Submitted:

14 February 2025

Posted:

18 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

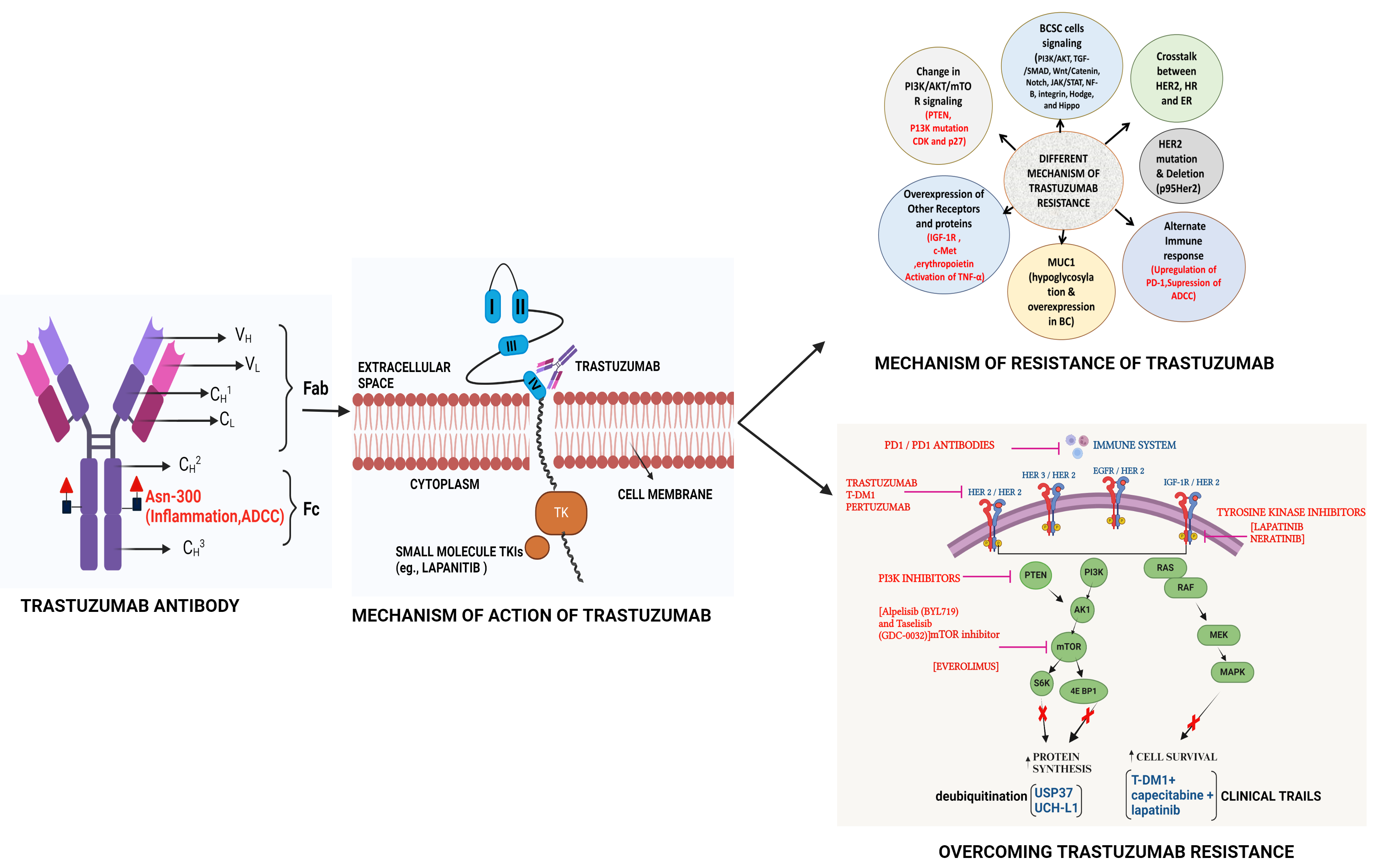

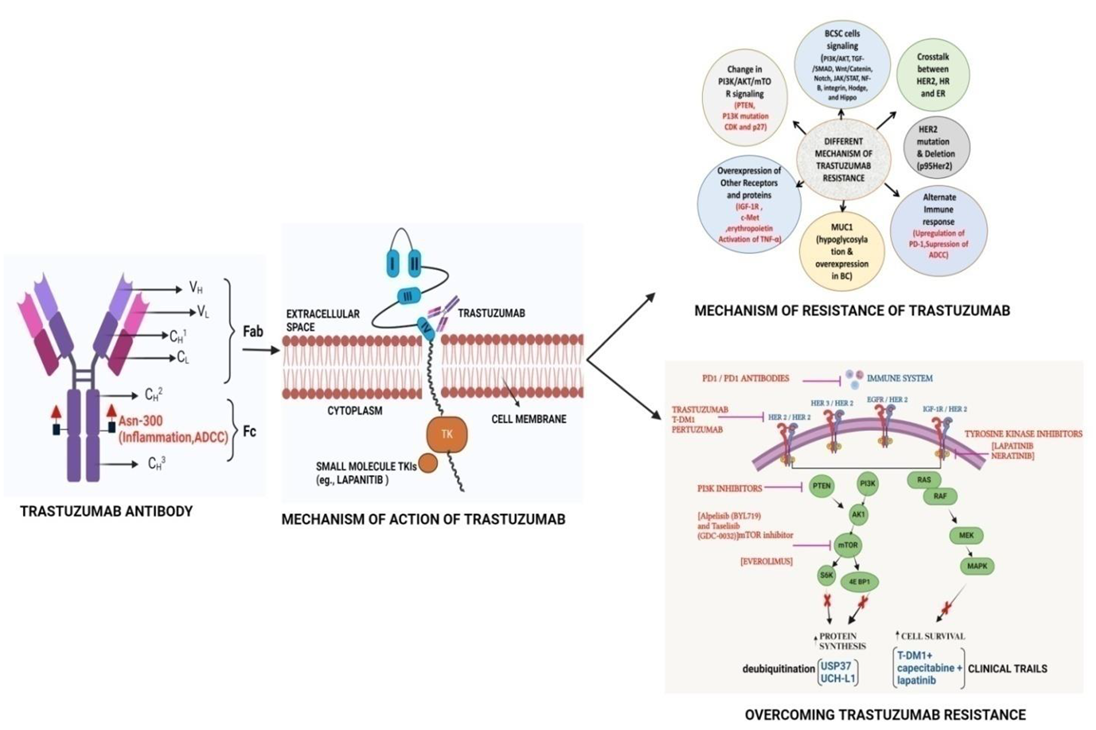

| Graphical Abstract |

|

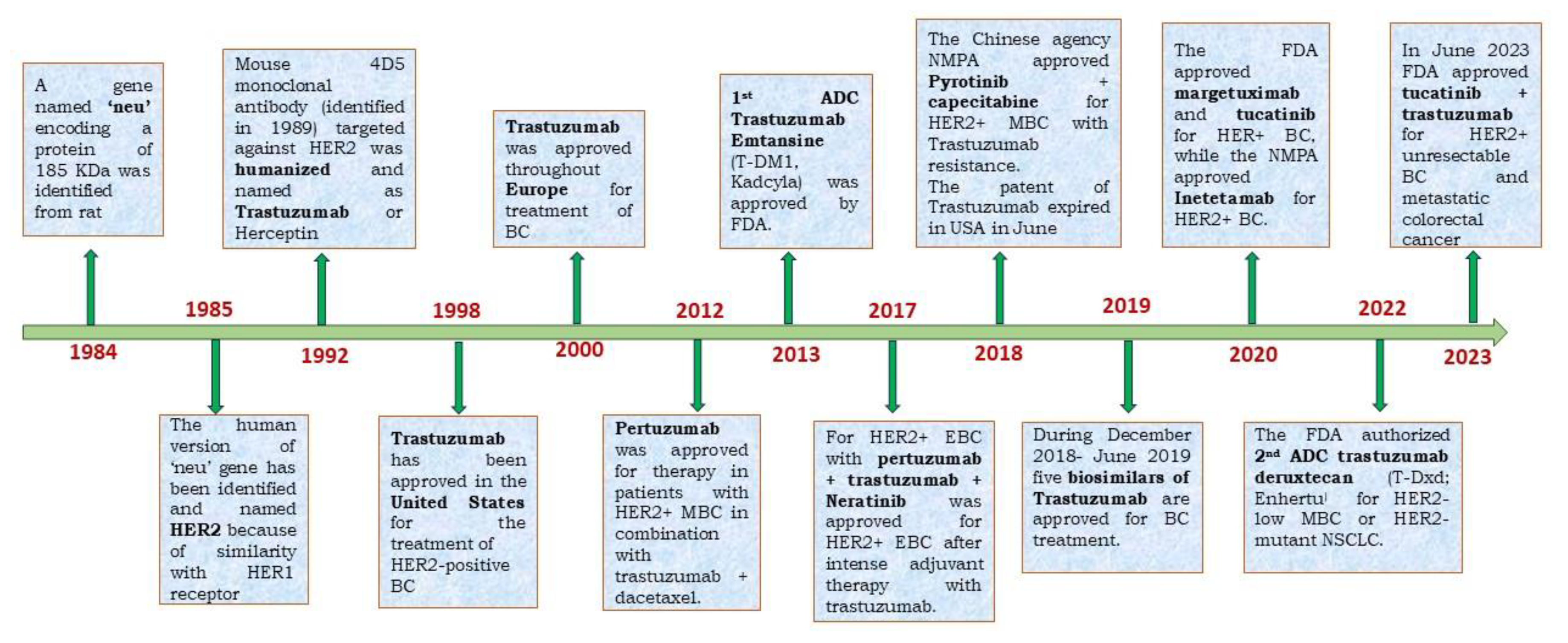

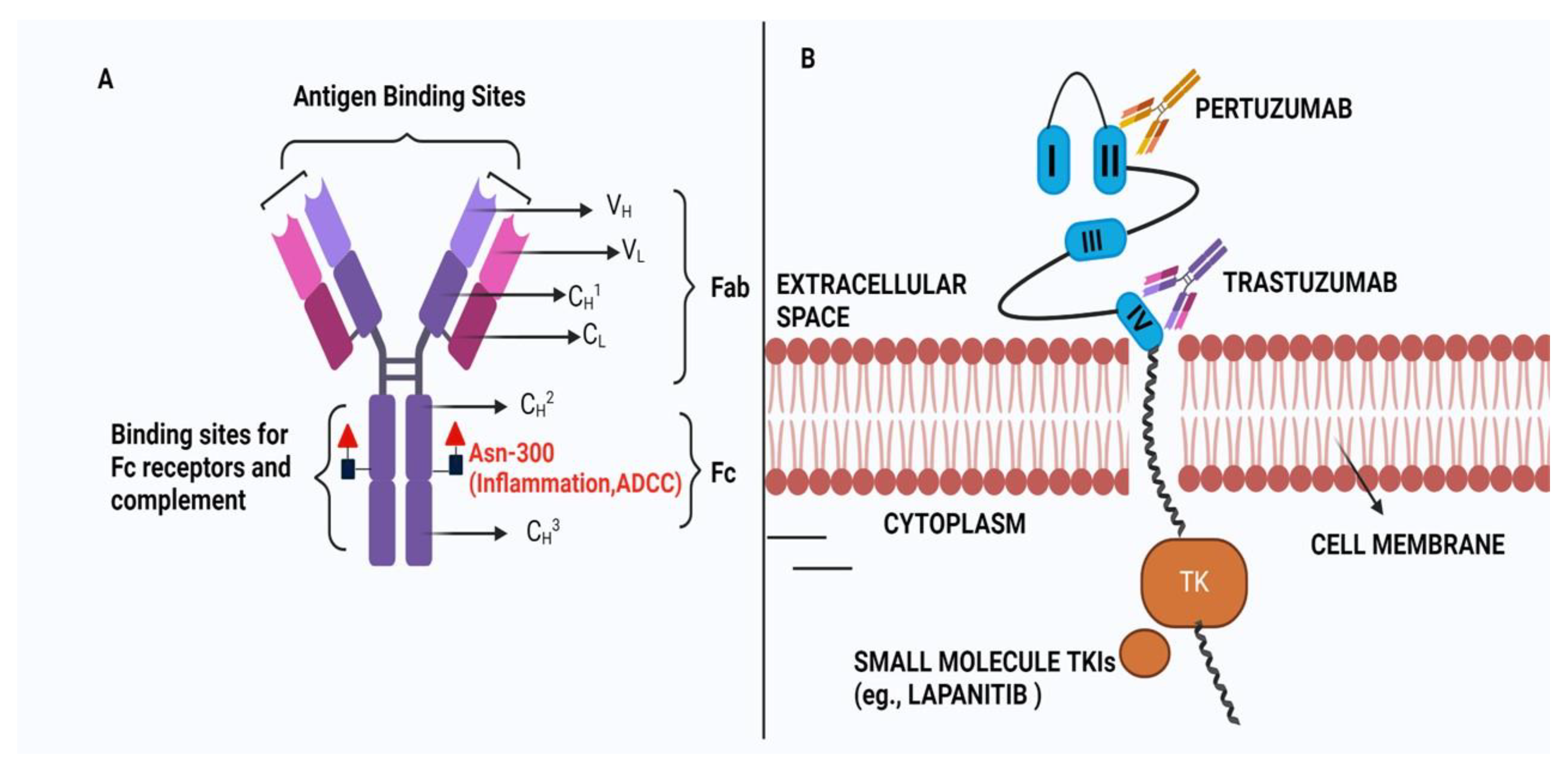

1. Introduction

2. Different Mechanisms of TR

2.1. HER2 Mutations

2.2. Mechanism of TR Through Crosstalk Between HER2 and Estrogen Receptors

2.3. HER2/ER Crosstalk in Acquired Endocrine Resistance Models

2.4. Failure to Trigger ADCC

2.5. Changes in HER2 Downstream Signaling Pathways

2.5.1. Loss of PTEN Expression /Function

2.5.2. P13K Mutation or Increased Activity

2.5.3. Cyclin Dependent Kinases and p27

2.6. Overxpression of Other Receptors and Proteins in Resistance

2.6.1. Increased Expression of IGF-1R

2.6.2. C-Met Coexpression

2.6.3. Over Expression of Erythropoietin

2.6.4. Increased Activity of Rac1

2.6.5. Activation of Tumor Necrosis Factor α

3. Overcoming TR Against HER2-Positive BC

3.1. BC Stem Cell (BCSC)-Specific Therapeutic Approaches forTR

3.1.1. AKT/PI3K Signaling and TGF-β Signalling

3.1.2. Wnt/β-Catenin and Notch Signaling

3.1.3. JAK/STAT, NF-κB, Integrin and Hodge Signalling Pathways

3.1.4. Cytokines and Immunomodulators in BCSC Signaling

3.1.5. Role of Tumor Micro-Environment and Its Modifications

3.1.6. Noncoding RNAs as Target

4. MUC1 is a Possible Target to Overcome TR

4.1. Strategies for Mucin1 Targeting to Overcome TR

4.2. MUC1-Based Therapy Using Mab, Vaccines and CAR T Cells

4.3. Other MUC1-Based Therapy

5. Overcoming Trastuzumab or HER2-Mediated Therapy via the PI3K/Akt/mTOR Pathway

6. Patents Related to BC Therapy and Associated Trastuzumab Resistanc

| Patent Application No and publication year | .Major claims | Molecular mechanism | Reference No. |

|---|---|---|---|

| CN113308542, 27.08.2021 | 1. A Trastuzumab-resistant cell BT474 HR is generated where protein NDUFA 4L2 is over-expressed significantly among 453 studied genes. 2. NDUFA 4L2 can be new target for studying TR |

In herceptin drug-resistant BT474 HR cells, the expression of a protein, NDUFA 4L2, is significantly increased, and is mainly located in mitochondria of cells. The protein NDUFA 4L2 is identified as a new drug target in HER2+ BC cells. | [206] |

| CN112870193, 01.06.2021 |

1. A new composition for treating HER2-positive BC, composed of melatonin and a Tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) lapatinib or neratinib 2. Both melatonin and Melatonin + TKI reduces the expression of HER2 receptor in sensitive and resistant cells |

Melatonin synergizes the effect of small molecule TKIs in reducing the expression level of HER2 receptor in different HER2 positive and TR BC cells. | [216] |

| CN112316146, 05.02.2021 |

1. The expression of Ubiquitin carboxyl terminal hydrolase-L1 (UCH-L1) through a plasmid based expression in HER2 positive BC cells decreases the expression of HER2. 2. Co treatment of UCH-L1 plasmid + lapatinib kills the BC cells significantly by reducing the HER2 receptor expression |

The expression of UCH-L1, which is a deubiquitinase changes the ubiquitination level of HER2 protein and make them more degradation prone thereby reducing the HER2 protein level in UCH-L1 over-expressing BC cells. | [214] |

| CN115029435 09.09.2022 |

1. UGT1A7 expression can reverse the HER -2 positive BC cells TR 2. UGT1A7 expression is drastically down-regulated in the BT474 resistant cell. |

UGT1A7 expression is controlled via mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress after trastuzumab treatment | [207] |

| CN114736966 12.07.2022 |

1. Using CRISPR/Cas9 library it was claimed that inhibition of FGFR4 (fibroblast growth factor receptor 4) enhances the sensitivity of BC in HER2+ therapy 2. Synergistic action of anti-HER2 and anti-FGFR4 antibody in HER2+ BC therapy was shown |

RNA m6A hypomethylation in BC cells upregulates FGFR4, which phosphorylates GSK-3β. It stimulate a beta-catenin/TCF4 signal to drive the drug resistance to HER2 therapy. | [208] |

| CN113640518 12.11.2021 | 1. USP37, a new protein, was found to be involved in the progression of BC. 2. Combination of USP37+ cisplatin or radiation treatments will improve the efficacy of treatment for BC patients |

The deubiquitinating enzyme USP37 kills BC more than cisplatin does because the cells become more degradation prone after USP37 expression | [210] |

7. Clinical Trials Targeting HER2+ BC and Associated TR

| Sl. No. |

Drugs and Phase Trial | Target | Study design and Outcomes |

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Margetuximab and Phase II | Margetuximab – a chimeric Mab in Phase 2 Study in Individuals with Relapsed or Refractory advanced Breast tumors | 25 participants. 1. Margentuximab is well tolerated. 2. Complete response disappearing of all target lesion within ≥ 4 weeks; whereas ≥ 30% reduction in the target lesions from the beginning, observed at ≥ 4 weeks |

NCT01828021 |

| 2. | Margetuximab and Phase III | In the Treatment of HER2+ mBC (SOPHIA), Margetuximab + Chemotherapy vs. Trastuzumab + Chemotherapy | 624 participants. 1. Better PFS than trastuzumab + chemotherapy (5.8 vs. 4.9 months), a potentially comparable ORR of 22% vs. 16%, and a comparable safety profile. 2. Treatment effects were more significant in patients with CD16A genotypes that contained a lower-affinity 158F allele (PFS 6.9 vs. 5.1 months), which is present in about 85% of the general population and is known to reduce clinical response to trastuzumab. |

NCT02492711 |

| 3. | Trastuzumab deruxtecan (DS-8201) and Phase II | For HER2+ BC patients with two groups – T-DM1 resistant and T-DM1 tolerant | 253 participants. 1. DS-8201 showed durable antitumor activity in a pretreated patient population with HER2-positive MBC. 2. In addition to nausea and myelosuppression, interstitial lung disease was observed in a subgroup of patients which requires attention to pulmonary symptoms. Interstitial lung disease was observed in 13.6% of the patients. |

NCT03248492 |

| 4. | Tucatinib and Phase II | Tucatinib vs. Placebo in the combination with Capecitabine and Trastuzumab in Advanced HER2+ BC Patients (HER2CLIMB) | 612 participants 1. Tucatinib in combination with trastuzumab and capecitabine improved OS (44.9% vs. 26.6% compared to placebo) while reducing the risk of developing new brain lesions. 2. The tucatinib-combination group had a 1-year PFS of 33.1%, compared to 12.3% in the placebo group. 3. A sample of patients with brain metastases showed a 1-year PFS of 24.9% in the tucatinib-combination group compared to 0% in the placebo-combination group. |

NCT02614794 |

| 5. | Tucatinib + T-DM1 and Phase III | Tucatinib vs. Placebo in Combination with Ado-Trastuzumab Emtansine (T-DM1) for Advanced or Metastatic HER2+ Breast carcinoma Patients | 565 participants. 1. Study was done to see if tucatinib with T-DM1 works better than T-DM1 alone. 2. The primary PFS benefit for pre-treated HER2+ mBC patients was 8.2 months, with an ORR of 47% at the highest tolerated dose, where 60% of patients had previously been treated with trastuzumab and had brain metastases. |

NCT03975647 |

| 6. | Pertuzumab and Phase III | Chemotherapy + trastuzumab + pertuzumab vs. chemotherapy + trastuzumab for HER2+ mBC. (CLEOPATRA) |

808 participants. 1. 8-year landmark ORR were 37% in the pertuzumab group and 23% in the other group. 2. The long-term safety and cardiac safety profiles of pertuzumab, trastuzumab, and docetaxel were maintained more compared to other group. |

NCT00567190 |

| 7. | Trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) and Phase III | trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) vs. capecitabine + lapatinib in participants with HER2+ mBC (EMILIA) |

991 Participants. 1. T-DM1 significantly increased both PFS (10 months vs 6 months, and OS (31 months vs 25 months). 2. T-DM1 improved overall survival in patients with previously treated HER2-positive mBC compared to chemotherapy group. |

NCT00829166 |

| 8. | Neratinib + Capecitabine and Phase III |

A Study of Neratinib+ Capecitabine vs. Lapatinib + Capecitabine in Patients With HER2+ mBC who Have Received HER2Directed treatment (NALA) |

621 participants. 1.After a median follow-up period of 30 months, the PFS rose by two months in the neratinib combination arm (8.8 months vs 6.6 months), but there was no statistical difference in OS. 2. In a subgroup study, patients with non-visceral or hormone-negative illness had superior outcomes. 3. Treatment with neratinib for patients with brain metastases resulted in no difference in PFS when compared to the control group. |

NCT01808573 |

8. Conclusion and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Consent for Publication

Availability of Data and Material

Acknowledgement

Competing Interests

Abbreviations

| BC | Breast Cancer |

| BCSC | BC stem cell |

| TR | Trastuzumab Resistance |

| ADC | Antibody drug conjugate |

| ADCC | Antibody directed cellular cytotoxicity |

| HER2 | human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 |

| EGFR | Epidermal growth factor receptor |

| ER | Estrogen receptor |

| PR | Progesterone receptor |

| PD-L1 | Programmed death Ligand 1 |

| PD-1 | programmed death 1 |

| PFS | progression free survival |

| OS | overall survival |

| ORR | overall response rate |

| MUC1 | Mucin 1 |

| PI3K | Phosphatidyl Inositol 3 Kinase |

| mTOR | Mammalian target of rapamycin |

| TME | Tumour Micro Environment |

| TKI | Tyrosine kinase inhibitor |

| TNBC | Triple negative BC |

| IGF-1R | Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 receptor |

| MET | Mesenchymal epithelial transition |

| CAR | Chimeric Antigenic Receptor |

| CEA | Carcinoembryonic Antigen |

| STAT3 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor β |

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSantis, C.E.; Ma, J.; Gaudet, M.M.; Newman, L.A.; Miller, K.D.; Goding Sauer, A.; Jemal, A.; Siegel, R.L. Breast cancer statistics, 2019. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 2019, 69, 438–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AL, S. The neu oncogen: an erb-B-releted gene encoding a 185,000-Mr tumour antigen. Nature 1984, 290, 261–264. [Google Scholar]

- Coussens, L.; Yang-Feng, T.L.; Liao, Y.-C.; Chen, E.; Gray, A.; McGrath, J.; Seeburg, P.H.; Libermann, T.A.; Schlessinger, J.; Francke, U. Tyrosine kinase receptor with extensive homology to EGF receptor shares chromosomal location with neu oncogene. Science 1985, 230, 1132–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drebin, J.A.; Link, V.C.; Weinberg, R.A.; Greene, M.I. Inhibition of tumor growth by a monoclonal antibody reactive with an oncogene-encoded tumor antigen. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1986, 83, 9129–9133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slamon, D.J.; Clark, G.M.; Wong, S.G.; Levin, W.J.; Ullrich, A.; McGuire, W.L. Human breast cancer: correlation of relapse and survival with amplification of the HER-2/neu oncogene. science 1987, 235, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudziak, R.M.; Lewis, G.D.; Winget, M.; Fendly, B.M.; Shepard, H.M.; Ullrich, A. p185 HER2 monoclonal antibody has antiproliferative effects in vitro and sensitizes human breast tumor cells to tumor necrosis factor. Molecular and cellular biology 1989, 9, 1165–1172. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, P.; Presta, L.; Gorman, C.M.; Ridgway, J.; Henner, D.; Wong, W.; Rowland, A.M.; Kotts, C.; Carver, M.E.; Shepard, H.M. Humanization of an anti-p185HER2 antibody for human cancer therapy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1992, 89, 4285–4289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eiermann, W.; Group, I.H.S. Trastuzumab combined with chemotherapy for the treatment of HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer: pivotal trial data. Annals of oncology 2001, 12, S57–S62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marty, M.; Cognetti, F.; Maraninchi, D.; Snyder, R.; Mauriac, L.; Tubiana-Hulin, M.; Chan, S.; Grimes, D.; Antón, A.; Lluch, A. Randomized phase II trial of the efficacy and safety of trastuzumab combined with docetaxel in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–positive metastatic breast cancer administered as first-line treatment: the M77001 study group. Journal of clinical oncology 2005, 23, 4265–4274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, E.; Zorn, J.A.; Huang, Y.; Barros, T.; Kuriyan, J. A structural perspective on the regulation of the epidermal growth factor receptor. Annual review of biochemistry 2015, 84, 739–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, L.N.; You, F.; Schnitt, S.J.; Witkiewicz, A.; Lu, X.; Sgroi, D.; Ryan, P.D.; Come, S.E.; Burstein, H.J.; Lesnikoski, B.-A. Predictors of resistance to preoperative trastuzumab and vinorelbine for HER2-positive early breast cancer. Clinical Cancer Research 2007, 13, 1198–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, A.C.; Somerfield, M.R.; Dowsett, M.; Hammond, M.E.H.; Hayes, D.F.; McShane, L.M.; Saphner, T.J.; Spears, P.A.; Allison, K.H. Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer: ASCO–College of American Pathologists Guideline Update. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2023, 41, 3867–3872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vu, T.; Claret, F.X. Trastuzumab: updated mechanisms of action and resistance in breast cancer. Frontiers in oncology 2012, 2, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, G.K.; Robles, R.; Park, J.W.; Montgomery, P.A.; Daniel, J.; Holmes, W.E.; Lee, J.; Keller, G.A.; Li, W.-L.; Fendly, B.M. A truncated intracellular HER2/neu receptor produced by alternative RNA processing affects growth of human carcinoma cells. Molecular and cellular biology 1993, 13, 2247–2257. [Google Scholar]

- Christianson, T.A.; Doherty, J.K.; Lin, Y.J.; Ramsey, E.E.; Holmes, R.; Keenan, E.J.; Clinton, G.M. NH2-terminally truncated HER-2/neu protein: relationship with shedding of the extracellular domain and with prognostic factors in breast cancer. Cancer research 1998, 58, 5123–5129. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Scaltriti, M.; Rojo, F.; Ocaña, A.; Anido, J.; Guzman, M.; Cortes, J.; Di Cosimo, S.; Matias-Guiu, X.; Ramon y Cajal, S.; Arribas, J. Expression of p95HER2, a truncated form of the HER2 receptor, and response to anti-HER2 therapies in breast cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2007, 99, 628–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagy, P.; Friedländer, E.; Tanner, M.; Kapanen, A.I.; Carraway, K.L.; Isola, J.; Jovin, T.M. Decreased accessibility and lack of activation of ErbB2 in JIMT-1, a herceptin-resistant, MUC4-expressing breast cancer cell line. Cancer research 2005, 65, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercogliano, M.F.; De Martino, M.; Venturutti, L.; Rivas, M.A.; Proietti, C.J.; Inurrigarro, G.; Frahm, I.; Allemand, D.H.; Deza, E.G.; Ares, S. TNFα-induced mucin 4 expression elicits trastuzumab resistance in HER2-positive breast cancer. Clinical Cancer Research 2017, 23, 636–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, A.L.; Lee, S.-C. Mechanisms of resistance to trastuzumab and novel therapeutic strategies in HER2-positive breast cancer. International journal of breast cancer 2012, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fessler, S.P.; Wotkowicz, M.T.; Mahanta, S.K.; Bamdad, C. MUC1* is a determinant of trastuzumab (Herceptin) resistance in breast cancer cells. Breast cancer research and treatment 2009, 118, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, G.; Li, L.; Qiu, Y.; Sun, W.; Ren, T.; Lv, Y.; Liu, M.; Wang, X.; Tao, H.; Zhao, L.; et al. A novel humanized MUC1 antibody-drug conjugate for the treatment of trastuzumab-resistant breast cancer. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2021, 53, 1625–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vivekanandhan, S.; Knutson, K.L. Resistance to trastuzumab. Cancers 2022, 14, 5115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arribas, J.; Baselga, J.; Pedersen, K.; Parra-Palau, J.L. p95HER2 and breast cancer. Cancer research 2011, 71, 1515–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperinde, J.; Jin, X.; Banerjee, J.; Penuel, E.; Saha, A.; Diedrich, G.; Huang, W.; Leitzel, K.; Weidler, J.; Ali, S.M. Quantitation of p95HER2 in paraffin sections by using a p95-specific antibody and correlation with outcome in a cohort of trastuzumab-treated breast cancer patients. Clinical Cancer Research 2010, 16, 4226–4235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price-Schiavi, S.A.; Jepson, S.; Li, P.; Arango, M.; Rudland, P.S.; Yee, L.; Carraway, K.L. Rat Muc4 (sialomucin complex) reduces binding of anti-ErbB2 antibodies to tumor cell surfaces, a potential mechanism for herceptin resistance. International journal of cancer 2002, 99, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carraway, K.L.; Price-Schiavi, S.A.; Komatsu, M.; Jepson, S.; Perez, A.; Carraway, C.A.C. Muc4/sialomucin complex in the mammary gland and breast cancer. Journal of mammary gland biology and neoplasia 2001, 6, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlam, I.; Tarantino, P.; Tolaney, S.M. Overcoming resistance to HER2-directed therapies in breast cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 3996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konecny, G.; Pauletti, G.; Pegram, M.; Untch, M.; Dandekar, S.; Aguilar, Z.; Wilson, C.; Rong, H.-M.; Bauerfeind, I.; Felber, M. Quantitative association between HER-2/neu and steroid hormone receptors in hormone receptor-positive primary breast cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2003, 95, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliano, M.; Trivedi, M.V.; Schiff, R. Bidirectional crosstalk between the estrogen receptor and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 signaling pathways in breast cancer: molecular basis and clinical implications. Breast Care 2013, 8, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munzone, E.; Curigliano, G.; Rocca, A.; Bonizzi, G.; Renne, G.; Goldhirsch, A.; Nolè, F. Reverting estrogen-receptor-negative phenotype in HER-2-overexpressing advanced breast cancer patients exposed to trastuzumab plus chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res 2006, 8, R4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pegram, M.; Jackisch, C.; Johnston, S.R.D. Estrogen/HER2 receptor crosstalk in breast cancer: combination therapies to improve outcomes for patients with hormone receptor-positive/HER2-positive breast cancer. NPJ Breast Cancer 2023, 9, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, S.R.D.; Hegg, R.; Im, S.A.; Park, I.H.; Burdaeva, O.; Kurteva, G.; Press, M.F.; Tjulandin, S.; Iwata, H.; Simon, S.D.; et al. Phase III, Randomized Study of Dual Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 (HER2) Blockade With Lapatinib Plus Trastuzumab in Combination With an Aromatase Inhibitor in Postmenopausal Women With HER2-Positive, Hormone Receptor-Positive Metastatic Breast Cancer: ALTERNATIVE. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2018, 36, 741–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llombart-Cussac, A.; Cortés, J.; Paré, L.; Galván, P.; Bermejo, B.; Martínez, N.; Vidal, M.; Pernas, S.; López, R.; Muñoz, M. HER2-enriched subtype as a predictor of pathological complete response following trastuzumab and lapatinib without chemotherapy in early-stage HER2-positive breast cancer (PAMELA): an open-label, single-group, multicentre, phase 2 trial. The lancet oncology 2017, 18, 545–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rimawi, M.; Ferrero, J.M.; De La Haba-Rodriguez, J.; Poole, C.; De Placido, S.; Osborne, C.K.; Hegg, R.; Easton, V.; Wohlfarth, C.; Arpino, G. First-line trastuzumab plus an aromatase inhibitor, with or without pertuzumab, in human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive and hormone receptor-positive metastatic or locally advanced breast cancer (PERTAIN): A randomized, open-label phase II trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2018, 36, 2826–2835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ropero, S.; Menéndez, J.A.; Vázquez-Martín, A.; Montero, S.; Cortés-Funes, H.; Colomer, R. Trastuzumab plus tamoxifen: anti-proliferative and molecular interactions in breast carcinoma. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2004, 86, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Tang, S.; Ye, R.; Li, D.; Gu, D.; Chen, R.; Zhang, H.; Sun, J.; Chen, Z. Case Report: Long-Term Response to Pembrolizumab Combined With Endocrine Therapy in Metastatic Breast Cancer Patients With Hormone Receptor Expression. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 610149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiszman, G.L.; Jasnis, M.A. Molecular mechanisms of trastuzumab resistance in HER2 overexpressing breast cancer. International journal of breast cancer 2011, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A. Combining trastuzumab (Herceptin®) with hormonal therapy in breast cancer: what can be expected and why? Annals of oncology 2003, 14, 1697–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, S.R.; Dowsett, M. Aromatase inhibitors for breast cancer: lessons from the laboratory. Nature Reviews Cancer 2003, 3, 821–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocaña, A.; Cruz, J.J.; Pandiella, A. Trastuzumab and antiestrogen therapy: focus on mechanisms of action and resistance. American journal of clinical oncology 2006, 29, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proietti, C.J.; Rosemblit, C.; Beguelin, W.; Rivas, M.A.; Díaz Flaqué, M.a.C.; Charreau, E.H.; Schillaci, R.; Elizalde, P.V. Activation of Stat3 by heregulin/ErbB-2 through the co-option of progesterone receptor signaling drives breast cancer growth. Molecular and cellular biology 2009, 29, 1249–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chervo, M.F.; Cordo Russo, R.I.; Petrillo, E.; Izzo, F.; De Martino, M.; Bellora, N.; Cenciarini, M.E.; Chiauzzi, V.A.; Santa María de la Parra, L.; Pereyra, M.G.; et al. Canonical ErbB-2 isoform and ErbB-2 variant c located in the nucleus drive triple negative breast cancer growth. Oncogene 2020, 39, 6245–6262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venturutti, L.; Romero, L.V.; Urtreger, A.J.; Chervo, M.F.; Cordo Russo, R.I.; Mercogliano, M.F.; Inurrigarro, G.; Pereyra, M.G.; Proietti, C.J.; Izzo, F.; et al. Stat3 regulates ErbB-2 expression and co-opts ErbB-2 nuclear function to induce miR-21 expression, PDCD4 downregulation and breast cancer metastasis. Oncogene 2016, 35, 2208–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, M.C.; Detre, S.; Johnston, S.; Mohsin, S.K.; Shou, J.; Allred, D.C.; Schiff, R.; Osborne, C.K.; Dowsett, M. Molecular changes in tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer: relationship between estrogen receptor, HER-2, and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. Journal of clinical oncology 2005, 23, 2469–2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, S.; Tripathy, D.; Shete, S.; Ashfaq, R.; Haley, B.; Perkins, S.; Beitsch, P.; Khan, A.; Euhus, D.; Osborne, C. HER-2 gene amplification can be acquired as breast cancer progresses. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2004, 101, 9393–9398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, R.I.; Staka, C.; Boyns, F.; Hutcheson, I.R.; Gee, J.M.W. Growth factor-driven mechanisms associated with resistance to estrogen deprivation in breast cancer: new opportunities for therapy. Endocrine-related cancer 2004, 11, 623–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, N.J.; Gee, J.M.; Barrow, D.; Wakeling, A.E.; Nicholson, R.I. Increased constitutive activity of PKB/Akt in tamoxifen resistant breast cancer MCF-7 cells. Breast cancer research and treatment 2004, 87, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowlden, J.M.; Hutcheson, I.R.; Jones, H.E.; Madden, T.; Gee, J.M.; Harper, M.E.; Barrow, D.; Wakeling, A.E.; Nicholson, R.I. Elevated levels of epidermal growth factor receptor/c-erbB2 heterodimers mediate an autocrine growth regulatory pathway in tamoxifen-resistant MCF-7 cells. Endocrinology 2003, 144, 1032–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M.B.; Reiter, R.; Pham, T.; Avellanet, Y.R.; Camara, J.; Lahm, M.; Pentecost, E.; Pratap, K.; Gilmore, B.A.; Divekar, S. Estrogen-like activity of metals in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Endocrinology 2003, 144, 2425–2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeng, M.-H.; Yue, W.; Eischeid, A.; Wang, J.-P.; Santen, R.J. Role of MAP kinase in the enhanced cell proliferation of long term estrogen deprived human breast cancer cells. Breast cancer research and treatment 2000, 62, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brodie, A.; Sabnis, G.; Macedo, L. Xenograft models for aromatase inhibitor studies. The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology 2007, 106, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massarweh, S.; Osborne, C.K.; Jiang, S.; Wakeling, A.E.; Rimawi, M.; Mohsin, S.K.; Hilsenbeck, S.; Schiff, R. Mechanisms of tumor regression and resistance to estrogen deprivation and fulvestrant in a model of estrogen receptor–positive, HER-2/neu-positive breast cancer. Cancer research 2006, 66, 8266–8273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arpino, G.; Wiechmann, L.; Osborne, C.K.; Schiff, R. Crosstalk between the estrogen receptor and the HER tyrosine kinase receptor family: molecular mechanism and clinical implications for endocrine therapy resistance. Endocrine reviews 2008, 29, 217–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clynes, R.A.; Towers, T.L.; Presta, L.G.; Ravetch, J.V. Inhibitory Fc receptors modulate in vivo cytoxicity against tumor targets. Nature medicine 2000, 6, 443–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gennari, R.; Menard, S.; Fagnoni, F.; Ponchio, L.; Scelsi, M.; Tagliabue, E.; Castiglioni, F.; Villani, L.; Magalotti, C.; Gibelli, N. Pilot study of the mechanism of action of preoperative trastuzumab in patients with primary operable breast tumors overexpressing HER2. Clinical cancer research 2004, 10, 5650–5655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimmerjahn, F.; Ravetch, J.V. Fcγ receptors as regulators of immune responses. Nature Reviews Immunology 2008, 8, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordstrom, J.L.; Gorlatov, S.; Zhang, W.; Yang, Y.; Huang, L.; Burke, S.; Li, H.; Ciccarone, V.; Zhang, T.; Stavenhagen, J. Anti-tumor activity and toxicokinetics analysis of MGAH22, an anti-HER2 monoclonal antibody with enhanced Fcγ receptor binding properties. Breast Cancer Research 2011, 13, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musolino, A.; Gradishar, W.J.; Rugo, H.S.; Nordstrom, J.L.; Rock, E.P.; Arnaldez, F.; Pegram, M.D. Role of Fcγ receptors in HER2-targeted breast cancer therapy. Journal for immunotherapy of cancer 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modi, S.; Jacot, W.; Yamashita, T.; Sohn, J.; Vidal, M.; Tokunaga, E.; Tsurutani, J.; Ueno, N.T.; Prat, A.; Chae, Y.S. Trastuzumab deruxtecan in previously treated HER2-low advanced breast cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 2022, 387, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petricevic, B.; Laengle, J.; Singer, J.; Sachet, M.; Fazekas, J.; Steger, G.; Bartsch, R.; Jensen-Jarolim, E.; Bergmann, M. Trastuzumab mediates antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity and phagocytosis to the same extent in both adjuvant and metastatic HER2/neu breast cancer patients. J Transl Med 2013, 11, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Albers, A.J.; Smith, T.S.; Riddell, G.T.; Richards, J.O. Differential regulation of human monocytes and NK cells by antibody-opsonized tumors. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2018, 67, 1239–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, J.; Cescon, D.W.; Rugo, H.S.; Nowecki, Z.; Im, S.-A.; Yusof, M.M.; Gallardo, C.; Lipatov, O.; Barrios, C.H.; Holgado, E. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy versus placebo plus chemotherapy for previously untreated locally recurrent inoperable or metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (KEYNOTE-355): a randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase 3 clinical trial. The Lancet 2020, 396, 1817–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, P.; Cortes, J.; Dent, R.; Pusztai, L.; McArthur, H.; Kümmel, S.; Bergh, J.; Denkert, C.; Park, Y.; Hui, R. VP7-2021: KEYNOTE-522: Phase III study of neoadjuvant pembrolizumab+ chemotherapy vs. placebo+ chemotherapy, followed by adjuvant pembrolizumab vs. placebo for early-stage TNBC. Annals of Oncology 2021, 32, 1198–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajana, V.K.; Penumaka, S.M.; Saritha, C.; Ravichandiran, V.; Mandal, D. Yuflyma, A High Concentration and Citrate-free Adalimumab Biosimilar, Received FDA Approval for Treating Different Forms of Inflammato ry Diseases. Antiinflamm Antiallergy Agents Med Chem 2023, 22, 273–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stagg, J.; Loi, S.; Divisekera, U.; Ngiow, S.F.; Duret, H.; Yagita, H.; Teng, M.W.; Smyth, M.J. Anti–ErbB-2 mAb therapy requires type I and II interferons and synergizes with anti–PD-1 or anti-CD137 mAb therapy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2011, 108, 7142–7147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loi, S.; Giobbie-Hurder, A.; Gombos, A.; Bachelot, T.; Hui, R.; Curigliano, G.; Campone, M.; Biganzoli, L.; Bonnefoi, H.; Jerusalem, G. Pembrolizumab plus trastuzumab in trastuzumab-resistant, advanced, HER2-positive breast cancer (PANACEA): a single-arm, multicentre, phase 1b–2 trial. The Lancet Oncology 2019, 20, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emens, L.A.; Esteva, F.J.; Beresford, M.; Saura, C.; De Laurentiis, M.; Kim, S.-B.; Im, S.-A.; Wang, Y.; Salgado, R.; Mani, A. Trastuzumab emtansine plus atezolizumab versus trastuzumab emtansine plus placebo in previously treated, HER2-positive advanced breast cancer (KATE2): a phase 2, multicentre, randomised, double-blind trial. The lancet oncology 2020, 21, 1283–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huober, J.; Barrios, C.; Niikura, N.; Jarzab, M.; Chang, Y.; Huggins-Puhalla, S.; Graupner, V.; Eiger, D.; Henschel, V.; Gochitashvili, N. VP6-2021: IMpassion050: a phase III study of neoadjuvant atezolizumab+ pertuzumab+ trastuzumab+ chemotherapy (neoadj A+ PH+ CT) in high-risk, HER2-positive early breast cancer (EBC). Annals of Oncology 2021, 32, 1061–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, S.; Schmid, P.; Rugo, H.; Winer, E.; Loirat, D.; Awada, A.; Cescon, D.; Iwata, H.; Campone, M.; Nanda, R. Pembrolizumab monotherapy for previously treated metastatic triple-negative breast cancer: cohort A of the phase II KEYNOTE-086 study. Annals of Oncology 2019, 30, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmid, P.; Cortes, J.; Dent, R.; Pusztai, L.; McArthur, H.; Kümmel, S.; Bergh, J.; Denkert, C.; Park, Y.H.; Hui, R. Event-free survival with pembrolizumab in early triple-negative breast cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 2022, 386, 556–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, P.; Cortes, J.; Dent, R.; Pusztai, L.; McArthur, H.; Kümmel, S.; Bergh, J.; Denkert, C.; Park, Y.H.; Hui, R. Abstract GS1-01: KEYNOTE-522 study of neoadjuvant pembrolizumab+ chemotherapy vs placebo+ chemotherapy, followed by adjuvant pembrolizumab vs placebo for early-stage TNBC: Event-free survival sensitivity and subgroup analyses. Cancer Research 2022, 82, GS1–01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luen, S.J.; Salgado, R.; Fox, S.; Savas, P.; Eng-Wong, J.; Clark, E.; Kiermaier, A.; Swain, S.M.; Baselga, J.; Michiels, S. Tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes in advanced HER2-positive breast cancer treated with pertuzumab or placebo in addition to trastuzumab and docetaxel: a retrospective analysis of the CLEOPATRA study. The Lancet Oncology 2017, 18, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denkert, C.; Von Minckwitz, G.; Brase, J.C.; Sinn, B.V.; Gade, S.; Kronenwett, R.; Pfitzner, B.M.; Salat, C.; Loi, S.; Schmitt, W.D. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy with or without carboplatin in human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive and triple-negative primary breast cancers. J Clin oncol 2015, 33, 983–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonneau, D.; Longy, M. Mutations of the human PTEN gene. Human mutation 2000, 16, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansal, I.; Sellers, W.R. The biology and clinical relevance of the PTEN tumor suppressor pathway. Journal of clinical oncology 2004, 22, 2954–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahta, R.; Yu, D.; Hung, M.-C.; Hortobagyi, G.N.; Esteva, F.J. Mechanisms of disease: understanding resistance to HER2-targeted therapy in human breast cancer. Nature clinical practice Oncology 2006, 3, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandolfi, P.P. Breast cancer--loss of PTEN predicts resistance to treatment. N Engl J Med 2004, 351, 2337–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berns, K.; Horlings, H.M.; Hennessy, B.T.; Madiredjo, M.; Hijmans, E.M.; Beelen, K.; Linn, S.C.; Gonzalez-Angulo, A.M.; Stemke-Hale, K.; Hauptmann, M. A functional genetic approach identifies the PI3K pathway as a major determinant of trastuzumab resistance in breast cancer. Cancer cell 2007, 12, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, Y.; Lan, K.-H.; Zhou, X.; Tan, M.; Esteva, F.J.; Sahin, A.A.; Klos, K.S.; Li, P.; Monia, B.P.; Nguyen, N.T. PTEN activation contributes to tumor inhibition by trastuzumab, and loss of PTEN predicts trastuzumab resistance in patients. Cancer cell 2004, 6, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saal, L.H.; Holm, K.; Maurer, M.; Memeo, L.; Su, T.; Wang, X.; Yu, J.S.; Malmström, P.-O.; Mansukhani, M.; Enoksson, J. PIK3CA mutations correlate with hormone receptors, node metastasis, and ERBB2, and are mutually exclusive with PTEN loss in human breast carcinoma. Cancer research 2005, 65, 2554–2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stemke-Hale, K.; Gonzalez-Angulo, A.M.; Lluch, A.; Neve, R.M.; Kuo, W.-L.; Davies, M.; Carey, M.; Hu, Z.; Guan, Y.; Sahin, A. An integrative genomic and proteomic analysis of PIK3CA, PTEN, and AKT mutations in breast cancer. Cancer research 2008, 68, 6084–6091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteva, F.J.; Guo, H.; Zhang, S.; Santa-Maria, C.; Stone, S.; Lanchbury, J.S.; Sahin, A.A.; Hortobagyi, G.N.; Yu, D. PTEN, PIK3CA, p-AKT, and p-p70S6K status: association with trastuzumab response and survival in patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. The American journal of pathology 2010, 177, 1647–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandarlapaty, S.; King, T.; Sakr, R.; Barbashina, V.; Arroyo, N.; Morrogh, M.; Wynveen, C.; Shanu, M.; Norton, L.; Rosen, N. Hyperactivation of the PI3K-AKT Pathway Commonly Underlies Resistance to Trastuzumab in HER2 Amplified Breast Cancer. Cancer Research 2009, 69, 709–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakr, R.A.; Barbashina, V.; Morrogh, M.; Chandarlapaty, S.; Andrade, V.P.; Arroyo, C.D.; Olvera, N.; King, T.A. Protocol for PTEN expression by immunohistochemistry in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded human breast carcinoma. Applied immunohistochemistry & molecular morphology: AIMM/official publication of the Society for Applied Immunohistochemistry 2010, 18, 371. [Google Scholar]

- Kalinsky, K.; Jacks, L.M.; Heguy, A.; Patil, S.; Drobnjak, M.; Bhanot, U.K.; Hedvat, C.V.; Traina, T.A.; Solit, D.; Gerald, W. PIK3CA mutation associates with improved outcome in breast cancer. Clinical cancer research 2009, 15, 5049–5059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, C.; Jones, D.R.; Rodríguez-Viciana, P.; Gonzalez-García, A.; Leonardo, E.; Wennström, S.; von Kobbe, C.; Toran, J.L.; Luis, R.; Calvo, V. Identification and characterization of a new oncogene derived from the regulatory subunit of phosphoinositide 3-kinase. The EMBO journal 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philp, A.J.; Campbell, I.G.; Leet, C.; Vincan, E.; Rockman, S.P.; Whitehead, R.H.; Thomas, R.J.; Phillips, W.A. The phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase p85α gene is an oncogene in human ovarian and colon tumors. Cancer research 2001, 61, 7426–7429. [Google Scholar]

- McCubrey, J.A.; Abrams, S.L.; Fitzgerald, T.L.; Cocco, L.; Martelli, A.M.; Montalto, G.; Cervello, M.; Scalisi, A.; Candido, S.; Libra, M. Roles of signaling pathways in drug resistance, cancer initiating cells and cancer progression and metastasis. Advances in biological regulation 2015, 57, 75–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherr, C.J.; Roberts, J.M. CDK inhibitors: positive and negative regulators of G1-phase progression. Genes Dev 1999, 13, 1501–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philipp-Staheli, J.; Payne, S.R.; Kemp, C.J. p27Kip1: regulation and function of a haploinsufficient tumor suppressor and its misregulation in cancer. Experimental cell research 2001, 264, 148–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.-Y.; Zhou, B.P.; Hung, M.-C.; Lee, M.-H. Oncogenic signals of HER-2/neu in regulating the stability of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2000, 275, 24735–24739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaltriti, M.; Eichhorn, P.J.; Cortés, J.; Prudkin, L.; Aura, C.; Jiménez, J.; Chandarlapaty, S.; Serra, V.; Prat, A.; Ibrahim, Y.H. Cyclin E amplification/overexpression is a mechanism of trastuzumab resistance in HER2+ breast cancer patients. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2011, 108, 3761–3766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, X.-F.; Claret, F.-X.; Lammayot, A.; Tian, L.; Deshpande, D.; LaPushin, R.; Tari, A.M.; Bast, R.C. The role of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27Kip1 in anti-HER2 antibody-induced G1 cell cycle arrest and tumor growth inhibition. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2003, 278, 23441–23450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marches, R.; Uhr, J.W. Enhancement of the p27Kip1-mediated antiproliferative effect of trastuzumab (Herceptin) on HER2-overexpressing tumor cells. International journal of cancer 2004, 112, 492–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Zi, X.; Zhao, Y.; Mascarenhas, D.; Pollak, M. Insulin-like growth factor-I receptor signaling and resistance to trastuzumab (Herceptin). Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2001, 93, 1852–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerome, L.; Alami, N.; Belanger, S.; Page, V.; Yu, Q.; Paterson, J.; Shiry, L.; Pegram, M.; Leyland-Jones, B. Recombinant human insulin-like growth factor binding protein 3 inhibits growth of human epidermal growth factor receptor-2–overexpressing breast tumors and potentiates Herceptin activity in vivo. Cancer research 2006, 66, 7245–7252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Fan, Z.; Edgerton, S.M.; Yang, X.; Lind, S.E.; Thor, A.D. Potent anti-proliferative effects of metformin on trastuzumab-resistant breast cancer cells via inhibition of erbB2/IGF-1 receptor interactions. Cell Cycle 2011, 10, 2959–2966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahta, R.; Yuan, L.X.; Zhang, B.; Kobayashi, R.; Esteva, F.J. Insulin-like growth factor-I receptor/human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 heterodimerization contributes to trastuzumab resistance of breast cancer cells. Cancer Res 2005, 65, 11118–11128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shattuck, D.L.; Miller, J.K.; Carraway III, K.L.; Sweeney, C. Met receptor contributes to trastuzumab resistance of Her2-overexpressing breast cancer cells. Cancer research 2008, 68, 1471–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Greger, J.; Shi, H.; Liu, Y.; Greshock, J.; Annan, R.; Halsey, W.; Sathe, G.M.; Martin, A.-M.; Gilmer, T.M. Novel mechanism of lapatinib resistance in HER2-positive breast tumor cells: activation of AXL. Cancer research 2009, 69, 6871–6878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottaro, D.P.; Rubin, J.S.; Faletto, D.L.; Chan, A.M.-L.; Kmiecik, T.E.; Vande Woude, G.F.; Aaronson, S.A. Identification of the hepatocyte growth factor receptor as the c-met proto-oncogene product. Science 1991, 251, 802–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, L.; You, X.-L.; Al Moustafa, A.-E.; Batist, G.; Hynes, N.E.; Mader, S.; Meloche, S.; Alaoui-Jamali, M.A. Heregulin selectively upregulates vascular endothelial growth factor secretion in cancer cells and stimulates angiogenesis. Oncogene 2000, 19, 3460–3469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.Y.; Dolled-Filhart, M.; Ocal, I.T.; Singh, B.; Lin, C.-Y.; Dickson, R.B.; Rimm, D.L.; Camp, R.L. Tissue microarray analysis of hepatocyte growth factor/Met pathway components reveals a role for Met, matriptase, and hepatocyte growth factor activator inhibitor 1 in the progression of node-negative breast cancer. Cancer research 2003, 63, 1101–1105. [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita, J.-i.; Ogawa, M.; Yamashita, S.-i.; Nomura, K.; Kuramoto, M.; Saishoji, T.; Shin, S. Immunoreactive hepatocyte growth factor is a strong and independent predictor of recurrence and survival in human breast cancer. Cancer research 1994, 54, 1630–1633. [Google Scholar]

- Lindemann, K.; Resau, J.; Nährig, J.; Kort, E.; Leeser, B.; Annecke, K.; Welk, A.; Schäfer, J.; Vande Woude, G.; Lengyel, E. Differential expression of c-Met, its ligand HGF/SF and HER2/neu in DCIS and adjacent normal breast tissue. Histopathology 2007, 51, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.; Zerillo, C.; Kolmakova, J.; Christensen, J.; Harris, L.; Rimm, D.; Digiovanna, M.; Stern, D. Association of constitutively activated hepatocyte growth factor receptor (Met) with resistance to a dual EGFR/Her2 inhibitor in non-small-cell lung cancer cells. British journal of cancer 2009, 100, 941–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yao, W.; Newton, R.C.; Scherle, P.A. Targeting the c-MET signaling pathway for cancer therapy. Expert opinion on investigational drugs 2008, 17, 997–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelman, J.A.; Zejnullahu, K.; Mitsudomi, T.; Song, Y.; Hyland, C.; Park, J.O.; Lindeman, N.; Gale, C.-M.; Zhao, X.; Christensen, J. MET amplification leads to gefitinib resistance in lung cancer by activating ERBB3 signaling. science 2007, 316, 1039–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, P.D.; Huang, A.C.; Xu, X.; Orlowski, R.; Amaravadi, R.K.; Schuchter, L.M.; Zhang, P.; Tchou, J.; Matlawski, T.; Cervini, A.; et al. Phase I Trial of Autologous RNA-electroporated cMET-directed CAR T Cells Administered Intravenously in Patients with Melanoma and Breast Carcinoma. Cancer Res Commun 2023, 3, 821–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelkmann, W. Erythropoietin: structure, control of production, and function. Physiological reviews 1992, 72, 449–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damen, J.E.; Liu, L.; Cutler, R.L.; Krystal, G. Erythropoietin stimulates the tyrosine phosphorylation of Shc and its association with Grb2 and a 145-Kd tyrosine phosphorylated protein. 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, K.; Esteva, F.J.; Albarracin, C.; Stemke-Hale, K.; Lu, Y.; Bianchini, G.; Yang, C.-Y.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Chen, C.-T. Recombinant human erythropoietin antagonizes trastuzumab treatment of breast cancer cells via Jak2-mediated Src activation and PTEN inactivation. Cancer cell 2010, 18, 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puglisi, F.; Minisini, A.M.; De Angelis, C.; Arpino, G. Overcoming treatment resistance in HER2-positive breast cancer: potential strategies. Drugs 2012, 72, 1175–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Duan, X.; Xu, L.; Ye, J.; Zhao, J.; Liu, Y. Erythropoietin receptor expression and its relationship with trastuzumab response and resistance in HER2-positive breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2012, 136, 739–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dokmanovic, M.; Hirsch, D.S.; Shen, Y.; Wu, W.J. Rac1 contributes to trastuzumab resistance of breast cancer cells: Rac1 as a potential therapeutic target for the treatment of trastuzumab-resistant breast cancer. Molecular cancer therapeutics 2009, 8, 1557–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnelzer, A.; Prechtel, D.; Knaus, U.; Dehne, K.; Gerhard, M.; Graeff, H.; Harbeck, N.; Schmitt, M.; Lengyel, E. Rac1 in human breast cancer: overexpression, mutation analysis, and characterization of a new isoform, Rac1b. Oncogene 2000, 19, 3013–3020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardama, G.; Comin, M.; Alonso, D.; Gómez, D. Rho GTPases as therapeutic targets in cancer and other human diseases. Medicina 2010, 70, 555–564. [Google Scholar]

- Humphries, B.; Wang, Z.; Yang, C. Rho GTPases: Big Players in Breast Cancer Initiation, Metastasis and Therapeutic Responses. Cells 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas, M.A.; Tkach, M.; Beguelin, W.; Proietti, C.J.; Rosemblit, C.; Charreau, E.H.; Elizalde, P.V.; Schillaci, R. Transactivation of ErbB-2 induced by tumor necrosis factor α promotes NF-κB activation and breast cancer cell proliferation. Breast cancer research and treatment 2010, 122, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Kong, X.; Xuan, L.; Wang, Z.; Huang, Y.H. Prolactin and endocrine therapy resistance in breast cancer: The next potential hope for breast cancer treatment. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine 2021, 25, 10327–10348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercogliano, M.F.; Bruni, S.; Elizalde, P.V.; Schillaci, R. Tumor Necrosis Factor α Blockade: An Opportunity to Tackle Breast Cancer. Front Oncol 2020, 10, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruni, S.; Mauro, F.L.; Proietti, C.J.; Cordo-Russo, R.I.; Rivas, M.A.; Inurrigarro, G.; Dupont, A.; Rocha, D.; Fernández, E.A.; Deza, E.G.; et al. Blocking soluble TNFα sensitizes HER2-positive breast cancer to trastuzumab through MUC4 downregulation and subverts immunosuppression. J Immunother Cancer 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco-Velázquez, M.A.; Popov, V.M.; Lisanti, M.P.; Pestell, R.G. The role of breast cancer stem cells in metastasis and therapeutic implications. The American journal of pathology 2011, 179, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozorgi, A.; Khazaei, M.; Khazaei, M.R. New findings on breast cancer stem cells: a review. Journal of breast cancer 2015, 18, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aghazadeh, S.; Yazdanparast, R. Activation of STAT3/HIF-1α/Hes-1 axis promotes trastuzumab resistance in HER2-overexpressing breast cancer cells via down-regulation of PTEN. Biochimica et biophysica acta. General subjects 2017, 1861, 1970–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Junttila, T.T.; Akita, R.W.; Parsons, K.; Fields, C.; Lewis Phillips, G.D.; Friedman, L.S.; Sampath, D.; Sliwkowski, M.X. Ligand-independent HER2/HER3/PI3K complex is disrupted by trastuzumab and is effectively inhibited by the PI3K inhibitor GDC-0941. Cancer cell 2009, 15, 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Cho, Y.; Oh, E.; Lee, N.; An, H.; Sung, D.; Cho, T.M.; Seo, J.H. Disulfiram targets cancer stem-like properties and the HER2/Akt signaling pathway in HER2-positive breast cancer; Elsevier.

- Magnifico, A.; Albano, L.; Campaner, S.; Delia, D.; Castiglioni, F.; Gasparini, P.; Sozzi, G.; Fontanella, E.; Menard, S.; Tagliabue, E. Tumor-initiating cells of HER2-positive carcinoma cell lines express the highest oncoprotein levels and are sensitive to trastuzumab. In AACRA Magnifico, L Albano, S Campaner, D Delia, F Castiglioni, P Gasparini, G SozziClinical Cancer Research, 2009•AACR; 1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paik, S.; Kim, C.; Wolmark, N. HER2 Status and Benefit from Adjuvant Trastuzumab in Breast Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 2008, 358, 1409–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkaya, H.; Paulson, A.; Iovino, F.; Wicha, M.S. HER2 regulates the mammary stem/progenitor cell population driving tumorigenesis and invasion; nature.comH Korkaya, A Paulson, F Iovino, MS WichaOncogene, 2008•nature.com.

- Chakrabarty, A.; Bhola, N.E.; Sutton, C.; Ghosh, R.; Kuba, M.G.; Dave, B.; Chang, J.C.; Arteaga, C.L. Trastuzumab-resistant cells rely on a HER2-PI3K-FoxO-survivin axis and are sensitive to PI3K inhibitors; AACRA Chakrabarty, NE Bhola, C Sutton, R Ghosh, MG Kuba, B Dave, JC Chang, CL ArteagaCancer research, 2013•AACR.

- Yu, F.; Zhao, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Guo, R.; Bai, J.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J. The combination of NVP-BKM120 with trastuzumab or RAD001 synergistically inhibits the growth of breast cancer stem cells in vivo; spandidos-publications.comF Yu, J Zhao, Y Hu, Y Zhou, R Guo, J Bai, S Zhang, H Zhang, J ZhangOncology reports, 2016•spandidos-publications.com.

- Kim, Y.J.; Sung, D.; Oh, E.; Cho, Y.; Cho, T.M.; Farrand, L.; Seo, J.H.; Kim, J.Y. Flubendazole overcomes trastuzumab resistance by targeting cancer stem-like properties and HER2 signaling in HER2-positive breast cancer; Elsevier.

- Korkaya, H.; Kim, G.-I.; Davis, A.; Malik, F.; Henry, N.L.; Ithimakin, S.; Quraishi, A.A.; Tawakkol, N.; Angelo, R.D.; Paulson, A.K.; et al. Activation of an IL6 inflammatory loop mediates trastuzumab resistance in HER2+ breast cancer by expanding the cancer stem cell population. cell.comH Korkaya, G Kim, A Davis, F Malik, NL Henry, S Ithimakin, AA Quraishi, N TawakkolMolecular cell, 2012•cell.com 2012, 47, 570–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Yamamoto, S.; Burnette, B.L.; …, D.H.C.; undefined. Transcriptome profiling reveals novel gene expression signatures and regulating transcription factors of TGFβ-induced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Wiley Online LibraryL Du, S Yamamoto, BL Burnette, D Huang, K Gao, N Jamshidi, MD KuoCancer medicine, 2016•Wiley Online Library 2016, 5, 1962–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chihara, Y.; Shimoda, M.; Hori, A.; Ohara, A.; Naoi, Y.; Ikeda, J.i.; Kagara, N.; Tanei, T.; Shimomura, A.; Shimazu, K.; et al. A small-molecule inhibitor of SMAD3 attenuates resistance to anti-HER2 drugs in HER2-positive breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment 2017, 166, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Tran, T.; Dwabe, S.; Sarkissyan, M.; Kim, J.; Nava, M.; Clayton, S.; Pietras, R.; Farias-Eisner, R. A83-01 inhibits TGF-β-induced upregulation of Wnt3 and epithelial to mesenchymal transition in HER2-overexpressing breast cancer cells; SpringerY Wu, T Tran, S Dwabe, M Sarkissyan, J Kim, M Nava, S Clayton, R Pietras, R Farias-EisnerBreast cancer research and treatment, 2017•Springer.

- Vazquez-Martin, A.; Oliveras-Ferraros, C.; Barco, S.D.; Martin-Castillo, B.; Menendez, J.A. The anti-diabetic drug metformin suppresses self-renewal and proliferation of trastuzumab-resistant tumor-initiating breast cancer stem cells. SpringerA Vazquez-Martin, C Oliveras-Ferraros, SD Barco, B Martin-Castillo, JA MenendezBreast cancer research and treatment, 2011•Springer 2010, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.Y.; Lee, H.E.; Li, H.; Shipitsin, M.; et al. Heterogeneity for stem cell–related markers according to tumor subtype and histologic stage in breast cancer; AACR.

- Jang, G.B.; Kim, J.Y.; Cho, S.D.; Park, K.S.; Jung, J.Y.; Lee, H.Y. Blockade of Wnt/β-catenin signaling suppresses breast cancer metastasis by inhibiting CSC-like phenotype; nature.comGB Jang, JY Kim, SD Cho, KS Park, JY Jung, HY Lee, IS Hong, JS NamScientific reports, 2015•nature.com.

- Loh, Y.N.; Hedditch, E.L.; Baker, L.A.; Jary, E.; Ward, R.L.; Ford, C.E. The Wnt signalling pathway is upregulated in an in vitro model of acquired tamoxifen resistant breast cancer. BMC Cancer 2013, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Ginther, C.; Kim, J.; Mosher, N.; Chung, S.; Slamon, D.; Vadgama, J.V. Expression of Wnt3 activates Wnt/β-catenin pathway and promotes EMT-like phenotype in trastuzumab-resistant HER2-overexpressing breast cancer cells; AACRY Wu, C Ginther, J Kim, N Mosher, S Chung, D Slamon, JV VadgamaMolecular Cancer Research, 2012•AACR.

- Wu, Y.; Tran, T.; Dwabe, S.; Sarkissyan, M.; Kim, J.; Nava, M.; Clayton, S.; Pietras, R.; Farias-Eisner, R.; Vadgama, J.V. A83-01 inhibits TGF-β-induced upregulation of Wnt3 and epithelial to mesenchymal transition in HER2-overexpressing breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment 2017, 163, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schott, A.F.; Landis, M.D.; Dontu, G.; Griffith, K.A.; Layman, R.M.; Krop, I.; Paskett, L.A.; Wong, H.; Dobrolecki, L.E.; Lewis, M.T.; et al. Preclinical and clinical studies of gamma secretase inhibitors with docetaxel on human breast tumors. Clinical Cancer Research 2013, 19, 1512–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takebe, N.; Nguyen, D.; Yang, S.X. Targeting Notch signaling pathway in cancer: Clinical development advances and challenges. Pharmacology and Therapeutics 2014, 141, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, W.C.; Fischer, M.M.; Axelrod, F.; Bond, C.; Cain, J.; Cancilla, B.; Henner, W.R.; Meisner, R.; Sato, A.; Shah, J.; et al. Targeting notch signaling with a Notch2/Notch3 antagonist (Tarextumab) inhibits tumor growth and decreases tumor-initiating cell frequency. Clinical Cancer Research 2015, 21, 2084–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, H.; Pan, C.; Zhang, M.; Huo, H.; Shan, H.; Wu, J. Histone methyltransferase SETD1A interacts with notch and promotes notch transactivation to augment ovarian cancer development. BMC Cancer 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeage, M.J.; Kotasek, D.; Markman, B.; Hidalgo, M.; Millward, M.J.; Jameson, M.B.; Harris, D.L.; Stagg, R.J.; Kapoun, A.M.; Xu, L.; et al. Phase IB Trial of the Anti-Cancer Stem Cell DLL4-Binding Agent Demcizumab with Pemetrexed and Carboplatin as First-Line Treatment of Metastatic Non-Squamous NSCLC. Targeted Oncology 2018, 13, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silkenstedt, E.; Arenas, F.; Colom-Sanmartí, B.; Xargay-Torrent, S.; Higashi, M.; Giró, A.; Rodriguez, V.; Fuentes, P.; Aulitzky, W.E.; Van Der Kuip, H.; et al. Notch1 signaling in NOTCH1-mutated mantle cell lymphoma depends on Delta-Like ligand 4 and is a potential target for specific antibody therapy. Journal of experimental & clinical cancer research : CR 2019, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chu, J.; Feng, W.; Yang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Qin, Y.; Xu, J.; Li, J.; Vasilatos, S.N.; et al. EPHA5 mediates trastuzumab resistance in HER2-positive breast cancers through regulating cancer stem cell-like properties. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology 2019, 33, 4851–4865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, S.S.; Giehl, N.; Wu, Y.; Vadgama, J.V. STAT3 activation in HER2-overexpressing breast cancer promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cancer stem cell traits. International Journal of Oncology 2014, 44, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.S.; Uddin, M.; Noman, A.S.M.; Akter, H.; Dity, N.J.; Basiruzzman, M.; Uddin, F.; Ahsan, J.; Annoor, S.; Alaiya, A.A.; et al. Antibody-drug conjugate T-DM1 treatment for HER2+ breast cancer induces ROR1 and confers resistance through activation of Hippo transcriptional coactivator YAP1. EBioMedicine 2019, 43, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almozyan, S.; Colak, D.; Mansour, F.; Alaiya, A.; Al-Harazi, O.; Qattan, A.; Al-Mohanna, F.; Al-Alwan, M.; Ghebeh, H. PD-L1 promotes OCT4 and Nanog expression in breast cancer stem cells by sustaining PI3K/AKT pathway activation. International Journal of Cancer 2017, 141, 1402–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaganty, B.K.R.; Qiu, S.; Gest, A.; Lu, Y.; Ivan, C.; Calin, G.A.; Weiner, L.M.; Fan, Z. Trastuzumab upregulates PD-L1 as a potential mechanism of trastuzumab resistance through engagement of immune effector cells and stimulation of IFNγ secretion. Cancer Letters 2018, 430, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, H.P.; Chang, H.L.; Bamodu, O.A.; Yadav, V.K.; Huang, T.Y.; Wu, A.T.H.; Yeh, C.T.; Tsai, S.H.; Lee, W.H. Collagen 1A1 (COL1A1) is a reliable biomarker and putative therapeutic target for hepatocellular carcinogenesis and metastasis. Cancers 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Xu, L.; Chen, J.; Yang, Z.; Liang, C.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Z. Tumor vasculature normalization by orally fed erlotinib to modulate the tumor microenvironment for enhanced cancer nanomedicine and immunotherapy. Biomaterials 2017, 148, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagi, M.; Voutouri, C.; Mpekris, F.; Papageorgis, P.; Martin, M.R.; Martin, J.D.; Demetriou, P.; Pierides, C.; Polydorou, C.; Stylianou, A.; et al. TGF-β inhibition combined with cytotoxic nanomedicine normalizes triple negative breast cancer microenvironment towards anti-tumor immunity. Theranostics 2020, 10, 1910–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Verwilst, P.; Won, M.; Lee, J.; Sessler, J.L.; Han, J.; Kim, J.S. A Small Molecule Strategy for Targeting Cancer Stem Cells in Hypoxic Microenvironments and Preventing Tumorigenesis. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2021, 143, 14115–14124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fico, F.; Santamaria-Martínez, A. TGFBI modulates tumour hypoxia and promotes breast cancer metastasis. Molecular Oncology 2020, 14, 3198–3210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, Y.; Shinjo, K.; Katsushima, K. Long non-coding RNAs as an epigenetic regulator in human cancers. Cancer Science 2017, 108, 1927–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Tsuyada, A.; Ren, X.; Wu, X.; Stubblefield, K.; Rankin-Gee, E.K.; Wang, S.E. Transforming growth factor-Β regulates the sphere-initiating stem cell-like feature in breast cancer through miRNA-181 and ATM. Oncogene 2011, 30, 1470–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zare, M.; Bastami, M.; Solali, S.; Alivand, M.R. Aberrant miRNA promoter methylation and EMT-involving miRNAs in breast cancer metastasis: Diagnosis and therapeutic implications. Journal of Cellular Physiology 2018, 233, 3729–3744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tordonato, C.; Di Fiore, P.P.; Nicassio, F. The role of non-coding RNAs in the regulation of stem cells and progenitors in the normal mammary gland and in breast tumors. Frontiers in Genetics 2015, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, W.D.; Ye, X.M.; Zhang, M.Y.; Zhu, H.Y.; Xi, W.J.; Huang, X.; Zhao, J.; Gu, B.; Zheng, G.X.; Yang, A.G.; et al. MiR-200c suppresses TGF-β signaling and counteracts trastuzumab resistance and metastasis by targeting ZNF217 and ZEB1 in breast cancer. International Journal of Cancer 2014, 135, 1356–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.J.; Wang, L.J.; Yu, B.; Li, Y.H.; Jin, Y.; Bai, X.Z. LncRNA-ATB promotes trastuzumab resistance and invasionmetastasis cascade in breast cancer. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 11652–11663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, J.; Chen, J.; Wang, H.; Yang, L.; Chen, F.; Fan, S.; Wang, J.; Shao, B.; Yin, D.; et al. A serum microRNA signature predicts trastuzumab benefit in HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer patients. Nature Communications 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhai, L.; Wang, H.; Liu, C.; Zhang, J.; Chen, W.; Wei, Q. Downregulation of LncRNA GAS5 causes trastuzumab resistance in breast cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 27778–27786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Yang, L.; Liu, H.; Luo, X. Cancer stem cell-targeted therapeutic approaches for overcoming trastuzumabresistance in HER2-positive breast cancer. Stem Cells 2021, 39, 1125–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinzadeh, A.; Merikhian, P.; Naseri, N.; Eisavand, M.R.; Farahmand, L. MUC1 is a potential target to overcome trastuzumab resistance in breast cancer therapy. Cancer cell international 2022, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curry, J.M.; Besmer, D.M.; Erick, T.K.; Steuerwald, N.; Roy, L.D.; Grover, P.; Rao, S.; Nath, S.; Ferrier, J.W.; Reid, R.W.; et al. Indomethacin enhances anti-tumor efficacy of a MUC1 peptide vaccine against breast cancer in MUC1 transgenic mice. PLoS ONE 2019, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bermejo, I.A.; Navo, C.D.; Castro-López, J.; Guerreiro, A.; Jiménez-Moreno, E.; Sánchez Fernández, E.M.; García-Martín, F.; Hinou, H.; Nishimura, S.I.; García Fernández, J.M.; et al. Synthesis, conformational analysis and in vivo assays of an anti-cancer vaccine that features an unnatural antigen based on an sp2-iminosugar fragment. Chemical science 2020, 11, 3996–4006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Namba, M.; Hattori, N.; Hamada, H.; Yamaguchi, K.; Okamoto, Y.; Nakashima, T.; Masuda, T.; Sakamoto, S.; Horimasu, Y.; Miyamoto, S.; et al. Anti-KL-6/MUC1 monoclonal antibody reverses resistance to trastuzumab-mediated antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity by capping MUC1. Cancer letters 2019, 442, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pegram, M.D.; Borges, V.F.; Ibrahim, N.; Fuloria, J.; Shapiro, C.; Perez, S.; Wang, K.; Schaedli Stark, F.; Courtenay Luck, N. Phase I dose escalation pharmacokinetic assessment of intravenous humanized anti-MUC1 antibody AS1402 in patients with advanced breast cancer. Breast cancer research : BCR 2009, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.J.; Choi, J.R.; Tae, N.; Wi, T.M.; Kim, K.M.; Kim, D.H.; Lee, E.S. Novel Antibodies Targeting MUC1-C Showed Anti-Metastasis and Growth-Inhibitory Effects on Human Breast Cancer Cells. International journal of molecular sciences 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathalie, M.; Ruth, A. Therapeutic MUC1-based cancer vaccine expressed in flagella-efficacy in an aggressive model of breast cancer. World Journal of Vaccines 2012, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Machluf, N.; Arnon, R.; Machluf, N.; Arnon, R. Therapeutic MUC1-Based Cancer Vaccine Expressed in Flagella-Efficacy in an Aggressive Model of Breast Cancer. World Journal of Vaccines 2012, 2, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohebtash, M.; Tsang, K.Y.; Madan, R.A.; Huen, N.Y.; Poole, D.J.; Jochems, C.; Jones, J.; Ferrara, T.; Heery, C.R.; Arlen, P.M.; et al. A pilot study of MUC-1/CEA/TRICOM poxviral-based vaccine in patients with metastatic breast and ovarian cancer. Clinical Cancer Research 2011, 17, 7164–7173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulley, J.L.; Arlen, P.M.; Tsang, K.Y.; Yokokawa, J.; Palena, C.; Poole, D.J.; Remondo, C.; Cereda, V.; Jones, J.L.; Pazdur, M.P.; et al. Pilot study of vaccination with recombinant CEA-MUC-1-TRICOM poxviral-based vaccines in patients with metastatic carcinoma. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2008, 14, 3060–3069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinn, B.V.; Von Minckwitz, G.; Denkert, C.; Eidtmann, H.; Darb-Esfahani, S.; Tesch, H.; Kronenwett, R.; Hoffmann, G.; Belau, A.; Thommsen, C.; et al. Evaluation of Mucin-1 protein and mRNA expression as prognostic and predictive markers after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology 2013, 24, 2316–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Yazdanifar, M.; Roy, L.D.; Whilding, L.M.; Gavrill, A.; Maher, J.; Mukherjee, P. CAR T Cells Targeting the Tumor MUC1 Glycoprotein Reduce Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Growth. Frontiers in immunology 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wang, Y.; Miao, L.; Liu, Q.; Musetti, S.; Li, J.; Huang, L. Combination Immunotherapy of MUC1 mRNA Nano-vaccine and CTLA-4 Blockade Effectively Inhibits Growth of Triple Negative Breast Cancer. Molecular therapy : the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy 2018, 26, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Zhao, L.; Li, W.; Fan, K.; Qian, W.; Hou, S.; Wang, H.; Dai, J.; Wei, H.; Guo, Y. Feedback activation of STAT3 mediates trastuzumab resistance via upregulation of MUC1 and MUC4 expression. Oncotarget 2014, 5, 8317–8329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiraki, M.; Maeda, T.; Mehrotra, N.; Jin, C.; Alam, M.; Bouillez, A.; Hata, T.; Tagde, A.; Keating, A.; Kharbanda, S.; et al. Targeting MUC1-C suppresses BCL2A1 in triple-negative breast cancer. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, M.; Rajabi, H.; Ahmad, R.; Jin, C.; Kufe, D. Targeting the MUC1-C oncoprotein inhibits self-renewal capacity of breast cancer cells. Oncotarget 2014, 5, 2622–2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiraki, M.; Suzuki, Y.; Alam, M.; Hinohara, K.; Hasegawa, M.; Jin, C.; Kharbanda, S.; Kufe, D. MUC1-C Stabilizes MCL-1 in the Oxidative Stress Response of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cells to BCL-2 Inhibitors. Scientific Reports 2016 6:1 2016, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raina, D.; Ahmad, R.; Joshi, M.D.; Yin, L.; Wu, Z.; Kawano, T.; Vasir, B.; Avigan, D.; Kharbanda, S.; Kufe, D. Direct targeting of the mucin 1 oncoprotein blocks survival and tumorigenicity of human breast carcinoma cells. Cancer research 2009, 69, 5133–5141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R.; Raina, D.; Joshi, M.D.; Kawano, T.; Ren, J.; Kharbanda, S.; Kufe, D. MUC1-C ONCOPROTEIN FUNCTIONS AS A DIRECT ACTIVATOR OF THE NF-κB p65 TRANSCRIPTION FACTOR. Cancer research 2009, 69, 7013–7013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Huang, L.; Kufe, D. MUC1 oncoprotein activates the FOXO3a transcription factor in a survival response to oxidative stress. The Journal of biological chemistry 2004, 279, 45721–45727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raina, D.; Uchida, Y.; Kharbanda, A.; Rajabi, H.; Panchamoorthy, G.; Jin, C.; Kharbanda, S.; Scaltriti, M.; Baselga, J.; Kufe, D. Targeting the MUC1-C oncoprotein downregulates HER2 activation and abrogates trastuzumab resistance in breast cancer cells. Oncogene 2014, 33, 3422–3431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurvitz, S.A.; Hu, Y.; O'Brien, N.; Finn, R.S. Current approaches and future directions in the treatment of HER2-positive breast cancer. Cancer treatment reviews 2013, 39, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eichhorn, P.J.A.; Gili, M.; Scaltriti, M.; Serra, V.; Guzman, M.; Nijkamp, W.; Beijersbergen, R.L.; Valero, V.; Seoane, J.; Bernards, R.; et al. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase hyperactivation results in lapatinib resistance that is reversed by the mTOR/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitor NVP-BEZ235. Cancer research 2008, 68, 9221–9230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yarden, Y.; Sliwkowski, M.X. Untangling the ErbB signalling network. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology 2001, 2, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahta, R.; O'Regan, R. Evolving strategies for overcoming resistance to HER2-directed therapy: targeting the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. Clinical breast cancer 2010, 10 Suppl 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnant, M. The role of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibition in the treatment of advanced breast cancer. Current oncology reports 2013, 15, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margariti, N.; Fox, S.B.; Bottini, A.; Generali, D. "Overcoming breast cancer drug resistance with mTOR inhibitors". Could it be a myth or a real possibility in the short-term future? Breast cancer research and treatment 2011, 128, 599–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, R.; Kay, A.; Berg, W.J.; Lebwohl, D. Targeting tumorigenesis: development and use of mTOR inhibitors in cancer therapy. Journal of hematology & oncology 2009, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Martino, M.C.; Van Koetsveld, P.M.; Pivonello, R.; Hofland, L.J. Role of the mTOR pathway in normal and tumoral adrenal cells. Neuroendocrinology 2010, 92 Suppl 1, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keck, S.; Glencer, A.C.; Rugo, H.S. Everolimus and its role in hormone-resistant and trastuzumab-resistant metastatic breast cancer. Future oncology (London, England) 2012, 8, 1383–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, I. Role of mTOR Inhibition in Preventing Resistance and Restoring Sensitivity to Hormone-Targeted and HER2-Targeted Therapies in Breast Cancer. Clinical advances in hematology & oncology : H&O 2013, 11, 217–217. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, C.-H.; Wyszomierski, S.L.; Tseng, L.-M.; Sun, M.-H.; Lan, K.-H.; Neal, C.L.; Mills, G.B.; Hortobagyi, G.N.; Esteva, F.J.; Yu, D. Preclinical testing of clinically applicable strategies for overcoming trastuzumab resistance caused by PTEN deficiency. Clinical Cancer Research 2007, 13, 5883–5888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, T.W.; Forbes, J.T.; Shah, C.; Wyatt, S.K.; Manning, H.C.; Olivares, M.G.; Sanchez, V.; Dugger, T.C.; de Matos Granja, N.; Narasanna, A. Inhibition of mammalian target of rapamycin is required for optimal antitumor effect of HER2 inhibitors against HER2-overexpressing cancer cells. Clinical Cancer Research 2009, 15, 7266–7276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maira, S.-M.; Pecchi, S.; Huang, A.; Burger, M.; Knapp, M.; Sterker, D.; Schnell, C.; Guthy, D.; Nagel, T.; Wiesmann, M. Identification and characterization of NVP-BKM120, an orally available pan-class I PI3-kinase inhibitor. Molecular cancer therapeutics 2012, 11, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andre, F.; Campone, M.; O'Regan, R.; Manlius, C.; Massacesi, C.; Sahmoud, T.; Mukhopadhyay, P.; Soria, J.-C.; Naughton, M.; Hurvitz, S.A. Phase I study of everolimus plus weekly paclitaxel and trastuzumab in patients with metastatic breast cancer pretreated with trastuzumab. J Clin Oncol 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elster, N.; Cremona, M.; Morgan, C.; Toomey, S.; Carr, A.; O’Grady, A.; Hennessy, B.T.; Eustace, A.J. A preclinical evaluation of the PI3K alpha/delta dominant inhibitor BAY 80-6946 in HER2-positive breast cancer models with acquired resistance to the HER2-targeted therapies trastuzumab and lapatinib. Breast cancer research and treatment 2015, 149, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Availabe online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=CN370180537&_cid=P22-LTQ4AC-17139-1#detailMainForm:MyTabViewId:NATIONALBIBLIO.

- Availabe online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=CN375176274&_cid=P22-LTQ49B-16765-1#detailMainForm:MyTabViewId:NATIONALBIBLIO.

- COMBINED PREPARATION FOR REVERSING DRUG RESISTANCE OF BREAST CANCER AND APPLICATION OF MARKER. Availabe online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=CN370180537&_cid=P22-LTQ4AC-17139-1#detailMainForm:MyTabViewId:NATIONALBIBLIO.

- METHODS OF TREATING HER2 POSITIVE BREAST CANCER WITH TUCATINIB IN COMBINATION WITH CAPECITABINE AND TRASTUZUMAB. Availabe online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=WO2021080983&_cid=P22-LTQ4BJ-17652-1#detailMainForm:MyTabViewId:PCTBIBLIO.

- APPLICATION OF DEUBIQUITINATING ENZYME USP37 AS DRUG TARGET IN SCREENING OF DRUGS FOR TREATING DRUG-RESISTANT BREAST CANCER. Availabe online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=CN343417361&_cid=P22-LTQ4DA-18310-1#detailMainForm:MyTabViewId:NATIONALBIBLIO (accessed on 12.11.2021).

- TRINUCLEAR PLATINUM COORDINATION COMPOUNDBASED ON TRI-HOMOAZINE, PREPARATION METHOD AND APPLICATION THEREOF. Availabe online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=CN336184951&_cid=P22-LTQ4EX-19092-1#detailMainForm:MyTabViewId:NATIONALBIBLIO.

- SYSTEM AND METHOD FOR COLD PLASMA THERAPY WITH HER-FAMILY RECEPTORS. Availabe online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=US289330559&_cid=P22-LTQ4GU-19804-1#detailMainForm:MyTabViewId:NATIONALBIBLIO.

- ANTI-HER2 ANTIBODY OR ANTIGEN-BINDING FRAGMENT THEREOF, AND CHIMERIC ANTIGEN RECEPTOR COMPRISING SAME. Availabe online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=WO2019098682&_cid=P22-LTQ4HW-20220-1#detailMainForm:MyTabViewId:PCTBIBLIO.

- APPLICATION OF UCH-L1 AS TARGET SITE IN PREPARATION OF HER2 OVEREXPRESSION BREAST CANCER SENSITIZATION TREATMENT DRUGS. Availabe online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=CN318119386&_cid=P22-LTQ4IY-20615-1#detailMainForm:MyTabViewId:NATIONALBIBLIO.

- TARGETING TRASTUZUMAB-RESISTANT HER2+BREAST CANCER WITH A HER3-TARGETING NANOPARTICLE.

- APPLICATION OF MELATONIN IN PREPARATION OF DRUG FOR TREATING HER2 POSITIVE BREAST CANCER RESISTANT TO TARGETED DRUG. Availabe online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=CN326496984&_cid=P22-LTQ4L2-21446-1#detailMainForm:MyTabViewId:NATIONALBIBLIO.

- METHOD FOR TREATING ANTI-HER2 THERAPY-RESISTANT MUC4+ HER2+ CANCER. Availabe online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=US294690999&_cid=P22-LTQ4MA-21848-1#detailMainForm:MyTabViewId:NATIONALBIBLIO.

- Whenham, N.; D'Hondt, V.; Piccart, M.J. HER2-positive breast cancer: from trastuzumab to innovatory anti-HER2 strategies. Clinical breast cancer 2008, 8, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, M.; Yang, Y.; Liao, W.; Li, Q. Margetuximab versus trastuzumab in patients with advanced breast cancer: A cost-effectiveness analysis. Clinical Breast Cancer 2022, 22, e629–e635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, R.K.; Loi, S.; Okines, A.; Paplomata, E.; Hamilton, E.; Hurvitz, S.A.; Lin, N.U.; Borges, V.; Abramson, V.; Anders, C. Tucatinib, trastuzumab, and capecitabine for HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 2020, 382, 597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criscitiello, C.; Corti, C.; De Laurentiis, M.; Bianchini, G.; Pistilli, B.; Cinieri, S.; Castellan, L.; Arpino, G.; Conte, P.; Di Meco, F. Tucatinib's journey from clinical development to clinical practice: New horizons for HER2-positive metastatic disease and promising prospects for brain metastatic spread. Cancer Treatment Reviews 2023, 102618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.F.; Zhang, Q.Y.; Huang, J.Y.; Chen, L.P.; Lan, X.F.; Bai, X.; Song, L.; Xiong, S.L.; Guo, S.J.; Du, C.W. Pyrotinib combined with trastuzumab and chemotherapy for the treatment of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive metastatic breast cancer: a single-arm exploratory phase II trial. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment 2023, 197, 93–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slamon, D.J.; Leyland-Jones, B.; Shak, S.; Fuchs, H.; Paton, V.; Bajamonde, A.; Fleming, T.; Eiermann, W.; Wolter, J.; Pegram, M.; et al. Use of chemotherapy plus a monoclonal antibody against HER2 for metastatic breast cancer that overexpresses HER2. The New England journal of medicine 2001, 344, 783–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreutzfeldt, J.; Rozeboom, B.; Dey, N.; De, P. The trastuzumab era: current and upcoming targeted HER2+ breast cancer therapies. American Journal of Cancer Research 2020, 10, 1045–1045. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Adams, J.; et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in breast cancer: comparison of plasma, serum, and tissue VEGF and microvessel density and effects of tamoxifen. Cancer Res. 2000, 60, 2898–2905. [Google Scholar]

- Lithgow, D.; et al. C-reactive protein in nipple aspirate fluid: relation to women's health factors. Nurs Res. 2006, 55, 418–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habanjar, O.; et al. Crosstalk of Inflammatory Cytokines within the Breast Tumor Microenvironment. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, J.; Tang, Y. Research progress on the role of reactive oxygen species in the initiation, development and treatment of breast cancer. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2024, 188, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duro-Sánchez, S.; Alonso, M.R.; Arribas, J. Immunotherapies against HER2-Positive Breast Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B.S.; Esteva, F.J. Next-Generation HER2-Targeted Antibody–Drug Conjugates in Breast Cancer. Cancers 2024, 16, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumbhar, P.R.; Kumar, P.; Lasure, A.; Velayutham, R.; Mandal, D. An updated landscape on nanotechnology-based drug delivery, immunotherapy, vaccinations, imaging, and biomarker detections for cancers: recent trends and future directions with clinical success. Discov Nano 2023, 18, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).