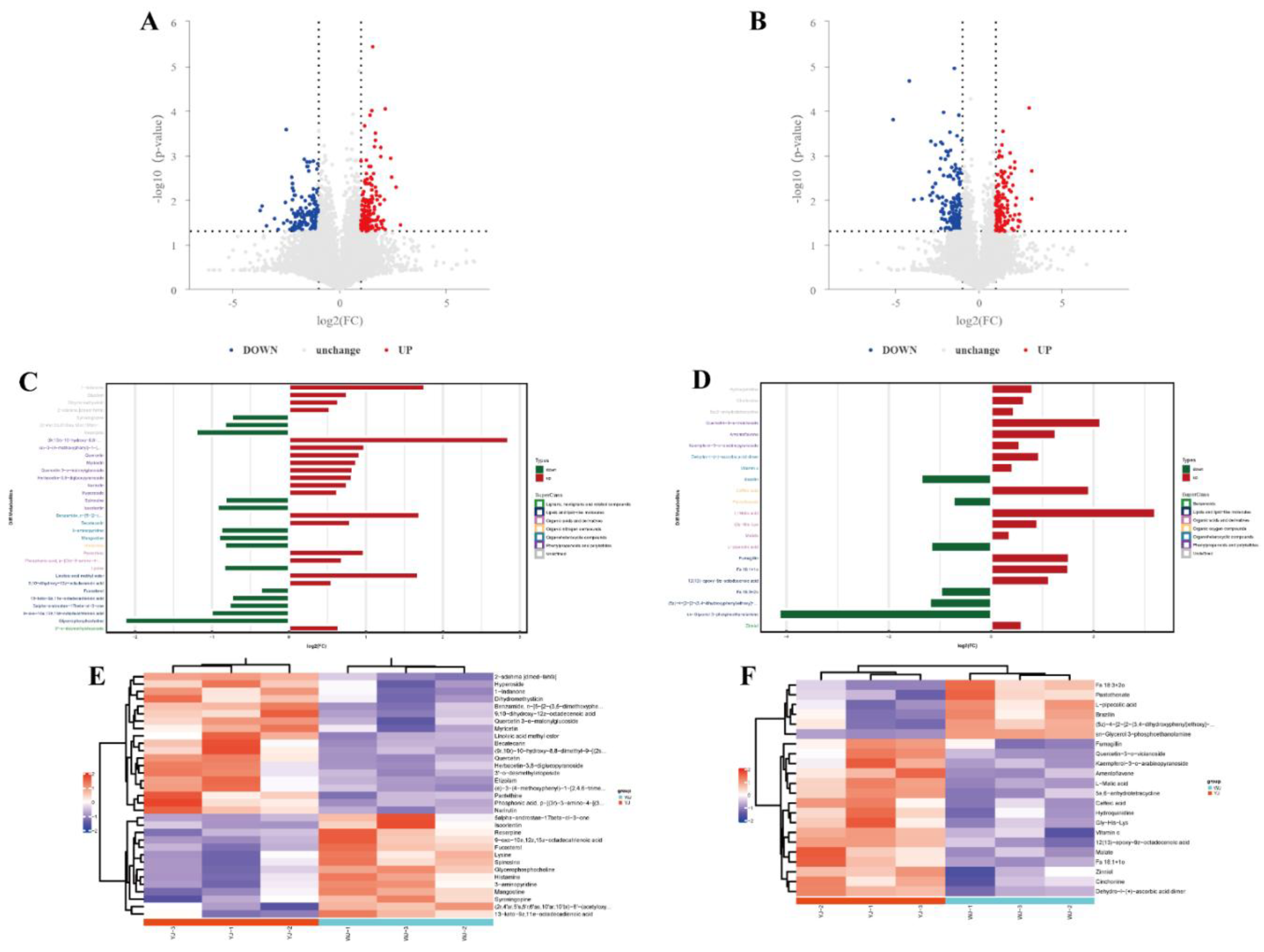

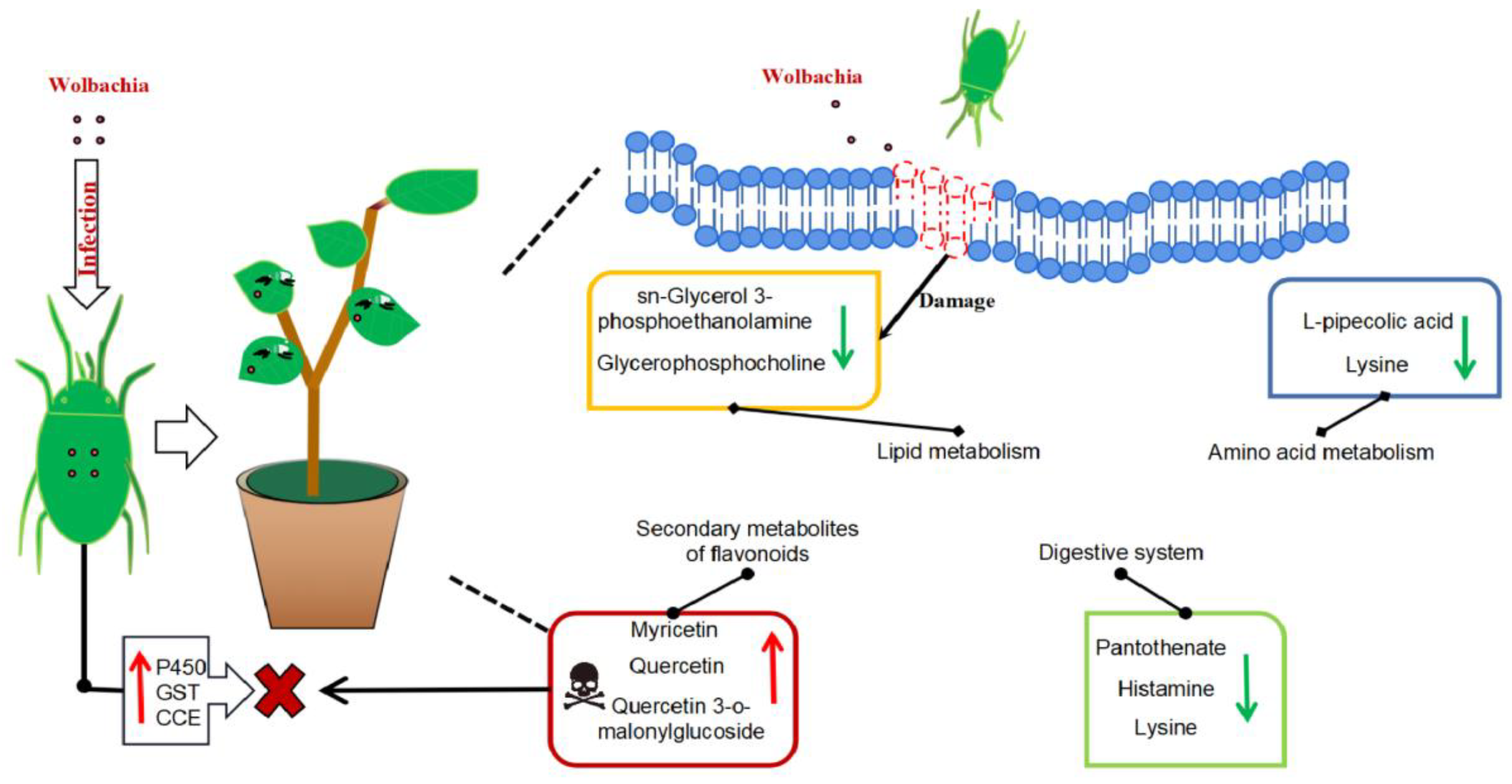

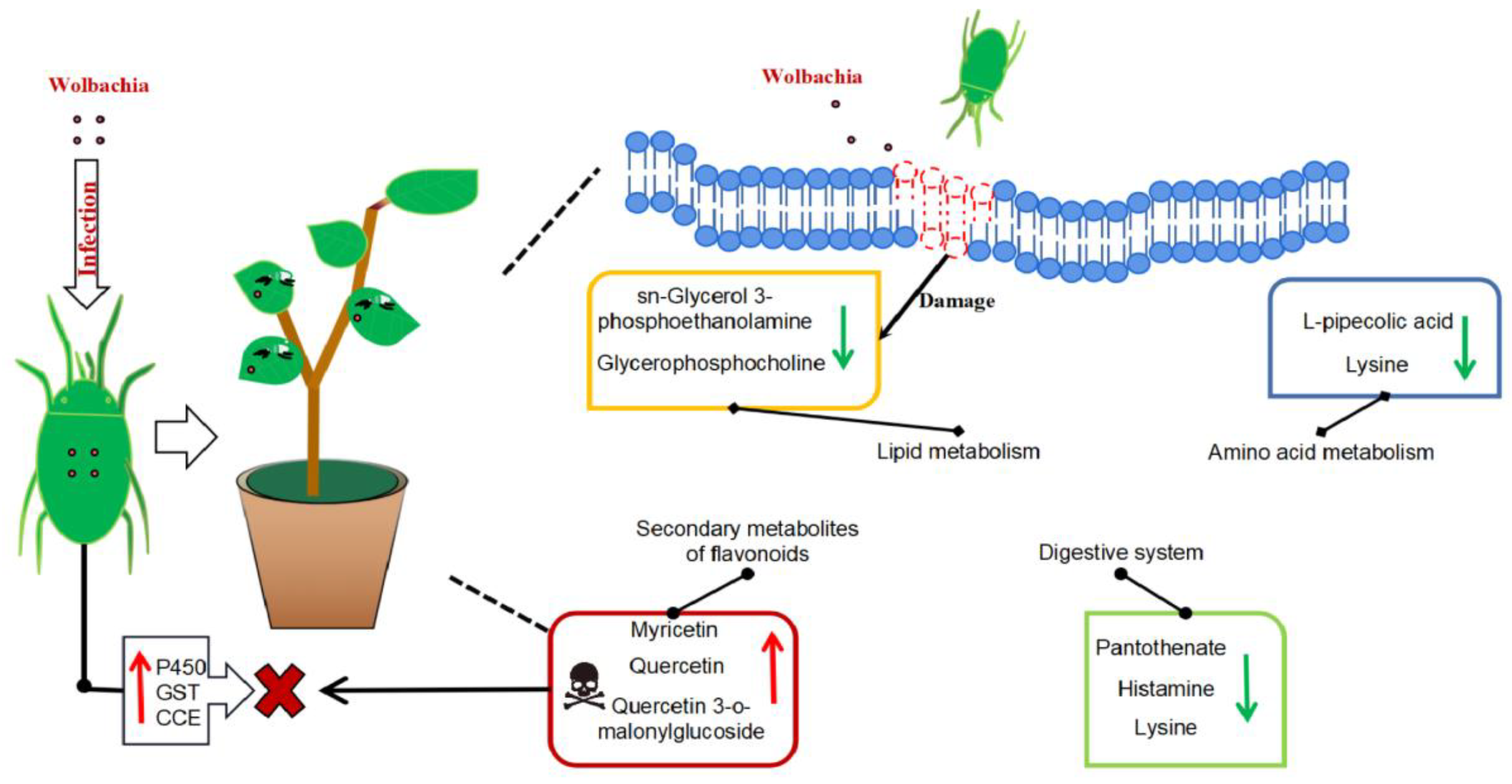

Figure 5 summarized the metabolic cycling pathways of cotton leaves infected by

Wolbachia infected spider mites, including lipid metabolism, secondary metabolism, protein and amino acid metabolism. Lysine biosynthesis linked lysine degradation and alkaloid biosynthesis, with lysine degradation entering the citric acid cycle via the pipecolic acid pathway. Glycerophospholipid metabolism interacted with ether lipid metabolism through 1 – acylglycerol – 3 - phosphate, and both GPC and PE were significantly downregulated in these two pathways. Among secondary metabolites, flavonoids such as quercetin and myricetin were significantly upregulated. In the protein digestion and absorption pathway, metabolites like L-lysine and pantothenic acid were significantly downregulated.

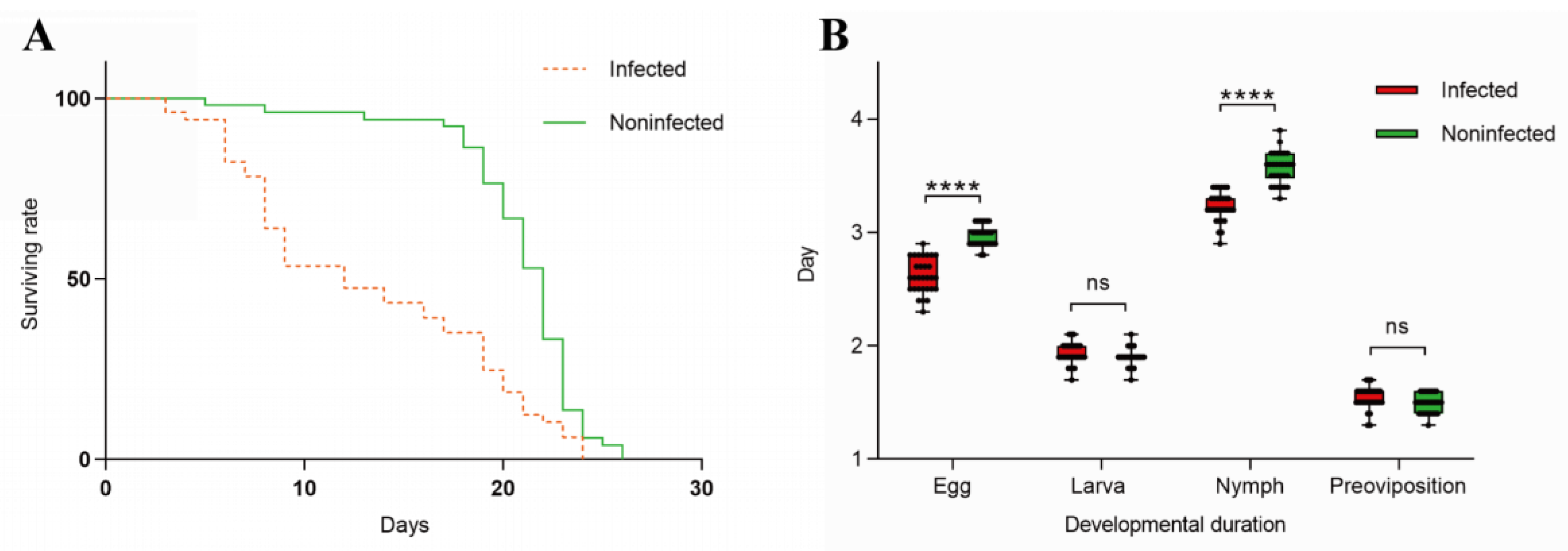

3.3. The Influence of Wolbachia on the Lifespan and Developmental Duration of the Host

Effects of

Wolbachia on the lifespan of

T. turkestani: Female mites infected with

Wolbachia began to die on the 3rd day after oviposition, while uninfected females started to die on the 5th day. Subsequently, the mortality rate of

Wolbachia infected female mites accelerated, with mass mortality occurring from the 6th day onwards. In contrast, uninfected female mites exhibited mass mortality starting on the 18th day. The lifespan difference between the two groups was extremely significant (χ

2= 25.53, df = 1, P < 0.001) (

Figure 6A).

Influence of

Wolbachia on the developmental duration of

T. turkestani: There was no significant differences in the larval stage (1.93 ± 0.10 days for infected females vs. 1.90 ± 0.08 days for uninfected females; P = 0.189) and pre-oviposition period (1.54 ± 0.10 days for infected females vs. 1.49 ± 0.08 days for uninfected females; P = 0.056) between

Wolbachia infected and uninfected female mites. However, the egg stage (2.62 ± 0.15 days for infected females vs. 2.97 ± 0.11 days for uninfected females) and nymphal stage (3.23 ± 0.13 days for infected females vs. 3.57 ± 0.14 days for uninfected females) were significantly shorter in infected mites (P < 0.01). The overall developmental duration from the egg stage to the pre-oviposition period was also significantly different between infected (9.31 ± 0.25 days) and uninfected (9.93 ± 0.19 days) female mites (P < 0.01)(

Figure 6B). The experimental results indicated that

Wolbachia infection shortened both the lifespan and developmental duration of

T. turkestani.

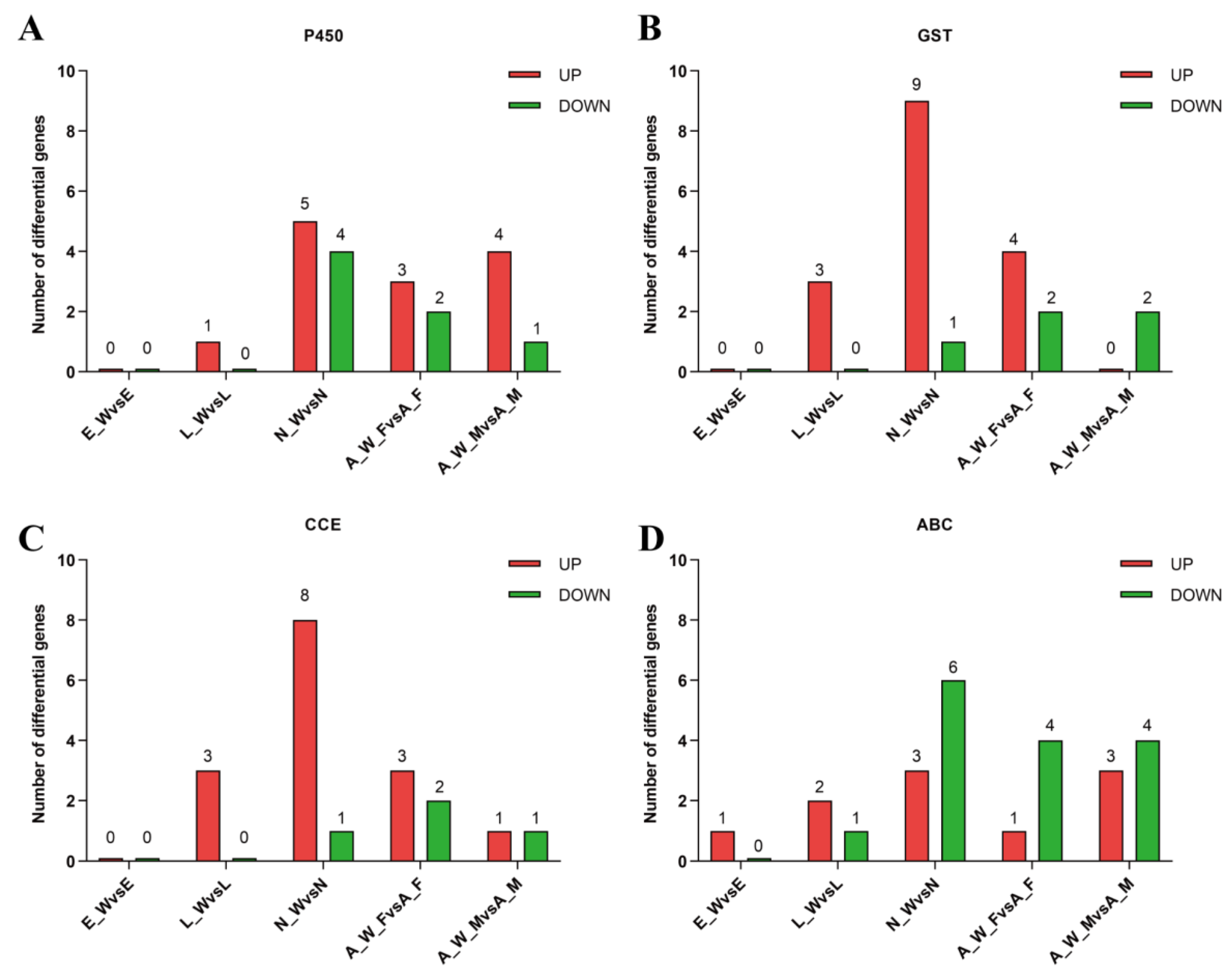

3.4. Wolbachia Enhanced the Expression of Detoxification Metabolism Genes T. turkestani

Following

Wolbachia infection, differential expression of genes involved in detoxification metabolism was observed across various developmental stages. This included major detoxification gene families such as cytochrome P450, glutathione S-transferase, carboxylesterase, and ABC transporters (

Figure 7). During the egg stage (E_W vs E), 1 gene was upregulated and none were downregulated; during the larval stage (L_W vs L), 9 genes were upregulated and 1 gene was downregulated; during the nymph stage (N_W vs N), 25 genes were upregulated and 12 genes were downregulated; in adult females (A_W_F vs A_F), 11 genes were upregulated and 10 genes were downregulated; and in adult males, 8 genes were upregulated and 8 genes were downregulated(see Appendix Table A3). The number of upregulated detoxification metabolism genes exceeded the number of downregulated genes across different developmental stages, indicating that

Wolbachia infection enhanced the detoxification capacity of the host mites.

4. Discussion

This study utilized metabolomics to reveal differences in the metabolic profiles of cotton leaves infected with Wolbachia infected and uninfected mites. Differential metabolites included glycerophosphocholine, sn - glycerol - 3 - phosphoethanolamine, malic acid, quercetin, amino acids, lignans, etc. KEGG pathway enrichment analysis showed significant differences in pathways such as flavonoid and flavonol biosynthesis, glycerophospholipid metabolism, and the biosynthesis of tropane, piperidine, and pyridine alkaloids. These changes likely resulted from Wolbachia induced activation of the defense mechanism in cotton leaves.

4.1. Wolbachia Infection Induced the Production of Secondary Metabolites in Cotton

The biosynthesis of secondary metabolites involved two KEGG pathways: flavonoid and flavonol biosynthesis, and the biosynthesis of tropane, piperidine, and pyridine alkaloids. Flavonoid metabolites are the most widely distributed and have a diverse metabolic functions, playing important roles in plant development and defense system [

22,

23,

24]. Flavonoid compounds act as phytoalexins or antioxidants with reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavenging capabilities, protecting plants from biotic and abiotic stresses, including pathogen infections and insect feeding [

25,

26]. Differential metabolites identified in this study, such as quercetin, kaempferol, amentoflavone, and myricetin, belonged to the flavonoid class. Among them, myricetin (M319T406_1) showed a 1.83-fold increase, and quercetin (M303T406_2) exhibited a 4.4-fold increase, contributing to enhanced plant defense capabilities.

4.2. Wolbachia Infection Impaired the Lipid Metabolism of Cotton

In addition to secondary metabolism, significant changes were observed in the lipid metabolites of cotton, particularly with notable downregulation of sn-glycerol-3-phosphoethanolamine (PE) and glycerophosphocholine (GPC). Lipid metabolism enriched two pathways: ether lipid metabolism and glycerophospholipid metabolism, both of which are key components of cell membranes [

27,

28]. PE plays an important role in ether lipid metabolism and is critical for the formation and stability of cell membrane as one of their constituent components. GPC, a vital phospholipid, play a key role in glycerophospholipid metabolism and helps maintain the integrity and functionality of cell membrane.

Wolbachia infection damaged the integrity and function of plant cell membranes, potentially facilitating the better feeding of mites on the plant intracellular sap.

4.3. Wolbachia Infection Disrupts the Growth and Reproduction of Mites

Two pathways were enriched in the digestive system: protein digestion and absorption, and vitamin digestion and absorption. In the protein digestion and absorption pathway, differential metabolites such as lysine and histamine were downregulated. Lysine is one of the essential amino acids for protein synthesis in plants and has significant effects on plant physiological functions, such as regulating stress responses, promoting growth, and enhancing resistance. Lysine is similarly important in animals and plays an important role in fat metabolism. Previous studies have shown that fluctuations in lysine content significantly effect insects. A decrease in lysine has been linked to reduced lifespan and weight loss in bumblebees [

29]. In this study, lysine in cotton leaves was downregulated, leading to a deficiency in lysine supply for cotton mites, which may have contributed to a shortened lifespan for the mites. Malic acid, a key organic acid in energy metabolism [

30], had a VIP value of 6.99 and a fold change of 9.25 in the differential metabolites. Malate salt had a VIP value of 7.57 and a fold change of 1.29. Besides playing a role in energy metabolism[

31], L-malic acid also reduces fat content in insects that consume it[

32]. In this study, L-malic acid was significantly increased in cotton leaves, damaging the fat storage process in cotton mites and negatively impacting their survival.

4.4. Wolbachia Infection Enhanced the Detoxification Ability of Mites

In plant-insect interactions, plants produce more secondary metabolites for self-defense, while symbiotic bacteria assist insects in enhancing their detoxification metabolic capacity. In this study,

Wolbachia infection induced the upregulation of numerous detoxification metabolic genes in cotton mites, playing an essential role in detoxifying secondary metabolites from plants and improving the adaptability to host plants [

33]. However, detoxification metabolism consumed a substantial amount of energy, requiring a trade-off between growth, reproduction, and survival, which contributed to the shortened lifespan of cotton mites [

34]. This study utilized metabolomics to reveal the differences in metabolic profiles of cotton leaves infected by

Wolbachia infected and uninfected mites, showing that

Wolbachia effected both cotton and the mites in multiple ways (

Figure 8). The study systematically revealed the molecular mechanisms of plant defense induced by endosymbiotic bacteria at the metabolic level, contributing to the expansion and supplementation of the theory of co-evolution between insects and plants. Further exploration of the potential functions of endosymbiotic bacteria in insect-plant interactions holds significant theoretical and practical importance in understanding the adaptive mechanisms of insects to biotic and abiotic factors, as well as the molecular mechanisms behind the host-insect- mediated defense effects on the plant.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.W and Y.Z.; methodology, X.W and Y.Z.; software, X.W.; validation, X.W., S.W.; formal analysis, S.W.; investigation, X.W.; resources, X.W and S.W.; data curation, X.W.; writing—original draft preparation, X.W.; writing—review and editing, X.W., Y.Z., Q.W., K.Z.; visualization, X.W.; supervision, S.W.; project administration, Y.Z. and F.L.; funding acquisition, Y.Z. and F.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32260676, 31860508) and China Corps strong youth science and technology leading talent project (2022CB002-06) and the Natural Science Foundation of the China Corps (2024DA018).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Ali Basit for valuable and encouraging discussions. We appreciate the efforts of the anonymous reviewers and the editors’ valuable suggestions in earlier versions of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Duron Olivier;Bouchon Didier;Boutin Sébastien;Bellamy Lawrence;Zhou Liqin;Engelstädter Jan;Hurst Gregory The Diversity of Reproductive Parasites among Arthropods: Wolbachia Do Not Walk Alone. BMC Biol. 2008, 27. [CrossRef]

- A.S. AdamsA.S. Adams;C.R. CurrieC.R. Currie;Y. CardozaY. Cardoza;K.D. KlepzigK.D. Klepzig;K.F. RaffaK.F. Raffa Effects of Symbiotic Bacteria and Tree Chemistry on the Growth and Reproduction of Bark Beetle Fungal Symbionts. Can. J. For. Res. 2009, 1133–1147. [CrossRef]

- Kerry M. Oliver;Patrick H. Degnan;Martha S. Hunter;Nancy A. Moran Bacteriophages Encode Factors Required for Protection in a Symbiotic Mutualism. Science 2009, 992–994. [CrossRef]

- Hosokawa Takahiro;Koga Ryuichi;Kikuchi Yoshitomo;Meng Xian-Ying;Fukatsu Takema Wolbachia as a Bacteriocyte-Associated Nutritional Mutualist. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010, 769–774. [CrossRef]

- Sugio Akiko;Dubreuil Géraldine;Giron David;Simon Jean-Christophe Plant-Insect Interactions under Bacterial Influence: Ecological Implications and Underlying Mechanisms. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 467–478. [CrossRef]

- Enric Frago;Marcel Dicke;H. Charles J. Godfray Insect Symbionts as Hidden Players in Insect–Plant Interactions. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2012, 705–711. [CrossRef]

- Giron David;Glevarec Gaëlle Cytokinin-Induced Phenotypes in Plant-Insect Interactions: Learning from the Bacterial World. J. Chem. Ecol. 2014, 826–835. [CrossRef]

- Simon C. Groen;Parris T. Humphrey;Daniela Chevasco;Frederick M. Ausubel;Naomi E. Pierce;Noah K. Whiteman Pseudomonas Syringae Enhances Herbivory by Suppressing the Reactive Oxygen Burst in Arabidopsis. J. Insect Physiol. 2016, 90–102. [CrossRef]

- Chung Seung Ho;Rosa Cristina;Scully Erin D;Peiffer Michelle;Tooker John F;Hoover Kelli;Luthe Dawn S;Felton Gary W Herbivore Exploits Orally Secreted Bacteria to Suppress Plant Defenses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013, 15728–15733. [CrossRef]

- Qi Su;Kerry M. Oliver;Wen Xie;Qingjun Wu;Shaoli Wang;Youjun Zhang The Whitefly-associated Facultative Symbiont Hamiltonella Defensa Suppresses Induced Plant Defences in Tomato. Funct. Ecol. 2015, 1007–1018. [CrossRef]

- Heike Staudacher;Bernardus C. J. Schimmel;Mart M. Lamers;Nicky Wybouw;Astrid T. Groot;Merijn R. Kant;Massimo Maffei Independent Effects of a Herbivore’s Bacterial Symbionts on Its Performance and Induced Plant Defences. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 182–182. [CrossRef]

- Zhurov Vladimir;Navarro Marie;Bruinsma Kristie A;Arbona Vicent;Santamaria M Estrella;Cazaux Marc;Wybouw Nicky;Osborne Edward J;Ens Cherise;Rioja Cristina;Vermeirssen Vanessa;Rubio-Somoza Ignacio;Krishna Priti;Diaz Isabel;Schmid Markus;Gómez-Cadenas Aurelio;Van de Peer Yves;Grbic Miodrag;Clark Richard M;Van Leeuwen Thomas;Grbic Vojislava Reciprocal Responses in the Interaction between Arabidopsis and the Cell-Content-Feeding Chelicerate Herbivore Spider Mite. Plant Physiol. 2014, 384–399. [CrossRef]

- Zhu Yu-Xi;Song Zhang-Rong;Song Yue-Ling;Hong Xiao-Yue Double Infection of Wolbachia and Spiroplasma Alters Induced Plant Defense and Spider Mite Fecundity. Pest Manag. Sci. 2020, 3273–3281. [CrossRef]

- Karami-Jamour, T. ;Shishehbor Development and Life Table Parameters of Tetranychus Turkestani (Acarina: Tetranychidae) at Different Constant Temperatures. Acarologia 2012, 113–122. [CrossRef]

- Gong JunTao;Li TongPu;Wang MengKe;Hong XiaoYue Wolbachia-Based Strategies for Control of Agricultural Pests. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2023, 101039–101039. [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Li, S.; Baoyin, B.; Feng, Y.; Guo, D.; Zhang, L.; Gu, Y. Maize/Soybean Intercropping with Straw Return Increases Crop Yield by Influencing the Biological Characteristics of Soil. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1108. [CrossRef]

- Yun Heng Miao;Wei Hao Dou;Jing Liu;Da Wei Huang;Jin Hua Xiao Single-Cell Transcriptome Sequencing Reveals That Wolbachia Induces Gene Expression Changes in Drosophila Ovary Cells to Favor Its Own Maternal Transmission. mBio 2024, e0147324. [CrossRef]

- Yang Kun;Chen Han;Bing Xiao Li;Xia Xue;Zhu Yu Xi;Hong Xiao Yue Wolbachia and Spiroplasma Could Influence Bacterial Communities of the Spider Mite Tetranychus Truncatus. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2021, 197–210. [CrossRef]

- Yu-Xi Zhu;Yue-Ling Song;Ary A. Hoffmann;Peng-Yu Jin;Shi-Mei Huo;Xiao-Yue Hong A Change in the Bacterial Community of Spider Mites Decreases Fecundity on Multiple Host Plants. MicrobiologyOpen 2019, n/a-n/a. [CrossRef]

- Morimoto Sayaka;Kurtti Timothy J;Noda Hiroaki In Vitro Cultivation and Antibiotic Susceptibility of a Cytophaga-like Intracellular Symbiote Isolated from the Tick Ixodes Scapularis. Curr. Microbiol. 2006, 324–329. [CrossRef]

- E. M. Bakr A New Software for Measuring Leaf Area, and Area Damaged by Tetranychus Urticae Koch. J. Appl. Entomol. 2005, 173–175. [CrossRef]

- Seyed Mohammad Nabavi;Dunja Šamec;Michał Tomczyk;Luigi Milella;Daniela Russo;Solomon Habtemariam;Ipek Suntar;Luca Rastrelli;Maria Daglia;Jianbo Xiao;Francesca Giampieri;Maurizio Battino;Eduardo Sobarzo-Sanchez;Seyed Fazel Nabavi;Bahman Yousefi;Philippe Jeandet;Suowen Xu;Samira Shirooie Flavonoid Biosynthetic Pathways in Plants: Versatile Targets for Metabolic Engineering. Biotechnol. Adv. 2020, 107316. [CrossRef]

- Philippe Jeandet;Claire Hébrard;Marie-Alice Deville;Sylvain Cordelier;Stéphan Dorey;Aziz Aziz;Jérôme Crouzet Deciphering the Role of Phytoalexins in Plant-Microorganism Interactions and Human Health. Molecules 2014, 18033–18056. [CrossRef]

- Sylvain Cordelier;Christophe Clément;Eric Courot;Philippe Jeandet Modulation of Phytoalexin Biosynthesis in Engineered Plants for Disease Resistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14136–14170. [CrossRef]

- Liu Weixin;Feng Yi;Yu Suhang;Fan Zhengqi;Li Xinlei;Li Jiyuan;Yin Hengfu The Flavonoid Biosynthesis Network in Plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 12824–12824. [CrossRef]

- Agati Giovanni;Tattini Massimiliano Multiple Functional Roles of Flavonoids in Photoprotection. New Phytol. 2010, 786–793. [CrossRef]

- Ana Rita Cavaco;Ana Rita Matos;Andreia Figueiredo Speaking the Language of Lipids: The Cross-Talk between Plants and Pathogens in Defence and Disease. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2021, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Fahy Eoin;Subramaniam Shankar;Brown H Alex;Glass Christopher K;Merrill Alfred H;Murphy Robert C;Raetz Christian R H;Russell David W;Seyama Yousuke;Shaw Walter;Shimizu Takao;Spener Friedrich;van Meer Gerrit;VanNieuwenhze Michael S;White Stephen H;Witztum Joseph L;Dennis Edward A A Comprehensive Classification System for Lipids. J. Lipid Res. 2005, 839–861. [CrossRef]

- Le Couteur David G;Solon-Biet Samantha;Cogger Victoria C;Mitchell Sarah J;Senior Alistair;de Cabo Rafael;Raubenheimer David;Simpson Stephen J The Impact of Low-Protein High-Carbohydrate Diets on Aging and Lifespan. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. CMLS 2016, 1237–1252. [CrossRef]

- Wu Min;Zhao Yitao;Tao Meihan;Fu Meimei;Wang Yue;Liu Qi;Lu Zhihui;Guo Jinshan Malate-Based Biodegradable Scaffolds Activate Cellular Energetic Metabolism for Accelerated Wound Healing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023. [CrossRef]

- Farney Tyler M;Bliss Matthew V;Hearon Christopher M;Salazar Dassy A The Effect of Citrulline Malate Supplementation on Muscle Fatigue Among Healthy Participants. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2019, 2464–2470. [CrossRef]

- Chul Hong Park;Minsung Park;Miranda E Kelly;Helia Cheng;Sang Ryeul Lee;Cholsoon Jang;Ji Suk Chang Cold-Inducible GOT1 Activates the Malate-Aspartate Shuttle in Brown Adipose Tissue to Support Fuel Preference for Fatty Acids. BioRxiv Prepr. Serv. Biol. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Li F;Liu X N;Zhu Y;Ma J;Liu N;Yang J H Identification of the 2-Tridecanone Responsive Region in the Promoter of Cytochrome P450 CYP6B6 of the Cotton Bollworm, Helicoverpa Armigera (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Bull. Entomol. Res. 2014, 801–808. [CrossRef]

- Jiang Heng;Meng Xiangkun;Zhang Nan;Ge Huichen;Wei Jiaping;Qian Kun;Zheng Yang;Park Yoonseong;Reddy Palli Subba;Wang Jianjun The Pleiotropic AMPK-CncC Signaling Pathway Regulates the Trade-off between Detoxification and Reproduction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2023, e2214038120–e2214038120. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Phenotype of cotton leaves infected by mites with different Wolbachia Infection Status: (a)Cotton leaves after YJ infection; (B) Cotton leaves after WJ infection; (C) Comparison of damaged leaf area.

Figure 1.

Phenotype of cotton leaves infected by mites with different Wolbachia Infection Status: (a)Cotton leaves after YJ infection; (B) Cotton leaves after WJ infection; (C) Comparison of damaged leaf area.

Figure 2.

PCA of YJ and WJ Metabolomic Profiles: (A) PCA analysis of variance stabilized counts in positive ion mode for YJ vs WJ; (B) PCA analysis of variance stabilized counts in negative ion mode for YJ vs WJ; (C) OPLS-DA of positive ion mode in YJ vs WJ; (D) OPLS-DA of negative ion mode in YJ vs WJ; (E) Classification of differential metabolites.

Figure 2.

PCA of YJ and WJ Metabolomic Profiles: (A) PCA analysis of variance stabilized counts in positive ion mode for YJ vs WJ; (B) PCA analysis of variance stabilized counts in negative ion mode for YJ vs WJ; (C) OPLS-DA of positive ion mode in YJ vs WJ; (D) OPLS-DA of negative ion mode in YJ vs WJ; (E) Classification of differential metabolites.

Figure 3.

Differential metabolite analysis: (A) Differential metabolites volcano plot of YJ vs WJ in positive ion mode; (B) Differential metabolites volcano plot of YJ vs WJ in negative ion mode; (C) Fold changes of significant differential metabolites in positive ion mode of YJ vs WJ; (D) Fold changes of significant differential metabolites in negative ion mode of YJ vs WJ; (E) Hierarchical clustering heatmap in positive ion mode of YJ vs WJ; (E) Hierarchical clustering heatmap in negative ion mode of YJ vs WJ.

Figure 3.

Differential metabolite analysis: (A) Differential metabolites volcano plot of YJ vs WJ in positive ion mode; (B) Differential metabolites volcano plot of YJ vs WJ in negative ion mode; (C) Fold changes of significant differential metabolites in positive ion mode of YJ vs WJ; (D) Fold changes of significant differential metabolites in negative ion mode of YJ vs WJ; (E) Hierarchical clustering heatmap in positive ion mode of YJ vs WJ; (E) Hierarchical clustering heatmap in negative ion mode of YJ vs WJ.

Figure 4.

KEGG enrichment analysis of differential metabolites: (A) Pathway enrichment map of differential metabolites in YJ vs WJ; (B) Abundance difference score plot for differential metabolite enrichment pathways in YJ vs WJ.

Figure 4.

KEGG enrichment analysis of differential metabolites: (A) Pathway enrichment map of differential metabolites in YJ vs WJ; (B) Abundance difference score plot for differential metabolite enrichment pathways in YJ vs WJ.

Figure 5.

KEGG enrichment pathway analysis for differential metabolites. This figure illustrates lipid metabolism, secondary metabolism, protein and amino acid metabolism within cotton cells. Lysine biosynthesis connected lysine degradation and alkaloid synthesis, with lysine degradation entering the citric acid cycle via the pipecolic acid pathway. Glycerophospholipid metabolism interacted with ether lipid metabolism through 1 – acylglycerol – 3 - phosphate, and both glycerophosphocholine (GPC) and sn – glycerol – 3 - phosphoethanolamine (PE) were significantly downregulated in both glycerophospholipid metabolism and ether lipid metabolism pathways. Flavonoids such as quercetin and myricetin were significantly upregulated among secondary metabolites, while L-lysine and pantothenic acid were significantly downregulated in the protein digestion and absorption pathway.

Figure 5.

KEGG enrichment pathway analysis for differential metabolites. This figure illustrates lipid metabolism, secondary metabolism, protein and amino acid metabolism within cotton cells. Lysine biosynthesis connected lysine degradation and alkaloid synthesis, with lysine degradation entering the citric acid cycle via the pipecolic acid pathway. Glycerophospholipid metabolism interacted with ether lipid metabolism through 1 – acylglycerol – 3 - phosphate, and both glycerophosphocholine (GPC) and sn – glycerol – 3 - phosphoethanolamine (PE) were significantly downregulated in both glycerophospholipid metabolism and ether lipid metabolism pathways. Flavonoids such as quercetin and myricetin were significantly upregulated among secondary metabolites, while L-lysine and pantothenic acid were significantly downregulated in the protein digestion and absorption pathway.

Figure 6.

Effects of Wolbachia on the reproductive capacity and fitness of spider mites: (A) Survival rate; (B) Duration of development.

Figure 6.

Effects of Wolbachia on the reproductive capacity and fitness of spider mites: (A) Survival rate; (B) Duration of development.

Figure 7.

Differential expression of detoxification metabolism genes in different developmental stages of spider mite. E_W vs E: Egg Stage; L_W vs L: Larval Stage; N_W vs N: Nymphal Stage; A_W_F vs A_F: Adult Female; A_W_M vs A_M: Adult Male: (A) Cytochrome P450; (B) Glutathione S-transferase; (C) Carboxylesterase; (D) ABC transporter.

Figure 7.

Differential expression of detoxification metabolism genes in different developmental stages of spider mite. E_W vs E: Egg Stage; L_W vs L: Larval Stage; N_W vs N: Nymphal Stage; A_W_F vs A_F: Adult Female; A_W_M vs A_M: Adult Male: (A) Cytochrome P450; (B) Glutathione S-transferase; (C) Carboxylesterase; (D) ABC transporter.

Figure 8.

Metabolic profile of cotton leaves infected by Wolbachia-infected mites: Wolbachia infection induced secondary metabolites in cotton led to the activation of flavonoid and flavonol biosynthesis, tropane, piperidine, and pyridine alkaloids biosynthesis, resulting in significant upregulation of flavonoid compounds such as quercetin, enhancing the plant defense. It impairs lipid metabolism, resulting in a significant downregulation of lipid metabolites such as sn - glycerol - 3 - phosphoethanolamine and glycerophosphocholine, and disrupting the integrity and functionality of plant cell membranes, potentially facilitating mite feeding. It also disrupts the growth and reproduction of mites with down-regulation of lysine leading to a deficiency in essential amino acids supply, and a significant increase in L-malic acid, which damaged fat storage process in mites and shortened their lifespan. Wolbachia infection induced the upregulation of numerous detoxification metabolic genes in mites, enhancing their ability to detoxify plant secondary metabolites.

Figure 8.

Metabolic profile of cotton leaves infected by Wolbachia-infected mites: Wolbachia infection induced secondary metabolites in cotton led to the activation of flavonoid and flavonol biosynthesis, tropane, piperidine, and pyridine alkaloids biosynthesis, resulting in significant upregulation of flavonoid compounds such as quercetin, enhancing the plant defense. It impairs lipid metabolism, resulting in a significant downregulation of lipid metabolites such as sn - glycerol - 3 - phosphoethanolamine and glycerophosphocholine, and disrupting the integrity and functionality of plant cell membranes, potentially facilitating mite feeding. It also disrupts the growth and reproduction of mites with down-regulation of lysine leading to a deficiency in essential amino acids supply, and a significant increase in L-malic acid, which damaged fat storage process in mites and shortened their lifespan. Wolbachia infection induced the upregulation of numerous detoxification metabolic genes in mites, enhancing their ability to detoxify plant secondary metabolites.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).