Submitted:

15 February 2025

Posted:

18 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Balancing regional disparities in non-grainization at the prefecture level is vital for stable grain production and sustainable urbanization. This study employs geospatial analysis to examine the spatiotemporal patterns and driver factors of non-grainization in Jiangsu Province from 2001 to 2020. By integrating geospatial data from 77 county-level units and employing spatial autocorrelation analysis, multiple linear regression, and Mixed Geographically Weighted Regression (MGWR), this study reveals the spatial heterogeneity and key driving factors of non-grainization. The results indicate that despite cyclical fluctuations in the provincial non-grainization rate, significant regional differences persist. High–high clusters are evident in economically developed southern and coastal areas, while low–low clusters are observed in less developed northern regions, indicating strong spatial dependence. Furthermore, the analysis reveals that rural residents' per capita disposable income and total agricultural output contribute to the process of non-grainization, emphasizing the impact of economic development on land use decisions. These findings highlight the importance of geoinformation tools in managing regional disparities. Integrating spatial and socioeconomic analysis offers practical insights for policymakers to develop targeted strategies that balance food security with agricultural diversification. This study provides valuable insights for policymakers seeking to optimize land-use planning in rapidly urbanizing agricultural regions.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Resources

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Measurement of the "Non-grainization" Level

2.3.2. Spatial Autocorrelation

2.3.3. Multiple Linear Regression and Mixed Geographically Weighted Regression

3. Results

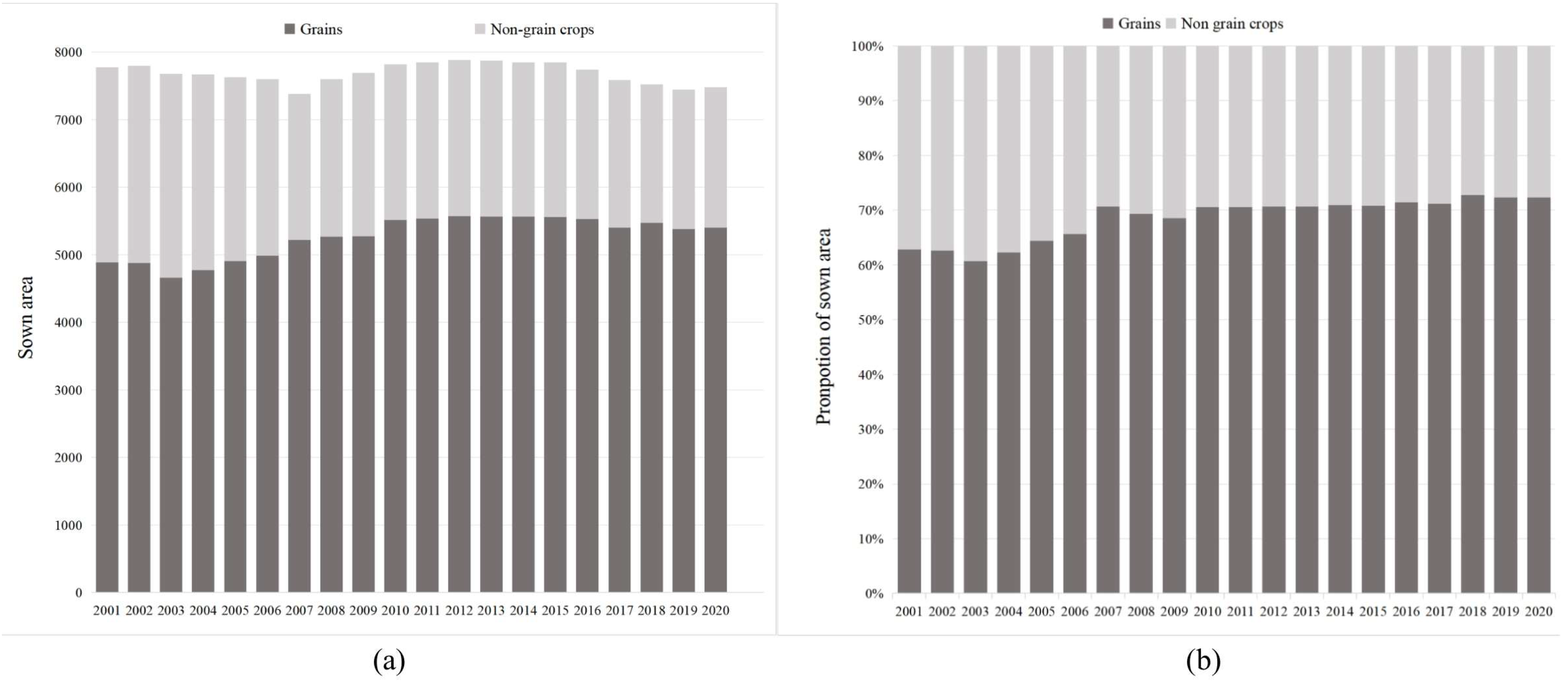

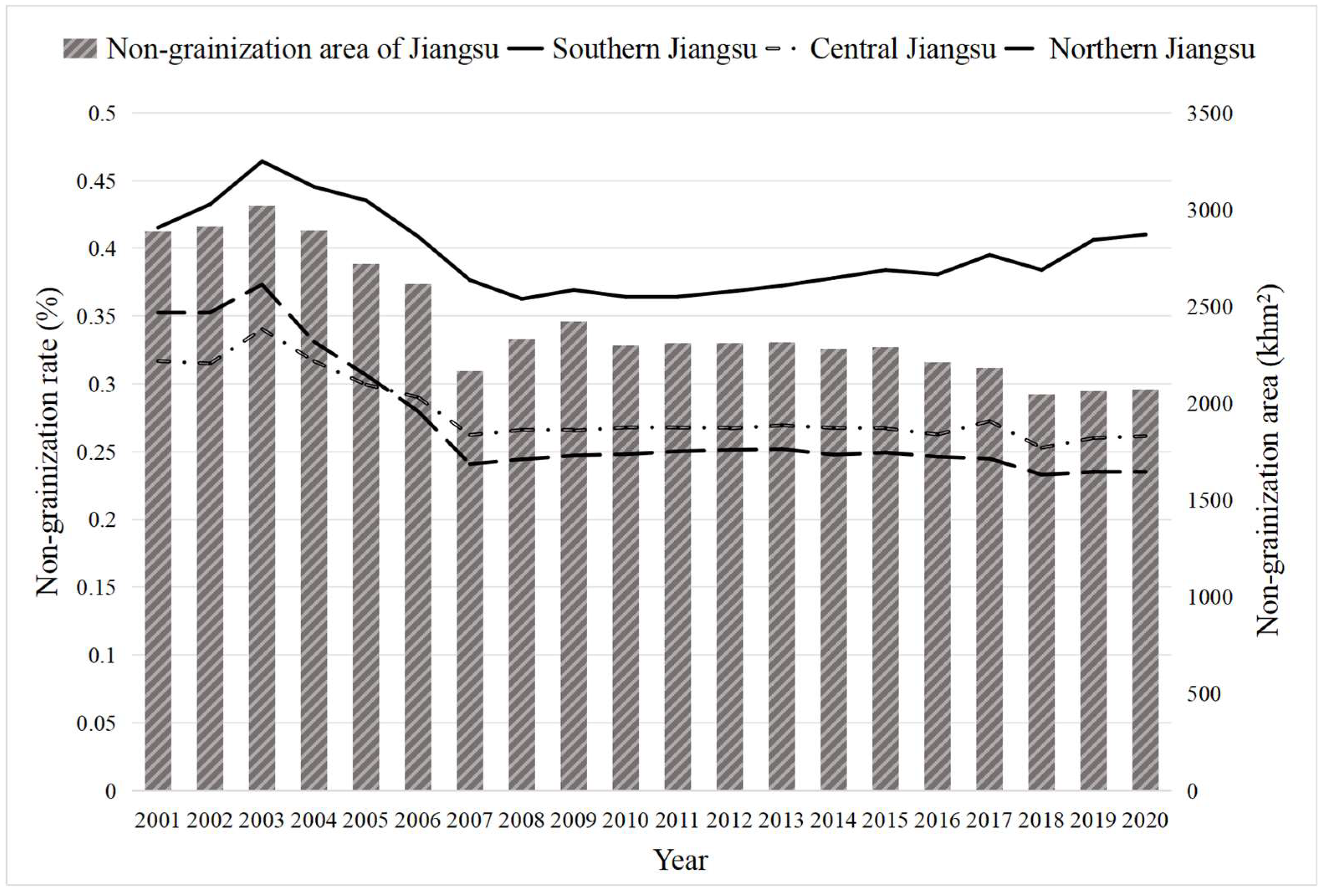

3.1. Temporal Characteristics of Non-grainization in Jiangsu Province's Cultivated Land

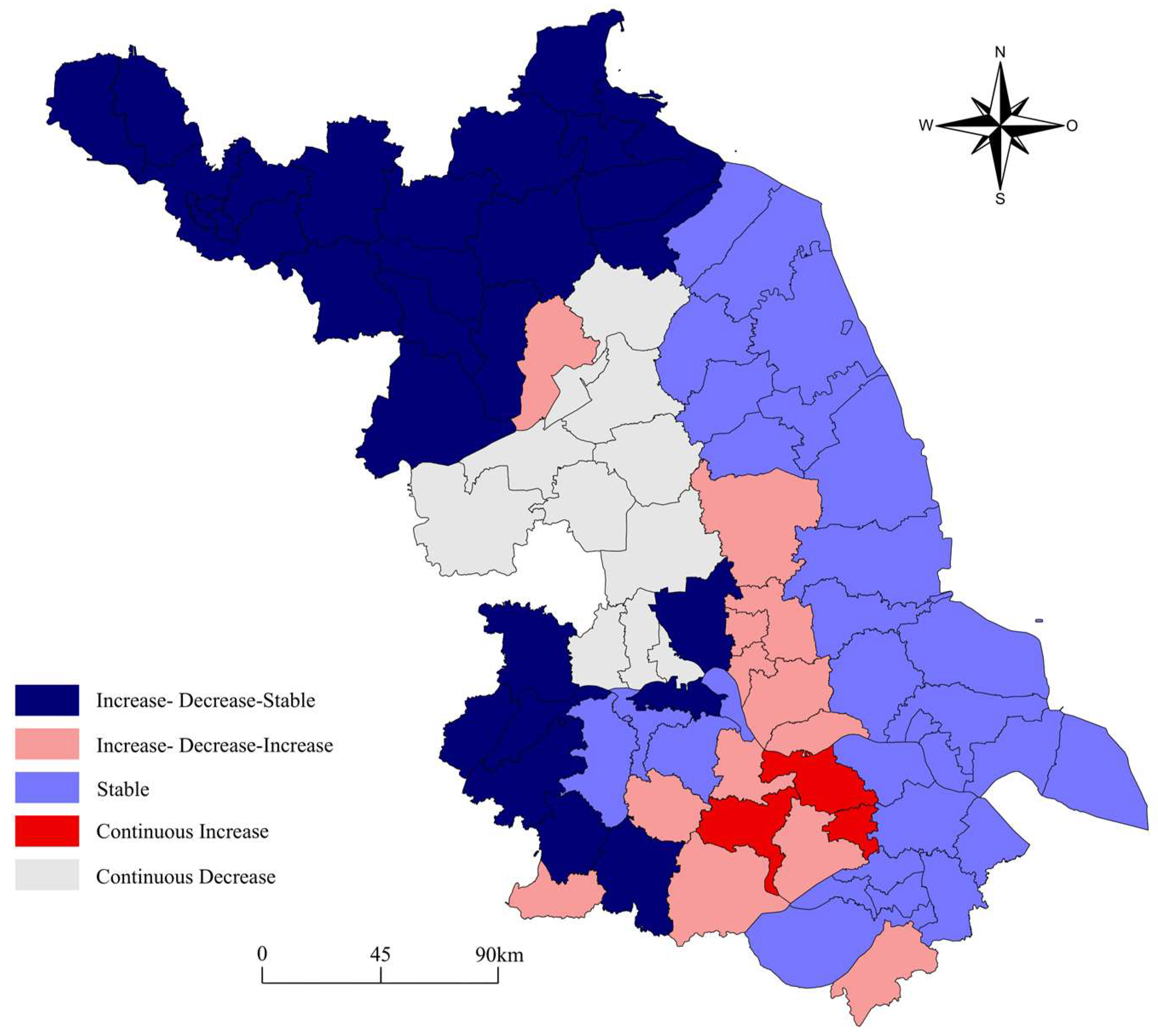

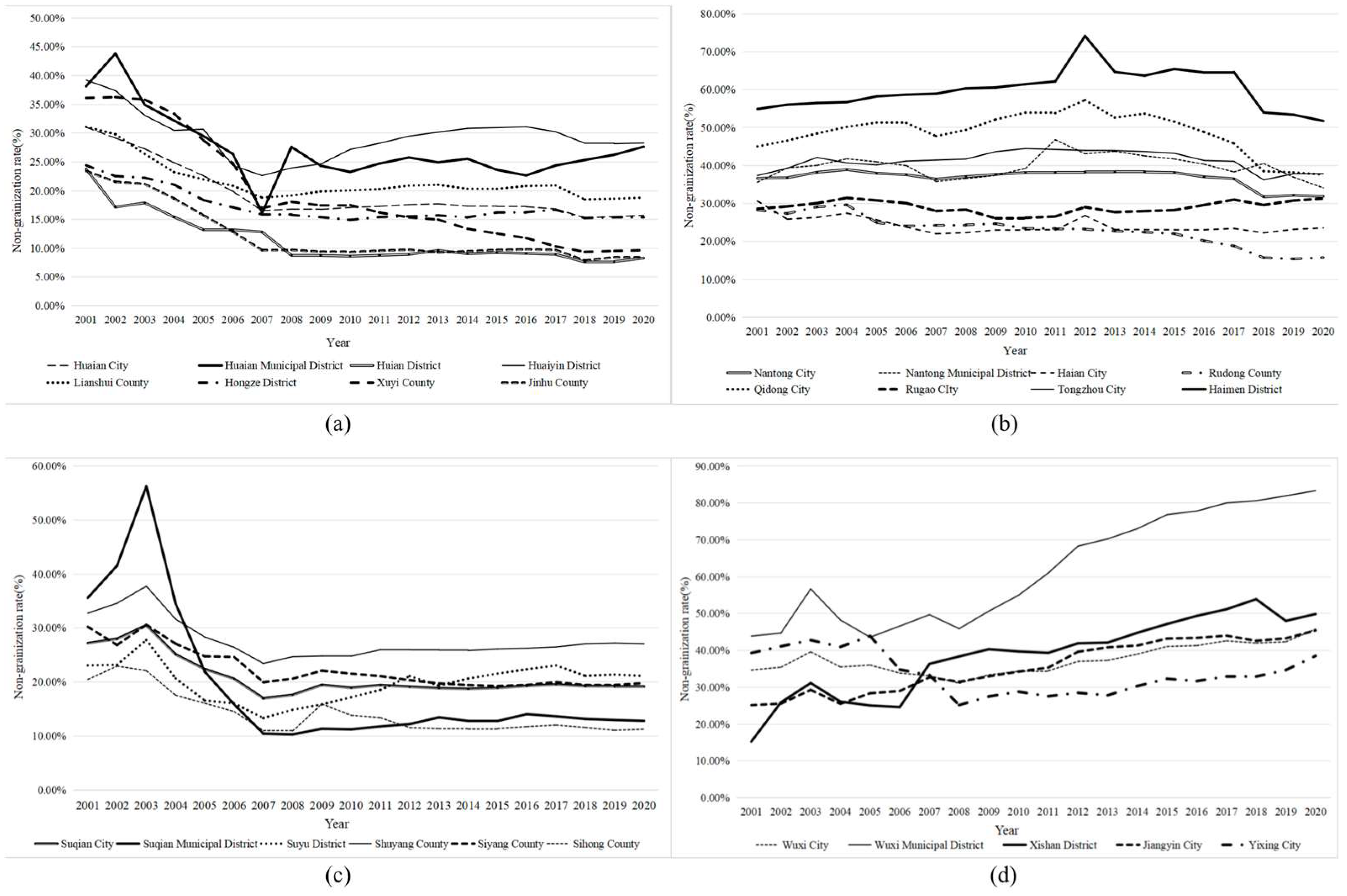

- Increase–Decrease–Increase: Counties such as Wuxi and Taizhou had a pattern of rising, falling, and then rising non-grainization rates. For example, Wuxi’s non-grainization rate increased significantly to 56.69% between 2001 and 2003, then gradually decreased from 2003 to 2005, and finally increased rapidly to 83.35% by 2020 (Figure 5a).

- Continuous Increase: This pattern was mainly concentrated in southern Jiangsu, including Xishan District in Wuxi, Jiangyin, and Wujin District in Changzhou. Jiangyin’s non-grainization rate increased by 20.2% from 2001 to 2020 (Figure 5a).

- Stable: Some counties, such as Hai’an, Dongtai, and Danyang, experienced relatively stable non-grainization rates from 2001 to 2020 (Figure 5b).

- Increase–Decrease–Stable: Some counties, such as Suqian, Zhenjiang, and Lianyungang, had a rapid rise in non-grainization rates between 2001 and 2003, reaching a peak of 56.29% followed by a decline to 10.29% by 2008, with little variation thereafter (Figure 5c).

- Continuous Decrease: Some counties, such as Xuyi, Lianshui, and Hongze in Huai'an, showed a continuous decline in non-grainization rates, with Xuyi’s rate falling by 26.46% from 2001 to 2020 (Figure 5d).

3.2. Spatial Characteristics of Non-grainization in Jiangsu Province

3.3. Analysis of the Factors Influencing the Non-grainization of Cultivated Land in Jiangsu Province

4. Discussion

4.1. Analysis of the Factors Affecting the Non-grainization Rate of Cultivated Land in Jiangsu Province and Regional Differences

4.2. Potential Impact of the Non-grainization of Cultivated Land on China's Food Security

4.3. Policy Implications

4.3.1. Cross-regional Allocation of Food and Cash Crops, and the Establishment of a Provincial Compensation Mechanism

4.3.2. Ensure Basic Reserves of Grain Fields, Strictly Control the Increase in the Non-grainization Rate, and Avoid a "One-size-fits-all" Approach

4.3.3. Accelerate Land Transfer and Promote the Large-scale Cultivation of Arable Land

4.3.4. Accelerate Land Transfer and Promote the Large-scale Cultivation of Arable Land

- Increase–decrease–increase: Mainly concentrated in southern Jiangsu, with some areas in central Jiangsu. The non-grainization rate during the increase phase is generally much higher than the provincial average. Vigilance is required to curb the further spread of non-grainization. Measures such as the grain security responsibility system should be implemented to protect grain cultivation areas and strengthen the surveillance of "grain fields" converted to "non-grain fields" to ensure food security. A high standard of farmland construction should be promoted to maintain the cultivation area and improve farmland management. This would prevent farmers from abandoning grain for economic benefits.

- Continuous increase: Primarily in southern Jiangsu, where the proportion of grain-sown areas is generally below 60%. High-quality grain crop varieties should be promoted, with priority given to arable land use. In this region, high-quality arable land should be used for grain production.

- Increase–decrease–stable: Mainly occurs in municipal districts, which are the core components of urban areas and the centers of regional economic development. While developing tertiary industry, modern agriculture should also be vigorously developed to establish concentrated and contiguous high-yield grain production areas. This would ensure an effective supply of the major agricultural products, continuous income growth for farmers, and sustainable agricultural development.

- Stable: Classified treatment and scientific planning are required in these regions. For areas with non-grainization rates below the provincial average (e.g., Suqian and Lianyungang municipal districts), which have a strong foundation in grain production and a significant impact on food security, stable production rates and supply should be maintained. The production capacity of important agricultural products should be gradually improved. For areas with non-grainization rates above the provincial average, existing farmland planning should be adjusted, and the Party and government should take joint responsibility for food security.

- Continuous decrease: Most districts and counties in Huai'an displayed an overall decreasing trend. In 2022, 10.4% of Jiangsu's arable land produced 12.9% of its grain. Therefore, all regions must resolutely reduce the unauthorized use of arable land, implement various strategies to enhance food security, and consistently enhance mechanisms for high-quality farmland construction.

5. Conclusions

References

- Prosekov; Alexander, Y.; Ivanova; etc. Food security: The challenge of the present. Geoforum 2018, 91, 73-77. [CrossRef]

- Beddington, J.R.; Crute, I.R.; Godfray, H.C.J. Food security: the challenge of feeding 9 billion people. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2010, 327, 812-818. [CrossRef]

- Zhai, J.; Pu, L.; Lu, Y.; etc. Is the boom in staple crop production attributed to expanded cropland or improved yield? A comparative analysis between China and India. Sci Total Environ 2024, 933, 173151. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, K.; Zhai, Y.; Wang, L.; etc. Spatio-Temporal Differentiation of Non-Grain Production of Cropland and Its Influencing Factors: Evidence from the Yangtze River Economic Belt, China. Sustainability (2071-1050) 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- He, T.T.; Jiang, S.Q.; Xiao, W.; etc. A non-grain production on cropland spatiotemporal change detection method based on Landsat time-series data. Land Degrad Dev 2024, 35, 3031-3047. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Yang, W.; Kang, D.; etc. Spatial-temporal characteristics and policy implication for non-grain production of cultivated land in Guanzhong Region. Land Use Policy 2023, 125. [CrossRef]

- Bhullar, A.; Nadeem, K.; Ali, R.A. Simultaneous multi-crop land suitability prediction from remote sensing data using semi-supervised learning. Sci Rep-Uk 2023, 13. [CrossRef]

- Hao, Q.; Zhang, T.; Cheng, X.; etc. GIS-based non-grain cultivated land susceptibility prediction using data mining methods. Sci Rep-Uk 2024, 14. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Yuan, C.; Wei, W.X. Decoupling relationship between the non-grain production and intensification of cultivated land in China based on Tapio decoupling model. J Clean Prod 2023, 424, 138800-138801. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.Y.; Duan, J.J.; Li, S.L.; etc. Phenomenon of Non-Grain Production of Cultivated Land Has Become Increasingly Prominent over the Last 20 Years: Evidence from Guanzhong Plain, China. Agriculture-Basel 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Xie, S.; etc. Research on the Influence Mechanism of Land Tenure Security on Farmers’ Cultivated Land Non-Grain Behavior. In Agriculture, 2022; Vol. 12. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.C.; Zhang, Y.N.; Zhu, Y.L.; etc. The battle of crops: unveiling the shift from grain to non-grain use of farmland in China? Int J Agr Sustain 2023, 21. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.F.; Zhao, B.C.; Huang, A.; etc. Characteristics and Driving Forces of Non-Grain Production of Cultivated Land from the Perspective of Food Security. Sustainability-Basel 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.L.; Ding, Y. Research on Early Warning of Food Security Using a System Dynamics Model: Evidence from Jiangsu Province in China. J Food Sci 2015, 80, R1-R9. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Liu, Q.L.; Deng, M. Spatial hotspot detection in the presence of global spatial autocorrelation. Int J Geogr Inf Sci 2023, 37, 1787-1817. [CrossRef]

- Hughey, S.M.; Kaczynski, A.T.; Porter, D.E.; etc. Spatial clustering patterns of child weight status in a southeastern US county. Applied Geography (Sevenoaks, England) 2018, 99, 12-21. [CrossRef]

- Bashir, A.; Shehzad, M.A.; Hussain, I.; etc. Reservoir Inflow Prediction by Ensembling Wavelet and Bootstrap Techniques to Multiple Linear Regression Model. Water Resour Manag 2019, 33, 5121-5136. [CrossRef]

- Kamarianakis, Y.; Feidas, H.; Kokolatos, G.; etc. Evaluating remotely sensed rainfall estimates using nonlinear mixed models and geographically weighted regression. Environ Modell Softw 2008, 23, 1438-1447. [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Qian, K.; Lin, L.; etc. Identifying the driving forces of non-grain production expansion in rural China and its implications for policies on cultivated land protection. Land Use Policy 2020, 92, 104435. [CrossRef]

- Song, J.R.; Hu, S.G.; Frazier, A.E.; etc. Will industrial structure changes promote or reduce non-grain production? Evidence from the Yangtze River Economic Belt. J Clean Prod 2024, 466. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.L.; Chen, H.; Zeng, T.; etc. Risk preference and rural livelihood transitions in the hilly and mountainous region of southern China: a case study in Ruijin City. Sci Rep-Uk 2024, 14. [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, L.; López-Feldman, A.; Taylor, J.E. Is off-farm income reforming the farm? Evidence from Mexico. Agr Econ-Blackwell 2009, 40, 125-138. [CrossRef]

- Oduol, J.; Tsuji, M. The effect of farm size on agricultural intensification and resource allocation decisions: Evidence from smallholder farms in Embu District, Kenya. J Fac Agr Kyushu U 2005, 50, 727-742. [CrossRef]

- Ritzema, R.S.; Frelat, R.; Douxchamps, S.; etc. Is production intensification likely to make farm households food-adequate? A simple food availability analysis across smallholder farming systems from East and West Africa. Food Secur 2017, 9, 115-131. [CrossRef]

- Zou, B.L.; Chen, Y.D.; Mishra, A.K.; etc. Agricultural mechanization and the performance of the local Chinese economy. Food Policy 2024, 125. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.X.; Xiao, D.Y.; Yin, M.M. Spatiotemporal Patterns and Driving Factors of Non-Grain Cultivated Land in China's Three Main Functional Grain Areas. Sustainability-Basel 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Li, C.; Wang, K.; etc. Quantifying the spatiotemporal dynamics and multi-aspect performance of non-grain production during 2000–2015 at a fine scale. Ecol Indic 2019, 101, 410-419. [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Yuanyuan, C.; Junna, L.; etc. Spatial Differentiation of Non-Grain Production on Cultivated Land and Its Driving Factors in Coastal China. Sustainability-Basel 2021, 13, 13064. [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Guo, J.; Yi, J.; et al. Analysis on the Evolution of Spatiotemporal Pattern and Driving Factors of Non-grain Cultivated land in Jiangsu Province from 1996 to 2020. Resources and Environment in the Yangtze Basin 2024, 33, 436–447.

- Liu, H.; Chen, S. Empirical analysis of factors influencing farmers’ willingness to participate in small-scale farmland water conservancy construction—Based on a survey of 475 farmers in major grain-producing areas of Hunan Province. China Rural Survey 2012, 02, 54–66.

- Xia, L. Study on the Relationship between Non-Grain Production of Cultivated Land and Rural Household Income under the background of the Rural Revitalization Strategy: Based on on-site Research and Analysis in Xuanwei City, Yunnan Province. Master’s Thesis, Yunnan University of Finance and Economics, China, 2023.6.5.

- Liu, K.; Li, Y.; Wu, Q.; etc. Driving force analysis of land use change in the developed area based on Probit regression model: A case study of Nanjing City, China. Ying Yong Sheng Tai Xue Bao = the Journal of Applied Ecology 2015, 26, 2131-2138.

- Diana, M.; Zulkepli, N.A.; Ern, L.K.; etc. Factors affecting behavioral intentions of farmers in Southeast Asia to technology adoption: A systematic review analysis. J Environ Manage 2024, 367. [CrossRef]

- Zang, H. Research on Factors Affecting Farmers' Non-grain Planting Behavior and Scale in the Process of Land Rent-al——Based on Survey Data of Farmers in Xiayi County, Henan Province. Master’s Thesis, Southwestern University of Fi-nance and Economics, China, 2020.5.18.

- Dai, C.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J. Revealing the process and mechanism of non-grain production of cropland in rapidly urbanized deqing County of China. J Environ Manage 2025, 374, 123948. [CrossRef]

- Lou, S. What determines the investment intention of Chinese farmers in green grain production? Environ Dev Sustain 2024, 26, 11217-11242. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, C.J.; Zhao, X.H. Impacts of chemical fertilizer reduction on grain yield: A case study of China. Plos One 2024, 19. [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; et al. Spatial-temporal variation and driving types of non-grain cultivated land in hilly and mountainous areas of Chongqing. Journal of Agricultural Resources and Environment 2024, 41, 15–26.

- Zheng, T.; Zhao, G.Q.; Chu, S.W. A Study on the Impact of External Shocks on the Resilience of China's Grain Supply Chain. Sustainability-Basel 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

| Driving factor | Variable description | Unit | Predicted relationship |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social development | |||

| Non-agricultural employment ratio (X1) | Non-agricultural employed labor in rural areas/Total employed labor in rural areas | % | + |

| Urbanization rate (X2) | Urban population as a proportion of the total population | % | + |

| Per capita cultivated land area (X3) | Total cultivated land area in the county/Total rural population | Khm2 | ± |

| Villager group (X4) | Number of villager groups in the county during a specific time period | Number of groups | - |

| Economic factors | |||

| Total agricultural output value (X5) | Total agricultural output value, forestry, animal husbandry, and fisheries | Million CNY | + |

| Per capita disposable income of rural residents (X6) | Income obtained by rural residents in the county after initial distribution and redistribution | CNY per capita | ± |

| Proportion of non-agricultural income (X7) | Non-agricultural income/Disposable income of rural residents | % | + |

| Production conditions | |||

| Total agricultural machinery power (X8) | Total power of the machinery used in agriculture, forestry, animal husbandry, and fisheries in the county | MW | - |

| Rural electricity consumption (X9) | Total electricity consumption in rural areas of the county during a specific time period | MWh | ± |

| Agricultural fertilizer usage (X10) | Total amount of fertilizer used in agricultural production in the county during a specific time period | Tons | + |

| Pesticide usage (X11) | Total amount of pesticides used in agricultural production in the county during a specific time period | Tons | - |

| Dependent variable | Non-grainization rate of cultivated land | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Independent variable | MLR | MGWR | ||||

| Coefficient | T value | VIF | Mean | Minimum | Maximum | ||

| 2001 | Constant | 31.6 | 0.0 | -0.2 | 0.4 | ||

| X1 | -0.5* | -2.1 | 5.5 | -0.4 | -0.6 | -0.1 | |

| X2 | 0.4** | 3.2 | 2.0 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.7 | |

| X3 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 1.6 | 0.2 | -0.0 | 0.4 | |

| X4 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 3.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | |

| X5 | -0.2 | -1.2 | 3.9 | 0.0 | -0.1 | 0.1 | |

| X6 | 1.1** | 4.7 | 5.6 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 1.0 | |

| X7 | -0.1 | -0.4 | 6.9 | -0.2 | -0.3 | -0.2 | |

| X8 | -0.2 | -1.2 | 2.3 | -0.3 | -0.3 | -0.2 | |

| X9 | -0.5** | -2.7 | 4.5 | 0.2 | -0.2 | 0.5 | |

| X10 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 4.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | |

| X11 | 0.3 | 1.6 | 2.8 | 0.0 | -0.0 | 0.2 | |

| Adj.R2 | 0.33 | 0.58 | |||||

| AIC | 182.2 | ||||||

| Function | Gaussian | ||||||

| 2010 | Constant | 23.7 | -0.4 | -0.6 | -0.1 | ||

| X1 | -0.2 | -1.4 | 3.9 | -0.0 | -0.1 | 0.0 | |

| X2 | 0.2 | 1.8 | 2.2 | 0.2 | -0.1 | 0.6 | |

| X3 | -0.1 | -0.7 | 2.1 | 0.0 | -0.0 | 0.1 | |

| X4 | 0.1 | 1.1 | 2.3 | 0.1 | -0.1 | 0.3 | |

| X5 | 0.4 | 2.2 | 4.6 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.5 | |

| X6 | 0.9*** | 4.3 | 6.0 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.7 | |

| X7 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 7.6 | 0.1 | -0.1 | 0.2 | |

| X8 | -0.2 | -1.3 | 3.8 | -0.2 | -0.2 | -0.2 | |

| X9 | -0.5** | -3.3 | 2.9 | -0.5 | -0.6 | -0.4 | |

| X10 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 4.5 | 0.0 | -0.2 | 0.1 | |

| X11 | -0.1 | -0.9 | 1.6 | -0.1 | -0.4 | 0.1 | |

| Adj.R2 | 0.41 | 0.59 | |||||

| AIC | 170.6 | ||||||

| Function | Gaussian | ||||||

| 2020 | Constant | 25.4 | -0.2 | -0.4 | -0.0 | ||

| X1 | -0.0 | -0.1 | 3.2 | -0.1 | -0.1 | -0.0 | |

| X2 | 0.1 | 1.1 | 2.3 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | |

| X3 | -0.3* | -2.3 | 2.3 | -0.2 | -0.2 | -0.1 | |

| X4 | -0.0 | -0.4 | 2.7 | -0.1 | -0.2 | -0.0 | |

| X5 | 0.4 | 2.0 | 6.5 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.5 | |

| X6 | 0.9*** | 4.6 | 5.4 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.7 | |

| X7 | -0.2 | -0.8 | 7.0 | 0.0 | -0.1 | 0.0 | |

| X8 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 7.8 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| X9 | -0.2 | -1.3 | 2.7 | -0.1 | -0.1 | -0.1 | |

| X10 | -0.2 | -1.1 | 4.3 | -0.2 | -0.4 | -0.1 | |

| X11 | -0.2 | -1.1 | 2.8 | -0.2 | -0.3 | -0.1 | |

| Adj.R2 | 0.51 | 0.56 | |||||

| AIC | 170.6 | ||||||

| Function | Gaussian | ||||||

| Dependent variable | Non-grainization area of cultivated land | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Independent variable | MLR | MGWR | ||||

| Coefficient | T value | VIF | Mean | Minimum | Maximum | ||

| 2001 | Constant | 24.2 | -0.1 | -0.1 | 0.1 | ||

| X1 | -0.2 | -1.7 | 5.5 | -0.2 | -0.2 | -0.1 | |

| X2 | 0.1 | 0.9 | 2.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| X3 | 0.1 | 2.0 | 1.6 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.5 | |

| X4 | 0.2 | 1.6 | 3.0 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | |

| X5 | 0.3** | 2.9 | 3.9 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.5 | |

| X6 | 0.4** | 2.7 | 5.6 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | |

| X7 | -0.0 | -0.0 | 6.9 | -0.1 | -0.2 | -0.1 | |

| X8 | -0.1 | -1.4 | 2.3 | -0.2 | -0.2 | -0.2 | |

| X9 | -0.2 | -1.8 | 4.5 | -0.0 | -0.2 | 0.1 | |

| X10 | 0.5*** | 4.3 | 4.3 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.5 | |

| X11 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.8 | -0.1 | -0.2 | 0.1 | |

| Adj.R2 | 0.74 | 0.83 | |||||

| AIC | 105.1 | ||||||

| Function | Gaussian | ||||||

| 2010 | Constant | 17.4 | -0.2 | -0.2 | -0.1 | ||

| X1 | -0.2 | -1.3 | 3.9 | -0.0 | -0.1 | -0.0 | |

| X2 | -0.0 | -0.4 | 2.2 | 0.0 | -0.0 | 0.1 | |

| X3 | 0.2 | 1.9 | 2.1 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.3 | |

| X4 | 0.2 | 2.0 | 2.3 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.3 | |

| X5 | 0.7*** | 5.2 | 4.6 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | |

| X6 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 6.0 | 0.0 | -0.1 | 0.1 | |

| X7 | 0.4* | 2.1 | 7.6 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.5 | |

| X8 | -0.4** | -2.8 | 3.8 | -0.3 | -0.3 | -0.2 | |

| X9 | -0.3* | -2.4 | 2.9 | -0.3 | -0.4 | -0.3 | |

| X10 | 0.5** | 3.4 | 4.5 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.4 | |

| X11 | -0.0 | -0.5 | 1.6 | -0.1 | -0.1 | 0.0 | |

| Adj.R2 | 0.67 | 0.70 | |||||

| AIC | 141.4 | ||||||

| Function | Gaussian | ||||||

| 2020 | Constant | 15.8 | -0.1 | -0.2 | 0.0 | ||

| X1 | -0.0 | -0.3 | 3.2 | -0.0 | -0.1 | -0.0 | |

| X2 | -0.0 | -0.1 | 2.3 | 0.0 | -0.0 | 0.0 | |

| X3 | -0.0 | -0.1 | 2.3 | 0.1 | -0.1 | 0.3 | |

| X4 | -0.0 | -0.1 | 2.7 | -0.1 | -0.3 | 0.1 | |

| X5 | 0.9*** | 4.5 | 6.5 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.9 | |

| X6 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 5.4 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | |

| X7 | 0.2 | 0.9 | 7.0 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.4 | |

| X8 | -0.0 | -0.2 | 7.8 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | |

| X9 | -0.0 | -0.2 | 2.7 | -0.1 | -0.1 | -0.0 | |

| X10 | 0.1 | 0.9 | 4.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| X11 | -0.0 | -0.2 | 2.8 | -0.1 | -0.1 | -0.1 | |

| Adj.R2 | 0.56 | 0.63 | |||||

| AIC | 152.5 | ||||||

| Function | Gaussian | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).