1. Introduction

Asphalt is a commonly used and relatively low-cost adhesive material that is extensively utilized in waterproofing and anti-seepage engineering applications [

1,

2]. However, its viscoelastic nature means that petroleum asphalt has a high modulus (stiffness) at low temperatures, allowing it to resist deformation effectively, but it also becomes brittle and susceptible to cracking. Conversely, at high temperatures, the modulus of asphalt decreases, resulting in a softer and more fluid material that enhances bonding with aggregates during construction, but may also lead to problems like rutting. To mitigate these challenges, high molecular polymers or nano-modifiers are often incorporated into asphalt to enhance its temperature-viscosity properties. Research has shown that these modifiers significantly influence the elastic modulus (G') and viscous modulus (G'') of asphalt binders within the linear viscoelastic range (LVR), enabling modified asphalt to maintain a favorable balance of viscoelasticity across a broader temperature spectrum and reducing its sensitivity to temperature fluctuations[

3,

4,

5]. However, the wide range of available modifiers, such as SBS, SBR, EVA, and CR, along with the various processing methods for each type of modified asphalt, greatly affect the performance of the asphalt [

6,

7,

8]. Finding a suitable modified asphalt solution for a specific application environment is a crucial aspect of this research.

Pumped-storage power stations in the northwest and northeast of China often encounter challenges due to extremely low temperatures. For instance, the Xilongchi and Hohhot stations require asphalt concrete that can withstand freeze-breaking temperatures of -38°C and -45°C, respectively [

9]. Low-temperature cracking is a frequent issue with asphalt mixtures. Typically, the shrinkage stress from low temperatures is alleviated through stress relaxation. However, at very low temperatures, asphalt mixtures behave like elastic materials, and if the temperature drops quickly, there isn't enough time for the shrinkage stress to relax, resulting in cracks when the stress surpasses the immediate ultimate tensile strength [

10]. Additionally, in areas with extended periods of low temperatures, thermal stress can accumulate over time. When the asphalt material relaxes to alleviate this stress, it can create residual stress. If the reduction of this residual stress is slower than the decrease in strength, cracking may occur[

11]. The freeze-breaking temperature is a crucial measure for assessing the low-temperature crack resistance of asphalt concrete in cold climates [

12]. Research by Wang[

13] indicated that the performance of asphalt significantly influences the low-temperature freeze-breaking temperature of asphalt concrete, with the brittle point and 5°C ductility of the asphalt showing a strong correlation with the freeze-breaking temperature.

In order to fulfill the needs of waterproofing projects in pumped-storage power stations situated in ultra-low areas, a modified asphalt with superior crack resistance has been developed. This paper utilizes response surface methodology (RSM) to enhance the design of the modified asphalt, aiming to find the optimal product solution.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Materials

Base Asphalt: The base asphalt used is grade A petroleum asphalt from naphthenic crude oil straight-run distillation, provided by Shandong Chambroad Petrochemicals Co., Ltd. Modifier: Linear SBS modifier, provided by Sinopec Baling Petrochemical Co., Ltd. The basic properties of the base asphalt and SBS modifier are shown in

Table 1 and

Table 2, respectively.

2.2. Experimental Design Method

Response surface methodology [

13,

14] is a commonly utilized statistical experimental technique for optimizing random processes, allowing for a thorough examination of parameters with minimal experiments and time. It helps uncover quantitative relationships between experimental indicators and factors, providing both local and global insights, which leads to clear experimental outcomes.

Using the Box-Behnken design and informed by single-factor experimental analysis, the modifier, stabilizer, and compatibilizer were chosen as independent variables, labeled A, B, and C, respectively. The three levels of these independent variables were indicated by +1, 0, and -1, with the brittle point serving as the response variable Y in the experimental design. The brittle point is a crucial temperature indicator for asphalt embrittlement at low temperatures, making it significant for the application of ultra-low temperature modified asphalt. The coding table for the experimental factors is presented in

Table 3.

The factors listed in

Table 3 were effectively represented alongside the experimental outcomes using Design Expert software to create a predictive model. This model was then examined to identify the best conditions, and validation experiments were performed to verify its accuracy.

2.3. Asphalt Preparation Method

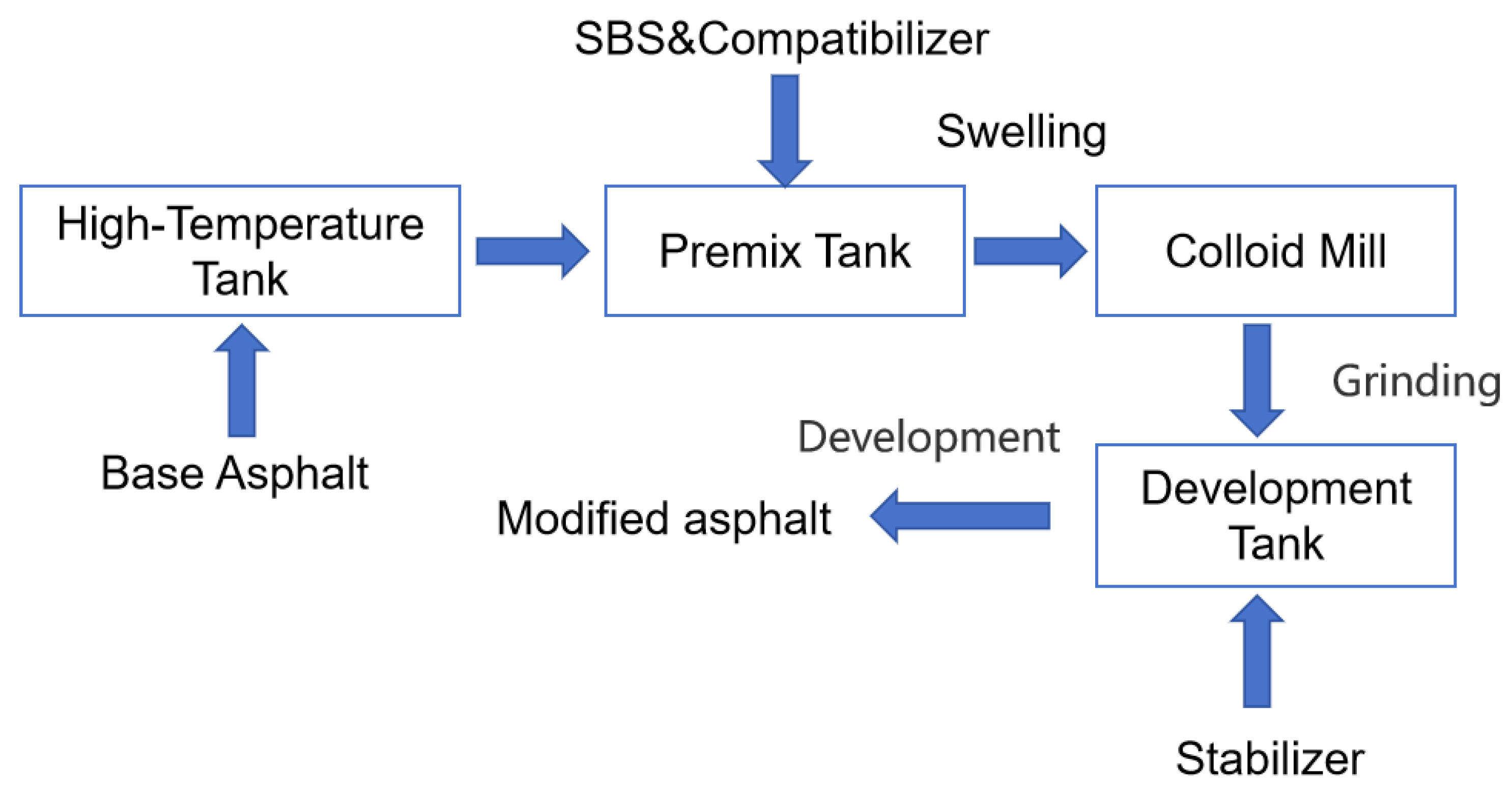

The base asphalt is heated until it becomes fluid under specific conditions, after which a compatibilizer is introduced and mixed thoroughly. Next, varying amounts of SBS modifier are added, and the mixture is stirred at a consistent temperature of 175-180°C to ensure that the SBS modifier completely absorbs the lighter components, swells, and disperses uniformly. Following this, the asphalt and modifier blend is processed through a colloid mill or shear machine for complete shear dispersion, and the modifier is fully cross-linked with the help of a stabilizer at 170-180°C, resulting in the final modified asphalt product.

Figure 1.

Modified Asphalt Production Process

Figure 1.

Modified Asphalt Production Process

2.4. Test Methods

Brittle Point Test: Follow the GB/T 4510 or DL/T 5362 standards. An asphalt sample is heated until it becomes liquid and then applied to a metal sheet to create a film that is 0.5 mm thick. After cooling at room temperature for one hour, the sample is placed in an automatic brittle point tester. The temperature is gradually decreased at a specified rate while the metal sheet is bent slowly and repeatedly. The temperature at which cracks form in the asphalt film due to the cooling and bending is recorded as the brittle point temperature.

Segregation Test: Adhere to the GB/T 4507 or DL/T 5362 standards. A sample of 50g±0.5g of modified asphalt is placed in a sample tube under specific conditions and then heated in an oven at 163±5°C for 48 hours. After being taken out of the oven, the sample is cooled in a refrigerator for 4 hours. It is then divided into three equal parts, and the softening points of the upper and lower segments are tested. The difference in these softening points is noted as the segregation value.

Force Ductility Test: Refer to the DL/T 5362 and DB 32/T 4861 standards. The asphalt is heated and poured into a ductility mold, then allowed to cool at room temperature for at least 1.5 hours. Any excess asphalt is removed with a hot knife to ensure the surface is level with the mold. The mold and base plate are then placed in a water bath at the designated test temperature for 1.5 hours. The ductility machine is activated, and the changes in tensile force and elongation during stretching are recorded. The integral of the tensile force over the elongation range indicates the cohesive energy, which reflects the energy needed to overcome the intermolecular forces in the asphalt.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Influence of Key Components on Modified Asphalt Performance

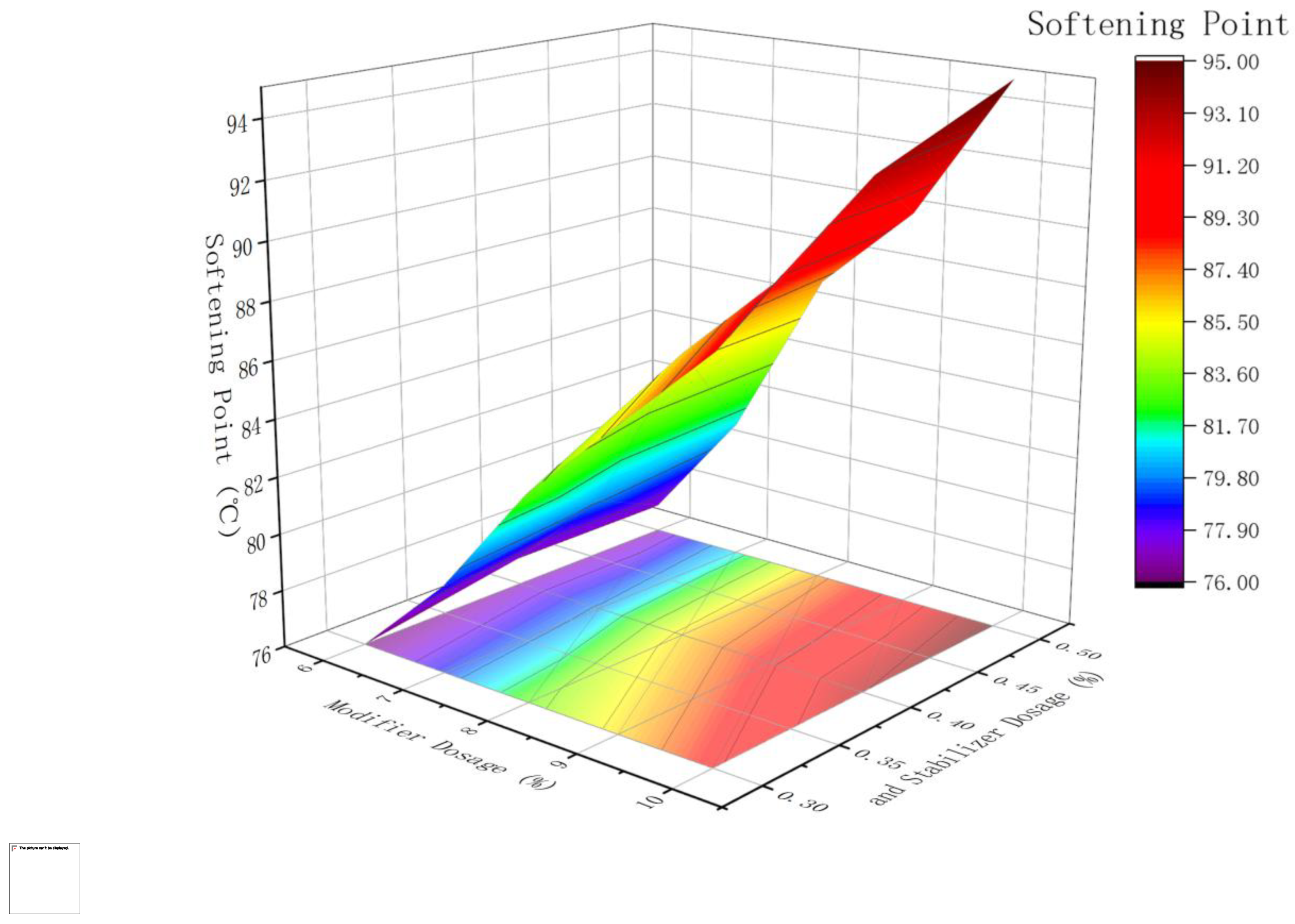

The properties of modified asphalt are affected by various factors, including the type and amount of modifiers, stabilizers, and compatibilizers, as well as the methods used in processing. In ultra-low temperature environments, the softening point, brittle point, and segregation value are identified as key indicators to assess the impact of modifiers and stabilizers. As illustrated in

Figure 2, the softening point rises in direct proportion to the amount of modifiers and stabilizers used.

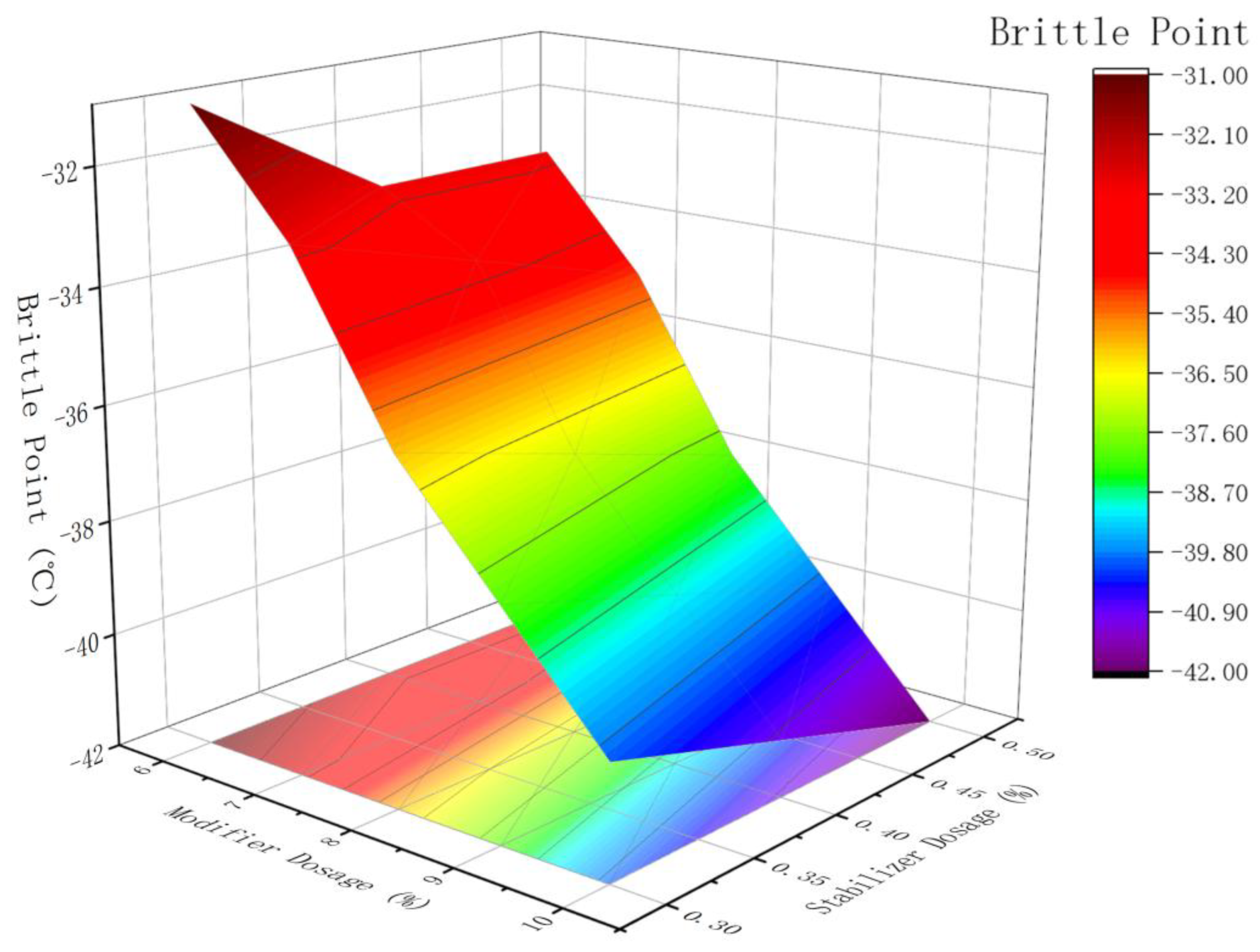

Figure 3 reveals that the brittle point decreases significantly with higher modifier amounts, while it remains relatively unchanged with increased stabilizer amounts.

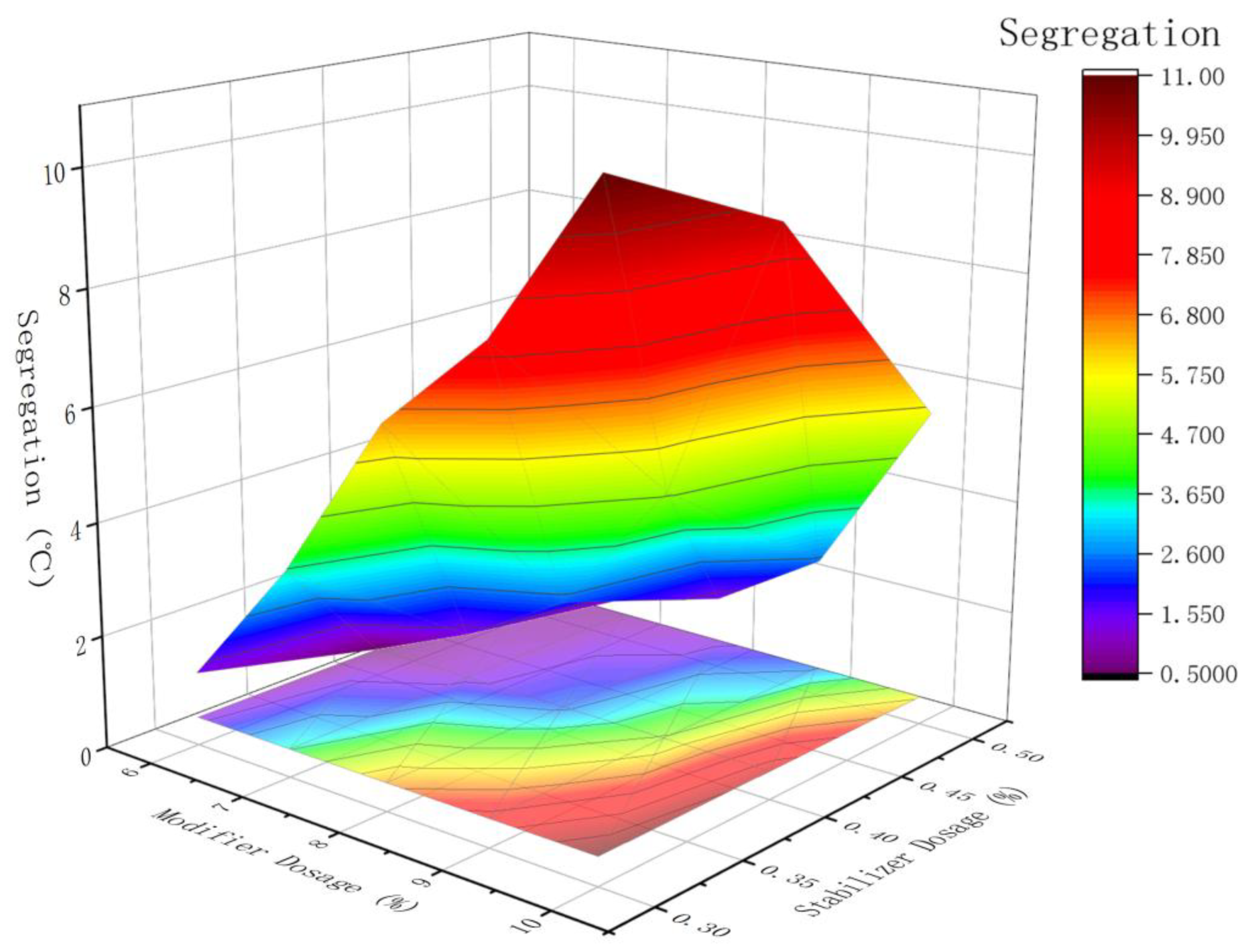

Figure 4 shows that segregation (the difference in softening point after 48 hours) increases with more modifier usage and slightly decreases with more stabilizer usage. Despite these observable trends, the indicators alone do not provide enough guidance for optimizing the product formulation.

3.2. Formula Optimization Based on Response Surface Methodology

The experimental design and the detection of the related results were conducted using the Box-Behnken model, with the factor coding detailed in

Table 3. The outcomes are presented in

Table 4. The experimental data from

Table 4 underwent multiple regression analysis using Design Expert software. The analysis of variance (ANOVA) for the response value (Y) in

Table 5 confirms the significance of both the model and each parameter. A "P" value below 0.05 indicates that the corresponding index is significant. The response value for the brittle point was regressed against each factor, resulting in an excellent model fit, which produced the following regression model:

The correlation coefficient R2 of the regression model is 0.9897, indicating a very good fit of the mode.

The variance analysis presented in

Table 5 indicates that the model's P value is 0.0002, demonstrating that response surface methodology is a viable approach for predicting the brittle point. Additionally, the P values for the three independent variables A, B, and C are all less than 0.05, suggesting that each variable significantly affects the brittle point, with the influence ranked as A > C > B.

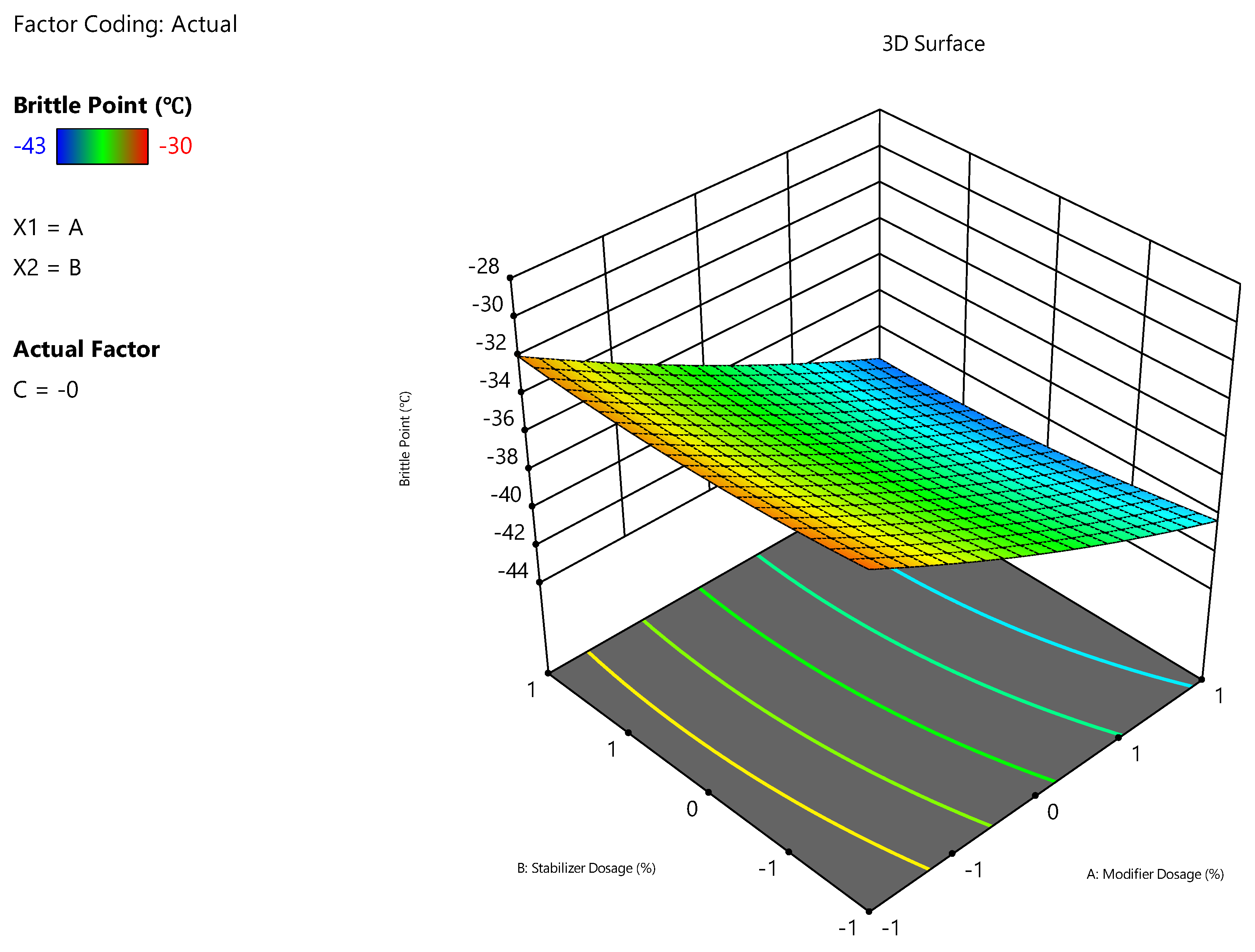

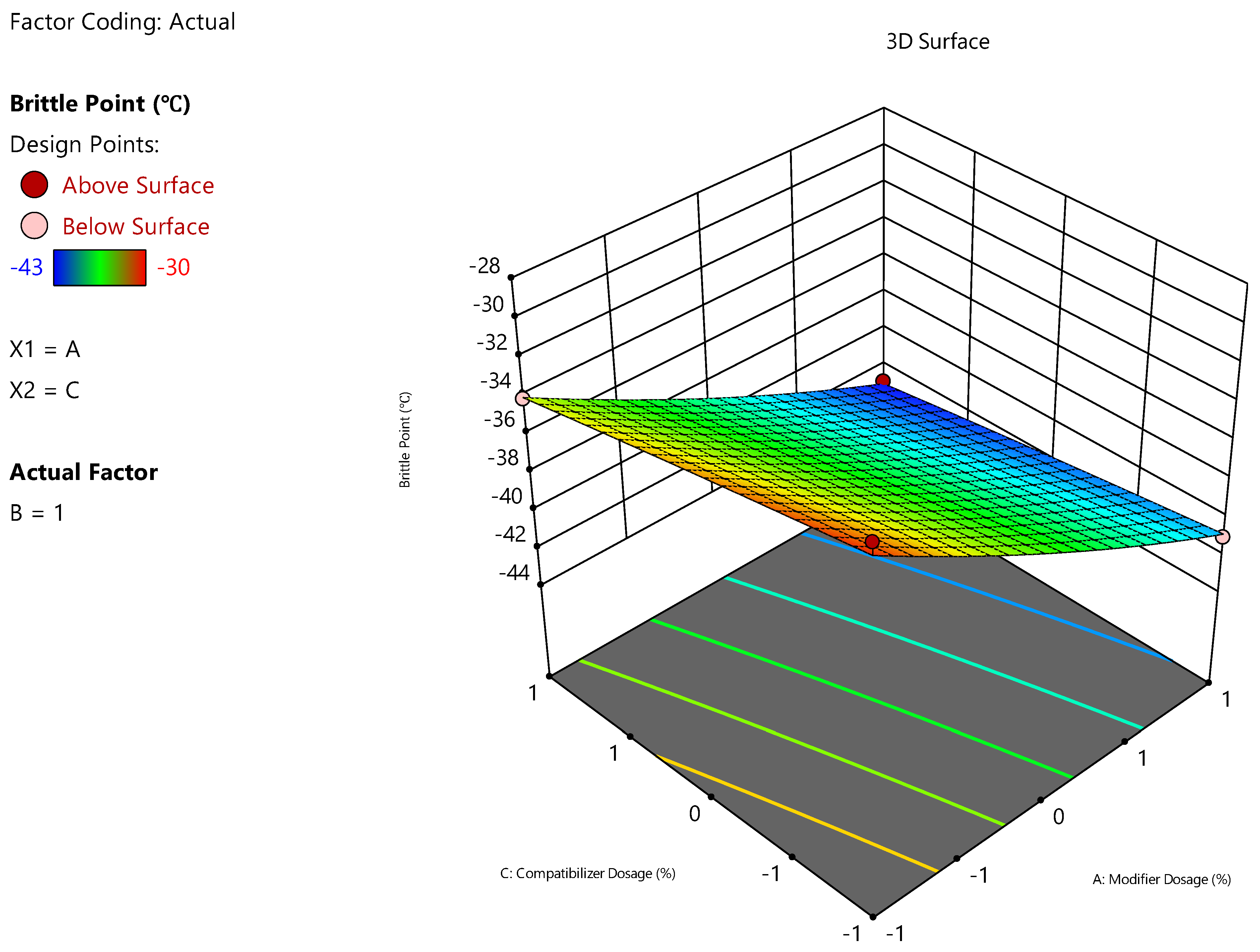

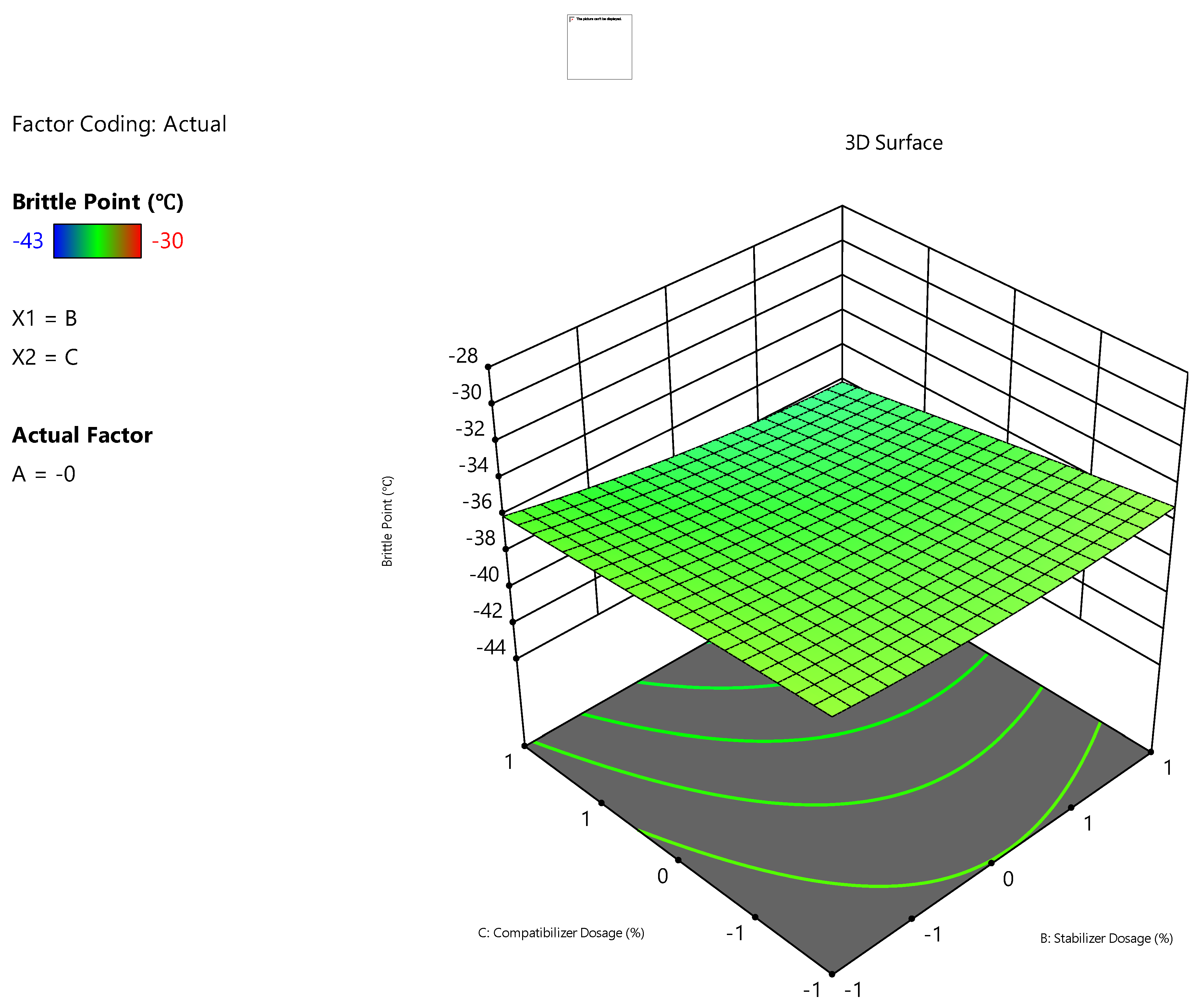

To better illustrate how the amounts of modifier, stabilizer, and compatibilizer affect the response value (brittle point), response surfaces were created using the experimental data. The contour plot represents a horizontal projection of the response surface plot. A steeper fitted surface and closer contour lines in the response surface plot indicate a stronger impact of the factor on the correlation [

15].

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 illustrate how the dosage of modifier interacts with stabilizer and compatibilizer dosages regarding the brittle point, while keeping the compatibilizer dosage constant. As the amount of modifier increases, there is a notable decrease in the brittle point, whereas the stabilizer has minimal impact on the brittle point at a fixed modifier dosage.

Figure 7 depicts the interaction between compatibilizer and stabilizer dosages on the brittle point, again with a constant modifier dosage. It is evident that both the compatibilizer and stabilizer have a negligible effect on the brittle point. Thus, it can be concluded that by managing the modifier dosage in modified hydraulic asphalt solutions, it is possible to produce asphalt products that satisfy various brittle point specifications.

Based on the conclusions drawn and the technical specifications for SBS I-A outlined in the "Design Code for Asphalt Concrete Panels and Core Walls in Earth and Rock-fill Dams" (NB/T 11015-2022), asphalt samples that comply with modified hydraulic standards were created by managing the brittle point and modifying the amount of the additive. The characteristics of these samples were subsequently analyzed and tested, with the findings displayed in

Table 6.

The analysis of the properties of modified hydraulic asphalt presented in

Table 6 indicates that the penetration levels of five different low-temperature grade hydraulic asphalts comply with the technical standards outlined in NB/T 11015-2022 SBS I-A. As the amount of modifier increases, the softening point of the asphalt rises, while the brittle point consistently decreases. Notably, with higher modifier content, the ductility before and after aging exhibits contrasting trends, with the ductility at 5°C after aging gradually surpassing that before aging, which deviates from the behavior of traditional modified asphalt. In conventional modified asphalt, the asphalt serves as the continuous phase and the modifier as the dispersed phase. However, in this study, as the modifier dosage increases, the system's phase state shifts, resulting in asphalt becoming the dispersed phase and the modifier the continuous phase. The formation of a high-density modifier network enhances the cohesion of the modified asphalt, and the movement of modifier molecules is constrained under tensile stress, causing unusual fractures (demolding phenomenon). Following short-term aging, the asphalt sample breaks some butadiene bonds, which diminishes the resistance to molecular movement and reduces cohesive energy, thereby increasing aging ductility. This aspect will be explored further in subsequent experiments.

3.3. Performance Study of Modified Hydraulic Asphalt

3.3.1. Study on Low-Temperature Crack Resistance

When the service temperature of hydraulic asphalt drops below its brittle point, the mechanical characteristics of the asphalt change significantly, shifting from a tough to a brittle state. This results in a marked reduction in its ductility and resistance to deformation, making it more susceptible to cracking due to thermal stress. Consequently, the brittle point acts as a key indicator of how much the asphalt materials have become brittle in low-temperature conditions, offering essential information for assessing their resistance to cracking in cold weather [

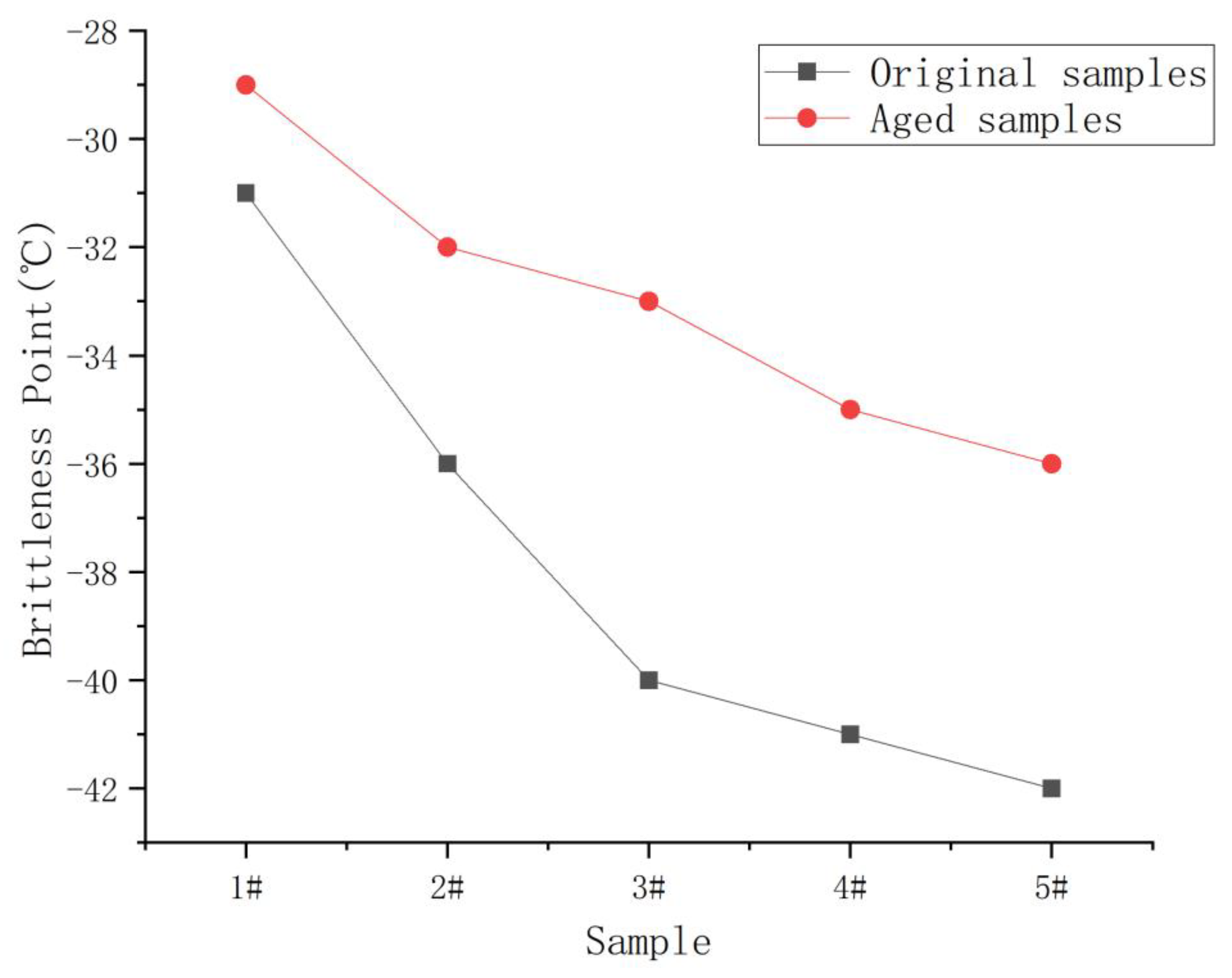

16]. In this research, the five asphalt samples detailed in

Table 4 underwent short-term aging, and the variations in their brittle points before and after the aging process were analyzed. The findings are presented in

Figure 8.

As illustrated in

Figure 8, the brittleness point of modified asphalt remains largely unchanged before and after aging through RTFOT. Specifically, as the amount of modifier increases, the brittleness point of the asphalt decreases, indicating enhanced low-temperature performance. However, with a higher dosage of the modifier, not only does the brittleness point drop, but the gap between the brittleness points before and after aging widens. This can be attributed to two main factors: First, the chemical structure of the SBS modifier includes double bonds that are susceptible to oxidation when exposed to heat, oxygen, and light, resulting in the formation of new functional groups that disrupt the original network structure and diminish asphalt performance [

17]. Second, both the base asphalt and compatibilizer contain minor amounts of lighter components that are lost during aging, which increases the viscosity of the SBS-modified asphalt and hampers its capacity for plastic deformation. Therefore, when choosing modified asphalt, it is important to take into account the changes in brittleness points before and after aging, and to establish a threshold for the difference in brittleness points based on actual engineering requirements.

3.3.2. Study on Low-Temperature Tensile Properties of Modified Asphalt

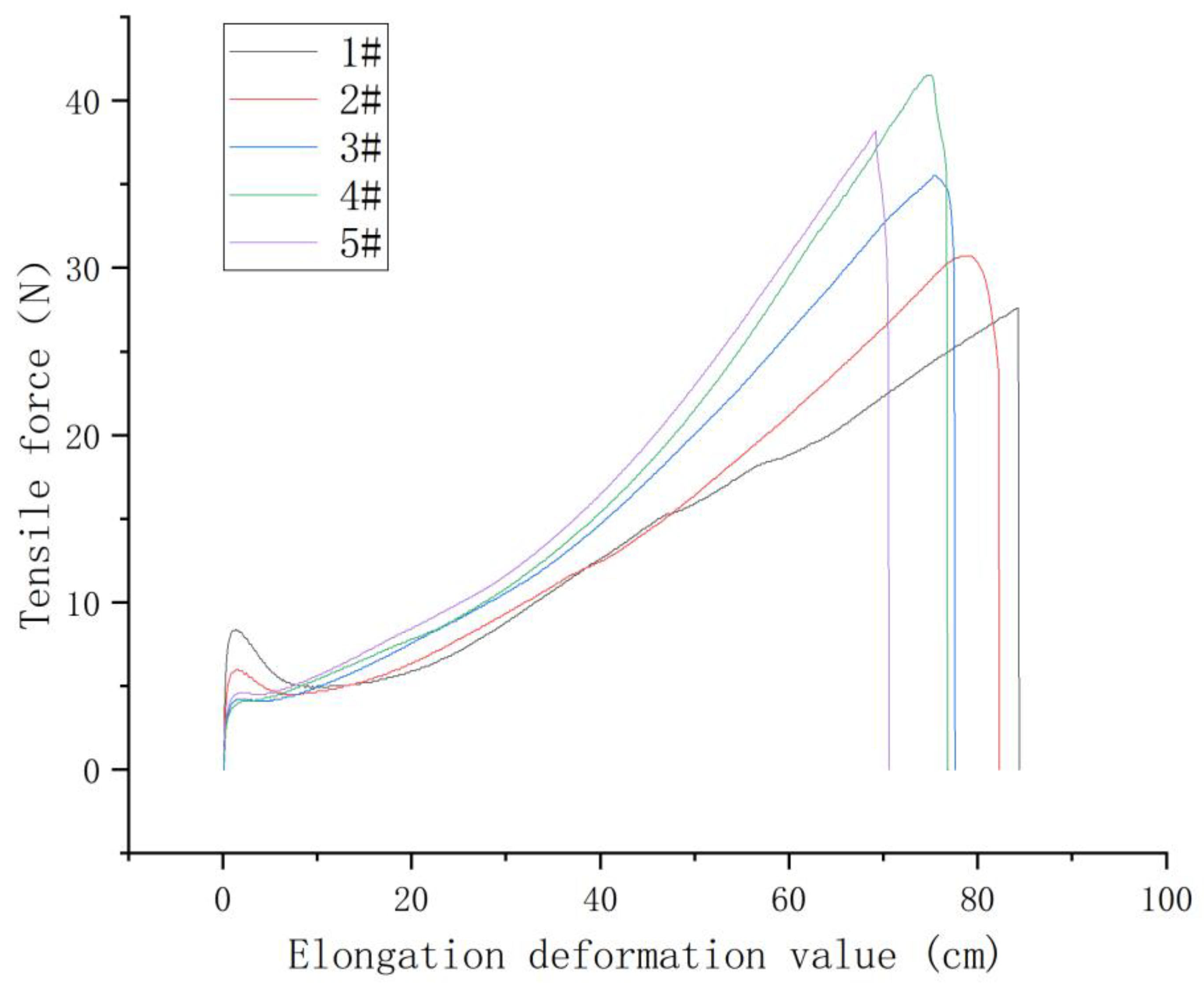

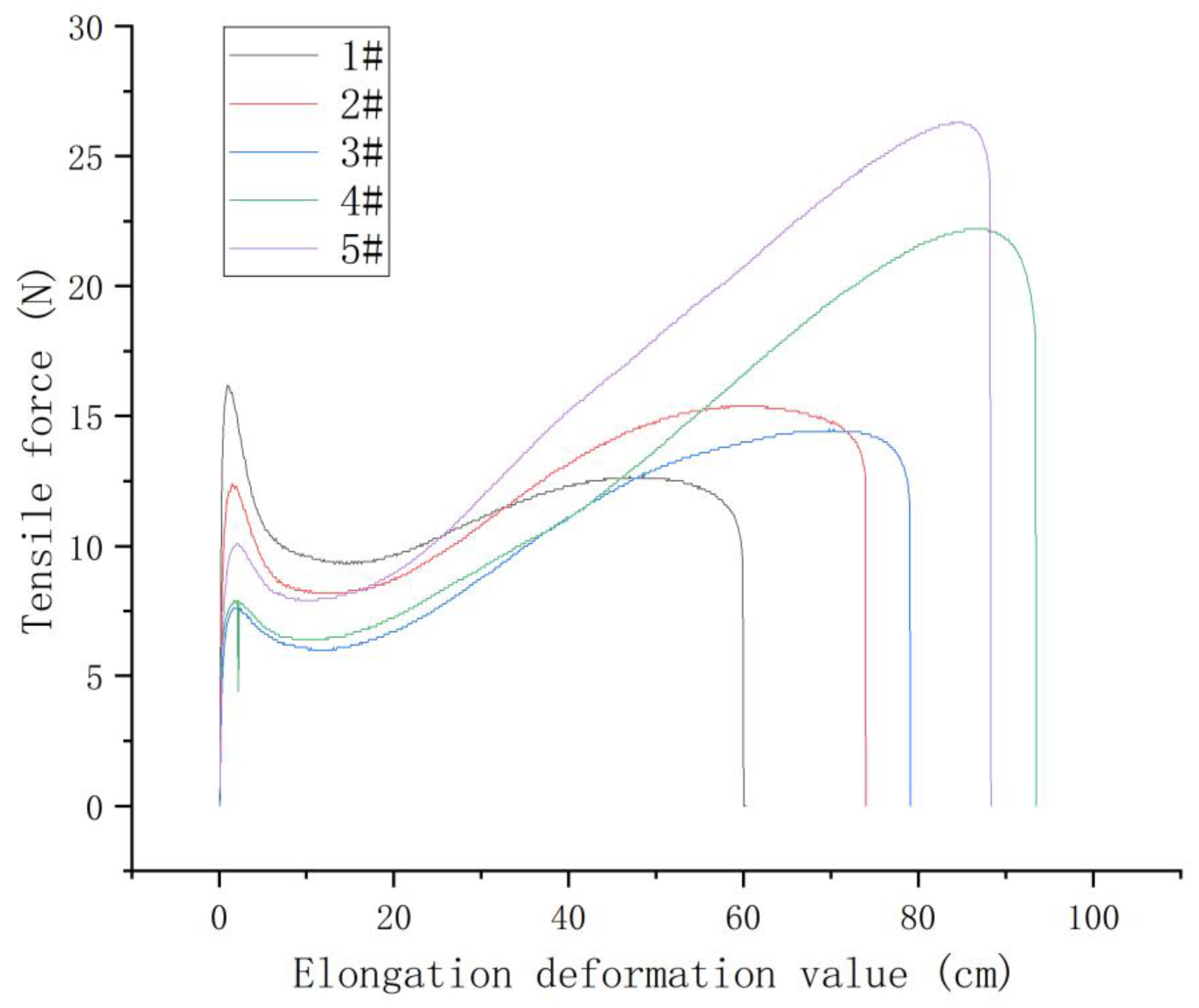

Throughout the lifespan of asphalt concrete, internal stresses arise that resist deformation due to factors like self-weight and thermal contraction. If the stiffness modulus of the asphalt is excessively high, these internal stresses may not be enough to counter external forces, resulting in cracking. To assess the deformation resistance of various modified asphalts under low temperatures and external tensile forces, a force ductility test was performed at a rate of 5 cm/min in a water-immersed setting at 5°C. The changes in tensile force during the stretching of asphalt samples, both before and after aging, were monitored, with the results illustrated in

Figure 9 and

Figure 10.

Figure 9 indicates that two peaks occur during the tensile process of modified asphalt, a typical characteristic of SBS-modified asphalt. The first peak signifies the failure of the asphalt matrix or the initial rupture of the polymer network, leading to a reduction in tensile force. As stretching continues, the polymer network reconfigures, causing the tensile force to rise again. However, when the elastic chains in the polymer break, the tensile force drops sharply. Increasing the modifier dosage results in a gradual increase in the tensile force at the rupture point, as a higher modifier content creates a denser network structure. This process generates more new physical cross-linking and entanglement points, which raises the tensile force needed for creep deformation and improves the deformation resistance of the modified asphalt. Additionally, the figure shows that as the modifier content increases, the elongation at the rupture point decreases. This is primarily due to the internal cohesive force of the modified asphalt being stronger than the adhesion force between the asphalt and the mold. When the tensile force reaches a certain threshold, it can lead to stripping from the contact surface of the ductility mold.

Figure 10 illustrates the tensile stress of aged asphalt samples at low temperatures with different amounts of modifiers. All samples showed reduced tensile forces at the rupture point after short-term aging compared to their initial states (refer to

Figure 9). This decrease is due to the high-temperature aging process, which compromises the structural integrity of the modifiers in the asphalt, resulting in broken polymer chains that are less effective in providing strength. Furthermore, as the amount of modifier increases, the elongation deformation value also rises, suggesting an improvement in the tensile strength of the modified asphalt. Importantly, no de-molding was observed during this process.

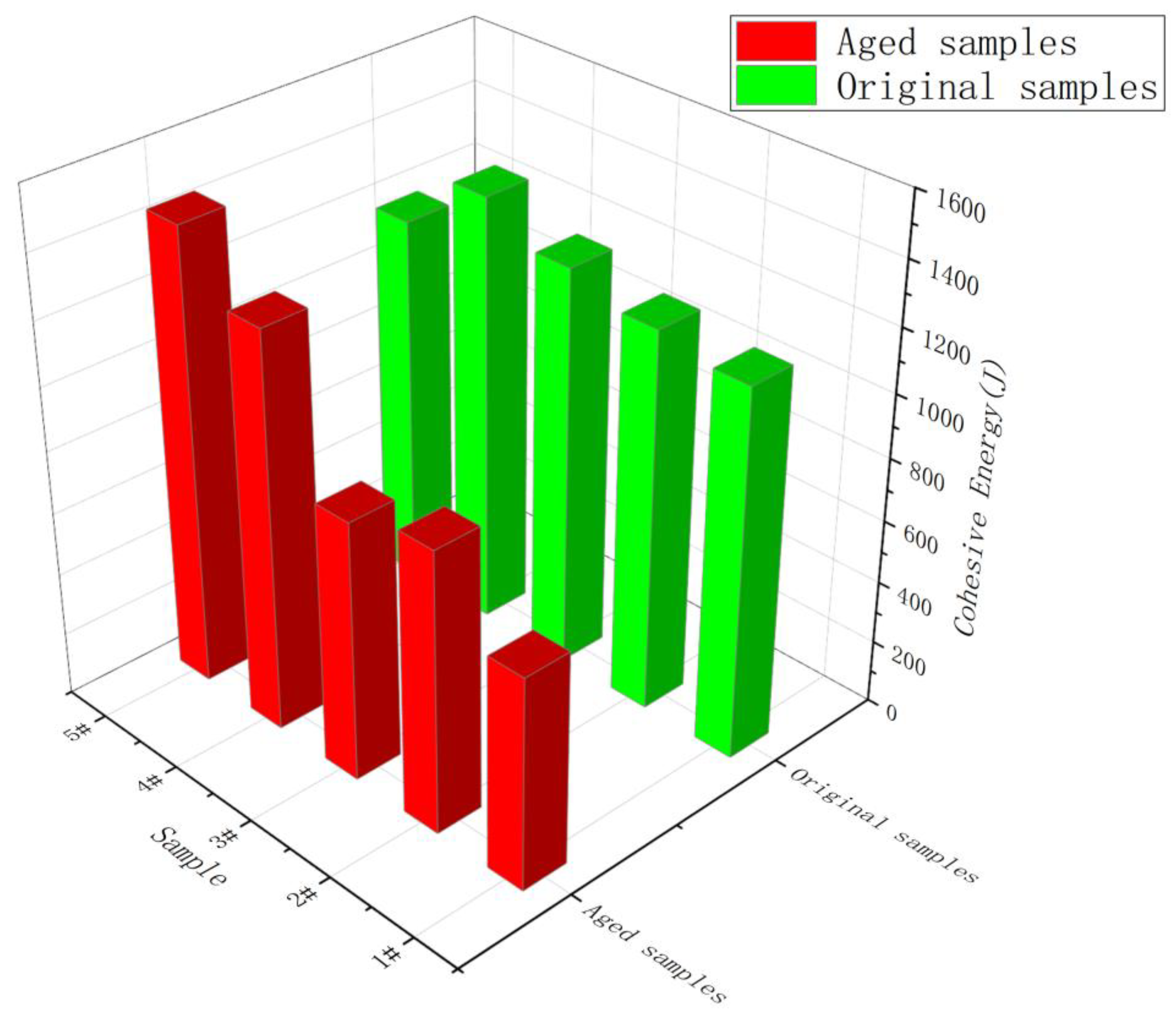

The standard DB32/T 4861-2024 outlines a method for assessing the cohesive properties of modified asphalt through a force-ductility test. This method indicates that the force-displacement curve generated when modified asphalt is subjected to tensile forces can reflect its cohesive properties. The area beneath this curve represents the cohesive energy of the modified asphalt. In this study, we adhered to this standard to analyze the changes in cohesive energy of asphalt samples with varying modifier dosages before and after aging, as depicted in

Figure 11. Cohesive energy serves as an indicator of the tensile strength and fracture toughness of modified asphalt. Higher cohesive energy correlates with greater resistance to fracture and improved durability [

20]. As shown in the figure, while the cohesive energy of modified asphalt before aging remains relatively stable with increasing modifier dosage, a significant increase is noted after aging. This suggests that a higher modifier dosage enhances the durability of modified asphalt and markedly improves its crack resistance at low temperatures.

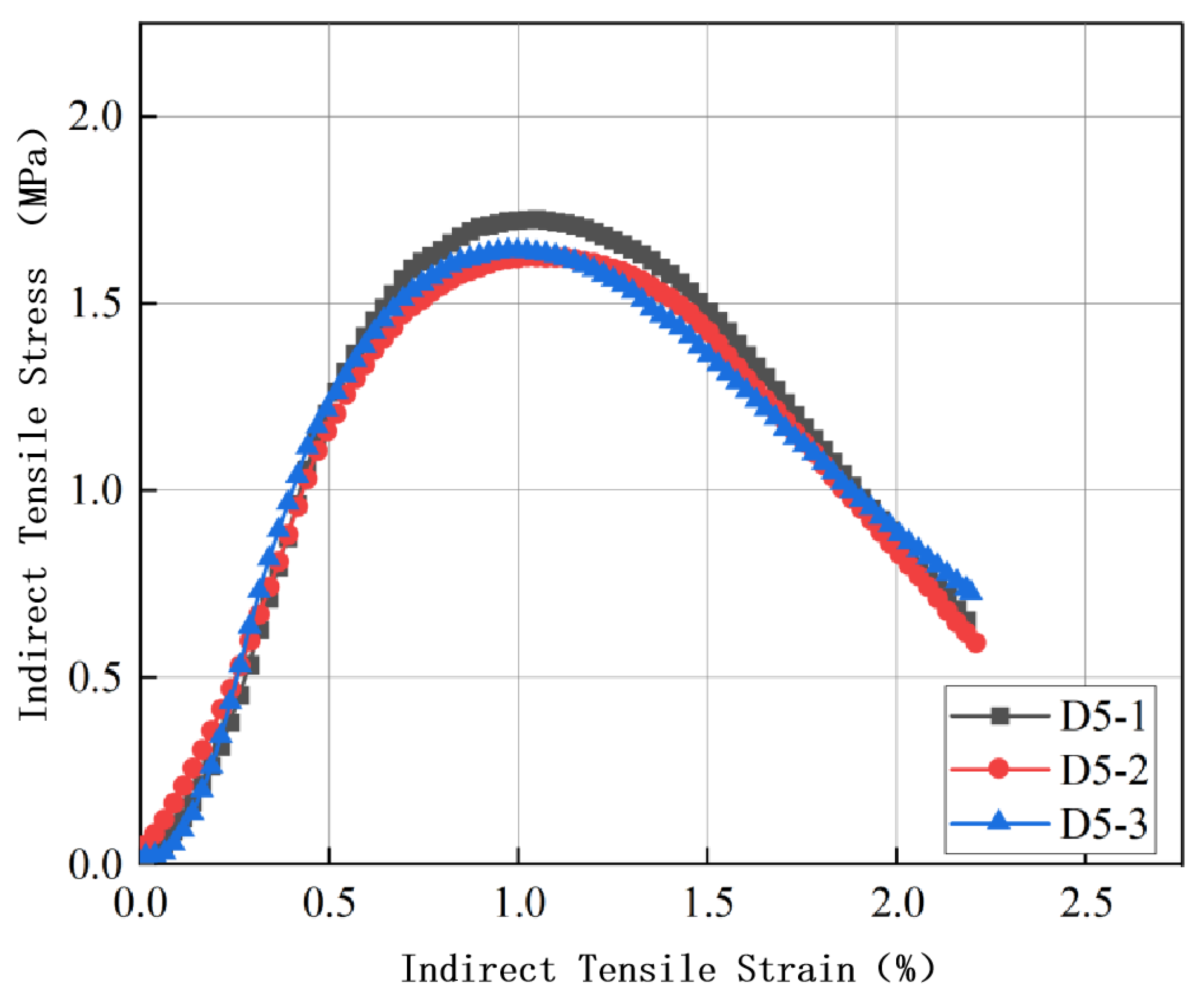

3.4. Performance Study of Modified Asphalt in Impermeable Layer Asphalt Concrete

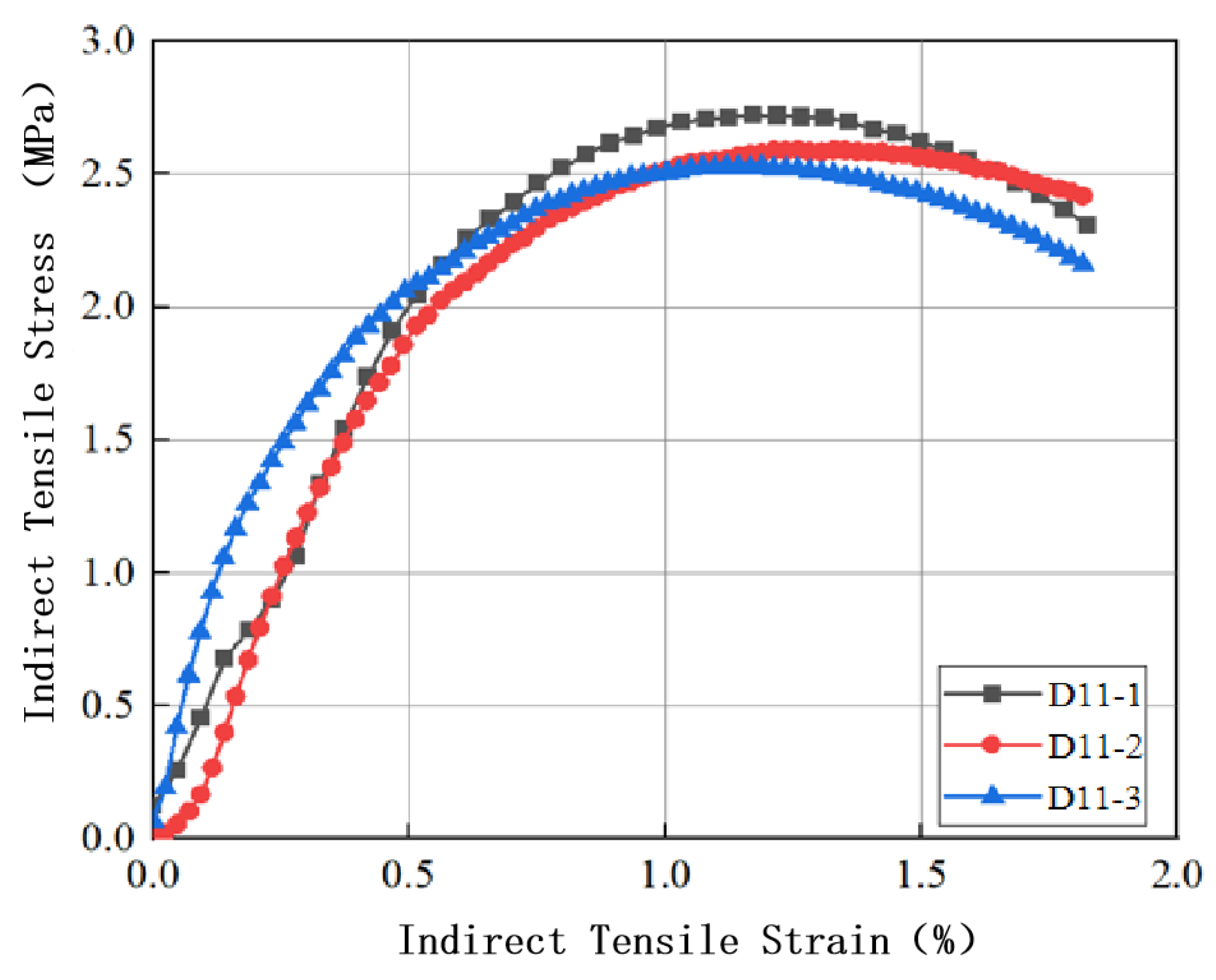

3.4.1. Concrete Mix Design

To evaluate the performance of the optimized modified asphalt mixture, the study followed the guidelines outlined in the "Test Code for Hydraulic Asphalt Concrete" (DL/T 5362-2018) and the "Design Code for Asphalt Concrete Panels and Core Walls in Earth and Rock-fill Dams" (NB/T 11015-2022). The gradation index was set at 0.30, the maximum aggregate size was 16 mm, the filler content was 14%, and the asphalt-to-stone ratio was 7.0%. Modified asphalt No. 2 (SBS I-A) served as the binder, and asphalt concrete samples were created for comparison with SG70 asphalt to examine the impact of different asphalts on porosity, splitting tensile strength, and strain. The mix design parameters are detailed in

Table 7, while the test results are shown in

Table 8 and illustrated in

Figure 12 and

Figure 13.

The test results indicate that both SG70 and SBS I-A modified asphalt have a porosity of less than 2%. Additionally, the indirect tensile strength of SBS I-A modified asphalt surpasses that of SG70 asphalt.

3.4.2. Water Stability Test

As per Clause 7.21 of the "Test Code for Hydraulic Asphalt Concrete" (DL/T 5362-2018), a water stability test was performed. A set of specimens measuring Φ100×100 mm was split into two groups. The first group was maintained at a stable temperature of 20±1°C in the air for at least 48 hours prior to the compressive strength test. The second group was immersed in water at 60±1°C for 48 hours, followed by a 4-hour period at a stable temperature of 20±1°C in water before the compressive strength test. The water stability coefficient is determined by the ratio of the compressive strength of the two groups, with a testing deformation rate of 1.0 mm/min. The results of the water stability test for SG70 and modified asphalt are presented in

Table 9.

As indicated in

Table 9, the water stability coefficient for hydraulic modified asphalt concrete exceeds 0.9, satisfying the design code requirements. In comparison to SG70 asphalt concrete, the modified asphalt SBS I-A concrete demonstrates superior water stability.

3.4.3. Slope Flow Test

The slope flow test utilized Marshall compacted specimens to evaluate the performance of two different types of asphalt binders. Six parallel specimens, each measuring 63.5 mm ± 1.3 mm in height, were prepared. After molding, the specimens were allowed to rest at room temperature for 24 hours. Each specimen was then affixed to the slope stability test frame using a high-temperature resistant adhesive. The slope of the test frame was set to 1:1.7. The oven was preheated to the testing temperature, maintaining a temperature error within ±1°C, specifically set at 70°C. Prior to placing the slope flow instrument in the oven, the displacement gauge was adjusted to touch the specimen, and the initial readings for each specimen were recorded. The slope flow instrument was then carefully placed into the preheated oven. The specimens were maintained at a constant temperature for 24 and 48 hours, respectively, and the deformation values for each specimen were documented. The results of the tests are presented in

Table 10.

Table 10 shows that the slope flow values for both types of asphalt concrete are below 0.8 mm, which satisfies the design specifications. When compared to SG70 asphalt concrete, the slope flow value of modified asphalt SBS I-A concrete is lower, suggesting that the modified asphalt exhibits superior high-temperature performance with the same mix design.

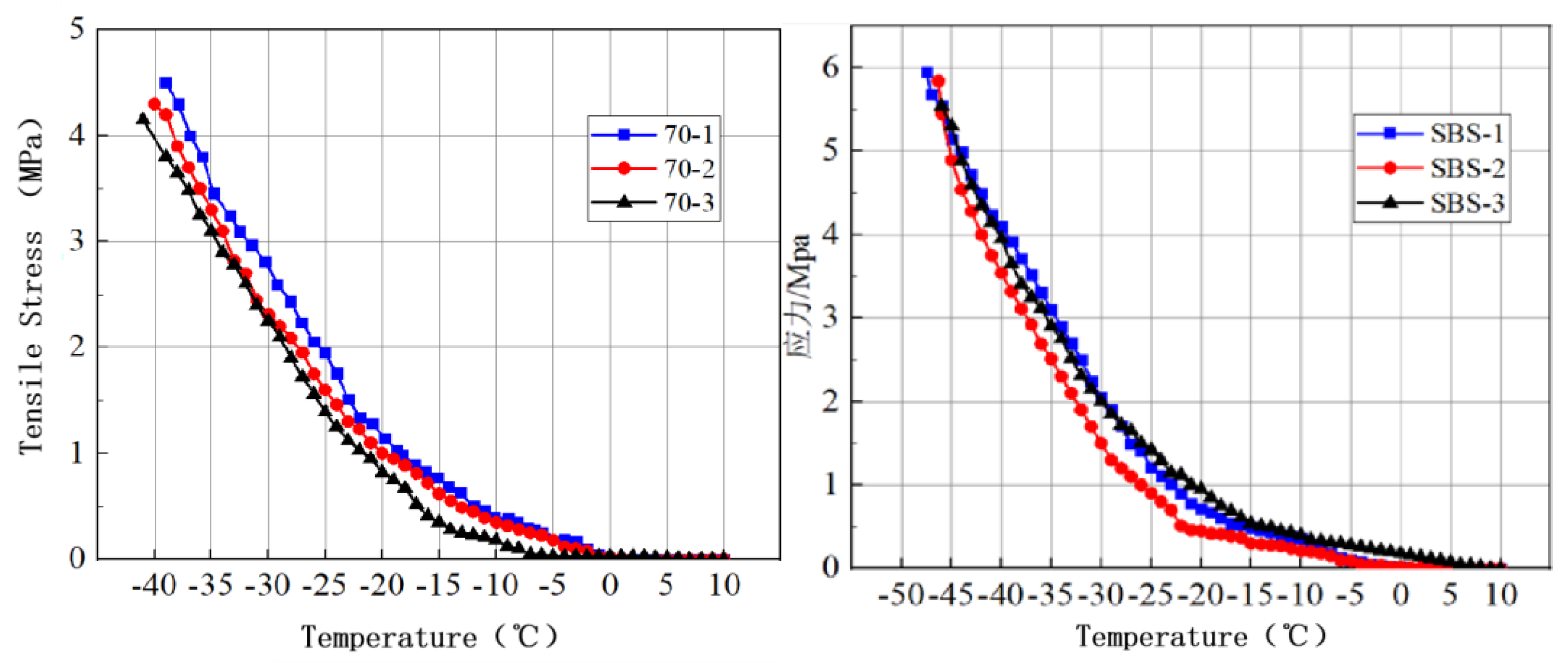

3.4.4. Freeze-Break Test

Following the guidelines of DL/T 5362-2018 "Test Code for Hydraulic Asphalt Concrete," slab specimens were created and subsequently cut into 220 mm specimens with a porosity of less than 2.0%. These specimens were maintained at a stable temperature of 10°C for a minimum of 1 hour. During the freeze-break testing, the specimen's length was fixed, and the temperature was lowered at a rate of 30°C per hour. The contraction force produced by the specimen as the temperature dropped was recorded by a computer via a sensor and converted into stress based on the specimen's cross-sectional area. The outcomes of the freeze-break test are presented in

Table 11, while the corresponding freeze-break test curves are illustrated in

Figure 14.

Figure 14 illustrates the Freeze-Break Test Curves for two types of asphalt concrete. The results demonstrate that SBS modified hydraulic asphalt has outstanding resistance to cracking at low temperatures, with the freeze-breaking temperature of the asphalt concrete dropping below -46°C. As depicted in

Table 5 and

Table 6 and

Figure 3 and

Figure 4, under identical experimental conditions, the pattern of contraction stress in relation to temperature is similar for asphalt concrete made from SG70 and modified asphalt SBS I-A. Between 10°C and -20°C, the stress increases gradually as the temperature decreases, but after -20°C, the stress escalates sharply with further temperature drops. Given that the brittle point temperature for SG70 asphalt is -21.3°C and for modified asphalt SBS I-A is -37.6°C, both the brittle point temperature of the asphalt and the freeze-breaking temperature of the asphalt concrete show a similar trend. This indicates that a lower brittle point in asphalt corresponds to a lower freeze-breaking temperature in the associated asphalt concrete, demonstrating a strong correlation between the two.

4. Conclusions

This study develops a formulation for crack-resistant hydraulic asphalt suitable for ultra-low temperatures using Response Surface Methodology and establish a predictive model with the brittle point as the response variable. Using this model, modified asphalts with varying brittle point values were produced, and their characteristics were examined. The findings are summarized as follows:

1)The impact of modifiers and stabilizers on the brittle point, softening point, and segregation value (the difference in softening point after 48 hours) of modified asphalt was analyzed. The trends observed revealed distinct patterns.

2)The optimization of hydraulic modified asphalt was carried out using response surface methodology, with modifiers, stabilizers, and compatibilizers as independent variables and the brittle point as the response variable. The Box-Behnken model was utilized for the experimental design. After fitting the data through multiple regression, the regression model showed an R² value of 0.9897 and a p-value of 0.0002, indicating that the response surface methodology is very effective for predicting the brittle point. The p-values for the three independent variables were all below 0.05, with their influence on the brittle point ranked as follows: modifiers > compatibilizers > stabilizers.

3)By controlling the amount of modifiers, five groups of SBS modified asphalt that met standard specifications were produced, and tests on low-temperature crack resistance and tensile properties were performed. The results indicated a strong correlation between the amount of modifiers and the brittle point before and after aging, with higher amounts leading to lower brittle points. Additionally, when assessing tensile properties at low temperatures using force ductility, it was found that increasing the modifier dosage also increased the tensile force at fracture, thereby improving low-temperature tensile characteristics. By analyzing the area under the force-displacement curve from the force ductility test and calculating the cohesive energy of the modified asphalt, it was shown that higher modifier amounts significantly enhance the cohesive energy of aged modified asphalt, suggesting that increased modifier dosage can greatly enhance the durability and crack resistance of asphalt.

4)When hydraulic modified asphalt was applied in asphalt concrete for impermeable layers, a gradation index of 0.30 and an asphalt-to-stone ratio of 7.0% were chosen, using No. 2 hydraulic modified asphalt as the binder. Comparisons with SG70 asphalt were made to evaluate water stability, slope flow, and freeze-breaking tests. The water stability test revealed that the water stability coefficient of hydraulic modified asphalt concrete exceeded 0.9, meeting design code requirements. In comparison to SG70 asphalt concrete, the modified asphalt SBS I-A concrete demonstrated superior water stability. The slope flow value for hydraulic modified asphalt concrete was 0.47 mm, which was lower than that of SG70 asphalt concrete. The freeze-breaking test showed that the freeze-breaking temperature of hydraulic modified asphalt reached -46.7°C, significantly lower than that of SG70 asphalt.

Funding

Supported by the Open Research Fund of Key Laboratory of Engineering Materials of Ministry of Water Resources, China Institute of Water Resources and Hydropower Research. Grant number: EMF202406.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments are extended to Professor Jing Dongand Professor Zhiyuan Ningfrom Xi'an University of Technology for their support in the laboratory data detection of asphalt mixtures.

References

- Shangwen Shi, Yu Hu,Ji Zhang, Shanqing Lu, et al. Enhancing asphalt-based waterproof materials for building cement substrates: Modifications, construction, and weathering resistance.Construction and Building Materials, 2024; Volume 441, Article number: 137537. [CrossRef]

- Guojing Huang, Zixuan Chen, Shuai Wang, et al. Investigation of fracture failure and water damage behavior of asphalt mixtures and their correlation with asphalt-aggregate bonding performance. Construction and Building Materials,2024; Volume 449, Article number: 138352. [CrossRef]

- Laura González Maturana, Alexandra Ossa López. Determination and assessment of the linear viscoelastic range and viscoelastic properties of modified asphalt and mastics under different temperature conditions. Construction and Building Materials,2024; Volume 420, Article number: 135606. [CrossRef]

- Lu Sun, Xiantao Xin, Jiaolong Ren. Asphalt modification using nano-materials and polymers composite considering high and low temperature performance.Construction and Building Materials, 2017; Volume 133, pp. 358-366. [CrossRef]

- Xiaote Shi, Chundi Si, Kewei Yan, et al. Research on the low-temperature performance of basalt fiber-rubber powder modified asphalt mixtures under freeze-thaw in large temperature differences region. Scientific Reports,2024; Volume 14, Article number: 30580. [CrossRef]

- Qing Zhang, Dehua Hou, Zhongyu Li, et al. Evaluation of the Thermal Stability and Micro-Modification Mechanism of SBR/PP-Modified Asphalt. Polymers, 2024; Volume16(4), 456. [CrossRef]

- Hu Shao, Jianya Tang, Wenzheng He, et al. Study on aging mechanism of SBS/SBR compound-modified asphalt based on molecular dynamics. Reviews on Advanced Materials Science. [CrossRef]

- Yujuan Zhang , Xukang Deng , Peng Xiao, et al.Properties and interaction evolution mechanism of CR modified asphalt. Fuel,2024;Volume 371,Article number: 131886. [CrossRef]

- Han Fu, Junrui Chai, Zengguang Xu, et al. Research on material selection and low-temperature anti-cracking mechanism of hydraulic asphalt concrete panels in the alpine region.Construction and Building Materials, 2024; Volume 423, Article number: 135830. [CrossRef]

- Lai Zhao, Gao Xu, et al. Research of the low temperature crack resistance for the mineral fiber rein-forced asphalt mixture(Conference Paper).Applied Mechanics and Materials, 2011; Volume 97-98, pp. 172-175. [CrossRef]

- MohammadZia Alavi, Elie Y Hajj , Peter E Sebaaly. A comprehensive model for predicting thermal cracking events in asphalt pavements(Article). International Journal of Pavement Engineering,2017; Volume 18, pp. 871-885. [CrossRef]

- Fengwei Ning, Chunhua Mao, Wei Sui, et al. Research on Bending Properties and Triaxial Static and Dynamic Characteristics of SBS Modified Asphalt Concrete of Impervious Layer in Cold Regions. Hydropower and Pumped Storage, 2024; Volume 10,pp.100-114.

- Zhengxing Wang, Zenghong Liu, Jutao Hao. Research of factors affecting the low-temperature cracking resistance of hydraulic asphalt concrete. Journal of China Institute of Water Resources and Hydropower Research, 2016; Volume 14, pp.311-315.

- Sheriff Lamidi, Nurudeen Olaleye, Yakub Bankole, et al. Applications of Response Surface Methodology (RSM) in Product Design, Development, and Process Optimization. Response Surface Methodology - Research Advances and Applications. Open access peer-reviewed chapter,2022. [CrossRef]

- Xiacrcheng Zai, Pan Ding, Yurta Lei , Optimal design Of gradation Of high—volume RAP plant-mixed hot-recycled asphalt mixture based on response surface methodology, Journal of Lanzhou University of Technology, 2016; Volume 19, pp.119-128.

- Qiao Xu, Renbing Liu. Study on the Performance of PPA-SBR Composite Modified Asphalt Based on Response Surface Methodology. Hunan Transportation Science and Technology, 2024; Volume 50, pp.24-30.

- Nanxuan Qian, Wei Luo, Yong Ye, et al. Effects of the ductility and brittle point of modified asphalt on the freeze-break behavior of asphalt concrete: A 3D-mesoscopic damage FE model. Construction and Building Materials, 2023; Volume386, Article number: 131555. [CrossRef]

- Huanan Yu, Xianping Bai, Guoping Qian, et al. Impact of ultraviolet radiation on the aging properties of SBS-modified asphalt binders. Polymers, 2019, Volume11, Article number: 31266171. [CrossRef]

- Yan Zhou, Kai Zhang, Shuan-fang Chen, et al. Research on force ducti li ty test Of modified asphalt. Journal of Changan University (Natural Science Edition), 2012, Volume32, pp.30-39.

- Renhui Wang , Fengwei An, Yang Zheng, et al. Study on DurabiIity Evaluation Method of Modified Asphalt Based on Cohesion Energy. Petroleum Asphalt, 2024, Volume38, pp.23-27.

Figure 2.

Effect of Modifier and Stabilizer Dosage on Softening Point.

Figure 2.

Effect of Modifier and Stabilizer Dosage on Softening Point.

Figure 3.

Effect of Modifier and Stabilizer Dosage on Brittle Point.

Figure 3.

Effect of Modifier and Stabilizer Dosage on Brittle Point.

Figure 4.

Effect of Modifier and Stabilizer Dosage on Segregation (48-hour Softening Point Difference).

Figure 4.

Effect of Modifier and Stabilizer Dosage on Segregation (48-hour Softening Point Difference).

Figure 5.

Interaction Between Modifier and Stabilizer Dosage on Brittle Point.

Figure 5.

Interaction Between Modifier and Stabilizer Dosage on Brittle Point.

Figure 6.

Interaction Between Modifier and Compatibilizer Dosage on Brittle Point.

Figure 6.

Interaction Between Modifier and Compatibilizer Dosage on Brittle Point.

Figure 7.

Interaction Between Compatibilizer and Stabilizer Dosage on Brittle Point.

Figure 7.

Interaction Between Compatibilizer and Stabilizer Dosage on Brittle Point.

Figure 8.

Brittleness Point of Samples with Different Modifier Dosages.

Figure 8.

Brittleness Point of Samples with Different Modifier Dosages.

Figure 9.

Relationship between Tensile force and Elongation deformation value of original asphalt samples.

Figure 9.

Relationship between Tensile force and Elongation deformation value of original asphalt samples.

Figure 10.

Relationship between Tensile force and Elongation deformation of aged asphalt samples.

Figure 10.

Relationship between Tensile force and Elongation deformation of aged asphalt samples.

Figure 11.

Cohesive Energy of Original and Aged Asphalt Samples.

Figure 11.

Cohesive Energy of Original and Aged Asphalt Samples.

Figure 12.

Splitting Test Curves of Asphalt Concrete Mix Design with SG70 Asphalt.

Figure 12.

Splitting Test Curves of Asphalt Concrete Mix Design with SG70 Asphalt.

Figure 13.

Splitting Test Curves of Modified Asphalt Concrete Mix Design.

Figure 13.

Splitting Test Curves of Modified Asphalt Concrete Mix Design.

Figure 14.

Freeze-Break Test Curves for two types of asphalt concrete.

Figure 14.

Freeze-Break Test Curves for two types of asphalt concrete.

Table 1.

Indicators of Base Asphalt.

Table 1.

Indicators of Base Asphalt.

| Technical Indicator |

Unit |

Test Results |

| Penetration@ 25°C, (100g, 5s) |

0.1mm |

68 |

| Softening Point (Water Bath) |

℃ |

47 |

| Ductility(5cm/min) |

@10°C |

cm |

95 |

| @15°C |

>150 |

| Flash Point |

℃ |

270 |

| wax content |

% |

1.1 |

| Brittle Point |

℃ |

-15 |

| Thin Film Oven Test |

Mass Change |

% |

-0.190 |

| Residual Penetration Ratio |

% |

68 |

| Residual Ductility |

cm |

8 |

Table 2.

Indicators of SBS.

Table 2.

Indicators of SBS.

| Technical Indicator |

Unit |

Test Results |

| Styrene Content |

30 |

Wt/% |

| Volatile Content |

0.37 |

Wt/% |

| 300% Tensile Stress at Fixed Elongation |

2.38 |

MPa |

| Tensile Strength |

20 |

MPa |

| Breaking Elongation |

740 |

% |

| Hardness |

76 |

Shore A |

Table 3.

Factors and Levels for Response Surface Experiment.

Table 3.

Factors and Levels for Response Surface Experiment.

| Factor |

Level |

| Code |

-1 |

0 |

+1 |

| Modifier Dosage |

A |

6 |

8 |

10 |

| Stabilizer Dosage |

B |

0.3 |

0.4 |

0.5 |

| Compatibilizer Dosage |

C |

8 |

10 |

11 |

Table 4.

Response Surface Experimental Design and Results.

Table 4.

Response Surface Experimental Design and Results.

| Number |

Modifier Dosage,%

A |

Stabilizer Dosage,%

B |

Compatibilizer Dosage,%

C |

Brittle Point,°C

Y |

| 1 |

-1 |

-1 |

-1 |

-31 |

| 2 |

-1 |

1 |

-1 |

-30 |

| 3 |

-1 |

-1 |

1 |

-32 |

| 4 |

-1 |

1 |

1 |

-34 |

| 5 |

-1 |

0 |

0 |

-33 |

| 6 |

0 |

-1 |

0 |

-36 |

| 7 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

-38 |

| 8 |

0 |

0 |

-1 |

-37 |

| 9 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

-38 |

| 10 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

-37 |

| 11 |

1 |

-1 |

-1 |

-40 |

| 12 |

1 |

1 |

-1 |

-41 |

| 13 |

1 |

-1 |

1 |

-41 |

| 14 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

-43 |

| 15 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

-41 |

Table 5.

ANOVA Results for Brittle Point Response Model.

Table 5.

ANOVA Results for Brittle Point Response Model.

| Source |

Sum of Squares |

df |

Mean Squares |

F-value |

P-value |

| Model |

228.02 |

9 |

25.34 |

53.28 |

0.0002 |

| A |

211.60 |

1 |

211.60 |

444.95 |

<0.0001 |

| B |

3.6 |

1 |

3.60 |

7.57 |

0.0402 |

| C |

8.10 |

1 |

8.10 |

17.03 |

0.0091 |

| AB |

0.500 |

1 |

0.5000 |

1.05 |

0.3522 |

| AC |

0.500 |

1 |

0.5000 |

1.05 |

0.3522 |

| BC |

2.00 |

1 |

2.00 |

4.21 |

0.0956 |

| A2 |

0.5079 |

1 |

0.5079 |

1.07 |

0.3488 |

| B2 |

0.5079 |

1 |

0.5079 |

0.0167 |

0.9022 |

| C2 |

0.0079 |

1 |

0.0079 |

|

|

| Residual |

2.38 |

5 |

0.4756 |

|

|

| Cor Total |

230.40 |

14 |

|

|

|

Table 6.

Properties of Modified Asphalt.

Table 6.

Properties of Modified Asphalt.

| Technical Indicator |

Unit |

Test Results |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

| Penetration@ 25°C, (100g, 5s) |

0.1mm |

112 |

117 |

115 |

110 |

112 |

| Softening Point (Water Bath) |

℃ |

79 |

83 |

86 |

87 |

87 |

| Ductility@5°C (5cm/min) |

cm |

84 |

82 |

77 |

71 |

65 |

| Brittle Point |

℃ |

-31 |

-36 |

-40 |

-41 |

-42 |

| Dynamic Viscosity @135°C |

Pa∙s |

1.71 |

2.22 |

2.43 |

2.59 |

3.46 |

| Segregation @163°C (48h Softening Point Difference) |

℃ |

0.5 |

0.7 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

| Rotating Thin Film Oven Test |

| Brittle Point After Aging |

℃ |

-29 |

-32 |

-33 |

-35 |

-36 |

| Ductility @5°C(5cm/min) After Aging |

cm |

59 |

73 |

79 |

93 |

86 |

Table 7.

Mix Design Parameters for Asphalt Concrete with Two Different Asphalt Types .

Table 7.

Mix Design Parameters for Asphalt Concrete with Two Different Asphalt Types .

| Mix Design Number |

Gradation Parameters |

Raw Materials |

|

| Maximum Aggregate Size (mm) |

Gradation Index |

Filler Content (%) |

Asphalt-to-Stone Ratio (%) |

Coarse Aggregate |

Fine Aggregate |

Filler |

Asphalt |

|

| D5 |

16 |

0.30 |

14 |

7.0 |

Limestone Crushed Aggregate |

Limestone Manufactured Sand |

Limestone Powder |

SG70 |

|

| D11 |

|

| Modified Asphalt SBS I-A |

|

Table 8.

Splitting Test Results of Asphalt Concrete with Two Different Types of Asphalt.

Table 8.

Splitting Test Results of Asphalt Concrete with Two Different Types of Asphalt.

| Specimen Number |

Theoretical Density

(g/cm3) |

Density

(g/cm3) |

Porosity

(%) |

Indirect Tensile Strength

(MPa) |

Strain

(%) |

| D5-1 |

2.434 |

2.416 |

0.75 |

1.73 |

1.05 |

| D5-2 |

2.415 |

0.77 |

1.62 |

1.02 |

| D5-3 |

2.418 |

0.67 |

1.64 |

0.97 |

| Average |

2.417 |

0.73 |

1.66 |

1.01 |

| D11-1 |

2.436 |

2.429 |

0.30 |

2.72 |

1.17 |

| D11-2 |

2.431 |

0.22 |

2.59 |

1.26 |

| D11-3 |

2.424 |

0.49 |

2.53 |

1.12 |

| Average |

2.428 |

0.34 |

2.61 |

1.18 |

Table 9.

Results of Water Stability Test for Asphalt Concrete.

Table 9.

Results of Water Stability Test for Asphalt Concrete.

| Asphalt Type |

Curing Condition |

Compressive Strength (MPa) |

Strain Corresponding to Compressive Strength (%) |

Water Stability Coefficient |

| SG70 |

20°C constant temperature for 48h |

2.71 |

5.29 |

0.95 |

| 60°C soaked for 48h, 20°C soaked for 4h |

2.58 |

5.21 |

| Modified Asphalt |

20°C constant temperature for 48h |

2.09 |

5.49 |

0.98 |

| 60°C soaked for 48h, 20°C soaked for 4h |

2.06 |

3.94 |

Table 10.

Test Results of Slope Flow Values for Asphalt Concrete with Different Asphalt Types.

Table 10.

Test Results of Slope Flow Values for Asphalt Concrete with Different Asphalt Types.

| Specimen Number |

48h Flow Value (mm) |

Specimen Number |

48h Flow Value (mm) |

| SG70-1 |

1.158 |

SBS-1 |

0.48 |

| SG70-2 |

1.126 |

SBS-2 |

0.69 |

| SG70-3 |

1.006 |

SBS-3 |

0.57 |

| SG70-4 |

1.002 |

SBS-4 |

0.47 |

| SG70-5 |

1.043 |

SBS-5 |

0.32 |

| SG70-6 |

0.954 |

SBS-6 |

0.305 |

| Average |

1.048 |

Average |

0.473 |

Table 11.

Results of Freeze-Break Test for Asphalt Concrete with Different Types.

Table 11.

Results of Freeze-Break Test for Asphalt Concrete with Different Types.

| Specimen Number |

Density

(g/cm³)

|

Freeze-Break Strength

(MPa)

|

Freeze-Break Temperature

(℃)

|

| SG70-1 |

2.401 |

4.50 |

-39.1 |

| SG70-2 |

2.395 |

4.30 |

-40.2 |

| SG70-3 |

2.385 |

4.15 |

-41.0 |

| Average |

2.394 |

4.41 |

-40.1 |

| SBS-1 |

2.392 |

5.95 |

-47.7 |

| SBS-2 |

2.386 |

5.84 |

-46.3 |

| SBS-3 |

2.403 |

5.54 |

-46.2 |

| Average |

2.394 |

5.78 |

-46.7 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).