Submitted:

17 February 2025

Posted:

17 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Background

3. Materials and Methods

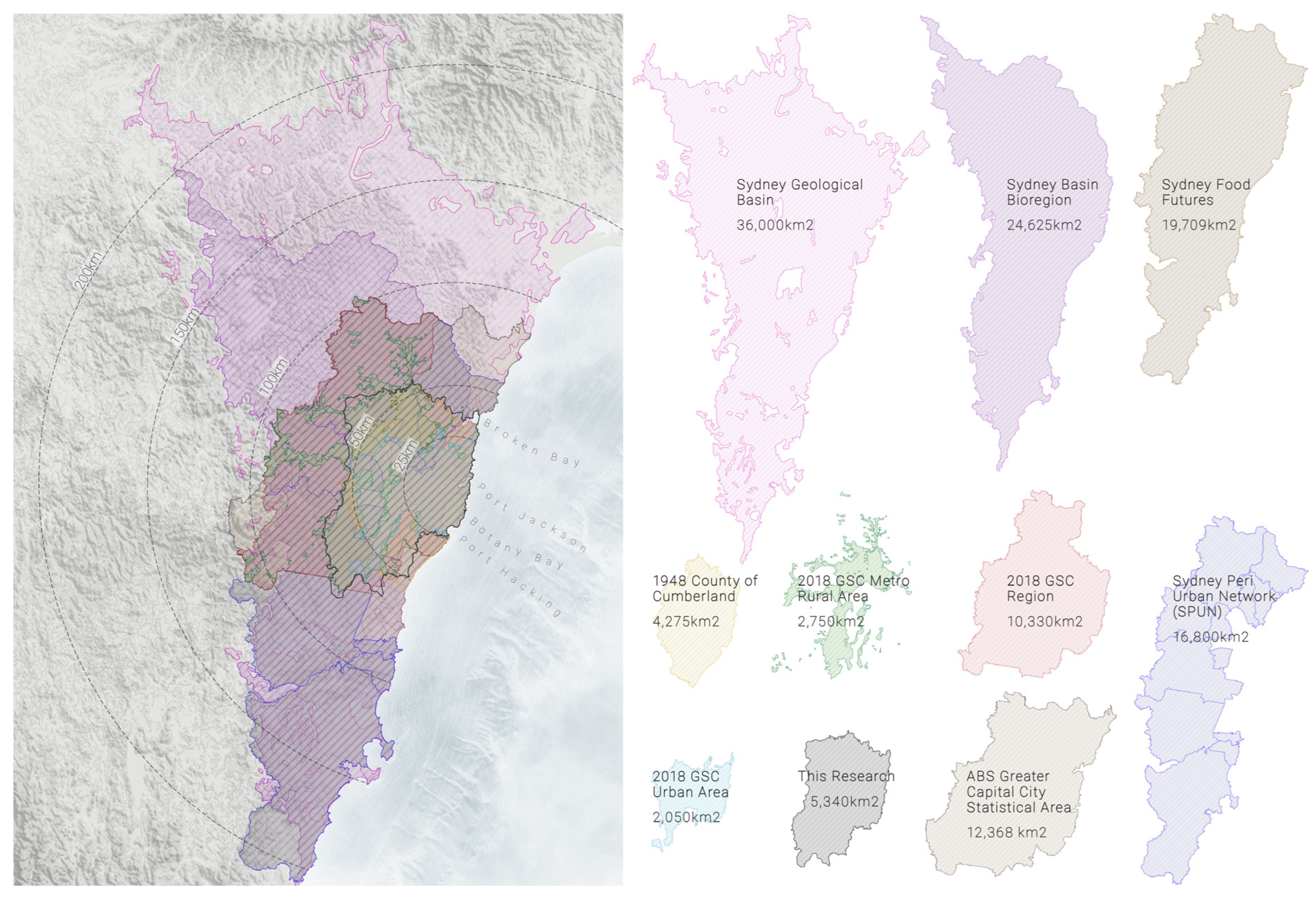

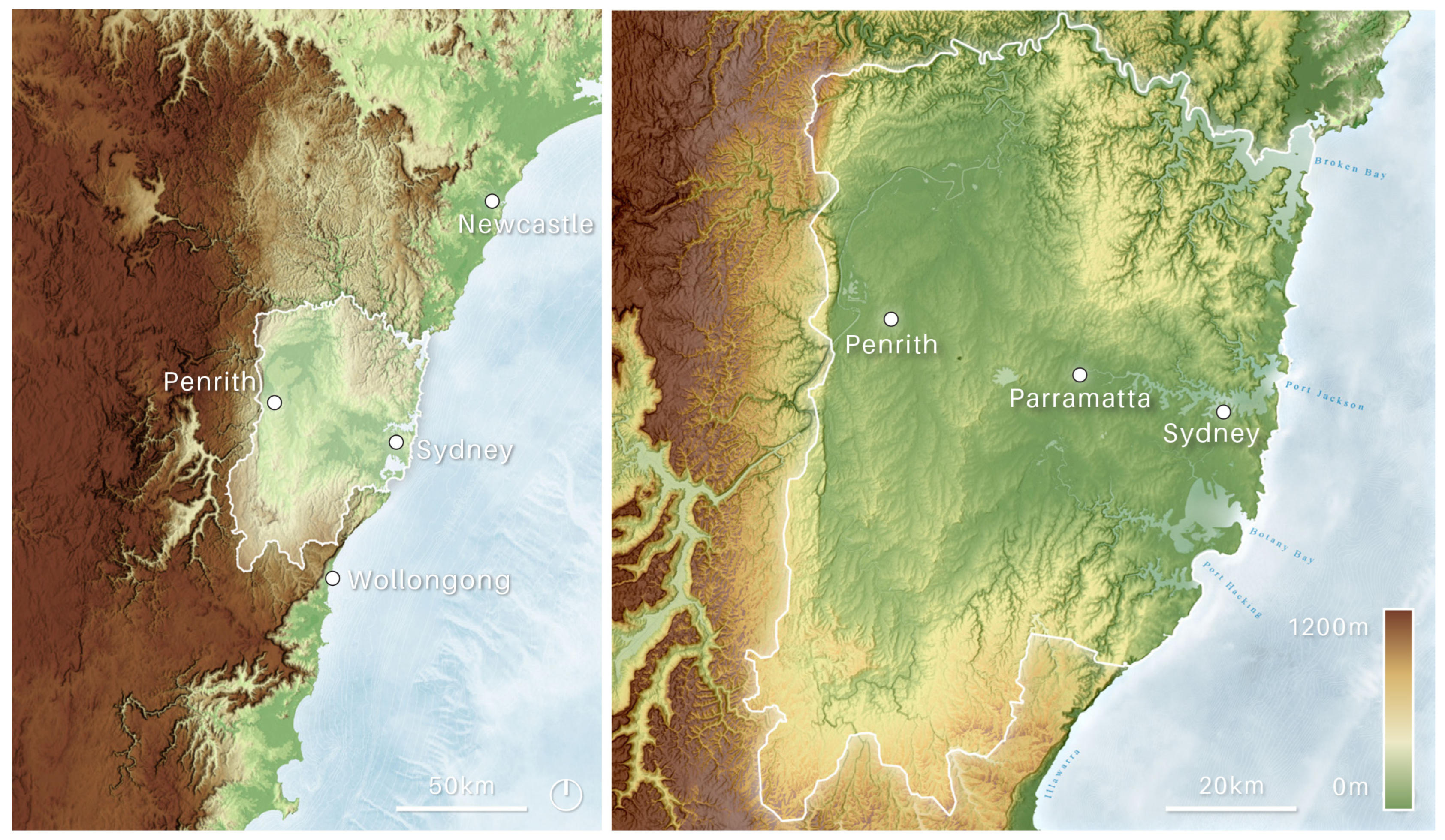

Defining and Questioning Spatial Frameworks: what’s in a boundary?

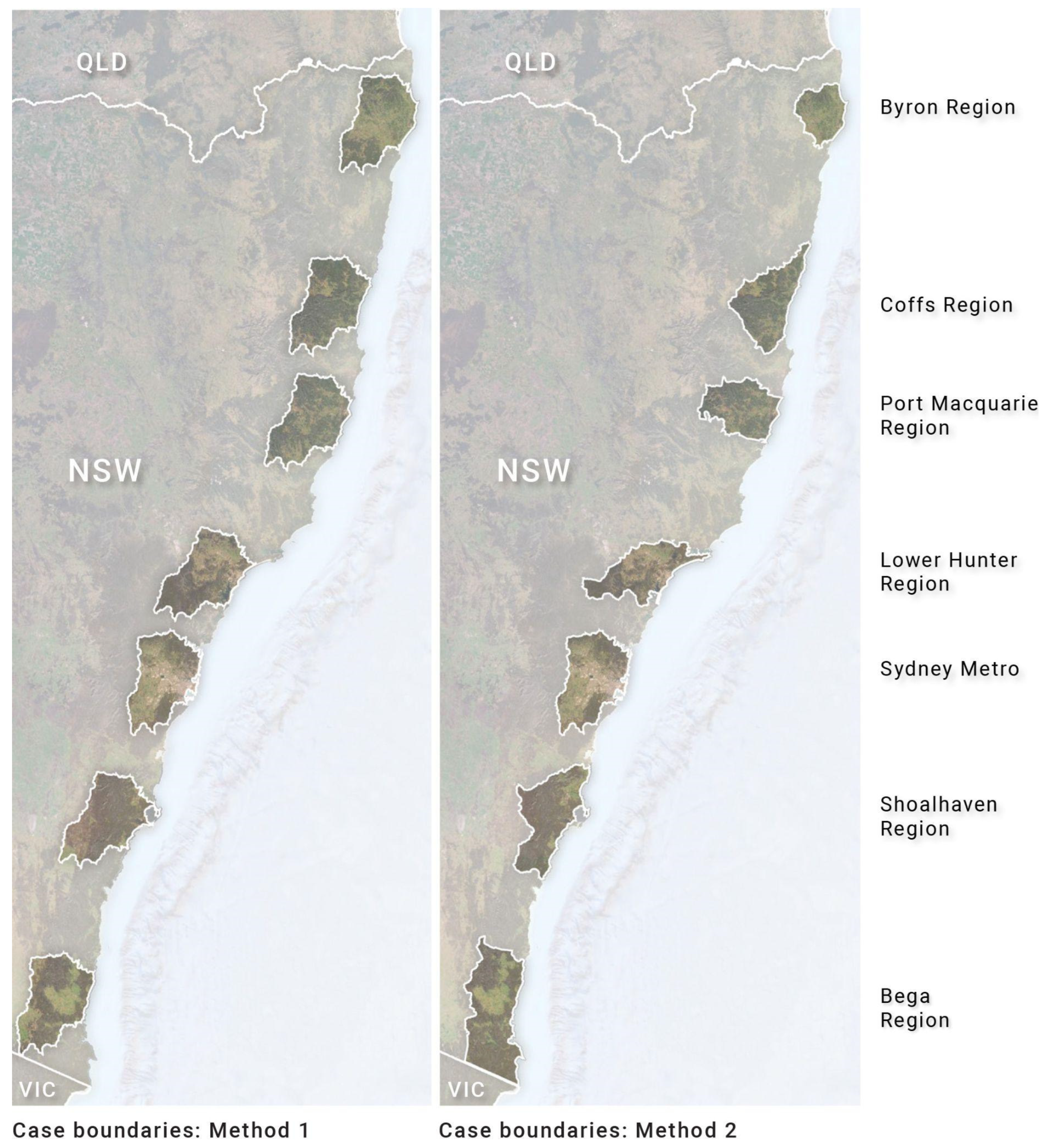

Selecting Neighbouring Agricultural Regions as Comparison Cases

Approaches to Evaluate the Seven Regions and Their Agricultural Capacity

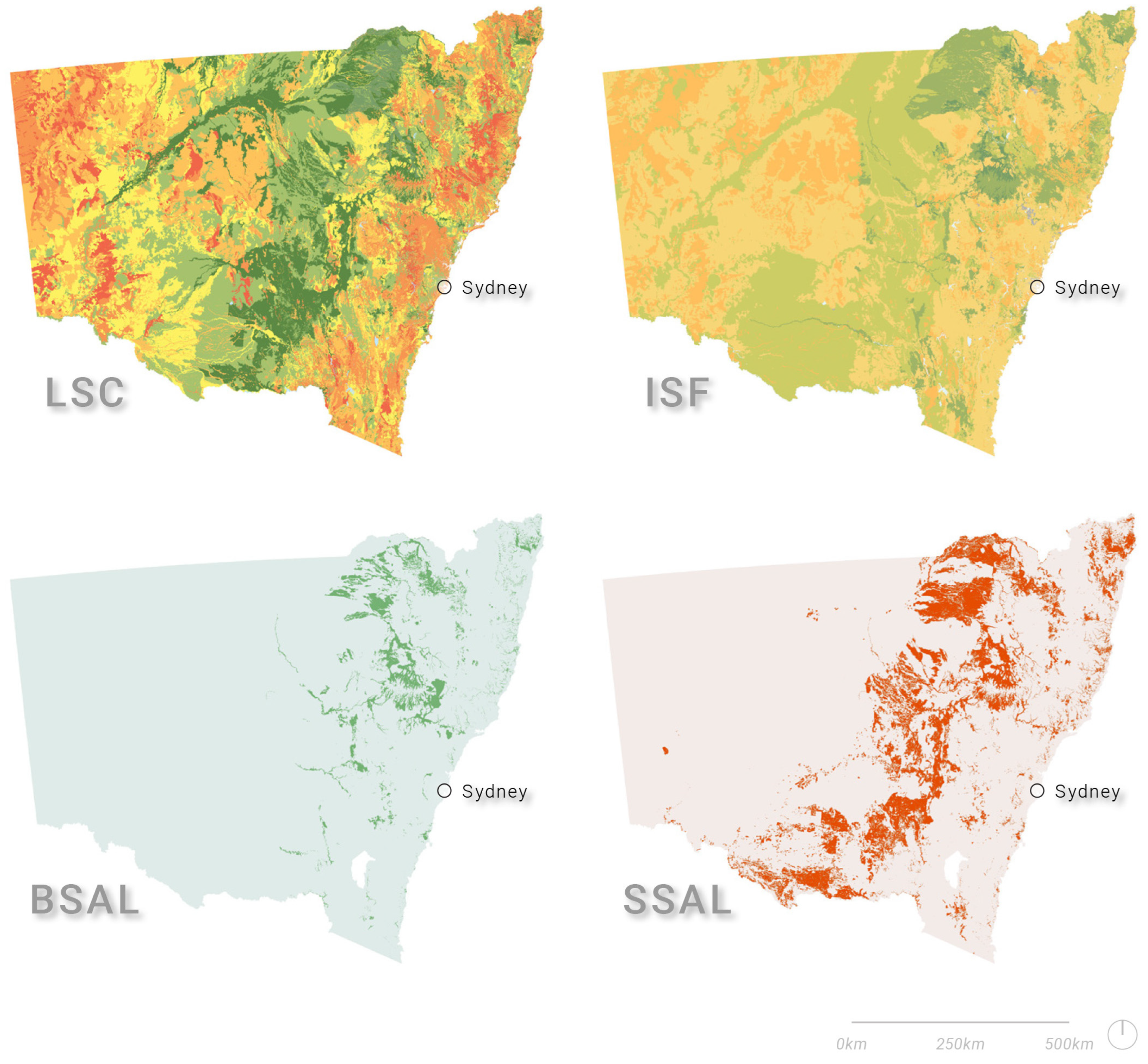

Datasets Used in the Study

Data Processessing and Visual Analyses

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zeunert, J. Dimensions of Urban Agriculture. In Routledge Handbook of Landscape and Food; Zeunert, J., Waterman, T., Eds.; London: Routledge, 2018; pp. 160–184. [Google Scholar]

- Langemeyer, J.; Madrid-Lopez, C.; Mendoza Beltran, A.; Villalba Mendez, G. Urban Agriculture — A Necessary Pathway towards Urban Resilience and Global Sustainability? Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 210, 104055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, R.; Davis, S.; Grelet, G.-A.; Gregorini, P. Agroecology for the City—Spatialising ES-Based Design in Peri-Urban Contexts. Land 2024, 13, 1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawken, S.; Rahmat, H.; Sepasgozar, S.M.; Zhang, K. The SDGs, Ecosystem Services and Cities: A Network Analysis of Current Research Innovation for Implementing Urban Sustainability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 14057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bren d’Amour, C.; Reitsma, F.; Baiocchi, G.; Barthel, S.; Güneralp, B.; Erb, K.-H.; Haberl, H.; Creutzig, F.; Seto, K.C. Future Urban Land Expansion and Implications for Global Croplands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2017, 114, 8939–8944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klusáček, P.; Martinát, S.; Charvátová, K.; Navrátil, J. Transforming the Use of Agricultural Premises under Urbanization Pressures: A Story from a Second-Tier Post-Socialist City. Land 2022, 11, 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Živanović Miljković, J.; Popović, V.; Gajić, A. Land Take Processes and Challenges for Urban Agriculture: A Spatial Analysis for Novi Sad, Serbia. Land 2022, 11, 769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, R.; James, S. Zeunert, J., Waterman, T., Eds.; Peri-Urban Agriculture in Australia: Pressure on the Urban Fringe. In Routledge Handbook of Landscape and Food; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 213–227. [Google Scholar]

- Houston, P. Re-Valuing the Fringe: Some Findings on the Value of Agricultural Production in Australia’s Peri-Urban Regions. Geogr. Res. 2005, 43, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, D.; Knowd, I. The Emergence of Urban Agriculture: Sydney, Australia. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 8 2010, 1, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawken, S.; Isendahl, C.; Strickland, K.; Barthel, S. Towards Intergenerational Neutrality in Urban Planning and Governance: Reflections on Temporality in Sustainability Transitions Research. Urban Stud. 2025, 62, 435–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molotch, H. The Political Economy of Growth Machines. J. Urban Aff. 1993, 15, 29–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ley, D. A Regional Growth Ecology, a Great Wall of Capital and a Metropolitan Housing Market. Urban Stud. 2021, 58, 297–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberger, J.; Krausmann, F.; Getzner, M.; Schandl, H.; West, J. Development and Dematerialization: An International Study. Plos One 2013, 8, e70385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cleave, E.; Arku, G. Place Branding and Growth Machines: Implications for Spatial Planning and Urban Development. J. Urban Aff. 2022, 44, 949–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellwig, T. Globalization and Perceptions of Policy Maker Competence. Polit. Res. Q. 2007, 60, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, M. Values of the Metropolitan Rural Area of the Greater Sydney Region, AgEconPlus Consulting for the NSW Department of Planning and Environment and Greater Sydney Commission 2017.

- Kimelberg, S.M. Inside the Growth Machine: Real Estate Professionals on the Perceived Challenges of Urban Development. City Community 2011, 10, 76–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlovskaya, M. Theorizing with GIS: A Tool for Critical Geographies? Environ. Plan. A 2006, 38, 2003–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeunert, J.; Daroy, A. Sydney’s Food Landscapes: Agriculture, Planning, Sustainability; Palgrave Macmillan, 2025; ISBN 978-981-96-0709-9.

- Farrelly, E. Killing Sydney: The fight for a city’s soul; Pan Macmillan: Sydney, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- James, S.; O’Neill, P. Planning for Peri-Urban Agriculture – a Geographically-Specific, Evidence Based Approach from Sydney. Aust. Geogr. 2016, 47, 173–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerritsen, R. Australia and the Origins of Agriculture; BAR Publishing: Oxford, England, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe, B.; Gammage, B. First Knowledges Country: Future Fire, Future Farming; Thames & Hudson Australia, 2021.

- Gammage, B. The Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines Made Australia; Allen & Unwin: Crows Nest, N.S.W, 2012; ISBN 9781743311325. [Google Scholar]

- Karskens, G. The Colony: A History of Early Sydney; Allen & Unwin: Sydney, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- G.S.C. Greater Sydney Region Plan: A Metropolis of Three Cities : Connecting People; Greater Sydney Commission: Parramatta NSW, 2018; ISBN 978-0-6482729-5-3.

- James, S. Protecting Sydney’s Peri-Urban Agriculture: Moving beyond a Housing/Farming Dichotomy. Geogr. Res. 2014, 52, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeunert, J.; Freestone, R. Brisotto, C., Lemes de Oliveira, F., Eds.; From Rural Lands to Agribusiness Precincts: Agriculture in Metropolitan Sydney 1948–2018. In Re-Imagining Resilient Productive Landscapes: Perspectives from Planning History; Cities and Nature; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2022; ISBN 978-3-030-90445-6. [Google Scholar]

- Budge, T. Is Food a Missing Ingredient in Australia’s Metropolitan Planning Strategies. In Food security in Australia: Challenges and prospects for the future; Farmar-Bowers, Q., Higgins, V., Millar, J., Eds.; Springer: New York, 2013; pp. 367–380. [Google Scholar]

- Malcolm, P.; Fahd, R. Ground Truthing of Sydney Vegetable Industry in 2008; Horticulture Australia Limited, NSW Department of Primary Industries: Sydney, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wynne, L.; Ruoso, L.-E.; Cordell, D.; Jacobs, B. Locationally Disadvantaged’: Planning Governmentalities and Peri-Urban Agricultural Futures. Aust. Geogr. 2020, 51, 377–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawton, A.; Morrison, N. The Loss of Peri-Urban Agricultural Land and the State-Local Tensions in Managing Its Demise: The Case of Greater Western Sydney, Australia. Land Use Policy 2022, 120, 106265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihlein, L. A Heritage Vision for Sustainable Housing Goes to ICAC, The Conversation 2014.

- Lucertini, G.; Di Giustino, G. Urban and Peri-Urban Agriculture as a Tool for Food Security and Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation: The Case of Mestre. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubbeling, M.; Zeeuw, H. de Urban Agriculture and Climate Change Adaptation: Ensuring Food Security Through Adaptation. In Resilient Cities; Otto-Zimmermann, K., Ed.; Local Sustainability; Springer Netherlands, 2011; pp. 441–449 ISBN 978-94-007-0784-9.

- Mason, D.; Knowd, I. The Emergence of Urban Agriculture: Sydney, Australia. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2010, 8, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buxton, M.; Tieman, G.; Bekessy, S.; Budge, T.; Mercer, D.; Coote, M.; Morcombe, J. Change and Continuity in Peri-Urban Australia, State of the Peri-Urban Regions: A Review of the Literature. RMIT Univ. Melb. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen, A. Institutions and Urban Space: Land, Infrastructure, and Governance in the Production of Urban Property. Plan. Theory Pract. 2017, 19, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G.S.C. Greater Sydney Region Plan: A Metropolis of Three Cities; Greater Sydney Commission: NSW Government, 2018.

- G.S.C. Western City District Plan; Greater Sydney Commission: NSW Government, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, M.W. New Lines: Critical GIS and the Trouble of the Map. Trans. GIS 2019, 23, 177–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawken, S.; Han, H.; Pettit, C. Open Cities | Open Data: Collaborative Cities in the Information Era; Palgrave Macmillan: Singapore, 2020; ISBN 978-981-13-6604-8. [Google Scholar]

- The Iconography of Landscape: Essays on the Symbolic Representation, Design, and Use of Past Environments; Cosgrove, D.E., Daniels, S., Eds.; Cambridge studies in historical geography; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge [England], 1988. ISBN 0-521-32437-8.

- Pavlovskaya, M. Critical GIS as a Tool for Social Transformation. Can. Geogr. Géographies Can. 2018, 62, 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thatcher, J.E.; Imaoka, L.B. The Poverty of GIS Theory: Continuing the Debates around the Political Economy of GISystems. Can. Geogr. Géographies Can. 2018, 62, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHarg, I. Design with Nature; John Wiley: New York, 1995; ISBN 978-0-471-11460-4. [Google Scholar]

- Geoscience Australia Surface Geology of Sydney Basin, 1:1 000 000 Scale, 2012 Edition 2012.

- UTS Food Maps | Sydney’s Food Futures. Syd. Food Futur. 2025.

- NSW Government County of Cumberland Planning Scheme Presentation Copy with Signatures / | SLNSW Collection Viewer. Available online: https://digital-stream.sl.nsw.gov.au/ie_viewer.php?is_mobile=false&is_rtl=false&dps_dvs=1739496402580~236&dps_pid=IE3744611 (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics Digital Boundary Files. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/standards/australian-statistical-geography-standard-asgs-edition-3/jul2021-jun2026/access-and-downloads/digital-boundary-files (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- Weller, R.; Bolleter, J. Made in Australia: The Future of Australian Cities; UWA Publishing: Perth, 2013; ISBN 978-1-74258-492-8. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Planning, Industry and Environment Land and Soil Capability Mapping for NSW. Available online: https://datasets.seed.nsw.gov.au/dataset/land-and-soil-capability-mapping-for-nsw4bc12 (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- NSW State Government of NSW and NSW Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water Estimated Inherent Soil Fertility of NSW - SEED. Available online: https://datasets.seed.nsw.gov.au/dataset/estimated-inherent-soil-fertility-of-nswd793e (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- NSW Department of Planning, Housing and Infrastructure Biophysical Strategic Agricultural Land. Available online: https://datasets.seed.nsw.gov.au/dataset/srlup-salbiophysical (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- NSW Department of Primary Industries Draft State Significant Agricultural Land Map. Available online: https://nswdpi.mysocialpinpoint.com/ssal/map (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- McDougall, R.; Rader, R.; Kristiansen, P. Urban Agriculture Could Provide 15% of Food Supply to Sydney, Australia, Under Expanded Land Use Scenarios. Land Use Policy 2020, 94, 104554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawton, A.; Morrison, N. The Loss of Peri-Urban Agricultural Land and the State-Local Tensions in Managing Its Demise: The Case of Greater Western Sydney, Australia. Land Use Policy 2022, 120, 106265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squires, H. Agricultural Land Use Mapping Resources in NSW - User’s Guide, NSW Department of Primary Industries, February 2017 Primefact 1538 2017.

- Pinnegar, S.; Randolph, B.; Troy, L. Decoupling Growth From Growth-Dependent Planning Paradigms: Contesting Prevailing Urban Renewal Futures in Sydney, Australia. Urban Policy Res. 2020, 38, 321–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowie, C.T.; Ding, D.; Rolfe, M.; Mayne, D.J.; Jalaludin, B.; Bauman, A.; Morgan, G. Neighbourhood Walkability, Road Density and Socio-Economic Status in Sydney, Australia. Environ. Health 2016, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeunert, J. A Multidimensional Sustainability Framework for Landscape Architecture: Are Diverse Outcomes Being Realised in Design Practice. In Routledge Handbook of Urban Landscape Research; Bishop, K., Corkery, L., Eds.; Oxon: Routledge, 2023; pp. 280–295. [Google Scholar]

- Budge, T. Is Food a Missing Ingredient in Australia’s Metropolitan Planning Strategies. In Food Security in Australia: Challenges and Prospects for the Future; Farmar-Bowers, Q., Higgins, V., Millar, J., Eds.; Springer US: Boston, MA, 2013; ISBN 978-1-4614-4484-8. [Google Scholar]

- Cordell, D.; Nelson, J.; Atherton, A.; Gadhoke, P. Who Is Responsible for Ensuring Food Security in NSW? A Brief Review of Risks, Opportunities, and Policies for Creating Resilient Food Systems and Healthy Communities in Greater Sydney.; Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology Sydney: Sydney, 2022. [Google Scholar]

| REGION | Method 1 Sydney Boundary (km2) |

Method 2 LGA Boundary (km2) |

|---|---|---|

| Byron | 5293 | 2142 |

| Coffs | 5297 | 3983 |

| Port Macquarie | 5275 | 3443 |

| Lower Hunter | 5012 | 3885 |

| Sydney | 5340 | 5340 |

| Nowra | 4974 | 4696 |

| Bega | 5318 | 6313 |

| MEAN | 5215 | 4258 |

| Dataset Name | Classes | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| LSC: Land and Soil Capability Mapping for NSW [53] | 1 - Very slight to negligible limitations 2 - Slight but significant limitations 3 - Moderate limitations 4 - Moderate to severe limitations 5 - Severe limitations 6 - Very severe limitations 7 - Extremely severe limitations 8 - Extreme limitations |

“The LSC spatially ranks land as a class between 1-8, the higher the number the "decreasing capability of the land to sustain [agricultural] landuse”, whereby “Class 1 represents land capable of sustaining most land uses including those that have a high impact on the soil (e.g., regular cultivation), whilst class 8 represents land that can only sustain very low impact landuses (e.g., nature conservation)" |

|

ISF: Estimated Inherent Soil Fertility of NSW [54] |

1 - Low 2 - Moderately low 3 - Moderate 4 - Moderately high 5 - High |

“This map provides an estimation of the inherent fertility of soils in NSW. It uses the best available soils and natural resource mapping developed for the Land and Soil Capability (LSC) dataset.” |

| BSAL: Biophysical Strategic Agricultural Land [55] | 1 - Biophysical Strategic Agricultural Land | “Biophysical Strategic Agricultural Land (BSAL) is land with high quality soil and water resources capable of sustaining high levels of productivity. BSAL plays a critical role sustaining the State’s $12 billion agricultural industry. A polygon dataset that estimates the Biophysical Strategic Agricultural Land (BSAL) within New South Wales. These lands intrinsically have the best quality landforms, soil and water resources which are naturally capable of sustaining high levels of productivity and require minimal management practices to maintain this high quality.” |

|

SSAL: Draft State Significant Agricultural Land [56] |

1 - State Significant Agricultural Land |

“The mapping is in an early draft stage. The layers used to build this map are constrained and of variable quality. This exhibition process will help collect information about what aspects of the preliminary draft map are right, and where we need to make changes”. |

| Class /Case | (best) 1 |

2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | (worst) 8 |

Total km2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Byron (km2) | 0 | 0 | 1156 | 1013 | 357 | 1386 | 991 | 372 | 4119 |

| % | 0% | 0% | 21.9% | 19.2% | 6.8% | 26.3% | 18.8% | 7.1% | 100% |

| Rank/7 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 2 | 6 | 5 | |||

| Coffs | 0 | 0 | 256 | 818 | 662 | 692 | 1290 | 1572 | 5034 |

| % | 0% | 0% | 4.8% | 15.5% | 12.5% | 13.1% | 24.4% | 29.7% | 100% |

| Rank/7 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 1 | |||

| P. Macquarie | 0 | 0 | 376 | 592 | 252 | 1363 | 1362 | 1311 | 4880 |

| % | 0% | 0% | 7.2% | 11.3% | 4.8% | 25.9% | 25.9% | 24.9% | 100% |

| Rank/7 | 2 | 5 | 7 | 3 | 4 | 2 | |||

| L.Hunter | 0 | 0 | 241 | 1255 | 820 | 645 | 1860 | 112 | 4693 |

| % | 0% | 0% | 4.9% | 25.4% | 16.6% | 13.1% | 37.7% | 2.3% | 100% |

| Rank/7 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 1 | 6 | |||

| Sydney | 0 | 0 | 115 | 2046 | 483 | 674 | 1556 | 75 | 4834 |

| % | 0% | 0% | 2.3% | 41.3% | 9.8% | 13.6% | 31.4% | 1.5% | 100% |

| Rank/7 | 6 | 1 | 5 | 6 | 3 | 7 | |||

| Shoalhaven | 0 | 0 | 167 | 541 | 678 | 1323 | 1696 | 534 | 4772 |

| % | 0% | 0% | 3.4% | 11.0% | 13.7% | 26.8% | 34.3% | 10.8% | 100% |

| Rank/7 | 7 | 6 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 4 | |||

| Bega | 0 | 0 | 56 | 358 | 1552 | 1590 | 882 | 872 | 5254 |

| % | 0% | 0% | 1.1% | 6.7% | 29.2% | 30.0% | 16.6% | 16.4% | 100% |

| Rank/7 | 7 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 3 | |||

| NSW | 0 | 14659 | 116025 | 190846 | 154928 | 174023 | 108783 | 48889 | 677469 |

| % | 0% | 1.8% | 14.4% | 23.6% | 19.2% | 21.5% | 13.5% | 6.0% | 100% |

| Class /Case | (best) 1 |

2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | (worst) 8 |

Total km2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Byron (km2) | 0 | 0 | 538 | 216 | 34 | 722 | 506 | 106 | 2123 |

| % | 0% | 0% | 25.4% | 10.2% | 1.6% | 24.2% | 28.0% | 0.2% | 100% |

| Rank/7 | 1 | 5 | 7 | =2 | =4 | =6 | |||

| Coffs | 0 | 0 | 282 | 701 | 425 | 709 | 1072 | 784 | 3974 |

| % | 0% | 0% | 7.1% | 17.6% | 10.7% | 17.8% | 27.0% | 19.7% | 100% |

| Rank/7 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 1 | |||

| P. Macq | 0 | 0 | 321 | 135 | 1064 | 775 | 897 | 6 | 3198 |

| % | 0% | 0% | 10.0% | 4.2% | 33.3% | 24.2% | 28.0% | 0.2% | 100% |

| Rank/7 | 2 | 6 | 1 | =2 | =4 | =6 | |||

| L.Hunter | 0 | 0 | 170 | 1140 | 565 | 599 | 1156 | 184 | 3814 |

| % | 0% | 0% | 4.5% | 29.9% | 14.8% | 15.7% | 30.3% | 4.8% | 100% |

| Rank/7 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 3 | 4 | |||

| Sydney | 0 | 0 | 115 | 2046 | 483 | 674 | 1556 | 75 | 4949 |

| % | 0% | 0% | 2.3% | 41.3% | 9.8% | 13.6% | 31.4% | 1.5% | 100% |

| Rank/7 | 6 | 1 | 6 | 7 | 2 | 5 | |||

| Shoalhaven | 0 | 0 | 207 | 601 | 710 | 1062 | 1545 | 529 | 4654 |

| % | 0% | 0% | 4.4% | 12.9% | 15.2% | 22.8% | 33.2% | 11.4% | 100% |

| Rank/7 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 3 | |||

| Bega | 0 | 0 | 62 | 95 | 1462 | 2390 | 1246 | 1047 | 6302 |

| % | 0% | 0% | 1.0% | 1.5% | 23.2% | 37.9% | 19.8% | 16.6% | 100% |

| Rank/7 | 7 | 7 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 2 | |||

| NSW | 0 | 14659 | 116025 | 190846 | 154928 | 174023 | 108783 | 48889 | 808153 |

| % | 0% | 1.8% | 14.4% | 23.6% | 19.2% | 21.5% | 13.5% | 6.0% | 100% |

| Class / Case | (best) 5 |

4 | 3 | 2 | (worst) 1 |

Total km |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Byron (km2) | 433 | 1929 | 728 | 1830 | 356 | 5275 |

| % | 8.2% | 36.6% | 13.8% | 34.7% | 6.7% | 100% |

| Rank/7 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| Coffs | 0 | 1035 | 1037 | 1958 | 1260 | 5290 |

| % | 0% | 19.6% | 19.6% | 37.0 | 23.8% | 100% |

| Rank/7 | =6 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 3 | |

| P. Macq | 37 | 871 | 1840 | 604 | 1907 | 5259 |

| % | 0.7% | 16.6% | 35.0% | 11.5% | 36.3% | 100% |

| Rank/7 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 7 | 1 | |

| L.Hunter | 8 | 347 | 493 | 3015 | 1053 | 4917 |

| % | 0.2% | 7.0% | 9.9% | 60.5% | 21.1.% | 100% |

| Rank/7 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 2 | 5 | |

| Sydney | 118 | 333 | 679 | 2376 | 1562 | 5068 |

| % | 2.3% | 6.6% | 13.4% | 46.9% | 30.8% | 100% |

| Rank/7 | 2 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 2 | |

| Shoalhaven | 0 | 272 | 803 | 2644 | 1220 | 4939 |

| % | 0% | 5.5% | 16.3% | 53.5% | 24.7% | 100% |

| Rank/7 | =6 | 7 | 4 | 3 | 4 | |

| Bega | 35 | 436 | 994 | 3474 | 370 | 5310 |

| % | 0.7% | 8.2% | 18.7% | 65.4% | 7.0% | 100% |

| Rank/7 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 6 | |

| NSW | 12343 | 62812 | 247824 | 275313 | 167239 | 765531 |

| 1.6% | 8.2% | 32.4% | 36.0% | 21.8% | 100% |

| Class / Case | (best) 5 |

4 | 3 | 2 | (worst) 1 |

Total km |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Byron (km2) | 169 | 1127 | 254 | 482 | 91 | 2123 |

| % | 8.0% | 53.1% | 12.0% | 22.7% | 4.3% | 100% |

| Rank/7 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 6 | 6 | |

| Coffs | 0 | 840 | 1108 | 1386 | 640 | 3974 |

| % | 0% | 21.1% | 27.9% | 34.9% | 16.1% | 100% |

| Rank/7 | =6 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 5 | |

| P. Macq | 25 | 622 | 1270 | 398 | 1113 | 3428 |

| % | 0.7% | 18.1% | 37.1% | 11.6% | 32.5% | 100% |

| Rank/7 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 7 | 1 | |

| L.Hunter | 61 | 283 | 433 | 2273 | 810 | 3859 |

| % | 1.6% | 7.3% | 11.2% | 58.9% | 21.0% | 100% |

| Rank/7 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 4 | |

| Sydney | 118 | 333 | 679 | 2376 | 1562 | 5068 |

| % | 2.3% | 6.6% | 13.4% | 46.9% | 30.8% | 100% |

| Rank/7 | 2 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 2 | |

| Shoalhaven | 0 | 336 | 862 | 2282 | 1174 | 4654 |

| % | 0% | 7.2% | 18.5% | 49.0% | 25.2% | 100% |

| Rank/7 | =6 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 3 | |

| Bega | 16 | 186 | 457 | 5370 | 0 | 6029 |

| % | 0.3% | 3.1% | 7.6% | 89.1% | 0% | 100% |

| Rank/7 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 1 | 7 | |

| NSW | 12343 | 62812 | 247824 | 275313 | 167239 | 765531 |

| 1.6% | 8.2% | 32.4% | 36.0% | 21.8% | 100% |

| BSAL | Method 1 | Method 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BSAL km2 | Boundary area km2 | % of area | BSAL km2 | Boundary area km2 | % of area | |

| Byron | 975 | 5293 | 18.4 % | 550 | 2346 | 23.5 % |

| Coffs | 245 | 5297 | 4.6 % | 279 | 4264 | 6.5 % |

| Port Mac | 294 | 5275 | 5.6 % | 176 | 3681 | 4.8 % |

| LH | 398 | 5012 | 7.9 % | 289 | 5794 | 5.0 % |

| SYD | 103 | 5340 | 1.9 % | 103 | 5340 | 1.9 % |

| Nowra | 163 | 4974 | 3.3 % | 201 | 4947 | 4.1 % |

| Bega | 35 | 5318 | 0.7 % | 47 | 6294 | 0.8 % |

| NSW | 30945 | 810213 | 3.8 % | |||

| SSAL | Method 1 | Method 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSAL km2 | Boundary area km2 | % of area | SSAL km2 | Boundary area km2 | % of area | |

| Byron | 2212 | 5293 | 41.8 % | 1091 | 2346 | 46.5 |

| Coffs | 414 | 5297 | 7.8 % | 419 | 4264 | 9.8 |

| Port Mac | 524 | 5275 | 9.9 % | 351 | 3681 | 9.5 |

| LH | 390 | 5012 | 7.8 % | 312 | 5794 | 5.4 |

| SYD | 246 | 5340 | 4.6 % | 246 | 5340 | 4.6 |

| Nowra | 199 | 4974 | 4.0 % | 242 | 4947 | 4.9 |

| Bega | 96 | 5318 | 1.8 % | 68 | 6294 | 1.1 |

| NSW | 94914 | 810213 | 11.7 % | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).